Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 42

September 7, 2024

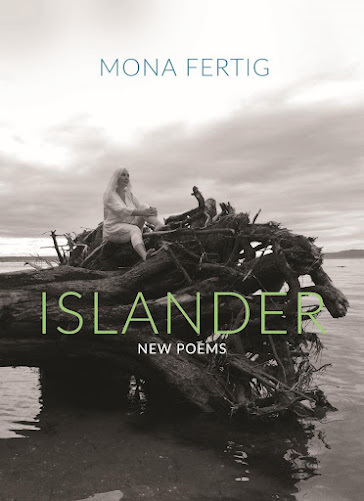

Mona Fertig, Islander: New Poems

I Follow the Arrows inthe Aisles

At Mouats / the windpatiently blows the flag half-mast and

everyone is strangelycalm / the clock tower reads ten to two

in the grocery store / I can’tfind goat yogurt or toilet paper

I follow the arrows inthe aisles / on the floor / making sure I do not

cohabit space / hug afriend

make contact / only withmy eyes / cotton mask over mouth and nose

I follow the arrows inthe aisles

everyone is strangely calm/ adjusting to plexiglass / drinking like a fish

circling home like bordercollies / washing hands like raccoons

there is no safe room tohide in / no virus-free shelter

we adapt to survive / streamlike a squall / devour desserts like queens

disoriented / breathless/ we take Sunday drives / reroute our lives

garden like addicts /zoom in our cocoons

discover online shopping.

Salt Spring Island poet and publisher Mona Fertig, the author of more than a dozen booksand chapbooks of poetry going back to the 1970s, offers herself as a “Poet Returningto Form” in her latest, the collection

Islander: New Poems

(Salt SpringIsland BC: Mother Tongue Publishing Limited, 2024). This is her attempting herway, as she describes, back into the lyric, as her first-person poems offer anintimacy across the immediate geography and landscape of her surroundings,articulating a casual exploration of words that had been previously lost. “Afterdecades of publishing other writers,” she offers, as part of her “Afterword,” “Ihad decided there was still one more book of poetry in me.” Islander: NewPoems appears to be her first full-length collection since

The Unsettled

(2010), as she writes of joy and grandchildren, the village in spring, flowersand rain, as well as the strange distances required through pandemic lockdown. “theboat bobs all winter,” she writes, as part of the sequence “Folklore IsTradition,” “a maple-and-alder-filled hearth /smokes from the chimney //they enter the heart of the house // sleeping till spring.” Composed asa kind of lyric journal, she writes narrative stretches of meditation and description,the physical space and situation of her island, offering a love song to a spaceand a community. Further in her “Afterword,” she writes:

Salt Spring Island poet and publisher Mona Fertig, the author of more than a dozen booksand chapbooks of poetry going back to the 1970s, offers herself as a “Poet Returningto Form” in her latest, the collection

Islander: New Poems

(Salt SpringIsland BC: Mother Tongue Publishing Limited, 2024). This is her attempting herway, as she describes, back into the lyric, as her first-person poems offer anintimacy across the immediate geography and landscape of her surroundings,articulating a casual exploration of words that had been previously lost. “Afterdecades of publishing other writers,” she offers, as part of her “Afterword,” “Ihad decided there was still one more book of poetry in me.” Islander: NewPoems appears to be her first full-length collection since

The Unsettled

(2010), as she writes of joy and grandchildren, the village in spring, flowersand rain, as well as the strange distances required through pandemic lockdown. “theboat bobs all winter,” she writes, as part of the sequence “Folklore IsTradition,” “a maple-and-alder-filled hearth /smokes from the chimney //they enter the heart of the house // sleeping till spring.” Composed asa kind of lyric journal, she writes narrative stretches of meditation and description,the physical space and situation of her island, offering a love song to a spaceand a community. Further in her “Afterword,” she writes:I’ve always been a veryslow writer. A poem sometimes took years to finish. But the opposite happenedwith Islander. A multiplex of new poems emerged over a year to mix witha handful of drafts I had started in earlier times, and two long sociopoliticalpoems I’d written in 2018 and 2020. I relaxed into this humble wave. It was awarm welcome back.

September 6, 2024

VERSe Ottawa, in conjunction with the City of Ottawa, is pleased to announce the incoming 2024-2026 City of Ottawa Poets Laureate:

FORIMMEDIATE RELEASE: VERSe Ottawa, in conjunction with the City of Ottawa, is pleased to announce the incoming2024-2026 City of Ottawa Poets Laureate

David O’Meara (English)

Véronique Sylvain

(French)

David O’Mearais the author of five collections of poetry, most recently Masses On Radar(Coach House Books, 2021). His play, Disaster, was nominated for fourRideau Awards. He is a winner of the Ottawa Book Award and the ArchibaldLampman Prize, is the director of The Plan 99 Reading Series, was the foundingArtistic Director for VERSeFest (Canada’s International Poetry Festival), andwas a jurist for the 2012 Griffin International Poetry Prize. In 2016 he wasawarded the Ottawa Arts Council Mid-Career Artist Award. His debut novel, Chandelier,appears in September 2024.

Véronique Sylvain [photo credit: Richard Tardif] lives in Ottawa, whereshe holds the position of promotion and communications agent with ÉditionsDavid. Her poems have been published in À ciel ouvert, Ancrages, Femmesde parole, Zinc, and in the anthologies Poèmes de la résistance(Prise de parole, 2019) and Projet TERRE (David, 2021). Her firstcollection, Premier quart (Prise de parole, 2019), won her the Prix depoésie Trillium, the Ottawa Book Prize, in 2020, the Prix Champlain, and thePrix littéraire émergence AAOF 2021. A proud Franco-Ontarian with a passion forwords, music, nature, and travel, Véronique also offers writing workshops forthose aged 8 to 98. Her upcoming collection,

En terrain miné

, appears inSeptember 2024.

Véronique Sylvain [photo credit: Richard Tardif] lives in Ottawa, whereshe holds the position of promotion and communications agent with ÉditionsDavid. Her poems have been published in À ciel ouvert, Ancrages, Femmesde parole, Zinc, and in the anthologies Poèmes de la résistance(Prise de parole, 2019) and Projet TERRE (David, 2021). Her firstcollection, Premier quart (Prise de parole, 2019), won her the Prix depoésie Trillium, the Ottawa Book Prize, in 2020, the Prix Champlain, and thePrix littéraire émergence AAOF 2021. A proud Franco-Ontarian with a passion forwords, music, nature, and travel, Véronique also offers writing workshops forthose aged 8 to 98. Her upcoming collection,

En terrain miné

, appears inSeptember 2024.The City of Ottawa’s Poet Laureateprogram is designed to promote the literary arts in Ottawa and to advanceOttawa’s unique voice in the world. Poets laureate serve a two-year termbeginning in September.

ABOUT THE CITY OFOTTAWA’S POET LAUREATE PROGRAM

In 2017, City Council approvedfunding for the renewal of a Poet Laureate Program for the City of Ottawa.There are two current Ottawa poet laureates – one English, one French – eachappointed to serve a two year term. Their mandate is to act as Ottawa’sartistic ambassador, to promote the literary arts, and to advance Ottawa’sunique voice in the world.

Each Poet Laureate receives anannual honorarium of $5,000, as well as another $5,000 to fund variouspoetry-related programs and events.

HISTORY OF OTTAWA’SPOET LAUREATE PROGRAM

Before the present incarnation of abilingual Poet laureate program, Ottawa had an unilingual poet laureate programbetween 1982 and 1990. The city’s third and final poet laureate under thisprogram was Patrick White, who succeeded Cyril Dabydeen. The city’s first poetlaureate was Catherine Ahearn, a position which also made her the firstmunicipal poet laureate in Canada. After an almost 30-year hiatus, City Councilin consultation with VERSe Ottawa resurrected and augmented the Poet Laureateprogram.

Previous PoetsLaureate

2021/2022

Albert Dumont (Anglophone Poet Laureate)

Gilles Latour (Francophone Poet Laureate)

2019/2020

Deanna Young (Anglophone Poet Laureate)

Margaret Michèle Cook (Francophone Poet Laureate)

2017/2018

Andrée Lacelle (Francophone Poet Laureate)

Jamaal Jackson Rogers (Anglophone Poet Laureate)

For media requests for DavidO’Meara, VERSe Ottawa or questions about the Poet Laureate program, contact robmclennan: rob_mclennan@hotmail.com

For media requests for VéroniqueSylvain, contact Christine McNair: christine_mcnair@hotmail.com

September 5, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Noah Berlatsky

Noah Berlatsky

(he/him) is a freelance writer in Chicago. His first full length collection is

Not Akhmatova

(Ben Yehuda Press, 2024). He has chapbooks published and/or forthcoming with the Origami Poems Project, above/ground, and LJMcD Communications. He is also the author of

Wonder Woman; Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics, 1941-48

(Rutgers UP, 2014.)

Noah Berlatsky

(he/him) is a freelance writer in Chicago. His first full length collection is

Not Akhmatova

(Ben Yehuda Press, 2024). He has chapbooks published and/or forthcoming with the Origami Poems Project, above/ground, and LJMcD Communications. He is also the author of

Wonder Woman; Bondage and Feminism in the Marston/Peter Comics, 1941-48

(Rutgers UP, 2014.)1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I've been trying to be a poet for like 30 years with little success, so it's been validating? Pleasing? I wouldn't say it's changed my life, but it's nice to feel like some small number of people are reading words I wrote.

I've always been a stylistically scattershot poet; Not Akhmatova is more formal/less experimental than some of my work, in part because it's sort of translations. But I've also written in this vein before...I wouldn't say there's a big line or anything, but I guess for people who prefer less experimental poems, this would be the place to start with my work.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I write a lot of non-fiction; that's my day job. And I've occasionally written fiction on and off over the years. I'm not sure there was one moment when I decided poetry was something I would do; I started really writing poetry in college, and then I guess I just kept going. I like the way that poetry can be short (my attention span is limited!) And I like the way it can be kind of anything you want it to be; rhyming quatrains, sonnets, collage, weird lists. It appeals to my twitchiness.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I try to write at least a little bit of poetry every day, so I'm always working on something. When I first started writing poetry I was very slow—the first poem I wrote I'm really happy with took like 6 months to write 20 lines and I probably filled three or four notebooks with drafts. That was frustrating and I don't do that any more! Twenty years of writing on deadline every day, day after day, really knocks the perfectionism out of you, so when I returned to writing poetry a couple years ago I discovered that I can write really fast (as poetry goes anyway.)

Not Akhmatova came in pretty quick bursts; I wrote half the ms in probably a month. Then when Ben Yehuda press said they were interested, I thought I might write a few more poems to fill out the ms, and ended up writing like another 30-40 pages in a week while on vacation in Portland. Which was really fun, actually (the vacation and writing the poems both.)

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

It can begin in a lot of ways; with a little phrase, or an idea, or a conceptual approach, or by being inspired by something I've read. (I'm working on a piece sort of inspired by John Ashbery's book Flow Chart, which I just read and loved.) I sometimes write one offs, but I also not infrequently have ideas that can be spun out into chapbooks or books. I've got...like four full length manuscripts sitting around, and maybe the same number of chapbooks? So I'm often working on books, though most will probably never be published, I'd guess.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I like doing readings pretty well; I don't get the opportunity very often, though.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I have various things I'm thinking about in different projects. Not Akhmatova is about nationalism and diaspora identity in large part. My family's from Russia originally, and so Akhmatova is sort of part of my poetic heritage, or would be if my Russian Jewish ancestors hadn't fled Russia for the reasons that Jewish people generally fled Russia. So the book is thinking about who gets to lay claim to language and history, how translations connect you to tradition and alienate you, whether poetry needs to be rooted in tradition or what that expectation means.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Writers have a range of roles I think. Since I write for a living, I'm very aware of writing as just another kind of work, producing things that people pay for (or don't.) Writing is also art, and art is a complicated thing; people look to it for meaning, distraction, entertainment, status, political validation, self-recognition. With my poetry, I'm generally trying to write things that seem truthful/meaningful to me and that might amuse the small number of people who read my poems. Not sure I can claim much more for it than that.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

It depends. I work with editors all the time in freelancing. Working with the editor at Ben Yehuda Press was helpful; they were very respectful and it was good to get a read on how alienating some of the more experimental poems in the collection were or weren't.

On the other hand, I just had a miserable experience with a press that accepted my ms and then the editor made a bunch of changes without telling me?! Like, cutting out words and changing line breaks, I guess because they felt readers of poetry would be put off by long lines?! Anyway, when I pushed back and said they did in fact have to at least mark any changes so I could sign off on them, they cancelled the contract. Which was for the best, but also wtf?

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

I always tell people that the best advice for a writer is to be born rich. If you can't manage that you're mostly screwed, so...

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to non-fiction to journalism)? What do you see as the appeal?

I think there's a good bit of overlap. The appeal is first that you can't get paid for poetry, so if you're trying to make a living you better write other things! Also though I like taking on different kinds of projects and doing different kinds of writing; I get bored if I do one thing all the time.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Well, I have to write essays every day for work pretty much. I usually do that first, and then try to write a little poetry in the afternoon or evening. Being a freelancer means that I just work all the time. Sometimes I take a break to walk the dog.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Again, after 20 years of writing every day on deadline, I don't get stalled out much. Reading poetry is usually a good way to kickstart writing poetry for me; I just read Robert Creeley's selected poems for example and wrote a bunch of creeley-ish things.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

I have allergies and barely any sense of smell, alas.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I write a lot of movie/music criticism, so that influences my writing. I write a certain number of poems about the pets too (we've got a pitbull and four kitties.)

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Well, the most important writer for Not Akhmatova was Akhmatova, obviously! James Baldwin is a big influence on my nonfiction and film writing. I love Adelaide Crapsey's cinquains; I've got an ms of cinquains I've been working on here and there for a year or two.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

It'd be nice to get some of these other manuscripts published! It would be fun to teach a poetry class, maybe, though I don't really see that happening. I'd love get a grant and just have time to focus on poetry; probably I'll have to wait for retirement for that though.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I thought about being an academic. That would probably be the thing if I weren't a freelance writer.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I just read too much as a kid. Broke me for anything else.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I just finished John Ashbery's Flow Chart, which is amazing. I'm in the middle of Kate Atkinson's Shrines of Gaiety, which is really good. Before that read Saidiya Harman's Lose Your Mother, about her trip to Ghana and alienation and displacement as one permanent legacy of slavery; it's great. I'm still processing it.

The last great film... Drive-Away Dolls is my favorite film of the year I think. I saw the Blair Witch Project again this week. Elliot Page's Close To You is wonderful.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I'm farting around with this longish collage piece somewhat inspired by Flow Chart, with each stanza as a longish sentence. It's keeping me busy!

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

September 4, 2024

end-of-summer something-something, : sainte-adèle

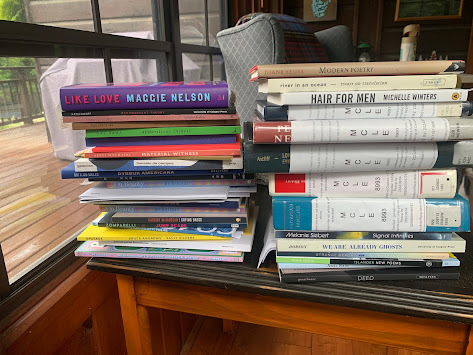

It took us five months [see when we were here last], but we managed another away-weekend at mother-in-law's cottage. Christine, our young ladies and our persnickety cat, Lemonade, three days of Sainte-Adèle, Quebec, just up along the Laurentides. As ever, the leaves were already beginning to turn (before they do back in Ottawa). Naturally, I now approach such awayness-ess as marathon reading sessions, where I attempt to make first-notes on as many books as possible towards potential reviews (I did get through about half of this stack, if you can imagine, although I was also focused on edits on the manuscript-so-far of "the green notebook," my day-book in-progress).

It took us five months [see when we were here last], but we managed another away-weekend at mother-in-law's cottage. Christine, our young ladies and our persnickety cat, Lemonade, three days of Sainte-Adèle, Quebec, just up along the Laurentides. As ever, the leaves were already beginning to turn (before they do back in Ottawa). Naturally, I now approach such awayness-ess as marathon reading sessions, where I attempt to make first-notes on as many books as possible towards potential reviews (I did get through about half of this stack, if you can imagine, although I was also focused on edits on the manuscript-so-far of "the green notebook," my day-book in-progress).

The Maggie Nelson title,

LIKE LOVE

(2024), was a particular highlight, although there were certainly others (watch my reviews across the next few weeks). I've noticed over the past few years that I tend to pick up a longer book of prose or two for such trips such as these for my reading attention, whether Anne Boyer, Elisa Gabbert, Sarah Manguso or, now, Maggie Nelson, for poolside in Picton, or either in sunroom or on the porch of Sainte-Adèle. I haven't the opportunity for longer prose these days, otherwise (unless stepping onto a flight or a train, which I also get rather excited about, due to the potential for reading). Christine read her mysteries and worked on some things; I moved through a mound of new titles (mostly poetry titles) and worked on some things. The young ladies played downstairs for a bit, ran around for a bit; Rose is reading a series of young adult journals (not sure if fiction or non-fiction, I haven't looked at too closely), including one referencing the War of 1812, so she's learning all sorts of interesting things (that she is telling us, naturally). I am intrigued by what she is picking up.

The Maggie Nelson title,

LIKE LOVE

(2024), was a particular highlight, although there were certainly others (watch my reviews across the next few weeks). I've noticed over the past few years that I tend to pick up a longer book of prose or two for such trips such as these for my reading attention, whether Anne Boyer, Elisa Gabbert, Sarah Manguso or, now, Maggie Nelson, for poolside in Picton, or either in sunroom or on the porch of Sainte-Adèle. I haven't the opportunity for longer prose these days, otherwise (unless stepping onto a flight or a train, which I also get rather excited about, due to the potential for reading). Christine read her mysteries and worked on some things; I moved through a mound of new titles (mostly poetry titles) and worked on some things. The young ladies played downstairs for a bit, ran around for a bit; Rose is reading a series of young adult journals (not sure if fiction or non-fiction, I haven't looked at too closely), including one referencing the War of 1812, so she's learning all sorts of interesting things (that she is telling us, naturally). I am intrigued by what she is picking up. And apparently one of her school-mates taught Rose chess at one point (which she was then teaching her wee sister), which she only pointed out at seeing Oma's chessboard (you know we have one at home, right? apparently she did not). We played a few games, and she's not bad. I remember teaching my eldest when she was just a bit younger than Rose is now, and we had that as part of our weekly routine for Saturdays, the travel-board we'd pull out in the food court of the Rideau Centre. I suppose I'll have to pull that out now for Rose.

And apparently one of her school-mates taught Rose chess at one point (which she was then teaching her wee sister), which she only pointed out at seeing Oma's chessboard (you know we have one at home, right? apparently she did not). We played a few games, and she's not bad. I remember teaching my eldest when she was just a bit younger than Rose is now, and we had that as part of our weekly routine for Saturdays, the travel-board we'd pull out in the food court of the Rideau Centre. I suppose I'll have to pull that out now for Rose.September 3, 2024

Spotlight series #101 : Michael Boughn

The one hundred and first in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Toronto poet and editor Michael Boughn

.

The one hundred and first in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Toronto poet and editor Michael Boughn

.The first eleven in the series were attached to the Drunken Boat blog, and the series has so far featured poets including Seattle, Washington poet Sarah Mangold, Colborne, Ontario poet Gil McElroy, Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Ottawa poet Jason Christie, Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough, Ottawa poet Amanda Earl, American poet Elizabeth Robinson, American poet Jennifer Kronovet, Ottawa poet Michael Dennis, Vancouver poet Sonnet L’Abbé, Montreal writer Sarah Burgoyne, Fredericton poet Joe Blades, American poet Genève Chao, Northampton MA poet Brittany Billmeyer-Finn, Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer from Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1 territory) poet, critic and editor Joshua Whitehead, American expat/Barcelona poet, editor and publisher Edward Smallfield, Kentucky poet Amelia Martens, Ottawa poet Pearl Pirie, Burlington, Ontario poet Sacha Archer, Washington DC poet Buck Downs, Toronto poet Shannon Bramer, Vancouver poet and editor Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Vancouver poet Geoffrey Nilson, Oakland, California poets and editors Rusty Morrison and Jamie Townsend, Ottawa poet and editor Manahil Bandukwala, Toronto poet and editor Dani Spinosa, Kingston writer and editor Trish Salah, Calgary poet, editor and publisher Kyle Flemmer, Vancouver poet Adrienne Gruber, California poet and editor Susanne Dyckman, Brooklyn poet-filmmaker Stephanie Gray, Vernon, BC poet Kerry Gilbert, South Carolina poet and translator Lindsay Turner, Vancouver poet and editor Adèle Barclay, Thorold, Ontario poet Franco Cortese, Ottawa poet Conyer Clayton, Lawrence, Kansas poet Megan Kaminski, Ottawa poet and fiction writer Frances Boyle, Ithica, NY poet, editor and publisher Marty Cain, New York City poet Amanda Deutch, Iranian-born and Toronto-based writer/translator Khashayar Mohammadi, Mendocino County writer, librarian, and a visual artist Melissa Eleftherion, Ottawa poet and editor Sarah MacDonell, Montreal poet Simina Banu, Canadian-born UK-based artist, writer, and practice-led researcher J. R. Carpenter, Toronto poet MLA Chernoff, Boise, Idaho poet and critic Martin Corless-Smith, Canadian poet and fiction writer Erin Emily Ann Vance, Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi, Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, Canadian poet Peter Jaeger, Birmingham, Alabama poet and editor Alina Stefanescu, Waterloo, Ontario poet Chris Banks, Chicago poet and editor Carrie Olivia Adams, Vancouver poet and editor Danielle Lafrance, Toronto-based poet and literary critic Dale Martin Smith, American poet, scholar and book-maker Genevieve Kaplan, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic ryan fitzpatrick, American poet and editor Carleen Tibbetts, British Columbia poet nathan dueck, Tiohtiá:ke-based sick slick, poet/critic em/ilie kneifel, writer, translator and lecturer Mark Tardi, New Mexico poet Kōan Anne Brink, Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Melanie Dennis Unrau, Vancouver poet, editor and critic Stephen Collis, poet and social justice coach Aja Couchois Duncan, Colorado poet Sara Renee Marshall, Toronto writer Bahar Orang, Ottawa writer Matthew Firth, Victoria poet Saba Pakdel, Winnipeg poet Julian Day, Ottawa poet, writer and performer nina jane drystek, Comox BC poet Jamie Sharpe, Canadian visual artist and poet Laura Kerr, Quebec City-area poet and translator Simon Brown, Ottawa poet Jennifer Baker, Rwandese Canadian Brooklyn-based writer Victoria Mbabazi, Nova Scotia-based poet and facilitator Nanci Lee, Irish-American poet Nathanael O'Reilly, Canadian poet Tom Prime, Regina-based poet and translator Jérôme Melançon, New York-based poet Emmalea Russo, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic Eric Schmaltz, San Francisco poet Maw Shein Win, Toronto-based writer, playwright and editor Daniel Sarah Karasik, Ottawa poet and editor Dessa Bayrock, Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia poet Alice Burdick, poet, writer and editor Jade Wallace, San Francisco-based poet Jennifer Hasegawa, California poet Kyla Houbolt, Toronto poet and editor Emma Rhodes, Canadian-in-Iowa writer Jon Cone, Edmonton/Sicily-based poet, educator, translator, researcher, editor and publisher Adriana Oniță, California-based poet, scholar and teacher Monica Mody, Ottawa poet and editor AJ Dolman, Sudbury poet, critic and fiction writer Kim Fahner, Canadian poet Kemeny Babineau and Indiana poet Nate Logan.

The whole series can be found online here .

September 2, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jes Battis

Jes Battis (they/them) teaches literature andcreative writing at the University of Regina. They’ve published poems in TheEx-Puritan, The Malahat Review, The Capilano Review and Poetry Is Dead, amongother literary magazines. They’ve also published creative nonfiction in The LosAngeles Review of Books and Strange Horizons. They are the author of the OccultSpecial Investigator series (shortlisted for the Sunburst Award), the ParallelParks series and, most recently, The Winter Knight with ECW.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does yourmost recent work compare to your previous? How does it feeldifferent?

My first book was academic (a study of horror television),and then my first novel, Night Child, was a forensic thriller. That book was life-changing in a way, becauseit got some attention and made me wonder if I could write full-time and supportmyself (I couldn’t). I Hate Parties ismy debut poetry collection, and it’s made a more subtle appearance, with someevents scheduled and a few interviews. But I think poetry tends to feel a bit more quiet and reflective than anovel, which always requires a marketing push.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say,fiction or non-fiction?

I came to fiction first, though I started writing poetrywhen I was fairly young. I have moreexperience working with fiction, but I’ve been warming up to poetry, and I’vebeen publishing poems in the background for almost a decade. I think a lot of writers hesitate to callthemselves poets, even when they have a collection or two out in theworld. A friend had to assure me that Iwas a poet, and so I reluctantly believe her.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writingproject? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Dofirst drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work comeout of copious notes?

A poem usually appears with an image, or a line that I addto my notes app (or scrawl down in a notebook if I don’t want to grab myphone). The draft poem will usuallycoalesce pretty quickly around that line—I’ll hammer out something very roughin one sitting, and then keep coming back for edits. Sometimes I have to sneak up on a poem tofigure out what it’s really doing, and that can take anywhere from a few editsto several years. With fiction, I’llusually fumble through a first draft over the course of a few months, and thenspend about a year or more in edits, until it’s ready to show someone.

4 - Where does a poem or work of fiction usually begin foryou? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a largerproject, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

With I Hate Parties, the title poem ended up beingcentral, but it was written fairly late compared with the other poems. Sometimes several poems will set a kind ofmood, and then the work involves figuring out how to attach them to similarpoems, but the mood itself can be enigmatic. My editors told me that these poems were about anxiety, which I supposeI did know, but it helps to hear it from an outside reader as well. With fiction, I usually see a scene or a fewlinked scenes, and then I spend a lot of time thinking who those flashes ofcharacter might be, and how they can populate the scenes in a meaningfulway. Some characters will still appearlate in the game and surprise you.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creativeprocess? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I do like reading—both poetry and prose—because there’s aperformance aspect to it that can be quite fun. I always learn a bit more about the work by reading it. But reading personal/lyrical poetry can alsobe challenging, and I’m not always sure if a poem wants to be read aloud untilI’m in the middle of it. Festivals canbe energizing but also extremely draining, and I always need a few days torecover.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind yourwriting? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? Whatdo you even think the current questions are?

I’m a queer, nonbinary, autistic person, and all of thoseways of being are regularly challenged by conservative governments and medicalableism. I’m inspired by theorists likeEli Clare, Lauren Berlant, and Sara Ahmed, who talk about the regulatory forcesthat are always trying to write queer, trans, and disabled people out ofexistence. I think it’s still rare tosee queer autistic representation, in spite of the fact that I have so manyfriends who are queer, trans, and neurodiverse in some way. In general, I try to approach questions thatI’ve always found challenging, like: Howdo people communicate with each other? How do we experience time and space in different ways? What does it mean to be social? What does it mean to experience gender in acreative way? How can we be fiercelyqueer and trans in conservative spaces that would rather we not exist?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being inlarger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writershould be?

I’m not sure there’s one role for a writer, but our conceptof “writer” is heavily involved in capitalism and colonialism. Maybe one role or goal of writing is tochallenge that. For some, existing as awriter is an act of resistance—existing at all—is an act of resistance. I don’t think queer and trans writers “owe” aparticular kind of story to a particular audience, but we can certainly modeldifferent stories and lives for a variety of readers. We should also ask what the publishingindustry owes us as writers who engage in traditional publishing. A living wage, and freedom to criticize thesystems that facilitate our erasure, seems like a good start.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outsideeditor difficult or essential (or both)?

A good editorial relationship, even if it’s transactional,can improve your work and even help you get to the bottom of what you’re tryingto say. When I first receive aneditorial memo or feedback, it can be a bit overwhelming. But good editors will work with youpatiently, and respect your voice as a writer. Still—don’t be afraid to write stet (“let it stand”) next to aline or sentence that you want to keep, even if your copy-editor doesn’tnecessarily get it.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (notnecessarily given to you directly)?

Annie Dillard says, in her manual on writing, that we shouldall write the stories that we’ve never heard before—the ones clawing to getout. I do think it’s good to writethings that scare you, and things that make you feel simultaneously seen andvulnerable. Writing for a community canbe helpful (and challenging); writing for a specific audience or marketingdemographic will often just get in the way of the story you want to tell andneed to hear.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres(poetry to fiction to essays)? What do you see as the appeal?

I think both poetry and fiction can sharequalities—particularly the idea of confession—but poetry sometimes feels a bitmore urgent. Conversely, it can also beenigmatic enough to surround a difficult moment in syntactic bubble wrap, soyou can approach it and re-experience it more easily. Both essays and poems can challenge ideas ofcentrality and chronology as well—Michael Trussler does this in lovely ways inwork like The Sunday Book.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or doyou even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

This depends on health, schedule, energy, and capacity. Generally, I like to write for a bit in themorning, but not every day. If I’m closeto finishing a fiction manuscript, I’ll work on it more regularly, but I stillhave to factor in time off because I can’t write every day. With poetry, it’s a bit more sporadic. I might write several draft poems over thecourse of a few weeks, and then nothing for a month after. I went six years between novels, aswell. The writing always takes longerthan you think it will, and it has to find its way into the cracks. Living can feel like a full-time job, andthere are stretches of time when I’m just trying to exist, but the writing isalways collecting like dust in the background—one day I’ll swipe my fingeracross the mental furniture and realize that there are multiple storiesthere.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn orreturn for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I get a lot of inspiration from working with creativewriting students, though I don’t often write a lot while I’m teaching. But being in proximity to their work can helpto keep the energy circulating. I alsowatch shows with a narrative emphasis, listen to podcasts, and try to read asmuch as I can. The idea of it beingstalled—that writing might be a Ford F150 stuck on the side of the road—is, Ithink, an outgrowth of capitalism. Maybewe can think of it more as resting.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Earl Gray tea, or spaghetti sauce thickening. Also cow shit, because I grew up in a farmtown.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books,but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music,science or visual art?

Music is a big influence for crafting the mood of aparticular scene. I also loveinteracting with animals and seeing how they view the world, and how we cancommunicate when we don’t speak the same language. Well-crafted films can help with narrativework, and bad films can also remind you what to avoid. I also just love wandering around with mypartner, walking through small-town malls, talking pictures of everydaylife—ideas will often materialize when I’m vagabonding.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for yourwork, or simply your life outside of your work?

I grew up on the work of feminist fantasy andscience-fiction writers like Ursula K. Le Guin, Mercedes Lackey, and Tanya Huff—their particular styles helped me to think about the ethics ofworldbuilding. I read a lot of transwriters because their perspective often feels like home to me: Casey Plett, Hazel Jane Plante, Joss Lake,Kai Cheng Thom, Lee Mandelo. In terms ofpoetry, I tend to like narrative poetry with a queer slant: Kayla Czaga, Ben Ladouceur, Saeed Jones, Anne Carson.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Learn Scottish Gaelic to reconnect with part of myheritage. Learn ASL. Keep unmasking socially until I can actuallyjust be who I am in a social setting, without all the internal regulation andanxiety.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, whatwould it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doinghad you not been a writer?

I think I’d enjoy being a librarian, though I’m sure a lotof writers and academics say that. Iactually loved working in a photo lab in the 90s, and wouldn’t mind developingpictures again, if there’s ever some kind of 35mm renaissance.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing somethingelse?

Easy: I would havedied if I couldn’t write.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was thelast great film?

I really enjoyed Any Other City, by Hazel JanePlante. I also loved watching I Sawthe TV Glow and All Of Us Strangers.

20 - What are you currently working on?

A few different projects. A small-town queer romance with witches. A novella about dragons in the nineties. A story about Scottish myths. Anda poetry manuscript focused on TV.

September 1, 2024

Stuart Ross, The Sky Is a Sky in the Sky

JENNY HOLZER

for Kenn Enns

Kennedy, you have

words in your brain

and words surround

you and you buy words

and say words and soon

you will have words on you.

Actual words right onyou.

Jenny Holzer was born in

Gallipolis, Ohio, on July

29, 1950. Kennedy, inked

You will move through

public spaces. When you

reach Gallipolis, youwill

light up and blink.

The latest fromaward-winning Cobourg, Ontario poet, fiction writer, critic, editor, publisher and mentor Stuart Ross is

The Sky Is a Sky in the Sky

(Toronto ON: CoachHouse Books, 2024), a collection assembled, as the back cover offers, as “alaboratory of poetic approaches and experiments. It mines the personal andimaginary lives of Stuart Ross and portraits of his grief and internal torment,while paying homage to many of the poet’s literary heroes.” With so manycontemporary collections seeking to cohere through shared tone or structure, thisseems a highly deliberate miscellany, allowing for what each poem or situationmight require, whether poems that reflect on quieter moments, homages andresponses to friends, including Ottawa poet Stephen Brockwell or the lateOttawa poet Michael Dennis, his late brother Barry, or offering his annual NewYear’s poem, a tradition he’s kept up for a number of years. “In Michael’soffice,” the poem “MICHAEL’S OFFICE” begins, “we are surrounded / by poetry.each passing month, / the space for books expands while / the space for peoplecontracts. You feel / the poems on your clothes, your skin, / and your tongue. Itis paradise.”

The latest fromaward-winning Cobourg, Ontario poet, fiction writer, critic, editor, publisher and mentor Stuart Ross is

The Sky Is a Sky in the Sky

(Toronto ON: CoachHouse Books, 2024), a collection assembled, as the back cover offers, as “alaboratory of poetic approaches and experiments. It mines the personal andimaginary lives of Stuart Ross and portraits of his grief and internal torment,while paying homage to many of the poet’s literary heroes.” With so manycontemporary collections seeking to cohere through shared tone or structure, thisseems a highly deliberate miscellany, allowing for what each poem or situationmight require, whether poems that reflect on quieter moments, homages andresponses to friends, including Ottawa poet Stephen Brockwell or the lateOttawa poet Michael Dennis, his late brother Barry, or offering his annual NewYear’s poem, a tradition he’s kept up for a number of years. “In Michael’soffice,” the poem “MICHAEL’S OFFICE” begins, “we are surrounded / by poetry.each passing month, / the space for books expands while / the space for peoplecontracts. You feel / the poems on your clothes, your skin, / and your tongue. Itis paradise.” He writes ofshadows, mortality and depression; not as an edge but a kind of underlay,ever-present, and impossible to avoid. “That / tingling sensation in my pocket/ is not chewed gum but a cluster / of stupid nouns that,” he writes, as partof the title poem, “joined at the hips, / creates a quivering language /uttered only by clouds.” He includes poems that riff on and respond to particularworks by Nelson Ball, Charles North, Ron Padgett and Chika Sagawa, amongothers, as well as a further poem in his “Razovsky” poems, turning his family’sformer name (before it was shorted to “Ross”) into an ongoing character, one thatemerged in his writing during the 1990s, and first fleshed out as part of hiscollection Razovsky at Peace (Toronto ON: ECW Press, 2001). There’salways been something intriguing about the way Ross has played this particularcharacter, occasionally riffing as a variation on himself (who he might havebeen, perhaps, had his grandfather not anglicized their name), or even as akind of red herring akin to the late New York novelist Paul Auster, introducing“Paul Auster” as a side-character in certain of his books, whether to distract ordistinguish from who the main narrator might truly represent. As Ross’ poem “RAZOVSKYHAS SOMETHING TO SAY” begins:

Razovsky has nevertriumphed

on the esteemed grid

that serves as abattlefield

for tic-tac-toe, nor hashe ever

won a game of chess,thoroughly

cooked an egg, paintedall four walls

of a room (by the time hegets

to the fourth, yearslater,

the first has begun tofade and peel),

or finished reading a TomClancy novel.

He tosses his cigarettesto the sidewalk

half-smoked, and mouldgrows

on the surface ofyesterday’s coffee

that perches on thecorner of his desk.

The collectionmoves in a myriad of directions, providing a poetry title assembled almost as asequence of outreaches, responses and interactions through the form of thelyric. I’ve long appreciated that Ross wears his influences openly, wishing bothto give homage and work in conversation with other writers, other pieces,almost as a way of better understanding a particular work by engaging and respondingto it through writing, and this collection seems entirely built around thatcentral thought. “As James Tate once said,” he writes, as part of the poem “LIFEBEGINS WHEN YOU BEGIN THE BEGUINE,” a poem “for Charles North and RonPadgett,” “‘My cuticles are a mess.’ Inspired, I wrote / a broadway musicalabout cuticles, choreographed / by Busby Berkeley. It closed after just one day/ but changed the lives of those who saw it.”

August 31, 2024

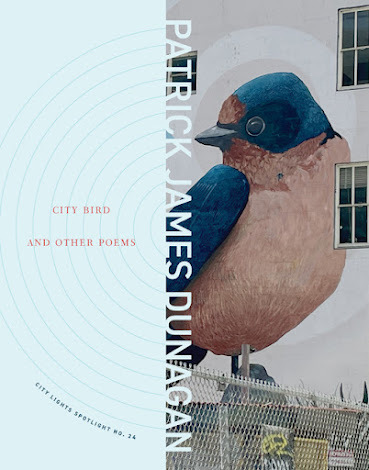

Patrick James Dunagan, City Bird and Other Poems

FOR JOAN BROWN

Artists of California

arrogant and young,destitute in work searching

to have something to say

painting your way out thesame situation for years

you guys mock each otherwhat fluffy puppies

the struggle is not toage your age

just maintain number assymbol or sign

age you refuse representor embody simple

isn’t it art to walk away

doesn’t speak out againststruggles you don’t get

the job isn’t to make itbut to make things make it

and that job is years incoming

if then you find meriding in a Cadillac

understand it ain’t mine atall but possibly

and then typically sounlikely the driver may very well be

slipping betweensedimentary levels for sentiment

give such grapple to holdthe night through

a cartwheel to drive thedraydel

big cats on furry loungesto tempt us

harmony in the backgroundjust like that

lettme hearya now!

Patrick James Dunagan’s latest collection

City Bird and Other Poems

(SanFrancisco CA: City Lights Books, 2024), reveals him as the most San Franciscoof contemporary poets, riffing off a rich history of current and historic SanFrancisco poets, artists and landmarks including Bill Berkson, Lew Welch, JoanneKyger, Sunnylyn Thibodeaux, Joan Brown, Jay DeFeo, O’Farrell Street and St.Anne of the Sunset. “One whispering tales of woe to another / cow as heavenlygargoyle / spring dazzler in mystic’s ear,” he writes, to open the poem “ST.ANNE OF THE SUNSET,” a poem for the century-plus rosy-red Catholic Church inSan Francisco’s Sunset District (an area originally known as the “Outside Lands”),near Golden Gate Park. There is such a sense of wonder through Dunagan’s lyrics,offering first-person laid-back declarations on and around history, awarenessand magic, articulating the ordinary dailyness of existing within such a spaceand place, and the layerings of contemporary and historic movement that accompany.“There is // territory and then / there is territory.” he writes, deep into thetitle poem. “Map is our / territory in one / case but may // not be hung //dependably upon in / the next. Whenever / you are mappable / you are immigrant./ The world hostile. // Tread with care.” Across his shorter lyrics, oneparticular highlight is the sequence “TWENTY-FIVE FOR LEW WELCH,” providingconversation with the work and the figure of the late American poet Lew Welch (1928-1971),stepfather to musician Huey Lewis (who picked his stage name in memoriam); the BeatGeneration poet who wandered into the woods of Nevada County and was never seenagain. As Dunagan writes:

Patrick James Dunagan’s latest collection

City Bird and Other Poems

(SanFrancisco CA: City Lights Books, 2024), reveals him as the most San Franciscoof contemporary poets, riffing off a rich history of current and historic SanFrancisco poets, artists and landmarks including Bill Berkson, Lew Welch, JoanneKyger, Sunnylyn Thibodeaux, Joan Brown, Jay DeFeo, O’Farrell Street and St.Anne of the Sunset. “One whispering tales of woe to another / cow as heavenlygargoyle / spring dazzler in mystic’s ear,” he writes, to open the poem “ST.ANNE OF THE SUNSET,” a poem for the century-plus rosy-red Catholic Church inSan Francisco’s Sunset District (an area originally known as the “Outside Lands”),near Golden Gate Park. There is such a sense of wonder through Dunagan’s lyrics,offering first-person laid-back declarations on and around history, awarenessand magic, articulating the ordinary dailyness of existing within such a spaceand place, and the layerings of contemporary and historic movement that accompany.“There is // territory and then / there is territory.” he writes, deep into thetitle poem. “Map is our / territory in one / case but may // not be hung //dependably upon in / the next. Whenever / you are mappable / you are immigrant./ The world hostile. // Tread with care.” Across his shorter lyrics, oneparticular highlight is the sequence “TWENTY-FIVE FOR LEW WELCH,” providingconversation with the work and the figure of the late American poet Lew Welch (1928-1971),stepfather to musician Huey Lewis (who picked his stage name in memoriam); the BeatGeneration poet who wandered into the woods of Nevada County and was never seenagain. As Dunagan writes:As a young man Welch wasamong the earliest, as well as by far the most readable and enlightening, ofGertrude Stein scholars.

* * *

There was a riot down offMarket St. in San Francisco. Welch went to check it out with Ted Berrigan andAlice Notley. Outside a bar they nearly tripped over Philip Whelan who wasdrying out his feet, resting them on the unusually sun-warmed pavement. “Hi,Phil,” said Notley stooping down as Welch & Berrigan went inside the bar eachfor a piss and beer.

* * *

In his interview with DavidMeltzer, Welch identifies Charles Parker and Jack Spicer as the two men mosthellbent on self-destruction he’d ever witnessed.

* * *

Followinghis prior collections There Are People Who Say That Painters Shouldn’t Talk:A Gustonbook (Post-Apollo Press, 2011), Das Gedichtete (Ugly DucklingPresse, 20130, from Book of Kings (Bird and Beckett, 2015), Drops of Rain / Drops of Wine (Spuyten Duyvil, 2016), Sketch of the Artist (FMSBW,2018) and After the Banished (Empty Bowl, 2022), as well as a volume of criticism,The Duncan Era (Spuyten Duyvil, 2016), the first half of City Bird andOther Poems holds the title poem, the extended lyric “City Bird,” a swirlinginvocation and a casual, carved patter of complex layerings. “Sounding off on /any or every / possible hushed,” he writes, as part of the first page, “occluded/ effort. Channeling his / thoughts, advancing upon // the world passing //round in her / song.” It would be impossible to not get caught up in the lyric sweep,and sway, of pendulous rhythm. If there are poems that swing with swagger,Dunagan’s poems provide the exact opposite, leaning his purposeful, thoughtfulmeandering down the scope of each page. “Every // ounce of material // assertsif factual.” he writes, as part of the title poem. “Like a cop / exploringspaced out / hippie shit, folds / of time prove // intricate.”

August 30, 2024

12 or 20 (second series) questions for Danielle Devereaux

Danielle Devereaux's

[photo credit: Leona Rockwood] poetry collection

The Chrome Chair

was published in April 2024 by Riddlefence Debuts. Her chapbook,

Cardiogram

, was published by Baseline Press (2011). Quelle Affaire, a poem in the chapbook, has been turned into a short film by filmmaker Ruth Lawrence. Danielle's poetry has appeared in Riddle Fence, Arc Poetry Magazine, The Fiddlehead, Newfoundland Quarterly and The Best Canadian Poetry in English 2011. She lives in St. John's NL, with her partner, two cats, and two kids, the eldest of which is currently petitioning hard for a blue-tongued skink; as of July 2024 no skink has been added to the household.

Danielle Devereaux's

[photo credit: Leona Rockwood] poetry collection

The Chrome Chair

was published in April 2024 by Riddlefence Debuts. Her chapbook,

Cardiogram

, was published by Baseline Press (2011). Quelle Affaire, a poem in the chapbook, has been turned into a short film by filmmaker Ruth Lawrence. Danielle's poetry has appeared in Riddle Fence, Arc Poetry Magazine, The Fiddlehead, Newfoundland Quarterly and The Best Canadian Poetry in English 2011. She lives in St. John's NL, with her partner, two cats, and two kids, the eldest of which is currently petitioning hard for a blue-tongued skink; as of July 2024 no skink has been added to the household.1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Cardiogram, my first chapbook, was published by Baseline Press in 2011 as part of Baseline's inaugural press run. The Chrome Chair, my first full-length collection, was published with Riddlefence as part of its inaugural run as a book publishing imprint, which is kind of a funny coincidence. How did the first publication change my life? I guess it put me out in the world as a poet in a way that I'd not been very public about prior to that. In some ways it feels like publishing The Chrome Chair will have a similar effect. With Cardiogram there were a couple of launches in Ontario, where Baseline Press is based, and I was invited to read at a couple of festivals in Newfoundland and all of that was quite fun and exciting, and then I got very quiet with my writing again. 2011 was quite a while ago (!) so it feels like publishing The Chrome Chair will put me out in the world as a poet again, and perhaps more so since it's a full-length collection this time. Hopefully, it will be well-received and I'll have the opportunity to do some readings with the full collection in hand.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I did a creative writing poetry course as part of my BA in English (a million years ago), just to try something different. It was the first time I participated in a workshop style class and honestly, it was just a lot of fun. The course was taught by Marilyn Bowering; I'm pretty sure she was at Memorial University as writer-in-residence at the time. The difference between the poems I submitted to get into the course and the poems that I was writing at the end of it was pretty big -- a very steep learning curve! With poetry, as with all writing I guess, but particularly with poetry, it's a bit like playing with building blocks, but the blocks are words. Maybe that feels more apparent in poetry because the physical form of the poem is also a part of it (e.g. 4 stanzas of 4 lines or whatever) and I guess I like that piece of it. There's something kind of tidy about setting down words in the form of a poem, even if the words in the poem might take you all over the place. Not that I'm a tidy person, quite the opposite, unfortunately, but there's something satisfying about applying order to a mess of words. Also, the first book of poetry I remember reading is Roald Dahls' Dirty Beasts, which is quite funny and dark and kind of wacky, as is a lot of his work. I know Dahl is a problematic figure for a variety of reasons, but I think reading that particular book of his as a kid gave me the freedom to see poetry as a way to have fun with words, even when you're trying to get at or understand something serious or dark. Short answer: writing poems is fun.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It takes a while for me to start any particular project (writing projects and other types of projects too). I procrastinate. Usually too much. As for the drafts, there have been times when a poem has arrived quickly, percolating in my head for a day or two and arriving on the page quite close to its final shape, and times when the first draft is such a mess I feel like I can't string two words together, let alone write a poem.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

This particular manuscript started as a pile of poems, and I don't think I spent too much time wondering what was going to become of them in the end. The second half of The Chrome Chair does have a theme -- the life and work of Rachel Carson -- so I was thinking of that as a series of poems. I began the Rachel Carson poems in a creative writing poetry class that I did with Mary Dalton (I was hooked on Memorial University's creative writing classes for a time). In that class Mary had us write and craft our own chapbooks, which was a really lovely, hands-on creative process. I'm not sure if everyone's chapbook had a theme, but I wanted a theme for my chapbook and I had written a couple of Rachel Carson poems, so I decided to try to write more.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I love going to readings. Hearing other people read often makes me want to go home and write. As for doing readings myself, I enjoy it, but it also makes me extremely nervous. Like I can't eat properly for a couple of days before the reading and then when I get to the venue my stomach feels like it might fall out on the floor kind of nervous. I have to prepare and practice what I'm going to say or else I'll either babble on forever or draw a complete blank. But at the same time, it is fun to read my work out loud and witness people's reactions to it, and if the reading goes well and people connect with the work, that connection feels great. It's too bad about my nerves being shot and my wreck of a gut though.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I guess it depends on the project. I don't think I necessarily start out with any theoretical concerns or questions, or not any that I can identify from the get-go. For this particular book I think there are some questions but I'm not sure if I'm answering or asking them, maybe a bit of both. I guess some of these questions would be: what role does gender play in the ways we experience the world? Who gets to become a pop culture icon and who does not? What difference does place, gender, time make? Something about cultural identity narratives...But I don't think I really sat down with the intention of asking or answering any of those questions in the poems, they just happen to be questions that interest me and so they show up in my writing. The current questions? I'm not sure I can even go there. So much about our current world is sad and horrible, maybe it always has been, but these days we can see all that horror and sadness on all our screens in real time every second of the day... I don't know -- how to still see the beauty (because there is still much beauty too), celebrate the beauty without denying the sadness and horror? How to hang on to hope?

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I think writing, or perhaps more specifically the written word, whether that be poetry or fiction or nonfiction, does have the ability to spark connections. When you read a work and it makes you feel something, makes the gears in your brain spin or your heart jump, that's a connection, an "ah yes, I am more than a cog in the wheel of the capitalist patriarchy" kind of moment. I do think these types of connections are important. And pretty wild when you think about the fact that they can take place across time, culture, race, gender, etc. I don't think it's only writing that does that, lots of art forms do, but maybe that's the role of the writer -- to spark connections, or one of the roles anyway.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I love working with an editor! Having another set of eyes on work that my eyes can hardly bear to look at anymore is definitely essential.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

You know how people say if something is worth doing, it's worth doing right? Well, I found the following rebuttal helpful in the face of trying to actually finish and let go of this manuscript: if something is worth doing, it's worth doing to the best of your ability at this particular juncture, in the time you have available to you right now. It's never going to be perfect -- the conditions under which you're writing, nor the manuscript, but that doesn't mean you shouldn't do it. Maybe if I'd done more courses, if I'd read more books, if I'd waited for a variety of circumstances to be different, this book would be better, but that could've gone on forever, and none of us get forever.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I don't have a writing routine, which I tend to see as one of my personal flaws. I've never been very good at prioritizing my writing and now that I have two little kids it's pretty easy to let their care and happiness (and my bill-paying day job) take priority. I've been lucky enough to do a couple of stints at the Banff Writing Studio (pre-kiddos), which was amazing and super productive. But my life isn't really set up to spend the majority of my days writing in a hotel room while someone else does all the cooking and makes my bed while I'm out hiking! At present I don't actually have a room of my own to write in, I'm hoping some simple home renos will fix that sooner rather than later and then maybe I'll sort out some semblance of a routine? A gal can dream anyway.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

If I'm not writing at all, binge-reading, like just reading and reading and reading, usually makes me want to write. Sometimes I re-read books that I know I love, sometimes I go looking for something new. If I am writing, but the writing is stuck and just feels bad, going for a long walk alone often helps.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Blasty boughs, lilacs, wild roses and toast (but not all at once).

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Conversations, or more specifically the turns of phrase people use in conversation, pop culture and the news (when I can stomach it) have all had an influence on my work up to this point.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Mary Dalton has been very important to my work as a mentor, friend and poet. I love Karen Solie's poetry and Sue Goyette's work; there are so many poets in Canada to admire! I like reading Irish writers too -- Anne Enright, Elaine Feeney, Louise Kennedy. In terms of The Chrome Chair, Stephanie Bolster's collection White Stone: The Alice Poems , which is about Alice Liddle of Alice in Wonderland fame, was definitely part of my inspiration to write Rachel Carson poems. Originally I thought I'd do a whole book of Rachel Carson poems; Bolster's collection is a whole book of Alice poems, but that's not what happened. The Chrome Chair is divided into two sections and the second second section focuses on Carson. Figuring out how to combine the Rachel Carson poems with the non-Rachel Carson poems was a challenge, but my editor, Sandra Ridley was really helpful with that (Sandra is awesome).

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I'd love to go to Iceland. Iceland is sometimes spoken about here as the kind of country Newfoundland could've been if we'd become independent instead of joining Canada. I'm not sure if that's true, but I'd still love to see it for myself.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I sometimes wish I'd done something more practical and/or helpful, like medicine or nursing: "Here, let me reset that bone/stitch up that wound for you!" Those would be good skills to have. But I don't know if I'd have been good at any of that. I thought I wanted to be an academic for a while, I started but did not complete a PhD in communication studies. Quitting the PhD was a difficult decision, but I don't regret it. Narrating audio books seems like it'd be a good gig. It'd be fun to give that a try.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

I don't think I ever really set out to be a writer, or anything else in particular. I've never been very good at long term planning or goal-setting, it's been more of a "let's try this and see what happens" approach to things, so I'm lucky and I feel grateful that it's worked out that I get to do this, to publish a book of poems.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I'll give you two books because I mostly watch kids movies these days and I'm not sure Paddington 2 is really what you're looking for (though I honestly cannot wait for Paddington 3 to come out). The End of the World is a Cul-de-Sac -- isn't that an awesome title? -- a short story collection by the Irish writer Louise Kennedy. It's one of those books that's so good it hurts. And I just finished Vigil , a collection of linked short stories by local writer Susie Taylor, which I read all in one gulp. Also heart-breakingly good and set in contemporary outport Newfoundland.

19- What are you currently working on?

After I signed off on the absolute final, no more changes could possibly be made, page proofs of The Chrome Chair I felt wrung out, like I'd never write another word. I'd been working on the manuscript that became The Chrome Chair off and on for about 17 years and I thought I'd be nothing but relieved to be done with it, and I am happy with how it turned out, but also it feels a bit weird, lonely even, not to have a bunch of poems hanging over my head, so maybe that means I need to find a new writing project. TBD.

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

August 29, 2024

Samuel Ace, I want to start by saying

I want to start by sayingI hear the filter in the turtle tank like a fountain.

I want to start by sayinglike a fountain in the middle of a field of wildflowers.

I want to start by sayingthat today would have been my father’s 84th birthday,

that he died eighteen days before his 79th.

I want to start by sayingthat he was young and that death took him by surprise.

I want to start by sayingthat my mother died nine months ago, less than four

and a half years after my father.

I want to start by sayingthe beginning of this sentence.

I want to start by sayingthat a child could have been born in that time.

I want to start by sayingthat a whole year has gone by since my godchild’s birth.

Andso begins the accumulative book-length poem by American poet Samuel Ace, thedeeply intimate

I want to start by saying

(Cleveland ON: Cleveland StateUniversity Poetry Center, 2024), a work composed from a central, repeatingprompt. The structure is reminiscent of the echoes the late Noah Eli Gordonproffered, composing book-length suites of lyrics, each poem of which sharedthe same title—specifically

Is That the Sound of a Piano Coming from Several Houses Down?

(New York NY: Solid Objects, 2018) [see my review of such here] and

The Source

(New York NY: Futurepoem Books, 2011) [see my review of such here]—or, perhaps a better example, the late Saskatchewan poet John Newlove’s poem “Ride Off Any Horizon,” a poem that returned to that samecentral, repeated mantra (one he originally composed with the idea of removing,aiming to utilize as prompt-only, but then couldn’t remove once the poem was fleshedout). “I want to start by saying,” Ace writes, line after line after line,allowing that anchor to hold whatever swirling directions or digressions the textmight offer, working through the effects that history, prejudice and grief hason the body and the heart. I want to start by saying articulates past racialviolence in Cleveland, subdivisions, loss, “trans and queer geographics offamily and home,” chronic illness, love and parenting, stretched across onehundred and fifty pages and into the hundreds of accumulated direct statements.Amid a particular poignant cluster, he writes: “I want to start by saying that Iaccepted the conditions of my father’s love.” There is something of thecatch-all to Ace’s subject matter, the perpetually-begun allowing the narrativesto move in near-infinite directions. As it is, the poem loops, layers andreturns, offering narratives that are complicated, as is often the way offamily, writing of love and of fear and of a grief that never truly goes away. Further,on his father: “I want to start by saying I was frightened to upset the balanceof our connection.”

Andso begins the accumulative book-length poem by American poet Samuel Ace, thedeeply intimate

I want to start by saying

(Cleveland ON: Cleveland StateUniversity Poetry Center, 2024), a work composed from a central, repeatingprompt. The structure is reminiscent of the echoes the late Noah Eli Gordonproffered, composing book-length suites of lyrics, each poem of which sharedthe same title—specifically

Is That the Sound of a Piano Coming from Several Houses Down?

(New York NY: Solid Objects, 2018) [see my review of such here] and

The Source

(New York NY: Futurepoem Books, 2011) [see my review of such here]—or, perhaps a better example, the late Saskatchewan poet John Newlove’s poem “Ride Off Any Horizon,” a poem that returned to that samecentral, repeated mantra (one he originally composed with the idea of removing,aiming to utilize as prompt-only, but then couldn’t remove once the poem was fleshedout). “I want to start by saying,” Ace writes, line after line after line,allowing that anchor to hold whatever swirling directions or digressions the textmight offer, working through the effects that history, prejudice and grief hason the body and the heart. I want to start by saying articulates past racialviolence in Cleveland, subdivisions, loss, “trans and queer geographics offamily and home,” chronic illness, love and parenting, stretched across onehundred and fifty pages and into the hundreds of accumulated direct statements.Amid a particular poignant cluster, he writes: “I want to start by saying that Iaccepted the conditions of my father’s love.” There is something of thecatch-all to Ace’s subject matter, the perpetually-begun allowing the narrativesto move in near-infinite directions. As it is, the poem loops, layers andreturns, offering narratives that are complicated, as is often the way offamily, writing of love and of fear and of a grief that never truly goes away. Further,on his father: “I want to start by saying I was frightened to upset the balanceof our connection.”I want to start by saying that I’vebeen out of the house twice today.

I want to start by saying that now Iam sitting with a friend over coffee.

She mourns the loss offriends because she’s in love with someone who is trans.

I want to start by saying thefamiliarity of so many stories.

I want to start by saying that I mournthe rise of rivers, the smell of creosote,

the relief of summer monsoons.

Andyet, through Ace’s perpetual sequence of beginnings, one might even comparethis book-length poem to the late Alberta poet Robert Kroetsch’s conversationsof the delay, delay, delay: his tantric approach to the long poem, always backto that central point; simultaneously moving perpetually outward and back tothe beginning. “I want to start by saying the deep orange skies of the monsoon.”he writes, mid-way through the collection. “I want to start by saying we havereturned to Tucson.” Set into an ongoingness, the lines and poems of Samuel Ace’sI want to start by saying is structured into clusters, allowing thebook-length suite a rhythm that doesn’t overwhelm, but unfolds, one self-containedcluster at a time. His lines and layerings are deeply intimate, setting down adeeply felt moment of grace and contemplation. The book moves through thestrands and layers of daily journal, writing of daily activity and thoughts aswell as where he emerged; how those moments helped define his choices through theability to reject small-mindeded prejudices. Through the threads of I wantto start by saying, Samuel Ace may be articulating where he emerged, butall that he is not; all he has gained, has garnered, and all he has leftbehind. As he writes, early on:

I want to start by sayingperfect in what world.

I want to start by sayingdesire.