Esther Crain's Blog, page 41

October 15, 2022

Take a Walk up Riverside Drive with Ephemeral New York This Sunday!

On Sunday October 16, I’ll be leading another relaxing and insightful walking tour that explores the Gilded Age mansions and monuments of Riverside Drive—and there’s still room for more guests.

We’ll begin at 1 p.m. on Riverside and 83rd Street, dip into Riverside Park, and then stroll up to 108th Street. In between, we’ll delve into the history of this beautiful avenue born in the Gilded Age, when the Drive became a second “mansion row” and rivaled Fifth Avenue as the city’s “millionaire colony.”

The tour explores the mansions and monuments that survive, as well as the incredible houses lost to the wrecking ball. We’ll take a look at the wide variety of people who made Riverside Drive their home, from wealthy industrialists and rich business barons to actresses, artists, and writers.

Though we cover a lot of territory, the tour goes at a breezy, conversational pace. Fall is the best time to walk New York’s streets and neighborhoods. All are welcome! Tickets are available here via the New York Adventure Club.

[Top image: MCNY, 26908.1F; second image: MCNY, F2011.33.73; third image: NY Adventure Club]

October 10, 2022

Boot scrapers are a hidden relic of 19th century New York City

Late season hurricanes, mean nor’easters, and regular rainy days: all this wet weather makes autumn boot-scraper season in New York City.

If you routinely look down when you walk though New York City, then you’ve seen boot scrapers. These charming remnants of a dirtier Gotham can often be found on the iron railings of brownstone stoops. Before entering his own or someone else’s home, a gentleman would scrape his boots against the blunt end, so he wouldn’t track mud and dirt into the house.

It wasn’t just wet weather that necessitated boot scrapers. Think of what Gotham’s streets looked like before asphalt paving and automobiles: dirt and mud on the streets and sidewalks, debris from toppled ash barrels, and piles of horse manure from the thousands of equines who pulled wagons, carriages, and streetcars.

Some boot scrapers are quite fancy, like these on West 67th Street outside a former home for Swiss immigrants and these outside a school in Yorkville. I spotted this fairly utilitarian boot scraper between Fifth and Sixth Avenue in Greenwich Village. In such a posh and lovely neighborhood in the 19th century city, I’m sure it got lots of use!

October 9, 2022

The Art Deco-style Chelsea mosaics that illustrate the needle trades

Contemporary New Yorkers don’t often hear the term “needle trades” anymore. But in the vernacular of the early 20th century, it referred to any work related to the creation of clothing—like sewing, pattern making, cloth cutting, and dressmaking.

Much of this work in the decades before World War II was done by immigrants and first generation New Yorkers in Manhattan’s Garment District, the stretch of showrooms, wholesale shops, and factories inside the towering new loft buildings built between Broadway and Ninth Avenue and 34th to 42nd Streets.

Before moving to this chunk of Midtown, the needle trades were centered in sweatshops on the Lower East Side and Greenwich Village, and the work was also done piecemeal at home with little regulation or protection. A somewhat regulated Garment District was considered an improvement in progressive Gotham.

To train and supply prewar New York’s army of garment manufacturers, the city—with the help of the WPA—built an Art Deco-style vocational high school called Central High School of Needle Trades (top photo). Opened in 1940 on West 24th Street between 7th and 8th Avenues, it was developed in conjunction with garment industry reps.

“This building has sixty-five shops and special rooms, ten regular classrooms and six laboratories in which will be taught all branches of tailoring, costume design, millinery design, dressmaking, shoe manufacturing, fur processing and allied subjects,” the New York Times wrote when the school opened, per The Living New Deal.

Since 1956, the school has been known as the High School of Fashion Industries. With the decline of manufacturing in what’s still called the Garment District, there’s much more of a focus on the business of fashion, per the school website.

Even so, students continue to attend class in the original Art Deco Needle Trades building. Outside the entrance are four proud mosaics illustrating different aspects of the needle trades—from sewing to measuring to threading a needle.

The work may seem primitive amid our digital age, but the mosaics are a reminder of all that used to be made in New York primarily by human hands.

The West Side school perched on top of a massive rock pile

Not many cities have a type of rock named after them, but Manhattan has Manhattan schist—an ancient bedrock formed roughly 450 million years ago.

Manhattan schist generally lies underground, providing the ideal strong foundation for the skyscrapers clustered in Lower Manhattan and Midtown, where the schist is closer to ground level and better able to anchor massive buildings.

But some schist lies above ground in the form of giant amazing rock outcroppings. Case in point: this high pile of gray, grainy schist on West 123rd Street east of Amsterdam Avenue in Morningside Heights.

Even in New York City, which from its very beginnings flattened and filled in the natural topography to fulfill real estate needs and dreams, schist like this was tough to deal with. For most of the 19th century, the pile was the site of blockhouse number 4–one of several small stone forts built to hold munitions if needed to defend Gotham during the War of 1812, per Harlem + Bespoke.

By the end of the 19th century, the schist and the unused blockhouse were part of Morningside Park. This steep, schist-filled green space became a park in part because Parks commissioner Andrew Haswell Green thought it would be “very expensive” and “very inconvenient” to extend the Manhattan street grid to such a rocky area, according to NYC Parks.

123rd Street looking east from Amsterdam: the remains of the 1812 Blockhouse are on top of the rocks

123rd Street looking east from Amsterdam: the remains of the 1812 Blockhouse are on top of the rocks In the 1960s, however, the city was casting about for a site to build a new elementary school in or around Harlem. “The state legislature and mayor supported the construction of a school on the north part of Morningside Park, where the ruins of Blockhouse 4 were,” states the website for the Margaret Douglas School, also known as PS 36.

Construction of the school began in 1965, the ruins of the blockhouse were bulldozed away, and a new elementary school rose on this prehistoric heap of Manhattan schist.

The school is still in use, a Brutalist-style building stacked on top of the massive rocks with the help of concrete risers. It’s not far from another Manhattan schist outcropping: the enormous rat rock on West 114th Street, which was apparently too expensive to dynamite away and remains wedged between two apartment buildings.

[Third image: MCNY, F2011.22.1574]

October 3, 2022

Once an 1880s public library, now a private home in the West Village

When you pass the three-story red-brick beauty at 251 West 13th Street—with its elegant arched windows and Dutch-style gabled roofline—you just know it was built for something special.

That special purpose was a noble one in Gilded Age New York. The building, near Eighth Avenue and at the end of Greenwich Avenue, served as a free public library—one of the city’s first.

The story of what became known as the Jackson Square Library began in 1879, when a teacher and other women affiliated with Grace Church formed the New York Free Circulating Library.

New York City was already home to many fine research libraries, such as the Astor Library (now the Public Theater) on Lafayette Place. But in 1879, these libraries were largely private and didn’t lend books.

“The New York Free Circulating Library was established to serve every New Yorker, especially the poor, and to allow them to not only read a wide range of literature, but bring it home and share it with their families,” states Village Preservation.

The library in an undated photo

The library in an undated photoThe original library room founded by the Grace Church group held just 500 books and was only open two hours a week. But according to Village Preservation, “the free public reading room was so popular there were often lines around the block.”

This is where a member of the Vanderbilt family comes in. George Washington Vanderbilt II, a grandson of Commodore Vanderbilt and brother of the socially prominent W.K. Vanderbilt and Cornelius Vanderbilt II, decided to continue his family’s tradition of philanthropy by building and stocking a free circulating library for the people of New York City.

Another undated photo, but note the remodeling of the neighboring house’s front door

Another undated photo, but note the remodeling of the neighboring house’s front door“The youngest of eight children, [George Vanderbilt] was a quiet person with a strong interest in culture and the life of the mind, who had created and catalogued his own collection of books beginning at age 12,” states Village Preservation. “The growing desire for a free circulating library in New York was just the sort of worthy project that captured the bibliophile’s imagination.”

Vanderbilt tapped architect Richard Morris Hunt (who also designed Vanderbilt’s breathtaking North Carolina estate, Biltmore). In 1888, the Jackson Square Library, with more than 6,000 books, opened to readers.

The Adult Reading Room in the 1930s

The Adult Reading Room in the 1930s“The walls of the library on the ground floor are tinted a robin’s egg blue, while the book shelves and other woodwork are of walnut, which sets off the bright bindings of the books,” wrote The New York Times in a preview the library’s interior. A second-floor reading room was described as “light and airy.” To become a member of the library, applicants had to be at least “twelve years of age and able to give proper reference.”

After the New York Public Library system formed in 1895, the Jackson Square Library continued to operate as a NYPL branch. By the early 1960s, the library was “decommissioned,” per Village Preservation. The Jefferson Market Library on Sixth Avenue and 11th Street took over as the NYPL branch for Greenwich Village in the 1970s.

George Washington Vanderbilt II by John Singer Sargent, with book in hand

George Washington Vanderbilt II by John Singer Sargent, with book in handIt’s hard to fathom, but after it closed, the Jackson Square Library was headed for the wrecking ball. In 1967, painter, sculptor, and performance artist Robert Delford Brown acquired it for $125,000, according to a New York Times story in 2000. That saved the former library, which had hosted notable patrons like James Baldwin, Gregory Corso, and W.H. Auden, among others.

Brown gave the building a “radical renovation,” according to the Times, and the results weren’t necessarily successful. The former library was purchased in the 1990s by TV writer and producer Tom Fontana. Intending to use it as a residence and work space, Fontana brought 251 West 13th Street back to its Gilded Age grandeur, at least on the exterior—making it a delightful sight for passersby.

[Third, fourth, and fifth photos: NYPL; sixth photo: Wikipedia, by John Singer Sargent]

Who carved a horse above the entrance to this East Side brownstone?

East 116th Street between Second and Third Avenues has a long history as a bustling shopping strip—first as a crosstown street between the Second and Third Avenue Els in the heart of Harlem’s Little Italy, and since the 1940s and 1950s as a main thoroughfare for predominantly Hispanic East Harlem.

235 East 116th Street

235 East 116th StreetThe brownstone-fronted houses on the north side of the street form a handsome, stately row. Built in 1890 as Italian laborers began moving into an area already colonized by German, Irish, and Jewish residents, you can imagine that these homes were owned by more middle-class folks in what was otherwise a working-class and poor neighborhood.

But on Number 235, which borders a historic church, something curious is carved above the entrance. It’s the image of a horse, in motion with no saddle, framed by a rectangular space set inside an oval.

Underneath the horse are what look like Greek letters. Google tells me this translates into, well, “horse.”

Number 235, in 1929, is to the right of the church; see the oval above the door

Number 235, in 1929, is to the right of the church; see the oval above the doorI’ve found myself passing by this horse a few times in recent months, and it’s an unusual relic, something I’ve never seen on any other brownstone entrances. Based on the black and white images of the house below, it seems that the horse has been here since at least 1929.

Stables and carriage houses in pre-automobile New York City often had an ornamental horse head or horse image outside the building, but this brownstone doesn’t appear to have ever been used as a boarding space for horses.

From 1939-1941

From 1939-1941Could someone involved in the carriage industry have lived here? Newspaper archives indicate the brownstone was home to Charles Schneider in 1907, profession unknown. In the 1910s and 1920s it was occupied by Salvatore A. Cotillo and his family. Cotillo was a Fordham-educated lawyer who immigrated from Naples as a boy and later became a state senator and then a city judge. Other owners and occupants haven’t been identified.

The horse could be a symbol of sorts, harkening back to ancient Greek or Roman mythology. Or maybe a resident created it on a whim? It’s here to stay, and I’d love to know the origins.

[Third image: NYPL; fourth image: New York City Department of Records & Information Services]

October 2, 2022

The mysterious woman on the “little penthouse” of a 1930s tenement roof

Martin Lewis had a thing for New York City rooftops. They made excellent vantage points for this Australia-born artist’s drypoint prints, allowing him to depict nuanced moments on the streets of the 1920s and 1930s city: kids at play under the glow of shop lights, young women on the town illuminated by street lamps, and New Yorkers going about their lives unaware that someone is watching.

But Lewis also looked to roofs as if they were theater stages, capturing the cryptic scenes that played out on them. Case in point is the mysterious woman in a print he titled “Little Penthouse,” from 1931.

The little penthouse appears to be the stubby rooftop structure many tenements had that led to an interior staircase. The penthouse as a place of luxury was a new concept in the 1920s, but this rooftop is anything but luxurious.

The woman stands before it, stylishly but plainly dressed. Layers of the wider city are all around her: the brick fortress-like wall of a neighboring building , another row of low-rise dwellings, taller modern structures, even a skyscraper with a pinnacle or antenna illuminating the night sky.

The layers lend the scene great depth, and combined with the shades and tones of the print emphasize her aloneness. She’s the only person in the image, elevated on a rooftop but perhaps not elevated according to the society she lived in—she’s on a tenement roof in the dark, after all.

She seems to be hesitating to go inside and down the stairs into the building. Is she actually alone, or is she addressing another person out of view? Does the little penthouse lead to safety, or is she in danger? She could be a maid, perhaps, ending her day by bringing something to the roof for her employers.

Like so many of Lewis’ masterful scenes of Gotham’s dark corners and shadows, he leaves us with more questions than answers.

September 30, 2022

The spooky spider web windows on 57th Street

The scary season is upon us, and Halloween-loving New York City residents are decorating their front stoops, windows, and terraces with witches, skeletons, and spider webs. But one East Side apartment building flaunts cast-iron spider webs across its front windows all year long.

The spider web windows are at 340 East 57th Street, a 16-story vision of prewar elegance between First and Second Avenues. Look closely at the service door above: this web has a black spider sitting in it, waiting and watching. It looks particularly Halloween-like with the orangey glow from the inside light.

The building’s architect, Rosario Candela, was one of the legendary designers of Manhattan’s most exclusive residences in the 1920s. I’ve posted about this building before, and I still don’t know if he had a hand in creating those spider web window guards.

If so, I appreciate Candela’s sense of spooky playfulness. Also playful but not quite spooky: the whimsical seahorse reliefs below the second-story windows.

This decaying building was Central Harlem’s first apartment house

Apartment living was still a strange new concept to New Yorkers in the Gilded Age. But that didn’t stop developers from turning Seventh Avenue between West 55th Street and Central Park South into Gotham’s first luxury apartment house district.

Opening their doors to elite tenants between 1879 and 1885 were spectacular residences like the Van Corlear, the Wyoming, the Navarro Flats, the Ontiora, and the Osborne. (Only the latter two are still standing, unfortunately.)

The Washington Apartments

The Washington ApartmentsA few miles north, Seventh Avenue (now known as Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard) in Central Harlem was also transforming into an apartment house district in the 1880s. Rather than hoping to lure very wealthy residents, developers in Harlem were aiming for a more middle- to upper-middle class clientele.

“Between the 1870s and 1910 Harlem was the site of a massive wave of speculative development which resulted in the construction of record numbers of new single-family row houses, tenements, and luxury apartment houses,” states a Landmarks Preservation Commission report from 1993.

From 122nd Street

From 122nd StreetMuch of this new housing was intended for the emerging class of professionals who desired quality homes within easy commuting distance of the city’s main business and shopping districts. With three elevated train lines extending to 129th Street, and electricity and phone service set to arrive by the end of the decade, Harlem was moving from a sparsely populated enclave to a fully urbanized part of the metropolis.

One financier who profited from this speculative development in Harlem was Edward H.W. Just. Born in Germany, Just came to New York in the 1830s and co-founded the Just Brothers Fine Shirt manufacturing company. By the 1880s and 1890s, the company had stores on Ladies’ Mile—the Gilded Age city’s premier shopping district from Broadway to Sixth Avenue between 10th and 23rd Streets.

The Washington Apartments are on the right, recognizable thanks to its pediment

The Washington Apartments are on the right, recognizable thanks to its pedimentJust began investing in real estate in Harlem, purchasing land on the northwest corner of Seventh Avenue and 122nd Street. He hired Mortimer C. Merritt—an independent architect who designed Hugh O’Neill’s Sixth Avenue department store, with its signature beehive domes—to draw plans for an apartment house.

“Edward Just was concerned about providing solid middle-class housing in Harlem and was an advocate of the large apartment house, a building type which in 1883 had only recently begun to gain popularity and enough cache to be acceptable to New York’s middle class,” states the LPC report.

Washington Apartments, 1940

Washington Apartments, 1940Construction commenced in 1883, and one year later the building was completed. A harmonious, eight-story Queen Anne creation of red and light brick, stone, and terra cotta as stunning as any Midtown apartment house, the Washington Apartments was the first apartment residence in Central Harlem.

Thirty families made the new building, with its signature triangular pediment, their home. “The occupants included doctors, lawyers, bankers, public accountants, and builders, many of whom had servants who lived with them,” per the LPC Report. “A number of residents had offices in lower Manhattan and were able to live in Harlem and conveniently commute to work because of the recently constructed elevated railroad.”

The LPC doesn’t specify the ethnic backgrounds of these middle-class residents, but one can assume these were white New Yorkers. Central Harlem’s transition into a predominantly African American district didn’t begin until the early 1900s.

“The real estate bubble burst in 1904-1905 when people realized that no one was sure when the subway line would be completed, and that too many apartment buildings had been created, and there was not enough demand—and even if there was demand the rents were too high for most people to afford,” states CUNY’s Macauley Honors College. “Thus to avoid losing the investment, some landlords allowed blacks to move into the neighborhoods and pay high rents, as was the norm for black tenants in the city.”

The ethnic makeup of the residents of the Washington Apartments, however, remained the same until the 1920s. “With all the changes occurring nearby, the Washington Apartments maintained its white, middle-class residents through the 1920s,” per the LPC report. “Interior changes made from 1915 through 1920 did, however, create smaller apartments so that the building, which had been constructed to house 30 families in 1883, was home to 63 families and a restaurant in 1932.”

Over the next decades, ownership of the Washington Apartments changed hands several times, allowing the building to fall into disrepair. In 1977, the city of New York purchased the almost 100-year-old dowager. “Rehabilitation began in the late 1980s,” the LPC report says.

No longer owned by the city these days, the Washington Apartments desperately need another rehabilitation. CBS News aired a report in early September on the building’s broken locks, nonworking security cameras, vandalism, and elevator problems, among other troubling issues. The residents of this early apartment house, which influenced the development and feel of Central Harlem and was landmarked by the city in 1993, deserve better.

[Third image: MCNY, F2011.33.1577; fourth image: NYPL Digital Collections]

September 26, 2022

The short life of the multi-family Tiffany mansion on Madison Avenue

In 1882, Charles Lewis Tiffany decided to build an enormous new residence for himself and his family.

The early years of the mansion, almost alone in the wilds of the Upper East Side

The early years of the mansion, almost alone in the wilds of the Upper East SideThis wouldn’t be unusual for a rich, prominent merchant in Gilded Age New York City. Tiffany was that Tiffany, the man who launched a stationary and fine goods shop in 1837 that soon grew to become the internationally famous jewelry store.

What might have seemed odd was the location Tiffany chose for his family castle. Rather than gravitating toward Fifth Avenue just below Central Park, where other elite new money New Yorkers were building elegant homes, Tiffany planned his mansion on Madison Avenue and 72nd Street—a mostly empty stretch of Manhattan that had yet to fulfill its destiny as a wealthy residential enclave.

The Tiffany mansion between 1900-1910, with more neighbors on Madison Avenue

The Tiffany mansion between 1900-1910, with more neighbors on Madison AvenuePerhaps he had an affinity for Madison Avenue; Tiffany lived at 255 Madison near 38th Street at the time. Or it may have been an opportunity to “procure a large footprint of land on a wide cross street, ensuring not only extra light but also ample southern exposure,” wrote Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen in Louis Comfort Tiffany and Laurelton Hall.

Tiffany hired McKim, Mead & White to design what would be one of the largest dwelling houses in New York, even by Gilded Age standards. Working closely with Stanford White in particular was Charles Tiffany’s son, Louis Comfort Tiffany. Louis had studied painting before becoming an innovative and acclaimed decorative artist-craftsman and starting Tiffany Studios, “renowned for pottery, jewelry, metalwork and, especially, stained glass,” wrote Christopher Gray in a 2006 New York Times piece.

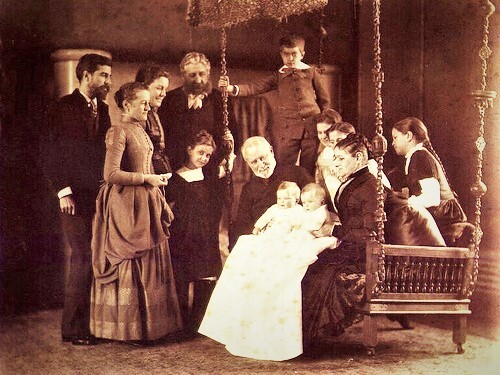

Louis Comfort Tiffany, far left; Charles Tiffany is in the center holding Louis’ kids in 1888

Louis Comfort Tiffany, far left; Charles Tiffany is in the center holding Louis’ kids in 1888The mansion, completed in 1885, was a 57-room showstopper that dwarfed its few neighbors. There was another unusual aspect to it: the gigantic house was actually three separate residences for separate Tiffany family members.

“The first, on the first and second floors, was frequently said to be for Charles, but he never occupied it,” wrote Gray. “The second apartment, taking up the third floor, was for Louis’s unmarried sister, Louise; the third, on the fourth and fifth floors, was for Louis himself.”

Louis’ first wife died before the mansion was finished, and the widower moved in with his four young children from their previous residence on 26th Street. (He would soon remarry and have four more kids.) Louise stayed with her parents at 255 Madison, according to Michael Henry Adams, writing in HuffPo.

To enter the house meant walking through a huge stone arch, which led to a central courtyard. “The structure was crowned by a great tile roof—substantial enough to have covered a suburban railroad station—and by a complex assemblage of turrets, balconies, chimney stacks, oriel windows and other elements in rough-faced bluestone and mottled yellow iron-spot brick,” noted Gray.

Of course, a mansion of this size and pedigree attracted the attention of architectural critics, who either loved it or hated it. Ladies’ Home Journal dubbed it “the most artistic house in New York City,” thanks in part to detail on the facade and ornament, wrote Frelinghuysen. A detractor called it “the most conspicuous dwelling house in the city,” she added.

Louis reserved the fifth floor for his studio, which was three to four stories high and situated amid the mansion’s gables, according to Gray. Accounts from visitors suggested that the studio was a showcase for Louis’ talent and creativity, as well as his collections of exotic objects and furnishings. It also served as a “sanctuary from the daily bustle,” wrote Frelinghuysen.

“A forest of ironwork, brasses and decorative glassware suspended from the ceiling made the atmosphere even more obscure and mysterious,” added Gray. “Near the center was a four-hearth fireplace, feeding into one sinuous chimney made of concrete. It rose from the floor like an Art Nouveau tree trunk.” Makes sense; Louis took his inspiration from nature.

An 1886 sketch of the house, dwarfing the two men on the sidewalk

An 1886 sketch of the house, dwarfing the two men on the sidewalkIn 1905, after the elder Tiffany passed away, Louis built a country estate near Oyster Bay, Long Island called Laurelton Hall. As the decades went on, he began spending more time there, moving some of the furnishings and objects from his Madison Avenue to his estate house.

He died in the Madison Avenue mansion in 1933 at the age of 84; the house met the wrecking ball three years later. The spectacular mansion, designed as a family compound of sorts that most of the family never actually lived in, was replaced by a stately apartment building.

[First and second images: NYPL; third image: Wikipedia; fourth image: MCNY 93.1.1.18259; fifth image: Google Arts and Culture; sixth image: NYPL]