Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 45

July 29, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Kendra Sullivan

KendraSullivan

[photo credit: Laila Stevens] is a poet, public artist, and activistscholar. She is the Director of the Center for the Humanities at the CUNY Graduate Center; Co-director of the NYC Climate Justice Hub, a radicalpartnership between CUNY and New York City Environmental Justice Alliance toadvance frontline-led climate justice research, teaching, and policy;Co-director of Women’s Studies Quarterly; and Publisher of Lost & Found:The CUNY Poetics Document Initiative. She makes public art addressingwaterfront access and equity issues in cities around the world and haspublished her writing on art, ecology, and engagement widely. She is theco-founder of the Sunview Luncheonette, a cooperative arts venue in Greenpoint,Brooklyn; and a member of Mare Liberum, a collective of artists, designers, andboatbuilders imagining other ways to inhabit coastal cities. Her work has beensupported by grants, awards, and fellowships from the Andrew W. MellonFoundation, the Waverley Street Foundation, the Graham Foundation, the MontelloFoundation, the Engaging the Senses Foundation, the Rauschenberg Foundation,the Blue Mountain Center, and the T.S. Eliot House, among many others. Herbooks of poetry include

Zero Point Dream Poems

(Doublecross Press) and

Reps

(Ugly Duckling Presse).

KendraSullivan

[photo credit: Laila Stevens] is a poet, public artist, and activistscholar. She is the Director of the Center for the Humanities at the CUNY Graduate Center; Co-director of the NYC Climate Justice Hub, a radicalpartnership between CUNY and New York City Environmental Justice Alliance toadvance frontline-led climate justice research, teaching, and policy;Co-director of Women’s Studies Quarterly; and Publisher of Lost & Found:The CUNY Poetics Document Initiative. She makes public art addressingwaterfront access and equity issues in cities around the world and haspublished her writing on art, ecology, and engagement widely. She is theco-founder of the Sunview Luncheonette, a cooperative arts venue in Greenpoint,Brooklyn; and a member of Mare Liberum, a collective of artists, designers, andboatbuilders imagining other ways to inhabit coastal cities. Her work has beensupported by grants, awards, and fellowships from the Andrew W. MellonFoundation, the Waverley Street Foundation, the Graham Foundation, the MontelloFoundation, the Engaging the Senses Foundation, the Rauschenberg Foundation,the Blue Mountain Center, and the T.S. Eliot House, among many others. Herbooks of poetry include

Zero Point Dream Poems

(Doublecross Press) and

Reps

(Ugly Duckling Presse).1- How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent workcompare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Thisis my first book! Though I simultaneously, or nearly so, published abook-length dos-a-dos with DoubleCross called Zero Point Dream Poems,after Nawal El Saadawi’s Woman at Point Zero. I produce a lot butpublish a little. In my opinion, writing is socially produced and producessocialites. Publications need to be brought into the world by the right peopleby the right press at the best time if they are to be received as meaningfullyas possible by the right reading public. While this is not always probable oreven possible, working with MC Hyland and Anna Gurton-Wachter at DoubleCross in2023 and Dan Owens, Kyra Simone, Serena Solin, and Milo Wippermann at UDP in2024 checked all these boxes.

Morebroadly, I break my weekly habit tracker down into three categories: being,doing, and making. My first book has shifted my way of being most: it’s afeeling state or felt sense of having landed somewhere. Or maybe it’s the feltsense of having finally cast off, the feeling state of “far out” or “offshore,”where, paradoxically or not, I feel most grounded. That felt sense is thebiggest shift.

2- How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Thedesire to write fiction is what propels me as a writer. Poetry that plays withnarrative comes out when I sit down to write. It’s the shape my thinking takeson the page. I’m also an academic writer. But even as a scholar writingscholarly prose, I write associatively, sentence by sentence, without a roadmapor an outline. Whether I’m writing poetry or critical theory, language is likea stone pathway that precedes my arrival on the scene of the text. Step bystep. I follow the stones. I don’t know where I’m going or when I’llstop.

3- How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does yourwriting initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appearlooking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copiousnotes?

Writingis like precipitation in my life. Sometimes the weather is too wet. Sometimestoo dry. Most of the time there is too much rain and too little containment:flood. Some of the time there is too little rain and too much thirst: drought.Sometimes the weather meets the needs of its immediate terrain: poetry!

4- Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an authorof short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you workingon a "book" from the very beginning?

I’ma project-based poet and my books reflect that fact. A conceit becomes apreoccupation that I iterate until I’ve cycled through all possible variationson a theme or method available to me. The circuit of experimentation eventuallycompletes itself and I begin to edit. Many times, during the editing process,subcircuits present themselves. Fractal arguments and counterarguments opendoors into doors.

5- Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you thesort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Onlysince having a child! Recently, my friend said to me that when she had a childshe was able to forgive herself for existing. This is true for me, too. Thereare many societal reasons this is a very distressing sentiment! A subject for ascholarly essay or book, to be sure. But nonetheless, when I gave birth, Iforgave myself for existing, and as a direct or indirect result, began to enjoyreading in public.

6- Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds ofquestions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think thecurrent questions are?

Somany! Too many to list, but here are some main preoccupations.

Isempathy a virtue that affords greater social cohesion or a narcissisticexpression susceptible to political exploitation? What is compassion and how dowe act appropriately on its injunctions in contemporary life? How are we tolive “the good life,” by which I mean a values-driven life that makes room forthe possibility of joy, in the age of climate breakdown?

Whoam I; and who are you; and who are we; and where do we begin and end inrelation to the total environment, if at all?

BecauseI work in the knowledge sector, a lot of my poetry is concerned with theideological and material conditions of knowledge production and circulation.I’m interested in knowledge economies in general, or where and how knowledge ismade, received, and interpolated, and by whom. I’m interested in the wayssituated, lived, or embodied knowledge is honored (or not) in mainstreamscholarly discourses and policy development. I’m interested in research, or howhumans learn what they need to know in order to live well and remove barriersto collective wellbeing. And I’m interested in meaning-making, or how humansweave together their personal and social lives through deeply contextual,cultural, community-led, and value-laden activities, like for instance, poetry!

7– What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Dothey even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Inmy poems, I often ask how we can loosen the strictures of Western, empiricalknowledge regimes without descending into a pit of relativisms that renderthought vulnerable to conspiracy, misinformation, and polarization. Can poetryhelp us live with integrity while accepting uncertainty? Certainly. Can wecritique patriarchal scientific methodologies while embracing the fruits ofscientific study and analysis? Yes, I think so. Does poetry contribute toefforts led by theorists working on the ground, in the streets, or in theacademy who advance situated, embodied, and author-saturated understandings ofthe worlds we inherited alongside the worlds we want to pass along? Totally.Are phenomenological understandings of meaning-making inherently feminist? Subversive?Dissident? Is poetry research? What would it mean to read it as such? I don’tknow!

8- Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult oressential (or both)?

Helpful!The more dialogic the writing and editing process, which are continuous andcoextensive in my practice, the more faceted the crystallized artifact of thatinteraction becomes.

9- What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to youdirectly)?

Writein community. Deepen your relationship to your existing communities. Seek outnew communities to be, do, and make with and for. Weave yourself into ever morecomplicated social fabrics with your words.

I’vejust realized I didn’t really answer your question. That’s my advice.

Advicethat I recently heard and really appreciated is to ask yourself everyday, “whatam I walking toward and what am I walking away from?” Step by step, youcan get “there” from “here,” wherever here and there are for you. Walking maybe an alienating verb for some, since it implies a baseline of personalmobility and/or environmental safety that is not universal by any stretch. Soif that’s your experience, maybe you could swap “walking” out withanother verb that resonates with your intrinsic motivations, like“writing.”

10- How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to art tocritical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

Iam a poet, a scholar, and an artist. My art practice is what is sometimestermed social sculpture. I build boats, teach people to build boats, and getpeople out on local bodies of water to talk about environmental ecologies andeconomies as part of a collective called Mare Liberum. I like to think thatbuilding boats has prepared me to move between genres: land and sea, public artand activist scholarship, academic administration and poetry creation. It’s acontinuum of practice.

11- What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one?How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Ihave a small child who has more power over my daily routine than the sun andmoon could ever hope to! I have no routine. I write whenever I find aminute.

12- When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack ofa better word) inspiration?

Iread. I wait. I exercise. I play. I work. I get outside.

13- What fragrance reminds you of home?

Whata lovely question! It reminds of the PJ Harvey song, “You Said Something,” from Stories from the City. Stories from the Sea. While looking at Manhattan froma rooftop in Brooklyn she sings about the “smells of our homelands.” This linealways reminds me that I don’t know where home is: the city (where I live) orthe seaside (where I grew up). Depending on my mood, the smells of my homelandare either trash & heat (rising from asphalt) or salt & sulfur(released by dead and dying plants in the marshland). Home is such a scaryplace for so many. I am privileged to love my homes.

14- David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there anyother forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visualart?

Allof the above! I would add that institution building and institutionalethnography both layer my thinking about poetry creation. The practice ofinstitutional ethnography was developed by Canadian sociologist Dorothy J.Smith. It’s a research methodology that aims to describe how individualbehaviors, beliefs, and activities, taken en masse, give form to the social.This way of looking at things helps me understand the coordinated doing,making, and working across scenes, sectors, and geosocial spaces that give riseto poetry as an institution. Counterinstitution is actually a more capaciousand less contestable term to describe the work of poetry in the world. AmmielAlcalay’s motto for Lost & Found is “follow the person.” I think ofcounterinstitutional ethnography, and I’m not sure he’d agree with me here, of“following the people,” to understand poetry and its operations at scale.

15- What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply yourlife outside of your work?

Toomany to name! I’ll give a shout out to my Lost & Found poetry fam.Ammiel, Sampson Starkweather, Stephon Lawrence, Joseph Caceres, Tonya Foster,Coco Fitterman, Daisy Atterbury, Irish Cushing, Zohra Saed, Oyku Tenken, Miriam Atkin, and Marine Cournet. I’ll also shout out my Geopetics working group:Celina Su, Sahar Romani, Mónica de la Torre, Richa Nagar, and Kahina Meziant.And my poet.mamas listserve!

16- What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Justkeep writing, publishing, performing, and archiving. Write continuously, likeDiane di Prima. Publish continuously, like Alice Notley. Perform continuously,like Mariposa Fernandez. Archive and activate/preserve archives continuously,like Lois Elaine Griffith. I’d also like to focus on a daily visual log, likeEtel Adnan. I was trained as a painter and I’d like to paint more like I brushmy teeth, every day, as a kind of maintenance. (Naming aspirations here; notmaking comparisons between myself and these phenomenal beings!)

17- If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or,alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been awriter?

Iwork my dream job. Even so, I have a fantasy that one day I’ll go to Yale’sforestry school.

18- What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

It’spossible that I began writing seriously after 9-11 in NYC because painting andboat making, my two main visual arts practices, required too much storage.Poems don’t take up any space; on the contrary, they create space.

19- What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

RichaNagar’s Relearning the World through Radical Vulnerability. Alice Diop’sSaint Omer. Both, to me, in part, develop methods for buildingsolidarity with near and far “others” without the crutch ofidentification.

20- What are you currently working on?

Aninstitutional ethnography of CUNY called Uneven Ground: Making the PublicUniversity Work Anywhere People Gather, Learn, and Grow.

July 28, 2024

Kevin Prufer, The Fears

I keep returning to theimage of a kitten

asleep in the engine

As a way of understanding

the history of mycountry.

So warm under the car’shood,

the hidden sweetness inthe dark machinery.

+

Start the car.

+

[The sound the kittenmakes.]

+

Happy slaves on a lazyafternoon

sleeping in the shadow ofhay bales.

A banjo lying in the sun.

Stolen apples.

A lithograph on the wallin my father’s office:

The sweet ol’ summahtime.(“Automotive”)

I’mcurrently working my way through American poet Kevin Prufer’s ninth poetrycollection (and the first I’ve seen of his), The Fears (Port TownsendWA: Copper Canyon Press, 2023), following titles such as National Anthem(2008), In a Beautiful Country (2011), Churches (2014), How He Loved Them (2018) and The Art of Fiction (2021). There’s ameandering sharpness to these pieces, a movement that is incredibly precise,reminiscent of the late Toronto poet David Donnell for a kind of conversational tone that moves and sways andcoheres in ways that are almost startling (although the language feels moreexact than Donnell). I see this comparison most obvious in the rhythms of poemssuch as “W.H. Auden’s ‘The Fall of Rome’,” that opens with a pacing and aconversational kind of ease entirely comparable with Donnell’s catalogue:

In the final lines of hisgreat poem “The Fall of Rome,”

Auden describes

not the facts

of the late Empire’s fall,

but distant herds of reindeer

moving quickly and silently

across vast expanses of goldenmoss.

We don’t know

where those herds are,

only that theyseem impossibly

far from the troubles ofmen,

not mindless but

beyond mind,

uncountable, twilit, inhuman,

unconcerned with the failuresof empires.

Prufer’spoems begin with a moment, and then work to articulate every angle of it, unableto move beyond until every particle is properly considered. “He had becomefascinated by the way / excellent poems sometimes failed to hold together,” Prufer’stitle poem begins, “in ways he expected them to. / That is, / a poem, like agreat mind at work / on an unsolvable problem, / might by necessity / meander […].”He manages his meandering in such deliberate motions, without a word or thoughtout of place, even through a sequence of explorations through and aroundlanguage, perception and memory. “but Greek loneliness,” he writes, as part ofthe poem “The Greek Gods,” “seems closer to explaining / the forces thatbrought us here / and make me wander / the hospital skybridges / late at night,/ watching that same McDonald’s blinking / into darkness.” Prufer managesmeditative stretches that rhythmically extend and hold across great distances, andsuch intimacy through asking some rather big questions of existence and being, propelledthrough the pacing of what he describes as his fears; and his fears, one mightsay, are legion.

Prufer’spoems begin with a moment, and then work to articulate every angle of it, unableto move beyond until every particle is properly considered. “He had becomefascinated by the way / excellent poems sometimes failed to hold together,” Prufer’stitle poem begins, “in ways he expected them to. / That is, / a poem, like agreat mind at work / on an unsolvable problem, / might by necessity / meander […].”He manages his meandering in such deliberate motions, without a word or thoughtout of place, even through a sequence of explorations through and aroundlanguage, perception and memory. “but Greek loneliness,” he writes, as part ofthe poem “The Greek Gods,” “seems closer to explaining / the forces thatbrought us here / and make me wander / the hospital skybridges / late at night,/ watching that same McDonald’s blinking / into darkness.” Prufer managesmeditative stretches that rhythmically extend and hold across great distances, andsuch intimacy through asking some rather big questions of existence and being, propelledthrough the pacing of what he describes as his fears; and his fears, one mightsay, are legion.

July 27, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with K.R. Segriff

K.R. Segriff

(she/her) is a poet and filmmaker. She is stunningly awkwardbut has an excellent game face. Her work has appeared in Greensboro Review,The Malahat Review, Prism International, and Best Canadian Poetry,among others. She won The Edinburgh Story Prize, The London Independent StoryPrize, The Bumblebee Prize for Flash Fiction, The Space and Time Magazine IronWriter Award, and The Connor Prize for Poetry. Her first collection of short stories was published by Riddle Fence Debuts in 2024. She lives in Toronto withher spouse and three children where they are known as ‘those neighbours’ andrarely cut their grass.

K.R. Segriff

(she/her) is a poet and filmmaker. She is stunningly awkwardbut has an excellent game face. Her work has appeared in Greensboro Review,The Malahat Review, Prism International, and Best Canadian Poetry,among others. She won The Edinburgh Story Prize, The London Independent StoryPrize, The Bumblebee Prize for Flash Fiction, The Space and Time Magazine IronWriter Award, and The Connor Prize for Poetry. Her first collection of short stories was published by Riddle Fence Debuts in 2024. She lives in Toronto withher spouse and three children where they are known as ‘those neighbours’ andrarely cut their grass. 1 - How did your first bookchange your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? Howdoes it feel different?

I feel like, "Well, ifnothing else, there is a book on my shelf with my name on it." It's likebeing one step closer to a good death. It also opens up a fantasy world wheresometime, 60 years from now, some rando who is not even born yet might happenupon my book, read the stories, have a laugh or some deep thought, and, in thatsmall way, I will have influenced the world from my grave. This is an excellentand creepy thought. I try not to think how there will probably be no books in60 years. No. That is not part of my fantasy world. Also, it was pretty coolwhen I was at my book launch with Riddle Fence and, instead of reading off myphone or fumbling around with a stack of crumpled papers, I just pulled out mybook, like some suave fox, opened the book to the appropriate page, and read.It felt pretty legit. It was not me who thought of this, though. One of theother authors there who noticed that feature of book-havery. I forget if it wasJennifer Newhook, Tia McLennan, or Danielle Devereaux. Whoever she was, she wasa genius, and you should read her book too.

2 - How did you come tofiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I do write poetry, but it'shard to do it sometimes without feeling a little pretentious. I have anunreasonable poetry prejudice that was drilled into my head at an early age bymy poetry-hating dad. So perhaps, in that way, I write poetry as a form of adolescentrebellion. Actually, I have a book of poetry that I am currently shoppingaround, so maybe I should stop talking so much crap about poetry. Non-fictionis just off for me. I hate to be constrained by the truth.

3 - How long does it take tostart any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly,or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their finalshape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It usually starts with aquote or a line. Then, I build a mind map around it. I write lots of emails tomyself about random thoughts, and I put the word "Miliza" in thesubject line. That is my secret code that the email is about a story. So when Iam ready to write, I search all the "Miliza Mail" for my ideathreads. Miliza is my grandmother's childhood nickname. I don't know why Ichose that. She was not much of a writer. She let me read her diary once. Itwas mainly about the weather and the people she met in town. Super boring.Anyways. Once a Miliza thread gets too long, I start to get stressed out, so Iget out these colored cue cards and write out the ideas. Then I arrange them onthe dining room table into some sort of order. Then, I type that into my laptopas an outline. Then I fill in the gaps. That's the hardest part. Filling in thosedamn gaps. The easy part is the cue cards. The glue that holds them together?That's the real challenge. But the cue card thing is for longer projects. Forflash fiction and shorter pieces, I havebeen known to sit down and bang it out in one sitting. I guess I am smartenough to keep track of all the moving pieces for shorter pieces, but I'm lostfor anything over 1500 words. That's when cue cards hit the scene.

4 - Where does a work offiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end upcombining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" fromthe very beginning?

I am also a filmmaker, somost of my stories start with an image or a line of dialogue, and I build thestory around it. I commute to my day job on my bike, and during that time, Ican think. I suck on stories like hard candy, dissolving them slowly over daysin my mind. I often stop on the side of the road and type little fragments intomy phone. The problem is that sometimes, they are hard to decode later. I havelearned to write out my thoughts like I am spelling them for an 8-year-old.Otherwise, I return to them and think, ‘WTFis this?’ I still have something onmy phone that says, "Moon lungs crash teeth." Sometimes, I stillwonder what I was thinking when I wrote that.

5 - Are public readings partof or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoysdoing readings?

I went to an arts highschool. I love performance. Much of the stuff I write is meant to be read aloudon a stage, by a campfire, or alone in my living room. I perform everything formyself early in the edits. Bouncing it off the walls gives me a differentperspective. It lets me see the holes and the laggy bits. I think the bestwriting sounds as good as it looks. I also enjoy the experience of sharingstories live. It's timeless. It's lizard-brain stuff. I think, on some level,live storytelling is a human need. To be honest, a lot of why I write stuff isso I can have an excuse to get together in some sticky-floored, dimly lit spaceand legitimately hang out with other weirdos, just sharing our words andletting it all hang out.

6 - Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are youtrying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

I think, ironically, fictionwriting is a search for what is real. It's about trying to dig into the heartof our existence and discover what is truly common to all of us, even if weexpress it in disparate ways. It's trying to figure out what drives characters,trying to understand them by putting them into novel situations. Fiction is athought experiment of the human experience. The fantasy teaches us aboutreality. For me, it's driving toward some universal acceptance. A lot of mycharacters are rough around the edges. But understanding what motivates themmakes me love them even when they misbehave. It also makes me forgive myself,in a way, for times I have personally misbehaved. When I understand mycharacters, I understand my most hated neighbors a little better. Sometimes, Iam my own most hated neighbor. So, it can be therapeutic.

7 – What do you see thecurrent role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? Whatdo you think the role of the writer should be?

I think writers need to be awareof what they are reinforcing or countering. Some of the bravest writers challengethe status quo; they are those who bring a fresh perspective and break apartthe literary bird-wires that the other parrots stand on. Art drives thought. Itinfluences public opinion and politics. By presenting fictional situations, youcan make folks consider things they might be resistant to thinking about inreality because when it’s "just fiction," it's safe. But you can'tun-think a thought. Once you've had it, it's there forever. You can't help butapply it to your real life. What I mean to say is, if racist lady-haters readmy fiction and my crafty literary guiles trick them into liking it, slowly butsurely, things can change.

8 - Do you find the processof working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I love working with outsideeditors. I feel like once I have submitted a story to someone, it is no longermine. It becomes collaborative. It belongs to everyone who touches it. So Idon't feel defensive when I see my drafts changing. The original story isalways in the original draft if I want to visit it. What happens after is itbecomes a different animal. Outside eyes are essential to making a storystrong, for giving it teeth so it can protect itself from the discerning eyesof readers. Editors fill in the story’scracks, make it resilient and fierce.

9 - What is the best pieceof advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Just put it out there. Letsomeone else read it. But tell yourself you don't care what they think. You cantake their opinion or leave it. Once your work is out there, there it is. Theworld officially knows you are not typical. Your secret is revealed. You arefree.

10 - How easy has it beenfor you to move between genres (poetry to screenplays to short fiction)? Whatdo you see as the appeal?

Very easy. I have switchedgenres frequently. I have entirely rewritten many pieces in a different genrebecause the new medium was better for the story. I wrote a flash fiction aboutthis fisherman who was dying but wanted to buy a new truck. It was called"The Long Haul". Many editors passed over it, and I had pretty muchshelved it, but then I rewrote it into a short screenplay, and it won all sortsof awards. The screen was just a better home for that story; it was justwaiting for me to realize it.

11 - What kind of writingroutine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day(for you) begin?

I have no routine. My lifeis too chaotic. I have a day job with rotating hours and a family full of folkswith ADD. Trying to maintain order and routine is a recipe for disappointment.I think my routine is just giving myself blanket permission to stop what I amdoing at any given point in the day to write down an idea and email it tomyself. When I find time, I open the email and run with it. Also, I have a verysupportive family that can distract themselves quite effectively if I disappearto write things down. I also sign up for those online one-time generativeworkshops, just to get something granular in a file with its own name on mycomputer. Because once that is there, I want to complete it. I find the time inthe margins because my mind will not rest otherwise.

12 - When your writing getsstalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?

I sign up for one of thosecontests where they give you a prompt and a time limit. There have been manytimes that I have become convinced my creative well has finally run dry, andthen one of those contests kicked my ass back into gear. It’s true what theysay. Writing crap is better than writing nothing. I think a lot of writer'sblock is just anxiety. Like there’s this blinking cursor in front of you that'sjust whispering, "yousuck-yousuck-yousuck," and you start to believeit. But if you can push that little demon down the page, it loses its hold overyou. And the next thing you know, you have a draft. And that draft might suckrocks, but it's something. And oncethere's something on the page, the anxiety ends. All you have to do is edit. Ifind editing way less stressful because by the time I’m editing, I already feellike a writer again.

13 - What fragrance remindsyou of home?

Lilacs. They used to growoutside my window. And mildew. From my grandpa's books.

14 - David W. McFadden oncesaid that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influenceyour work, whether nature, music, science, or visual art?

Defiantly music. I oftenplay music while I am writing. I don't listen to what I like. I listen to whatmy characters like or something that sets the mood of the scene I am trying toconjure. I guess it's the filmmaker in me again. Every story needs asoundtrack. There have been times when I'm writing something, and its falling flat.I'll put on a song and, voila, there itis, the jewel I was looking for. Music lets your associations go loose. Itenables you to spin around the way required to be creative. A lot of creativityis the ability to be disjointed in an interesting way. Music puts you into thatspace if you are the kind of person who is not super into drugs.

15 - What other writers orwritings are important for your work or simply your life outside of your work?

I am a Miriam Toews fangirl.She is a total inspiration to me because she threads that needle between comedyand tragedy so elegantly. I wish I could write a book as epic as All My Puny Sorrows. Also, I appreciatethe friendship of other writers. When I was in St. John’s for my book launch, Imet many great writers. One was Susie Taylor, who wrote a fantastic cover blurbfor me. We were sitting with Tia, Jennifer, and Danielle in The Battery Cafétalking about writing and life, and it was like we were all buds from way back,even though we had just met. It was a perfect afternoon, the kind of thing youcarry in your pocket for a future grey day. Then, a week later, Susy sent me apicture of all our books together in the bookstore. What a perfect visual metaphor! Right now, Iam reading Susy's book, which is awesome. You should also read her book.

16 - What would you like todo that you haven't yet done?

Get interviewed by somesuper top-drawer literary program and shake things up a little. They would askme some subtly brilliant questions, and I would be “this close” to usingf-words at all times, and then afterward, they would tell me how "refreshing"my take was, and I would smile because, at that moment, I would be able to readtheir thoughts and their thoughts would be "Woah. This gal is messed up. Somebody get me a latte withMargaret Atwood, stat!”

Also, I would like to befamous enough to be disrespected by Eminem. Bring it, Slim!

17 - If you could pick anyother occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do youthink you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I would be a heavy metal rockstar in my dream parallel life. Big bangs, ripped jeans, and rocking onforever. I would never sell out to some reality show. I would never get plasticsurgery. I would go full Robert Smith (from The Cure) and become the visualrepresentation of the demon I had always implied was inside of me. When my popularitydeclined, I would go to political conventions and yell all sorts ofinappropriate/idealistic stuff until I got arrested on misdemeanors, and PeopleMagazine would do a “fall from grace” piece featuring my mugshot. "Sourcesclose to me” would speculate that I had finally gone off the edge, but littlewould they know I was living happily on a giant houseboat on the shores of LakeSuperior with my partner and kids and all sorts of exotic reptiles, cackling withthe knowledge that I had invested wisely in the 90s and could ride the rest ofmy life on the coattails of my prudent financial choices.

18 - What made you write, asopposed to doing something else?

Loneliness. I think writingfiction comes naturally because I am an only child who lived rurally and hadbusy parents. For most of my early life, I needed elaborate fantasies forcompany. I made stories in my head as a means of survival so I wouldn't feel soisolated.

19 - What was the last greatbook you read? What was the last great film?

I am currently enjoying the hellout of Susie Taylor's book Vigil. It's funny. It's crafty. It's just the rightamount of bizarre. The last great film Iwatched was Wim Wenders' Perfect Days. It was a meditative filmwith stunning cinematography about a reflective guy who cleans Tokyo toilets. Iconvinced my teenage son to see it with me. He was like, "OMG. Do I have to? It's just gonna be one of thosecrap adult films where literally nothing happens, and you will want to talk tome for 10 hours straight about the symbolism." But he came with me becausehe is basically a good human and also I told him, "It’s going to beawesome! It was nominated for an Oscar!" My son was absolutely correct inhis summary. Still, the film was a multisensory triumph. 10/10. The best part of it, though, was theexperience of seeing it with a dis-impressed teen. At the film's beginning,they have to set up the protagonist's routine as he cleans eight successivetoilets in silence. In the midst of this, my son leans over and whispers in myear, "You're right, Mom. This s**t is riveting," in the snarkiesttone imaginable. Then I started seeing the film through his eyes, accompaniedby his sarcastic soundtrack, and I started laughing my ass off in the theatre.This caused my son to be absolutely mortified, which made it all the more funny.Art is a beautiful, beautiful, feed-forward cycle of joy.

20 - What are you currentlyworking on?

A novel! My cue card ringoverfloweth! I started drafting it in a little house on Middle Battery Roadright after my book launch. The protagonist is loosely based on my great auntGeorgina who lived on the edge of things in Detroit. It concerns hercomplicated friendship with the bad-assed dude who did her nails and theirquest for a red 1968 Cadillac.

July 26, 2024

Adrienne Gruber, Monsters, Martyrs, and Marionettes: Essays on Motherhood

After I became a mom,stuff began to fall on me.

It took a few years for me to notice, a few more yearsbefore it became a regular occurrence, and even more time before it felt like ahazard. Eventually, I thought that perhaps I should be wearing a helmet or ahard hat around my apartment, or that I should outfit myself with a chest andbackplate to allow for optimal protection.

I compiled a list of things that fell on me.

Tools. A measuring tape. A giant brick of Parmesan cheesethat Dennis bought from Costco. A bottle of Shout. A jug of laundry detergent. Packagesof instant noodles. The handle of the vacuum. My kids’ puffy jackets, and otherclothes shoved in the bedroom closet. Shoes. The circular blades of the foodprocessor. Paper towel rolls. Bottles of bubbly water. Individual containers ofapplesauce. Picture frames. That tiny fucking Ben & Holly’s Little Kingdomcastle. Cans of tuna.

Puttering around my apartment became a contact sport. I neededto anticipate falling objects, slow down time in order to have the chance toreact, to pull my body out of the way. I had to be on high alert at all times.

It was also my job to heal quickly and efficiently andquietly if I happened to get struck by something. To not make my daughters waita single second longer for their Goldfish crackers, their cut-up apples, ortheir TV.

I’mamazed by the writing and shape of Vancouver writer Adrienne Gruber’s hybridessay collection,

Monsters, Martyrs, and Marionettes: Essays on Motherhood

(Toronto ON: Book*hug Press, 2024), produced as “Essais No. 16.” If you aren’t awareof their “essais” series, titles produced over the past decade or so include ErinWunker’s Feminist Killjoy: Essays on everyday life (2016) [see my review of such here], Chelene Knight’s Dear Current Occupant: A Memoir (2018)[see my review of such here], Margaret Christakos’ Her Paraphernalia: OnMotherlines, Sex/Blood/Loss & Selfies (Toronto ON: BookThug, 2016) [see my review of such here] and River Halen’s Dream Rooms (2022) [see my review of such here]. Moving through the titles-to-date, the series, edited by Toronto poet Julie Joosten, appears to focus on prose works (a handful of which attendthreads on mothers and motherhood) that aren’t straightforward to categorize, offeringstunning and in-depth, deeply personal works of lyric/hybrid prose by numerousCanadian writers at the top of their game. If you seek personal essays composedby writers unafraid of blending genre, poetic language and twisting expectation,these titles easily include some of the most powerful writing I’ve read inyears.

I’mamazed by the writing and shape of Vancouver writer Adrienne Gruber’s hybridessay collection,

Monsters, Martyrs, and Marionettes: Essays on Motherhood

(Toronto ON: Book*hug Press, 2024), produced as “Essais No. 16.” If you aren’t awareof their “essais” series, titles produced over the past decade or so include ErinWunker’s Feminist Killjoy: Essays on everyday life (2016) [see my review of such here], Chelene Knight’s Dear Current Occupant: A Memoir (2018)[see my review of such here], Margaret Christakos’ Her Paraphernalia: OnMotherlines, Sex/Blood/Loss & Selfies (Toronto ON: BookThug, 2016) [see my review of such here] and River Halen’s Dream Rooms (2022) [see my review of such here]. Moving through the titles-to-date, the series, edited by Toronto poet Julie Joosten, appears to focus on prose works (a handful of which attendthreads on mothers and motherhood) that aren’t straightforward to categorize, offeringstunning and in-depth, deeply personal works of lyric/hybrid prose by numerousCanadian writers at the top of their game. If you seek personal essays composedby writers unafraid of blending genre, poetic language and twisting expectation,these titles easily include some of the most powerful writing I’ve read inyears.FollowingGruber’s three full-length poetry collections—This is the Nightmare(Saskatoon SK: Thistledown Books, 2008), Buoyancy Control (Book*hug,2016) and Q & A (Book*hug, 2019) [see my review of such here]— Monsters,Martyrs, and Marionettes feels a direct extension of some of the concernsof that third poetry title, itself described as “a poetic memoir detailing afirst pregnancy, birth and early postpartum period.” Gruber explores andarticulates the dark elements of pregnancy and mothering, from depression andexhaustion to whole swaths of anxiety across wonderfully astute, unflinchingand absolutely devastating lyric and hybrid prose. She attends the beautifulmoments, certainly, but digs deep into the physical, spiritual and psychologicaldifficulties she endured surrounding motherhood, from the tantrums of her firstborn,ongoing mental health challenges and watching her mother’s cognitive decline.Gruber writers of and through numerous elements so often dismissed as the messybusiness of motherhood, acknowledging the blood that accompanies this kind of beauty.“An ache radiates from my tailbone and becomes like white noise,” she writes, toopen the essay “How She Runs,” “humming and flickering in the background. When Ichange positions, bend over, or go from standing to sitting, my lower backtwinges. Sometimes the pain is simply a feeling of tenderness, as though I’djust finished an intense workout. Sometimes it's deeper, sharper. Occasionallyit disappears momentarily, usually when I shift position, and for minutes, andsometimes hours, after I go for a walk.” Gruber’s essays push deep against the straightforwardnarratives of the beautiful and effortless ease of motherhood, digging into therealities of just what kind of journey she’s been on, from the moments andmyriad clusters of chaos, serious depression, physical changes, and the unexpectedand expected delights through the absolute and spectacular.

Ancient navigatorsthought the sea was filled with a number of dangerous sea monsters, but the Kraken,a legendary cephalopod-like beast in Nordic folklore was, by far, the mostterrifying. So large as to sometimes be mistaken for an island, the danger wasnot simply the creature itself but the whirlpool left in its wake.

When I gave birth to my daughter, I became the Kraken. Fortyhours of unmedicated labour followed by five hours of pushing will do that to aperson. I grew extra limbs that flailed and thrashed. With each contraction, I rosefrom the birth pool like a colossal mollusk, ready to crush and consume.

Monsters, Martyrs, and Marionettes exists as acurious montage of literary panache, from more traditionally-straightforwardessays to a pregnancy journal to sections that lean more into the lyric, suchas an accumulated essay on smell (pregnancy heightening certain of the senses,after all, including the sense of smell). Gruber writes openly and honestlyabout a wide range of fears, anxieties and experiences on pregnancy andmotherhood across and around her eventual three daughters. She writes of hergrandmother, and the challenges of her mother’s increasing requirement for care,allowing the book to attend to generations, from her grandmother to her mother,down to her daughters. Gruber writes of the presumption, both culturally andher own, of maternal invincibility: something she long saw in her own mother,until that, too, began to deteriorate. “After the breakdown,” she writes of hermother, “and a combined diagnosis of catatonia and psychosis, my mother’shealth begins to decline. It’s slow at first, the erosion, then a landsliderushing over exposed soil, dragging bits of it away. The meds dull herpersonality, make her tired. As a new mom, I’m tired too, with little energy tohelp build back up what had already been washed away.” There are passages thatfeel entirely composed as a ball of anxiety, but the writing is clear, evenpropulsive, and provides such clarity, and, above all, such a deep and abidinglove.

Toward the end of Quintana’sbirth, every second contraction was less intense. It was during those lessexcruciating spasms that I moaned the loudest, that I felt the most sorry formyself.

There is a difference between pain and suffering.

I tell people I used a birthing tub, that I birthed myfirst baby at home in my own apartment, that Dennis put a note on our doorapologizing to our neighbours for the noise. I say I ate Popsicles and took hotshowers, that I squatted on all fours like an animal and screamed in theprivacy of my walk-in closet.

All of this is true. None of this is true. (“Catalogue”)

July 25, 2024

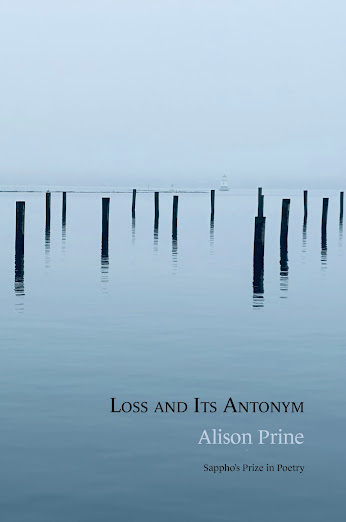

Alison Prine, Loss and Its Antonym

SONG OF A SMALL CITY

a small city is not anapple

it is not a cathedral ora gown

a small city produces aconfetti rain of tree blossoms

in the breath of a smallcity there are translations and the clinking of coins

here light falls acrossour faces

here one hour is transplantedinto the next

a small city does notrecognize its own hands

a small city holds upless sky and is therefore less grand and less weary

a small city does notmuscle toward the sea

the distance from the topto the bottom of a small city is one lost shoe

I’vebeen appreciating Burlington, Vermont poet Alison Prine’s second full-lengthcollection,

Loss and Its Antonym

(Sequim WA: Headmistress Press, 2024), producedas winner of the 2023 Sappho’s Prize in Poetry. Following the publication ofher debut collection, Steel (Cider Press Review, 2016), the poems inPrine’s Loss and Its Antonym are composed around silence, as a kind ofhush; articulating so much of what is spoken and unspoken, set down in fierceand delicate first-person lyrics. “it is hard to distinguish each element /locust blossoms falling from high branches,” she writes, as part of the poem “STRAYED,”“a full ashtray on the kitchen table / the smell of hard rain // posture of awoman ready to step / from one life to another [.]” There is such an ease tothese lines across some difficult terrain, of losses that sequence and compound,including the early loss of her mother, and subsequent stepmother, as shewrites in the poem “WISH BONE”: “My sister worried at our father’s wedding— / thatbecause she was seven when our mother died // we would lose our stepmother /when she turned fourteen. She believed // loss was divisible by sevens.” Thereis something astounding about how she balances such weight, from lines thatseem, at times, almost weightless to the depths of such losses, and how thoselosses continue to reveal themselves, even after a distance of years; somethingastounding, as well, in how Prine balances between those weights, while still composinga collection of poems about emerging out the other side from those losses, fromthat same grief. “Look for the small purple fleck in the center,” she writes,as part of the poem “CLOSE,” “it isn’t always there, but when it is // itfocuses the grace. So much of what we lost / was held in the same hands.” Inthe end, this might be a collection around grief and loss, but one that emergesjust as much into Prine acknowledging the bonds of family, and of sisters; abond that allowed for the possibility of moving through and potentially beyond suchdevastating losses. As the same poem closes: “I don’t know what happened // inyour family, but in my family it felt / like the world was split, over and over// and all that was left / were sisters.”

I’vebeen appreciating Burlington, Vermont poet Alison Prine’s second full-lengthcollection,

Loss and Its Antonym

(Sequim WA: Headmistress Press, 2024), producedas winner of the 2023 Sappho’s Prize in Poetry. Following the publication ofher debut collection, Steel (Cider Press Review, 2016), the poems inPrine’s Loss and Its Antonym are composed around silence, as a kind ofhush; articulating so much of what is spoken and unspoken, set down in fierceand delicate first-person lyrics. “it is hard to distinguish each element /locust blossoms falling from high branches,” she writes, as part of the poem “STRAYED,”“a full ashtray on the kitchen table / the smell of hard rain // posture of awoman ready to step / from one life to another [.]” There is such an ease tothese lines across some difficult terrain, of losses that sequence and compound,including the early loss of her mother, and subsequent stepmother, as shewrites in the poem “WISH BONE”: “My sister worried at our father’s wedding— / thatbecause she was seven when our mother died // we would lose our stepmother /when she turned fourteen. She believed // loss was divisible by sevens.” Thereis something astounding about how she balances such weight, from lines thatseem, at times, almost weightless to the depths of such losses, and how thoselosses continue to reveal themselves, even after a distance of years; somethingastounding, as well, in how Prine balances between those weights, while still composinga collection of poems about emerging out the other side from those losses, fromthat same grief. “Look for the small purple fleck in the center,” she writes,as part of the poem “CLOSE,” “it isn’t always there, but when it is // itfocuses the grace. So much of what we lost / was held in the same hands.” Inthe end, this might be a collection around grief and loss, but one that emergesjust as much into Prine acknowledging the bonds of family, and of sisters; abond that allowed for the possibility of moving through and potentially beyond suchdevastating losses. As the same poem closes: “I don’t know what happened // inyour family, but in my family it felt / like the world was split, over and over// and all that was left / were sisters.”

July 24, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Sarah Jane Sloat

Sarah J. Sloat

is a visual poet who splits her timebetween Frankfurt and Barcelona, where she works in news. Her collage, poetryand prose have appeared in Diagram, Shenandoah and Sixth Finch, among otherpublications. Sarah’s book of visual poetry, Classic Crimes, is due in2025 from Sarabande Books, which also published her previous book,

Hotel Almighty

.

Sarah J. Sloat

is a visual poet who splits her timebetween Frankfurt and Barcelona, where she works in news. Her collage, poetryand prose have appeared in Diagram, Shenandoah and Sixth Finch, among otherpublications. Sarah’s book of visual poetry, Classic Crimes, is due in2025 from Sarabande Books, which also published her previous book,

Hotel Almighty

.1 - How did your firstbook or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare toyour previous? How does it feel different?

Writing poetry changed mylife, but I’m not sure publishing poetry has. My first chapbook came out about15 years ago and I’ve since published four more. Soon after the last chapbook Igot into visual poetry. It was a complete refresh for me, and at first seemed adiversion. But I got attached to bringing a visual element to my work, it addslayers, associations and new possibilities. After I published a number of poemsusing the novel Misery, Sarabande approached me with the idea of acollection, which became Hotel Almighty. I’m grateful and still astounded.I’ll publish a second book with Sarabande next year, sourced from WilliamRoughead’s Classic Crimes, one of the first books of true crime.

2 - How did you come topoetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Suffering delivered medirectly to poetry.

3 - How long does it taketo start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially comequickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to theirfinal shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Not until I startederasure poetry did I ever start out with a larger project in mind. It wasalways poem by poem with me. Even now when I focus on a particular source textfor erasure I like to approach every poem as its own entity and put the othersout of my head. How many moods and tenses and forms and attitudes can springfrom one source? Thousands. I don’t go in with a hammer.

4 - Where does a poemusually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combininginto a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the verybeginning?

Can I be both? If not,I’m more a writer of short pieces that either begin to cohere with others, ordon’t.

5 - Are public readingspart of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer whoenjoys doing readings?

This is a hard onebecause I live in two countries, neither of which has English as a nativelanguage, so I can count my public readings on two hands even if you includeZoom. As a visual poet, I am trepidatious about readings mostly because oftechnology — I need a beamer/projector and screen or surface, etc. I fret aboutslides not working, batteries dying. This clobbers me with worry, but takes myfocus off my person, which is what most public readers worry about!

6 - Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are youtrying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

My work has a lot to dowith making the most of restrictions. My poems are sometimes trying to sort outa problem, if not explicitly. I want my poems to be beautiful and/or fun and/orhaunting but also to be pragmatic in a way, since in each case I am trying towork myself out of a box that puts constraints on what I can do.

7 – What do you see thecurrent role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? Whatdo you think the role of the writer should be?

Different writers canhave different roles, but we all reflect the times we live in. Each writerpasses along a way of looking at the world, of being within it.

8 - Do you find theprocess of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I’ve never reallyexperienced a meddlesome editor. At Sarabande, I love(d) my editor, KristenMiller. She is so smart and insightful and she helps me make better decisions.

9 - What is the bestpiece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

As a woman, it’s to makeyourself a priority.

10 - How easy has it beenfor you to move between genres (poetry to visual work)? What do you see as theappeal?

With text I am able tofocus on words without visual considerations butting in. If I am doing collagealone it’s usually just to help me get away from myself.

In terms of having movedfrom writing poetry of words & white space to poetry that is text+visual, Itravelled over in the blink of an eye.

I had been writing poetryfor years when it struck me to combine found poetry with collage andmultimedia. I love the associations the visual elements conjure, even withoutbeing deliberately connected to the text. I also love collage in and of itself.Being confined to the small canvas of the page, with the arrangement of textI’ve wound up with, is a deeply pleasurable challenge.

11 - What kind of writingroutine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day(for you) begin?

My day job and travelobligations mean I don’t have a routine. I snatch at time in the evening when Ican, and on the weekends or a day off. There’s no daily plan.

But in terms of theoverarching routine of how I work, I spend time with the text first andforemost, and the visuals follow. Very rarely do I have any visual image inmind at the outset, even if collages I’ve done independently of any poemwheedle their way into a piece.

12 - When your writinggets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?

I go to my favoritepoets: Charles Wright, Vasko Popa, Emily Kendal Frey, Lesle Lewis, Mary Ann Samyn, Alfred Starr Hamilton, Victoria Chang. Too many to name.

13 - What fragrancereminds you of home?

My husband’s cologne.

14 - David W. McFaddenonce said that books come from books, but are there any other forms thatinfluence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Visual art is a biginfluence, of course. There are so many great collage artists, but I also lovepainting and textile work. I wish life were longer and I could find time tolearn to paint and to become better at sewing.

15 - What other writersor writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of yourwork?

Let me go with non-poetryhere: Edouard Leve’s Autoportrait, Proust’s Swann’s Way, Lydia Davis, David Markson, Fleur Jaeggy, Lichtenberg’s The Waste Books, Kathryn Scanlan’s Aug 9 - Fog. I love short, enigmatic writing. I also love the rhapsodic.

16 - What would you liketo do that you haven't yet done?

Not get sick on a boat onthe sea.

17 - If you could pickany other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do youthink you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I’d love to design bookcovers. But I don’t think I would have taken that path as a younger personbecause I wasn’t in an environment where such a possibility would have occurredto me. I’ve been a reporter, a NOW canvasser, a professor, a temp secretary, adog sitter and cold caller. If I could become something else it might be anecoterrorist or the space shuttle or a bottle of scotch.

18 - What made you write,as opposed to doing something else?

Writing was the highestgood in my childhood household. My parents read and talked about books, myfather was a writer. If I’d grown up among shepherds or glass blowers it mighthave been different.

19 - What was the lastgreat book you read? What was the last great film?

If I may, I’ll bundle thebooks I’ve read over the past four years by Annie Ernaux into one — TheYears, I Remain in Darkness, Happening, A Woman’s Story,A Man’s Place, Shame, Simple Passion. Ernaux’srecollections are close yet distant, scant on outright emotion. She tells thehuman story plain, without the attitude and posing that plague so much memoir.

As for film, I feel I seemovies a lot less frequently now than before the pandemic. Whether it was greator not I don’t know but I loved Toni Erdmann. I loved Sandra Hüller’sperformance, how she captured something about the German personality. It was funnyand sad. I’ve watched it a number of times.

20 - What are youcurrently working on?

I’ve got a new projectgoing with an American classic that suffuses me with secret pleasure! It’serasure/collage like my previous work, but feels different, simpler.

July 23, 2024

what we did on our summer staycation, (part two,

[see the first part of our travels here] Two days (again) at Great Wolf Lodge, Niagara Falls, where I hobbled around in my boot, protecting my still-healing broken foot. Where I was unable to go into the water, which allowed a bit more time with notebook, pen; with reading.

Mother-in-law met us there, with six year old nephew in tow, which allowed for some good cousin visits (Christine's brother moving from England to Halifax this summer, which should allow some more-often cousin visits, perhaps). Our young ladies don't get to see any of them that often [although we were in London not long ago, where our young ladies enjoyed a good handful of cousin days].

Day two included a visit to Christine's great-uncle Charlie in Thorold, to see how he's been keeping. On the way back, catching a freighter through the Welland Canal: That boat is so long! Aoife declared. It must be a million Aoifes! (Christine looked it up: apparently "one million Aoifes" is equivalent to 232 metres).

The children, Christine and Oma even played laser tag (Rose came in fourth place, naturally). We all played a round of mini-putt golf. I sat on the step with notebook and reading material during both evenings, and caught a visit (again) from the local skunk, who toddled by both nights (and even the next morning). He was uninterested in whatever it was I was doing. Before we left, both young ladies and nephew their faces painted.

The children, Christine and Oma even played laser tag (Rose came in fourth place, naturally). We all played a round of mini-putt golf. I sat on the step with notebook and reading material during both evenings, and caught a visit (again) from the local skunk, who toddled by both nights (and even the next morning). He was uninterested in whatever it was I was doing. Before we left, both young ladies and nephew their faces painted.

Back in Picton another few days, we landed just in time to catch the latest PEP Rally at the bookstore, curated by Leigh Nash and Andrew Faulkner of Assembly Press (Christine reads at same in September, by the way), with readings by Sneha Madhavan-Reese, Spencer Gordon and Matthew Tierney! What are the odds? I don't even recall the last time I heard either Spencer or Matthew read.

Back in Picton another few days, we landed just in time to catch the latest PEP Rally at the bookstore, curated by Leigh Nash and Andrew Faulkner of Assembly Press (Christine reads at same in September, by the way), with readings by Sneha Madhavan-Reese, Spencer Gordon and Matthew Tierney! What are the odds? I don't even recall the last time I heard either Spencer or Matthew read.

Curious to start going through Spencer's latest, and I haven't even seen Matthew's yet. And did you know that novelist Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer lives rather close? Was good to see her again (we thought the last time we'd seen each other was at the final Scream in High Park in Toronto, which would have been more than a decade ago).

Curious to start going through Spencer's latest, and I haven't even seen Matthew's yet. And did you know that novelist Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer lives rather close? Was good to see her again (we thought the last time we'd seen each other was at the final Scream in High Park in Toronto, which would have been more than a decade ago).

And, once back at father-in-law's place (where we'd deposited the young ladies, just prior to heading to the reading), another three days of attending them, poolside. Another three days of reading, although we did manage a dinner, just the two of us. Up on a hill, way way up above the water. Did you know a small lake in those hills? And a brewery? A view along the water's edge to nearly-Kingston, nearly-Napanee. Point north, where Roblin Mills, or where my birth mother lives. Point east, where the wind farm sits on the horizon. Point east, where a tower sits, near the town of Bath.

In Picton, where the young ladies saw a handful of turtles along the water's edge, and Rose named one "Reginald," taking a forty-minute video (with my phone) of her new best friend and his adventures. Where they sat at the water's edge.

In Picton, where the young ladies saw a handful of turtles along the water's edge, and Rose named one "Reginald," taking a forty-minute video (with my phone) of her new best friend and his adventures. Where they sat at the water's edge.And then, Sunday afternoon, back to Ottawa. Aoife remains, spending some solo time with gran'pa and his wife for a few days, whereas Rose a day-camp began Monday morning.

July 22, 2024

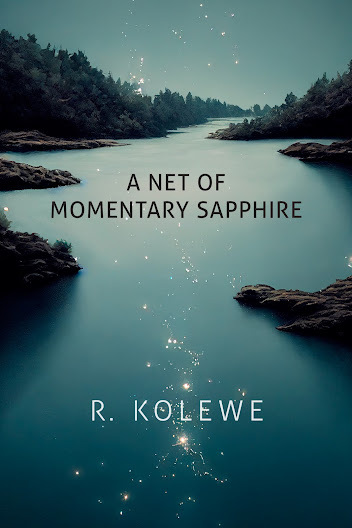

R Kolewe, A Net of Momentary Sapphire

38.

Not as if starting aninventory like Perec

(notepad, pencil, stackof dishes, gloves, the cat)

(again I’m lying) butoverlap or fold or

I haven’t understood athing.

Heard what I wantedflowers I don’t know.

Word cuttings in knottedlines & gaps.

Thelatest from Toronto poet R Kolewe is

A Net of Momentary Sapphire

(Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2023), a collection that “offers three closelyrelated poetic sequences, random rearrangements of a poignant but obsessivelyrecurrent source text – streams of consciousness in which no stable self can beelucidated.” There aren’t that many Canadian poets these days overtly workingin the tradition of the long poem – Vancouver poets Stephen Collis [see my review of his latest here] and Renée Sarojini Saklikar, certainly – and Kolewehas been feeling out the boundaries of formal innovation across the long poemform for some time now, from his Afterletters (Book*hug, 2014),

Inspecting Nostalgia

(Talonbooks, 2017) and

The Absence of Zero

(Bookhug Press,2021) [see my review of such here], as well as through a handful of chapbooks. Thereare even fewer Canadian poets working so deeply and through such lengthy worksvia the recombinant—although works by Grant Wilkins, Gregory Betts, Margaret Christakos [see my review of her latest here] and Sonnet L’Abbé [see my review of her recombinant project reworking Shakespeare’s sonnets here] certainly cometo mind.

Thelatest from Toronto poet R Kolewe is

A Net of Momentary Sapphire

(Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2023), a collection that “offers three closelyrelated poetic sequences, random rearrangements of a poignant but obsessivelyrecurrent source text – streams of consciousness in which no stable self can beelucidated.” There aren’t that many Canadian poets these days overtly workingin the tradition of the long poem – Vancouver poets Stephen Collis [see my review of his latest here] and Renée Sarojini Saklikar, certainly – and Kolewehas been feeling out the boundaries of formal innovation across the long poemform for some time now, from his Afterletters (Book*hug, 2014),

Inspecting Nostalgia

(Talonbooks, 2017) and

The Absence of Zero

(Bookhug Press,2021) [see my review of such here], as well as through a handful of chapbooks. Thereare even fewer Canadian poets working so deeply and through such lengthy worksvia the recombinant—although works by Grant Wilkins, Gregory Betts, Margaret Christakos [see my review of her latest here] and Sonnet L’Abbé [see my review of her recombinant project reworking Shakespeare’s sonnets here] certainly cometo mind. Acrossthree numbered parts, three separate sequences—“PART ONE: The foretaste of avision, but never the vision itself,” “PART TWO: Like the noises alive peoplewear” (part of which landed previously as an above/ground press chapbook) and“PART THREE: Beginning again & again is a natural thing even when there isa series”—Kolewe extends a sequence of collage-thoughts, writing a moment,another moment and a further moment in a lengthy, continuous string ofgestures. “I can’t write what I really cant. / Remember leave things out I amlike bees,” he writes, in the fifth part of the one hundred and twenty numberedsections of the second sequence, “That’s the real thing is what I said I said.// Ah, but then we would be come more than / modern, & death / always socontemporary.” Two pages further, part seven writes:

Rework this as there’s nojoy here

& not enough voicesno long poem containing

history –

too many ways to divideall these pages & letters & elegies

archaic forms of lifeunchanged by notebooks or photographs

or beauty unnameablerecognized –

Ifliterary writing can be considered a kind of study, which I deeply think it is,Kolewe is one of our more thoughtful contemporary practitioners, allowing awildly diverse series of threads to weave through his deceptively-straightforwardlyric collage. As part forty-eight, held in the second cluster of the secondsection, reads: “Rework this as there’s no joy here / & not enough voicesno long poem containing / any vision or revision of history – [.]” Through ANet of Momentary Sapphire, Kolewe examines lyric thinking, recombinantworks and the long poem through the very form of the long poem, seeking toexamine critically from the inside. “If there were a poem that made this /clear I would copy it here.” he writes, to open part ninety-two, “I can’t / sayif that’s true but I want it to be.”

July 21, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jenny Irish

Jenny Irish

is the author of the hybrid poetry collections

Common Ancestor

(Black Lawrence, 2017) and

Tooth Box

(Spuyten Duyvil, 2021), the short story collection

I Am Faithful

(Black Lawrence, 2019), the chapbook

Lupine

(Black Lawrence, 2023) and most recently

Hatch

(Northwestern University Press, 2024). She teaches creative writing at Arizona State University and facilitates free community workshops every summer.

Jenny Irish

is the author of the hybrid poetry collections

Common Ancestor

(Black Lawrence, 2017) and

Tooth Box

(Spuyten Duyvil, 2021), the short story collection

I Am Faithful

(Black Lawrence, 2019), the chapbook

Lupine

(Black Lawrence, 2023) and most recently

Hatch

(Northwestern University Press, 2024). She teaches creative writing at Arizona State University and facilitates free community workshops every summer. 1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Truthfully, my first book didn't really change my life. All of my books have been small, and I've written them because I wanted to without any expectations. I don't want to lose the pleasure I have in writing, and I'm also realistic. The vast majority of poetry books don't create any kind of visible stir, though they have their dedicated readers.

Publishing with Black Lawrence Press--more so than having a book in the world--was the biggest change, because I suddenly had a supportive group of people rallying behind me as a writer. This includes both the staff at Black Lawrence and my incredibly dear pressmates. Having a second book opened more professional opportunitys because it gave me the qualifications to apply to teaching positions. It's also been true that the more I've published, the more interest there's been in my writing.

Change is natural, I think. Writing changes over time--broadens or narrows--as a person figures out what it is that they want to do and can do with their own work. I'm all for experimenting and trying new things, but I'm at a point where I've figured out how I'm most comfortable writing. In the past--back in school and when I was first teaching--when someone said that they didn't understand my work or that they couldn't connect with it, it would make me doubt what I was doing. Now, I don't feel that. There're readers for every book, and books for every reader.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

True story! When I was little, one of my greatest entertainments was listening to a recording of Robert Frost reciting "The Witch of Coös," and in the town library there was an elaborate tableau of "The Death and Burial of Cock Robin" that I loved desperately. I feel like I had an excellent introduction to poetry. I knew those beautiful haunted pieces before anything else.

I think those early loves have contributed to why my writing often falls into hybrid space. Some people have described my most recent book, Hatch, as a novella in linked flash fiction pieces and others have described it as prose poetry. (It was published as a poetry collection.)

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I'm so much faster at writing than revising! Initial writing comes quickly--I scribble things everywhere on everything when I have an idea--but getting to a final draft is much slower. I don't plan projects. I just write and that often means I find out that there are important pieces missing when I start to put the pieces I have together. I'm also dyslexic and that contributes to a lot of necessary editing. It's a slow process, because I have to listen to my work read back to me by the computer. My eyes will just skip right over my errors on the page.

I'm so happy for those writers who just love revision, because it's so important.

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I know, very loosely, the story of the book that I'm working on, but I don't know any specifics until I write them. My books come together piece by piece. My writing is associative so writing one piece often activates another. Usually, a piece starts because of something fascinating (or awful) that I've heard or seen.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I haven't had an awful lot of opportunities to read publicly. I don't really enjoy being focused on, but it's always very nice to be asked to share your work! I was invited to be part of a reading and discussion with Eileen Myles that was held in the living room of Virginia G. Piper Center (a space where I feel very at home), and that was such a positive experience. Public reading is something that I'd like to get better at. I do enjoy going to readings. It's always really interesting to hear authors reading (or performing) their own work. I heard Venita Blackburn read from How to a Wrestle a Girl , and it was so unexpected and totally captivating. The creative writing students there were all in a swoon.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

My writing asks a lot more questions than it answers.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Writers have a lot of roles, I think. Writing is entertainment, it's educational, it's political, it's documentation. Different writers' work has different goals and meets different needs. Living in our very precarious and too often disengaged world, I do hope that Hatch encourages readers to consider the complex relationships between cause and lasting effect. I hope it makes people think.

Hatch is more explicitly political than my other books, but I'd be happy if a reader was initially interested because it's a speculative collection. People will come to the book for different reasons, and once they're there, I hope they'll engage with it, think, and ask their own questions.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I'm always grateful to have others give my writing their time and attention. I think if an editor is invested in your work and you're appropriately open, it can only be a positive and productive relationship. I've heard occasional horror stories where an editor wants to make changes to such an extent that they are basically re-writing the work in their vision and preferences, and that isn't right. The relationship between writer and editor should be grounded in mutual respect, and I've been fortunate to work with supportive, generous, smart people at both Black Lawrence and Northwestern University Press.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Oh goodness: knowing when to stop. I think this is really challenging for a lot of writers! There's a point where you're no longer improving a piece, just changing it, and that can go on forever. I think all writers need to learn when they've done all they can with a piece and how to let it go.

And: be kind. There's no need for hierarchies, cliques, and bullying.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to hybrid works to short stories)? What do you see as the appeal?

I don't really think about genre when I'm writing. I'm interested in prose poetry and genre hybridity, and I teach courses primarily in fiction, but I don't write with the idea this is a short story or these are poems. It happens sometimes that I'll submit a piece as one genre and a journal will ask to publish it as another.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I don't have a writing routine. Personally, I think that having the time and means for a daily writing routine is a luxury that is completely unrealistic for many people. While I admire those with a daily routine who find it productive, I resist the idea that it's necessary for a writer. The majority of students that I work with have jobs, and a number of them have children. As an undergraduate, I was working part-time jobs around my classes. I wrote on scraps of paper when I could, and I was publishing my work in literary journals. It's not that I don't think a daily writing routine can be a helpful structure for some, but I also think we need to recognize how disconnected that possibility is (without significant sacrifice of sleep, family time, or necessary income) from the lives of many people.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

When I don't feel like writing I don't write. I usually have multiple book projects underway at once, so if I'm having trouble with one, I can switch to the other, but I don't force work. Back in school, that was sometimes necessary, but it was frustrating with disappointing outcomes. Writing is something that I enjoy, and I don't want to lose that by making it too much into "work." Publishing isn't the source of my income, even though it's tied to my career. By not over-investing in production, I hope that for students I'm modeling one of many possible relationships to writing.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Oh, I love this question. Seaweed and frozen pond, if I'm thinking of childhood. I grew up in Maine, but now I live in the desert. When it rains here, it rains hard, and there is the distinct smell of creosote. Last, and this is not place specific: Nellie, my dog. There is nothing as soothing and home to me as how she smells.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

PBS is essential to my work! That may sound silly, but I often have it on in the background, and I'm always half-hearing something that I want to confirm or learn more about. I think PBS is always exposing me to things I wouldn't think to seek out on my own.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?