Mira Prabhu's Blog, page 92

July 21, 2013

Shiva’s Spectacular Gender Divide – Part 5/6

Deepa Mehta, one of our finest film-makers, was asked why she thought the attitude towards women in India is so depressingly ugly. “Patriarchy,” she retorted succinctly. “We’ve always felt that the girl child is worth nothing and should in fact be aborted even before she is born. The boy can do no wrong. If the girl is treated as a sub-human, or the boy is raised to believe he can do no wrong, then this is what will happen.”

Deepa Mehta, one of our finest film-makers, was asked why she thought the attitude towards women in India is so depressingly ugly. “Patriarchy,” she retorted succinctly. “We’ve always felt that the girl child is worth nothing and should in fact be aborted even before she is born. The boy can do no wrong. If the girl is treated as a sub-human, or the boy is raised to believe he can do no wrong, then this is what will happen.”

But India was not always this way. So what did happen?

My own elliptical quest for answers led me to partially blame the so-called sage Manu, ancient teacher of sacred rites and laws and author of the Manava Dharma-shastra (dates for the creation of this text vary all the way from 1500 BCE to 500 AD) for callously tossing the Indian gender ball down the hill. Some say Manu compiled the laws at the request of ten great sages following a great flood; others claim he was given the sacred laws by Brahma the Creator himself, rendering the Manusmriti divine.

Whatever may be the truth, Manu was no democrat, for the Brahmin (member of the highest caste) was accorded near divine status, while the Sudra (member of the lowest caste) was denigrated and reviled. The Manusmriti specified light fines and penalties for Brahmin offenders; these punishments increased in severity for guilty warriors, farmers, and serfs respectively.

Manu’s views on women in particular make me shudder. Woman, the sage pronounced, was inept, inconsistent, and prone to sensuality—and therefore unfit to exercise individual rights. As an infant, she was to be placed under the dominion of her father; as a wife, she was to be subservient to her husband; as a mother, to her sons. Were she to be widowed in her youth, she was never to marry again; if her husband was an adulterous rogue, she was still bound to consider him equal to God; while she could share in the wealth of the family, her wages were never to exceed half of a man’s wages for the same labor; and worst of all, she was prohibited from studying the sacred scriptures or participating in important social functions.

I am not surprised that the indomitable Dr. Ambedkar burnt the Manusmriti in public. Born into the lowest caste himself, this brilliant man, who battled unimaginable odds to rise to his eminent position, and who crafted the Indian Constitution, would have had excellent reason to do so. I only wish I had been there to dance around that particular funeral pyre.

The good news is that Manu’s influence was not as profound as it might have been. Indians, bless our mutinous hearts, can be notorious law-breakers; many, I am sure, would have scorned Manu’s code for its evil in rigidifying the once liberal caste system and its misogynistic stance.

In fact, my friend Taraprasad Mishra says that right up to about the eleventh century, Indians were a free-thinking lot with an extremely healthy sexual outlook. Take a look at the Kamasutra (The Art of Love-Making), where union between the sexes is elevated to an unparalleled art form. In those golden days, Indian women were free to choose their own partners and men vied with each other to win their fair hearts in a romantic tradition known as swayamvara. As for the amazing ancient temples of Khajuraho and Konarak, they depict the art of sexuality in both its proud eroticism, as well as its transcendental spirituality.

In fact, my friend Taraprasad Mishra says that right up to about the eleventh century, Indians were a free-thinking lot with an extremely healthy sexual outlook. Take a look at the Kamasutra (The Art of Love-Making), where union between the sexes is elevated to an unparalleled art form. In those golden days, Indian women were free to choose their own partners and men vied with each other to win their fair hearts in a romantic tradition known as swayamvara. As for the amazing ancient temples of Khajuraho and Konarak, they depict the art of sexuality in both its proud eroticism, as well as its transcendental spirituality.

Nor was it just sexual freedom that our beauteous maidens enjoyed—women such as Gargi, Maitreyi, Leelavati and Lopamudra engaged in spirited philosophical and political debate. As for Mirabai, a fourteenth century Rajput Princess whose heart-melting songs of adoration for the blue god Krishna are still sung all over India, she was not born into a free society as her predecessors were; however, she blazes as an example of a woman who wriggled free of an entrenched patriarchy to become an icon for the liberation of all women.

Certainly the Shakti Cult was responsible for providing women with a multitude of freedoms. Predating the Hindu faith, this movement was based on the sacred union of male and female as the balancing forces in the Universe. Male represented the physical manifestation of the “Divine”, while female represented Shakti, or non-material energy. Adherents of this path treated all females as personifications of Nature—a notion which echoes eco-feminism in new-age terminology.

And so ancient India glorified polyandrous Draupadi with her five gorgeous Pandava husbands, it extolled Mandodari, wife of the demon-king Ravana, who married her brother-in-law Vibhishana after her husband’s death; Tara wed Sugriva after the death of Bali; and Kunti had pre-marital sex—all these women were considered noble, and rightly so, for they were indeed exceptional. As for the Mahabharata, it provides proof that far from being considered a mundane pleasure, sexuality had entered the dimension of the sacred.

And so ancient India glorified polyandrous Draupadi with her five gorgeous Pandava husbands, it extolled Mandodari, wife of the demon-king Ravana, who married her brother-in-law Vibhishana after her husband’s death; Tara wed Sugriva after the death of Bali; and Kunti had pre-marital sex—all these women were considered noble, and rightly so, for they were indeed exceptional. As for the Mahabharata, it provides proof that far from being considered a mundane pleasure, sexuality had entered the dimension of the sacred.

It was after these liberal times that Muslim hordes invaded India and ruled for almost six hundred years. Hindus ordered their women to stay indoors, fearing the hot eyes of their Muslim rulers. And, as ugly fear-based patriarchal values took over, the mutual respect, friendship and love forged between our men and women dissolved into the fear and suppression we so often see today.

Now sex is a creative energy bestowed on all living creatures and inextricably aligned to the level of consciousness of a living organism. Since human beings have the highest degree of consciousness among all forms of life, sex occupies a vital place in human inner consciousness, and is therefore vastly more than a self replicating process. All ancient civilizations performed fertility rituals to celebrate the sexual energy pervading in the elemental Universe; indeed it is through the body that both body and mind can be transcended, for orgasmic ecstasy suspends the body and elevates consciousness.

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Part 5

Part 6

July 20, 2013

Shiva’s Spectacular Gender Divide – Part 4/6

On the street parallel to our home lived a Rajput family. Rajputs, as you might know, are a fierce and beautiful race, originators of Sati, the practice of urging a wife to leap on to her husband’s funeral pyre—for what is a woman worth without a man, anyway? Better to burn baby burn, and get all the endless vicious abuse a widow is subject to out of the way, once and for all. Never mind that in thousands of cases the husband is a doddering old fart, and the wife a young girl led to marital slaughter by virtuous parents. Duty and honor were considered paramount in those days, and a “good” woman was urged to end her life when her man was gone. Those who refused were drugged, thrown onto the funeral pyre, and drums were beaten loud and hard to drown out their shrieks.

On the street parallel to our home lived a Rajput family. Rajputs, as you might know, are a fierce and beautiful race, originators of Sati, the practice of urging a wife to leap on to her husband’s funeral pyre—for what is a woman worth without a man, anyway? Better to burn baby burn, and get all the endless vicious abuse a widow is subject to out of the way, once and for all. Never mind that in thousands of cases the husband is a doddering old fart, and the wife a young girl led to marital slaughter by virtuous parents. Duty and honor were considered paramount in those days, and a “good” woman was urged to end her life when her man was gone. Those who refused were drugged, thrown onto the funeral pyre, and drums were beaten loud and hard to drown out their shrieks.

Now Lakshmi, youngest of three graceful daughters born to this particular family, committed the mortal sin of falling in love with Shaukat, the attractive son of a local Muslim building contractor. Traditionally speaking, the Rajputs and the Muslims are arch enemies; so, when some spiteful gossip leaked the information to Lakshmi’s parents, her father—an important man in the Rajput community—went stark raving bonkers: Lakshmi was instantly pulled out of college, given the whipping of her life, and placed under house imprisonment. And since neighbourhood elders supported her parents for disciplining their wayward daughter in this drastic manner, not one adult attempted to ameliorate the poor girl’s fate.

Shocked, a bunch of us neighbourhood kids held a pow-pow to which we invited the grieving Shaukat. Since I was considered the bravest in that small group of rebels, it was decided that I would find out what was going on. Next morning we hid behind some bushes and waited until her father’s car drove out of their rambling house. Armed with a letter from her swain hidden in my shoulder bag, I walked in through her gate and rang the house bell. Her mother—a darkly pretty woman who spoke not a word of English, having come straight to the big city from a village near Jaipur—opened the door, probably thinking it was a salesman. I pushed past her and raced up the stairs.

Lakshmi, who had spied me entering the gate through her window, was standing at the door to her bedroom. Quickly I slipped her the love letter, trying to control my tears—in the space of a couple of days, her eyes were swollen with crying and her attractive face was covered with masses of pimples. In a low and dramatic voice I delivered Shaukat’s romantic oath—that he would rescue her one way or another and make her his bride. The light that suddenly shone through the stark misery reflected on her face made me want to cry even more.

Lakshmi, who had spied me entering the gate through her window, was standing at the door to her bedroom. Quickly I slipped her the love letter, trying to control my tears—in the space of a couple of days, her eyes were swollen with crying and her attractive face was covered with masses of pimples. In a low and dramatic voice I delivered Shaukat’s romantic oath—that he would rescue her one way or another and make her his bride. The light that suddenly shone through the stark misery reflected on her face made me want to cry even more.

Like Rajput heroines of yore, her genes had made Lakshmi not just smart, but amazingly resilient. It did not take her long to convince her father—in truth, a kind man who simply could not break free of the old ways—that she had “reformed”. Then, three years later, exactly a day past her twenty-first birthday, Lakshmi simply disappeared from the house, leaving behind all the expensive gifts her parents had given her. A note sat on her bed: “You gave me everything material,” it read in true Bollywood style, “but not my heart’s desire.”

Her father drove frantically over to Shaukat’s house. “Where’s that bastard?” he screamed in Hindi at the servant woman who stood by their gate, desultorily chewing paan. The old thing spat a stream of red betel juice over the wall. “Gone,” she announced with a shrug. “Nobody here. All family gone to Shaukat marriage.”

Almost a decade later, on my annual vacation down from Manhattan, I bumped into Lakshmi’s brother on Commercial Street. “How are things with Lakshmi? I asked anxiously. “Fine,” he replied with a grin. “They have three cute kids—two boys and a girl. Dad relented—he invited them home after their third baby. Now both our families are friends.”

A fairy-tale ending? Yes, but look at it this way: Lakshmi was patient and infinitely cunning in plotting her escape; as for Shaukat, the lad never gave up. And while I believe that Shaukat truly did love his exotic sweetheart, perhaps the Muslims wanted to teach the proud Rajputs a lesson. Most such situations would have ended in suicidal depression, murder or suicide.

Another little tale….Noor, a slender Muslim girl with a sexy overbite, joined my school as a senior. Rumor had it that she’d been expelled from her old school by the very propah Principal for hanging out with boys. Pretty in a sluttish way, Noor was clearly lacking in the brains department. Soon she was back to her old tricks—Lotharios on fast motorbikes and slicked-back pompadour hair would pick her up at the school gate at the start of lunch break and rush back with her, tousled and grinning shamelessly, just before the bell rang for afternoon class. What they managed to do in so short a time boggles the imagination.

Another little tale….Noor, a slender Muslim girl with a sexy overbite, joined my school as a senior. Rumor had it that she’d been expelled from her old school by the very propah Principal for hanging out with boys. Pretty in a sluttish way, Noor was clearly lacking in the brains department. Soon she was back to her old tricks—Lotharios on fast motorbikes and slicked-back pompadour hair would pick her up at the school gate at the start of lunch break and rush back with her, tousled and grinning shamelessly, just before the bell rang for afternoon class. What they managed to do in so short a time boggles the imagination.

Years went by and I found myself in college. One day, strolling down the main drag of our suburban neighborhood, I saw a woman waving at me from the doorway of one of the new houses that had mushroomed all around us. Garbed in purdah, carrying an infant in her arms, she did not look like anyone I would know. Curious, I walked across—and recognized the overbite—yes, it was Noor!

As she plied me with tea and pistachio barfi, Noor told me her father had forced her to marry right after school. Her husband was a businessman who treated her like dirt—almost certainly, she admitted sadly, because he was aware of her wicked past. He’d agreed to marry her only because of the huge dowry her father had offered. Noor pointed to a photo of her husband and herself on the mantelpiece; I bit my lip: just a few days ago, this same man had stopped his car as a friend and I walked down the road and, with a lecherous smirk, had asked if we would join him for a beer at Bangalore Club.

Now if this sort of stuff happened in the higher echelons of our society, what would you think of the plight of our women servants? Since it always depresses me to open that particular can of worms, I’ll tell you instead about the strapping driver employed by a friend of mine. After work, the fellow would visit one of his five mistresses—each of whom had been abandoned by her husband. The woman would fry up spicy chicken livers and serve them to him with the country liquor to which he was addicted. But if she picked a fight even for the most valid of reasons, he’d up and leave, sticking four fingers in the air—the message was this: hey, woman, if you don’t like me just the way I am, there are four others right now who’ll take me in!

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Part 5

Part 6

Shiva’s Spectacular Gender Divide – Part 3/6

Call me the family adventuress: during long summer holiday afternoons, while the rest of my family was taking their siesta or reading in bed, I’d creep out the back door and scale a wall or climb a gate to avoid being seen, in order to pay impromptu visits to my girlfriends in the hood. Inside their bedrooms, with the fan going full blast, we’d giggle and whisper and gossip as we gorged on sweets and savories.

Call me the family adventuress: during long summer holiday afternoons, while the rest of my family was taking their siesta or reading in bed, I’d creep out the back door and scale a wall or climb a gate to avoid being seen, in order to pay impromptu visits to my girlfriends in the hood. Inside their bedrooms, with the fan going full blast, we’d giggle and whisper and gossip as we gorged on sweets and savories.

One family I befriended had settled in Bangalore a generation or so ago. The man of the house belonged to a Brahmin landowning family somewhere up in Himachal Pradesh. For as long as I knew him, he spent his time seated cross-legged or slumbering on his favorite couch, perusing the papers or some crappy thriller. His wife was a very different kettle of fish; a good-looking and hard-working woman, Hindu fanatic and Sanskrit scholar, she ran the household with iron efficiency. And yet, if her indolent husband were to crook his little finger at her—demanding chai, a snack, or someone to clean his ears or trim his finger and toenails—she, or one of their two lovely daughters, would run to obey.

Unfortunately “Uncle” took a weird shine to me. One weekend I happened to drop in on the family one sultry afternoon, not knowing that my friends were away visiting relatives. Uncle opened the door and summoned me over to his couch. He handed me the paperback novel he’d been reading and pointed to a specific paragraph. “Read this out to me, please,” he ordered.

That pride goes before a fall is the utter truth; vain as I was, I began to read in a loud voice, showing off my perfect diction. It was a Harold Robbins book, and the section he had chosen luridly described the sexy heroine being banged silly by the smoldering hero.

Innocent as I was then, I still knew that something was hideously wrong with an older man asking a thirteen-year old to read him what I did not have a word for at the time—which was soft porn. In seconds I was stuttering and red-faced. Uncle took a firm grasp of my arm to prevent me from escaping. I was doing so very well, he crooned; he was so enjoying my reading. Just then his wife entered the room. With a rude flick of a pudgy hand, he ordered that proud woman out. I wriggled out of his grasp, flung the book on the floor, and hurtled out into the hot afternoon, feeling a painful mixture of emotions: among them ranked guilt and shame and rage, that I had been so badly used by a man I trusted.

I was reluctant to confide what had happened to anyone in my family mainly because I sensed that I would be blamed. Who asked you to go there in the first place? I could hear my mother shriek. Weren’t you supposed to be sleeping? What? You jumped over the wall again? You are utterly shameless and deserve everything you get! You see? Already I was aware that in the world I inhabited, the female of the species served as the eternal scapegoat. Had I complained, a variation of that old song would have been sung: “Don’t blame me! She was wearing a red dress, and so I raped her.”

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Part 5

Part 6

Part 5Part 6

July 19, 2013

Shiva’s Spectacular Gender Divide – Part 2/6

I grew up in a more or less traditional home in south India, dysfunctional as most homes all over the planet inevitably are, whether on the surface or deep in the bowels of core relationships. The tacit understanding that men ruled the roost certainly permeated our domestic atmosphere.

I grew up in a more or less traditional home in south India, dysfunctional as most homes all over the planet inevitably are, whether on the surface or deep in the bowels of core relationships. The tacit understanding that men ruled the roost certainly permeated our domestic atmosphere.

Despite his liberal attitude towards educating all his children, my father was the undisputed patriarch. None of us—least of all my dutiful and submissive mother—dared challenge even his most ridiculous orders. A brilliant and charismatic man who could enthrall a roomful of guests with his easy raconteuring, my father’s rage could incinerate, while his scathing tongue could eviscerate—and so we obeyed him without demur, at least on the shifting surface of things.

Our society was studded with double-standards that applied to every aspect of our lives. And yet most women in our community, and outside of it, it seemed to me, had accepted their lot. Some were born docile and did not see anything wrong with playing second, third or nth fiddle; others were born under a lucky star—their men were sympathetic and pliable and life appeared to be pretty damn good; still others toed the line simply because they had no option—since women were not encouraged to enter the mainstream and to fend for themselves, existence could be pure hell if they incurred the ire of their menfolk.

The Indian patriarchy, like all virulent cancers, has a gazillion ways of perpetuating itself. One major trap: every married woman was urged to have children as soon as possible. The pressure to be the mother of many sons was so enormous that many sank into deep depression when this did not happen. (Read: May You Be The Mother Of A Hundred Sons, by Elisabeth Bumiller). And once children came, so did slavery; burdened by hungry mouths to feed, at the mercy of menfolk who held firmly on to the family purse-strings, mothers had even less time to think about, let alone challenge, the patriarchy.

And God forbid a woman should complain about an abusive husband! Often she would be ostracized, by her own mother-in-law, sisters-in-law and other female elders, who would waste no time putting her “in her place”. That rare woman with the guts to fight back was attacked as a “shrew”, a hard-nosed bitch, or even a “ghodi”, meaning a horse—a fast , and therefore a bad, woman. (Naturally there were exceptions to this generalization.)

And God forbid a woman should complain about an abusive husband! Often she would be ostracized, by her own mother-in-law, sisters-in-law and other female elders, who would waste no time putting her “in her place”. That rare woman with the guts to fight back was attacked as a “shrew”, a hard-nosed bitch, or even a “ghodi”, meaning a horse—a fast , and therefore a bad, woman. (Naturally there were exceptions to this generalization.)

While my own father made no bones about his desire to transform his children into a troop of professors, doctors and diplomats, his liberal attitude did not extend to dissolving the norm of arranged marriage—a hated prospect that hung over my little rebel head like a cruel sword of Damocles. I would grumble to my mother that there was little point in educating us if we were going to be shoved into marriage and forced to have one kid after another. What’s going to happen to my fabulous brain? I’d demand. “And how can you decide who I should live with, sleep with, cook for—for the rest of my life?” (My mother would point to a gray hair or two on her head and cite me as the sole cause of her rapid aging.)

“Be a good girl now,” she would warn. “If you’re lucky, your husband will let you do whatever you want. Love comes after, not before marriage.” The word “good” was thrown at us so often that I cringed to hear it. What about being an original, excellent, humane, exciting, creative, and liberal human being?

As for bad girls—those who brought shame to the family mainly by misbehaving with boys—they were reminded that the entire family would suffer on their account. After all, which decent family would permit their children to marry into a family of bad seeds?

So poisonous doses of emotional blackmail were thrown into the simmering witches cauldron, and I for one felt more and more trapped as I moved into my teenage years.

I sought out other girls who equally dreaded the time when we would be thrust into the marriage market—to have our values assessed in terms of dowry, the fairness of our complexions, culinary and other domestic skills, and most critical of all, our ability to please husband and in-laws. (While the practice of giving dowry has been declared illegal for decades now, it continues to flourish; women are harassed, even burned to death, if their families are unable to satiate greedy in-laws. In some truly hideous cases, a man marries, gets a good dowry, kills his bride in collusion with his mother, gets away with it, either by bribing the cops or by faking a credible accident, and then goes bride-hunting again….tra la la la la).

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Part 5

Part 6

Shiva’s Spectacular Gender Divide – Part 1/6

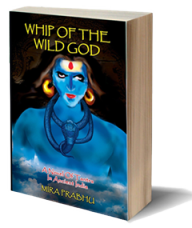

The Manhattan winter of 1992 caught me dreaming about writing an epic saga infused with the beauty of tantra. It would be set in an ancient Indian mythical civilization ruled by Rudra-Siva, the great god of paradox; somehow I intuited that this divine entity, the Wild God himself, would spark my dream into roaring life. (If you’ve looked at the post previous to this one, you’d know that Whip of the Wild God took me twenty years to complete!)

The Manhattan winter of 1992 caught me dreaming about writing an epic saga infused with the beauty of tantra. It would be set in an ancient Indian mythical civilization ruled by Rudra-Siva, the great god of paradox; somehow I intuited that this divine entity, the Wild God himself, would spark my dream into roaring life. (If you’ve looked at the post previous to this one, you’d know that Whip of the Wild God took me twenty years to complete!)

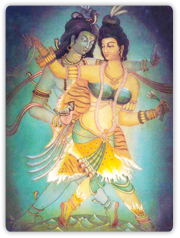

Buried in the vastness of the Tantras, I came upon an ancient saying that immediately struck me as true. It translates something like this: When Shiva set his seal upon this world, he cleaved it into male and female; when male and female come together in sacred union, Shiva blesses them with the bliss of Oneness.

Whether depicted as Ardhaniswara (half-man, half-woman), or in his contrasting roles of supreme ascetic and supreme hedonist, I knew Shiva was not speaking merely of the union of man and woman, oh no—he was equally addressing the wise celibate, who, aware that all humans contain the essence of both male and female within themselves, seeks to unite these twin polarities in his or her own being. Shiva’s point was stunningly clear: in order to be whole—which I took to mean radiating an unshakable inner joy and peace—male and female must unite; and this fusion could occur in either the practicing celibate, or through the medium of a spiritual couple.

As an Indian woman born into a multi-tiered society governed overtly and subtly by men who—by osmosis and conditioning—demean women in a million ways, it was not long before I began to mull over why all male-dominated cultures had turned into such raging battlefields for the sexes. And since each one of us who cares to investigate this subject is bound to have a unique take on the seething, often subterranean, gender wars that have ruined the fabric of our existence, on this critical subject I must speak solely for myself….

Part 1

Part 2

Part 3

Part 4

Part 5

Part 6

Part 3Part 4Part 5Part 6

June 21, 2013

Genesis: Whip of the Wild God – Part I

Neither of us being in the mood for the frenetic end-of-year partying for which Manhattan is justly famed, a friend and I decided to spend the last few days of 1993 at Ananda Ashram in upstate New York.

Neither of us being in the mood for the frenetic end-of-year partying for which Manhattan is justly famed, a friend and I decided to spend the last few days of 1993 at Ananda Ashram in upstate New York.

It was stunningly beautiful in that snow-blanketed part of the world, and I was immensely grateful for this brief respite. You see, after years of trying every damn thing to make my marriage work, I had finally left my partner of fourteen years. All I carried away with me were my clothes, some furniture, a precious collection of books and music, and the invisible festering wounds of what felt like a major failure.

Ours had been an old-fashioned marriage in its practical aspect: he had enjoyed playing the role of wily businessman, while I had easily slipped into the role of scatterbrained artiste. By convincing me I was lousy at handling money, he had assumed total control over our joint finances. I had dutifully handed him every one of my pay checks, and all our assets were in his name. His mother—an avaricious and embittered philistine—colluded with him. As his extraordinary good looks and surface charm began to pall, I could no longer hide from the wide swathe of deviousness that marred his character. Better to be alone, I realized, even as my own horizons spiralled into the mystical, than to remain in so farcical a marriage.

I told my friend Robin that I had neither a bank account nor a credit card, both of which I would need in order to break free of my marriage. The following Saturday, she escorted me to Citibank on Sixth Avenue, hovering over me like a guardian angel as I went through the motions of opening my first checking account. My knees were shaking hard—for I knew that while this single act of defiance signaled a fresh start, it would also open up a whole new can of worms. As the chorus of that terrific country rock song goes, freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose.

“I’d rather go to prison than give you one cent,” my husband said grimly, when, on the verge of leaving him, I asked for a small portion of our marital assets. Nothing I said would change his mind. Though New York divorce law was clear—each half of a divorcing couple is entitled to fifty percent of marital assets—my problem was that Big Apple lawyers cost big money. Adding salt to my wounds, the contingency law which allows a divorce lawyer to take a percentage of a settlement had just been rescinded.

“I’d rather go to prison than give you one cent,” my husband said grimly, when, on the verge of leaving him, I asked for a small portion of our marital assets. Nothing I said would change his mind. Though New York divorce law was clear—each half of a divorcing couple is entitled to fifty percent of marital assets—my problem was that Big Apple lawyers cost big money. Adding salt to my wounds, the contingency law which allows a divorce lawyer to take a percentage of a settlement had just been rescinded.

To keep from jumping out the window, I dwelt on how extraordinarily kind and generous he had been to me in our early years. No, I reminded myself, he was not intrinsically a bad guy; just congenitally unable to investigate his own gaping faults.

Instinct coupled with bitter experience warned me I’d gain nothing by fighting him. Still, I consulted a few lawyers. Every one of them asked for thousands of dollars upfront—money I did not have. Finally a friend sent me to a tough but compassionate lesbian lawyer. “My advice is to cut loose,” was her terse advice. “You’ll never pin this rascal down. Fight him in court, and you’ll lose everything, including your sanity.” I took her advice, and began life as a single, staying afloat by freelancing as an administrative temp on Wall Street and in the law firms of Manhattan.

Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

Genesis: Whip of the Wild God – Part II

Solace came in the form of hatha yoga, meditation and reading all the eastern philosophy I could get my hands on. Someone gave me Robert Svoboda’s Aghora—crude, intense, rich. His chapter on karma made one thing crystal clear to me—that none of us are victims in the big picture. Whatever we may experience—good, bad, neutral—is only the result of our own past karma—meaning, eons of thinking, speaking and acting in certain ways.

Solace came in the form of hatha yoga, meditation and reading all the eastern philosophy I could get my hands on. Someone gave me Robert Svoboda’s Aghora—crude, intense, rich. His chapter on karma made one thing crystal clear to me—that none of us are victims in the big picture. Whatever we may experience—good, bad, neutral—is only the result of our own past karma—meaning, eons of thinking, speaking and acting in certain ways.

I felt sure that the half-a-million dollars or more that I’d lost by leaving my marriage was the sole result of the karmic pendulum swinging back at me. Had I retaliated in revengeful desperation, as several feminist friends exhorted me to do, I intuited that this same pendulum would swing back with even greater force, knocking me down for the count.

Back to Ananda Ashram: my companion and I waded towards the bookstore through mounds of sparkling snow. It was the eve of our departure and I wanted a memento of our trip. I hunted out the thinnest book I could find, hoping it would also be the least expensive. I chose The Brilliant Function of Pain by Dr. Milton Ward, a devotee of the Ashram guru, mainly because the price suited my minuscule budget.

I devoured it in one fell swoop when I got back to Manhattan. Its premise is simple: that the pain we humans experience—mental, emotional, physical—has a brilliant function—which is to help us flower into our full potential. In truth, pain is our best friend–for it warns us when we are in danger. Those who cannot feel pain die quickly; imagine if you were burning to death and could not feel a thing!

That book was more than worth its weight in gold, for it mentioned a little known myth about Shiva, the mesmerizing god of paradox and the Destroyer in the current Indian pantheon. This myth claims that Shiva lashes those souls who have strayed with a psychic whip that unleashes excruciating pain. Why? Because while humans can tolerate high levels of discomfort, most of us cannot endure agony; lashed by Shiva’s whip, we are forced to spiritually ascend.

That book was more than worth its weight in gold, for it mentioned a little known myth about Shiva, the mesmerizing god of paradox and the Destroyer in the current Indian pantheon. This myth claims that Shiva lashes those souls who have strayed with a psychic whip that unleashes excruciating pain. Why? Because while humans can tolerate high levels of discomfort, most of us cannot endure agony; lashed by Shiva’s whip, we are forced to spiritually ascend.

I had no illusions about myself; I was never a saint and made no bones about it. Even as a rebellious child, I had always flirted with both dark and light. I felt as if I was split into two equally powerful selves—one hedonist, the other ascetic. Sometimes the dark side completely took over, exultantly throwing its black cloak over me, suffocating me until I longed for extinction. But when I had worked out the angst, the light would always welcome me back, suffusing my vision of the world with fresh radiance. So yes, the concept of Shiva’s whip made perfect sense to me.

In the years since, I have confirmed for myself that pain does indeed open the petals of the human heart. If we don’t know what it is to suffer—to be alone for long stretches of time with no human around with whom we can share our thoughts; to lose loved ones in tragic accidents; to be frightened out of our wits all the frigging time; to be broke in an expensive city; to be dangerously ill and friendless in a hostile place—how can we possibly empathize with others who also similarly suffer?

To understand all, as the old saying goes, is to forgive. Why forgive? Because when we trouble to investigate the underlying fabric of reasons why people think, speak and act as they do, we begin to realize that in essence we are no different; all sense of separation begins to dissolve, and we become one in our humanity. It is when we first comprehend the brilliant function of pain in our own lives that we can finally move forward, with grace and confidence.

Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

Genesis: Whip of the Wild God – Part III

Sometime in the early 90s, I put together a collection of short stories. Each tale dealt with an Indian woman who faces a terrible dilemma—and solves it with amazing panache and wile. The collection is titled: Sacrifice to the Black Goddess. My literary agent at the time had shown it to a bunch of Manhattan publishers. The universal verdict was that I had promise, but that I should first write a novel. And so the idea of writing something big and important began to stir within me.

Sometime in the early 90s, I put together a collection of short stories. Each tale dealt with an Indian woman who faces a terrible dilemma—and solves it with amazing panache and wile. The collection is titled: Sacrifice to the Black Goddess. My literary agent at the time had shown it to a bunch of Manhattan publishers. The universal verdict was that I had promise, but that I should first write a novel. And so the idea of writing something big and important began to stir within me.

In the winter of 1993, I met with James Kelleher, a brilliant vedic astrologer based in Los Gatos, California, who was on a work visit to Manhattan. Believe it or not, he saw a novel looming in my chart and said it was my dharma to bring it into the world. He even gave me the exact year I would finish it, and ended by warning me that I’d have endless problems trying to publish it; nevertheless, he stressed, I should persevere.

Writing a short story or an essay had always been pretty easy for me; a novel, on the other hand, is an altogether different kettle of fish. Being cursed with a horrifically impatient nature, I had never been able to stick to any long and complex project. I like to excel, and had done so all through school and college, but my pattern was to soon get bored and dance away to the next activity that caught my attention. Only one thing could sustain me through writing a full-length novel—a topic that consumed me from the inside out. I found this topic in the radical philosophy of Tantra, which stunned me with its liberating, profound and authentic teachings.

What is Tantra? Etymologically, it can be traced to the fusion of two Sanskrit words: tanoti and trayati, which roughly transliterate into the explosion of consciousness. The simplest definition I have found for it is: the transmutation of darkness into light.

What is Tantra? Etymologically, it can be traced to the fusion of two Sanskrit words: tanoti and trayati, which roughly transliterate into the explosion of consciousness. The simplest definition I have found for it is: the transmutation of darkness into light.

What is darkness, and what is light? Darkness pertains to man operating on the level of beast: angry, jealous, greedy, lustful, and driven by fear; light refers to man at his highest point of evolution—as pure being, consciousness and bliss.

The ascent of consciousness is from muladhara, the root chakra—dense and heavy with the awesome fiery energy of the Kundalini—all the way up the invisible line of chakras to the sahasrara, or thousand-petalled lotus of higher consciousness, hovering slightly above the crown of the skull—by which time the individual ego has dissolved back into the Self, into the infinite vastness of cosmic intelligence.

Simply put, when male and female reunite, two become one; this wholeness dissolves the individual ego that causes all our suffering, leading to a permanent state of bliss. The process can be accomplished either singly—for every human possesses both male and female energies—or as a committed couple. It can take decades before one is ready to take on a mate—a fact which flies in the face of contemporary thinking that Tantra means nothing but sexual license and excess. Without a strong grounding in ethics and the philosophy of yoga, seeking liberation as a couple simply cannot work.

By this time, I had also trained as a hatha yoga teacher. My guru had blown my mind by teaching me the essence of the Bhagavad Gita. To think I’d grown up in India and never known I’d been parking my lazy bottom on a treasure trove of great wisdom! To think an American sadhu was now tossing me sparkling jewels from my own ancient culture…and that I’d wasted my time in south India belting out Janis Joplin, smoking ciggies, and trying to be oh so cool in the western way…oh, dear me, the many ironies of this human life….

The upshot of buying that little book at Ananda Ashram was that I now I had a title for my book: Whip of the Wild God. The Wild God was Rudra, who had metamorphosed into Shiva over the centuries. The theme would be the philosophy and practice of both celibate and red tantra, which had entranced my mercurial mind.

This being the pre-internet age, I began to make regular trips to the New York Public Library in order to research this vast subject. There I would plough through their impressive stash of material on eastern philosophy. Slowly the plot for my novel began to coalesce. Ishvari—a teenage girl born in a village situated on the fringes of a city based on the Indus Valley Civilization—became my fiery protagonist. (The Indus Valley was important to me because some scholars were saying that my ancestors, the Saraswat Brahmins, had settled there, and had practiced tantra.)

This being the pre-internet age, I began to make regular trips to the New York Public Library in order to research this vast subject. There I would plough through their impressive stash of material on eastern philosophy. Slowly the plot for my novel began to coalesce. Ishvari—a teenage girl born in a village situated on the fringes of a city based on the Indus Valley Civilization—became my fiery protagonist. (The Indus Valley was important to me because some scholars were saying that my ancestors, the Saraswat Brahmins, had settled there, and had practiced tantra.)

What becomes of this fierce, beautiful and brilliant girl, scarred as she is by the tragedies of her childhood? Guided by the advice of the royal astrologer, the envoy of the Maharaja of Melukhha whisks her away to be trained for seven years by tantric monks. Despite her simmering anger against her mother, as well as the lecherous priest and greedy landlord of her village, her ability to dazzle her superiors causes her to be elected to the role of High Tantrika. And so she is sent to serve as spiritual consort to Takshak, the corrupt and powerful monarch of Melukhha.

The stars in her arresting almond eyes quickly dim when Ishvari realizes she is no more than a gorgeously plumed bird in the proverbial golden cage. Unable to deal with her chaotic emotions when her royal lover abandons her for an alien sorceress, Ishvari rebels in the worst of ways—and so brings down the wrath of the monarch on all who have loved and cherished her. It is then that the teachings she has secretly spurned rise up again within her. The agony she experiences during her flight and the years that follow awaken within her the great roaring kundalini fire….and she is set firmly again on the path to moksha or liberation.

Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

Genesis: Whip of the Wild God – Part IV

My childhood in south India imprinted me with a hatred for suffering. I once saw a man—who had doused himself with kerosene and set himself on fire—walk right past the gate of our suburban home. I still don’t know why he did what he did; servants were buzzing about it for weeks afterward, but I could not bear to hear the details. What could be so terrible that a man would set his own precious body ablaze?

My childhood in south India imprinted me with a hatred for suffering. I once saw a man—who had doused himself with kerosene and set himself on fire—walk right past the gate of our suburban home. I still don’t know why he did what he did; servants were buzzing about it for weeks afterward, but I could not bear to hear the details. What could be so terrible that a man would set his own precious body ablaze?

That Burning Man never left my consciousness; what still baffles me is that the flames scorching his body did not seem to affect him—he had staggered past our home defiantly, this blazing human torch, and I swear I don’t recall hearing him scream.

Pain, as we all discover sooner or later, comes in a range of gross and subtle flavors. Some are cursed with having to endure physical pain. My own suffering has always been emotional; to escape from the sometimes relentless inner torment of my earlier days, I confess I would do almost anything.

Unfortunately, no gentle sage manifested in a blaze of light to warn me that no one succeeds in escaping pain; like an ominous shadow, the pain demon haunts you, growing obese as it squeezes all the joy out of existence; the only true remedy is to turn around and confront the bully head-on—and keep watching until it slinks away in shame.

Today I have come to accept that all fear is essentially an illusion. In fact, folks in the Twelve Step program have an acronym for fear–False Evidence Appearing Real. And indeed, that is what our fears are—insubstantial and petty tyrants who drain us of the one thing they do not have—prana, or vital energy.

While my threshold for both physical and emotional pain continues to be abysmally low, I now have a variety of constructive tools to dissolve it—mainly, yoga, meditation and the wisdom of the ancients. The Wild God continues to whip me, because I have set my personal goal high. The difference is that now I know why I, and all beings, must suffer—before gold can shine, it must go through the trial of fire.

Now to get to the reasons why I felt compelled to write about a subject more or less taboo in my community of origin—I mean, sex. You see, I grew up with a mother who flushed at the mere mention of the “s” word. Any talk of bodily functions evoked in her an intense discomfort. Her own father had died when she was five, and she’d been brought up by a pretty and well-off, though distraught mother—a young widow who, by the customs of our people, was neither allowed to remarry, nor work outside of home. While my little mother was given the best of material things, I suspect she lacked a close bond with her own grieving mother.

And so she reached out to the nuns at her school—nuns who warned her that men in general spelled trouble. Beautiful and melancholy, my mother was married off as a teenager, against her will; she proceeded to bear many children, and not by choice. And though she did an astounding job of nurturing us, I could always glimpse in her the bewildered little girl whose life had drastically changed the day she lost her handsome father.

And so she reached out to the nuns at her school—nuns who warned her that men in general spelled trouble. Beautiful and melancholy, my mother was married off as a teenager, against her will; she proceeded to bear many children, and not by choice. And though she did an astounding job of nurturing us, I could always glimpse in her the bewildered little girl whose life had drastically changed the day she lost her handsome father.

Most likely as a result of never being properly mothered herself, my mother did not know how to deal with her own daughters as we grew into young women; we were forbidden to speak of natural things, and censored in almost every way.

One day at school a friend mentioned to me that, over the past weekend, she’d asked her Oxford-educated mother how babies were made. Her mother had instantly picked up a sketch pad and deftly sketched the male and female organs. She had then used her drawings to explain the nature of conception and birth to her nine-year old daughter. I had grown rigid with envy as I listened; my own mother’s prudishness, I felt sure, had installed shame and embarrassment in all her children about this most natural of functions.

I wrote Whip to remedy this great flaw in my own psyche—and hopefully to shed some light on the blocks and neuroses of others. As I continued to research Tantric and eastern philosophy in general, I began to see just how exalted are its teachings on sacred union. How wrong the world had gone in cheapening and trivializing this most important root energy!

Among the spiritually educated in the west today—I speak of yogis, shamans and other seekers—the balance appears to have been redressed. Sexual energy is often acknowledged as critical to spiritual growth—whether one is celibate or not. And while Tantra is still often regarded as a hedonistic and licentious practice, the truth is that many celebrated Tantrics—such as the Dalai Lama—are highly disciplined, ethical, and life-long celibates.

Sadly enough, in India, where energy teachings once flourished—I speak of Kundalini, or the serpent fire, which sages claim lies coiled three-and-a-half times at the base of the human spine—investigating primal energy as a tool for spiritual transformation is still not something you can speak frankly about. Tantra urges man and woman to view each other as divine and equal;by fusing their energies, they experience godhead. Where, I ask you, is the sin in this?

I am not talking about the tawdry manner in which sex is extolled, say, in Bollywood; nor the plethora of dirty jokes “sophisticated” Indian men and women feel free to bandy about; nor do I speak of the millions of modern Indians who, forced into arranged marriages in which they find themselves unfulfilled, seek various forms of external consolation. I address instead the honor and respect one can give to one’s own true nature.

In the ancient teachings, it is said that when Shiva set his seal on the world, he cleaved it into male and female; so when male and female re-unite in the most sacred of ways, they re-experience the state of Shiva, which is sat-chit-ananda, absolute existence-consciousness and bliss, or organic cosmic wholeness.

In the ancient teachings, it is said that when Shiva set his seal on the world, he cleaved it into male and female; so when male and female re-unite in the most sacred of ways, they re-experience the state of Shiva, which is sat-chit-ananda, absolute existence-consciousness and bliss, or organic cosmic wholeness.

To my critical eye, both Indian men and women—from the illiterate poor to the wealthy western-educated lot—have long lost their connection to this sacred wisdom. As a result, the balance between the sexes has gone radically awry. Sadly the old stereotype of either the sainted virgin or the painted whore persists. In general, there appears to be little room for pure friendship and respect between the sexes, the kind that can grow into a healthy, harmonious and holistic relationship, where there are no bars to intimacy.

Perhaps this stream of consciousness ramble might explain why I nurtured this book through many incarnations and personal ups and downs for close to twenty years. In the end, after going through hell and back, my protagonist finally awakens her own indwelling divinity; and that is what we all must do, at some point or the other in our infinite lives—for it is our birthright and our dharma.

Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

June 20, 2013

Genesis: Whip of the Wild God – Part I

Neither of us being in the mood for the frenetic end-of-year partying for which Manhattan is justly famed, a friend and I decided to spend the last few days of 1993 at Ananda Ashram in upstate New York.

Neither of us being in the mood for the frenetic end-of-year partying for which Manhattan is justly famed, a friend and I decided to spend the last few days of 1993 at Ananda Ashram in upstate New York.

It was stunningly beautiful in that snow-blanketed part of the world, and I was immensely grateful for this brief respite. You see, after years of trying every damn thing to make my marriage work, I had finally left my partner of fourteen years. All I carried away with me were my clothes, some furniture, a precious collection of books and music, and the invisible festering wounds of what felt like a major failure.

Ours had been an old-fashioned marriage in its practical aspect: he had enjoyed playing the role of wily businessman, while I had easily slipped into the role of scatterbrained artiste. By convincing me I was lousy at handling money, he had assumed total control over our joint finances. I had dutifully handed him every one of my pay checks, and all our assets were in his name. His mother—an avaricious and embittered philistine—colluded with him. As his extraordinary good looks and surface charm began to pall, I could no longer hide from the wide swathe of deviousness that marred his character. Better to be alone, I realized, even as my own horizons spiralled into the mystical, than to remain in so farcical a marriage.

I told my friend Robin that I had neither a bank account nor a credit card, both of which I would need in order to break free of my marriage. The following Saturday, she escorted me to Citibank on Sixth Avenue, hovering over me like a guardian angel as I went through the motions of opening my first checking account. My knees were shaking hard—for I knew that while this single act of defiance signaled a fresh start, it would also open up a whole new can of worms. As the chorus of that terrific country rock song goes, freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose.

“I’d rather go to prison than give you one cent,” my husband said grimly, when, on the verge of leaving him, I asked for a small portion of our marital assets. Nothing I said would change his mind. Though New York divorce law was clear—each half of a divorcing couple is entitled to fifty percent of marital assets—my problem was that Big Apple lawyers cost big money. Adding salt to my wounds, the contingency law which allows a divorce lawyer to take a percentage of a settlement had just been rescinded.

“I’d rather go to prison than give you one cent,” my husband said grimly, when, on the verge of leaving him, I asked for a small portion of our marital assets. Nothing I said would change his mind. Though New York divorce law was clear—each half of a divorcing couple is entitled to fifty percent of marital assets—my problem was that Big Apple lawyers cost big money. Adding salt to my wounds, the contingency law which allows a divorce lawyer to take a percentage of a settlement had just been rescinded.

To keep from jumping out the window, I dwelt on how extraordinarily kind and generous he had been to me in our early years. No, I reminded myself, he was not intrinsically a bad guy; just congenitally unable to investigate his own gaping faults.

Instinct coupled with bitter experience warned me I’d gain nothing by fighting him. Still, I consulted a few lawyers. Every one of them asked for thousands of dollars upfront—money I did not have. Finally a friend sent me to a tough but compassionate lesbian lawyer. “My advice is to cut loose,” was her terse advice. “You’ll never pin this rascal down. Fight him in court, and you’ll lose everything, including your sanity.” I took her advice, and began life as a single, staying afloat by freelancing as an administrative temp on Wall Street and in the law firms of Manhattan.

Read more in Part II…