Cindy Conner's Blog, page 8

December 23, 2014

Seed Libraries–Coming Soon!

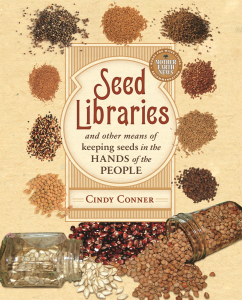

My newest book, Seed Libraries and Other Means of Keeping Seeds in the Hands of the People, will be available soon. My publisher, New Society, tells me that it is now at the printers. Beginning in January 2015, you can order Seed Libraries through Homeplace Earth and it will ship as soon as we have copies, which may not be until the first week in February. In celebration of this newest book we are offering Free Shipping within the continental US on all book and DVD orders for the month of January. All books ordered through Homeplace Earth are signed copies.

My newest book, Seed Libraries and Other Means of Keeping Seeds in the Hands of the People, will be available soon. My publisher, New Society, tells me that it is now at the printers. Beginning in January 2015, you can order Seed Libraries through Homeplace Earth and it will ship as soon as we have copies, which may not be until the first week in February. In celebration of this newest book we are offering Free Shipping within the continental US on all book and DVD orders for the month of January. All books ordered through Homeplace Earth are signed copies.

Seed Libraries has come on the heels of Grow a Sustainable Diet and it has been quite a journey. Just so you know, there are no new books planned on the horizon. Writing these books has been a grand adventure, but I do have a lot of other projects to catch up on and a garden to tend. Grow a Sustainable Diet grew out of the work I had been doing for many years. Writing Seed Libraries was a different experience. I had to reach out of my comfort zone and explore the work others have been doing. Besides reporting what I found, I identified common areas that need to be addressed if a group was to start a seed library and be successful. (I believe it needs to be more than one person from the get-go.) Being a seed saver myself, I am aware of the pitfalls that may arise when organizing and maintaining a project such as a seed library. My suggestions will help my readers foresee challenges and move forward smoothly.

Besides the mechanics of starting a seed library, this book promotes celebrating seeds any way you can. My post Start a Seed Library will give you suggestions for getting started. However, there is so much more to it than setting up the program. You want to engage your seed savers through the whole year. In addition you should want to engage the public. Even if someone isn���t a seed saver, they can learn about what you are doing and become a supporter of the movement to keep the seeds in the hands of the people. Otherwise, corporations will have control of all the seeds and whoever controls the seeds controls the food supply.

Celebrate seeds anyway you can. Saving and exchanging them, of course, is what a seed library is about, but you can also celebrate seeds with art and music. Promote books that refer to anything about seeds and gardening, eating locally, preserving genetic diversity, etc. Post photos and artwork that show plants going to seed. Sing about seeds and the wonders of nature. Take a holistic approach to seed saving and make it as much a part of your life as you can. You will find yourself thinking about where the seeds came from to produce whatever you are eating.

Plant gardens in your community for the purpose of saving and sharing seeds and plan educational programs around it. If not a whole garden, this year learn to save seeds from a few of the crops in your garden. If you are new at this, begin with one crop. Make it your focus and study everything there is to know about that crop to go from seed to seed. Once you have learned about that, share your knowledge and seeds with others. Seeds are very flexible and will adapt to the ecosystem where they are grown. When you save them yourself you are naturally producing seeds that are acclimated to your community.

Seed libraries can be set up as seed sharing programs in public libraries and, since public libraries are already community centers, it makes sense to do that. However, seed sharing programs can take many forms and can happen in many different places. In Seed Libraries I���ve given you examples of that. If you are already a seed saver, or if 2015 is your year to delve into seeds, use this book to help you make a difference with others. If you haven���t finished your Christmas shopping yet, and you have a seed saver on your list, print this post and give it with a promise of ordering the book in January. Seed libraries are exciting ways for people to come together to preserve and develop varieties unique to their region, thus ensuring a resilient food system.

We are past the winter solstice and each new day will bring a little more light. In this busy holiday time, take a moment to notice and enjoy the new light.

December 9, 2014

Building Low Tunnels and Securing the Covers

Low Tunnel

Season extension structures resembling low tunnels are a great way to protect overwintering vegetables. I use them to have fresh greens���kale, collards, and chard���on the table through the winter months. They are easy to build with plastic pipe and either clear plastic sheeting or greenhouse plastic. I would love to not have any plastic in my garden, but until I have a better alternative, I make an exception for this.

Plastic pipe easily bends to form the arches that hold up the plastic cover. My garden beds are 4��� wide and I use an 8��� length of plastic pipe (1/2��� inside diameter) for each arch, giving me a tunnel with a height of about 30���. Some people use metal electrical conduit for their arches, bending them around a homemade jig. I space the arches about 4��� apart down the length of the bed. Another piece of plastic pipe is put on top, becoming a ridge pole to connect the arches. A screw is used to attach the ridge pole to the top of each arch. It is important to have the ridge pole.

My arches are held in place by either putting them over pieces of rebar extending up from the ground or by inserting them into larger pieces of plastic pipe, also extending up from the ground. Whether rebar or larger plastic pipe is used, the pieces of each are cut to 2��� lengths. Plastic pipe can be cut easy enough and you can buy rebar already cut into 2��� lengths. Look for rebar where cement blocks are sold. One foot of each anchor piece is driven into the ground, leaving 12��� sticking up to receive the end of the arch.

Next comes the plastic cover. You can find clear plastic sheeting in a hardware store or big box building supply store (look for it in the paint department). Make sure it is 6 ml thick to withstand the winter weather. This construction plastic has no UV protection, but since you are only using it through the cold months, you can get a couple years use out of it if you store it out of the sun and keep the mice away during the off-season. Greenhouse plastic is good if you can get it since it will last longer. If you are building a structure that will be in the weather all year long, go with greenhouse plastic. A piece 10��� wide is good to go over the 8��� arches covering my 4��� wide beds.

The easiest way to secure the plastic cover to the pipes is with plastic clips, called garden clips or snap clamps, that are sold for this purpose. Johnny���s sells them and they are available at other garden and greenhouse supply sources. You can make some from plastic pipe, but if you need to take them on and off, the ones you buy are easier to work with. Okay, I know it is December already and if you had greens to protect, most likely you have already put up a structure like this if you intended to. I���m really writing this post to talk about the covers. You can build a low tunnel from these directions, but if you stop here you will have problems when the wind picks up or when it comes to harvesting from your tunnel through the winter.

Screw eye inserted into arch secures row cover cord.

The plastic covers on my low tunnels stick out 12��� on the sides. Some gardeners put sand bags, rocks, or pieces of wood on that extra to hold the cover down. On a calm day, it might seem to do the job, but the wind will easily whip the plastic out from under these things. Besides, if you have 18��� wide paths like I do, there is no extra room for sandbags, rocks, or pieces of wood. You will be tripping over these long after the covers were removed in the spring, unless you are diligent in taking them up. It would take putting many clips across each arch to secure your plastic cover enough to hold it through high winds. Even if you were willing to work with that many clips, you need to be able to access the plants inside through the season and it isn���t practical to be messing with so many fasteners each time.

My solution is to put a cord across from one arch to the next, alternating sides. You need the ridge pole to hold the cord up. I usually use 1/8��� nylon cord found in hardware/building supply stores, but have used old clothesline if that was available. If you already have a low tunnel and have experienced problems with wind, you can add this feature and alleviate problems the rest of the winter. It involves putting a screw eye near the base of each pipe the cord attaches to. I use a drill to make a pilot hole for the screw eye.

The bungee provides tension to hold the cord securely to the cover.

Years ago when I first did this I thought I needed to build a wood box and use pipe clamps to hold the arches, screwing the screw eye into the wood beside the pipe. Later I discovered that it is fine putting the screw eye directly into the plastic pipe. Of course, there is more material to screw into if there are two layers of pipe (the anchor pipe and the arch pipe), but it also works well if the arch is put over rebar. I have not put a screw eye into a metal pipe, but I imagine it would work well, also. If anyone has done that, I welcome your comments. Using a bungee cord between the screw eye on one end arch and the cord helps to apply tension to the cord.

The cord holds the plastic sheeting in place for venting or harvesting.

There are so many great things about securing the cover this way. Most importantly, it doesn���t come off in the wind. Another advantage is that all those things you put in the path to hold the plastic down are not necessary anymore. And the harvest���it is so easy! You can lift the plastic at any point along the sides to harvest and it is held in place under the cord. You will still use clips, but only on the end arches. The cover can be cut to come a few inches over the end arches and be secured with the clips. A separate piece of plastic sheeting can be cut to fit the ends. In mild weather it can be left off. When it is needed, it can be secured with the same clip that holds the tunnel plastic, holding two pieces at once. There are so many ventilation advantages with a separate end piece. Once the weather gets severe enough for me to put on the end pieces, I will fold the top edge down for ventilation on the warmer winter days.

Venting the row cover ends.

I got the idea for using a cord over the plastic cover from Eliot Coleman in his book Four Season Harvest. He used wire arches with a loop bent into it to anchor the cord. Arches from plastic or metal pipe with a ridge pole can withstand more severe weather than the wire arches he described. If you have been having trouble with the plastic covers on your row tunnels and haven���t used a cord to secure them, take the time on a mild day to go out to your garden and make the upgrade. You will be happy you did.

November 18, 2014

Seed School

Bill McDorman teaching at Seed School. Belle Starr is on the left.

I recently attended Rocky Mountain Seed Alliance’s six day Seed School in Buhl, Idaho. Bill McDorman and Belle Starr founded Rocky Mountain Seed Alliance (RMSA) this year, along with their friend John Caccia. John manages the Wood River Seed Library that was formed in early 2014. According to their website, the mission of RMSA is to “connect communities with the seeds that sustain them. Through education and other supportive services, this organization would help people reclaim the ancient tradition of seed saving and stewardship to grow a more resilient future in their towns, neighborhoods, and backyards. Their vision: a region filled with local farmers and gardeners producing a diverse abundance of crops—food, wildflowers, and grasses—from locally adapted seeds.”

Bill and Belle founded RMSA after three years with Native Seeds/SEARCH. Native Seeds/SEARCH (NS/S) is the go-to place to find seeds native to the Southwest. There are educational programs at NS/S, but the emphasis is on the seeds—preserving them, growing them, and sharing them. The emphasis at RMSA is on education. Through education there will be more people and organizations available to do the preserving, growing, and sharing work.

Germination test with 100 seeds.

Information covered at Seed School included, but was not limited to, seed breeding, germination testing, harvesting and processing, seed libraries, and seed enterprises. Although seeds can stay viable for many years, it is good to know the germination rate to know how much to plant, particularly if you are sharing them with others. The germination tests I do at home are done with only 10 seeds at a time and are sufficient for my own use. This summer a new seed library in Pennsylvania was challenged by the PA Department of Agriculture and asked to conform to the same laws that govern seed companies. One of the requirements was to have germination tests done–the kind that require 100 seeds to be tested at a time. I don’t believe that is necessary for a seed library, but the test is actually something you can do at home. Put 100 seeds on a damp paper towel, roll it up and keep it moist for a few days, then check it again. We did that at Seed School using wheat seed. Whether you are using 10 seeds or 100 for your germination tests, it is a good activity to do with volunteers if you are involved with a seed library. You receive valuable information to pass on with the seeds and your volunteers receive valuable experience, not to mention the camaraderie that develops with people working together.

We visited a USDA lab and a native plant nursery. Everyone we met was passionate about their work. The nursery produced most of the native plants that were installed in the region regardless of which company or government agency was the local supplier. So much for diversity of sources. Likewise, there are fewer sources of organic seed than you might think. Seed companies don’t necessarily grow all the seeds they sell and some don’t grow any. High Mowing has always only sold organic seed. According to their website, although they grow more than 60 varieties themselves, other varieties are supplied by growers in the Northeast, the Northwest, and from large wholesale organic seed companies such as Vitalis Seeds, Bego Seeds, and Genesis Seeds. You could be buying organic seeds that weren’t even grown in this country, let alone in your region! It does make you think. Companies that do not limit themselves to organic seeds could also be sourcing seeds from Seminis, now a subsidiary of Monsanto. When Monsanto bought out Seminis, Fedco Seeds decided to cut ties with Seminis—a big step for any seed company at the time. You can read here about the current state of our seed supply in the words of CR Lawn of Fedco in a talk he gave in February 2013.

Don Tipping explaining threshing.

Don Tipping of Siskiyou Seeds in Williams, Oregon was one of the presenters at Seed School. The home farm of Siskiyou Seeds is Seven Seeds Farm where about 60% of the seed for the company is grown. To offer more diversity in the catalog, Siskiyou looks to other growers, many in southwest Oregon. A description of each of those growers is in the catalog and each variety of seed offered shows the source of the seed in the description. Siskiyou turns to High Mowing for some of their varieties, but you know which ones were bought from that wholesaler from the catalog descriptions.

Seven Seeds Farm is part of the Family Farmers Seed Cooperative, a “new approach in seed security through supporting the development of bioregional seed producing hubs linked with a national marketing, breeding, and quality assurance program.” Closer to my home is a similar cooperative– Common Wealth Seed Growers—made up of my friends at Twin Oaks Seed Farm, Living Energy Farm, and All Farm Organics. At Seed School I met Luke Callahan of SeedWise, which is an online marketplace that provides a way for home gardeners to connect with very small seed companies. Common Wealth Seed Growers is listed with SeedWise.

In 2003 and 2004 I attended a series of workshops organized to educate seed growers in the Southeast region of the US. It was part of the Saving Our Seed initiative. One of the results of that project was the seed production manuals for the Mid-Atlantic and South and for the Pacific Northwest that you can freely access online now. Southern Exposure Seed Exchange is the main market for seed growers in my region, but the growers here sell to other companies, also. At the time I wondered what would result from those workshops. I knew many people present and didn’t imagine them rushing out to grow seeds for Southern Exposure anytime soon. Well, a decade has passed and a network of growers has developed. My daughter even grew seeds for Southern Exposure this year!

If you are concerned about the source of your seeds (as you very well should be), learn to grow your own or buy from small growers in your region. We can’t change the world overnight, which would result in chaos anyway. But, with each action we take we send out ripples that can result in a lasting, positive change. Seed School at Rocky Mountain Seed Alliance produced some ripples that I know are going to make a difference in keeping the seeds in the hands of  the people for years to come.

the people for years to come.

November 4, 2014

Self-Directed Gardening Education

As you are wrapping up the gardening year, I hope you have recorded questions you might have had over the season. Maybe you have a crop that just never performs as well as you would like or maybe you would like to expand your activities to grow something different or grow your usual crops in different ways. Just maybe, you are looking forward to using a cold frame, building a low tunnel, or putting up trellises in 2015 but you don’t know much about those things. This winter would be a good time to set yourself on the path of self-directed education.

As you are wrapping up the gardening year, I hope you have recorded questions you might have had over the season. Maybe you have a crop that just never performs as well as you would like or maybe you would like to expand your activities to grow something different or grow your usual crops in different ways. Just maybe, you are looking forward to using a cold frame, building a low tunnel, or putting up trellises in 2015 but you don’t know much about those things. This winter would be a good time to set yourself on the path of self-directed education.

Having questions of your own is the best first step. Searching for the answers is the next. Observation in your own garden is a good place to start. I hope you have taken notes over the course of the gardening year about what puzzles you in the garden. Then, hit the books and see what others have to say. I know that people have become accustomed to searching the Internet and YouTube for information and I don’t mean to discount that. There is a lot of good information out there (including this blog) and there is a lot of not-so-good information. Pay attention to the source.

When I produced the cover crop and garden plan DVDs I had people like you in mind. The DVDs would be used in the classes I taught at the community college where they are still part of the curriculum, but are also available to anyone wanting to further their gardening education. Not everyone can fit a college class into their schedule, even if one was available to them. My DVDs can be used by individuals or with groups and can be watched over and over. They are a great way to bring everyone into the same understanding of the subject to start discussions.

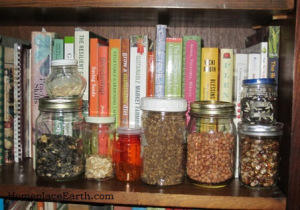

My book Grow a Sustainable Diet takes the garden planning and cover cropping further by including planning to grow a substantial part of your food and the cover crops to feed back the soil, while keeping a small footprint on the earth. In the first photo you see me working on that book. During the writing of each chapter I would get out books for reference and they would pile up beside my desk. When I finished a chapter, I would put the reference books away and start a new pile with the references for the next chapter. (By the way, I bought that wonderful desk at a church yard sale.) Whether I am writing a book, working on my garden plan, or researching something new I want to do in my garden, the scene is the same. I check the resources I’ve developed from my garden myself, refer to books on my shelf, refer to books from the libraries (I frequent several) and check out what is on the Internet.

Sometimes when I am learning about a new crop, or fine-tuning what I know about something I’ve been growing awhile, I will write a paper about it to put in my garden notebook. It would answer all the questions I have about that crop and include some ideas for the future. In the paper I document where I found the information in case I need to reference it later. If you were taking a class somewhere you would have to write papers—maybe on things you have no interest in. You are the director of your own education here, so all the papers you write for yourself are relevant and timely.

I learned to garden before the Internet was a thing. With a limited budget I learned from the experienced folks who wrote the books that I found at the library, primarily the ones published by Rodale Press in the 1970s and 80s. Then Chelsea Green came on the scene with New Organic Grower. Since then there have been many more good gardening books published, including the ones by my publisher, New Society. All the while I was reading those books, I was trying out the authors’ ideas and coming up with my own. The learning is in the doing. Get out in your garden and just do things. Encourage your library to stock the books you want to learn from. If you are going to buy them, try to buy from the authors themselves. Some good books are out of print, but thanks to the Internet, you can find them through the used book websites. Used book stores are some of my favorite places to shop. When you find something particularly helpful, buy it for your personal library. Put the books you would like on a Christmas Wish List. If someone asks you for suggestions, you will be ready.

I learned to garden before the Internet was a thing. With a limited budget I learned from the experienced folks who wrote the books that I found at the library, primarily the ones published by Rodale Press in the 1970s and 80s. Then Chelsea Green came on the scene with New Organic Grower. Since then there have been many more good gardening books published, including the ones by my publisher, New Society. All the while I was reading those books, I was trying out the authors’ ideas and coming up with my own. The learning is in the doing. Get out in your garden and just do things. Encourage your library to stock the books you want to learn from. If you are going to buy them, try to buy from the authors themselves. Some good books are out of print, but thanks to the Internet, you can find them through the used book websites. Used book stores are some of my favorite places to shop. When you find something particularly helpful, buy it for your personal library. Put the books you would like on a Christmas Wish List. If someone asks you for suggestions, you will be ready.

When the opportunity arises, go to programs and presentations that are offered in your community and regional conferences. Something might even pop up at your local library. This photo shows the publicity that the Washington County Seed Savers Library gave to their upcoming gardening programs in April 2014. There is a poster to show that I would be speaking there and a brochure that listed all the spring programs. These programs were free to the public!

When the opportunity arises, go to programs and presentations that are offered in your community and regional conferences. Something might even pop up at your local library. This photo shows the publicity that the Washington County Seed Savers Library gave to their upcoming gardening programs in April 2014. There is a poster to show that I would be speaking there and a brochure that listed all the spring programs. These programs were free to the public!

There will be a cost involved for conferences, but you can recoup that in the knowledge gained from the experience—and from the connections you make through the people you meet. Sometimes the best thing to do, especially if you are new at this, is to spend your time listening to what everyone has to say. You can even learn a lot listening to the discussions going on over lunch. I just returned from the Mother Earth News Fair in Topeka, Kansas. I enjoyed meeting people following my work and those who just discovered it. I also enjoyed spending time with other authors, editors, and the Mother Earth News staff. Although we email throughout the year, it is good to meet-up in person.

My next adventure is to attend Seed School in Buhl, Idaho both as a student and as a presenter on seed libraries. That’s where I’ll be when you receive this post on November 4, 2014. I am looking forward to sharing what I know and to learning from everyone else who is there. Take control of your own gardening education and plan to spend this winter learning wherever you can. Fill your garden notebook with your customized garden plan and with information specific to you.

October 21, 2014

My 10-Day Local Challenge Experience

In my last post I wrote about the 10-Day Local Food Challenge that I had decided to take on. Usually I write about growing food, but in reality, it begins with what we are eating. With each bite we take we have the opportunity to focus on a more local and sustainable diet, or not. Since my first garden in 1974 I have been putting homegrown food on our table. Not everything we eat is homegrown, but the amount has increased each year, along with my skills and experience in both growing and preparing it.

In my last post I wrote about the 10-Day Local Food Challenge that I had decided to take on. Usually I write about growing food, but in reality, it begins with what we are eating. With each bite we take we have the opportunity to focus on a more local and sustainable diet, or not. Since my first garden in 1974 I have been putting homegrown food on our table. Not everything we eat is homegrown, but the amount has increased each year, along with my skills and experience in both growing and preparing it.

The conversations about the challenge on Facebook bring to light the roadblocks some have experienced, such as the distance they have to travel to buy from a local farmer, even if it is within the 100 mile limit. The time it takes to plan and shop this way are obstacles that have been expressed. Also, even if eggs are found locally, what the chickens are eating may not have come from within 100 miles and very well might be GMO grains.

In 2000 I became concerned about GMOs in both my diet and the diet of my chickens, so I began to prepare my own chicken feed. At first I would buy corn from a local farmer and add oats from the feed store and organic wheat that I bought elsewhere. Once I stopped selling eggs I kept fewer chickens and no longer bought corn twelve bushels at a time from the farmer. That farm has since switched to GMO varieties. Now I buy organic grains–corn, wheat, and oats–from Countryside Organics, which is within 100 miles from here. I haven’t checked lately, but I’m sure not all the grain is grown within that limit. Nevertheless, I included eggs from my chickens in my local diet.

Mississippi Silver Cowpeas and Bloody Butcher Corn

In Grow a Sustainable Diet, I wrote that with a sustainable diet we would be eating less meat prepared in different ways. So, it is fitting that when I checked our freezer when I decided to take the challenge at the spur-of-the-moment, I found a package of chicken backs and a package of ground sausage. Although we have raised all our own meat in the past, now it is only the meat from our few young roosters and old hens that grace the table from our farm. I depend on the growers at the farmers market if I want more. This whole year has been a year of BUSY and my meat supplies were low. I cooked the chicken backs in a crock pot. There was enough meat to have chicken and gravy over mashed potatoes for a couple meals for my husband and I and chicken broth enough for potato soup for another couple meals. I had already used most of the Irish potatoes that had come from my garden this year, so was very happy when our daughter showed up with ten pounds from her garden. I made sausage gravy over mashed potatoes for another couple meals. Vegetables from the garden completed those meals. Vegetable soup was on the menu that week, as well as cowpeas with salsa. Homegrown Mississippi Silver cowpeas are a staple in my pantry. The salsa was some that I had put up from garden ingredients this summer.

As much as I enjoy growing our own food, I am happy for the farmers market to add variety. I bought some beef there and had pot roast for Sunday dinner when our son and grandson joined us at the table during the challenge. My homegrown corn provided cornbread and breakfasts of cornmeal mush over the ten days. I didn’t have a lot of wheat I’d grown in my garden this year, but I had some. That went into Saturday morning pancakes and the gravy I made with chicken broth and sausage. When I visit family in Ohio I buy maple syrup produced nearby and bring it back to Virginia. I counted that as a local product, not an exotic.

The exotics during my ten days were milk, butter, vinegar (to put on the kale, as a salsa ingredient, and to sour the milk for the pancakes in place of yogurt), salt, onions, baking powder, black tea, and whatever was added to the pork to make the sausage and bacon. We didn’t eat bacon during the ten days, but I cooked with bacon grease. The pork is grown locally on pasture, but also receives some grain. The farmers there are working toward eventually growing their own grain. The animals are processed within the 100 mile limit. The beef we ate was grassfed. I could have lived without the tea, since I also make tea from homegrown herbs.

The milk we consumed during the challenge could have been local, but it wasn’t. For seven years when our children were growing up we kept a milk cow, so I have experienced that. I participated in a milk share one year. When the farmer moved and sold her cows to another milk share I decided not to continue as a customer because too many distractions were creeping into my life to pick up the milk at a certain time each week. So, I understand how that is, also. With milk you can make butter, yogurt, and cheese.

String of onions.

Onions were included as an exotic because I was out of the ones I’d grown—or rather thought I was out. I found some later that week that had been a late harvest and were not in their usual place. With such a wet spring, I didn’t harvest as many onions as I had hoped to this year. Onions and garlic are really important for a healthy diet. We have plenty of homegrown garlic. There are not enough storage onions available at the farmers market and the garlic growers often run out of garlic before fall. If you are a producer, grow more storage onions and garlic for your customers.

I made “zucchini” bread with homegrown sorghum for the flour and some late butternut squash that wouldn’t have time to mature in the garden before frost. We had locally grown popcorn cooked in butter for a snack. I also snacked on homegrown peanuts. Having the community to rely on, not just my own garden as I did for Homegrown Fridays, really expanded our diet. Except for the salt and the additions to make pork into sausage and bacon, my exotics were not so exotic and could have been produced locally or at home, if necessary.

This challenge was a good assessment of how far I have come on this journey—and it has been a journey. Eating this way didn’t happen all at once. Of course, my children are grown now and I work from home, which makes a difference. However, that doesn’t mean that I have more time than anyone else to make this happen. We all have the same amount of time, we just use it differently. If your ultimate goal is to have a local/homegrown diet, begin eating that way as much as is possible in the situation you find yourself in at the time. If you aren’t growing enough food yourself yet, and can’t find local options, choose food to prepare that you could grow if you had the time, place, and skills to do so. Certainly, there are limitations in the marketplace that have not yet been adequately addressed, but often the biggest limitation is ourselves. If we change ourselves, the rest of the world changes around us.

October 7, 2014

10-Day Local Food Challenge

In early September I received an email newsletter from Vicki Robin, author of Blessing the Hands That Feed Us. It gave notice of the 10-Day Local Food Challenge that would begin in October. It sounded interesting and I was glad she was doing that, but I was over my head in work and barely had time to read the email, let alone act on it. I was away from home from September 12-23 and two more newsletters about the challenge arrived in my inbox during that time. I’m back now—at least until October 24 when I leave for the Mother Earth News Fair in Topeka, Kansas—and I am beginning to get caught up. Thinking the local food challenge would make a good topic for my blog, I took the time to look into it.

In early September I received an email newsletter from Vicki Robin, author of Blessing the Hands That Feed Us. It gave notice of the 10-Day Local Food Challenge that would begin in October. It sounded interesting and I was glad she was doing that, but I was over my head in work and barely had time to read the email, let alone act on it. I was away from home from September 12-23 and two more newsletters about the challenge arrived in my inbox during that time. I’m back now—at least until October 24 when I leave for the Mother Earth News Fair in Topeka, Kansas—and I am beginning to get caught up. Thinking the local food challenge would make a good topic for my blog, I took the time to look into it.

The guidelines of this challenge are to select 10 days in October 2014 when you will eat only food sourced within 100 miles or so from your home. You are allowed 10 exotics, which are foods not found in that target area. You can do it by yourself or get others to join you. You can make a formal commitment to this project by taking an online survey and joining the Facebook Group for the project. Or, you can only make a personal commitment if you don’t want to be public about it. That’s okay, but one of the reasons for this project is to gather information about our local food systems and come up with ideas about how to make them better. The survey results and the comments from the online community will help toward that end. If it turns out that you can’t fulfill your plan to do this, that’s okay, too. No one will come knocking at your door asking to see what is on your plate. It is an opportunity to learn more about what you eat and where it comes from. Maybe you can’t do it for the whole 10 days–so do it for 5 days–or 1 day. If you aren’t ready to make a commitment, but want to stay informed about the project, you can sign up through the website for that, too.

Dinner for Day 1-acorn squash, sauteed peppers and green tomatoes, kale, roasted radishes, watermelon.

The emails began arriving in early September to give participants an opportunity to begin preparing, but I was too busy to pay attention. With no preparation at all, I decided to jump into this and began my 10 days on Sunday, October 5. I say no preparation, but in reality I’ve been preparing for something like this for a long time. I have experienced my Homegrown Fridays when, during the Fridays in Lent, I only consumed what I had grown myself. No exotics allowed. This seems much easier than that. Sure, I have to stick to it for 10 days straight, but I have so many more options. On top of that, I have the luxury of 10 exotics!

Our dinner on October 5 included acorn squash, kale, and roasted radishes from Peacemeal Farm, homegrown peppers and green tomatoes sauteed in bacon grease that was saved another day when I cooked bacon from Keenbell Farm, and watermelon that I found hiding in the weeds when I cleaned up the garden. I made some cornbread that day from the recipe in The Resilient Gardener by Carol Deppe. The salt, butter, and baking powder that were required are on my list of exotics. The cornmeal and eggs were grown right here by me. This recipe requires no wheat. I already have jam made from local and homegrown fruit sweetened with homegrown honey.

Besides being an interesting challenge (and promising to be easier than Homegrown Fridays) I was also attracted to this challenge because I used to assign my students at J. Sargeant Reynolds Community College a project to contemplate what it would be like if the trucks stopped coming to the grocery stores. I told them at the start of the semester in late August that this would happen on January 1 and they needed to plan now to source their food for the next year from within 100 miles. We had many good discussions over that 100 Mile Food Plan project. They received extra credit if they marked circles on a highway map showing 25, 50, 75, and 100 miles from their home. Actually, just that act of putting the circles on the map was a real eye-opener for most. They began seeing all the possibilities, rather than limitations. If you don’t know where the sources are in your area for local food you can begin your search with www.localharvest.org.

Besides being an interesting challenge (and promising to be easier than Homegrown Fridays) I was also attracted to this challenge because I used to assign my students at J. Sargeant Reynolds Community College a project to contemplate what it would be like if the trucks stopped coming to the grocery stores. I told them at the start of the semester in late August that this would happen on January 1 and they needed to plan now to source their food for the next year from within 100 miles. We had many good discussions over that 100 Mile Food Plan project. They received extra credit if they marked circles on a highway map showing 25, 50, 75, and 100 miles from their home. Actually, just that act of putting the circles on the map was a real eye-opener for most. They began seeing all the possibilities, rather than limitations. If you don’t know where the sources are in your area for local food you can begin your search with www.localharvest.org.

Another attraction to the 10-Day Challenge is to put into practice what I wrote about in Grow a Sustainable Diet. In this book I show you how to plan a diet around homegrown and local foods, while at the same time planning to grow cover crops that will feed the soil. When your food comes from sources other than your garden, take the time to question the farmers who grew it about their soil building practices. It is great to do as much as we can for ourselves, but we don’t have to do everything ourselves. It is in joining with others in our communities that we gain strength and resilience for whatever the future holds.

I hope I have encouraged you to join the 10-Day Local Food Challenge. If you have been following my work and thought that Homegrown Fridays might be a bit too much to do, give this a try. To my former students, now is the time to update that plan you made years ago and act on it. To the current JSRCC sustainable agriculture students, this seems made to order for you. Put your plan into action! If circumstances prevent you from actually doing this now, at least begin to think about it. You could plan one meal, maybe with friends, with all the ingredients being homegrown or sourced locally. To those who have read my book, taking this 10-Day Local Food Challenge is an opportunity to reinforce what you have learned and expand your thinking. When you take the survey to join, there will be space to write additional information. Please take that opportunity to say that Cindy Conner sent you. That way they can track how people learned about he challenge. Best wishes to all who join this adventure!

When you take the survey to join, there will be space to write additional information. Please take that opportunity to say that Cindy Conner sent you. That way they can track how people learned about he challenge. Best wishes to all who join this adventure!

September 9, 2014

Cover Crops and Compost Crops

Use a machete to cut corn stalks into manageable lengths for the compost pile.

As you harvest the last of your summer crops, realize that the steps you take now are the beginning of next year’s garden. You could just leave everything as it is, looking not so good through the winter. Mother Nature likes to keep things green, so will provide her own seeds to fill in the space if you don’t. That’s where the unwanted weeds come from. The spent plants from your summer crops are actually valuable compost material at the ready. Harvest them for your compost pile as you clean up your garden. Next year this time the compost you make now will be available to spread as fertilizer for your garden. If you have grown corn and sunflowers, those stalks are wonderful sources of carbon for your compost. Some folks till all their spent plants, including cornstalks, into the soil. However, since I advocate managing your garden with hand tools, I chop the stalks down and cut them into manageable lengths with a machete, as shown in the photo. The cornstalks then go into the compost pile with all the other harvestable plants, plus some soil. You can see me in action chopping cornstalks and adding them to the compost in my DVD Cover Crops and Compost Crops IN Your Garden. When you look at the plants in your garden, make sure to recognize their value as a compost material.

Winterkilled oats in late February.

After you clean up the garden beds by harvesting compost material, you will need to plant cover crop seeds. If you have beds producing food through the winter, that’s great. It’s the rest of the garden I’m talking about. The crops you plant now will determine how each bed is to be used next year. If you intend to have bed space devoted to early season plantings, such as peas, lettuce, greens, and onions, you want the cover crops to be finished by then. Cereal rye, often called winter rye, is a great cover crop for winter. However, it is not so great if you are managing it with hand tools and you want to plant those early spring crops. The rye will have put down a tremendous amount of roots and be growing vigorously in early spring. Options to plant now in those beds destined for early spring crops are oats or Daikon radish, two crops that will winterkill if you get severe enough winter weather. Here in Virginia in Zone 7 we usually have weather that will cause these crops to winterkill, however I remember a few mild winters when they didn’t. I also remember a winter I planted oats in a bed that had compost piles on the bed just to the north of it. The compost provided enough protection to keep the oats growing into the spring.

If you choose the route of planting crops to winterkill, you need to get them planted early enough so that they have a chance to produce a large volume of biomass before the weather turns cold. If you don’t already have these crops in the ground, the time to plant them is NOW. Actually, anytime in the past three weeks would have been better. Another alternative for that space for early spring crops is to mulch it with leaves for the winter. The leaves will protect the soil over the winter and when you pull them back in early spring you will find a fine layer of compost where the leaves meet the soil. The worms would have been working on those leaves all winter. Pull the leaves back a couple weeks before you intend to plant to allow the sun to warm the soil.

This rye and vetch cover crop was cut at pollen shed (May 7) and will dry to become a mulch for the next crop.

You want a thick cover of plant growth with any cover crop. Planting at the right time will encourage that. The legumes, such as hairy vetch, crimson clover, and Austrian winter peas are often used as fall cover crops. It is best to get them in about a month before your last frost to ensure a good stand. That should encourage you to begin cleaning up the parts of your garden that have finished producing. Not all your garden beds will be host to the same cover crop, so you can do it bed by bed—an advantage over working on the whole garden at the same time. These legumes will begin to grow and will provide protection for the soil through the winter. In early spring they will take off, growing to their full capacity by the time of your last spring frost. You may have seen crimson clover flowering in garden beds at that time. You can cut this biomass with a sickle and add it to the compost pile. It would be a nitrogen component. You could lay it down as mulch right in the bed, but it would soon dissolve into the soil and not last as long as mulch that has more carbon. The advantage of the legumes is the nitrogen they leave in the soil from the nodules on their roots. If you should need the bed sooner than the date of your last frost, you could easily cut the legume a little early, leaving the roots. They are not so tenacious that you can’t plant into the bed soon after cutting.

The winter cover crop that will produce the most carbon for your compost and/or mulch is the rye that I mentioned earlier. It is also the crop that you can plant the latest into the fall and still have a good stand; making it a possible choice after things like tomatoes and peppers that produce until the first fall frost. You can let it grow to seed and cut it in early summer (mid-June here), giving you seed and mature straw. Or, you can cut it at pollen shed (about May 7 here) and leave it in the bed as mulch. Wait two weeks before planting to let the roots begin to die back. The bed would be suitable for putting in transplants, but not for seeds at that time. Often rye is planted with a legume. If you are planting late in the season, choose Austrian winter peas as a companion.

The information in my DVD Develop a Sustainable Vegetable Garden Plan and my book, Grow a Sustainable Diet, helps you to determine how to plan these cover/compost crops into your crop rotation. In the DVD you see me explaining a four bed rotation as I fill in the crop selections on a whiteboard. The book has three sample garden maps accompanied by explanations. The sample garden maps in the DVD and in the book have crops filling the beds for all twelve months of the year. Knowing how to fit enough cover crops in your garden plan to provide all of your compost and mulch material is definitely a skill that takes concentration and practice to learn. I hope the educational materials that I have produced will help many gardeners along that path. The most important thing is to just get started and plant something. Make note of your planting time and watch how it grows. The learning is in the doing.

August 26, 2014

Seed Libraries: Challenges and Opportunities

Those of you who have been following my work know that I have written the book Seed Libraries and Other Means of Keeping Seeds in the Hands of the People. We’ll call it Seed Libraries for short and you can expect it in the bookstores in early February. You can order it from New Society Publishers or buy a signed copy from me through my website when the time gets closer. In the past few years seed libraries have been popping up everywhere, evolving to fit their communities. It was this evolving that drove me crazy as I contacted all the places I mentioned in the book to make sure I had the most up-to-date information. As I polished the last details before sending the manuscript to the publisher, I got wind of a situation a new seed library in Pennsylvania was experiencing. The Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture (PA DOA) approached the Simpson Public Library to tell them that their new seed sharing program was not in compliance with the state’s seed laws. That was quite a surprise, since they were operating the way most seed libraries do and there were already established seed libraries in Pennsylvania that had no problems.

Those of you who have been following my work know that I have written the book Seed Libraries and Other Means of Keeping Seeds in the Hands of the People. We’ll call it Seed Libraries for short and you can expect it in the bookstores in early February. You can order it from New Society Publishers or buy a signed copy from me through my website when the time gets closer. In the past few years seed libraries have been popping up everywhere, evolving to fit their communities. It was this evolving that drove me crazy as I contacted all the places I mentioned in the book to make sure I had the most up-to-date information. As I polished the last details before sending the manuscript to the publisher, I got wind of a situation a new seed library in Pennsylvania was experiencing. The Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture (PA DOA) approached the Simpson Public Library to tell them that their new seed sharing program was not in compliance with the state’s seed laws. That was quite a surprise, since they were operating the way most seed libraries do and there were already established seed libraries in Pennsylvania that had no problems.

You have to be careful where you get your news from. There have been news reports about this that have headlines that are misleading and inflammatory. For the full story go to the Simpson Seed Library’s website. As far as I know, this is an isolated case. The seed laws that are being enforced are there to protect our population and govern seed sales. However, the wording has been interpreted by the PA DOA officials in that community to include any distribution of seeds. In order to comply with their requirements the seed library would have had to do extensive testing of donated seeds following the Association of Official Seed Analysts (AOSA) Rules for testing seed. Seed libraries find out sooner or later that they need to test some of their seeds for germination, but not like this. The AOSA rules are meant for seed companies and are beyond what is necessary for a seed library.

The Simpson Seed Library chose not to challenge this finding legally. It will continue to operate, but rather than have seeds that patrons bring in, they will only stock seeds that have been commercially packaged for the current year and encourage patrons to take the seeds, grow them out, and exchange them among themselves at the seed swaps that the library will host. The same seeds will be changing hands within the walls of the library that would have been made available through the seed library. I guess how that is different would be a matter of interpretation. I imagine that if this happens in other localities, eventually it will be challenged in court. But, so far, it is not happening elsewhere. People are free to share their seeds through seed libraries all over the country.

Red Sails lettuce on June 7.

Seed libraries are not seed companies, which the seed laws are called to regulate. Patrons of seed libraries participate in these seed sharing opportunities for many reasons including; preserving varieties that grow best in their area, preserving genetic diversity, preserving flavor and nutrition, and preserving cultural heritage. They know that the seeds at the seed library don’t necessarily meet the legal germination rate, although often they could well exceed it. The amount of seed exchanged is so small that if there were any unwanted seeds present, such as noxious weeds, those seeds could be easily identified and expelled from the batch. The chance that seed is not true-to-type is greater if acquired from amateur seed savers than if bought from a reputable seed company. That’s the chance you take when you get free seeds from a seed library. Our seed laws help protect us from seeds with low germination, noxious weeds, and seeds that are not as advertised, that we buy from seed companies.

The same patch of lettuce growing to seed on July 5.

Seeds are an adventure and that’s what seed library patrons are looking for. They want to try their hand at seed saving and possibly seed breeding; preserving heritage varieties and developing new ones for their communities. In that case, plants not true-to-type might lead the way to new varieties. That’s the way it was done down through the ages before seed companies came into being.

Patrons of seed libraries want to explore everything about the plants they are growing. You really get to know a plant if you watch it all the way to seed. Seed saving is a skill that will need to be developed and public libraries are one of the best places to go for help. Whether a public library offers seeds or not, it can still offer lots of resources to help patrons. The most obvious are through books and computer access. However, libraries have programs and meeting spaces that bring people together and, in my mind, that is just as important. There can be programs about the specifics of seed saving, about meeting seed savers and hearing their stories, and about indigenous food and why it is special to the area. Seed libraries could loan seed screens to their patrons or have community seed threshing gatherings where the education shared is as important as the seed harvest.

Red Sails lettuce flowers and seed pods on July 28. The seeds are in the pods under the white puffs.

Book discussions, which are already common at public libraries, could include titles about the food system and related topics. Gardens, no matter how small, could be planted with a seed harvest in mind and have signs documenting what is happening. Patrons could celebrate seeds with music, art, and photography. Libraries could have exhibits with photographs of plants going to seed so the patrons, and the public, can learn what to look for. Some people may think plants are abandoned and messy, but with a little awareness, will see the beauty of watching and waiting for the seeds to be ready to harvest. Most people would recognize lettuce in a garden, but would they recognize it grown to seed and know when the right time to harvest it would be?

The Simpson Seed Library will only have commercially packaged seeds in their cabinet. Since these seed varieties will funnel into the seed swaps they are planning, the staff will need to monitor what packets are donated—an opportunity to educate patrons about open pollinated vs. hybrid seeds and seed companies who have signed the Safe Seed Pledge to not knowingly carry any GMO seeds. A list of approved seed companies might be in order to keep the donation basket from filling up with hybrid seeds from the racks of the big box store down the street.

Even if a public library always has seeds available in a cabinet for their patrons, it can (and should) host a seed swap annually or seasonally to celebrate seeds. Regular public library patrons who have no interest in seeds will come to realize that they are important, just by observing the attention paid to them. I hope you will consider being part of this adventure in your community.

August 12, 2014

Determining Days to Maturity

Provider bush beans

When you are planning your garden you need to plan when your harvest will begin. You don’t want to be off on vacation when the beans are ready to be picked. If you need the harvest by a certain date, knowing the days to maturity will help you decide on your planting date. It is good to know the length of harvest, also. Some crops will be picked all at once and some will be picked over a matter of weeks. My garden planning skills were put to the test this year as we planned for another wedding. Our youngest son, Luke, married the love of his life, Stephanie, on August 2. I was to provide the snap beans, lettuce, garlic, and some of the flowers. Stephanie and our daughter, Betsy, were growing the rest of the flowers. Stephanie and Luke grew all the potatoes and some of the other veggies, such as zucchini, and Betsy grew the cabbage that became the coleslaw for the wedding feast.

Normally, planning snap beans for an event is no problem for me. I like to plant Provider, a tried-and-true early variety. The problem is, when I sat down with the Plant/Harvest Schedule to chart when to plant and when to expect a harvest, the date I wanted to plant the Provider beans was right after we would be getting back from a week-long trip. That would be the trip to the Mother Earth News Fair in Puyallup, Washington and to Victoria, British Columbia. I did not want to worry about making sure I got that planting in. If something happened that delayed my time in the garden upon our return, I would have missed my window of opportunity. I was going to have to reach out of my comfort zone and plant another variety.

I checked the seed catalogs for a variety that took a week longer than Provider to mature. High Mowing listed Provider at 50 days and Jade at 55 days. I remember a market grower friend commenting favorably about Jade at one time, so I ordered Jade. I thought it would be good to grow some yellow wax beans, also, since the wedding colors were green and yellow. It had been a long time since I grew wax beans, but I remembered them to take longer to mature and were usually curled when I grew them in my market garden. High Mowing listed Gold Rush Yellow Wax beans with the same 55 days to maturity as Jade and they were straight beans; just what I was looking for. The Jade and Gold Rush beans were planted on May 29, the day before we left on the trip.

Provider may be listed at 50 days, but I usually begin harvesting six weeks (42 days) after planting and harvest over a two week period, with a little smaller harvest for the first and last pickings, but the yield is generally spread out. In Grow a Sustainable Diet, I encourage you to grow for yourself and learn the ins-and-outs of the crops and varieties before you grow to sell to others. Knowing the ins-and-outs of the varieties is important. At 47 days after planting, the Gold Rush beans were ready and I picked about two-thirds of the total harvest that day. Now that I look back at the seed catalog, I see that “concentrated harvest period” was in the description for Gold Rush. Luckily the caterer was willing to take the vegetables early. I also harvested some of the Jade beans that day. At 54 days after planting I harvested two-thirds of what would be the total harvest for the Jade beans. The last harvest of both varieties was at 58 days.

Since the caterer didn’t mind the vegetables arriving early, it all worked out. For Betsy’s wedding four years ago, our friend Molly catered the event and the harvest was more closely planned; vegetables arriving early would have been a big inconvenience. Even though the days to maturity are listed in the seed catalog or on the packets, it is only an approximate time. Learn what the days to maturity are in your garden for the varieties you choose. Have at least one variety of each crop that you can use to compare new varieties to, such as I did with Provider beans. Make a note of the length of harvest and nuances, such as matures all at one time, color, shape (curled beans or straight), and any other characteristics that might be important some day. This information will be extremely helpful to you if you needed to grow food for a certain event; and certainly if you needed to satisfy customers.

Growing both colors of beans again made me want to include that in my plan for next year. My signature dish is a cold bean salad. I include cowpeas that I always have as dried beans in the pantry and green beans which are either fresh from the garden or canned. To that I add anything I can think of from the garden and a vinaigrette. I used some of the Gold Rush beans in the bean salad that I made for the rehearsal dinner. I believe next year I will can green and yellow beans together especially to have on hand for the bean salad. I was able to put up some of the extra this year.

Growing both colors of beans again made me want to include that in my plan for next year. My signature dish is a cold bean salad. I include cowpeas that I always have as dried beans in the pantry and green beans which are either fresh from the garden or canned. To that I add anything I can think of from the garden and a vinaigrette. I used some of the Gold Rush beans in the bean salad that I made for the rehearsal dinner. I believe next year I will can green and yellow beans together especially to have on hand for the bean salad. I was able to put up some of the extra this year.

Flowers are not my specialty, but the bride wanted zinnias and they are easy to grow and a sure thing to have in August. Stephanie likes puffy flowers and chose Teddy Bear sunflowers, in addition to the zinnias. It is usually hard to find days to maturity for flowers, but these were listed as maturing at 60 days. I didn’t want to plant them too early and miss the blooms for the wedding. Unfortunately, I waited a little too long. They didn’t begin blooming until a few days after the wedding. Not to worry, there were many more things in the yard blooming that we could add, including black-eyed Susans, tansy, and Rose of Sharon, that we hadn’t planned on. Stephanie had two sunflowers ready by August 2 and the rest of her planting bloomed while they were on their honeymoon. Besides the happy bride and groom, in the photo you can see Stephanie’s bouquet, the table centerpieces with flowers, and their dinner plates full of homegrown food.

Flowers are not my specialty, but the bride wanted zinnias and they are easy to grow and a sure thing to have in August. Stephanie likes puffy flowers and chose Teddy Bear sunflowers, in addition to the zinnias. It is usually hard to find days to maturity for flowers, but these were listed as maturing at 60 days. I didn’t want to plant them too early and miss the blooms for the wedding. Unfortunately, I waited a little too long. They didn’t begin blooming until a few days after the wedding. Not to worry, there were many more things in the yard blooming that we could add, including black-eyed Susans, tansy, and Rose of Sharon, that we hadn’t planned on. Stephanie had two sunflowers ready by August 2 and the rest of her planting bloomed while they were on their honeymoon. Besides the happy bride and groom, in the photo you can see Stephanie’s bouquet, the table centerpieces with flowers, and their dinner plates full of homegrown food.

The wedding was wonderful. It took some planning to have the produce ready at the right time, but the more you do that, even for your own dinner table, the easier it gets. If something comes up, such as the trip for us, you will have the skills and knowledge to take it in stride. I hope your garden is producing well and that you are finding time to share it with others this summer.

July 29, 2014

Malabar Spinach

Red Malabar Spinach

Malabar spinach is the plant to grow to fit the niche for “summer greens” in your garden. I grow kale and collards through the winter for greens to harvest fresh for our dinner table from fall to spring, but they don’t do well in hot weather. Neither does regular spinach, which likes the same cool temperatures as kale and collards. Despite its name, Malabar spinach (Basella alba or Basella rubra) is not related to regular spinach (Spinacia oleracea).

I first saw Malabar spinach growing in my daughter’s garden. She only had a few plants and they were crawling prolifically along the top of a fence that supported other crops. It was abundant, provided a cooking green for summer meals, and was colorful with its glossy green leaves and red stems. Last year when I put up the trellises over my paths I thought that was just the thing to try there. (You can read about those trellises I made from livestock panels at http://homeplaceearth.wordpress.com/2013/10/08/trellis-your-garden-paths/. )

Green Malabar Spinach

When ordering seeds in early 2013, I saw Malabar spinach offered in a seed catalog and ordered it. What I didn’t know is that there are two types of Malabar spinach. What I bought was green Malabar (Basella alba). What I was anticipating was red Malabar (Basella rubra). My 2013 crop of Malabar spinach had thick green stems and didn’t climb well. In fact, it was slow to grow at the beginning of the summer. Later in the summer it was abundant, but it never grew as tall as the red variety. I’ve had the pleasure of taking a sneak peek at David Kennedy’s upcoming book Eat Your Greens: the surprising power of homegrown leaf crops, published by New Society and due to be in the bookstores about October 1. Kennedy, who refers to this crop as vine spinach, says the red variety produces best in early to mid summer and the green variety produces best in late summer to fall. Both varieties will succumb to frost. That explains why not much was happening with my Malabar spinach early in the summer last year when I was anxious to have it take off up the trellis.

Red Malabar spinach on a trellis.

This year I am growing the red variety of Malabar spinach and am pleased with it. I planted the seed at the base of both sides of my trellis, but something happened to keep it from growing on one side. Many things this summer have kept me distracted and failing to replant when necessary, so that side never got replanted. The side that it is growing on looks great! I can pick the leaves from a standing position as I walk through my garden, harvesting this and that for dinner. Those red stems are edible, also. The path between two sections in my garden is behind the climbing spinach you see in the photo. As you can see, it climbs the trellis well, providing shade to the path, and is colorful. I just have to smile when I see it. If I would have given this crop any attention at all, other than putting the seeds in the ground one time, I would have had Malabar spinach coming up over the top of the trellis from the other side.

My friend Brent tells me that it reseeds readily, so to expect volunteers to pop up next year. In his book, David Kennedy says the red variety will do that, but the green variety often flowers too late to produce viable seed before frost. Malabar spinach is an easy-to-care-for crop in my garden. The only attention I have given it is to redirect the vines to the trellis when they stray into the path. This crop doesn’t have the tendrils to reach out and grab the trellis that squash plants have.

If you want to add a tasty addition to your garden that thrives in hot weather, I encourage you to plant Malabar spinach.