Marc Goergen's Blog, page 4

November 17, 2018

The Relationship between Public Listing, Context, Multi-nationality and Internal CSR

This cross-country study argues that corporate social responsibility (CSR) has an internal as well as an external focus: although the internal aspect has been less carefully examined in the literature, ‘doing good’ for society necessarily involves treating employees properly. Focusing on this internal aspect of corporate social responsibility, we investigate how firm and country characteristics affect the likelihood of a firm having a CSR statement and how it impacts the way such firms treat their internal stakeholders and their staff. In particular, our paper examines employer-employee interdependence – how the existence of a CSR statement affects a firm’s investment in its staff and the downsizing of its workforce when required – according to types of firms and legal families.

The following research questions are addressed: read more

The published study is now available free of charge from here.

The following research questions are addressed: read more

The published study is now available free of charge from here.

Published on November 17, 2018 01:07

August 31, 2018

Trust and Shareholder Voting

Theory as well as empirical studies suggest that voting at annual general shareholder meetings (AGMs) creates value. Indeed, voting gives shareholders a final say on major company decisions, such as appointments to the board of directors and the approval of takeover offers. It also enables shareholders to show their support the current management or to disagree with the latter. It is then somewhat surprising that, on average, voter turnout at AGMs is only about 60%. Still, the average voter turnout varies across the world with a minimum of 41% for New Zealand and a maximum of 100% for Cyprus. Moreover, the average approval rates for management-initiated proposals vary between 84% and 100%.

In a study with Peter Limbach and Simon Lesmeister, we propose the level of trust in others that prevails in a country has an effect on shareholder voting and explains differences in voting patterns across countries. The economics literature (see e.g. Zak and Knack 2001) finds that trust increases economic performance, as measured by GDP per capita growth. The argument is as follows: In high-trust countries economic agents do not have to expend as much time on monitoring each other. Hence, they have more time for productive tasks. Therefore, countries with high trust levels should have better economic performance. By examining whether trust affects the level of shareholder monitoring of management, as proxied by voter turnout at AGMs and support of management-initiated proposals, we perform a more direct test of this argument.

Trust has been shown to vary quite substantially across countries with only 3% of Filipinos trusting others while as 74% of Norwegians agree that others can be trusted. By studying the voting outcomes at ordinary and extraordinary AGMs of companies from more than 40 countries, we find empirical support of our main hypothesis: Shareholders in countries with high trust spend less time on monitoring the management of their companies.

In detail, we find that for high-trust countries voter turnout at AGMs is significantly lower while the approval rate for management-initiated proposals is significantly higher. We also find evidence that the lower levels of shareholder voting or monitoring in high-trust countries are not exploited by the firms’ managers. Although low voter turnout and high approval rates for management proposals have been shown to decrease future stock performance, this negative effect is neutralised in high-trust countries. Hence, in high-trust countries it might be optimal for shareholders to trust management and reduce monitoring.

This post was originally published on the webpages of the European Corporate Governance Institute.

In a study with Peter Limbach and Simon Lesmeister, we propose the level of trust in others that prevails in a country has an effect on shareholder voting and explains differences in voting patterns across countries. The economics literature (see e.g. Zak and Knack 2001) finds that trust increases economic performance, as measured by GDP per capita growth. The argument is as follows: In high-trust countries economic agents do not have to expend as much time on monitoring each other. Hence, they have more time for productive tasks. Therefore, countries with high trust levels should have better economic performance. By examining whether trust affects the level of shareholder monitoring of management, as proxied by voter turnout at AGMs and support of management-initiated proposals, we perform a more direct test of this argument.

Trust has been shown to vary quite substantially across countries with only 3% of Filipinos trusting others while as 74% of Norwegians agree that others can be trusted. By studying the voting outcomes at ordinary and extraordinary AGMs of companies from more than 40 countries, we find empirical support of our main hypothesis: Shareholders in countries with high trust spend less time on monitoring the management of their companies.

In detail, we find that for high-trust countries voter turnout at AGMs is significantly lower while the approval rate for management-initiated proposals is significantly higher. We also find evidence that the lower levels of shareholder voting or monitoring in high-trust countries are not exploited by the firms’ managers. Although low voter turnout and high approval rates for management proposals have been shown to decrease future stock performance, this negative effect is neutralised in high-trust countries. Hence, in high-trust countries it might be optimal for shareholders to trust management and reduce monitoring.

This post was originally published on the webpages of the European Corporate Governance Institute.

Published on August 31, 2018 02:22

August 22, 2018

How Acquisition Performance Affects the Market for Non-Executive Directors

In the United Kingdom, successive codes of best practice in corporate governance have highlighted the important role of outside or non-executive directors in ensuring that corporations are run for the benefit of their shareholders. While the first code of best practice, the 1992 Cadbury Report, recommended that there should be a sufficient number of non-executives on the board, the 2003 Higgs Report was much more prescriptive, recommending that there should be a majority of non-executives on the board (excluding the chairman). Similarly, U.S. regulation has been emphasizing the important role of independent or non-executive directors. More specifically, the NYSE and NASDAQ listing rules require companies to have a majority of independent directors.Despite many national regulators pushing for greater non-executive presence on boards, there are few academic studies finding evidence that a greater proportion of non-executives improve firm performance or value. Indeed, most studies do not find any significant impact of non-executives, and at least one study even finds a negative effect.Does this mean that non-executive directors do not matter, that the efforts of regulators have been misguided? One strand of research, which has found that non-executive directors have value, has been studying the labor market for directors. Eugene Fama and Michael Jensen were the first to point out the role of this market in giving directors incentives to create shareholder value. The question that arises is whether this market rewards directors perceived as doing a good job with more future board positions and penalizes those perceived as doing a bad job with fewer board positions. The earliest such studies have focused on executive directors rather than non-executives. Typically, these studies have found that directors, who performed well during their executive careers, end up holding more non-executive directorships. There is also evidence of the disciplinary role of this market, as executives who cut their firm’s dividend are penalized by holding fewer non-executive board seats.What about the market for non-executive directors? Evidence suggests that the labour market rewards non-executives who are good monitors, as evidenced by their willingness to fire badly performing CEOs. In turn, they are punished for being ineffective monitors, as evidenced by the few board seats they hold if their firms have been sued for financial fraud. Nevertheless, a recent study by Steven Davidoff and colleagues on the effects of the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis does not find any evidence that the labor market punished non-executive directors of badly performing financial institutions.Our study focuses on UK firms making acquisition decisions as we are interested in ascertaining how the quality of such decisions affects the future careers of the non-executives involved. Acquisitions are not only one of the most important strategic decisions made by boards, but also represent a discrete event allowing shareholders to assess their wealth effects. We study UK firms that completed at least one acquisition between 1994 and 2010. We focus on UK firms for a number of reasons. First, and as discussed above, during our period of study successive codes of best practice put more emphasis on the monitoring role of non-executives in corporate governance, resulting in a greater percentage of such directors on boards. Second, these successive codes of best practice also discouraged CEO-chair duality, recommending that the roles of the CEO and the chair of the board of directors should be assumed by two separate individuals. This results in a clear delineation between the roles of executives and non-executives in the boardroom. Finally, in contrast to the U.S., where the majority of firms have staggered boards restricting shareholders from removing certain directors at a given time, there are no such restrictions concerning UK boards.We follow our firms for five years after the acquisition has been completed. Hence, our research period effectively ends in 2015. We investigate whether the post-acquisition performance of the acquirers affects the future career of the non-executives in place during the year of the acquisition. More specifically, we study whether post-acquisition performance of the acquirers affects the number of board seats that the non-executives hold five years after the completion of the acquisitions. We use a number of performance measures, including accounting performance, market performance and dividend payout.We do not find that post-acquisition accounting and market-based performance have any effect on the number of board seats held by the non-executives on the board of the acquirer. We do, however, find that dividend cuts and omissions reduce the number of board seats the non-executive holds, and dividend increases augment that number. How can we explain our findings that the post-acquisition dividends affect the careers of the non-executives, whereas other measures of performance do not? First, dividends are more tangible for most investors, as they are associated with cash in hand whereas capital gains, for example, are only realized once a stock has been sold. Second, as James Lintner’s interviews with managers in the 1950s suggest, managers are very reluctant to change the dividend. Hence, any such change is likely to be much more salient than changes to other performance measures. Finally, shareholders do not value dividends only because they are a regular source of cash, but also because they address Michael Jensen’s free cash flow problem by reducing retained profits and by forcing firms to return to the stock market more often for financing, thereby subjecting themselves to the regular scrutiny of the capital markets. We also show that acquirers pay out the extra value created by the acquisitions to their shareholders via increased dividends. Bad acquisitions, which are associated with negative stock market performance, result in dividend cuts, or even omitted dividends, five years after the acquisition. Finally, we show that a bad acquisition is unlikely to have an immediate, detrimental effect on performance, as its effect on a non-executive’s career is gradual. Hence, our study suggests that dividends matter and should be accounted for when exploring the impact of post-acquisition performance on the future careers of non-executive directors.Originally posted on the Columbia Law School Blue Sky Blog. The paper is available for free from the British Journal of Management.

Published on August 22, 2018 11:25

July 18, 2018

Trust and Shareholder Voting - Internet Appendix

The internet appendix for the paper entitled "Trust and Shareholder Voting" is available from here.

Published on July 18, 2018 07:39

Trust and Shareholder Voting

The internet appendix for the paper entitled "Trust and Shareholder Voting" is available from here.

Published on July 18, 2018 07:39

May 8, 2018

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE – MODULE OUTLINE

This module is intended for advanced undergraduates in business and management, accounting, finance, or economics, and Master students. The module is delivered over a total of 24 hours of lectures with a flexible format including traditional lectures, class discussions of the end-of-chapter questions in Goergen (2018) and the multiple choice questions (see below). AIMS OF THE MODULEThis module aims to introduce you to recent developments in the theory and practice of corporate governance. The module adopts an international perspective by comparing the main corporate governance systems across the world. LEARNING OUTCOMES OF THE MODULEOn completion of the module you should be able to: Evaluate the current state of corporate governance in an international context; describe differences in corporate control and managerial power across the world; assess the potential conflicts of interests that may arise in various corporate governance environments; critically evaluate the effectiveness of the main corporate governance mechanisms and their impact on firm value; explain the potential consequences of weak corporate governance as well as behavioural biases on corporate decision making and firm value; analyse the development of corporate social responsibility. SYLLABUS CONTENTDefining corporate governance and key theoretical modelsCorporate control across the world – Control versus ownership rightsTaxonomies of corporate governance systemsBoards of directorsThe disciplining of badly performing managers under different systems of corporate governance Corporate governance regulation in an international contextCorporate governance in emerging marketsBehavioural biases and corporate governanceCorporate social responsibility and socially responsible investment READINGGoergen, M. (2018), Corporate Governance. A Global Perspective. Andover: Cengage EMA, ISBN 978-1-473-75917-6.

Defining corporate governance and key theoretical modelsGoergen (2018), chapter 1.

Corporate control across the world Control versus ownership rightsGoergen (2018), chapters 2-3.

Taxonomies of corporate governance systemsGoergen (2018), chapter 4.

Boards of directorsGoergen (2018), chapter 7.Incentivising managers and disciplining badly performing managersGoergen (2018), chapter 8.

Corporate governance regulation in an international contextGoergen (2018), chapter 6.

Further resources

An extensive library covering most national and international codes of corporate governance can be found on the website of the European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI): http://www.ecgi.global/content/codes Corporate governance in emerging marketsGoergen (2018), chapter 9.

Behavioural biases and corporate governanceGoergen (2018), chapter 12.

Corporate social responsibility and socially responsible investmentGoergen (2018), chapter 13.

ADDITIONAL MODULE RESOURCESPowerPoint Slides

100 multiple choice questions

End-of-chapter discussion questions and exercises – Instructor’s manual

European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI)

Andrei Shleifer’s dataset website with investor protection and anti-director rights indices

Social Sciences Research Network

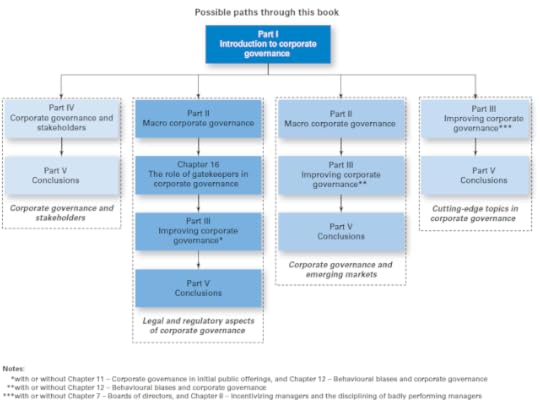

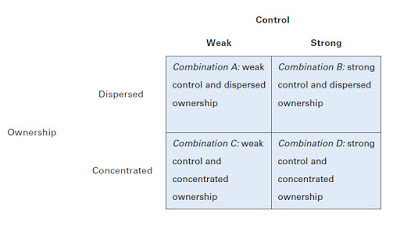

NOTEThe above module outline is just one of the many paths through Goergen (2018). There are others, some of which are depicted in the diagram below.

Defining corporate governance and key theoretical modelsGoergen (2018), chapter 1.

Corporate control across the world Control versus ownership rightsGoergen (2018), chapters 2-3.

Taxonomies of corporate governance systemsGoergen (2018), chapter 4.

Boards of directorsGoergen (2018), chapter 7.Incentivising managers and disciplining badly performing managersGoergen (2018), chapter 8.

Corporate governance regulation in an international contextGoergen (2018), chapter 6.

Further resources

An extensive library covering most national and international codes of corporate governance can be found on the website of the European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI): http://www.ecgi.global/content/codes Corporate governance in emerging marketsGoergen (2018), chapter 9.

Behavioural biases and corporate governanceGoergen (2018), chapter 12.

Corporate social responsibility and socially responsible investmentGoergen (2018), chapter 13.

ADDITIONAL MODULE RESOURCESPowerPoint Slides

100 multiple choice questions

End-of-chapter discussion questions and exercises – Instructor’s manual

European Corporate Governance Institute (ECGI)

Andrei Shleifer’s dataset website with investor protection and anti-director rights indices

Social Sciences Research Network

NOTEThe above module outline is just one of the many paths through Goergen (2018). There are others, some of which are depicted in the diagram below.

Published on May 08, 2018 12:25

March 7, 2018

Dos and Don'ts of Approaching a Potential PhD Supervisor

Similar to most academics, I get lots of unsolicited emails from potential PhD students asking me whether I would be willing to supervise them. Hence, I thought I should put together the Dos and Don'ts of doing this. table { font-family: arial, sans-serif; border-collapse: collapse; width: 100%; } td, th { border: 1px solid #dddddd; text-align: left; vertical-align: top; padding: 8px; } tr:nth-child(even) { background-color: #dddddd; } Dos Don'ts Email only potential supervisors in your area of research. Email everybody in the department or school. Start your email with "Dear Sir or Madam". Specify a topic that is of interest to you. Be as specific as possible. Ideally, you should attach a detailed research proposal to your email. State that you want to do a PhD in an area as large and vague as e.g. finance. Write that, since the age of 5, it has been your dream to do a PhD. (I didn't know what a PhD was at that age!) This is not a great start. The choice of the university is an important consideration. So is identifying a suitable supervisor. Do your research by consulting staff profiles. Choose a supervisor who is research active in your field of interest. Email a potential supervisor without consulting their staff profile first. Email somebody praising them for being a specialist in e.g. management accounting when in actual fact they specialise in corporate governance. Attach a research proposal with a comprehensive and up-to-date literature review to your email. Send out a literature review which fails to cover the most recent literature or – worse even – the addressee's own research in the area (OUCH!). Ensure your research proposal is free of typographical, grammatical, punctuation and stylistic errors. Send out a research proposal that is difficult to read, badly presented and riddled with errors. Attach a list of references (bibliography) which is in a consistent style (e.g. Harvard referencing style). Include a bibliography that is messy, incomplete and inconsistent. Often potential supervisor first look at your list of references to get a quick impression about your profile! A big part of doing PhD research is being able to get the details rights and to be conscientious. Spell check your email. Send an email full of spelling and grammatical errors. Misspell the addressee's name.

Published on March 07, 2018 07:44

March 5, 2018

Corporate Governance Case Studies

These case studies can be done once you have read Part I of my textbook "Corporate Governance. A Global Perspective". I suggest you read all three chapters, with a particular focus on the third chapter.

If you are a lecturer, you may use these case studies in class to help your students understand the theoretical concepts discussed in Part I of the textbook. All the following case studies illustrate how the large shareholder in listed European and US companies manages to have strong control while holding much less ownership.

DGMT Plc

Oohh Danone - More than just a yoghurt

Google Inc. - Google has now been restructured and Larry Page and Sergey Brin's holdings are now in Alphabet Inc., the parent company of Google. However, the stylised facts about Google as uncovered by this case study still apply to Alphabet Inc.

If you are a lecturer, you may use these case studies in class to help your students understand the theoretical concepts discussed in Part I of the textbook. All the following case studies illustrate how the large shareholder in listed European and US companies manages to have strong control while holding much less ownership.

DGMT Plc

Oohh Danone - More than just a yoghurt

Google Inc. - Google has now been restructured and Larry Page and Sergey Brin's holdings are now in Alphabet Inc., the parent company of Google. However, the stylised facts about Google as uncovered by this case study still apply to Alphabet Inc.

Published on March 05, 2018 01:10

December 30, 2017

DMGT Plc - Not your typical UK Plc

I haven't posted any of these corporate governance case studies for a while. As the updated version of my corporate governance textbook is about to be published on 11 March 2018, I thought it was a good time to investigate the corporate governance of another interesting company. The company I have chosen is the Daily Mail and General Trust Plc (DMGT Plc), a UK company. This is a media company which owns a.o. the tabloid

The Daily Mail

and the free newspaper

Metro

. It also has a holding in Euromoney Institutional Plc and Zoopla.

An example of a Daily Mail front page

An example of a Daily Mail front page

An example of a Metro front page

An example of a Metro front page

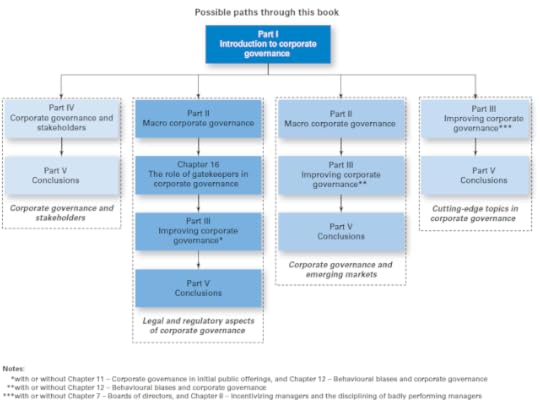

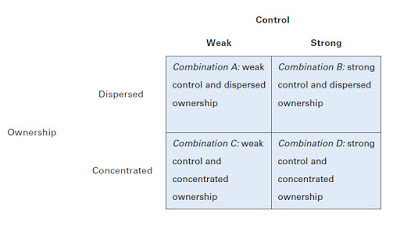

I chose DMGT Plc as it is not your run-of-the-mill UK stock-market listed Plc. The typical example of a UK exchange-listed corporation would be a Plc with dispersed ownership and weak control (see Section 3.3 of my textbook International Corporate Governance or its updated version Corporate Governance. A Global Perspective ). This is what I call combination A in my textbook (see below figure).

Combinations of control and ownership

Combinations of control and ownership

It what follows, I shall be using the 2017 annual report of DMGT Plc, which can be downloaded from here. The Chairman's Statement on Corporate Governance (see page 42) is informative as it suggests that DMGT Plc is a family company:

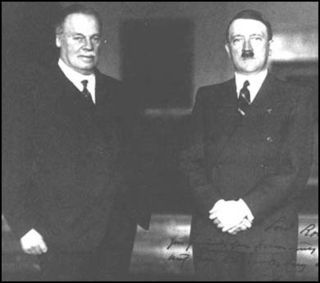

The First Viscount Rothermere (on the left)

The First Viscount Rothermere (on the left)

The rest of the Corporate Governance section is also interesting. For example, while the company complies with the recommendation of the UK Corporate Governance Code that the roles of the CEO and Chairman should be carried out by two different individuals, it does not comply with the Code's recommendation that half of the Board of Directors should be independent non-executive directors:

To sum up, Viscount Rothermere and his family control 100% of the votes in DMGT Plc. The question that arises is at which cost. In other words, what is the ownership of the Rothermere family in the DMGT Plc?

Let us return to the Remuneration Report, more specifically table 11 on page 70. The table reports the shareholdings of the directors, including Viscount Rothermere. The latter, as we already know, owns 19,890,364 or all of the ordinary shares making up 5% of the share capital as well as 61,644,654 A shares. Hence, Viscount Rothermere owns 5% + (61,644,654 / 342,204,470) x 95% = 22.11% of DMGT Plc's share capital. This violation of the one-share one-vote rule is atypical in the UK. More generally, DMGT Plc has dispersed ownership and strong control (see Section 3.4 of my textbook International Corporate Governance or its updated version Corporate Governance. A Global Perspective ). This is combination B in the above figure. It is achieved via dual-class shares whereby the large controlling shareholder (the Rothermeres) holds all the voting right and the non-voting shares are dispersed (except for the Rothermere holding of A shares). Funnily enough, a British media company with an anti-EU stance has very much the run-of-the-mill control and ownership structure of a substantial number of EU family firms!

DGMT Plc is not only interesting from a corporate governance point of view, but also from a political or institutional point of view. A relatively small shareholding confers the Rothermeres relatively important political power within the UK.

If you are a minority shareholder in DMGT Plc and worried about the risk of expropriation by the company's large shareholder do not fret as on page 56 there is the following statement:

Legal disclaimer: This blog reflects my personal opinion and not necessarily that of my employer. Any links to external websites are provided for information only and I am neither responsible nor do I endorse any of the information provided by these websites. If I have infringed any copyrights, this has been done inadvertently. Any photos under copyright will be removed once I have been notified of such copyright.

An example of a Daily Mail front page

An example of a Daily Mail front page An example of a Metro front page

An example of a Metro front pageI chose DMGT Plc as it is not your run-of-the-mill UK stock-market listed Plc. The typical example of a UK exchange-listed corporation would be a Plc with dispersed ownership and weak control (see Section 3.3 of my textbook International Corporate Governance or its updated version Corporate Governance. A Global Perspective ). This is what I call combination A in my textbook (see below figure).

Combinations of control and ownership

Combinations of control and ownershipIt what follows, I shall be using the 2017 annual report of DMGT Plc, which can be downloaded from here. The Chairman's Statement on Corporate Governance (see page 42) is informative as it suggests that DMGT Plc is a family company:

This already sets DMGT Plc apart from other, more typical UK Plc's. The Chairman is Jonathan Harmsworth, the fourth Viscount Rothermere, the great-grandson of the company's founder, the first Viscount Rothermere. Actually, every holder of the title Viscount Rothermere has served as Chairman of DMGT Plc. The following page (page 43) gives us more information about the family shareholding:"DMGT’s approach to governance is distinctive, as in addition to typical corporate procedures, we are able to rely on and utilise the significant benefits from the family shareholding and the long-term view that this permits."

"Rothermere Continuation Limited (RCL) is a holding company incorporated in Bermuda. The main asset of RCL is its holding of DMGT Ordinary Shares. RCL is owned by a trust (Trust) which is held for the benefit of Lord Rothermere and his immediate family. Both RCL and the Trust are administered in Jersey, in the Channel Islands. The directors of RCL, of which there are seven, included two directors of DMGT during the reporting period: Lord Rothermere and François Morin."

The First Viscount Rothermere (on the left)

The First Viscount Rothermere (on the left)The rest of the Corporate Governance section is also interesting. For example, while the company complies with the recommendation of the UK Corporate Governance Code that the roles of the CEO and Chairman should be carried out by two different individuals, it does not comply with the Code's recommendation that half of the Board of Directors should be independent non-executive directors:

"The Board believes that its current composition is appropriate taking into account the heritage of the Group, the interests of our operating businesses represented on the Board, and that a good balance is achieved from the Board’s Non-Executive Directors in terms of skill and independence. The Board keeps this under review. Less than half of the Board are Independent Non-Executive Directors, which is not in line with provision B.1.2 of the Code."What follows contains detailed information about the board committees as well as the Remuneration Report. However, I am going to start with the Statutory Information on pages 81-83. First of all, Rothermere Continuation Limited (RCL) owns 100% of the ordinary shares. Second, DMGT Plc's share capital is composed of 5% of ordinary shares (or 19,890,364 ordinary shares of 12.5p each) (all owned by Rothermere) and 95% of A shares (or 342,204,470 A shares of 12.5p each). Hence, DMGT Plc is one of the UK listed Plc's with dual-class shares (see Section 3.3 of my textbook International Corporate Governance or its updated version Corporate Governance. A Global Perspective ). While the Corporate Governance section does not explicitly state that A shares have no voting rights (all it does is to state that ordinary shares have voting rights), footnote 38 on page 169 clearly states the following:

"The two classes of shares are equal in all respects, except that the A Ordinary Non-Voting Shares do not have voting rights and hence their holders are not entitled to vote at general meetings of the Company."So never fully rely on the Corporate Governance statement. To be fair the Corporate Governance section on page 81 refers to footnote 38, but who does read footnotes (especially those placed much further down the company report)?

To sum up, Viscount Rothermere and his family control 100% of the votes in DMGT Plc. The question that arises is at which cost. In other words, what is the ownership of the Rothermere family in the DMGT Plc?

Let us return to the Remuneration Report, more specifically table 11 on page 70. The table reports the shareholdings of the directors, including Viscount Rothermere. The latter, as we already know, owns 19,890,364 or all of the ordinary shares making up 5% of the share capital as well as 61,644,654 A shares. Hence, Viscount Rothermere owns 5% + (61,644,654 / 342,204,470) x 95% = 22.11% of DMGT Plc's share capital. This violation of the one-share one-vote rule is atypical in the UK. More generally, DMGT Plc has dispersed ownership and strong control (see Section 3.4 of my textbook International Corporate Governance or its updated version Corporate Governance. A Global Perspective ). This is combination B in the above figure. It is achieved via dual-class shares whereby the large controlling shareholder (the Rothermeres) holds all the voting right and the non-voting shares are dispersed (except for the Rothermere holding of A shares). Funnily enough, a British media company with an anti-EU stance has very much the run-of-the-mill control and ownership structure of a substantial number of EU family firms!

DGMT Plc is not only interesting from a corporate governance point of view, but also from a political or institutional point of view. A relatively small shareholding confers the Rothermeres relatively important political power within the UK.

If you are a minority shareholder in DMGT Plc and worried about the risk of expropriation by the company's large shareholder do not fret as on page 56 there is the following statement:

"The Chairman of the [Remuneration & Nominations] Committee is Lord Rothermere and the majority of its members are not considered to be independent under the Code. Although this does not meet Code Provision B.2.1, as holder of all the Ordinary Shares of the Company through the Trust, the Board considers that Lord Rothermere’s interests are fully aligned with those of other shareholders. [...]"I hope you enjoyed this case study! While corporate governance reports contained in UK annual company reports have improved massively in recent years, the above case study nevertheless illustrates that a bit of detective work may still be required. This case study also illustrates that individual companies may deviate substantially from national norms in terms of ownership, control and governance.

Legal disclaimer: This blog reflects my personal opinion and not necessarily that of my employer. Any links to external websites are provided for information only and I am neither responsible nor do I endorse any of the information provided by these websites. If I have infringed any copyrights, this has been done inadvertently. Any photos under copyright will be removed once I have been notified of such copyright.

Published on December 30, 2017 09:27

December 12, 2017

Changes to Cengage Edition "Corporate Governance. A Global Perspective"

The Cengage edition entitled "Corporate Governance. A Global Perspective" is an improved and updated version of "International Corporate Governance" published by Pearson Prentice Hall in 2012. The table of contents of the Cengage edition can be found here. The Cengage edition is due to be published in March 2018.Changes to Cengage EditionThe structure of the textbook has changed to improve the flow throughout the book. Part II, which used to be entitled “International Corporate Governance”, is now called “Macro Corporate Governance”. Parts III and IV have been swapped around to improve progression through the book. Chapter 5 on “Incentivising Managers and the Disciplining of Badly Performing Managers”, which used to be in Part II, has been moved to Part III. A new chapter, Chapter 7 on “Boards of Directors”, including some of the material which used to be in old Chapter 5, has also been added to Part III. Throughout the book, many of the case studies in the textboxes have been replaced with more up-to-date material. In addition, errors, omissions and inaccuracies that were spotted by the author and various users of the text have also been corrected. The glossary has also been updated to include terminology used in the new material. While it is not feasible to provide an exhaustive list of all the changes made, in what follows I provide a summary of the main changes made to each chapter. The definition of corporate governance in Chapter 1 – which is used throughout this book – now distinguishes between four types of conflicts of interests rather than just three. Indeed, the conflict of interests between the providers of finance and the managers has been broken up into the conflict between the shareholders and the managers and the conflict between the shareholders and the debtholders. The definitions of ownership and control have also been clarified and the discussion of the agency problem of debt has been improved. Finally, an appendix has been added to Chapter 1. The appendix contains an extensive discussion of the theoretical framework underlying the Jensen and Meckling (1976) paper.

Jensen, M. and W. Meckling (1976), ‘Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Capital Structure’, Journal of Financial Economics 3, 305–360.

Jensen, M. and W. Meckling (1976), ‘Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Capital Structure’, Journal of Financial Economics 3, 305–360.

Published on December 12, 2017 11:36