Kathleen Rice Adams's Blog: Hole in the Web Gang, page 5

July 24, 2014

The Insanity Defense

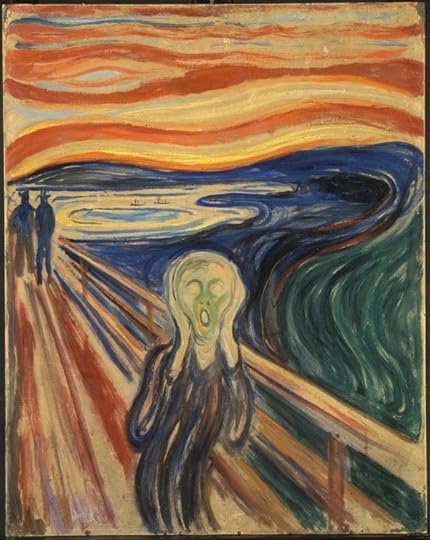

The Scream by Edvard Munch, 1910.

The Scream by Edvard Munch, 1910.Courtesy the Munch MuseumAuthors — especially those who write fiction — can be classified in any number of ways, but among my favorite categories are “uncannily brilliant,” “deeply devoted to substance abuse” and “just plain nuts.” The jury remains divided about which camp I fall into, but at last poll the Twelve Angry Critics leaned toward acquittal by virtue of insanity.

After much rumination, I’m inclined to agree. There’s plenty of evidence, after all. What else but insanity could explain the devolution of an otherwise relatively well-adjusted, reasonably intelligent, fairly articulate person into a raving lunatic who engages in lengthy conversations with imaginary friends — or worse, imaginary enemies?

No one warned me about this unnerving possibility when I signed on to write fiction. Shouldn’t there be a clause in my contract somewhere? I’d like to see a label like the ones pharmaceutical companies are required to include with medications: “WARNING: Possible side effects of the writing life may include spreading hips, estrangement from family and friends, deteriorating eyesight, insomnia, abbreviated attention span, inability to abandon lost causes, crabbiness, extended periods of depression punctuated by brief euphoria, loss of interest in the real world, self-doubt, a tendency to woolgather at odd moments, and talking to people who don’t exist.”

It’s that last one that plays most decisively into the insanity defense. (Wouldn’t we all be ecstatic if spreading hips did?)

Talking to characters is what a jury might consider the smoking gun — at least in my case. By “talking,” I don’t mean the occasional rhetorical “Hmm. What would you do if…?” I mean carrying on protracted give-and-take conversations. Actually, arguments might be a better term.

After nearly twenty-five years, my significant other has learned just to ignore the patently loony behavior. Crazy babbling and fixed stares no longer cause him to reach for the phone number of the nice men with white coats and butterfly nets. (Of course, this is the same man who frequently finds his life in jeopardy when he bursts into my writing space to tell me some horrendous, funny-only-to-men joke just as I’m about to craft the quintessential bit of dialog that will save the day, so his judgment is questionable, at best.)

But I digress (which ought to be another of those fully disclosed possible side effects). About those character interactions: Lately I’ve begun to feel like a temperamental director dealing with a herd of malcontents and unrepentant hams.

“Gah! Cut! Cut!” I yell, tearing out my hair by double handfuls.

“What? What did we do?”

“That’s a good question. Exactly what is it you thought you were doing there?”

“Improvising.”

“Improvising? You do realize there’s a script, right?”

“Yeah, but it’s all wrong right here. Nobody behaves like that. It’s bogus.”

“Bogus?” I shake my head and sigh with weariness that knows no bounds. “See — this is part of the problem: You’re from the 19th century; that word’s not in your vocabulary. Who gave you permission to take off on your own little tangent?”

Just about then, another character usually joins the fray. “You know, if I were the hero, I’d—”

“You’re not the hero,” I hiss, whirling on him. “If you’d spend as much time developing your own role as you do analyzing his, we’d all be the better for it.”

Depending on the character, at this point he’ll either sulk — meaning I have to expend valuable mental energy soothing his wounded feelings — or dive into a particularly vile tirade denouncing my writing ability. The latter does nothing to improve my relationship with a cast already doubting my fitness to be their leader.

Every so often, I find someone from a completely different project costuming himself or herself in the current project’s wardrobe and sneaking onto the set.

“You there — the Merry Man in the back. Aren’t you supposed to be on Stage 4 plotting with the rest of the gang in Last Train to Comanche Wells?”

“Uh… Well, yeah,” he’ll answer, shuffling his dusty cowboy boots. “But… Well, to tell you the truth, ma’am, they’re about to bore me to death over there. And it’s confusing — very confusing.”

“Incompetents and amateurs!” I explode. “Who’s in charge on Stage 4? I want him nuked.”

“Nuked?” (Misplaced Cowboy Guy only thought he was confused before.)

“Oh fer cryin’ out loud… Ask one of the Rigelians to explain it to you.”

About the time I begin chastising the hero from Chaste Through the Snow because he won’t stop pressing the heroine’s heaving bosom to his manly chest while for the umpteenth time uttering “Your eyes are like limpid sapphire pools” as she faints at the prospect of consummating their forbidden lust, I find myself consumed by heaving sobs of despair. It’s precisely at that moment the gaggle of slightly flighty but endearing, hard-as-nails southern belles escapes the pages of The Bougainvillea Ladies’ Luncheon Club and rushes to console me.

“Get away from me! I don’t want chocolate. Well, I do, but not right now.”

“Hon, what you need is a good roll in the sack with that hunk from Chaste.”

“You know, my deah mama always told me—”

“Oh for pity’s sake. Just gimme the damn chocolate and go back to fanning yourselves on the verandah, will you? Why can’t any of you behave?”

Half of them mutter “ingrate” under their breaths, and the others cluck knowingly and whisper, “This time the villain lives, but the writer is about to perish by her own hand.”

“I can hear you, you know.” Buncha know-it-all buttinskis. (I’m not above an occasional under-the-breath mutter myself.)

Perhaps insanity is a virtue after all. A rubber room looks more appealing all the time.

Published on July 24, 2014 22:00

July 19, 2014

Hubris Plus Inexperience Equals Fatal Irony

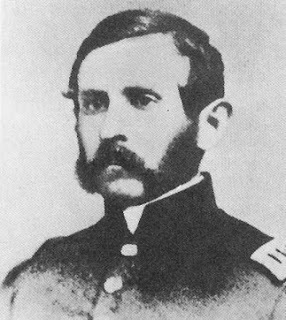

William J. Fetterman, Capt., U.S. Army“Give me eighty men and I’ll ride through the whole Sioux Nation.”

William J. Fetterman, Capt., U.S. Army“Give me eighty men and I’ll ride through the whole Sioux Nation.”So said Capt. William J. Fetterman in late 1866 as he assumed command of a U.S. Army detail tasked with defending a woodcutting expedition against Indians in the Dakota Territory. A fellow officer had declined the command after mounting, and failing to sustain, a similar effort two days earlier.

Fetterman overestimated his abilities and severely underestimated his opponent.

Born in Connecticut in 1833, William Judd Fetterman was the son of a career army officer. At the age of 28, in May 1861, he enlisted in the Union Army and immediately received a lieutenant’s commission. Twice brevetted for gallant conduct with the First Battalion of the 18th Infantry Regiment, Fetterman finished the Civil War wearing the brevet rank of lieutenant colonel of volunteers.

After the war, Fetterman elected to remain with the regular army as a captain. Initially assigned to Fort Laramie with the Second Battalion of the 18th Infantry, by November 1866 he found himself dispatched to Fort Phil Kearny, near present-day Sheridan, Wyoming. Since the post’s establishment five months earlier, the local population of about 400 soldiers and 300 civilian settlers and prospectors reportedly had suffered 50 raids by small bands of Sioux and Arapaho. In response, the fort’s commander, Col. Henry B. Carrington, adopted a defensive posture.

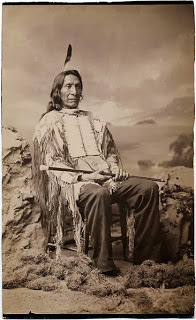

Red Cloud, ca. 1880

Red Cloud, ca. 1880(photo by John K. Hillers, courtesy Beinecke

Rare Book and Manuscript Library)Fetterman immediately joined a group of other junior officers in openly criticizing Carrington’s protocol. Although the 33-year-old captain lacked experience with the Indians, he didn’t hesitate to express contempt for the enemy. His distinguished war record lent credence to his argument: Since the Indian raiding parties consisted of only twenty to 100 mounted warriors, the army should run them to ground and teach them a lesson.

Fetterman’s voice and continuing raids eventually convinced the regimental commander at Fort Laramie to order Carrington to mount an offensive. Several minor scuffles, during which the soldiers proved largely ineffective due to disorganization and inexperience, merely bolstered the Indians’ confidence. Carrington himself had to be rescued after a force of about 100 Sioux surrounded him on a routine patrol. Even Fetterman admitted dealing with the “hostiles” demanded “the utmost caution.”

Jim Bridger, at the time a guide for Fort Phil Kearny, was less circumspect. He said the soldiers “don’t know anything about fighting Indians.”

On December 19, an army detail escorted a woodcutting party to a ridge only two miles from the fort before being turned back by an Indian attack. The next day, Fetterman and another captain proposed a full-fledged raid on a Lakota village about fifty miles distant. Carrington denied the request.

On the morning of December 21, with orders not to pursue “hostiles” beyond the two-mile point at which the previous patrol had met trouble, Fetterman, a force of 78 infantry and cavalry, and two civilian scouts escorted another expedition to cut lumber for firewood and building material. Within an hour of the group’s departure from the fort, the company encountered a small band of Oglala led by Crazy Horse. The Indians taunted the army patrol, which gave chase … beyond where they had been ordered not to go.

Fetterman and his men died here. The site

Fetterman and his men died here. The sitenow is known as Massacre Hill. (public domain photo)The great Sioux war leader Red Cloud and a force of about 2,300 Lakota, Arapaho, and Northern Cheyenne waited about one-half mile beyond the ridge. In less than 20 minutes, Fetterman and all 80 men under his command died. Most were scalped, beheaded, dismembered, disemboweled and/or emasculated.

The Indians suffered 63 casualties.

Among the Sioux and Cheyenne, the event is known as the Battle of the Hundred Slain or the Battle of 100 in the Hands. Whites know it better as the Fetterman Massacre, the U.S. Army’s worst defeat on the Great Plains until Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer made a similar mistake ten years later at Little Big Horn in Montana.

Whether Fetterman deliberately disobeyed Carrington’s orders or the commander massaged the truth in his report remains the subject of debate. Although officially absolved of blame in the disaster, Carrington spent the rest of his life a disgraced soldier. Fetterman, on the other hand, was honored as a hero: A fort constructed nearly 200 miles to the south was given his name seven months after his death. A monument dedicated in 1901 marks the spot where the officers and men fell.

Published on July 19, 2014 08:24

February 28, 2014

Taming the Nueces Strip

Texas always has been a rowdy place. In 1822, the original anglo settlers began invading what was then Mexico at the invitation of the Mexican government, which hoped American immigrants would do away with the out-of-control Comanches. Texans dispensed with the Comanches in the 1870s, foisting them off on Oklahoma, but long before that, the Texans ran off the Mexican government.

From 1836 to 1845, Texas looked something like the map above. The green parts became the Republic of Texas as the result of treaties signed by General Antonio Lopez de Santa Ana after Sam Houston and his ragtag-but-zealous army caught the general napping at San Jacinto. The treaties set the boundary between Texas and Mexico at the Rio Grande.

This caused a bit of a fuss in the Mexican capital, because Santa Ana did not possess the authority to dispose of large chunks of land with the swipe of a pen. Mexico eventually conceded Texas could have the dark-green part of the map, but the light-green part still belonged to Mexico. Arguments ensued.

While Texas and Mexico were carefully avoiding one another in the disputed territory, outlaws, rustlers, and other lawless types moved into the patch between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande. After all, no respectable outlaw ever lets a perfectly good blind spot on the law-enforcement radar go to waste. The area, 150 miles wide by about 400 miles long, came to be known as the Nueces Strip.

In 1845, the United States annexed all of the land claimed by Texas, including the disputed territory, and came to military blows with Mexico over the insult. By the time the two countries signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848 to settle once and for all who owned what — sort of — the lawless element was firmly entrenched in the strip of cactus and scrub between the Nueces and the Rio Grande. For nearly thirty years, brigands raised havoc — robbing, looting, raping, rustling, and killing — on both sides of the border before retreating to ranchos and other hideouts in no-man's land.

That began to change in 1875 when Texas Ranger Captain Leander McNelly was charged with bringing order to the Nueces Strip. Newly re-formed after being disbanded for about ten years during the Civil War and Reconstruction, the Rangers were determined to clean up the cesspool harboring notorious toughs like King Fisher and Juan Cortina. With a company of forty hand-picked men known as the Special Force, McNelly accomplished his task in two years … in some cases by behaving at least as badly as the outlaws. McNelly was known for brutal — sometimes downright illegal — tactics, including torturing information from some prisoners and hanging others. He and his men also made a number of unauthorized border crossings in pursuit of rustlers, nearly provoking international incidents.

Nevertheless, the “Little McNellys” got the job done. By the time McNelly was relieved of command in 1876, the Nueces Strip was a safer place. Though he remains controversial in some circles, the residents of South Texas raised funds and erected a monument in his honor.

The Nueces Strip plays a small role in “The Second-Best Ranger in Texas,” my contribution to Prairie Rose Publications’ new anthology, Hearts and Spurs. An excerpt of the story is here; the book is available in print and most e-formats at your favorite online bookstore.

Published on February 28, 2014 23:00

February 21, 2014

'The Most Dreaded Man North of the Rio Grande'

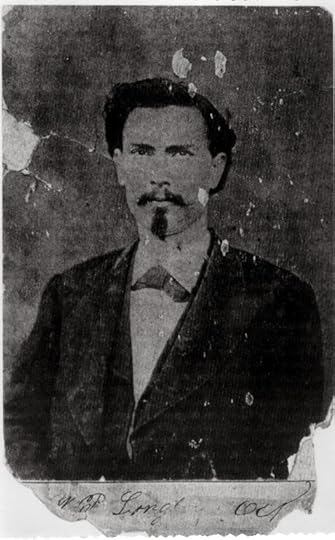

William Prescott "Wild Bill" LongleyThe years following the American Civil War were particularly difficult for Texas. The state fought reunification for five long years, insisting it had the right to become an independent republic once again. While the U.S. Army attempted to enforce martial law and the feds dragged the battered would-be empire before the Supreme Court, outlaws, freedmen, and carpetbaggers flooded the wild and wooly, wide-open spaces.

William Prescott "Wild Bill" LongleyThe years following the American Civil War were particularly difficult for Texas. The state fought reunification for five long years, insisting it had the right to become an independent republic once again. While the U.S. Army attempted to enforce martial law and the feds dragged the battered would-be empire before the Supreme Court, outlaws, freedmen, and carpetbaggers flooded the wild and wooly, wide-open spaces.The era produced some hard men. None were harder than Wild Bill Longley.

The sixth of ten children, William Prescott Longley was born October 6, 1851, on a farm along Mill Creek in Austin County, Texas. His father had fought with Sam Houston at San Jacinto. Little is known about Wild Bill’s youth until December 1868, when, at the age of seventeen, he killed his first man — an unarmed former slave he claimed was cursing his father.

The episode set Longley on a path he would follow for the rest of his life. After the black man’s murder, Longley and a cousin lit out for southern Texas. They spent 1869 robbing settlers, stealing horses, and killing freed slaves and Mexicans — men and women. A virulent racist with a hair-trigger temper and a fast gun hand, Longley quickly gained a reputation for picking fights with any whites he suspected of harboring Yankee sympathies or carpetbagging. In early 1870, the Union occupation force in Texas placed a $1,000 price on the cousins’ heads. Longley was not yet nineteen.

Not that he saw the bounty as a cause for concern. Standing a little over six feet tall with a lean, lithe build and a gaze described as fierce and penetrating, Longley “carried himself like a prince” and had “a set of teeth like pearls.” One newspaper writer called him “one of the handsomest men I have ever met” and “the model of the roving desperado of Texas.” The same writer called Longley “the most dreaded man north of the Rio Grande”: What his looks couldn’t get him, the brace of fourteen-inch, six-shot Dance .44 revolvers he carried could.

As news of the federal bounty spread, Longley and his cousin separated, and Longley took up with a cattle drive headed for Kansas. By May 1870 he was in Cheyenne, Wyoming; by June, he was in South Dakota, where for unknown reasons he enlisted in the army. Within two weeks he deserted. Capture, court-martial, and prison time followed, but evidently none of that make a big impression. After his release from the stockade, Longley was sent back to his unit. In May 1872, he deserted again and lit a shuck for Texas, gambling, scraping — and killing — along the way. Folks as far east as Missouri and Arkansas learned not to get in his way, not to disagree with him, and for heaven’s sake not to insult Texas. Longley was rumored to have shot white men over card games, Indians for target practice, and black folks just for fun.

By the time he killed another freedman in Bastrop County, Texas, in 1873, Longley was well beyond notorious. The murder jogged a local lawman’s memory about the federal bounty still outstanding from 1870. The sheriff arrested Longley, but when the army wasn’t quick to tender a reward, he let the surly gunman go.

Longley visited his family, worked a few odd jobs, and fended off several reckless sorts who hoped to make a name by besting a gunman known as one of the deadliest quick-draw artists in the West. In March 1875, he ambushed and killed a boyhood friend, Wilson Anderson, whom Longley’s family blamed for a relative’s death. That same year, Longley shot to death a hunting buddy with whom he’d had a fistfight. A few months later, in January 1876, he killed an outlaw when a quarrel-turned-ambush became a gunfight.

On the run, using at least eight different names to avoid the multiple rewards for his capture plastered all over East Texas, Longley hid out as a sharecropper on a preacher’s cotton farm, only to fall for a woman on whom his landlord’s nephew had staked a prior claim. Longley killed the nephew, then took off across the Sabine River into De Soto Parish, Louisiana. Reportedly turned in by someone he trusted, the law caught up with him on June 6, 1877, while he was hoeing a Louisiana cotton field, unarmed.

Though historians dispute the figures, Longley confessed to killing 32 men, six to ten of them white and one a Methodist minister. Later, he retracted that account and claimed eight kills. A court in Giddings, Texas, convicted him of only one murder, Anderson’s, and sentenced him to hang. While awaiting execution, “the worst man in Texas” wrote his memoirs, embraced Catholicism, and filed a wagonload of appeals. All of them were denied.

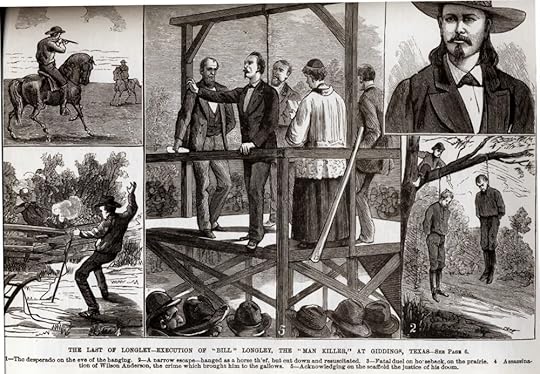

Illustration from National Police Gazette, Oct. 26, 1878Facing an ignominious end, Longley seems to have had a change of heart. On the day of his execution, October 11, 1878, the 27-year-old sang hymns and prayed in his cell before mounting the gallows “with a smile on his face and a lighted cigar in his mouth.” After the noose was placed around his neck, the man the Decatur [Illinois] Daily Review described as “the most atrocious criminal in the country” held up a hand and addressed the crowd.

Illustration from National Police Gazette, Oct. 26, 1878Facing an ignominious end, Longley seems to have had a change of heart. On the day of his execution, October 11, 1878, the 27-year-old sang hymns and prayed in his cell before mounting the gallows “with a smile on his face and a lighted cigar in his mouth.” After the noose was placed around his neck, the man the Decatur [Illinois] Daily Review described as “the most atrocious criminal in the country” held up a hand and addressed the crowd.“I see a good many enemies around me and mighty few friends,” Longley said. “I hope to God you will forgive me. I will you. I hate to die, of course; any man hates to die. But I have earned this by taking the lives of men who loved life as well as I do.

“If I have any friends here, I hope they will do nothing to avenge my death. If they want to help me, let them pray for me. I deserve this fate. It is a debt I owe for my wild, reckless life. When it is paid, it will be all over with. May God forgive me.”

Published on February 21, 2014 23:00

February 14, 2014

"Killer" Jim Miller: Husband, Father, Deacon ... and Assassin

Jim Miller, c. 1886“Let the record show I’ve killed 51 men. Let ’er rip.”

Jim Miller, c. 1886“Let the record show I’ve killed 51 men. Let ’er rip.”With those words, “Killer” Jim Miller, a noose around his neck, stepped off a box and into eternity. The lynch mob of 30 to 40 outraged citizens who had dragged him onto a makeshift gallows may have found it irritating Miller didn’t beg for his life like the three co-conspirators hanged with him.

Then again, perhaps they rejoiced at the professional assassin’s departure, no matter how defiant his attitude. By the time of his 1909 lynching in Ada, Oklahoma, Miller had earned a reputation as sneaky, deadly, and slippery when cornered by justice.

Born James Brown Miller on Oct. 25, 1866, in Van Buren, Arkansas, Miller arrived in Franklin, Texas, before his first birthday. Unsubstantiated, but persistent, rumors claim he was only 8 when he did away with a troublesome uncle and his grandparents. His first confirmed kill — and his first jaw-dropping escape from justice — happened a few months before Miller turned 18. After arguing with a brother-in-law he didn’t like, Miller shot the sleeping man to death. Had the subsequent sentence of life in prison stuck, Miller’s reign of terror might have ended right there — but a court overturned the murder conviction on a technicality.

Upon his release, Miller joined an outlaw gang that robbed stagecoaches and trains before turning his back on a life of crime and taking a succession of jobs in law enforcement. Reportedly, he even briefly served as a Texas Ranger. Based on his boasting, the badges may have been a calculated way for Miller to indulge his bloodlust behind a thin veneer of respectability.

And he was respectable, at least on the surface. A Bible-thumping Methodist who never missed a Sunday church service, Miller didn’t curse, drink, or smoke. In fact, his clean-cut appearance and apparent piety — bolstered by an ever-present black frockcoat that made him look a bit like a minister — earned Miller the nickname Deacon.

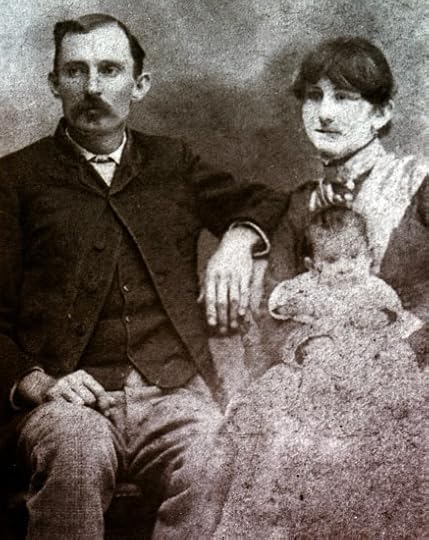

James Brown Miller and wife Sallie Clements Miller

James Brown Miller and wife Sallie Clements Millerwith one of their four children, 1890sMiller married John Wesley Hardin’s second cousin in 1888, fathered four children, and enjoyed a financially rewarding career selling real estate in Fort Worth. Reports indicate the family was considered a pillar of the community.

Behind the scenes, though, Miller advertised his services as a killer for hire, charging $150 a hit to “take care of” sheep ranchers, fence-stringing farmers, Mexicans, and almost anybody who got in his way. He specialized in doing away with lawmen, lawyers, and personal enemies, most often employing a shotgun from ambush under cover of darkness. Murder charges caught up with him several times, only to evaporate when witnesses for the prosecution disappeared.

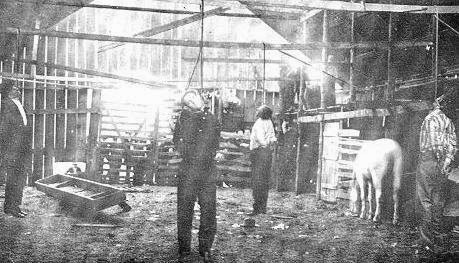

Frontier justice finally caught up with Miller on April 19, 1909. A cartel of ranchers outside Ada, Oklahoma, paid him $1,700 to silence a former deputy U.S. marshal who was a little too outspoken in his opposition to a shady land-acquisition scheme known as “Indian skinning.” Before the marshal-turned-rancher died, he identified his murderer. Miller and three of the conspirators were arrested, charged, and awaiting trial when an armed mob broke into the jail, overpowered the guards, and wrestled Miller and the others into an abandoned livery stable. Fearing Miller would slip a noose yet again, the mob hanged all four men from the rafters.

By the time of his death at age 42, Miller was known to have killed 14 men. His boast of 51 executions may have been accurate. A photo of the grisly scene inside the stable, right, became a must-have tourist souvenir. Miller’s is the body on the far left.

By the time of his death at age 42, Miller was known to have killed 14 men. His boast of 51 executions may have been accurate. A photo of the grisly scene inside the stable, right, became a must-have tourist souvenir. Miller’s is the body on the far left.Killer Jim Miller was buried in Fort Worth’s Oakwood Cemetery. At the time, one respectable citizen told the local newspaper, “He was just a killer — worst man I ever knew.”

Published on February 14, 2014 23:00

February 7, 2014

Cowboys and ... Nuns?

Sister Vincent Cottier, one of ten

Sister Vincent Cottier, one of tenSisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word

who died during the 1900 Storm.

(courtesy Sisters of Charity

of the Incarnate Word, Houston)When the sun rose on Sept. 9, 1900, the island city of Galveston, Texas, lay in ruins. What would come to be called The Great Storm, a hurricane of massive proportions, had roared ashore from the Gulf of Mexico overnight, sweeping “the Wall Street of the Southwest” from the face of the Earth.

Over the following weeks, rescuers pulled more than 6,000 bodies from the rubble, piled the remains on the beach, and burned them to prevent an outbreak of disease. Among the departed, discovered amid the wreckage of St. Mary’s Orphan Asylum, were the bodies of ninety children ages 2 to 13 and all ten Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word. In a valiant, yet ultimately futile, attempt to save the children from floodwaters that rose to twenty feet above sea level, each sister bound six to eight orphans to her waist with a length of clothesline. The lines tangled in debris as the water destroyed the only home some of the children had ever known.

All that survived of the orphanage were the three oldest boys and an old French seafaring hymn: “Queen of the Waves.” To this day, every Sept. 8, the Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word worldwide sing the hymn in honor of the sisters and orphans who died in what remains the deadliest natural disaster ever to strike U.S. soil.

Two postulants from the Congregation of the Incarnate Word

Two postulants from the Congregation of the Incarnate Word in San Antonio, Texas, ca. 1890. (courtesy University of

Texas at San Antonio’s Institute of Texan Cultures)Established in Galveston in 1866 by three Catholic sisters from France, the Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word is a congregation of women religious. Not technically nuns because they take perpetual simple vows instead of perpetual solemn vows and work among secular society instead of living in seclusion behind cloistered walls, they nevertheless wear habits and bear the title “Sister.” Today the original congregation is based in Houston, but back then Galveston seemed an ideal spot for the women to build a convent, an orphanage, and a hospital. By 1869, they had founded a second congregation in San Antonio. From there, the sisters expanded to other cities in Texas, including Amarillo, and even farther west, all the way to California. In 2013, the sisters operated missions in Ireland, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Kenya in addition to the United States.

Sister Cleophas Hurst, first administrator

Sister Cleophas Hurst, first administratorof St. Anthony’s Sanitarium in Amarillo,

Texas, 1901. (courtesy Sisters of Charity

of the Incarnate Word, San Antonio)Armed with faith instead of guns, the sisters did their part to civilize Texas’s notoriously wild frontier. They did not do so without significant hardship. Catholics often were not well-tolerated in 19th Century America, although in Galveston the sisters were admired and even loved for their industry and benevolence. That benevolence led to the deaths of two of the original three Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word, who perished during Galveston’s yellow fever epidemic of 1867.

As a Galvestonian, the history of the island city and its diverse people fascinates me. I continue to hope for inspiration that will grow into a story set here, where the past overflows with tales of adventure dating back well before the pirate Jean Lafitte built the fortified mansion Maison Rouge on Galveston in 1815. In the meantime, the Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word provided the inspiration for the heroine in a short story that appears in Prairie Rose Publications’ new western historical anthology, Hearts and Spurs. The collection of short stories by Linda Broday, Livia J. Washburn, Cheryl Pierson, Sarah J. McNeal, Tanya Hanson, Jacquie Rogers, Tracy Garrett, Phyliss Miranda, and me, is available at your favorite online bookstore in print and most e-formats.

“The Second-Best Ranger in Texas”

“The Second-Best Ranger in Texas”A washed-up Texas Ranger. A failed nun with a violent past. A love that will redeem them both.

His partner’s grisly death destroyed Texas Ranger Quinn Barclay. Cashiered for drunkenness and refusal to follow orders, he sets out to fulfill his partner’s dying request, armed only with a saloon girl’s name.

Sister María Tomás thought she wanted to become a nun, but five years as a postulant have convinced her childhood dreams aren’t always meant to be. At last ready to relinquish the temporary vows she never should have made, she begs the only man she trusts to collect her from a mission in the middle of nowhere.

When the ex-Ranger’s quest collides with the ex-nun’s plea in a burned-out border town, unexpected love blooms among shared memories of the dead man who was a brother to them both.

Too bad he was also the only man who could have warned them about the carnage to come.

(Read an excerpt.)

(This post originally appeared at Sweethearts of the West, where I blog on the 12th of each month.)

Published on February 07, 2014 23:00

January 31, 2014

Kitty LeRoy: Beloved Tramp

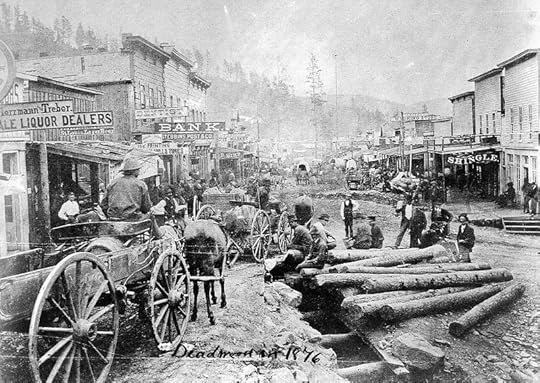

Deadwood, SD, 1876

Deadwood, SD, 1876(National Archives and Records Administration)Some historical episodes in the Old West read like adventures. Some read like tragedies. Some read like romances.

A few real-life characters — like Kitty LeRoy — managed to combine all three.

“…Kitty LeRoy was what a real man would call a starry beauty,” one of her contemporaries noted in a book with a ridiculously long title*. “Her brow was low and her brown hair thick and curling; she had five husbands, seven revolvers, a dozen bowie-knives and always went armed to the teeth, which latter were like pearls set in coral.”

Though no photos of her are known to exist, from all reports LeRoy was a stunning beauty with a sparkling personality that had men — including both notorious outlaws and iconic lawmen — throwing themselves at her feet. She was proficient in the arts of flirtation and seduction, and she didn’t hesitate to employ her feminine wiles to get what she wanted.

Often, what she wanted was the pot in a game of chance. One of the most accomplished poker players of her time, LeRoy spent much of her short life in gambling establishments. Eventually, she opened her own in one of the most notorious dens of iniquity the West has ever known: Deadwood, South Dakota. With LeRoy and the spectacular diamonds at her ears, neck, wrists, and fingers glittering brightly enough to blind her customers every night, it’s no wonder the Mint Gambling Saloon prospered.

And, with her reputation as an expert markswoman, there was very little trouble … at least at the tables.

LeRoy was born in 1850, although no one is sure where. Some say Texas; others, Michigan. One thing is certain: By the age of ten, she was performing as a dancer on the stage. Working in dancehalls and saloons, she either picked up or augmented an innate ability to manipulate, along with gambling and weaponry skills that would serve her well for most of her life. At fifteen she married her first husband because, according to legend, he was the only man in Bay City, Michigan, who would let her shoot apples off his head while she galloped past on horseback.

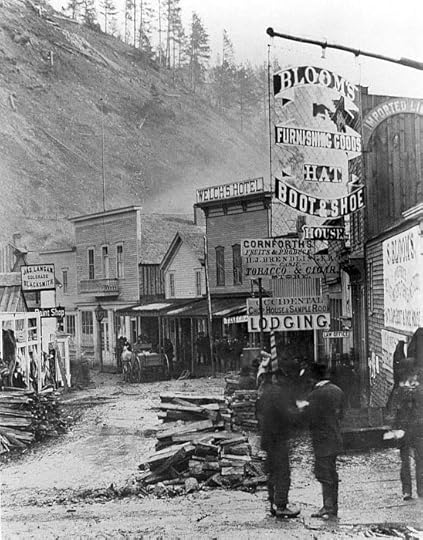

Deadwood, SD, ca. 1878-80A long attention span apparently was not among the skills LeRoy cultivated. Shortly after her marriage, she left her husband and infant son behind and headed for Texas. By the age of twenty, she had reached the pinnacle of popularity at Johnny Thompson’s Variety Theatre in Dallas, only to leave entertaining behind, too.

Deadwood, SD, ca. 1878-80A long attention span apparently was not among the skills LeRoy cultivated. Shortly after her marriage, she left her husband and infant son behind and headed for Texas. By the age of twenty, she had reached the pinnacle of popularity at Johnny Thompson’s Variety Theatre in Dallas, only to leave entertaining behind, too.Instead, she tried her hand as a faro dealer. Ah, now there was a career that suited. Excitement, money, men … and extravagant costumes. Players never knew what character they would face until she appeared. A man? A sophisticate? A gypsy?

Texas soon bored LeRoy, too, but no matter. With a new saloonkeeper husband in tow, she headed for San Francisco — only to discover the streets were not paved with gold, as she had heard. While muddling through that dilemma, she somehow misplaced husband number two, which undoubtedly made it easier for her to engage in the sorts of promiscuous shenanigans for which she rapidly gained a reputation.

Although the reputation didn’t hurt her at the gaming tables, it did create a certain amount of unwanted attention. One too-ardent admirer persisted to such an extent that LeRoy challenged him to a duel. The man demurred, reportedly not wishing to take advantage of a woman. Never one to let a little thing like gender stand in her way, LeRoy changed into men’s clothes, returned, and challenged her suitor again. When he refused to draw a second time, she shot him anyway. Then, reportedly overcome with guilt, she called a minister and married husband number three as he was breathing his last.

Now a widow, LeRoy hopped a wagon train with Wild Bill Hickock and Calamity Jane and headed for the thriving boomtown of Deadwood. They arrived in July 1876, and LeRoy became an instant success by entertaining adoring prospectors nightly at the notorious Gem Theatre. Within a few months, she had earned enough money to open her own establishment: the Mint. There, she met and married husband number four, a German who had struck it rich in Black Hills gold. When the prospector’s fortune ran out, so did LeRoy’s interest. She hit him over the head with a bottle and threw him out.

Meanwhile, thanks to LeRoy’s mystique — and allegedly, to no little fooling around with the customers — the Mint became a thriving operation. LeRoy reportedly “entertained” legendary characters as diverse as Hickock and Sam Bass. But it was 35-year-old card shark Samuel R. Curley who finally claimed her heart. Curley, besotted himself, became husband number five on June 11, 1877.

Shortly thereafter, Curley learned LeRoy hadn’t divorced her first husband. The bigamy realization, combined with rumors about LeRoy’s continued promiscuity, proved too much for the usually peaceful gambler. He stormed out of the Mint and didn’t stop until he reached Denver, Colorado.

Folks who knew LeRoy said she changed after Curley’s departure. Despite nights during which she raked in as much as $8,000 on a single turn of the cards, she grew cold and suspicious.

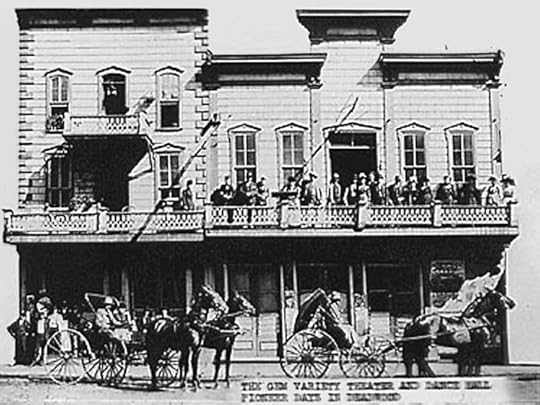

Gem Theatre, Deadwood, SD, ca. 1878Her grief seemed to dissipate a bit when an old lover showed up in Deadwood. LeRoy rented rooms above the Lone Star Saloon, and the two moved in together.

Gem Theatre, Deadwood, SD, ca. 1878Her grief seemed to dissipate a bit when an old lover showed up in Deadwood. LeRoy rented rooms above the Lone Star Saloon, and the two moved in together.By then, Curley was dealing faro in a posh Cheyenne, Wyoming, saloon. Acquaintances called him miserable. When word of LeRoy’s new relationship reached him, he flew into a jealous rage. Determined to confront his wife and her lover, he returned to Deadwood December 6, 1877. When the lover refused to see him, Curley told a Lone Star employee he’d kill them both.

LeRoy, reportedly still pining for her husband despite her new affair, agreed to meet Curley in her rooms at the Lone Star. Not long after she ascended the stairs, patrons below reported hearing a scream and two gunshots.

The following day, the Black Hills Daily Times reported the gruesome scene: LeRoy lay on her back, eyes closed. Except for the bullet hole in her chest, the 27-year-old looked as though she were asleep. Curley lay face down, his skull destroyed by a bullet from the Smith & Wesson still gripped in his right hand.

“Suspended upon the wall, a pretty picture of Kitty, taken when the bloom and vigor of youth gazed down upon the tenements of clay, as if to enable the visitor to contrast a happy past with a most wretched present,” the newspaper report stated. “The pool of blood rested upon the floor; blood stains were upon the door and walls….”

An understated funeral took place in the room where Curley killed his wife and then took his own life. Their caskets were buried in the same grave in the city’s Ingleside Cemetery and later moved to an unmarked plot in the more famous Mount Moriah.

The happiness the couple could not find together in life, apparently they did in death. Within a month of the funeral, Lone Star patrons began to report seeing apparitions “recline in a loving embrace and finally melt away in the shadows of the night.” The sightings became so frequent, the editor of the Black Hills Daily Times investigated the matter himself. His report appeared in the paper February 28, 1878:

…[W]e simply give the following, as it appeared to us, and leave the reader to draw their own conclusions as to the phenomena witnessed by ourselves and many others. It is an oft repeated tale, but one which in this case is lent more than ordinary interest by the tragic events surrounding the actors.

To tell our tale briefly and simply, is to repeat a story old and well known — the reappearance, in spirit form, of departed humanity. In this case it is the shadow of a woman, comely, if not beautiful, and always following her footsteps, the tread and form of the man who was the cause of their double death. In the still watches of the night, the double phantoms are seen to tread the stairs where once they reclined in the flesh and linger o’er places where once they reclined in loving embrace, and finally to melt away in the shadows of the night as peacefully as their bodies’ souls seem to have done when the fatal bullets brought death and the grave to each.

Whatever may have been the vices and virtues of the ill-starred and ill-mated couple, we trust their spirits may find a happier camping ground than the hills and gulches of the Black Hills, and that tho’ infelicity reigned with them here, happiness may blossom in a fairer climate.

Sources:

* Life and Adventures of SAM BASS, the Notorious Union Pacific and Texas

Train Robber, Together with a Graphic Account of His Capture and Death, Sketch of the Members of his Band, with Thrilling Pen Pictures of their Many Bold and Desperate Deeds, and the Capture and Death of Collins, Berry, Barnes, and Arkansas Johnson (W.L. Hall & Company, 1878)

The Lady Was a Gambler: True Stories of Notorious Women of the Old West by Chris Enss (TwoDot, October 2007)

Women of the Western Frontier in Fact, Fiction and Film by Ronald W. Lackmann (McFarland & Company Inc., January 1997)

(This post originally appeared at Sweethearts of the West, where I blog on the 12th of each month.)

Published on January 31, 2014 23:00

January 25, 2014

Is that a Gun in Your Pocket, or...?

Life is full of little ironies. Every so often, a big irony jumps up and literally grabs a person by the privates. Just ask late Texas lawman Cap Light.

Life is full of little ironies. Every so often, a big irony jumps up and literally grabs a person by the privates. Just ask late Texas lawman Cap Light.Many of the details about William Sidney “Cap” Light’s life have been obscured by the sands of time. His exact birth date is unknown, though it’s said he was born in late 1863 or early 1864 in Belton, Texas. No photographs of him are known to exist, although there seem to be plenty of his infamous brother-in-law, the confidence man and gold-rush crime boss Soapy Smith. Several of Light’s confirmed line-of-duty kills are mired in controversy, and rumors persist about his involvement in at least one out-and-out murder. Even the branches of his family tree are a mite tangled, considering the 1900 census credited Light with fathering a daughter born six years after his death.

What seems pretty clear, however, is that Light survived what should have been a fatal gunshot wound to the head only to kill himself accidentally about a year later.

Light probably lived an ordinary townie childhood. The son of a merchant couple who migrated to Texas from Tennessee, he followed an elder brother into the barbering profession before seeking and receiving a deputy city marshal’s commission in Belton at the age of 20. Almost immediately — on March 24, 1884 — he rode with the posse that tracked down and killed a local desperado. Belton hailed the young lawman as a hero.

For five years, Light reportedly served the law in an exemplary, and uneventful, fashion. Then, in 1889, things began to change.

In August, while assisting the marshal of nearby Temple, Texas, Light shot a prisoner he was escorting to jail. Ed Cooley tried to escape, Light said. Later that fall, after resigning the Belton job to become deputy marshal in Temple, Light shot and killed Sam Hasley, a deputy sheriff with a reputation for troublemaking. Hasley, drunk and raising a ruckus, ignored Light’s order to go home. Instead, he rode his horse onto the boardwalk and reached for his gun. Light responded with quick, accurate, and deadly force.

The following March, Light cemented his reputation as a fast and deadly gunman when he killed another drunk inside Temple’s Cotton Exchange Saloon. According to the local newspaper’s account, Felix Morales died “with his pistol in one hand and a beer glass in the other.”

Light’s growing reputation as a no-nonsense straight-shooter served Temple so well that in 1891, the city cut its budget by discontinuing the deputy marshal’s position. Unemployed and with a wife and two toddlers to support, Light accepted his brother-in-law’s offer of a job in Denver, Colorado. By then, Jeff “Soapy” Smith was firmly in control of Denver’s underworld. After the Glasson Detective Agency allegedly leaned on one of Smith’s young female friends, Light took part in a pistol-wielding raid meant to convince the detectives that investigating Smith might not be healthy.

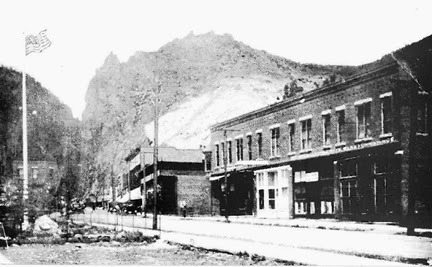

Main Street, Creede, Colorado, 1892In early 1892, Smith moved his criminal enterprise to the nearby boomtown of Creede, Colorado (left), where he reportedly exerted his considerable influence to have Light appointed deputy marshal. At a little after 4 o’clock in the morning on March 31, Light confronted yet another drunk in a saloon. Both men drew their weapons. When the hail of gunfire ceased, Light remained standing, unscathed. Gambler and gunfighter William “Reddy” McCann, on the other hand, sprawled on the floor, his body riddled with five of Light’s bullets.

Main Street, Creede, Colorado, 1892In early 1892, Smith moved his criminal enterprise to the nearby boomtown of Creede, Colorado (left), where he reportedly exerted his considerable influence to have Light appointed deputy marshal. At a little after 4 o’clock in the morning on March 31, Light confronted yet another drunk in a saloon. Both men drew their weapons. When the hail of gunfire ceased, Light remained standing, unscathed. Gambler and gunfighter William “Reddy” McCann, on the other hand, sprawled on the floor, his body riddled with five of Light’s bullets.Despite witness testimony stating McCann had emptied his revolver shooting at streetlights immediately before bracing the deputy marshal, a coroner’s inquest ruled the shooting self-defense. The close call rattled Light, though. He took his family and returned to Temple, where in June 1892 he applied for a detective’s job with the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe Railroad. His application was rejected — possibly because his association with Smith and lingering rumors about the McCann incident overshadowed the stellar reputation he had earned early in his career. According to a period report in the Rocky Mountain News, “Light’s name had become a household word, and for years he was alluded to as a good sort of a fellow ― to get away from. He was mixed up in many fights, and after a time the ‘respect’ he had commanded with the aid of a six-shooter began to fade away. It was recalled that all his killings and shooting scrapes occurred when the other man’s gun was elsewhere, or in other words, when the victim was powerless to return blow for blow and shot for shot.”

With his life apparently on the skids, Light developed a reputation of his own for drunken belligerence. With no other options, he returned to barbering in Temple until, during one drinking binge in late 1892, he pistol-whipped the railroad’s chief detective — the man Light blamed for the end of his law-enforcement career. During Light’s trial for assault, the detective, T.J. Coggins, rose from his seat in the courtroom, pulled his pistol, and fired three .44-caliber rounds into Light’s face and neck. Although doctors expected the former lawman to die of what they called mortal injuries, Light fully recovered. Adding insult to injury, Coggins never faced trial.

It’s unclear how well Light adapted to circumstances after the Coggins episode or why he was traveling by train a year later. What is clear is that his life came to a sudden, ironic end on Christmas Eve 1893. As the Missouri, Kansas & Texas neared the Temple station, Light accidentally discharged a revolver he carried in his pocket. The bullet severed the femoral artery in his groin, and he bled to death within minutes. He was 30 years old.

In a span of fewer than ten years, Light’s brief candle flickered, blazed, and then burned out. Though once hailed as a heroic defender of law and order on the reckless frontier, not everyone was sorry to see him go. An unflattering obituary published in the Dec. 27, 1893, edition of the Rocky Mountain News called him "a bad man from Texas." Beneath the headline “Light’s Ready Gun. It Took Five Lives and then Killed Him,” the report noted “‘Cap’ Light of Belton, Texas, shot himself by accident the other day ... thus [removing] one who has done more than his share in earning for the West the appellation of ‘wild and woolly.’”

(This post originally appeared at Sweethearts of the West, where I blog on the 12th of each month.)

Published on January 25, 2014 08:42

January 18, 2014

The Outlaw Gang

Many writers mention how a Muse controls their life. My life? Controlled by a pack of tiny terrorists. These are they:

Dog: Don't let that innocent expression fool you. He's pure trouble.

Dog: Don't let that innocent expression fool you. He's pure trouble. Underdog: Endlessly clueless, but very, very sweet.

Underdog: Endlessly clueless, but very, very sweet.

Li'l Ol' Biddy: Eldest and by far the toughest of the gang, she rules the boys with an iron paw.

Li'l Ol' Biddy: Eldest and by far the toughest of the gang, she rules the boys with an iron paw.

Published on January 18, 2014 07:56

January 13, 2014

Hearts and Spurs

The second anthology from Prairie Rose Publications released today! Am I excited? You betcha! This is the second Prairie Rose anthology to which I've been privileged to contribute, and it's even better than the first. (More about the first, Wishing for a Cowboy — including an excerpt from my story "Peaches" — is here.) Hearts and Spurs is a Valentine-themed collection of nine romantic western stories by nine veteran authors.

The second anthology from Prairie Rose Publications released today! Am I excited? You betcha! This is the second Prairie Rose anthology to which I've been privileged to contribute, and it's even better than the first. (More about the first, Wishing for a Cowboy — including an excerpt from my story "Peaches" — is here.) Hearts and Spurs is a Valentine-themed collection of nine romantic western stories by nine veteran authors.The e-book version is available at most online bookstores (Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Smashwords, etc.); Amazon also stocks the paperback.

Here's a sneak peek at the warm, sometimes humorous, love stories in Hearts and Spurs.

“The Widow's Heart” by Linda Broday

Skye O’Rourke thinks her imagination is playing tricks on her when she sees a man emerge from the shimmering desert heat. No one would willingly take a stroll under the scorching sun with a saddle slung on his back. She’s shocked to discover it’s Cade Coltrain, a man she once gave her heart to only to have him give it back.

Can she trust him not to abandon her this time? Yet, trusting each other is the only way they can survive. And love might just save them if they believe…

“Guarding Her Heart” by Livia J. Washburn

Julia Courtland was on her way west to marry a man she had never met. Henry Everett, the marshal of Flat Rock, Texas, was the grandson of her uncle's best friend. It seemed like a good match for both of them, and the wedding was scheduled to take place on Valentine's Day.

Grant Stafford thought the young woman who got on the stagecoach at Buffalo Springs was the prettiest thing he had seen in a long time. She wasn't too friendly, mind you, but she was sure easy on the eyes. Not that Grant had time to worry much about such things. He was the shotgun guard on this run, but more than that, he was an undercover Texas Ranger on the trail of the vicious outlaw gang responsible for a string of stagecoach robberies.

Fate threw Julia Courtland and Grant Stafford together on a cold February day in West Texas, but it also threw deadly obstacles in their path. A runaway team, a terrible crash, and bullets flying through the air threaten to steal not only their lives but also any chance they have for happiness. If they're going to survive, they will have to learn to trust each other...and maybe steal their hearts back from fate.

“Found Hearts” by Cheryl Pierson

Southern belle Evie Fremont has lost everything—except hope. When she answers an advertisement for marriage to Alex Cameron who lives in the wilds of Indian Territory, she has few illusions that he could be a man she might fall in love with—especially as his secrets begin to unfold.

Ex-Confederate soldier Alex Cameron needs a mother for his two young half-Cherokee sons more than he needs a wife—or so he tells himself. But when his past threatens his future on his wedding day, he and Evie are both forced to acknowledge their new love has come to stay—along with their FOUND HEARTS.

“Open Hearts” by Tanya Hanson

To honor her brother’s last request, Barbara Audiss takes on his identity. Letting loose her secret will land get her arrested. But keeping it prevents her from giving her heart to handsome sheriff Keith Rakestraw.

Furious at “Judge Audiss’s” latest verdict, Keith discovers she’s a fake and consequences seem easy: toss her in jail. Instead, he finds himself eager to give her his heart.

“Hollow Heart” by Sarah J. McNeal

Madeline Andrews is a grown up orphan. Sam Wilding made her feel part of his life, his family and swore he’d come home to her when the war ended, but he didn’t return. With the Valentine’s Ball just days away, the Wildings encourage Madeline to move forward with her life and open her heart to the possibilities. But Madeline is lost in old love letters and can’t seem to let go.

“A Flare of the Heart” by Jacquie Rogers

Celia Valentine Yancey has no illusions she’ll ever enjoy wedded bliss, so chooses marriage over spinsterhood even if she has to marry a man her father picked. On the way to meet her groom, she endures armed robbery, a stagecoach wreck, a dozen hungry baby pigs—and an incorrigible farmer. Ross Flaherty retired from bounty hunting to become a farmer but now Celia has brought his worst fear to his door—in more ways than one. A ferocious wolf-dog and a dozen piglets are no match for this determined lady. Which is more dangerous—the Sully Gang or Miss Celia Yancey?

“Coming Home” by Tracy Garrett

Sometimes it takes two to make dreams come true.

When a man who believes he’ll never have a home and family…

Former U.S. Marshal Jericho Hawken should have been shepherding a wagon train to new territory, but he unwillingly left them vulnerable to a vicious raider. The murder of the settlers he was supposed to be guarding is the hardest thing he’s ever had to face…until he meets the sister of one of the settlers.

…finds a woman who has lost everything…

Instead of a joyous reunion with her brother, Maryland Henry has come to River’s Bend to take responsibility for her three orphaned nieces. Fired from her teaching position and with no other family on whom to rely, Mary believes Jericho Hawken is responsible for all her woes. Or is he what she’s been searching for all along?

It takes a lot of forgiveness and a few fireworks to realize that together their dreams can come true.

“Tumbleweeds and Valentines” by Phyliss Miranda

When Amanda Love finds a tumbleweed lodged against her fence with an invitation to a Valentine Day dance stuck to it she thinks someone must be playing a joke. No one would invite her. No one ever had. Besides, she has no time for such things. She has a candy store to run. Curiosity gets the best of her though. Finding her name scrawled on it as bold as can be sends ripples of surprise through her. As she embarks on a quest to find the sender’s identity, she examines herself and the secret dream she harbors of having a husband and children.

Maybe, just maybe, someone had seen the yearning in her heart. But who?

"The Second-Best Ranger in Texas" by Kathleen Rice Adams

His partner’s grisly death destroyed Texas Ranger Quinn Barclay. Cashiered for drunkenness and refusal to follow orders, he sets out to fulfill his partner’s dying request, armed only with a saloon girl’s name.

Sister María Tomás thought she wanted to become a nun, but five years as a postulant have convinced her childhood dreams aren’t always meant to be. At last ready to relinquish the temporary vows she never should have made, she begs the only man she trusts to collect her from a mission in the middle of nowhere.

When the ex-Ranger’s quest collides with the ex-nun’s plea in a burned-out border town, unexpected love blooms among shared memories of the dead man who was a brother to them both.

Too bad he was also the only man who could have warned them about the carnage to come. (Read an excerpt.)

Available online here: Kindle • Nook • Other e-formats • Paperback

Published on January 13, 2014 17:11

Hole in the Web Gang

Western history, tidbits, trivia, and other fun stuff.

- Kathleen Rice Adams's profile

- 18 followers