Morgan Bolt's Blog, page 3

February 15, 2018

Gun Control

I’m not aware of anybody who thinks private ownership of nuclear warheads is protected by the Second Amendment. I also don’t know of anyone who wants to ban antique smooth-bore muskets. That’s probably because a single nuclear detonation in a major city could kill hundreds of thousands of people. A musket, not so much. So while the ongoing shouting match about gun control is often presented by gun control opponents as an unprecedented, all-out attack on the Second Amendment, the truth is we all understand and accept that the average citizen of the United States should not in fact have the right to bear any and all kinds of weapons indiscriminately.

Gun control is really just a part of broader weapons regulations that we already have. It boils down to a question of how many people can you kill with a given weapon, and how quickly and easily. If we frame the discussion like that, I think and hope we’ll get a very different kind of debate, especially from those who declare themselves ‘Pro-Life.’ But I’m not going to hold my breath.

Published on February 15, 2018 09:10

February 13, 2018

Ash Wednesday

I used to love Ash Wednesday, before I got cancer. Ash Wednesday always stood out to me as special. Apart from Good Friday, it’s pretty much the only day in the church calendar when not all is warm fuzzies and joy eternal. Ash Wednesday is sad. Ash Wednesday is real. It’s one of those very rare occasions when church not only allows us to be a little sad, but in fact encourages it.

I always loved that, because life is profoundly sad sometimes. People die. We all will die someday, every single one of us. We don’t remember that enough, and Ash Wednesday gives us an important reminder of the frailty and futility of material pursuits. Ash Wednesday is also a day in which pretenses of well-being are set aside and it’s alright to be flawed and mortal. On Ash Wednesday, Christianity can’t be abused to make false promises of health and wealth and every good thing in this life. On Ash Wednesday, we’re encouraged to remember that life is fleeting. I think that’s great.

I just don’t personally feel much of a need for it anymore.

I know I’m made of all-too fragile dust. I’m well aware that I’ll return to such before long. I haven’t been to an Ash Wednesday service since I got diagnosed over three years ago. Partly by default, since I’ve just not always been well enough to go to one, and partly I just haven’t wanted to.

If you know my story, you’d probably expect me to talk about my scars and how I don’t need ashes imposed upon my forehead to bear a physical reminder of my mortality. And that’s a good guess; I have over a dozen scars from various surgeries, after all. While they are pretty visible, and while they do remind me how close to death I have been and likely still am, I honestly just don’t notice them that much anymore. I’ve grown so used to them that every so often they genuinely surprise me.

Instead, how I feel is a much more brazen reminder of my mortality. Right now, I’m tired. I’m fatigued. I get light-headed and out of breath really, really easily. When my blood counts are down like they were this past weekend, I have to beware what I eat, who I’m around and if they’re vaccinated and healthy, and how often I wash my hands. Now, as my blood counts recover, I feel a deep aching in my bones as my marrow kicks back into gear. It’s not too intense, but it’s there, enough that I can say with reasonable certainty that my counts are recovering before my bloodwork results come in.

There are plenty of other non-physical reminders too. Heck, I wrote this post in the waiting area at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Pediatric Day Hospital, surrounded by a dozen other cancer patients, most of whom are younger than me. At the time I’m posting this, I’m waiting for the results of yesterday’s PET scan to know what the cancer in me has been up to these last couple months of chemo and immunotherapy. The days in which I feel well enough that I don’t experience multiple physical reminders of my cancer and the parade of treatments I’ve made it through are rare enough that they stand out to me and are themselves reminders too. So I’m intimately and intensely aware that we’re all dying one day at a time. And I could go into a dozen more ways my body sometimes feels like it’s slowly dying because of my cancer and the treatments I’ve needed for it—like mild neuropathy in my hands and feet or the many changes to my intestinal fortitude over the last few years—but you probably get the idea already. In short, each day provides multiple reminders that I’m mortal, that I’m dust. I walk through the Valley of the Shadow of Death every single day, one way or another.

If that’s true for you, then you probably understand why I don’t feel a need to spend an hour at a church service contemplating my impending death. I live that reality often enough as it is. But if you don’t—if your body’s wellness allows you to forget your mortality, your frailty, your dustiness—then try an Ash Wednesday service. I can’t imagine going through life without an awareness and appreciation of the fleeting nature of life. I wouldn’t want to take living for granted, forgetting to actually live while I can and postponing the important for a tomorrow that may not dawn. I’d rather know that I’m made of dust, and to dust I will soon return.

Published on February 13, 2018 06:57

February 6, 2018

Don't Tell People How to Be

This afternoon I overheard a conversation between someone heading to New York City for medical treatment on the same plane as me and what appeared to be a family member or close friend of theirs. It was the kind of exchange I’ve seen and been part of too often the last three-plus years of my own cancer treatment.

“Stay strong; stay positive,” said the friend or family member.

The apparent cancer patient next to me grunted (in annoyance?) before simply saying “bye.”

Maybe they didn’t feel well and weren’t up for speaking more. Or maybe they felt like I do when people offer what they think is helpful advice or encouragement, but it happens to be about the worst thing you could say at that moment.

And, for me at least, the words “stay strong; stay positive" are at literally any moment more likely to piss me off than give me life. I know, it seems like I’m overreacting. And I am. I know people mean well. I understand that it’s impossible to know what to say to someone going through something you’ve never experienced. So when I hear “encouragements” like this, I usually don’t press the issue. I usually just ignore these kinds of annoying phrases and remind myself that it’s the thought that counts. But people should also want to know if they’re unwittingly hurting more than helping. And for whatever it’s worth, I find the imperative “stay strong; stay positive” deeply unhelpful.

It’s a phrase that assumes weakness and negativity. Telling me to stay positive when I'm already doing precisely that feels patronizing. I’m already being as positive as I can be. I don’t need to be told to stay positive, and I don’t need your pity and assumptions that I’m not, just because you don’t think you would be in my situation.

Imploring people to “stay strong; stay positive” also assumes that just telling someone to be a different way is somehow helpful and will enable them to be that different way. Suppose I am having a gloomy day or I’m feeling negative this week. What do you really expect?

Me: *is gloomy*You: "Stay positive!"Me: *magically isn't gloomy anymore*

Maybe this is a realistic outcome for some people, but I don’t know any of them. So don’t tell me how to be. I don’t need your opinion on the best attitude to have in my situation.

Instead, say things like "keep it up. I hope it goes well. Good luck. Thinking of you. Praying for you," if you're a praying person and they're someone who appreciates prayer. You can also acknowledge that life isn’t all positive without projecting your own emotions onto someone else. Depending on how close you are to the person, it's probably a lot more OK than you think to say "I'm sure it'll be tough, and I hope it goes as smoothly as possible".

It's alright to recognize that an upcoming surgery or another round of chemo won't be easy and might be impossible to stay positive during. In fact, it's a lot better than pretending everything is positive, everyone is strong, and forgoing real, honest relationships in favor of cheap platitudes and hollow encouragements.

x

“Stay strong; stay positive,” said the friend or family member.

The apparent cancer patient next to me grunted (in annoyance?) before simply saying “bye.”

Maybe they didn’t feel well and weren’t up for speaking more. Or maybe they felt like I do when people offer what they think is helpful advice or encouragement, but it happens to be about the worst thing you could say at that moment.

And, for me at least, the words “stay strong; stay positive" are at literally any moment more likely to piss me off than give me life. I know, it seems like I’m overreacting. And I am. I know people mean well. I understand that it’s impossible to know what to say to someone going through something you’ve never experienced. So when I hear “encouragements” like this, I usually don’t press the issue. I usually just ignore these kinds of annoying phrases and remind myself that it’s the thought that counts. But people should also want to know if they’re unwittingly hurting more than helping. And for whatever it’s worth, I find the imperative “stay strong; stay positive” deeply unhelpful.

It’s a phrase that assumes weakness and negativity. Telling me to stay positive when I'm already doing precisely that feels patronizing. I’m already being as positive as I can be. I don’t need to be told to stay positive, and I don’t need your pity and assumptions that I’m not, just because you don’t think you would be in my situation.

Imploring people to “stay strong; stay positive” also assumes that just telling someone to be a different way is somehow helpful and will enable them to be that different way. Suppose I am having a gloomy day or I’m feeling negative this week. What do you really expect?

Me: *is gloomy*You: "Stay positive!"Me: *magically isn't gloomy anymore*

Maybe this is a realistic outcome for some people, but I don’t know any of them. So don’t tell me how to be. I don’t need your opinion on the best attitude to have in my situation.

Instead, say things like "keep it up. I hope it goes well. Good luck. Thinking of you. Praying for you," if you're a praying person and they're someone who appreciates prayer. You can also acknowledge that life isn’t all positive without projecting your own emotions onto someone else. Depending on how close you are to the person, it's probably a lot more OK than you think to say "I'm sure it'll be tough, and I hope it goes as smoothly as possible".

It's alright to recognize that an upcoming surgery or another round of chemo won't be easy and might be impossible to stay positive during. In fact, it's a lot better than pretending everything is positive, everyone is strong, and forgoing real, honest relationships in favor of cheap platitudes and hollow encouragements.

x

Published on February 06, 2018 20:31

January 30, 2018

I'm Believable

There’s a good chance you saw a story recently about Serena Williams and a frightening experience she endured last year, facing life-threatening blood clots shortly after giving birth. It’s a story that has sparked fresh disagreements about the many ugly facets of racism entrenched in so many of our systems, and it’s one I’ve thought a lot about the last couple of weeks.

For those who haven’t heard, I’ll give a quick version: The day after her emergency C-section she became suddenly short of breath and suspected, due to her history of blood clots, a pulmonary embolism. She asked for a CT scan and heparin drip but was given an ultrasound instead. It revealed nothing, and only after advocating for herself repeatedly got did she get the medical care she needed: the CT scan and heparin drip she had been asking for.

My first reaction on seeing this story was to shrug.

It just felt very familiar to me, and I'm sure it didn't seem all that unusual to many who have spent a good deal of time in a hospital setting. Medical professionals constantly have to judge whether a patient knows what’s going on in their body and can be trusted, or if they exhibit hypochondria or have spent too much time on WebMD. That’s not an easy assessment. And I think most people can agree that if there’s any doubt, it’s better for medical professionals to follow protocol and go with what they suspect, rather than follow what a patient thinks they know.

I’ve been through a couple similar episodes. I’ve asked for more hydration, well beyond what I should need for my height and weight, and not gotten it until there was a shift change and I had different people in charge of my IVs. I’ve also asked to have my hydration slowed and gotten a 2 liter bolus instead, based on the numbers of my urine output rather than how I was feeling. I gained a bunch of water weight and my legs swelled up significantly. I’d still prefer the people caring for me to follow established protocols, rather than pay too much heed to my semi-coherent ramblings when I’m on multiple painkillers and do the wrong thing because I thought I had a hunch about what I needed. To an extent, these kinds of events are inevitable and will always be a part of medical care.

So I truly understand where people are coming from when they dismiss Serena Williams’ story as an anecdote that could happen to anyone, rather than an example of racism at work in our healthcare system. I was tempted to agree at first. It is an anecdote. These types of events do happen to anyone. They always will to some degree.

Then I thought about this story for a minute.

Enough anecdotes pooled together can point to statistics. Sobering statistics, like the fact that black women are three to four times more likely to die from childbirth than white women in this country. We can debate why that is, talk about risk factors, discuss the systemic racism that contributes to these risk factors, and probably argue over a host of other topics related to this that I, a white male, am terribly unaware of. The fact remains that Serena Williams was very nearly another statistic, another black women who died from childbirth, and at least in part because she was not listened to.

So was Serena Williams not listened to because of racism, as many suggest? Honestly, I don’t know. It’s certainly suspect that a top-tier professional athlete—someone who doubtless has extremely well-developed bodily awareness—wasn’t listened to more. I have a hard time imagining Tom Brady being ignored by his doctors. It strikes me as suspicious that someone with a history of blood clots wasn't heeded more, too. But I wasn’t there. I don’t know all the circumstances around this story. I don't know the doctors, nurses, and others responsible for her care, and I don’t know what the protocols are for C-sections or post-surgical blood-thinner regimens for people with histories of blood clots.

But I do absolutely believe that, when medical professionals make their judgements of whether or not to believe a patient—whether a patient knows what they’re talking about or should be ignored in favor of following protocol—race plays a role. I don’t doubt for a second that black women are, as a whole, listened to less than, say, white men. This is true whether or not Serena Williams was herself a victim of racism following her C-section, and it is true whether or not such events happen to other people. As I said already, I’ve had a couple experiences in over three years of treatment when I was not listened to initially and advocated for myself several times before I finally got what I needed.

And yet I’ve had only two such instances that I remember. In over three years. I’ve also been believed hundreds of times in that same period, for relatively minor issues like hydration and a host of other, more serious matters. Like the time the space surrounding my lungs filled with over two liters of fluid and I could hardly breathe, and I said I had fluid that needed to be drained, and they drained it as soon as possible.

I don’t doubt for a second that my being a white male makes me more believable in the eyes of many people, medical professionals included.

For those who haven’t heard, I’ll give a quick version: The day after her emergency C-section she became suddenly short of breath and suspected, due to her history of blood clots, a pulmonary embolism. She asked for a CT scan and heparin drip but was given an ultrasound instead. It revealed nothing, and only after advocating for herself repeatedly got did she get the medical care she needed: the CT scan and heparin drip she had been asking for.

My first reaction on seeing this story was to shrug.

It just felt very familiar to me, and I'm sure it didn't seem all that unusual to many who have spent a good deal of time in a hospital setting. Medical professionals constantly have to judge whether a patient knows what’s going on in their body and can be trusted, or if they exhibit hypochondria or have spent too much time on WebMD. That’s not an easy assessment. And I think most people can agree that if there’s any doubt, it’s better for medical professionals to follow protocol and go with what they suspect, rather than follow what a patient thinks they know.

I’ve been through a couple similar episodes. I’ve asked for more hydration, well beyond what I should need for my height and weight, and not gotten it until there was a shift change and I had different people in charge of my IVs. I’ve also asked to have my hydration slowed and gotten a 2 liter bolus instead, based on the numbers of my urine output rather than how I was feeling. I gained a bunch of water weight and my legs swelled up significantly. I’d still prefer the people caring for me to follow established protocols, rather than pay too much heed to my semi-coherent ramblings when I’m on multiple painkillers and do the wrong thing because I thought I had a hunch about what I needed. To an extent, these kinds of events are inevitable and will always be a part of medical care.

So I truly understand where people are coming from when they dismiss Serena Williams’ story as an anecdote that could happen to anyone, rather than an example of racism at work in our healthcare system. I was tempted to agree at first. It is an anecdote. These types of events do happen to anyone. They always will to some degree.

Then I thought about this story for a minute.

Enough anecdotes pooled together can point to statistics. Sobering statistics, like the fact that black women are three to four times more likely to die from childbirth than white women in this country. We can debate why that is, talk about risk factors, discuss the systemic racism that contributes to these risk factors, and probably argue over a host of other topics related to this that I, a white male, am terribly unaware of. The fact remains that Serena Williams was very nearly another statistic, another black women who died from childbirth, and at least in part because she was not listened to.

So was Serena Williams not listened to because of racism, as many suggest? Honestly, I don’t know. It’s certainly suspect that a top-tier professional athlete—someone who doubtless has extremely well-developed bodily awareness—wasn’t listened to more. I have a hard time imagining Tom Brady being ignored by his doctors. It strikes me as suspicious that someone with a history of blood clots wasn't heeded more, too. But I wasn’t there. I don’t know all the circumstances around this story. I don't know the doctors, nurses, and others responsible for her care, and I don’t know what the protocols are for C-sections or post-surgical blood-thinner regimens for people with histories of blood clots.

But I do absolutely believe that, when medical professionals make their judgements of whether or not to believe a patient—whether a patient knows what they’re talking about or should be ignored in favor of following protocol—race plays a role. I don’t doubt for a second that black women are, as a whole, listened to less than, say, white men. This is true whether or not Serena Williams was herself a victim of racism following her C-section, and it is true whether or not such events happen to other people. As I said already, I’ve had a couple experiences in over three years of treatment when I was not listened to initially and advocated for myself several times before I finally got what I needed.

And yet I’ve had only two such instances that I remember. In over three years. I’ve also been believed hundreds of times in that same period, for relatively minor issues like hydration and a host of other, more serious matters. Like the time the space surrounding my lungs filled with over two liters of fluid and I could hardly breathe, and I said I had fluid that needed to be drained, and they drained it as soon as possible.

I don’t doubt for a second that my being a white male makes me more believable in the eyes of many people, medical professionals included.

Published on January 30, 2018 14:41

January 22, 2018

Prejudicial Awareness

I’m back on some pretty intense chemotherapy now. It tends to weaken people’s hearts, so I can only have one more round of it before I reach my lifetime limit. I also need to have an echocardiogram before I start each round to make sure my heart is doing alright. So far it’s been fine, but it’s best to be prudent. My hair is pretty much gone now too. It’s not exactly the ideal time of year to go bald and I didn’t realize just how insulating my beard was until I lost it, but it’s alright. I’m really not having too serious or debilitating of side-effects right now, and I know all too well that it could be much worse, so I won’t complain.

Now that I’m bald again, I look like a proper cancer patient. Anyone who looks at me could pretty easily make that judgement. This wasn’t the case last year, even though I had a bunch of chemo, an experimental clinical trial, and a handful of surgeries in 2017. None of it took my hair though, so you wouldn’t have judged me as a cancer patient on looks alone. And you’d have been very wrong.

That’s ok. It really didn’t do me any harm.

That’s just not the case with a lot of judgements. It’s not the case when judgements are informed by prejudice and it’s especially not the case when judgements informed by prejudice are accompanied by an imbalance of power.

Now, it’s impossible not to hold prejudices. It’s difficult to even become aware of all our prejudices, much less rid ourselves of them entirely. It’s also impossible not to make judgements based on appearances. I’m not even convinced that it would be entirely beneficial were it possible. Judgements about whether or not others appear like they could use a helping hand aren’t exactly terrible. Not all the time, at least.

That’s why we need to become more aware of our prejudices. We need to acknowledge when prejudices misinform our thinking so we can combat them and change our outlook. We need to be vigilant against ourselves, to take a step back and rethink everything when we realize we allowed prejudice to alter our view of the world or others. And we need to humbly listen when other people try to make us aware of our prejudices. Claiming reflexively to be the least-prejudiced, least-racist, or least-biased person around just reveals how little we understand these issues. Let's all stop being so offended by charges of racism, prejudice or bigotry, and start being more offended by these things themselves.

Now that I’m bald again, I look like a proper cancer patient. Anyone who looks at me could pretty easily make that judgement. This wasn’t the case last year, even though I had a bunch of chemo, an experimental clinical trial, and a handful of surgeries in 2017. None of it took my hair though, so you wouldn’t have judged me as a cancer patient on looks alone. And you’d have been very wrong.

That’s ok. It really didn’t do me any harm.

That’s just not the case with a lot of judgements. It’s not the case when judgements are informed by prejudice and it’s especially not the case when judgements informed by prejudice are accompanied by an imbalance of power.

Now, it’s impossible not to hold prejudices. It’s difficult to even become aware of all our prejudices, much less rid ourselves of them entirely. It’s also impossible not to make judgements based on appearances. I’m not even convinced that it would be entirely beneficial were it possible. Judgements about whether or not others appear like they could use a helping hand aren’t exactly terrible. Not all the time, at least.

That’s why we need to become more aware of our prejudices. We need to acknowledge when prejudices misinform our thinking so we can combat them and change our outlook. We need to be vigilant against ourselves, to take a step back and rethink everything when we realize we allowed prejudice to alter our view of the world or others. And we need to humbly listen when other people try to make us aware of our prejudices. Claiming reflexively to be the least-prejudiced, least-racist, or least-biased person around just reveals how little we understand these issues. Let's all stop being so offended by charges of racism, prejudice or bigotry, and start being more offended by these things themselves.

Published on January 22, 2018 17:22

December 23, 2017

Advent Reflections

Both of my Advent reflections for Unfundamentalists are online now; you can read them here.

Published on December 23, 2017 08:59

December 20, 2017

Advent Reflection for Unfundamentalists

Recently I wrote a pair of Advent reflections for Unfundamentalists.com and the first one is now live. You can find it here. I'll post another update here on my blog when the second goes live. Both of these Advent reflections draw from subject matter I cover in my book "Cancer is not Evil," for which I am still seeking a literary agent and/or publisher...

Published on December 20, 2017 05:20

December 13, 2017

Open Letter to Representative Mo Brooks

I learnedthis evening that Representative Mo Brooks has been diagnosed with prostate cancer. What follows is my open letter to him, from one cancer patient to another.

Dear Representative Brooks,

First, I want to wish you all the best. Cancer is an horrific disease that I wish nobody had to endure. I hope and pray that you make a full and prompt recovery from your upcoming surgery, attain ‘No Evidence of Disease’ status, and stay cancer free for many years to come. May all your treatments go smoothly, may your insurance cover every mode of treatment you need, and may you experience minimal complications from this disease so that it disrupts your life as little as possible.

Second—in the spirit of full honesty—I must admit that my first thought upon hearing of your diagnosis was to check that you were in fact the same person who infamously implied that those who “lead good lives” don’t have pre-existing conditions. It seems you are. As such, I hope and pray that your diagnosis helps you understand the experiences of cancer patients across this country.

I’m not here to berate you for past comments nor to ask you for your support of universal healthcare. I simply want to ask you to please, please remember how it feels to get a cancer diagnosis. Remember what it’s like to face the uncertainty of upcoming treatments. Remember that there are millions of people just like you carrying these same leaden worries in the pits of their stomachs—and keep in mind that many of us face added uncertainties and fears about our health insurance and treatment costs as well.

My first two years of cancer treatment each totaled over a million dollars in costs, and while my third year wasn’t quite as intense it still would have been unattainably expensive were I uninsured. Currently my life depends on laws prohibiting annual and lifetime limits for coverage, protections for people with pre-existing conditions, and Medicare funding as much as it does on treatment. I don’t take that lightly and I trust you don’t either.

So I beg you to be mindful of your fellow cancer patients as you consider legislative measures affecting healthcare and those who most need it. Please, first do no harm. And if you want to talk to someone who has been through whatever treatment looms before you, just let me know. I’ve been through every kind of cancer treatment out there these last three years, and I’m happy to share my experiences and tips for eating when you do NOT want to if you might find that helpful.

All the best,

Morgan J Bolt

Dear Representative Brooks,

First, I want to wish you all the best. Cancer is an horrific disease that I wish nobody had to endure. I hope and pray that you make a full and prompt recovery from your upcoming surgery, attain ‘No Evidence of Disease’ status, and stay cancer free for many years to come. May all your treatments go smoothly, may your insurance cover every mode of treatment you need, and may you experience minimal complications from this disease so that it disrupts your life as little as possible.

Second—in the spirit of full honesty—I must admit that my first thought upon hearing of your diagnosis was to check that you were in fact the same person who infamously implied that those who “lead good lives” don’t have pre-existing conditions. It seems you are. As such, I hope and pray that your diagnosis helps you understand the experiences of cancer patients across this country.

I’m not here to berate you for past comments nor to ask you for your support of universal healthcare. I simply want to ask you to please, please remember how it feels to get a cancer diagnosis. Remember what it’s like to face the uncertainty of upcoming treatments. Remember that there are millions of people just like you carrying these same leaden worries in the pits of their stomachs—and keep in mind that many of us face added uncertainties and fears about our health insurance and treatment costs as well.

My first two years of cancer treatment each totaled over a million dollars in costs, and while my third year wasn’t quite as intense it still would have been unattainably expensive were I uninsured. Currently my life depends on laws prohibiting annual and lifetime limits for coverage, protections for people with pre-existing conditions, and Medicare funding as much as it does on treatment. I don’t take that lightly and I trust you don’t either.

So I beg you to be mindful of your fellow cancer patients as you consider legislative measures affecting healthcare and those who most need it. Please, first do no harm. And if you want to talk to someone who has been through whatever treatment looms before you, just let me know. I’ve been through every kind of cancer treatment out there these last three years, and I’m happy to share my experiences and tips for eating when you do NOT want to if you might find that helpful.

All the best,

Morgan J Bolt

Published on December 13, 2017 18:30

December 4, 2017

I Fear for our National Monuments

This weekend I learned that there are plans in the works to significantly reduce a couple of national monuments in Utah. Today those plans were officially announced. Bears Ears is slated to be downsized by about 85%, while Grand Staircase Escalante will shrink to just half of its current size.

I’m mildly optimistic that none of this will hold up in court, but it still worries me. My wife and I were just in Grand Staircase Escalante in October, and we drove right around Bears Ears too. We could see the namesake buttes from the road we were on. It was just a little too remote even for us though—at least given our time constraints and the fact that we had just come off four consecutive nights without running water. And that is precisely one of the main points of these monuments. They’re remote. They’re wild.

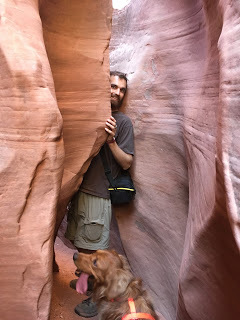

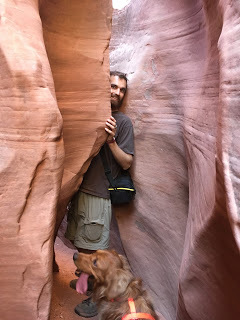

Exploring a Slot CanyonWhile in Grand Staircase we talked about how it was an absolutely incredible place, somewhere you wish everyone could experience, yet it wouldn’t be what it is were it any more developed or busy. While part of us would have liked the washboarded, unpaved roads there to be smoother, we were mostly glad they weren’t. It made the place more remote. Part of us wished for better maps and trailmarkers, making it easier to explore the various slot canyons. But we appreciated them as hidden treasures that much more. Part of us wished there had been better signage leading us to the dinosaur footprints, but as it was we had more of an adventure looking for them and we were the only ones in sight. That’s part of the allure of such places. They’re places you can get truly alone and disconnected from everything else going on in the world, at least for a couple days.

Exploring a Slot CanyonWhile in Grand Staircase we talked about how it was an absolutely incredible place, somewhere you wish everyone could experience, yet it wouldn’t be what it is were it any more developed or busy. While part of us would have liked the washboarded, unpaved roads there to be smoother, we were mostly glad they weren’t. It made the place more remote. Part of us wished for better maps and trailmarkers, making it easier to explore the various slot canyons. But we appreciated them as hidden treasures that much more. Part of us wished there had been better signage leading us to the dinosaur footprints, but as it was we had more of an adventure looking for them and we were the only ones in sight. That’s part of the allure of such places. They’re places you can get truly alone and disconnected from everything else going on in the world, at least for a couple days.

Places like Grand Staircase Escalante and Bears Ears are also religiously significant for indigenous peoples, and anyone who professes to care about freedom of religion really has to care about this too. As it is, I find it deeply ironic that the party touting itself as a champion of religious freedom is leading the backlash against preserving a religiously significant site like Bears Ears, but that’s really another matter for another writer, I think. I can really only suggest reading something written by native people for a better perspective on this entire matter, and a good starting point might be hereor here. My only connection to this is that my wife and I were just there a little over a month ago.

Grand Staircase was probably our favorite place we visited on our entire road trip—and that’s competing with Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon. It was silent, it was empty, it was peaceful, and it was utterly beautiful. Reducing it by half is a disturbing precedent to set, and I shudder to think what will become of the place if fossil fuel companies have their way.

I’m mildly optimistic that none of this will hold up in court, but it still worries me. My wife and I were just in Grand Staircase Escalante in October, and we drove right around Bears Ears too. We could see the namesake buttes from the road we were on. It was just a little too remote even for us though—at least given our time constraints and the fact that we had just come off four consecutive nights without running water. And that is precisely one of the main points of these monuments. They’re remote. They’re wild.

Exploring a Slot CanyonWhile in Grand Staircase we talked about how it was an absolutely incredible place, somewhere you wish everyone could experience, yet it wouldn’t be what it is were it any more developed or busy. While part of us would have liked the washboarded, unpaved roads there to be smoother, we were mostly glad they weren’t. It made the place more remote. Part of us wished for better maps and trailmarkers, making it easier to explore the various slot canyons. But we appreciated them as hidden treasures that much more. Part of us wished there had been better signage leading us to the dinosaur footprints, but as it was we had more of an adventure looking for them and we were the only ones in sight. That’s part of the allure of such places. They’re places you can get truly alone and disconnected from everything else going on in the world, at least for a couple days.

Exploring a Slot CanyonWhile in Grand Staircase we talked about how it was an absolutely incredible place, somewhere you wish everyone could experience, yet it wouldn’t be what it is were it any more developed or busy. While part of us would have liked the washboarded, unpaved roads there to be smoother, we were mostly glad they weren’t. It made the place more remote. Part of us wished for better maps and trailmarkers, making it easier to explore the various slot canyons. But we appreciated them as hidden treasures that much more. Part of us wished there had been better signage leading us to the dinosaur footprints, but as it was we had more of an adventure looking for them and we were the only ones in sight. That’s part of the allure of such places. They’re places you can get truly alone and disconnected from everything else going on in the world, at least for a couple days.Places like Grand Staircase Escalante and Bears Ears are also religiously significant for indigenous peoples, and anyone who professes to care about freedom of religion really has to care about this too. As it is, I find it deeply ironic that the party touting itself as a champion of religious freedom is leading the backlash against preserving a religiously significant site like Bears Ears, but that’s really another matter for another writer, I think. I can really only suggest reading something written by native people for a better perspective on this entire matter, and a good starting point might be hereor here. My only connection to this is that my wife and I were just there a little over a month ago.

Grand Staircase was probably our favorite place we visited on our entire road trip—and that’s competing with Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon. It was silent, it was empty, it was peaceful, and it was utterly beautiful. Reducing it by half is a disturbing precedent to set, and I shudder to think what will become of the place if fossil fuel companies have their way.

Published on December 04, 2017 14:43

November 23, 2017

I’m Thankful for Church

The following is a modified excerpt from my book “Cancer is Not Evil,” for which I am seeking a publisher now.

Thanksgiving has arrived, and this year I want to take a moment to be thankful for the churches I’ve been fortunate enough to be a part of.I’m thankful for the church I grew up attending, the only church I called home from the day I was born until I left town to go to college. Located in South Bend, Indiana, it was a rather academic church attended by a great many professors and (mostly graduate) students at the University of Notre Dame, Bethel, and Saint Mary’s colleges. This church wasn’t academic in the sense that it was impersonal or that the Christian faith was portrayed as some theoretical or speculative consideration, but it was an extremely intellectually vibrant community, one that I grew up thinking was normal. People like Alvin Plantinga went to my church, and it wasn’t until I was ten or twelve that I realized he was perhaps the preeminent Christian philosopher alive. As a kid, I knew him simply as “Al,” a really nice guy at church who talked to my Sunday School once about rock climbing.Looking back I see now how such a church environment fostered in me a desire for a greater intellectual understanding of God as well as an appreciation for robust sermons. It is in so many ways because of my church in South Bend that I learned to grow from my doubts and ask the kinds of questions I find fascinating and faith-deepening. As far as I’m concerned you can’t grow up going to church with philosophers and not become keenly interested in the deeper, weirder questions of Christianity. This certainly held true for me at least, and I remain immensely grateful for ways this church fostered in me an abiding love for the intellectual side of Christianity that has saved me from a crisis of faith more than once.I’m thankful too for the church I went to while in college and the one I attend now, for they have influenced me in important and helpful ways as well. Both in the Anabaptist tradition, these Brethren in Christ and Mennonite churches have helped me grow in my understanding of my citizenship in heaven and how to regard that first and foremost. I’ve never been a part of an overtly nationalistic or patriotic church so I’ve never been especially tempted to regard the United States as God’s chosen country or equate Christianity with patriotism or membership in any particular political party. But I have on occasion visited churches with American flags up front, and I’ve been friends with plenty of people who hold such views so I’m not ignorant about Christian Nationalism either. This emphasis of the Mennonite Church I attend now seems especially relevant today as Christian Nationalism in this country grows ever-stronger. What it means to regard citizenship in heaven above my citizenships in the US and Canada, and what it means to work for God’s kingdom rather than any political entity here on earth has really helped me as I process the current political landscape and the deepening mire we seem to be sinking into right now.I’m also thankful for what these churches have taught me about living simply and what it means to balance living differently because of my faith without becoming irrelevant or absurd to the rest of the world. At these churches I’ve found that it’s not about visibly denying yourself the luxuries, comforts, and ways of the world in an effort to be set apart from it, as some insist. But neither is it about dismissing that idea altogether as many do and living no differently—except perhaps on Sunday morning—than anyone else. Living a simple, Christlike life isn’t about merely doing the opposite of whatever might be considered secular for the sake of holiness, but neither does it shrug off nor disregard the idea that following Jesus requires living in profoundly different ways from those who don’t. It isn’t about making a show of driving a cheaper car than you could afford or publically boycotting this movie or that singer, but it isn’t embracing every facet of our deeply unhealthy consumer-driven capitalist society either.Instead, it is the idea that we should try to live a life that runs counter to our materialistic culture in ways that don’t necessarily look different on the outside but feel different on the inside. It might mean making do with less, and it might mean buying ourselves the very best we can afford. It depends on the circumstances and the reasons we hold in our hearts for doing so. It means not judging others for the way we perceive their life choices and asking others to extend the same grace to us. It is only in the last few years that I feel I truly understand what it means to follow Christ with regards to the way I interact with the broader culture I’m a part of, and it’s a lesson that feels especially relevant as we approach Christmas, the most secularized and commercialized of the Christian holy days.Finally, I’m thankful for criticism and critiques of Christianity and The Church as well. There’s plenty going around right now, and I implore you to check out #EmptyThePews or #ChurchToo if you don’t know what I’m talking about. Under these hashtags you’ll find harrowing reads, stories that need to be told so we can properly confront the issues pervading American Christianity today. So much dirt has been swept under the rugs in our churches that we’re finally tripping on the lumps, and it’s an ugly, necessary process that I’m glad is taking place.

I guess I’m really just thankful for The Church, that weird, wonderful, profoundly flawed community that, like us all, is worth saving, even and especially when it seems irredeemable.

Thanksgiving has arrived, and this year I want to take a moment to be thankful for the churches I’ve been fortunate enough to be a part of.I’m thankful for the church I grew up attending, the only church I called home from the day I was born until I left town to go to college. Located in South Bend, Indiana, it was a rather academic church attended by a great many professors and (mostly graduate) students at the University of Notre Dame, Bethel, and Saint Mary’s colleges. This church wasn’t academic in the sense that it was impersonal or that the Christian faith was portrayed as some theoretical or speculative consideration, but it was an extremely intellectually vibrant community, one that I grew up thinking was normal. People like Alvin Plantinga went to my church, and it wasn’t until I was ten or twelve that I realized he was perhaps the preeminent Christian philosopher alive. As a kid, I knew him simply as “Al,” a really nice guy at church who talked to my Sunday School once about rock climbing.Looking back I see now how such a church environment fostered in me a desire for a greater intellectual understanding of God as well as an appreciation for robust sermons. It is in so many ways because of my church in South Bend that I learned to grow from my doubts and ask the kinds of questions I find fascinating and faith-deepening. As far as I’m concerned you can’t grow up going to church with philosophers and not become keenly interested in the deeper, weirder questions of Christianity. This certainly held true for me at least, and I remain immensely grateful for ways this church fostered in me an abiding love for the intellectual side of Christianity that has saved me from a crisis of faith more than once.I’m thankful too for the church I went to while in college and the one I attend now, for they have influenced me in important and helpful ways as well. Both in the Anabaptist tradition, these Brethren in Christ and Mennonite churches have helped me grow in my understanding of my citizenship in heaven and how to regard that first and foremost. I’ve never been a part of an overtly nationalistic or patriotic church so I’ve never been especially tempted to regard the United States as God’s chosen country or equate Christianity with patriotism or membership in any particular political party. But I have on occasion visited churches with American flags up front, and I’ve been friends with plenty of people who hold such views so I’m not ignorant about Christian Nationalism either. This emphasis of the Mennonite Church I attend now seems especially relevant today as Christian Nationalism in this country grows ever-stronger. What it means to regard citizenship in heaven above my citizenships in the US and Canada, and what it means to work for God’s kingdom rather than any political entity here on earth has really helped me as I process the current political landscape and the deepening mire we seem to be sinking into right now.I’m also thankful for what these churches have taught me about living simply and what it means to balance living differently because of my faith without becoming irrelevant or absurd to the rest of the world. At these churches I’ve found that it’s not about visibly denying yourself the luxuries, comforts, and ways of the world in an effort to be set apart from it, as some insist. But neither is it about dismissing that idea altogether as many do and living no differently—except perhaps on Sunday morning—than anyone else. Living a simple, Christlike life isn’t about merely doing the opposite of whatever might be considered secular for the sake of holiness, but neither does it shrug off nor disregard the idea that following Jesus requires living in profoundly different ways from those who don’t. It isn’t about making a show of driving a cheaper car than you could afford or publically boycotting this movie or that singer, but it isn’t embracing every facet of our deeply unhealthy consumer-driven capitalist society either.Instead, it is the idea that we should try to live a life that runs counter to our materialistic culture in ways that don’t necessarily look different on the outside but feel different on the inside. It might mean making do with less, and it might mean buying ourselves the very best we can afford. It depends on the circumstances and the reasons we hold in our hearts for doing so. It means not judging others for the way we perceive their life choices and asking others to extend the same grace to us. It is only in the last few years that I feel I truly understand what it means to follow Christ with regards to the way I interact with the broader culture I’m a part of, and it’s a lesson that feels especially relevant as we approach Christmas, the most secularized and commercialized of the Christian holy days.Finally, I’m thankful for criticism and critiques of Christianity and The Church as well. There’s plenty going around right now, and I implore you to check out #EmptyThePews or #ChurchToo if you don’t know what I’m talking about. Under these hashtags you’ll find harrowing reads, stories that need to be told so we can properly confront the issues pervading American Christianity today. So much dirt has been swept under the rugs in our churches that we’re finally tripping on the lumps, and it’s an ugly, necessary process that I’m glad is taking place.

I guess I’m really just thankful for The Church, that weird, wonderful, profoundly flawed community that, like us all, is worth saving, even and especially when it seems irredeemable.

Published on November 23, 2017 18:47