Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 43

August 18, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Shannon Robinson

Born andraised in Ottawa, Shannon Robinson is author of The Ill-Fitting Skin,winner of the Press 53 Award for Short Fiction. Her writing has appeared in TheGettysburg Review, The Iowa Review, Joyland, The Hopkins Review, andelsewhere. She holds an MFA in fiction from Washington University in St. Louis,and in 2011 she was the Writer-in-Residence at Interlochen Center for the Arts.Other honours include Nimrod's Katherine Anne Porter Prize for Fiction,grants from the Elizabeth George Foundation and the Canada Council for theArts, a Hedgebrook Fellowship, a Sewanee Scholarship, and an Independent ArtistAward from the Maryland Arts Council. She teaches creative writing at JohnsHopkins University.

1 - Howdid your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recentwork compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Thepublication of The Ill-Fitting Skin, my debut short story collection,comes at a time in my life when I already have significant milestones behindme, so it does not feel “life-changing” ... but it does give me a great senseof accomplishment. My most recent work feels like a continuation of my olderstuff in that it’s concerned with similar themes (notably, female experienceand nurturing). I think my newer work is more confident, although my olderstories have benefited from recent revisions.

2 - Howdid you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I’dalways loved fiction, but I never tried writing it: I admired it at a safedistance. As a teenager, I wrote the obligatory terrible poems—I was verypreoccupied with the prospect of nuclear Armageddon. (Those fears have now beendisplaced by fears of climate disaster.) At university, I wrote comedy revuesketches and feminist/cultural commentary/humour pieces for the studentnewspaper and later for community radio. I started writing fiction after Imoved to the United States and wasn’t legally entitled to work in the country;my husband, a poet,suggested that I take a creative writing class. I wrote my first story, and thatwas it: I knew I wanted to keep doing this for the rest of my life. It was likeone of those dreams where you discover a room in your house that you never knewexisted.

3 - Howlong does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writinginitially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear lookingclose to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

How longdoes it take? Forever. Whenever I readinterviews with authors who say “I wrote this all over the course of one,intense evening …” I am filled with wonder and envy. Sometimes certain imagesor ideas will be gestating in my head for years before I push them onto paper.An initial draft may take weeks or months; I do several drafts and will makesubstantial edits. I’ve gone back to stories years later to make changes—toadjust some emotional turn or stretch of dialogue that never quite felt right,or no longer feels right.

4 - Wheredoes a work of fiction usually begin for you? Are you an author of short piecesthat end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

For me, awork of fiction begins with some preoccupation—some point of fascination,something that has a buzz of ambiguity and ambivalence. I press on that tenderspot; I go into that cave for narrative and characters. As I was writing thesestories, I wasn’t initially working toward a book—but eventually I could seethat they presented a thematic coherence that would make for a good short storycollection.

5 - Arepublic readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sortof writer who enjoys doing readings?

Iabsolutely love doing readings! I’m anex-theatre kid, and I’ve always enjoyed performance. My favourite events are ones with multiplereaders: these have great energy. I tendto read finished pieces rather than work in progress, so I wouldn’t sayreadings are part of my creative process … but I do think readings help authorsbuild readership. I have some events set up for the upcoming months, and I’mlooking to add more.

6 - Doyou have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questionsare you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the currentquestions are?

I trynot to be too “theory forward,” because I think initial certainty can be thedeath of good fiction-writing. That said, I think fiction is an excellent placeto explore fraught territory, be it emotional, social, philosophical, political… and I definitely have opinions … which I am always willing to unsettle. I am interested in maternity; I’m interestedin women’s anger; I’m interested in shame and forgiveness and emotional hunger.A phrase that echoed through my head as I was writing the stories for TheIll-Fitting Skin was a line from Margaret Atwood’s The Edible Woman:one character declares “Florence Nightingale was a cannibal.” If women aresynonymous with nurturing, who are we if we botch the job of caring forothers? How do we care for ourselves ifwe are socialized against our own interests?

7 – Whatdo you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they evenhave one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

SometimesI feel like the Russell Crowe character at the beginning of Gladiator:“Hold the line! Hold the line!” he shouts, standing with his troops while theGermanic army thunders towards them. (In this metaphor, the approaching armystands for AI, corporate capitalist forces, conservative-driven censorship, orany entity hostile to creative endeavours.) Or maybe writers are better cast asthe “Barbarians,” charging wildly against the establishment and received ideas…?

I thinka writer’s role should be to entertain, to provoke thought, and to imaginativelyengage our empathy. I’m not going totell anyone what their art should be, but maybe let’s not encourage people tolean into their pettiest, cruelest, and most selfish inclinations.

8 - Doyou find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential(or both)?

I thinkit’s important to have an outside reader for work in progress. That may be aneditor, but it also might be friend or a fellow writer (or both) who caresenough about you and your writing to tell you what’s working and what isn’t. I’verelied on the feedback of my husband (James Arthur, the aforementioned poet)and on my writing workshop, who are all women I did my MFA with, years ago:Katya Apekina, Emily Robbins, and Lia Silver. They have all cheered me on andhelped me sort out problems. For my short story collection, I worked withfiction editor Claire Foxx, who provided invaluable line edits, particularly onmy older stories. I have a graduate degree in English, but Shannon of the Pastclearly did not understand comma splices. I am humbled by and grateful for eachand every correction.

9 - Whatis the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to youdirectly)?

Yearsago, I was talking with Jean McGarry, and I was struck by something she said: knowwhen you’ve arrived. That is to say, don’t waste time doubting yourself, justget on with it. Doubt will always be part of the writing process. And I thinkit’s easy for women especially to feel like doubt and self-disparagement are therent you pay for any current position of accomplishment. No need for that.

10 - Whatkind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How doesa typical day (for you) begin?

Am I partof the 5:00 a.m. club? Nope. I would sleep in until noon every day, but someonehas to feed the cats. And drive everyone to school. I am one of thosehypocritical writing instructors who tells her students that you must “writeevery day,” and then I fail to do so. During the academic year, my mind andtime are taken over by teaching, and I get very little writing done, but duringthe summer, I do write every day, for at least two hours. In the evenings, wecook elaborate meals and then watch a movie.

11 - Whenyour writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of abetter word) inspiration?

When mywriting is stalled, I turn to novels and short stories that I’ve been eager toread. I think we should all ignore that voice in the back of our heads thatsays we shouldn’t read others’ work when we’re trying to write, lest we bediscouraged by its comparative awesomeness or find ourselves unduly influenced… I always find that good writing juststokes my own fire. If you’re reading fiction, you’re still engaging yourimagination, but you’re giving your unconscious mind a chance to do some workon its own.

12 - Whatfragrance reminds you of home?

I thinkof several places as “home”: Baltimore(where I live now, in a three-story pre-war house with various eccentricities);Toronto (where I lived for seventeen years, in university dorm rooms andvarious apartments); Ottawa—and in particular, the house that was my childhoodhome, which has been sold, so in a way, it no longer exists. When I think ofthat home, I think of the smell of simmering Bolognese sauce. Or “spaghettisauce,” as we called it, because it was the 80s and we weren’t fancy.

13 -David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any otherforms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I’vealways been drawn to visual art and to music that might seem, on the surface,to be whimsical, and yet contains darkness and turbulence. As a child, I wasfascinated by Beatrix Potter’s illustrations, which are all delicately renderedanthropomorphized animals … engagedin acts of destruction and predation. I foundthe Beatles interesting, too: sure, the melodies are sweet, but you can justfeel the anger rolling off those guys, particularly Lennon and McCartney. Recently, I’ve been interested in the work ofMax Ernst—his surreal collage, which is full of sexy Victorian nightmarishdanger. And in Bjork’s music: peoplethink she’s cute, but her songs go through you like a crystal knife.

14 - Whatother writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your lifeoutside of your work?

Writerswho’ve been important to me include Alice Munro, Margaret Atwood, Toni Morrison, John Cheever, George Saunders, Kazuo Ishiguro, Lorrie Moore, Shirley Jackson, and Gabriel Garcia Marquez. This is by no means a complete list! I’mconstantly in the process of discovering writers who inspire me. It’s alwaysexciting come across a story and think, “Dang,” (see Ottawa author André Alexis’s tragicomic masterpiece, “Houyhnhnm”) or “Wherehas this been all my life?” (see Ambrose Bierce’s weird and magical “AnOccurrence at Owl Creek Bridge”).

15 - Whatwould you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I wouldlike to publish a novel. I’m working on it.

16 - Ifyou could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or,alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been awriter?

Thiswould involve going back in time … but I think I would be either an actor or apsychiatrist. As a younger person, bothpaths were appealing to me. Currently, as a writer, I sort of get to combineaspects of both those professions.

17 - Whatmade you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Inanswering this question, it was so tempting to look to see how other writersresponded—whether they all said some variation of “masochism” or “stubbornness”or claimed they write because they’re “not good at anything else.” You know—jokey answers that are nonethelesstruthful. Writing is the most difficult and the most frustrating thing I’veever done, but it’s also the most stimulating and the most satisfying. And yes,there’s a certain amount of sheer bloody-mindedness. And attention-seeking.Writing is the perfect intersection of my introversion with myextroversion.

18 - Whatwas the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I justfinished reading Rachel Yoder’s Nightbitch. Incredible. The last great film I saw was KennethBranagh’s Belfast. Likewise.

19 - Whatare you currently working on?

I’mworking on a novel about a Victorian baby killer, based on an historical figure.I’m writing at the same time as doing research, and I’m wrestling with the ideaof form and historical fiction. I’ve just started reading Rachel Cantor’s Half-Lifeof a Stolen Sister, which looks at the Brontë sisters through akaleidoscope of the past and contemporary, using (to quote the jacket copy) “diaries,letters, home movies, television and radio interviews, deathbed monologues, andfragments from the sprawling invented worlds of the siblings’ childhood.” It’sbrilliant, and it’s really opening up my thoughts on what a neo-Victorian novelmight look like.

August 17, 2024

JoAnna Novak, DOMESTIREXIA

I couldn’t believe this

cardinal hopping

red fluff

in the yard

and more, green

all day long, the spread

of history, goodness,

the morning

made me hungry,

unstable, and talky (“Abundance”)

I’mvery excited to see a copy of American writer, editor and publisher JoAnna Novak’s latest poetry collection

DOMESTIREXIA

(Soft Skull Press, 2024),following

Noirmania

(Inside the Castle, 2018),

Abeyance, North America

(New York/Kingston NY: After Hours Editions, 2020) [see my review of such here]and

New Life

(New York NY: Black Lawrence Press, 2021) [see my review of such here]. “Seducing the reader with its unexpected entanglement of ‘domestic’and ‘anorexia,’” the back cover writes, “JoAnna Novak’s DOMESTIREXIA isa collection of poems that brings a behind-closed-doors sensuality to scenes ofhome life. Populated by unknowable characters wrestling with seeming abundance,DOMESTIREXIA plumbs the nature of longing and misbehavior, reimaginingthe home as a space for estrangement rather than intimacy.” The collection isset in five numbered sections, including a fourth, which is a reworked versionof her above/ground press chapbook,

Knife with Oral Greed

(2021) [afurther chapbook is forthcoming, I should mention]. Novak’s poems, as I’veencountered, offer depictions of situations, her attentive eye and deepperspective on what would otherwise be familiar. From pregnancy to geography,Novak writes on motherhood and domestic life through dark twists, distances andshadows, language honed bone-sharp. “with pleasure or / praise,” she writes aspart of the second sequence-section, “Abundance,” “we deserve / leeks / and littlegems / honorable / invitation meet / me / in the pantry[.]” As part of an interview via Touch the Donkey, she spoke of themanuscript, then still in-progress:

I’mvery excited to see a copy of American writer, editor and publisher JoAnna Novak’s latest poetry collection

DOMESTIREXIA

(Soft Skull Press, 2024),following

Noirmania

(Inside the Castle, 2018),

Abeyance, North America

(New York/Kingston NY: After Hours Editions, 2020) [see my review of such here]and

New Life

(New York NY: Black Lawrence Press, 2021) [see my review of such here]. “Seducing the reader with its unexpected entanglement of ‘domestic’and ‘anorexia,’” the back cover writes, “JoAnna Novak’s DOMESTIREXIA isa collection of poems that brings a behind-closed-doors sensuality to scenes ofhome life. Populated by unknowable characters wrestling with seeming abundance,DOMESTIREXIA plumbs the nature of longing and misbehavior, reimaginingthe home as a space for estrangement rather than intimacy.” The collection isset in five numbered sections, including a fourth, which is a reworked versionof her above/ground press chapbook,

Knife with Oral Greed

(2021) [afurther chapbook is forthcoming, I should mention]. Novak’s poems, as I’veencountered, offer depictions of situations, her attentive eye and deepperspective on what would otherwise be familiar. From pregnancy to geography,Novak writes on motherhood and domestic life through dark twists, distances andshadows, language honed bone-sharp. “with pleasure or / praise,” she writes aspart of the second sequence-section, “Abundance,” “we deserve / leeks / and littlegems / honorable / invitation meet / me / in the pantry[.]” As part of an interview via Touch the Donkey, she spoke of themanuscript, then still in-progress:I get tired of my defaultmodes of expression, and I try to do something different—in the case of thesepoems, work with characters, create a façade of narrative logic. I think ofnarrative as having false comforts, especially as of late, because of the ongoingnessof the pandemic. (And these poems were very much a product of the early days ofquarantine.) I bristle when I hear people say, “When COVID is over” or thelike. This idea that there will be a resounding “The End” seems false in thiscontext. This resonates with my own sense of the world, I suppose, tinged byneuroses or compulsions, where repetition upends the notion of causality. Butalso, in a vastly different context, my son—who is fifteen months old—doesn’tseem satisfied by “The End.” He points again at whatever we’re reading (BrownBear, Brown Bear, What Do You See?) as soon as I close the back cover.

Novakmoves through the tensions of domestic as subject—the disappointments, thedistractions, mundanities, degrees and difficulties—echoing the cultural depictionof domestic as some kind of punishment, while simultaneously attempting toallow the flowing possibilities and delights of such space for turning,becoming. As part of the poem “Highboy,” writing: “I love your sense. I loveyour stability. I love your advice. I love your father making furniture, jointsjoints vices files ferries roses and fathers, were I a man I’d be a father,shan’t I, shouldn’t I, someday: I know nothing, I am trying to learn. I am nota novena, prayerfully blank, embittered esposa, easily drunk, painting foxes, teethin denial, on tall chests of drawers. Let me survive the hand-me-downs andsentiment, the flinch before savings. Do I look vegan? Slow-mo flamboyant? Whatcan I do?” Coming at her subject from the side, her poems offer themselves as sharpellipses, running blood across lines. She writes the tensions between the twopoles, two sets of expectations, even from within her own narrator. “Be only agirl:,” she writes, as part of the poem “Nothing to Lose,” “What other rule isthere?”

August 16, 2024

Spotlight series #100 : Nate Logan

The ONE HUNDREDTH in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Indiana poet Nate Logan

.

The ONE HUNDREDTH in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Indiana poet Nate Logan

.

The first eleven in the series were attached to the Drunken Boat blog, and the series has so far featured poets including Seattle, Washington poet Sarah Mangold, Colborne, Ontario poet Gil McElroy, Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Ottawa poet Jason Christie, Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough, Ottawa poet Amanda Earl, American poet Elizabeth Robinson, American poet Jennifer Kronovet, Ottawa poet Michael Dennis, Vancouver poet Sonnet L’Abbé, Montreal writer Sarah Burgoyne, Fredericton poet Joe Blades, American poet Genève Chao, Northampton MA poet Brittany Billmeyer-Finn, Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer from Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1 territory) poet, critic and editor Joshua Whitehead, American expat/Barcelona poet, editor and publisher Edward Smallfield, Kentucky poet Amelia Martens, Ottawa poet Pearl Pirie, Burlington, Ontario poet Sacha Archer, Washington DC poet Buck Downs, Toronto poet Shannon Bramer, Vancouver poet and editor Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Vancouver poet Geoffrey Nilson, Oakland, California poets and editors Rusty Morrison and Jamie Townsend, Ottawa poet and editor Manahil Bandukwala, Toronto poet and editor Dani Spinosa, Kingston writer and editor Trish Salah, Calgary poet, editor and publisher Kyle Flemmer, Vancouver poet Adrienne Gruber, California poet and editor Susanne Dyckman, Brooklyn poet-filmmaker Stephanie Gray, Vernon, BC poet Kerry Gilbert, South Carolina poet and translator Lindsay Turner, Vancouver poet and editor Adèle Barclay, Thorold, Ontario poet Franco Cortese, Ottawa poet Conyer Clayton, Lawrence, Kansas poet Megan Kaminski, Ottawa poet and fiction writer Frances Boyle, Ithica, NY poet, editor and publisher Marty Cain, New York City poet Amanda Deutch, Iranian-born and Toronto-based writer/translator Khashayar Mohammadi, Mendocino County writer, librarian, and a visual artist Melissa Eleftherion, Ottawa poet and editor Sarah MacDonell, Montreal poet Simina Banu, Canadian-born UK-based artist, writer, and practice-led researcher J. R. Carpenter, Toronto poet MLA Chernoff, Boise, Idaho poet and critic Martin Corless-Smith, Canadian poet and fiction writer Erin Emily Ann Vance, Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi, Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, Canadian poet Peter Jaeger, Birmingham, Alabama poet and editor Alina Stefanescu, Waterloo, Ontario poet Chris Banks, Chicago poet and editor Carrie Olivia Adams, Vancouver poet and editor Danielle Lafrance, Toronto-based poet and literary critic Dale Martin Smith, American poet, scholar and book-maker Genevieve Kaplan, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic ryan fitzpatrick, American poet and editor Carleen Tibbetts, British Columbia poet nathan dueck, Tiohtiá:ke-based sick slick, poet/critic em/ilie kneifel, writer, translator and lecturer Mark Tardi, New Mexico poet Kōan Anne Brink, Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Melanie Dennis Unrau, Vancouver poet, editor and critic Stephen Collis, poet and social justice coach Aja Couchois Duncan, Colorado poet Sara Renee Marshall, Toronto writer Bahar Orang, Ottawa writer Matthew Firth, Victoria poet Saba Pakdel, Winnipeg poet Julian Day, Ottawa poet, writer and performer nina jane drystek, Comox BC poet Jamie Sharpe, Canadian visual artist and poet Laura Kerr, Quebec City-area poet and translator Simon Brown, Ottawa poet Jennifer Baker, Rwandese Canadian Brooklyn-based writer Victoria Mbabazi, Nova Scotia-based poet and facilitator Nanci Lee, Irish-American poet Nathanael O'Reilly, Canadian poet Tom Prime, Regina-based poet and translator Jérôme Melançon, New York-based poet Emmalea Russo, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic Eric Schmaltz, San Francisco poet Maw Shein Win, Toronto-based writer, playwright and editor Daniel Sarah Karasik, Ottawa poet and editor Dessa Bayrock, Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia poet Alice Burdick, poet, writer and editor Jade Wallace, San Francisco-based poet Jennifer Hasegawa, California poet Kyla Houbolt, Toronto poet and editor Emma Rhodes, Canadian-in-Iowa writer Jon Cone, Edmonton/Sicily-based poet, educator, translator, researcher, editor and publisher Adriana Oniță, California-based poet, scholar and teacher Monica Mody, Ottawa poet and editor AJ Dolman, Sudbury poet, critic and fiction writer Kim Fahner, and Canadian poet Kemeny Babineau.

The whole series can be found online here .

August 15, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Christian Gullette

Christian Gullette’s debut poetry collection Coachella Elegy (July 1, 2024) won the Trio House Press Trio Award, and his poemshave appeared or will appear in The New Republic, The American Poetry Review,Kenyon Review, the Poem-a-Day (Academy of American Poets), andThe Yale Review. He has received financial support from the Bread Loaf Writers’Conference and the Kenyon Review Writers Workshops. Christian completed hisPh.D. in Scandinavian Languages and Literatures at the University ofCalifornia, Berkeley, and when not serving as the editor-in-chief of The Cortland Review, he works as a lecturer and translator from the Swedish. Helives in San Francisco.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recentwork compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book just cameout officially on July 1, 2024, so it’s still very much a moment-to-momentexperience. The first thing I noticed was how different it felt to stand at amicrophone and read poems from a bound collection rather than printer paper.That really hit home.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction ornon-fiction?

Several high schoolEnglish teachers assigned readings from an anthology of poetry, and I washooked. As a kid just starting to recognize my sexuality, something about the lyricalgesture – the things unsaid as much as said, the compression, the emphasis onfeeling and image – really appealed to me.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Doesyour writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first draftsappear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out ofcopious notes?

I tend to write poems inbursts after several weeks or even months. And even then, it might just be afew poems. I need to live life. Travel. Go to the ballet or go hiking or watcha classic film. Stay out all night partying. A line might occur to me. I usuallywrite it down in my phone and leave it there for a while. What the poemsdiscover can take drafts to emerge, if it does.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of shortpieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a"book" from the very beginning?

Usually with that line I abandonedin my phone. If it keeps calling out to me in my head, I’ll come back later. Idon’t usually set out to write into a project. I wait for an obsession.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Areyou the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Readings are definitely apart of my poetry experience – especially attending as many readings by otherpoets as I can. I enjoy reading my own poems, as well.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kindsof questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even thinkthe current questions are?

I’m interested in thetensions between pleasure and pain, joy and loss, beauty and destruction. Thosecomplex, conflicting emotions are also part of an attempt to move throughgrief, which, in my poems, often finds expression seething beneath the surface,an intimacy and deep pain between the lines and in acute images rather thanbold declarations. I’m interested innotions of place, particularly California and notions of queer utopias, and thenarratives and destructive myths than inform them. Considering environmentalprecarity, drought, fire, land displacement are all part of that questioning. Anotherform of precarity is that of the body. There’s a lot of erotic desire in thebook, and I love to write love poems, but there’s a sense that the body isnever far from dissolution.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in largerculture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer shouldbe?

I hope my poems make areader feel something.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficultor essential (or both)?

I find it was an essentialpart of editing my book. But I also received the gift of editors who feltconnected to my work and invited me to participate in a collaborative process,while also not being afraid to suggest a few major suggestions that in the end,really sharpened my book.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily givento you directly)?

A mentor poet always tellsme to “keep going.”

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to translationto critical prose)? What do you see as the appeal?

I also work as aSwedish-to-English translator, so switching genres feels natural to me. Inaddition to translating fiction and non-fiction, I devote as much time as I canto translating poetry. I’ve learned so much about my own poems, especially regardingword choice and tone and music.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you evenhave one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I tend to write in theafternoons. It’s not constant or according to any schedule. I’m not a greatcafé writer; I like to be at my desk with my music and a tree or view out thewindow. Individual lines can come to me wherever and whenever, especially whentraveling.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (forlack of a better word) inspiration?

Travel, nature, andespecially museums. Movies. Hotels really spark memories. Cocktails on arooftop. Books can sometimes help, but I find them to be more helpful when I’min the mood to write.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Chlorine.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but arethere any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, scienceor visual art?

Art is very important tomy work. As is music. Nature for sure. Food.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, orsimply your life outside of your work?

There are so many writersand artists I return to, and it would be impossible to do that list justice,but here’s a brief attempt: C.P. Cavafy, Elizabeth Bishop, Tomas Tranströmer,Louise Glück, Henri Cole, David Hockney, Lana Del Rey, Ada Limón, Diane Seuss,Reginald Shepherd, Joan Didion, Randall Mann, Carlos Drummond de Andrade, Brigit Pegeen Kelly, Thom Gunn, Christopher Isherwood.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Publish a translation of apoet’s full-length collection. Learn Italian.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be?Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you notbeen a writer?

Cinematographer would becool. I’d love to live in Sweden and work for a Swedish television show. I’dwork at a dog sanctuary helping dogs splash in a pool.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

It insisted no matter whatI did, as if it were the only way I could know something about how to feelabout my experience.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Book: Modern Poetryby Diane Seuss

Film: La Piscine

20 - What are you currently working on?

Hopefullysome new poems after a few months, but I’ll have to see.

August 14, 2024

Clare Goulet, Graphis scripta / writing lichen

Normandina pulchella / elf-ear

Tender translation,

pulchella whispers

diminutives in dutch,

in finnish, friesian,

little shell, tiny bowl,

hamster, elfin, as if,

in secret, wet bark

on a fallen branch

had sprouted for a prank

a hundred pairs of ears

cut from green felt. Official

status: vulnerable.Crouch.

You must reshape yourself

in miniature to see

this rare thing: a conference

of listeners. Each anopen

invitation to kneel,

place your giant’s ear

on its tiny lobes: itsays

ssshhh, it says: be

smaller.

I’mfascinated by Kjipuktuk/Halifax, Nova Scotia poet Clare Goulet’s full-lengthpoetry debut,

Graphis scripta / writing lichen

(Kentville NS: GaspereauPress, 2024), a collection of poems approaching language as the means throughwhich to articulate a detailed study. “So pretty it shocks: pink smarties / shakenout of the box,” she writes, to open the poem “Icmadophilia ericetorum /candy,” “picked on a whim / for the green-room rider, pleasure spreading / itsplush blue blanket every which way / over moss.” There is a curious way that Goulet’slanguage propels, composed as field guide, scripting a detail through language thatsuggests hers is a somewhat slippery subject matter: is this a collectionaround the collection and study of lichen, or a means through which to discusssomething else entirely? Possibly both, honestly. Goulet’s poems provide a kindof layering, of waves and sweeps, writing around and through the subject oflichen, multifaceted enough to ply meaning upon meaning. “Lichen as armour istruth inverted: / a bullet-hole flowers,” she writes, as part of “Parmelia sulcata/ hammered shield,” “cancer / takes root, a wound is blessé.”

I’mfascinated by Kjipuktuk/Halifax, Nova Scotia poet Clare Goulet’s full-lengthpoetry debut,

Graphis scripta / writing lichen

(Kentville NS: GaspereauPress, 2024), a collection of poems approaching language as the means throughwhich to articulate a detailed study. “So pretty it shocks: pink smarties / shakenout of the box,” she writes, to open the poem “Icmadophilia ericetorum /candy,” “picked on a whim / for the green-room rider, pleasure spreading / itsplush blue blanket every which way / over moss.” There is a curious way that Goulet’slanguage propels, composed as field guide, scripting a detail through language thatsuggests hers is a somewhat slippery subject matter: is this a collectionaround the collection and study of lichen, or a means through which to discusssomething else entirely? Possibly both, honestly. Goulet’s poems provide a kindof layering, of waves and sweeps, writing around and through the subject oflichen, multifaceted enough to ply meaning upon meaning. “Lichen as armour istruth inverted: / a bullet-hole flowers,” she writes, as part of “Parmelia sulcata/ hammered shield,” “cancer / takes root, a wound is blessé.”Thereis something comparable, obviously, to Goulet’s explorations through theminutae of plants, language and Latin to the work of Saskatchewan poet Sylvia Legris [see my review of her latest here], although Goulet seems to offer herexplorations not as an end but as a means through it, such as the poem “Zaubreyussupralittoralis / dreaming,” that offers: “I have not been honest, not toldyou / years collecting lichen made a river of forgetting / which meant notthinking / about him.” Akin to Lorine Niedecker’s “Lake Superior,” or MontyReid’s The Alternate Guide (Red Deer AB: Red Deer Press, 1985), the poemsemerge out of the prompt of the original study of lichen, but instead wrap thatresearch around other considerations, other functions, across the length andbreadth of her lyric. She writes of the Greeks, intelligence reports, ShirleyJackson, Mae West, Plato, Mad Men, cartoon gestures and other touchstones,utilizing her research as both core and writing prompt, offering a solid lineof meaning thick with context. Listen, for example, to the poem “minim,” thatends:

Empty bars of music arewhere you rest,

this white sheet filledwith smallness

as if the whole orchestrahad assembled

for a lone note.

OPedicularis

Linnaeus has written

without a word.

August 13, 2024

Jane Huffman, Public Abstract

I had a bout

Of vertigo

Inside my chest

A clocking

From within

Was bested

By the worst

Of me again

As if my body

Shook off

All its walls

And doors

And reeled

The outside in (“[I had about]”)

I’dbeen curious for a while about University of Denver doctoral student and poet Jane Huffman’s debut full-length poetry collection,

Public Abstract

(PhiladelphiaPA: The American Poetry Review, 2023), a collection of razer-sharp lyrics that experimentwith form, and ride across a complicated, ongoing grief. “My body through / Theworld,” she writes, as part of the poem “[I’ve failed already],” “Like aparticle / Of sand // That moves / Forever toward // The sphere / Where itbegan [.]” She writes of her brother’s addiction as a death that occurs not allat once but in inches, miles, leagues; something ongoing, and her grief aswell. “I’ve mourned my living / brother many years.” she writes, to open thesecond poem of the sequence “Three Odes,” “This is the heavy / table of mywork. I lug / the heavy table / of my work around / all day so I am never rid /of it. I am never rid / of it – the work / that carries me like I’m / a tired childsleeping / in its arms. I sleep in / my brother’s arms.” She writes of herbrother, and of her own unspecified challenges with illness, “a bout / Ofsomething / Undefined,” she writes, as part of “[I had a bout],” “Anotherrattle / In the lung [.]” Composing odes, sestinas, fragments, haibun,variations, sonnets and further revisions, providing an absolute and delicatesharpness and ease that make her lines that much more remarkable, quietly emblazedacross each page. As her poem “Six Revisions” opens:

I’dbeen curious for a while about University of Denver doctoral student and poet Jane Huffman’s debut full-length poetry collection,

Public Abstract

(PhiladelphiaPA: The American Poetry Review, 2023), a collection of razer-sharp lyrics that experimentwith form, and ride across a complicated, ongoing grief. “My body through / Theworld,” she writes, as part of the poem “[I’ve failed already],” “Like aparticle / Of sand // That moves / Forever toward // The sphere / Where itbegan [.]” She writes of her brother’s addiction as a death that occurs not allat once but in inches, miles, leagues; something ongoing, and her grief aswell. “I’ve mourned my living / brother many years.” she writes, to open thesecond poem of the sequence “Three Odes,” “This is the heavy / table of mywork. I lug / the heavy table / of my work around / all day so I am never rid /of it. I am never rid / of it – the work / that carries me like I’m / a tired childsleeping / in its arms. I sleep in / my brother’s arms.” She writes of herbrother, and of her own unspecified challenges with illness, “a bout / Ofsomething / Undefined,” she writes, as part of “[I had a bout],” “Anotherrattle / In the lung [.]” Composing odes, sestinas, fragments, haibun,variations, sonnets and further revisions, providing an absolute and delicatesharpness and ease that make her lines that much more remarkable, quietly emblazedacross each page. As her poem “Six Revisions” opens:The doctor holds my chestagainst the discus, listens like the fish

below the ice listens tothe fisherman. “Medicine,” he says, “is

not an exact science.”

He listens like the ice fisherman listens to the fish. I breathe into

a nebulizer and thinkabout translation – inexact art. A fine,

particulate mist.

Thecollection as a whole circles moments such as these, offering an argument oflyric form and structure as a scaffolding to sharpen lyric thought. In certainways, these poems circle, even outline, this particular sense of loss socompletely as to form that absence into shape. Referencing Huffman’s poem, “ThreeOdes,” as part of her introduction, Dana Levin writes that:

Huffman’s variation on the duplex, a form invented bypoet Jericho Brown, comprises the second section of this poem and ends, “Mybrother’s / death is long, and heavy / as a year. I’ve mourned / my livingbrother all my life.” Such declarations of naked feeling are rare in thiscollection; when they appear, they break the heart, and one can feel a why andwage in Huffman’s obsessive focus on form: it (s)mothers pain, the source fromwhich he book’s formal feelings come.

Itis interesting, Levin’s simultaneous suggestion of smothering and motheringpain, where I would think Huffman’s formal elements allow such pain a direction,even a purpose; allow the pain a structure, without which it might otherwiseflail about. Whether or not this is splitting hairs, or reiterating, I’ll leaveup to you. Or, as Huffman’s poem, “Coda,” offers, brilliantly:

Form implies the oppositeof form:

a globule, aformlessness, a letting go.

(Like fear implies theopposite of fear:

relief, approximation ofthe human

form built in packingsnow.)

And yet, the opposite ofform (relief

from form) implies theopposite relief:

from formlessness. Packing snow

made globular when thrownis blown

back to the ether of thewhole: like grief.

August 12, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Em Dial

Em Dial is a queer, Black, Taiwanese, Japanese, and white writer born and raised in the Bay Area of California, currently living in Toronto. They are the author of

In the Key of Decay

(Palimpsest Press, 2024) and an MFA candidate at the University of Guelph. Her work can be found in the Literary Review of Canada, Muzzle Magazine, Arc Poetry Magazine, the forthcoming Permanent Record Anthology from Nightboat Books, and elsewhere.

Em Dial is a queer, Black, Taiwanese, Japanese, and white writer born and raised in the Bay Area of California, currently living in Toronto. They are the author of

In the Key of Decay

(Palimpsest Press, 2024) and an MFA candidate at the University of Guelph. Her work can be found in the Literary Review of Canada, Muzzle Magazine, Arc Poetry Magazine, the forthcoming Permanent Record Anthology from Nightboat Books, and elsewhere.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

As my first book came out last month, I think I am still in the midst of that change. I have been trying to soak in this moment, but I also feel so distant from some of the poems in this collection, that part of me is glad to have it out in the world so that I can focus on what is next. I'm sure that in a few months I will have had the time to process what it means to have this debut living out in the world, apart from me. I imagine the process is going to teach me a lot about trust and letting go.

I'm currently working on a couple of projects that centre nostalgia and chronic illness. I'm finding that through those topics, I'm allowing myself to zero in on the minutiae of day-to-day life, rather than the sweeping glances that are more prevalent in In the Key of Decay. I'm also playing around with form in new ways, especially longer-form works and prose poems.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

In the summer between my Freshman and Sophomore years of university, I was listless and depressed and confused, in a very 19-year-old kind of way. Through a series of aimless clicks on YouTube, I ended up watching dozens of spoken word videos, and was captivated for weeks. I wrote two poems of my own, and used them to audition for my university's spoken word collective that fall. I still do not fully understand how I ended up there, as I was not reading much besides my science textbooks at that age, but I think I just needed a way to get to know myself and contextualize my queerness and multiracialness in a world that was increasingly feeling very scary and overwhelming.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I'm learning that research and notes are kind of my way-finding tools towards creation. I'll do a deep dive and once I hit upon an idea that tickles something in me, I'll write a quick skeleton of a piece, then get back to reading. Every once in a while, I'll find something that really sparks a complete concept, and a poem looking almost fully fledged will come out. That is quite a rare experience, though.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

My first collection was an amalgamation of years of writing individual poems, that were then arranged into a shape that made sense, and from there I filled in the gaps. Now that I am working on more intentionally shaped projects, I am finding that I set out with a vague understanding of what the book might consist of, and then let the research process guide the process from there.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

For the many years when, for me, poetry was synonymous with poetry slams, writing and public readings were inseparable. Now that I have had some time away from the world of spoken word, I think I've grown distant from my desire to entertain an audience and do not enjoy reading my work as much as I used to. That separation has been helpful for my work, as I used to write poems with the goal of getting a 10 from a judge, but now that I've had time to develop a craft and practice that feel authentic to me, I'd love to build that entertainment muscle back up again.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Always! A mentor I worked with, Aisha Sasha John, once described my work as phenomenological. I think I am always trying to construct an understanding of something, most often that something being myself and my place in the world. Currently, more specifically, I've been trying to understand where my ideas of masculinity were formed, what kind of character my illness has when separated from myself, and why I feel such a stomach-churning obligation to American imaginings of suburbia.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

This might be a controversial opinion, but I think writers, poets especially, are too often given a mystic or sage or benevolent slant. I see writing as a tool, one that can move us towards revolution and liberation, but one that can just as easily be used to placate the masses or to justify and reinforce violent ideas. Personally, I feel the role of a writer like myself is to draw lines between different forces that influence our world and imagine new ways that we can exist with more safety and abundance. However, I don't think that is the role of all writers, and I think it feels even more like a mantle that I want to take on, because I know that there are writers in the world who may feel the opposite way that I do, penning odes to the war machine as we speak.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I mostly love working with editors! It is absolutely critical for me to have the eyes of others on my work. I've been very lucky to have almost exclusively positive experiences with editors who I built trusting, mutually respectful relationships with. My debut couldn't have been what it is without the eyes of Summer Farah and Jim Johnstone.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

You hear it a lot being from California, but it originally comes from a Hawaiian saying: Never turn your back on the ocean.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I haven't been able to sustain any sort of writing routine over the past couple of years while trying to work in the field of urban agriculture. Luckily, in the fall, I am headed to pursue an MFA in Creative Writing at the University of Guelph, where I will be forced into a more regular practice of writing. I'm hoping to get into a more regular practice of morning pages in the next couple of months. Currently, my days begin with rushing to walk my dog before needing to leave for the office.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I have a list of 15 or so favorite poems that I return to when I'm stuck, and try to understand what it is that I like so much about them. If returning to the familiar doesn't help, I'll usually try to read a chapter of a novel or an essay in a collection to shake me out of my poetry brain for a moment while still stirring up images that could potentially be repurposed into something.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Salty sludgy wetlands, Tide laundry detergent, brownies in the oven, the plastic smell of a VHS box, Meyer lemons, and my partner's face moisturizer.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I think I draw inspiration from a lot of corners of my life, but a lot of my work to date has drawn from music and film. Having studied biology and ecology, scientific language and theories often find their way into my poems as well. In the Key of Decay, for example, situates the speaker as constructed by the false sciences of eugenics and race and then acts to dismantle them.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

With much effort, I've limited myself to 10: Kingdom Animalia by Aracelis Girmay, I'm So Fine: A List of Famous Men & what I Had On by Khadijah Queen, The Autobiography of Malcolm X , Soft Science by Franny Choi, Homie by Danez Smith, The Essential June Jordan , Bestiary by K-Ming Chang, Zigzagger by Manuel Muñoz, A Cruelty Special to Our Species by Emily Jungmin Yoon, and Yellow Rain by Mai Der Vang

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Visit Taiwan, where my dad was born.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I think if it weren't for writing, I may have stayed in the environmental/food non-profit world for some time. If I were to pick anything besides writing, though, I think it would be something having to do with the ocean. Maybe being a scientific diver.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I think that I'm someone whose mind jumps from topic to topic, trying to make meaning out of 1,000 things at once. Writing has offered me a way to construct a sudoku out of the world around me, a frame in which to place the unknowable, confusing parts of the world. It feels like working at cracking a part of the code. I don't know if anything else could have offered that to me.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Pig by sam sax blew me away. It's been a while since I've seen it, but I haven't stopped thinking about Love Lies Bleeding .

19 - What are you currently working on?

The nostalgia and chronic pain collections I mentioned earlier, as well as becoming a student again! For anything else, you'll have to stay tuned!

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

August 11, 2024

jaz papadopoulos, I feel that way too

Birthday invitation readsNo Barbies Please.

Means, Barbie will hurtmy daughter’s life

with her long neck andneck-sized waist.

Really means, Daughter, Idon’t know how to explain to you

my fad dieting, foodrestriction, exercise regime.

I don’t know how toexplain to you the things that men and boys will say,

shout, whistle.

The complexities ofdominance and subjugation stifle me.

I fear my place in theworld and now your own, that of your small body

that is my own small body that I cannotcontrol.

So instead, when you holdher, inevitably, against all my attempts and

insertions,

when you hold your firstBarbie—our enemy—let us do this ritual.

We will build her a soulwith all the words we fear to hear:

Your body is wrong (toolong).

Your intentions,irrelevant.

Your aspirations, offensive.

Take her iconic body,make it an emblem of our grief and fear

—emblem, from the Greek emballein,to throw; insert—

put all that inside her

and throw her away. (“LESSON8: BLAME WOMEN,” “history of media”)

Thefull-length poetry debut by Lambda Literary Fellow, “interdisciplinary writer,educator and video artist” jaz papadopoulos is

I feel that way too

(Gibsons BC: Nightwood Editions, 2024), a collection of poems that, as Amber Dawn offers as a back cover blurb, “flay[s] rape culture open in ways thatdiscourse cannot.” Across four sequence-sections—“The Rules,” “History ofMedia,” “I Feel That Way Too” and “Epilogue”— papadopoulos articulates a studyof and around sexual violence via lyric narrative, composing a contemporaryconversation of depictions, dismissals, agency and ongoing trauma through erasure,repetition, specific examples and cultural markers. “A beautiful man / asks if Iwould read him a poem.” papadopoulos writes, as part of the extended title sequence,“I open / whatever I’d last written: hyssop help me, hyssop health me //hyssop help me now. Flowers pressed / over the Ghomeshi trial, itsinescapability.” I feel that way too offers an explosion of lyric expositionthat bursts out of a conversation long repressed, until it has no choice butexplode, and hopefully part of a larger, longer trajectory of cultural shift. Thelanguage papadopoulos utilizes is thick and rich with gymnastic, rhythmicdensity, including further in the title poem-sequence, as they write: “Bloatedraspberry. Overfilled / red balloon fishnets bulging plump / diamond rubies. Thecochineal / is a parasitic scale insect that lives on cacti in North and South America/ looking like Jessica Rabbit’s lips / procreated with a cob of corn and theoffspring / came out kernelled, in scarlet / rows, swelling at the seams.” Thisis a book about harm and solutions, and about how both are portrayed, mangled,represetend and misrepresented, writing out a string of savage truths andcircumstances, and the possibility and impossibly, the very limitations, oflanguage, thought and action. Or, as they write as part of the title sequence: “Itis so very / frustrating / when none / of the words work.”

Thefull-length poetry debut by Lambda Literary Fellow, “interdisciplinary writer,educator and video artist” jaz papadopoulos is

I feel that way too

(Gibsons BC: Nightwood Editions, 2024), a collection of poems that, as Amber Dawn offers as a back cover blurb, “flay[s] rape culture open in ways thatdiscourse cannot.” Across four sequence-sections—“The Rules,” “History ofMedia,” “I Feel That Way Too” and “Epilogue”— papadopoulos articulates a studyof and around sexual violence via lyric narrative, composing a contemporaryconversation of depictions, dismissals, agency and ongoing trauma through erasure,repetition, specific examples and cultural markers. “A beautiful man / asks if Iwould read him a poem.” papadopoulos writes, as part of the extended title sequence,“I open / whatever I’d last written: hyssop help me, hyssop health me //hyssop help me now. Flowers pressed / over the Ghomeshi trial, itsinescapability.” I feel that way too offers an explosion of lyric expositionthat bursts out of a conversation long repressed, until it has no choice butexplode, and hopefully part of a larger, longer trajectory of cultural shift. Thelanguage papadopoulos utilizes is thick and rich with gymnastic, rhythmicdensity, including further in the title poem-sequence, as they write: “Bloatedraspberry. Overfilled / red balloon fishnets bulging plump / diamond rubies. Thecochineal / is a parasitic scale insect that lives on cacti in North and South America/ looking like Jessica Rabbit’s lips / procreated with a cob of corn and theoffspring / came out kernelled, in scarlet / rows, swelling at the seams.” Thisis a book about harm and solutions, and about how both are portrayed, mangled,represetend and misrepresented, writing out a string of savage truths andcircumstances, and the possibility and impossibly, the very limitations, oflanguage, thought and action. Or, as they write as part of the title sequence: “Itis so very / frustrating / when none / of the words work.”

August 10, 2024

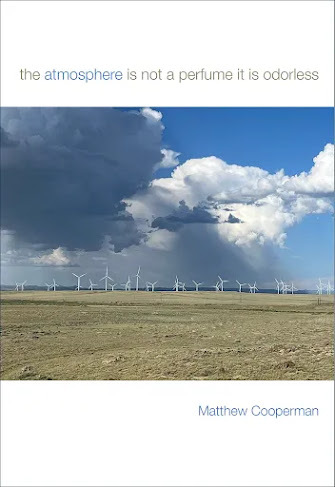

Matthew Cooperman, the atmosphere is not a perfume it is odorless

Precarity

To see and be seen

by others

not the voice

but the face

voice in the face

mouthward

the warbler

now

in the coffee tree

broken and free

*

In hunger by migration

to see the living

and be seen

to have taken it in

the scene and all

its decline

the moving picture

in sepia hues

the map made body

blushing blue

blood a precipitate folly

in wheat or oil

rainfall’s mean

in the morning dew

Forsome time now, I’ve admired Fort Collins poet and editor Matthew Cooperman hisability to compose book-length collections, and even certain poems and individuallines, of sprawling distance, ecological concern, geographic acknowledgement,cultural touchstones and lyric expansiveness, all set in a Colorado he lovesdearly. The author of a handful of titles, including Spool (Anderson SC:Free Verse Editions/Parlor Press, 2016),

NOS (disorder, not otherwise specified)

(with Aby Kaupang; Futurepoem, 2018) [see my review of such here] and

Wonder About The

(Middle Creek Publishing, 2023) [see my review of such here], his latest solo collection is

the atmosphere is not a perfume it is odorless

(Anderson SC: Free Verse Editions/Parlor Press,2024). The lyrics of the atmosphere is not a perfume it is odorless weaveand incorporate strands of contemporary and cultural alongside accompanying full-colourphotographs that feel as much as part of the text as the writing, extending asense of time and timelessness, but one that stretches his lyric of human destructionof the landscape to one that includes even deeper anxiety, citing gun culture,politics and domestic matters. “Innocence,” he writes, across the extendedtitle poem, “being, / lost or being found out, my sense of time goes in and outof phase with // what must be yours, I know I feel it, dispersed and sometimesnot / dispersed, as if I am gas also speaking to you, which of course I am, /the punchline of poetry. Are we always going to go over how I or you // do ornot smell the haloing over the Front Range?”

Forsome time now, I’ve admired Fort Collins poet and editor Matthew Cooperman hisability to compose book-length collections, and even certain poems and individuallines, of sprawling distance, ecological concern, geographic acknowledgement,cultural touchstones and lyric expansiveness, all set in a Colorado he lovesdearly. The author of a handful of titles, including Spool (Anderson SC:Free Verse Editions/Parlor Press, 2016),

NOS (disorder, not otherwise specified)

(with Aby Kaupang; Futurepoem, 2018) [see my review of such here] and

Wonder About The

(Middle Creek Publishing, 2023) [see my review of such here], his latest solo collection is

the atmosphere is not a perfume it is odorless

(Anderson SC: Free Verse Editions/Parlor Press,2024). The lyrics of the atmosphere is not a perfume it is odorless weaveand incorporate strands of contemporary and cultural alongside accompanying full-colourphotographs that feel as much as part of the text as the writing, extending asense of time and timelessness, but one that stretches his lyric of human destructionof the landscape to one that includes even deeper anxiety, citing gun culture,politics and domestic matters. “Innocence,” he writes, across the extendedtitle poem, “being, / lost or being found out, my sense of time goes in and outof phase with // what must be yours, I know I feel it, dispersed and sometimesnot / dispersed, as if I am gas also speaking to you, which of course I am, /the punchline of poetry. Are we always going to go over how I or you // do ornot smell the haloing over the Front Range?”Coopermanwrites of an American cultural expansiveness, even through one of deep uncertainty.“As in, O America, aren’t you tired of being an ode,” he offers, as part of “GunOde.” He writes of precarity and odes, through poems examine and explore culturalspace and seek out its humanity, aching to flesh out something different acrossthe habits of decades. Later, in the same extended poem, writing: “If the impulseto destruction is greater than the insight to love / we are doomed to a gardenof graves // If freedom is money spent on guns, what is American grace?” Hispoems stretch as endless as does that view, which is glorious and open, a tingeof fresh, cool air among the biting dust.

Inthe end, his is a love for country, culture and space as deep and as wide asany horizon, one unafraid to love critically and out loud. “Not motive orasseveration. Not a result of living as experiment,” he writes, as part of “NoOde,” “but living together. Every lab a vial filled. Not a sea / full of oil,nor an office full of bluster. Not a corporation / nor the October morningmoving / to incorporate a neighborhood.”

August 9, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Tāriq Malik

Tāriq Malik has worked across poetry, fiction, and artfor the past four decades to distill immersive and compelling narratives thatare always original. He writes intensely in response to the world in fluxaround him and from his place in its shadows. His published works,including Rainsongs of Kotli (TSAR Publications,short stories, 2004), Chanting Denied Shores (Bayeux Arts,novel, 2010), and now his poetry in Exit Wounds (Caitlin Press, Poetry, 2022)and Blood of Stone (Caitlin Press, Poetry, 2024), challengeentanglements in the barbed wires of racism and cultural stereotyping in art,the workplace and across societies.

Tāriq Malik is thecurrent Writer-in-Residence at the Polyglot Magazine and a formerWriter-in-Residence (July 2023) at the Historic Joy Kogawa House and hasoffered Poetry Master Classes at various locations.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recentwork compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first published book, Rainsongs of Kotli, was a compilation ofloosely interwoven short stories set in the backwaters of Pakistani Punjab. Itwas challenging to describe the work and situate it for potential publishers. Ireceived several very negative responses. Eventually, Rainsongs of Kotliwas published by Toronto-based TSAR Publications in 2004, and that gave meconfidence in my creative voice.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction ornon-fiction?

Rainsongs of Kotli, my first published work, began as a longpoem that evolved into a historical fiction. However, I retained a few originalpoetic sections and transformed them into prose.

My next book was based on the Komagata Maru saga, Chanting DeniedShores. In it, I included a handful of poems to vivify the narrative andserve as an itinerant poet's voice.

I ventured wholly into poetry for my third and fourth books, ExitWounds and Blood of Stone. By then, I had some confidence in mypoetic voice and was now less concerned about how these works would bereceived. I am glad I was able to make the transition to poetry and find myreaders.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Doesyour writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first draftsappear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out ofcopious notes?

I write almost daily, relying on my biphasic sleep patterns, and puttingwork together to submit is very often slow and laborious. While immersed inthis lonely process, I feel empowered and sustained by the writing's drive,passion, and truth. At no point do I consider the reader's response to mynarrative my sole concern, as this often gets in the way of the writing. If Ido my task well enough, the reader will find my writing accessible and thenwillingly take the journey with me.

I tend to overwrite, hence there are several drafts, from which I laterdistill the work to its bare essence before the final submission.

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you anauthor of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are youworking on a "book" from the very beginning?

Since my natural state as a poet is ekphrastic, I usually begin with ascene or an image. A piece of dialogue may inspire me to move onto the page andput down my personal take or view of the situation. The writing then dribblesin and is worked into a coherent whole (or incoherent whole, if I amdeliberately risking obscurity). For me, the volta is often as compelling asection of the poem as the point of the reader's entry into it, even more so.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Areyou the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I enjoy public readings immensely as the writer's voice introduces anuance that the written word does not always convey. I also find that there isa significant challenge in reading concrete poems where the visual aspect ofthe phrase is a vital part of the work. However, given the subjective nature ofmy writing and its narrow focus on unfamiliar themes, I am rarely offered opportunities to read my own work.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kindsof questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even thinkthe current questions are?

I try to amplify a personal experience and viewpoint and attempt tovivify these for the reader.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in largerculture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer shouldbe?

One of the roles of the writer in our culture is to engage with thesocial areas of concern/friction/intersection that are often outside thereaders' sphere and then to elucidate these emotional and intellectualexperiences in an engaging, enlightening, and entertaining manner.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficultor essential (or both)?

I have not yet had the fortune to work substantially with any editor formy fiction.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily givento you directly)?

Be true to your art even if it does not find fertile soil to land on andflourish.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry toshort stories to the novel)? What do you see as the appeal?

My fiction is heavily laced with my poetics. My poetry is mostlyconcrete and narrative based.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you evenhave one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

My writing day begins at around 4am.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for(for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Look for inspiration in writing I admire, primarily Urdu poet Faiz Ahmad Faiz for his rhythms. Lately, I am returning for inspiration in the poetry ofValzhyna Mort, Andrea Cohen, Laura Ritland, Tolu Oloruntoba, et al.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Petrichor, in other words, Blood of Stone.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but arethere any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science,or visual art?

Nature, science, and visual arts are all inspirational for me. I amexcited to be working on a poetry chapbook on the wisdom of trees, anotherinspired by ravens.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, orsimply your life outside of your work?

Robert Macfarlane (any of his multi-faceted writing), Pankaj Mishra's Fromthe Ruins of Empire, Loren Eiseley's The Unexpected Universe, E. L.Doctorow's Ragtime.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Write a play or a screenplay, or collaborate on a creative project inthis field.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would itbe? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had younot been a writer?

I have held scores of jobs before turning to writing: Plant chemist,candy factory worker (mercifully only one day), a nightshift at the pillowfactory stuffing down feathers (four months), industrial lab chemist (17 years)

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I did not find any writings that related to my subjective livedexperience.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last greatfilm?

Colum McCann's awesome Apeirogon.

A favorite TV series: The latest incarnation of The Talented Mr.Ripley (titled simply as Ripley).

20 - What are you currently working on?

I am busy with a poetry book tentatively titled STALAG NOW thatexplores the global consolidation of influence and wealth in the hands ofever fewer individuals and organizations, often in collusion with the military,and the experiences of the precariat societies living under these conditions.

My next novel, Blood Towers, will present an ant's POV ofconstructing glass pyramids in the desert sands to fulfill the wet dreams oflatter-day pharaohs.

I am also working on a sophomore outing for my short story collection ofRainsongs of Kotli.