Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 50

June 19, 2024

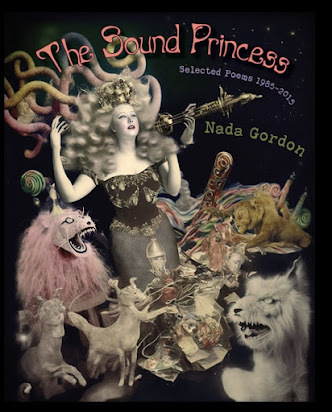

Nada Gordon, The Sound Princess: Selected Poems 1985-2015

My review of Nada Gordon's The Sound Princess: Selected Poems 1985-2015 (Brooklyn NY: Subpress Collective, 2024) is now online at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics. See my review of her chapbook-length selected,

The Swing of Things

(Subpress, 2022) here.

My review of Nada Gordon's The Sound Princess: Selected Poems 1985-2015 (Brooklyn NY: Subpress Collective, 2024) is now online at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics. See my review of her chapbook-length selected,

The Swing of Things

(Subpress, 2022) here.June 18, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Lynn Joffe

Bornin London (England) and raised on four continents,

Lynn Joffe

has written and produced avast array of storytelling projects for radio, stage and TV. Lynn graduatedwith an MA (cum laude) in Creative Writing at the University of theWitwatersrand’s School of Literature, Language and Media, in 2017. Her debutnovel,

The Gospel According to Wanda B. Lazarus

, was published in November 2020and was longlisted for The Sunday Times/CNA Literary Awards and shortlisted forthe NIHSS Award for Fiction. She has performed in a variety of self-pennedcabarets, published a children’s picture book, The Tale of Stingray Charles.Lynn produced and presented a 13-part jazz series, Bejazzled, whichflighted across Africa. Lynn is a podcaster of Solid Gold Story Time and hasdeveloped and presented a myriad of storytelling workshops for all ages andstages of the writing journey.

Bornin London (England) and raised on four continents,

Lynn Joffe

has written and produced avast array of storytelling projects for radio, stage and TV. Lynn graduatedwith an MA (cum laude) in Creative Writing at the University of theWitwatersrand’s School of Literature, Language and Media, in 2017. Her debutnovel,

The Gospel According to Wanda B. Lazarus

, was published in November 2020and was longlisted for The Sunday Times/CNA Literary Awards and shortlisted forthe NIHSS Award for Fiction. She has performed in a variety of self-pennedcabarets, published a children’s picture book, The Tale of Stingray Charles.Lynn produced and presented a 13-part jazz series, Bejazzled, whichflighted across Africa. Lynn is a podcaster of Solid Gold Story Time and hasdeveloped and presented a myriad of storytelling workshops for all ages andstages of the writing journey.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to yourprevious? How does it feel different?

Mydebut novel revolutionised my life. My sense of accomplishment. The feelingthat I knew I had it in me. And now it was out of me. Seven pregnancies later.A combination of working towards a Master of Arts in Creative writing – whichgave me the structure and discipline – and plain hard graft mixed with wit andimagination. Using my writing chops which have seen me as a copywriter, contentcreator, cabaret performer, children’s storyteller and now, published author. Completingand publishing a novel of literary merit was a milestone in my creative self-actualisation.

1 - How does your most recent work compare to yourprevious? How does it feel different?

Project1: ‘Kol B’Isha Erva: A Woman’s Voice is … Inappropriate’ Short StoryCollection

Afterthe publication of The Gospel According to Wanda B. Lazarus, my academichusband asked, ‘Where’s the next book, Lynn?’ Exhausted as I was, I applied forand was accepted into a PhD in Creative Writing at the University of Pretoriabetween 2020-2023. My working theme: ‘Kol Isha B’erva: The voice of the womanis … inappropriate.’ This is a misinterpreted quotation from the Song ofSolomon that banished women to the womb and the scullery for all eternity. Sothe theme is eternal, the approach; short stories. I began to write pieces in avariety of styles and perspectives of lost voices of the feminine, from Lilith(‘What? Me spurned?’) to my childhood experiences of antisemitism (‘Are Yoo aJoo?’). Trying to lose the Wanda voice and find other characters and points ofview. I experiment with the form for two years, thinking I had eons to completewhat was, in fact, a post-exhaustion novel fallowness.

Project2: ‘The Year of Dying Courageously’ A love letter to my sister A Memoir ofGrief

Here'sthe irony: Two years after having written a novel narrated by a time travellingpicara, accidentally cursed with immortality, who dies at the end of eachchapter, my own sister died fromcancer in real life. Everything stopped. The writing of fiction, or even thelooking at what I’d written, became a meaningless, trivialised abyss. All Icould write was of her, to her, about her. Telling her about what happened inthat ‘Year of Dying Courageously.’ At some point I will reread and rearrangethe thousands of words I have penned to her as perhaps a memoirish dialoguewith the dead that explores our traumatised childhood, our separation, her wildpast, the everlasting nearness of her. But this is a private rave, a privaterage, and I don’t see myself readying this as a manuscript until I’m out of theshadow of the valley.

Project3: ‘The Comedian Who Killed My Family’ Auto-Fiction (based on untrue events)

Longbefore Wanda was a twinkle, there had been a story festering within. The MAgave it time to marinade. It has resurfaced as developing multiple perspectivework of auto-fiction, titled, ‘The Comedian Who Killed My Family’; time spannedfrom present to past recalling two weeks in Sydney Australia where the mostfamous comedian in the English speaking world came to a booze-soakedamphetamine-pumped end in our home. I was nine. That kid’s recall was the firstvoice to emerge. And then, one day writing, the suicider revealed himself to mein his opening sentence, ‘Nobody was more surprised than I was when I woke updead.’ And it started pouring out. This is a story more than fifty five yearsin the making. I have half a manuscript I’ve promised to my new-found agent.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposedto, say, poetry or non-fiction?

Atfirst, The Gospel According to Wanda B. Lazarus started as a memoir, writtenfor the purposes of an MA in Creative Writing at the University of theWitwatersrand. It was to be a personal bildungsroman, a portrait of the writeras teenage rebel, transplanted to Apartheid as a rank outsider to be told,‘You’re a woman. A whitey. And a Jew to boot.’ Triple Oy. I did have to have a proposal,though, which behoved me to explore the hypothesis of Nomadness: a portmanteauof a nomad and the madness of a transgressive life orientation. The premisewas, ‘What if the Wandering Jew … was a woman.’ An exploration of otherness andantisemitism, buried deep within whatever culture I have encountered throughoutthe ages. I started to explore my own life trauma, from which there is plentyto draw, and reread the words of my own #metoo moment as the underage groomeein the erotic clutches of the youth leader twice my age, ‘He had me … in theshadow of the Temple.’ This sentence struck me as numinous, perhaps evenluminous. ‘What if,’ I said to myself, ‘it wasn’t Temple Shalom on Louis BothaAvenue … but The Temple, the original Temple, the one in Jerusalem?’ And,‘What if … the kombi minivan he groped me in was a stinky camel cart?’ And, ‘Whatif … he tried to ravage Wanda in the Holy of Holies and she fights back like a nastywoman?’

TheGypsy Girl of Gazientep

Asecond synchronicity came to pass. Around the time of transition to fiction, Istarted researching my Google off. I knew I wanted to rear engineer my #metooexperience back to the time of the crucifixion. The first time that Jesusallegedly cursed a member of his tribe. And then I found her. The face of WandaB. Lazarus herself. Embodied in the mosaic of the Gypsy Girl of Gazienteparound 200 CE (what’s in a couple of centuries between friends?). The firsttime ever I saw her face, some kind of bizarre alchemy occurred between hecharacter and the writer. All I had to do was sit down at the typewriter … andbleed. The discovery of my ability to write fiction was a revelation to me. Itfeels I’ve been doing this all my life. And yet, it’s ripened, deepened.

Themoment I became ‘other’ to my protagonist, Wanda became my mouthpiece, mydoppelganger and within the process, transformed my own story into a novel. Icreated a universe of imagination and transformation featuring a free-wheeling,foul-mouthed, sexually-charged picara who wanders through the ages at thebehest of the muses of antiquity in her quest to become The Tenth Muse.

3- How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does yourwriting initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appearlooking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copiousnotes?

Ibelieve in Anne Lamott’s dictum of ‘the shitty first draft.’ Get it down onpaper or pixel and then begin to tease it into its final shape. I have to havea routine; writing every day. Sitting down at the typewriter … and bleeding, asErnest Hemingway advised. I write quickly if I’m on a roll. And even if thespirit doesn’t move me, with the novel, Wanda did much of the dictation. As Iwas also doing a Masters, I had to have consciousness (and a proposal and areflective essay) as to what I was doing. But overall, it’s a painstakingprocess. It doesn’t have to be perfect. It needs to be complete.

Giventhe abyss of the past two and a half years, my output has been truncateddrastically. I’ve recently started to look at writings from before ‘the birthof Wanda,’ and am finding some engaging pieces, fragments, really, that need tobe worked on, edited, polished, story told. Kawabata approves of this. I’vealso written down dreams from the early noughties that would fill a mythologybook. I tend to write and rewrite, saving each version with a differentalphabetical suffix to the date. So I can monitor my progress. Print out. Read.Do another draft. I got up to XX on some of my drafts. That’s 46 drafts,sometimes. I’ve also kept scrapbooks of storylines and doodles and spiderdiagrams of characters and scenarios.

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin foryou? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a largerproject, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Forme, it began with memoir and morphed into fiction. I have led a full andfruitful and oftentimes daring life. And somewhere along the process,imagination fuses with memory to create an original piece. Right now, with theshort stories, I busy myself with the ‘one square inch’ of writing scenes thatcould be pieced together later. Only the book knows what it’s going to become.Wanda’s adventures are a kind of story cycle within a frame story as shetraverses the ages. It’s the writing that counts. The editing comes from adifferent part of the creative brain.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to yourcreative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I’ma huge show-off. I read wherever I’m asked and have done a few on-linereadings. Published during Covid, it was the first norm I knew. I write from myintrovert and perform from my extravert. I’m currently in the process ofvoicing the audio book (18 hours, I’ve estimated). It’s like an eighteen hourradio play. Here’s a QR code to listen to extracts of the novel. I’ve also doneinterviews which contain readings for book fairs and festivals in South Africa,Sweden and the UK.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behindyour writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work?What do you even think the current questions are?

Ido believe that ‘value is the soul of storytelling.’ There’s always a ‘message’of some kind in the undergrowth of a good story. As a person of Jewish origin,I’ve found more and more that this identity must be explored, questioned,unravelled. My novel dealt with the ubiquitous presence of antisemitism in thehuman condition. And as a woman, a woman of Africa and a pale native, thisquestion of identity, belonging, outsiderness, transgression, is present ineverything I write. Who am I? Who are we? The paradoxes of being a humanfemale. I didn’t think there was any burden on me to contribute to worldculture. But strangely, after October 7, the question has become immanent,worthy, troubling.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writerbeing in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role ofthe writer should be?

Ibelieve I have an age-old story to tell in my own unique way. Even though mybook is about the transgressive Jewish experience, it resonates for the humancondition of scapegoating, the female experience throughout history, and my owninsights and explorations into this theme. So yes, the writer should contributeto the zeitgeist of the age.

Ofcourse, having written a novel about a Jewish protagonist, I outted myself asan author of Jewish extraction. Now, with the attitude of antisemitism in thepublishing industry (Come out as a Zionist, the industry will cancel you; comeout as pro-Palestinian, the tribe will get you!) it will be interesting to seewhether Wanda has a future outside the South African bubble. I’m not sure what#writingwhileJewish will bring. I feel now what a White male Afrikaner may havefelt at the end of Apartheid. Not every word I write is about the ‘Jewishcondition.’ But, as with any author of cultural validity, it will infuse andinform my world view forever. Time will tell … and I’m not telling. Yet.

8 - Do you find the process of working with anoutside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Iwas lucky enough to acquire a professional editor who worked with me from thetime I graduated with the original work to the publication of the novel. Twoyears! Even though I have extensive writing experience, I had no idea what aneditor actually did. At first, it was a shock to have her insert words andchanges into the manuscript. But as we progressed, I realised the absolutenecessity of a good editor. And I’ll never attempt to publish without one. Withouther.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard(not necessarily given to you directly)?

Duringthe Masters tutorials, there was a woman who wrote the most magnificent prose.But very scanty quantity. When asked why, she said, ‘Ag, man, I need to beinspired.’ One of the tutors, a highly decorated author, said to her: ‘Well, Ihope you’re near your computer when inspirations strikes.’ What I took fromthis is … you can’t wait for inspiration to strike. You have to simply, ‘Sitdown at the typewriter … and bleed.’

10 - How easy has it been for you to move betweengenres (short stories to cabaret to writing for children to the novel)? What doyou see as the appeal?

I’mable to write to any genre, really. Copywriter’s Derangement Syndrome. Children’sstories are easier to access, sometimes arrive with little songs, and flow frommy pen without the agony of fiction. And yet. And yet. I have to write now.Meaningful fiction. With the lightest touch. If you look at the three projectsI’m disenfragmenting, they are all quite different. A novel is what I strivefor. The short stories are what I wish to conquer. The sister memoir is stillin play. The appeal? It needs to appeal to me, first and foremost. I know whatmy standard can be. Recognition is important. But I don’t work towards that asan incentive.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend tokeep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Duringthe writing of Wanda, I was as disciplined as a disciple. I wrote everymorning, from the time I opened my eyes around 7am until around noon. I can’twrite all day long and I have had a business to run. A regular writing routineis the only way and I’m striving to return to this. I love writing retreats andtry to see my daily work as such. Any distraction leadsto the break in routine. Getting back to this practice is my life’s wish.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do youturn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Significantmemories. Dreams. Reflections. I thumb through previous writings to see ifsomething prompts me to continue. Or just write until something comes up.Prompts help too.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Thepungent scent of a Highveld thunderstorm rising off freshly polished parquet.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books comefrom books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whethernature, music, science or visual art?

Agreethat books come from books. I trained as a jazz musician for eighteen years andthe theory I absorbed so completely through my fingers has also affected mybrain. I also started to create ‘collage characters’ out of found recycledmaterials. These develop into little characters that I use for my children’sstories. I created cartouches for the Wanda book that I’ve used for bookletsand other promotional material. Myhusband is a visual artist and art historian and we often discuss the confluencesof the artistic process in any medium.

15 - What other writers or writings are importantfor your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I’mreading a slew of short stories now, a hangover from my ill-fated PhD, butchecking out the forms and content a short story can take. Rereading AntonChekov and George Saunders, discovering Lydia Davis and Cynthia Ozick. I’vestudied the classics, poetry and fiction, and they have a subconscious effecton me. I also adore writers who can write about massive human issues with thelightest touch. If I could choose three, I’d say: Phillip Roth, Kurt Vonnegutand Virginia Woolf.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yetdone?

Iwish to continue writing literary fiction of the finest standard. And having itpublished by a reputable publisher and the work reaching beyond the SA bubble. TheGospel According to Wanda B. Lazarus is my debut novel. I hope to live a longlife and get my writing out there. South Africa is a bit of a publishingbubble, but I have acquired a US agent now and would love to get my work outinto the world. The Booker Prize, perhaps. Too old for Nobel?

17 - If you could pick any other occupation toattempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would haveended up doing had you not been a writer?

I’venever been able to earn a living as a musician. It’s fun, but penury is rife. Ihave been a copywriter all my adult life, and earned a living that way. I canwrite in a compendium of styles according to a briefs. But fiction is whereI’ve found my voice, and, late to the game, I must bestow upon myself the timeto cultivate my superpower. I’m also an excellent typist. So it could havestopped right there. But something always draw me to further, to more. And thisis it.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doingsomething else?

Itwas time. I’d spent the breeding, bleeding years writing stories for everyoneelse. And filthy lucre. Brands. Corporates, Cabarets. TV shows. Radio dramas. Fromthe moment I began my Wanda journey, I sensed I was onto something that wouldbring out the best in my thinking and writing. And my life. As Maya Angelousays, whomever says, ‘There is no greater agony than bearing an untold storywithin you.’ Who knew?

19 - What was the last great book you read? Whatwas the last great film?

Theonly writing that has comforted me in a deep philosophical and emotional sensehas been The Dark Interval, Rainier Maria Rilke’s collected letters on loss,grief and consolation. Literature has been hard to hold on to, so I’ve beenretraining my brain with short stories. Rereading Anton Chekhov and George Saunders, discovering Lydia Davis and Cynthia Ozick. I was also recently thelead judge in the CCI Award for Fiction under the auspices of the Department ofSport, Arts and Culture and had to ‘read’ 328 South African books in a week! SoI’ve given myself a crash course in South African literature. The novel weawarded the prize to is called On That Wave of Gulls by Vernon Head. Itdeserves to be read outside the bubble.

Movie-wise,we are avid foreign film watchers. The Spanish movie, Quién te Cantarà directedby Carlos Vermut is a perennial favourite and has echoes of my own life story.Anything by Abel and Gordon, the Belgian comic duo. Most recently made movie torave about is Todd Field’s Tár. Greatest movie of all time, Bob Fosse’sCabaret. I must have seen it a hundred times. Also hooked on old time Hollywoodmusicals. And anything French.

20 - What are you currently working on?

(Seequestion 2 above. This is a summary)

Ihave three projects on the go, to which, once I can emerge from the chrysalisof grief, I can apply my creative writing self. I am halfway through (I think!)a manuscript of a work of auto-fiction, ‘The Comedian Who Killed My Family’,a multiple perspective work, based on the death of a famous comic who committedsuicide in my family home in Australiain the late 60’s. I’m also recollecting a series of short stories based on thetheme of ‘Kol B’Isha Ervah,’ – the voice of the woman is … inappropriate.’ Mylove letter to my sister, ‘The Year of Dying Courageously,’ is more a diarythan a memoir at the moment and will take time and distance to massage into areadable form. I’m taking some light relief in polishing up a slate of musicalchildren’s stories, which seem to pour out of me.

June 17, 2024

Michael Goodfellow, Folklore of Lunenburg County

BALLAD

—tide scraped againstrusty grate,

against ironstone, in andout of the culvert,

creosote burnished,

and pulled at itsbleached beams

and rafters waterloggedwith rot

salt had almost beenenough to stop

—pulled at graves of theProtestant dead

at Riverport, in Creaser’sCove,

at whitewashed stones andapple root

washed clean, bright withtawn,

where in some pit the searustled

and threw up sand

—d metal flaked off fromthe world above,

hulls, rock ground offGaff Point,

wind pulled, sky turned,

salt line drawn,

horizon flat across theriver’s face

and blew to keep the gashin place

Thesecond full-length poetry title by Lunenburg County, Nova Scotia poet Michael Goodfellow, following

Naturalism, An Annotated Bibliography: Poems

(Kentville NS: Gaspereau Press, 2022) [see my review of such here], is

Folklore of Lunenburg County

(Gaspereau Press, 2024). Goodfellow’s latest collectionriffs off the volume

Folklore of Lunenburg County, Nova Scotia

(OttawaON: E. Cloutier, King’s Printer, 1950) by Dartmouth, Nova Scotia folklorist Helen Creighton (1899–1989), the spirit of that particular collection utilized as aprompt for Goodfellow’s explorations on landscape, folklore and storytellingthrough the form of the narrative, first-person lyric. According to one onlinebiography for Creighton: “She collected 4,000 traditional songs, stories, andmyths in a career that spanned several decades and published many books andarticles on Nova Scotia folk songs and folklore.” “A haunting was a dream youhad with your eyes open,” Goodfellow writes, as part of “OTHERS SAIDDISAPPEARANCE / WAS RINGED LIKE A TRUNK,” “just as the sky was paved with thelight of stones. / The forest was a wall that painted itself. / The forest wasa door that didn’t close.” As the back cover of Goodfellow’s collection offers,his poems “are rooted in the ethnogeography of Helen Creighton and theotherworldly stories of supernatural encounters that she collected on the southshore of Nova Scotia in the mid-twentieth century. For Goodfellow, theseaccounts evoke much more than quaint records of a primitive time and place.” Partof the strength of Goodfellow’s lyrics is his ability to offer such precise physicality,composing poems hewn, and hand-crafted with a hint of wistful, folkloric fancyin otherwise pragmatic offerings. “The light how stars are brighter / when you don’tstare at them,” he writes, to open “WINTER LEGEND,” “how a fall day could feellike spring, / how a dog won’t look at you when it’s frightened, // how ash isthe last to leaf, / how on certain nights / it was said that animals couldspeak, // how we named the stars other things. / How often their names wereanimals.”

Thesecond full-length poetry title by Lunenburg County, Nova Scotia poet Michael Goodfellow, following

Naturalism, An Annotated Bibliography: Poems

(Kentville NS: Gaspereau Press, 2022) [see my review of such here], is

Folklore of Lunenburg County

(Gaspereau Press, 2024). Goodfellow’s latest collectionriffs off the volume

Folklore of Lunenburg County, Nova Scotia

(OttawaON: E. Cloutier, King’s Printer, 1950) by Dartmouth, Nova Scotia folklorist Helen Creighton (1899–1989), the spirit of that particular collection utilized as aprompt for Goodfellow’s explorations on landscape, folklore and storytellingthrough the form of the narrative, first-person lyric. According to one onlinebiography for Creighton: “She collected 4,000 traditional songs, stories, andmyths in a career that spanned several decades and published many books andarticles on Nova Scotia folk songs and folklore.” “A haunting was a dream youhad with your eyes open,” Goodfellow writes, as part of “OTHERS SAIDDISAPPEARANCE / WAS RINGED LIKE A TRUNK,” “just as the sky was paved with thelight of stones. / The forest was a wall that painted itself. / The forest wasa door that didn’t close.” As the back cover of Goodfellow’s collection offers,his poems “are rooted in the ethnogeography of Helen Creighton and theotherworldly stories of supernatural encounters that she collected on the southshore of Nova Scotia in the mid-twentieth century. For Goodfellow, theseaccounts evoke much more than quaint records of a primitive time and place.” Partof the strength of Goodfellow’s lyrics is his ability to offer such precise physicality,composing poems hewn, and hand-crafted with a hint of wistful, folkloric fancyin otherwise pragmatic offerings. “The light how stars are brighter / when you don’tstare at them,” he writes, to open “WINTER LEGEND,” “how a fall day could feellike spring, / how a dog won’t look at you when it’s frightened, // how ash isthe last to leaf, / how on certain nights / it was said that animals couldspeak, // how we named the stars other things. / How often their names wereanimals.”Collectedacross two section-halves, “TOPOLOGIES” and “REVENANTS,” the poems of Goodfellow’sFolklore of Lunenburg County, Nova Scotia are grounded in a particulargeographic tradition of storytelling, crafted through direct statements thatbend as required, offering hints of unexplained conditions and supernaturalencounters, extending or turning his view. His is a precise lyric of landscape anddreams, folktales and loss. As he writes to close the poem “GHOST STORY”: “Whenthe ground was cold such things were clear. / Only later did it seem like we’dimagined them.” There is something intriguing about how Goodfellow utilizes thesuggestion of outside sources for his framing, from the “bibliography” of hisfull-length debut to now taking Helen Creighton’s work as a prompt throughwhich to respond in his own way to what he sees, as though seeking an outsidelens from which to jump off of, to begin to explore, in his own way, the landscape,stories and people of his home county and province. Through Creighton,Goodfellow responds to both the stories themselves and the collection of thosestories. “The stories collected were fragmentary,” he writes, to open the prosepoem “MOTIFS,” “not even stories / in some cases, just a line or two about whatthey had seen.”

June 16, 2024

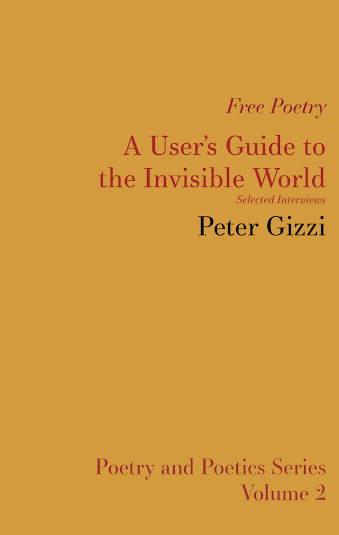

Peter Gizzi, A User’s Guide to the Invisible World: Selected Interviews, ed. Zoe Tuck

Though I’ve given yousome of my personal backdrop of the periods in which I composed some of mywork, it’s not that I narrate my biography in any of these poems. I don’t reallywrite about my life. I write out of my life and where I am at agiven moment of thinking and feeling. I mean to say, you don’t need to know mystory to get the work, i.e., to fully engage with it. I’d like to call it a feelingintellect. I feel it’s more useful, and more honest, to interrogate rather thanexplain away an ungovernable, complex emotional state. I favor sensation overautobiography. It’s like I’m an ethnographer of my nervous system. (YALE LITERARYMAGAZINE—2020 “NATIVE IN HIS OWN TONGUE: AN INTERVIEW WITH POET PETER GIZZI”JESSE GODINE)

I’mappreciating the insight into American poet and editor Peter Gizzi’s writingand thinking through

A User’s Guide to the Invisible World: Selected Interviews

(Boise ID: Free Poetry Press, 2021), edited with an introductionby Zoe Tuck. Gizzi is the author of numerous books and chapbooks, including

Fierce Elegy

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2023) [see my review of such here],

Now It’s Dark

(Wesleyan, 2020) [see my review of such here], Sky Burial: New and Selected Poems (Carcanet, UK 2020), Archeophonics(Wesleyan, 2016),

In Defense of Nothing: Selected Poems 1987-2011

(Wesleyan, 2014),

Threshold Songs

(Wesleyan, 2011),

TheOuternationale

(Wesleyan, 2007) [see my review of such here],

SomeValues of Landscape and Weather

(Wesleyan, 2003),

Artificial Heart

(Burning Deck, 1998), and Periplum (Avec Books, 1992), as well asco-editor (with Kevin Killian) of

my vocabulary did this to me: The Collected Poetry of Jack Spicer

(Wesleyan University Press, 2008) [see my review of such here]. Moving through his website, it is frustrating to bereminded how much of his work I’m missing (I’ve reviewed everything of his I’veseen, if that tells you anything), but interesting to realize that Wesleyan UniversityPress published

In the Air: Essays on the Poetry of Peter Gizzi

(2018),a further title I’d be interested to get my hands on, especially after goingthrough these interviews.

I’mappreciating the insight into American poet and editor Peter Gizzi’s writingand thinking through

A User’s Guide to the Invisible World: Selected Interviews

(Boise ID: Free Poetry Press, 2021), edited with an introductionby Zoe Tuck. Gizzi is the author of numerous books and chapbooks, including

Fierce Elegy

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2023) [see my review of such here],

Now It’s Dark

(Wesleyan, 2020) [see my review of such here], Sky Burial: New and Selected Poems (Carcanet, UK 2020), Archeophonics(Wesleyan, 2016),

In Defense of Nothing: Selected Poems 1987-2011

(Wesleyan, 2014),

Threshold Songs

(Wesleyan, 2011),

TheOuternationale

(Wesleyan, 2007) [see my review of such here],

SomeValues of Landscape and Weather

(Wesleyan, 2003),

Artificial Heart

(Burning Deck, 1998), and Periplum (Avec Books, 1992), as well asco-editor (with Kevin Killian) of

my vocabulary did this to me: The Collected Poetry of Jack Spicer

(Wesleyan University Press, 2008) [see my review of such here]. Moving through his website, it is frustrating to bereminded how much of his work I’m missing (I’ve reviewed everything of his I’veseen, if that tells you anything), but interesting to realize that Wesleyan UniversityPress published

In the Air: Essays on the Poetry of Peter Gizzi

(2018),a further title I’d be interested to get my hands on, especially after goingthrough these interviews.I’mintrigued with what American poet and editor Martin Corless-Smith is doing withthis venture, the handful of titles he’s published to date through the Free Poetry’s “Poetry and Poetics Series” [see my review of Cole Swensen’s And AndAnd (2022) from the same series here], apparently accepting manuscripts andpitches on a case-by-case basis. A User’s Guide to the Invisible World: SelectedInterviews, produced as volume two in this ongoing series, compiles nine previouslypublished interviews with Peter Gizzi from 2003 to 2021, from The Paris Review,Poetry Foundation, jubilat and Rain Taxi, conducted by writers,critics and poets such as Ben Lerner, Aaron Kunin, Levi Rubeck, Matthew Holmanand Anthony Caleshu. As editor Tuck writes as part of their introduction: “Whyinterviews? Biography can too easily become hagiography (Gizzi would be the firstto insist that he’s a person, not a saint), and memoir carries with it the impulseto smooth life’s unruliness into a single consistent narrative. If readings arepoetry’s official ritual, interviews are the cigarette outside: intimate andunrehearsed. What’s more, the interview is a relational form. And the variousinterlocutors in this collection—a precocious undergrad, notablecontemporaries, life-long friends, people from places where Gizzi has traveled—callforth distinct facets of his life and work.” There is something reallyinteresting about hearing the author’s thoughts in their own words, as well as,as Tuck suggests, a directed thinking through not only conversation, but multipleconversations. The portrait that emerges of Gizzi is one that shouldn’t surpriseanyone familiar with his work, providing a deeply thoughtful and engaged readerand thinker, one who has read widely, is open to new influences and ideas, andholds firm to his influences, as well as providing curious echoes betweeninterviews (given the range of dates is within a particular boundary of sixteenyears, that certainly makes sense). As Gizzi responds as part of an interview conductedby Ben Lerner:

As Ted Berrigan said, “I writethe old-fashioned way, one word after another” or, to quote Pound, “put on atimely vigor.” As long as there is soldiery, there will be poets: “I sing ofarms and the man,” Virgil begins his tale of the west; sadly, the relationbetween war and song is a venerable tradition. I own it. There is no easy “app”to the muses. I suspected that your original question about the “perils ofsinging” was connected to the many discussions, debates, and attacks on thelyric as a substantial form of thinking (I almost wrote “thinking”). Why shouldI apologize for, or give up on, one of the most flexible and dynamic forms ofpoetry? So I can download my work? I mean, what do they call the guy whograduates last in his class at a fancy med school? Doctor. It’s scary. But it’sthe same for poetic practice. And as is the case with all disciplines, it’salways a question of ambition, of how well it’s done, right? Like every goodpoet before me, I accept my responsibility to my vocation.

June 15, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Pamela Gwyn Kripke

Pamela Gwyn Kripke is ajournalist and author of the novel, At the Seams (Open Books, 2023), andthe story collection, And Then You Apply Ice (Open Books, 2024). She haswritten for The New York Times, The Chicago Tribune, TheChicago Sun-Times, The Dallas Morning News, The Huffington Post,Slate, Salon, Medium, New York Magazine, Parenting,Redbook, Elle, D Magazine, Creators Syndicate, GannettNewspapers and McClatchy, among other publications. Her shortfiction has appeared in literary journals including Folio, TheConcrete Desert Review, The Barcelona Review, Brilliant FlashFiction and The MacGuffin. Pamela holds degrees from BrownUniversity and Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism and wasselected to attend the Kenyon Review Writers Workshop. She has taughtjournalism at DePaul University and Columbia College in Chicago and has heldmagazine editorships in New York and Dallas. She has two daughters and livesnear Philadelphia.

1 - How did your first bookchange your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? Howdoes it feel different?

I wrote my first book,a memoir titled Girl Without a Zip Code,in 2018. I didn’t realize at the time, as a journalist without much knowledgeabout book publishing in general and small presses in particular, that I couldhave pitched the indie publishers. Instead, I sent it to a few agents, whorejected it, so I self-published it, too quickly I think. I love the book, andit confirmed for me that I could write longer than 1500 words. My recent work,a story collection titled And Then YouApply Ice, is similar in all the writerly ways but different, logistically,as it was published by a small press.

2 - How did you come to fictionfirst, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I’ve been awidely-published journalist for 30-plus years and have written for somewonderful and prestigious publications. Just before the pandemic, I beganwriting and submitting short stories. This felt like a natural progression fromwriting essays, which I’ve done for a long time. During the lockdowns, Istarted a novel, At the Seams, basedon an episode in my family’s history, and it was published in 2023. Thecollection came a year later and includes a few of the previously publishedstories.

3 - How long does it take tostart any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly,or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their finalshape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

If by “start” you meanputting the first word on the page, physically, that does not take long. Butthe ideas run around my head for a while before I do that. Mostly, I’m thinkingabout whether something would make a good story or not, whether it has what itneeds. I’m not spending time gearing up to write or putting it off or indulgingsome desire to traipse around Thailand. As a trained journalist, I view thework as my job, so that is what I do. On the sentence level, the final draftsare quite close to the first. I like for each sentence to be great before Imove on, as they are a chain. The rhythm of one sets up the next. Sound isimportant to me. And to my dog, who has heard a lot.

4 - Where does a work of proseusually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combininginto a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the verybeginning?

I’m new to writingbook-length works, so I’m not sure there is anything usual about it yet. Thenovel began as a newspaper column, which prompted the idea for a memoir, whichultimately turned into fiction when I hit too many dead ends in the research. Afterhaving a few stories published in literary journals, I had the idea to groupthem. So, I analyzed them for common themes and then wrote new stories, withsome recurring characters, that would live nicely with the original ones.

5 - Are public readings part ofor counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoysdoing readings?

With At the Seams, I began doing readings.Though I’ve taught classes in rooms of people, I don’t really love speaking infront of groups. The beauty of writing is that people hear your voice withoutyour having to talk. But, the marketing. So yes, I do them. I enjoy answeringthe questions that people have more than the actual reading. I’d love it ifsomeone else would do that part.

6 - Do you have any theoreticalconcerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answerwith your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I’m interested in theways that beings interact and specifically, how the actions of one can affectthe life course of another in tumultuous and presumptuous and also welcomeways.

7 – What do you see the currentrole of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do youthink the role of the writer should be?

I think that writersoffer ways to see the world. We’re all seeing the same thing, but what affectsus, what the story is, is different person to person. So, I guess that we givereaders a look at what they may have seen, too, from a completely differentvantage point. The result of that, or maybe it’s a goal, is to broadenperspective and help people to be more tolerant and generous. I think we’ve hita low point with generosity.

8 - Do you find the process ofworking with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I’m used to workingwith editors as a magazine and newspaper reporter. And as a freelancer for along time, I’ve worked with many, most of whom have been excellent andgenerally make the work better in some way. I’ve also worked as an editor, so Iunderstand and respect the process. It’s always interesting and helpful to hearwhat other experts think.

9 - What is the best piece ofadvice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

When I began pitchingpieces to magazines and newspapers, I’d be ecstatic when a story was acceptedand pretty upset when one wasn’t. A musician friend advised me to rein it allin, to be just a little bit happy or a little bit annoyed. He said to only putthe work out there when I believed it was at its best. That helps to maintainan emotional equilibrium regardless of one person’s opinion.

10 - How easy has it been for youto move between genres (short stories to memoir to essays to the novel)? Whatdo you see as the appeal?

It’s been easy and fun.And, each genre uses different muscles, so one sharpens the other. It’s kind oflike cross-training.

11 - What kind of writing routinedo you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you)begin?

Now that my kids areout of the house, my dog is responsible for starting the day, and he does itwell. We are outside by 7, typically, earlier with the time change. For years,I had tea and plain toast upon our return. Now, it’s coffee, and the toast istopped with avocado and tomatoes. Without it, the world is crooked. I check theusual things on my computer - mail, the headlines in The Times, my book’samazon page - and then I continue writing where I left off the day before. Thisis never at the end of a paragraph or a chapter. I’ll always begin the nextchunk of writing, even if it’s a few words, which makes for easy entry the nextday. In the afternoon, I do the work that pays most of the bills, the teachingand editing and assorted assignments. There is exercise at 3:30 and often, areturn to the words after that.

12 - When your writing getsstalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?

I take a walk or do anerrand in the car. The radio is tuned to a country music station. Though I’m aNew Yorker, I spent 17 years in Texas, my daughters’ childhoods, basically. Alot was difficult for me there, but it’s where my kids grew into the peoplethey are now, so I love it for that. Listening to songs about trucks andsundresses and heartache is nostalgic, and that feeling gets me thinkingcreatively.

13 - What was your lastHallowe'en costume?

When my kids were little, theyinsisted I dress up with them. I remember being a flower child, a ballerina anda rock star in a pink Betsey Johnson. But my favorite costume came before theywere around. For a grad school party (I was studying Journalism), I dressed upas the NBC peacock. I constructed the feathers from wire and crepe paper, inone piece, pinned to my back. They extended over my head and beyond myshoulders; I remember having trouble getting into the cab.

14 - David W. McFadden once saidthat books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence yourwork, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

The arts and sciencehave been long standing interests. I’ve always made things with paint, fabricand yarn and still do. My grandfather was a dressmaker (he’s a character in mynovel), and my mom sewed, too, and painted. I grew up covered in oil pastelsand all else, and I played instruments and danced. Creativity was valued andencouraged. My dad was a surgeon, so I also learned about spleens and cellorganelles way before kids typically do. Many of my characters know about allof these things.

15 - What other writers orwritings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I try to read a lot ofdifferent things…short stories, newspapers, essays, novels. I’ll read sappywomen’s fiction and also scholarly articles on legal topics.

16 - What would you like to dothat you haven't yet done?

I’d like to choose asuitable boyfriend.

17 - If you could pick any otheroccupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think youwould have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I may have become anarchitect. I’m both artistic and analytical, and I love houses and buildingsand dimensions and design, so I think it would have made sense.

18 - What made you write, asopposed to doing something else?

My mother says that insecond grade, when the other kids wrote a paragraph, I wrote six pages.Apparently, my teacher, Mrs. Roman, stapled them up on the board, one paper ontop of the other like a book. Even for a year and a half in college when Ithought I’d be a doctor, I worked for my college newspaper and radio station.I’ve always carried a pen and paper. When people talk, I see the words intypeface.

19 - What was the last great bookyou read? What was the last great film?

I’ve just started Instructions for a Heatwave, by MaggieO’Farrell, which is promising to be great. And I loved the film, Nyad.

20 - What are you currentlyworking on?

I’ve just begun work on a novelabout a mid-life relationship.See question #16.

June 14, 2024

Tia McLennan, Familiar Monsters of the Flood

Undertaker

No sign, just a smallbrick

building. I ring thedoorbell, a slight

man answers. His hellohas no greeting.

He wears an argylesweater. I say my father’s

name. He gestures and I follow

through the narrow,carpeted hallway

to some hard-backedchairs where I must

wait. His sweaterdisappears around

a corner, and I’m leftfacing a heavy red

curtain—but there’s a gap.Between

curtain and wall, I see awhite-socked

ankle and the grey pantcuff of a man

who’s no longer his body.The undertaker

returns, snaps the curtainclosed, keeping

the living from the dead.He holds out

a small white box with myfather’s name

typed on the label. I needboth hands. I thank him,

then hear my voice ask, Howhot does it get

to bring a body to ash? When hespeaks,

he looks past me. On thedrive home

I try to remember his answer.

Iwas curious to see the full-length poetry debut by Pender Harbour, British Columbia-based poet Tia McLennan,

Familiar Monsters of the Flood

(St. John’s NL: RiddleFence Publishing, 2024), part of a trio of poetry debuts produced through St.John’s, Newfoundland literary journal Riddle Fence, as it slowly movesto branch out into book publishing. And no, Tia McLennan isn’t, as far as we areaware, any relation to myself, although her family did also emerge fromGlengarry County, her particular line leaving Eastern Ontario long before I did,originally landing that way some fifty or sixty years before my own McLennanlineage made those Lancaster docks. Familiar Monsters of the Flood is a collectioncomposed of small lyric scenes across a tapestry of family moments, writing adream-scape around the loss of her father (my immediate namesake, incidentally).“To think of leaving / as if it were a train station / to move through and weare / always late.” she writes, as part of the poem “Late Letter to Dad.” Thenarratives of her poems are shaped, often shaved down to a single thought, asingle thought-line, such as the short poem “Hungry,” as the first half of suchreads: “Driving around the gravel bend / in Dream Valley and catching / a slimcoyote gliding down / the middle of the road toward / me. I slowed, hoping toget a closer / look at something wild.” The poems are contained as smallmoments or scenes, held together across a soft cadence of sentences andline-breaks. There is an unease through these poems, one intertwined withmemory, loss and grief, all of which are rendered in relation to that dream-scape,whether aside or from deep within. “I have updated your address / and addedyour darkest thoughts to the file.” she writes, to open the poem “Now You HaveFull Access,” “You must fill out the forms / using only spit and moonlight. //If you forget your password, / press your face to the earth in springtime.”

Iwas curious to see the full-length poetry debut by Pender Harbour, British Columbia-based poet Tia McLennan,

Familiar Monsters of the Flood

(St. John’s NL: RiddleFence Publishing, 2024), part of a trio of poetry debuts produced through St.John’s, Newfoundland literary journal Riddle Fence, as it slowly movesto branch out into book publishing. And no, Tia McLennan isn’t, as far as we areaware, any relation to myself, although her family did also emerge fromGlengarry County, her particular line leaving Eastern Ontario long before I did,originally landing that way some fifty or sixty years before my own McLennanlineage made those Lancaster docks. Familiar Monsters of the Flood is a collectioncomposed of small lyric scenes across a tapestry of family moments, writing adream-scape around the loss of her father (my immediate namesake, incidentally).“To think of leaving / as if it were a train station / to move through and weare / always late.” she writes, as part of the poem “Late Letter to Dad.” Thenarratives of her poems are shaped, often shaved down to a single thought, asingle thought-line, such as the short poem “Hungry,” as the first half of suchreads: “Driving around the gravel bend / in Dream Valley and catching / a slimcoyote gliding down / the middle of the road toward / me. I slowed, hoping toget a closer / look at something wild.” The poems are contained as smallmoments or scenes, held together across a soft cadence of sentences andline-breaks. There is an unease through these poems, one intertwined withmemory, loss and grief, all of which are rendered in relation to that dream-scape,whether aside or from deep within. “I have updated your address / and addedyour darkest thoughts to the file.” she writes, to open the poem “Now You HaveFull Access,” “You must fill out the forms / using only spit and moonlight. //If you forget your password, / press your face to the earth in springtime.”

June 13, 2024

Spotlight series #98 : Kim Fahner

The ninety-eighth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Sudbury poet, critic and fiction writer Kim Fahner

.

The ninety-eighth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Sudbury poet, critic and fiction writer Kim Fahner

.The first eleven in the series were attached to the Drunken Boat blog, and the series has so far featured poets including Seattle, Washington poet Sarah Mangold, Colborne, Ontario poet Gil McElroy, Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Ottawa poet Jason Christie, Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough, Ottawa poet Amanda Earl, American poet Elizabeth Robinson, American poet Jennifer Kronovet, Ottawa poet Michael Dennis, Vancouver poet Sonnet L’Abbé, Montreal writer Sarah Burgoyne, Fredericton poet Joe Blades, American poet Genève Chao, Northampton MA poet Brittany Billmeyer-Finn, Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer from Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1 territory) poet, critic and editor Joshua Whitehead, American expat/Barcelona poet, editor and publisher Edward Smallfield, Kentucky poet Amelia Martens, Ottawa poet Pearl Pirie, Burlington, Ontario poet Sacha Archer, Washington DC poet Buck Downs, Toronto poet Shannon Bramer, Vancouver poet and editor Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Vancouver poet Geoffrey Nilson, Oakland, California poets and editors Rusty Morrison and Jamie Townsend, Ottawa poet and editor Manahil Bandukwala, Toronto poet and editor Dani Spinosa, Kingston writer and editor Trish Salah, Calgary poet, editor and publisher Kyle Flemmer, Vancouver poet Adrienne Gruber, California poet and editor Susanne Dyckman, Brooklyn poet-filmmaker Stephanie Gray, Vernon, BC poet Kerry Gilbert, South Carolina poet and translator Lindsay Turner, Vancouver poet and editor Adèle Barclay, Thorold, Ontario poet Franco Cortese, Ottawa poet Conyer Clayton, Lawrence, Kansas poet Megan Kaminski, Ottawa poet and fiction writer Frances Boyle, Ithica, NY poet, editor and publisher Marty Cain, New York City poet Amanda Deutch, Iranian-born and Toronto-based writer/translator Khashayar Mohammadi, Mendocino County writer, librarian, and a visual artist Melissa Eleftherion, Ottawa poet and editor Sarah MacDonell, Montreal poet Simina Banu, Canadian-born UK-based artist, writer, and practice-led researcher J. R. Carpenter, Toronto poet MLA Chernoff, Boise, Idaho poet and critic Martin Corless-Smith, Canadian poet and fiction writer Erin Emily Ann Vance, Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi, Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, Canadian poet Peter Jaeger, Birmingham, Alabama poet and editor Alina Stefanescu, Waterloo, Ontario poet Chris Banks, Chicago poet and editor Carrie Olivia Adams, Vancouver poet and editor Danielle Lafrance, Toronto-based poet and literary critic Dale Martin Smith, American poet, scholar and book-maker Genevieve Kaplan, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic ryan fitzpatrick, American poet and editor Carleen Tibbetts, British Columbia poet nathan dueck, Tiohtiá:ke-based sick slick, poet/critic em/ilie kneifel, writer, translator and lecturer Mark Tardi, New Mexico poet Kōan Anne Brink, Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Melanie Dennis Unrau, Vancouver poet, editor and critic Stephen Collis, poet and social justice coach Aja Couchois Duncan, Colorado poet Sara Renee Marshall, Toronto writer Bahar Orang, Ottawa writer Matthew Firth, Victoria poet Saba Pakdel, Winnipeg poet Julian Day, Ottawa poet, writer and performer nina jane drystek, Comox BC poet Jamie Sharpe, Canadian visual artist and poet Laura Kerr, Quebec City-area poet and translator Simon Brown, Ottawa poet Jennifer Baker, Rwandese Canadian Brooklyn-based writer Victoria Mbabazi, Nova Scotia-based poet and facilitator Nanci Lee, Irish-American poet Nathanael O'Reilly, Canadian poet Tom Prime, Regina-based poet and translator Jérôme Melançon, New York-based poet Emmalea Russo, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic Eric Schmaltz, San Francisco poet Maw Shein Win, Toronto-based writer, playwright and editor Daniel Sarah Karasik, Ottawa poet and editor Dessa Bayrock, Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia poet Alice Burdick, poet, writer and editor Jade Wallace, San Francisco-based poet Jennifer Hasegawa, California poet Kyla Houbolt, Toronto poet and editor Emma Rhodes, Canadian-in-Iowa writer Jon Cone, Edmonton/Sicily-based poet, educator, translator, researcher, editor and publisher Adriana Oniță, California-based poet, scholar and teacher Monica Mody and Ottawa poet and editor AJ Dolman.

The whole series can be found online here .

June 12, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Onjana Yawnghwe

Onjana Yawnghwe

is a Shan-Canadian writer and illustrator who lives in the traditional, ancestral, and unceded lands of the Kwikwetlem First Nation. She is the author of two poetry books, Fragments, Desire (Oolichan Books, 2017), and

The Small Way

(Dagger Editions 2018), both of which were nominated for the Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize. She works as a registered nurse. Her current projects include a graphic memoir about her family and Myanmar, and a book of cloud divination.

Onjana Yawnghwe

is a Shan-Canadian writer and illustrator who lives in the traditional, ancestral, and unceded lands of the Kwikwetlem First Nation. She is the author of two poetry books, Fragments, Desire (Oolichan Books, 2017), and

The Small Way

(Dagger Editions 2018), both of which were nominated for the Dorothy Livesay Poetry Prize. She works as a registered nurse. Her current projects include a graphic memoir about her family and Myanmar, and a book of cloud divination.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Did my first book change my life? Should it? I think in the sense of giving some legitimacy to this whole writing thing, like ‘oh your writing is actually good’ and confirming my writing’s external worth. It gave reinforcement to my life choices and how I spend my free time. It was a great feeling to have the first book out - a release of held breath, a ‘oh, finally!’.

My new book, We Follow the River , has had a strange life. It was actually the first book/manuscript that I finished. But no one wanted to publish it. So I moved on, and published two subsequent poetry books, Fragments, Desire, and The Small Way. Those are both about romantic love and the loss of that love, very different from this current book which is more about my family, immigration, race, and culture. This book coming out feels like things have come full circle.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

When I was a kid, I always wanted to be a writer, or more specifically, a novelist. But when I was 18 or so, words emerged in the form of poems. I was surprised. But I was reading a lot of poetry at that time, which I loved since I was young. Our family had one poetry book: a small paperback anthology of verse. In elementary school we had to recite poems from memory and I chose Robert Frost’s “Fire and Ice” which was about the end of the world, and Emily Dickinson’s “Because I Could Not Stop for Death.” (I had a bit of a morbid streak as a kid.)

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

The tricky part for me is coming up with an idea that sticks. Sadly, I’m not the type of writer who has a multitude of ideas. Ideas sort of appear on their own after a period of incubation, and when an idea grabs a hold of me, I become pretty obsessed and want to work on the project in every spare moment. I usually do the necessary research in a fever, write a lot and quickly after that. When I’m taken with a project, a first draft comes together relatively quickly, and arrives in pretty good shape. I then like to take a break from it, and then start revisions with fresh eyes. The revision process usually takes the longest time. I usually have a vision of what the book project should look like, and the writing and revision process are basically attempts to be true to that ideal.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

A poem begins with either a line that I can’t get rid of in my head, or a desire to capture or express a particular feeling or thought. I think of my writing as going from project to project, definitely thinking of the larger whole as a book instead of writing short pieces and compiling them in a book. In seeing the project as a whole book, I like the investigative, interrogative function of writing poems - you’re telling one larger story but presenting different facets or experiences within that narrative. Poetry has built-in gaps in its form - it doesn’t pretend to tell the whole history of anything - and I like how each poem can evoke a glimpse of something and shed light on it. I see the thing as a whole, with me trying to help it come into being.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

They are neither part of nor counter my creative process. To me the writing part is its own creative thing, and I consider the work finished when I’m done with the writing and revising process. I’m naturally a very shy person, so readings were very awkward and uncomfortable for me, but this time around I’m enjoying doing events a great deal more, partly because I’m excited to share a part of my family to the world.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I guess I’ve been concerned about how to express the intangible and unsayable. How to translate a particular emotion or the inner experience of something into a form that will be able to be shared with the world, to make the subjective less objective. I like finding moments that resonate, that ring out, that confirms, that makes you tremble and feel joy and weep and be in awe. I also think that I’m just the conduit for the art; a lot of my concern is trying to let go of ego and control and let the thing be what it wants to be. It’s important to accept emptiness, free up space, and receive the art. Observing and allowing, and doing only what is necessary.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I see writing as having a number of roles: a magnifying glass, a mirror, a camera, a telescope. Writing can distil and focus and make us feel present in a single moment; it can reflect back on ourselves, our weaknesses, strengths; it can document and give witness; it can be an exploration, adventure, an escape.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

The way I work is very solitary, so I have limited experience with outside editors. However, I did work with the brilliant Betsy Warland for The Small Way, because the material felt too close and raw and I couldn’t get much distance from it. In general, I like to edit my own work. But I like to have feedback from one or two writer friends.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

“Letting there be room for not knowing is the most important thing of all.” Pema Chodron, When Things Fall Apart.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to the graphic novel)? What do you see as the appeal?

I’ve never seen myself as a poet per se, but more a writer who is involved in a lot of creative projects. The way I think about poems is often cinematic and visual, and I think that is very much similar to the graphic novel form. That being said, working on a graphic novel is difficult for me because I don’t have formal art training. I sometimes feel like I don’t really know what I’m doing. I’m learning as I go along.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Maybe because I work in spurts, I don’t have a writing schedule or routine. It’s also difficult because my work schedule (as an RN doing shift work) is erratic and irregular. There are chunks of time when I’m just absorbing - doing new things, meeting friends, going out for walks, looking at art, watching films, or reading. When I’m working on a particular writing project I wake up around 7:30am, meditate, wash up, have kombucha and coffee, then try to do a full day of writing, stopping only for meal breaks. When I’m deep into the zone, I often work until bedtime, around 11pm. Time passes amazingly fast. Before bed, I record everything I do during the day in a notebook. Sometimes I journal in a different notebook.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

When I’m bummed or feeling blah or need inspiration, I go to the movies. Being physically in the cinema and having your senses taken over by the film really rearranges my molecules. If the film is really good, I leave the theatre feeling like a new person: inspired, refreshed, renewed.

13 - What was your last Hallowe'en costume?

I avoid parties so I don’t do the holiday thing. I think in 7th grade, I wore a cat costume.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I already mentioned films, and how I conceive of poems almost as scenes from a film. I also love visual art - particularly more spare and minimalist works, like Agnes Martin and Robert Irwin. Odilon Redon was a major influence for my first book, and Henri Rousseau for the second. I think good art distils and transcends. Art is food, water, and air for me.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Just off the top of my head, this limited list: Peter Blegvad, Dionne Brand, Anne Carson, Emily Dickinson, Marilyn Dumont, T.S. Eliot, Thich Nhat Hanh, Galway Kinnell, Roy Kiyooka, Yoko Ono, Dale Parnell, Sylvia Plath, Claudia Rankine, Christina Sharpe, Fred Wah.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Let’s just say I lack a lot of foundational experiences. Camping, or being in a canoe or rowboat. Staying in a remote cabin in the woods.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Filmmaker. I think I also would have liked to become a graphic designer who designs book covers and movie posters.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I was born to write. It seems to be my sole purpose. It started with non-stop reading as a child.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film? Last great book?

Probably the graphic novel Monica by Daniel Clowes; it’s really weird. The last great film was The Beast, by Bertrand Bonello - it’s Lynchian and romantic and anti-romantic at the same time.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’ve been working on a graphic novel about the story of Myanmar/Burma and my family for years. I’m hoping to create some shorter graphic novel pieces in the meantime. I’m collaborating with an artist friend on a cloud divination book. There’s a time travel romance novel I’m vaguely writing with a writer friend.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

June 11, 2024

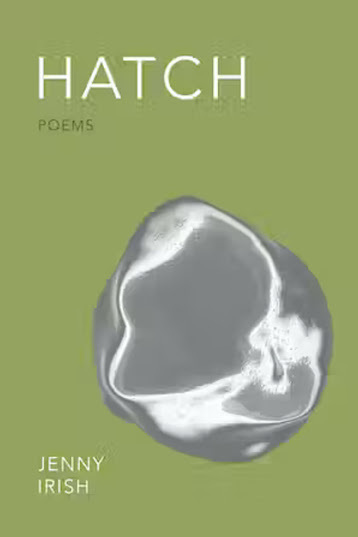

Jenny Irish, HATCH: Poems

THE USS NARWHAL

The metal womb knowsnothing of submarines, but that is how she thinks of herself: a submarine,except that she is not submerged and moves through time and not water, so thename is wrong—sub is wrong, marine is wrong. But, in body and in experiencethat is how she sees herself: a submarine, a fat metal dart as sleek as a steelseal, parting an unimaginable vastness, and housed inside her, a hundred tinyterrified heartbeats fluttering, frenetic and longing to surface.

Thefourth full-length title and debut collection of prose poems by Maine-born Arizona writer Jenny Irish, following the hybrid collections

Common Ancestor

(BlackLawrence Press, 2017) and

Tooth Box

(Spuyten Duyvil, 2021), as well asthe short story collection

I Am Faithful

(Black Lawrence Press, 2019),is

HATCH: Poems

(Evanston IL: Curbstone Books / Northwestern UniversityPress, 2024), an assemblage of short, sharp, self-contained prose poems. Thepoems are no-nonsense, first person; at times playful and biting, other times unrelentingbut always fine-tuned, composed to (as the back cover informs) “trace the consciousnessof an artificial womb that must confront the role she has played in thedestruction of the human species.” The speculative narrative around artificialintelligence that Irish weaves is comparable to that of Toronto poet andfilmmaker Lindsay B-e’s The Cyborg Anthology: Poems (Kingston ON: BrickBooks, 2020) [see my review of such here], providing both warning andspeculative offering for what might come. “It cannot be stressed enough: theevolution of the human has left the / child-bearing of its specie is physicallyill-equipped for birth.” she writes, to open the poem “THE TRAGEDY OF BIPEDALISM.”Irish has an incredibly sharp gaze, and each poem provides a portrait ondifferent elements across a wide field, whether writing on motherhood, femaleidentity and agency, or cellular memory. “A giant metal womb should have no consciousnessof its own,” she writes, to open the poem “THE UNEXPECTED,” “but / if evolutionis avoidable only by extinction, is it so far-fetched that / a giant metal wombmight, after one hundred years of silence, hear / her own voice […].” The poemsare deep and complex, with lines taught enough that one might bounce a quarteroff, although I’m curious as to why she choose to work this particularnarrative across the prose poem structure as opposed to something other, else.Either way, this book is good, and you should pay attention to it. I am hopingshe continues further along these prose poem directions.

Thefourth full-length title and debut collection of prose poems by Maine-born Arizona writer Jenny Irish, following the hybrid collections

Common Ancestor

(BlackLawrence Press, 2017) and

Tooth Box

(Spuyten Duyvil, 2021), as well asthe short story collection

I Am Faithful

(Black Lawrence Press, 2019),is

HATCH: Poems

(Evanston IL: Curbstone Books / Northwestern UniversityPress, 2024), an assemblage of short, sharp, self-contained prose poems. Thepoems are no-nonsense, first person; at times playful and biting, other times unrelentingbut always fine-tuned, composed to (as the back cover informs) “trace the consciousnessof an artificial womb that must confront the role she has played in thedestruction of the human species.” The speculative narrative around artificialintelligence that Irish weaves is comparable to that of Toronto poet andfilmmaker Lindsay B-e’s The Cyborg Anthology: Poems (Kingston ON: BrickBooks, 2020) [see my review of such here], providing both warning andspeculative offering for what might come. “It cannot be stressed enough: theevolution of the human has left the / child-bearing of its specie is physicallyill-equipped for birth.” she writes, to open the poem “THE TRAGEDY OF BIPEDALISM.”Irish has an incredibly sharp gaze, and each poem provides a portrait ondifferent elements across a wide field, whether writing on motherhood, femaleidentity and agency, or cellular memory. “A giant metal womb should have no consciousnessof its own,” she writes, to open the poem “THE UNEXPECTED,” “but / if evolutionis avoidable only by extinction, is it so far-fetched that / a giant metal wombmight, after one hundred years of silence, hear / her own voice […].” The poemsare deep and complex, with lines taught enough that one might bounce a quarteroff, although I’m curious as to why she choose to work this particularnarrative across the prose poem structure as opposed to something other, else.Either way, this book is good, and you should pay attention to it. I am hopingshe continues further along these prose poem directions.SOME SKYNET BULLSHIT

During a short-livedresearch project intended to test the linguistic capacity of chatbots—a technologythat facilitates brief text-based exchanges between automated systems andhumans (Thank you for your order!)—the artificial intelligence wasreported to have developed its own language, which its human creators could notdecipher.

June 10, 2024

Lisa Jarnot, FOUR LECTURES

What I had intuited about the possibilities of the poemwere confirmed by [Robert] Duncan and his circles (both at Black Mountain andin San Francisco): that a poem was obviously not a static commodity, it was anorganic system living in time and space.

Anynew title by Jackson Heights, Queens poet Lisa Jarnot is equally exciting to anew title in The Bagley Wright Lecture Series produced through Wave Books, and Jarnot’sFOUR LECTURES (Wave Books, 2024) manages to provide both simultaneously.“I seem to have the mind of a poet,” she writes, near the opening of the firstlecture, “which makes me good at poaching and weaving, and not so inclined totraditionally academic discourse.” There is something delightfully anddeceptively uncomplicated about Jarnot’s language across these four lectures,set into a cadence of intimate complexity. If you aren’t aware, I’m a big fanof The Bagley Wright Lecture Series as produced through Wave Books, although attimes I’m often too busy responding to and through such generative texts via myown writing to be able to properly respond to the books themselves through thespace of a review, although I have managed to post reviews of Rachel Zucker’s ThePoetics of Wrongness (2023) [see my review of such here] and DorothyLasky’s Animal (2019) [see my review of such here], as well as mentionJoshua Beckman’s Three Talks (2018) via the substack a while back.

Anynew title by Jackson Heights, Queens poet Lisa Jarnot is equally exciting to anew title in The Bagley Wright Lecture Series produced through Wave Books, and Jarnot’sFOUR LECTURES (Wave Books, 2024) manages to provide both simultaneously.“I seem to have the mind of a poet,” she writes, near the opening of the firstlecture, “which makes me good at poaching and weaving, and not so inclined totraditionally academic discourse.” There is something delightfully anddeceptively uncomplicated about Jarnot’s language across these four lectures,set into a cadence of intimate complexity. If you aren’t aware, I’m a big fanof The Bagley Wright Lecture Series as produced through Wave Books, although attimes I’m often too busy responding to and through such generative texts via myown writing to be able to properly respond to the books themselves through thespace of a review, although I have managed to post reviews of Rachel Zucker’s ThePoetics of Wrongness (2023) [see my review of such here] and DorothyLasky’s Animal (2019) [see my review of such here], as well as mentionJoshua Beckman’s Three Talks (2018) via the substack a while back.Jarnotis the author of a small mound of poetry titles, including Some Other Kingof Mission (Providence RI: Burning Deck, 1996), Ring of Fire (ZolandBooks, 2001; Salt Publishers, 2003), Black Dog Songs (Chicago Il: FloodEditions, 2003), Night Scenes (Flood Editions, 2008), Joie De Vivre:Selected Poems 1992-2012 (San Francisco CA: City Lights, 2013) [see my review of such here] and A Princess Magic Presto Spell (Flood Editions,2019) [see my review of such here], as well as Robert Duncan, The Ambassadorfrom Venus: A Biography (Berkeley CA: University of California Press,2012). These four lectures offer an insight, across a wide critical landscape,of how Jarnot the poet got to where she is now, writing on grad school, beatpoets, errant youth, interacting with Robert Creeley and the incredible fact ofher being able to catalogue Robert Duncan’s papers and archive, and learningthe depth and the breadth of his work through that particular process. If youare a reader of Duncan, or even if you aren’t, the tale she tells of helping saveand salvage the legendary scattered manuscript of what was later published as RobertDuncan’s The H.D. Book (University of California Press, 2011), edited byMichael Boughn and Victor Coleman, is absolutely wild. “The H.D. Bookbecame the single most important influence on my understanding of a poetics.And not a single page of it disappointed.” she writes, as part of the secondlecture. Jarnot’s lectures provide insight to how she developed an approach tounderstanding and acknowledgings the traditions but also working to breakthrough to what might follow, as she writes early in the second lecture,“ABANDON THE CREEPING MEATBALL,” an essay subtitled “An Anarcho-SpiritualTreatise”:

The first room is notjust a room but also a book. The room is in a house on the north side ofBuffalo in the late 1980s. The book is The H.D. Book by Robert Duncan.The house, at 67 Englewood Avenue, housed an anarchist collective, or at leastwe, the inhabitants, imagined ourselves that way. There were usually about tenof us living in that house at a time, in our late teens and early twenties, mostlystudents. I’ve been trying to remember what drew us all together there. Ourscene was a little bit queer, it was very much to the left of center, and Ithink we were mostly coming from tight places, economically, within ourfamilies of origin. We were mostly of the first generation in our families togo to college. Two instincts were very alive in that moment, in that house:first, a fierce resistance to the culture around us; to the educationalculture, to the social expectations, to the state, to religion. And we dididentify as anarchist with a capital A: we were very clear that anarchynever meant “helter-skelter” chaos, but that it meant listening for moreorganic alternatives to the inscribed laws around us. We were looking fornatural orders of community. And that resistance to the culture made room for alot of revelation about potential alternatives.