Kathleen Rice Adams's Blog: Hole in the Web Gang, page 4

October 10, 2014

'Remember Goliad!'

Presidio la Bahía today. In 1836,

Presidio la Bahía today. In 1836,the Texians who died there called it Fort Defiance.Though the most infamous by far, the Alamo wasn’t the only massacre during the Texas Revolution.

On March 19 and 20, 1836, two weeks after the Alamo fell, Col. James Fannin and a garrison of about 300 Texians engaged a Mexican force more than three times as large on the banks of Coleto Creek outside Goliad, Texas. Without food or water and running low on ammunition, unwilling to flee and leave the roughly one-third of of their comrades who were wounded or dead, Fannin and his troops surrendered.

Led to believe they were prisoners of war and would be allowed to return to their homes within a couple of weeks, the Texians were marched back to Goliad, where they were imprisoned in their former fortress, Presidio Nuestra Señora de Loreto de la Bahía, which they had christened Fort Defiance. Unbeknownst to the Texians, on December 30 of the previous year, the Mexican congress had decreed any armed insurgents who were captured were to be executed as pirates.

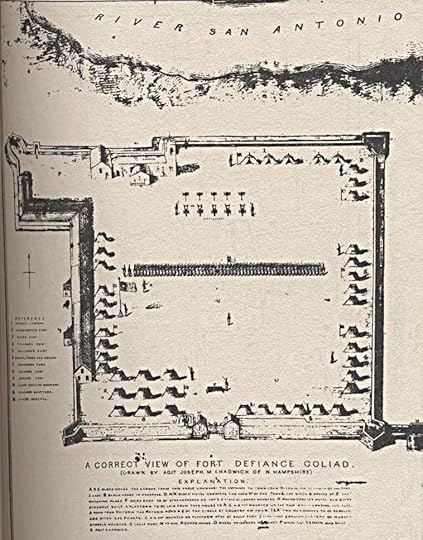

Diagram of Fort Defiance by Joseph M. Chadwick,

Diagram of Fort Defiance by Joseph M. Chadwick,March 1836. Tents mark the location where various

companies camped. Chadwick was among those

executed. The U.S. federal government reprinted

the map in 1856 with the locations of Fannin’s

and Chadwick’s executions marked.On Palm Sunday, March 27, acting on orders from Mexican President Gen. Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, Col. José Nicolás de la Portilla separated into three columns the 303 Texians who were well enough to walk. Sandwiched between two rows of Mexican soldiers, the men were marched out of Fort Defiance along three roads. There, they were shot point-blank. Any who survived the fusillade were clubbed or stabbed to death. Twenty-eight feigned death and escaped.

Inside the fort, the 67 who were wounded too badly to march, including Fannin, were executed by firing squad.

Fannin, 32, was the last to die, after watching the executions of the men who served under him. As the commandant of the garrison, he was allowed a last request. He asked three things: that his possessions be given to his family; that he be shot in the heart, not the head; and that he be given a Christian burial.

The soldiers took his possessions, shot him in the face, and burned his body along with the bodies of the other 341 executed prisoners.

The Goliad massacre further galvanized the Texians. Three weeks later, on April 21 — shouting the battle cry “Remember the Alamo! Remember Goliad!” — the ragtag Texian army, under the command of Gen. Sam Houston, captured Santa Anna at the Battle of San Jacinto. Disorganized, demoralized, and leaderless, the Mexican army retreated.

Presidio la Bahía chapel, date unknown.

Presidio la Bahía chapel, date unknown.Fannin was executed in the courtyard.Urged to execute Santa Anna as revenge for the depredations at the Alamo and Goliad, Houston decided to let el presidente live. On May 14, Santa Anna ceded Texas to the Texians in the Treaties of Velasco.

Though Goliad was one of the seminal events of the Texas Revolution, more than 100 years would pass before the State of Texas erected a monument to the men who died. In 1936, as part of the Texas Centennial celebration, the state earmarked funds for a memorial. The monument was built over the mass grave of Fannin and his men, and dedicated in 1938. The pink granite marker, inscribed with the names of the executed Texians and their comrades who died during the Battle of Coleto, bears the sculpted image of the Goddess of Liberty lifting a fallen soldier in chains.

Though “Remember the Alamo!” is famous around the world, those with the blood of Texas in their veins still recite, with reverence, the whole battle cry: “Remember the Alamo! Remember Goliad!”

This Monument marks the common grave where the charred remains

This Monument marks the common grave where the charred remainsof the 342 Texians massacred at Goliad are buried

Published on October 10, 2014 22:00

October 3, 2014

The Pie Who Loved Me

Writers play all sorts of funny games with ourselves when a story isn’t moving along as smoothly as we’d like. Some swear taking a walk energizes the body and mind. Some swear a household cleaning binge sweeps the cobwebs from dusty creativity. (My other half will testify I am not one of those crazy people.) Some swear music is a foolproof cure.

Some just swear.

Me? I usually rely on a long shower to get my sluggish brain back on track. Standing under a stream of water never fails to jar things loose in my head. As often as the gears grind to a halt in there, I may be the cleanest person I know.

One can only take so many showers, though, before she begins to resemble a prune. At my age, I don’t need any help with that.

Fortunately, I have a second weapon in my brain-jumpstarting arsenal: baking. Bread, cakes, pies, cookies… There’s something immensely gratifying about creating a work of art from ingredients that don’t fight you every step of the way. I’ll admit flour sometimes can be a challenge, prone to flying all over the place as it is, but as a general rule, sugar, butter, eggs, milk, and other components behave and keep the backtalk to a minimum.

Fortunately, I have a second weapon in my brain-jumpstarting arsenal: baking. Bread, cakes, pies, cookies… There’s something immensely gratifying about creating a work of art from ingredients that don’t fight you every step of the way. I’ll admit flour sometimes can be a challenge, prone to flying all over the place as it is, but as a general rule, sugar, butter, eggs, milk, and other components behave and keep the backtalk to a minimum.Compared to writing, baking is a cinch. If nothing else, it bolsters my confidence in my ability to outmaneuver inanimate objects. Mostly.

I’m an adventurous baker — a trait I’m certain I inherited from my late grandmother. Granny was justifiably famous for her ability to whip up a mess of mouthwatering goodness from whatever she had in the pantry. The tomato cake episode continues to live in infamy, but for the most part, whatever Granny baked was a monument to innovation and deliciousness.

I felt Granny peeking over my shoulder a few weeks ago when I was overcome by a desperate urge to exert some small measure of control over my environment. A quick glance in the pantry nearly destroyed my ambition. No flour. No sugar. None of the usual baking suspects. My worst nightmare stared me in the face: I was on the verge of outdoing the tomato cake, possibly with green beans.

Fortunately, whatever horde of locusts had invaded my house overlooked a single can of condensed milk. With that and a few items prescient enough to hide out in the back of the fridge, I whipped up a pie that — if I do say so myself — turned out downright scrumptious.

It was so good, as a matter of fact, that I made it again this past weekend … only this time I had the presence of mind to write down the ingredients and measurements.

The recipe is below — and not a green bean in sight, thank goodness.

I hope you enjoy it as much as my hips did.

Chocolate Coconut Pecan Custard Pie

Chocolate Coconut Pecan Custard Pie9-inch unbaked pie shell

3 eggs

1 egg, white separated from yolk

14-ounce can sweetened condensed milk

1¼ cups hot water (not boiling—from the tap works fine)

2 T. melted butter

1 tsp. vanilla

¼ tsp. salt

⅛ tsp. nutmeg

2 cups shredded coconut

¼ cup pecan pieces

½ cup chocolate chips (dark or semisweet)

1. Heat oven to 425 degrees.

2. Prepare your favorite pie crust. Whisk egg white with 1 tsp. water; brush over entire pie crust surface. (Coating pie crust with egg white prevents sogginess.)

3. In large bowl, beat 3 eggs plus additional yolk with a wire whisk or fork until well combined. Add sweetened condensed milk, hot water, melted butter, vanilla, salt, and nutmeg. Mix well.

4. Stir in coconut, pecan pieces, and chocolate chips. Pour filling into prepared pie shell.

5. Bake 10 minutes at 425 degrees, then reduce heat to 350 and bake an additional 25 to 30 minutes.

6. Cool at least 1 hour before serving. Refrigerate leftovers.

Note: For a gluten-free version, try Jacquie Rogers’s nut-based crust. You’ll find that recipe — and seven others, including my grandmother’s recipe for peach pie — in the Prairie Rose Publications anthology Wishing for a Cowboy .

Published on October 03, 2014 22:00

September 26, 2014

Lady Killers

The Wild West could be a dangerous place. If outlaws, gunfights, animal encounters, and Indian attacks didn’t do a body in, disease or accident very well might. For an unlucky few, danger emerged from an unexpected source: women with an axe to grind … repeatedly.

Belle Gunness and her childrenLizzie Borden may have been the most infamous of America’s female killers, but she certainly wasn’t the only woman to dispose of inconvenient family, friends, or strangers. She wasn’t even the most prolific American murderess. That honor probably goes to Belle Gunness, a Norwegian immigrant suspected of killing more than forty people — including two husbands and several suitors — in Illinois and Indiana at the turn of the 20th Century. When authorities began investigating disappearances, Gunness herself disappeared … after setting up a hired hand to take the fall for arson that burned her farmhouse to the ground with her three young children and the headless body of an unidentifiable woman inside.

Belle Gunness and her childrenLizzie Borden may have been the most infamous of America’s female killers, but she certainly wasn’t the only woman to dispose of inconvenient family, friends, or strangers. She wasn’t even the most prolific American murderess. That honor probably goes to Belle Gunness, a Norwegian immigrant suspected of killing more than forty people — including two husbands and several suitors — in Illinois and Indiana at the turn of the 20th Century. When authorities began investigating disappearances, Gunness herself disappeared … after setting up a hired hand to take the fall for arson that burned her farmhouse to the ground with her three young children and the headless body of an unidentifiable woman inside.The shocking crime of serial murder seems even more chilling when the perpetrator is a woman. Cultural and biological factors encourage women to eschew physical aggression. Most women fight with words or, sometimes, by manipulating male proxies. Consequently, females seldom go on the kind of violent binges that characterize male serial killers. In fact, only about 15 percent of serial murderers in history have been women.

According to Canadian author, filmmaker, and investigative historian Peter Vronsky, who holds a PhD in criminal justice, when men kill, they employ force and weapons. Restraint of the victim often provides part of the thrill: Many male serial killers derive sexual gratification from the act of taking a life. Women, on the other hand, prefer victims who are helpless or unsuspecting: 45 percent of convicted female serial killers used poison to dispose of spouses, children, the elderly, or the infirm. Instead of a sexual high, their primary motivation was money or revenge.

The eight female serial killers below were active during the nineteenth and very early twentieth centuries in the American West. (Another half-dozen cropped up east of the Mississippi during the same period.)

Delphine LaLaurie

Delphine LaLaurieThe volatile wife of a wealthy physician, LaLaurie tortured and killed slaves who displeased her. An 1834 fire at her New Orleans mansion revealed her depravity when a dozen maimed and starving men and women, along with a number of eviscerated corpses, were discovered in cages or chained to the walls in the attic. One woman had been skinned alive; another woman’s lips were sewn shut, and a man’s sexual organs had been removed. LaLaurie fled to avoid prosecution and reportedly died in Paris in December 1842. Years later, during renovations to the estate, contractors discovered even more slaves had been buried alive in the yard.

Delphine LaLaurieThe volatile wife of a wealthy physician, LaLaurie tortured and killed slaves who displeased her. An 1834 fire at her New Orleans mansion revealed her depravity when a dozen maimed and starving men and women, along with a number of eviscerated corpses, were discovered in cages or chained to the walls in the attic. One woman had been skinned alive; another woman’s lips were sewn shut, and a man’s sexual organs had been removed. LaLaurie fled to avoid prosecution and reportedly died in Paris in December 1842. Years later, during renovations to the estate, contractors discovered even more slaves had been buried alive in the yard.Mary Jane JacksonA New Orleans prostitute with a violent temper, Jackson was a relative anomaly among female serial killers: Described as a “husky,” universally feared woman, she physically overpowered her adult-male victims. Nicknamed Bricktop because of her flaming-red hair, between 1856 and 1861 Jackson beat to death one man and stabbed to death three others because they called her names, objected to her foul language, or argued with her. Sentenced to ten years in prison for the 1861 stabbing death of a jailer-cum-live-in-lover who attempted to thrash her, 25-year-old Jackson disappeared nine months later when the newly appointed military governor of New Orleans emptied the prisons by issuing blanket pardons.

Kate Bender

Kate BenderA member of the notorious Bloody Benders of Labette County, Kansas, beautiful 22-year-old Kate claimed to be a psychic. In 1872 and1873, she enthralled male guests over dinner at the family’s inn while men posing as her father and brother sneaked up behind the victims and bashed in their skulls with a sledgehammer or slit their throats. Among the four Bender family members, only Kate and her mother were related, though Kate may have been married to the man posing as her brother. When a traveling doctor disappeared after visiting the Benders’ waystation in 1872, his brother began an investigation that turned up 11 bodies buried on the property. The Benders, who robbed their victims, disappeared without a trace. A persistent rumor claims vigilantes dispensed final justice somewhere on the Kansas prairie.

Kate BenderA member of the notorious Bloody Benders of Labette County, Kansas, beautiful 22-year-old Kate claimed to be a psychic. In 1872 and1873, she enthralled male guests over dinner at the family’s inn while men posing as her father and brother sneaked up behind the victims and bashed in their skulls with a sledgehammer or slit their throats. Among the four Bender family members, only Kate and her mother were related, though Kate may have been married to the man posing as her brother. When a traveling doctor disappeared after visiting the Benders’ waystation in 1872, his brother began an investigation that turned up 11 bodies buried on the property. The Benders, who robbed their victims, disappeared without a trace. A persistent rumor claims vigilantes dispensed final justice somewhere on the Kansas prairie.Ellen EtheridgeDuring the first year after her 1912 marriage to a millionaire farmer, 22-year-old Etheridge poisoned four of his eight children. She attempted to kill a fifth child by forcing him to drink lye, but the 13-year-old boy escaped and ran for help. A minister’s daughter, Etheridge confessed to the killings and the attempted murder, laying the blame on what she saw as her husband’s betrayal: He had married her not for love, but to provide an unpaid servant for his offspring, upon whom he lavished both his affection and his money. In 1913, a Bosque County, Texas, jury sentenced her to life in prison. She died in her sixties at the Goree State Farm for Women in Huntsville, Texas.

Linda Burfield Hazzard

Linda Burfield HazzardThe first doctor in the U.S. to earn a medical degree as a “fasting specialist,” Hazzard was so committed to proving her theories about weight loss and health that she starved at least 15 patients to death. In 1912, she was convicted of manslaughter in the case of an Olalla, Washington, woman whose will she forged in order to steal the victim’s possessions. Hazzard served four years of a two- to twenty-year prison sentence before being paroled in late 1915. She died of self-starvation in 1938.

Linda Burfield HazzardThe first doctor in the U.S. to earn a medical degree as a “fasting specialist,” Hazzard was so committed to proving her theories about weight loss and health that she starved at least 15 patients to death. In 1912, she was convicted of manslaughter in the case of an Olalla, Washington, woman whose will she forged in order to steal the victim’s possessions. Hazzard served four years of a two- to twenty-year prison sentence before being paroled in late 1915. She died of self-starvation in 1938.Lyda Southard

Lyda SouthardA serial “black widow,” Lyda Southard married seven men in five states over the course of eight years. Between 1915 and 1920, four of her husbands, a brother-in-law, and Southard’s three-year-old daughter — all recently covered by life insurance policies at Southard’s suggestion — died only months after the nuptials, apparently of ptomaine poisoning, typhoid fever, influenza, or diphtheria. Southard was convicted of second-degree murder in the poisoning death of her first husband, earning her a ten-years-to-life sentence in the Old Idaho State Penitentiary. She escaped with the warden’s assistance in 1931, only to be recaptured and returned to serve another eleven years before receiving parole. After changing her name and divorcing three times, she died of a heart attack in 1958 in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Lyda SouthardA serial “black widow,” Lyda Southard married seven men in five states over the course of eight years. Between 1915 and 1920, four of her husbands, a brother-in-law, and Southard’s three-year-old daughter — all recently covered by life insurance policies at Southard’s suggestion — died only months after the nuptials, apparently of ptomaine poisoning, typhoid fever, influenza, or diphtheria. Southard was convicted of second-degree murder in the poisoning death of her first husband, earning her a ten-years-to-life sentence in the Old Idaho State Penitentiary. She escaped with the warden’s assistance in 1931, only to be recaptured and returned to serve another eleven years before receiving parole. After changing her name and divorcing three times, she died of a heart attack in 1958 in Salt Lake City, Utah.Della SorensonBetween 1918 and 1924, Sorenson killed eight family members to satisfy a twisted desire for revenge. Upon her arrest after an attempt to poison her second husband failed, she told authorities her niece and infant nephew, her first husband, her mother-in-law, two toddlers, and her own two daughters “bothered me, so I killed them.” She poisoned all of the children in the presence of their parents by feeding them cookies and candy laced with poison. A Dannebrog, Nebraska, jury declared the 28-year-old insane and committed her to the state mental asylum. She died there in 1941.

Bertha Gifford

Bertha Gifford and a six-year-old victim.At the turn of the 20th Century, Gifford was known as an angel of mercy in Catawissa, Missouri. Not until 1928 did authorities discover the nurse's deadly ruse: The twenty to twenty-five sick friends and family members she took into her home and cared for between 1909 and 1928 all died of arsenic poisoning. Gifford was declared insane and committed to the Missouri State Hospital, where she died in 1951.

Bertha Gifford and a six-year-old victim.At the turn of the 20th Century, Gifford was known as an angel of mercy in Catawissa, Missouri. Not until 1928 did authorities discover the nurse's deadly ruse: The twenty to twenty-five sick friends and family members she took into her home and cared for between 1909 and 1928 all died of arsenic poisoning. Gifford was declared insane and committed to the Missouri State Hospital, where she died in 1951.

Published on September 26, 2014 22:00

September 19, 2014

Naked in Church

Fiction writers face all sorts of fears: fear of rejection, fear of success, fear of failure, fear of the blank page, fear of running out of ideas, fear that this internal something that drives us to create is destructive, because all we've managed to put on paper so far is criminally bad... The list goes on.

Fiction writers face all sorts of fears: fear of rejection, fear of success, fear of failure, fear of the blank page, fear of running out of ideas, fear that this internal something that drives us to create is destructive, because all we've managed to put on paper so far is criminally bad... The list goes on.Recently, I've realized one of the biggest writing-related fears I face is what I call the naked-in-church fear. The nightmare reportedly is common: There you are on Sunday morning, filing into the sanctuary along with everyone else, when suddenly you realize you aren’t wearing a stitch of clothing ... and everyone is staring. “Oh dear,” you think, blushing scarlet from head to foot. “I know I was wearing something besides my birthday suit when I left the house. Of all the places to be caught in the nude. I’ll never live this down.”

Most dream interpretations attribute the naked-in-church nightmare to fear of exposure: as a fraud, as wanton beneath a prim exterior, as someone who harbors dark secrets. Psychologists often say the dream is an attempt by the subconscious to inform the dreamer he is being disloyal to himself by hiding something.

Regardless how emotionally close we are to friends and family, there are just some things humans don't want others to know, and writers are no exception. Like everyone else, we pile on the layers of clothing before we head out to church. However, what makes good fiction phenomenal is the writer’s ability to “bleed” onto the page; to open veins and let emotions and visceral experiences flow through our characters in order to move readers with the same force they moved us. To do that, we must peel off the emotional equivalent of our Sunday best.

Right now, I’m working on a scene that’s quite a bit different from anything I’ve written before. It’s been a pure battle to make the words work. I’ve changed point of view twice. I’ve moved the characters to another setting. I’ve played with the weather, which has absolutely nothing to do with the action because the characters are indoors. I’ve even ripped out the whole darn scene and started over.

That’s when I realized I was wearing too many clothes.

Now, someone with a firm grip on decorum might take a moment to close her eyes, breathe deeply, and attempt to crawl inside her characters’ skin. Sadly, I am not someone with a firm grip on decorum. Instead of walking the more conventional path, I decided to confront the naked-in-church fear head-on. Why not? I had the house to myself, except for the dogs. I would show that fear who was boss.

Dogs (and pleather chairs, which can be remarkably cold, I discovered) have the most uncanny ability to knock ridiculous notions right out of a person. All three of the canine critics raised their heads, yawned, and then filed from the room.

Not one of my finer moments. On the positive side, at least now I have a visceral connection to a couple of emotions that ought to be useful somewhere.

There is much to be gained from confronting one’s fears. The next time I confront one of mine, though, I believe I’ll take a less radical approach.

Thanks to ForestWander, a father-and-son team of nature photographers in West Virginia, for the image.

Published on September 19, 2014 22:00

September 12, 2014

Romance Novels: Agents of Social Change

Men of sense in all ages abhor those customs

Men of sense in all ages abhor those customswhich treat us only as the vassals of [their] sex.

—Abigail Adams (1744-1818)

second First Lady of the U.S.I’ve always considered it a bit odd that we need reminding women have contributed to science, art, philosophy, and society in general. Designating a specific month during which to focus on women’s history implies that for the rest of the year, everyone thinks of women as secondary characters instead of protagonists in the grand drama that is the human experience.

I do not wish women to have power

I do not wish women to have powerover men, but over themselves.

—Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797)

writer and advocate of women’s rights Women don’t sit around waiting for men to make all the great discoveries, think all the great thoughts, and fight all the dragons. They never have. Throughout history, as many women as men have explored the unexplored, cured the previously incurable, and given voices to those unable to speak for themselves. And, as has been famously stated, they did it all dancing backward in high heels.

“It would be ridiculous to talk of male and female atmospheres, male and female springs or rains, male and female sunshine...,” women’s rights pioneers Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton wrote in one of their suffrage speeches. “[H]ow much more ridiculous is it in relation to mind, to soul, to thought…?”

Old-fashioned ways which no longer apply

Old-fashioned ways which no longer applyto changed conditions are a snare in which

the feet of women have always become

readily entangled.

—Jane Addams (1860-1935)

social reformer, women’s rights activist, first

American woman to win the Nobel Peace PrizeAnthony and Stanton often railed against inequality between the genders and the resulting injustices — like lack of access to education and discriminatory civil laws — visited upon the distaff side of humanity. Today, the philosophy they espoused is, or should be, de rigueur, but until the mid-20th Century, speaking such thoughts in public in many societies carried significant risk to life and liberty. In some societies, it still does.

That is one reason I feel historical romance novels can be important beyond the obvious entertainment. Unlike much literature written in previous ages, primarily by men, romance novels written during the past twenty to thirty years, primarily by women, portray heroines and female villains with courage, determination, and strength equal to the hero’s. Call me a man-bashing feminist if you must, but I believe it is critical for readers, particularly younger ones, to be presented with women characters who are much more than decorative pedestal dwellers.

If women could go into your Congress,

If women could go into your Congress,I think justice would soon be done

to the Indians.

—Thoc-me-tony (aka Sara Winnemucca,

1844-1891),Pauite educator, interpreter,

writer, activistIn fact, when one studies history, it becomes impossible to consider the romantic notion of heroes on white horses rescuing damsels in distress anything more than exactly that: a romantic notion. On any frontier in any age, toughness and capability are essential for survival, regardless of gender. Today’s well-researched historical fiction makes that abundantly clear — and like it or not, fiction resonates in contemporary culture, subtly but undeniably influencing attitudes on both sides of the gender divide. Art has always been both reactive and proactive in that way.

The best protection any woman can have

The best protection any woman can have… is courage.

—Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815-1902)

social activist, abolitionist,

women’s rights crusaderSo, readers and writers of romance, take a bow. We’re not wasting our time with ludicrous, lowbrow literature; we’re buttressing ramparts our foremothers built long ago.

The day will come when men will recognize woman as his peer, not only at the fireside, but in councils of the nation. Then, and not until then, will there be the perfect comradeship, the ideal union between the sexes that shall result in the highest development of the race.

—Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906), social reformer, women’s suffrage leader

Published on September 12, 2014 22:00

September 5, 2014

From the Mouths of Cowboys

Cowboys branding a calf. (National Park Service)It’s been said that when a cowboy’s too old to set a bad example, he hands out advice. According to the National Park Service, which lists several historic ranches among its properties, old cowboys weren’t all that common, at least during the days when cattle roamed the open range.

Cowboys branding a calf. (National Park Service)It’s been said that when a cowboy’s too old to set a bad example, he hands out advice. According to the National Park Service, which lists several historic ranches among its properties, old cowboys weren’t all that common, at least during the days when cattle roamed the open range.Crusty old cowboys were mainly an invention of movies. Most cowboys were young, some only eleven or twelve. By the time they were in their mid-20s, most had taken up ranching on their own or found a less strenuous way of life. It was a young man's trade, for the hardships of six-month trail drives and the injuries sustained in working with livestock took a physical toll. Some cowboys eventually became cattlemen, while others stayed on the ranches as cooks and handymen.

—Brochure for the Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site, Montana

Nevertheless cowboys have a reputation for passing along hard-earned wisdom in some downright colorful ways. Even today, folks who work ranches — and country people in general — speak a language all their own.

Here are some choice tidbits one might hear from a cowboy.

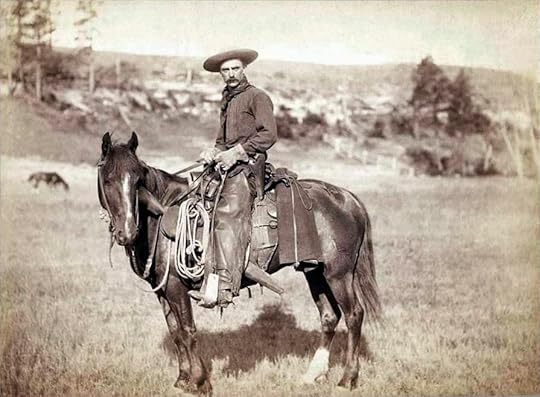

"The Cow Boy," J.C.H. Grabill, photographer

"The Cow Boy," J.C.H. Grabill, photographerSturgis, Dakota Territory, c. 1888 (Library of Congress)

About conversation:Don’t expect mules and cooks to share your sense of humor.

Don’t make a long story short just so you can tell another one.

Don’t worry about bitin’ off more’n you can chew. Your mouth is probably a whole lot bigger’n you think.

If you have the opportunity to keep from makin’ a fool of yourself, take it.

Never trust a man who agrees with you. He’s probably wrong.

Speak your mind, but ride a fast horse.

When there’s nothin’ left to be said, don’t be sayin’ it.

"Branding Calves on Roundup," J.C.H. Grabill, photographer

"Branding Calves on Roundup," J.C.H. Grabill, photographerSouth Dakota Territory, 1888 (Library of Congress)

About conflict:Always drink your whiskey with your gun hand, to show your friendly intentions.

Don’t bother arguin’ with a rabid coyote.

Don’t corner somethin’ meaner than you.

Don’t wake a sleepin’ rattler.

If you climb into the saddle, be ready for the ride.

Never drop your gun to hug a grizzly.

When your head’s in the bear’s mouth ain’t the time to be smackin’ him on the nose.

Frederic Remington drawing

Frederic Remington drawing(Harper's new monthly magazine v.91, issue 543, August 1895)

About life in general:Don’t get callouses from pattin’ your own back.

Don’t use your spurs if you don’t know where you’re goin’.

If it don’t seem like it’s worth the effort, it probably ain’t.

Keep skunks, lawyers, and bankers at a distance.

Never approach a bull from the front, a horse from the rear, or a fool from any direction.

Never follow good whiskey with water, unless you’re out of whiskey.

Never take to sawin’ on the branch that’s supportin’ you, unless you’re bein’ hung from it.

Published on September 05, 2014 22:00

August 29, 2014

Stagecoaches: Forging the Way West

[image error] A stagecoach outside the Twin Falls News

office in Twin Falls, Idaho.Stagecoaches carried not only passengers, but also mail, money, and cargo of all kinds. Drivers often delivered packages much as a modern mail carrier might. They also transacted business for important clients of the stagecoach line.

A few stagecoach facts:The first Concord stagecoach was built in 1827 by the Abbot Downing Company, which improved earlier coach designs by using leather strap braces instead of a spring suspension. The coaches were so sturdy, they usually wore out before they broke down. The company built more than 700 Concord coaches in the twenty years of its existence, selling its products not only to lines in the U.S., but also in Australia, South America, and Africa.

In 1827, Boston served as a hub for 77 stagecoach lines. By 1832, the number had grown to 106.

The U.S. government authorized the first transcontinental overland mail route in 1857. By federal law, the stagecoaches that ran the route were required to transport supplies, mail, and passengers from the Mississippi River to San Francisco, safely, in twenty-five or fewer days.

The Butterfield Overland Express won the first federal contract for transcontinental stagecoach delivery: a six-year, $600,000 job. In 1858, John Butterfield established two starting points: Tipton, Missouri (near St. Louis) and Memphis, Tennessee. The trails converged at Fort Smith, Arkansas, and then proceeded through Arkansas, Texas, and the New Mexico Territory to California. Covering approximately 2,812 miles, the Butterfield Trail was the longest stagecoach line in history. The service ran only until the Civil War began in 1861.

Charley Parkhurst may have been the most famous stagecoach driver in history. So tough that bandits would not attack his stages, he became a legend in his own lifetime. But Charley had a secret: He was born a woman. After living as a man for 55 years (from the age of 12), he died of cancer in December 1879. Only when friends laid out his body after his death was his genetic identity discovered.

Concord stage with military guard riding on top, ca. 1869.

Concord stage with military guard riding on top, ca. 1869.(U.S. National Archives and Records Administration)

Published on August 29, 2014 22:00

August 22, 2014

Show Me Your Badge

Texas Ranger badges are a hot commodity in the collectibles market, but the caveat “buyer beware” applies in a big way. The vast majority of items marketed as genuine Texas Ranger badges are reproductions, facsimiles, or toys. Very few legitimate badges exist outside museums and family collections, and those that do hardly ever are sold. There’s a very good reason for that: Manufacturing, possessing, or selling Texas Ranger insignia, even fakes that are “deceptively similar” to the real thing, violates Texas law except in specific circumstances.

According to Byron A. Johnson, executive director of the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum (the official historical center of the Texas Ranger law-enforcement agency), “Spurious badges and fraudulent representation or transactions connected with them date back to the 1950s and are increasing. We receive anywhere from 10 to 30 inquiries a month on badges, the majority connected with sales on eBay.”

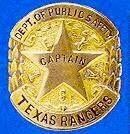

If you had to, could you identify a legitimate Texas Ranger badge? Test your knowledge: Which of the alleged badges below are genuine? Pick one from each set. (All images are ©Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum, Waco, Texas, and are used with permission. All Rights Reserved.)

Set 1

©TRHFM, Waco, TX

©TRHFM, Waco, TX

©TRHFM, Waco, TX

©TRHFM, Waco, TXAnswer: The right-hand badge, dated 1889, is the earliest authenticated Texas Ranger badge in the collection of the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum. Badges weren’t standard issue for Rangers until 1935, although from 1874 onward, individual Rangers sometimes commissioned badges from jewelers or gunsmiths, who made them from Mexican coins. Relatively few Rangers wore a badge out in the open. As for the item on the left? There’s no such thing as a “Texas Ranger Special Agent.”

Set 2

©TRHFM, Waco, TX

©TRHFM, Waco, TX

©TRHFM, Waco, TX

©TRHFM, Waco, TXAnswer: On the left is an official shield-type badge issued between 1938 and 1957. Ranger captains received gold badges; the shields issued to lower ranks were silver. The badge on the right is a fake, though similar authentic badges exist.

Set 3

©TRHFM, Waco, TX

©TRHFM, Waco, TX

©TRHFM, Waco, TX

©TRHFM, Waco, TXAnswer: The left-hand badge was the official badge of the Rangers from July 1957 to October 1962. Called the “blue bottle cap badge,” the solid, “modernized” design was universally reviled. The right-hand badge is a fake. According to the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum, “No genuine Texas Ranger badges are known to exist with ‘Frontier Battalion’ engraved on them.”

Set 4

©TRHFM, Waco, TX

©TRHFM, Waco, TX ©TRHFM, Waco, TX

©TRHFM, Waco, TXAnswer: The badge on the right, called the “wagon wheel badge,” has been the official Texas Ranger badge since October 1962. Each is made from a Mexican five-peso silver coin. The badge on the left is a “fantasy badge.” According to the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum, the most common designation on such badges is “Co. A.”

How did you do?

For more information about the Texas Rangers—including the history of the organization, biographical sketches of individual Rangers, and all kinds of information about badges and other insignia—visit the Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum online at TexasRanger.org. The museum and its staff have my utmost gratitude for their assistance with this post.

Published on August 22, 2014 22:00

August 15, 2014

Tom Rizzo's West

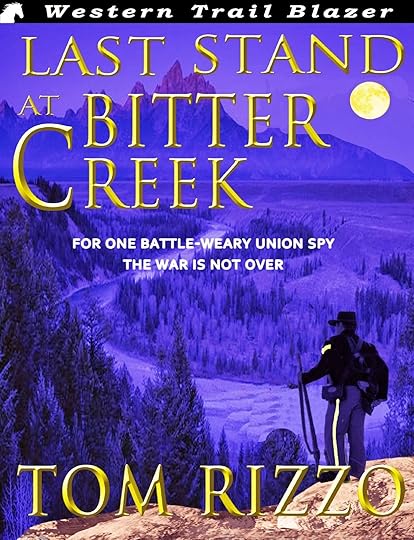

Tom RizzoTom Rizzo writes westerns — good ones, with traditional action aplenty and, so far, romantic elements that play significant roles in the story. He writes westerns so well, in fact, that his debut novel, Last Stand at Bitter Creek, was among the nominees for the 2013 Peacemaker Awards, in the Best Western First Novel category.

Tom RizzoTom Rizzo writes westerns — good ones, with traditional action aplenty and, so far, romantic elements that play significant roles in the story. He writes westerns so well, in fact, that his debut novel, Last Stand at Bitter Creek, was among the nominees for the 2013 Peacemaker Awards, in the Best Western First Novel category.The man bears watching, not only because he’s a rising voice in the genre, but also because of the level of historical detail he incorporates into his work. Rizzo loosely based Last Stand at Bitter Creek on a little-known theft of valuable documents during the Civil War. The resulting action-adventure tale reads a bit like Louis L’Amour dressed National Treasure and Robert Ludlum’s Bourne novels in six guns and denim.

Though Rizzo presents his tales from the male point of view, his female characters clearly are more than stereotypical damsels in need of rescue by a hard-bitten cowboy. Rizzo’s women think, they act, and they help drive the plot.

Like many other former journalists, Rizzo arrived on fiction’s doorstep later in life. His interests are broad, from mystery and crime to thriller and science fiction. He could have attacked any of those genres; yet, he chose to write historical westerns despite conventional wisdom saying “the western is dead.”

According to Rizzo, it’s only wounded.

Why westerns?

Tom Rizzo: Westerns represent such a rich legacy of American history. I grew up in the Midwest, small-town America. Like others, my introduction to westerns came from black-and-white movies. The plots were basic, simple, and straightforward in most cases, but it was the sense of adventure that attracted me.

Then, I began to read various authors and became impressed with their realistic visions and interpretations of the frontier. As much as anything, however, it was the physical beauty of the West that captured my attention and fired my imagination. The language of the West is its landscape — a visual poetry of mountains, rivers, streams, and deserts, rolling hills, and the sky.

Most authors who write in the genre grit their teeth every time they hear “westerns don’t sell” or “the western is dead.” Judging by the number of authors who continue to write westerns, though, a funeral may be just a tad premature. What would you like people who insist on consigning westerns to Boot Hill to know?

I think, at times, there’s sort of a Neanderthal mindset about westerns. Not from the readers’ viewpoint, but from that of literary agents and publishers. It’s as if they’re standing wild-eyed, brandishing a garlic ring and crucifix in an attempt to ward off the evil western writer who wants to foster the traditional shoot-’em-up, cowboy-and-Indian story.

As you know, this type of thinking is downwind of reality. This genre accommodates a number of sub-genres. Westerns, in fact, represent historical adventures, historical mysteries, historical thrillers, historical romances, and even historical horror and fantasy.

Perhaps there’s a marketing disconnect. We have to do a better job of attracting readers who haven’t yet tested the waters.

One of the common laments we hear within the admittedly aging community of western historical writers is that the traditional market for westerns is aging, too. Some see attracting younger readers as the key to keeping the genre alive, but no one seems quite sure how to go about that. Got any ideas?

One of the common laments we hear within the admittedly aging community of western historical writers is that the traditional market for westerns is aging, too. Some see attracting younger readers as the key to keeping the genre alive, but no one seems quite sure how to go about that. Got any ideas?Why don’t you just put me on the spot? A great question with no easy answer.

Some writers — Dale B. Jackson , JR Sanders, and Cheryl Pierson come to mind — have written novels aimed at the young adult and have done very well with those books. That could be a way to lure younger readers into sticking with the genre as they age.

At the same time, I think it comes down to an old-fashioned sales and marketing strategy in developing a message aimed at convincing younger readers to at least try the product. Westerns are not only great tales of adventures, but also wonderful resources of American history.

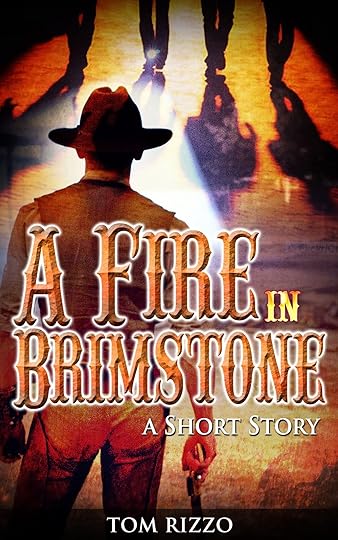

Traditional westerns often include a conspicuous romantic component, although many traditional western writers — especially men — are hesitant to call their stories “romances.” Your short story “A Fire in Brimstone” uses a romance between the sheriff and a café owner to propel the plot, and a case could be made for the story’s conclusion meeting the happily-ever-after-ending requirement of the romance genre. Where do you draw the line between “western” and “western romance”?

I don’t know that I could draw a line between the two — at least consciously. When I wrote “A Fire in Brimstone,” the term “western romance” wasn’t top-of-mind — or any other term, for that matter. The romantic attraction between the two characters seemed, at least to me, a natural component of the story.

Sometimes labels get in the way of good storytelling. I think most writers have of an umbrella goal in mind when they write. For example, no matter what the plot, I try to present characters in conflict — either with one another or with their own emotions — who face adversity and are striving for some level of justice or redemption.

You’re fond of a variety of genres from western to science fiction, noir, mystery, and political thriller. Do you find your eclectic tastes coming together in your work, intentionally or otherwise? How difficult is it to make all those influences work together?

What I find remarkable about the structure of the western is the ability to weave in varied sub-genres without sacrificing the concept of a true western. The difficulty, of course, depends on the intricacy of the plot or storyline.

The western can easily accommodate mystery, noir, and political thrillers. Science fiction, as well, but that would be a bit of stretch for me.

On your blog, you devote significant virtual ink to exposing some of the lesser-known scoundrels of the Old West — outlaws and wannabes alike. In fact, you’ve published a non-fiction book, Heroes & Rogues, containing profiles of some of the not-quite-notorious baddies and their not-quite-famous adversaries. To what do you attribute this fascination with villainy?

On your blog, you devote significant virtual ink to exposing some of the lesser-known scoundrels of the Old West — outlaws and wannabes alike. In fact, you’ve published a non-fiction book, Heroes & Rogues, containing profiles of some of the not-quite-notorious baddies and their not-quite-famous adversaries. To what do you attribute this fascination with villainy?I think it goes back to my childhood. When my brothers and the neighborhood kids played so-called cowboys and outlaws, I was the first to volunteer to play the outlaw. They couldn’t understand why. But, I always felt an incredible amount of freedom in such a role. No rules to follow. No warning anyone what you were about to do. No decorum to maintain. The freedom to be devious, sneaky, and hide anywhere you could — as long as you stayed in the neighborhood and didn’t climb into Mr. Quinn’s Bing cherry tree to hide, because Mr. Quinn would shoot you.

It’s fascinating to me how many men wore a badge and then turned outlaw. Or kept the badge and played outlaw anyway. It amazes me how many of them would switch back and forth. Many — or most — of those who did ride the outlaw trail led very short lives, on average.

If you had lived in the Old West, when and where would you have taken up residence, and what line of work would you have pursued?

Wyoming, I think, would be a great place to live. Spacious. Beautiful. I would have been happy to live in a small-but-growing town and run the local newspaper. Newspaper editors, as you know, weren’t worth their salt unless they raised a little hell. And that would be fun, as long as you didn’t have to be fast with a gun.

Find Tom Rizzo online at TomRizzo.com, as well as on Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn. His Amazon author page offers a listing of his books.

Published on August 15, 2014 22:00

August 7, 2014

The Bandit Who Wouldn't Give Up

Elmer McCurdy in his army days.Some men are born to infamy; others have infamy thrust upon them. And then there are those like Elmer McCurdy who slip into infamy sideways … sixty-five years after they should have faded into obscurity.

Elmer McCurdy in his army days.Some men are born to infamy; others have infamy thrust upon them. And then there are those like Elmer McCurdy who slip into infamy sideways … sixty-five years after they should have faded into obscurity.Except for his out-of-wedlock birth in Washington, Maine, in January 1880, McCurdy seems to have enjoyed an uneventful childhood as the adopted son of his 17-year-old biological mother’s older, married sister. When McCurdy was ten, the man he had always believed to be his father died, and the truth of his parentage came out. At fifteen, he ran away from home and drifted through the Midwest, developing a fondness for alcohol and working odd jobs until he joined the army. Trained in demolition, he left the service in early 1911 with an honorable discharge and a professional acquaintance with nitroglycerin.

That’s when things took a turn for the worse. Unable to find a civilian job, McCurdy resolved to gain fame and fortune the old-fashioned way: by stealing it — specifically, by robbing trains. The career choice didn’t work out well for him. On his first job, he overdid the nitro and not only nearly blew the train’s safe through the wall, but also melted $4,000 in silver coins to the floor. McCurdy and three accomplices pried up about $450 in silver lumps before scramming barely ahead of the law.

After that, McCurdy backed off on the explosives, producing less than stellar results when trains’ safes failed to open. Apparently deciding a stationary target might prove less vexing, McCurdy aimed his demolition skills at a bank vault in the middle of the night. The resulting blast woke up the entire town, and the gang made off with about $150.

They went back to robbing trains.

On Oct. 4, 1911, despite careful planning, the outlaws held up the wrong train, netting a haul of about $90 and some whiskey. Evidently disgruntled, McCurdy’s cohorts abandoned him.

Undaunted, he quickly put together a new gang and three days later — on Oct. 7, 1911 — held up a Missouri, Kansas, and Texas passenger train near Pawhuska, Oklahoma. The take was an unimpressive $46, two jugs of whiskey … and a posse.

Mere hours later, during an armed standoff on an Oklahoma farm, a drunken McCurdy announced from a hayloft that the posse would never take him alive. Foregoing the $2,000 bounty for bringing the bandit to trial, the lawmen obliged by killing him.

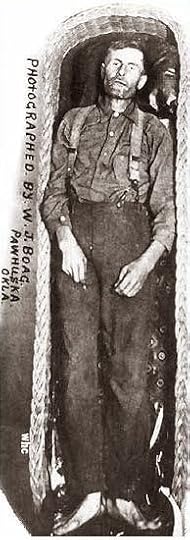

Elmer McCurdy on display at the

Elmer McCurdy on display at thePawhuska, Oklahoma, mortuary.That would have been the end of a less-than-illustrious career for most outlaws, but Elmer McCurdy’s career was only beginning.

When no one claimed the hapless train-robber’s remains, the mortician put McCurdy’s body on display as a somewhat gruesome promotional gimmick. For the next four years, the embalmed corpse, in a pine box bearing a sign that read “The Bandit Who Wouldn’t Give Up,” adorned the front window of the mortuary.

In 1915, two men claiming to be McCurdy’s brothers took possession of the body, ostensibly to provide a proper burial. Instead, they exhibited “A Famous Oklahoma Outlaw” as part of the Great Patterson Shows traveling carnival.

McCurdy’s corpse changed hands several times over the next two decades, popping up in all sorts of places: at an amusement park near Mount Rushmore, in several freak shows, and even in the lobby of a theater during a screening of the 1933 film Narcotic. For much of the 1930s and ’40s, McCurdy’s mummified remains, thought to be a mannequin, held a place of honor in the Sonney Amusement Museum of Crime in Los Angeles.

In 1971, an L.A. wax museum bought the by-then-unidentified “mannequin.” Until 1976, McCurdy was part of the museum’s display about Bill Doolin, an Oklahoma outlaw who actually achieved a good deal of notoriety while he was alive.

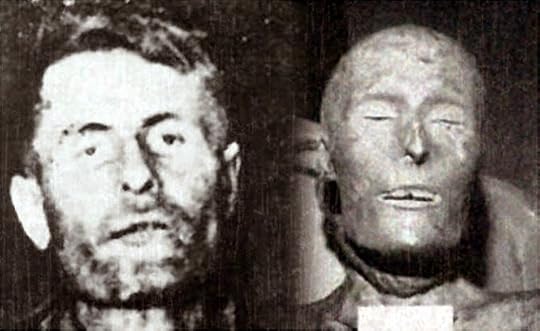

Sixty-five years after his death, McCurdy would achieve notoriety, too, though not in quite the way he may have hoped. The failed outlaw, painted fluorescent orange, made one final public appearance in December 1976, as a prop inside the Laff in the Dark funhouse at the Nu-Pike amusement park in Long Beach, California. While filming an episode of The Six Million Dollar Man inside the building, a crew member accidentally broke an arm off what he thought was a wax dummy hanging from a gallows. A protruding bone revealed the truth. Forensic anthropologists and the Los Angeles County Coroner identified the body.

Left: Elmer McCurdy in coffin. Right: The "wax mannequin" recovered from the funhouse.

Left: Elmer McCurdy in coffin. Right: The "wax mannequin" recovered from the funhouse.On April 22, 1977, Elmer McCurdy’s well-traveled remains were interred in the Boot Hill section of the Summit View Cemetery in Guthrie, Oklahoma — ironically, alongside the final resting place of Bill Doolin. As a precautionary measure, the state medical examiner ordered two cubic yards of concrete poured over the casket before the grave was closed.

So far, at least, it appears “The Bandit Who Wouldn’t Give Up” finally did.

Published on August 07, 2014 22:00

Hole in the Web Gang

Western history, tidbits, trivia, and other fun stuff.

- Kathleen Rice Adams's profile

- 18 followers