Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 93

April 29, 2023

Natalie Eilbert, Overland

My review of Natalie Eilbert's Overland (Copper Canyon, 2023) [see my review of her prior book here] is now online at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics.

My review of Natalie Eilbert's Overland (Copper Canyon, 2023) [see my review of her prior book here] is now online at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics.April 28, 2023

Camille Martin, R

Light is not

inevitable. Overshot it

or not yet there.

Nothing, for that

matter. In any case,

not arrived. Anything

could have been

otherwise.

Thelatest from Toronto poet and collagist Camille Martin is the poetry title,

R

(Toronto ON: Rogue Embroyo Press, 2023), following a list of books andchapbooks over the years, including Plastic Heaven (New Orleans:single-author issue of Fell Swoop, 1996), Magnus Loop (Tucson,Arizona: Chax Press, 1999), Rogue Embryo (New Orleans: Lavender Ink,1999), Sesame Kiosk (Elmwood CT: Potes and Poets, 2001),

Codes of Public Sleep

(Toronto ON: BookThug, 2007),

Sonnets

(Shearsman Books,2010), If Leaf, Then Arpeggio (above/ground press, 2011),

Looms

(Shearsman Books, 2012), Sugar Beach (above/ground press, 2013) and

Blueshift Road

(Rogue Embryo Press, 2021) [see my review of such here]. It isinteresting that, after a period of relative silence, she has quietly reemergedthrough self-publication, offering a first (Blueshift Road) and now thissecond full-length collection (R), since the onset of Covid-19 lockdowns.Still, with pieces that originally appeared in a handful of journals andanthologies, as well as in the chapbooks Magnus Loop and Sugar Beach,it suggests that this particular manuscript has been gestating for some time. Theone hundred and fifty pages of this collection are predominantly articulated asa sequence of short, untitled, haiku-like bursts, each carved into the centreof the page. It is almost as though these meditative bursts are attempts toachieve and articulate balance, seeking a grounding effect through this sequenceof carved sketchworks. Each poem is thoughtful, observational; settling into short-formthought and speech via playful scraps. “plastic raspberries linked with safetypins,” she writes, mid-way through the collection, “dull flavour of stewed rubies// stoplight blinking in a junkyard [.]” Each poem offers sketch and pausethrough an effect of collage, suggesting a construction similar to the imagespresented on the front and back cover: a suggestion of simultaneous image andidea, carved, clipped, collected and formed into poem-shapes that retain theircollage-simultaneity through each tightly-packed singular effect. There is anenormous amount going on in these poems, clearly.

Thelatest from Toronto poet and collagist Camille Martin is the poetry title,

R

(Toronto ON: Rogue Embroyo Press, 2023), following a list of books andchapbooks over the years, including Plastic Heaven (New Orleans:single-author issue of Fell Swoop, 1996), Magnus Loop (Tucson,Arizona: Chax Press, 1999), Rogue Embryo (New Orleans: Lavender Ink,1999), Sesame Kiosk (Elmwood CT: Potes and Poets, 2001),

Codes of Public Sleep

(Toronto ON: BookThug, 2007),

Sonnets

(Shearsman Books,2010), If Leaf, Then Arpeggio (above/ground press, 2011),

Looms

(Shearsman Books, 2012), Sugar Beach (above/ground press, 2013) and

Blueshift Road

(Rogue Embryo Press, 2021) [see my review of such here]. It isinteresting that, after a period of relative silence, she has quietly reemergedthrough self-publication, offering a first (Blueshift Road) and now thissecond full-length collection (R), since the onset of Covid-19 lockdowns.Still, with pieces that originally appeared in a handful of journals andanthologies, as well as in the chapbooks Magnus Loop and Sugar Beach,it suggests that this particular manuscript has been gestating for some time. Theone hundred and fifty pages of this collection are predominantly articulated asa sequence of short, untitled, haiku-like bursts, each carved into the centreof the page. It is almost as though these meditative bursts are attempts toachieve and articulate balance, seeking a grounding effect through this sequenceof carved sketchworks. Each poem is thoughtful, observational; settling into short-formthought and speech via playful scraps. “plastic raspberries linked with safetypins,” she writes, mid-way through the collection, “dull flavour of stewed rubies// stoplight blinking in a junkyard [.]” Each poem offers sketch and pausethrough an effect of collage, suggesting a construction similar to the imagespresented on the front and back cover: a suggestion of simultaneous image andidea, carved, clipped, collected and formed into poem-shapes that retain theircollage-simultaneity through each tightly-packed singular effect. There is anenormous amount going on in these poems, clearly.shadow concealing

colour, colour

shedding cells

April 27, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Meghan Kemp-Gee

Meghan Kemp-Gee's debut full-length poetry collection

The Animal in the Room

is forthcoming from Coach House Books in May 2023. She is also the author of two chapbooks (

What I Meant to Ask

and The Bones & Eggs & Beets) and co-creator of Contested Strip, the world’s best comic about ultimate frisbee (and soon to be a graphic novel).

Meghan Kemp-Gee's debut full-length poetry collection

The Animal in the Room

is forthcoming from Coach House Books in May 2023. She is also the author of two chapbooks (

What I Meant to Ask

and The Bones & Eggs & Beets) and co-creator of Contested Strip, the world’s best comic about ultimate frisbee (and soon to be a graphic novel).1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Obviously, we poets have to be good at spending a lot of time and energy on our work with very little external validation. I've been so fortunate to have a few big successful milestones recently, including getting into an awesome poetry PhD program and my first book getting accepted for publication at a wonderful publisher. And to be honest, that external validation does work on me! It makes me feel like I KNOW what I'm doing, instead of just hoping I know.

So I feel like my work these days is more self-assured and ambitious. I don't know where that confidence boost is going to take me. We'll see.

More than anything, it means everything to me that other people are actually reading what I write and spending time with my work. That's why I write. It means everything.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or nonfiction?

The mediums I work in most often are poetry, comics, and screenwriting. I'm not sure exactly why, but it's very rare that I have an idea I want to explore through prose more than I want to explore it through a poem or a scene or a comic. The reasons for that are completely mysterious to me, because I really enjoy reading fiction and nonfiction! I just rarely have an impulse towards creating it.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

I am a pretty fast, hard writer once I get going! I fear and admire poets who carefully revise and slowly edit over months and months, but I don't work like that!

Whether we're talking about a single poem or a giant project, something tends to blindside me out of nowhere and whine at me until it gets finished. Whatever "it" is, it comes and looks for you. I'm a big believer that if a poem is talking to you, it needs to be written right away, as much as you can. It might not get finished that day, but I'm always grateful when I follow that voice or that whine.

Once I've drafted a poem, I often revise it as many times as I need to, once or twice or twenty times, within the first day or two. I don't need to finish it, but I need to finish it as much as I can. A few of my poems, about 10 percent, get stuck in the early stages, and those are the ones you just put away and wait until you know what to do with them, weeks or years later.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I used to be a very poem-focused poet. I liked the idea of the self-contained unit, the little room -- neat and tidy and a world of its own.

I still like thinking about my poems like that! But ever since I finished writing Animal in the Room I've been increasingly interested in what I could do with sequences and interconnected series of poems, including my chapbooks and full-length book projects. Right now, I love playing with repetition, because it creates alternative realities, rhizomes, new connections. I'm fascinated by those branches, tensions, links, and ligaments between pages. In comics theory, they talk about "hyperlinks" or "arthrology" -- the study of connections between and across texts.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I don't have a huge amount of experience with readings yet, but I do enjoy them! I want to do more! I put a lot of care into how my work sounds, because I hope some readers will want to read the poems out loud.

I also really love the experience of reading with other poets and writers, firstly because I like meeting them, and also because of those wonderful, unexpected connections between poems that often spring up at public readings. I love those!

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

Sometimes I'm concerned that I'm not intentional enough in formulating a theoretical framework for what I'm writing. My process is very form-based -- I like to pick one or more patterns or formal features and just see where they take me. Let the poem go where it wants to go.

But I also recognize that that's just a process, not a theory. If you write like me, one of the things you have to be concerned about, and responsible about, is that a form-first process doesn't absolve you of your authorship. You're still responsible for what the poem does.

So basically, my theoretical concerns, my process, and my questions all have to do with the same kind of thing: how meaning and structure work together, and create each other, again and again and every time we write. And every time we read, or try to understand the physical world, that's also what's happening: meaning versus structure. I guess Meaning/Structure and Theory/Practice map onto each other, to a certain extent.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I think there are many necessary roles for all kinds of writers and artists in our culture. Personally, I think of myself as doing a craft -- my job is to create things that are useful or interesting or pleasing to someone. There's a good Dylan Thomas quote that says that a poem is a contribution to reality. I like to think about my work like that.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Last summer I had the great honor of working with Coach House, and with Susan Holbrook to edit my poetry manuscript. I was really thrilled when my book was accepted for publication, but I'll never forget talking to Susan on the phone for the first time. She immediately summarized the whole book in this perfect, insightful, intellectual way, better than I ever could have. I was floored. I think it was the first moment in my life when I felt someone had really understood my work -- not just what an individual poem might mean, but my intentions, and everything I was trying to do on a larger scale. I'm so grateful to her for that moment. I'll never forget it.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

When I met Phoebe Wang at UNB in 2021 she gave me some wonderful advice: to be patient. She told me that I could write quickly and impatiently, but then I had to be very patient about publishing, career, and everything that comes after. I'm not a patient writer, but I think that was good advice!

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to collaborating on a graphic novel)? What do you see as the appeal?

People have told me they find this weird, but it's always easy and fun for me to move between genres! I enjoy the variety: comics, poetry, screen. They're all very different in terms of skills, audience, collaboration, everything. But the more I work in multiple genres, the more I discover all these interesting connections and transferable skills & techniques. Anyway, the main appeal to me is that I'm just following my creative interests, and following opportunities to work with artists and projects I like.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I would like to have a regular schedule, but between studying, teaching, writing, and sports, every day is a bit different! On my ideal day, I go to the gym first thing in the morning, then have two or three big blocks of serious work time after that. But the ideal day isn't a real day, is it?

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I don't usually feel stalled. But I find I'm most productive and pleased with myself when I'm writing towards a project. I like that feeling of a target, where every little scrap of an idea or line seems pointed towards a larger thing.

If I'm not currently working on a project, I invent one, like writing a sonnet just because, or writing about the last TV show I watched, or whatever. If I'm really stuck, I just do some editing of my own poems, or just read someone else's poems. That always does the trick.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

My partner James is a brilliant baker! A pot of coffee brewing and something baking in the oven are the ultimate home-y smell for me.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Movies, nature, and visual art are huge influences and frequent topics in my poems! Recently I'm experimenting with poems about sports and athletes, which is a new and unfamiliar influence.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

This is such a difficult question because there are too many to narrow it down! I'm just going to throw out four writers who are at the tip of my tongue today because I've re-read them recently: Louise Gluck, Jack Kirby, James Baldwin, Gord Downie, Joy Harjo.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

In poetry, one of my dreams is to work collaboratively with visual artists or musicians! I'd love to publish a poetry-comic hybrid text, or to write words for songs, operas, or live performances.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I've often considered becoming a yoga teacher! Maybe I'll still do that at some point?

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Like a lot of us, I think I do this because I wouldn't be completely satisfied doing something else. Or at least I wouldn't be completely satisfied. I enjoy a lot of different types of work. Teaching makes me happy. Coaching sports and playing sports does too. I enjoyed working on movies and doing script consulting. But ultimately I think I need to write. Like your question says, something made me write.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Book: Haruki Murakami's What I Talk About When I Talk About Running

Film: Fire of Love

20 - What are you currently working on?

I am right on the exhilarating cusp between two big poetry projects!

I just hit "send" on a manuscript called Nebulas, which is about space, strawberries, and Walt Whitman. I think it's the best work that I've ever done and I can't wait to share it with everyone.

My next big thing is a series of lyric poems about dead and injured athletes. I don't want to say too much because it's still taking its shape! It's cooking!

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

April 26, 2023

Joe Hall, Fugue and Strike

FUGUE 11 | HELLO, MYSLEEP

Hello, my sleep, my dawnthing

milk welling in the eyes

of night—if you shouldlet me

if 6 am should slice this

cannister, carry the eggof this thought

in its mouth through thecolliding

fonts of sensoria—the eyesof night

open, it all leaks out

this sleep just a plane

on the polyhedron: sleep,our sleep

rising over the world (“FROMFUGUE & FUGUE”)

Thefourth full-length collection by Buffalo, New York “poet, critic and junkbookmaker” Joe Hall, following

Pigafetta Is My Wife

(Boston MA/ChicagoIL: Black Ocean, 2010),

The Devotional Poems

(Black Ocean, 2013) and

Someone’s Utopia

(Black Ocean, 2018) is Fugue and Strike: Poems by Joe Hall (BlackOcean, 2023). Fugue and Strike is constructed out of six poem-sections—“FromPeople Finder Buffalo,” “From Fugue & Strike,” “Garbage Strike,” “I HateThat You Died,” “The Wound” and “Polymer Meteor”—ranging from suites of shorterpoems to section-length single, extended lyrics. Hall’s poems are playful, savageand critical, composed as a book of lyric and archival fragments, cutting observations,testaments and testimonials. “[…] to become a poet / is to kill a poet,” hewrites, as part of the poem “FUGUE 6 | JACKED DADS OF CORNELL,” “cling to apoet / in the last hour, before slipping into the drift / atoms of talk bounce incylinders down Green St, predictive tongue / in the aleatory frame stream ofvaticides […].”

Thefourth full-length collection by Buffalo, New York “poet, critic and junkbookmaker” Joe Hall, following

Pigafetta Is My Wife

(Boston MA/ChicagoIL: Black Ocean, 2010),

The Devotional Poems

(Black Ocean, 2013) and

Someone’s Utopia

(Black Ocean, 2018) is Fugue and Strike: Poems by Joe Hall (BlackOcean, 2023). Fugue and Strike is constructed out of six poem-sections—“FromPeople Finder Buffalo,” “From Fugue & Strike,” “Garbage Strike,” “I HateThat You Died,” “The Wound” and “Polymer Meteor”—ranging from suites of shorterpoems to section-length single, extended lyrics. Hall’s poems are playful, savageand critical, composed as a book of lyric and archival fragments, cutting observations,testaments and testimonials. “[…] to become a poet / is to kill a poet,” hewrites, as part of the poem “FUGUE 6 | JACKED DADS OF CORNELL,” “cling to apoet / in the last hour, before slipping into the drift / atoms of talk bounce incylinders down Green St, predictive tongue / in the aleatory frame stream ofvaticides […].” Throughoutthe first section, Hall offers fifty pages of lyric lullabies and mantras towardsa clarity, writing of sleep and machines, fugues and their possibilities. “eachpoem / an easter egg,” he writes, as part of “FUGUE 40 | DEBT AFTER DEBT,” “w/absence inside and inside absence / you are hunger, breathing this time andvalue / particularized into mist, you are there, at the end / of another shift[…].” The second section, “Garbage Strike,” subtitled “BUFFALO & ITHICA,NY, USA / JAN-MAY 2019,” responds to, obviously, a worker’s strike that theauthor witnessed, and one examined through a collage of lyric and archivalmaterials from the time. Echoing numerous poets over the years that haveresponded to issues of labour—including Philadelphia poet ryan eckes, Winnipegpoet Colin Brown, Vancouver poet Rob Manery and the early KSW work poetsincluding Tom Wayman and Kate Braid—Hall’s explorations sit somewhere betweenthe straight line and the experimental lyric, attempting to articulate a kindof overview via the collage of lyric, prose and archival materials. There issomething of the public thinker to Hall’s work, one that attempts to betterunderstand the point at which capitalism meets social movements and action, allof which attempts to get to the root of how it is we should live responsibly inthe world. There’s some hefty contemplation that sits at the foundation of Hall’swriting. Or, as he writes near the end, to open “POLYMER METEOR”:

George Oppen wrote in “DiscreetSeries,” “Rooms outlast you.” Pithy. And also indicative of a relation to timethat is modest, sobering. We die, apartments go on. Their floors get scratchedby someone else’s chairs. Their vents fill with the dust of someone else’slife. But those rooms also go, demolished to make way for some other, pricierstructure. Or those rooms are split open to moisture and creatures seekingshelter in a zone of divestment. A frame of time in which things live decades tocenturies.

Throughnotes on the poem/section included at the back of the collection, Hall writesthat “In terms of the content of Garbage Strike, the researcher must now sweepup after the poet. Garbage Strike is meant to be suggestive; it grew from asmall archive of peoples’ insurgent imagination in relation to waste. It’s notthorough historical scholarship, and I remain a student of the subject.”Further on, his note ends:

As recent scholars like CharisseBurden-Stelly have persuasively theorized the operations of racial capitalismin the modern US context, new directions for the work open up. For instance, toseek more on-the-ground facts about these struggles and to understand theirrelation to the operations of racial capitalism through the contexts thosefacts provide. To learn to recognize how particular individuals and institutionstranslate the dynamics of racial capitalism into distributions of waste,hierarchies of labor, and extraction of profits—and the multifarious ways peopleget together and fight back.

April 25, 2023

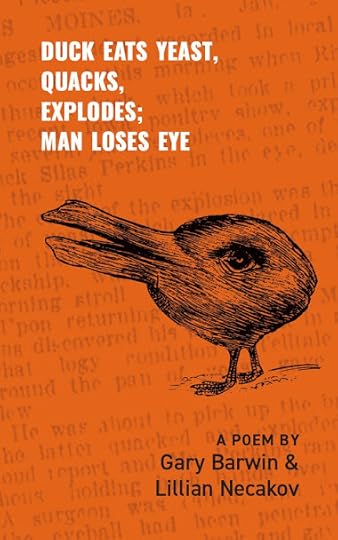

Gary Barwin and Lillian Nećakov, DUCK EATS YEAST, QUACKS, EXPLODES; MAN LOSES EYE: A Poem

1.

we fly but have not yetarrived

a suspended moment

the possible one

of the provinces of truth

it’s delightful

what you say, you say asa duck

you can say nothingoutside of this

let us now consider theother eye

Gary Barwin and Lillian Nećakov’s collaborative

DUCK EATS YEAST, QUACKS,EXPLODES; MAN LOSES EYE: A Poem

(Toronto ON: Guernica Editions, 2023), is aproject that takes its prompt from a story that ran through American newspapersacross January, 1910, about Des Moines, Iowa’s Silas Perkins, who was said tohave lost the sight in one eye after his prize-winning duck, Rhadamanthus(named for the wise demigod king of Crete from Greek mythology), ate a plate ofyeast and exploded (a check on Snopes suggests that this story might be apocryphal).Through one hundred and forty-four sequentially-numbered poem-sections, Hamiltonwriter, poet and composer Barwin and Toronto poet and editor Nećakov, friendswho first began to interact through a small group of self-declared surrealistpoets in Toronto during the 1980s, playfully pull and extend their narrative threadfrom that singular headline. They compose a collaborative riff of quickmovement and verbal gymnastics, akin to a variation on Fred Wah’s suggestion of“drunken tai chi,” allowing their individual writing skills to articulate whatis so clearly a gleefully-extended wordplay through and against dark humour,narrative expectation and strains of surrealism. This poem is very much a playfulexploration via a kind of ongoingness, working to see where the poem might gonext and how far, seemingly less concerned with where it might end up. “somethinghappened in Des Moines involving a duck,” part 11 writes, “some yeast, a man / hiseye // it’s still happening [.]” The poem exists in the present, allowing the storyof a century past remain as a kind of fixed point. Or, as they write, furtheron:

Gary Barwin and Lillian Nećakov’s collaborative

DUCK EATS YEAST, QUACKS,EXPLODES; MAN LOSES EYE: A Poem

(Toronto ON: Guernica Editions, 2023), is aproject that takes its prompt from a story that ran through American newspapersacross January, 1910, about Des Moines, Iowa’s Silas Perkins, who was said tohave lost the sight in one eye after his prize-winning duck, Rhadamanthus(named for the wise demigod king of Crete from Greek mythology), ate a plate ofyeast and exploded (a check on Snopes suggests that this story might be apocryphal).Through one hundred and forty-four sequentially-numbered poem-sections, Hamiltonwriter, poet and composer Barwin and Toronto poet and editor Nećakov, friendswho first began to interact through a small group of self-declared surrealistpoets in Toronto during the 1980s, playfully pull and extend their narrative threadfrom that singular headline. They compose a collaborative riff of quickmovement and verbal gymnastics, akin to a variation on Fred Wah’s suggestion of“drunken tai chi,” allowing their individual writing skills to articulate whatis so clearly a gleefully-extended wordplay through and against dark humour,narrative expectation and strains of surrealism. This poem is very much a playfulexploration via a kind of ongoingness, working to see where the poem might gonext and how far, seemingly less concerned with where it might end up. “somethinghappened in Des Moines involving a duck,” part 11 writes, “some yeast, a man / hiseye // it’s still happening [.]” The poem exists in the present, allowing the storyof a century past remain as a kind of fixed point. Or, as they write, furtheron:91.

we are always laughingwith

or for the dead

the burden livewires mustbear

the body begins tomultiply

a bag of laugh explosions

illuminate the wound

I’mfascinated with how Barwin has seemingly been working a multitude of simultaneousdirections over the past few years, from producing award-nominated novels tovisual poetry, musical composition, poetry collections [see my review of his latest here] and a slew of collaborative efforts, a thread in his work that hasreally ramped up over the past half-decade, including his full-lengthcollaboration with Gregory Betts, The Fabulous Op (Ireland: Beir BuaPress, 2022) [see my review of such here] and a second full-lengthcollaboration with Tom Prime, Bird Arsonist (Vancouver BC: New StarBooks, 2022) [see my review of such here], as well as multiple chapbook-lengthcollaborations with writers such as Amanda Earl and myself. How does he manageto keep track? jwcurry once offered that bpNichol was a great writer not purelybased on what he accomplished with his work, but that he was willing to fail,which provided such further possibilities in his writing, and this kind offearlessness is something that Barwin’s work employs as well. For her part, I’mless aware of Nećakov’s collaborative works [see my review of her latest collection here], although I know she’s worked a number of smaller,self-contained works for years, and a quick Google search provides that a further book-length collaboration she did with Scott Ferry and Lauren Scharhag,titled Midnight Glossolalia, appears later this year with Meat For Tea Press.

And,of course, the final poem in the collection does acknowledge their extended playon ongoingness, an echo of Robert Kroetsch’s poetics of perpetual delay,perhaps, or even the “say yes” structure of improv, offering: “to being andbegin and begin / in the middle of a sentence / after the final yes / ofyesness [.]” A few poems prior, number one hundred and thirty-seven, theywrite:

my grandfather’s town so small

if you said its name

as you walked in

you’d have walked out

before you’d finished

Mark Twain said

those who are inclined toworry

have the widest selectionin history

if the rich could hire

other people to die forthem

the poor could make

a wonderful living

April 24, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Michael Winkler

Michael Winkler is an Australian writer of fiction andnon-fiction. His journalism, short fiction, reviews and essays have been widelypublished and anthologised. His novel Grimmish – described by NobelLaureate JM Coetzee as ‘The strangest book you are likely to read this year’ –was shortlisted for the 2022 Miles Franklin Literary Award. Originallyself-published, Grimmish is now published by Puncher & Wattmann(Australia), Coach House Books (North America), Peninsula Press (UK) and MutatisMutandis (Spain, forthcoming).

Michael Winkler is an Australian writer of fiction andnon-fiction. His journalism, short fiction, reviews and essays have been widelypublished and anthologised. His novel Grimmish – described by NobelLaureate JM Coetzee as ‘The strangest book you are likely to read this year’ –was shortlisted for the 2022 Miles Franklin Literary Award. Originallyself-published, Grimmish is now published by Puncher & Wattmann(Australia), Coach House Books (North America), Peninsula Press (UK) and MutatisMutandis (Spain, forthcoming).Winkler wonthe 2016 Calibre Essay Prize for ‘The Great Red Whale’. More: michaelwinkler.com.au

1 - How did your first bookchange your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? Howdoes it feel different?

I always wanted to write books,but the books I’ve written have never been satisfying to me. I have written orco-written 10 books for commercial publishers, contributed to others andself-published three. My most recent book Grimmish is the only one I love.

2 - How did you come to fictionfirst, as opposed to, say, poetry or non-fiction?

I’ve written in every form. Imake the point in Grimmish that, while my short fiction is horrible, itisn’t remotely as bad as my poetry. But it’s all the one thing, whatever theform: me trying to tell you what I’m thinking or seeing or feeling.

3 - How long does it take tostart any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly,or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their finalshape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It embarrasses me, but I make acircus out of my writing. Tear my hair. Rend my clothing. Flop about like atrout on a riverbank. The complete Woe Is Me. I can spend actual years hatingmyself for not getting started. The whole thing is a very slow process, myfirst drafts are lousy, but I have some ability as a redrafter/rewriter.

4 - Where does a work of proseusually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combininginto a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the verybeginning?

It varies. But the first seedfor Grimmish was a story I read as a little kid. The final productincluded years of research, plenty of fragments knitted together, scraps of foundprose, plus a short story I rediscovered that I’d written 20 or more yearsearlier.

5 - Are public readings part ofor counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I take in information poorlythrough my ears, so I don’t get much joy from attending readings. It took me afew goes as a reader to realise that if you can provide a bit of a performance,a bit of verve, the audience is grateful.

6 - Do you have any theoreticalconcerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answerwith your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I don’t have any sort ofacademic background so I am easily baffled by anything that approaches theory.A preoccupation, however, is: what more can novels do to reward the reader?

7 – What do you see the currentrole of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do youthink the role of the writer should be?

Don’t think there’s a ‘should.’Writing a book that is fabulously entertaining is a social good, even if itdoesn’t solve the climate crisis or wealth inequality. But the writers who providethe most excitement for me, the ones who are mining and synthesising the worldas it is, are performing (exceeding) the roles of journalist, seer, philosopher,psychosocial analyst. If you want the news that matters, don’t turn on the TVor open the paper – go to a bookshop.

8 - Do you find the process ofworking with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Tricky question. With pastbooks I’ve worked with editors, and that has always been helpful. However, withGrimmish I knew precisely what I wanted and how far I wanted to push, soI was my own editor (and even my own proofreader, which is why the chapternumbers in the original edition are screwy). Editorial intervention would havecalmed and flattened the book – and thus removed its reason for existence. ButI value editors, and look forward to working with them again in the future.

9 - What is the best piece ofadvice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

My dad used to say, ‘It’seasier to cut down jungles than irrigate deserts’. I’m not sure if that’s trueeither literally or figuratively but I think of it often.

10 - How easy has it been foryou to move between genres (journalism to short fiction to essays to criticalprose to the novel)? What do you see as the appeal?

I’ve made my living throughwriting for decades, but I haven’t valued many of those jobs or much of thatwork. I wonder if my creative writing would be enhanced if I spent my paidhours doing something completely different. I think corporate writing and evenmainstream journalism can blunt your tools.

11 - What kind of writingroutine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day(for you) begin?

I have no writing routine. WishI did. I start every day by cursing the alarm clock, taking my pills andstepping out the back door to chat to my vegetables.

12 - When your writing getsstalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I get stalled for years at atime. And then, for no apparent reason, there will be a little dust-storm ofcreativity and I’ll wonder why it took so long and why I made it so hard. Idon’t think it helps with stalling, but certainly reading the writers who youmost admire can fuel your determination to do better, so I am always seekinggreat writing and rereading great writers. I’ve got a dodgy knee so I can’t goon long walks, but I think if I could that might be my answer.

13 - What fragrance reminds youof home?

My wife’s hair.

14 - David W. McFadden oncesaid that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influenceyour work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

A wonderful question, and yes –everything, really. I have written about finding the clues for how to write Grimmishthrough visual art, in particular the profane, poetic, prodigious mid-careerwork of painter Juan Davila. https://meanjin.com.au/essays/moving-on-u-p-p/

15 - What other writers orwritings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I grew up without a televisionin a little country town, so from the earliest age books have been asignificant part of my world. Even though I was passionate about literature, Ididn’t know any writers until Grimmish came out and I was invited tosome festivals and events. I think I expected grudging, competitive alphas –but with a couple of exceptions the writers I’ve met have been thoughtful,funny, good-hearted introverts. These relationships are buoying – as soon as Icomplete these answers I’ll drive a couple of hours up the road for a cuppawith one such writer. As for those whose work has a direct impact on my ownwork, the list is long. Melville is on top.

16 - What would you like to dothat you haven't yet done?

Almost everything.

17 - If you could pick anyother occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do youthink you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I would have liked to be aclown, or a professional wrestler, or a dancer – some occupation where you useyour body for storytelling and to bring joy. (Or I could steal from Francis Picabia who styled himself variously as funny guy,imbecile, pickpocket, failure, cannibal, silly willy and ‘the only completeartist’.)

18 - What made you write, asopposed to doing something else?

It’s all I can do! Believe me,it’s not the vocation I would have chosen. I would have liked to be a dancer ora singer, then my next choice would be painting or printmaking.

19 - What was the last greatbook you read? What was the last great film?

Book: Hmm. Genuine greatness israre. I read Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead over Christmas, and I thinkit’s truly great. I think For The Good Times by David Keenan which I’vejust finished is almost definitely great, but I need some time to ponder itbefore I can be certain.

Film: I no longer watch movies. I used to care, a lot, to thepoint of self-publishing the phenomenally low-selling (despite a supportivetweet from Rupaul) Fahfangoolah!:The despised and indispensable Welcome to Woop Woop, a book-length defenceof one of the most hated films in our national filmography. For a range ofreasons I no longer have any interest in that artform.

20 - What are you currentlyworking on?

Gluing together the fragmentsof a novel about a man who disengages from the community in a very specificway. Is it going well? Thank you for asking; indeed it is not. Onwards!

April 23, 2023

Sarah Blake, In Spring Time

12.

The bird spirit understandsthat her new form is more beautiful. Even

if it is less seen.

And she flies so easily. Minutesago she flew right under a bird of prey.

Hours ago she was abovethe clouds. The air was thin. The stars and

moon were close.

Her body has been singingto her from under the earth.

The song is sad, and whenshe sings, a whistling noise leaves her

torn stomach.

The mismatched notes ofher grieving body are the saddest of all.

Thethird poetry collection from American expatriate Sarah Blake, a poet andfiction writer currently living outside of London, England, is

In SpringTime

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2023), following on theheels of her

Mr. West

(Wesleyan University Press, 2015) [see my review of such here] and Let’s Not Live on Earth (Wesleyan University Press,2018) [see my review of such here]. In Spring Time is composed as a book-lengthsuite via a sequence of sixty numbered poems that loosely thread in, across andthrough the collection, grouped together across four numbered sections (“DAY 1,”“DAY 2,” “DAY 3” and “DAY 4”). Blake composes her meditative thread across ameandering of compressed time and the advent of spring, writing rebirth, renewaland death; she drifts across allegory and the specifics of foliage, wildanimals and even a horse. As part “31” offers: “She likes this. She likes you.She has no idea what she wants.”

Thethird poetry collection from American expatriate Sarah Blake, a poet andfiction writer currently living outside of London, England, is

In SpringTime

(Middletown CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2023), following on theheels of her

Mr. West

(Wesleyan University Press, 2015) [see my review of such here] and Let’s Not Live on Earth (Wesleyan University Press,2018) [see my review of such here]. In Spring Time is composed as a book-lengthsuite via a sequence of sixty numbered poems that loosely thread in, across andthrough the collection, grouped together across four numbered sections (“DAY 1,”“DAY 2,” “DAY 3” and “DAY 4”). Blake composes her meditative thread across ameandering of compressed time and the advent of spring, writing rebirth, renewaland death; she drifts across allegory and the specifics of foliage, wildanimals and even a horse. As part “31” offers: “She likes this. She likes you.She has no idea what she wants.”Offeringa poem that sits simultaneously within the body and the body of nature, Blake writesthe bounds of a season, following the details of movement and temporal space. “Who’sto say how far away the branches are?” she writes, as part of the poem “16.” in“DAY 2,” “Who’s to say how far / away the sky is? Who spends their time measuringdistances? // Is that an act of touching?” In Spring Time offers of andfrom spring, sketching moments through what appear as a kind of lyrical andphysical dream-state of horses, streams and daily meditations, attempting tofind her footing. As “20.” includes: “You’re glad the sun is going to spendtime every day shining on you. / This version of you that will outlast yourbody.”

April 22, 2023

Song & Dread, Otoniya J. Okot Bitek

My review of Otoniya J. Okot Bitek's

Song & Dread

(Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2023) is now up at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics.

My review of Otoniya J. Okot Bitek's

Song & Dread

(Vancouver BC: Talonbooks, 2023) is now up at periodicities: a journal of poetry and poetics.April 21, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Tawanda Mulalu

Tawanda Mulalu [photo credit: Joseph Lee] was born in Gaborone, Botswana, in 1997. His first book,

Please make me pretty, I don’t want to die

, was selected by Susan Stewart for the Princeton Series of Contemporary Poets and is listed as a best poetry book of 2022 by The Boston Globe, The New York Times and The Washington Post. His chapbook Nearness was chosen as the winner of The New Delta Review 2020-21 Chapbook Contest, judged by Brandon Shimoda. Tawanda’s poems appear or are forthcoming in Brittle Paper, Lana Turner, Lolwe, The New England Review, The Paris Review, A Public Space and elsewhere. His writing has been supported by Brooklyn Poets, the Community of Writers, the New York State Summer Writers Institute and Tin House Books. Tawanda has also served as a Ledecky Fellow for Harvard Magazine and as the first Diversity and Inclusion Chair of The Harvard Advocate. He was recently awarded The Denver Quarterly’s 2022 Bin Ramke Prize for Poetry.

Tawanda Mulalu [photo credit: Joseph Lee] was born in Gaborone, Botswana, in 1997. His first book,

Please make me pretty, I don’t want to die

, was selected by Susan Stewart for the Princeton Series of Contemporary Poets and is listed as a best poetry book of 2022 by The Boston Globe, The New York Times and The Washington Post. His chapbook Nearness was chosen as the winner of The New Delta Review 2020-21 Chapbook Contest, judged by Brandon Shimoda. Tawanda’s poems appear or are forthcoming in Brittle Paper, Lana Turner, Lolwe, The New England Review, The Paris Review, A Public Space and elsewhere. His writing has been supported by Brooklyn Poets, the Community of Writers, the New York State Summer Writers Institute and Tin House Books. Tawanda has also served as a Ledecky Fellow for Harvard Magazine and as the first Diversity and Inclusion Chair of The Harvard Advocate. He was recently awarded The Denver Quarterly’s 2022 Bin Ramke Prize for Poetry. 1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

Hmm. It hasn't actually changed much about my day-to-day life. I still have to labor and breathe and stuff. I feel marginally more confident in my ability to get published, but I don't actually feel more confident in my ability to write (actually, a little more horrified: I keep thinking of the poets I admire and what they did for their second book and, often, the jump in quality of writing from first to second book for those folks is absurdly large…) It's changed a few things socially. For my friends who believed I could be a writer, it was simple confirmation—which warms my heart, because I didn't feel that great about the whole endeavor (even though it was a dream of mine to get this thing out there). Those same friends say nice things about me at parties when I go with them, so I get cute introductions to new people (which is kind of helpful in New York for all sorts of reasons, both good and bad).

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I used to write a lot of personal essays, particularly in college. They were all hyper lyrical and suffered from a lack of cohesion and scattered, imagistic narratives. Eventually I gave up on being able to write something extended that could make 'sense' in the way that fiction and non-fiction tend to. So I ended up committing to the thing that made my brain feel safest. Poetry was, is, really good for the way I think: which tends to be deeply affective, wildly associative, etc. It's the only place where I don't have to feel ashamed for not having my thoughts altogether—and often, not having my thoughts altogether makes the poems more interesting (though the editing thereafter becomes a nightmare…) I’m suddenly worrying now because I’m remembering the much-quoted Auden phrase, “Poetry might be defined as the clear expression of mixed feelings.” Maybe let’s all focus on the “might be” part.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Honestly, I don't know. This is my first real (finished?) writing project. I wrote this book from a place of extended depression. A lot of it feels like it sort of just happened to (with?) me. I think, in writing terms, the book came relatively quickly (the first poems are from the fall of 2019, the last poems are from the summer of 2021). I have a strong feeling that the next project that I'd like to write will be long and torturous—which is fine. Totally fine. Genuinely fine. Yeah.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

I don't want it to be like this moving forward, but for this project anyways, the poems tended to come to me from places of feelings that weren't fun (pandemic depression, seasonal affective disorder, pretty-normal-in-retrospect heartbreak, persistent fears of racialized harm, diasporic longing, etc, etc—) I often wrote in a way that's kind of like listening to music when you need a pick-me-up. I was also fairly desperate—given my overly-large imaginations of the various failures I had accumulated during my time at Harvard—to write something to prove to myself that I could matter in some way (an insipid motivation for art, obviously). Some of the poems in the book are "project poems" that I wrote for the sake of filling in perceived gaps in the book (this is particularly true of 'Frenzy' which was basically an attempt to justify having the cover of the book as the cover of the book). For now, I have an idea for a second collection that involves writing several poems that sound like arias (even more so than in this one). We'll see how that actually ends up going. I’m pretty optimistic about it to be honest.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Not really? I read some of my poems to my friends sometimes when I was tipsy at parties or cuddling on a bed with them or whatever—all those things ended up being strangely helpful because I trust(ed) them. Also, reading poems out loud in writing workshops is also a little helpful because you get a sense of when the music is actually doing what you wanted it to do (or something worse, or something better). But mostly I read out loud to myself. I read out loud to myself a lot while writing the first book, and often did so when I wasn't feeling very happy in the vain (very vain) hope that the poems would somehow inevitably make me feel better. Which sometimes worked. Sometimes. Those were lucky moments that made me believe in the poems a lot more than was likely warranted (but I wouldn't have it any other way, really).

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I really need to get over Sylvia Plath but I have absolutely no intention of doing that anytime soon.

(I worry, like everyone else, that I'm not good enough. I mean, there shouldn't be a 'good enough' aspect of writing poetry in terms of the desire to write poetry. But I care a lot about writing something that outlives me. Not even for the sake of being remembered or whatever (that's what love and family and friendship is for). Mostly, I care about having poems outlive me because I think poems are beautiful and I want to be good enough to honor that beauty (also a little insipid, but, in this case: why not be? It's a maudlin, flowery, sentimental and astonishing art.))

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I have no idea, sorry. I want to believe that poetry matters more than, I don't know, economics. It feels like that to me. But I don't have a good, universal theory regarding the importance of being a writer (tried that—failed horribly, got depressed again). I suppose we could acquiesce to pleasure: the idea that writing, like any other art form, when received or produced invokes pleasure, and that that pleasure is its own justification for writing. I actually don't believe that, and have always modestly resented that argument (yes, yes, pleasure need not be trivial, but the word itself sounds a little trivial, no?).

I guess I want writing and reading to feel more significant than whether or not it invokes strong feelings in me—even if that contradicts the fact that I do this precisely because it invokes strong feelings in me (and, hopefully, others). The best theory I have, at least for poetry, is that it feels like the closest representation of what it's like being a person, of what it's like being a mind in this world that I know and can personally understand (to the extent that poetry can be 'understood'). I think it's important to understand what it's like being a person because we have to live with ourselves and with each other. We can't escape our minds, the feelings within ourselves and others that our minds and other minds provoke. And, since we can't escape that, we should at least pay a great kindness and respect to the fact of our experiences. Poetry is a way of honoring each other, even if that honoring is so absurdly and blatantly materially useless.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Please edit my work, please please please. I love it when I submit stuff to journals and editors suggest I cut lines or re-arrange something or fix a poem in any way. shape or form that they desire. For one thing, if I don't like the advice, I can just ignore it and the work typically ends up getting published anyways. But—and here's the cool part—edit suggestions teach you how to read a poem even if you disagree with them. It's really fun seeing where other people's minds receive or reject ways that you wrote the lines of a poem. And it can also teach you how to read the poem, surprisingly, in its own terms, separately from how you thought you knew how to read it as the ‘original’ author. This is because you end up wondering to yourself: Why did I want to 'fix' the poem a certain way? What is the poem trying to do that is making my mind warrant that kind of intervention? Etc, etc.

I struggled a little because I was so used to taking edit suggestions from classmates and poetry professors and so on (I accepted, about, maybe half of whatever I got and revised my poems accordingly) But the editor for the series my book was published in, Susan Stewart, gave me, like, five edit suggestions and said "do what you want ,it's your book" which made me freak out for about two-plus months. I'm honestly not sure that anyone below the age of 30 should be allowed to publish a poem without editorial intervention (I'm obviously being facetious, and 30 is an arbitrary cut-off age…I'm just admitting to my own anxieties given that so many of my favorite poems that I've read recently have been written in a kind of "late" style that you basically only acquire after having been doing this for decades. I don't think it's me being too self-effacing to say that I trust that kind of learned beauty more than whatever it is that I end up cooking because I felt sad in college. Though, obvious counter-example: Rimbaud).

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Don't laugh, but, genuinely, every time Naruto said "Believe it!", both in the manga and anime, he kept me going even up to my early twenties. I say this completely unironically. Perfect anxiety antidote.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I don't have a writing routine. Right now, a typical day begins with an alarm ringing "Wake-up!" and my body saying "No".

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

Music. Always music.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

I don't know. I didn't even know I didn't know. I haven't been home in three years.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Music. Always music.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

Sylvia Plath. Morgan Parker. T.S Eliot. F. Scott Fitzgerald. Robert Hayden. Okot p'Bitek. Chinua Achebe. Ngugi wa Thiong'o. Josh Bell. Jorie Graham. Jay Deshpande. Sharon Olds. Haruki Murakami. Vamika Sinha. Isabel Duarte-Grey. Emma de Lisle. Darius Atefat-Peckham. . Earl Sweatshirt. Childish Gambino. Kanye West. Adrianne Lenker. Robin Pecknold. Haolun Xu. Others more. Others more to come.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

A good long poem.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

I wanted to be a theoretical physicist, but I failed at that. For the past year-and-a-half, I had been working as an investment researcher, which I wasn’t super good at either (I’ve recently resigned). I kind of wanted to try being a clinical psychologist at some point—but maybe later in my life? I was good at teaching, I could maybe try that again. Actually, no: I'd sing. If I could sing, I'd sing. Like in the Dorothea Lasky poem, 'Me and the Otters':

There is no poem that will bring back the dead17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

There is no poem that I could ever say that will

Arise the dead in their slumber, their faces gone

There is no poem or song I could sing to you

That would make me seem more beautiful

If there were such songs I would sing them

O they would hear me singing from here until dawn

At first, it was because I wanted to be smart. Then it was because I didn't really have much else going on (of course I did, we always do. People love us. We love them back.)

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

The Way of the Earth by Matthew Shenoda (still reading). Aftersun, directed by Charlotte Wells.

19 - What are you currently working on?

There's people I need to talk to.

April 20, 2023

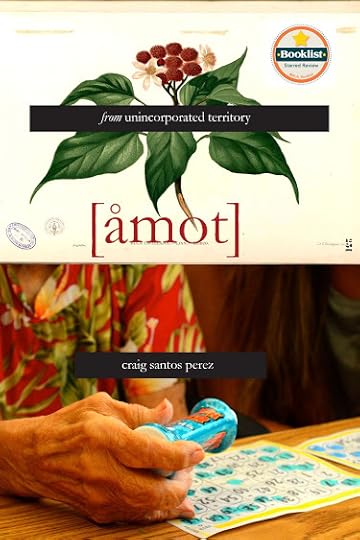

Craig Santos Perez, [åmot]

bingo is not indigenousto guam

yet here [we] are

in the air-conditionedcommunity center

next to the villagecatholic church

i help set the bingocards

& ink daubers on thecafeteria table

you sit in a wheelchair

like an ancient seaturtle

this has been your dailyritual

but the last time playedbingo with you

was 25 years ago when iwas a teenager

& still lived onisland

hasso’ when you won younever shouted

“bingo” too boastfully

when you lost you simplysaid

“agupa’ tomorrow we’llbe lucky”

here no onepunishes you

for speaking chamoru

here no warinvades & occupies life

no soldiers force you tobow (“ginen achiote”)

PoetCraig Santos Perez continues to expand his great long poem documenting, examiningand declaring his home territory through

from unincorporated territory [åmot]

(Berkeley CA: Omnidawn Publishing, 2023), the fifth book in his sequence both setas accumulation and ongoing thread, following

from unincorporated territory [hacha]

(Kaneohe HI: TinFish Press, 2008; updated edition, Omnidawn, 2017),

from unincorporated territory [saina]

(Omnidawn, 2010),

from unincorporated territory [guma’]

(Omnidawn, 2014) and

from unincorporated territory [lukao]

(Omnidawn, 2017). He is also the author of

Habitat Threshold

(Omnidawn,2020), although I haven’t seen that title, so I’m unaware how that book mightfit in the larger structure, if at all. As he described the larger project backin 2014 as part of his ’12 or 20 questions’ interview: “My first book was thefirst book-length excerpt of an ongoing story about my identity, culture, andfamily in the context of the history, politics, and ecology of my home(is)land,Guahan (Guam). My newest book is the third installment of the series, and itssubject matter focuses more directly on migration and militarization. In form,the newest book explores the poem-essay and the conceptual-collage poem.”

PoetCraig Santos Perez continues to expand his great long poem documenting, examiningand declaring his home territory through

from unincorporated territory [åmot]

(Berkeley CA: Omnidawn Publishing, 2023), the fifth book in his sequence both setas accumulation and ongoing thread, following

from unincorporated territory [hacha]

(Kaneohe HI: TinFish Press, 2008; updated edition, Omnidawn, 2017),

from unincorporated territory [saina]

(Omnidawn, 2010),

from unincorporated territory [guma’]

(Omnidawn, 2014) and

from unincorporated territory [lukao]

(Omnidawn, 2017). He is also the author of

Habitat Threshold

(Omnidawn,2020), although I haven’t seen that title, so I’m unaware how that book mightfit in the larger structure, if at all. As he described the larger project backin 2014 as part of his ’12 or 20 questions’ interview: “My first book was thefirst book-length excerpt of an ongoing story about my identity, culture, andfamily in the context of the history, politics, and ecology of my home(is)land,Guahan (Guam). My newest book is the third installment of the series, and itssubject matter focuses more directly on migration and militarization. In form,the newest book explores the poem-essay and the conceptual-collage poem.”Anindigenous Chamoru from the Pacific Island of Guåhan (Guam) currently livingand teaching in Mānoa, Hawai‘i, unincorporated territory explores home,colonialism, ecological concerns and family, and where the indigenous culturemeets colonial influence, set in a geography that still holds in living memorythe stories of occupation by the Spanish, the Americans and the Japanese. An unincorporatedterritory of the United States, Guam is, much like Puerto Rico, politicallydisenfranchised, and unable to participate in the United States presidentialelections. How can a body, and a population, still be held and yet have no say?“today the military invites [us] / to collect plants & trees / within areasof litekyan / slated to be cleared / for a firing range,” he writes, early onin the collection. The poem continues, a bit further: “if [we] receive theirpermission / they’ll escort [us] to mark & claim / trees [we] wantdelivered / after removal // they call this ‘benevolence’ /// yet why / does itfeel / like a cruel / reaping [.]”

ginen during yourlifetime

for guam’s “greatestgeneration”

~

you survived

violent occupation

& the bloody march

to manenggon

you endured

the wounds of

our island stitched

by barbed wire fences

you said goodbye

to your children

as they donned uniforms

& deployed overseas

you prayed

as cancer diseased

half our relatives

you listened

as english endangered

i fino’ chamoru

& snakes silenced

native birds

o saina

i doubt if [we]

will ever receive

true reparations

or sovereignty over

our own nation

i can’t count

how many more

body bags will arrive

with touch boxes

& folded flags

i don’t know if

all your children

grandchildren

great-grandchildren

&great-great-grandchildren

will ever return

guma’

during your lifetime

to show

the abundance

that you

will be

survived by

Asa note from the publisher offers as part of the colophon: “‘Åmot’ is theChamoru word for ‘medicine,’ and commonly refers to medicinal plants.Traditional healers were know as yo’åmte, and they gathered åmot in the jungle,and recited chants and invocations of taotao’mona, or ancestral spirits, in thehealing process. Through experimental and visual poetry, Perez explores howstorytelling can become a symbolic form of åmot, offering healing from thetraumas of colonialism, militarism, migration, environmental injustice, and thedeath of elders [.]” The structure of Perez’s ongoing long poem feelscomparable to the late bpNichol’s nine-volume The Martyrology, or evenRobert Kroetsch’s “Field Notes,” both set as umbrella projects constructedthrough accumulated book-length structures, offering each volume as a furtherbrick, a further room, of something far larger and complex. Comparable, too, toPerez is how everything that Nichol and Kroetsch wrote fell into the larger structureof their ongoing projects, except, of course, for those projects that weredeliberately set beyond those particular boundaries. A rich and expansivecollection of fragments, fractals, family stories and archival material, fromunincorporated territory [åmot] holds elegies for the past and presentaround a land and people still in flux; of occupation and mourning, loss andfamily, flora and fauna, documenting the visual literacies of an island and itspeople, examining what erodes and what holds, and what might already be lost. Or,as he writes towards the end of the collection:

remember our people

scattered like stars

form new constellations

when [we] gather

hasso’ home is not simply a house

village or island

home is anarchipelago of belonging