Jonathan Chait's Blog, page 19

July 28, 2011

The Coin That Will Save The World

Somehow, I've missed out on a discussion of the coolest (and apparently legitimate) way to avoid a debt ceiling crisis:

Sovereign governments such as the United States can print new money. However, there's a statutory limit to the amount of paper currency that can be in circulation at any one time.

Ironically, there's no similar limit on the amount of coinage. A little-known statute gives the secretary of the Treasury the authority to issue platinum coins in any denomination. So some commentators have suggested that the Treasury create two $1 trillion coins, deposit them in its account in the Federal Reserve and write checks on the proceeds.

Trillion dollar coins! It's the Montgomery Burns Solution:

I actually feel like this plan could, in addition to rescuing the economy, provide the spark our film industry requires. I could sit here for ten minutes and rattle off a half-dozen great film concepts based on this story.

Bank caper: a dashing Clooney-esque figure assembles a team to steal the trillion dollar coin.

Comedy: a bumbling assistant Treasury Secretary played by Jack Black accidentally picks up the trillion dollar coin and spends it on a Mountain Dew, sending the entire government into a mad scramble for the coin before the world economy collapses.

Noir: Regular person somehow acquires the coin, and is slowly twisted.

Action: Super-villain plots to destroy the coin and bring the economy to its knees, from which he stands to profit due to a nefariously brilliant hedge he has prepared. Maybe we'll call him "Eric Cantor."

Go Back To Where You Came, Frum

I think everybody in my corner of the internet has a gentleman's understanding that pointing out the hilarious lies of the Wall Street Journal editorial page is my job. I got that job from Michael Kinsley. One day I hope to pass it on to somebody else. I don't take kindly to it when somebody takes my job. Especially when that somebody is a foreigner like David Frum:

I used to write editorials for the Wall Street Journal myself, 20 years ago now.

So I’m well aware of the challenge faced by those assigned to compose these documents. The strict demands of the paper’s ideology do not always lie smoothly over the rocky outcroppings of reality. It can take considerable skill to match the two together.

In that regard, this morning’s lead editorial about the debt-ceiling crisis is a true masterpiece.

If you were to write a story about government debt, you’d probably be inclined to write about the two sets of government decisions that produce deficits or surpluses: decisions about expenditure and decisions about revenue. You’d want to do that not only as a matter of fairness, but also as a matter of math.

And that’s why, my friend, you would wash out as a WSJ.

It's no fun to lose your job when an immigrant underbids your wages, but it's even less fun when a Canadian immigrant overbids your quality. I mean, this bit from Frum makes me want the INS to start checking the papers of all Canadian immigrants, and maybe conduct some surprise raids of sports bars during hockey season:

It must have taken some searching, but the Journal managed to find a chart vaguely relating to debt that went up under Clinton and stayed flat under Bush. They chose chart 11.1 from the historical tables of the Offices of Management and Budget. (That’s more information by the way than the Journal included – I guess they wanted to enhance the treasure-hunting fun of those curious to check their work.)

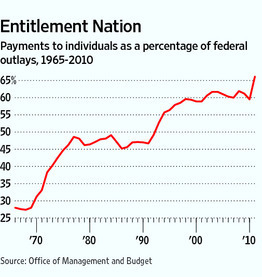

You can see the original of the chart here: “Summary Comparison of Outlays for Payments to Individuals, 1940-2016, as percentage of Total Outlays.”

What’s so great about this chart is that it excludes two of the biggest federal spending programs: Medicare Part B and Medicaid, both of whose costs rose faster in the Bush 2000s than in the Clinton 1990s. Isn’t that ingenious? Would you ever have thought of doing that? Again – that’s why you would wash out. This is not a job for just anyone.

Right, and pointing this out is not a job for you, Frum. Stay out.

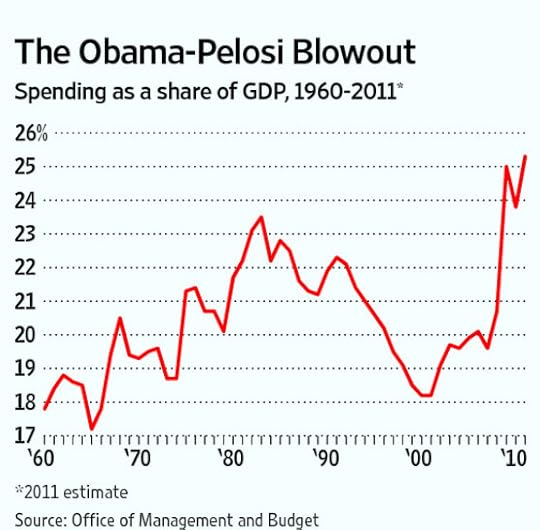

Anyway, despite the exceptionally strong job Frum has done -- and you can read the rest of his item for more still -- I wanted to gnaw on some of the meat Frum left on the bone. Check out this chart appearing in the same editorial:

Now, if you know much about budgeting, you know perfectly well that the chart does not measure an "Obama-Pelosi Blowout." In 2009, the economy cratered. That caused the denominator in the outlay/GDP percentage to shrink. Additionally, automatic stabilizers on programs like unemployment and food stamps skyrocketed as the need spiked. None of these things represented decisions by Obama and Pelosi (or Harry Reid, curiously absent.) It's true that they did pass an economic stimulus with temporary spending that contributed further to the rise on spending asd a percentage in GDP, but the Journal does not disaggregate the effects, instead pretending the whole rise resulted from Democratic choices.

Next, note the scale on the Journal's chart. It's very tight, with a bottom bound of 17% and a top bound of 26%, so that changes of a few percentage points of GDP appear gigantic. For an interesting contrast, here's how the Journal does it when it wants to make the changes look small. A hardy Journal perennial going back at least a couple decades is the chart purporting to show that revenue never really changes that much -- i.e., low tax rates and high tax rates produce about the same amount of revenue. For instance:

Notice the scale here goes from 0 to 90, so that even pretty large changes look like tiny blips. This is one of the first tricks I remember reading about in "How To Lie With Statistics" in college. You play with the scale of the chart to make changes appear as large or as small as you desire.

Meanwhile, maybe Frum can go point out some logical error in the National Post's editorial on lumber tariffs.

Rep. Joe Walsh: I Can't Complain But Sometimes I Still Do

I don't usually get excited about personal scandal stories, but the hypocrisy in this report about Rep. Joe Walsh is just too enjoyable:

Freshman U.S. Rep. Joe Walsh, a tax-bashing Tea Party champion who sharply lectures President Barack Obama and other Democrats on fiscal responsibility, owes more than $100,000 in child support to his ex-wife and three children, according to documents his ex-wife filed in their divorce case in December.

“I won’t place one more dollar of debt upon the backs of my kids and grandkids unless we structurally reform the way this town spends money!” Walsh says directly into the camera in his viral video lecturing Obama on the need to get the nation’s finances in order.

Life's been good.

How And Why The Boehner Bill Matters

Yesterday I argued that John Boehner's (apparently) successful taming of the right-wing insurgency within his party represents an important step toward the eventual solution of the debt ceiling crisis. Jonathan Cohn is more cautious, and guest posting Norm Ornstein is downright morose:

[A] speaker can only go to the well once or twice to get his or her members to walk the plank. In this case, Boehner’s tactical maneuvers mean that he is asking two dozen or more of his colleagues to walk that plank in return for something that has no chance of becoming law. Instead, it is a vote to give him the barest amount of additional traction to cut a deal for a plan that will dilute even further the package that they are on record condemning for its weakness. Many of the reluctants will not be willing to walk the plank a second time for the compromise. So Boehner will face another crossroads—will he be willing to bring up and push for a plan that will require almost as many Democrats as Republicans, to make up for the defections in his own ranks?

That's certainly true, though we have to keep in mind that since the voting coalition for the eventual debt ceiling bill will be different -- involving many democrats and many fewer Republicans -- Boehner can afford to lose a lot of the conservatives he's cajoling this time.

Boehner is going to pass this bill by skillfully appealing to raw partisan tribalism. (GOP member of Congress: "Let's knock the shit out of them!") He'll need a very different approach to actually lift the debt ceiling -- assuming Senate Democrats and President Obama don't just cave and support his bill, which I'm nearly sure they won't.

If this bill is not going to be signed into law, what does it mean? Mainly, I think it provides Republicans with a P.R. message if (and I'd say when) we pass August 2nd without a deal. hey'll say they passed a bill, they're not the problem, the Democrats are the problem. Then it becomes a he-said, she-said fight over which party is to blame. Now, the Republican message there is ridiculous, but it is a message.

The reason I think this is bad news is that the Boehner vote will give Republicans confidence to head into a debt ceiling message war and avoid total blame for the fiasco. They may or may not be right about it, but they're going to try to go past August 2nd and see if they can fight the public opinion war to a stalemate. Then they can force Democrats to bend. If they could not pass the Boehner bill, then they'd face pressure to just pass a clean debt ceiling hike earlier.

I understand that I'm making complicated arguments. The only debt ceiling bill that can pass the Senate and get Obama's signature is a bill that Boehner is going to need lots of Democratic votes to pass. In sum, it's good that Boehner has gotten the extremists to move off their most extreme stance on the debt ceiling. But it would be bad if the bill passes the House, as it will set up gridlock and a showdown that gets less likely to solve.

THE DEBT CEILING >>

The Four Kinds Of Pro-Electoral College Arguments

Rick Hertzberg continues his thankless, vital lonely job of carefully refuting every argument raised against the National Popular Vote plan. For instance, one op-ed asserts:

Rick Hertzberg continues his thankless, vital lonely job of carefully refuting every argument raised against the National Popular Vote plan. For instance, one op-ed asserts:

Under NPV, the necessary plurality could be confined to a few states, or a single region of the country. Multiple regional or even favorite-son candidacies would be encouraged, and each new candidacy would increase the likelihood of one of them receiving a majority of the electoral votes (courtesy of the NPV compact) while capturing a very low percentage of the overall vote. If there were four major candidates in the race, victory could be achieved with just over 25% of the popular vote.

Hertzberg replies, with more patience than I could muster:

If it were true that popular-vote elections encourage multiple candidacies, we would expect to see multiple candidates in the popular-vote elections we already have, such as gubernatorial and Senate races. We see no such thing.

As for regional candidates, the current system—state by state, with the plurality winner in each state getting 100 per cent of that state’s electoral votes—is actually more hospitable to them, because, by giving such candidates a shot at winning electoral votes, it opens up the possibility that no candidate will win an overall electoral-vote majority, thereby throwing the election into the House of Representatives (where, under the Constitution, each state delegation would get one vote regardless of size). In 1968, George Wallace won 46 electoral votes. In 1948, Strom Thurmond (who got less than two and a half per cent of the national popular vote) won 39 electoral votes. Both were regional candidates, the region being the old Confederacy. (In 1948, by the way, Henry Wallace, a non-regional candidate, got about the same popular-vote percentage as Thurmond but zero electoral votes.)

Sracic is correct that under N.P.V. a candidate could, in theory, win a four-candidate election with a hair over 25 per cent of the popular vote, let’s say 25.1 per cent—but only if each of the other three candidates got exactly 24.96 per cent.

Reading Hertzberg's arguments on this topic, I've come to notice that anti-N.P.V. arguments fall into four categories. You have assumptions that anything the Founders created must ipso-facto be correct. (Bring back the three-fifths rule!) You have arguments based on partisan motive, usually impugning liberals for being bitter about 2000. You have arguments based on lazy misrepresentation of the details of the N.P.V. plan. And fourth, and most common, you have arguments like the one Hertzberg takes apart here, which consist of imagining possible adverse scenarios under an N.P.V. These arguments tend to have certain things in common. They don't assess the likelihood of an adverse scenario, they just invoke it. And they don't balance the possibility of an adverse scenario against the actually existing adverse scenarios arising from the current system.

The last part is really key. Suppose we had a national popular vote, and somebody proposed to change the system to state-by-state winner take all elections. You could raise some really scary scenarios, couldn't you? The less-popular candidate could win! Electors could defect and ignore the voters' instructions! A state legislature could threaten to vote for its favored partisan and ignore the voters completely! Candidates would spend all their time in the dozen closest states and ignore most of the country! Why would we want to set up a method that results in people flying across the country to knock on doors in Ohio or Florida and ignoring their own neighborhood?

That's without even invoking disasters that have not occurred, such as a 269-269 tie, or a candidate who loses the popular vote badly but squeaks into the presidency by concentrating his support in half the states.

Those arguments would be persuasive. Indeed, it would be pretty hard to muster any positive arguments for this reform at all. That's why nobody actually implements it in other countries. And that's why states don't consider getting rid of statewide voting for governor and breaking up the vote into district-by-district winner take all blocs. Because, in other words, the electoral college is terrible.

Please, Boehner and McConnell, Don't Fight In Front Of Jennifer Rubin

A couple weeks ago, Mitch McConnell leaked his debt ceiling plan to Jennifer Rubin. She defended it assiduously. It was a brilliant idea, perfection itself. If it had any flaw at all, it was merely that it was too brilliant for its critics to understand:

If there is a criticism of the McConnell plan it is that he vastly overestimated the ability of the political class to understand an out-of-the-box proposal. Maybe he could come up with a chart or a video.

Now John Boehner has a debt ceiling plan, and Jennifer Rubin also thinks it's utterly brilliant:

We know what happens if the Boehner bill fails in the House. There is no alternative plan. We suffer whatever shock to the U.S. and world economies that will follow a default. The president will go to the country, claiming the Republicans endangered the country’s economy and global standing. But what happens if the House passes the Boehner bill?

1. The Boehner bill becomes the inevitable solution to the crisis. As Keith Hennessey explains, we also make progress in restoring fiscal sanity. . . .

2. The House would have done its job without violating the core promises the speaker made: more spending cuts than dollars increased in the debt ceiling. And no tax hikes.

3. President Obama, after decrying the plan, will almost certainly have to sign it. This in no sense will be looked upon as a victory by Democrats. To the contrary, by ignoring the president’s veto threat, the House will have shown that its views (and those of its Tea Party freshmen) can’t be ignored by the White House.

4. Congress will rebuff Obama and Reid’s efforts to slash more than $800 billion in defense spending. It is for this reason that former ambassador to the U.N. John Bolton has endorsed the plan.

5. The rap on the Tea Party that it is incapable of governing will be proven false.

6. The rap that the Republicans are divided between the Tea Party and everyone else will be disproven as well.

7. The most shrill voices in the GOP will take one on the chin, and thereby reveal that the gap is actually between a few loud voices in the blogosphere and Congress, on one hand, and the bulk of the conservative movement, on the other. The Tea Party, however, will show it can move opinion and govern.

8. Obama won’t have any excuse for the rotten economy.

9. The left will be demoralized. The left demanded a clean debt bill, railed against spending cuts, and pleaded for tax hikes. They will have failed, and Obama, by signing the Boehner bill, will be the object of their ire.

10. The Senate Democrats, who failed to do their job in passing budgets in two successive years, will be forced to take a tough vote, which will either displease their base or, for certain senators, critical red state voters.

At some level you wonder why this is even controversial in Republican ranks.

There may have been even more wonderful things about the plan, but Rubin ran out of fingers.

Yet here is the odd thing. McConnell's plan is extremely different than Boehner's. McConnell extends the debt ceiling past the 2012 election without any required policy changes. Boehner does not extend the debt ceiling past the 2012 election, but does require substantial spending cuts plus a panel to propose additional deficit reduction. How can both of these be such wonderful ideas?

Indeed, it makes me wonder just what Rubin would consider the best possible plan. What if we took the longer debt ceiling extension from McConnell's plan and paired it with the immediate spending cuts from Boehner's plan? That would be, like, some ultra-super-perfect hybrid, right?

Except there is a plan like that. Harry Reid proposed it. But Rubin has denounced it as a "sham."

So now I'm really confused as to what the best approach here is. Perhaps I just lack Rubin's analytic capacities.

Does Anybody Here Speak Boehner?

I am trying to figure out what sort of factual circumstances could make this argument by John Boehner true:

I am trying to figure out what sort of factual circumstances could make this argument by John Boehner true:

“There are only three possible outcomes in this battle: President Obama gets his blank check; America defaults; or we call the president’s bluff by coming together and passing a bill that cuts spending and can pass in the United States Senate,” Boehner told the rank and file, according to aides to the speaker. “There is no other option."

Somebody explain this to me. So the first two options are "default" or "blank check." Default means failing to lift the debt ceiling. How, then, is lifting the debt ceiling without other changes a "blank check"? Was it a blank check for every other president who got a debt ceiling hike? If you want to limit the amount of money spent under Obama, why not just pass bills reducing expenditures? You could even specify your desired level of spending and refuse to authorize anything above that level.

Then we have Boehner's claim that only a bill that cuts spending can pass the Senate. Except the Senate majority leader has proposed a plan, with some bipartisan support, that would not cut spending. You could pass that. Indeed, the Boehner plan almost certainly can't pass the Senate.

The we have the bit about no other option." There are, obviously, a huge number of other options. Perhaps Boehner is suggesting that his caucus won't pass anything else, so there's no option other than the ones his House is willing to pass. But if that's the case, why is "blank check" one of the options? Is he saying that could pass the House? If so, let's pass it!

Sadly, I don't think Boehner is saying that. But I honestly have no idea what he's saying. I understand that he's attempting to present the options in such a way that his plan appears like the only reasonable option, but even the internal logic of his argument seems incoherent.

July 27, 2011

Boehner's No Good, Very Bad Day—And Its Consequences

[Guest post by Norman Ornstein:]

John Boehner had a very bad day Wednesday. First, the Congressional Budget Office eviscerated his debt limit plan, forcing him to scramble to come up with another $350 billion in discretionary budget cuts, which in turn means that Boehner will have to bring up his revised plan late—but also with less than the three days notice he pledged to allow for every significant piece of legislation brought before the House. Second, he is in full panic mode to come up with the 217 votes (not 218, because of vacancies) necessary to pass his plan through the House, facing a daunting arithmetical challenge: 59 of his 240 House Republicans have pledged themselves not to vote for a debt limit increase. He can aim for less than a handful of Democrats to counter defections.

So Boehner and his leadership team are pulling out all the stops, putting his full prestige on the line, to get members to renege on their ironclad pledges. Every speaker has these moments when getting to a bare majority is excruciatingly difficult, and it requires offering inducements or simple begging. But a speaker can only go to the well once or twice to get his or her members to walk the plank. In this case, Boehner’s tactical maneuvers mean that he is asking two dozen or more of his colleagues to walk that plank in return for something that has no chance of becoming law. Instead, it is a vote to give him the barest amount of additional traction to cut a deal for a plan that will dilute even further the package that they are on record condemning for its weakness. Many of the reluctants will not be willing to walk the plank a second time for the compromise. So Boehner will face another crossroads—will he be willing to bring up and push for a plan that will require almost as many Democrats as Republicans, to make up for the defections in his own ranks?

If Boehner wins the vote, it will be by the barest of margins, not exactly providing momentum for his position. If he loses, it increases the chances of a compromise that takes a few elements from his plan and many from Harry Reid’s. But a much weaker Boehner, having lost a big one in the House, will need even more Democrats than Republicans to push it through. The consequence if that fails? Awful for him now, not to mention his place in history. But far worse for the country.

&c

-- Things that are still true today.

-- Dan Savage threatens to Santorum Rick Santorum's first name, too.

-- Even if it’s not AAA, U.S. debt could still be the world’s benchmark.

-- What’s the Fed going to do, charge the Treasury an overdraft fee?

-- Bob Corker thinks that Harry Reid “has actually tried to put something forth to help solve this problem."

The Six Month Hostage Reprieve Is A Disaster

A lot of commentators have emphasized the similarities between John Boehner's debt ceiling plan and Harry Reid's. (See Nate Silver and, to a slightly lesser extent, Ezra Klein.) It's true that Reid imposes about the same level of cuts, and that both create a commission to adopt further deficit reduction. The one difference, though, is highly significant. Boehner would only extend the debt ceiling another six months, and hinge the next extension upon the adopting of a deficit-reduction plan by a bipartisan commission.

Republicans have repeatedly attacked President Obama for opposing this element for partisan reasons -- he doesn't want another debt ceiling fight before his election. Of course, if that's correct, then Republicans also have a partisan motivation here. But forget motive. Suppose you approach this question from a standpoint of perfect neutrality about either the outcome of the next election or the substantive policy outcome. Should you care whether we extend the debt ceiling for six months or for 18? Yes, you should care a lot. You should favor the Democratic approach.

Boehner's plan requires Democrats and Republicans to agree on $1.8 trillion in deficit reduction, or the debt ceiling won't be lifted. Of course, the very reason we're not passing a grand bargain right now is that the two parties can't agree -- Democrats want a mix of higher revenue and lower spending, while Republicans insist on reducing the deficit entirely on the spending side. There's no reason to think the outcome would be any different in six months.

So what's the rationale here? Well, Boehner gets to appease Republicans who don't like lifting the debt ceiling -- you get another crack at in in six months. He extends the financial and political chaos into an election year, threatening Obama (and threatening the economy in Obama's reelection year.) And it lets Republicans recreate the scenario we were just in -- they insist on total victory, and assume Democrats will compromise rather than allow disaster to ensue.

Today's Wall Street Journal editorial lays it out:

In the second stage, the House and Senate would convene a 12-member joint select committee with a deficit reduction goal of $1.8 trillion by November. The majority and minority of both chambers would each make three assignments, and any plan that secured seven votes or more would get an up-or-down vote in both chambers with no amendments.

The danger for the GOP is that the committee could end up proposing tax increases, since the committee's only remit is the deficit, not the larger fiscal landscape or the size of government. A poorly chosen Republican nominee could defect, and any structural change to entitlements almost certainly can't pass the Senate.

Then again, unless the plan passed, Mr. Obama couldn't request the additional $1.6 trillion debt ceiling increase that he would soon need.

Now, you can see the reason Republicans would like this idea. They want to cut entitlements, but they're afraid to do so unilaterally. They need Democratic cover. Many Democrats are willing to do that in return for higher revenue, but Republicans won't accept that. So their goal is to use the debt ceiling as a hostage, to force Democrats to give them cover on entitlement cuts without giving in on taxes.

It's a good plan for Republicans and a bad plan for Democrats. But it's also a bad plan for the United States of America. Conservatives have been pointing out that debt ceiling hikes are historically short term. That's true! But they're also historically routine votes, rather than high stakes hostage crises.

This is why the ratings agencies have said that Boehner's bill will probably lead to a downgrade and Reid's won't. That fact by itself seems to be an enormous factor.

Now, you might ask what the big difference is between postponing the next crisis six months and postponing it eighteen months. Ideally, we'd abolish the debt ceiling vote altogether, but I don't see Republicans agreeing to that. But I could see some reason for improvement. If Obama wins reelection, some Republicans may attribute it to their extremist posturing over the debt ceiling, and decide to take a more reasonable approach next time. And if Obama wins, some or all of the Bush tax cuts should have expired, considerably easing the debt picture. If a Republican wins, the House will forget all about its antipathy to raising the debt ceiling, and we'll just postpone the crisis until the next time we have a GOP House and a Democratic president. (And, hey, maybe President Perry will think to get rid of the debt ceiling.)

Jonathan Chait's Blog

- Jonathan Chait's profile

- 35 followers