Esther Crain's Blog, page 42

September 25, 2022

Capturing the magic of rainy nights in New York City

Hard rainy days in New York City can bring on a sense of melancholy—the grayness, the streets relatively empty of people, the steady pounding against windows.

But rain at night can hit the senses differently. Skies glow and obscure the skyline, and pavement slick with water almost twinkles under the lights of the city. There’s a painterly magic to it (if you’re not wrestling with an umbrella or trying to catch a cab, that is).

Few artists have captured this magic of a rainy New York night like Charles Hoffbauer. Born in France in 1875, Hoffbauer came to Gotham in the early 1900s, and with his Impressionist style painted many nocturnes of Manhattan under the spell of the rain.

These three Hoffbauer paintings are new discoveries for me. The exact date of each isn’t clear, but with both automobiles and horse-pulled carriages on the streets, I’d say the 1920s.

What part of New York is Hoffbauer showing us? Street signs and marquees are obscured, so it’s hard to know for sure. My guess is the theater district centered around Times Square.

September 22, 2022

Country houses left behind on Riverside Drive

After the first section of Riverside Drive—from 72nd to 126th Street—opened in 1880, this winding avenue that followed the gentle slope of Riverside Park became a study in contrasts.

Riverside Drive and 115th Street, after 1890

Riverside Drive and 115th Street, after 1890Up and down the Drive, wealthy New Yorkers and the developers who catered to them spent the next decades building well-appointed row houses, mansions, and early luxury apartment buildings. Yet on the fringes of this new millionaire’s colony stood crudely built shanties and shacks like the one in the photo above, homes to those whose fortunes didn’t rise during the Gilded Age and were forced to the margins.

This Dutch colonial style house, pictured at Riverside Drive and 145th Street in 1913, was popular in the late 18th and early 19th centuries

This Dutch colonial style house, pictured at Riverside Drive and 145th Street in 1913, was popular in the late 18th and early 19th centuriesAnother type of dwelling also held out here and there on Riverside Drive: country houses. These wood-frame houses with clapboard shutters and welcoming front porches may have been typical family homes in the early to mid-19th century, when the Upper West Side of today was a sparsely populated collection of small farming villages.

Development encroaches on this house, at Riverside Drive and 111th Street, in 1909

Development encroaches on this house, at Riverside Drive and 111th Street, in 1909That changed after Central Park was completed and the new elevated trains made what had was renamed the West End much more accessible. As the 20th century continued, Riverside Drive was extended into Upper Manhattan—threatening the handful of country houses that predated the Drive but were now in its way.

A pretty house at Riverside Drive and 86th Street, 1896

A pretty house at Riverside Drive and 86th Street, 1896None of these country homes pictured here survive today. Riverside Drive, with its unbroken lines of elegant apartment houses, doesn’t seem to miss them. Like so many early New York City houses, the stories of these anachronisms seem to be lost to the ages.

Join Ephemeral New York on Sunday, September 25 at 1 p.m. on a walking tour of Riverside Drive, which delves into the backstory of the country estates, mansions, and monuments of New York’s most beautiful avenue.

[Top photo: MCNY X2012.61.22.13; second, third, and fourth photos: New-York Historical Society]

The story of how the Bronx got its name

Manhattan is a corruption of the Native American word Mannahatta; Staten Island derives from Staaten Eylandt, named by the Dutch. Brooklyn is the anglicization of the Dutch village of Breukelen, and Queens comes from English Queen Catherine of Braganza, who happened to be on the throne in the 1680s, when England was divvying up the former New Netherland.

But the origin of the name for New York City’s northernmost borough, the Bronx? That’s a longer story of an immigrant and his prosperous farm in the wilderness of the New World.

It all starts in 17th century Europe with a man named Jonas Bronck. The consensus seems to be that Bronck was Danish, though some historians believe he was from Sweden. Others contend he was from a Dutch Mennonite family driven to Denmark by religious persecution.

A 1639 map of New Netherlands, the year Jonas Bronck arrived

A 1639 map of New Netherlands, the year Jonas Bronck arrivedWhatever his native country was, Bronck made his way to Holland. With his wife and a group of other immigrants, he boarded a ship to New Amsterdam in 1639. “The ship also carried implements and cattle for commencing a plantation on a large scale,” states the 1916 text Scandinavian Immigrants in New York, 1630-1674.

Upon arrival, Bronck purchased 500 acres from local Native Americans (or from Dutch leaders; sources differ) in today’s Morrisania or Mott Haven neighborhood, on the other side of the Harlem River. He cleared the land and built a stone house “covered with tiles,” a barn, several tobacco houses, and barracks for his servants, per Scandinavian Immigrants in New York.

The view from Broncksland a century after Jonas Bronck’s death

The view from Broncksland a century after Jonas Bronck’s death“The purchase price was two guns, two kettles, two adzes [a tool similar to an axe], two shirts, a barrel of cider, and six coins,” states a New Yorker piece from 1939. “His house stood where the N.Y. Central 138th St. station is now, just north of Harlem River.”

In sparsely settled New Netherland, Bronck grew tobacco, wheat, and corn. He also raised cattle and hogs, in “numbers unknown running in the woods,” according to a 1903 edition of the Journal of the New York Botanical Garden.

In 1908, John Ward Dunsmore portrayed the signing of the peace treaty at Bronck’s house

In 1908, John Ward Dunsmore portrayed the signing of the peace treaty at Bronck’s houseHis farm must have been a success. The Broncks furnished their house with fine bed linens, table cloths, alabaster plates, silverware, and a library of religious and historical books in both Danish and German. It was inside this finely furnished house in 1642 where a peace treaty was signed between Native Americans and Dutch colonists (which didn’t last very long, needless to say).

Bronck’s time in his namesake borough was short. He died in 1643, and his wife quickly remarried and moved upstate. Despite his demise, the land where he built his farm was already known as Bronck’s Land, and the river north of his property was referred to as the Broncks’ River.

The South Bronx in the 19th century, with the High Bridge in the distance

The South Bronx in the 19th century, with the High Bridge in the distanceEventually, the entire borough—annexed into the city of New York in stages in the 19th century—became the Bronx at the . What’s with “the” in the borough’s name? “The” is a simply a holdover from when Broncks meant the river.

[Top image: MCNY, F2011.33.687; second image: Library of Congress via Wikipedia; third image: University of Michigan Library Digital Collections; fourth image: Wikipedia; fifth image: NYPL]

The little Hell’s Kitchen synagogue where old Broadway stars once worshipped

When it was founded in 1917 by local Jewish shop owners on West 47th Street in Hell’s Kitchen, the congregation was known as Ezrath Israel.

Actors who frequented the Theater District and Times Square were decided not welcome. In the early 20th century, they were looked down upon for their supposed loose morals and the sometimes shady venues where they plied their trade.

But in the mid-1920s, a new synagogue for this small congregation had been constructed—a beige brick building that stood out thanks to its majestic stained glass center window.

A new rabbi also took the helm, and he “realized that he could increase the membership by welcoming actors from nearby Broadway,” wrote Joseph Berger in the New York Times in 2011. That rabbi, Bernard Birstein, reversed the previous no-performer policy, according to David Dunlop’s 2014 book, From Abyssinian to Zion: A Guide to Manhattan’s Houses of Worship.

Drawing from all the theaters, cabarets, and nightclubs in this hopping part of Jazz Age Manhattan, the congregation attracted showbiz hopefuls as well as the already famous. Performers like Sophie Tucker, Milton Berle, and Jack Benny came to services, and Ezrath Israel became known as the Actors’ Temple.

“Some members and congregants, many of whom were born into poor, hardworking immigrant families, included Al Jolson, Edward G. Robinson, Jack Benny, Milton Berle, Henny Youngman, Eddie Cantor, Burt Lahr, George Jessel, and countless other lesser-known actors, comedians, singers, playwrights, composers, musicians, writers, dancers and theatrical agents, along with sports figures like Sandy Koufax, Barney Ross, and Jake Pitler,” states the temple’s website.

Rabbi Bernard Birstein, center

Rabbi Bernard Birstein, centerTwo of the Three Stooges were congregation members (Mo and Curly Howard, to be precise), and “Academy Award–winner Shelley Winters kept the High Holy Days in our sanctuary,” the website says.

One of the highlights of the congregation was an annual benefit to raise funds for the synagogue’s upkeep. On December 9, 1945, the Brooklyn Eagle wrote about the “stars of stage, screen, and radio” who were scheduled to perform, including Danny Kaye, Jack Durant, and Joe E. Louis.

By the time of his death in 1959, Rabbi Birstein had boosted membership to 1,000, according to a 2002 New York Daily News article. But the number of congregants began to dwindle steadily through the decade—a trend experienced by other small synagogues in Manhattan’s unglamorous business districts, like the Garment District Synagogue and the Millinery Center Synagogue.

Today, the Actors’ Temple is still holding fundraisers and offers services for the high holidays. I’m not sure if any A-listers belong to the congregation, but members “take great pride in carrying on our Jewish show business tradition by being a place of acceptance, spirituality, creativity, and love,” per the website.

[Third image: geni.com]

September 19, 2022

The Feast of San Gennaro festival, painted by a Little Italy artist

Born in 1914 in the Bronx and raised in Greenwich Village’s Little Italy, Ralph Fasanella became a union organizer, a gas station owner, and a self-taught painter of colorful, carnival-like panoramas depicting New York City at work and at play.

“San Gennaro,” is his 1976 take on the annual festival held every September on Mulberry Street since 1926. (The festival is going on in New York right now, through September 26.)

Fasanella’s work is a folk art-inspired, social realist vision of the crowds, vendors, food, games, and patron saint of Naples himself in the center of the canvas, surrounded by Little Italy’s tenements and the tenement dwellers who inhabit them. It’s also currently up for auction; 1stdibs has the info.

[Image: 1stdibs.com]

The roses in the window guards outside an East 51st Street townhouse

Sometimes you come across a New York row house with enchanting, floral-inspired window guards and railings, like the Art Nouveau iron grilles outside this Riverside Drive townhouse.

There’s also the iron blooms on the balconies of the Chelsea Hotel, and the tangle of vines that make up the iron railings outside the front windows of J.P. Morgan’s former mansion in Murray Hill.

But equally beautiful are the wrought-iron roses and rose leafs decorating the oval window guards on the ground floor of 331 East 51st Street (above, top)—a five-story elegant townhouse between First and Second Avenues in Turtle Bay.

The second floor window railings also feature iron roses, and so does the fence around the property. It’s all the more lovely to see actual red and yellow roses growing alongside their iron counterparts.

Walking by this turn-of-the-century townhouse and seeing all the roses—real and decorative—makes this passerby wish summer would never end.

September 18, 2022

This empty shell on Delancey Street was once a movie palace

It’s a forbidding warehouse of a building, with its ground floor carved up decades ago into unattractive (and since the pandemic, often empty) commercial outlets.

But a closer look at this mystery space on the corner of Delancey and Suffolk Streets offers clues about what it used to be in its glory days: the few strangely spaced windows (now filled with concrete), the Art Deco-style ribbon of ornamentation near the roofline that hints at something imaginative and exciting.

The grim fortress at 140-146 Delancey Street is the remains of Loew’s Delancey Street Theater—a vaudeville theater and then movie house opened in 1912 that was “a cornerstone of life on New York’s Lower East Side,” according to Cinema Treasures, a website that tracks defunct theaters across the U.S.

The Loew’s Delancey in 1936

The Loew’s Delancey in 1936The Loew’s Delancey, with about 1,700 seats, occupied the block with another legendary business: Ratner’s Dairy Restaurant, per Cinema Treasures. It was one of over 40 Loews theaters in the New York area at the time, states the 2007 book Jews and American Popular Culture.

In its earliest days, the theater reportedly booked vaudeville acts and showed short films between them; a 1929 Brooklyn Eagle article notes an act that took first prize on amateur night. But by the 1930s, the Delancey was exclusively a movie house, as images of the the old-school marquee attests (My American Wife!).

Another view of that magical sign and marquee, 1939-1941

Another view of that magical sign and marquee, 1939-1941The end of the Delancey echos the end of so many popular, thriving businesses on the Lower East Side after the first half of the 20th century—with a mass exodus of people to the suburbs following World War II, then the decline of the surrounding neighborhood, explains Cinema Treasures.

By 1977, the theater was closed. Though a sign on the facade says that “corner stores and upper floors” are available for rent, the space remains empty—the interior likely gutted of any old movie house magic.

The end of the Delancey, 1978

The end of the Delancey, 1978A new theater has opened across Delancey called the Regal Essex Crossing. Too bad it lacks the enchantment of the former Delancey, with its three-story vertical sign and blazing marquee inviting the public inside to watch a “picture,” as they called it, that you could only see on the big screen.

[Second image: NYPL; third image: NYC Department of Records & Information Services; Edmund Vincent Gillon/MCNY, 2013.3.2.2183]

September 17, 2022

Check out these upcoming talks and tours with Ephemeral New York!

I’m pleased to let everyone know about upcoming tours and a program I’ll be leading this fall. All are open to the public and offer a portal to some of the most dynamic eras in New York City history. It would be wonderful to meet Ephemeral readers at these events!

First, new dates for Ephemeral New York’s popular Riverside Drive walking tour, “Exploring the Gilded Age Mansion and Memorials of Riverside Drive,” are on the calendar in September and early October. The tour starts at 83rd Street and ends at 108th Street.

In between, we’ll stroll the gentle curves of the avenue and delve into the history of this beautiful drive born in the Gilded Age, which became a second mansion row and rivaled Fifth Avenue as the city’s millionaire colony. We’ll look at the mansions that remain, the families and characters who lived there, and the stories told by spectacular monuments.

Tours run from 1 pm to 3 pm and are in conjunction with the New York Adventure Club. Here’s the schedule so far:

Sunday, September 18

Sunday, September 25

Saturday, October 8

On November 9 at 6 pm, I’ll be presenting a Zoom program: “Home Sweet Mansion: A Peek into the Domestic Lives of Gilded Age New Yorkers,” in conjunction with West Side preservation organization Landmark West. Using newspapers, photos, and guidebooks of the era, the program will explore how the upper classes navigated the domestic side of life, why “the servant girl question” was such a vexing topic of the age, and how a staff of maids, coachmen, and other servants managed the households inside the sumptuous mansions and brownstones of the Upper West Side and other areas of Manhattan.

Tickets for this program are not yet available, but I’ll provide a sign-up link and more details when it’s live!

[Top image: New York Adventure Club; second image: NYPL; third image: MCNY, 204627]

September 15, 2022

The colorful mystery mosaics on a Lenox Hill block

Sometimes the most ordinary buildings hold charming surprises. Take 239 East 73rd Street, for example.

It’s a well-kept but unremarkable tenement-style walkup, similar to so many that line the low-rise pockets of the Upper East Side’s Lenox Hill neighborhood.

But someone over the years with a playful sensibility decided to liven up the nondescript facade with a couple of colorful mosaics: one of an owl, the other of a rooster.

A yearning for country life? A whimsical representation of daytime and night? Perhaps the reason for the mosaics is lost to the ages. But they remain on the streetscape, delighting sharp-eyed passersby.

The ghost of a colonial road on the eastern side of the Chrysler Building

There’s no finer example of a New York City Art Deco skyscraper than the Chrysler Building, which gleams with strength and grace 77 stories over 42nd Street and Lexington Avenue.

The Chrysler Building in 1931, rising above 42nd Street

The Chrysler Building in 1931, rising above 42nd StreetThis icon of Machine Age Manhattan was completed in record time between 1928 and 1930, in a race with 40 Wall Street to claim the title of New York’s tallest building. (The Empire State Building beat them both when it debuted on the skyline in 1931.)

Designed by William Van Alen for Walter Chrysler, the head of the car manufacturer, the building begins with a base and then features elegant setbacks as the slender tower rises higher and higher, finally coming to a crown and then a point, literally, with a stainless-steel needle spire that pierces the clouds.

The architectural loveliness of its exterior and interior deserve their own lengthy posts. This post is about how a slant along the Chrysler Building’s setback reflects the former presence of a primitive road traversed by colonial-era New Yorkers.

Gerald R. Wolfe points out this setback in his deeply researched book of walking tours, New York: A Guide to the Metropolis. “Around the corner on 42nd Street (best viewed from the south side of the street), it will be noted that the east wall of the Chrysler Building’s lower setback is not parallel to the north-south avenues,” wrote Wolfe.

This 1822 map shows 42nd Street and Eastern Post (Boston Post) Road as the road crosses Lexington and Third Avenues

This 1822 map shows 42nd Street and Eastern Post (Boston Post) Road as the road crosses Lexington and Third AvenuesTake a look when you’re in the neighborhood: you can see that this eastern setback was built on a rightward slant, while the other setback walls are straight.

What’s the explanation? It’s the ghost of Boston Post Road, a long-defunct thoroughfare and one of the city’s few reliable roadways in the 17th and early 18th centuries. (Boston Post Road was also called Eastern Post Road, or East Post Road—it was the thoroughfare to take if you were heading out of the city to New England.)

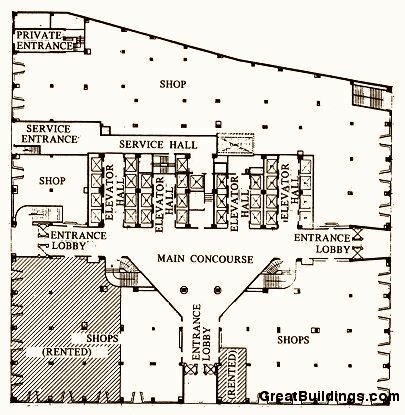

Plans for the trapezoid-shaped Chrysler Building

Plans for the trapezoid-shaped Chrysler BuildingThe plot of land on which Walter Chrysler planned to build his tower once bordered Boston Post Road, which predated the city street grid and ran roughly between today’s Third and Lexington Avenues, Wolfe explained. When he acquired it, the original border remained—even though the road was defunct.

With this meandering colonial road forming the parcel’s eastern boundary, Chrysler ended up with a slanted plot shaped like a trapezoid, as Sam Roberts put it in his 2019 book, A History of New York in 27 Buildings. Hence the angled setback, which reflects the angle of this de-mapped road.

Boston Post Road disappeared from city maps in the 19th century, though it’s unclear when. It was definitely gone by the Gilded Age: A New York Times article from 1881 describes it as “now obliterated and forgotten.”

Other ghosts of the Boston Post Road still exist though. One remnant is this East 49th Street courtyard, where travelers could catch the stagecoach to Boston.

In 1929, ready to wow the world

In 1929, ready to wow the world[Top photo: NYPL; third image: Map of the Common Lands; raremaps.com; fourth image: greatbuildings.com; fifth image: NYPL]