T.S. Rhodes's Blog, page 23

November 18, 2013

How to Make a Pirate Hat.

There are three main kinds of pirate hats – the tricorn hat, like Jack Sparrow’s, the cavalier hat, like Will Turner’s, and the Dutch hat, like Davy Jones. We are going to look at the tricorn and the cavalier hats today.

The first thing you need is a hat. For the tricorn, the go-to pirate hat, you will need a hat with a low, rounded crown (the part your head fits into) and a wide (3 ½ or 4 inches) brim. For the best look, use a wool felt hat in black or brown. You will be able to tell the material of the hat by reading the tag on the inside, along the back of the hat band. If the hat has no tag, but is “fuzzy” and feels like felt, it’s probably what you want.

The first thing you need is a hat. For the tricorn, the go-to pirate hat, you will need a hat with a low, rounded crown (the part your head fits into) and a wide (3 ½ or 4 inches) brim. For the best look, use a wool felt hat in black or brown. You will be able to tell the material of the hat by reading the tag on the inside, along the back of the hat band. If the hat has no tag, but is “fuzzy” and feels like felt, it’s probably what you want.

I got my last pirate hat at a second-hand store for about $2. It needed some work, but no one has ever suspected that it started out as something else. The place to get the ultimate pirate hat blank is here here.The slouch hat works just fine. Of course, this is still $35. You can also use a hat like this this. (I have never used this source, but the type of hat is nearly perfect.)

You will need an object to poke a hole in the hat. An ice pick or a knitting needle is perfect. You will need some material to tie up the sides of the hat. The very best thing you can use is shoelaces – two pairs of black or brown. This stuff is going to show, so you want to think about that when choosing color. You can also use ¼” ribbon.

Materials

Materials

Given these materials, it’s very easy to make the hat. Simply grab the back side of the brim and fold it up, toward the top of the crown. Hold it in place firmly and use the ice pick to punch four holes, like the points of a square, right through the brim and the crown.

Punching holes for lacing

Punching holes for lacing

Cut the shoelaces in half. The aglet on the end of each half makes a perfect tool to poke the shoelace through the tiny holes. Make two vertical stitches to sew up the side of the hat. Just poke the string through two holes and tie it on the inside. Do the same with the other two holes.

Using white lacing here so you can see itRepeat this, putting up the sides so they meet in a point toward the front of the hat. You will find that it’s very natural for the hat brim to go up in three sections.

Using white lacing here so you can see itRepeat this, putting up the sides so they meet in a point toward the front of the hat. You will find that it’s very natural for the hat brim to go up in three sections.

Finished hat with black lacingIs that it? Yes it is.

Finished hat with black lacingIs that it? Yes it is.

Hats from this period are all based on a low, wide-brimmed form. If you start with a very wide-brimmed hat, put up only one side, and add a feather on that side, you have the cavalier hat. If the brim is slightly narrower, and you put up 3 sides, you get the tricorn.

If you cut the tip off the tricorn, you get the Dutch hat. Why would you cut the tip off the tricorn? Well, wear the hat for a while, and bump the tip into a few things, and you’ll see why. If you want this type of hat, first put it up in the tricorn shape, then mark the area you want to cut off with chalk, then take the brim down and cut. This hat works best if you put trim around the edge of the hat brim.

Notes for hatsIf the hat you are working with is too stiff to bend, steam it or wet it with warm water, and work with it while it’s damp. If it is too soft, fabric stores sell a product called fabric stiffener, which you can use as directed to fix it.

If the crown of your hat isn’t the shape you want (my last pirate hat started out with a shape more like a cowboy hat) change the shape by filling the crown of the hat with warm water and letting it sit for a few minutes. Then use your fist to punch the hat into shape. You can also make a too-small hat bigger by wetting it and then forcing it onto your head and wearing it until it’s dry.

If you do this, be careful. Any kind of wetness weakens the fabric of the hat. You can accidently put your hand right through it. I was working with a $2 hat, so I had little to lose.

If you want to put trim around the edge of your hat brim, put it on the underside of a tricorn because that is the side that will show. On a cavalier hat, you must put it on both upper and lower sides of the brim, as both will show. It’s best to sew it on with a sewing machine, using a zig zag stitch, but hot glue will do.

Real tricorn hats were never worn with feathers in them, but you’re a pirate. Feel free to deck your hat out with feathers or gems. One big pin is a popular option, usually put on the left hand side. A huge feather is traditional on a cavalier hat, sweeping out behind. Once again, a big pin is a great accessory.

If you can’t find a felt hat, most fabric stores sell a kind of wide-brimmed straw hat that also makes a fine pirate hat. (If you watch the background of the Pirates of the Caribbean movies, you will see people wearing tricorn straw hats) Just make sure it fits. If you want to paint a straw hat, you can use regular spray paint. A straw hat looks better as a grungy pirate hat.

Pirates aren’t limited to only one kind of hat. Society at the time said that men wore hats. Pirates stole gentlemen’s hats and then wore them until they fell apart, so if your hat has seen better days, so much the better. If it needs to be grunged up a little, grease, spray paint, or actual dirt can be used. Sand paper can simulate wear. And rubber cement can simulate sweat stains on the crown.

Whatever you do, have fun. And if you enjoyed this post, and would like to support pirates and this pirate blog, click the links in the sidebar to buy a copy of Gentlemen and Fortune, the first book of my novel series, The Pirate Empire.

The first thing you need is a hat. For the tricorn, the go-to pirate hat, you will need a hat with a low, rounded crown (the part your head fits into) and a wide (3 ½ or 4 inches) brim. For the best look, use a wool felt hat in black or brown. You will be able to tell the material of the hat by reading the tag on the inside, along the back of the hat band. If the hat has no tag, but is “fuzzy” and feels like felt, it’s probably what you want.

The first thing you need is a hat. For the tricorn, the go-to pirate hat, you will need a hat with a low, rounded crown (the part your head fits into) and a wide (3 ½ or 4 inches) brim. For the best look, use a wool felt hat in black or brown. You will be able to tell the material of the hat by reading the tag on the inside, along the back of the hat band. If the hat has no tag, but is “fuzzy” and feels like felt, it’s probably what you want.

I got my last pirate hat at a second-hand store for about $2. It needed some work, but no one has ever suspected that it started out as something else. The place to get the ultimate pirate hat blank is here here.The slouch hat works just fine. Of course, this is still $35. You can also use a hat like this this. (I have never used this source, but the type of hat is nearly perfect.)

You will need an object to poke a hole in the hat. An ice pick or a knitting needle is perfect. You will need some material to tie up the sides of the hat. The very best thing you can use is shoelaces – two pairs of black or brown. This stuff is going to show, so you want to think about that when choosing color. You can also use ¼” ribbon.

Materials

MaterialsGiven these materials, it’s very easy to make the hat. Simply grab the back side of the brim and fold it up, toward the top of the crown. Hold it in place firmly and use the ice pick to punch four holes, like the points of a square, right through the brim and the crown.

Punching holes for lacing

Punching holes for lacingCut the shoelaces in half. The aglet on the end of each half makes a perfect tool to poke the shoelace through the tiny holes. Make two vertical stitches to sew up the side of the hat. Just poke the string through two holes and tie it on the inside. Do the same with the other two holes.

Using white lacing here so you can see itRepeat this, putting up the sides so they meet in a point toward the front of the hat. You will find that it’s very natural for the hat brim to go up in three sections.

Using white lacing here so you can see itRepeat this, putting up the sides so they meet in a point toward the front of the hat. You will find that it’s very natural for the hat brim to go up in three sections.  Finished hat with black lacingIs that it? Yes it is.

Finished hat with black lacingIs that it? Yes it is.Hats from this period are all based on a low, wide-brimmed form. If you start with a very wide-brimmed hat, put up only one side, and add a feather on that side, you have the cavalier hat. If the brim is slightly narrower, and you put up 3 sides, you get the tricorn.

If you cut the tip off the tricorn, you get the Dutch hat. Why would you cut the tip off the tricorn? Well, wear the hat for a while, and bump the tip into a few things, and you’ll see why. If you want this type of hat, first put it up in the tricorn shape, then mark the area you want to cut off with chalk, then take the brim down and cut. This hat works best if you put trim around the edge of the hat brim.

Notes for hatsIf the hat you are working with is too stiff to bend, steam it or wet it with warm water, and work with it while it’s damp. If it is too soft, fabric stores sell a product called fabric stiffener, which you can use as directed to fix it.

If the crown of your hat isn’t the shape you want (my last pirate hat started out with a shape more like a cowboy hat) change the shape by filling the crown of the hat with warm water and letting it sit for a few minutes. Then use your fist to punch the hat into shape. You can also make a too-small hat bigger by wetting it and then forcing it onto your head and wearing it until it’s dry.

If you do this, be careful. Any kind of wetness weakens the fabric of the hat. You can accidently put your hand right through it. I was working with a $2 hat, so I had little to lose.

If you want to put trim around the edge of your hat brim, put it on the underside of a tricorn because that is the side that will show. On a cavalier hat, you must put it on both upper and lower sides of the brim, as both will show. It’s best to sew it on with a sewing machine, using a zig zag stitch, but hot glue will do.

Real tricorn hats were never worn with feathers in them, but you’re a pirate. Feel free to deck your hat out with feathers or gems. One big pin is a popular option, usually put on the left hand side. A huge feather is traditional on a cavalier hat, sweeping out behind. Once again, a big pin is a great accessory.

If you can’t find a felt hat, most fabric stores sell a kind of wide-brimmed straw hat that also makes a fine pirate hat. (If you watch the background of the Pirates of the Caribbean movies, you will see people wearing tricorn straw hats) Just make sure it fits. If you want to paint a straw hat, you can use regular spray paint. A straw hat looks better as a grungy pirate hat.

Pirates aren’t limited to only one kind of hat. Society at the time said that men wore hats. Pirates stole gentlemen’s hats and then wore them until they fell apart, so if your hat has seen better days, so much the better. If it needs to be grunged up a little, grease, spray paint, or actual dirt can be used. Sand paper can simulate wear. And rubber cement can simulate sweat stains on the crown.

Whatever you do, have fun. And if you enjoyed this post, and would like to support pirates and this pirate blog, click the links in the sidebar to buy a copy of Gentlemen and Fortune, the first book of my novel series, The Pirate Empire.

Published on November 18, 2013 17:36

November 11, 2013

Pirate Food

We’re a jolly good ship and a jolly good crew,But we don’t like the food, no I’m damned if we do.(sea shanty)

It’s common knowledge that food at sea was terrible. The meat was rotten, the bread was full of bugs, and sailors often died from scurvy, a horrible disease which caused sores, rotting teeth and eventual death. But common knowledge isn’t always right. Members of a pirate crew often ate the best food they had ever experienced. The lure of fine food was a strong recruitment tool for pirates.

True, preserving food for long journeys was not an easy thing to do in the 18th century. Salt was the preservative of choice. But one need only look at the McDonald’s hamburger that’s remained unchanged for over a decade to see that salt can make an excellent preservative.

Cooking facilities at sea were primitive at best. Often a ship had nothing more than a metal box full of sand, in which the cook could light a fire and heat preserved food. In rough weather, the fire needed to be put out, and men ate raw, salted beef.

A more sophisticated arrangement was to hang an iron stove from the beams above on chains. This allowed the cooking surface to remain level in rougher seas and provided greater protection from fire. But it also took up a lot of space, because the hot stove must not touch the walls, even when the boat was pitching wildly. Only large vessels could manage such luxuries.

The floor of the galley (ship’s kitchen) was often lined with sheets of tin, to prevent hot coals from setting the ship on fire. Also, the galley was usually located toward the rear of the ship, generally a more stable area. Still, the galley was not large, and equipment was usually only a few pots, wooden or iron ladles and spoons, and a few wooden trays. It’s no surprise that ship’s food was often simple and monotonous.

Beef was stored on ships in barrels. The type of bread used, a hard wheat biscuit of about the size and shape of a Pecan Sandy, was always made on shore. It was especially formulated and double-baked (like a biscotti) to keep it fresh as long as possible. Bags full of it were kept in storage. Sailors also ate reconstituted dried peas (think split-pea soup) which provided good nutrition and some vitamin C.

But merchant ship owners were highly motivated to reduce costs. These men often did not sail their own ships, and so had no incentive to provide anything but the cheapest food. Captains often earned a commission based on how much profit the ship made, so feeding the crew cheap, poorly preserved food increased a captain’s pay. It was a simple matter to keep one supply of food for the crew and a different one for the officers. Often the captain kept live chickens for fresh eggs, live goats or a cow for milk or meat, live pigs for ham. The sailors never enjoyed such luxury.

Merchant sailors had no unions, and no regulations existed for safe working conditions or decent food, so anything might end up on a sailor’s plate. Jokes about horse meat were common. The early days of The Golden Age of Piracy coincided with the rise of Capitalism, and pirates were often directly protesting the emphasis on ‘profit above all’ that led to sailor deaths.

Item 1 “Every man has a vote in affairs of moment; has equal title to the fresh provisions, or strong liquors, at any time seized, and may use them at pleasure, unless a scarcity makes necessary, for the good of all, to vote a retrenchment.”

This is a direct quote from Bartholomew Robert’s pirate articles (regulations) a set of rules signed by every man who became a pirate. Often the “pirate articles” were the only law pirates recognized. And first on the list was that everybody ate the same food and drank the same liquor. And everyone could eat (and drink) as much as he liked.

Sailors often came from the lowest ranks of society, often the children of farmers who had been chased off their land by the greedy landlords, or members of London’s urban poor. For people like this “Enough to eat” was a concept they had never experienced.

Pirates bragged about the fine food they ate as part of their recruitment efforts. “All the fresh food you want, all the liquor you want,” was repeated over and over. For men starved for a healthy diet, this must have been high incentive indeed. Often whole crews deserted and joined the pirates.

On merchant ships, sailors often didn’t even get their meals on plates. A “mess” or mealtime group was simple given some bread and a bucket of boiled beef, which they were expected to share. On better boats, men were able to use plates. Plates made of use at sea were usually made of wood or pewter, and were often square.

When I visited the Bounty(May she rest in peace) I saw how tables folded out of the sides of the ship in the crew quarters. The sailors sat on whatever was available, and wrapped their forearms around their plates, to keep them from sliding away from the ship’s motion. Since only ships which provided better accommodations also provided plates, this may be the origin of the term “square meal.” Sailors were always identified by the way they clutched their plates, even on land. It was a habit that was hard to break, since if you lost your food, you didn’t get more.

Pirates stole food and liquor, not just treasure, so pirates re-supplied whenever they robbed a ship. If the captain was keeping fine whiskey and good cheese for himself, they took it. If there were animals, they took those and ate them (If a cow gives a gallon of milk a day, that’s plenty for five officers, but it doesn’t go very far for 100 pirates. Better to put the animal into a stew, which everyone can share.)

When there were a variety of liquors, pirates called upon the cook to make “punch.” Any liquor available was emptied into a large bowl or barrel, and it was flavored with fruit juice and spice. Don’t think for a minute that this equates to today’s “spiked” punch. The pirates were aiming for the greatest “kick” possible, and the concoction was almost 100% hard liquor. Putting it all into one mixture was a simple way to make sure that everybody had equal access.

Pirates also stole cargos of spices, cinnamon, peppers, nutmeg, cloves, allspice and ginger, which were very expensive.. Even middle class people couldn’t always afford such luxuries. Many commentators mentioned that the pirates loved highly spiced food.

Salmagundi, an English dish made of the widest possible combination of cold, cooked seafood, meat, nuts, flowers, leaves and vegetables, flavored with oil, vinegar and spices was perfect for the pirate diet. This dish had no specific format, but incorporated any available ingredients. One recipe goes as follows:

"Cut cold roast chicken or other meats into slices. Mix with minced tarragon and an onion. Mix all together with capers, olives, samphire, broombuds, mushrooms, oysters, lemon, orange, raisins, almonds, blue figs, Virginia potatoes, peas and red and white currants. Garnish with sliced oranges and lemons. Cover with oil and vinegar, beaten together." (from The Good Huswives Treasure, Robert May, 1588–1660)

The origins of this dish is not clear, but the name may be derived from a French word meaning “odds and ends.” In the Caribbean, the name was further corrupted into “Solomon Grundy” and used to describe a hot stew with an equally wide variety of ingredients. Each pirate cook had his own recipe, and pirate crews occasionally held cook-offs to see whose stew was the best.

Pirates, unlike merchants and navy sailors, kept good relationships with native populations. The natives were happy to meet any Europeans who didn’t want to enslave them or convert them to Christianity. Pirates saw the natives as oppressed minorities, much like themselves. The two groups often met to trade guns, gunpowder and European manufactured goods for preserved or fresh meat and produce. Local suppliers meant better food.

What a pleasure this must have been for the pirate cooks! To go from a job where raw materials for your craft were terrible, and you usde them to make a product that everyone complained about, and move up to a craft with a wide variety of fresh ingredients where you could use your imagination and skills to made food that not only pleased the diners, but inspired them to brag about you!

It’s common knowledge that food at sea was terrible. The meat was rotten, the bread was full of bugs, and sailors often died from scurvy, a horrible disease which caused sores, rotting teeth and eventual death. But common knowledge isn’t always right. Members of a pirate crew often ate the best food they had ever experienced. The lure of fine food was a strong recruitment tool for pirates.

True, preserving food for long journeys was not an easy thing to do in the 18th century. Salt was the preservative of choice. But one need only look at the McDonald’s hamburger that’s remained unchanged for over a decade to see that salt can make an excellent preservative.

Cooking facilities at sea were primitive at best. Often a ship had nothing more than a metal box full of sand, in which the cook could light a fire and heat preserved food. In rough weather, the fire needed to be put out, and men ate raw, salted beef.

A more sophisticated arrangement was to hang an iron stove from the beams above on chains. This allowed the cooking surface to remain level in rougher seas and provided greater protection from fire. But it also took up a lot of space, because the hot stove must not touch the walls, even when the boat was pitching wildly. Only large vessels could manage such luxuries.

The floor of the galley (ship’s kitchen) was often lined with sheets of tin, to prevent hot coals from setting the ship on fire. Also, the galley was usually located toward the rear of the ship, generally a more stable area. Still, the galley was not large, and equipment was usually only a few pots, wooden or iron ladles and spoons, and a few wooden trays. It’s no surprise that ship’s food was often simple and monotonous.

Beef was stored on ships in barrels. The type of bread used, a hard wheat biscuit of about the size and shape of a Pecan Sandy, was always made on shore. It was especially formulated and double-baked (like a biscotti) to keep it fresh as long as possible. Bags full of it were kept in storage. Sailors also ate reconstituted dried peas (think split-pea soup) which provided good nutrition and some vitamin C.

But merchant ship owners were highly motivated to reduce costs. These men often did not sail their own ships, and so had no incentive to provide anything but the cheapest food. Captains often earned a commission based on how much profit the ship made, so feeding the crew cheap, poorly preserved food increased a captain’s pay. It was a simple matter to keep one supply of food for the crew and a different one for the officers. Often the captain kept live chickens for fresh eggs, live goats or a cow for milk or meat, live pigs for ham. The sailors never enjoyed such luxury.

Merchant sailors had no unions, and no regulations existed for safe working conditions or decent food, so anything might end up on a sailor’s plate. Jokes about horse meat were common. The early days of The Golden Age of Piracy coincided with the rise of Capitalism, and pirates were often directly protesting the emphasis on ‘profit above all’ that led to sailor deaths.

Item 1 “Every man has a vote in affairs of moment; has equal title to the fresh provisions, or strong liquors, at any time seized, and may use them at pleasure, unless a scarcity makes necessary, for the good of all, to vote a retrenchment.”

This is a direct quote from Bartholomew Robert’s pirate articles (regulations) a set of rules signed by every man who became a pirate. Often the “pirate articles” were the only law pirates recognized. And first on the list was that everybody ate the same food and drank the same liquor. And everyone could eat (and drink) as much as he liked.

Sailors often came from the lowest ranks of society, often the children of farmers who had been chased off their land by the greedy landlords, or members of London’s urban poor. For people like this “Enough to eat” was a concept they had never experienced.

Pirates bragged about the fine food they ate as part of their recruitment efforts. “All the fresh food you want, all the liquor you want,” was repeated over and over. For men starved for a healthy diet, this must have been high incentive indeed. Often whole crews deserted and joined the pirates.

On merchant ships, sailors often didn’t even get their meals on plates. A “mess” or mealtime group was simple given some bread and a bucket of boiled beef, which they were expected to share. On better boats, men were able to use plates. Plates made of use at sea were usually made of wood or pewter, and were often square.

When I visited the Bounty(May she rest in peace) I saw how tables folded out of the sides of the ship in the crew quarters. The sailors sat on whatever was available, and wrapped their forearms around their plates, to keep them from sliding away from the ship’s motion. Since only ships which provided better accommodations also provided plates, this may be the origin of the term “square meal.” Sailors were always identified by the way they clutched their plates, even on land. It was a habit that was hard to break, since if you lost your food, you didn’t get more.

Pirates stole food and liquor, not just treasure, so pirates re-supplied whenever they robbed a ship. If the captain was keeping fine whiskey and good cheese for himself, they took it. If there were animals, they took those and ate them (If a cow gives a gallon of milk a day, that’s plenty for five officers, but it doesn’t go very far for 100 pirates. Better to put the animal into a stew, which everyone can share.)

When there were a variety of liquors, pirates called upon the cook to make “punch.” Any liquor available was emptied into a large bowl or barrel, and it was flavored with fruit juice and spice. Don’t think for a minute that this equates to today’s “spiked” punch. The pirates were aiming for the greatest “kick” possible, and the concoction was almost 100% hard liquor. Putting it all into one mixture was a simple way to make sure that everybody had equal access.

Pirates also stole cargos of spices, cinnamon, peppers, nutmeg, cloves, allspice and ginger, which were very expensive.. Even middle class people couldn’t always afford such luxuries. Many commentators mentioned that the pirates loved highly spiced food.

Salmagundi, an English dish made of the widest possible combination of cold, cooked seafood, meat, nuts, flowers, leaves and vegetables, flavored with oil, vinegar and spices was perfect for the pirate diet. This dish had no specific format, but incorporated any available ingredients. One recipe goes as follows:

"Cut cold roast chicken or other meats into slices. Mix with minced tarragon and an onion. Mix all together with capers, olives, samphire, broombuds, mushrooms, oysters, lemon, orange, raisins, almonds, blue figs, Virginia potatoes, peas and red and white currants. Garnish with sliced oranges and lemons. Cover with oil and vinegar, beaten together." (from The Good Huswives Treasure, Robert May, 1588–1660)

The origins of this dish is not clear, but the name may be derived from a French word meaning “odds and ends.” In the Caribbean, the name was further corrupted into “Solomon Grundy” and used to describe a hot stew with an equally wide variety of ingredients. Each pirate cook had his own recipe, and pirate crews occasionally held cook-offs to see whose stew was the best.

Pirates, unlike merchants and navy sailors, kept good relationships with native populations. The natives were happy to meet any Europeans who didn’t want to enslave them or convert them to Christianity. Pirates saw the natives as oppressed minorities, much like themselves. The two groups often met to trade guns, gunpowder and European manufactured goods for preserved or fresh meat and produce. Local suppliers meant better food.

What a pleasure this must have been for the pirate cooks! To go from a job where raw materials for your craft were terrible, and you usde them to make a product that everyone complained about, and move up to a craft with a wide variety of fresh ingredients where you could use your imagination and skills to made food that not only pleased the diners, but inspired them to brag about you!

Published on November 11, 2013 13:49

November 4, 2013

A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pyrates

and Also Their Policies, Discipline and Government, From Their First Rise and Settlement in the Island of Providence By Captain Charles Johnson

In 1724 the publisher Charles Rivington of London brought forth a book which would profoundly influence the popular notion of pirates. It is still in print almost 300 years later. Much about the book remains shrouded in mystery. Indeed, we are not even sure who wrote it.

click for pictures

click for pictures

And yet it remains THE book, the original volume that shaped the word’s notion of pirates. Dozens of versions are available today. You can have hardback, paperback, facsimile edition, or you can browse the Google edition or upload it to your Nook or Kindle. East Carolina University offers a page-through digital copy of a first edition.

The story of the book probably begins about ten years before it was actually written. In 1712, British author Charles Johnson had an play produced at Drury Lane titled The Successful Pyrate. It celebrated the story of an outlaw, Henry Avery, and people of the time were shocked. Though modern folk are very familiar with anti-heroes and the glamorization of criminals, in the eighteenth century the notion of making a pirate the central character of a play was outrageous.

Though the original play was not successful, the amount of talk and scandal surrounding it encouraged others to write and produce work celebrating the lives of pirates, highwaymen, and even notorious prostitutes.

The General History of Pyrates (as it is commonly known) seems clearly to be a response to this fad, and the pseudonym chosen by the author, Captain Charles Johnson, seems to link directly to the original failed play.

Captain Johnson was clearly not a real person. He existed only as the author of the book. Scholars have wondered about the real identity of the author for many years. It became popular to assume that Daniel Defoe, author of Treasure Island, had written the book. Indeed, many current editions carry his name. Defoe, like the author of The General History, was very familiar with ships and sailing, the time periods were correct, and it seemed logical to assign the work to a known author.

But other people were not so happy with this. Why, for instance, should Defoe choose a pseudonym for this book alone? Arne Bialuschewski of the University of Kiel in Germany has recently suggested Nathaniel Mist, a former sailor, journalist, and publisher of the Weekly Journal, as a more likely candidate. Charles Rivington (publisher of the History), had printed books for Mist, who lived near his office. Further, the General History was registered at Her Majesty's Stationery Office in Mist's name. As a former seaman who had sailed the West Indies, Mist, of all London's writer-publishers, was uniquely qualified to have penned the History.

I enjoyed reading the book, but it must be taken in context. The General History is a work of its time. It is chatty and wandering, occasionally speaking directly to the reader in a your-not-going-to-believe-this tone. At one point it wanders away to suggest a get-rich-quick scheme for English captains who may want to smuggle slaves into Brazil.

Printed in two volumes, the book is divided into chapters giving autobiographies of various pirates, and has been credited with making characters such as Blackbeard, Calico Jack Rackham and Bartholomew Roberts into legends.

Love of the subject matter shines through on every line. The author may say, repeatedly, how reprehensible pirates were, recite the damage they did, and call for their eradication. But he also recited in loving detail all the gossip about pirates.

Among its tales of famous and successful pirates, the book contains the story of a pirate ship which ran aground near the coast of South America. While waiting for the rising tides of the season to lift them off, the pirates found themselves running short on provisions, and sent a party off in their only longboat to obtain supplies. Only after the boat had rowed away did the pirates realize that without it they had no way to get to shore and get water. The entire crew nearly died before their comrades returned. Tales like this don’t make it to modern story books.

Another section recounts a series of increasingly threatening letters between an English privateer and a Spanish town. The English demand surrender and threaten to attack and burn the city. The Spanish brag that they can hold out forever, and threaten to torture every attacker that they capture. What makes the exchange hilarious to the modern eye is that the English captain signs each of his letters “Your humble and obedient servant” and the Spaniard signs his “I kiss your hand.” Plainly, these were typical closures of the time, as innocuous to the writers as “Yours truly” is to us. 300 years later, the effect is quite different.

For many people the books were fact. After all, whoever “Johnson” was, he lived during the Golden Age of Piracy, and had access to real pirates, and the friends of real pirates, when he wrote his book. But many of the stories have been proven false. The reasons are probably as follows: Human memory only goes so far. To a pirate, a good story is far more important than the truth. And when you’re buying a man drinks so he’ll recite stories of his youth as a pirate, he’s likely to keep talking as long as the rum holds out.

For this reason, The General History tells of how Anne Bonny, sailing with her lover, Calico Jack Rackham, took interest in a handsome young man on a ship they had captured. According to The History, Anne was alone with the fellow when Jack stormed in, shouting in jealous rage. It was at that point that Mary Reed revealed her true gender, and agreed to join Jack and Anne.

Historical documents say that Anne and Mary became friends on the island of Nassau, long before Anne went to sea. But the former story is more compelling, so that’s the one that was written down. Editions of The General History were usually heavily advertised as containing the stories of the two cross-dressing women. Dutch editions of the book went so far as to commission a racy new picture of the two women, their shirts open to reveal their breasts. It also moved this illustration right up front near the title page. With this change, Dutch editions flew off the shelves.

Though not completely accurate, The General History set the stage for pirate tales, and has been the inspiration for authors from JM Barrie and Robert Lewis Stevenson to the creators of Pirates of the Caribbean.

Books have always been an important way for pirate lovers to celebrate their passion for the freedom of the open sea. If you enjoy this blog, and would like to support it while getting your own ‘pirate fix’, please click this link to enjoy the adventures of my own fictional pirate captain, Scarlet MacGrath, in The Pirate Empire series.

In 1724 the publisher Charles Rivington of London brought forth a book which would profoundly influence the popular notion of pirates. It is still in print almost 300 years later. Much about the book remains shrouded in mystery. Indeed, we are not even sure who wrote it.

click for pictures

click for picturesAnd yet it remains THE book, the original volume that shaped the word’s notion of pirates. Dozens of versions are available today. You can have hardback, paperback, facsimile edition, or you can browse the Google edition or upload it to your Nook or Kindle. East Carolina University offers a page-through digital copy of a first edition.

The story of the book probably begins about ten years before it was actually written. In 1712, British author Charles Johnson had an play produced at Drury Lane titled The Successful Pyrate. It celebrated the story of an outlaw, Henry Avery, and people of the time were shocked. Though modern folk are very familiar with anti-heroes and the glamorization of criminals, in the eighteenth century the notion of making a pirate the central character of a play was outrageous.

Though the original play was not successful, the amount of talk and scandal surrounding it encouraged others to write and produce work celebrating the lives of pirates, highwaymen, and even notorious prostitutes.

The General History of Pyrates (as it is commonly known) seems clearly to be a response to this fad, and the pseudonym chosen by the author, Captain Charles Johnson, seems to link directly to the original failed play.

Captain Johnson was clearly not a real person. He existed only as the author of the book. Scholars have wondered about the real identity of the author for many years. It became popular to assume that Daniel Defoe, author of Treasure Island, had written the book. Indeed, many current editions carry his name. Defoe, like the author of The General History, was very familiar with ships and sailing, the time periods were correct, and it seemed logical to assign the work to a known author.

But other people were not so happy with this. Why, for instance, should Defoe choose a pseudonym for this book alone? Arne Bialuschewski of the University of Kiel in Germany has recently suggested Nathaniel Mist, a former sailor, journalist, and publisher of the Weekly Journal, as a more likely candidate. Charles Rivington (publisher of the History), had printed books for Mist, who lived near his office. Further, the General History was registered at Her Majesty's Stationery Office in Mist's name. As a former seaman who had sailed the West Indies, Mist, of all London's writer-publishers, was uniquely qualified to have penned the History.

I enjoyed reading the book, but it must be taken in context. The General History is a work of its time. It is chatty and wandering, occasionally speaking directly to the reader in a your-not-going-to-believe-this tone. At one point it wanders away to suggest a get-rich-quick scheme for English captains who may want to smuggle slaves into Brazil.

Printed in two volumes, the book is divided into chapters giving autobiographies of various pirates, and has been credited with making characters such as Blackbeard, Calico Jack Rackham and Bartholomew Roberts into legends.

Love of the subject matter shines through on every line. The author may say, repeatedly, how reprehensible pirates were, recite the damage they did, and call for their eradication. But he also recited in loving detail all the gossip about pirates.

Among its tales of famous and successful pirates, the book contains the story of a pirate ship which ran aground near the coast of South America. While waiting for the rising tides of the season to lift them off, the pirates found themselves running short on provisions, and sent a party off in their only longboat to obtain supplies. Only after the boat had rowed away did the pirates realize that without it they had no way to get to shore and get water. The entire crew nearly died before their comrades returned. Tales like this don’t make it to modern story books.

Another section recounts a series of increasingly threatening letters between an English privateer and a Spanish town. The English demand surrender and threaten to attack and burn the city. The Spanish brag that they can hold out forever, and threaten to torture every attacker that they capture. What makes the exchange hilarious to the modern eye is that the English captain signs each of his letters “Your humble and obedient servant” and the Spaniard signs his “I kiss your hand.” Plainly, these were typical closures of the time, as innocuous to the writers as “Yours truly” is to us. 300 years later, the effect is quite different.

For many people the books were fact. After all, whoever “Johnson” was, he lived during the Golden Age of Piracy, and had access to real pirates, and the friends of real pirates, when he wrote his book. But many of the stories have been proven false. The reasons are probably as follows: Human memory only goes so far. To a pirate, a good story is far more important than the truth. And when you’re buying a man drinks so he’ll recite stories of his youth as a pirate, he’s likely to keep talking as long as the rum holds out.

For this reason, The General History tells of how Anne Bonny, sailing with her lover, Calico Jack Rackham, took interest in a handsome young man on a ship they had captured. According to The History, Anne was alone with the fellow when Jack stormed in, shouting in jealous rage. It was at that point that Mary Reed revealed her true gender, and agreed to join Jack and Anne.

Historical documents say that Anne and Mary became friends on the island of Nassau, long before Anne went to sea. But the former story is more compelling, so that’s the one that was written down. Editions of The General History were usually heavily advertised as containing the stories of the two cross-dressing women. Dutch editions of the book went so far as to commission a racy new picture of the two women, their shirts open to reveal their breasts. It also moved this illustration right up front near the title page. With this change, Dutch editions flew off the shelves.

Though not completely accurate, The General History set the stage for pirate tales, and has been the inspiration for authors from JM Barrie and Robert Lewis Stevenson to the creators of Pirates of the Caribbean.

Books have always been an important way for pirate lovers to celebrate their passion for the freedom of the open sea. If you enjoy this blog, and would like to support it while getting your own ‘pirate fix’, please click this link to enjoy the adventures of my own fictional pirate captain, Scarlet MacGrath, in The Pirate Empire series.

Published on November 04, 2013 13:05

October 28, 2013

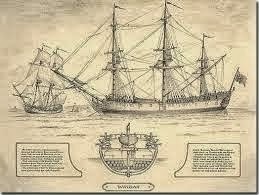

The Wreck of the Whydah

As Sam Bellamy and his newly captured flagship, the Whydah headed north toward Cape Cod, a successful pirating season seemed assured.

Bellamy, his ship laden with cannons and small arms stolen from previously captured vessels, continued to collect prizes along the way. He captured and held the Anne, the Mary Anne, and the Fisher, smaller vessels that that tagged after Bellamy and the 300 ton, 28 gun Whydah. The huge pirate vessel housed 130 pirates and 16 captives, captains and officers of the captive ships.

Bellamy may have been planning a revolution. Or he may simply have been heading north to see his old flame, Mary Hallett. For whatever reason, he was off the coast of Cape Cod on April 26, 1717, when one of the worst storms ever recorded hit the Atlantic Coast.

A Nor’easter from Canada met a warm front moving up from the Caribbean, and the resulting waves ran the Whydah hard aground on a sandbar, snapped her masts like twigs, and swamped her boats. Finally, the raging seas picked up the enormous ship and rolled her upside down. Though the beach was only 500 feet away, the frigid, turbulent waters were a death trap. Only two of the pirates aboard the Whydah made it to shore alive. Bellamy was not one of them. The two survivors, kidnapped carpenter Thomas Davis and Native American navigator John Julian were quickly arrested.

The much smaller consort ships had fared better. The Fisher was damaged badly enough that she had to be abandoned, but her small crew of 5 pirates survived and transferred to the Anne. They joined the 19 crew aboard that ship and sailed away, hoping to find Sam’s friend Paulsgrave Williams and the Maryanne, which had missed the storm.

The Mary Anne survived the storm, but lost all of her masts and rigging. The sailors aboard, several who were visiting the ship from the Whydah, were devastated to learn of the loss of the larger ship and most of their friends and companions. They were also afraid of being caught themselves. Abandoning their crippled vessel, they headed off on foot.

They might have gotten away, had they not stopped at a tavern to toast their fallen comrades. They were arrested by sheriff’s deputies and hauled off to Boston for trial, along with their two comrades.

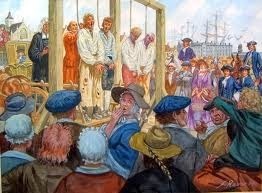

It would be 7 months before these men, still wearing the clothes in which they weathered the storm, were tried for piracy in Boston. During that time the fire and brimstone minister, Cotton Mather, visited them in prison and recorded their stories. When they faced the judge, three men escaped the death penalty for robbery and piracy.

Thomas Davis successfully convinced the judge that he had been pressed into service by pirates who needed his carpentry skills. John Julian, the Native American was sold as a slave. The rest, Thomas South, Peter Cornelius Hoof, John Shaun, John Brown, Thomas Baker, Simon Van Vorst, and Hendrick Quintor, a free black man who had signed aboard Bellamy’s ship, were sentenced to be hanged.

The sentence was carried out in Charleston on November 15th. Cotton Mather, who accompanied the men to their hanging, published a pamphlet about their lives called “The End of Piracy,” though piracy certainly did not end with Sam Bellamy.

John Julian was sold to John Quincy, grandfather of President John Quincy Adams, who became a staunch abolitionist. “Indian John” as he was called, never made a good slave. He was unruly, and tried multiple times to escape. He was finally killed in an escape attempt in 1733.

The remaining free members of the Whydah’s crew sailed north until they met up with Paulsgrave Williams. They joined his crew and headed back to the Caribbean.

All of the pirates had spoken of the great treasure contained in the Whydah’s hold, but efforts to reach it turned out to be futile. Thirty feet of water was simply too much for the technology of the time to overcome. So the treasure remained on the ocean bottom. Cotton Mather’s pamphlets and notes were put away. Knowledge of Sam Bellamy and his magnificent ship the Whydah faded into local legend. It was said, in the area around Cape Cod, that a local girl, Mary or Maria Hallett, had been betrothed to a man who became a pirate.

Until Barry Clifford, researching this legend, found some notes, an old pamphlet and a map in the back storage of his local library…

Bellamy, his ship laden with cannons and small arms stolen from previously captured vessels, continued to collect prizes along the way. He captured and held the Anne, the Mary Anne, and the Fisher, smaller vessels that that tagged after Bellamy and the 300 ton, 28 gun Whydah. The huge pirate vessel housed 130 pirates and 16 captives, captains and officers of the captive ships.

Bellamy may have been planning a revolution. Or he may simply have been heading north to see his old flame, Mary Hallett. For whatever reason, he was off the coast of Cape Cod on April 26, 1717, when one of the worst storms ever recorded hit the Atlantic Coast.

A Nor’easter from Canada met a warm front moving up from the Caribbean, and the resulting waves ran the Whydah hard aground on a sandbar, snapped her masts like twigs, and swamped her boats. Finally, the raging seas picked up the enormous ship and rolled her upside down. Though the beach was only 500 feet away, the frigid, turbulent waters were a death trap. Only two of the pirates aboard the Whydah made it to shore alive. Bellamy was not one of them. The two survivors, kidnapped carpenter Thomas Davis and Native American navigator John Julian were quickly arrested.

The much smaller consort ships had fared better. The Fisher was damaged badly enough that she had to be abandoned, but her small crew of 5 pirates survived and transferred to the Anne. They joined the 19 crew aboard that ship and sailed away, hoping to find Sam’s friend Paulsgrave Williams and the Maryanne, which had missed the storm.

The Mary Anne survived the storm, but lost all of her masts and rigging. The sailors aboard, several who were visiting the ship from the Whydah, were devastated to learn of the loss of the larger ship and most of their friends and companions. They were also afraid of being caught themselves. Abandoning their crippled vessel, they headed off on foot.

They might have gotten away, had they not stopped at a tavern to toast their fallen comrades. They were arrested by sheriff’s deputies and hauled off to Boston for trial, along with their two comrades.

It would be 7 months before these men, still wearing the clothes in which they weathered the storm, were tried for piracy in Boston. During that time the fire and brimstone minister, Cotton Mather, visited them in prison and recorded their stories. When they faced the judge, three men escaped the death penalty for robbery and piracy.

Thomas Davis successfully convinced the judge that he had been pressed into service by pirates who needed his carpentry skills. John Julian, the Native American was sold as a slave. The rest, Thomas South, Peter Cornelius Hoof, John Shaun, John Brown, Thomas Baker, Simon Van Vorst, and Hendrick Quintor, a free black man who had signed aboard Bellamy’s ship, were sentenced to be hanged.

The sentence was carried out in Charleston on November 15th. Cotton Mather, who accompanied the men to their hanging, published a pamphlet about their lives called “The End of Piracy,” though piracy certainly did not end with Sam Bellamy.

John Julian was sold to John Quincy, grandfather of President John Quincy Adams, who became a staunch abolitionist. “Indian John” as he was called, never made a good slave. He was unruly, and tried multiple times to escape. He was finally killed in an escape attempt in 1733.

The remaining free members of the Whydah’s crew sailed north until they met up with Paulsgrave Williams. They joined his crew and headed back to the Caribbean.

All of the pirates had spoken of the great treasure contained in the Whydah’s hold, but efforts to reach it turned out to be futile. Thirty feet of water was simply too much for the technology of the time to overcome. So the treasure remained on the ocean bottom. Cotton Mather’s pamphlets and notes were put away. Knowledge of Sam Bellamy and his magnificent ship the Whydah faded into local legend. It was said, in the area around Cape Cod, that a local girl, Mary or Maria Hallett, had been betrothed to a man who became a pirate.

Until Barry Clifford, researching this legend, found some notes, an old pamphlet and a map in the back storage of his local library…

Published on October 28, 2013 16:02

October 21, 2013

A Pirate's Manifesto

Sam Bellamy, who referred to the core crew of his pirate ship as “Robin Hood’s men,” and was dreaming of starting a pirate revolution, had just taken on 130 additional crew, pirates who had been left behind when their ship was destroyed by the HMS Scarborough. Well supplied with crew, and in control of two ships, the Sultana and the Marianne, Bellamy needed time to organize and hide out form the January storms. He decided on a bold move.

He was near the British Virgin Islands, and decided to attack their capital, Spanish Town. Though the home of the governor, the island had only 325 inhabitants, most of them children who had been born there. When Bellamy, with two pirate ships, and 210 pirates arrived, the authorities had no choice but to surrender.

Bellamy and his crew treated the city as if were a captured ship, going where they pleased and taking what they wanted. There wasn’t much. The pirates enjoyed fresh food, and Bellamy received gifts of money from the less reputable colonists (a fact which outraged the governor.) When the pirates sailed away two weeks later, several servants and bond slaves went with them.

Bellamy headed for the Windward Passage in the northeast Caribbean, where he hoped to ambush a larger more powerful vessel to serve as his flagship. The one he found was the Whydah.

Built only a year before, and intended for the slave trade, the Whydah was a huge ship, 300 tons, heavily armed and built for speed. Nonetheless, the captain ordered his ship to flee. The pirates gave chase. Three days and 300 miles later, they caught up.

As with his first pirating venture, Bellamy was facing a larger ship that was prepared to fight. Once again, he decided to use terror before force. He instructed all of his crew to dress as wildly as possible. The pirates donned stolen coats and wigs, jeweled cuff links, expensive hats and fine linen shirts, then lined up along the ship’s rails. On these hardened, weather beaten men, the fine clothes cold only be seen as what they were – the spoils of war. The pirates screamed out their war cries and brandished pistols, cutlasses, and primitive hand grenades. Even more frightening were the 30 former African slaves, armed and assimilated into Bellamy’s crew.

The Whydah, an 18-gun ship much larger than either of Bellamy’s vessels, surrendered without a fight.

The pirates boarded their prize to find her under the command of Lawrence Prince, a man whom Bellamy may have known personally. Prince was relieved to find the pirates in an excellent mood, and feeling generous. They planned to take his ship, but agreed to leave him the Sultana, some supplies, and £20 cash in exchange. Prince also asked for and received all the cargo the pirates found too bulky or troublesome to transport to their new ship.

The exchange took several days, and during it, the pirate bragged that they had £30,000 in gold. The merchant sailors were amazed to see that the plunder was not secured in any way. The pirates simply left bags of cash in an open room, trusting each other to ask the quartermaster to get them whatever funds they needed and keep account of the shares.

The Whydah was not carrying slaves. Bellamy, who had been kidnapping skilled carpenters from the ships he plundered, added ten cannons to the ship’s armament, stripping the Sultana of her guns. He then cut the raised platforms from the front and rear of the ship. Like a young man souping up a hot-rod, Bellamy cut away the parts of his new ship he didn’t need, making her lighter and more streamlined. As a slaver, the Whydah had needed secure, raised areas from which armed men could police the living cargo. Bellamy wanted a vessel where no man stood above another.

He also moved the ship’s bell forward. Though not immediately apparent to modern readers, this was a radical move. Ships carried their bells near the wheel, the steering apparatus, which was located on a raised quarterdeck. This was officer’s territory, and the bell gave the men their orders, marking time for beginning and ending work shifts, meals and special assemblies. When Bellamy changed the location of the bell, he changed the location of the ship’s heart, from the stern, where the officers worked, to the bow, where common sailors worked and played.

When the Sultanasailed away, the pirates held an assembly to decide what to do with their new ship. It was decided to sail north. The ship’s quartermaster, Paulsgrave Williams, had family in Rhode Island. He wanted to visit them, give them his share of the plunder, and possibly persuade them to act as fences for stolen items. Sam wanted to go back to Mary Hallett in Boston. They intended to rob ships along the way.

Williams was now in charge of the Marianne. It was now March of 1717, and a profitable pirating season seemed assured. They agreed that, if they were separated, they would meet on Damariscove Island in Maine.

The pirates took their first ship almost immediately, and added a French crew member who wanted to be a pirate. Their next prize was captained by a man named Beer. The pirates plundered his small sloop in under two hours, while Beer was held captive on the largest pirate ship he had ever seen. Despite Bellamy’s wishes, the pirate crew voted to burn the little ship. Beer later recorded Bellamy’s words.

“Damn my blood, I am sorry they won’t let you have your sloop again, for I scorn to do anyone a mischief when it is not to my advantage. Damn the sloop, we must sink her and she might have been use to you.”

Then, referring to Beer’s refusal to join the pirates, Bellamy went on. “Damn ye, ye are a sneaking puppy, and so are all who admit to be governed by laws rich men have made for their own security, for the cowardly whelps have not the courage otherwise to defend what they get by their knavery. But damn ye altogether! Damn them as a pack of crafty rascals. And you (captains and sailors) who serve them, a passel of hen-hearted numbskulls! They vilify us, the scoundrels do, where there is only this difference: they rob the poor under the cover of law, while we plunder the rich under the cover of our own courage.”

Bellamy turned his gaze back to Beers and added, “Would you not better make one of us than to go sneaking after the asses of those villains for employment?”

It took a long time for Beers to answer. He replied that he “could not find it in himself to break the laws of God and man.”

Bellamy seemed disgusted. “You are a conscientious rascal, damn ye,” he said. “I am a free Prince, and I have as much authority to make war on the whole world as he who has a hundred ships at sea and 100,000 men in the field. And this my conscience tells me…” He broke off. “There is no arguing with sniveling puppies who allow superiors to kick them about the deck at pleasure and who pin their faith upon a parson, a squab who neither practices nor believes what he tells the chuckle-headed fools he preaches to.”

Bellamy had stated his manifesto, a declaration of war against the world, its authority figures, and the ministers who claimed to represent God. And it had been written down, one of the few times a pirate’s words were recorded at the height of his power.

Next week… Storm on the horizon.

He was near the British Virgin Islands, and decided to attack their capital, Spanish Town. Though the home of the governor, the island had only 325 inhabitants, most of them children who had been born there. When Bellamy, with two pirate ships, and 210 pirates arrived, the authorities had no choice but to surrender.

Bellamy and his crew treated the city as if were a captured ship, going where they pleased and taking what they wanted. There wasn’t much. The pirates enjoyed fresh food, and Bellamy received gifts of money from the less reputable colonists (a fact which outraged the governor.) When the pirates sailed away two weeks later, several servants and bond slaves went with them.

Bellamy headed for the Windward Passage in the northeast Caribbean, where he hoped to ambush a larger more powerful vessel to serve as his flagship. The one he found was the Whydah.

Built only a year before, and intended for the slave trade, the Whydah was a huge ship, 300 tons, heavily armed and built for speed. Nonetheless, the captain ordered his ship to flee. The pirates gave chase. Three days and 300 miles later, they caught up.

As with his first pirating venture, Bellamy was facing a larger ship that was prepared to fight. Once again, he decided to use terror before force. He instructed all of his crew to dress as wildly as possible. The pirates donned stolen coats and wigs, jeweled cuff links, expensive hats and fine linen shirts, then lined up along the ship’s rails. On these hardened, weather beaten men, the fine clothes cold only be seen as what they were – the spoils of war. The pirates screamed out their war cries and brandished pistols, cutlasses, and primitive hand grenades. Even more frightening were the 30 former African slaves, armed and assimilated into Bellamy’s crew.

The Whydah, an 18-gun ship much larger than either of Bellamy’s vessels, surrendered without a fight.

The pirates boarded their prize to find her under the command of Lawrence Prince, a man whom Bellamy may have known personally. Prince was relieved to find the pirates in an excellent mood, and feeling generous. They planned to take his ship, but agreed to leave him the Sultana, some supplies, and £20 cash in exchange. Prince also asked for and received all the cargo the pirates found too bulky or troublesome to transport to their new ship.

The exchange took several days, and during it, the pirate bragged that they had £30,000 in gold. The merchant sailors were amazed to see that the plunder was not secured in any way. The pirates simply left bags of cash in an open room, trusting each other to ask the quartermaster to get them whatever funds they needed and keep account of the shares.

The Whydah was not carrying slaves. Bellamy, who had been kidnapping skilled carpenters from the ships he plundered, added ten cannons to the ship’s armament, stripping the Sultana of her guns. He then cut the raised platforms from the front and rear of the ship. Like a young man souping up a hot-rod, Bellamy cut away the parts of his new ship he didn’t need, making her lighter and more streamlined. As a slaver, the Whydah had needed secure, raised areas from which armed men could police the living cargo. Bellamy wanted a vessel where no man stood above another.

He also moved the ship’s bell forward. Though not immediately apparent to modern readers, this was a radical move. Ships carried their bells near the wheel, the steering apparatus, which was located on a raised quarterdeck. This was officer’s territory, and the bell gave the men their orders, marking time for beginning and ending work shifts, meals and special assemblies. When Bellamy changed the location of the bell, he changed the location of the ship’s heart, from the stern, where the officers worked, to the bow, where common sailors worked and played.

When the Sultanasailed away, the pirates held an assembly to decide what to do with their new ship. It was decided to sail north. The ship’s quartermaster, Paulsgrave Williams, had family in Rhode Island. He wanted to visit them, give them his share of the plunder, and possibly persuade them to act as fences for stolen items. Sam wanted to go back to Mary Hallett in Boston. They intended to rob ships along the way.

Williams was now in charge of the Marianne. It was now March of 1717, and a profitable pirating season seemed assured. They agreed that, if they were separated, they would meet on Damariscove Island in Maine.

The pirates took their first ship almost immediately, and added a French crew member who wanted to be a pirate. Their next prize was captained by a man named Beer. The pirates plundered his small sloop in under two hours, while Beer was held captive on the largest pirate ship he had ever seen. Despite Bellamy’s wishes, the pirate crew voted to burn the little ship. Beer later recorded Bellamy’s words.

“Damn my blood, I am sorry they won’t let you have your sloop again, for I scorn to do anyone a mischief when it is not to my advantage. Damn the sloop, we must sink her and she might have been use to you.”

Then, referring to Beer’s refusal to join the pirates, Bellamy went on. “Damn ye, ye are a sneaking puppy, and so are all who admit to be governed by laws rich men have made for their own security, for the cowardly whelps have not the courage otherwise to defend what they get by their knavery. But damn ye altogether! Damn them as a pack of crafty rascals. And you (captains and sailors) who serve them, a passel of hen-hearted numbskulls! They vilify us, the scoundrels do, where there is only this difference: they rob the poor under the cover of law, while we plunder the rich under the cover of our own courage.”

Bellamy turned his gaze back to Beers and added, “Would you not better make one of us than to go sneaking after the asses of those villains for employment?”

It took a long time for Beers to answer. He replied that he “could not find it in himself to break the laws of God and man.”

Bellamy seemed disgusted. “You are a conscientious rascal, damn ye,” he said. “I am a free Prince, and I have as much authority to make war on the whole world as he who has a hundred ships at sea and 100,000 men in the field. And this my conscience tells me…” He broke off. “There is no arguing with sniveling puppies who allow superiors to kick them about the deck at pleasure and who pin their faith upon a parson, a squab who neither practices nor believes what he tells the chuckle-headed fools he preaches to.”

Bellamy had stated his manifesto, a declaration of war against the world, its authority figures, and the ministers who claimed to represent God. And it had been written down, one of the few times a pirate’s words were recorded at the height of his power.

Next week… Storm on the horizon.

Published on October 21, 2013 17:17

October 14, 2013

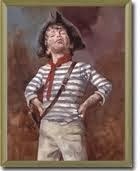

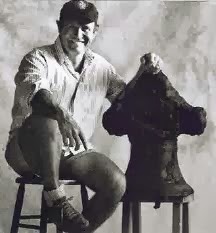

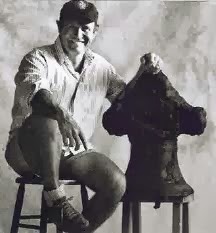

How to Make a Pirate Shirt

Halloween is right around the corner, and I wanted to give all you pirate fans a chance to make a pirate shirt in time for the holiday.

This would be a fine project for a person with just a little sewing experience. Shirts from this time were made much differently than modern dress shirts. There doesn’t need to be much cutting. Almost all the lines are straight, so you can just tear the fabric to get a perfectly straight line.

You will need:

4 ½ to 5 ½ yards of woven fabric in cotton or linen (depending on how large a shirt you will make)

A long sleeved, button down shirt that fits the person you are making the pirate shirt for.

Scissors

Pins

Needle and thread

Sewing machine (if possible)

An off-white color looks more pirate-y than a pure white shirt. Calico is also appropriate for a truly period shirt. Sailors also wore red shirts at this time, although a historically correct color would be a tomato red, rather than a blood red. Black also looks good for a pirate, or dark brown, though neither were actually used at the time.

Cut a front and a back, which are the same size. You may use the old shirt for guidance. Otherwise, measure the diameter of the wearer at the widest point (shoulders, bust or tummy) and add 12”, then divide by 2. This is your width. Length is about 30”

Cut 2 sleeves. Use the shirt to gauge length, but make then 30” wide.

Cut a collar piece, 20” long by 6” wide.

Cut 2 cuffs, each 10” long by 4” wide.

Cut 2 gussets, each one a 4” square.

Cut 1 more 4” square, and then cut it on the diagonal, to make 2 triangles.

The basic design is a straight front, and a back that his gathered at the neckline. The shoulders extend past the wearer’s natural shoulder. The sleeves are very wide and gathered at the top, where they join the shirt. Notice that the front of the shirt doesn’t open all the way down. Also notice that this shirt does not have a button closure on the sleeve cuff. Make sure the wearer can get his hand through the opening, and if necessary, cut another cuff piece and make a wider cuff opening.

Step 1

Take the front and back pieces and lay them together, one on top of the other. Pin and sew the top edges together along the shoulders, from the outside in, for seven inches only. This will leave a very wide neck hole.

Step 2 Designate one Piece the front. On this piece only, find the center, and cut a straight line from the top edge down 10 inches. This will be the front of the neck opening.

Step 3

On each sleeve, sew a gathering seam 1/2" from the edge, along one of the long (30") sides.

On the opposite side, sew another gathering seam, 12" long, centered on that side.

Step 4

Gather the long seam and attach the cuff. Repeat on the other sleeve.

Step 5

Starting at the cuff, pin the raw edges of cuff and sleeve together, closing the sleeve into a tube. Leave 4" open at the side opposite the cuff.

Step 6

With the sleeve still inside-out finish the cuff by rolling the outer raw edge back, and hand stitching it to the seamline where the cuff meets the gathered edge of the sleeve.

Step 7

Open the 4" unsewn area at the other end of the sleeve. Pin the 4" side of the square gusset to one side, and the adjoining 4" side of the gusset to the other side, as shown. Sew.

Step 8

Gather the top of each sleeve, using the 12" gathering seam inserted in step 3

Step 9

With the sleeve right side out and the body of the shirt inside out, put the sleeve inside the shirt. Line the top of the open sleeve edge (opposite the gusset) up with the shoulder line of the shirt and pin the opening of the sleeve to the shirt. Stitch the sleeve in place. Repeat with the other sleeve. Now, when you turn the shirt right side out, the sleeves will be properly placed.

Step 10

Sew a gathering seam all along the back of the neck hole, from shoulder to shoulder, and draw in the backof the neck.

Step 11

Finish the 10" cut down the center front by rolling the edges under and stitching them down.

Step 12

Stitch one of the triangular reinforcements over the end of the center cut, tucking the edges under for a finished look. (This is easier to do by hand-sewing.)

Step 13

To attache the collar, pin the center of the collar piece to the center of the gathered back neck opening. Pin the front edge of the collar to the finished edge of the front opening, leaving 1/2" of collar for hemming. Pin the length of the collar along the neck opening, adjusting the gathering at the back so that the collar fits the neck opening. Repeat on other side.

Step 14

Hem the sides of the collar. Turn collar right-side out and roll the unfinished edge under. Whip stitch the open side of the collar to the shirt neck.

Step15

Sew the sides of the shirt closed, and hem the bottom.

Well, there we have it, instructions for making your own pirate shirt! Please leave feedback in the comments, and I'll try to clarify anything that's hard to understand. I'm also uploading a video of this shirt to YouTube. Click here to see it. Please watch and comment. (But be easy on me this is my first instructional video!)

Next week: Back to Sam Bellamy's exploits in the Caribbean.

This would be a fine project for a person with just a little sewing experience. Shirts from this time were made much differently than modern dress shirts. There doesn’t need to be much cutting. Almost all the lines are straight, so you can just tear the fabric to get a perfectly straight line.

You will need:

4 ½ to 5 ½ yards of woven fabric in cotton or linen (depending on how large a shirt you will make)

A long sleeved, button down shirt that fits the person you are making the pirate shirt for.

Scissors

Pins

Needle and thread

Sewing machine (if possible)

An off-white color looks more pirate-y than a pure white shirt. Calico is also appropriate for a truly period shirt. Sailors also wore red shirts at this time, although a historically correct color would be a tomato red, rather than a blood red. Black also looks good for a pirate, or dark brown, though neither were actually used at the time.

Cut a front and a back, which are the same size. You may use the old shirt for guidance. Otherwise, measure the diameter of the wearer at the widest point (shoulders, bust or tummy) and add 12”, then divide by 2. This is your width. Length is about 30”

Cut 2 sleeves. Use the shirt to gauge length, but make then 30” wide.

Cut a collar piece, 20” long by 6” wide.

Cut 2 cuffs, each 10” long by 4” wide.

Cut 2 gussets, each one a 4” square.

Cut 1 more 4” square, and then cut it on the diagonal, to make 2 triangles.

The basic design is a straight front, and a back that his gathered at the neckline. The shoulders extend past the wearer’s natural shoulder. The sleeves are very wide and gathered at the top, where they join the shirt. Notice that the front of the shirt doesn’t open all the way down. Also notice that this shirt does not have a button closure on the sleeve cuff. Make sure the wearer can get his hand through the opening, and if necessary, cut another cuff piece and make a wider cuff opening.

Step 1

Take the front and back pieces and lay them together, one on top of the other. Pin and sew the top edges together along the shoulders, from the outside in, for seven inches only. This will leave a very wide neck hole.

Step 2 Designate one Piece the front. On this piece only, find the center, and cut a straight line from the top edge down 10 inches. This will be the front of the neck opening.

Step 3

On each sleeve, sew a gathering seam 1/2" from the edge, along one of the long (30") sides.

On the opposite side, sew another gathering seam, 12" long, centered on that side.

Step 4

Gather the long seam and attach the cuff. Repeat on the other sleeve.

Step 5

Starting at the cuff, pin the raw edges of cuff and sleeve together, closing the sleeve into a tube. Leave 4" open at the side opposite the cuff.

Step 6

With the sleeve still inside-out finish the cuff by rolling the outer raw edge back, and hand stitching it to the seamline where the cuff meets the gathered edge of the sleeve.

Step 7

Open the 4" unsewn area at the other end of the sleeve. Pin the 4" side of the square gusset to one side, and the adjoining 4" side of the gusset to the other side, as shown. Sew.

Step 8

Gather the top of each sleeve, using the 12" gathering seam inserted in step 3

Step 9

With the sleeve right side out and the body of the shirt inside out, put the sleeve inside the shirt. Line the top of the open sleeve edge (opposite the gusset) up with the shoulder line of the shirt and pin the opening of the sleeve to the shirt. Stitch the sleeve in place. Repeat with the other sleeve. Now, when you turn the shirt right side out, the sleeves will be properly placed.

Step 10

Sew a gathering seam all along the back of the neck hole, from shoulder to shoulder, and draw in the backof the neck.

Step 11

Finish the 10" cut down the center front by rolling the edges under and stitching them down.

Step 12

Stitch one of the triangular reinforcements over the end of the center cut, tucking the edges under for a finished look. (This is easier to do by hand-sewing.)

Step 13

To attache the collar, pin the center of the collar piece to the center of the gathered back neck opening. Pin the front edge of the collar to the finished edge of the front opening, leaving 1/2" of collar for hemming. Pin the length of the collar along the neck opening, adjusting the gathering at the back so that the collar fits the neck opening. Repeat on other side.

Step 14

Hem the sides of the collar. Turn collar right-side out and roll the unfinished edge under. Whip stitch the open side of the collar to the shirt neck.

Step15

Sew the sides of the shirt closed, and hem the bottom.

Well, there we have it, instructions for making your own pirate shirt! Please leave feedback in the comments, and I'll try to clarify anything that's hard to understand. I'm also uploading a video of this shirt to YouTube. Click here to see it. Please watch and comment. (But be easy on me this is my first instructional video!)

Next week: Back to Sam Bellamy's exploits in the Caribbean.

Published on October 14, 2013 21:09

Halloween is right around the corner, and I wanted to giv...

Halloween is right around the corner, and I wanted to give all you pirate fans a chance to make a pirate shirt in time for the holiday.

This would be a fine project for a person with just a little sewing experience. Shirts from this time were made much differently than modern dress shirts. There doesn’t need to be much cutting. Almost all the lines are straight, so you can just tear the fabric to get a perfectly straight line.

You will need:

4 ½ to 5 ½ yards of woven fabric in cotton or linen (depending on how large a shirt you will make)

A long sleeved, button down shirt that fits the person you are making the pirate shirt for.

Scissors

Pins

Needle and thread

Sewing machine (if possible)

An off-white color looks more pirate-y than a pure white shirt. Calico is also appropriate for a truly period shirt. Sailors also wore red shirts at this time, although a historically correct color would be a tomato red, rather than a blood red. Black also looks good for a pirate, or dark brown, though neither were actually used at the time.

Cut a front and a back, which are the same size. You may use the old shirt for guidance. Otherwise, measure the diameter of the wearer at the widest point (shoulders, bust or tummy) and add 12”, then divide by 2. This is your width. Length is about 30”

Cut 2 sleeves. Use the shirt to gauge length, but make then 30” wide.

Cut a collar piece, 20” long by 6” wide.

Cut 2 cuffs, each 10” long by 4” wide.

Cut 2 gussets, each one a 4” square.

Cut 1 more 4” square, and then cut it on the diagonal, to make 2 triangles.

The basic design is a straight front, and a back that his gathered at the neckline. The shoulders extend past the wearer’s natural shoulder. The sleeves are very wide and gathered at the top, where they join the shirt. Notice that the front of the shirt doesn’t open all the way down. Also notice that this shirt does not have a button closure on the sleeve cuff. Make sure the wearer can get his hand through the opening, and if necessary, cut another cuff piece and make a wider cuff opening.

Step 1

Take the front and back pieces and lay them together, one on top of the other. Pin and sew the top edges together along the shoulders, from the outside in, for seven inches only. This will leave a very wide neck hole.

Step 2 Designate one Piece the front. On this piece only, find the center, and cut a straight line from the top edge down 10 inches. This will be the front of the neck opening.

Step 3

On each sleeve, sew a gathering seam 1/2" from the edge, along one of the long (30") sides.

On the opposite side, sew another gathering seam, 12" long, centered on that side.

Step 4

Gather the long seam and attach the cuff. Repeat on the other sleeve.

Step 5