Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 54

May 9, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Tia McLennan

Tia McLennan’s (she/her) poetry has appeared in variousCanadian literary journals including Riddle Fence, Vallum, Arc,CV2, Room, and Prairie Fire. In 2022, she won the NLCUFresh Fish Award for her unpublished poetry manuscript. Her first book ofpoetry, Familiar Monsters of the Flood is forthcoming in April 2024 withRiddle Fence Publishing. She holds an interdisciplinary MFA in creative writingand visual art from UBC Okanagan, and a BFA from Nova Scotia College of Art andDesign University. Originally from so-called Vancouver Island, B.C., (territoryof the K’ómoks people), she gratefully resides in kalpilin (Pender Harbour),B.C. with her partner, their 6 year old son and a big cat named Basho.

1 - How did your first bookchange your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? Howdoes it feel different?

As I write this, my first book hasyet to be born (forthcoming in April 2024) so I can’t answer this questioncompletely. Even so, having a soon-to-be book, there have already been somedoors opened that weren’t before. I still haven’t fully adjusted to the ideathat something I’ve been working on for so long in relative privacy will be outin the world and I’m curious to see how everything will unfold!

2 - How did you come to poetryfirst, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I was drawn to poetry earlyon…in Junior High and high school. I remember writing very young andwonderfully terrible poems. As a prize for getting a high mark in English Lit12, my teacher gave me a copy of William Blake’s Songs of Innocence and ofExperience. It was the first time I felt that deep magic of connecting witha poet through time and space and it kind of got me hooked. There’s a certainfreedom in poetry—it can come in so many shapes and forms and is alwaysevolving. I have a background as a visual artist and for me, visual art seemsmore closely related to poetry than other genres; I find the two speak to eachother.

3 - How long does it take tostart any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly,or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their finalshape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I don’t think I can properlyanswer this one yet, as I’ve only just started my second project. With my firstproject, it took me 2 or 3 years to realise I was writing a book, then another12 years (including an MFA and much learning, starting, stopping, and revising)to finish it. There are a few poems that come out fully or almost fully-formed,but most come out of many notes, revisions, and edits.

4 - Where does a poem usuallybegin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into alarger project, or are you working on a "book" from the verybeginning?

My first book was certainly acase of many shorter pieces coming together into various poems and a completemanuscript over a long period of time. I have notebooks filled with fragmentsand thoughts, and these are usually the seeds that I grow into something moresubstantial. My second project that I’m currently working on has been a bookfrom the beginning with an overarching theme—a new way of working for me, andit’s outside my comfort zone, a bit counter-intuitive.

5 - Are public readings part ofor counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoysdoing readings?

I do enjoy doing readings (eventhough I get pretty nervous). I like connecting with people and finding how thepoem can subtly shift depending on how I read it and the tone of the room.During the creation phase, I don’t really think about readings. I do try toread my work out loud once in a while in order to properly hear the rhythm andsounds of a piece, but I don’t start thinking about sharing my work with anaudience until it’s time for it to be published. So overall, I’d say it’s partof the process though not in an immediate or conscious way.

6 - Do you have any theoreticalconcerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answerwith your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

In my forthcoming book, thereare quite a few questions and/or theoretical concerns that drive the poems.Certainly there is a mix of ecological grief, fear, and a touch of hope which Ithink is a common concern or question of our time. The human-ecological predicamentthat (at least for me) permeates the book is “can we come back from our currentcourse toward ecological disaster?” I don’t know if anyone can really answerthis. I think, increasingly, we’re realizing we live in a time of multiple crisis.I mean, our world has been watching a genocide be livestreamed and very little hasbeen done to stop it. We’re also in a time when systems of oppression (such ascolonialism) are being more openly questioned, resisted, or dismantled and Isee this reflected through what many writers and artists are grappling with invarious ways. On a more personal level, my book investigates my relationshipwith my father, his illness and passing, and ghosts of intergenerationaltrauma. The other concern that became central to the book was learning aboutmaternal-fetal microchimera. This is the scientific term for the exchange ofDNA through the placental barrier between the mother or birth parent and fetus.Essentially (as a birth parent) your unborn child’s cells take up residence inyour body and are able to graft themselves into almost any organ and becomephysically part of you, giving you more than one set of DNA and essentiallychanging your body. The etymology comes from the Greek mythical monster knownas the Chimera (a female hybrid monster with the head & body of a lion, ahead of a goat and a tail that ended in a snake’s head). This exchange of cellshappens even if there is no live birth. After I experienced six consecutivemiscarriages, I became fascinated by the implications and unanswered questionsin this scientific area, as well as in the medical language itself. I like how thisphenomena undermines the idea of a singular, contained self. I also went downplenty of rabbit holes regarding the myth of the Chimera, and in our creationof modern-day “monsters”, and these concerns found their way into poems.

7 – What do you see the currentrole of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do youthink the role of the writer should be?

I don’t see writers having a singularrole, but some possible roles or things that writers can do that come to mindare: to notice, pay attention, listen, reflect, resist, bear witness, restore, givevoice to, challenge, entertain, celebrate. I also think a lot about being awriter (and a teacher) in this epoch where misinformation abounds, while AI(which steals from original creators) and Chat GTP rapidly change the communicationlandscape—so I’m curious to see how the role of writer will shift and adapt.

8 - Do you find the process ofworking with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

So far, in my limitedexperience, it’s been essential and wonderful. The editors I’ve been lucky towork with have provided excellent insights and direction without beingoverbearing or insistent. Sometimes an editor will give feedback and it willtotally ring true, but it means the poem has to fall apart and be rebuilt. Thiscan be difficult, but has always resulted in a stronger piece of writing.

9 - What is the best piece ofadvice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

It was from a visual artistfriend of mine and it was simply to continue. There’s usually plenty ofrejection and can be a lot of interruption (especially as a parent) on thecreative path. To find even small ways to continue and move forward is theadvice I continue to give myself.

10 - What kind of writingroutine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day(for you) begin?

I have no real routine and wishI could be more disciplined in this department. I currently work as a teacheron call three days a week and have a couple of days dedicated to writing. I’malso a parent of a very active & freedom-loving almost 6-year-old, so lifeis busy. On my writing days, I drop my son off at school and then do my best toget at least 3-5 hours of writing/reading/research done. I often getside-tracked by gardening, house work and/or life admin tasks. If I’m workingfull time, there’s virtually no time to write and I rely on sporadic moments oronce in a while stay up late to get some words down.

11 - When your writing getsstalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?

I think it’s important when Ido truly feel stuck, to give the writing and myself a break from each other andI usually just read until I can catch the spark or impetus again. I’ll returnto some writers that continue to be a compass for me (whether it’s poetry orother genres) and will often seek out new (to me) writers. Also, being innature, moving my body, or having a visit with a good friend can all help shiftmy frame of mind.

12 - What fragrance reminds youof home?

Cedar, seaweed, fried onionsand garlic, coffee.

13 - David W. McFadden oncesaid that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influenceyour work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I totally agree to a certainextent. As a writer, I think I’ve learned the most about craft and voice throughreading others’ work. So books remain the biggest influence and I love theobject of them, but influences come from endless sources. We (or most of us)live in this constant deluge of information, which is both miraculous andnightmarish—this aspect of our world certainly influences my writing. Being outin nature and our view of and relationship to “nature” absolutely is somethingI question through my poems. My forthcoming book relies on found text frommedical records, and I am interested in scientific language—its etymology andsounds. My background and schooling is in visual art and I find writing and artmaking are very much connected for me, not in the ekphrastic sense, but in how thetwo creative processes play off each other.

14 - What other writers orwritings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

There are many! To name a fewand in no particular order: Liz Howard, Tomas Tranströmer, William Blake, Natalie Diaz, C.D. Wright, Joan Didion, Joshua Whitehead, Seamus Heaney, Karen Solie,Jordan Abel, Adrienne Rich, Mary Ruefle, Sue Goyette’s Ocean, AlanWeisman’s The World Without Us, Brenda Shaughnessy, Ocean Vuong, Canisia Lubrin, Emily Dickinson, Tracy K. Smith’s Life on Mars, Louise Glück, Leah Horlick.

15 - What would you like to dothat you haven't yet done?

There’s a long list that includestravel to distant lands. But my current daydream/obsession is to try and growshiitake mushrooms on inoculated logs.

16 - If you could pick anyother occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do youthink you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Botanist, horticulturalist, gardener.I do currently have a job as a teacher, a profession I really love, but beingpaid to be outdoors with plants would be pretty dreamy.

17 - What made you write, as opposedto doing something else?

First I did something else. That is,I went to art school (Nova Scotia College of Art and Design) for my undergrad.I’d always written but never took it seriously. When my father was ill andafter he passed, I had time to reflect and basically decided to turn mycreative focus toward writing. My MFA from UBCO was interdisciplinary—in visualart and creative writing, though I ended up leaning more toward the creativewriting. I still loosely keep up a visual art practice(drawing/painting/printmaking/collage), it’s still important to me, but writingbecame more essential, a more direct channel of expression.

18 - What was the last greatbook you read? What was the last great film?

Too hard to name just one! I readOcean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous in the past couple yearsand was incredibly moved. I’m currently immersed in (and in awe of) CanisiaLubrin’s Code Noir, Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass,and Danielle Vogel’s A Library of Light. I absolutely loved the film Everything Everywhere All at Once, directed by Daniel Kwan and DanielScheibert—it had me laughing so hard I was in tears.

19 - What are you currentlyworking on?

I’m working on ahybrid book rooted in non-fiction, and memoir. It’s based on and from the placemyself and my family have recently returned to live—Garden Bay, kalpílin(Pender Harbour), B.C., unceded territory of the shíshalh nation. This is wheremy father retired to in 2003, and then sadly passed away from cancer in 2006.I’m interested in the history (recent, colonial and pre-colonial), and want topay specific attention to the capture and subsequent sale of half a pod ofnorthern resident orcas from Garden Bay in 1969. Writing from a time and place ofongoing drought, I’m questioning and thinking about my (and our) relationshipwith the land and waters and wondering how we will navigate climate crisis and movetoward a sustainable and just future.

May 8, 2024

Travis Sharp, Monoculture

in the distance, a man

body flexing in labor

standing so far from the combine

he looks nearly of size with it

they’re plants,they’re

people, they’replanted

potted one

dutifully pruned

new growth cut back

“to be fucked

in the fruits

of some labor”

and in deep

debt to the sun

Theauthor of the full-length debut,

Yes, I Am a Corpse Flower

(Knife ForkBook, 2021) [see my review of such here], the poetry pamphlet

Behind the Poet Reading Their Poem Is a Sign Saying Applause

(Knife Fork Book, 2022)and the chapbooks

Sinister Queer Agenda

(above/ground press, 2018) and

OnePlus One Is Two Ones

(Recreational Resources, 2018), the second full-lengthcollection by American poet and editor Travis Sharp is

Monoculture

(Greensboro NC: Unicorn Press, 2024). Composed as a book-length lyric suite, I haveto admit that, even beyond my enthusiasms for Sharp’s work, I’m already partialto any collection that opens with a quote by Denver poet Julie Carr, a quartetof lines pulled from

100 Notes on Violence

(Ahsahta Press, 2010;Omnidawn, 2023): “Under the immense pleasure of conformity, I find myself /delivering // flower boxes with body parts // Under the immense comforting planeof conformity— [.]”

Theauthor of the full-length debut,

Yes, I Am a Corpse Flower

(Knife ForkBook, 2021) [see my review of such here], the poetry pamphlet

Behind the Poet Reading Their Poem Is a Sign Saying Applause

(Knife Fork Book, 2022)and the chapbooks

Sinister Queer Agenda

(above/ground press, 2018) and

OnePlus One Is Two Ones

(Recreational Resources, 2018), the second full-lengthcollection by American poet and editor Travis Sharp is

Monoculture

(Greensboro NC: Unicorn Press, 2024). Composed as a book-length lyric suite, I haveto admit that, even beyond my enthusiasms for Sharp’s work, I’m already partialto any collection that opens with a quote by Denver poet Julie Carr, a quartetof lines pulled from

100 Notes on Violence

(Ahsahta Press, 2010;Omnidawn, 2023): “Under the immense pleasure of conformity, I find myself /delivering // flower boxes with body parts // Under the immense comforting planeof conformity— [.]”Sharp’sMonoculture works a collage-effect, weaving the elegy across Americanhistories, including the interwoven histories of slavery and commerce, specificallythe cotton industry, “(and how it’s still felt,” he writes, “encroachment of /overwhelm, even to this / day, today, it’s all too / much, there is danger /there, danger, there, it / comes up, again, / danger, there, and, this /throat, cottoning up, in / the face, of— // still—) [.]” Set as a book-lengthlyric suite, the poems of Monoculture are tethered together across thelength and breadth of eighty pages, yet clustered into untitled groupings, eachpoem an untitled fragment that adds to an accumulation across (as the backcover offers) “the economic, social, racial, religious, and sexual dimensionsof currency in America. Travis Sharp begins with cotton crops in the South andfollows the tendrils of consequence wherever they lead: into the food we eat,the work we do, the prayers we pray—and into the hungers that are never sated,the work that is never done, the prayers that are never said.” The effect isaccumulative, allowing one to open the book at any point and see the linestretching out across both directions, from the ending all the way back to thebeginning, wrapping critical observation and archival material with the mostbeautiful music. “we live among the plants we love among the plants we grazeamong the plants we gaze / among the plants we thrive among the plants we diveamong the plants we strive among the / plants we plead among the plants weplease we please oh please among the plants [.]” Through the shape of this singlenarrative thread, this long, accumulative poem, Sharp questions and examinesthe implications of such supply chains, especially those underplayed, yetessential to both American development and growth, all the way back to thoseoriginal foundations. As Sharp asks, mid-way through the collection: “and whatdoes it mean to hold cotton / unformed by labor? and what does it mean / forthe cotton unformed by labor to be the / product of labor? and what does itmean / that father child labored in those fields for / his own father whounlabored for rich men / to bag that cotton? and what does it mean / that afterthe beatings he came to pick / faster and faster, his arms slashing/ throughthe fields?”

May 7, 2024

Concetta Principe, DISORDER

Like Emily who bound

her disorder to her last

reclusive poet years,wearing

walls of her room as aplaster

hijab, anachronisticallyapplied

here

she veils herself withbrick

and mortar

on foundations

that weep (“SAD THIGHS”)

Thelatest from Peterborough-based “award-winning poet, and writer of creative-nonfiction, short fiction, as well as scholarship that focuses on traumaliterature” Concetta Principe is the poetry collection,

DISORDER

(GuelphON: Gordon Hill Press, 2024), following her collections Interference (TorontoON: Guernica Editions, 1999) and This Real (St Johns NL: Pedlar Press, 2017).DISORDER is composed with a focus on neurodiversity, the focus of whichis quite unique, and an important one; working meditative stretches while attendingan open conversation aimed toward dismantling stigma. Composing her DISORDER,Principe offers poems not as the opposite of “order,” but through a structure requiringits own attention, composing crafted lyrics on what isn’t a problem to besolved but a difference of perspective. “Just so you know knots / are thepyrotechnics of appetite // repressant;,” she writes, to open the poem “ICINGON THE CAKE,” “a kink in the intestine / of this birthday cake // wrapped infrosted lake; [.]” Principe utilizes the lyric as a sequence of narrativethreads that work to examine, unpack and document the way she thinks and movesthrough the world, and there are echoes in her meditations that remind of worksby Pearl Pirie, or Phil Hall, attempting to discern how the world works (or doesn’twork) through language (including a stellar cluster of prose poems). As shewrites as part of her “Notes and Acknowledgements” that closes the collection:

Thelatest from Peterborough-based “award-winning poet, and writer of creative-nonfiction, short fiction, as well as scholarship that focuses on traumaliterature” Concetta Principe is the poetry collection,

DISORDER

(GuelphON: Gordon Hill Press, 2024), following her collections Interference (TorontoON: Guernica Editions, 1999) and This Real (St Johns NL: Pedlar Press, 2017).DISORDER is composed with a focus on neurodiversity, the focus of whichis quite unique, and an important one; working meditative stretches while attendingan open conversation aimed toward dismantling stigma. Composing her DISORDER,Principe offers poems not as the opposite of “order,” but through a structure requiringits own attention, composing crafted lyrics on what isn’t a problem to besolved but a difference of perspective. “Just so you know knots / are thepyrotechnics of appetite // repressant;,” she writes, to open the poem “ICINGON THE CAKE,” “a kink in the intestine / of this birthday cake // wrapped infrosted lake; [.]” Principe utilizes the lyric as a sequence of narrativethreads that work to examine, unpack and document the way she thinks and movesthrough the world, and there are echoes in her meditations that remind of worksby Pearl Pirie, or Phil Hall, attempting to discern how the world works (or doesn’twork) through language (including a stellar cluster of prose poems). As shewrites as part of her “Notes and Acknowledgements” that closes the collection:This project cametogether retroactively. I had been writing these pieces to document experience,frustration, rawness, daily trouble and their scabs. The diagnosis changed myperspective on what I’d been doing and highlighted for me what I’m calling theproduct of a high functioning BPD: some pieces pretend to be ‘normal’ and otherpieces struggle with ‘normal,’ and underlying this is the child playing againstthe brick wall of ‘normal.’ It is thanks to Shane Neilson, who has beensupporting my work for several years now, that this project of an atypical ‘a-normal’life has an audience. I am so very grateful and indebted to Shane for creatingthis forum for disabilities discussion in which I, among others, may have apublished voice.

May 6, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Julie Paul

Julie Paul’s

second book of poetry, Whiny Baby (2024),follows the 2017 release of the poetry collection

The Rules of the Kingdom

, both published with McGill-Queen’sUniversity Press. She is also the author of three short fiction collections,

The Jealousy Bone

(Emdash, 2008),

The Pull of the Moon

and

Meteorites

(both Touchwood Editions,2014 / 2019).

Julie Paul’s

second book of poetry, Whiny Baby (2024),follows the 2017 release of the poetry collection

The Rules of the Kingdom

, both published with McGill-Queen’sUniversity Press. She is also the author of three short fiction collections,

The Jealousy Bone

(Emdash, 2008),

The Pull of the Moon

and

Meteorites

(both Touchwood Editions,2014 / 2019).Julie’spoetry, fiction and CNF have been widely published and recognized; The Pull of the Moon won the 2015Victoria Book Prize, The Rules of theKingdom was a finalist for both the Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize and theGerald Lampert Memorial Award, and her personal essay “It Not Only Rises, ItShines” received TNQ’s Edna Staebler Personal Essay Award.

Unlessshe’s visiting her daughter in Montreal, Julie lives in Victoria BC, where, inaddition to writing and playing with paint, she works as a Registered MassageTherapist.

1- How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your mostrecent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Myfirst book, The Jealousy Bone, was short fiction, and it taught me howto get behind my writing in a way I hadn’t before. Since then I’ve publishedtwo more books of short fiction as well as two poetry collections, includingthe brand new Whiny Baby. Both poetry collections are largely personal,confessional & intimate; the first one, The Rules of the Kingdom, feltscarier than this one, just because it was my first foray into truth-tellingwithin the covers of a book. I have, however, published a number of personalessays over the past decade, and those are even more revealing!

2- How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

Icame to poetry first, as a pre-teen, but then got pulled into the fictionalworld, enticed by the freedom of making stuff up and having more space to workwithin.

3- How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does yourwriting initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appearlooking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copiousnotes?

Thestarting is the easy part—love me a fun first draft! Sometimes, the final draftcomes fast as lighting. Other times, years and years (I’m looking at you, novelmanuscript).

4- Where does a poem or work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an authorof short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you workingon a "book" from the very beginning?

Allof my books thus far have been conceived after I’m well into writing variouspieces; however, I’m currently working on a novel and a book of poems that havespecific parameters, so we’ll see how that goes.

5- Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you thesort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Ido enjoy readings; it is always such a gift to hear any kind of response to mywork, esp. in “the real world.” I try to leave my imposter syndrome at home.

6- Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds ofquestions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think thecurrent questions are?

Currentconcerns: How to live in the world despite the world. How to love. How towrestle with dissatisfaction and recognize privilege. How to make amends.

7– What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Dothey even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Reflectors.Mirrors. Comforters. Provokers. Entertainers. Not necessarily at the same time.

8- Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult oressential (or both)?

Ifind it essential, and overall, I’ve had very good experiences with editors,both informally in my writing circles and with my publishers. They see things Icannot, being too close to the work.

9- What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to youdirectly)?

Thisis one I give myself: There is room for everyone.

10- How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to shortstories)? What do you see as the appeal?

Ilove variety in life; I’m a restless soul. So moving around in multiple genressuits me really well.

11- What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one?How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I’mnot much of a routine follower, but I do try to write most days. Preferablywhen I’m the only human at home and the cats are napping. Cookies help.

12- When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack ofa better word) inspiration?

Igo for a hike, or pick up a book and open it at random. Having the support ofvarious writing buddies really helps, and I’ve had the good fortune to havetaken two weekend retreats with them this year. Or I take a course; I’ve had somuch fun doing Yvonne Blomer’s fabulous online classes over the past couple ofyears, and they’ve helped me to generate plenty of poems. Currently it’sNational Poetry Writing Month, so those prompts can help get the juicesflowing, but right now they’re piling up, unexplored…

13- What was your last Hallowe'en costume?

I’mnot a big fan of this holiday, truth be told, so it’s been years. But myfavourite costume from when I was a kid was Boss Hogg from The Dukes ofHazzard, complete with plastic cigar. Now I’m showing my age…

14- David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there anyother forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visualart?

Knowingwhat I know of the body, from my training as a massage therapist, has made itinto my work in all genres. Nature is always an influence, and the nature ofbehaviour, both human and otherwise.

15- What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply yourlife outside of your work?

Sucha hard question, to narrow things down. I’ll offer a list of recent inspiringworks: Snow Road Station by Elizabeth Hay—set in my original neck of the woods.Anything I’ve read so far of Maggie O’Farrell’s. Eula Biss is a fantastice ssayist. Claire Keegan’s quiet intense fiction. This Strange Garment, poetryby Nicole Callihan. Ellen Bass’s Indigo. Abigail Thomas’s books. The novelAstra by Cedar Bowers.

16- What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Makecroissants from scratch. Try oil painting. Publish a novel.

17- If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or,alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been awriter?

Visualartist, baker, café owner. I play around with paint a lot these days, as wellas baking, esp. sourdough (thanks, pandemic).

18- What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Ithink it’s an innate affinity for words. Or maybe a tendency to overshare. WhenI don’t write, I get really grumpy, so possibly it’s self-preservation aboveall.

19- What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Iloved Maggie O’Farrell’s novel This Must Be the Place. And Poor Things—what a wild ride of a movie!

20- What are you currently working on?

I’mcurrently rewriting my novel, and slowly working on a collection of personalessays, as well as a book of poems. Oh, and there’s a loaf of bread proofing inthe kitchen.

May 5, 2024

Hamish Ballantyne, Tomorrow is a Holiday

practice instrument

practice merest doing

the Holberg photograph is

as Julian never ceasessaying a

return of the repressedas Julian

never ceases saying is anexcess of

life the act precededendless times

in a company town soondeclared non-viable

awaiting showtime.AWAITING SHOWTIME

whether that’s annihilationof all practices

or the moment to put your

into practice until

performance at last denotedby

the um, tragic

then bacon it’ll

be as is our custom

for unexpected

visitors (“Hansom”)

I’mintrigued by the quartet of sequences that make up Vancouver poet Hamish Ballantyne’sfull-length poetry debut, Tomorrow is a Holiday (Vancouver BC: New StarBooks, 2024), a title that follows his chapbooks Imitation Crab (TorontoON: knife|fork|book, 2020) and Blue Knight (Durham NC: Auric Press,2022). Composed across the sequences “Hansom,” “Luthier,” “A&Ws” and “ROCKROCK CORN ROCK,” Tomorrow is a Holiday is, as the back cover offers, “a witnessat the margins,” all of which provides a curious and amorphous shape to thatabsent, outlined centre. “a letter from jimmy buffett to / benjamin treatingthe form,” he writes, as part of the third sequence, “of appearance of movementarrested / in the billboards advertising / billboard space: a whale encounters/ an enormous incarcerated krill in a submarine [.]” There’s a lustre of theKootenay School of Writing language-infused work poetry across Ballantyne’slyrics, one that acknowledges labour, even across the patina of holiday,comparable to recent works by Vancouver poet Ivan Drury [see my review of his full-length debut here], Vancouver poet Rob Manery [see my review of his latest here], Winnipeg poet Colin Smith [see my review of his latest here], Windsor-based poet Louis Cabri [see my review of his latest here], Roger Farr [see my review of one of his latest here] or Vancouver poet Dorothy Trujillo Lusk [see my review of her latest here]. He speaks to the thingsaround those things that are also around those things, writing rings aroundrings around that absent presence of centre.

what’s attempting escapewhen shaking

surprised by your ownresponse

seized by something inthe air

and the airs of the body

my brain contains insanearchitectures that compare

to the formation, timeliness,and cultural import of flying

crows in this part of thecity

we must ask what’s in thebox

who put it there and thebox

there

we must ask why there’s askeleton on a throne

not what he’d look likewith skin (“A&Ws”)

Theevolution and trajectory of “work poetry,” a term coined from within a 1970sBritish Columbia terrain of poets including Tom Wayman and Kate Braid, was onethat emerged out of a focus on and acknowledgement of labour and labour issuesthrough a relatively straightforward lyric. Other poets, interestingly enough,that moved through this cluster of poets included Erín Moure and Phil Hall. Thereare some that might forget that Wayman, and this work poetry ethos, was aco-founder of The Kootenay School of Writing, although this focus on a more straightforwardlyric was one eventually jettisoned by those members of KSW that followed. Curiously,the attentions to labour became fused with the language-informed poetic that KSWwould be known for (anyone interested in further conversations around the historyof The Kootenay School of Writing should pick up either Michael Barnholden’s anthology around such or Clint Burnham’s critical work on same [see my review of such here]. Think of writing by Michael Barnholden, Jeff Derksen, Lisa Robertson, Christine Stewart, Deanna Ferguson or Judy Radul. Through an attentionto a particular flavour of language and labout, Ballantyne’s Tomorrow is aHoliday, then, becomes not only one of the inheritors of this particularsequence of traditions, but an impressive feat in how one moves forward.

Theevolution and trajectory of “work poetry,” a term coined from within a 1970sBritish Columbia terrain of poets including Tom Wayman and Kate Braid, was onethat emerged out of a focus on and acknowledgement of labour and labour issuesthrough a relatively straightforward lyric. Other poets, interestingly enough,that moved through this cluster of poets included Erín Moure and Phil Hall. Thereare some that might forget that Wayman, and this work poetry ethos, was aco-founder of The Kootenay School of Writing, although this focus on a more straightforwardlyric was one eventually jettisoned by those members of KSW that followed. Curiously,the attentions to labour became fused with the language-informed poetic that KSWwould be known for (anyone interested in further conversations around the historyof The Kootenay School of Writing should pick up either Michael Barnholden’s anthology around such or Clint Burnham’s critical work on same [see my review of such here]. Think of writing by Michael Barnholden, Jeff Derksen, Lisa Robertson, Christine Stewart, Deanna Ferguson or Judy Radul. Through an attentionto a particular flavour of language and labout, Ballantyne’s Tomorrow is aHoliday, then, becomes not only one of the inheritors of this particularsequence of traditions, but an impressive feat in how one moves forward.Ifsome poems, some collections, give the appearance of including everything, thenthat is the space around which Ballantyne’s poems exist: focusing instead uponeverything else, attending the minutae of side moments, sidebars and marginsacross a wide distance. As the sequence “A&Ws” continues: “As property grewthey moved / forever to outside edge of the fence / even after they were out ofsight / of bend in the river they / liked so much [.]” I’m fascinated by thepoems in the final section, “ROCK ROCK CORN ROCK,” subtitled “ThreeTranslations of San Juan de la Cruz.” Also known as Sant John of the Cross, theSpanish Priest and Mystic was born in Castile in 1542 and died in 1591, beingone of the major figures in the Catholic Church for his writing, threesequences of which sit at the end of Ballantyne’s collection. Through Ballantyne’stranslation, these meditatative sequences offer further ripples across his own “restlesscuriosity,” continuing an abstract conversation around a kind of moralauthority on attention, being and being in and of the very moment, as theseventh of ten poems that make up the third and final sequence, “DARK NIGHT OFTHE SOUL,” reads:

porch light

night crouched low in thetruck bed

church light

wife light

dream light (kid is orhitting

piano swimming

pool

skinny horse

loved loved loved lovedloved

(there are other

lights too)

via some grammatical weftsuddenly

hear own pavementfootsteps

I am in the dark

passing the store

passing the pet store

May 4, 2024

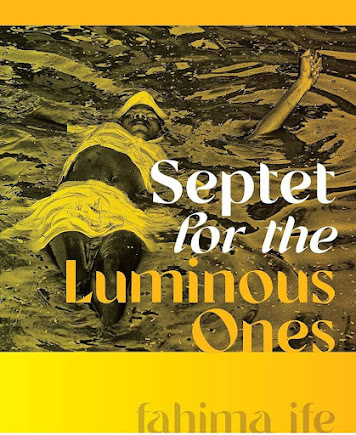

fahima ife, Septet for the Luminous Ones

and everything beneathour feet

is open for a second

the next general strike

to end all general

strikes

is at the helm of a siren

out west

pointe is in

the horizon

and out of touch

at the point there is

a playable field

a delicate blur

a line of empty vessels

an empty line of

vacation homes

a dead seal

down

below (“acid west”)

I’mfascinated at California-based fahima ife’s self-declaration as a “devotional lyricalpoet,” a phrase included in the author biography for her second full-lengthcollection,

Septet for the Luminous Ones

(Middletown CT: WesleyanUniversity Press, 2024), a collection that follows her full-length debut,

Maroon Choreography

(Durham NC: Duke University Press, 2021). One might attempt toseek clarification on whether she is devotional and a lyric poet or a poet ofthe devotional lyric, but I might suspect she a combination of the two,offering a lyric of sound and cadence, gestures that leap off the page inperformance. These are poems that don’t simply require to be heard aloud, butmanage to present themselves on the page as performance. “dust a distal broomcorners vestibular inquisition number seven / vernacular insinuation numbernine” begins the poem “of spirit, artificial symbiont,” “a blue dust pan / adusty flute song a boy in love// a staggering impulse to burn / then turn the fleeting lust as funk [.]” ife’slanguage offers such vibrancy, a propulsive and delightful oscillation and pauseand choral that speaks of and to and through the very notion of devotion, heartand a hush, afterlife and time, desire and ritual, trauma and celebration,seeking to expand the light and lift up the dark. “what is the word / for thething // like a traumatic / brain injury,” she writes, to open the poem “afterlifeof the party, the order of time,” “not involving a / physical blow / to thehead // but a sensual blow / to locale of sense // of being in time / and space/ beyond / limits [.]” Through these lines, it would be impossible to not feellifted.

I’mfascinated at California-based fahima ife’s self-declaration as a “devotional lyricalpoet,” a phrase included in the author biography for her second full-lengthcollection,

Septet for the Luminous Ones

(Middletown CT: WesleyanUniversity Press, 2024), a collection that follows her full-length debut,

Maroon Choreography

(Durham NC: Duke University Press, 2021). One might attempt toseek clarification on whether she is devotional and a lyric poet or a poet ofthe devotional lyric, but I might suspect she a combination of the two,offering a lyric of sound and cadence, gestures that leap off the page inperformance. These are poems that don’t simply require to be heard aloud, butmanage to present themselves on the page as performance. “dust a distal broomcorners vestibular inquisition number seven / vernacular insinuation numbernine” begins the poem “of spirit, artificial symbiont,” “a blue dust pan / adusty flute song a boy in love// a staggering impulse to burn / then turn the fleeting lust as funk [.]” ife’slanguage offers such vibrancy, a propulsive and delightful oscillation and pauseand choral that speaks of and to and through the very notion of devotion, heartand a hush, afterlife and time, desire and ritual, trauma and celebration,seeking to expand the light and lift up the dark. “what is the word / for thething // like a traumatic / brain injury,” she writes, to open the poem “afterlifeof the party, the order of time,” “not involving a / physical blow / to thehead // but a sensual blow / to locale of sense // of being in time / and space/ beyond / limits [.]” Through these lines, it would be impossible to not feellifted.May 3, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Allie Duff

Allie Duff is a multidisciplinary artist from St.John’s, NL whose writing has been published in various Canadian literarymagazines. Allie also performs stand-up comedy and was featured on 2023’s JustFor Laughs album Stand-Up Atlantic: The Icicle Bicycle. Her first bookof poetry — I Dreamed I Was an Afterthought — appeared May 1, 2024 withGuernica Editions.

1 - How did your first book change yourlife? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feeldifferent?

Publishing a book was a goal that I had from a veryyoung age. Now that I’ve accomplished that goal, I have no idea what to donext! The logical thing would be to publish another book, I suppose…

2 - How did you come to poetry first, asopposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

My friend told me a story about how, when they were akid, their sisters would always read their diary. In an attempt to concealsecrets they started writing their diary entries in ‘code.’ Their theory wasthat this led to writing poetry. This rang true to me as well – I also wrote ina secret ‘code’ in my early diary entries.

Also my dad is a musician so I was always surroundedby lyrics and cadence.

3 - How long does it take to start anyparticular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is ita slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, ordoes your work come out of copious notes?

It’s so slow. I do a lot of research and take a lotof notes. I walk around the city a lot, probably talking to myself withoutrealizing it. I also have countless unfinished projects, thanks to my ADHD.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin foryou? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a largerproject, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Usually it’s a mix of both. There are plenty of poemsthat come to me as single pieces and they don’t belong to a larger work. Forprojects with a particular theme, though, I’ll end up writing a bunch of poemsthat are part of a whole (and sometimes short pieces end up melding into longpoems.)

5 - Are public readings part of orcounter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doingreadings?

I think public readings are great. There’s nothingquite like reading a poem aloud to figure out what is and isn’t working in thepiece. Being on stage is also fun for me.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concernsbehind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with yourwork? What do you even think the current questions are?

Apparently my writing is very millennial, which Ifeel is unavoidable because that’s my generation. I’m always trying to fightthe despair of living a dystopic late-capitalist life.

7 – What do you see the current role ofthe writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you thinkthe role of the writer should be?

I think right now writers play a role in keepingpeople’s empathy alive. We’re all so overwhelmed with info from social media –there’s so much content that it’s easy to burn out and tune out.

A poem that went viral on social media recently,called “there’s laundry to do and a genocide to stop” by Vinay Krishnan, is evidence, Ithink, that poets are still influential. Maybe we’ve got to go viral to beheard, but poetry certainly isn’t dead, and it has some of the greatest abilityto move people and spread awareness.

8 - Do you find the process of workingwith an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Before I sent my manuscript to publishers, I asked myeditor friend David Pitt to look over the poems for me. It was incrediblyhelpful! Then with Guernica I got to work with their First Poet’s Serieseditor, Elana Wolff; I can’t thank her enough for her careful eye and generalpoetic wisdom.

9 - What is the best piece of adviceyou've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Get used to rejection. I started sending poems toliterary magazines right after high school, and I had no idea back then howmany times (countless times, even) that I’d be rejected before I’d startgetting accepted more regularly. I’m not a very prolific writer, so I onlysubmit maybe 5 or 6 times a year. Essentially that means I might go a wholeyear without publishing anything. So yeah, don’t let rejection bother you.

This advice is also applicable to people over 30 ondating apps…

10 - How easy has it been for you to movebetween genres (poetry to music to stand-up)? What do you see as the appeal?

The biggest difficulty is trying to dedicate enoughtime to each craft (there’s never enough time). I find it hard to set onediscipline aside so that I can focus on the others. If I do, I end up feelingguilty. Music has fallen to the side lately, but stand-up comedy is thankfullymore of a hobby so I perform whenever it feels like it’ll be fun.

And being multidisciplinary gives so much space forexperimentation. Sometimes I sneak jokes from my comedy set into my poems (andvice versa). A lot of my songs started as poems.

11 - What kind of writing routine do youtend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I have no routines! I’ve tried every possibletechnique to build some kind of habit around writing, but thanks to my ADHDnothing ever sticks. So I gave up on routine and decided to write whenever Ifeel like it. That might mean once a week, multiple times a day, or even aslittle as once a month. It’s sort of terrifying to accept that I’m unable tokeep a level of productivity that is seen as acceptable – I’ve spent yearsdealing with deep anxiety that I’m not productive or disciplined enough(thanks, capitalism).

After getting my diagnosis I spent a lot of timeresearching how to be productive with ADHD, but then I realized that all ofthose methods were counterintuitive to my natural creative style. I could keepexpending copious amounts of energy trying to be (neurotypically) productiveand STILL not develop ‘healthy’ habits. Instead, I decided to surrender to thechaos and see what happens.

12 - When your writing gets stalled,where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Getting out into the world is the best inspirationfor me. I close the laptop, close the books, and go to a music show, hang outwith friends, or go for a walk. I have a poet friend who operates the same wayand we have a theory that there are ‘reader’ poets and there are ‘experience’poets. In other words there are people who gain more inspiration from sittingand researching and imagining, and there are those of us who have to go out andexperience things and get inspired to copy down (or exaggerate) what weperceive. I’m sure most writers are a mix of the two types, but I tend toreally need to get out of my own head regularly.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Cigarette smoke, lol.

14 - David W. McFadden once said thatbooks come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work,whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Music influences my work quite a bit. Or, at least,listening to music can really help get the writing going. I tend to visualisescenes while listening to music. When I was a kid I always made up music videosto my favourite songs. That turned into imagining stories, poems, etc.

Science is also a pretty neat way to get inspired.One of the first songs I ever wrote was about the law of falling bodies.

15 - What other writers or writings areimportant for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Anne Carson is one of my favourites. I return to herwork quite a bit.

Any and all writing is important to me, though.Sometimes I read a news article and end up writing a poem about it. Or I mightobsess over a comic book as a way to chill out after too much intellectualwork.

16 - What would you like to do that youhaven't yet done?

In writing? I wanna write a novel and a full-lengthscreenplay.

17 - If you could pick any otheroccupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think youwould have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Recently I’ve been working on my career in the filmindustry. I think this is a common story for writers: we supplement our incomethrough various other jobs. Vocationally, writing always calls me back, though.It’s also nice that music and comedy scratch my ‘writing itch’ when I’m notactively working on poetry.

And I think the next occupation I’ll attempt will besomething in the social work or psychology realm.

18 - What made you write, as opposed todoing something else?

In school, people always told me I was good atwriting, and teachers encouraged me. Ironically, people also loved to tell menot to pursue writing as a career since “you can’t make money doing that!” Evencab drivers, upon hearing that I was studying English in university, would say,“So you’re going to be an English teacher?” and when I would answer, “No, awriter,” they would laugh at me.

This friction between what I was good at and what Iwas ‘expected’ to do for money was frustrating but also made me very stubbornabout accomplishing my writing goals.

19 - What was the last great book youread? What was the last great film?

I read No Bad Parts by Richard Schwartz and itwas kinda life-changing.

And I’ve watched a lot of great films recently soit’s hard to choose. I think Aftersun (dir. Charlotte Wells) is amasterpiece, though; I was messed up for a whole week after watching it.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’m writing a manuscript of poems aboutchildfree women. It’s sort of transforming into a book about nonconformity andcognitive dissonance. I’m letting the poems take me where they wanna go…

May 2, 2024

Gabrielle Octavia Rucker, Dereliction

Non-Careerist

tread lightly

everything holds weight

grows wider

through dreamtime

steady coaxing

fuels rotation

each birthing

a cycle

uncalculated

in its avoidance

a vessel

to drive

riding higher )

on repentance

so often

no meaning

assigned

for our sake

a ripple of truth

curling

Ittook a while, but I’m just now getting to Great Lakes poet Gabrielle Octavia Rucker’s full-length poetry debut,

Dereliction

(The Song Cave, 2022), acollection of poems composed in two equal halves that fit together perfectly. Thefirst section/half is the extended sequence “Murmurs,” a poem composed with sucha delicate and light such across nearly fifty pages of short, sharpdeclarations, observations and meditations. The lines are nearly whispered,none of which reduce their force. As she writes, early on: “I’ve been giving tomourning my gifts, / faithfully aiding in deception of self, seeding forgery, /a ritual of fictitious charm thrown against me, stuck / to the nape of the neck,barely visible, little lime green ticks.” Through these pieces, short sketches resonateone per page that thread across the distance, she composes thought as much assilence, an afterlife as much as presence. Further on: “There is no formal, noone familiar body.” The second section, “Dereliction,” offers a gathering ofsome forty pages of self-contained, first person narrative lyrics. There issomething interesting in how the collection generally, and this section,specifically, works to place the narrative itself in context, attempting tofind and place the narrator, the self. “I got older,” she writes, as part of “Practicefor My Birthday,” “I remembered / a lot. Still remember / a lot. Everything /began to make more sense, / less too as the glass dome fell / reflecting offthe distant moving / of the blurry Otherside.” The subtlely of her work isdivine, and I am very much looking forward to seeing what she publishes next.

Ittook a while, but I’m just now getting to Great Lakes poet Gabrielle Octavia Rucker’s full-length poetry debut,

Dereliction

(The Song Cave, 2022), acollection of poems composed in two equal halves that fit together perfectly. Thefirst section/half is the extended sequence “Murmurs,” a poem composed with sucha delicate and light such across nearly fifty pages of short, sharpdeclarations, observations and meditations. The lines are nearly whispered,none of which reduce their force. As she writes, early on: “I’ve been giving tomourning my gifts, / faithfully aiding in deception of self, seeding forgery, /a ritual of fictitious charm thrown against me, stuck / to the nape of the neck,barely visible, little lime green ticks.” Through these pieces, short sketches resonateone per page that thread across the distance, she composes thought as much assilence, an afterlife as much as presence. Further on: “There is no formal, noone familiar body.” The second section, “Dereliction,” offers a gathering ofsome forty pages of self-contained, first person narrative lyrics. There issomething interesting in how the collection generally, and this section,specifically, works to place the narrative itself in context, attempting tofind and place the narrator, the self. “I got older,” she writes, as part of “Practicefor My Birthday,” “I remembered / a lot. Still remember / a lot. Everything /began to make more sense, / less too as the glass dome fell / reflecting offthe distant moving / of the blurry Otherside.” The subtlely of her work isdivine, and I am very much looking forward to seeing what she publishes next.

May 1, 2024

the ottawa small press book fair, spring 2024 edition: June 22, 2024

span-o (the small press action network - ottawa) presents:

the ottawa

small press

book fair

spring 2024

will be held on Saturday, June 22, 2024 at Tom Brown Arena, 141 Bayview Station Road (NOTE NEW LOCATION).

“once upon a time, way way back in October 1994, rob mclennan and James Spyker invented a two-day event called the ottawa small press book fair, and held the first one at the National Archives of Canada...” Spyker moved to Toronto soon after our original event, but the fair continues, thanks in part to the help of generous volunteers, various writers and publishers, and the public for coming out to participate with alla their love and their dollars.

General info:

the ottawa small press book fair

noon to 5pm (opens at 11:00 for exhibitors)

admission free to the public.

$25 for exhibitors, full tables

$12.50 for half-tables

(payable to rob mclennan, c/o 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa ON K1H 7M9; paypal options also available

Note: for the sake of increased demand, we are now offering half tables.

To be included in the exhibitor catalog: please include name of press, address, email, web address, contact person, type of publications, list of publications (with price), if submissions are being considered and any other pertinent info, including upcoming ottawa-area events (if any). Be sure to send by June 3rd if you would like to appear in the exhibitor catalogue.

And hopefully we can still do the pre-fair reading as well! details TBA

BE AWARE: given that the spring 2013 was the first to reach capacity (forcing me to say no to at least half a dozen exhibitors), the fair can’t (unfortunately) fit everyone who wishes to participate. The fair is roughly first-come, first-served, although preference will be given to small publishers over self-published authors (being a “small press fair,” after all).

The fair usually contains exhibitors with poetry books, novels, cookbooks, posters, t-shirts, graphic novels, comic books, magazines, scraps of paper, gum-ball machines with poems, 2x4s with text, etc, including regular appearances by publishers including above/ground press, Bywords.ca , Room 302 Books, Textualis Press, Arc Poetry Magazine , Canthius , The Ottawa Arts Review , The Grunge Papers, Apt. 9, Desert Pets Press, In/Words magazine & press, knife | fork | book, Ottawa Press Gang, Proper Tales Press, 40-Watt Spotlight, Puddles of Sky Press, Invisible Publishing, shreeking violet press, Touch the Donkey , Phafours Press, etc etc etc.

The ottawa small press fair is held twice a year (apart from these pandemic silences), and was founded in 1994 by rob mclennan and James Spyker. Organized/hosted since by rob mclennan.

Come on by and see some of the best of the small press from Ottawa and beyond!

Free things can be mailed for fair distribution to the same address. Unfortunately, we are unable to sell things for publishers who aren’t able to make the event.

Also: please let me know if you are able/willing to poster, move tables or distribute fliers for the event. The more people we all tell, the better the fair!

Contact: rob mclennan at rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com for questions, or to sign up for a table

Oh yes, and the fall fair will be held at the same location on Saturday, November 16, 2024, if you need to know that, also.

April 30, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Matt Rader

Matt Rader

lives with his family in Kelowna, BC. He’s the author of six books of poems, a collection of stories, and a work of auto-theory. He teaches Creative Writing at the University of British Columbia Okanagan. His most recent book is

Fine

(Nightwood Editions 2024).

Matt Rader

lives with his family in Kelowna, BC. He’s the author of six books of poems, a collection of stories, and a work of auto-theory. He teaches Creative Writing at the University of British Columbia Okanagan. His most recent book is

Fine

(Nightwood Editions 2024). 1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book, Miraculous Hours , arrived at my door on my 27th birthday. Later that year, my first child was born. My most recent book, Fine, will launch on April 6, the day before my 46th birthday. That kid from 2005 is now completing 2nd year university. It’s probably too neat an analogy to say that the difference between the two books is an entire childhood and adolescence but the difference between the two books is an entire childhood and adolescence.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

When I was a small kid, Dennis Lee bounced me on his knee while he read poems. I ran away crying. Later, I drew a picture of Shel Silverstein’s “The Bear in the Frigidaire” that I felt was really good. My mum helped me write a haiku about the sea when I was about 8. When I went to university, I thought I might be an illustrator. I took a poetry writing class and my teacher, Patrick Lane, looked like my dad who was a long-haul trucker and later a crane operator. Then I thought I’d be a novelist. Then I thought I’d try social work. Meanwhile I kept taking poetry classes with Lorna Crozier. Eventually, I had no choice but to write poems.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Any one poem or story or essay might start as if from nothing and come into some wholeness within days or weeks. Other poems—and especially books—might take years or even decades. Sometimes I take many notes, sometimes I don’t. Truthfully, it’s impossible to say definitively what time or note-taking really have to do with the work in its “final” form. Even work that appears to arise from nowhere and come out fully formed also seems to be the product of all the prior living and “work.” Research and patience might be like dance-steps practiced over and over until some pattern is embodied and then no longer thought about.

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

This depends entirely on the project. With poems and stories, I typically begin with short pieces that at some point suggest a larger scope. However, I’ve also worked with the bigger project or book in mind from the start. Grant writing and academic life have often required that I articulate a larger project or area of research. I tell my graduate students applying for grants and scholarships that they only need to tell a good story about the project they’re going to work on and then ignore that story while they create the work. Inevitably, the final work always bears an interesting resemblance to that story anyway.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I’ve been involved in organizing literary readings my entire adult life. Nevertheless, I’ve always had an ambivalent feeling about them. What matters to me about a reading is that it is a moment in which people gather to privilege works of the imagination. I can’t honestly say that I enjoy doing readings, but I can say that taking part in a reading as an organizer, audience member, or reader is something that I value, that I think is a good in this world, and that I often find very moving.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Questions are always being replaced with other questions. For a long time, I asked, How do I expand what I think is beautiful? This has many dimensions and is a deeply political question. I’m still living with that question. Before that question came to me, I wondered for many years how I might live in my own body, and then later in the “body” of the Okanagan Valley (Sylix Territory) in British Columbia, where I’ve made my home for 10 years. More recently, I’ve asked myself how I might talk to the people around me. That might sound like a simple question but the terms “I” and “talk” and “the people” and “around” are all fields of profound consideration. Today the question is, Can I tell the truth?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

For me, at their best, writers—and poets in particular—are people who disturb habits of language and story. Literature makes our lives and our use of language strange and new to us and in this way creates a potential for change. Writing is never neutral.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

If by editor we mean anyone who might offer input on a draft, then I find it necessary (which is perhaps different than essential). In this sense, all my work has at a least a couple of “editors.” Language use is a community event. It’s extremely helpful to seek out the guidance of the community.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Don’t fight with pigs. The pigs love it and you get filthy.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to essays to short stories)? What do you see as the appeal?

Stories, essays, and poems all favour different styles of thought. For me, stories privilege narrative. Essays privilege the development of ideas. Poetry privileges sound, image, and graphical representations. Of course, stories can be poetic, essays can tell a story, and poetry can develop an idea, but these areas of privilege are the, for me, the appeal to switching genres. There’s also a productive distinction for me between verse and prose. Because verse privileges changing direction, its relationship to time and idea is often stranger than work in prose.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

For much of the last year, my day has begun with exercise. I write in the margins of my day, as it were.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Relationships. Time. Exercise. My body. Music. Only later books.

13 - What was your last Hallowe'en costume?

Last year, I went as my dad.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I like a good tautology. McFadden was clearly right in the most basic sense—we can only call something a book because we have a previous example of a book to help conceive of what this new object might be. Everything is an influence though. A book is an entangled cultural product; it’s entangled with all other cultural products and all habits of human being including what we perceive as “natural.” One aspect of my work is to become more and more aware of these influences.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Seamus Heaney’s collection Seeing Things. The poems of Louise Glück. These both have strangely enduring holds on me. A list of the other writers and writings would be too long as to be largely meaningless. Garrett Hongo’s poem “The Legend” is something I return to many times a year. Michael Longley’s “The Linen Industry” is sublime.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Get really old.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

A doctor working in an area of functional medicine.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I was better at it than drawing or playing guitar.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Excluding the great books, I re-read on the regular, the last great book of poetry I read was The White Light of Tomorrow by Russell Thornton. The last film to really move me was Celine Song’s Past Lives.

20 - What are you currently working on?

This questionnaire. Now I’m done. Thank you.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;