Theresa Smith's Blog, page 119

November 19, 2018

New Release Book Review: Shell by Kristina Olsson

About the Book:

A big, bold and hauntingly beautiful story that captures a defining moment in Australia’s history.

Everywhere he looked he saw what Utzon saw. The drama of harbour and horizon, and at night, the star-clotted sky. It held the shape of the possible, of a promise made and waiting to be kept …

In 1965 as Danish architect Jørn Utzon’s striking vision for the Sydney Opera House transforms the skyline and unleashes a storm of controversy, the shadow of the Vietnam War and a deadly lottery threaten to tear the country apart.

Journalist Pearl Keogh, exiled to the women’s pages after being photographed at an anti-war protest, is desperate to find her two missing brothers and save them from the draft. Axel Lindquist, a visionary young glass artist from Sweden, is obsessed with creating a unique work that will do justice to Utzon’s towering masterpiece.

In this big, bold and hauntingly beautiful portrait of art and life, Shell captures a world on the brink of seismic change though the eyes of two unforgettable characters caught in the eye of the storm.

And reminds us why taking a side matters.

My Thoughts:

‘There was no Swedish word to describe this, no English word that he knew; it wasn’t as simple as ‘awe’ or even ‘love’. It was the clutch at his heart as he lifted his eyes to its curves and lines. Its reach for beauty, a connection between the human and the sublime.’

Since its release last month, in my capacity as editor for historical fiction with the Australian Women Writers Challenge, I have read quite a few reviews on Shell, with no one reviewer saying the same thing. This in itself was reason enough for me to want to check it out and form my own opinion, but in the end, it was Lisa from ANZ LitLovers LitBlog who really persuaded me to read this novel post haste (do check out her review here). But it wasn’t all love at the first chapter for me, I will admit this and for the first seventy odd pages, I really felt as though I just couldn’t put my finger on the pulse of what was happening. There was a vagueness to the narrative which, to me, evaded full disclosure. It was almost as though I had to read between the lines of what was being alluded. However, in hindsight, I can note that these initial impressions can probably be attributed to the way in which I was reading the novel, more than the novel itself. I was picking it up in short bursts on Saturday, in between hanging out copious amounts of washing and acting as a taxi for my children all day long. Anyway, it wasn’t until I was able to really settle down with Shell in the evening that this dawned on me. Because all of a sudden, without distraction, I realised that this novel was actually quite exceptional.

‘Her own rollies had never tasted as sweet as she’d imagined. She’d thought they’d be just like those mornings, which held the deep flinty smell of her father’s breath and skin, like the embers of old kindling. She’d searched for years for precisely the right tobacco, settling recently for a blend of plum and spice she found consoling, if not sweet. Those hours with her father re-enacted in the rhythm of the match striking, the tobacco catching, the shape of thumb and forefinger around the smoke.’

There are so many moments of introspection from both of the main characters, Pearl and Axel, that gave me pause for reflection. Passages I read two, and even three times, just enjoying the beauty of the words and the way Kristina Olsson strings them together. This is why I needed to sink into the novel, rather than just pick it up and put it down over and over. While the narrative is engaging, it’s the beauty of the unsaid that takes this novel to the next level, and in order to appreciate the unsaid, you need time and no distractions.

‘She looked up, and between half-heard words and phrases, in the shifting space between earth and sky, she saw it: the boys had been abandoned by them all. Mother, father, sister. Through death, grief, selfishness – in one way or another, they’d each disappeared, left them. Leaving was what her brothers knew. What they expected.’

I have never actually been to the Opera House. The most I’ve seen of it is from the window of an airplane as we cruised into Sydney on an international connection flight. I have no physical context for which to place this story, no visual memories to draw on, yet while reading about it in Shell, I could picture the intricacies perfectly, her descriptions so precise and detailed that visiting the Opera House was not a prerequisite for enjoying this novel – to my relief, because some reviews I have read were from people who have visited the Opera House and they all mentioned how this helped them with the visualisation of its creation as it was described within the novel. Rest assured, if you are like me and haven’t yet had the pleasure of visiting, it’s not going to impact on your appreciation of this aspect of the novel. I never knew that there was so much controversy surrounding its construction. Seeing this all unfold through Axel’s eyes provided an insightful perspective, particularly his thoughts on Australians and the way we consider beauty and culture. In particular:

‘It wasn’t that they didn’t understand beauty. But there was a sense of being embarrassed by it, that it was an indulgence. The practical was held in such esteem. It made them too polite.’

And:

‘Australians appeared to have no myths of their own, no stories to pass down. He’d read about the myths of indigenous people, the notion of a Dreaming and the intricate stories it comprised. He wondered if Utzon knew these legends, their history in this place. Had he known anything of Aboriginal people when he designed his building? As he sat down and drew shapes that could turn a place sacred? Turn its people poetic: their eyes to a harbour newly revealed by the building, its depths and colours new to them, and surprising. Perhaps that was what the architect was doing here: creating a kind of Dreaming, a shape and structure that would explain these people to themselves. Perhaps the building was just that: a secular bible, a Rosetta stone, a treaty. A story to be handed down. If people would bother to look. If they’d bother to see.’

One more:

‘But in this country, he saw, it was a kind of sport to belittle those with vision, to treat art with disdain. He wasn’t sure what benefit it brought, but it was something to do with this flattening out, this shuffle towards sameness, to a life lived on the surface, without any depth. Was that why people clung so hard to the edges of the country, their backs to its beating red heart? Were they afraid to look in, to hear the old stories, to see what was inscribed on their own hearts and land?’

You see what I mean though? There are so many passages that just reach out to you with their intent.

The other topic of prominence within this novel is the introduction of conscription for the Vietnam War, and the way this divided people. I found this particularly interesting and it’s kind of changed my view to a certain extent on the way the Vietnam War was being protested against by the Australian public. I can’t help but consider the weight that conscription must have added to the ill-sentiment that was already prevalent. Would the absence of conscription have led to a more respectful return for our troops that had served in this war? I love it when a novel can get my mind working like this.

‘They were 18 and 19 then, not old enough to vote. To get a passport, buy a house or a beer. But they could be forced into army fatigues, she thought now, biting her lip. Given a gun to kill boys just like them, boys they didn’t know, had never seen.’

I have no doubt that Shell is one of those novels we will see a lot of next year as it pops up on longlists and (hopefully) shortlists for awards. It is a literary work of fiction, I only point this out because some readers prefer not to dive into these, but if you’ve been on the fence about whether or not to read Shell, I urge you to just go for it. If you love a novel that gives you beautiful prose threaded with thought provoking content set against a background of real historical events, then Shell just might be the perfect read for you.

‘The passage of time, of life, from one realm to another, the traces left for others.’

November 18, 2018

New Release Book Review: The Way of All Flesh by Ambrose Parry

About the Book:

A vivid and gripping historical crime novel set in 19th century Edinburgh, from husband-and-wife writing team Chris Brookmyre and Marisa Haetzman.

Edinburgh, 1847. City of Medicine, Money, Murder.

Young women are being discovered dead across the Old Town, all having suffered similarly gruesome ends. In the New Town, medical student Will Raven is about to start his apprenticeship with the brilliant and renowned Dr Simpson.

Simpson’s patients range from the richest to the poorest of this divided city. His house is like no other, full of visiting luminaries and daring experiments in the new medical frontier of anaesthesia. It is here that Raven meets housemaid Sarah Fisher, who recognises trouble when she sees it and takes an immediate dislike to him. She has all of his intelligence but none of his privileges, in particular his medical education.

With each having their own motive to look deeper into these deaths, Raven and Sarah find themselves propelled headlong into the darkest shadows of Edinburgh’s underworld, where they will have to overcome their differences if they are to make it out alive.

My Thoughts:

‘That was Edinburgh for you: public decorum and private sin, city of a thousand secret selves.’

The Way of All Flesh is a dark journey down into the depths of Victorian Edinburgh, back to the beginnings of surgery and obstetrics, when anaesthetic was only just in its infancy. This is a novel that traverses a grim and often macabre path, but always an historically accurate one. This is pre-caesarean days as well, and the main character is apprenticed as an obstetrician, so we are privy to some distressing childbirth practices. While this novel is most definitely not for the feint hearted, I absolutely loved it, even if it did make me cringe and squirm on more than one occasion. There is just so much in it history lovers, particularly of the Victorian era, will appreciate. The sense of being on the cusp of discovery, with more humane surgical practices just within reach, is richly explored. The entire novel beats with atmosphere and the characterisation is precise.

Raven and Sarah, our two main characters, have an interesting dynamic between them that flexes throughout the novel, changing as they each learn more about the other. Raven is not entirely who he says he is, presenting himself as a young man of the right class for entering a career in medicine, but Sarah is having none of it. She sees right through him from the start, and while her instincts are correct, her judgement of him is off base. Raven embodies the definition of a doctor who wants to improve the lives of his patients. While his personal history may be checkered, his motivations are pure. Sarah herself was a wonderfully drawn woman, condemned by her sex and class into a life of servitude, but Dr Simpson, her employer, sees her intelligence, her natural ability with pharmaceuticals, and tries his best to nurture this despite her station. Mixed in with the medical history, the crime and mystery, is a skilfully rendered story about the many challenges women faced in Victorian times.

‘Sarah occasionally amused herself by dwelling on the notion of herself as a student: what her days would have been like and which subjects she might have liked to study. She had an interest in botany and horticulture, as well as in the traditional healing arts, inherited from her family background. Any time spent in the professor’s study caused her to marvel at all of the myriad disciplines and fields of knowledge one might explore, and the idea of spending whole years doing precisely that seemed heavenly. However, this was a distraction that came at a price, for although it was pleasant to indulge such fantasies, they also forced her to confront the harsh truth. She had not the means to attend university nor any prospect of ever acquiring them. Being female was also an obstacle that she could not easily overcome.’

The Way of All Flesh is a brilliant novel of historical fiction, the kind that entertains as much as it informs. While I solved the crime before the characters did – a rare occurrence for me – the execution of the mystery was cleverly done. I will be forever thankful that obstetrics has progressed so far from Victorian times, and truly, any woman who has given birth who reads this novel will feel the same! I highly recommend The Way of All Flesh and look forward to reading more from Ambrose Perry.

November 16, 2018

Bingo! The Perils of Too Much Fun

[image error]

So far, November has brought on a lot of social activity for this introverted bookworm. Last Saturday night, my daughter and I went to see the Teatro Alla Scala Ballet Company perform Don Quixote, which was brilliant! This event marked the beginning of the ‘crazy phase’ which sees my calendar filled with graduation balls, work Christmas parties, dance concerts, and an endless stream of parties and get-togethers that my teenagers JUST HAVE to go to, which means I have to drive them to and from and all of that staying up late makes me very tired. It’s all cutting into my reading time, which is why I completely lost this last week and only realised this morning as my calendar pinged at me that I’d FORGOTTEN BINGO!!

I have my last two books all picked out, they just haven’t been read yet. My remaining two categories and selected titles are:

[image error]

A book written more than 10 years ago

[image error]

A foreign translated novel

‘The plan’ is to have these both read by the next bingo round…

This year I’m playing book bingo with Mrs B’s Book Reviews. On the first and third Saturday of each month, we’ll post our latest entry. We’re not telling each other in advance what we’re currently reading or what square we’ll be filling next; any coincidences are exactly that – and just add to the fun!

Follow our card below if you’d like to join in, and please let us know if you do so we can check out what you’re reading.

Now I’m off to check out what square Mrs B has marked off for this round. See you over there!

[image error]

November 14, 2018

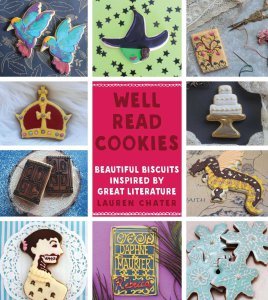

New Release Book Review: Well Read Cookies by Lauren Chater

About the Book:

This gorgeous, whimsical gift hardback celebrates beloved works of literature in the shape of beautiful iced biscuits. Feast your eyes on 60 mouth-watering classics in full colour from Jane Austen and Mary Shelley to Tolkien and F. Scott Fitzgerald, modern masterpieces by Margaret Atwood, Neil Gaiman, Geraldine Brooks and Melissa Ashley, and beloved children’s tales by Dr Seuss and J.K. Rowling.

With all the tender love and care of a true book lover, author and baker extraordinaire Lauren Chater shows you how to translate your favourite books to the plate – and start making your very own sweet morsels of edible art. Filled with beautiful photographs and insider tips on achieving cookie nirvana, now you can have your books and eat them too.

Lauren Chater is the founder of the popular blog, The Well-Read Cookie, and author of the acclaimed historical novel The Lace Weaver.

My Thoughts:

Well Read Cookies is a delectable treat of a book to curl up with. Founder and creative force behind the successful The Well Read Cookie blog, Lauren Chater has compiled a collection of her favourite books in biscuit form for our reading and viewing pleasure. This book is not one to nibble at, I guarantee you will scoff the lot in one sitting. Lauren and I have similar reading tastes so I took great pleasure in discovering some of my favourite books depicted as biscuits. I’ve also added a few more titles to my reading pile as well. This is not just a book filled with pictures of unbelievably creative and gorgeous biscuits. Each one is also an ode to the book that inspired the biscuit. Lauren gives a review, for want a better description, on what she loves about each book and which part or aspect of the text that the inspiration for the biscuit design came from. There are biscuit recipes in the back along with tips on icing and decorating for the bakers out there. For me though, I draw the most pleasure from studying the clever creations Lauren has come up with and while I’m unlikely to ever attempt my own biscuit, I’ll definitely be returning to these pages over and over. Well Read Cookies is a perfect gift for those who love books. I’ve already bought an extra copy for a friend and have plans on buying a few more.

November 13, 2018

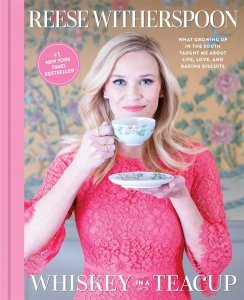

New Release Book Review: Whiskey in a Teacup by Reese Witherspoon

About the Book:

Academy Award–winning actress, producer, and entrepreneur Reese Witherspoon invites you into her world, where she infuses the southern style, parties, and traditions she loves with contemporary flair and charm.

Reese Witherspoon’s grandmother Dorothea always said that a combination of beauty and strength made southern women “whiskey in a teacup.” We may be delicate and ornamental on the outside, she said, but inside we’re strong and fiery.

Reese’s southern heritage informs her whole life, and she loves sharing the joys of southern living with practically everyone she meets. She takes the South wherever she goes with bluegrass, big holiday parties, and plenty of Dorothea’s fried chicken. It’s reflected in how she entertains, decorates her home, and makes holidays special for her kids—not to mention how she talks, dances, and does her hair (in these pages, you will learn Reese’s fail-proof, only slightly insane hot-roller technique). Reese loves sharing Dorothea’s most delicious recipes as well as her favourite southern traditions, from midnight barn parties to backyard bridal showers, magical Christmas mornings to rollicking honky-tonks.

It’s easy to bring a little bit of Reese’s world into your home, no matter where you live. After all, there’s a southern side to every place in the world, right?

My Thoughts:

Whiskey in a Teacup might just be the most joyous non-fiction book I’ve ever read. It’s a blend of memoir, lifestyle, beauty, recipes, etiquette, family and Southern social history, accompanied by a collection of gorgeous photographs throughout. Beautifully presented, it’s an ideal coffee table book and would make a perfect gift on account of its broad content.

Reese Witherspoon is of course a household name, but this book is by no means a glorification of herself and how famous she is. Overall, I felt like Whiskey in a Teacup just confirms what we’ve all been suspecting: that Reese is a really nice woman who loves her family, her Southern heritage, and sharing her lifestyle with those she is closest with. The entire book is refreshingly devoid of name dropping and stardom, with the only exceptions occurring when Reese is fan-girling over a celebrity herself (which just further enhances her ability to connect to others). I’ve always liked Reese as an actress, but after reading Whiskey in a Teacup, I now like and admire her as a woman who has created a successful business and followed her passion, while maintaining an impeccable public image. Reese writes in an intimate style, sharing stories and recipes, ideas and beliefs. Her grandmother Dorothea was a huge influence in her life and I guess I probably related to this the most, as both of my grandmothers had a profound influence on my life and many of the things Reese writes about with regards to her grandmother really hit home for me. Dorothea had some great advice to impart, but for me, this one was absolute gold:

‘Poor Dorothea would not be happy to see how many people travel in athletic wear these days. “You don’t wear sweatpants on an airplane,” she used to say. “It’s a privilege to fly. Make sure you wear a nice outfit.” I guess she is why I have a real mental block about wearing workout wear all day long. I just don’t do it. I think you gotta get up, you gotta work out, and then you gotta get dressed in a real, proper outfit by ten in the morning. I would never judge anyone for doing otherwise. But if I did it myself, I just know my grandmother would haunt me with that line she always said: “Only wear sweatpants when you’re supposed to be sweating.’”

Anyone who knows me personally will not be surprised that this spoke to me on an intimate level. I loathe the trend of wearing active wear as regular clothes and have been applying my best efforts at ensuring my daughter understands that active wear is not all day wear.

I’ve personally always been interested in the social geography of America’s South and this book is a great anecdotal account of the customs and lifestyles that are unique to this region. While Reese’s South is viewed through the lens of privilege, and let’s be honest, not everyone in the South is on the same level as Reese Witherspoon, by writing Whiskey in a Teacup as an ode to her family, we can appreciate that this is Reese’s South, not THE South. Whiskey in a Teacup is a beautiful tribute to Reese’s Southern heritage and will no doubt become a treasured book for her own children one day.

November 11, 2018

New Release Book Review: Unsheltered by Barbara Kingsolver

About the Book:

The international bestselling author of The Lacuna, Flight Behaviour and The Poisonwood Bible and recipient of numerous literary awards – including the National Humanities Medal, the Dayton Literary Peace Prize, and the Orange Prize – returns with a timely novel that interweaves past and present to explore the human capacity for resilience and compassion in times of great upheaval.

2016 Vineland

Meet Willa Knox, a woman who stands braced against an upended world that seems to hold no mercy for her shattered life and family – or the crumbling house that contains her.

1871 Vineland

Thatcher Greenwood, the new science teacher, is a fervent advocate of the work of Charles Darwin, and he is keen to communicate his ideas to his students. But those in power in Thatcher’s small town have no desire for a new world order. Thatcher and his teachings are not welcome.

Both Willa and Thatcher resist the prevailing logic. Both are asked to pay a high price for their courage. But both also find inspiration – and an unlikely kindred spirit – in Mary Treat, a scientist, adventurer and anachronism.

A testament to both the resilience and persistent myopia of the human condition, Unsheltered explores the foundations we build in life, spanning time and place to give us all a clearer look at those around us, and perhaps ourselves. It is a novel that speaks truly to our times.

My Thoughts:

“No creature is easily coerced to live without its shelter.”

“Without shelter, we stand in daylight.”

“Without shelter, we feel ourselves likely to die.”

I always find it exceptionally difficult to review a novel that I love. You’d think it would be the easiest task ever, but I tend to procrastinate and dither around, putting it off, because the pressure of doing the novel justice weighs a bit too heavily. The irony of this is of course, in delaying my review of the novel, I’m definitely not doing it any justice at all. Twenty years ago I bought a new release novel that was selling cheap on account of it being a damaged copy. It was only the cover so I really didn’t care because I was still at university and very, very poor. That novel was The Poisonwood Bible and it had such a profound impact on me. Until I read Unsheltered, The Poisonwood Bible was still my favourite novel. Now it’s my second favourite. Barbara Kingsolver writes about as near to perfection as is humanly possible. Unsheltered is a novel for our times, it truly is. And I believe that it will have the most impact read now, in its present time of release. I’m not suggesting that it lacks a timelessness quality, more that its impact is wholly relevant today. For us, as we live in what has become an unsheltered time.

‘It’s going to be fire and rain, Mom. Storms we can’t deal with, so many people homeless. Not just homeless but placeless. Cities underwater and then what? You can’t shelter in place anymore when there isn’t a place. The Middle East and North Africa are almost out of water. Asia’s underwater. Syria is dystopian, Somalia, Bangladesh, dystopian. Everybody’s getting weather that never happened before. Melting permafrost means we’ve got like, a minute to turn this mess around, or else it’s going to stop us.’

The title ‘Unsheltered’ means many things. Within the context of the quote above, it’s about humanity becoming unsheltered as the world shifts under the effects of our habitation. On the more domestic level, for Willa, our present day protagonist, the things she expected to shelter her into retirement are no longer there: job security, affordable healthcare, a secure life for her children, higher education paying for itself through well paid and secure jobs. She’s living in poverty in an inherited house that is falling apart with her dying father-in-law, husband, two under-employed adult children and one tiny motherless grandson. She’s unsheltered, and no matter how hard she fights against it, things are not changing.

‘She aimed to be immune to the ambitions and disappointments that had maimed her parents’ existence and now were stirring up a national tidal wave of self-interest that Willa found terrifying. It was pretty clear there would be no stopping the Bullhorn, or someone like him. Here was the earthquake, the fire, flood, and melting permafrost, with everyone still grabbing for bricks to put in their pockets rather than walking out of the wreck and looking for light.’

Within the historical era of this novel, the concept of being unsheltered can be applied to a much broader context. Set in the early 1870s, at the conception of Darwin’s theory of evolution, the sheltered existence of those living in Vineland, a man-made capitalist utopia, is being threatened by science, knowledge, and the questioning of the creation of the universe, which of course, like dominoes cascading, leads to the questioning of everything.

‘A great shift was dawning, with the human masters’ place in the kingdom much reduced from its former glory. She could see how this might lead to a sense of complete disorientation in the universe. But still. The old paradigm was an obsolete shell; the writing on the wall was huge. They just wouldn’t read.’

At the heart of this is Thatcher Greenwood, a science teacher struggling against the constraints of teaching at the high school in Vineland.

‘I submit my lesson plans and he overrules all but the most mundane exercises in rote memory. Experimentation alarms him. Modern scientific theory enrages him, discussion of Darwin particularly but not only this. The suggestion of taking pupils outdoors to study nature, he treats as blasphemy.’

And then there’s Mary Treat, his neighbour, a woman living an unsheltered existence in the sense that she is a woman living alone in 1871. Her husband left her for the pursuit of a suffragette, and she’s not sorry to have seen the back of him. Some ten years older than Thatcher, the two form an instant friendship, spurred on by a mutual interest in science and a belief in the theory of evolution.

‘She was a real scientist. But into domestic things, bird nests and spider towers. How they learned to build them, what forces affected their survival. Evolution was a new idea, so I guess nature wasn’t just a cabinet of curiosities anymore. It was a machine, and everybody was keen to know what made it tick.’

Between Mary and Thatcher there rests a world of admiration.

‘The childhood wasted in curtseying lessons, the grasp of taxonomy and chemistry entirely self-taught, and still she had marched her theories to the doorstep of Asa Gray. Whereas Thatcher, when he once met the great man coming through the door of the Harvard library, had gone pale with the effort of trying to say good morning. How did a person come to be Mary Treat? He could stand all day watching energy, logic, and indifference to judgement combine with such glorious force.’

Both a scientific story as well as a very human story, Unsheltered is a novel that covers a terrific range of issues. Everything in the present day is paralleled with the story of the past: that crossroads for humanity where we have to question everything that has come before; the greed of a few at the peril of many. Barbara examines the rise of Trump via her character, The Bullhorn, and this set against Landis in the 1870s, the self appointed ‘President’ of Vineland. In her author notes, Barbara informs us that much of the 1870s storyline is based on fact and actual people. Some of the more outlandish things are actually the ones that turn out to be true. One of my favourite characters was Tig, Willa’s daughter. She comes to offer so much perspective on life right now, particularly on matters related to the environment, wastage and the state we are leaving the planet in for our beloved offspring. She regards reusing everything with a romanticism that appealed to me, but she was in no way at all naive. Her eyes were wide open, and just as Tig gave Willa much to think on, she’s done the same for me.

‘People are careless. If they break it there’s always more. But in Cuba, whatever it is, you probably can’t get more, so people take care. When you pick up a glass it’s like you’re raising a toast to all the people that drank from it before. All those happy anniversaries in a beautiful place, and all the future ones. It made me so happy, Mom. That night was our turn. We got to be in the treasure chest of time.’

Linking the two stories, past and present, is the house, the legacy of Thatcher and Mary, and the town of Vineland, that still exists, but in a different form. More specifically, Barbara links the past to the present by titling each of the chapters with the last words from the previous chapter. In terms of dual timeline narratives, Unsheltered could become the text on how it’s done.

Love is tangled with grief all through Unsheltered and examined in minute detail. Willa deconstructs her relationship with her husband, her father-in-law, her son, and her daughter. It’s that last relationship that benefits most from this introspection. As Willa comes to accept that she doesn’t fully understand her adult daughter and possibly never has, she winds up understanding her perfectly. I loved how their relationship became stronger throughout this story. There was something about Willa and Tig learning to be adults together within their mother and daughter relationship that appealed to me greatly.

‘To spend a night like this, inches from her daughter’s skull and everything it held inside, was a tender agony Willa could have explained to no one but her mother.’

For Thatcher and Mary, love was secondary to their story, but it triumphs over their adversity. For love to develop upon a foundation of such respect and admiration is a truly beautiful thing.

‘I sometimes feel I ought to take the pins from your hair and make my home in it, like a bird in a tree.’

There’s probably a million more words I could write about this novel. I loved it so much. Even when going back over the quotes I had marked for reflection, I found myself lingering over the passages either side, revisiting the story with enthusiasm. There’s a terrific interview with Barbara in this month’s Good Reading magazine. She provides a more articulate account than this on the themes contained within Unsheltered. I hope I’ve persuaded you to at least take a look at Unsheltered. It a brilliant novel, thought-provoking and beautifully written with a deep intelligence. If you’ve never read Barbara Kingsolver novel before (cue the horrified gasp) you won’t find a better one than this to start with.

‘A common mistake in thinking about the past is to assume people were more childlike than we are now.’

Quick Shots Book Review: The Cry (TV tie-in) by Helen FitzGerald

About the Book:

Coming to ABC TV, the 4-part BBC TV drama, The Cry by Helen FitzGerald brings a parent’s worst nightmare to vivid life.

When a baby goes missing on a lonely roadside in Australia, it sets off a police investigation that will become a media sensation and dinner-table talk across the world.

Lies, rumours and guilt snowball, causing the parents, Joanna and Alistair, to slowly turn against each other.

Finally Joanna starts thinking the unthinkable: could the truth be even more terrible than she suspected? And what will it take to make things right?

Perfect for fans of Julia Crouch, Sophie Hannah and Laura Lippman, The Cry was widely acclaimed as one of the best psychological thrillers of the year. There’s a gripping moral dilemma at its heart and characters who will keep you guessing on every page.

My Thoughts:

‘There was a long silence before she said: “This is wrong. I’m not going to do it.” Alistair sat on the bed beside her and held her hand. “We lost our son. We don’t deserve to lose everything else as well. It’s not wrong. We’re not hurting anyone.”’

The Cry was a fantastic read. It’s the type of thriller that lets you think you know what’s happening until one innocent remark sees everything that came before turned on its head. With themes of guilt, grief, self-doubt, depression, and postnatal depression, it’s a concise novel that covers a lot of ground with precision and empathy. I liked and felt varying degrees of sympathy for both of the female protagonists, Joanna and Alexandra, and a whole lot of disdain for Alistair, a man who takes master manipulator to a whole new level.

‘She was going mad. She needed more than antidepressants. The line that connected her to him stuck to her like a shadow, stretching, holding her, then banging her off to her next position.’

The Cry has been re-released as a TV tie-in edition to accompany its adaptation into 4-part BBC drama, to air also on the ABC here in Australia. I am keen to see how this story pans out on the small screen. If it remains true to the novel, it is bound to be emotionally turbulent and utterly gripping.

November 8, 2018

New Release Book Review: A Perfect Stone by S.C. Karakaltsas

About the Book:

How do you find a place to belong when there’s nowhere else to go?

Living alone, eighty-year-old Jim Philips potters in his garden feeding his magpies. He doesn’t think much of his nosy neighbours or telemarketers. All he wants to do is live in peace.

Cleaning out a box belonging to his late wife, he finds something which triggers the memories of a childhood he’s hidden, not just from his overprotective middle-aged daughter, Helen, but from himself. When Jim has a stroke and begins speaking another language, Helen is shocked to find out her father is not who she thinks he is.

Jim’s suppressed memories surface in the most unimaginable way when he finally confronts what happened when, as a ten-year-old, he was forced at gunpoint to leave his family and trek barefoot through the mountains to escape the Greek Civil War in 1948.

A Perfect Stone is a sweeping tale of survival, loss and love.

My Thoughts:

‘During the Greek Civil War, it is estimated that there were up to 38,000 Aegean Macedonian and Greek children removed from their homes.’

The power of A Perfect Stone lies in its historical narrative, outlining the fate of Greece’s children during the years of the Greek Civil War. It’s an interesting account of one the side effects of war, the displacement of children via evacuation to ensure their safety. I’m not a huge fan of child narrators, but in this instance, it enhanced the story greatly. By journeying in Dimitri’s shoes as he was removed from his home, not given any information on where he was going and why – I can only assume that children weren’t entitled to know their own fate on account of being children – we are fully immersed in his perilous and fearful journey.

‘They know instinctively the forest will protect them from being seen and the first children desperately run to its safety. But too many are out in the open when a blackbird swoops past and the first ear-splitting explosion lights the side of the mountain.’

The heavy uncertainty that must have weighed on these children is conveyed so well and made for compelling reading. This is the first in-depth account of the Greek Civil War that I have read and it piqued my interest enough to set out and research it more fully. The end of WWII was not the end of war for many nations, some left in a state of destruction and desolation. I am finding myself more and more interested in this immediate post-war period of civil unrest.

‘In 1949, when the Civil War ended, Dimitri and the rest of the Macedonian children were told that the Greek Government had decreed them to be Greek, and the teaching of their language stopped. The Red Cross interviewed them and tried to reunite children with families. One by one they left until the only remaining children were orphans who became wards of the state.’

The women who spirited these children to safety were true heroes in my opinion. I would love to read more on this, but from their perspective. Carrying the weight of their own loss, these women travelled with large groups of children through rough terrain, uncertain of enemy occupation, with little to no food and water. In some cases, the only thing carrying them forward must have been a belief that what they were heading to was better than what they had left behind. I wonder if I would have the strength to be like these women, your own children dead, your husband most likely dead as well or imprisoned, trekking through forests and scaling a mountain while hiding from the enemy with a dozen or more children and other grieving women depending upon you for safe passage. Extraordinary.

‘A woman begins to hum. Then another. Soon they’re singing quietly and some of the children join in. It’s a song from home. A lullaby for babies. The children remember and for a short time they forget their tiredness, hunger and pain.’

Dual timeline narratives are tricky beasts, but they are booming in popularity at present. Regular readers of this blog will know that I have read a lot of these sorts of novels on account of my love for historical fiction. But they’re not my favourite mode of storytelling when it comes to this genre. Invariably, the contemporary story is linked to the historical one via a forgotten or mysterious box containing a photo or piece of memorabilia, letters or a diary. I’m not trying to be harsh here, but I’ve honestly, with no exaggeration, read hundreds of dual timeline narratives, probably half of them war related. I’ll overlook this commonality if the contemporary story is strong, and by that, I mean, it can hold its own in terms of story engagement and character development. The contemporary story in A Perfect Stone didn’t measure up for me. It wasn’t substantial enough, and it wasn’t engaging enough. I could certainly see the foundations the author was laying, but Jim was too sketchy to carry this narrative on his shoulders and the contemporary story came off as more of a filler than a driving force. A straight historical set during the years of the Greek Civil War would have carried more weight in my opinion, as the author seems very much at home within the historical fiction genre.

For anyone interested in reading about the Greek Civil War, A Perfect Stone is a good place to start. It’s a powerful tale of survival and loss, grounded in history.

November 5, 2018

New Release Book Review: Lillian’s Eden by Cheryl Adam

About the Book:

In Lillian’s Eden, debut novelist Cheryl Adam takes the reader to Australian rural post-war life through the life of a family struggling to survive. With their farm destroyed by fire, Lillian agrees to the demands of her philandering, violent husband to move to the coastal town of Eden to help look after his Aunt Maggie.

Juggling the demands of caring for her children and two households, and stoically enduring her husband’s continued indiscretions, Lillian finds an unlikely ally and friend in the feisty, eccentric Aunt Maggie who lives next door.

With wonderfully drawn characters reminiscent of Ruth Park and Kylie Tennant, Cheryl Adam shows us the stark realities of rural life behind the closed front doors and scented rose-filled gardens. She highlights the endless physical and mental demands on women like Lillian who have to grapple with the challenges of a new homeland as well as never ending family responsibilities.

This rich, raw novel pays homage to friendship and to the rural women whose remarkable resilience enabled them to find happiness in sometimes the most unlikely of places.

My Thoughts:

Lillian’s Eden has a rather classic feel to it, harking back to life during the 1950s in rural Australia. In many ways, it is reminiscent of The Dressmaker and Cloudstreet, with its element of the ridiculous that only comes with this type of nostalgic Australian fiction. Unflinchingly honest, this is a novel that will have you in stitches from laughter while stealing your breath away with its emotional intensity.

‘She cursed the day she had encouraged Aunt Maggie’s coffin idea. Eric thought she was pulling his leg when she told him, but he’d happily obliged. They’d given her their tea chests, helped her move an old bed into the shed and lent her tools. Building the coffin would keep Aunt Maggie occupied, stop her from bossing them around for a while. Lillian and Eric had complimented Aunt Maggie on her craftsmanship and laughed in the kitchen when her shed had rung with the sound of hammering. That’s how it went until the coffin was near completion. Now she was holding coffin practices. And these the whole family were expected to attend.’

Devoid of stereotypes, the characters that people this novel are richly rendered and highly memorable. The story itself is driven more by the characters and their dynamism than any actual events, and it’s in this where the story gets that ‘classic’ feel. We really are being treated to a slice of life, early 1950s, in small town Australia, warts and all. Many of the issues explored throughout Lillian’s Eden are relatable to contemporary times and none of the characters are passively sitting back within their own lives. Lillian and Maggie are both smart, strong, progressive women. So are Lillian’s daughters. Yet circumstances and societal expectations within the era are holding them all pinned in place. There were many entertaining moments throughout this novel, but my favourite would have to be Lillian’s mini breakdown over the laundry copper breaking:

‘Lillian looked at the red blister forming on Splinter’s foot and saw the water leaking through a small hole in the copper. It settled into a puddle of steam on the cement floor. She gazed around the hut that stole her Mondays: thought of the roses she had nurtured; cuttings she’d stolen from wealthy gardens at night armed with Aunt Maggie’s secateurs; the shooting, and something broke inside her. Grabbing the wash pole, she charged the clothesline. Pinioned forms swung and jerked beneath her blows. Sheets wrestled the pole as she belted the blazes out of them. Her eyes were popping mad. The backyard filled with barking and shrieking and Lillian unleashed her demons. The truck pulled up in the driveway. Eric jumped out and ran towards her. Lillian swung the pole back for the last mighty whack and collected him in the gut, knocking him off his feet. He lay on the ground winded, his eyes as big as the teacups she read.

“I want a bloody washing machine.”’

How I could relate to her fury! Too many things going wrong when you’ve got too many people to look after and too many things to get done. Everyone’s elastic stretches a little too thin at times. It’s this honesty in her character’s reactions that Cheryl Adam has nailed to perfection. It’s one thing to throw issues at them and test their mettle, but it’s how you guide them through that makes a novel go from good to even better. Both Maggie and Lillian were forces to be reckoned with, even if at times they didn’t fully realise this. Their relationship with each other, which caught them both by surprise, was beautifully rendered. Lillian’s respect for Maggie was in sharp contrast to Eric’s dismissal. To Lillian, Maggie was her friend and protector; to Eric, Maggie was an inheritance waiting in the wings. Maggie knew this too, which is something that really tugged on my heartstrings. To know you are only valued for the money you’ll be leaving behind is a sad state of affairs and I must admit, I was amused by how Maggie used this knowledge to her advantage against Eric.

All in all, Lillian’s Eden was an entertaining read from start to finish and I recommend it highly. It’s a very frank novel that doesn’t sugar coat reality, but it’s also nicely balanced and doesn’t ever push itself too far or give up too soon. As far as debuts go, Cheryl Adam is off to an incredibly good start.

November 4, 2018

New Release Book Review: Where the River Runs by Fleur McDonald

About the Book:

In the tradition of the acclaimed Red Dust, Where the River Runs is a brilliantly told rural story of long-held family secrets by an author at the forefront of rural fiction, Fleur McDonald.

In the tradition of the acclaimed Red Dust, Where the River Runs is a brilliantly told rural story of long-held family secrets by an author at the forefront of rural fiction, Fleur McDonald.

Ten years ago, thirty-year-old Chelsea Taylor left the small country town of Barker and her family’s property to rise to the top as a concert pianist. With talent, ambition and a determination to show them all at home, Chelsea thought she had it made.

Yet here she was, back in Barker, with her four-year-old daughter, Aria, readying herself to face her father, Tom. The father who’d shouted down the phone ten years ago never to come home again.

With an uneasy truce developing, Chelsea and Aria settle into the rhythm of life on the land with Tom and Cal, the farmhand, who seems already to have judged Chelsea badly. Until a shocking discovery is made on the riverbed and Detective Dave Burrows, the local copper, has to tear back generations of family stories to reveal the secrets of the past.

Chelsea just wants a relationship with her dad but will he ever want that too? Or will his memory lapses mean they’ll never get that opportunity?

My Thoughts:

Where the River Runs was such an enjoyable read for me, the perfect blend of family drama and rural suspense. Fleur evokes the outback with such a vivid intensity – from the sounds and the smells to the dust sticking on her character’s feet – her scenes just crackle with atmosphere. Her knowledge of farming and life on the land is woven into the narrative in a such natural manner that one can’t help but appreciate the amount of life experience Fleur brings to each of her novels.

‘Everyone was only one phone call or police visit away from having their lives changed forever.’

Where the River runs is a story about grief and connection. Chelsea’s family is now half of what it used to be, with only herself and her father left. She travels home with her four year old daughter in search of a purpose, unsure on which direction she’s going to turn at this current crossroads of her life. There is a lot unsaid between Chelsea and her father, a lot of unresolved pain, and a load of misunderstanding. I loved how they unravelled this mess and picked it apart together, and of course, the sweetness of Aria did much to temper this fraught time.

Running alongside this family drama is an intriguing mystery, a skeleton found on the property, buried with an antique brooch and a box, the contents of which compound the mystery further. While the case is technically too cold for an official investigation, Dave Burrows feels an urge to satisfy his curiosity and provide some closure. I’m a fan of police procedurals and the way Dave and his wife Kim unpacked the details of the case to come to their conclusion greatly appealed to my interests. It just goes to show, no mystery is too old to solve if you dig deep enough.

Where the River Runs is a novel I highly recommend. Drama, mystery, family, friendship and forgiveness – this delightful cast of characters deliver a cracking story from start to finish.