Jonathan Chait's Blog, page 127

January 20, 2011

Vulgar Etymology Contest

Keach Hagey reports:

Rachel Donadio reported on that story for the New York Times yesterday in a piece that, while quite colorful, was still missing a few hues.

As Donadio told the Italy’s La Repubblica, the Times editors, citing the paper’s rules against vulgarity, forced her to cut out the wiretaps’ irresistible quote: “She was his little girl, I’m his piece of ass.”

I have an embarrassing confession -- I don't really understand that phrase. I know what it means, I just don't understand where it comes from, or why it means what it means. Especially the "piece" part.

Commenters, please explain this one for me as cleanly as possible. I will reprint the explanation that best combines the traits of being convincing and non-flithy.

January 19, 2011

Quote of the Day, Blaming Other People Edition

[Guest Post by Isaac Chotiner]

"Suppose, I mean just suppose everyone thought the same way you do," Dobbs says to Yossarian in Joseph Heller's Catch-22. "Then I'd be a damn fool to think any different," the latter responds. Michael Kinsley's column on Tuscon recalls this clever exchange while making an equally valid point.

It is, [Obama] said, “a time when we are far too eager to lay the blame for all that ails the world at the feet of those who think differently than we do.” This sounds like a noble sentiment. But who is to blame for what ails the world if not those who think differently? If those who think the same as you are responsible, it’s time to start thinking differently yourself.

&c

-- Jon Cohn analyzes the coming court battle over health care reform in TNR's first online cover story.

-- I concede defeat to Matt Yglesias on Jeb Bush.

-- Last October, Weber County, Utah attorneys said a police office was justified in fatally shooting a golf-club wielding suspect. What actually happened was a different story.

Republicans Learn To Hate The Filibuster

Brad notes, hilariously, that Republicans have been running the House for a week and they're already flip-flopping on the merits of the filibuster:

Earlier this morning, Republican House Majority Leader Eric Cantor kept insisting to reporters, "The Senate ought not to be a place where legislation goes into a dead end." (He said some variation of this three times.) Cantor's frustrated because the House is all set to repeal health care reform, and Harry Reid has said he's not even going to bother bringing the bill up for consideration in the still-barely-Democratic Senate. " The American people deserve a full hearing," Cantor said, "they deserve to see this legislation go to the Senate for a full vote."

Of course, the Senate isn't even blocking the bill they want, because even if it passed, President Obama would veto it. The Senate is merely blocking the message vote Republicans want to hold. They can't even hew to their principles when an ineffectual message vote is at stake!

I continue to believe that the filibuster will be eliminated or curtailed when Republicans gain simultaneous control of the House, the presidency, and more than 49 but fewer than 60 Senators. Conservatives have invested a lot of energy into defending the supermajority requirement in the Senate, but the ideological basis of that commitment is tissue-thin and will disappear as soon as it's inconvenient.

The bad news is that this move will allow a lot of right-wing legislation. The good news is that, eventually, it will allow liberal legislation that will gain public approval and stand the test of time better than right-wing legislation does.

The GOP Establishment Against Sarah Palin

Here's Wall Street Journal editorial page writer and conservative movement apparatchik Stephen Moore writing up the Draft Mike Pence movement:

Mr. Pence won the straw poll at a gathering of more than 1,000 social conservatives in Washington, D.C., over the summer—besting Newt Gingrich, Mike Huckabee, and presumptive front-runner Mitt Romney. One concern is what Sarah Palin's intentions are, since she would have a huge funding base if she runs. But the pro-Pence movement fears that she is highly polarizing and someone who would have a difficult time beating President Obama in the general election.

Moore is putting the anti-Palin fears in the words of Pence supporters, but in a way that tactitly endorses them. It seems like the elements within the Republican that aren't working against Palin are dwindling quickly.

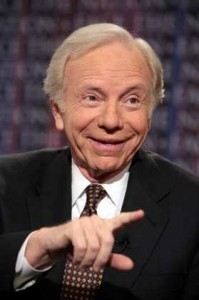

Predicting Lieberman's Future

Politicians who decide against running for office because they know they can't win almost never admit it. Unfortunately, they have to provide some reason, and that reason is often vague. Here's Joe Lieberman's today:

Politicians who decide against running for office because they know they can't win almost never admit it. Unfortunately, they have to provide some reason, and that reason is often vague. Here's Joe Lieberman's today:

The reason I have decided not to run for re-election in 2012 is best expressed in the wise words from Ecclesiastes: “To everything there is a season, and a time to every purpose under Heaven.” At the end of this term, I will have served 24 years in the U.S. Senate and 40 years in elective office. By my count, I have run at least 15 full-fledged political campaigns in Connecticut.

I believe this is what philosophers call "begging the question."

As to his future plans, Lieberman is vague:

I do not intend today to be the end of my career in public service. Having made this decision not to run enables me to spend the next two years in the Senate devoting the full measure of my energy and attention to getting things done for Connecticut and for our country. I will keep doing everything in my power to build strong bridges across party lines -- to keep our country safe, to win the wars we are in, and to make sure America’s leadership on the world stage is principled and strong. I will keep doing everything I can to keep our economy growing and get our national debt under control, to combat climate change, to end our dependency on foreign oil, and to reform our immigration laws. And when my Senate chapter draws to a close in 2013, I look forward to new opportunities that will allow me to continue to serve our country—and to stay engaged and involved in the causes that I have spent my career working on, and that I care so much about.

I'm guessing he has a sinecure at a foundation or think-tank dedicated to promoting hawkish foreign policy or centrism. The right-wing version of this career plan would be an AEI fellowship where he will produce a book and a series of op-eds on the theme I Did Not Leave The Democratic Party, The Democratic Party Left Me. The left-wing version is a Brookings fellowship consisting largely of providing quotes to the mainstream media bemoaning the decline of bipartisanship, punctuated by service on a large number of blue ribbon panels. Or, again, possibly some kind of foreign policy-centered think-tank.

Doc Fix Zombies Attack

At National Review, James Capretta and Yuval Levin continue to defend Republican hokum about the doc fix. When pressed by critics, they concede the basic details of the story -- the issue is a poorly-written 1997 law that accidentally slashed doctor pay, which Congress has been correcting ever since, and is not affected by the Affordable Care Act. Yet they continue to try to argue that the cost of fixing this is really a hidden cost of the Affordable Care Act. Why? Here's Capretta:

If Krugman’s analysis were accurate, why does Congress go through the annual agony of a “doc fix” at all? Why haven’t they just passed a permanent solution already and gotten it over with?

The answer is that, while Congress doesn’t want to cut physician fees, it hasn’t wanted to pile the costs onto the national debt either. What has held back a permanent solution is the inability to find $200–$300 billion in acceptable “offsets” to make sure a permanent fix doesn’t add to the deficit.

When President Obama assumed office, he wanted his health bill and a permanent “doc fix” too, but he didn’t have enough flimsy offsets to grease the way for them both. So he came up with a new “solution”: use the offsets to pave the way for Obamacare’s spending, and exempt the “doc fix” from the need for offsets at all. This would create the perception of “deficit reduction” from Obamacare even as an unfinanced “doc fix” ran up the deficit by an even larger amount.

At the end of the day, even some Senate Democrats balked at this shameless sleight of hand and blocked the effort to pass an unfinanced and permanent “doc fix.” But the issue remains very much unresolved, and the administration has yet to disavow their push from last year to pay higher physician fees with borrowed money.

and here's Levin:

Chait suggests here that the cost of the doc fix is just assumed to be incurred each year—that it’s basically part of the baseline. But if that were the case, why would Congress go through the painful process of passing it each year? They do it because the smaller annual doc fixes (which are not part of the baseline) are easier to offset with other spending cuts while a single permanent fix—which would add several hundred billion dollars to the national debt—would be more difficult to offset. Doctors’ groups don’t like the uncertainty of the annual fixes, and so when they were asked to support the Democrats’ health-care bill, they pressed for a permanent fix, despite the cost. In their first draft of the health-care bill, in July of 2009, House Democrats sought to include such a permanent fix in the bill itself, and believed that the tax increases in the bill and their various efforts to game the CBO process with promises of future cuts would be enough to offset the required cost. They were not. The CBO reported that, even with all the various taxes and gimmicks it contained, the draft of the bill that contained the permanent doc fix would increase the deficit by $239 billion over the subsequent decade. The agency also reported that the doc-fix component of that bill accounted for $228 billion of that amount. The solution was obvious. The permanent doc fix was removed from the bill, and the Democrats promised the doctor groups that they would pursue it in a separate measure—a measure that would enact a permanent doc fix without offsets, and so would add about $200 billion to the deficit. They tried to do that after passing the health-care bill (which is why Republicans at the time pressed this point, to make clear that they would consider the cost of such a fix part of the cost of the health-care overhaul), but as it turned out they could not even get enough Democratic votes in the Senate to pass such a measure.

The argument here is highly convoluted, but the issue is simple. First of all, the doc fix isn't really a new cost at all. The savings created in 1997 were unintended, and stopping them from going into effect isn't really a new cost, it's just the on-paper price of keeping current policy constant.

Second, Capretta and Levin are trying to construct a metaphysical distinction between an annual doc fix and a permanent doc fix. The practice ever since 1997 has been to have Congress cancel out the huge cut in physician reimbursement a year at a time. Obviously, doctors have been annoyed about having to go through this ritual every year. Democrats considered doing a decade's worth all at once. The downside, of course, is that they would have to come up with a decade's worth of savings all at once to offset this "cost." So they didn't. Instead they're reverting to the old practice of filling in the doc fix every year.

Capretta and Levin are trying to argue that, once Democrats considered doing a long-term doc fix, the issue somehow became part of the Affordable Care Act. Even though they decided to separate the two out, the cost of doing the same thing Congress has been doing since 1997 is now really a hidden cost of Obama's 2010 health care reform. That's really what they're arguing. By this logic, if Congress had ever considered adding funding for the Afghanistan war into the health care bill, then the Afghanistan War would also be a "hidden cost" of the Affordable Care Act. It's such obvious nonsense that anybody who repeats it has forfeited his claim to be taken seriously.

Levin, in his post, continues to argue that CBO and CMS find that the Affordable Care Act bends the health care cost curve up. He continues to conflate the difference between the level of health care spending and the rate of growth. The bill increases spending in the short term by adding 30 million Americans onto the insurance rolls. (This is largely, but not completely, offset by other cuts ion health care spending.) The rate of growth from then on is lower than under the status quo. The rest of Levin's argument on this point -- go read it, it's long -- is a continued attempt to conflate level of spending with rate of growth.

As I said, he's free to disagree with those findings -- they are only projections, and they could be wrong in either direction. But to say that they show the Affordable Care Act bends the cost curve upward is simply false.

What Is Health Care Repeal Really About?

Republican economic honcho Douglass Holtz-Eakin says that voting for repeal of the Affordable Care Act is really about putting in place some different kind of health care reform:

I am one of roughly 200 economists and other experts to sign an open letter expressing concern over the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) and arguing that the economic and budgetary outlook would be improved by repeal. Proponents of the PPACA are stridently making the case that repeal means that children and others with preexisting conditions will never get insurance policies, that seniors will pay too much for their drugs, and that insurance companies will run roughshod over the American landscape.

Nonsense. ...

Replacing PPACA with real health-care reform that delivers quality care at lower costs. That is what the repeal vote is really about.

You can see why Holtz-Eakin would emphasize this. The push for repeal reflects a belief by the GOP base that the Affordable Care Act is a monstrosity that must be destroyed at all costs. But that is a distinctly minority opinion, as the Washington Post poll notes:

Those who do not support the law are split about evenly between advocating for its complete repeal (33 percent), a partial repeal (35 percent) and a wait-and-see approach (30 percent).

If the repeal vote was "really about" putting some different reform into place, then it would have had some different reform in place. It doesn't. It has nothing. Why? Because agreeing on an alternate plan that can unite even just the Republicans (let alone win 60 Senate votes) and win public approval is really hard. I'm sure many Republicans truly think that they'll be able to implement some reform of their own after repealing the Affordable Care Act. But if they can't put a plan on the table now, there's no reason to think they ever will. Which is why the repeal vote is exactly what the bill says it is: a vote to restore the old status quo.

Why Did Lieberman Off Himself?

The retirement of Joe Lieberman is the culmination of a series of domestic repercussions of the Iraq war. The war estranged Lieberman from his party base, which gave rise to a liberal primary challenge in 2006. National Democrats supported Lieberman, but when he lost the primary, they lined up behind the fully-nominated Democrat, infuriating Lieberman and driving him away from his party.

The retirement of Joe Lieberman is the culmination of a series of domestic repercussions of the Iraq war. The war estranged Lieberman from his party base, which gave rise to a liberal primary challenge in 2006. National Democrats supported Lieberman, but when he lost the primary, they lined up behind the fully-nominated Democrat, infuriating Lieberman and driving him away from his party.

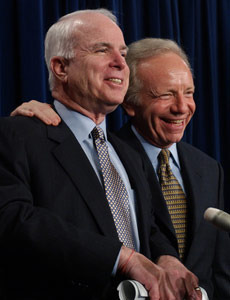

Lieberman's final departure from the party became inevitable when he supported, and enthusiastically campaigned for, John McCain in 2008. It's one thing for a Dixecrat in a Southern state to do that fifty years ago, but Connecticut is one of the more liberal states in the country. After that, Lieberman had no plausible path to return to the Senate.

The most interesting question may be why Lieberman took this suicidal path. My guess would be that he didn't consider it suicide. Lieberman is a true believing New Democrat who is influenced by the neoconservatives. One common thread uniting these two strands of thought is an overly-developed fear of McGovernism. George McGovern, the very liberal Democratic nominee in 1972, lost in a landslide, and his defeat ever since has been held up as evidence that middle America rejects and always will reject unvarnished liberalism. I think there's some truth to that but it's an oversimplified view.

The point, though, is that Lieberman is almost certainly a true believer in the legend. And you have to remember that, when Barack Obama won the Democratic nomination, a lot of centrists and neoconservatives viewed him as the heir to McGovern and a likely loser. In Lieberman's mind, I would submit, Obama was the heir to McGovern, and after he went down to defeat at the hands of popular maverick John McCain, Lieberman would be well-positioned to say "I told you so." He could then tell Democrats that only his brand of moderate Democratic politics could truly prevail, and the sadder but wiser party base would trudge back to his column.

Obviously, I'm speculating. It's highly unusual for a competent politician to take such a suicidal step. It's possibly Lieberman knew what he was doing when he sealed his own fate in 2008, but I think he really believed he could survive.

THE SENATE >>

January 18, 2011

&c

-- John Judis: the new GOP is unlike any political party we've ever seen.

-- Esquire's profile of Roger Ailes

-- McClatchy fact-checks the GOP claim that health care reform is a "job killer," with predictably hilarious results.

Jonathan Chait's Blog

- Jonathan Chait's profile

- 35 followers