Michael May's Blog, page 151

December 12, 2014

“If Quite Convenient, Sir" | Walter Matthau (1978)

Index of other entries in The Christmas Carol Project

As the title suggests, Rankin-Bass' The Stingiest Man in Town focuses on Scrooge's miserliness. Pretty much to the exclusion of any other possible trait. With it's narrating "humbug" and sappy songs, it's almost purely children's entertainment, which means that they aren't going for a complex Scrooge. All of his conflicts with Cratchit and Fred have been around money and Scrooge's hatred of Christmas (because it's a time for spending money).

For Cratchit's part, we've learned that he's stealing coal from Scrooge, so he's not especially timid. He doesn't respect Scrooge and has figured out how to game the system. Once Fred leaves, Scrooge brings up the topic of the next day off and Cratchit gets downright sassy with him. Instead of "If quite convenient, sir," he says, "I didn't think you'd have to ask."

That leads Scrooge into his complaint about "picking a man's pocket every 25th of December," but he's defending himself to Cratchit. In fact, as he continues, he goes hard for sympathy and even musters up some tears until Cratchit actually relents and volunteers to take the holiday unpaid! Scrooge has no real power, he relies on Cratchit's kindness to get what he wants. He even lets Cratchit go home first and stays himself to lock up. Scrooge's stinginess makes him a man to be pitied, not feared, but I'm not complaining. It's not a very nuanced take, but it's a pleasant change of pace from the darker versions we've been looking at.

There aren't any outside scenes mixed in with this one, but we've already seen plenty of that earlier in the show. Everyone outside is enjoying the holiday. There's no social commentary about the poor; carollers sing out of joy, not for donations. And even though Scrooge hasn't interacted with the singers, he has had an altercation with some kids building a snowman. In this version, Christmas is a universally wonderful time and Scrooge is ridiculous for not getting it.

Published on December 12, 2014 04:00

December 11, 2014

“If Quite Convenient, Sir" | Alastair Sim (1971)

Index of other entries in The Christmas Carol Project

In Richard Williams' Oscar-winning cartoon, Scrooge has so far been portrayed as cold-hearted in every sense of the word. He's gotten angry, but for the most part he's calm, aloof, and used to being in complete control of his situation. Cratchit hasn't had much to do, but he looks constantly and deeply sad. There's an enormous imbalance in power between these two men and Cratchit is worn down by it.

For good reason, too. The one time that Scrooge has lost his cool was when Cratchit wished Fred a "Merry Christmas." Scrooge had patiently endured Fred's interruption and was dismissive of him until Cratchit got involved. This Scrooge appears to be especially abusive to his clerk as this year's scene continues to reveal.

After the solicitors leave the counting house, the film fades to black and lets time pass before the clock chimes seven. The film then cuts from the clock to Scrooge and Cratchit as they get ready to go. Cratchit's already dressed for outside and is helping Scrooge by holding the old man's hat. The first line is Scrooge's asking Cratchit about the day off, but for all we know we could be coming in on the middle of a conversation.

Not that Cratchit is all that talkative. His "If quite convenient, sir" is very timid and leads to more lecturing by Scrooge. Alastair Sim delivers his lines languidly, explaining his point as if to a child. To Cratchit's credit though, he sticks up for himself a little when he observes that it's only once a year. That irritates Scrooge though and he's grouchy when he orders Cratchit to be there all the earlier the next morning.

They leave together and it's actually Scrooge who locks the door, as if he doesn't trust Cratchit. This is the saddest, most miserable Cratchit so far.

There's no caroler or street scene in this version. We'll get a little of that next year as we follow Scrooge home, but for now the movie's focused on the two men. And there's certainly no scene with Cratchit joining any boys in sliding on some ice. That kind of levity would completely ruin what the movie's doing with his character so far.

Published on December 11, 2014 04:00

December 10, 2014

“If Quite Convenient, Sir" | Teen Titans #13 (1968)

Index of other entries in The Christmas Carol Project

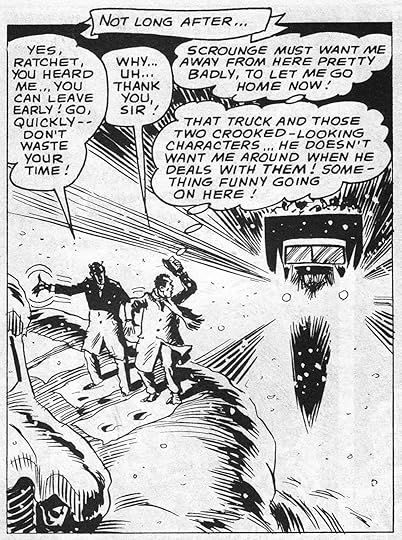

We already covered this scene in the very first (and so far, only) post on the Teen Titans adaptation, because it's part of the introduction to Scrounge and Ratchet. But it's been a couple of years since I've gotten to write about the Titans story, so I should at least share another panel that's related to this year's scene.

Back to a real adaptation tomorrow as we move into cartoon versions.

Published on December 10, 2014 16:00

Ted White's Fantastic: Short Heroic Fantasy [Guest Post]

By GW Thomas

By GW ThomasThe Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction began its life as The Magazine of Fantasy. By the second issue the words "and Science Fiction" had been added. Why? Because no pure Fantasy magazine had ever made it past five issues. Weird Tales had been more Horror than Fantasy. Unknown published John W Campbell's version of Fantasy, but a brand for Science Fiction readers, almost an anti-Fantasy at times. Cele Goldsmith and the long-running Fantastic knew this too and the mix had always been heavier to the SF side. During the early 1960s Goldsmith cultivated Sword and Sorcery writers like Fritz Leiber, bringing him back to magazine publishing with new Fafhrd and Grey Mouser tales. She also brought in new writers like John Jakes with Brak the Barbarian and Roger Zelazny with Dilvish the Damned. This continued until June 1965 when Goldsmith (now Lalli) left the publication when Fantastic was sold to Sol Cohen, with a change from monthly to a bi-monthly schedule.

Laili was replaced by Joseph Ross (Joseph Wrzos) who inherited a huge stockpile of stories from the old days of the Pulps. Fantastic became a reprint magazine, its first new issue containing only one original story, the Fafhrd and Gray Mouser tale "Stardock". Ross published the small reserve of Fantasy tales purchased before the switch that included Avram Davidson's classic novel The Phoenix and the Mirror and "The Bells of Shoredan" by Zelazny. Amongst the reprints was the Pusadian tale "The Eye of Tandyla" by L Sprague de Camp (from Fantastic Adventures, May 1951). But Ross wasn't long for the position, being replaced by Harry Harrison and later Barry N Malzberg. Both Harrison and Malzberg would leave over the reprints that plagued the magazine. They wanted to edit a magazine of new, modern Science Fiction and Fantasy.

Fantastic needed a new editor. One who could present both quality Science Fiction and Fantasy. Cohen was willing to sell his reprints in other formats and leave the new editor to his work. A choice was found with Robert Silverberg's help: junior editor from FaSF, Ted White. For ten years White would create a magazine that featured intriguing works of Fantasy as well as decorate it with great artists including Jeff Jones, Mike Kaluta, Ken Kelly, Harry Roland, and Stephen Fabian (and occasionally Joe Staton's pieces that remind me of DoodleArt). And this with the major handicap of low pay, for Fantastic offered its writers only one-cent a word in a marketplace that usually paid three to five cents. By cultivating new writers and snapping up gems where he could, White offered stories that often were chosen for the Year's Best Fantasy collections and even won the occasional award.

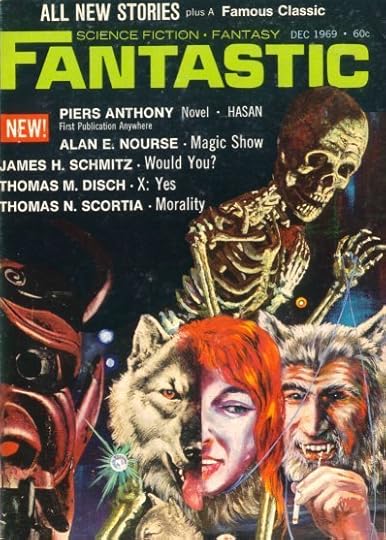

White's debut was April 1969 and its contents were not spectacular, chosen by others. The only hint of what was to come was Fritz Leiber's review column on ER Eddison's The Worm Ouroboros. It would have to wait until December 1969 before a truly interesting Fantasy would appear. This was Piers Anthony's Arabian Nights inspired Hasan, which Anthony supported with an essay on Arabesque Fantasy.

White's debut was April 1969 and its contents were not spectacular, chosen by others. The only hint of what was to come was Fritz Leiber's review column on ER Eddison's The Worm Ouroboros. It would have to wait until December 1969 before a truly interesting Fantasy would appear. This was Piers Anthony's Arabian Nights inspired Hasan, which Anthony supported with an essay on Arabesque Fantasy.April 1970 saw another Fafhrd and Gray Mouser tale, a series dating back to Goldsmith but one that White was happy to continue. "The Snow Women" is a tale of Fafhrd's youth set in the cold north. Two more would follow in later years, "Trapped in the Shadowlands" (November 1973) and "Under the Thumbs of the Gods" (April 1975). At this time Leiber was collecting his tales into the first collections of Lankhmar and the new material would later be included.

Also in the April 1970 issue was John Brunner's "The Wager Lost by Winning," part of his Traveller in Black series, of which he would continue with "Dread Empire" (April 1971). Brunner, a British author known for his Science Fiction, created something different in these tales of the odd little wizard who roams the world, and they would win him a place in the Thieves' World alumni eight years later.

June 1971 featured a new non-fiction series, "Literary Swordsmen and Sorcerers" by L Sprague De Camp. This series of articles looked at classic Fantasy authors including Robert E Howard, HP Lovecraft, Fletcher Pratt, William Morris, L Ron Hubbard, TH White and JRR Tolkien, running off and on until 1976. These pieces offered intriguing insight into the lives and trials of Fantasy writers, leading de Camp to write the first major biographies of both Lovecraft (Lovecraft: A Biography), 1975) and Howard (Dark Valley Destiny, 1983).

February 1972 saw the first of the Michael Moorcock stories to appear in Fantastic, with "The Sleeping Sorceress" starring the albino superstar, Elric of Melnibone. Later the same year, Count Brass featuring Dorian Hawkmoon would appear in August 1972. Both characters would become one as Moorcock melded his multiverse together to include everyone from Elric to Sojan to Jerry Cornelius.

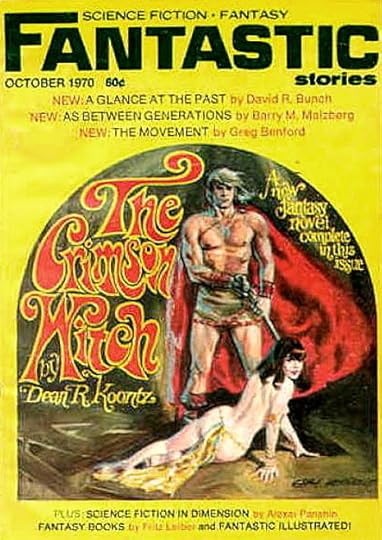

February 1972 saw the first of the Michael Moorcock stories to appear in Fantastic, with "The Sleeping Sorceress" starring the albino superstar, Elric of Melnibone. Later the same year, Count Brass featuring Dorian Hawkmoon would appear in August 1972. Both characters would become one as Moorcock melded his multiverse together to include everyone from Elric to Sojan to Jerry Cornelius.White published the magazine versions of several good heroic fantasy novels during his decade: The Crimson Witch (October 1970) by Dean R Koontz, which feels more like Sword and Planet, like Ted White's own "Wolf Quest" (April 1971), "The Forges of Nainland are Cold" by Avram Davidson (Ursus of Ultima Thule in book form) in August 1972, The Fallible Fiend by L Sprague de Camp (December 1972-February 1973), part of his Novaria series, "The Son of Black Morca" by Alexei and Cory Panshin (Earthmagic in paperback) in April-July 1973, The White Bull by Fred Saberhagen (November 1976) who was moving away from the robotic Berserkers to become a Fantasy bestseller, and The Last Rainbow by Parke Godwin (July 1978). All of which would populate the book racks of the 1980s.

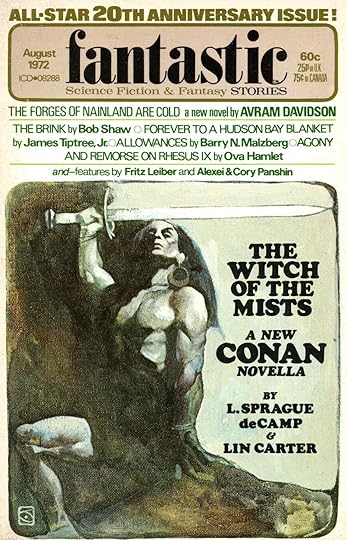

August 1972 saw the beginning of a series of new Conan pastiches by L Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter. "The Witches of the Mist" (August 1972), "The Black Sphinx of Nebthu" (July 1973), "Red Moon of Zembabwei" (July 1974), and "Shadows in the Skull" (February 1975), all of which form Conan of Aquilonia. Lin Carter groused in his intros to Year's Best Fantasy about this book, which had been stuck in legal limbo with the collapse of Lancer. Finally free, it appeared serially in Fantastic then in paperback in 1977.

Several other Sword and Sorcery series got a new start or a first start in Fantastic. Lin Carter wrote new tales of Thongor's youth with "Black Hawk of Valkarth" (September 1974), "The City in the Jewel" (December 1975) and "Black Moonlight" (November 1976). He also offered posthumous collaborations with masters Robert E Howard in "The Tower of Time" (June 1975) - a James Allison reincarnation story - and with Clark Ashton Smith in verbose Mythos-heavy pieces, "The Scroll of Morloc" (October 1975) and "The Stair in the Crypt" (August 1976). The February 1977 issue featured an interview with Lin Carter that was informative about his days on the Ballantine Fantasy series and other Fantasy goings-on in the 1960s and 1970s.

Several other Sword and Sorcery series got a new start or a first start in Fantastic. Lin Carter wrote new tales of Thongor's youth with "Black Hawk of Valkarth" (September 1974), "The City in the Jewel" (December 1975) and "Black Moonlight" (November 1976). He also offered posthumous collaborations with masters Robert E Howard in "The Tower of Time" (June 1975) - a James Allison reincarnation story - and with Clark Ashton Smith in verbose Mythos-heavy pieces, "The Scroll of Morloc" (October 1975) and "The Stair in the Crypt" (August 1976). The February 1977 issue featured an interview with Lin Carter that was informative about his days on the Ballantine Fantasy series and other Fantasy goings-on in the 1960s and 1970s.Brian Lumley published some of his first Primal Lands tales, part Lovecraftian horror, part Sword and Sorcery in Fantastic. These included "Tharquest and the Lamia Orbiquita" (November 1976) and "How Kank Thad Returned to Bhur-esh" (June 1977) . Lumley's Fantasy harkens back to Weird Tales and the works of HP Lovecraft's Dreamlands and Clark Ashton Smith's sardonic fantasies.

Another good start was made by Australian writer Keith Taylor, who wrote about wandering singer and swordsman Felimid mac Fel. These stories were the embryonic form of the book Bard, which Taylor began under the pseudonym Denis More. "Fugitives in Winter" (October 1975), "The Forest of Andred" (November 1976), and "Buried Silver" (February 1977) form the first part of the series that went on to contain five volumes with further tales in the new Weird Tales in the 1990s.

Other heroic fantasy pieces included "The Holding of Kolymar" (October 1972) by Gardner F Fox, "The Night of Dreadful Silence" (September 1973) by Glen Cook, destined for fame with his Black Company in the 1980s, "Death from the Sea" by Harvey Schreiber (August 1975), "Two Setting Suns" (May 1976) by Karl Edward Wagner, part of the Kane series , and "Nemesis Place" (April 1978) by David Drake, featuring Dama and Vettius, Drake's two Roman heroes.

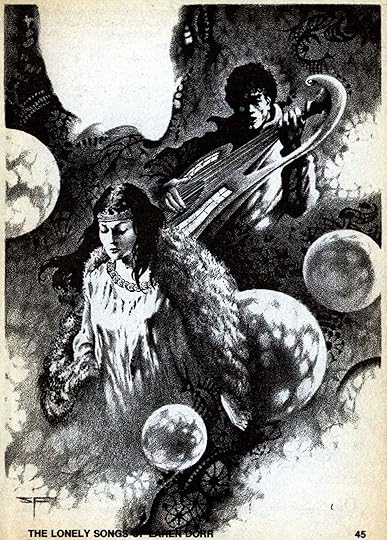

Other heroic fantasy pieces included "The Holding of Kolymar" (October 1972) by Gardner F Fox, "The Night of Dreadful Silence" (September 1973) by Glen Cook, destined for fame with his Black Company in the 1980s, "Death from the Sea" by Harvey Schreiber (August 1975), "Two Setting Suns" (May 1976) by Karl Edward Wagner, part of the Kane series , and "Nemesis Place" (April 1978) by David Drake, featuring Dama and Vettius, Drake's two Roman heroes.Not all of White's choices were Sword and Sorcery. He published the wonderful "Will-o-Wisp"(September-November 1974) by Thomas Burnett Swann, "War of the Magicians" (November 1973) by William Rostler, "The Dragon of Nor-Tali" (February 1975) by Juanita Coulsen, "The Lonely Songs of Loren Dorr" (May 1976) by George RR Martin (long before Game of Thrones) and "A Malady of Magicks" (October 1978) by Craig Shaw Gardner, beginning the popular humorous Fantasy series featuring Ebenezum.

By the end of 1978 Fantastic was on a quarterly schedule and losing readership. White had grown more dissatisfied with Sol Cohen, wanting to take the magazine into the slick market. He also wanted a raise. January 1979 was his last issue before he left to edit Heavy Metal magazine. He was replaced with neophyte Elinor Mavor. Another period of reprints followed and the look of the magazine declined. Mavor was finding her feet with new authors like Wayne Wightman, Brad Linaweaver and artists like Janny Wurts. She published Stephen Fabian's graphic story "Daemon" (July 1979-July 1980), but the only gem to appear before amalgamation with Amazing Stories was the two part serial of The White Isle by Darrell Schweister, with illustrations by Gary Freeman, in the April and July 1980 issues. A last gasp of wonder before Fantastic was gone. It was the end of an era, but too few even knew what was lost. Other magazines would attempt to do what Ted White had done, through self sacrifice and continuous networking, but none would ever be such a haven for short heroic fantasy again.

GW Thomas has appeared in over 400 different books, magazines and ezines including The Writer, Writer's Digest, Black October Magazine and Contact. His website is gwthomas.org. He is editor of Dark Worlds magazine.

Published on December 10, 2014 04:00

December 9, 2014

“If Quite Convenient, Sir" | Graphic Classics, Volume 19: Christmas Classics (2010)

Index of other entries in The Christmas Carol Project

It's been tough to get a particular read on Scrooge and Cratchit in Alex Burrows and Micah Farritor's version so far. The two characters have performed their parts, but there hasn't been anything to distinguish them yet from other adaptations. But like with the other comics adaptations we've looked at, this scene helps some with that.

As soon as the charitable solicitors leave, Scrooge is up and putting on his coat. When he asks Cratchit about the day off tomorrow, it's with the same sneer he's been wearing for most of the story so far. There's an arrogant quality to this Scrooge. He has a sense of humor, but it's mean-spirited. He doesn't complain that Christmas off isn't fair, so he's not even making a bid for sympathy. That reinforces the idea that he's proud and sees others - especially Cratchit - as beneath him.

When he leaves, the story follows him and leaves Cratchit alone in the office. It makes no mention of how long Cratchit will be there, further distancing Scrooge from his employee. In fact, this is the first interaction that Scrooge and Cratchit have had all story. They've worked together in the same office for five pages now, but haven't spoken to each other. There's been no threatening of Cratchit's job or anything else. Cratchit is mostly ignored; not worth Scrooge's attention.

And with only two lines of dialogue so far, Cratchit's barely worth the reader's attention either. I still can't get a good read on him, which may be intentional if Burrows and Farritor are trying to keep me in Scrooge's shoes. Maybe in this version I'm not supposed to get much about Cratchit until we visit his house later in the story.

As Scrooge takes off, there is a lone caroller at the door singing "God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen," but Scrooge is unprepared for him and doesn't have time to grab a ruler. Instead, he growls at the kid, chasing him off, and slams the door shut behind himself.

The boy doesn't seem to be singing for money though. His hands are full with a songbook and a lantern on a pole, so he doesn't even have anything to collect donations in if they were offered to him. I'm not sure why one kid would be singing door to door by himself, but the exchange doesn't seem to be making any social commentary other than "Scrooge really hates Christmas."

We get more of that message when the story follows Scrooge into the street. Farritor draws a lovely panel in which Scrooge is surrounded by Christmas celebrants shopping, partying, and smooching in the road. Unlike the previous street scene in this version, this one is full of holly and other greenery.

Christmas is in full force, but Scrooge is having none of it. He's raising one arm as if to strike someone who isn't there and he's frowning as he says, "Humbug." The sneer is gone though, maybe because no one's paying any attention to him. Scrooge's hatred of Christmas is genuine, but he possibly plays it up when he knows he can get a rise out of someone.

Published on December 09, 2014 04:00

December 8, 2014

“If Quite Convenient, Sir" | Campfire’s A Christmas Carol (2010)

Index of other entries in The Christmas Carol Project

Scott McCullar and Naresh Kumar's adaptation skips the street scene outside of Scrooge's office except for some carollers. Dickens' solo kid has been joined by four more (singing "God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen," for the record), but this won't be the only version to turn the boy into a group.

I'm not sure why adaptations do that except to make the act of carolling more festive and fun. When a lone, small boy does it, it feels like an act of desperation as he tries to make enough money to maybe eat that night. When it's a group, it's a communal activity that possibly they're doing for the fun of it. So far, the adaptations we've looked at have all kept the kid by himself, heightening the despair that's mingled with the Christmas celebrations. By turning him into a quintet, McCullar and Kumar make a conscious choice that lightens the mood.

It gets dark again quickly when Scrooge gets involved though. I noticed last year that (intentionally by the creators or not) this Scrooge isn't just grumpy and mean; he's actively evil. When he picks up the ruler to chase away the characters, it's not just what he had handy, it's a bona fide weapon. Scrooge's ruler changes size from panel to panel (it's relatively normal-sized in the first panel above), but when he brandishes it against the kids it looks like it's about two feet long and has a sharpened end.

As the kids are still fleeing and Scrooge is still holding the ruler, he says to Cratchit, "And you will want all day off tomorrow, I suppose?" It's like he's challenging Cratchit.

In the background, Cratchit's already putting on his hat. No one's acknowledged that it's quitting time, but Cratchit knows that it is and he's wasting no time. I don't imagine that Cratchit's actually bold enough to leave early, but the effect is that Scrooge sort of threatens him and he's beating feet out of there. His "If it's convenient, sir," sounds like a way of deliberately not answering Scrooge's challenge.

When Scrooge says that it's not convenient, he's got the same mad look in his eye that he had when he talked about boiling people in their own pudding. He gets no sympathy points in this one. He feels like a sociopath looking for an excuse to snap.

Curiously, Cratchit doesn't seem bothered when he says, "It's only once a year, sir." He looks grim-faced and determined. A couple of panels later, Cratchit slips up and almost wishes Scrooge a "Merry Christmas," but catches himself and changes it to "good night." He doesn't look at all worried though. He's more focused on trying to get his coat buttoned.

A possible explanation for all that is something I've just noticed. This Cratchit has a large, square chin that's in direct contrast with Scrooge's smaller, weaker one. Cratchit's not a little guy either, physically. So it's very possible that he wants to avoid a confrontation not because he's afraid of Scrooge, but because he's afraid of what he might have to do to Scrooge if it came to that. And then Cratchit would be out of a job and it's a whole mess...

This is one, crazy Christmas Carol, but I'm digging it.

Published on December 08, 2014 16:00

"JEEEEEEEG!" | The Nerd Lunch fellas and I talk Wrath of Khan

The awesome guys at Nerd Lunch had me back on last week, which was fantastic for a number of reasons. It hadn't been that long since I'd been on to talk about Star Wars, one of the great loves of my nerdy life, so I was surprised and especially excited to come back and talk not only about another great nerd-love, Star Trek, but also about what's arguably the best use of that show's most recognizable characters.

Not only that, but I got to participate in the guys' Drill Down format, where they do a deep dive into a single movie. That's something I've always wanted to do with them.

And not only that, but I also finally got to participate in a full episode with Jeeg, so now I feel like I've had the full Nerd Lunch experience. I know I'm gushing, but I really do love hanging out and chatting with those guys, so I hope you'll give it a listen, either via the embedded version above or however you like to listen to podcasts.

Speaking of gushing, Wrath of Khan is a great movie and we give it a lot of love, but we also talk about some of its problems. Or at least about a couple of problems that I have with it. One of the cool things about the episode is that we don't all agree about everything, so it's a great discussion and I hope you'll dig it.

Published on December 08, 2014 04:00

December 7, 2014

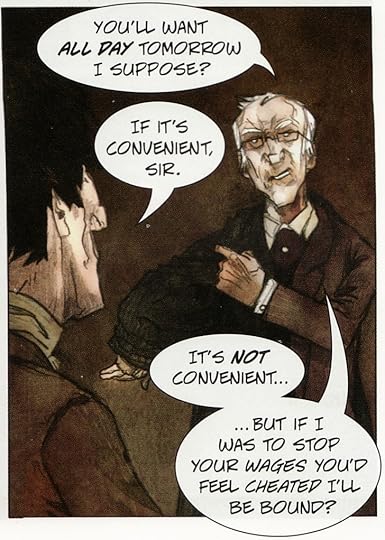

"If Quite Convenient, Sir" | A Christmas Carol: The Graphic Novel (2008)

Index of other entries in The Christmas Carol Project

A couple of things have marked Sean Michael Wilson and Mike Collins' adaptation so far. First, though Classical Comics labels it as the "Original Text Version," it does make cuts. That's also true in this year's scene and I'll try to stop bringing it up every year from now on. Especially since this year's scene uses the edits to correct a problem I had earlier on.

In the introduction to Scrooge, Wilson's adaptation edited out some of Dickens' text, but still used a great deal of it when Collins' art was already communicating the same thing. As the charitable solicitors leave Scrooge's office though, the comic devotes a whole page - mostly wordless - to following them into the street and seeing the celebrations going on outside. The page ends with a caption about the intense, biting cold, but the majority of the page is just street scenes, including the "ragged men and boys" warming their hands around a brazier.

People on the street don't appear to be either especially joyous or miserable. Most of them are just going about their business, although the brazier men are appropriately scowling at their condition. The text makes no overt comment about the dichotomy between rich and poor celebrants, but the message is still there in those men's faces.

Though the Classical version cuts some text, it faithfully includes all the story beats, including the little boy singing "God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen." Scrooge even grabs a ruler like he does in Dickens and the Marvel version, and the boy's reaction to that is pretty funny.

The second thing I've noticed in the Classical adaptation so far is that it's been hard to get a read on Scrooge and his relationship with Cratchit. I've enjoyed the extra space that this version gives the story, but Wilson and Collins haven't used it for character development. That changes a little with this scene. As in Dickens, Scrooge doesn't close up shop immediately after the caroller incident, but when it does become time to go, he's the one who makes the move.

Dickens mentions that Scrooge announces closing time, but he doesn't provide any dialogue for it. The first quote Dickens gives Scrooge in the scene is to ask if Cratchit needs the whole next day off. Wilson doesn't create dialogue where Dickens didn't, so it plays out a bit differently in this version. Instead of Scrooge's announcing the time, he just gets up, puts on his hat, and asks about the day off. That makes it seem like this is something Scrooge has been thinking about for a few minutes, as opposed to an off-handed comment. Collins draws Scrooge's face from the side and rear in this panel, so I can't tell what he's thinking, but it's possible to read a touch of sadness in him there, like he's been dreading this conversation.

For Cratchit's part, the clerk responds with chipper innocence. He seems almost clueless to Scrooge's grumping. There's no sense that he's incompetent - as suggested in the George C Scott version - but he may be dim-witted enough not to take Scrooge personally, even when Scrooge clearly means for Cratchit to. Or maybe Cratchit's just mature enough not to rise to to Scrooge's bait. It'll be interesting to see how this Cratchit behaves later in the story. Is he an idiot or just thick-skinned?

Whichever it is, Scrooge doesn't like that he's not getting his employee's goat and he gets angrier as the conversation progresses. By the end, he's impotently scowling as he orders Cratchit to "be here all the earlier next morning." It's an interesting power dynamic, because Scrooge clearly has all the power, but Cratchit is so not bothered by it that Scrooge doesn't actually benefit.

Like in Dickens, Cratchit gets to go home right after Scrooge and Collins draws Scrooge still skulking off down the street as Cratchit locks the front door. There's also a final panel of Cratchit's joyfully joining a couple of boys in a slide, further emphasizing how little effect Scrooge's mood has on him.

Published on December 07, 2014 04:00

December 6, 2014

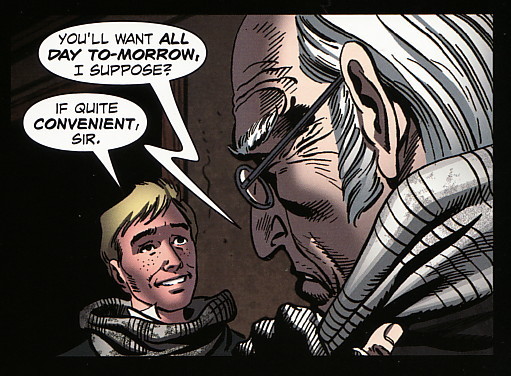

"If Quite Convenient, Sir" | Marvel Classic Comics #36 (1978)

Writer Doug Moench and the various artists he worked with on Marvel's version have already shown us a Christmas street scene in their introduction to Scrooge. It wasn't a very good one, because the art looked neither Christmasy nor even wintery. I complained about it at the time, because the scene looked so sunny and pleasant while the text claimed that it was "cold, bleak, biting weather." It's still a horrible mistake and bad comics, but if I was feeling charitable I could make a case for its being an intentional juxtaposition between the facts (it's miserably cold outside) and the way people feel about it (it's Christmas, so the weather doesn't bother us and we're acting as if it's beautiful).

As the solicitors leave Scrooge's office though, there's no contradiction. Moench tells us how cold it is and sure enough the artist for that page has some snow. The people on the street still look happy though, which is Dickens' point.

There's no sliding scene, but Moench does include the carolling boy and has him singing "God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen." Scrooge even grabs a ruler, which is a detail I expect most adaptations to change or skip over.

This version hasn't given us a clear vision of Scrooge and Cratchit's relationship yet, so I looked to this scene would give me some clues and sure enough I think it does. Scrooge brings up the day off in the same word balloon where he's still complaining about the singing kid. Maybe he's just on a roll and wants something else to complain about. He looks smug as he gripes, so he doesn't get any sympathy points for that.

Cratchit looks timid as he replies that it's only once a year. Unlike the Classics Illustrated version, there's an imbalance of power between these two men. Scrooge is going to let Cratchit take the day, but he's also going to make the process as uncomfortable for Cratchit as he can.

He also leaves first, making Cratchit stay behind to lock up. And since the comic leaves Cratchit there so that it can follow Scrooge, there's no indication that Cratchit is leaving right behind his boss. As far as the comic is concerned, Cratchit could have another hour or two of duties to perform while Scrooge runs off to begin his evening. As Scrooge exits, Cratchit is running his hand through his hair with an expression that reads mostly like he's perturbed.

That's a weird transition for Cratchit, from timid in one panel to perturbed in the next. But it's no less flighty than Fred was during his visit, or than Scrooge was while talking to the solicitors. The Marvel artists continue to have a hard time with consistency in their storytelling, so all the characters feel manic. Earlier, Cratchit looked cowardly when Scrooge fussed at him about the coal, but then had the bravery to clap and shout, "Bravo!" after Fred's speech. It's like he doesn't really know how to act appropriately around Scrooge. Which makes total sense if Scrooge is also prone to sudden mood changes (something that might run in his family, if Fred is any indication).

If we take Marvel's portrayal of these characters seriously, their Scrooge may actually be mentally ill. That casts a disturbing light on the whole story then as Scrooge has visions and experiences a dramatic change in personality, but it's a fascinating take, even if it's unintended by the storytellers. I'm going to use that as my working theory and see if it holds up as I keep reading the Marvel version.

Published on December 06, 2014 04:00

December 5, 2014

"If Quite Convenient, Sir" | Classics Illustrated #53 (1948)

In the interest of condensing the story to 45 pages, Classics Illustrated cuts out all the scene- and mood-setting, so there's no sliding scene or even a crowd scene on the street. There's not even an incident where Scrooge menaces any carollers. Instead, the comic goes straight from Scrooge's dismissal of the charitable solicitors to closing time.

Writer George D Lipscomb and artist Henry Kiefer have Scrooge and Cratchit leave the shop together, which fits with how they've portrayed the characters so far. Their Scrooge is a proud man who resents getting old and having less time to enjoy his wealth. Cratchit explicitly hates his job and his boss, but feels powerless to leave. Scrooge has threatened Cratchit's job a few times already; enough that Cratchit probably doesn't take him seriously. All that adds up to a couple of men who can't stand each other, but are aren't in any real danger of splitting up. They aren't at all equals in status, but they're more or less equals in power. Look at the way Cratchit openly glares at Scrooge in the second panel above. He can't stand the man and he's not afraid to show it.

When Scrooge brings up the day off, it's just a matter of making it official. He's not checking; he knows Cratchit must have it, but he also wants to remind Cratchit how he feels about it. His bringing it up is just his way of opening the door so he can complain. And Cratchit knows it, too. His "If quite convenient, sir" is a social obligation, but it's clear from his expression that he doesn't care if it's convenient or not.

There's no sympathy we're supposed to feel for this version of Scrooge. He's not actually miserable; he's just mean. He hates Christmas because the values it brings out in society are diametrically opposed to Scrooge's own. It's as simple as that and we're not meant to relate to him.

Published on December 05, 2014 04:00