Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 52

May 29, 2024

Luke Kennard, Notes on the Sonnets

‘Lo! in theorient when the gracious light’ (7)

Language, although it’snot said so often, is actually brilliant. I mean just look at it. We took toomany pointers from depressed short story writers when really language is sowonderful I can only celebrate it sub-lingually. I’ll rub my wings together orsomething. I’m just going to come right out and say: that’s not a good reasonto have a son. It never even occurred to me. I only want to be temporary custodianof a soul as strange as mine. But I know you’re trying to say something nice. HonestlyI like you and you’re beautiful. If you climb this hill it would make you veryold. Meet my replacement in the world; I think he’s upstairs playing on my phone.I cannot accept the role of head of department because my contract stipulates Iavoid any role which could be described as “Oedipally significant”. In one rooma man stands by the dimmer switch, slowly turning it all the way up then allthe way down repeatedly. Not so much a fantasy as a mistake, and a barely plausibleone at that. Tell him to quit it.

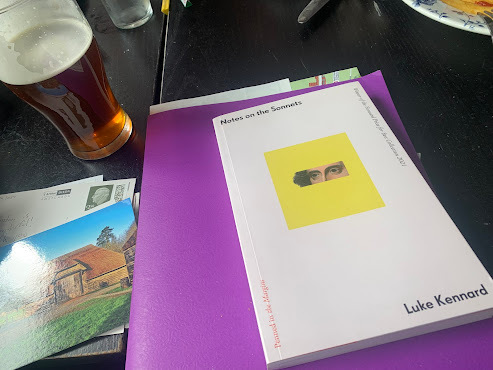

Havingpicked this up recently at a bookstore in Chichester, England, I’m a bit lateto British poet Luke Kennard’s Notes on the Sonnets (London UK: Pennedin the Margins, 2021), a prose-poem suite that each play off a different one ofWilliam Shakespeare’s one hundred and fifty-four sonnets. As the back coveroffers: “Luke Kennard recasts Shakespeare’s 154 sonnets as a series of anarchicprose poems set in the same joyless house party. A physicist explains darkmatter in the kitchen. A crying man is consoled by a Sigmund Freud actionfigure. An out-of-hours doctor sells phials of dark red liquid from a briefcase.Someone takes out a guitar.” There is something quite fascinating about anytext that is able to prompt such a variety of responses, allowing for a fluidityand mutability that even the genius of Shakespeare could never have imagined,and a list of further responses to these sonnets over the past few years alonewould make an impressive (and essential reading) list: Vancouver Island poetand critic Sonnet L’Abbé wonderfully inventive Sonnet’s Shakespeare(Toronto ON: McClelland and Stewart, 2019) [see my review of such here], Manhattan-basedpoet Trevor Ketner’s homolinguistic translation The Wild Hunt Divinations: agrimoire (Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2023) [see my review of such here] and even St. Catharines, Ontario poet and critic Gregory Betts’ morerecent visual epic, BardCode (UK: Penteract Press, 2024).

Havingpicked this up recently at a bookstore in Chichester, England, I’m a bit lateto British poet Luke Kennard’s Notes on the Sonnets (London UK: Pennedin the Margins, 2021), a prose-poem suite that each play off a different one ofWilliam Shakespeare’s one hundred and fifty-four sonnets. As the back coveroffers: “Luke Kennard recasts Shakespeare’s 154 sonnets as a series of anarchicprose poems set in the same joyless house party. A physicist explains darkmatter in the kitchen. A crying man is consoled by a Sigmund Freud actionfigure. An out-of-hours doctor sells phials of dark red liquid from a briefcase.Someone takes out a guitar.” There is something quite fascinating about anytext that is able to prompt such a variety of responses, allowing for a fluidityand mutability that even the genius of Shakespeare could never have imagined,and a list of further responses to these sonnets over the past few years alonewould make an impressive (and essential reading) list: Vancouver Island poetand critic Sonnet L’Abbé wonderfully inventive Sonnet’s Shakespeare(Toronto ON: McClelland and Stewart, 2019) [see my review of such here], Manhattan-basedpoet Trevor Ketner’s homolinguistic translation The Wild Hunt Divinations: agrimoire (Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2023) [see my review of such here] and even St. Catharines, Ontario poet and critic Gregory Betts’ morerecent visual epic, BardCode (UK: Penteract Press, 2024).Thereis a heft and an immense sense of play to this collection, structured nearly asa collection of self-contained pieces that accumulate into something far morecomplex, reminiscent my experiences reading through J. Robert Lennon’s shortstory collection Pieces for the Left Hand (Graywolf Press, 2005) and JoyWilliams’ short story collection 99 Stories of God (Tin House Books,2016) [see my notes on these two here]. The narrative arc of Notes on theSonnets might not fully exist, and yet, it does, even if only in the mindof the reader, seeking out patterns across a wide array of notes, moments, seeming-randomnessand a party that seems endless, captured across more than two hundred pages ofKennard’s deep-thinking prose. If James Joyce could write out a day, why not thissuite of prose poems around a party as well?

May 28, 2024

How many kilometres to London Towne?

“When a man is tired ofLondon, he is tired of life; for there is in London all that life can afford.”Samuel Johnson

[see my report on the first part of our journeys here and the second part here]

[see my report on the first part of our journeys here and the second part here]

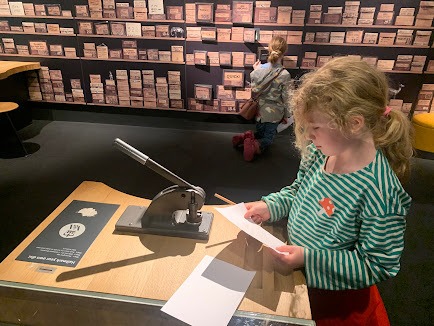

Thursday,May 16, 2024: Back in London, where the young ladies played a bit with their cousins before cousins headed out to school, and the four of us headed to the Victoria and Albert Museum, a space the children were enjoying well enough up to a point, but also barely tolerating. We took the tube, as Aoife offered coins to buskers in the station. Once at the museum, the children were already hungry, so we made for the cafeteria, adorned with an array of stained glass windows. The young ladies were not fully convinced. Rose wanted to go shopping. At least there was a space to press images into paper, as a kind of royal mark, which they young ladies enjoyed.

Thursday,May 16, 2024: Back in London, where the young ladies played a bit with their cousins before cousins headed out to school, and the four of us headed to the Victoria and Albert Museum, a space the children were enjoying well enough up to a point, but also barely tolerating. We took the tube, as Aoife offered coins to buskers in the station. Once at the museum, the children were already hungry, so we made for the cafeteria, adorned with an array of stained glass windows. The young ladies were not fully convinced. Rose wanted to go shopping. At least there was a space to press images into paper, as a kind of royal mark, which they young ladies enjoyed. We moved through some of the metal-work and portraiture, but it was through the jewellery exhibit that their interest was, at least, sparked. I had hoped to get into the photography exhibit from Sir Elton and David's collection, but the young ladies were having none of that. I'm both hoping and presuming it lands at Ottawa at some point (although that could be a few years away, I know).

We moved through some of the metal-work and portraiture, but it was through the jewellery exhibit that their interest was, at least, sparked. I had hoped to get into the photography exhibit from Sir Elton and David's collection, but the young ladies were having none of that. I'm both hoping and presuming it lands at Ottawa at some point (although that could be a few years away, I know). Rose, attempting to replicate a pose.

Rose, attempting to replicate a pose.

I think the longest we spent in the building at all was the gift shop, where I complimented one of the staff on the intricacies of her tattoo, and discovered that she was from Colorado.

I think the longest we spent in the building at all was the gift shop, where I complimented one of the staff on the intricacies of her tattoo, and discovered that she was from Colorado. After the museum, Christine had booked us a nearby 'dinosaur tea,' which doubled as lunch; wishing to introduce the young ladies to that most British of rituals (but dinosaur-themed). There were small cakes and treats shaped like dinosaurs and dinosaur eggs, and dry ice providing a bit of smoke from the plates. They were pleased.

After the museum, Christine had booked us a nearby 'dinosaur tea,' which doubled as lunch; wishing to introduce the young ladies to that most British of rituals (but dinosaur-themed). There were small cakes and treats shaped like dinosaurs and dinosaur eggs, and dry ice providing a bit of smoke from the plates. They were pleased. The cafe sits in a basement corner of The Ampersand Hotel (it was very fancy). On the way to the washrooms was this artwork that I quite liked, "Assemblage" (2012) by Alex Petrescu, although I couldn't find any references for the artist online.

The cafe sits in a basement corner of The Ampersand Hotel (it was very fancy). On the way to the washrooms was this artwork that I quite liked, "Assemblage" (2012) by Alex Petrescu, although I couldn't find any references for the artist online.

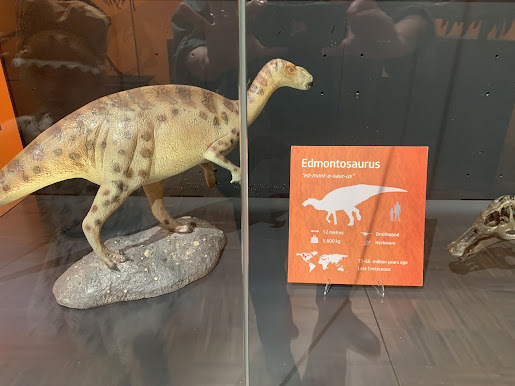

From there, we headed over to the Natural History Museum (although we had hoped to spend far more time in the Victoria and Albert), a space that held an array of constellations upon the wall. I'm always amused to utilize Christine's phone for constellations, the Star Chart app that allows one to see constellations in whichever direction you point the phone, including all the ones that we can't see from North America, on the other side of the earth, such as "Billy the Cowboy," or "Three Bears in a Trenchcoat."

From there, we headed over to the Natural History Museum (although we had hoped to spend far more time in the Victoria and Albert), a space that held an array of constellations upon the wall. I'm always amused to utilize Christine's phone for constellations, the Star Chart app that allows one to see constellations in whichever direction you point the phone, including all the ones that we can't see from North America, on the other side of the earth, such as "Billy the Cowboy," or "Three Bears in a Trenchcoat."

It is interesting to compare some of these other natural history museums in other places, other countries, and be reminded how lucky one has it by being near Canada's Museum of Nature; the one in Chichester was okay, but small; this one is very impressive, offering an array of alternate information, given the different geographical focus [Rose and I visited similar in Washington D.C. in 2015, but she moved too quickly for me to get any useful photos of such]. And it would be impossible to not be blown away by the architecture and scale of the building.

It is interesting to compare some of these other natural history museums in other places, other countries, and be reminded how lucky one has it by being near Canada's Museum of Nature; the one in Chichester was okay, but small; this one is very impressive, offering an array of alternate information, given the different geographical focus [Rose and I visited similar in Washington D.C. in 2015, but she moved too quickly for me to get any useful photos of such]. And it would be impossible to not be blown away by the architecture and scale of the building.

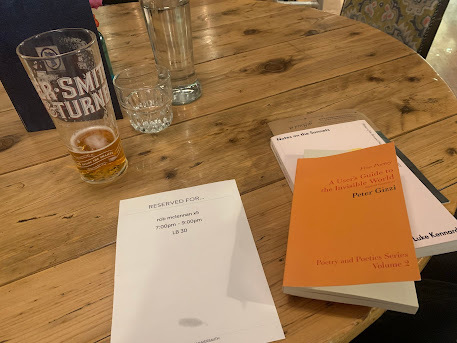

And then back to Hammersmith, where the young ladies spent some good time with their after-school cousins, and I crashed a bit, preparing for the evening. I had been working a couple of weeks attempting a poet-gathering at the pub right by brother-in-law's place, The Queen's Head, but schedules didn't necessarily align with interest. I had booked a table (which was good, as the pub was rather busy), and waited for those who might show (while going further through Luke Kennard's sonnets, and a collection of interviews with American poet Peter Gizzi I'd brought along as well).

And then back to Hammersmith, where the young ladies spent some good time with their after-school cousins, and I crashed a bit, preparing for the evening. I had been working a couple of weeks attempting a poet-gathering at the pub right by brother-in-law's place, The Queen's Head, but schedules didn't necessarily align with interest. I had booked a table (which was good, as the pub was rather busy), and waited for those who might show (while going further through Luke Kennard's sonnets, and a collection of interviews with American poet Peter Gizzi I'd brought along as well). There were a half-dozen local poets unable to make it, with two poets (I only discovered after the fact) that got caught up in other things, but it was great to reconnect with London-based Canadian poet and filmmaker John Stiles (right) after some twenty years, and what was Vancouver poet Sean Cranbury (left) doing in Hammersmith? The last (and only) time I'd seen John Stiles was in 2006, when Stephen Brockwell and I were in London touring around, and I attempted another gathering of poets: a evening quartet at a pub that included myself and Brockwell with London-based Stiles and Kim Morrissey, a writer/poet originally from Saskatchewan [see my notes on such here]; As for Sean, apparently he was at a hotel only a couple of blocks away, his wife, the writer Carleigh Baker informing him, I think rob is close to where you are and inviting poets for drinks? So random. It was a very nice evening: both Sean and John discussed their admiration for Alberta band The Smalls, and Sean was deeply impressed to discover that John had done a documentary on the band. John stayed for an hour or two, but Sean and I closed the place (which at this location is still the 11pm bell, in case you were wondering).

There were a half-dozen local poets unable to make it, with two poets (I only discovered after the fact) that got caught up in other things, but it was great to reconnect with London-based Canadian poet and filmmaker John Stiles (right) after some twenty years, and what was Vancouver poet Sean Cranbury (left) doing in Hammersmith? The last (and only) time I'd seen John Stiles was in 2006, when Stephen Brockwell and I were in London touring around, and I attempted another gathering of poets: a evening quartet at a pub that included myself and Brockwell with London-based Stiles and Kim Morrissey, a writer/poet originally from Saskatchewan [see my notes on such here]; As for Sean, apparently he was at a hotel only a couple of blocks away, his wife, the writer Carleigh Baker informing him, I think rob is close to where you are and inviting poets for drinks? So random. It was a very nice evening: both Sean and John discussed their admiration for Alberta band The Smalls, and Sean was deeply impressed to discover that John had done a documentary on the band. John stayed for an hour or two, but Sean and I closed the place (which at this location is still the 11pm bell, in case you were wondering).

Friday,May 17, 2024: We woke for further adventuring, aiming ourselves for one of those double-decker bus tour things of get-on, get-off, taking the tube near Buckingham Palace. It took a while for an accumulated grouping of us to actually land a bus, as the stop by where we landed was out of service, and nothing was properly marked (and the guy selling tickets didn't seem terribly interested in helping properly).

Friday,May 17, 2024: We woke for further adventuring, aiming ourselves for one of those double-decker bus tour things of get-on, get-off, taking the tube near Buckingham Palace. It took a while for an accumulated grouping of us to actually land a bus, as the stop by where we landed was out of service, and nothing was properly marked (and the guy selling tickets didn't seem terribly interested in helping properly).

But we rolled around for a bit, listening to bits of historical patter and buildings and sites and such (Hyde Park, for example), until Christine had us jump off at Hamley's, a seven-floor toyshop that she herself had visited as a child on family trips. Oh, there was much excitement. A whole floor of just Lego! A wing dedicated to Peppa Pig. British-specific Playmobile figures available only at this particular store, this particular location.

But we rolled around for a bit, listening to bits of historical patter and buildings and sites and such (Hyde Park, for example), until Christine had us jump off at Hamley's, a seven-floor toyshop that she herself had visited as a child on family trips. Oh, there was much excitement. A whole floor of just Lego! A wing dedicated to Peppa Pig. British-specific Playmobile figures available only at this particular store, this particular location.One of the twentysomething staff complimented my sunglasses, and I told him that I had picked them up from Corner Brook, Newfoundland; he said he was uncultured, and didn't know where that was (my fault, honestly). It reminded of Sean Cranbury responding to a British cab driver who asked where he was from, and the driver asking if Vancouver was in Norway? I am Greb, the young employee said, I am from Lithuania. We ended up in a conversation about sunglasses, one longer than you might imagine, really. Rose said he was only trying to sell me something (which he was not; we were literally discussing sunglasses).

Well, we couldn't stay in the toystore forever (and yes, some items were purchased), so we made for the bus again, attempting to loop around to Tower Bridge and the Tower of London [remember that other time we went through there?], before an attempt for a boat back to Westminster. Sean Cranbury sent a text offering that there was some kind of small publisher's fair happening at the Tate (and I had been hoping to get back to the Tate, especially after missing the David Hockney stuff the last time around), but there simply wasn't the time in the day (had I only known prior!). Sean only found out because he was literally at the Tate watching them set up, but didn't wish to hang around for the extra two hours or so before the event would have been open for the public. It would have been much fun to run through a London book fair, mainly to be able to meet so many folk in person for the first time. And apparently our tour-bus went by the building (and rooftop) where the Beatles played their final live show? (I wasn't able to determine which rooftop)

Well, we couldn't stay in the toystore forever (and yes, some items were purchased), so we made for the bus again, attempting to loop around to Tower Bridge and the Tower of London [remember that other time we went through there?], before an attempt for a boat back to Westminster. Sean Cranbury sent a text offering that there was some kind of small publisher's fair happening at the Tate (and I had been hoping to get back to the Tate, especially after missing the David Hockney stuff the last time around), but there simply wasn't the time in the day (had I only known prior!). Sean only found out because he was literally at the Tate watching them set up, but didn't wish to hang around for the extra two hours or so before the event would have been open for the public. It would have been much fun to run through a London book fair, mainly to be able to meet so many folk in person for the first time. And apparently our tour-bus went by the building (and rooftop) where the Beatles played their final live show? (I wasn't able to determine which rooftop)

The Tower of London: it was interesting to move through this space a second time, catching elements I hadn't seen prior, especially when one is following the moods and interests of young children. During our prior visit, I think we were focusing more on the overview, including around the Tower itself, and Anne Boleyn. I followed Rose through a thread of corridors and towers, watching her catch (three times, on a loop) a short video history around Edward I, "the hammer of the Scots," and attempting to explain to her exactly what that entailed. Some of us might not have been in North America but for some of those histories; decisions that I attempted to let her know directly impacted certain threads of her genealogy. She does seem to have an interest in British history, which is interesting to watch (we spent a year or two watching

Time Team

, as you know; and I think she's done at least one school project on British Royals, including Elizabeth I). The young ladies attended to the ravens (at a distance), and admired the grounds. We went to see the Crown Jewels, Christine grimacing at the imperfect placement of the letters in the signage for same (some shoddy workmanship, there, Tower of London sign-folk).

The Tower of London: it was interesting to move through this space a second time, catching elements I hadn't seen prior, especially when one is following the moods and interests of young children. During our prior visit, I think we were focusing more on the overview, including around the Tower itself, and Anne Boleyn. I followed Rose through a thread of corridors and towers, watching her catch (three times, on a loop) a short video history around Edward I, "the hammer of the Scots," and attempting to explain to her exactly what that entailed. Some of us might not have been in North America but for some of those histories; decisions that I attempted to let her know directly impacted certain threads of her genealogy. She does seem to have an interest in British history, which is interesting to watch (we spent a year or two watching

Time Team

, as you know; and I think she's done at least one school project on British Royals, including Elizabeth I). The young ladies attended to the ravens (at a distance), and admired the grounds. We went to see the Crown Jewels, Christine grimacing at the imperfect placement of the letters in the signage for same (some shoddy workmanship, there, Tower of London sign-folk).

My question: why were the puppets in the gift shop SCREAMING?

My question: why were the puppets in the gift shop SCREAMING?

From there, we caught one of the tour-boats on the Thames, wandering slowly across the water to the perpetual banter of the First Mate, who claimed not to be a tour guide, but there for our safety. He was pretty entertaining, but there was a part of me that wondered if they put him on the microphone to keep him out of trouble. He informed that many asked how to keep straight Tower Bridge from London Bridge, as people were always confusing the two. He suggested that Tower Bridge is the bridge with TWO TOWERS ON IT, and London Bridge was the bridge that said, in big letters upon the side, LONDON BRIDGE. I think that clears all that up, certainly. He also pointed out a spa at our eye level underneath one of those bridges where patrons might occasionally forget that tour boats go by, and we might see some nakedness. He had us all wave in that direction. At least one person sitting in the spa waved back.

From there, we caught one of the tour-boats on the Thames, wandering slowly across the water to the perpetual banter of the First Mate, who claimed not to be a tour guide, but there for our safety. He was pretty entertaining, but there was a part of me that wondered if they put him on the microphone to keep him out of trouble. He informed that many asked how to keep straight Tower Bridge from London Bridge, as people were always confusing the two. He suggested that Tower Bridge is the bridge with TWO TOWERS ON IT, and London Bridge was the bridge that said, in big letters upon the side, LONDON BRIDGE. I think that clears all that up, certainly. He also pointed out a spa at our eye level underneath one of those bridges where patrons might occasionally forget that tour boats go by, and we might see some nakedness. He had us all wave in that direction. At least one person sitting in the spa waved back. I also pointed out, to Rose, the London Eye, something we'd seen more than a couple of times across Doctor Who episodes. And did you know there's an Egyptian Obelisk along the Thames? Cleopatra's Needle, although the way the First Mate spoke, it was three thousand years old, as though it had been there since then, but apparently it was moved by the Victorians, in that way Victorians had of picking up items from other places and attempting to absorb as their own (apparently there's also one in New York). Hm.

I also pointed out, to Rose, the London Eye, something we'd seen more than a couple of times across Doctor Who episodes. And did you know there's an Egyptian Obelisk along the Thames? Cleopatra's Needle, although the way the First Mate spoke, it was three thousand years old, as though it had been there since then, but apparently it was moved by the Victorians, in that way Victorians had of picking up items from other places and attempting to absorb as their own (apparently there's also one in New York). Hm. Given Sean Cranbury was still in town, we met up at the pub again, he and I. Once the children (who were playing with their cousins) were settled, Christine came along for a drink as well, which was nice (her energies, especially by mid/late afternoons, doesn't always allow for such). As well, before either of them landed, I ended up in a conversation with one of the staff, who looked barely twenty, discovering that this very British-sounding young lady had parents who are both Canadian? Apparently they'd moved here before she was born, one from Montreal and the other from Toronto. She says she has cousins in Dorval (hey, that's where our car is!), Pointe-Claire and Banff. You should go to Banff, I said. It's lovely.

Given Sean Cranbury was still in town, we met up at the pub again, he and I. Once the children (who were playing with their cousins) were settled, Christine came along for a drink as well, which was nice (her energies, especially by mid/late afternoons, doesn't always allow for such). As well, before either of them landed, I ended up in a conversation with one of the staff, who looked barely twenty, discovering that this very British-sounding young lady had parents who are both Canadian? Apparently they'd moved here before she was born, one from Montreal and the other from Toronto. She says she has cousins in Dorval (hey, that's where our car is!), Pointe-Claire and Banff. You should go to Banff, I said. It's lovely. Saturday,May 18, 2024: We had to be up enough to be at the airport for 6am, which was miserable (we spent much of the afternoon prior, post-touristing and pre-drinks, packing ourselves and the young ladies), with brother-in-law Mike good enough to drive us to the airport. Half-way there, a text message saying our flight delayed five hours, so we turned right around and I went back to sleep. On our second attempt, we made it, and, thanks to father-in-law, a bit of time in the Air Canada Lounge (the young ladies going through the ridiculous magazines Christine had let them purchase at the shop in the train station). Just like the flight to London, both children refused sleep, watching as many movies as they could (with at least one if not both doing a re-watch of Mean Girls), before Rose actually crashed for a third of the flight. Six hour flight, five hours delayed. And once landed, back to our car in the parking lot (safe, but the windows coated in dust) and the two-hour drive back to Ottawa, as both children crashed rather immediately. They only woke once I had opened the doors in our driveway, and informed them that I'd picked up take-out (a happy meal for Rose, a&w for Aoife), completely unaware that I'd dropped their mother in the Beechwood area for a work-friend potluck she'd been hoping to get to.

Saturday,May 18, 2024: We had to be up enough to be at the airport for 6am, which was miserable (we spent much of the afternoon prior, post-touristing and pre-drinks, packing ourselves and the young ladies), with brother-in-law Mike good enough to drive us to the airport. Half-way there, a text message saying our flight delayed five hours, so we turned right around and I went back to sleep. On our second attempt, we made it, and, thanks to father-in-law, a bit of time in the Air Canada Lounge (the young ladies going through the ridiculous magazines Christine had let them purchase at the shop in the train station). Just like the flight to London, both children refused sleep, watching as many movies as they could (with at least one if not both doing a re-watch of Mean Girls), before Rose actually crashed for a third of the flight. Six hour flight, five hours delayed. And once landed, back to our car in the parking lot (safe, but the windows coated in dust) and the two-hour drive back to Ottawa, as both children crashed rather immediately. They only woke once I had opened the doors in our driveway, and informed them that I'd picked up take-out (a happy meal for Rose, a&w for Aoife), completely unaware that I'd dropped their mother in the Beechwood area for a work-friend potluck she'd been hoping to get to.  I think it took at least three or four days for our sleep to settle. But at least school-mornings were easier on everyone.

I think it took at least three or four days for our sleep to settle. But at least school-mornings were easier on everyone.

May 27, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jess Taylor

Jess Taylor [photo credit: Angela Lewis] is a Tkaronto (Toronto) writer and poet. She is theauthor of Pauls, the title story of which won the 2013 Gold FictionNational Magazine Award, and Just Pervs, a finalist for the 2020 LambdaLiterary Award in Bisexual Fiction. Her story, “Two Sex Addicts Fall in Love,”was longlisted for the 2018 Journey Prize. Play is her debut novel.

1 -How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent workcompare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Pauls, aninterconnected book of short stories, changed my life in a lot of ways. Havinga book out gave me legitimacy that hadn’t been there before, especially beingso young. I’d struggled financially before the book came out, and I stronglybelieve that having a published book helped me get more courses to teach, whichgave me some financial stability that I needed.

Play, mydebut novel that’s coming out in April [ed. note: this interview wasconducted in March 2024], was extremely difficult to write in comparison to Pauls.Structurally, it’s a lot more complex and a bit darker. This time around,though, it’s my third book, so I feel a lot more self-assured and less nervousabout its publication.

2 -How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

Iactually write all three and had a couple of poetry chapbooks published (AndThen Everyone… by Picture Window Press in 2013 and Never Stop byAnstruther Press in 2014) before my first story collection came out. I alwayssay that I’ve been writing seriously since I was a kid, as I started to submitto local contests at the age of 12. Although I was writing stacks of poetry atthe time, one of the first prizes I won was for a short story. I feel like thathelped fuel my confidence in writing stories. Over the years, I’ve gravitatedtoward fiction a little more.

Oneof my favourite things about writing fiction is that it allows me to slip intoother perspectives and characters. While occasionally I’ll write poetry as acharacter, my poetry more typically has a confessional, lyrical element whereif the speaker is not myself, they are at least close to how I see the world.With fiction, it’s easier for me to invent complete people who think, feel, andperceive differently than I do.

3 -How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does yourwriting initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appearlooking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copiousnotes?

Usually,I’ll have an idea or line first that gives me the sense of a character. Next, Ineed to have some idea of a structure. If the voice is really strong, I mightstart to follow the voice of the character and see where it takes me, or if thestory is based on an idea, I might need to let its energy and shape sit withinme before I approach an actual draft. During that time, I might write bits andpieces, but I’m not approaching it with a strong sense of direction. Instead,it’s exploratory. For me, along with character, feeling is central to my work.So I need to also be chasing a feeling or have a particular vibe for a writingproject.

Thelength of time a piece of writing takes depends on the project. My debut novel,Play, took me close to 10 years from the idea to publication, but it wasa very difficult project structurally. The book has taken many different formsover the years before I finally got it into the shape it is now. I also workedwith a developmental editor, Meg Storey, as I was struggling with finding theright structure. Play also has really heavy subject matter and I wantedto make sure that I was getting it right, not over-sensationalizing trauma. Ithink for me to do it well, I needed to give myself time to mature. I felt thatwhile writing and trusted myself. I’m happy I didn’t push it out into the worldwithout giving the book time to develop the way that it needed to so that itcould be sensitive and thoughtful.

Ijust finished writing a solid draft of my second novel, and that book came tome while I was struggling with post-partum anxiety after the birth of mydaughter. All of a sudden I had the voice of a character and with the charactercame this whole family, and I understood the family deeply without doing anyexploratory work. It felt like I’d plucked them from the air. I started towrite the book with naps and after about six months I plotted out Act 1 andthen after another month, the remaining acts. From start to finish, that booktook me two and half years, and that was with working full time and parentingin between. Probably it’ll be another year before it's ready for a publisherand then the process from there will be up to a publisher, but I think fouryears instead of 10 is awesome!

Iknow the next book could take another ten years though, and I’m okay with that,as it’s about putting the best work possible into the world and serving boththe book and my audience in the best way I can. That can take time.

4 -Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of shortpieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

Alot of the time I begin with a character. For my themed collections, I findthat I’ll work on stories for a bit and then start to see if there is acohesive pattern after about four stories or so. If I can find a pattern, thenI know what the project is and I’ll only include stories that fit the projectso that I can have a book of stories that feels like a cohesive book. I likehaving my collections feel like the stories work together – It’s interesting tome.

Fornovels, sometimes the grain might begin in a short story and sometimes, justfrom the scope, I can tell it’ll be a novel. That was the case with the novel Irecently wrote, where as soon as I knew about this family, I was like, “Okaythis is a novel and also there will be UFOs in it.” Haha.

For Play,it came out of the stories in Pauls. Paul (Paulina) is a character inthree stories in the collection, and in “We Want Impossible Things,” she hintsat a troubled past that she will not talk about. She was an interestingcharacter for me because I’m an oversharer and am a little too straightforward,whereas Paul side-steps a lot in conversations and has a hard time trusting. Icould relate to her pain, her shame, and her distrust, but our communicationstyles are different. I wondered, what would healing look like for this person?Would that type of communication, of hiding through communication, would itever get blown open? Would she ever talk about her past? So I wrote into that,and it became Play.

5 -Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you thesort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I doenjoy readings and see it as part of the work of being a writer. For me, it’sanother art form, and although it’s nerve-wracking, I like performing. Forshort stories, I find doing readings extremely helpful for a creative project,as when you’re halfway to three-quarters of the way through a reading,sometimes you can feel a real click moment where you feel in sync with theaudience and you know they are listening; you have their attention. Then youknow it’s a good story and one to keep in a collection. Other times, you canfeel where you lose them or where their attention wavers. You might also havemoments where you’re reading something and are like, Wow this is awful, butI didn’t know until I read this embarrassing line in front of someone else.That can help with cuts and edits.

Ihaven’t read too many novel excerpts aloud and find I usually default toreading a piece at the beginning. I think when I do my readings for Play,I am going to try to experiment with excerpts from different parts and see howit goes!

6 -Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds ofquestions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think thecurrent questions are?

Ithink a lot of the questions I have are about the ways people relate to eachother. Throughout my life, I have often been perplexed by human behaviour: Whyare people not truthful? Why do people hurt each other? Why do peoplecommunicate in different ways? So I write to try to make sense of thesequestions.

I’malso interested in how different people perceive the world. My favourite booksare ones where a character’s perception of the world colours the entire book. Iam trying to add books into the world that do that as well.

Ialso want to know why do we consider some things taboo and not others. Wheredoes shame come from and how can we undo it? I think over time, I’ve come tobelieve that shame comes from feeling that your experiences are unspeakable, soI see writing as a way to unravel shame.

7 –What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do theyeven have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Ithink it’s the writer’s job to shine a light on society and to give words tothe things that are hard to articulate.

8 -Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult oressential (or both)?

Ireally love it! I think it can feel a little vulnerable, especially if you havedoubts about the project. Still, one thing I tell people when I give themfeedback is that I wouldn’t spend time or go in-depth on something unless Irespected the writer, so I try to receive feedback with that attitude as well.I think having someone who doesn’t live inside my head give me feedback on aproject is essential. Both the developmental editor I worked with Meg Storey,and Bookhug’s editor Linda Pruessen gave so much to Play. It reallywouldn’t have managed to be the book it is without them.

9 -What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

WhenI became a parent, someone once told me that everything is a phase so that whenyou’re experiencing a particular challenge, you might feel like you need tofight fight fight to fix whatever the issue is at the time, and then two weekslater, everything is different. There are new problems, but that old problemhas blown over. I think that can be extended to life in general. I tend tosweat every little thing and expect things to get to an objective level of“good”, but really with art, parenting, work, and everything, the hard stuffpasses, the good stuff passes, and you just have to go with it and ride it out.

10 -How easy has it been for you to move between genres (short stories to the novelto picture books)? What do you see as the appeal?

Ilove moving between genres. I get bored easily, so one of my procrastinationhacks is to always have a bunch of projects on the go so that when I get boredor stuck on one, I can work on something else. Multiple genres keep things evenmore fresh,

11 -What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? Howdoes a typical day (for you) begin?

I’mtrying to be a little more consistent this year, as typically I work more inbinges since working full-time. Parenting definitely throws a wrench in theworks (a cute, joy-inducing wrench), so I have very few slivers of time:Tuesday and Thursday mornings between 8 and 9 a.m., time on work lunches, andafter toddler bedtime. So that’s my time for writing, crafts, reading, andcleaning (yeah right). So basically whatever my priorities are, I use thosescraps of time toward that. Lately, I’ve been trying to write daily pages,whether they are reflections or snippets of books so that I’m writing eachday.

12 -When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of abetter word) inspiration?

Whenthings get stalled, I now see it as a sign to rest and fill my experience bank.You can’t write without any experiences, so it’s important to find ways to bepresent and recharge. I craft a lot and find doing things with my hands is agood balance for my writing. I also think that it allows me to still takecreative risks, which then builds creative confidence.

13 -What fragrance reminds you of home?

Afterit rains and you’re in a forest and kick leaves and you can smell the wet soilunderneath in the air.

14 -David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any otherforms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Ithink every art form I come across influences my work. Even watching a showlike Chef’s Table, I’ll be inspired by how the chefs see the world and theircraft. Visual art is a big one, as visual art has always been a big part of mylife.

15 -What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your lifeoutside of your work?

Ihave some writers that I collaborate with and who read my work. Sofia Mostaghimi has been a big one. In recent years, Catriona Wright has become oneof my main beta readers, and I love her work so much. I find her a reallyinteresting writer as she publishes in both fiction and poetry.

Thework of Elif Batuman is also really important to me, as I think it opened upsome stylistic possibilities that I hadn’t thought about before.

16 -What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Inlife or in writing? In writing, putting out a book of non-fiction or a book ofpoetry.

Inlife, um, EVERYTHING. My biggest hurdle is that I want to do too much. I haveso many dreams.

17 -If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or,alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been awriter?

Iactually want to go back to school to be an occupational therapist but willcontinue to write books.

Ifwriting had not been part of my life, I would have focused on the sciences andgone into wildlife biology and conservation.

18 -What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

That’sa really interesting question, especially since I’m drawn to so many art forms.In my youth, I saw other art forms (like songwriting and art) as a way to buildon my writing. I went to an arts high school, and even in the audition forvisual arts, I told them, “I want to be a writer and I think visual arts willhelp me describe the world.” I’m not sure what made writing capture me. Ireally loved books and stories, and, like many, found friendship and escapewithin them. I also was drawn to the stories of my family: tales my parentswould tell me about their lives and the people they knew. In some ways, Ibecame the storykeeper of the family as a child, which is funny now because Ihave no interest in family lore and my brother is meticulously cataloguing itand is now the family historian.

Mybrother also gave me a lot of encouragement to focus on writing as my art formas well. We were six and seven and working on comic books in the backyard, andI moaned about how much better his cartoons were. He told me, “But what you’regreat at is the stories.” He gave me the same feedback as a songwriter when wewere in a band together. He always saw my writing ability as my biggeststrength, and as my first artistic collaborator, I took his opinion veryseriously.

19 -What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Thelast book that wowed me was probably Ripe by Sarah Rose Etter. I’m stillthinking about that book, and it did so many interesting things stylistically.For film, I really loved Everything Everywhere All At Once.

20 -What are you currently working on?

Ijust finished a good draft of my second novel, Experiencer. I also havea story about my obsession with beads gathering in fragments and thoughts. I’malways working on way too many projects until I focus, so I also have anon-fiction manuscript about my abdomen; a long poem about the month of July;and a weird book of stories coming into existence slowly.

May 26, 2024

Adam Clay, Circle Back: poems

My review of Southern Mississippi poet, editor and critic Adam Clay's latest,

Circle Back: poems

(Minneapolis MN: Milkweed Editions,2024), is now online at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics. You can see my review of his prior collection,

To Make Room for the Sea

(Milkweed Editions, 2020), here.

My review of Southern Mississippi poet, editor and critic Adam Clay's latest,

Circle Back: poems

(Minneapolis MN: Milkweed Editions,2024), is now online at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics. You can see my review of his prior collection,

To Make Room for the Sea

(Milkweed Editions, 2020), here.

May 25, 2024

Dawn Macdonald, Northerny

A BORING POEM

I’m not so interested inwriting

any Northern/Nature/Yukonerpoems about the Northern Lights and

my trusty-sled-dog-see-your-breath-adventureby all my poems turn

out to have animals inthem because that’s where I’m

and I do share 50% of my DNAwith a banana

so I don’t want to hearany more about how I’m

bad at sharing justbecause I’m an only child

and everybody’s bad atassumptions

well at the end of theday I was born

here at the end of theday in a thunder

storm of anesthesia andincubation

an animal purred intothat room, nipped

a neat umbilical, wolfed

my head right out of the womb. that’s its breath

on the window page

blurring

it makes a real hot meat view

FromWhitehorse, Yukon poet Dawn Macdonald comes the full-length debut

Northerny

(University of Alberta Press, 2024), a collection set in and responding to herparticular landscape, place and experience of what the rest of us in the lowerparts of Canada refer to as the north. “Fireweed is edible and best before /the bloom.” she writes, as part of the poem “ROADSIDE WILDFLOWERS OF THENORTHWEST,” “Pigweed, a sort of spinach. / Kinnikinnick, we called it / honeysuckle.There’s something else called / honeysuckle. We’d call it what / we want.” As shehighlit during her launch a few weeks prior, the poems here refuse the easydepictions and descriptions, and even work to correct outside narratives on andaround a place she knows intimately, but I would suggest she offers theseelements not as foreground but as an underlay, beneath her depictions andobservations, writing her own line across such intimate backdrop. “growth is itsown / value proposition.” she writes, as part of the poem “INCREASE,” “love’ssupposed / to be automatic / like transmission.”

FromWhitehorse, Yukon poet Dawn Macdonald comes the full-length debut

Northerny

(University of Alberta Press, 2024), a collection set in and responding to herparticular landscape, place and experience of what the rest of us in the lowerparts of Canada refer to as the north. “Fireweed is edible and best before /the bloom.” she writes, as part of the poem “ROADSIDE WILDFLOWERS OF THENORTHWEST,” “Pigweed, a sort of spinach. / Kinnikinnick, we called it / honeysuckle.There’s something else called / honeysuckle. We’d call it what / we want.” As shehighlit during her launch a few weeks prior, the poems here refuse the easydepictions and descriptions, and even work to correct outside narratives on andaround a place she knows intimately, but I would suggest she offers theseelements not as foreground but as an underlay, beneath her depictions andobservations, writing her own line across such intimate backdrop. “growth is itsown / value proposition.” she writes, as part of the poem “INCREASE,” “love’ssupposed / to be automatic / like transmission.”Macdonald’spoems flash light, offering intrigues of clarity, depth of lyric intrigueacross narratives that depict and document a particular kind of angled roughnessand wilderness. “One day the wind will have my heart, I guess,” she writes, aspart of the poem “WALKING THE LONG LOOP,” “flash fried and let fly from the jarof ash, / assuming such litter is permitted, and you’re there / to flip thatlid. / I could do worse than to lodge, / even the barest bonescrap, atop / a noduleof pine. Anything / with sap in it, a line / to the nearest star.”Playing offEmily Dickinson, her opening poem, “FIRST THINGS,” hold to the small moments ofchickens and broken eggs, writing: “Riddle wrapped up inside, / cased, laid,brooded, clucked upon, clean // as a whistle. An egg’s / a thing / withfeatures, but, order / of operations applies – a flashlight shone clean /through the inside / illuminates outline, diagram, edges blown: [.]”

May 24, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Pamela Porter

Born in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Pamela Porter immigrated to Canada in 1994, where she joined workshops with Patrick Lane and Lorna Crozier. Patrick Lane called her "a poet to be grateful for." Her work has earned many accolades, including the inaugural Gwendolyn MacEwan Poetry Prize, the Malahat Review's 50th Anniversary Poetry Prize, the Our Times Poetry Award for political poetry, the FreeFall Magazine Poetry Award, the Prism International Grand Prize in Poetry, the Vallum Magazine Poem of the Year Award, as well as the Raymond Souster and Pat Lowther Award shortlists. Her novel in verse, The Crazy Man, won the Governor General's Award, the Canadian Library Association Book of the Year for Children Award, the TD Canadian Children's Literature Award and other prizes. Both The Crazy Man and her later novel, I'll Be Watching, are required reading in schools and colleges across Canada and the U.S. Pamela lives on a farm near Sidney, B.C., with her family and a menagerie of rescued horses, dogs and cats.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book completely changed my life. I was born in the US and studied poetry and prose writing in undergraduate school at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. I even changed universities in order to be able to take the poetry writing class; I managed to do that during Christmas break one year. After undergraduate school, I was accepted to the University of Montana in order to take Richard Hugo's workshops in Missoula. But after graduation, I was on my own. I was born and grew up in the US and only came to Canada because my father in-law was in his nineties and wanted to retire from the business of growing wheat and other crops on the prairie land in Saskatchewan and Alberta, and my husband, and the only male son in the family, was the only one who might have any interest at all in Canadian farming. At the time, we lived in Montana, on the east side of the Rockies in a very fertile valley; as well, a river cascaded down river right beside our house and flowed into a lovely spot where beavers made their dams and even chewed down a few thin trees on our land to make their homes. We had very young children at the time and were happy where we lived. The only drawback as I saw it was that we would need to move to Canada in order for Rob to take on the farm business. Rob, my husband, told me of my father in-law's request, and asked that we think about the idea of moving to Canada.

My earliest experience of Canada took place when world's fairs were popular at the time and I goaded my family to drive us to San Antonio where there was going to be an abbreviated world's fair. When we arrived to the fair, I continued to nudge my family to visit the Canadian pavilion where, upon entry, cold air was blown at you on arrival and it was really dark inside, though the many photographs of Canada's beauty were spread along the walls. That about summed up what I knew about Canada. I was ten. Nonetheless, Rob and I thought seriously of moving north.

We had a Metis friend named Georgia who was looking for work and we were overwhelmed with the babies. We hired Georgia to help us with cooking and cleaning, and in return, she told us about her childhood.

Georgia lived in northwest Montana with her grandparents on a ranch and the family lived a hardscrabble life of poverty. A number of dams had been built on the east side of the Rockies, dams that were built by the Works Progress Administration in the 1930's, and all the dams were built from wood. One year while Georgia was still living with her grandparents, a storm came up and overwhelmed the area with rain. Well, all those dams burst at the same time. There was discrimination from the officials brought the flooded folks to rescue centers, who were tasked with separating the white folks from the First Nations. And slowly, the rebuilding.

That was my first attempt to write a novel. Of course, it needed to be a book my children could hear me read to them, and later, read to themselves.

I'd had rejection after rejection for so many years, I didn't know if this story, Sky, would be just another rejection. But an editor at Groundwood Books in Toronto, wrote back to me and said that the story had promise, but "it needs work," they said. I said that I was willing to do the work. How to start? We'll help you, they said. So I worked on Sky, the book, for weeks. The editors sent me more work. I did the work. One day I got a call from Groundwood Books to say that they were pleased with my edits and the board had decided to publish the book.

I held myself together enough to be able to thank the person on the other end of the phone; I hung up, sat down in a chair, and sobbed. I counted up how many years I had been working to create something that would be published rather than rejected. I counted that I had been working 25 years to see one of my stories published as a novel for young readers.

Once Sky was accepted for publication, I went to work on a book in free verse poetry, about a girl in Saskatchewan who suffers a catastrophic farming accident which alters her life, and how she works to recover from her life-long disability. As I thought about what I wanted to write, characters would come to me, as though each one sat beside me one by one and introduced themselves. I felt the presence of a large man sitting beside me, and quietly, I asked the presence his name. He said his name was Angus. That began the story The Crazy Man, over which I spent a year writing, and which later won the Governor General's Award for literature for young people. I still get cards and letters from readers about The Crazy Man and how some people say they keep the book on their bedside table and read from it their favourite parts.

I was having lunch with Patrick Lane some years ago, and he mentioned that it was as though the characters came across a kind of bridge in order to present themselves as part of the story. I said I had had a similar experience.

I wrote another book in free verse about WWII, titled I'll Be Watching which is read by students in high schools when teaching the second world war.

I came to fiction first because I wanted to tell Georgia's story. I came to poetry as a novel because I discovered from talking with students in schools that boys in particular will read a book in which there is a lot of white space on the page and often boys find reading such a book to be a relief and one they can enjoy rather that be overwhelmed by pages and pages filled with words. I have to say though, that for me, poetry really does come first for me.

As a child, I loved listening to to rhyming poetry, and as I grew up I looked for more books of poetry that would inspire me to write. I'm also a pianist, so music, and the music of words are important to me. The lyric for me is important, particularly in poetry. My father once gifted my mother with the Complete Poems of Robert Frost. One day when I was about 15, I finally drew up the courage to stand on a chair and take down that book, and I'd sit on the floor of my bedroom and read Frost's poems. I'd memorize many of them as I walked to school, though once I got to "Out, Out--" well, I didn't know what to do with that one, though over the years I realized what poetry can be in its many iterations.

How long does it take to start a writing project? Well, it depends on whether I see a novel in free verse or a poem of 15-30 lines. Sometimes the poem of 30 lines is more difficult because one may "worry the poem to death" when the poem is as good as it's going to get. Recently I uncovered the start of a poem and decided it just needed a little more attention. Sometimes first drafts appear fairly finished, though others may take much more time to come upon what the poet is working toward -- it is music that is needed, or some deft editing?

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I came to fiction first when I wrote Sky, because I wanted to show readers, especially young readers the rough lives Georgia's family experienced in the flood: the discrimination, the poverty, so that young readers will have a glimpse into another person's poverty and struggle.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It really depends on how much material you want to include in your writing project, whether prose is best -- and it can be a prose poem if that seems to be the way your brain is working, or it can open up to a story or a novel in prose. If the prose is working well, keep going. Some writers will present a piece of prose and then include a poem if it seems appropriate.

4 - Where does a poem or work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Usually I want to start with a poem or several, or a whole book of poems. Two people in my life have passed fairly recently, so I have been writing poems about them and about their lives. That's not to say that one can't include prose poems or prose in conjunction with poetry, as long as there is a balance in the project.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I do enjoy doing readings, because if I may say so, I'm a very good reader to an audience. I was fortunate in middle school in that I had an excellent speech teacher, who taught us how to create space when speaking, and how to provide emphasis when needed and to speak in a way that allows listeners to take in everything you want to say. I'm forever trying to get a speaker to learn how to use a microphone properly so that the audience will be able to understand all that is said.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Yes, I want readers/listeners to hear clearly what a poem or paragraph or haiku is about, and how can the listener/reader best understand the poem or prose piece? In that manner, we need to speak clearly and naturally so that the information being delivered is clear.

The questions I want to answer in my work are those that are of significant importance: how should we live so that others can live fully as well? How can we write in a way that helps others to see the critical questions which we as a society need to answer? How can we be awake to those questions so that we can begin to live toward the answers? There is so much destruction and pain and poverty in many parts of the world -- how can we begin to discover the answers?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I believe the role of the writer is to ask the questions which the society at large needs to confront.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Both.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Let another person whom you trust look through your work and give suggestions if needed.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to novels)? What do you see as the appeal?

I tend to stick with poetry though recently I've been writing prose poems which is a kind of hybrid. One doesn't get the music of the lines as much as lined poetry, but it holds onto the visual elements, I think.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Well, I have a writing group who keep me going and asking questions of the poems, or prose, which is always interesting.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I look for books of poetry or of prose poems for inspiration.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

The pinon scent of New Mexico, where I was born.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Visual art influences me, particularly Van Gogh.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Music, whether written or sung or played on instruments.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

A book of poems with paintings: whose, I'm not sure.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Probably, a teacher, though having to grade papers would be the end of me, I think.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I wanted music in my life, and colour, and art.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Esi Edugyan's Washington Black.

20 - What are you currently working on?

a collection of prose poems.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

May 23, 2024

As I was going by The Market Cross : Noviomagus, Chichester,

Side by side, their facesblurred,

The earl and countess liein stone,

Their proper habitsvaguely shown

As jointed armour,stiffened pleat,

And that faint hint ofthe absurd –

The little dogs undertheir feet.

Philip Larkin,“An Arundel Tomb,” 1956

[see my report on the first part—Hammersmith + West Sussex—here]

[see my report on the first part—Hammersmith + West Sussex—here]Tuesday,May 14, 2024: As Christine wandered off for day one of her two-day course at West Dean (where she had schooled nineteen years prior, for the sake of becoming the stunningly talented book and paper conservator she is today), the young ladies and I made for the pub, and for breakfast. Already more than a couple of older locals set in their seats with pints. The night prior, Ruth had dropped us at our hotel, and there was barely time for take-away for dinner before everyone crashed. The young ladies weren't convinced by the pizza, so the pub across the street did seem to have a wider menu, and felt a better option.

“NoviomagusReginorum was Chichester’s Roman heart,” the internet offers, “very little ofwhich survives above ground.” This was originally a Roman settlement, with apparently little to no evidence of occupation in this particular spot until the Romans came through. Did you know this was a Roman settlement? Despite Rose complaining she would never go to another pub, we had a breakfast they enjoyed (Rose had two rounds of pancakes), before we headed off for adventures.

“NoviomagusReginorum was Chichester’s Roman heart,” the internet offers, “very little ofwhich survives above ground.” This was originally a Roman settlement, with apparently little to no evidence of occupation in this particular spot until the Romans came through. Did you know this was a Roman settlement? Despite Rose complaining she would never go to another pub, we had a breakfast they enjoyed (Rose had two rounds of pancakes), before we headed off for adventures.As we were literally beside the Cathedral, we wandered through, which the young ladies resisted at first, but enjoyed enough they claimed we would be returning. They ended up enjoying the space, which was helped by a small group of musicians practicing for their noon-time concert (the children also took turns taking photos with my phone, although Rose only seems to have taken selfies, her expression with devilish glee as she pretended to take pictures of a variety of exhibits). ChichesterCathedral, where British poet Philip Larkin and Monica Jones visited in January 1956, avisit that prompted his poem “An Arundel Tomb,” a poem included in The Whitsun Weddings (1967), a collection that, curiously (or even, wisely) enough, the bookstore across the road had copies of (Rose insisted we visit the bookstore before heading into the church). Instead, I picked up a copy of Luke Kennard's Notes on the Sonnets (Penned in the Margins, 2021), continuing my tradition of landing in England and purchasing one of his books. Given Rose has been composing poems lately (entirely on her own), I was tempted to prompt the young ladies to write their own response to what Larkin had taken as a poem-prompt, but we didn't quite get there.

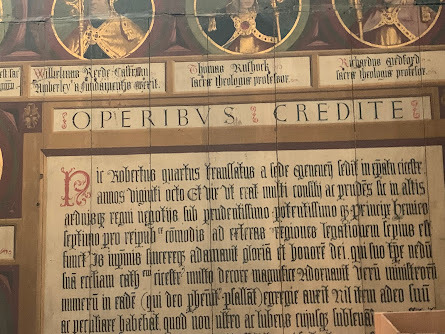

As we were looking at this very expansive and stunning painted panel (above) from the early 1500s (apparently one of the first full-length depictions of Henry VIII), a gentleman with a sweater sprinkled with paint sidled up and asked if I was American. Oh, no, I said. Oh, I have a fact that you might have liked, if you were an American. I told him I loved facts (left: Aoife's photo of me listening to this random stranger offer historical facts), so he offered that one of the figures painted in that large wooden panel (one of the circles) was a direct ancestor of Mary Todd Lincoln, wife of American President Abraham Lincoln. In turn, I later offered this fact to one of the Church guides, who didn't know this at all! I left it with her, naturally, to attempt to verify.

As we were looking at this very expansive and stunning painted panel (above) from the early 1500s (apparently one of the first full-length depictions of Henry VIII), a gentleman with a sweater sprinkled with paint sidled up and asked if I was American. Oh, no, I said. Oh, I have a fact that you might have liked, if you were an American. I told him I loved facts (left: Aoife's photo of me listening to this random stranger offer historical facts), so he offered that one of the figures painted in that large wooden panel (one of the circles) was a direct ancestor of Mary Todd Lincoln, wife of American President Abraham Lincoln. In turn, I later offered this fact to one of the Church guides, who didn't know this at all! I left it with her, naturally, to attempt to verify.

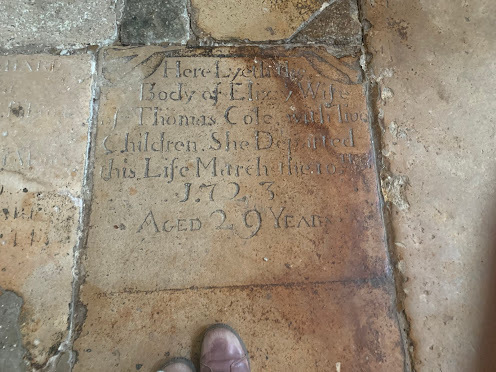

The young ladies were quite fascinated by the amount of markers within the church, articulating burial. They couldn't quite believe how many, and that people were stepping on these! Oh, we should get you two to Westminster, I thought, where some 3,000 are buried (I think every single stone is a marker; Chichester Cathedral seems quite sparse in comparison). Aoife took many, many photos of these markers (including this one, above), attempting to wrap her head around the gravesite within the boundaries of the Cathedral building. And then, of course, there was the Roman mosaic discovered a full metre underneath the floor some years back while working routine maintenance to the building. I did ask if the Romans held this space as a religious site, but apparently it was, during that period, the site of a very grand house.

The young ladies were quite fascinated by the amount of markers within the church, articulating burial. They couldn't quite believe how many, and that people were stepping on these! Oh, we should get you two to Westminster, I thought, where some 3,000 are buried (I think every single stone is a marker; Chichester Cathedral seems quite sparse in comparison). Aoife took many, many photos of these markers (including this one, above), attempting to wrap her head around the gravesite within the boundaries of the Cathedral building. And then, of course, there was the Roman mosaic discovered a full metre underneath the floor some years back while working routine maintenance to the building. I did ask if the Romans held this space as a religious site, but apparently it was, during that period, the site of a very grand house.

Again, Aoife took photos of the markers and other items (left, above) within the church, and Rose took selfies.

Again, Aoife took photos of the markers and other items (left, above) within the church, and Rose took selfies.

Did you know there is a window in this Cathedral designed by Marc Chagall? Absolutely stunning. Curious, also, to see from the outside, later, once we had returned to the street. The street, were we were briefly distracted by a tow-truck moving to salvage a broken-down bus; Aoife wanted to watch the bus get towed.

Did you know there is a window in this Cathedral designed by Marc Chagall? Absolutely stunning. Curious, also, to see from the outside, later, once we had returned to the street. The street, were we were briefly distracted by a tow-truck moving to salvage a broken-down bus; Aoife wanted to watch the bus get towed.

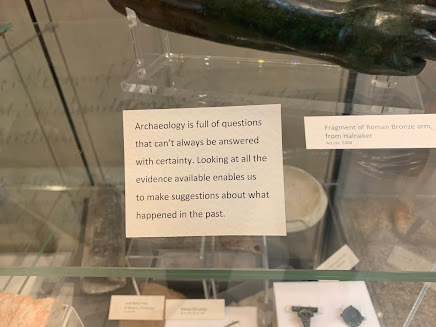

From there, we headed to the Novium Museum, Chichester's museum of Roman artifacts and history. The first two floors are Roman history, and the building and exhibit are entirely constructed around Roman ruins found a meter or two under street level, which is pretty cool. Not a large space, it did include a vast array of items discovered in the area, information on history from the origins of the Roman occupation to the present, and costumes to play in and what-not. And bones.

From there, we headed to the Novium Museum, Chichester's museum of Roman artifacts and history. The first two floors are Roman history, and the building and exhibit are entirely constructed around Roman ruins found a meter or two under street level, which is pretty cool. Not a large space, it did include a vast array of items discovered in the area, information on history from the origins of the Roman occupation to the present, and costumes to play in and what-not. And bones.

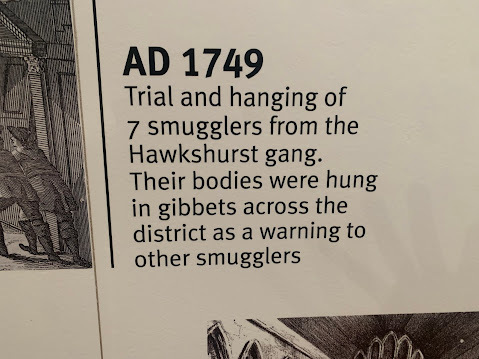

Although I did have to inquire at the front desk as to what "gibbets" were (which is why I snapped this particular photo).

Although I did have to inquire at the front desk as to what "gibbets" were (which is why I snapped this particular photo).

And did you know a local boy made it into the British space program? They do seem pretty proud of him (and rightly so), although odd to see this timeline for him offered in a part of a Roman museum. On her part, Rose was focused on a short video (that she watched in a loop at least three or four times) on a murderous local gang.

And did you know a local boy made it into the British space program? They do seem pretty proud of him (and rightly so), although odd to see this timeline for him offered in a part of a Roman museum. On her part, Rose was focused on a short video (that she watched in a loop at least three or four times) on a murderous local gang.

I, for one, was delighted by the Roman finds [impressive, albeit less so than the museum we visited in Paris during our honeymoon]. It was exciting to even see a photograph, as part of the Roman timeline of the space, of Time Team legend Phil Harding, my absolute favourite British archaeologist (we all have favourite British archaeologists, don't we?). Oh, to have visited a spot he helped research and reveal! Also, given Rose had begun watching episodes of Time Team with me a couple of years back, it was interesting (and felt important) to provide her with a connection to the site (and it made me wonder if there was even an episode dedicated to uncovering some of this--I have yet to look into this, for the sake of a re-watch).

I, for one, was delighted by the Roman finds [impressive, albeit less so than the museum we visited in Paris during our honeymoon]. It was exciting to even see a photograph, as part of the Roman timeline of the space, of Time Team legend Phil Harding, my absolute favourite British archaeologist (we all have favourite British archaeologists, don't we?). Oh, to have visited a spot he helped research and reveal! Also, given Rose had begun watching episodes of Time Team with me a couple of years back, it was interesting (and felt important) to provide her with a connection to the site (and it made me wonder if there was even an episode dedicated to uncovering some of this--I have yet to look into this, for the sake of a re-watch).

From there, we headed north a few blocks to the north boundary of the original Roman settlement; a great deal of the Roman walls and gateways still surround the downtown core of Chichester, so we strolled a few blocks' worth east, to see what we could see, and imagine our eyes out across the horizon, attempting to provide protection from the barbarian (local) hordes.

From there, we headed north a few blocks to the north boundary of the original Roman settlement; a great deal of the Roman walls and gateways still surround the downtown core of Chichester, so we strolled a few blocks' worth east, to see what we could see, and imagine our eyes out across the horizon, attempting to provide protection from the barbarian (local) hordes.

From there, we headed back south, through an array of shops (Rose had been clamouring for some shops for clothing, trinkets, makeup, jewellery, etcetera). Fortunately, we found some charity shops, so their shopping managed some inexpensive clothes, a necklace and ring or two. Aoife managed to find a nice dress. Rose picked up a purse (that promptly broke within a couple of days; we are attempting to fix it). And, after I explained that one particular charity shop was to help animal shelters, Rose promptly donated the 5p she found on the street earlier in the day (naturally, she was offered a receipt for such, which I suggested she keep for her records).

From there, we headed back south, through an array of shops (Rose had been clamouring for some shops for clothing, trinkets, makeup, jewellery, etcetera). Fortunately, we found some charity shops, so their shopping managed some inexpensive clothes, a necklace and ring or two. Aoife managed to find a nice dress. Rose picked up a purse (that promptly broke within a couple of days; we are attempting to fix it). And, after I explained that one particular charity shop was to help animal shelters, Rose promptly donated the 5p she found on the street earlier in the day (naturally, she was offered a receipt for such, which I suggested she keep for her records).

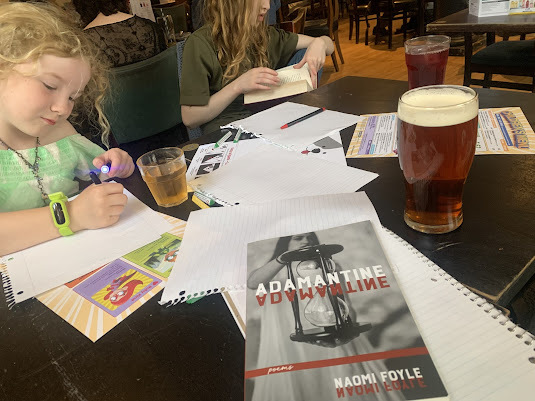

And then back to the pub, for a mid-afternoon lunch (directly across from the Cathedral). Aoife drew, Rose went through her bracelet-making kit, I worked on some postcards. The Dolphin and Anchor. Aoife had a hamburger she actually ate (most restaurants she orders and doesn't finish, because it "tastes weird,"). Rose went through two orders of onion rings. I had a bitter, and made notes.

And then back to the pub, for a mid-afternoon lunch (directly across from the Cathedral). Aoife drew, Rose went through her bracelet-making kit, I worked on some postcards. The Dolphin and Anchor. Aoife had a hamburger she actually ate (most restaurants she orders and doesn't finish, because it "tastes weird,"). Rose went through two orders of onion rings. I had a bitter, and made notes.

After an hour or so here, we crashed a bit in the hotel, before heading out again, to meet up with local writers and profs at the local university, Naomi Foyle and Suzanne Joinson. I was startled to discover Foyle a few days prior online, given she is a British-Canadian poet raised in (among other places) Saskatchewan, during the time that her mother, the late writer Brenda Riches, was not only president of the Saskatchewan Writers Guild, but editor of

Grain magazine

. How had I not heard of her? Apparently we know a ton of folk in common (Regina poet Brenda Niskala, who I toured across Canada with during a five-poet tour in spring 1998, was actually arriving the following day to have lunch with Foyle). Foyle and I traded poetry books (separate to the envelopes of chapbooks I'd brought for them) and apparently Joinson has a new memoir out in September that sounds pretty interesting. They were delightful! And the young ladies had ice cream from the cafeteria, so they were also pleased.

After an hour or so here, we crashed a bit in the hotel, before heading out again, to meet up with local writers and profs at the local university, Naomi Foyle and Suzanne Joinson. I was startled to discover Foyle a few days prior online, given she is a British-Canadian poet raised in (among other places) Saskatchewan, during the time that her mother, the late writer Brenda Riches, was not only president of the Saskatchewan Writers Guild, but editor of

Grain magazine

. How had I not heard of her? Apparently we know a ton of folk in common (Regina poet Brenda Niskala, who I toured across Canada with during a five-poet tour in spring 1998, was actually arriving the following day to have lunch with Foyle). Foyle and I traded poetry books (separate to the envelopes of chapbooks I'd brought for them) and apparently Joinson has a new memoir out in September that sounds pretty interesting. They were delightful! And the young ladies had ice cream from the cafeteria, so they were also pleased. Although I had been nervous about making our scheduled 5pm tea on time, landing at our hotel lobby with kids for a cab at 4:50pm (I had confirmed the idea was solid the night prior with the front desk), only for the cab company to inform it would take an hour for a cab to arrive? God sakes. Fortunately, it only took twelve minutes to get there, and the front desk (upon repeated prompts) finally let me know on my museum-gifted map where the university was. I had been hoping to cab for the sake of both not getting lost, and to not put the kids through such a random walk, but we figured it out.