Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 53

May 19, 2024

Cynthia Marie Hoffman, Exploding Head

It Starts

It starts when you arealone in your room, looking up at the window with pink curtains. You count theedges of the window. Right left top bottom. Vaguely you understand not to lookat the corners where the edges touch. Beyond the window, minnows swarm thecreek, each a slim number 1, tallying each other as they pass. Tick, tick,tick, tick in the dark beneath the eroded tree. The curtains are covered withconstellations of glow-in-the-dark stars because you are not allowed to stickthem on the ceiling. The curtains hide the corners of the window, but you knowthey are there, just as you know the minnows are there in the cool water. Everythingis all right. The pattern of your counting makes a 4. When the light goes out,the stars illuminate two paths converging toward the heavens.

Iwas fascinated to see the carved prose blocks of Madison, Wisconsin poet Cynthia Marie Hoffman’s fourth full-length poetry title (and the first of hers I’ve seen),

Exploding Head

(New York NY: Persea Books, 2024), following

Sightseer

(2011),

Paper Doll Fetus

(2014), and

Call Me When You Want to Talkabout the Tombstones

(2018), all also published through Persea Books. A self-described“OCD memoir in prose poems,” the poems of

Exploding Head

are clean,clear and deliberate, and clustered into four numbered sections. “After sometime,” she writes, to open the poem “Beasts,” “you realized you had to get thebeasts out of the house, so you dragged them by the horns to the farthest cornerof the backyard. Look how they cower at the fence when the sprinkler spits atthem in the summer.” Constructed as a quartet-suite of self-contained andcompressed prose blocks—one stanza per poem, one poem per page—Hoffman’s linesare straight but the narrative is built to bend, counterpointing the perspectivesof the child against that of the mother. In certain ways, the what of herapproach is less interesting than the effects, offering a straightforwardnessthat bleeds almost into a disorientation, before landing utterly elsewhere. “Ifyou stare into the dark hard enough,” she offers, to open the poem “Of Feather,”“something glitters.” There’s almost something of an echo through these of the prose poems of Benjamin Niespodziany, or the short stories of J. Robert Lennon,offering the best of a series of sentences that, for the life of you (and delightfullyso), you could never imagine where each poem might end up. “One day you willfind a body in a grassy ditch near the road,” the poem “Stipulations” begins, “justas you imagined. The trash bag flaps in the wind. But the body won’t belong toanyone, and no one is dead. Thes are your stipulations.” Either way, I thinkyou should be reading the poems of Cynthia Marie Hoffman.

Iwas fascinated to see the carved prose blocks of Madison, Wisconsin poet Cynthia Marie Hoffman’s fourth full-length poetry title (and the first of hers I’ve seen),

Exploding Head

(New York NY: Persea Books, 2024), following

Sightseer

(2011),

Paper Doll Fetus

(2014), and

Call Me When You Want to Talkabout the Tombstones

(2018), all also published through Persea Books. A self-described“OCD memoir in prose poems,” the poems of

Exploding Head

are clean,clear and deliberate, and clustered into four numbered sections. “After sometime,” she writes, to open the poem “Beasts,” “you realized you had to get thebeasts out of the house, so you dragged them by the horns to the farthest cornerof the backyard. Look how they cower at the fence when the sprinkler spits atthem in the summer.” Constructed as a quartet-suite of self-contained andcompressed prose blocks—one stanza per poem, one poem per page—Hoffman’s linesare straight but the narrative is built to bend, counterpointing the perspectivesof the child against that of the mother. In certain ways, the what of herapproach is less interesting than the effects, offering a straightforwardnessthat bleeds almost into a disorientation, before landing utterly elsewhere. “Ifyou stare into the dark hard enough,” she offers, to open the poem “Of Feather,”“something glitters.” There’s almost something of an echo through these of the prose poems of Benjamin Niespodziany, or the short stories of J. Robert Lennon,offering the best of a series of sentences that, for the life of you (and delightfullyso), you could never imagine where each poem might end up. “One day you willfind a body in a grassy ditch near the road,” the poem “Stipulations” begins, “justas you imagined. The trash bag flaps in the wind. But the body won’t belong toanyone, and no one is dead. Thes are your stipulations.” Either way, I thinkyou should be reading the poems of Cynthia Marie Hoffman.May 18, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Melanie Marttila

Melanie Marttila (she/her) is an #actuallyaustitic author-in-progress,writing poetry and tales of hope in the face of adversity. She has been writingsince the age of seven, when she made her first submission to CBC's"Pencil Box." She is a graduate of the University of Windsor’smasters program in English Literature and Creative Writing and her poetry hasappeared in Polar Borealis, Polar Starlight, and Sulphur.Her short fiction has appeared in Pulp Literature, On Spec, PiratingPups, and Home for the Howlidays. She lives and writes in Sudbury,Ontario, in the house where three generations of her family have lived, on thestreet that bears her surname, with her spouse and their dog, Torvi.

1 - How did your first bookchange your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? Howdoes it feel different?

The Art of Floating changed my life by beingmy debut poetry collection. Though I’ve been writing and publishing poetrysince the mid-90s, this is the first time I gathered all my work together andpresented it to the world. That I’m doing this as a middle-aged, late-diagnosedautistic, means that I get to present my poetry and myself to the worldauthentically. So, though most of the work in The Art of Floatingreflects my poetic history over the past 30 years, it's given new freshness andimpact by the poet I am today.

2 - How did you come to poetryfirst, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I started writing poetryseriously during my undergraduate degree at Laurentian University. The campusarts community was self-contained, but vibrant. I was part of the EnglishLiterature Society (now the English Arts Society, which produces the journal Sulphur),and we’d often carpool to the downtown for open mics and community poetryreadings. We’d also host event on campus for the larger community. There wasone memorable poetry slam which pitted students against professors. Guess whowon?

3 - How long does it take tostart any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly,or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their finalshape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I write most days in somerespect. The ideas for individual poems may come quickly, but I tend to be aslow writer, especially since I continue to work full time and struggle withthe effects of masking for the first 51 years of my life. I’ve come to understandthat I’ve been teetering on the edge of burnout for most of my adult life. Ihave to be selective in the open calls and deadlines I work toward and kind tomyself if I fail to meet them.

4 - Where does a poem usuallybegin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into alarger project, or are you working on a "book" from the verybeginning?

Each poem varies. Some strikelike lightning and have to come out allatonce. Others rattle around in my headfor days, weeks, months, or even years. Most poems come out of moments in time,animals I see during my twice-daily dog walks, or ideas that just get stuck inmy head. I’ve only recently thought of writing series on specific themes. As toprojects, well, The Art of Floating took 30 years to come together. Ihope to improve on that in future collections.

5 - Are public readings partof or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoysdoing readings?

I enjoy reading my work, butpeopling tends to exhaust me, so I have to be mindful of my energy andexecutive functioning levels as I go. I often have to recover after a readingor other event. Fortunately, that often involves writing, which continues to bea solace.

6 - Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are youtrying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

My concerns are more personalthan theoretical. For instance, I’m working on a series that revisits my lifein light of my autism diagnosis. How many traumatic events were simply theresult of my neurodivergence? Is forgiveness possible? Is it even necessary? Ofcourse, the inherent unreliability of memory plays into this. Neurosciencetells us that the longer we retain a memory, the more often we access it, themore potential there is for subtle (or not so subtle) changes to the realevents that initially created the memory. Is how I remember an event even closeto how it happened? Does that matter?

7 – What do you see thecurrent role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? Whatdo you think the role of the writer should be?

Every act of writing is aninterpretation of the world the writer lives in, tempered by their frame ofreference. Give a room full of poets the same prompt, and each one of them willwrite a wholly original and individual piece. Though the goal of the writer isto tell the truth but tell it slant, as Emily Dickinson said, it’s the impacton the reader that truly tells the tale. The writer’s role in larger culture isto affect the reader (or auditor) emotionally, and by so doing, to resonatewith the reader’s experience, cause them to reflect, and discover somethingabout themselves. If that goal is achieved, the writer has some measure oflongevity and success, even if it is only with one, or a handful, of readers.

8 - Do you find the process ofworking with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I was surprised to discoverthat I am not precious at all with my poetry. I can be very precious with myprose. The editor’s goal is always to improve the piece and I can see almostinstantly how the poem is improved by following the editor’s suggestions. Ireally enjoyed working with Tanis MacDonald. Mind you, she was my first poetryeditor.

9 - What is the best piece ofadvice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

One of my professors, John Riddell, once said that the writer has to take pains not to make their alphabettoo personal. By that, he meant that you need to keep your writing accessibleto the reader. The author Is only half the equation. The reader completes thework.

10 - What kind of writingroutine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day(for you) begin?

Because I work full time, Ihave to write around the workday. I journal daily, usually during a break. AndI read during lunch. I walk my dog twice a day and keep my eyes open for theraccoon squeezing out from under the garage eaves, or the peregrine stooping fora meal. I watch the clouds, catch sun dogs and pillars and rainbows. I oftencan’t write until the evening, but I always have essential oils diffusing,incense burning, lofi music playing. I need some kind of transitional activity,especially now that I’m working from home, even if it’s just a few minutes ofbreathing or a couple of quick sun salutations. Once the stage is set, I setto.

11 - When your writing getsstalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?

If I’m having trouble with aparticular piece, I’ll switch to something else, whether that’s another poem, acreative non-fiction piece, a short story, or a novel. If nothing seems to beworking, it may be a sign that I’m nearing burnout. I may need to spend sometime daydreaming, freewritng in my journal, going for a walk, or getting out intothe community (though, as an extreme introvert and an autist, that can betricky). You have to find ways to fill your creative well, as Julia Cameronrecommends.

12 - What fragrance remindsyou of home?

Rosemary and wintergreen. Thefirst for home (memory and cooking) and the second for “the bush,” as we callit up here in northeastern Ontario. I’ve found and chewed wintergreen leaves atthe Laurentian Conservation Area.

13 - David W. McFadden oncesaid that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influenceyour work, whether nature, music, science, or visual art?

Some of my poetry isekphrastic, that is inspired by photography or painting. Some has been inspiredby a favourite musical artist, like Kate Bush. I draw on mythology,spirituality, or psychology and science, and often intertwine them for aneclectic interweaving where leptons dance like Sufis, stone yields to sweetrelease of fallen cloud, or tectonic plates come together in self-destructivefrenzy.

14 - What other writers orwritings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

My favourite poets are localwomen poets, Kim Fahner and Vera Constantineau, both former poet laureates ofSudbury, and Margaret Christakos. Kim has recently helped me to expand mypoetic reading to Vanessa Shields (loved Thimbles!), Monica Kidd, andBeth Kope. Outside of poetry, I adore Tanis MacDonald’s Straggle, andanything Farzana Doctor writes. I also have a soft spot for speculative fictionand read everything from Guy Gavriel Kay and Margaret Atwood to Premee Mohamedand AI Jiang.

15 - What would you like to dothat you haven't yet done?

In terms of writing, I’d loveto be recognized with a prestigious award or prize (don’t we all?), get anagent, and bring one of my novels to publication. I’d love to go back toFinland—I was in Helsinki for a week in 2017—and conduct more genealogical research.I’d also like to learn to paddle board.

16 - If you could pick anyother occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do youthink you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I tried (and failed) to pursueboth fine art and music in university before settling on writing. I was ingymnastics and dance when I was a child. But I think the path I did not takewas to go into the biological sciences. I think I’d have been an excellentveterinary technologist. Or a wildlife biologist.

17 - What made you write, asopposed to doing something else?

I started writing in grade 3at the age of 7, inspired by a combination of comics, C.S. Lewis, Susan Cooper,Lloyd Alexander, Madeline l’Engle, and the beautiful storybook created bySiobhan Riddell (then in grade 5) of St. George and the Dragon.

18 - What was the last greatbook you read? What was the last great film?

The last great book I read wasWaubgeshig Rice’s Moon of the Turning Leaves. The last great film was PoorThings.

19 - What are you currentlyworking on?

In terms of poetry, I’mworking on a few things. A series examining my life in light of my autismdiagnosis; a series called Schrodinger’s Animals, in which you have to read thepoem to learn if the animal is alive or dead; a fairytale sisters series; and aseries about croning. I’m hoping to place some of these in journals. I’m toyingwith the idea of incorporating the autism series into a hybrid memoir, workingtitle: the autist’s orrery. I’m also working on a piece of short fiction for ananthology call, reworking another for an open submission period, and workingwith a mentor to get my first novel revised and ready for submission. And, ofcourse, I’m continuing to promote The Art of Floating. There are acouple of projects I’ve had to put on the back burner until some time/spaceopens up in my schedule.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

May 17, 2024

Margaret Christakos, That Audible Slippage

All the rivers movingthrough their

thought processesprobably have

to do with radio &

waking

to its voices – Reportingon the projects

people want to make inthe Edmonton

river valley

& howChristine

asked you to feed thebirds

daily & how none ofyour beloveds

live out here on theprairies

Yet the flow in you with

ease & with

insistence you

hear them (“Feed the Birds”)

I’malways amazed at the absolute wealth of contemporary Canadian writing and poetic thoughtavailable in print, providing an array of Canadian poets working on a wholeother level. To illustrate the point, my deeply-incomplete list of thosebetter-than-best would include poets such as Sylvia Legris [see my review of her latest], Stephen Collis [see my review of his latest], Sandra Ridley [see my review of her latest], Jordan Abel [see my review of one of his recent], Erín Moure [see my review of her latest], Gil McElroy,Phil Hall [see my review of the recent festschrift here], Anne Carson, Dionne Brand, Canisia Lubrin [see my review of her second collection], Lisa Robertson[see my review of one of her recent] and a multitude of so many others, all ofwhom are doing work that are difficult to compare, although echoes, patters andpatterns of influence and conversations can’t help but reveal themselves,naturally. Another of those Canadian poets long working at a far higher levelthan the rest of us is Toronto poet Margaret Christakos, author of therecently-released collection

That Audible Slippage

(Edmonton AB:University of Alberta Press, 2024). The author of more than a dozen full-lengthtitles, Christakos’ That Audible Slippage follows more than a dozen ofher published books over the years, including the recent

Dear Birch,

(Windsor ON: Palimpsest Press, 2021) [see my review of such here],

charger

(Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2020) [see my review of such here],

Space Between Her Lips: The Poetry of Margaret Christakos

(Waterloo ON: Wilfrid LaurierUniversity Press, 2017) [see my review of such here],

Multitudes

(Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2013) [see my review of such here] andWelling (Sudbury, ON: Your Scrivener Press, 2010) [see my review of such here], as well as through thenon-fiction lyric of her remarkable lyric essay/memoir Her Paraphernalia: OnMotherlines, Sex/Blood/Loss & Selfies (Toronto ON: BookThug, 2016) [see my review of such here]. I’ve mentioned before my admiration for Christakos’ability to simultaneously establish something self-contained through work that speaksand relates to her other published works. Within that particular trajectory,the original composition of That Audible Slippage roughly holds to a loosetemporal boundary from her time as writer-in-residence at the University ofAlberta in Edmonton in 2017-18, and there’s something about self-contained “residency”poetry titles I’ve always found intriguing, providing a space and time for adifferent kind of self-contained work. Through this, That Audible Slippagecan be said to follow a string of other poetry titles compositionally specificto poet-in-residence positions, whether Moure hetronym “Eirin Moure” composing

Sheep’sVigil by a Fervent Person

(Toronto ON: Anansi, 2001) out of a University ofToronto residency, George Bowering’s The Concrete Island: Montreal Poems1967-71 (Montreal QC: Vehicule Press, 1977) out of a Sir George Williamsresidency, or even my own University of Alberta writer-in-residence collection,

wild horses

(University of Alberta Press, 2010). Spaces such as theseare very different than the focused time of, say, two or even six weeks at The Banff Centre or three months at Al Purdy’s A-Frame or The Burton House Writer’s Residency, offering the ability to move beyond one’s day-to-day context acrossan extended period, all of which can’t help but provide a different kind of attention,focus and perspective. If we, as writers, are so changed, even if throughcontext, wouldn’t the writing be so as well? As Christakos’ sequence, “Branch,”opens:

I’malways amazed at the absolute wealth of contemporary Canadian writing and poetic thoughtavailable in print, providing an array of Canadian poets working on a wholeother level. To illustrate the point, my deeply-incomplete list of thosebetter-than-best would include poets such as Sylvia Legris [see my review of her latest], Stephen Collis [see my review of his latest], Sandra Ridley [see my review of her latest], Jordan Abel [see my review of one of his recent], Erín Moure [see my review of her latest], Gil McElroy,Phil Hall [see my review of the recent festschrift here], Anne Carson, Dionne Brand, Canisia Lubrin [see my review of her second collection], Lisa Robertson[see my review of one of her recent] and a multitude of so many others, all ofwhom are doing work that are difficult to compare, although echoes, patters andpatterns of influence and conversations can’t help but reveal themselves,naturally. Another of those Canadian poets long working at a far higher levelthan the rest of us is Toronto poet Margaret Christakos, author of therecently-released collection

That Audible Slippage

(Edmonton AB:University of Alberta Press, 2024). The author of more than a dozen full-lengthtitles, Christakos’ That Audible Slippage follows more than a dozen ofher published books over the years, including the recent

Dear Birch,

(Windsor ON: Palimpsest Press, 2021) [see my review of such here],

charger

(Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2020) [see my review of such here],

Space Between Her Lips: The Poetry of Margaret Christakos

(Waterloo ON: Wilfrid LaurierUniversity Press, 2017) [see my review of such here],

Multitudes

(Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2013) [see my review of such here] andWelling (Sudbury, ON: Your Scrivener Press, 2010) [see my review of such here], as well as through thenon-fiction lyric of her remarkable lyric essay/memoir Her Paraphernalia: OnMotherlines, Sex/Blood/Loss & Selfies (Toronto ON: BookThug, 2016) [see my review of such here]. I’ve mentioned before my admiration for Christakos’ability to simultaneously establish something self-contained through work that speaksand relates to her other published works. Within that particular trajectory,the original composition of That Audible Slippage roughly holds to a loosetemporal boundary from her time as writer-in-residence at the University ofAlberta in Edmonton in 2017-18, and there’s something about self-contained “residency”poetry titles I’ve always found intriguing, providing a space and time for adifferent kind of self-contained work. Through this, That Audible Slippagecan be said to follow a string of other poetry titles compositionally specificto poet-in-residence positions, whether Moure hetronym “Eirin Moure” composing

Sheep’sVigil by a Fervent Person

(Toronto ON: Anansi, 2001) out of a University ofToronto residency, George Bowering’s The Concrete Island: Montreal Poems1967-71 (Montreal QC: Vehicule Press, 1977) out of a Sir George Williamsresidency, or even my own University of Alberta writer-in-residence collection,

wild horses

(University of Alberta Press, 2010). Spaces such as theseare very different than the focused time of, say, two or even six weeks at The Banff Centre or three months at Al Purdy’s A-Frame or The Burton House Writer’s Residency, offering the ability to move beyond one’s day-to-day context acrossan extended period, all of which can’t help but provide a different kind of attention,focus and perspective. If we, as writers, are so changed, even if throughcontext, wouldn’t the writing be so as well? As Christakos’ sequence, “Branch,”opens:Voices you cannotremember so

recent present &

scattered into the snowdunes

of what’s become passed

over

Just that audible slippage

so quick so natural

like the motion of winter birds

adhering to each other ina shared tree

to fast arcs of solo flight

Clearlyset in a different landscape (Edmonton, Alberta, over her more familiarToronto, or home territory of Sudbury, written so evocatively through her Welling),Christakos’ poems across That Audible Slippage attend to deep listening:the sights and sounds of light, politics, birds, students, trees, contemporaries,radios and silence itself. The effect is delicate, pointed and polyvocal, andChristakos offers a collage of lyric that weaves across great distances, evenas she catches the smallest moment, such as the poem “Aluminum MachiavellianAllegations,” that includes: “You heard another poet / recently disparatewriting / the personal Let’s all go / global & historical exhume our /little troubles as if the shuddering / volcanic parachute of the future’s /about to rupture Putin / has missiles that can duck & / weave you’ll neverintercept / Putin’s mischief there’s no / point chesting your poker / hand anylonger Lay / it down says Putin Lay / it out [.]” Christakos maintains a lyricthat attends both the landscape and the whole body, simultaneously, and thepoems of That Audible Slippage offers Alberta as less a character orsetting than one piece of a much larger canvas of listening, attending andresponse; a canvas that includes not only the immediately local and intimatebut social media, which is itself can be both intimately immediate andexpansive enough to fall into the abstract. “Honestly you need to access asecond opinion on / matters of the present moment without taking / the time toread over that it is you’re / just not getting anymore,” she writes, as part of“Such Love Alert,” “If you don’t get the GLOBAL ALERT climb on up / to someone’spenthouse & jam for a while / on their solar keyboards with a cold one /& a moist heat in the sedan’s carbon idle [.]”

Composedacross four sections, each of which are themselves composed across extendedsequences—the first section, itself, being a sequence of sequences—there issomething comparable in Christakos’ lines to the stretched-out prairie lyric ofpoets such as Andrew Suknaski or Monty Reid, but one that utilizes fewer pointsalong that horizon to compose that same line. “Was it their echo in rivervalley wind / this blue morning?” she asks, near the opening of the poem “PaperCrowns,” offering, further:

Now, sky fills with largeclouds, white froth

loping in from the east,soaked in colonial sludge

— Vicious words

streaming from white mouthsafter they acquitted

Stanley and, without a shredof disguise,

white jurors fled out thecourt’s back door

police-protected, cowardspanting

for their tiny bombshelter

Hersare lines that hold together as movement stretched—the opposite of skippingstones, a long threaded lyric that tracks not upon surfaces but across depths—andthe large canvas of lyric folded, echoed, stretched and reconnected is one thatis reminiscent of her third collection, The Moment Coming (Toronto ON:ECW Press, 1998), the first of hers I properly encountered, and perhaps whereher sense of the large recombinant and intricately connected lyric expansivenessreally found its footing.

Asearlier collections might have focused the swirls of her collage around family,children, her mother or her Toronto backyard, there is something of thecatch-all to these particular poems, her lines, offering stitched-in breath,meditation, response, witness, contemplation and commentary, akin to the ongoingbricolage of a poet such as Phil Hall. While elements of her prior attentions mightremain, it is the listening itself that becomes the focus, allowing for anythingand everything to fall into the scope of these lyrics. This is a book oflistening. Listen, then, as further in the poem “Aluminum MachiavellianAllegations,” as she writes: “you were so incredibly pompous last / night tothe cab driver who / took forty-five minutes to arrive he said / he’d beenducking & weaving / through the hockey traffic on ice-covered Jasper /besides calling a taxi with groceries / is a double privilege & / laziness& a / crap shoot / A good back-seat driver shuts / the hell up & / tipshigh & you [.]”

May 16, 2024

me and yew and everyone we know : hammersmith + west sussex,

“Whilespending Christmas at a hotel in Lewes in 1910,” Non Morris writes in a blogpost at The Dahlia Papers, “Virginia Woolf declared herself – rathersplendidly – to be ‘violently in favour of a country life’ – and when the leaseon a previous country house was not renewed, the couple were determined to buyMonk’s House.”

Sunday,May 12, 2024: Do you remember the last time Christine and I came this way? [part one here; part two here; part three here of our 2018 trip] Andthis time we brought the kids. We landed 5:30am local time after a six-hour flight into London (out of Montreal, optimistically leaving our car in their lot), where Christine's brother Michael was good enough to collect us from the airport, and we spent most of the day hazy at their wee house in Hammersmith. The kids, of course, were delighted to spend the day with cousins, especially given they hadn't seen them in a while.

Hammersmith: where we do not tell our secrets to the birds, as they whisper to the rats.

Hammersmith: where we do not tell our secrets to the birds, as they whisper to the rats.Hammersmith : where Christine preferred I stop attempting to compose new lyrics to the classic "U Can't Touch This," prompted by my chant of "Hammersmith time!" Please stop that.

Christine and I were able to get a bit of a wander (we didn't want to take the children away from cousins, but inactive in the house would have knocked us both out), landing at The Dove, a curious wee pub with a history that includes "Rule Brittania" being composed within, and visits by Charles II, where he would woo one of his mistresses. It also had the honour of holding the smallest bar-room in the world (according to Guinness), now the second-smallest, after some other establishment somewhere else decided to deliberately build one smaller. Such cheek. Such cheek indeed. At least it is still the smallest in England. A good place, also, to catch the annual Cambridge-Oxford boat race.

Christine and I were able to get a bit of a wander (we didn't want to take the children away from cousins, but inactive in the house would have knocked us both out), landing at The Dove, a curious wee pub with a history that includes "Rule Brittania" being composed within, and visits by Charles II, where he would woo one of his mistresses. It also had the honour of holding the smallest bar-room in the world (according to Guinness), now the second-smallest, after some other establishment somewhere else decided to deliberately build one smaller. Such cheek. Such cheek indeed. At least it is still the smallest in England. A good place, also, to catch the annual Cambridge-Oxford boat race.Ottawa: Didn't you have a Trucker Convoy out your way? asked the waiter. Ah, good, I thought. That's how you know us. We talked about mandates and lockdowns, and how he was in Spain when the Covid curtain fell, and how there were curfews on movement, and residents were barely able to leave their homes.

Hammersmith: where Christine caught a plaque for the printer who created the Dove Type, next to the pub; the type infamously dumped into the Thames and salvaged during contemporary times. The same area where William Morris did his magical business (of which I'm sure you are already full aware).

Monday,May 13, 2024: We made the train for Chichester, south of London, down there in West Sussex, so Christine could begin her two day course at West Dean (where she hadn't been since graduating, nineteen years prior). Her old school-chum Ruth met us at the train, and took us around a few hours of adventuring through the area, which was quite lovely.

Monday,May 13, 2024: We made the train for Chichester, south of London, down there in West Sussex, so Christine could begin her two day course at West Dean (where she hadn't been since graduating, nineteen years prior). Her old school-chum Ruth met us at the train, and took us around a few hours of adventuring through the area, which was quite lovely.

Ruth took us along to Weald & Downland: Living Museum, a medieval gathering of salvaged, restored and relocated medieval buildings from the area into a single village. It really was delightful: a medieval version of Eastern Ontario's Upper Canada Village (where buildings from the 1800s were salvaged, restored and relocated into a single village near Morrisburg), both of which host reenactments by staff and/or volunteers. We saw a blacksmith!There were even a couple of Traveller wagons, which was pretty cool.

Ruth took us along to Weald & Downland: Living Museum, a medieval gathering of salvaged, restored and relocated medieval buildings from the area into a single village. It really was delightful: a medieval version of Eastern Ontario's Upper Canada Village (where buildings from the 1800s were salvaged, restored and relocated into a single village near Morrisburg), both of which host reenactments by staff and/or volunteers. We saw a blacksmith!There were even a couple of Traveller wagons, which was pretty cool. Rose, of course, latched on to a particular Tudor building, presenting herself as some kind of power-mad Tudor Lord of some sort.

Rose, of course, latched on to a particular Tudor building, presenting herself as some kind of power-mad Tudor Lord of some sort. It was curious also to encounter staff/volunteers at the space, all of whom were more than willing to present information on buildings, sites and what-not, almost without prompting. Ruth and I caught a gentleman who was working a lathe he'd built out of logs and branches, showing how tradesmen would make table legs out in the woods, and further, how horses would bring up water for industrial use, including for the creation of a cement known as 'pug,'

It was curious also to encounter staff/volunteers at the space, all of whom were more than willing to present information on buildings, sites and what-not, almost without prompting. Ruth and I caught a gentleman who was working a lathe he'd built out of logs and branches, showing how tradesmen would make table legs out in the woods, and further, how horses would bring up water for industrial use, including for the creation of a cement known as 'pug,'

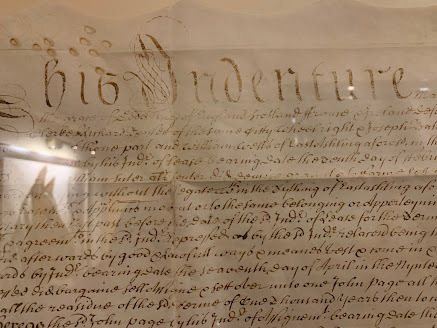

And then a break, for tea and a bitter, at the Horse and Groom, a small pub on the side of the road that was once a farm, and later, housed horses and travellers. The children drew, made a puzzle, relaxed. Christine got some good time with Ruth, as I wandered the building, seeking out what I could. There was a curious document on the wall, which I inquired about, but none of the staff specifically knew what it was, until an older gentleman in the pub said, oh, i know about that, I'm a solicitor! Not knowing my Old English, I wasn't sure what it was or why, but he explained that it was a land deed from the 1700s, explaining all the title from and to whom, and how such a document is considered rather rare now, as most were thrown out after the creation of any subsequent document. And oh, he knows where Ottawa is; his sister was born there! Apparently he was a lawyer for years in West Vancouver. What are the odds?

And then a break, for tea and a bitter, at the Horse and Groom, a small pub on the side of the road that was once a farm, and later, housed horses and travellers. The children drew, made a puzzle, relaxed. Christine got some good time with Ruth, as I wandered the building, seeking out what I could. There was a curious document on the wall, which I inquired about, but none of the staff specifically knew what it was, until an older gentleman in the pub said, oh, i know about that, I'm a solicitor! Not knowing my Old English, I wasn't sure what it was or why, but he explained that it was a land deed from the 1700s, explaining all the title from and to whom, and how such a document is considered rather rare now, as most were thrown out after the creation of any subsequent document. And oh, he knows where Ottawa is; his sister was born there! Apparently he was a lawyer for years in West Vancouver. What are the odds?

Further on, we made for Kingley Vale, a preserved walking trail and Yew trees some hundreds of years old, as well as an ancient burial mound (although weary children meant we never quite made it to the burial mound, which I would have liked to see). The trees looked akin to depictions of trees from Jim Henson, whether Labyrinth or other depictions. I hadn't realized that trees actually had faces. I hadn't realized the reference.

Further on, we made for Kingley Vale, a preserved walking trail and Yew trees some hundreds of years old, as well as an ancient burial mound (although weary children meant we never quite made it to the burial mound, which I would have liked to see). The trees looked akin to depictions of trees from Jim Henson, whether Labyrinth or other depictions. I hadn't realized that trees actually had faces. I hadn't realized the reference. Curious to see all the holly, and holly blossoms.

Curious to see all the holly, and holly blossoms.And from there, Ruth dropped us at our hotel, where the children drooped and I attempted to forage some later dinner from Chichester take-away.

May 15, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Nadine Sander-Green

Nadine Sander-Green grew upin Kimberley, British Columbia. After living across Canada—in Victoria, Torontoand Whitehorse—she now calls Calgary, Alberta, home. She completed her BFA fromthe University of Victoria and her MFA from the University of Guelph. In 2015,Nadine won the PEN Canada New Voices Award for writers under 30. Her writinghas appeared in the Globe and Mail, Grain, Prairie Fire, Outside,carte blanche, Hazlitt and elsewhere.

1 - How did your first bookchange your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? Howdoes it feel different?

Rabbit Rabbit Rabbit is myfirst book. Writing it for the past decade has been the most humbling andgratifying process. I wrote it living in different cities across the country,through marriage and divorce, suffering and healing from a chronic illness,pregnancy and the birth of my first child—this list goes on. Having themanuscript as a project to lean into during the highs and lows of my 20s and30s, was, in retrospect, such a beautiful thing. It was a constant companionduring the good times and propped me up through the hard times.

2 - How did you come to fictionfirst, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I was a journalist first, andthen naturally shifted into essays when I wanted to dig into more creativeprojects. When I finally started to dabble into fiction about ten years ago, Ifelt a great relief and freedom to be able to just…make things up. I find thegenre so much more joyous than non-fiction.

3 - How long does it take tostart any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly,or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their finalshape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I generally write slowly. When Isit down to write, I go back over what I wrote the day before to tinker andedit. That helps me get back in the flow of things and can take up much of thewriting time. By the time I finally get to the end, my draft isn’t too far offfrom a final draft. Sometimes I wish I could write messy and just dive into theheat of the moment, but it doesn’t work like that for me.

4 - Where does a work of proseusually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combininginto a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the verybeginning?

With Rabbit Rabbit Rabbit,I knew it was a book from the very beginning, but many other ideas start andstay as shorter pieces. A work begins with a certain feeling of heat and energyinside of me. I’ve learned to trust that feeling and that it means there isenough substance there to create a story with resonance. If I just go, Oh Iwould like to write about this character or this thing that happened to me, it’snot enough. It falls flat. As wishy-washy as it sounds, I wait for the energyin feeling or theme, and then I start from there and move towards story.

5 - Are public readings part ofor counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoysdoing readings?

I like doing readings. There’s a partof me that enjoys being in the spotlight for a few minutes and entertaining acrowd. I think I’m right on the cusp of the introvert-extrovert continuum, so Ido get nervous for readings and I really only want to be on stage for a coupleminutes, and then I’m happy to hide in the crowd again.

6 - Do you have any theoreticalconcerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answerwith your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I wouldn’t say I’m trying toanswer any specific questions with my work. If I did frame it that way, I suspectit would paralyze my writing process and leave me with nothing on the page.

I do think a lot about who hasthe right to tell what story. These are not new questions, but do I write abouta place—a land and a culture—from where I am not deeply rooted? If I visit orlive in a place but then leave and write about it, am I “taking” stories thataren’t rightfully mine? When I wrote non-fiction, I felt deeply conflictedabout writing about “real people”, and this is partly why I switched tofiction. The freedom in fiction is a relief on multiple levels.

7 – What do you see the currentrole of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do youthink the role of the writer should be?

I think the role of the writer isto cut through the theatrics of our everyday lives; to look deeper and seewhat’s there. Ever since I was a kid, I felt like there was a certain boredomto the daily routine of life. It was only when I started writing as a teenagerwhen I understood that art is medicine for that unfulfilling feeling of solelyliving on the surface of life.

8 - Do you find the process ofworking with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Essential. As a journalist, I gotused to the big, red editors’ marker and understand how helpful it was to havean outside perspective on my work. With my novel, Rabbit Rabbit Rabbit, myeditor took it in directions I would never have thought of on my own.His keen eye made it a far better book.

9 - What is the best piece of adviceyou've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Don’t obsess over renovating yourbody or renovating your home. It’s a never-ending cycle.

This advice isn’t particularlyabout writing, but I do think that if you want to have a deep writing life youhave to put less energy into the more material, physical things of life.

10 - How easy has it been for youto move between genres (short stories to the novel)? What do you see as theappeal?

The hardest leap for me was whenI was much younger and moving from journalism to essays. I was so accustomed towriting short, quippy pieces that it was a challenge to go deeper into a pieceand really let my mind wander. Once I got the hang of that, moving from essaysto fiction was more of a breeze.

11 - What kind of writing routinedo you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you)begin?

When I was writing my novel, I managedto scrape enough money together to work part-time and then could spend a goodchunk of the day writing. I usually wrote for about three hours. Now that Ihave a toddler, my writing life looks much different. When I do find time towrite, it’s in short bursts while my son naps on the weekend, or during lunchhour in my office boardroom. Having a child has helped me be looser with mewriting. I just don’t have time to be precious about it.

12 - When your writing getsstalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?

When I am deep in a writingproject, I find reading books I love to be more of a distraction than aninspiration. I worry that my own voice will start to resemble that of myfavourite writers instead of being authentically my own. Getting outside angoing for a walk helps me immensely. It loosens the agitation and anxiety in mybrain, that stuck feeling, and allows for ideas to flow again.

13 - What was your lastHallowe'en costume?

I haven’t dressed up in years. Asan adult, I have never enjoyed Halloween. There’s something about thesickly-sweet candy and the booze and being forced to find a costume (lastminute, for me) that never sat right with me. I also find Halloween is a timewhere the destructiveness in people comes out and it always puts me on edge.

That being said, I dressed my two-year-oldson up as Einstein last year and it was a hoot.

14 - David W. McFadden once saidthat books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence yourwork, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

The wilderness inspires my workgreatly. I grew up in a very outdoors-y family, and after a brief stintrejecting that lifestyle as a teenager, it’s always been a big part of my life.Living in the Yukon, in particular, defined my relationship with the land,which features prominently in my novel Rabbit Rabbit Rabbit. In my late20s I went on a 16-day canoe trip in northern Yukon. Being immersed in the wildfor that long changed everything from the way I saw myself to how I incorporatenature into my work.

15 - What other writers orwritings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I’ve been really into writerslike Rachel Cusk and Deborah Levy, lately. There’s something so sharp abouttheir work that I deeply admire. They don’t seem to care to stick to any rulesabout genre or style. There is never an explanation or self-deprecation, just adistilled, even steely, view of what it means to be a woman and a writer today.I find their work incredibility refreshing and I hope to be as confident andunapologetic as these two women one day.

16 - What would you like to dothat you haven't yet done?

Learn how to cook steakperfectly. Swim in Greece. Get my son ready for his first day of kindergarten.Adopt a dog. Teach a class at university. Take a long train trip.

17 - If you could pick any otheroccupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think youwould have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I’d like to be a therapist. Iunderstand that dealing with the weight of other people’s problems every daywould be exhausting, but I am just so intrigued by other people’s lives and howthey work through their darkest times. I think it would be deep and meaningfulwork, like writing.

18 - What made you write, asopposed to doing something else?

I was no good at anything else inhigh school, when I was thinking of what I wanted to pursue in university. Tobe honest, I was no good at writing either, but I had an inspiring creativewriting teacher who made me feel like writing was a worthwhile thing to do withyour life. I started my degree in creative writing quite young, at 17, andagain, I really didn’t have the life experience or wisdom to write anythingmeaningful, but it was all practice and I truly believe practice is everything.At some point in my 20s I realized there was nothing quite like the feeling of havingwritten for a few hours, and I have followed that feeling ever since.

19 - What was the last great bookyou read? What was the last great film?

I’m going to go back to Deborah Levy here, and her brilliant memoir The Cost of Living. After goingthrough a divorce, she rents out a shed in an artist friend’s backyard andfinds a new way of living. It’s somehow inspiring and bleak at the same time,which I find true to much of life.

As for films, I’ll jump on thebandwagon and say that Past Lives, from Korean-Canadian filmmaker CelineSong, has stayed with me for a long time. It hits the tone of bittersweet justperfectly.

20 - What are you currentlyworking on?

I have a couple different ideafor novels floating through my head, but I am in the thick of early motherhoodright now and haven’t figured out how to dedicate significant time writing. Ishaped my 20s and early 30s around writing and now the task is to figure outhow to write when it feels like every hour of the day is taken up by thesebeautiful and complicated little people. At the same time, I’m trying to allowmyself to transform as a woman and I understand my artistic practice might lookvery different for the next few years.

May 14, 2024

Lara Glenum, SNOW

LET IT SNOW

A witch baby

I blubber out

into empire’s hooks

I warble out

a curl-i-cue girlsong

Swipe left to abort

my future

Swipe right

& Kerpow

I level up

to a darkbright

mutinous new world

I’mabsolutely fascinated by Louisiana poet Lara Glenum’s latest, the lively insistenceof her full-length collection

SNOW

(Notre Dame IN: Action Books, 2024),following The Hounds of No (Action Books, 2005),

Maximum Gaga

(ActionBooks, 2009),

Pop Corpse!

(Action Books, 2013) and

All Hopped Up OnFleshy Dumdums

(Spork Press, 2013). Composed as grotesque reimagining, allsexy and swagger, of the Snow White tale, the poems of Glenum’s SNOW aregestural, guttural and performative, provocative and large. “Why is femalepleasure such a threat,” she writes, to close the poem “DANCE CARD,” “Darling /You’re really a very dull beast / An insult to leaping animals // A travesty toskipping girls [.]” Glenum’s SNOW offers quite a different approach fromfairy tale reimaginings such as Jessica Q. Stark’s Buffalo Girl(Rochester NY: BOA Editions, 2023) [see my review of such here] or Katie Fowley’sThe Supposed Huntsman (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2021) [see my review of such here], not to mention the array of dozens of poets working far moredelicate variations on other well-known myths and fables. “Mother is bleedingup new crime scenes,” she writes, to open the poem “THE FAIREST OF THEM ALL,” “Herpoisonfingers drawing lethal rings around snapping necks / Mother is toxiclethal contagion / & I’m a corrupt copy / of her ambivalent love [.]” The strengthof any story, so they say, is in its mutability, and Glenum offers a variationon Snow White that is theatrical, pulsed and even staccato; eight sectionsreveling in the performative gesture to the point that such a poetry titlecould be directly adapted for the stage. The poem-sections, also, are almostset as scenes across her book-length performance--“LET IT SNOW,” “MIRROR!MIRROR!,” “PALACE DAYS,” “MIDWINTER BALL,” “THE HUNT’S AFOOT,” “THE POISONLODGE,” “GLASS COFFIN” and “GOODBYE”—each poem within composed as a speakingpart by one of the book’s central characters. As the poem “MOTHER’S LITTLEHELPER” reads:

I’mabsolutely fascinated by Louisiana poet Lara Glenum’s latest, the lively insistenceof her full-length collection

SNOW

(Notre Dame IN: Action Books, 2024),following The Hounds of No (Action Books, 2005),

Maximum Gaga

(ActionBooks, 2009),

Pop Corpse!

(Action Books, 2013) and

All Hopped Up OnFleshy Dumdums

(Spork Press, 2013). Composed as grotesque reimagining, allsexy and swagger, of the Snow White tale, the poems of Glenum’s SNOW aregestural, guttural and performative, provocative and large. “Why is femalepleasure such a threat,” she writes, to close the poem “DANCE CARD,” “Darling /You’re really a very dull beast / An insult to leaping animals // A travesty toskipping girls [.]” Glenum’s SNOW offers quite a different approach fromfairy tale reimaginings such as Jessica Q. Stark’s Buffalo Girl(Rochester NY: BOA Editions, 2023) [see my review of such here] or Katie Fowley’sThe Supposed Huntsman (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2021) [see my review of such here], not to mention the array of dozens of poets working far moredelicate variations on other well-known myths and fables. “Mother is bleedingup new crime scenes,” she writes, to open the poem “THE FAIREST OF THEM ALL,” “Herpoisonfingers drawing lethal rings around snapping necks / Mother is toxiclethal contagion / & I’m a corrupt copy / of her ambivalent love [.]” The strengthof any story, so they say, is in its mutability, and Glenum offers a variationon Snow White that is theatrical, pulsed and even staccato; eight sectionsreveling in the performative gesture to the point that such a poetry titlecould be directly adapted for the stage. The poem-sections, also, are almostset as scenes across her book-length performance--“LET IT SNOW,” “MIRROR!MIRROR!,” “PALACE DAYS,” “MIDWINTER BALL,” “THE HUNT’S AFOOT,” “THE POISONLODGE,” “GLASS COFFIN” and “GOODBYE”—each poem within composed as a speakingpart by one of the book’s central characters. As the poem “MOTHER’S LITTLEHELPER” reads:I’m a doozie

of a wild witch

Kween of the Undermundo I fake out deathstars

with my magyk mirror

Heads roll & pump

sex grease

in tribute to my booty

So I drink the blood ofvirgins

So what

Who doesn’t

That’s patriarchy for you who am I

to claim I’m on the outside

So I’m a bottom-feeder So the heckwhat

Bottom’s up!

canonly mean one thing

when there’s a boot on your neck

Thecharacters are rich, textured and animated, nearly cartoonish in theirdepictions. Curiously, the collection was previously titled, according to herauthor biography via the Poetry Foundation website, “White Trashed: ASnow White Story,” and Glenum offers a pulsing narrative of sexy, savage accumulationsof cosplay and punk, swirling a teenaged Snow White across a propulsive lyricof “wet bone and seeping eros” as she battles the Evil Kween for her verysurvival. This is, after all, a book about agency. Each poem reveals another unfolding of the narrative, akin to a pokerhand, one card at a time, each one playing off the one that came before. “I’mokay I’m loaded,” she writes, to close the poem “PUNK DEBUTANTE,” “with weepinginsects / I can live without medics // or even a home / I’m just a weepinganimal // in dire need of a disco bullet / to my singing skullmeat [.]”

May 13, 2024

Spotlight series #97 : AJ Dolman

The ninety-seventh in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Ottawa poet and editor AJ Dolman

.

The ninety-seventh in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Ottawa poet and editor AJ Dolman

.The first eleven in the series were attached to the Drunken Boat blog, and the series has so far featured poets including Seattle, Washington poet Sarah Mangold, Colborne, Ontario poet Gil McElroy, Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Ottawa poet Jason Christie, Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough, Ottawa poet Amanda Earl, American poet Elizabeth Robinson, American poet Jennifer Kronovet, Ottawa poet Michael Dennis, Vancouver poet Sonnet L’Abbé, Montreal writer Sarah Burgoyne, Fredericton poet Joe Blades, American poet Genève Chao, Northampton MA poet Brittany Billmeyer-Finn, Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer from Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1 territory) poet, critic and editor Joshua Whitehead, American expat/Barcelona poet, editor and publisher Edward Smallfield, Kentucky poet Amelia Martens, Ottawa poet Pearl Pirie, Burlington, Ontario poet Sacha Archer, Washington DC poet Buck Downs, Toronto poet Shannon Bramer, Vancouver poet and editor Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Vancouver poet Geoffrey Nilson, Oakland, California poets and editors Rusty Morrison and Jamie Townsend, Ottawa poet and editor Manahil Bandukwala, Toronto poet and editor Dani Spinosa, Kingston writer and editor Trish Salah, Calgary poet, editor and publisher Kyle Flemmer, Vancouver poet Adrienne Gruber, California poet and editor Susanne Dyckman, Brooklyn poet-filmmaker Stephanie Gray, Vernon, BC poet Kerry Gilbert, South Carolina poet and translator Lindsay Turner, Vancouver poet and editor Adèle Barclay, Thorold, Ontario poet Franco Cortese, Ottawa poet Conyer Clayton, Lawrence, Kansas poet Megan Kaminski, Ottawa poet and fiction writer Frances Boyle, Ithica, NY poet, editor and publisher Marty Cain, New York City poet Amanda Deutch, Iranian-born and Toronto-based writer/translator Khashayar Mohammadi, Mendocino County writer, librarian, and a visual artist Melissa Eleftherion, Ottawa poet and editor Sarah MacDonell, Montreal poet Simina Banu, Canadian-born UK-based artist, writer, and practice-led researcher J. R. Carpenter, Toronto poet MLA Chernoff, Boise, Idaho poet and critic Martin Corless-Smith, Canadian poet and fiction writer Erin Emily Ann Vance, Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi, Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, Canadian poet Peter Jaeger, Birmingham, Alabama poet and editor Alina Stefanescu, Waterloo, Ontario poet Chris Banks, Chicago poet and editor Carrie Olivia Adams, Vancouver poet and editor Danielle Lafrance, Toronto-based poet and literary critic Dale Martin Smith, American poet, scholar and book-maker Genevieve Kaplan, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic ryan fitzpatrick, American poet and editor Carleen Tibbetts, British Columbia poet nathan dueck, Tiohtiá:ke-based sick slick, poet/critic em/ilie kneifel, writer, translator and lecturer Mark Tardi, New Mexico poet Kōan Anne Brink, Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Melanie Dennis Unrau, Vancouver poet, editor and critic Stephen Collis, poet and social justice coach Aja Couchois Duncan, Colorado poet Sara Renee Marshall, Toronto writer Bahar Orang, Ottawa writer Matthew Firth, Victoria poet Saba Pakdel, Winnipeg poet Julian Day, Ottawa poet, writer and performer nina jane drystek, Comox BC poet Jamie Sharpe, Canadian visual artist and poet Laura Kerr, Quebec City-area poet and translator Simon Brown, Ottawa poet Jennifer Baker, Rwandese Canadian Brooklyn-based writer Victoria Mbabazi, Nova Scotia-based poet and facilitator Nanci Lee, Irish-American poet Nathanael O'Reilly, Canadian poet Tom Prime, Regina-based poet and translator Jérôme Melançon, New York-based poet Emmalea Russo, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic Eric Schmaltz, San Francisco poet Maw Shein Win, Toronto-based writer, playwright and editor Daniel Sarah Karasik, Ottawa poet and editor Dessa Bayrock, Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia poet Alice Burdick, poet, writer and editor Jade Wallace, San Francisco-based poet Jennifer Hasegawa, California poet Kyla Houbolt, Toronto poet and editor Emma Rhodes, Canadian-in-Iowa writer Jon Cone, Edmonton/Sicily-based poet, educator, translator, researcher, editor and publisher Adriana Oniță, and California-based poet, scholar and teacher Monica Mody.

The whole series can be found online here .

May 12, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Azad Ashim Sharma

Azad AshimSharma is the director of the87press, poetry editor atthe CLR James Journal, Philosophy and Global Affairs, and a PhDCandidate in English and Humanities at Birkbeck College, University of London.He holds a BA in English and a Post-Graduate Diploma in Critical Theory fromthe University of Sussex as well as an MA in Creative-Critical Writing fromBirkbeck College. He is the author of three poetry collections, most recently, Boiled Owls (Nightboat Books/Out Spoken Press, 2024). He is the recipient of theCaribbean Philosophical Association’s Nicolás Cristóbal Guillén BatistaOutstanding Book Award (2023). He lives in South London. His poetry and essayshave been published widely and internationally, most recently in Wasafiri.

1 - How didyour first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare toyour previous? How does it feel different?

My first book, Against theFrame, initially appeared as a chapbook from Barque Press in 2017 in the UKand consisted of a single sequence of short poems that excavated the colonialwars in Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan in the context of growing Islamophobia inthe ‘liberal’ Global North from the position of a Muslim subject living in‘Brexit Britain’. I was 25 years old when it was released and extracts appearedin zines/online publications from Oakland to Nepal. I read from it in a host ofdifferent spaces and it received a second printing quite quickly after itslaunch. At that time I was very much in the throes of addiction and had sadlyhad to drop out of a Master’s programme at my alma matter, the University ofSussex. I was invited to read in Delhi at a small literature festival in Feb2018. Afterwards, I decided to pull my application to Law School (I was goingto give it all up, the poetry and the drugs and the booze, go on the ‘straightand narrow’ etc), I decided to apply to another MA programme in London and givemyself another chance to live a life of letters. I don’t think I’d’ve done thathad it not been for the small successes that chapbook gave me in terms ofachievement and connection to a reading public that was international yetlocalised, intimate, affecting yet critically sound. Not that any of thosequalities are necessarily mutually exclusive. That chapbook also catalysed myfriendship with Kashif Sharma-Patel, my now closest friend and the head editorof the87press, a publishing company we co-founded in 2018.

A 5th Anniversaryedition of Against the Frame was published in 2022 by Broken SleepBooks. This expanded edition of the original moves dialectically from theinitial critique of white supremacy and imperial war towards a critique ofidentity politics with a Sufi inspired musical-mythopoetic interlude. It isbookended by two critical papers, one by Kashif and another by Lisa Jeschke whotook the collection in its earlier chapbook form to a summer school whererefugees from the Global South were being taught English as a second language.That Lisa took my book directly to the people it sought to express solidaritywith and that they wrote poetry back to me, as part of their many educationalworkshops and activities, remains one of the greatest gifts I’ve ever receivedfrom this life. I’ll be forever grateful for that connection to disparateothers who have suffered more than I could possibly imagine due to my residencein the Global North but with whom I am always in solidarity. Against theFrame may have not won awards or reached thousands of people, but the folksit did reach it registered with. In terms of my small life’s trajectory: it wasworld-making. In similar vein, Kashif’s essay really placed my work in acritical and discursive context, evoking much of our conversations over theyears. I’m really grateful to know my work was read on its terms and respondedtoo. I think that’s the most a writer can hope for, really.

My third collection, for whichI’m currently on tour, is called Boiled Owls and it began in 2017, theyear my first chapbook was released. It charts the trials and tribulations of asubject in the throes of addiction, seeking recovery, relapse, family andradical care. It’s a very different collection both in subject matter and form.But there are similarities in terms of compositional elements, the use oftheoretical and philosophical language as part of the poetic weave, theinsistence on approaching complexity with nuance, the penchant for outbursts ofanger or finding a form for rage in the face of so much death anddestruction. Yet there’s a tightness tothe formal experiments and enjambed lines in Boiled Owls that is perhapsless consistent in both Against the Frame and my second collection Ergastulumwhich was a work of collage between the lyric in its times and the existentialsubject. Above all it feels like Boiled Owls is materially a verydifferent book, it’s published by Nightboat Books in the USA and Out-SpokenPress in the UK. I’m currently on this wild 30 day book tour for it in the USA,ending up with a reading at the largest regular poetry night in Europe, OutSpoken’s series at the Southbank Centre in London. I’m just doing my best tostay grounded and embrace all these new experiences. But that isn’t sodifferent from how I felt in 2017 when my chapbook came out and I travelled,alone for the first time, to Delhi to read at a festival. That my work hasgiven me these opportunitoes, to be on the threshold of new experiences andmake new connections with people and institutions, remains the great wonder ofall of this life in letters. But even as I type this, I’m thinking of how toopen myself to the next challenge the language and the poetry has to offer.

2 - How didyou come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

In truth – I didn’t. I initiallystarted with drawing and painting. My mother would often take me to artgalleries in London and I was fascinated by abstraction, street art, andsurrealism. I first experimented with writing concurrent to my indulgence inart, aged 10-13, with short stories that mimicked the wizards and elves LOTRworld and crossed them with action scenes inspired by my obsession with DragonBall Z. I wrote one in an exam for secondary school and I think a teacherexpressed concern at the descriptions of violence to my mother so I stoppedwriting them. I then progressed to song writing by the age of 14. Poetry onlycame to my life aged 16/17 when I was under the spell of adolescence and allthose embarrassing memories. I became ‘serious’ about poetry during mybachelors at the University of Sussex. The funny thing is, I’m also working ona lot of critical writing (non-fiction) and a novel as part of my PhD. So I’mstill working across forms and learning the ropes of different demands placedon language by them. I guess the poet who made me want to write was John Donnefor, alas, he was the most exciting poet on the syllabus at school during thoseyears. Shakespeare was fun but mechanical when taught for the express purposeof examinations. But as I always tell writers I’m working with or students Iteach through workshops, I was always a reader first – it was readingwhich came to me and helped me address more complexity in the world both realand imagined. Poetry is just the form that the majority of my thoughts thus farhave chosen to take. But that won’t always be the case, I don’t think.

3 - Howlong does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writinginitially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear lookingclose to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Oh it varies so much! BoiledOwls took me six years to write, with many errant tangents explored and alot of editing. It started just as an attempt to help myself make sense of whatI was going through, addiction and the attempts at recovery. Against theFrame was written in 18 months and then expanded five years later in about12 months. Ergastulum was about 12 months of consistent, almost dailyand intense, writing alongside research. My PhD is well into its third year andfast approaching its fourth. I’m due to submit in 2026 which means I’ll havebeen enrolled for about 5 years in total. I’ve an intense few years ahead withthat lined up for sure! All writing is, is just re-writing and editing, findingpeers to help you see things from a different perspective, bibliomancy, thatsort of thing. It’s the great challenge of repetition but also the even greaterchallenge of managing consistency in a fast world by giving yourself the timeto slow down.

In general my research andreading phases don’t often yield copious notes but I do re-read texts multipletimes and find different ways of putting the ideas, as they are represented inlanguage (with new difficult conceptual terms), to use in the line, the clause,the stanza, the poem, etc. Often the poems in their final form look vastlydifferent to their drafts, partly because I only play around with space andtighten the form once I’ve discovered the order of the language or the orderthe language requires. The main techniques I use are automatic writing,collage, and what Keston Sutherland would call a ‘philological poetics’ where Iposition my work, at least in my mind when composing, as in dialogue with otherpoets, philosophers, ideas, discourses.

4 - Wheredoes a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that endup combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book"from the very beginning?

Most of my poems begin intransit – usually on trains or busses and I hastily note down ideas on my phoneor in a notebook if I’m feeling especially whimsical that day. I then usuallyreceive a burst of energy at around 5am the next day and simply have to wake upand go straight to the desk to write, by hand, until I’ve no more to give tothe page. That can yield pieces of varying length but if I know I’m working ona ‘book’ I collate them and play around with ordering, usually under thesupervision of a mentor or editor, before I take a long break from the work andread with fresher eyes. At the moment I’m working on a novel of around 70,000words and a selection of essays totalling 30,000 words. But part of that isalso to prepare, from the essays, talks and shorter essays to explore the ideasI’m grappling with in greater detail and depth. I’m also thinking of my nextcollection of poetry and am writing some drafts, putting ideas and words down,but this is very embryonic at the moment and nothing feels settled or assured. Ido usually think in constellations, looking towards the temporary containerwords like ‘book’, ‘collection’, ‘sequence’, ‘chapter’ seem to give writers.Often it takes the editor I’m working with (or friend) to show me when to‘stop’ the writing as I always flirt over enthusiastically with that boundaryor edge, where the precision sometimes dissipates into something else that istoo much or ‘too far’. My partner is usually my first reader and she’s got thisgreat knack of telling me when I need to start again or focus more because Ican do better; she hasn’t been wrong thus far!

5 - Arepublic readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sortof writer who enjoys doing readings?

I used to enjoy reading fromdraft work regularly to ‘test’ how they felt in the mouth, how they registeredwith an audience, that sort of thing. But these days I prefer not to givepublic readings of drafts and work quietly and more privately until giving aflurry of public readings and then moving on, going quiet again and gettingback to the work and the study. I do enjoy readings when I do them, though.They’re unique ways of meeting readers. Just this week I was at the Universityof Connecticut and I realised that for many of the students in the audience, Iwas the first poet they’d seen read in person. Some members of the audience hadautistic siblings, like me, and it was a wonderful feeling to know the poems inBoiled Owls that do not exceptionalise but explore care-giving as adaily ritual, almost mundane in its challenges, registered with them or madetheir experiences visible in a new way for them. My work is moving into adifferent kind of reading-performance, mostly influenced by the work I see writerslike Nathaniel Mackey, Fred Moten, Bhanu Kapil, and Sophie Seita doing moreregularly. These performances are much more in keeping with the expansive andcross-cultural aspirations of my current work and I hope to perform not onlywith musicians and artists but to also ‘exhibit’ my poetry in art spaces toplay with their reception, or the scene of their reception, in more dynamicways. Yet even as I type that, there’s something quite unique about a poetrynight in its traditional format, a poet clutching onto a book or loose sheavesas if letting go would end their world, a quivering voice, the wit and levitywe all get from that sociality. As long as I am able to, I don’t see a scenarioin which I don’t read my poetry publicly, it’s a public art that also remakesand realigns publics around this unique art form.

6 - Do youhave any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions areyou trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the currentquestions are?

All my writing carries a strongrelationship to various strands of philosophy and critical theory. My debut wasconcerned with both anticolonialism and critical race theory. It’s also a workthat embraces the movement of the dialectic, moving from ‘racialisation’ fromthe ‘exterior’ back to the interiorisation of race as a measure of value, animbibing of the colonial gaze as part of the conscription to epistemiccoloniality, it’s conditioning of writing. Ergastulum, which won a 2023 Guillénaward with the Caribbean Philosophical Association, embraced more temporal andexistential questions proceeding from the loss of touch during the COVID-19pandemic whilst undergirding those explorations with the metaphysical andquantum questions of matter, the body, and a situated perspective on time asduration. I really was inspired by Lewis Gordon’s Freedom, Justice,Decolonization with that book. Boiled Owls also has many concernsthat might be less theoretical than they are based deeply on lived experienceunder capitalism, the contemporary and recent discourses about addiction andrecovery, and a literary concern with how to move beyond the addiction-recoverybinary. A thesis for the book might sound something like this: If capitalismproduced addiction as the emptying out of consciousness into a vessel for thecommodity’s movement in the world, could recovery offer a socialist resistanceto capitalism? I’m not sure the book necessarily answers that question but itpresents that question through the merging of image, biography, research intothe current issue of cocaine abuse in the UK (which is also a current globalissue). It is also a deeply existential phenomenology of addiction, trying topin down what is happening to the human psyche, spirit and soul, during thattrial. I also see some glimmers of utopian gestures that are imbricated inlife’s quotidian mundanity, episodes of family life or a walk in the park takeon new significances in the midst of the collection’s progression. I’m not surewhat will come next in terms of the theoretical concerns with my nextcollection, I’ve not gotten there yet. My novel and critical writing aregenerally concerned with anti-/ colonialism, late-/modernism and contemporaryiterations of the Avant Garde.

7 – What doyou see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they evenhave one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?