Jonathan Chait's Blog, page 45

June 14, 2011

In Case You Missed The Debate

This Michael Scherer recap of the Republican debate is so good that I project Scherer will soon be doing nothing other than recapping events. A couple excerpts:

20 to 25 minutes. A question about the Tea Party. The response: everyone onstage likes the Tea Party. Even King likes the Tea Party. He takes the opportunity to plug an upcoming Tea Party debate on CNN.

26 to 29 minutes. A question about manufacturing policy. Paul says the answer is changing monetary policy. Pawlenty says he grew up in a meatpacking town and that Obamacare is bad. Bachmann says she would lower the corporate tax rate and gut the Environmental Protection Agency. Santorum says he comes from the Steel Valley and that he would cut the capital gains tax.

Bushism And The GOP Today

Ryan Lizza notes that last night's Republican debate reflected, in large part, the triumph of a faction of right-wing dissidents from the Bush administration:

On nearly every major issue, Bush haunted the stage. A hallmark of Bush’s post-September 11th leadership was a public-relations offensive to show the world that America did not discriminate against Muslims. Just six days after the terrorist attacks, Bush visited the Islamic Center of Washington, D.C., on Massachusetts Avenue, and talked about interfaith coöperation. “These acts of violence against innocents violate the fundamental tenets of the Islamic faith,” Bush said. “And it’s important for my fellow Americans to understand that.” Bush quoted the Koran, and used language he would repeat for years: “That’s not what Islam is all about. Islam is peace.” No Republican Presidential candidate uses anything close to Bush’s old formulation when talking about Islam these days...

When it came to foreign policy, there was another notable moment of backlash against the Bush years. A voter named John Brown asked, “Osama bin Laden is dead. We’ve been in Afghanistan for ten years. Isn’t it time to bring our combat troops home from Afghanistan?” Not long ago, most Republicans answered such a question by immediately declaring that troops could not come home until victory on the battlefield was achieved. Nobody used that formulation last night...

Afghanistan was not the only issue on which candidates sounded a lot less like George W. Bush and more like Ron Paul. When it comes to government spending and bailouts, the issue that burns the hottest among conservatives these days, the candidates came alive with stinging rebukes of policies that all began in the Bush years. Romney called the bailouts a failure and accurately pointed out “the Bush administration and the Obama administration wrote checks to the auto industry” before he attacked that policy.

“We should not have had a TARP,” former Pennsylvania Senator Rick Santorum added. “We should not have had the auto bailout. Governor Romney’s right. They could have gone through a structured bankruptcy without the federal government.” He did not point out that every dime of TARP money Obama used was appropriated by a Republican congress and signed into law by George W. Bush.

Michele Bachmann, who impressed many commentators last night, made the clearest statement about how the current anti-Bush surge of populism among Republicans actually began in the last days of that Administration. “I was behind closed doors with Secretary Paulson when he came and made the extraordinary, never-before-made request to Congress: Give us a seven-hundred-billion-dollar blank check with no strings attached,” she said. “And I fought behind closed doors against my own party on TARP. It was a wrong vote then. It’s continued to be a wrong vote since then. Sometimes that’s what you have to do. You have to take principle over your party.” What she did not need to say is that the views of her once-maligned faction have now taken over the party of George W. Bush.

Of course, this doesn't hold true on every issue. As Ross Douthat notes, there was nothing whatsoever for anyone "who would like America’s opposition party to advance an domestic policy agenda that consists of more than just capital gains tax cuts and corporate tax cuts, rinse and repeat." I suppose the conservative analysis is that trying to court non-extremist Muslims failed, TARP failed, the auto bailout failed, but the policy of regressive tax cuts plus industry-friendly regulation was a huge macroeconomic success that needs to be tried with even more vigor.

The GOP's Missing Man

The biggest question of the Republican presidential campaign is: What will Paul Ryan do? Ryan has come to dominate the Republican Party's agenda and has personally become a totem -- a sort of mini-Reagan figure, frequently cited as credibility by others and never attacked. As , Ryan was cited ten times in last night's debate.

I continue to think that the prospects of Ryan running are higher than most estimate, and that he would almost instantly attain front-runner status. In the meantime, he seems to almost dominate the current presidential candidates through his absence.

Bachmann's Health Care Whopper

One pseudo-fact from last night that's worth pointing out, as it's sure to recur many times, is Michelle Bachmann's claim that the Congressional Budget Office estimated that the Affordable Care Act would destroy 800,000 jobs. I wrote about this in February. The short answer is that CBO found nothing of the sort.

CBO estimated that 800,000 people would leave the workforce because they no longer would need to work in order to get health insurance. Under the status quo, it's very hard for people who aren't elderly or poor enough to qualify for Medicaid to obtain health insurance. Some of those people would like to retire, or work part time, but cannot due to the need to get employer-provided insurance. The Affordable Care Act would liberate them. The Republican budget would force those 800,000 people who otherwise have the means to retire or work on their own to work for their health insurance. Freedom!

June 13, 2011

A Few Notes On The GOP Debate

A recurrent Chait blog theme that looked good tonight: Pay attention to Michelle Bachmann. I was not surprised by her performance, but everybody else was.

A recurrent Chait blog theme that looked bad tonight: Tim Pawlenty as front-runner. Boy, did he look weak, especially when he refused to defend his "Obamneycare" line. There's going to be a wimp narrative, and Republicans like their men manly.

A few thoughts on substance --

Pawlenty defended his promise of 5% annual growth by saying China did it, therefore we can too. That's ridiculous. There's huge growth potential in moving people from small farms to factories. But there's no record of advanced industrialized economies growing at such a sustained pace.

Mitt Romney was incoherent on the auto bailout in ways that merit further exploration. He began by lambasting the Obama administration's auto bailout as just handing out money. But then, pressed about his prediction that a bailout would destroy the industry, he insisted he was saying this would only happen if the government handed out money to the automakers wantonly. The implication, then, is that Obama avoided the mistake that Romney had just accused him of committing. I'd love to hear this teased out at more length.

Pawlenty's answer on the separation of church and state underscored the degree to which the concept of separation of church and state has lost all legitimacy on the right. Pawlenty depicted religious liberty as solely applying to religious Americans fearing an anti-religious government.

Newt Gingrich seemed to approach my parody Newt breakthrough proposalby talking up tax credits to encourage exploring outer space. No dinosaurs, sadly.

JONATHAN CHAIT >>

&c

-- Justin Driver offers a new argument about Obama's legal philosophy.

-- Obama remains competitive in North Carolina.

-- John Kasich is not bitter about LeBron leaving the Cavaliers. Not at all.

Pawlenty: Bush Tax Cuts? Never Heard Of 'Em!

Dave Weigel asks Tim Pawlenty why, given that the Bush tax cuts failed to boost growth or revenue, he believes that deepening those same tax cuts would produce such spectacular results:

"After the Bush tax cuts we got slightly less revenue, we got a larger debt," I asked. "You're talking about tax cuts as part of a larger plan that will grow the economy, reduce the deficit over the long term. Why would that work when the Bush tax cuts didn't?"

"Keep in mind," said Pawlenty, "our plan does not just cut taxes. It cuts spending. Big time. So as people look back to the historical examples, there's been other chapters where tax cuts have been enacted, and almost always they raise revenues if you just isolate the effect of the tax cuts. But I think they didn't fully serve their intended purposes, because at the same time, past Congresses and administrations also raised spending. That's not what we're proposing. We're not proposing to cut taxes and raise spending. We're proposing to cut taxes and cut spending, and if you do that we're going to grow jobs by shrinking government. We're going to grow the private sector by shrinking government."

"On the revenue side," I said, "they [the Bush tax cuts] generated less revenue than the previous tax rates did. Why would your tax cuts generate more?"

"When Ronald Reagan cut taxes in a significant way," said Pawlenty, "revenues actually increased by almost 100 percent during his eight years as president. So this idea that significant, big tax cuts necessarily result in lower revenues -- history does not [bear] that out."

So first Pawlenty replies by citing spending, which does not address the objection that lower tax rates failed to goose growth. Weigel presses the point, and Pawlenty cites Reagan. Of course, Reagan's tax cuts don't really get around the objection. The higher a starting tax rate, the more supply-side punch a tax cut could have. Reagan reduced the top marginal tax rate from 70% to 28%, which is a powerful reduction. George W. Bush cut taxes starting from the Clinton-era level, a top rate of 39.6%, down to 35%. Pawlenty proposes to cut below the Bush level. Cutting to a rate lower than the Bush level should mean an even weaker return than than the return on Bush's tax cuts.

Anyway, the notion that Reagan's tax cuts produced a gusher of revenue is also pure nonsense, but nonsense that conservatives have been peddling for a couple decades. The basic story is that Reagan passed a huge tax cut in 1981. By 1982, the deficit was climbing to alarming levels, and the Reagan administration immediately began raising payroll taxes in 1982 and 1983, partially but not completely stanching the loss of revenue.

The claim that revenue doubled is totally false. If you look at total revenue, it increased by 65% from 1981 through 1989. That's probably where Pawlenty got his "almost 100 percent" figure. But there are some huge problems with even that number. That number is total tax revenue, which means that the payroll tax hikes are covering up for the income tax cuts. Second, and worse still, that's a raw dollar figure, failing to account for inflation, which is a very basic no-no. Real income tax revenue increased 14% from 1981 to 1989. That's, uh, way less than 100%.

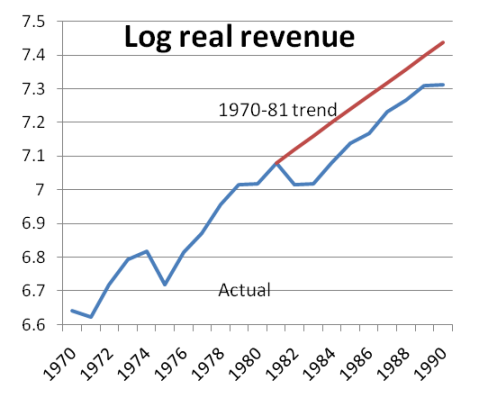

But wait! Even that increase is wildly misleading. After all, the United States is going to experience population growth and economic growth under virtually any income tax regime. Real tax revenue will grow if you keep the tax laws unchanged. (So will expenditures, for the same reason.) So to figure out what Reagan did to revenue, you need to compare it to the trend. Fortunately, Paul Krugman has done that for us:

I'm trying to think of more ways that Pawlenty is wrong, but I'm getting bored of this so I'll leave it there. Suffice it to say that he's wrong -- crazy wrong, climate change denial-wrong -- but also firmly in keeping with his party's orthodoxy. The utter failure of conservative predictions about the effects of the Clinton tax hikes (will destroy the economy, cause a recession and lead to less revenue) and the effects of the Bush tax cuts (will create a new economic boom) have left absolutely zero imprint upon the thinking of movement conservatives.

The Limits Of Romney's Economic Experience

Mitt Romney has garnered a lot of credit for crafting a perfectly-targeted general election message focusing on the economy:

[H]is narrow, economy-focused message appears to be resonating amid growing alarm about the unemployment rate – which rose above 9 percent the day after Romney declared his campaign.

Romney can continue to gain traction by presenting himself as an accomplished businessman and the savior of the Salt Lake City Olympics – a turnaround artist who can heal the country’s economic wounds.

There's a lot of truth here. The GOP's best chance to win the presidency is to position itself as the beneficiary of poor economic conditions, and Romney's campaign message recognizes that reality. It's also true that Romney is a smart, capable man who's comfortable designing effective technocratic solutions such as his Massachusetts health care plan. But it does not follow from this that Romney could actually provide better macroeconomic management than the current administration.

The first thing to keep in mind is that the economy is not just a problem where we need a businessman to come in and look under the hood. It's a contested ideological and political debate replete with competing analyses. What's relevant is not Romney's experience but what Romney plans to do as president. Thus far he has no plan at all. He campaign message is entirely focused on blaming Obama for an economic crisis he inherited without offering any alternative solutions:

At some point, Romney will have to put out a plan. That, in turn, will undercut the political salience of his managerial reputation. Any plan Romney endorses will have to be acceptable to the conservative base, which almost by definition means that it will fail by the standards of competent technocracy. The dominant strands of economic thought in the conservative movement are supply-side economics, Hooverism, and goldbuggery. Romney's plan will have to reflect some combination of those, at which point he'll be running as the advocate of a specific program rather than the guy who will do for America what he did at Bain Capital.

Next, even to limited the extent that we can apply Romney's business experience to his governing style, it does not necessarily auger well for him. Romney was a turnaround artist, which meant that he liquidated huge numbers of jobs in order to make firms profitable. I don't have any moral problem with this, and it certainly doesn't show that Romney is cold-hearted. The problem, rather, is that Romney's business experience lies in doing the same thing that has been happening to the economy writ large. Our economic problem isn't that our business can't make a profit, it's that the profit has failed to raise the living standards of most workers. What's good for a turnaround company is not necessarily good for a country as a whole. Or, at least, what the country needs from its government is to complement rather than accelerate the processes Romney unleashed in the private sector. It was fine for Romney the business executive to treat workers in a cold, unsentimental way -- as bumps in the road, as it were - but this is not so fine for the president of the United States.

Life In Ohio, A Continuing Series

[image error]The numerous Ohio parents who named their children after Buckeye football coach Jim Tressel do not seem to express any regret now that Tressel has resigned in disgrace over a mushrooming scandal:

Hearing a discussion play out on sports radio, 4-year-old Tressel Huffines wondered aloud to his father:

"Why are they talking bad about me, Daddy?"

The chatter, of course, centered on the man for whom the boy is named: Jim Tressel, who resigned as Ohio State football coach on Memorial Day.

The younger Huffines, a database of state birth records shows, is one of 20 Ohio newborns given the moniker Tressel since January 2003, when coach Tressel led the Buckeyes to the first national championship. ...

Despite that, parents of some of his namesakes aren't second-guessing themselves.

"Do I have any regrets? No," said Brent Huffines, 31, of Logan, who came up with the idea in 2007 and had to persuade his wife, Kattie, to go along.

"I think he got a raw deal, and she thinks he got a raw deal," the longtime Buckeye fan said. "Tressel was 9-1 against Michigan, and I still respect him off the field."

(A footnote: Their son's middle name - and that of four other young Tressels - is Hayes, a nod to another OSU football coach who departed under a cloud (of dust?). And Tressell Hays Ray, born in 2004, stands in a class of his own with the modified spellings of his first and middle names.)

Where The Facts Matter

notes that all spending is not created equal:

I would argue that at least half of America's military spending provides no benefit whatsoever to Americans outside the military-industrial welfare racket. But the other half may be doing some pretty important work. Rather than arguing dogmatically for a higher or lower level of total spending, it would be nice if we could focus a little and argue for and against the value of different kinds of spending, and then to focus a little more on the value of different ways of spending within budget categories. Some government spending gives folks stuff they want. Some government spending is worse than stealing money, throwing it in a hole and burning it. This is obvious when you think about it for a second, but it sometimes seems that partisan political discourse is based on the refusal to think about it at all. Conservatives with a libertarian edge often proceed as if government spending as such is an evil to resist, except when they're defending a free-lunch tax cut (we'll have more money to wrongly spend!) or the ongoing development of experimental underwater battle helicopters. And liberals with a social-democratic streak often operate within a framework of crypto-Keynesian mysticism according to which handing a dollar to government is like handing a fish to Jesus Christ, the ultimate multiplier of free lunches. When debate takes place on these silly terms, it seems almost impossible to articulate a vision of lean and limited government with principled, rock-solid support for spending on social insurance, education, basic research, essential infrastructure, and necessary defence, despite the likelihood that something along these lines is what most Americans want.

His policy diagnosis is exactly right. I'd disagree with the political diagnosis. Yes, we need to judge spending programs on their own terms -- some programs being highly useful, others minimally so, and others counterproductive. But what is the barrier to this ideal? Obviously, practical politics plays a huge role, with interest group politics protecting wasteful programs, and (along with inertia) blocking useful programs.

But ideologically, it seems to me, the problem lies almost entirely on the right. The mainstream conservative view of defense spending, which has some dissent on the right, regards every dollar of the pentagon budget as utterly sacrosanct, and any proposal to cut a dangerous effort to weaken America, probably motivated by (depending on what year it is) McGovernism or Forgetting 9/11 or disbelief in American Exceptionalism. There's also reflexive opposition to military spending, but this is a fairly marginal view. The coalition of people who want to subject military spending to a rational cost-benefit test tilts heavily left.

On domestic spending, the ideological asymmetry is even more stark. Nearly all conservatives reflexively oppose domestic spending. (Try going to National Review or the Heritage Foundation with evidence about the efficacy of subsidized early childhood education and see how far you get.) Wilkinson suggests a parallel between reflexive conservative opposition to domestic spending and "crypto-Keynesian mysticism according to which handing a dollar to government is like handing a fish to Jesus Christ." But this isn't a general liberal disposition. It's a liberal belief that applies only to to extremely rare emergencies, of which one has occurred since the 1930s. Even as committed a social democrat as Robert Kuttner thinks it's worthwhile to eliminate wasteful spending during normal economic circumstances.

Certainly, liberals are going to disagree with Wilkinson about what sorts of programs are necessary and useful and what the evidence tells us. But if he's advocating an intellectual process of measuring every spending program on its particular merits rather than relying on a priori support of or opposition to "spending," then liberalism is where it's at.

JONATHAN CHAIT >>

Jonathan Chait's Blog

- Jonathan Chait's profile

- 35 followers