Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 94

April 19, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jon Riccio

Jon Riccio is the author of Agoreography and thechapbooks Prodigal Cocktail Umbrella and Eye, Romanov. He servesas the poetry editor at Fairy Tale Review.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does yourmost recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Thank you, rob, for giving me the opportunity to discuss mywork. Also, for your stewardship of, literally, hundreds of writers. Happy 30thanniversary to above/ground press! Rachel Mindell’s rib and instep: honeyis how I became acquainted with the ways, large and small, in which “you’re[poetry’s] one in seven billion.”

My first book was the culmination of poems written over aseven-year period tied to my MFA and PhD degrees. Agoreography changedmy life in that I now have a ‘spokescollection’ for a poetry movement Ienvision, The Confurreal or Confessional Surrealism. Picture Anne Sexton,Robert Lowell, WD Snodgrass, and Sylvia Plath on a 1920s airship gabbing withJames Tate, Dean Young, Joyelle McSweeney, and Aimé Césaire. Whatevergerminates cerebrally and tonally in those quarters jumps to the present day.Vulnerability’s Petri-dish think tank, by any other.

My most recent work’s leaning more towards Surrealism than Confessional,with a peppering-in of where science fiction and occult speculation were about twenty-fiveyears prior. Infomercials, spacecrafts, little stargates that could.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say,fiction or non-fiction?

I tried fiction. And I tried fiction again. Poetry’s a betterswim. Two books I bought, circa 2011/12ish, when they gave readings atKalamazoo Valley Community College, were Kay Ryan’s Elephant Rocks and PatriciaClark’s North of Wondering. Spending time with their poems after a threeyear-ish hiatus from reading any poetry was a way of quieting my brain,which at that point was immersed in all things OCD with frequent stops inagoraphobia. In August 2012, I joined a writing workshop mentored by John Rybicki. That September, I joined another, led by Traci Brimhall. Both gaveselflessly of themselves to the point where I felt ready to send my MFAapplication portfolio to six schools. The rest is University of Arizonahistory.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writingproject? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Dofirst drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work comeout of copious notes?

The snails come to me for advice on how to slow things down.Glaciers have better responses to starter pistols. My first drafts areoverwritten, then pared anywhere from weeks to months before I consider a draftin submittable shape. In between, I have a quartet of readers who see the workat its newest. We encourage, we trade. Then, it goes to an online critique group.We trade, we encourage, we fawn over each other’s pets.

I love your question about copious notes. I had, at onepoint, a red notebook called Operation: Island, filled with lines frompoems that were beyond stalled. Many a revision benefitted from those Islandplug-ins. I should write an essay on the difference between rummage andsalvage. Vetted by mollusk.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you anauthor of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are youworking on a "book" from the very beginning?

Lately, my poems are coming from a two-month generativeproject I’ve described as The Cantos meets I Remember. I’m justnow revisiting the work with the intention of “what can I harvest?” Poemlengths vary: my chapbooks Prodigal Cocktail Umbrella and Eye,Romanov contained pieces on the shorter side. Agoreography haslonger work. Rare is the current poem where I go over a page.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creativeprocess? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I LOVE giving readings, in-person or Zoom, because theyremind me of the recitals I gave as a violist. You read your poems, see what fliesand what doesn’t (even though you thought it would in the revisions leading upto said reading). On the flipside, I LOVE organizing readings, whether duringschool days or now, in my work with the literary organization 1-Week Critique.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing?What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do youeven think the current questions are?

I think about staying true (and nuancing) to my aestheticwithout completely alienating readers. I traffic in density and allusions noteveryone gets if they haven’t sponged pop culture (mainstream to obscure, peakwindow 1977 - 2000). The denser, allusion-heavier my poem, the more I’m apt toput it in couplets, which assist rather than mire. I’m worried about influence:do I innovate or mimic? That’s when I’m reminded of a phrase I hear at leastonce a month, “Nothing happens in a vacuum.” This calms me.

Currently asking myself: How, to paraphrase Lucie Brock-Broido, do I cultivate the patience of a taxidermist? Patience is myAchilles, yet I am at a point where patience is a life preserver in a sea ofsea changes, but gosh, is it slippery.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being inlarger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writershould be?

I’m interested in the linkages between poetry and thepedagogy I pass along to my students. Since June of 2021, I’ve been workingwith graduate-level writers at the University of West Alabama. I also teachcomposition and literature, so I look at reverse-engineering aspects (PoemProcess: what have you taught me and how can I channel it outwards?) We neverknow who is just one draft away from the decision to lead a life in letters (orrealizing the value of a life in letters). My eyes and ears are peeled, and ifthat’s my impact on larger culture, I’m fulfilled.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editordifficult or essential (or both)?

Three times where an outside editor has revolutionized myapproach to poetry: A) Dr. Charles Sumner, who served on my dissertationcommittee (so, a reader, but . . .), asked me seven or eight questions thattook my critical introduction from idea-spouting to The Confurreal’s inception.B) Dr. Jaydn DeWald, who as the editor at COMP: an interdisciplinary journal,had a similar method of question-oriented feedback, which helped me turn myrevised introduction of The Confurreal into a manifesto on The Confurreal,published as “The Florist’s Crossroads.” C) Andrea Watson, the founder of 3: A Taos Press and publisher of Agoreography, whose (wait, wait, let meguess) editorial line of questioning took the collection from what it was tothe book it became. Again, “Nothing happens in a vacuum.”

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (notnecessarily given to you directly)?

From Paul Tran’s “The Cave,” which appears in All theFlowers Kneeling (2022): “Keep going, the idea said.”

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or doyou even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I keep a log that records how many minutes I write each day.I aim for fifteen to a half hour, sometimes more. The day begins with either anhour of grading or reading. Before that, about fifteen minutes of personaljournaling.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn orreturn for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Back-cover bios; past issues of Poets & Writers.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Meatballs frying in a spa of olive oil.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books,but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music,science or visual art?

Classical music//soundtracks: Sibelius Violin Concerto ind minor, Khachaturian Violin Concerto in d minor, Tchaikovsky ViolinConcerto in D Major, Prokofiev Violin Concerto No. 2 in g minor,Prokofiev Violin Sonata No. 1 in f minor, Vieuxtemps Violin ConcertoNo. 4 in d minor, Paganini Violin Concerto No. 1 in D Major,Wieniawski Violin Concerto No. 1 in f-sharp minor, Franck SymphonicVariations, Sibelius Symphony No. 1 in e minor, Symphony No. 2 inD Major, Ravel Piano Concerto in G Major// Psycho, HalloweenII, Halloween III, The Fog, Salem’s Lot, The StarWars Trilogy, Blade Runner, Alien.

Nature: Walks that last anywhere from one hour to eightyminutes.

Science: Any and all questions related to time travel andUFOs.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for yourwork, or simply your life outside of your work?

Anne Sexton, everything she wrote, including the play Mercy Street; pedagogically, Graywolf’s The Art of Series has made all thedifference in how I approach classroom discussions about creative writing (DeanYoung’s The Art of Recklessness, Donald Revell’s The Art of Attention,Carl Phillips’s The Art of Daring); recent collections by Sandra Simonds, M Soledad Caballero, Jayme Ringleb, Tom Holmes, Bob Carr, Jessica Guzman, Charles Kell, Jaydn DeWald, Jonathan Minton; my Unexplained Mysteriescalendar.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Edit, distribute, and steward an anthology of writers whosework falls under the umbrella of The Confurreal. I have my solicitation listbut lack the funding to make it a reality.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, whatwould it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doinghad you not been a writer?

In no particular order, I would attempt: literary agent,manuscript editor, paranormal bookstore owner, Ufologist, craft servicescaterer (infomercials, television production sets). In my twenties, I had atwo-day interest in meteorology, then a few weeks where dairy farming wasentertained. Parallel universe Jon, he’s a concert violinist or world-renownedmathematician.

If not for writing, I would have stayed at my data-entry jobin a Michigan food bank.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

In my best poetry self-excerpting voice: “I'm a writerbecause I ran out of zip codes to be fired in.” (“Parenting Wil Wheaton”).

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the lastgreat film?

DaMaris B. Hill’s 2019 poetry/prose collection, A Bound Woman Is A Dangerous Thing: The Incarceration of African American Women from Harriet Tubman to Sandra Bland. Cinema-wise, The Whale.

19 - What are you currently working on?

My stove burners are kettling student papers for a mythologyclass, essay drafts, submission screening at Fairy Tale Review,free-writing projects, and reaching out to poets for permission to write abouttheir work in my monthly craft articles at 1-Week Critique.

Thank you again, rob.

April 18, 2023

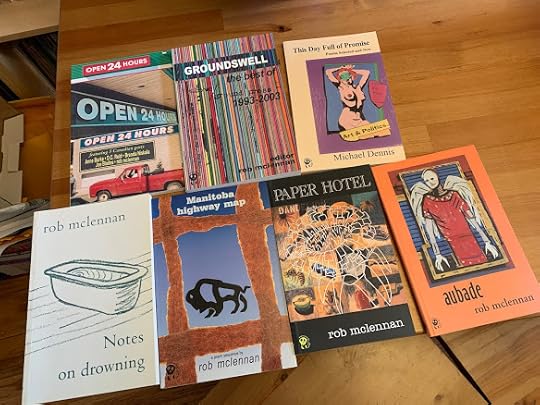

sale : rob's Broken Jaw Press titles,

I recently garnered a few mounds of books from Broken Jaw Press (see my obit for editor/publisher Joe Blades here), including a handful of my own early titles that Joe published, as well as a couple of other titles I was involved with as editor. If anyone is interested, I am offering copies for sale.

I recently garnered a few mounds of books from Broken Jaw Press (see my obit for editor/publisher Joe Blades here), including a handful of my own early titles that Joe published, as well as a couple of other titles I was involved with as editor. If anyone is interested, I am offering copies for sale.Notes on drowning (1998; my full-length debut!), paper hotel (2002) and aubade (2006) I'm offering for $7 each; Manitoba highway map (1999; my third trade collection) and the five poet anthology Open 24 Hours (1998; poems by myself, Brenda Niskala, Joe Blades, D.C. Reid and Anne Burke) for $5 each.

this day full of promise: new & selected poems by michael dennis (2002) that I edited and put through the cauldron books series that Broken Jaw published I can offer for $7 each as well. I'm very pleased to have a new stack of copies of GROUNDSWELL: best of above/ground press, 1993-2003 (2003), the anthology celebrating the first decade of the press, especially since this year is not only the thirtieth anniversary of the press, but Invisible Publishing is scheduled to produce the third 'best of' decade anthology this fall. I can offer copies of GROUNDSWELL for $15 each (it even includes a bibliography of the first ten years of the press!), although if you order 2 or more books, I'm willing to throw in a copy of Manitoba highway map gratis.

if interested, send funds via email or paypal to rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com; if you are ordering a single book add $2 for Canadian orders, and $5 for orders to the United States : if you are ordering two or more books, add $5 for postage for Canadian orders, and $11 for the United States. for any orders beyond the boundaries of North America, send me an email and I can always attempt to figure out postage. I can even sign copies, if that is of interest. also, be sure to email if you have any questions.

Oh, and don't forget that I still have copies of the book of smaller (University of Calgary Press, 2022) and essays in the face of uncertainties (Mansfield Press, 2022) as well, yes? See the link here for information on those. And I've the final copies of my two novels with Mercury Press--white (2007) and missing persons (2009)--still available for $15 each. What a deal!

April 17, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Karen Enns

Karen Enns is the author of four books of poetry: Dislocations, Cloud Physics, winner of the Raymond Souster Award, Ordinary Hours, and That Other Beauty. She lives in Victoria, BritishColumbia.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does yourmost recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book marked a commitment to poetry, to writing, thatwas already there, so it didn’t change my life in that sense, but having thepoems in print did make the commitment public, which adds a slightly differentperspective.

My most recent work reflects some of the same preoccupationsas the earlier poems but the structures are more variable. The pressure on theline has definitely changed over time and I’m more comfortable working with longerpoems.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say,fiction or non-fiction?

I wrote poems when I was very young and then turned to musicfor a long time, but I was always drawn to the form, the condensation—whenreading, the possibility of being transported in just a few lines. Poetry’sobvious musical component was definitely an inducement.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writingproject? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Dofirst drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work comeout of copious notes?

First drafts of poems often visually resemble their finalshape, in the sense that they already have a length of line and a rhythmic pitch,so to speak, but they don’t usually “appear” in any kind of final form. Theprocess is often slow, a chiselling away, but that working out of the lines andarcs, the modulations, is absorbing. It reminds me of learning a piece ofmusic.

I don’t usually make notes, but I’ve probably lost some goodideas along the way because of this.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you anauthor of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are youworking on a "book" from the very beginning?

I work on a poem, or sometimes several poems at once, withoutany sense of a longer book form. Much later, when I have a collection of files,I slowly begin to see the possibilities of a larger structure. It’s a bit likestanding on a dock watching for a boat to appear out of the fog.

A poem can begin in many ways, but there has to be arecognizable moment for me, a slipping into a different mode of seeing orhearing, with an emotional charge, that generates the impulse of the poem.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creativeprocess? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I write in solitude, so readings are not part of thecreative process itself, but they’re part of a broader cultural conversation ina public sphere, like concerts, plays, films, art exhibits, that is essential forartistic exchange. Everyone benefits from that dialogue. Having said all that,I do get nervous for readings.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind yourwriting? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? Whatdo you even think the current questions are?

I’m not conscious of trying to answer questions with my work.The searching is probably more crucial, not only for creative reasons, butalso—I like to think—because whatever the current questions may be, a sense ofopen-endedness can be transcending.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being inlarger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writershould be?

Absolutely, the writer has a role. I don’t know that it haschanged that much through history, although each era has its own particularchallenges. But writers often observe from the outskirts. They create a pause,a space, in which it’s possible to imagine other ways of seeing and thinking,other worlds.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outsideeditor difficult or essential (or both)?

It’s challenging to think hard about inconsistencies orweaknesses in your own work, or to question patterns you rely on, but theprocess is essential and broadening. And there is the possibility of developinga literary friendship with someone whose editorial work you trust and respect.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (notnecessarily given to you directly)?

Some of the best advice appears in verse itself.Zagajewski’s “Try to praise the mutilated world” comes to mind.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or doyou even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I write in the morning before the day’s distractions pileup.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn orreturn for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Most of the time, it’s simply a matter of choosing whetherto push through or be patient while things settle, but bike rides and hikes arehelpful. I’m very fortunate to live near forests and coastlines.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

If I moved away from the west coast, I’m sure it would bethe scent of cedar when it rains, but to be back in Niagara again, on the farm,in a second, it’s the smell of turned-up soil in spring.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books,but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music,science or visual art?

I’d say all of the above have influenced my work at varioustimes.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for yourwork, or simply your life outside of your work?

The writing community in and around Victoria is a strong,lively one, which has been important. Farther afield, the work of writers andthinkers responding to political crisis, violence, displacement, are animportant resource for thinking about the future, as well as looking back to myown family/cultural history.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Become fluent in German, my first language; learn Chopin’s Bminor Sonata; visit Ireland. The list is long.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, whatwould it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doinghad you not been a writer?

I worked as a classical pianist for a number of years, andstill teach, so I’ve had the opportunity to follow a path other than writing.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing somethingelse?

A love of reading.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was thelast great film?

I recently read Walk the Blue Fields and SmallThings Like These by Claire Keegan, as well as a wonderful collection ofstories, Motley Stones, by Adalbert Stifter.

19 - What are you currently working on?

Short fiction.

April 16, 2023

today is Lady Aoife's seventh birthday,

April 15, 2023

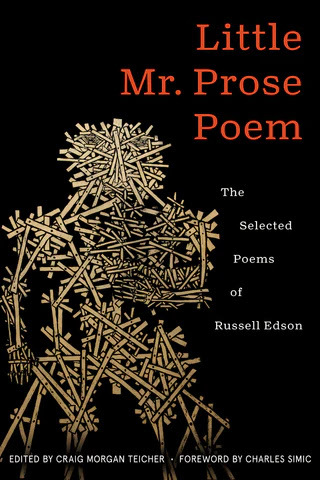

Little Mr. Prose Poem: Selected Poems of Russell Edson, ed. Craig Morgan Teicher

Edson was one of thedefinitive practitioners of the contemporary American prose poem. Charles Simic,in his beautiful Foreword, says that no one has yet offered a convincingdefinition of prose poetry. Nonetheless, permit me to make an attempt. Is aprose poem just a poem with no line breaks? If so, what can prose sentences andparagraphs do for a poem that lines can’t? What is prose and what is poetry,and what are the supposed differences between them? The poet, critic, andtranslator Richard Howard, who was my graduate school mentor and friend, has awonderfully useful and precise maxim for describing the difference between poetryand prose: “verse reverses, prose proceeds.”

This concise and musicalphrase summarizes what I believe to be one of the central truths about thenature of these two forms of writing: though made of the same basic stuff—letters,words, punctuation—once they take their shapes, they are actually differentsubstances, like water and oil (though they do mix), or, perhaps, more likewater and wood. They are composed of the same elements, but those elements aredeployed so differently that the results can seem like distant cousins at best.

But what are they? First,we need a definition of “prose”: it’s the word on the street; the writingpeople talk in; the words on signs; and the stuff, beside images, that the Internetis made of. In itself, it’s not scary (though lots of it piled up, say, in abig, fat book, might be). Reading prose, you might not even realize you’rereading it. (“‘No, And’: Russell Edson’s Poetry of Contradiction,” Craig MorganTeicher)

Yearsago I read an essay by American poet Sarah Manguso on the prose poems of Connecticut poet Russell Edson (1935-2014); despite usually believing and following whateverManguso might say about anything, I was never convinced by the work of Russell Edson, said to be the father of the American prose poem. I even picked up acopy of his prior selected a few years back, The Tunnel: Selected Poems of Russell Edson (Oberlin College Press, 1994), but couldn’t figure my way. I couldn’thear music in his poems, feeling them closer to incomplete short stories thanto the electric possibilities of the prose poem, especially against poets suchas Rosmarie Waldrop, Lisa Jarnot, Lisa Robertson, Robert Kroetsch, Anne Carsonand others. How was Edson’s work so praised?

Yearsago I read an essay by American poet Sarah Manguso on the prose poems of Connecticut poet Russell Edson (1935-2014); despite usually believing and following whateverManguso might say about anything, I was never convinced by the work of Russell Edson, said to be the father of the American prose poem. I even picked up acopy of his prior selected a few years back, The Tunnel: Selected Poems of Russell Edson (Oberlin College Press, 1994), but couldn’t figure my way. I couldn’thear music in his poems, feeling them closer to incomplete short stories thanto the electric possibilities of the prose poem, especially against poets suchas Rosmarie Waldrop, Lisa Jarnot, Lisa Robertson, Robert Kroetsch, Anne Carsonand others. How was Edson’s work so praised? Soof course, I was curious to see a copy of Little Mr. Prose Poem: Selected Poemsof Russell Edson, ed. Craig Morgan Teicher, with a Foreword by Charles Simic (Rochester NY: BOA Editions, 2023) land in my mailbox recently; perhapsthis collection might provide some sense of what it is I’d been missing, or atleast, not getting? Perhaps it is as simple as requiring the correct entrypoint in my reading. In my late twenties, after hearing from a variety of writersaround me on the brilliance of the work of Toronto poet David McFadden, thehalf-dozen titles I encountered weren’t providing me with any answers as to why,until I picked up a copy of his Governor General’s Award-shortlisted The Artof Darkness (McClelland and Stewart, 1984), a book that became my personalRosetta Stone for the since-late McFadden’s fifty years of publishing. With thatone title, all, including his brilliance, became abundantly and absolutely clear.

AsCharles Simic offers in his introduction: “Edson said that he wanted to write withoutdebt or obligation to any literary form or idea. What made him fond of prosepoetry, he claimed, is its awkwardness and its seeming lack of ambition. Themonster children of two incompatible strategies, the lyric and the narrative,they are playful and irreverent.” Little Mr. Prose Poem selects piecesfrom ten different collections produced during Edson’s life: The Very Thing ThatHappens (New Directions, 1964), What A Man Can See (The Jargon Society,1969), The Childhood of an Equestrian (Harper and Row, 1973), The ClamTheater (Wesleyan University Press, 1973), The Intuitive Journey (Harperand Row, 1976), The Reason Why the Closet Man Is Never Sad (WesleyanUniversity Press, 1977), The Wounded Breakfast (Wesleyan UniversityPress, 1985), The Tormented Mirror (University of Pittsburgh Press, 2001),The Rooster’s Wife (BOA Editions, 2005) and See Jack (Universityof Pittsburgh Press, 2009). Given the final collection on this particular listemerged five years prior to the author’s death, one is left to wonder if therewere uncollected pieces or even an unfinished manuscript left behind after hedied? Did all of his pieces fall within the boundaries of his published books?

Thereare ways that Edson’s odd narratives, populated with fragments and layerings ofscenes and characters, feel akin to musings, constructed as narrativeaccumulations across the structure of the prose poem. And yet, there are times Iwonder how these are “prose poems” instead of being called, perhaps, “postcardfictions” or “flash fictions.” It would appear that an important element of Edson’sform is the way the narrratives turn between sentences: his sentencesaccumulate, but don’t necessarily form a straight line. There are elements ofthe surreal, but Edson is no surrealist; instead, he seems a realist who blurs andlayers his statements up against the impossible. I might not be able to hear aparticular music through Edson’s lines, but there certainly is a patterning; alayering, of image and idea, of narrative overlay, offering moments of introspectionas the poems throughout the collection become larger, more complex. As well,Edson’s poems seem to favour the ellipses, offering multiple openings butoffering no straightforward conclusions, easy or otherwise. Not a surrealist,but a poet who offers occasional deflections of narrative. Even a deflection isan acknowledgment of the real, as a shape drawn around an absence. A deflection,or an array of characters who might not necessarily be properly payingattention, or speaking the truth of the story, as the poem “Baby Pianos,” from TheTormented Mirror, begins:

A piano had made a huge manure. Its handler hoped thelady of the house wouldn’t notice.

But the ladyof the house said, what is that huge darkness?

The piano justhad a baby, said the handler.

But I don’t seeany keys, said the lady of the house. They come later, like baby teeth, saidthe handler.

Meanwhile thepiano had dropped another huge manure.

AsCraig Morgan Teicher writes as part of his afterword that Edson is “obsessedwith miscommunication; it is his bedrock truth. People don’t listen to eachother, are generally intent on fulfilling their own needs, and willfullyignorant of the needs of those around them. His characters constantly argue andcontradict one another.” Moving through this collection, I can now see Edson’sinfluence in a variety of younger American poets, most overtly through Chicago poet Benjamin Niespodziany (who I do think is doing some great things), butalso through Evan Williams, Shane Kowalski, Zachary Schomburg, Leigh Chadwick and the late Noah Eli Gordon, as well asthrough Manguso herself, across those early poetry collections. In many ways,Niespodziany might even be the closest to an inheritor I’ve seen of Edson’swriting, although with the added element of a more overt surrealism viaCanadian poet Stuart Ross. And perhaps, through Little Mr. Prose Poem, Iam slowly beginning to understand what all the fuss has been about.

April 14, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Joy Castro

Joy Castro

is theaward-winning author of the 2023 historical novel

One Brilliant Flame

,set in the 19th-century Cuban anticolonial émigré community in Key West;

Flight Risk

, a finalist for a2022 International Thriller Award; the post-Katrina New Orleans literarythrillers

Hell or High Water

, which received the Nebraska BookAward, and Nearer Home, which have been published in France byGallimard’s historic Série Noire; the story collection

How Winter Began

;the memoir

The Truth Book

; and the essay collection

Island of Bones

, which received the International Latino Book Award. She is alsoeditor of the craft anthology

Family Trouble: Memoirists on the Hazardsand Rewards of Revealing Family

and the founding series editor ofMachete, a series in innovative literary nonfiction at The Ohio StateUniversity Press. Her work has appeared in venues including Ploughshares, TheBrooklyn Rail, Senses of Cinema, Salon, GulfCoast, Brevity, Afro-Hispanic Review, SenecaReview, Los Angeles Review of Books, and The New YorkTimes Magazine. A former Writer-in-Residence at Vanderbilt University, sheis currently the Willa Cather Professor of English and Ethnic Studies (LatinxStudies) at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, where she directs theInstitute for Ethnic Studies.

Joy Castro

is theaward-winning author of the 2023 historical novel

One Brilliant Flame

,set in the 19th-century Cuban anticolonial émigré community in Key West;

Flight Risk

, a finalist for a2022 International Thriller Award; the post-Katrina New Orleans literarythrillers

Hell or High Water

, which received the Nebraska BookAward, and Nearer Home, which have been published in France byGallimard’s historic Série Noire; the story collection

How Winter Began

;the memoir

The Truth Book

; and the essay collection

Island of Bones

, which received the International Latino Book Award. She is alsoeditor of the craft anthology

Family Trouble: Memoirists on the Hazardsand Rewards of Revealing Family

and the founding series editor ofMachete, a series in innovative literary nonfiction at The Ohio StateUniversity Press. Her work has appeared in venues including Ploughshares, TheBrooklyn Rail, Senses of Cinema, Salon, GulfCoast, Brevity, Afro-Hispanic Review, SenecaReview, Los Angeles Review of Books, and The New YorkTimes Magazine. A former Writer-in-Residence at Vanderbilt University, sheis currently the Willa Cather Professor of English and Ethnic Studies (LatinxStudies) at the University of Nebraska in Lincoln, where she directs theInstitute for Ethnic Studies.1 - How did your firstbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous?How does it feel different?

My first book, TheTruth Book (2005), was a memoir that offered the true account of mychildhood as a Jehovah's Witness growing up in a violent and impoverished home.I ran away at fourteen, and the book also chronicles a little of the aftermathof that difficult decision. In addition, it explores the complexities of myCuban American heritage and the painful legacy of parental suicide.

Publishing TheTruth Book changed my life because I had previously concealed thoseelements of my past. They seemed too strange and shameful, and I was trying topass as normal in academia, a profession that was and remains normativelywhite and middle-class. To reveal those weird and troubling things about mypast, I had to overcome a great deal of fear—and decades of silence—which tooka great deal of courage, so that book was different for me than all those thathave followed it.

This newestbook, One Brilliant Flame, draws heavily upon my Cuban Americanfamily's background in Key West in the nineteenth century, a sociopoliticalmoment that is little-known today, and being able to recover that history andrestore it to public view has been very exciting and deeply moving to me.

2 - How did you cometo fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

Well, I startedwriting made-up stories when I was extremely young, and my early publishedworks were short stories. That just felt natural to me, as I was absorbed fromearly childhood in the world of storybooks and Bible stories and fairy tales.

It didn't occur to meto write a memoir until I was urged to do so in my 30s by an editor and afellow writer. I actually felt quite shy and reluctant to do so.

3 - How long does ittake to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially comequickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to theirfinal shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It depends somewhat onthe project, but on the whole, I lay a lot of mental groundwork before I beginto draft, and sometimes much of the work has happened in my mind before I putpen to paper. I write everything longhand, which is immensely helpful inslowing my process down and forcing me to choose among various mental versionsof each sentence as I write them.

I do love to revise,though, so I revise many times for various elements, and I always read everysection many times aloud for rhythm, emphasis, and musicality.

4 - Where does a workof prose usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end upcombining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" fromthe very beginning?

Well, my short storiesare quite happy to stay short. That's my favorite form. I generally know whenI'm embarking on a book; I can feel the weight and scope of it stretching outahead of me, even if I don't know exactly what will happen.

5 - Are publicreadings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort ofwriter who enjoys doing readings?

I do enjoy it. I'veheard a few awful, flat, droning readings, so I strive to make sure I providesomething intense and worthwhile. It's always top-of-mind that people couldjust as easily be at home enjoying their favorite series or reading a wonderfulbook. Instead, they've invested the time and effort to come out, so I try tofurnish an experience that will make them feel it was worth it.

6 - Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are youtrying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

Yes, very much so. ButI don't like to talk about them.

7 – What do you seethe current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one?What do you think the role of the writer should be?

To write. To risk. Towake up.

8 - Do you find theprocess of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I've been very luckyand have loved working with all my editors. I've balked at a few things,certainly, but it's always a good and edifying experience, and it almost alwaysstrengthens the work, which is what we're both serving.

9 - What is the bestpiece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

"Nothing can stopyou."

10 - How easy has itbeen for you to move between genres (short stories to the novel to essays tomemoir)? What do you see as the appeal?

Effortless. I don'tsee a particular appeal, exactly; it's just what happens.

11 - What kind ofwriting routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typicalday (for you) begin?

I don't. A typical daybegins with coffee by the fire, or coffee by an open window in warm weather,and sometimes I write in a notebook, but sometimes I don't.

12 - When your writinggets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word)inspiration?

It honestly doesn't.Sometimes my heart and soul feel depleted because I'm working too hard at mydayjob or due to political horrors in the larger world, so I feel drained andsad and despairing, but that's not specific to writing. When that happens, Ijust try to rest and be gentle with myself and remember to do a few extrathings I enjoy.

I do like JuliaCameron's notion of the artist's date very much.

13 - What fragrancereminds you of home?

The salty sea.

14 - David W. McFaddenonce said that books come from books, but are there any other forms thatinfluence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Trees and plants;music, yes; history, obviously; and visual art a great deal. I tend to gothrough phases of obsession with various artists: Artemisia Gentileschi,Remedios Varo, Käthe Kollwitz. Film, too, especially film noir: I love itssleek aesthetic, and hardboiled narration and dialogue crack me up.

15 - What otherwriters or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside ofyour work?

Katherine Mansfield,Jean Rhys, Colette, Margery Latimer, Sandra Cisneros, Mariama Bâ, Clarice Lispector, Louise Erdrich. Also James Joyce and William Faulkner.

16 - What would youlike to do that you haven't yet done?

Visit Churchill,Manitoba to see the Northern Lights, polar bears, and Beluga whales. Not duringthe same season, apparently, though.

17 - If you could pickany other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do youthink you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I would like to havemarried a forest ranger and been his little housewife up in a tower above thetrees. (So I could write, mainly.) I'm not a good cook or cleaner, so heprobably would have been disappointed.

I do like teaching, soI'm glad I stumbled into that. It's an excellent dayjob. I made a very poorwaitress—absent-minded, not really interested in the whole process.

18 - What made youwrite, as opposed to doing something else?

I always wrote. Idon't know the name of the thing inside that made me do so. I always just lovedwriting; it always felt natural and simple and necessary.

19 - What was the lastgreat book you read? What was the last great film?

Great is a tricky word. I genuinely loved the newtranslation of Forbidden Notebook by Alba de Céspedes, and Ivery much enjoyed the surprise of the gentleness of the stories in BananaYoshimoto's Dead-End Memories. In film, I'm still so moved andimpressed by No Intenso Agora (In the Intense Now).

20 - What are youcurrently working on?

My next book of shortstories and a suspense novel set outside Berlin.

April 13, 2023

Spotlight series #84 : Emmalea Russo

The eighty-fourth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring New York-based poet Emmalea Russo.The first eleven in the series were attached to the Drunken Boat blog, and the series has so far featured poets including Seattle, Washington poet Sarah Mangold, Colborne, Ontario poet Gil McElroy, Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Ottawa poet Jason Christie, Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough, Ottawa poet Amanda Earl, American poet Elizabeth Robinson, American poet Jennifer Kronovet, Ottawa poet Michael Dennis, Vancouver poet Sonnet L’Abbé, Montreal writer Sarah Burgoyne, Fredericton poet Joe Blades, American poet Genève Chao, Northampton MA poet Brittany Billmeyer-Finn, Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer from Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1 territory) poet, critic and editor Joshua Whitehead, American expat/Barcelona poet, editor and publisher Edward Smallfield, Kentucky poet Amelia Martens, Ottawa poet Pearl Pirie, Burlington, Ontario poet Sacha Archer, Washington DC poet Buck Downs, Toronto poet Shannon Bramer, Vancouver poet and editor Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Vancouver poet Geoffrey Nilson, Oakland, California poets and editors Rusty Morrison and Jamie Townsend, Ottawa poet and editor Manahil Bandukwala, Toronto poet and editor Dani Spinosa, Kingston writer and editor Trish Salah, Calgary poet, editor and publisher Kyle Flemmer, Vancouver poet Adrienne Gruber, California poet and editor Susanne Dyckman, Brooklyn poet-filmmaker Stephanie Gray, Vernon, BC poet Kerry Gilbert, South Carolina poet and translator Lindsay Turner, Vancouver poet and editor Adèle Barclay, Thorold, Ontario poet Franco Cortese, Ottawa poet Conyer Clayton, Lawrence, Kansas poet Megan Kaminski, Ottawa poet and fiction writer Frances Boyle, Ithica, NY poet, editor and publisher Marty Cain, New York City poet Amanda Deutch, Iranian-born and Toronto-based writer/translator Khashayar Mohammadi, Mendocino County writer, librarian, and a visual artist Melissa Eleftherion, Ottawa poet and editor Sarah MacDonell, Montreal poet Simina Banu, Canadian-born UK-based artist, writer, and practice-led researcher J. R. Carpenter, Toronto poet MLA Chernoff, Boise, Idaho poet and critic Martin Corless-Smith, Canadian poet and fiction writer Erin Emily Ann Vance, Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi, Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, Canadian poet Peter Jaeger, Birmingham, Alabama poet and editor Alina Stefanescu, Waterloo, Ontario poet Chris Banks, Chicago poet and editor Carrie Olivia Adams, Vancouver poet and editor Danielle Lafrance, Toronto-based poet and literary critic Dale Martin Smith, American poet, scholar and book-maker Genevieve Kaplan, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic ryan fitzpatrick, American poet and editor Carleen Tibbetts, British Columbia poet nathan dueck, Tiohtiá:ke-based sick slick, poet/critic em/ilie kneifel, writer, translator and lecturer Mark Tardi, New Mexico poet Kōan Anne Brink, Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Melanie Dennis Unrau, Vancouver poet, editor and critic Stephen Collis, poet and social justice coach Aja Couchois Duncan, Colorado poet Sara Renee Marshall, Toronto writer Bahar Orang, Ottawa writer Matthew Firth, Victoria poet Saba Pakdel, Winnipeg poet Julian Day, Ottawa poet, writer and performer nina jane drystek, Comox BC poet Jamie Sharpe, Canadian visual artist and poet Laura Kerr, Quebec City-area poet and translator Simon Brown, Ottawa poet Jennifer Baker, Rwandese Canadian Brooklyn-based writer Victoria Mbabazi, Nova Scotia-based poet and facilitator Nanci Lee, Irish-American poet Nathanael O'Reilly, Canadian poet Tom Prime and Regina-based poet and critic Jérôme Melançon.

The eighty-fourth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring New York-based poet Emmalea Russo.The first eleven in the series were attached to the Drunken Boat blog, and the series has so far featured poets including Seattle, Washington poet Sarah Mangold, Colborne, Ontario poet Gil McElroy, Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Ottawa poet Jason Christie, Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough, Ottawa poet Amanda Earl, American poet Elizabeth Robinson, American poet Jennifer Kronovet, Ottawa poet Michael Dennis, Vancouver poet Sonnet L’Abbé, Montreal writer Sarah Burgoyne, Fredericton poet Joe Blades, American poet Genève Chao, Northampton MA poet Brittany Billmeyer-Finn, Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer from Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1 territory) poet, critic and editor Joshua Whitehead, American expat/Barcelona poet, editor and publisher Edward Smallfield, Kentucky poet Amelia Martens, Ottawa poet Pearl Pirie, Burlington, Ontario poet Sacha Archer, Washington DC poet Buck Downs, Toronto poet Shannon Bramer, Vancouver poet and editor Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Vancouver poet Geoffrey Nilson, Oakland, California poets and editors Rusty Morrison and Jamie Townsend, Ottawa poet and editor Manahil Bandukwala, Toronto poet and editor Dani Spinosa, Kingston writer and editor Trish Salah, Calgary poet, editor and publisher Kyle Flemmer, Vancouver poet Adrienne Gruber, California poet and editor Susanne Dyckman, Brooklyn poet-filmmaker Stephanie Gray, Vernon, BC poet Kerry Gilbert, South Carolina poet and translator Lindsay Turner, Vancouver poet and editor Adèle Barclay, Thorold, Ontario poet Franco Cortese, Ottawa poet Conyer Clayton, Lawrence, Kansas poet Megan Kaminski, Ottawa poet and fiction writer Frances Boyle, Ithica, NY poet, editor and publisher Marty Cain, New York City poet Amanda Deutch, Iranian-born and Toronto-based writer/translator Khashayar Mohammadi, Mendocino County writer, librarian, and a visual artist Melissa Eleftherion, Ottawa poet and editor Sarah MacDonell, Montreal poet Simina Banu, Canadian-born UK-based artist, writer, and practice-led researcher J. R. Carpenter, Toronto poet MLA Chernoff, Boise, Idaho poet and critic Martin Corless-Smith, Canadian poet and fiction writer Erin Emily Ann Vance, Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi, Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, Canadian poet Peter Jaeger, Birmingham, Alabama poet and editor Alina Stefanescu, Waterloo, Ontario poet Chris Banks, Chicago poet and editor Carrie Olivia Adams, Vancouver poet and editor Danielle Lafrance, Toronto-based poet and literary critic Dale Martin Smith, American poet, scholar and book-maker Genevieve Kaplan, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic ryan fitzpatrick, American poet and editor Carleen Tibbetts, British Columbia poet nathan dueck, Tiohtiá:ke-based sick slick, poet/critic em/ilie kneifel, writer, translator and lecturer Mark Tardi, New Mexico poet Kōan Anne Brink, Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Melanie Dennis Unrau, Vancouver poet, editor and critic Stephen Collis, poet and social justice coach Aja Couchois Duncan, Colorado poet Sara Renee Marshall, Toronto writer Bahar Orang, Ottawa writer Matthew Firth, Victoria poet Saba Pakdel, Winnipeg poet Julian Day, Ottawa poet, writer and performer nina jane drystek, Comox BC poet Jamie Sharpe, Canadian visual artist and poet Laura Kerr, Quebec City-area poet and translator Simon Brown, Ottawa poet Jennifer Baker, Rwandese Canadian Brooklyn-based writer Victoria Mbabazi, Nova Scotia-based poet and facilitator Nanci Lee, Irish-American poet Nathanael O'Reilly, Canadian poet Tom Prime and Regina-based poet and critic Jérôme Melançon.The whole series can be found online here.

April 12, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Kevin Sampsell

Kevin Sampsell

is the authorof a memoir (

A Common Pornography

), a novel (

This Is Between Us

),and a collection of collages and poems (

I Made an Accident

). He lives inPortland, Oregon and runs the influential small press, Future Tense Books. An award-winning bookseller,he has worked at Powell's City of Books since 1997. His collages have appearedon album covers, book covers, and in many publications like KolajMagazine, The Rumpus, The Weird Show, Chicago Quarterly Review, LittleEngines, and Black Candies. His writing has appearedin Paper Darts, Southwest Review, Salon, Poetry Northwest, McSweeney's,Tin House, and elsewhere. He is the co-curator of Sharp Hands Gallery, a website featuringinternational collage artists.

Kevin Sampsell

is the authorof a memoir (

A Common Pornography

), a novel (

This Is Between Us

),and a collection of collages and poems (

I Made an Accident

). He lives inPortland, Oregon and runs the influential small press, Future Tense Books. An award-winning bookseller,he has worked at Powell's City of Books since 1997. His collages have appearedon album covers, book covers, and in many publications like KolajMagazine, The Rumpus, The Weird Show, Chicago Quarterly Review, LittleEngines, and Black Candies. His writing has appearedin Paper Darts, Southwest Review, Salon, Poetry Northwest, McSweeney's,Tin House, and elsewhere. He is the co-curator of Sharp Hands Gallery, a website featuringinternational collage artists.1 - How did your first book change your life? Howdoes your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feeldifferent?

Technically, my first book (that wasn't a chapbook)was a self-published collection of stories, poems, and word collagescalled How to Lose Your Mind With the Lights On (Future TenseBooks, 1994). It's pretty wild to think about how long ago that came out. Ithink it changed my life because it was my first experience doing everythingall on my own. I probably could have used an outside editor, but if Ilooked at that book now, I'm sure I'd still appreciate a lot of its goofyweirdness. My most recent book, I Made an Accident, is a collectionof collages and poems. In some ways it feels similar to that first book becauseit's a hodge-podge of things meant to surprise, delight, and even confoundyou.

And how does it feel different? The collages are alot better this time around.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposedto, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I started in high school. My best friend and Iwould write weird little poems, but we didn't even call it poetry. We calledthem pieces. We were basically just trying to crack each other up,which I think was the early mission of the surrealists too, right? Iwanted to write poems that were more Monty Python than Robert Frost.

3 - How long does it take to start any particularwriting project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slowprocess? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or doesyour work come out of copious notes?

Over the years, it's been all over the place. Ithink I was more focused and compulsive for the first ten years or so of mywriting life. I'd write whole stories pretty quickly, and sometimes severalpoems a day. I'm much slower now and I edit myself a lot more. But I knowthat writing, and especially publishing, is a slow game. It doesn't bother meto go slow now. But I'm always working on something, and a lot of times copiousnote-taking is involved.

4 - Where does a poem or work of prose usuallybegin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into alarger project, or are you working on a "book" from the verybeginning?

Two of my books, the novel, This Is BetweenUs, and my memoir, A Common Pornography, were written in anon-linear fashion. I'd write chapters or scenes and then later spread them allout on the floor and figure out what order they needed to go. I finished anovel recently though that I wrote in a more traditional fashion, from thebeginning to the end. And I challenged myself to write longer chapters for thisbook too. Off and on, it took about eight years. Who knows if it will ever getpublished.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to yourcreative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I do enjoy doing readings and I actually host abouta hundred or more readings every year at my job (Powell's Books in Portland,Oregon). I think I'm a good reader and I'm good in front of an audience, sosometimes it helps sell a few more books when I can deliver an entertainingreading. I notice that at my job too–a great reading sells a lot more booksthan a mediocre one.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behindyour writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work?

One of the main things I think about when writingis how people interact with each other and how relationships work. I don'tthink I could convincingly write something very engaging about nature orpolitics. I'm captivated by people in the world and all the strange things thatcan happen to them. I especially love writing about ordinary people who findthemselves in unexpected situations they probably don't want tobe in. More recently, I do find myself fixating on death, loss, and griefas central themes.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writerbeing in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role ofthe writer should be?

There are all kinds of writers and they all havedifferent intentions or missions. I don't really think about what"role" they're trying to fill and I don't thinkthey "should be" attempting to define the larger culture. Ithink questions like that feel too pointed and put too much pressure on writersto do something that others will see as "Important" (with a capitalI). Writing is an art form that can do anything and be anything, and itshouldn't always concern itself with influence.

8 - Do you find the process of working with anoutside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

I love it for the most part. I want to know that mywriting is making sense to another human. Most of the time, if I get a story oressay published somewhere, there is very little input from an editor. But thetimes when I've gotten notes from editors, it's been really helpful andeye-opening.

As an editor myself, I love it when I can help awriter make their work better, whether it be through small edits, suggestions,or playful challenges. With Future Tense, I work alongside my co-editor, EmmaAlden, and it's appreciable to have her input and notes. We usually workthrough a shared Google doc and seeing how our thoughts help shape the bookwe're working on, makes it really enjoyable.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard(not necessarily given to you directly)?

A publisher friend told me a long time ago that Ishould be writing off things for my tax returns each year. I found a good taxlady who helped me figure out what I can and cannot do, and frankly, it waslife-changing.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move betweengenres (fiction to poetry to memoir to collage)? What do you see as the appeal?

I think it's been a natural progression. I mean, Idon't intentionally say, I have to do this genre now. I'vealways liked to make different things depending on whatever I might feel mostinterested in. For a while, it was personal essays, and then it was flashfiction, and eventually it was visual art. I even had a haiku phase! And Iadmire other people who can express themselves in various forms aswell–musicians who can write novels, poets who can write memoirs, actorswho can paint. Having a range of interests and talents has helped me not getstagnant. It gives me a sense of creative freedom, and also permission to experiment.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend tokeep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Ugh. I have such a bad writing routine most of thetime. But the important thing is that I stick to it and I do have stretcheswhen I can be focused and GSD. That stands for "Get Shit Done" and atthe end of the day, that's what gives me satisfaction, whether it's writing,editing, collaging, stuff at work, etc. The name of the game is GSD.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do youturn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Reading is the main kickstarter. It wakes up mybrain and gives me ideas, especially poetry or a good disjointed lyricessay or something like that. Sometimes a good walk can do the trick too.Late night collaging can also inspire.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Sometimes, when my cat, Susan, yawns, I lean in tosmell her cat breath, which I find so cute and comforting. I love herthat much.

The smell of baking brownies is probably a closesecond.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books comefrom books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whethernature, music, science or visual art?

Art for sure. Collages especially. I amobsessed with collage art and have made a whole new world of friends inthat world over the past few years. You could look at some collage art andprobably transcribe it into poems. And yes, I've always loved music. And moviestoo! Good, slow movies about people. I don't really like action or superheromovies.

15 - What other writers or writings are importantfor your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Early favorites like Richard Brautigan, Diane Williams, Garielle Lutz, Gordon Lish, Larry Brown, and Mark Leyner were key tomy enthusiasm for writing and reading. There were also a lot of British musicwriters I enjoyed a great deal, before I was even a serious reader inmy twenties. A lot of friends of mine are writers I am constantly inspiredby as well: Kimberly King Parsons, Miriam Toews, Zachary Schomburg, Caren Beilin, Shane Kowalski. Plus the brilliant graphic novelist Daniel Clowes.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yetdone?

I'd love to have a book reviewed in EntertainmentWeekly or record an album of Prince covers.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation toattempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would haveended up doing had you not been a writer?

I didn't go to college, so I always imagined myselfworking at a factory or something. I think being a mailman would be kind ofcool. Or a third string quarterback in the NFL, so I could make a lot of moneyand probably never have to play in a real game. Working at a bookstoreisn't bad though.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing somethingelse?

I wasn't smart enough to go to college or braveenough to join the military. I wanted to be a radio DJ and I was for a fewyears before moving to Portland (in 1992). Working in the world of books waskind of an accident. I just ended up here and held on to it because it wasrewarding in a nurturing and creative way. Not sure if that answered yourquestion very well. What makes me write is the constant urge to create and makethings.

19 - What was the last great book you read? Whatwas the last great film?

I really loved Someone Told Me byJay Ponteri. It was published by a Portland small press so it might be hard tofind, but it's an outstanding book of thoughtfully probing and beautiful lyricessays. My favorite film of last year was Marcel the Shell With Shoes On. It made me weep.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I'm working on a couple of Future Tense projectsand a new group show at my virtual collage gallery, Sharp Hands Gallery. As faras writing, I'm working on a couple of essays, or maybe they're more like longconceptual poems. One is about things in Portland turning into other things andanother one is about things I don't remember–like the opposite of JoeBrainard's I Remember.

April 11, 2023

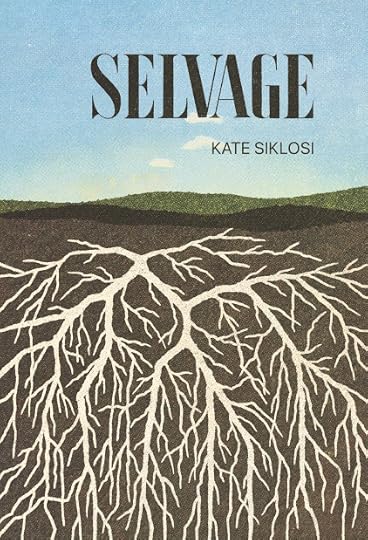

Kate Siklosi, SELVAGE

my nagypapawas an immigrant and immigrant children without a mother are dangerous. they hadsettled in a small oil town and he started to build a small house with his ownhands. all i know of that night is that it was dark and there was screaming. i’mdrinking tea when my aunt recalls looking back on her father falling to hisknees. she was old enough then to know that the axis of their lives and thoseto come had shifted. an inverted arch crouching in concavity. each child acoordinate clinging to a dead line. one took his life one destroyed others. therest have done their best to keep grounded. the fact of the matter is they allgrew up against a backdrop of negative space. each a stellar burst a collapsedstar in a hellbent universe. notwithstanding, here. i. (“reasonable grounds”)

Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi’s second full-length collection,following the stunning visuals of leavings (Malmö, Sweden: TimglasetEditions, 2021) [see my review of such here], is SELVAGE (Toronto ON:Invisible Publishing, 2023). Set in four sections of stitch and carve, Siklosiwrites of new motherhood against intergenerational trauma, leaves andimmigration, edges and a blurred centre. Whereas leavings focused onimages of physical objects set with text, SELVAGE focuses instead on thetext itself, while still offering an extension of the visuals and visualelements presented in that full-length debut. She writes of stitch and vein, ablend of images (including full colour), offering text on seeds and leaves, andweaving in elements of language from the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedomsthrough examining a family history of devastating losses and their ripplingeffects. “leafing through the charter,” she writes, as part of the opening sequence-section,“i am a loss. when things shall be deemed it can both protect and threaten atonce.” As the press release offers: “Kate Siklosi grew up in a family shroudedin a veil of mystery of how they came to be: the scant facts about hergrandparents and how they came to live in Canada after escaping Hungary underthe Iron Curtain in 1956; her nagymama (grandmother) dying in childbirth; hernagypapa’s (grandfather’s) grief at finding himself alone without his family inthis new country (subsequently taking out his grief by setting fire to theChildren’s Aid building and then dying in jail); the mysterious ‘neighbour’ whosexually abused Kate’s brother and cousins.”

Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi’s second full-length collection,following the stunning visuals of leavings (Malmö, Sweden: TimglasetEditions, 2021) [see my review of such here], is SELVAGE (Toronto ON:Invisible Publishing, 2023). Set in four sections of stitch and carve, Siklosiwrites of new motherhood against intergenerational trauma, leaves andimmigration, edges and a blurred centre. Whereas leavings focused onimages of physical objects set with text, SELVAGE focuses instead on thetext itself, while still offering an extension of the visuals and visualelements presented in that full-length debut. She writes of stitch and vein, ablend of images (including full colour), offering text on seeds and leaves, andweaving in elements of language from the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedomsthrough examining a family history of devastating losses and their ripplingeffects. “leafing through the charter,” she writes, as part of the opening sequence-section,“i am a loss. when things shall be deemed it can both protect and threaten atonce.” As the press release offers: “Kate Siklosi grew up in a family shroudedin a veil of mystery of how they came to be: the scant facts about hergrandparents and how they came to live in Canada after escaping Hungary underthe Iron Curtain in 1956; her nagymama (grandmother) dying in childbirth; hernagypapa’s (grandfather’s) grief at finding himself alone without his family inthis new country (subsequently taking out his grief by setting fire to theChildren’s Aid building and then dying in jail); the mysterious ‘neighbour’ whosexually abused Kate’s brother and cousins.”Theonline Merriam-Webster offers that “selvage” refers to “the edge oneither side of a woven or flat-knitted fabric so finished as to preventraveling. specifically : a narrow border often of different or heavier threadsthan the fabric and sometimes in a different weave. : an edge (as of fabric orpaper) meant to be cut off and discarded.” The poems in SELVAGE arestitched together as four sequences of prose blocks, lyric fragments and image—“reasonablegrounds,” “field notes,” “lockstitch” and “radicle”—that quilt a larger narrativeof crumbles, holds, breaks, language patters and splinters, able to entirely smashedto pieces but held together by thread, across, one might say, that narrowborder; of how, near the end of the opening sequence, “drought tolerance ispassed / from parent tree to child.” There is something quite fascinating,also, in how Siklosi seeks, through a blend of image and text, to examine a storythat begins with her Hungarian grandparents, forced to leave home to emigrateto Canada during the same period as Calgary poet Helen Hajnoczky’sgrandparents, something Hajnoczky worked to examine in her own way through theblend of visuals and text of her own second collection, Magyarázni(Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2016) [see my review of such here]. Accumulatinginto a book-length poem, Siklosi’s scraps, threads and fragments pull at those buriedelements of family lore, seeking the story to see what pulls apart,simultaneously held together by the determination and a story, notwithstanding.“being is a maze.” she writes, as part of “lockstitch,” “the sky is stitched in.cut the selvage by taking the people upon entry. you can create laws, like thatbush and that corner and how high. You can even manage it so it appears like aliving thing from space: branches and limbs with people roaming through. thethread is of course the word that holds it together: five hearts searchingtaxed land held down with pins.” Or, as part of the third section:

Everyone has the followingfundamental freedoms:

what if i told younothing dropped.

every citizen of Canadahas the right to

a landmine made ourcalves burn with

in time of real orapprehended war,

coming home. handful ofroots explode

the right to enter,remain in and leave

into light. skylarks on apond.

pursue the gaining of alivelihood

look, the year is nowgone.

life, liberty, andsecurity of the person.

i have my dad’s waves.

compelled to be a witnessin

he made me aconstellation to swing from.

law recognized by thecommunity of nations

i don’t have his hands socan’t build myself

not to be tried for itagain

a country but i haveenough ink to sink

not to be tried orpunished for it again

us into a river, bone andmind, and with

time of commission andthe time of sentencing,

this i’ll dive in andgive you everything but

a witness who testifies

the currents to remaininside his

freedoms shall not beconstrued as

rattled lungs and mistake

treaty or other rights

his ribs for home.

Thereis something, of course, quite natural to having one’s first child that promptsa particular look back at one’s history, one’s foundations; to attempt toreconcile particular elements of the past for the sake of being able to moveforward. In this way, one could even point to comparable titles, such as JessicaQ. Stark’s recent Buffalo Girl (Rochester NY: BOA Editions, 2023) [see my review of such here], as Siklosi writes through the limitations and effectsof a document, of a story, upon the body, utilizing text and stitch as a way tounfurl both family and archive, stitching one word immediately upon andfollowing another. “as if,” she writes, as part of the fourth and finalsection, “to survive was a baseline / life blossoms from a wound / how does oneescape a cycle?”

April 10, 2023

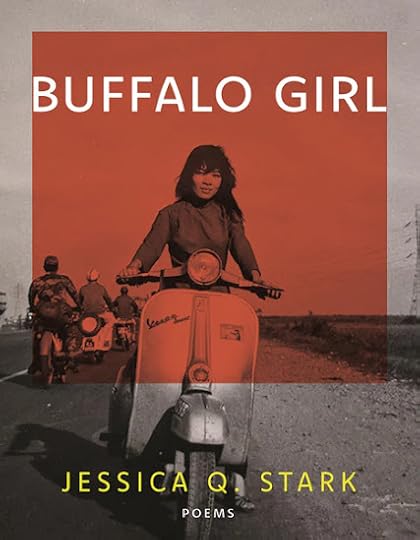

Jessica Q. Stark, Buffalo Girl

My mother said when I wasborn, she was afraid.

Women born in the Year ofthe Tiger are fabled as

too much in their ownstory. They’re risk-takers in

this world, whichtypically spells feminine ruin.

She laughs often at hersmall monster, leaping again into dark.

She was also afraid ofthe fourth scar;

they said she’d be rippedapart between white walls.

This country is not forthe faint-hearted; I will wear it.

This is the sentence inmy body, decorated.

I cannot (not) take itoff. (“On Passing”)

Jacksonville, Florida-based poet and editor Jessica Q. Stark’s second full-length poetrycollection, following

Savage Pageant

(Birds LLC, 2020) [see my review of such here], is

Buffalo Girl

(Rochester NY: BOA Editions, 2023). As thepress release offers, Buffalo Girl writes the author’s “mother’s fraughtimmigration to the United States from Vietnam at the end of the war through thelens of the Little Red Riding Hood fairy tale.” As Stark offers at the offsetof the poem “Phylogenetics,” “When it began isn’t clear, but isn’t it obvious that we always had a knack / for storiesabout little girls in danger?” Stark examines, through collages of text andimage, an articulate layerings of breaks and tears, intermissions anddeflections; examining how and why stories work so hard to remove female agency.“In this body is my mother’s body,” she writes, as part of the extended “OnPassing,” “who paid the fantastic price in / fairy tales written mostly by men.”She offers elements of her mother, including pictures of her mother repeatedlyon a scooter, providing a curious echo of Hoa Nguyen’s A Thousand Times YouLose Your Treasure (Wave Books, 2021) [see my review of such here], acollection that explored her own mother’s time spent as part of a stunt motorcycletroupe in Vietnam. “You can paint a woman // by the river bank,” Stark writes, to open the poem “ConCào Cào,” “but // you can’t ever imitate // a sound, fully. This story is //not simple.”

Jacksonville, Florida-based poet and editor Jessica Q. Stark’s second full-length poetrycollection, following

Savage Pageant

(Birds LLC, 2020) [see my review of such here], is

Buffalo Girl

(Rochester NY: BOA Editions, 2023). As thepress release offers, Buffalo Girl writes the author’s “mother’s fraughtimmigration to the United States from Vietnam at the end of the war through thelens of the Little Red Riding Hood fairy tale.” As Stark offers at the offsetof the poem “Phylogenetics,” “When it began isn’t clear, but isn’t it obvious that we always had a knack / for storiesabout little girls in danger?” Stark examines, through collages of text andimage, an articulate layerings of breaks and tears, intermissions anddeflections; examining how and why stories work so hard to remove female agency.“In this body is my mother’s body,” she writes, as part of the extended “OnPassing,” “who paid the fantastic price in / fairy tales written mostly by men.”She offers elements of her mother, including pictures of her mother repeatedlyon a scooter, providing a curious echo of Hoa Nguyen’s A Thousand Times YouLose Your Treasure (Wave Books, 2021) [see my review of such here], acollection that explored her own mother’s time spent as part of a stunt motorcycletroupe in Vietnam. “You can paint a woman // by the river bank,” Stark writes, to open the poem “ConCào Cào,” “but // you can’t ever imitate // a sound, fully. This story is //not simple.”Playingoff the traditional American folk song “Buffalo Gals,” Stark tweaks the lyrics,offered as part of the poem “The Old Man in the Tree,” which ends: “And an oldman somewhere high // was feeling satisfied with / his meal and his lodging and// he sang: // Oh, Buffalo Girls, // won’t you come / out tonight, //come out tonight, / come out tonight, // Oh, Buffalo Girls, // won’t you comeout tonight, // and dance by the / light of the moon?” Stark offers multipleimages and tales of her mother blended with flora and fauna, as well as theimage of a figure, often male, and usually obscured or erased through that samefoliage; hidden, suggesting a wolf in the wild. “History makes little bundlesout / of the unthinkable,” she writes, as part of the title poem, “young boyscarve // three-foot breasts // to keep your story otherworldly and /ridiculous; a crisp blade slips // from view [.]”

Buffalo Girl writes out threads of Stark’s mother’shistory, and examines the cultural fascination with stories of innocent girlsand bad wolves, writing a fairy tale framing multiple versions of Little RedRiding Hood, one across another. In many ways, she writes her way into being; ofherself into that history and lineage of her mother, from one culture intoanother, and a lineage that now includes her own son. Attempting to navigatethe complications of movement and wolves, determination and difference, Stark’slyrics explore her mother’s history to place her mother on solid ground, sothat she, too, might be able to find ground, and come to terms with her mother’sstories. “For years I tried on different stories about my body,” the poem “OnPassing” begins, “to use the body as a rinsing husk. // Language here is also adelicate peapod, a shell / that forms the world and its fantastic borders. //For years I ignored the sentence in my body. // Who came and who went—a blankledger.” Stark may begin with Red Riding Hood and a myriad of wolves, encountered,fought and avoided, but this is a collection through which she explores anddiscovers what her mother taught her, whether through example or presentation,as well as what her mother is actually made of, despite violence, trauma, lossand what wolves are capable of; and what her mother is made of is considerable.Or, as the poem “Near-Death Experience” ends:

How the dark

imprints a tiny tattoo

in the shape of life’s

physical humor. I talk

my mother into

visiting my new home

in Florida. I will

see her soon.

She will say

how much

closer death

is to her now. I have

plans. I will pick

her up in an automobile

that’s painted red.

I will reserve a day

for regarding the

big, vast sea

near which

I’ve made my home.