Duane Vore's Blog, page 3

March 11, 2015

Lia London’s The Fargenstropple Case

What the heck is a Fargenstropple?

I’d never heard of one before this book either, and I’m guessing you haven’t. But you have to admit that it’s one of those words that promises something interesting behind it. Lia London first impressed me with Magian High, with her ability to construct a clever fantasy story that imparts valuable lessons to adolescents without offending them by letting them know she’s doing so. Then she impressed me with The Circle of Law, which wraps another rousing fantasy in profound wisdom. The Fargenstropple Case impresses me because … it’s funny.

I’d never heard of one before this book either, and I’m guessing you haven’t. But you have to admit that it’s one of those words that promises something interesting behind it. Lia London first impressed me with Magian High, with her ability to construct a clever fantasy story that imparts valuable lessons to adolescents without offending them by letting them know she’s doing so. Then she impressed me with The Circle of Law, which wraps another rousing fantasy in profound wisdom. The Fargenstropple Case impresses me because … it’s funny.

Understand that I have a problem with most comedy today. It usually falls into one or both of two categories: (1) it’s funny because it’s stupid, and (2) it’s funny because it’s dirty. I don’t know when stupidity became funny in America, but dirty being funny has been around for a long time. London doesn’t have to resort to either. I remember when things were funny because they were cleverly thought out, where a sequence of perfectly sensible events leaves the characters in a preposterous situation. I was just watching Lost Angel (1943)*, an overlooked gem staring a young Margaret O’Brien as a six-year-old genius named Alpha. That I’ve watched it before didn’t keep me from laughing all the way through.

Be sure to check out this clip:

OK, you might not be rolling on the floor, but that’s only because you don’t know all the background. Even my roommate Dave laughed all through it. But notice there is nothing idiotic or filthy involved. That’s the way comedy used to be, and that’s how London does comedy now. If you’re looking for mindless slapstick, mindless stupidity, or mindless smut, you won’t find it here. Actually, you won’t find those at all, with or without a mind. What you will find is humor with a triple-digit I.Q.

Ostensibly, it’s a mystery about a discomfited cat, but a mystery involving ferrets, a clever inventor kid, missing jewels, possible ghosts, and more. You don’t need to know any more about the plot than that before you read it. Let it unwind cleverly before your own eyes. And if it doesn’t elicit more than one chuckle, you may need to have your intelligence quotient examined.

* You can get both The Fargenstropple Case and Lost Angel at amazon.com, but I need to point out that the latter would not be possible without the good people at TCM.

The post Lia London’s The Fargenstropple Case appeared first on Duane Vore, Writer.

January 20, 2015

Protected: Download Korvoros – EPUB

This content is password protected. To view it please enter your password below:

Password:

The post Protected: Download Korvoros – EPUB appeared first on Duane Vore, Writer.

January 19, 2015

The Portable Writing Solution

My need for portable writing came abruptly: my laptop died. It wasn’t a spectacular death; it just refused to recognize that I had the power adapter plugged in. If the battery would charge, it would still work. I noticed this failure a while before it drained its last watt-second, and made provisions to stay in business pending other arrangements. I could work on computers at the library, but I needed more than my works in progress; I needed software that probably wasn’t installed there, beginning with Scrivener. That is where portable computing comes in.

What Is Portable software?

Portable software is software that works without being installed on the computer. Almost all software used to be portable, even for Windows computers. We computer geeks would carry around a floppy disk with essential tools on it for resurrecting a troubled system, with programs like FDISK, FORMAT, and CHKDSK on them. But then, Microsoft came up with something called “The Registry.” My initial reaction to it was one of utter revulsion. What a horrible idea! The software version of putting all your eggs in one basket. But we have to understand that whereas most operating systems were designed as operating systems, Microsoft Windows was designed as a product, and so had to appeal to mass consumers who didn’t know much about software. People could “install” the software, which threaded complicated tendrils through The Registry, so that most everything would “just work.”

Portable software is software that works without being installed on the computer. Almost all software used to be portable, even for Windows computers. We computer geeks would carry around a floppy disk with essential tools on it for resurrecting a troubled system, with programs like FDISK, FORMAT, and CHKDSK on them. But then, Microsoft came up with something called “The Registry.” My initial reaction to it was one of utter revulsion. What a horrible idea! The software version of putting all your eggs in one basket. But we have to understand that whereas most operating systems were designed as operating systems, Microsoft Windows was designed as a product, and so had to appeal to mass consumers who didn’t know much about software. People could “install” the software, which threaded complicated tendrils through The Registry, so that most everything would “just work.”

The downside is that much of this software won’t “just work” at all unless it is actually installed, and library patrons just don’t have the authority to install anything on public computers. If they did, all those computers would be infested with games and viruses (the two often go together). So I had to gamble that the software I used would work portably, without installation, and I proved to be lucky beyond my dreams.

What I Did

What I did is essentially what you should do if you suspect the need to go this way. The first is to make regular backups of everything you are working on, but you should be doing that regardless. A couple of USB flash drives are great for that, and sure beat the floppy disks of the ’70s. I use a close relative: a collection of SD cards and a USB adapter for computers that don’t have built-in SD card readers. I also keep a backup on an external USB hard drive.

What I did is essentially what you should do if you suspect the need to go this way. The first is to make regular backups of everything you are working on, but you should be doing that regardless. A couple of USB flash drives are great for that, and sure beat the floppy disks of the ’70s. I use a close relative: a collection of SD cards and a USB adapter for computers that don’t have built-in SD card readers. I also keep a backup on an external USB hard drive.

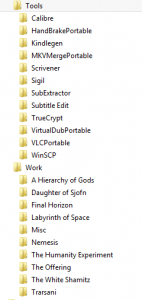

Before my laptop breathed its last, I copied all my works in progress, and the program folders of all the software I needed, none of which come with a portable installation. For my own sanity, I separated them into two collections, “works” and “tools.” How you organize them is your business. The fact that my directory tree shown here has a lot more than writing tools attests to my doing more things than just writing. At the local library, I tested all the applications to make sure they would work without being installed, and here is what I discovered.

The Results

Scrivener

Pass!

It works, but with some downsides. The first time I tried it, of course, it asked for my registration information, and I gladly complied. The problem was, it asked for it the next time I used it on that computer; it must use The Registry to store that information, and I didn’t have the authority to change the registry. Fortunately, if you don’t give it your info, and use it in trial mode, it comes up with 30 days left every single time you fire it up. I hope Literature & Latte doesn’t “fix” this, because there are many of us who believe all software should be able to run portably. I’ll keep a copy of this version just in case.

The other downside is that if you customize anything, such as the toolbars, you’ll have to customize it all again the next time you run it. You lose that information between sessions. Fortunately, it remembers your settings for compilation. It must save these with the document instead of the registry. It also doesn’t remember what you had open last time.

Sigil

Pass!

If you don’t prepare your own e-books beyond compiling them from Scrivener, you might not be familiar with this one. It’s an EPUB editor, and I use it extensively. I tried to explain a little about it here. Sigil is how I get my pages to look the way I want them to instead of the way Scrivener wants them to. Scrivener could use some customization capability in how it generates HTML, but that’s another rant. Sigil also loses memory of what you had open last time.

Calibre

Pass!

I don’t use Calibre that much. I don’t have much use for its library system, but do use it on occasion for converting between formats, even though the library feature gets in the way of that. I missed copying one of my works in progress, and had to pull the latest revision off my Kindle and convert it from MOBI to RTF so I could import it into Scrivener again. A day or two wasted, but that’s better than a year. Like the others, it’s quite forgetful between sessions.

Kindlegen

Pass!

Yes, Amazon will automatically convert an EPUB document to Kindle format when you upload it, but I go through several revisions, using my Kindle Touch as a proofing tool, so I need to convert them to MOBI myself. Since Amazon created Kindlegen, I figure it’s the best tool to use to do that. Kindlegen is a command-line tool, so it’s obvious to a computer geek that it should work in portable mode. Kindlegen doesn’t remember anything in the first place.

WinSCP

Pass!

Part of writing is maintaining your web site, and often I need to manually upload files to my server. I also back-up copies of my work in a protected directory on my server; off-site backup is crucial. What if your house burns down?

So that’s it. Everything works, so I was barely slowed down in the interval before I got another computer, other than the time I spent hiking to and from the library (about four blocks). Setting up an emergency work environment such as I did is cheap insurance for any writer.

The post The Portable Writing Solution appeared first on Duane Vore, Writer.

December 20, 2014

What is Hard Sci-Fi?

We all know what hard sci-fi is, don’t we? It’s that … well…. I thought I knew what it was until I visited KindleBoards, which I don’t do nearly as often as I should, and checked in on a thread I’d commented on. Another member had said that he read mostly hard science fiction, biographies, and science, and that writers of those were quite rare. I was immediately delighted because I write hard sci-fi — don’t I? — and that makes me a rare commodity. But after a moment’s thought, I asked myself, “Do I?” After all, who’s to say that his definition matches mine, or that either matches the science fiction community at large?

So I put my occasionally competent mind to work analyzing exactly what constitutes hard sci-fi, because, as we all know, even Wikipedia definitions are suspect. I’m sure was can agree that hard sci-fi requires attention to the scientific and technical details of the universe in which we live and of the gizmos we fabricate to let us live and get around in it, but even that definition can provoke different images in different minds. Let’s examine three potentialities.

Hard Sci-Fi as Scientific and Technical Reality

There can be the opinion that in order to be hard, science fiction must reflect an accurate view of physical reality. It should take note that on an Earth-Mars transit, one has to calculate orbital perturbations caused by other planets, most notably Jupiter. I didn’t do that in A Hierarchy of Gods. I calculated a constant one-gravity acceleration path with turn-around for the distance when the novel takes place. Orbital perturbations? Heck, it’s 2076; computers take care of that.

One of NASA’s visions for a moon base. We can assume some technical competence from them.

Taken to the limit, this definition of hard sci-fi leads to mundane science fiction. While it is perfectly OK for any particular story to be mundane, I rant rabidly against it as a movement here. If all science fiction went this far in the pursuit of scientific and technical accuracy, we wouldn’t have 2001: A Space Odyssey, Foundation and Empire, or the Lensmen. The giants of science fiction would be completely unknown, and we’d be stuck in low-Earth-orbit limbo forever. I argue elsewhere that we need not adhere to known science.

Hard Sci-Fi as Scientific and Technical Precision

I use the word precision here much as any scientist would. The first definition above corresponds to accuracy, i.e., that the content of the story reflects the “truth,” what is actually known about science and technology. Precision here means that although the content of the story might not be accurate, such as allowing for warp drives and artificial consciousness, it is nevertheless precise in that it represents science in high detail, to several decimal places.

In Korvoros, I make note that space rarefaction as used by the Free Space Alliance proves that Einsteinian relativity is incomplete because that warp technology requires the existence of absolute space, as indeed it really would. For A Hierarchy of Gods, I wrote a Mathematica script to give me both Earth time and ship time for constant acceleration relativistic flight at n gravities for m light-years. In The White Shamitz, I discuss how the absence of inertia leads to the absence of direction (Google Noether’s Theorem and the conservation of linear momentum.) I make things up, which is actually the basis of science fiction to begin with, but I do my best to make sure that what I make up makes sense in a logically consistent universe. I don’t write much Alice in Wonderland stuff.

Hard Sci-Fi as Scientific and Technical Ubiquity

Consider Star Wars. With the exception of Dagobah, Hoth, some remote locations on Tatooine, and a few other choice settings, we are surrounded constantly with technology. Spaceships with excessive greebling everywhere. Machines on the walls. Machines on peoples’ chests. People who are machines. They never show a toilet, but I’m sure that if they did, it would have artificial intelligence and a complex flush processor. See how many doors have hinges and a doorknob, though in virtually any conceivable society, that configuration is probably the most practical and efficient one. Hardware is everywhere, and the bigger the better.

However, the Star Wars universe doesn’t concern itself with the science that goes into all that technology. In fact, except for the midichlorians, which are so lame that they send any biochemist, geneticist, or molecular biologist in the known universe rushing to the outhouse to retch, I am not aware of any serious attempt to explain any of the technology we see. It’s just there, like magic. For this reason, I have argued that Star Wars isn’t science fiction at all, but fantasy. Hyperdrive just works, no physics involved. Light sabers just work, no physics involved. If a component of any device comes up at all, it’s just a word pulled randomly from a writer’s imagination. Don’t get me wrong; I like Star Wars. But I like it as a fantasy quest story. As any kind of serious science fiction, it leaves a bit to be desired.

The Verdict

At some point, we have to get down to the nitty-gritty: do I write hard sci-fi? If you’ve read this far, you realized that I’ve already rejected two of the three definitions I propose, the first because it chokes creativity and makes some of the most popular science fiction impossible, and the third because it’s inherently unsatisfying and includes little actual science. If the second is the true definition, I conclude that, yes, I write hard sci-fi.

I did a quick Google search and found this rather interesting list of hard sci-fi books, many of which I’ve read. So I took a few minutes to compare what I write with some of those authors.

Arthur C. Clarke: 2001: A Space Odyssey

This was one of those “Wow!” books that I read as a youth. I remember life aboard the Discovery One, the monoliths, Grand Central Station, the Star Child. I particularly remember the detail that went into the design of the ship, and how it made so much sense to me, a young engineer at the time. That detail added to the realism. It is the only fictional spaceship I can think of that considers thermodynamics in its design. I remember that the sides of the monoliths were in the ratio 1:4:9, the squares of the first three integers and how Bowman realized that it was silly to think that intelligent beings so advanced as their builders had any reason to stop at three dimensions. I remember how the second obelisk was designated TMA-2 (Tycho Magnetic Anomaly 2), and how Bowman comments that it was a double misnomer because it was neither in the Tycho crater nor did it emit a magnetic field. Sure the whole hyperspace scene (two chapters, as I recall) was all a writer’s pipe dream, but Clarke didn’t miss the technical details. He never did.

The K7 ship in my novel A Hierarchy of Gods is rather like the Discovery One, a point I make note of in the text. I thought out its construction as thoroughly as I needed to, down to the access details of the carriage centrifuge and the pressure sensors on the double hull. I don’t have any hyperspatial highways (those show up in the next book) but I have alien unit field technology that while not completely explained is discussed as if Nekalee knows exactly how it works. She does. Strangely, when Clarke wrote the sequel, 2010: Odyssey Two, he moved the location of TMA-2 from Saturn to Jupiter to match the movie. I never would have done that; it’s an inconsistency I simply cannot abide.

If Clarke was a hard sci-fi writer, so am I.

Larry Niven: Protector

Protector was another “Wow!” book. I remember most the idea of a second “puberty” where human “breeders” (a consequence of the first puberty) are supposed to transform into protectors, but in our case it failed because of a missing nutrient. That blew me away. And I remember Phssthpok (I had to look up that spelling) and how he made the 30,000-year journey from his home world to Earth using solar sail technology. I don’t remember for sure if Niven considered relativistic time dilation, but I’m sure he did, and either way, the poor fellow sat in that pilot’s seat for a long, long time.

Jaxidreshy’s wand. The 3D model actually has the major components inside.

I’ve thought out alien species just as well as Niven. The Kyattoni outwardly look as if they could be human, but instead of two puberties they have none at all, and possess other biological differences that deeply affect their culture. Interestingly, they have absolutely polarized heterosexual orientation and yet no concept of gender identity. To get things done, they use a device translated loosely as a “wand,” which can instantiate matter to the seventh order. You might think that sounds something akin to a light saber, except that I have a 3DS-Max model of the thing’s internal structure. I know how it works, and that humans won’t be able to build one for 100,000 years.

If Niven is a hard sci-fi writer, so am I.

Isaac Asimov: Robots of Dawn

Yet a third “Wow!” book, and what wowed me about it is that Asimov was able to so flawlessly merge his Robot and Foundation stories into one as though he had planned it that way from the beginning. As usual with hard sci-fi, he goes into detail about the construction of spaceships and robots. Maybe this book was a double wow, because I, Robot wowed me to begin with in that he was able to create the Three Laws of Robotics and fill an entire book with short stories about the varied and sometimes surprising ramifications of them. It is interesting that the 2004 film of the same name successfully captured the gist of the book while making not the slightest attempt to follow the plots.

From a physicist’s point of view, Asimov’s positronic brain is complete nonsense. It’s a case of throwing in a cool word like positron and settling on that as an explanation of how they work. But as a writer, you have to do something; if we really knew how to build such a brain, we’d have them. I have an electrophotonic brain in Daughter of Sjøfn (working title), and cerebrotronic brains in Korvoros, both of which I go into greater detail about than Asimov, but in all fairness, scientific advances since his day have provided me with more coal to heap upon the fire of speculation.

If Asimov was a hard sci-fi writer, so am I.

There can be an other argument that hard sci-fi is technology-driven and not character-driven. You can latch onto that one if you want, but I won’t give it the time of day. There is nothing amiss about having both.

So yes, I can, without prejudice, count myself among other hard science fiction writers. I might not be as profound, and I certainly don’t have the sales, but the kind of thought that goes into my books is a sibling to the kind that went into some of the truly remarkable science fiction novels that grace the literary landscape. If you want to see just how far I’ll go in creating my universes check out molecular genetics. And it may be that an explanation for all this is at hand. Asimov was a biochemist; my degree is in physical chemistry with a focus on biochemical systems. Clark had a degree in mathematics and physics, and Niven did postgraduate work in mathematics. I also have a decades-long background in electronics and software engineering.

I don’t know this as a fact, and might be encouraged to do some research on it, but I suspect strongly that science fiction writers with backgrounds in science or engineering are more likely to turn out technically and scientifically attentive works. It’s part of the mindset. A doctor asks me, “Is the medicine working?” and my first reaction is, “I don’t know. There’s no control.” If you spend your working day thinking in logical detail, it almost has to come through in your works. Just as linguist J.R.R. Tolkien couldn’t help but invent languages for Middle Earth, neither can we real-life geeks keep the geekiness out of our creations.

The post What is Hard Sci-Fi? appeared first on Duane Vore, Writer.

November 17, 2014

A Tribute to Teachers and Librarians

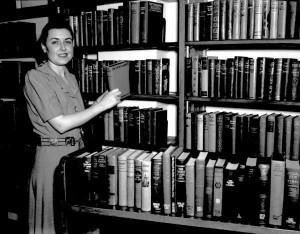

Get your mind off of whatever it’s on at the moment and pay attention to the people responsible for your having a mind worth anything at all: teachers and librarians.

Writing any fiction at all requires knowing something about the setting, local mores, police procedures, the distance from Oslo to Bergen, or whatever else the story requires. Writing science fiction goes even further, requiring perhaps the dimensions of Jupiter’s rings (The White Shamitz), non-natural DNA analogs (The Humanity Experiment), or relativistic mechanics (A Hierarchy of Gods). In fact, it helps to be a scientist. Nor is fantasy immune. You do know the difference between brass and bronze, don’t you, and between catapults and ballistas? Between castles and palaces?

The common theme here is knowledge. Even if you’re not a writer, knowledge comes in useful if you want to balance a checkbook, read a recipe, or change your oil. We live in a world where knowledge is essential. Therefore, let’s take a moment to honor two important repositories and administrators of knowledge: teachers and librarians.

Our society is not only complex; it is capricious. We bestow honor upon actors and sports stars, paying them often millions of dollars when, frankly, they’re completely unnecessary. We bestow honor upon the idle rich of the world, whose main contribution seems to be to take up space in the gossip column. But when it comes to the people without whom our society would collapse — the garbage collectors, the firefighters, the teachers and librarians — we pay them a pittance and pretend they don’t exist. When’s the last time you’ve seen a librarian on the cover of People magazine?

Teachers

A lot of parents seem to see teachers as free daytime babysitters. Don’t dispute the point, because I’ve known parents to come out and say it. They often feel the same way about Scout leaders, sports coaches, and youth ministers. I know. Been there; done that.

Mostly, these people don’t mind; it’s part of what you sign up for. People who know me also know that I’ve devoted a significant fraction of my life to children, as a Sunday school and CCD teacher, as a Scout leader, as an adventure educator, as a youth advocate, and on occasion as a counselor or rescuer. Not for the money or the recognition, but simply because our children are important. Even if they’re actually someone else’s. There is sound philosophical and scientific justification for believing that we are programmed to want to nurture children, and I can’t help but wonder about people who don’t.

I’ve met some teachers who don’t like children, which makes me question what they’re doing in that line of work. However, it may be that their joy comes from the other side of the equation, the part that is the focus of this post: passing out knowledge.

Throughout my public school life as a minor, I loved science and mathematics, not surprisingly, but couldn’t see much point in Ohio history and diagramming sentences. Diagramming sentences has since come to be a delight, but at 15, I was clueless. Likewise, general education requirements in college are a constant thorn in the sides of students. Yes, I wondered why I needed economics and non-western social systems to practice physics (my change to chemistry came later.) But now, I understand what educators then understood: that physics and chemistry are not practiced in a vacuum; they are practiced in the context of a society.

Whatever field a person chooses, he will need to be able to read and write, and should have at least a little competence in understanding the world around them. If we are going to practice science and engineering within the scope of a society, then we should know something about that society. It dismays me that they have to put some of the warnings they do on products. “Do Not Eat.” Seriously? It dismays me further that people go to the polls and vote based on television commercials and not on fundamental knowledge of economics, sociology, and political science.

That is the role of teachers: to equip the next generation with an essential toolkit of skills to function effectively in the modern world. They produce the citizens who keep our world working.

Librarians

Teachers are the first line of defense against ignorance, but there is another, broader, battle front. When you graduate from high school, or college, or a Ph.D. program, even with a 4.00 GPA, you come out knowing just the most miniscule iota of knowledge that our species possesses today. As a teen, I fantasized of knowing everything about science. Hah! Fat chance! I hold a master’s degree in physical chemistry, with applications to biochemical systems. One of the books I own is the definitive reference on 2-dimensional infrared spectroscopy, yet I probably know no more than 20% of what there is to know about it.

Teachers are the first line of defense against ignorance, but there is another, broader, battle front. When you graduate from high school, or college, or a Ph.D. program, even with a 4.00 GPA, you come out knowing just the most miniscule iota of knowledge that our species possesses today. As a teen, I fantasized of knowing everything about science. Hah! Fat chance! I hold a master’s degree in physical chemistry, with applications to biochemical systems. One of the books I own is the definitive reference on 2-dimensional infrared spectroscopy, yet I probably know no more than 20% of what there is to know about it.

If you intend to engage in any project that extends beyond the mere essentials of survival — forming a nonprofit corporation, creating a video game, or building a deck — you will need knowledge that they didn’t teach in school. That’s where librarians come in.

You might argue that in this day and age, we have Google. But let me try to say this delicately. Google is dumb. It can’t search for knowledge; it only searches for words. I recall an episode many years ago when I was searching for information on adventure education for girls (Janelle will know why). Because I included the word girls, I got back about 200 pages of porn sites, and had to exclude just about every word ever used to refer to a portion of female anatomy to get any useful results. The science of search engine optimization is dedicated to getting your site to appear at the top of the list regardless of what a person actually wants to see.

There is so much information available that you are likely never to find what you need without help, and Google doesn’t always cut it. In grad school, I had access to SciFinder, American Chemical Society abstracts, and more, but even so, I had to spend hours with one of the chemistry librarians to help me wade through the morass. Yes, there are specialized subject librarians. There is a vast amount of knowledge available on the Internet, but there is also a vast amount of knowledge not available on the Internet. You can get to the generalities fairly easily on your own, but when you get to the point of needing the specifics, such as the plasmon patterns on the surface of a gold nanocube, or a map of Paris in 1752, a librarian may be your only hope.

You might enjoy your Playstation 4, your cell phone, your sports car, or even your shampoo. If I mentioned that building a Playstation requires knowledge about solid-state lasers, servomechanisms, XYZ-UVW texture mapping, matrix calculation algorithms, and large-scale semiconductor fabrication at nanoscale resolutions, I would be just scratching the surface. More knowledge went into that design than it is even possible for any one person to know.

You would not have it if teachers and librarians had not prepared the way.

I can write properly because a teacher taught me the difference between a gerund and a participle. I found out what I needed to about bacterial siderophores because a librarian got me access to journals that couldn’t even find by myself.

Teachers and librarians are the distributors and guardians of the knowledge upon which modern society is built. They hold the future in their pockets, open the gateway to imagination, and carry the keys to inspiration. It is not unreasonable to say that they are one of the backbones of our world, yet how often do we even hear of them? We only discuss teachers as though they are to blame for the state of our educational system (they’re not) and librarians never at all.

Yet there they remain, keeping our society afloat with virtually no recognition that they are doing so, while we sit stupidly and focus our enthusiasm on the latest flash-in-the-pan rap singer, who is indisputably unnecessary. It is high time that we gave credit where it’s due.

So reserve this moment for a standing ovation. The next time you see one, let him or her know just how much you appreciate the contribution they make to society. Those few seconds will be much more important and rewarding than buying another football ticket so your favorite quarterback can buy another condo.

The post A Tribute to Teachers and Librarians appeared first on Duane Vore, Writer.

September 4, 2014

Trarsa: A Survey of an Advanced World

For 65,000 years, Trarsa was the dominant civilization in the known universe and the effective leader of the Triumvirate. As such, it was the center of intergalactic civilization for more than 60,000 years. Today, as the home of Nekalee and Ritee of A Hierarchy of Gods, who figure prominently in the history of the universe, Trarsa remains a planet of primary significance.

Physical features of Trarsa

Astrography

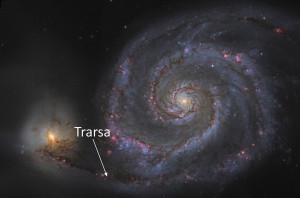

Figure 1: The approximate location of Trarsa.

Trarsa is located near an active star-forming region in the tidal bridge between the two colliding galaxies known in Earth nomenclature as M51. It is impossible to identify the exact placement from Earth because we see the galaxies as they were 23 million years ago, and in the time between then and now, they have drifted further apart. The illustration here should be considered only an approximation.

Trarsa orbits a class F8-V star slightly hotter and more massive than Earth’s. Its orbit is about 20% larger, but the greater stellar mass brings the length of the Trarsan year down to only 1.09 Earth years. The planet averages about 2°C warmer than Earth, but this is enough that Trarsa has minimal ice caps. The planetary inclination of only 0.5° leaves the world without noticeable seasons. The eccentricity of the orbit today is 0.005, and varies little throughout the eras.

The Trarsan day is shorter than ours, about 21.5 hours. Nekalee adapted to the longer day on Earth better than Ritee, which in part accounts for why Ritee was sleeping at odd times.

Moons

Trarsa is unusual for an Earth-like planet in that it has seven moons. All are smaller than Earth’s moon, and the nearest is less than half as distant, but its angular diameter remains smaller at about 1/4°. Orbital periods range from about 12 Earth days to 183 Earth days. The nearest moon is the largest, but the most distant is fairly large too, and remains an obvious disk in the sky.

Figure 2: Trarsa, showing the eclipse shadow of the nearest moon.

The inclination of the moons’ orbits, like the inclination of Trarsa itself, is quite small, all of them less than a degree. This has two consequences to observers on the planet. For those living near the equator, solar eclipses are quite common. However, because the moons are significantly smaller than Earth’s and the angular diameter of their star only slightly smaller than our sun, total eclipses are not possible. Therefore, all of the eclipses are partial. Figure 2 shows the shadow of one such eclipse.

The other consequence is that the inner five moons are always eclipsed by the planet when they are in opposition, so they are never seen full. The outer two moons, far enough out to escape the shadow of Trarsa, can appear full, but the sixth moon is so small that is just a spot in the sky like Jupiter from Earth. Early in Trarsani history, there was the notion of a month beginning on the date that the innermost moon emerged from eclipse, but as the period of that moon is only 12 days, it is comparable to a week as well. As the Trarsani developed, they abandoned that usage except as an item of historical curiosity.

Geography of Trarsa

Environment

Trarsa is smaller than Earth, having a surface gravity of about 0.8 of ours. There is relatively more water than on Earth, covering about 85% of the surface, and the continents tend to be narrow, running in a southwest to northeast direction having mountainous backbones. Being warmer and having a larger surface of water, the relative humidity is consistently higher and the precipitation greater and more regular. As a consequence, nearly all land area is covered in dense vegetation. The Trarsani concept of a desert is rather like Kansas.

The warmer temperatures and higher humidity content of the Trarsan atmosphere leads to more violent weather than is common on Earth. High winds exceeding 100 km/hr and deluginous rain are almost a daily experience. Clouds almost always mean a downpour, but forest occupants miss much of it because most of the water ends up funneled down the tree trunks. Such a large volume of water results in hundreds of fairly short but torrential rivers creating waterfalls that surpass all the records held by Earth. The forests, though are hardly affected, as the trees have suffered this weather for millions of years. The weather is one of the reasons that the Trarsani build their cities in the deep forests or on the leeward sides of mountain ranges, or underground.

Figure 3: Litlanesfoss, Iceland, representative of hundreds of higher-altitude waterfalls on Trarsa

Trarsa is more geologically active than Earth. Earthquakes are more common, but fault lines usually do not build up the degree of tension that they do on Earth, so they are rarely severe. Violent volcanic activity is virtually unknown, but on the geologic scale there has been a large amount of lava flow. This has resulted in relatively more basalt exposed at the surface, so basaltic columns are common. Combined with the extensive river system and its waterfalls make scenes similar to that in Figure 3 commonplace. Imagine, if you will, an entire planet that looks like Hawaii.

Flora and fauna

About 90% of Trarsa’s land surface below alpine regions is covered with forest. Only the polar regions of Keelee and Lunee and high altitudes are without trees. Most of the trees resemble terrestrial cycads in that they are tall and straight with a lush fern-like head of leaves at the top. However, they differ from cycads in two important ways. First, they are flowering plants. Many have flowers one to two meters in diameter suspended from the canopy and fertilized by a variety of insects, most famously the lesso, which resemble a large cross between butterflies and dragonflies. Second, the trees are massive, typically reaching diameters of as much as 15 meters and heights of 300 meters, about the height of an 80-storey skyscraper.

The forest floors are an ecosystem unto themselves, dominated by chemoorganoheterotrophs. Fern-like plants similar to the Earth variety, and large horsetail-like plants resembling Earth’s prehistoric calamitaceae are abundant, but there is a wide variety of plant life that in the past supported farming, and large woody grasses similar to bamboo. The “horsetails” and “bamboo” were once used as building materials.

There being no significant climatic difference throughout the year, trees never had to figure out whether to be deciduous or evergreen. In fact, there are very few life forms, either flora or fauna, whose life cycles are synchronized to the year. There are baby birds all year around. Diurnal cycles, of course, remain as with virtually all worlds.

The Trarsani

Biology

The Trarsani are the most neotenous Population-K race in the universe. On the outside, they appear almost exactly like human 10-year-olds, and unlike the Kyattoni, whose mixed signals consistently confound any human who attempts to recognize an age in one, the illusion is nearly perfect. You could throw a Trarsani adult into any fifth-grade class on Earth, and aside from almost certainly knowing more than the teacher, you would never suspect anything odd. The Trarsani have no facial hair, and aside from pubic hair, there is no increase in body hair with puberty.

On a mass basis, the Trarsani are about 35% stronger than humans. When Ritee and Nekalee were on Earth with its greater gravity, this just about balanced out and left them only slightly relatively more robust than Lesley. But at home, with lower gravity, they have a much greater strength reserve than humans. Most would think little of climbing 100 meters up a city tree.

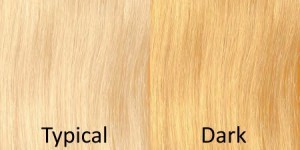

Figure 4: Typical and dark Trarsani hair color

The Trarsani are a forest species. The thick forest canopy blocks most of the light from reaching the ground. As such, they rarely experience direct exposure to their star; although they may climb to the treetops at night, many have never seen their star. As such, they universally possess light pigmentation, almost white-skinned and blond haired. Figure 4 shows typical and dark Trarsani hair color. Lighter hair reaches nearly white or silver. Ritee and Nekalee are typical to light. The square cross-section of Trarsani hair yields an iridescent effect in bright light. Eye color ranges from green to light purple, with blue being the most common. Sometimes the blue is a quite deep and striking.

The Trarsani have 23% more brain cells than humans. Most of that difference is in the cerebral cortex, and the remainder in certain regions of the limbic system. Not surprisingly, the Trarsani have a higher average I.Q. than humans, the mean being about 150 on the human scale. We should note that Lesley Kellerman’s I.Q. is cataloged at 155, which places him more intelligent than the average Trarsani. Nekalee, for the record, weighs in at 210.

Civilization

As with all highly neotenous species, the Trarsani are non-competitive, meaning they are completely cooperative. As a consequence, they have no laws as we know them and never invented anything resembling money. The closest they have to laws are protocols, and there are no penalties for failure to follow them. They have no police, no armies, no financial industry, no wages or prices, and no crime.

Figure 5: Map of Trarsa

Unlike the Kyattoni, who concentrate their population into large metropolitan centers, the Trarsani are distributed all over the planet. However, the world still looks virgin from orbit. Since ancient times, the Trarsani built communities in the trees, rather like the Ewoks of Star Wars fame. They still do, and thousands of tree cities dot the planet. Only now, they are made with modern meta-materials and not woody “horsetails” and “bamboo”. Where there are no trees, the Trarsani have built entire cities underground, these developing for the most part after technology made it feasible. However, there is archaeological evidence of underground dwellers in ancient times.

Figure 5 shows some major features of Trarsa. Trarsa has no capital city, as they have no government as we know it. Furthermore, technology is now so advanced that almost all cooperative projects can be managed without regard to location.

Ashlee-Laka is the home of Nekalee and Ritee. It is a smaller tree city with a population of about 200,000, but also one of the oldest, having a verified history dating back to before Trarsa’s space era, almost 140,000 years. Atalatha, with a population of about 10,000,000, is also an old tree city, but is significant because it is the location of Trarsa’s space fleet. It is one of the few locations where the forest has been cleared for another purpose. Basakala is an intermediate-sized city of about 1,000,000, and is representative of new cities built almost entirely underground.

History

The earliest settlements have been unearthed on Milee, dating back some 150,000 years. The species spread rapidly, and over a period of several thousand years had migrated to Keelee, then gradually northward to Aeelee and Teekee. The violent weather of Trarsa delayed seafaring by centuries, and ancient migration was only possible because of the thousands of closely spaced islands linking these continents. The hundreds of miles of open sea connecting settled areas to Analee and Lunee effectively isolated them until technology advanced to the point of mechanised travel. At various points in history, ice bridges have connected the southern regions of Keelee and Lunee, but there is no evidence that early Trarsani ever made any attempts to cross them, and at any rate may not have been able to do so.

Air travel likewise was delayed, as flights more than a few hours could be lethal. Global air travel did not become practical until the development of advanced supersonic transport. The remote island areas were not settled until the Trarsani reached a level comparable to 21st century Earth, about 135,000 years ago.

Space travel started similarly as with humans, but in general, because of their higher average intelligence, technological development proceeded much more rapidly despite their much lower population. Effectively, every Trarsani is a scientist. Efficient fusion engines came about relatively sooner, and as of that time they became independent of the weather. It was only 50 years between the invention of fusion power and the first rudimentary warp drives, and at that time interstellar exploration commenced. The Trarsani, unlike humans, never had any interest in colonizing other worlds, though they were adept at exploring.

Armed with second-order unit field technology, it was Trarsa that discovered Kria-Ki and Kyatton, both having at the time first-order technology. Naturally, Trarsa became the dominant member of their affiliation, the Triumvirate. They remained the dominant member until the Dissolution approximately 75,000 years ago.

Relationships

The Trarsani, in general, are quite open and friendly. As with humans, children live with their parents until they find a mate, then establish their own households. However, unlike humans, they rarely move far away from their place of birth unless two from different locations become mates. Extended family relationships are important, but they do not recognize a need to discriminate family identity and therefore do not see a need for family names. They see nothing there to document.

The Trarsani are absolutely heterosexual and lifetime monogamous, the latter being a trait associated with the more developed limbic regions. Siblings are not quite as close as Kyattoni siblings, but still much more so than typical humans. A sibling’s mate is considered a sibling as well. Although not typical, is also not a violation of privacy for a brother or sister to be present during lovemaking, and not a violation of monogamy for a sibling to “help” on rare occasions, as doing so does not affect the love relationship between a couple. Such is more of a tradition on Aeelee and Teekee than elsewhere.

Being a non-competitive species, the Trarsani have no concept of social stratification. Consequently, all relationships are equal. If there is any notion of a “senior” partner it is only from the standpoint of experience. Although they do have gender identity (maleness and femaleness beyond structural biology) there is little expression of it other than that females usually wear their hair longer. (This is a trend across Population-K species in general, and is not understood.) There are no gender roles and no gender-specific clothing.

Language

Modern Trarsani is a constructed language based primarily on the ancient languages of Milee and southern Keelee. More information about the structure of Trarsani is available here. Because of the difference in psychology, human words related to law, money, war, hatred, or related concepts are often non-translatable. The expression translated as “The Enemy” in A Hierarchy of Gods is not native Trarsani, but was coined by Ritee’s translator. The native Trarsani is more like, “The ones who destroy life.”

Overall, the Trarsani are more like humans than the Kyattoni.

Challenge

The Trarsani have intergalactic travel and materialize most of their needs out of energy. What would you predict is the most common means of personal mechanized transport on Trarsa?

Teleportation

Bicycles

Hover platforms

Turbolifts

Spoiler Inside: Answer hidden here

Show</>

Bicycles. The Trarsani’s large strength reserve facilitates their use, and the Trarsani appreciate it as being “close to nature.” They generally resemble terrestrial bicycles, but the tires have perfect friction and last forever, and there are no chains or cables. The power all comes from the rider’s muscles, but how it is transmitted would be a great mystery to human scientists.

The post Trarsa: A Survey of an Advanced World appeared first on Duane Vore, Writer.

June 30, 2014

Blog Tour: Lesley Kellerman

I was inducted into this Blog Tour project by Thaddeus White, a crafter of adult fantasy and colorful worlds to put it in. Thaddeus holds a special place in the literary realm for me because although I’ve been writing for a long, long time and was preparing to self-publish my books (there are eight written), I had never thought to read any self-published works until his Bane of Souls. I learned in that moment that one does not have to buy traditionally published books to get a great story.

You can meet Thaddeus thus:

Blog: http://thaddeusthesixth.blogspot.com/

Twitter: @MorrisF1

Amazon:

www.amazon.com/Sir-Edrics-Temple-Adventures-Edric-ebook/dp/B00GCAF2CI/

www.amazon.co.uk/Sir-Edrics-Temple-Adventures-Edric-ebook/dp/B00GCAF2CI/

Now for my entry into this shindig:

1) What is the name of your character? Is he/she fictional or a historic person?

He might not look like it, but Lesley Kellerman is a junior at Cornell University. You can call him fictional if you want, but I’m sure that would annoy him if he knew. He already has trouble taking himself seriously.

2) When and where is the story set?

The story takes place in 2076, but I don’t ever mention the exact date, as it is important only to the placement of planets and therefore just fell out of background research. Geographically, most of it is set in and around Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, but fate eventually takes the main characters to Mars Station, to the very edge of the Solar System, and beyond. Now, look! You forced a spoiler out of me. Shame on you!

3) What should we know about him/her?

3) What should we know about him/her?Aside from being self-conscious about not being able to grow facial hair, he is a computer science student, and doing quite well with his project. He calls it ACE, Artificial Cognition Experiment. He hopes to be the first person to be able to program a computer with a conscience, but he’s having a problem with that because he hasn’t been able to to define exactly what right and wrong are in his own life. He is still working on that and the problem frequently occupies his thoughts.

4) What is the main conflict? What messes up his/her life?

He is in the Ruins, the southern tip of Manhattan that was devastated by a nuclear attack during the 30-second war. But that’s old history. While there, he rescues two little girls from the clutches of a would-be rapist only to find out that they aren’t little girls at all. One of them, Nekalee, is a year older than he is. In fact, they’re not even human, but from a distant civilization that was in space before humans invented clothing. Exactly why they look human, and why there are full-grown adults who look like human children, are themes that follow the series through to its conclusion.

Lesley is faced with the struggle between the moral obligation to protect them and help them get home, and the repressive laws of Academy society that make doing so dangerously illegal. He has to face the fact that what is right isn’t necessarily what is lawful, especially when it comes to illegal fraternization with the opposite sex, academic fraud, and the theft of an Academy spaceship. Then, to further complicate his life, he begins to fall in love with Nekalee and has to cope with the possibility that he is a pedophile and never knew it.

Still, he comes to understand that no matter how the adventure has messed up his life, it’s messed up Nekalee’s and Ritee’s a lot more.

Of course, those are all conflicts on the inside. The ones on the outside — like people trying to kill you while you’re hiding from aliens from halfway across the universe who are also trying to kill you — may actually be more urgent problems. And that can be quite a distraction when you are trying to pull off the most daring act of subterfuge ever perpetrated by a college student. On Earth at least.

5) What is the personal goal of the character?

He thinks his goal is to make a name for himself in artificial intelligence, and through that to eventually get enough respect to find a real-live girlfriend, an aspiration that has remained stubbornly elusive. But as the story progresses, he comes to understand that his real goal is to do the right thing. Not only does that trump all his other objectives, it’s a lot harder than the rest of them. Doing what is right is often much more painful than doing what is easy.

6) Is there a working title for this novel, and can we read more about it?

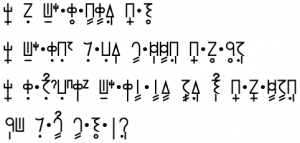

6) Is there a working title for this novel, and can we read more about it?More than a working title; it’s been established for years. The title is A Hierarchy of Gods, a reference that turns up several times in the book and a nod to the fact that there is a lot more in the universe than we little humans have ever imagined. It is the second book in The Saga of Banak-Zuur. And yes, you can see how it all begins. Heck, you can even start learning the aliens’ language.

7) When can we expect the book to be published?

The anticipated date was, for a long time, the end of June, 2014. However, as usual, the vicissitudes of life have introduced delays, so expect it in July or August. Of course, that will push back Nemesis until at least the end of the year, and the third book in The Saga of Banak-Zuur, The White Shamitz, to about the middle of 2015. In the meantime, you can still read the first book in the series, Korvoros.

Where to next?

Fiona Skye

Faery Tales: Urban fantasy with a twist.

web site: http://fiona-skye.com/

Twitter: @FionaSkyeWriter

Amazon: http://www.amazon.com/Fiona-Skye/e/B00CKY01EE/

Lisa Calell

Disconnected/Reconnected: a powerful and painful tale of love and woe.

Twitter: @Lcalel1

Amazon: www.amazon.com/L-Calell/e/B00C9XD35K

The post Blog Tour: Lesley Kellerman appeared first on Duane Vore, Writer.

June 23, 2014

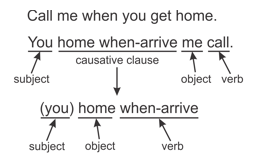

Introduction to Trarsani 4: Tense, Aspect, and Mood

This is the part that I dreaded writing because I wasn’t sure how to approach it. But what it boils down to is that the first step is not mine, but yours. Unlearn everything you know about English. When we use language, we communicate all manner of notions about ownership, causation, time frame, direction, and so forth. English uses prepositions and word order to do that, but there are other systems. There are other systems among human languages, so it follows that there are other systems among non-human languages. Trarsani does not have prepositions in the same sense as we do, and word order doesn’t do nearly the same thing as it does in English.

You probably know that when you translate between languages, you can’t just swap out words. I remember when I was a kid, I think in history or geography class, we learned about the Pennsylvania Dutch. Supposedly, some of them decided to convert to English and did it by swapping Dutch words for English ones, coming up with some wild expressions. Two that I remember are, “Close the gate wide open,” and “Throw your father down the stairs his hat.” English words with Dutch sentence structure makes for some interesting results, and here’s the rub. On the scale of languages, English and Dutch are nearly the same. Try that with English and Mandarin!

So forget about prepositions and word order. Forget about subordinate conjunctions. Forget about gerunds and participles and adverbial phrases. We’ll have to learn a new way of doing things. I’ve split these matters up into six categories: tense, aspect, mood, case, voice, and some miscellanea that don’t sense in English. These all have definitions, but even so, they tend to blur together. Especially tense and aspect, which both have to do with time. When we say in English something like “would have been,” we are combining tense, aspect, and mood. So let’s start taking them back apart, beginning with those three. We’ll begin with the one that is probably most familiar to most of you: tense.

Tense: Particles about when it happens

Tense, as I’m sure you know marks location in time: past, present, or future.

Particle

Roman transcription

Meaning

English example

present tense (default)

say

po-

past tense

said

zo-

future tense

will say

So, said in Trarsani is po-dilai, and will say is zo-dilai. That’s easy enough, right? Wrong. Naturally, it’s a little more complicated than that. These prefix particles can be combined: po-po- means that as of sometime in the past, it was already in the past, similar to had been, and zo-po- means that as of sometime in the future, it was in the past, such as will have been. The English equivalents are not exact, however, as they may contain elements of aspect, suggesting that whatever we are talking about was actually completed as of sometime in the past or future. These Trarsani expressions do not contain that notion.

You might recall from last time that I said Trarsani is more fluid than English. There is nothing to prevent attaching one of these particles to a stative (adjectival) verb: apple po-irai (the apple was red) or even to a noun: po-apple (whatever it is now, it was an apple). Assuming you’re not still one, you are a po-child, a child in the past tense. Actually, we have this in English: ex-girlfriend. But for virtually all of the particles that follow, we don’t.

Aspect: Particles about a relationship with time

Now here is where it starts to get scary (there is an inchoative aspect in that sentence). Aspects also indicate a relationship with time, but instead of where in time, it’s how it relates to time. Whether it is beginning, ending, or completed. Whether it is continuous or progressing. Whether it happens in an instant, continuously, regularly, or over and over.

Aspects are sometimes classified as either perfective (finished) or imperfective (not finished), but we’ll let that distinction slide. The “perfective” in the table below is slightly different. It is easy to identity them in a sentence, because they all rhyme.

Particle

Roman transcription

Meaning

English example

too-

momentane aspect: It happens all at once

It popped!

doo-

inchoative aspect: It is beginning

It’s starting to rain.

zoo-

cessative aspect: It is ending

I’m done fixing supper.

thoo-

sequitive aspect: It happens at the proper time

koo-

durative continuous aspect: It is ongoing

I’m still waiting

poo-

durative progressive aspect: It is ongoing and progressing

It’s coming along fine.

loo-

habitual aspect: It happens regularly (as a habit)

I speak Trarsani

roo-

iterative aspect: It happens over and over

I keep stubbing my toe.

shoo-

perfective aspect: It is complete

I don’t have (as of the time of this writing) an English example of the sequitive aspect, but I hope to come up with one. It might be difficult, however, since I had to invent the term sequitive. There are human cultures (native Americans?) who have this notion in their thinking, but we Europeans aren’t really among them. At one point in A Hierarchy of Gods, Ritee says, “All is as it should be.” She says that with this sequitive aspect in mind, i.e., this is when it was supposed to happen. There is an argument for the sequitive being a tense instead of an aspect, but as I don’t know of any equivalent among human languages, I just made my best guess.

When doo- and zoo- are applied to places and times, they often take a slightly different role, being interpreted as starting-at and stopping-at, respectively. They translate most often as from and to. Fei doo-Cincinnati zoo-Columbus po-zai (I starting-(at)-Cincinnati stopping-(at)-Columbus did-go), or I went from Cincinnati to Columbus. However, there are cases where they might mean the start or end of a time or place. Lent, for example, has a start and end. It is usually apparent from the context, and is one of the few cases where there is some ambiguity in Trarsani. Applying doo- and zoo- to a stative verb indicates that the subject is entering or leaving that state. Apple doo-irai.

Shoo-, the perfective aspect, I think is hard to explain. It’s hard to explain perfectives in English, but grammarians try all the time anyway. It’s sometimes described as viewing the action as a “simple whole.” If it’s a simple whole, it has no fine structure with respect to time, so you can’t say it’s ongoing or talk about its beginning and end. That’s why I described it as “complete.” It differs from too-, the momentane aspect, in that the latter happens at a point in time, and a perfective not necessarily so.

I was going to go over some more examples here, but I suspect that the ones I show in the table are enough for now. Where you really need the examples is after we discuss mood, as they all work together to communicate concepts that we express in other ways. And then there will be more when we throw in case next time. So let’s move on.

Mood: Particles about how the speaker feels about the subject

Grammatical mood is rather hard to define. We learn about the subjunctive mood in school, but that’s only the tip of the iceberg. Mood is everywhere. In general, it expresses the speakers attitude toward what is happening, but then we have to ask exactly what attitude means. Mood expresses ideas of causality, being conditional, subjective vs. objective, potentially, obligation, and more.

Moods are often subdivided into realis (actual, real things) and irrealis (hypothetical, wished for, asked for, etc.) But as with aspect, we’ll not worry about that level of distinction. They don’t all rhyme as the aspects do, but the common ones are simple, short syllables, and many do rhyme.

Are you ready?

Particle

Roman transcription

Meaning

English example

nem-

indicative/demonstrative mood: plain statement of fact.

The oven is hot.

shek-

subjunctive mood: the hypothetical

If I were a rich man…

shef-

causative mood: a condition for something else

If you smash your finger, it will hurt.

nesh-

optative mood: something that is hoped for

I expect that your mother will spank you.

neth-

desiderative mood: something that is desired.

I want to be able to play the piano.

koi-

imperative/precative mood: a request

Can you help me?

tho-

jussive mood: an exhortation

You should help me.

ned-

tentative mood: something there is a little doubt about

I’m sure it will work.

nin-

inferential mood: when something is implied

II hear that she has finished

shee-

interrogative mood: asking a question

Are you coming

nei-

conditional mood: dependent on something else

… then I’ll come with you.

kei-

potential mood (1): the ability for it to happen

I can do this!

dei-

potential mood (2): the possibility for it to happen

I might do this

sei-

obligative mood: indicating necessity

I have to go to work now.

tei-

permissive mood: allowed to do something

You may play on the porch.

yan-

volitive mood: indicating a will to do.

I’m going to kick your butt.

You’re thinking, “Oh, my God! I have to learn all of those?”

The good news is that you already have. You’ve learned them in English, and English is quite a bit harder because instead of being simple, unambiguous, single-syllable particles, they’re built up of varied and seemingly random combinations of auxiliary verbs, adverbs, prepositions and other words. Get used to it and you’ll like it.

The examples above might give you some idea of what they all do, but let’s take a moment to highlight the details.

The Details

nem-

The indicative/demonstrative mood just states a fact, ma’am, and most of the examples I’ve given up until this point are in this mood. Most sentences are. For that reason, you rarely see nem- as sentences (and the words put into them) are demonstrative by default. However, it does sometimes appear as an emphatic to clarify that a statement is true. Apple nem-irai. “The apple is red, and that’s a fact!”

shek- vs. shef-

It is easy to confuse the subjunctive and causative moods in Trarsani, because you probably confuse them in English. It’s even more confusing because we use the causative mood in what we call conditional clauses, and conditional refers to the other end of the sentence, not the cause.

Let’s try to do this. The subjective is something hypothetical. You’re letting your mind wander or just being silly. “If we had a key we could walk out of this jail.” The causative is more real, something that can, and maybe will, happen. Something that something else depends on. It boils down to a spectrum from impossible to the certain.

Subjunctive: If he be dead, I shall be a happy man.

You don’t think he’s dead, and it’s not a very realistic prospect. This is a desire. An “if only”. Notice the use of the subjunctive form be, falling into disfavor in English, but which I wholeheartedly endorse.

Causative: If he is dead, he won’t be able to testify.

You really think the hit man got him, a very real possibility.

A stronger causative: If you take LSD, you will hallucinate.

This is certain!

As we can see, the structure of these sentences is exactly the same, the old if-then structure. That is why they are so easy to confuse. We can go even farther the other direction, and propose a subjunctive that is totally impossible and doesn’t even include the word if: “May the bird of paradise fly up your nose!” Completely hypothetical. It’s never going to happen. This is a hypothetical that has no causative or conditional attached.

Let’s try an example in Trarsani, again using the Roman alphabet for clarity.

“I would eat if I had food.”

“Fei bentee shek-shef-krai nei-brai” (“I food if-if-have conditional-eat.)

The shek-shef- transliterates as if-if- because we use if for both the subjunctive and causative aspects. Here, the speaker is saying that having the food is both hypothetical (apparently he has none, and no prospects) and causative (if he had any it would lead to him eating.) Linguists speculate that shek- and shef- evolved from a common root word and differentiated as people came to want more precision. In casual speech, though, it is unlikely that the speaker would use both of them, and likely just pick one or the other depending on what he wanted to emphasize. the shek-shef- combination is another case of fusion (see last lesson). Keep an eye open for those.

The nei- particle gives us the “then” part of the sentence.

nesh- vs neth-

Nesh- and neth- are two other possibly genetically related particles that can easily be confused, especially by English speakers. We have this annoying habit of using hope to mean wish. Hope originally referred to something that you fully expect to happen, that you are looking forward to. “Oh. Getting married tomorrow? I bet you’re hoping for your wedding night!” That is the meaning of nesh-, an expectation. Neth- is a wish or desire. “Gee, I wish I could find a girlfriend!” Note that I’ll be using hope to mean wish, and if I mean, “hope,” I’ll say, “expect.”

This is a good place to introduce examples of how a particular particle can be applied to various words in a sentence. Consider “I hope Betty comes tomorrow.” Let’s remember that this hope is more along the lines of a wish, so we use neth-. Depending on where we put stress, it can mean, “I hope Betty comes tomorrow,” “I hope Betty comes tomorrow,” “I hope Betty comes tomorrow,” and so on. Let’s do this in Trarsani.

Romanized Trarsani

English equivalent

Betty toi-arthee vandai

Betty is coming tomorrow

neth-Betty toi-arthee vandai

(It is hoped) Betty is coming tomorrow

Betty neth-toi-arthee vandai

(It is hoped) Betty is coming tomorrow

Betty toi-arthee neth-vandai

(It is hoped) Betty is coming tomorrow

You can see that there is a rough equivalence between the particle (neth- in this case) and the emphasis in English. Therefore, you might wonder if it wouldn’t be easier just to use emphasis as we do. It might, but it’s not as good. So let’s get to something really cool about Trarsani that you can’t really do in English.

What would you say about, “nesh-Betty neth-toi-arthee vandai“? The optative mood is applied to Betty and the desiderative mood to tomorrow. This means, essentially, “I’m expecting Betty to come and I’m wishing it’s tomorrow.” That’s a lot to say with three words, along with their associated particles. It is possible in Trarsani to put thoughts together in ways that you haven’t seen before. We can’t use emphasis to shade the meaning, because there would be two kinds of shading.

Now breathe. This is a moment to take a break from cramming facts into your head and instead ponder about what it all means. We’ve taken a little three-word thought, Betty comes tomorrow, and adjusted its meaning quite a bit with two little particles instead of adding three more verbs and building a compound sentence around it. The person who grew up on verb-centered English might ask, “Well, who’s doing the expecting and hoping?” You can see that I made it the speaker in the rough translation in the previous paragraph, and in the table above used the passive voice to avoid saying who. Neither of these is actually right. The Trarsani sentence doesn’t say anything about who is doing the hoping, and it’s not passive.

Now breathe. This is a moment to take a break from cramming facts into your head and instead ponder about what it all means. We’ve taken a little three-word thought, Betty comes tomorrow, and adjusted its meaning quite a bit with two little particles instead of adding three more verbs and building a compound sentence around it. The person who grew up on verb-centered English might ask, “Well, who’s doing the expecting and hoping?” You can see that I made it the speaker in the rough translation in the previous paragraph, and in the table above used the passive voice to avoid saying who. Neither of these is actually right. The Trarsani sentence doesn’t say anything about who is doing the hoping, and it’s not passive.

In fact, I’ve tried variants like “Betty, expectedly, comes hopefully tomorrow,” but that’s not formally correct because expectedly and hopefully, being adverbs, must apply to the verb and so there is no way to be sure which nouns they go with. If we make them adjectives, as in, “Expected Betty comes wishful tomorrow,” we have to realize that tomorrow is not wishful. How about, “Expected Betty comes wished tomorrow?” Now, that’s just weird. I don’t think a literal translation to English is possible. Take this breather to try to get into the groove of Trarsani thinking.

If you’re curious enough to wonder about the difficulties of translation in general, check out dynamic and formal equivalence. Often you can translate the words but doing so misses the meaning, or you can try to translate the meaning, but can’t use matching words to do it. This is why I say from time to time that, ideally, everything should be read in the language in which it was written. (Except Kant, of course!) Unfortunately, I don’t know every language.

However, it is possible to translate, “I’m expecting Betty to come and I’m hoping it’s tomorrow” almost literally into Trarsani. Using English words to highlight the sentence structure. “I Betty at-tomorrow come expect and (u-u-u) I it at-tomorrow hope.” However, no Trarsani would ever say it that way unless delirious.

koi- and tho-

We’ve talked about koi- before. As a particle attached to a verb, it turns it into a request. “Please hold this” or just “Hold this.” becomes “Ka dree koi-finai.” (You this please-hold.) The tho- particles turns it into a stronger request with a subjunctive tone: “Ka dree tho-finai.” (You this really-should-hold.)

The precative and jussive moods bring up some differences in psychology that you should be aware of. We use please to be polite, but the Trarsani have no concept of politeness, except for people like Ritee who study races like humans had have to learn about it. The precative in Trarsani, therefore, has no notion of politeness attached to it; it is simply a marker to distinguish a statement (You are holding this) from a request (Please hold this). Likewise, if calling it an imperative mood, we must bear in mind that there is no concept among the Trarsani of giving orders. In Trarsani, the precative and imperative moods blend into one.

The jussive is different from human experience in the same way. Often, the jussive among humans contains a veiled threat: “You would do well not to offend the king.” The Trarsani have no concept of either offense nor personal threats. Nor is there anything like begging. If the poor guy a few paragraphs up needed food, he wouldn’t even have to ask. All he would have to do is say he was hungry. In Trarsani, the jussive tho- merely suggests that failure to act may have undesirable natural consequences. “You really should take your hand out of the blender.”

This is a good time to point out words like offend, hate, war, and greed don’t translate at all into Trarsani because those concepts don’t even exist. Likewise, I’ve tried to point out how leekee doesn’t translate well as love, but it’s about the closest word we have. Difference in fundamental concepts and world-views can be a big problem in translating between species.

ned- vs nin-

Again, we have two particles that are similar. Both express a degree of uncertainty, suggesting that something is true but not confirmed. ned-, the tentative mood, emphasizes that there is a shadow of a doubt. nin-, the inferential mood, emphasizes that the fact is a conclusion, “inferred,” or reported by a third party. Beginners can probably use them interchangeably without provoking a disaster.

Lets look at some examples.

Romanized Trarsani

English equivalent

Ben lavolai

Ben is sick.

ned-Ben lavolai

Ben is sick, but there’s a chance it’s not Ben.

Ben ned-lavolai

Ben is sick, but there’s a chance he’s not.

nin-Ben lavolai

I understand it is Ben who is sick.

Ben nin-lavolai

Ben is sick, I understand

ned-Ben nin-lavolai

I understand that someone is sick, probably Ben but possibly someone else.

shee-

We touched upon shee- with our discussion of the shee- words last time and the abbreviated sentence structure that goes with them. Sheevo, sheelo, sheezee, and so forth. However, shee can also be used as a particle to add an interrogative.

Romanized Trarsani

English equivalent

shee-Ben lavolai

Is it Ben who is sick?

Ben shee-lavolai

What’s with Ben? Is he sick?

In the first example here, the English uses the reflexive pronoun who to reference back to Ben. Trarsani doesn’t require that sort of construct, as a question can be applied to any part of a sentence. You will only rarely see reflexive pronouns in Trarsani.

Last time, we talked about the Eek- sentence modifier that acts like a question mark. That remains true. But eek questions the verity of an entire statement without regard to any part of it. the shee- particle allows much greater control.

nei-

We mentioned nei- above as the “then” part of a conditional sentence, meaning that the word to which it is attached is conditional on something else. Often, the rest of the sentence will tell you what the conditions are, but not necessarily. You could say, “Fei nei-zo-vandai,” meaning, “I will come, conditionally.” If you can get away from work, if you can afford the ticket, if … whatever. You’re just not specifying. “Call me!” “I (nei) will!”

kei-, dei-, sei-, tei-, and yan-

We wrap up our details with the particles that correspond to English auxiliary verbs, or “helper” verbs as you might have learned them: can, might, must, may, will. Technically, these are modal verbs, as they adjust the mood of another verb.

Since these all work in the same way as the English equivalents, there is not much to say about them other two minor points. There seems some disagreement among human linguists whether to you the term potential to mean ability or possibility, so I’ve used it for both, but on separate lines to make it clear that they are different. The other is that yan- refers to intent. In English we use will for more than one thing, such as your free will (intent) and as a future tense indicator. yan- has nothing to say about tense, just as zo- (future) has nothing to say about mood. Beware of keeping those thoughts separate.

Practice using particles

OK, folks! Now that we have tense, aspect, and mood under our belts, let’s practice putting all of that together. I know you don’t have all of the vocabulary (I have to look things up, myself), but try to figure out how you would put a Trarsani sentence together given the English I’ll hit you with.

“When you stop crying, I will start.”

First of all, let’s take a look at what the sentence is not saying, because there are some misleading words. The word will has nothing to do with either intent or that it takes place sometime in the future. It’s likely in the near future, but it could be right now. The word when is normally used in association with time, but there is no specific time mentioned. So this sentence really says nothing about tense.

Now what does the sentence way? Starting with when, we see that it does refer to time, but what it means is that the time you stop crying is the same time that I start crying. It’s a time relationship, and therefore an aspect. We have the ending of one crying (cessative aspect) correlated with the beginning of another crying (inchoative aspect). The second major factor is the dependency between the two, i.e., that my starting crying is dependent on your stopping. This is a causal-conditional mood relationship.

So now we know that we need the particles doo- and zoo- for the aspect relationship and shef- and nei- for the causal relationship. Putting all this together, remembering the rules for sentence structure:

“Fei ka shef-zoo-nozalai nei-doo-nozalai.”

Or transliterated: “I (you causative-stop-cry) conditional-start-cry.” In cases like this, the final verb can be omitted, leaving only the particles, because we know the sentence has to end with a verb and we can assume that it is the same one as used earlier, just as we do in English. Fei ka shef-zoo-nozalai nei-doo.

“I have been sad ever since Sally died.”