Esther Crain's Blog, page 38

January 1, 2023

The story of a Fifth Avenue mansion scorned by its second owner as a “gardener’s cottage”

If houses could talk, I’m betting 1048 Fifth Avenue would tell lots of stories—specifically about the first two of its four total owners over more than a century overlooking 86th Street.

The first owner was a wealthy industrialist who made the most of his good fortune, holding his daughter’s wedding to a British lord in the music room. The other owner was a society doyenne forced to downsize from an 80+ room palace, and she dubbed it a mere cottage compared to the house she was accustomed to.

The story began during the Fifth Avenue mansion-building mania after 1890. For the next 25 years, a rush of business titans and old money millionaires sought to build their castles opposite Central Park.

Mrs. Astor, Andrew Carnegie, William A. Clark—one by one, the Gilded Age wealthy relocated to their new dwellings. At the tail end of this mansion boom came the French Classical–style house at 1048 Fifth Avenue, at the southeast corner of 86th Street.

Taking the place of a previous mansion owned by brewer David Mayer, number 1048 was commissioned by William Starr Miller. An industrialist and real estate operator, Miller had been residing at the more genteel end of Fifth Avenue steps from Washington Square Park.

Exactly what Miller did to make his money is a little unclear. But he had enough of it to hire the premier architectural firm Carrere & Hastings to create his new digs. Carrere & Hastings designed the New York Public Library building at 42nd Street and Fifth Avenue in 1912, and the firm was about to begin work on Henry Clay Frick’s house down the avenue on 70th Street.

Completed in 1914, what became known as the William Starr Miller house cost $150,000. It was more refined and restrained than many of the other mansions going up around it. Red brick and trimmed in limestone, it has a slender front on Fifth Avenue, with the bulk of the structure and the entryway facing East 86th Street.

Were the Millers the type of people who love taking in views? They certainly had the opportunity. The house has enormous second- and third-story windows, plus a fourth-floor mansard slate roof with dormers and small “bullseye” windows, perfect for stargazing.

While they may have enjoyed looking outside, the Millers hosted a headline-making social event inside their mansion in 1921. Daughter Edith Starr Miller, 33 (above), wed a 60-year-old British industrialist named Almeric Hugh Paget, a widower (his first wife was Pauline Payne Whitney) known as Lord Queenborough.

It was a surprise affair in the Miller mansion, covered by all the newspapers. “The bride, who was given away by her father, had no attendants, and there was no best man or usher,” reported the New-York Tribune. The marriage gave the couple three kids, but it fell apart after Lady Queenborough accused her husband of abandoning her.

The Millers resided in the mansion until their deaths—William Starr Miller passed away in 1935 inside his house at age 78. His wife, Edith, died in 1944…which marked the next chapter in the house’s life.

The second owner of number 1048 was a woman of social importance with a famous last name. Grace Vanderbilt (above as a younger woman) had been married to Cornelius “Nelly” Vanderbilt III (great-grandson of the Commodore). The couple’s New York home base was the palatial Vanderbilt mansion at 640 Fifth Avenue, at 51st Street—aka, the Triple Palace. But after her husband’s death in 1942, she had to downsize.

“The gardener’s cottage” was how she referred to her new living quarters. She held dinners and balls there as she had done her entire life (many that raised money for charitable causes). Yet Vanderbilt reportedly described herself as “all alone in the house,” despite the fact that she had 18 servants attending to her.

Health issues plagued her, and she eventually eased up on her society life. As the Millers had, Vanderbilt died in her so-called gardener’s cottage. This last living link to the Gilded Age passed away in 1953 at 82.

The William Starr Miller house changed hands once again in 1955, this time not to a person or family but an organization: YIVO Institute for Jewish Research.

Almost 40 years later, YIVO sold the mansion to cosmetics billionaire Ronald Lauder and art dealer Serge Sabarsky—who transformed this late Gilded Age survivor into the Neue Galerie. Opened in 2001, the Neue contains Lauder’s magnificent collection of early 20th century German and Austrian art.

Number 1048, a remarkable beauty on what used to be called Millionaire’s Mile is now a must-see destination on Museum Mile.

[Fourth image: New-York Herald; fifth image: MCNY, 1915: x2010.7.1.1838; sixth image: Wikipedia; seventh image: MCNY, 1920: 93.1.1.10084]

December 26, 2022

A soft, shimmering Times Square after the post-Christmas blizzard of 1947

The snow began falling during the early morning darkness the day after Christmas. It continued through the afternoon and evening, catching New Yorkers by surprise—the forecast only warned of flurries.

By the time the Great Blizzard of 1947 was over, 26 inches of snow buried the city—killing an estimated 77 people, snarling mass transit, and putting a spotlight on Gotham’s lack of snowplows, according to data from Baruch College.

In a softly glowing Times Square, weary New Yorkers found something to cheer.

“Long after nightfall the illuminated news sign of the New York Times flashed the announcement to little groups of people huddled in Times Square that the snowfall, which totaled an amazing 25.8 inches in less than 24 hours, had beaten the record of the city’s historic Blizzard of 1888,” wrote Life magazine on January 5, 1948.

“A faint, muffled shout of triumph went up from the victims.”

[Al Fenn/The Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock]

The blazing colors and old-school design of two Manhattan store signs

It’s a special thrill to come across a vintage New York City store sign that’s never caught your eye before. The design, the typeface, the colors—it all hits you at once, making you feel like you’ve found a magical spot in Gotham where mom-and-pop shops aren’t the exception and time stands still.

That’s the feeling I had after happening upon these two time machine signs a while back, one on the Lower East Side and the other on the opposite end of Manhattan in East Harlem.

On Essex Street is the signage for fourth generation-run M. Schames & Son Paints. I don’t know how old the sign is, but M. Schames got its start in 1927, according to the company Facebook page. The business appears to have moved to 90 Delancey Street.

The sign for Casa Latina, on East 116th Street, is another portal to the New York of the 1950s or 1960s, when Italian Harlem transformed into Spanish Harlem and salsa music came into its own.

Family owned and operated for over 50 years, the shop sells Latin music, instruments, and collectibles, per their Facebook page. Actually, make that sold. According to nycgo.com, Casa Latina is no longer in business. At least the wonderful sign is still there.

George Washington opens his Cherry Street presidential mansion to New Year’s callers

When George Washington became the first president of the United States in 1789, he relocated to a rented four-story mansion at Cherry and Pearl Streets. There, he established his executive office and family living quarters.

New York City was the new nation’s official capital at the time, and Washington was adjusting to the city’s culture and rituals—worshipping at St. Paul’s Chapel, for example, and regularly taking the air along the Battery.

One Gotham tradition he also took part in was inviting New Year’s Day callers to his presidential mansion (below). Established by the colonial Dutch burghers of New Amsterdam more than a century earlier, the annual ritual of “calling” turned the city into one big open house, where residents hosted a succession of neighbors and friends all day with hospitality and good cheer.

It was the biggest holiday of the year. New Yorkers would spend days readying their parlors for guests, donning their finest outfits, and setting up a big table of alcohol-infused punch, cakes, and confectionaries. Callers would stop by, offer good wishes for the coming year, and then move on to the next house to repeat the ritual with full bellies and in lively spirits.

Though he was the commander-in-chief of the United States, Washington was also a New Yorker—for the time being, at least. (He departed to Philadelphia later that year after the city of brotherly love took a turn as America’s capital.)

So on January 1, 1790, he “was determined to add the power of his name as an example of the observance of this time-honored custom,” according to The Old Merchants of New York City, published in 1885.

“It was a mild, moonlit night of the first of January, 1790, when George Washington and ‘Lady’ Washington stood together in their New York house to receive the visitors who made the first New Year’s calls with which a President of the United States was honored,” recounted the Saturday Evening Post in 1899.

Who were the callers, specifically? Washington described them in his own diary as “The Vice-President, the Governor, the Senators, Members of the House of Representatives in town, foreign public characters, and all the respectable citizens.”

These callers “came between the hours of 12 and 3 o’clock, to pay the compliments of the season to me—and in the afternoon a great number of gentlemen and ladies visited Mrs. Washington on the same occasion.”

“Tea and coffee, and plum and plain cake were served by the mistress of the mansion, while her stately husband, whose fine figure was set off in the costume of the drawing room to even better advantage than in his military garb, greeted his visitors with friendly formality,” continued the Post.

By nine p.m., the Washingtons were ready to retire for the night. According to the Post, he asked his guests “if the custom of New Year visiting in New York had always been kept up there, and he was assured that it had been, from the early days of the Dutch. He paused, and then said pleasantly, but gravely:

“‘The highly favored situation of New York will, in the progress of years, attract numerous immigrants, who will gradually change its customs and manners; but whatever changes take place, never forget the cordial and cheerful observance of the New Year’s Day,'” stated the Post article.

Washington’s words that night were certainly prophetic. Though the tradition of New Year’s calling continued into the 19th century, it gradually began to die out, coming to an end during the Gilded Age. In 1888, the New York Times, lamented “the almost complete death of the ancient custom of call-making” every January 1.

[Top image: “Lady Washington’s Reception Day,” painted by Daniel Huntington, 1861, Wikipedia; second image: Washington’s Cherry Street mansion, Wikipedia; third image: Washington’s 1789 inauguration at Federal Hall on Wall Street; fourth image: plaque put up to mark the former site of Washington’s Cherry Street mansion, LOC; fifth image: Washington in 1790, painted by John Trumbull, Wikipedia]

December 19, 2022

A newspaper magnate builds a soundproof, Venetian-style mansion steps from Fifth Avenue

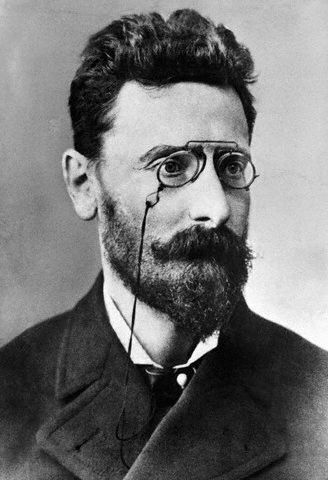

The year 1900 wasn’t a good one for Joseph Pulitzer—the rich and influential owner of the New York World, one of Gilded Age Gotham’s most popular and sensational newspapers.

His elegant mansion at 10 East 55th Street, designed by Stanford White, had been destroyed by a fire earlier that year. Two household servants died in the blaze, according to architectural historian Andrew Alpern, author of Luxury Apartment Houses in Manhattan: an Illustrated History.

His health was in bad shape as well. The 53-year-old Hungarian-American immigrant was almost totally blind, and he had developed a condition that made him so excruciatingly sensitive to sound, even the striking of a match sent him into “spasms of suffering,” per a New York magazine article.

So while he and his family temporarily relocated to the posh Savoy Hotel on Fifth Avenue and 57th Street after the fire, Pulitzer shelled out $240,000 on a plot on East 73rd Street measuring 98 feet wide—about three times the size of the land on which his 55th Street mansion stood.

He then asked Stanford White to design a spectacular residence, one that would be soundproof in addition to being fireproof.

For Pulitzer’s new mansion, White looked to Italy for inspiration, basing his design on the Palazzo Pesaro and Palazzo Rezzonico, both built in Venice in the 17th century.

“The limestone-clad, 4-story structure has a rusticated base with a step-up entrance with a pair of rusticated columns that leads to a step-up lobby that opens onto a very large and impressive entrance hall with a quite grand staircase,” stated nycago.org.

Unlike more typical Gilded Age mansions, which tended to be decorated with lots of terra cotta ornamentation and other Beaux Arts bells and whistles, the facade of Pulitzer’s new palace is relatively plain—likely a nod to Pulitzer’s lack of sight.

“While the design of the outside of the house had been developed in a way that took Pulitzer’s blindness into account, the interior made no such concessions,” wrote Alpern.

“Completed in 1903, it was the sort of lavishly grand pastiche of period styles that had made Stanford White the architect and interior designer most sought out by the socially secure and the arrivistes alike. It was a visual feast that Pulitzer could hear described to him but could not enjoy himself.”

White took steps to address Pulitzer’s sensitivity to noise. Said Alpern: “Especially sound-resistant construction was specified, and a secondary glazed partition was erected to acoustically block the windows that overlooked the street.”

Unfortunately, Pulitzer was still tortured by sounds. So in 1904, a one-story extension of the house was created at the end of a small side garden, stated Alpern. Construction “was set as far from the street as possible, and was built with massive walls and only one small window.” Even so, Pulitzer’s noise sensitivity continued.

For all the effort that went into constructing and perfecting his Venetian-style mansion, Pulitzer ended up living there for only another eight years. This accomplished publisher—who bequeathed the funds to start Columbia University’s journalism school, established the Pulitzer prizes, and led a campaign in the World to help finance the Statue of Liberty—passed away in 1911.

After his death, Pulitzer’s family moved out of the mansion, according to nycago.org, and it stood vacate for years because a buyer could not be found. Grand stand-alone residences like Pulitzer’s were going out of style, and apartment living was preferred by wealthy residents, In 1930, investors planned to knock it down and put up an apartment house.

The Depression put an end to that, and in the 1950s, another plan to bulldoze the mansion and replace it with an apartment building also fell through. Somehow, Pulitzer’s palazzo managed to escape the wrecking ball a second time.

This beautiful and unique dwelling house has since become a co-op with 16 apartments carved out of the original mansion. Occasionally an apartment will come up for sale, like this one on the ground floor—which the listing says includes Pulitzer’s post-construction bedroom.

[Third image: New-York Historical Society; seventh image: Wikipedia]

December 18, 2022

Two married artists, two similar views looking outside their East Side hotel window

When Alfred Stieglitz met Georgia O’Keeffe in 1916, the 52-year-old photographer and 28-year-old painter began a passionate love affair that led to their marriage in 1924 and an artistic adventure of ups and downs until Stieglitz’s death in 1946.

At the time, Stieglitz was already part of the New York City art establishment. In the early 1900s he founded the Photo-Secession, a movement to accept photography as an art form. His own work, particularly his city scenes, won praise for its softness and depth.

He also established his own gallery, where he exhibited O’Keeffe’s early abstract drawings before falling in love with her and considering her his muse.

After the couple wed, they moved into the Shelton Hotel (bottom image in 1929). A 31-story residential hotel that opened just a year earlier on Lexington Avenue between 48th and 49th Streets, it billed itself as the tallest hotel in the world at the time, with commanding views of the East Side of Manhattan.

Stieglitz and O’Keeffe took advantage of these views. From their apartment on the 30th floor, O’Keeffe painted several images of what she saw outside her window in the 1920s—industry along the East River, the lit-up windows of skyscrapers lining the business corridors of East Midtown after dark.

But one from 1928 struck me the most, and it’s simply titled “East River From the Shelton Hotel” (top image). Though the couple had very different styles and worked in different mediums, the painting feels very similar to a 1927 Stieglitz photo.

“From Room 3003—the Shelton, New York, Looking Northeast” captures the same expansive cityscape of neat and uniform low-rise tenement blocks and belching smoke along the riverfront.

Both works seem to hint that the East Side which came of age in the late 19th century would soon give way to the tall, sleek city of the Machine Age that Stieglitz and O’Keeffe were currently part of.

[First image: Metropolitan Museum of Art; Second image: Art Institute of Chicago; third image: MCNY, X2010.29.218]

December 12, 2022

A Yorkville tenement with mystery architectural details

The side streets of Yorkville are mostly old-school tenement blocks, and I’m a fan of these iconic Gotham residences. But it’s easy to walk past row upon row of these early 1900s walkups and not see the subtle design differences among them.

But sometimes you pass one that stands out. That’s the case with this five-floor low-rise at York Avenue and 75th Street.

If you view the York Avenue front, it looks like an ordinary tenement that lost its cornice but retains the evenly spaced rectangular windows and old-school fire escape characteristic of New York City tenements.

On the 75th Street side, however, are architectural details that appear almost Art Deco: geometric shapes with grooves between them and checkerboard-like ornamentation under some windows.

Perhaps 1409 York Avenue is an old-school tenement built at the turn of the century and then remodeled in the prewar decades to fit a more Moderne style. Or it’s a 1920s or 1930s building designed as kind of a cross between a tenement and a more contemporary style.

Building databases I’ve been looking pin the date it was built as 1910, which doesn’t seem right. In any case, it’s interesting to look at and wonder.

December 11, 2022

What happened to the young couple who held an 1896 winter wedding on Washington Square

It’s a lovely wintry scene that captures excitement, romance, and the Gilded Age beauty of a snow-covered Washington Square.

As twilight descends on the Square, well-heeled men and women alighting from elegant carriages make their way along the brownstone row of Washington Square North. From the front stoop of one of the brownstones, a man in a top hat and a woman in a stylish ruffled coat watch their arrival.

The people in the image aren’t just passersby—they’re wedding reception guests. This we know from the title of the painting: “A Winter Wedding—Washington Square, 1897.”

The artist is Fernand Lungren. After the turn of the century, Lungren gained fame for his southwestern desert paintings. Early in his career, he made a living in New York by doing illustrations for popular periodicals, such as Scribner’s Monthly and McClure’s.

I’ve always been curious about the scene. Who, exactly, is getting married here? A little digging led me to the names of the bride and groom—and what happened after the vows were recited and the reception ended.

“This picture shows New York’s upper crust arriving at the Square on the afternoon of December 17, 1896, to attend the wedding reception for Fannie Tailer and Sydney Smith held by the bride’s parents in their home at 11 Washington Square North,” wrote Emily Kies Folpe, in her 2002 book, It Happened on Washington Square. (Above, the row containing Number 11 circa 1900)

Fannie Tailer and Sydney J. Smith weren’t just typical new rich New Yorkers. Both came from old and socially prominent families. The Tailers were even part of the “Astor 400″—the infamous list of the highest echelon of society in the city, at least according to Caroline Astor and her social arbiter, Ward McAllister.

The couple met at the annual horse show, one of the events that marked the opening of the social season in Gotham. Tailer was an accomplished rider, while Smith was the scion of an old New Orleans family.

Their engagement hit the papers in 1895. Tailer “is justly considered not one of the prettiest but one of the handsomest young women in the ultra-fashionable set,” wrote the New York Times. About Smith, the Times stated that he had “sufficiency of worldly goods, is popular, [and] is more than well endowed with good looks.”

The wedding itself took place at 3 p.m. at Grace Church, at Broadway and 10th Street. Though many rich families had moved to elite neighborhoods like Murray Hill and upper Fifth Avenue in the 1890s, Washington Square North was still an acceptable place for a prominent family to live. Grace Church remained the choice place for these Greenwich Village residents to worship.

“The wedding, one of the largest and most fashionable of the season, brought out New York society—Astors, Belmonts, Havemeyers, Cooper-Hewitts, and others,” wrote Folpe. “Lungren seems to have observed the scene from the doorstep of his lodgings at 3 Washington Square, a row house converted into artists’ studios in 1879.”

After the swirl and excitement of this much-anticipated wedding, the couple mostly stayed out of the newspapers. Early on, they secured their own house on Washington Square. At some point they took up residence at Four East 86th Street.

And then, in 1909, came the split. “Sydney Smith’s Wife Sues for Absolute Divorce,” one front-page headline screamed. “Mrs. Smith did not take her usual place in the fashionable life of Newport last summer, but lived quietly with her children at a boarding house, and stories of marital unhappiness were revived in August when she and her husband [were part of] different parties at the Casino tennis matches, and did not speak to each other,” the story explained.

After the divorce, Mrs. Smith married C. Whitney Carpenter, a “broker” according to the New York Daily News. Still active in society, she seemed to live out her life in privacy, though she divorced a second time. She passed away in 1954, and her estate of $80,000 was divided between her two sons.

Sydney Smith also married again, to Florence Hathorn Durant Smith. He died in 1949 at age 81. He held the distinction of being the oldest member of the Union Club, which he joined in 1881, according to his New York Times obituary.

[Top image: Wikipedia; second image: New-York Historical Society; third image: Brooklyn Citizen; fourth image: New-York Tribune; fifth image: Baltimore Sun]

December 5, 2022

Looking for the backstory of an abandoned Chelsea tavern

For years I’ve walked by the delightfully shabby Joe’s Tavern sign at the corner of Tenth Avenue and 25th Street.

I’ve never seen the vintage vertical beauty lit up, unfortunately. Even stranger, I’ve never seen any sign of life inside 258 Tenth Avenue, which once housed what I imagine to have been an old-school neighborhood bar on the ground floor. The place has been long left to the elements, its facade papered over with fashion ads.

Who was Joe? There’s not much to go on. The Lost City blog, now defunct but still a lively source of New York City historical insight, featured the sign in a 2013 post. A year later, a commenter wrote that Joe was the “very friendly” Hungarian-American old man behind the counter.

What happened to Joe, and why his bar was abandoned as far back as the 1990s, remains unknown. There’s not a lot of clues to go on. Old city directories aren’t pointing the way. I made out the faded outline of “258” in an old-timey font above the entrance, but that’s about it.

Still, a look into 258 Tenth Avenue’s backstory didn’t come up totally empty. Turns out, the tavern roots of this place go back to the 19th century.

According to an 1895 edition of the New York Times, a man named Martin P. Grealish ran a saloon in this very spot. Grealish made the paper because he was moving his saloon down to 200 Tenth Avenue. (Understandable, as his landlord was raising his rent).

A 1920s New-York Historical Society photo (second image above) reveals that the site had become the Majestic Restaurant. Perhaps the Majestic turned into a restaurant thanks to Prohibition…then returned to a watering hole once that national experiment was over.

John Sloan’s “obvious delight” with Jefferson Market Courthouse

As a prolific painter living on Washington Place and working out of a high-floor studio at West Fourth Street, John Sloan had a wonderful window into the heart of the Greenwich Village of the 1910s—its small shops, bohemian haunts, immigrant festivals, and all the life and activity of the elevated trains up and down Sixth Avenue.

[“Jefferson Market, Sixth Avenue,” 1917]

He also had a view of Jefferson Market Courthouse. Once the site of a fire tower and market that opened in 1832, the Victorian Gothic courthouse with its signature clock tower replaced the original structures at Sixth Avenue and 10th Street in 1877.

Like contemporary New Yorkers, he seemed to be enchanted by the Courthouse, which functions today as a New York Public Library branch. He was so entranced by it, Sloan put it in several of his works, either as the main subject or off to the side.

[“Sixth Avenue El at Third Street,” 1928]

“Sloan obviously delighted in the irregular rooftop patterns and the spires of several other structures beyond, contrasting the soaring tower and the gables of the courthouse with the swift rush of the Sixth Avenue elevated railroad below,” explained William H. Gerdts in his 1994 book, Impressionist New York.

His interest wasn’t just in the building’s architectural value. Sloan, a keen observer of what he described as New York City’s “drab, shabby, happy, sad, and human life,” regularly visited the notorious night court there to witness the human drama that appeared before judges—men and women typically brought in for drunkenness, prostitution, and petty crime.

[“Jefferson Market Jail, Night,” 1911]

“This is much more stirring to me in every way than the great majority of plays. Tragedy-comedy,” he said about the night court, per Gerdts’ book.

“Sloan was obviously drawn to the building’s. picturesque mass as well as its physical and symbolic situation with Greenwich Village, and no other New York structure, not even the Flatiron Building, enjoyed such distinctive monumental rendering by him,” wrote Gerdts.

“Snowstorm in the Village,” an etching from 1925, shows Jefferson Market Courthouse’s gables and turrets covered in snow and is worth a look here.

[Top image: Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts; second image: Whitney Museum; third image: paintingstar.com]