Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 91

May 19, 2023

Marie-Andrée Gill, Heating the Outdoors, translated by Kristen Renee Miller

Sometimes I close my eyesand pretend I’m there:

You flip the choke, yankthe cord, and we take off in a black cloud. With this much snow, we can’t breakdown; I’m not even wearing a coverall. I’m enveloped by something like thatsaying, everything in its own place. You steer through trees in thedark, turn on a dime. Branches in my face, flakes in my eyes—with you I’d neverget stranded.

It would make a goodtitle for something, I tell myself: Dances with ski-doos. (“LIKE NOTHINGEVER HAPPENED”)

Itis curious to realize that I know the name of Montreal-based Ilnu Nation member Marie-Andrée Gill through the review Jérôme Melançon did over at periodicities:a journal of poetry and poetics of

Chauffer le dehors

(La Peuplade, 2019).That same collection, her third to be published in the original French, has nowappeared in English translation via translator Kristen Renee Miller, publishedas

Heating the Outdoors

(Toronto ON: Book*hug, 2023) as part of Book*hug’s“Literature in Translation” series. The back cover offers that Heating theOutdoors “describes the yearnings for love, the domestic monotony ofpost-breakup malaise, and the awkward meeting of exes. As the lines betweeninterior and exterior begin to blur, Gill’s poems, here translated by KristenRenee Miller, become a record of the daily rituals of ancient landscapes thatinform her identity not only as a lover, then ex, but also as an Ilnu and Québécoisewoman.” Composed into clusters of sketched-out fragments that feel composed inreal time, Gill’s book-length lyric is structured in a quartet of lyric suites,threads of accumulating sections: “LIKE NOTHING EVER HAPPENED,” “SOLFÈGE OFSTORMS,” “THE RIOT STARTS WITHIN” and “THE FUTURE SHRUGS.” “On a bed of firsaplings,” she writes, near the end of the second section, “we touched thatmute, ephemeral / beauty. We stumbled out, uncertain, searching for the edible/ root of language, nursing our dazzling wounds. Together we / drove a streetsweeper over our ghosts. // In any case, we knew what to do with our bodiesbetween / thunderstorms.” Gill writes a sequence of meditative sketches on the wildsof domestic matters and domestic matter into clusters of lyric propulsion,moments captured in turned light, and the intimacy of each small moment,contained and collected, simultaneously holds an infinite space. “Still writingto survive,” she offers, in the first section, “I make to-do lists, interpretfading / images from good dreams: fried onions and hot soups, / chanterellesand apple tarts, our accidents of simple / happiness.”

Itis curious to realize that I know the name of Montreal-based Ilnu Nation member Marie-Andrée Gill through the review Jérôme Melançon did over at periodicities:a journal of poetry and poetics of

Chauffer le dehors

(La Peuplade, 2019).That same collection, her third to be published in the original French, has nowappeared in English translation via translator Kristen Renee Miller, publishedas

Heating the Outdoors

(Toronto ON: Book*hug, 2023) as part of Book*hug’s“Literature in Translation” series. The back cover offers that Heating theOutdoors “describes the yearnings for love, the domestic monotony ofpost-breakup malaise, and the awkward meeting of exes. As the lines betweeninterior and exterior begin to blur, Gill’s poems, here translated by KristenRenee Miller, become a record of the daily rituals of ancient landscapes thatinform her identity not only as a lover, then ex, but also as an Ilnu and Québécoisewoman.” Composed into clusters of sketched-out fragments that feel composed inreal time, Gill’s book-length lyric is structured in a quartet of lyric suites,threads of accumulating sections: “LIKE NOTHING EVER HAPPENED,” “SOLFÈGE OFSTORMS,” “THE RIOT STARTS WITHIN” and “THE FUTURE SHRUGS.” “On a bed of firsaplings,” she writes, near the end of the second section, “we touched thatmute, ephemeral / beauty. We stumbled out, uncertain, searching for the edible/ root of language, nursing our dazzling wounds. Together we / drove a streetsweeper over our ghosts. // In any case, we knew what to do with our bodiesbetween / thunderstorms.” Gill writes a sequence of meditative sketches on the wildsof domestic matters and domestic matter into clusters of lyric propulsion,moments captured in turned light, and the intimacy of each small moment,contained and collected, simultaneously holds an infinite space. “Still writingto survive,” she offers, in the first section, “I make to-do lists, interpretfading / images from good dreams: fried onions and hot soups, / chanterellesand apple tarts, our accidents of simple / happiness.”

May 18, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jake Byrne

Jake Byrne is a writer based in Tka:ronto, ckaToronto. Their first book of poems, Celebrate Pride with Lockheed Martin,is available now from Wolsak & Wynn's Buckrider Books imprint. DADDYis forthcoming with Brick Books in 2024. Find them at @jakebyrnewritessomewhere on the Internet.

1 - How did yourfirst book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recent work compareto your previous? How does it feel different?

My first chapbook didn’t change mylife very much – well, it did, but in the normal way that time changes thingsfor you. It was nice to get a nod from the bp Nichol shortlist, but I would saymy life quickly returned to what it had been previously.

Things feel a little different forthis book – but I’ve felt ‘career momentum’ before that went nowhere, so I’mnot going to count any chickens prior to hatching. All I will say is that itfeels nice to feel so supported as I get to accomplish a dream I’ve had sincechildhood.

2 - How did you cometo poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

Horrific attention span. Poetryinvolves the types and durations of concentration I am naturally suitedtowards. It also is still a lot of fun. Writing prose has always felt laborious.

3 - How long does ittake to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially comequickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to theirfinal shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

It takes seconds to start anyparticular writing project, and just as long to abandon them. Some poems comefully-formed, quickly: those are the bolt-of-lightning poems. Then there areones that are formed over months, years, often with little active work, just mymind slowly composting an idea or image until one day it coalesces. These arethe long poems I tend to end my books with.

4 - Where does apoem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end upcombining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" fromthe very beginning?

I have no idea of telling where onebook ends and another begins, other than they tend to have different ‘feels’ tothem. Many of the poems in Celebrate Pride with Lockheed Martin werewritten at the same time as poems from DADDY, for example, but tome, there’s no way of mistaking one for the other.

5 - Are publicreadings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort ofwriter who enjoys doing readings?

I enjoy readings, as a poet I think you must MUST be down to hang out.Novelists are the industrious introverts of the literary world – for poets, allwe have are our communities.

6 - Do you have anytheoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are youtrying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questionsare?

I guess, ultimately, I am only trying to answer one theoretical question,which is the question of theodicy: why does suffering exist? If God exists,why does God permit suffering and evil?

I guess I’m just kind of culturally Catholic that way.

On the level of technique, prosody trumps all other considerations forme, 99.9% of the time.

My poetics derives from sound, not from image. All considerations such aslogic, fact, or whether a word is ‘best’ or not will be overturned in favour ofa syllabic pattern that sounds ‘right’ to me.

The other things I am interested in are primarily the art of artifice andits corollary, sincerity and vulnerability, or the appearance thereof, and Ihave some very minor concrete leanings in that I prefer to think of the whole page,including its white space, as my canvas. You may continue to expect some weirdgrammatical and formatting stuff from me in the future.

7 – What do you seethe current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one?What do you think the role of the writer should be?

I think the role of a writer, or the role of any artist, is to bothattempt to describe and reshape the reality you live in, and to encourageothers to have the courage to do the same. It takes a great deal of courage tolive honestly.

8 - Do you find theprocess of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Essential. I consider myself a sharper editor than a writer and alwayshave. It would be hypocritical of me to respect the process when I’m on one endof it but not the other.

9 - What is the bestpiece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

This is not a piece of advice I’ve heard, but rather one I’ve witnessedand observed: in a small industry mostly consisting of friends passing the same$500 back and forth between each other, the relationships you form are everything.Kindness and collaboration provide better returns than competition.

10 - What kind ofwriting routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does atypical day (for you) begin?

I have no fixed writing routine. Myonly rule is that when I hear the call, I write it down, no matter how horribleor artless it seems in the moment.

I have long fallow periods, sometimes up to eighteen months, where Ibarely write at all. But the urge comes back, it always does, and then I maketime for my notebook.

11 - When yourwriting gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a betterword) inspiration?

I’ve gone through enough of these cycles that I no longer worry aboutthis or attempt to force it.

I redirect attention to my life and try to live it, and after a few weeksor months of that the poems start flowing again.

12 - What fragrancereminds you of home?

I grew up in a fragrance-free household, for the most part.

I guess certain soaps and cleaning products, or maybe the ginger cookiesmy mom made for us in the fall in the nineties.

I wear a lot of scents myself now in adulthood, so I still don’t have afixed ‘home’ aroma!

13 - David W.McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other formsthat influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

I’m only a poet because I couldn’t cut it as an actor, novelist,rockstar, playwright, director, or painter.

14 - What otherwriters or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside ofyour work?

Everything is grist for the mill,but I’ve always been someone interested in responding to the art of others, andthat includes

15 - What would youlike to do that you haven't yet done?

16 - If you couldpick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, whatdo you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

17 - What made youwrite, as opposed to doing something else?

The path of least resistance.Bookworm child, author adult. Oh and the fact I had a really really powerfulexperience of being the day I wrote my first word, which is probably the mostvivid memory I have from my early life.

18 - What was thelast great book you read? What was the last great film?

Great book? A Queen in BucksCounty by Kay Gabriel.

Great film? I’ve been having one of my little obsessions about DavidLynch’s Inland Empire, and have watched it about thirty times sinceNovember of 2022. One day I will simply grow tired of it and never watch itagain.

19 - What are youcurrently working on?

Surviving my debut book tour. I have three to four book ideas ready to gobut I think I’m going to need a period of rest and recovery before I can startthinking about those.

May 17, 2023

the ottawa small press book fair, spring 2023 edition: June 17, 2023

span-o (the small press action network - ottawa) presents:

the ottawa

small press

book fair

spring 2023

will be held on Saturday, June 17, 2023 in room 203 of the Jack Purcell Community Centre (on Elgin, at 320 Jack Purcell Lane).

“once upon a time, way way back in October 1994, rob mclennan and James Spyker invented a two-day event called the ottawa small press book fair, and held the first one at the National Archives of Canada...” Spyker moved to Toronto soon after our original event, but the fair continues, thanks in part to the help of generous volunteers, various writers and publishers, and the public for coming out to participate with alla their love and their dollars.

General info:

the ottawa small press book fair

noon to 5pm (opens at 11:00 for exhibitors)

admission free to the public.

$25 for exhibitors, full tables

$12.50 for half-tables

(payable to rob mclennan, c/o 2423 Alta Vista Drive, Ottawa ON K1H 7M9; paypal options also available

Note: for the sake of increased demand, we are now offering half tables.

To be included in the exhibitor catalog: please include name of press, address, email, web address, contact person, type of publications, list of publications (with price), if submissions are being considered and any other pertinent info, including upcoming ottawa-area events (if any). Be sure to send by June 7th if you would like to appear in the exhibitor catalogue.

And hopefully we can still do the pre-fair reading as well! details TBA

BE AWARE: given that the spring 2013 was the first to reach capacity (forcing me to say no to at least half a dozen exhibitors), the fair can’t (unfortunately) fit everyone who wishes to participate. The fair is roughly first-come, first-served, although preference will be given to small publishers over self-published authors (being a “small press fair,” after all).

The fair usually contains exhibitors with poetry books, novels, cookbooks, posters, t-shirts, graphic novels, comic books, magazines, scraps of paper, gum-ball machines with poems, 2x4s with text, etc, including regular appearances by publishers including above/ground press, Bywords.ca , Room 302 Books, Textualis Press, Arc Poetry Magazine , Canthius , The Ottawa Arts Review , The Grunge Papers, Apt. 9, Desert Pets Press, In/Words magazine & press, knife | fork | book, Ottawa Press Gang, Proper Tales Press, 40-Watt Spotlight, Puddles of Sky Press, Invisible Publishing, shreeking violet press, Touch the Donkey , Phafours Press, etc etc etc.

The ottawa small press fair is held twice a year (apart from these pandemic silences), and was founded in 1994 by rob mclennan and James Spyker. Organized/hosted since by rob mclennan.

Come on by and see some of the best of the small press from Ottawa and beyond!

Free things can be mailed for fair distribution to the same address. Unfortunately, we are unable to sell things for publishers who aren’t able to make the event.

Also: please let me know if you are able/willing to poster, move tables or distribute fliers for the event. The more people we all tell, the better the fair!

Contact: rob mclennan at rob_mclennan (at) hotmail.com for questions, or to sign up for a table

May 16, 2023

Meghan Kemp-Gee, The Animal in the Room

OFFICE HOURS

They say, I want to knowhow to do better. I am applying to medical school next year, so I need to makesure I have perfect grades. I was wondering, they say, if we could go over thenext essay assignment. I know this paragraph doesn’t make sense. I don’t knowwhat point I’m trying to make. I ask them, What are you really trying to say? Theysay, I am still adjusting to my medication. They say, Last week I went to theemergency room. Do you know what a panic attack is? I tell them that I think I do.They say, I feel like I have to choose between feeling stupid and feelingscared all the time. I say, I feel like we can figure out this paragraph. I’llask you some more questions and then we’ll figure out what you were trying tosay.

Thereare some interesting formal shifts in poet Meghan Kemp-Gee’s full-length poetrydebut,

The Animal in the Room

(Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2023). Thereis something in the way she works her lyric narratives from line-breaks toprose poems, attempting to feel out her own sense of formal opportunity, syntaxand shape. “Through her syntax and diction,” she writes, to open the prose poem“THE THESIS SENTENCE,” “the author explores her main theme in a clear andeffective way. Through the use of rhetorical devices including metaphor andrepetition, the writer emphasizes her argument. Throughout this poem, themeaning is reflected by the form in several ways. In this text, the author hassome questions and she asks them using various rhetorical techniques andnarrative strategies.” Throughout The Animal in the Room, there arepoems that sparkle with inventiveness and wit, as she composes a bestiary ofsentences and syntax. Each of her animals, as well as her sentences, retaintheir wildnesses, even while set up against a particular element of constraintor restraint. Kemp-Gee’s structures do seem exploratory, as she attends and examinesher lyric with a careful deliberateness, one that can’t easily be situated. Holdinga back cover quote by poet Sue Sinclair suggests a particular lyric formalitythat Kemp-Gee’s poems might include as a strain, but her overall experimentationseventually contradict, as the pieces here are more interested in structuraldifferences and staggerings of syntax than any specific adherence to narrativeform. Instead, her formal engagements, specifically through the prose poemsthat tether the collection together across a variety of forms, hold shades of thework of Rosmarie Waldrop, Anne Carson or even Lydia Davis:

Thereare some interesting formal shifts in poet Meghan Kemp-Gee’s full-length poetrydebut,

The Animal in the Room

(Toronto ON: Coach House Books, 2023). Thereis something in the way she works her lyric narratives from line-breaks toprose poems, attempting to feel out her own sense of formal opportunity, syntaxand shape. “Through her syntax and diction,” she writes, to open the prose poem“THE THESIS SENTENCE,” “the author explores her main theme in a clear andeffective way. Through the use of rhetorical devices including metaphor andrepetition, the writer emphasizes her argument. Throughout this poem, themeaning is reflected by the form in several ways. In this text, the author hassome questions and she asks them using various rhetorical techniques andnarrative strategies.” Throughout The Animal in the Room, there arepoems that sparkle with inventiveness and wit, as she composes a bestiary ofsentences and syntax. Each of her animals, as well as her sentences, retaintheir wildnesses, even while set up against a particular element of constraintor restraint. Kemp-Gee’s structures do seem exploratory, as she attends and examinesher lyric with a careful deliberateness, one that can’t easily be situated. Holdinga back cover quote by poet Sue Sinclair suggests a particular lyric formalitythat Kemp-Gee’s poems might include as a strain, but her overall experimentationseventually contradict, as the pieces here are more interested in structuraldifferences and staggerings of syntax than any specific adherence to narrativeform. Instead, her formal engagements, specifically through the prose poemsthat tether the collection together across a variety of forms, hold shades of thework of Rosmarie Waldrop, Anne Carson or even Lydia Davis:TEACHING COMPOSITION

I compare a satisfying sentenceto the feeling of kicking somebody as hard as you can, square in the chest. Thekid in the back row asks, Have you actually done that?

Thisis very much a book of structures, of sentences; writing of animals and dreams,and the dreams of animals: the brontosaurus, the giant pacific octopus, theVancouver Island marmoset and the Greenland shark, among others. “I have aquestion / for the ticks who dream / about being wolves. / My question concerns/ orchids and the end / of the world,” she writes, to open the poem “THE BLOODSUCKER,”“concerns / the colour blue and /rare diseases.” This book suggests someremarkable things are still to come from Meghan Kemp-Gee; I, for one, am verymuch looking forward to seeing what she does next.

May 15, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Marta Balcewicz

Marta Balcewicz

is the author of the novel

BigShadow

(Book*hug Press, 2023). Her work has appeared in Catapult, TinHouse online, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, Washington Square Review, TheRumpus, and Passages North amongst other publications. Her fictionwas anthologized in

Tiny Crimes

(Catapult, 2018). She received afellowship from Tin House Workshops in 2022. She spent her early childhood inPomerania and Madrid, and now lives in Toronto.

Marta Balcewicz

is the author of the novel

BigShadow

(Book*hug Press, 2023). Her work has appeared in Catapult, TinHouse online, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, Washington Square Review, TheRumpus, and Passages North amongst other publications. Her fictionwas anthologized in

Tiny Crimes

(Catapult, 2018). She received afellowship from Tin House Workshops in 2022. She spent her early childhood inPomerania and Madrid, and now lives in Toronto.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your mostrecent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book will be coming out in a few weeks, so it’s too early toassess its effect on my life. Having it be complete, though, feels nicelyfreeing, in the sense that I feel free to move on to my next book in anundistracted and relatively confident manner.

2 - How did you come to fiction first, as opposed to, say, poetry ornon-fiction?

I remember always writing stories, but also poems, and also articlesfor magazines I made for my mother and letters to relatives galore. I probablycame to all these forms more or less simultaneously, and I still like allthree, though I like fiction the most. It feels the most like a vast blankcanvas on which I can do anything I want in an unconstrained way.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project?Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do firstdrafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out ofcopious notes?

I think I suffer from all the common modes of procrastination such asbeing convinced there is a certain amount of research I need to do beforestarting to write, or that I need to “get to know” my narrator well enough.These are valid tasks at first, but there’s a point at which they cross overinto being excuses for not starting to write. I enjoy Zadie Smith’s craft essay “That Crafty Feeling,” where she discusses the “Macro Planner” and the “MicroManager” type of writer and uses a house construction metaphor to distinguish betweenthem. She says that the former type of writer builds the entire house in a dayand then obsessively rearranges the contents and décor between all the variousrooms in order to attain the perfect set-up. The latter type of writer constructsthe house room by room, and only moves on to the construction of another roomor floor once the preceding one, with all its furniture and décor, is completeand perfect. I think I’m the latter kind of writer, which means that my first draftssound more or less like what I want them to be.

4 - Where does a work of prose usually begin for you? Are you anauthor of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are youworking on a "book" from the very beginning?

For me, a novel or short story often starts with a word or phrase Ilike, and I try to think of how to build a story around it. I do appreciatethat short stories can be sites from which a larger work grows. With the novelthat I am working on now, I felt quite stuck with the narrator I’d initially chosenfor it. At some point during this period of stagnation, I took a short storyworkshop with one of my favourite writers. She was complimentary about theshort story I submitted, saying something hyperbolic about its opening lines.So, I took those opening lines that I was now very proud of, and I made themthe novel’s opening lines. But the short story’s opening lines belonged to theshort story’s narrator. So I also imported that narrator into the novel and startedthe novel anew. It was a very positive development.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process?Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I haven’t done a great number of public readings, but I don’t imaginethem as impacting my writing. They seem to me to be a relatively innocuous activity.I’m shy, so I would not say that I’m actively looking to put myself in front ofan audience, but I’m also not afraid of readings, or of audiences. When I read mywork in my MFA program, a friend told me I sounded like the comedian StevenWright, but said he didn’t mean it as an insult, just that I had Wright’sstyle. I was happy to hear that I had a style, the style of someone famous,when I hadn’t been trying to have one and was just speaking in my normal mannerand way.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? Whatkinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you eventhink the current questions are?

I don’t consciously think of my work as a site for theoretical debateor reflection. I think of it as a place where I hopefully capture a strange orfun or interesting idea in a way that comes off as aesthetically pleasing for areader. I don’t have preconceived notions of what that idea should be. Though Ifigure that the act of writing about human characters—because it inevitablytouches upon and relates to human life and activity and thought—ends uptouching upon some aspects of current theoretical concerns. That seemsunavoidable.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in largerculture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer shouldbe?

I don’t think of writers, or any artists, as having a set role in orfor culture at large. I imagine some writers envision a role for themselves andtreat it as a guiding principle. But it would feel Orwellian to have a uniformrole be expected or imposed.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editordifficult or essential (or both)?

I consider my writer friends, my partner, my agent, and the editorswho are officially tasked with editing my work to all be “outside editors”without whom the work I make wouldn’t be sharable with the larger world,meaning, anyone beyond myself. Their feedback is essential, and it is also aluxury for which I am consciously very grateful.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarilygiven to you directly)?

My memory is quite bad so I don’t have a piece of advice that I carrywith me and treasure. I imagine this good piece of advice would deal withrevision.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres (shortstories to the novel)? What do you see as the appeal?

I find that short stories (and poems, and essays) provide a nicechange of pace and work a different writing muscle that probably somehow in theend works to make your main project better. I like to swim and it feels verynatural to shift from freestyle into other strokes during a workout, almostlike the body asks for it at points. Actually, I imagine a swimmer would sufferan injury in the long term without variety in strokes.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you evenhave one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I find writing to be entirely contingent on mood and my day jobschedule, and I think that precludes the possibility of a routine, which isunfortunate. I haven’t been able to be the kind of person who writes a setnumber of words no matter what each day, or to wake up very early. If I am in theright writing mood, and don’t have to be working for my job at that moment, Isit and start writing at my computer until the mood expires.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for(for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I find films to be extremely fertile in terms of inspiration whenwriting. Books are of course even more fertile, but dangerously so, in that onecan start to write too much like the writer they have just read and loved. Withfilm, there is that distance afforded by the difference in medium at least. It’sa good challenge to think, “I’ll write in the way that director has shot ascene, or created mood, or tone,” because it’s not clear what that means andthere’s no single, obvious way of achieving that. In that sense, wanting tomimic film is more like a prompt than an invitation to copy.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Any smell that I associate with my grandmothers’ houses. For instance,old moist basements and wet wooden cutting boards.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but arethere any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, scienceor visual art?

I imagine everything comes from a great multitude of sources,especially a creative work born from the human imagination—that would have themost sources of all. I don’t rely on a single something as a source in thesense that I consciously study it or expose myself to it and feel inconversation with it more than other things I encounter. I imagine everything Icome in contact with feeds into the brain that eventually makes a creativework.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, orsimply your life outside of your work?

I figure that my favourite writers must be those who end up being themost important for my work. I love Jane Bowles. In terms of more contemporarywriters, I love Amina Cain, Lina Wolff, Leanne Shapton, Claire-Louise Bennett,Sheila Heti, Samanta Schweblin, Patrick Cottrell, Sayaka Murata. I would saythat, currently, my favourite book is Marie NDiaye’s My Heart Hemmed In.

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I would like to learn to springboard dive, but from the three- andfive-metre springboards, not just the one-metre. I haven’t tried any of them,and am terrible at diving even from a pool deck.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would itbe? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had younot been a writer?

It’s hard to conceive of writing as my occupation, as it’s not myprimary source of income or what I can devote the majority of my time andattention to, unfortunately. But it is the primary thing I occupy myself withoutside of the hours I’m working on my day job tasks. In that sense, I guessit’s an occupation. If I were not doing it, I think I’d like to be a ceramicistor a painter. In a fantasy scenario, I’d like to be a musician, someone who ispart of The Wrecking Crew, or an NBA player. In a more realistic scenario, I’dalso like to teach swimming, especially to people who have an initial fear ofthe water.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

It’s hard to pinpoint the reasons behind an impulse like writing, or thepursuit of any other creative task, when it’s a thing that you’ve felt drawn tosince an early age. My guess is it’s a genetic predisposition mixed withunidentified environmental factors.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last greatfilm?

I’m a Lina Wolff fan and her new book Carnality is great. Afriend recommended Scorsese’s After Hours, from 1985, and that is themost recent film I’ve watched that I’ve been telling everyone I know to watchas well.

20 - What are you currently working on?

I’m working on a novel. The novel that grew outof the short story I mentioned above. I’m enjoying it very much.

May 14, 2023

Kim Trainor, A thin fire runs through me

And when you are gone I embalmyou

with words. Remove thetongue. Remove the eyes.

When they ask me aboutyou, I say I’ve moved on.

There’s this boy with anoud.

Always behind the barricades– no way in.

Your mouth a void.

So it was Hexagram 23after all. Stripping. Flaying. Splitting apart.

The typewriter cracksletters open. Splintered words.

My face is riddles withholes.

All night I was diggingat your grave. (“BLUEGRASS”)

Vancouver poet Kim Trainor’s third full-length poetry collection, after Karyotype(London ON: Brick Books, 2015) [see her ’12 or 20 questions’ interview from back then] and Ledi (Toronto ON: Book*hug 2018), is A thin fire runs through me (Fredericton NB: Icehouse poetry/Goose Lane Editions, 2023). As sheoffers in the book’s introduction:

A thin fire runs throughmebegan involuntarily, as a way of writing my way through a difficult time; thetitle poem functioned as a response to heartbreak, followed by depression, andeventually, the progression of new love. I wrote steadily over a period of aboutnine months, from late summer 2016 through the spring of 2017, roughly one poemevery two or three days, each poem a meditation on a different hexagram fromthe I Ching. The quotidian became interwoven with the political and the ecological.Through selection and juxtaposition of fragmented details, these hexagramsaimed to grapple with my own personal situation and to document the tenor ofthis time.

Composedas a book of changes and responses, the structure of seeking external promptsis reminiscent of Kingston writer Diane Schoemperlen’s debut novel In theLanguage of Love (1994), a book composed via one hundred chapters, each onebased on one of the one hundred words in the Standard Word Association Test. WhereasSchoemperlen was attempting to prompt and progress her narrative, Trainor’spurposes are far more meditative, working from the opening poem sequence-section,“BLUEGRASS,” through a selection of numbered poems across cluster-sections “THEBOOK OF CHANGES” and “SONG OF SONGS.” Her poems are reactive and responsive,offering phrases, images and sentences as both clusters and layerings, accumulatingacross each particular meditation. As each poem progresses, she works from andthrough her immediate via a different prompt, from the endings of onerelationship and the beginnings of another, and all else that falls amid and in-between.“I wait until the marquee for you.” she writes, as part of poem “33.,” “Oursecond date. Cohen’s name in lights.” As the poem ends, further down: “As youstand next to me. In the red light of the Fox / there’s a tower of song.”

Composedas a book of changes and responses, the structure of seeking external promptsis reminiscent of Kingston writer Diane Schoemperlen’s debut novel In theLanguage of Love (1994), a book composed via one hundred chapters, each onebased on one of the one hundred words in the Standard Word Association Test. WhereasSchoemperlen was attempting to prompt and progress her narrative, Trainor’spurposes are far more meditative, working from the opening poem sequence-section,“BLUEGRASS,” through a selection of numbered poems across cluster-sections “THEBOOK OF CHANGES” and “SONG OF SONGS.” Her poems are reactive and responsive,offering phrases, images and sentences as both clusters and layerings, accumulatingacross each particular meditation. As each poem progresses, she works from andthrough her immediate via a different prompt, from the endings of onerelationship and the beginnings of another, and all else that falls amid and in-between.“I wait until the marquee for you.” she writes, as part of poem “33.,” “Oursecond date. Cohen’s name in lights.” As the poem ends, further down: “As youstand next to me. In the red light of the Fox / there’s a tower of song.”Thepoems included in the second and third sections, which make up the bulk of thecollection, are each numbered, but not set sequentially: nine followsfifty-two, which follows forty-nine, for example. As poem “60.,” set mid-pointin “THE BOOK OF CHANGES,” opens: “Jie. Articulating. / The joints thatdivide // a bamboo stalk. Spine. / Tongue. // Touch the edges of words – / Radicaltalk. Glottal. Stop.” Held together as a singular unit, the poems that make up Athin fire runs through me offer a collage of images and references fromthat particular period of compositional time, from bicycle wheels in Vancouver,sex and forms of the Sabbath to quotations by US President Donald Trump,displaying that era of upheaval and change through a sequence of meditative prompts.The poems aren’t working to seek order from the chaos, but are a record of herown processes of chaos, and her meditations through them. “And who will dietoday of fentanyl? / And who by law? // Inject the burning shot, / euphoriarushing. And then the dark.” (“21.”).

Thepoems saunter, casually, moving from moment to moment across a wide spectrum: “Ihave not seen you in five days.” poem “64.” offers, two-thirds through thesecond section. “When we meet / you tell me of all the creatures born at dusk,between worlds. // The frogs who are disappearing. / Their translucent skin. //Created at twilight on the eve of the Sabbath, / these defective creatureswho cleave neither above nor below.” As her introduction continues:

The quotidian offersus up minutiae – tweets, Instagrams, texts, social media posts, online news. Wepeer into other lives; we absorb words, headlines, violent events. We see andwe don’t see. These scraps are unintegrated, unintegrable, yet we carry them. Attimes, only poetry seems an adequate medium of response.

Afourth full-length collection, A blueprint for survival, is scheduled toappear with Guernica Editions in spring 2024.

May 13, 2023

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Cynthia Hogue

Cynthia Hogue’s new poetry collection is instead, it is dark (Red HenPress, 2023). Her ekphrastic Covid chapbook is entitled Contain (TramEditions 2022), and her new collaborative translation from the French of NicoleBrossard is Distantly (Omnidawn 2022). She served as Guest Editor forPoem-a-Day for September (2022), sponsored by the Academy of American Poets.Hogue was the inaugural Maxine and Jonathan Marshall Chair in Modern andContemporary Poetry at Arizona State University. She lives in Tucson.

1 - How did your first book change your life? How does yourmost recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

My first book in the States was published about thirtyyears ago, The Woman in Red (Ahsahta Press, 1989). I also had a limited-editioncollection published by Whiteknights Press in the U.K. earlier in the decade, Wherethe Parallels Cross. Both books were published around the time that I wasworking on and finishing up a Ph.D. at the University of Arizona, and thanks tothem, I was offered my first job at the University of New Orleans as apoet-scholar. Now, that job changed my life.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say,fiction or non-fiction?

I started writing poetry as a child. It's true, I alsowrote in other genres. I created a neighborhood newspaper when I was 10. Iwould assign the other children articles to write, but in fact, I wrote andproduced the only issue I was able to make by myself. In high school, a specialclass in creative writing was offered by my favorite English teacher, and inthat class, I wrote poetry. I attended Oberlin College in the year they offeredtheir first creative writing class in poetry, in the Experimental College. Itried other genres, but always returned to poetry. I had fun trying out fictionin New Orleans, but never finished anything I wrote. And I labored on amemoir-essay about living with someone, my first husband, with TourettesSyndrome, and also about the onset of Rheumatoid Arthritis in my mid-forties. Iwas pleased with those essays, but the first took me a decade to finish, sinceI didn't know what I was doing!

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writingproject? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Dofirst drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work comeout of copious notes?

Really depends on the project. In the last decade or so, asI explored drawing on research for book-length projects, my whole creativeprocess shifted from writing individual poems in short bursts to a slower,longer framework for completing a book, even if poems were arranged in series.I discovered a remarkable slave story in New Orleans right before I was leavingfor another position, the last slave to use the courts to sue for emancipationon the eve of the courts being closed to slaves with the signing of theFugitive Slave law. This slave, Cora Arsene, won her case. Dred Scott, in adifferent state but the same year, did not. Writing that long poem entailed adecade of research about Southern slave history (including the HaitianRevolution), and much much consideration of genre. The new collection, instead,it is dark, began with the shock of my husband's massive heartattack. He was born into occupied France, and my rather inchoateimpulse as I began the book was to honor his life by turning some of hismemories and dreams into poems. I conducted a lot of research and ended upinterviewing his extended family in France for this collection.

4 - Where does a poem or translation usually begin for you?Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project,or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

For the translation of Nicole Brossard's Lointaines,which I published last year with Omnidawn as Distantly (with myco-translator, Sylvain Gallais), I eased into that serial project as if it werehot water, translating poems in the series here and there until we finallydecided to translated the whole book. With my last poetry collection, InJune the Labyrinth, I had been going on a sort of annual pilgrimage toChartres Cathedral every year for a decade when I decided to challenge myselfto write a book-length serial poem around the subject of the labyrinth. Iwanted to see if I could sustain a book-length project, but I adopted a loosenarrative structure to do so.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creativeprocess? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I rarely do solo readings, preferring group readings, andthey are certainly not part of my creative process, no.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind yourwriting? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? Whatdo you even think the current questions are?

I just returned fromthe wonderful New Orleans Poetry Festival, where I was on a panel called“Uncanny Activisms” (Lesley Wheeler’s terms for poetry in the tradition ofspells and prayers), so this is what I’ve been thinking about of late: Howcan/does poetry effect change? How does poetry matter (I actually neverquestion that it matters, being such an ancient art form, but realistically,how many people does it reach?) In his essay “On Poetry,” Velimir Khlebnikovraised the question of spells and incantations, magic words that are sometimes“beyonsense” in sacred or folk language. Great power is attributed to thesewords, and to magic spells, he says, because they are believed to contain magicand be capable of influencing our fate. Such poems and incantations go straightover the heads of leaders to Spirit. Khlebnikov said that “the magic in a wordremains magic even if it is not understood, and loses none of its power.” Thesedays, I am thinking very pointedly about the humane, inflected inspiritual and activist terms, in the hopes of changing, affecting, orraising consciousness. And sometimes, because I greatly admire many works indidactic tradition, I write poems with dryer, discursive statements inflectedby sonic lyricism.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being inlarger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writershould be?

In the past, great writers could be cultural and politicalvoices, like a Yeats, Orwell, Pablo Neruda, Gore Vidal, Simone de Beauvoir, AlbertCamus. James Baldwin. Toni Morrison. Margaret Atwood today, Barbara Kingsolver,Ta-Nehisi Coates. The larger culture, I believe, benefits from the voices ofwriters and artists speaking in a more public arena, but now, with socialmedia, there is a levelling effect. A real democracy of voices. It can be hardto judge which voices are worth listening to. What writers offer is athoughtful, attentive, perhaps an ethical viewpoint. Many writers make theirliving teaching, and one by one, as students of literature and creative writinglearn the field, they are changed, at least potentially. Writers play the roleof mentor, sometimes guide, teaching students the skills to think forthemselves. Maybe that isn’t the role I think they should have, but I’ve cometo see it as important.

8—I’ve skipped that question, as I don’t have muchexperience with an outside editor.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (notnecessarily given to you directly)?

Go where you are loved. Over the courseof a life, one receives much advice and counsel, sometimes requested andsometimes offered. This piece of advice is to be found in H.D.’s Trilogy, Ithink, and it is likely from the Bible. Once I took it in, during a dark timein my life, I never forgot it, and sometimes, I follow it.

10 - How easy has it been for you to move between genres(poetry to translation)? What do you see as the appeal?

I don’t see translating poetry as moving between genres.It’s certainly moving between languages, but in my experience, I feel I know myway around a poem that has been translated literally from another language—evenif I don’t immediately understand what the poet is doing. The strong appeal oftranslating other poets is the work enlarges your horizon, your language, andreplenishes and inspires the imagination.

11 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, ordo you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Every day, I begin with some kind of writing. If I don’thave many interruptions, and especially, if I’m working on a longer project,I’ll usually write a poem or at least a draft. When I was writing my pandemicchapbook, CONTAIN, in the first months of lockdown, I had received a gorgeousvisual series from an artist I met at MacDowell, and I went into a kind ofaltered state of consciousness, meditating each day on one of the visual formsand writing an ekphrastic poem. Since there were no interruptions at that stageof the pandemic lockdown, I wrote 40 poems in 40 days. Very unusual for me, butthen the circumstances were intense and extraordinary.

12 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn orreturn for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I turn to poetry, reading some or many of the books piledon floor and desk, and I turn to nature.

13 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Lilacs.

14 - David W. McFadden once said that books come frombooks, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature,music, science or visual art?

As mentioned earlier, visual art (in the case of CONTAIN,the series by the remarkable Morgan O’Hara), sometimes history (as in the slavenarrative, “Ars Cora”), sometimes architecture (such as Chartres Cathedral,which has one of the few labyrinths that survived the French revolution), andin the beginning and for many years, and even now, nature.

15 - What other writers or writings are important for yourwork, or simply your life outside of your work?

Dickinson and H.D., to some extent Marianne Moore, Stevens,Eliot, Gwendolyn Brooks, Muriel Rukeyser, Adrienne Rich, C.D. Wright, Forrest Gander, Lissa Wolsak, Nicole Brossard, Kathleen Fraser. Gary Snyder was veryimportant to me at one point, and Robert Bly, William Stafford. Nathaniel Mackey and Rachel Blau DuPlessis are amazing. I read deeply into Afaa Weaver,Alice Fulton, Brenda Hillman. Seamus Heaney’s North, his translation of Beowulf.Paul Celan. Those are some of the poets I return to. I am always open to prosethat is as beautifully written as poetry. I always read Barbara Kingsolver.There was a German writer I was much taken with, and she was beautifullytranslated: Christa Wolf. I am friends with a prose writer of great gifts,Karen Brennan (who is also a fine poet).

16 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Actually, I went to Greece once many years ago, and I wouldlike to go back. The last time I saw an eastern autumn was ages ago, and I planto return to New York next fall to see the leaves.

17 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt,what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended updoing had you not been a writer?

I’d been planning on being a doctor. A scientist. Orperhaps a naturalist. I loved the outdoors. I began college as a biology major.But I loathed dissecting piglets and frogs and I fell in love with poetry. Mygrandmother had a gorgeous soprano, and had I inherited her voice, I might havetried to be an opera singer. I do love music.

18 - What made you write, as opposed to doing somethingelse?

I seemed to be good at it. I was otherwise very messed upwhen I was young, and writing poems was like my North Star.

19 - What was the last great book you read? What was thelast great film?

Demon Copperhead, by Barbara Kingsolver. Eo, one of the most painfulanimal rights films to watch, which I almost couldn’t finish watching.

20- What are you currently working on?

Ipublished three books over the last year, so I am in a fallow period. Gatheringmy thoughts, doing some readings and writing micro-essays.

rob,Thank you so much for these questions! This has been fun.

May 12, 2023

Margaret Ray, Good Grief, the Ground

It’s 2022. The world isending, but how fast? and for whom? and what do we have to pay to keep itaround for a little longer, just until we get that one last day with our kids, lasthour of rolling around in bed (with or without someone else in the bed), lastpancake, last walk, last book we love to read?

Good Grief, the Ground might be oneof those last books: light enough to come back to us, and heavy enough to staywith it. It certainly feels “like the end of something” to Margaret Ray, who is—orwrites as—a white, adult, American woman with Florida roots and a presence inNew Jersey now, a teacher still close to the epoch of fortunate teens, for whom“no one/ is dead yet,” teens full of hunger, “ready to go somewhere.” What do wedo with that hunger if we grow up, if we realize that some people are hungryfor us, that some people are never full, that we too have needs we mistake forwants and vice versa, that two contradictory things can be true? (StephanieBurt, “FOREWORD”)

Winnerof the 21st annual A. Poulin Jr. Poetry Prize, as selected by Stephanie Burt, is New Jersey-based poet Margaret Ray’s full-length poetry debut,

Good Grief, the Ground

(Rochester NY: BOA Editions, 2023), a book that holdstogether as a selection of lyric narrative rolls and extended rushes. Offering portraitsof small town urban/suburban teenhood, Ray crafts urgent poems that strikethrough memory as they pour out sentence accumulations and lines that see no enduntil they finally, eventually, do. “I want to tell you about two events / thatform the cusp of a childhood:,” she writes, near the opening of the poem “ExpulsionLessons but Replace the Garden with a Swamp,” “One thing happened to me(alone), / and one happened (on TV) to America / after it happened (in private)to a pair // of people I’ll never meet.”

Winnerof the 21st annual A. Poulin Jr. Poetry Prize, as selected by Stephanie Burt, is New Jersey-based poet Margaret Ray’s full-length poetry debut,

Good Grief, the Ground

(Rochester NY: BOA Editions, 2023), a book that holdstogether as a selection of lyric narrative rolls and extended rushes. Offering portraitsof small town urban/suburban teenhood, Ray crafts urgent poems that strikethrough memory as they pour out sentence accumulations and lines that see no enduntil they finally, eventually, do. “I want to tell you about two events / thatform the cusp of a childhood:,” she writes, near the opening of the poem “ExpulsionLessons but Replace the Garden with a Swamp,” “One thing happened to me(alone), / and one happened (on TV) to America / after it happened (in private)to a pair // of people I’ll never meet.” I’mintrigued at her poem-recollections and warnings that speak of the dangers anddrama of growing up and remaining, somehow, alive; writing on dark paths, darkcorner and the crevices of youth, violence and small towns. “Think of how skin/ glues itself back together after you slice your finger / chopping an onion,”she writes, as part of the poem “Enough,” “Not scar as metaphor no / how longit takes How quick the knife / Theproblem with children is that if you’re lucky // they grow up [.]” Or theincredibly striking “Reader, I Married Him,” riffing off the infamous quotefrom Charlotte Brontë’s novel Jane Eyre (1847), that references youthfuldigression, hints at shades of domestic violence, and plays a number ofquick-turns and insights, including: “I threw the book at him and slammed / thedoor on the way out. In a poem I can leave / when I should have.” From the hardlessons of experience and distance, Ray writes generously of the hopes that youthmight hope and how inexperience can blindside even the sharpest mind. “It waslater, later,” she writes, as part of “Expulsion Lessons but Replace the Gardenwith a Swamp,” “once I turned the memory off its shelf / and turned it overagain, only / once I knew what he’d been doing / while he looked at me, that’s// when I was no longer a child.”

There’sa way that the structure of her collection feels akin to a sequence ofcalls-and-response, a back and forth of a section-cluster of poems followed bya single, stand-alone lyric, a second section-cluster followed by a further single,stand-alone lyric, and so on, offering a quartet of such pairings to make upthe larger structure of what becomes Good Grief, the Ground. The short pieces—“Wandais a Particle Physicist,” “Wanda Vibing,” “Wanda in the World” and “At a Distance”—almostexist as a kind of connective tissue that threads through the collection andholds it together into a larger narrative. As the first of these poems end: “Wandalooks back / at the traces her particles have left, // moving through a field.”It is interesting how the character “Wanda” somehow floats at a distance fromthe main action of the book, somehow tethered but unaffected, or even above,whatever may have occurred before. There is only what is happening now.

May 11, 2023

Spotlight series #85 : Eric Schmaltz

The eighty-fifth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Toronto-based poet, editor and critic Eric Schmaltz.

The eighty-fifth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring Toronto-based poet, editor and critic Eric Schmaltz.The first eleven in the series were attached to the Drunken Boat blog, and the series has so far featured poets including Seattle, Washington poet Sarah Mangold, Colborne, Ontario poet Gil McElroy, Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Ottawa poet Jason Christie, Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough, Ottawa poet Amanda Earl, American poet Elizabeth Robinson, American poet Jennifer Kronovet, Ottawa poet Michael Dennis, Vancouver poet Sonnet L’Abbé, Montreal writer Sarah Burgoyne, Fredericton poet Joe Blades, American poet Genève Chao, Northampton MA poet Brittany Billmeyer-Finn, Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer from Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1 territory) poet, critic and editor Joshua Whitehead, American expat/Barcelona poet, editor and publisher Edward Smallfield, Kentucky poet Amelia Martens, Ottawa poet Pearl Pirie, Burlington, Ontario poet Sacha Archer, Washington DC poet Buck Downs, Toronto poet Shannon Bramer, Vancouver poet and editor Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Vancouver poet Geoffrey Nilson, Oakland, California poets and editors Rusty Morrison and Jamie Townsend, Ottawa poet and editor Manahil Bandukwala, Toronto poet and editor Dani Spinosa, Kingston writer and editor Trish Salah, Calgary poet, editor and publisher Kyle Flemmer, Vancouver poet Adrienne Gruber, California poet and editor Susanne Dyckman, Brooklyn poet-filmmaker Stephanie Gray, Vernon, BC poet Kerry Gilbert, South Carolina poet and translator Lindsay Turner, Vancouver poet and editor Adèle Barclay, Thorold, Ontario poet Franco Cortese, Ottawa poet Conyer Clayton, Lawrence, Kansas poet Megan Kaminski, Ottawa poet and fiction writer Frances Boyle, Ithica, NY poet, editor and publisher Marty Cain, New York City poet Amanda Deutch, Iranian-born and Toronto-based writer/translator Khashayar Mohammadi, Mendocino County writer, librarian, and a visual artist Melissa Eleftherion, Ottawa poet and editor Sarah MacDonell, Montreal poet Simina Banu, Canadian-born UK-based artist, writer, and practice-led researcher J. R. Carpenter, Toronto poet MLA Chernoff, Boise, Idaho poet and critic Martin Corless-Smith, Canadian poet and fiction writer Erin Emily Ann Vance, Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi, Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, Canadian poet Peter Jaeger, Birmingham, Alabama poet and editor Alina Stefanescu, Waterloo, Ontario poet Chris Banks, Chicago poet and editor Carrie Olivia Adams, Vancouver poet and editor Danielle Lafrance, Toronto-based poet and literary critic Dale Martin Smith, American poet, scholar and book-maker Genevieve Kaplan, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic ryan fitzpatrick, American poet and editor Carleen Tibbetts, British Columbia poet nathan dueck, Tiohtiá:ke-based sick slick, poet/critic em/ilie kneifel, writer, translator and lecturer Mark Tardi, New Mexico poet Kōan Anne Brink, Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Melanie Dennis Unrau, Vancouver poet, editor and critic Stephen Collis, poet and social justice coach Aja Couchois Duncan, Colorado poet Sara Renee Marshall, Toronto writer Bahar Orang, Ottawa writer Matthew Firth, Victoria poet Saba Pakdel, Winnipeg poet Julian Day, Ottawa poet, writer and performer nina jane drystek, Comox BC poet Jamie Sharpe, Canadian visual artist and poet Laura Kerr, Quebec City-area poet and translator Simon Brown, Ottawa poet Jennifer Baker, Rwandese Canadian Brooklyn-based writer Victoria Mbabazi, Nova Scotia-based poet and facilitator Nanci Lee, Irish-American poet Nathanael O'Reilly, Canadian poet Tom Prime, Regina-based poet and translator Jérôme Melançon and New York-based poet Emmalea Russo.

The whole series can be found online here.

May 10, 2023

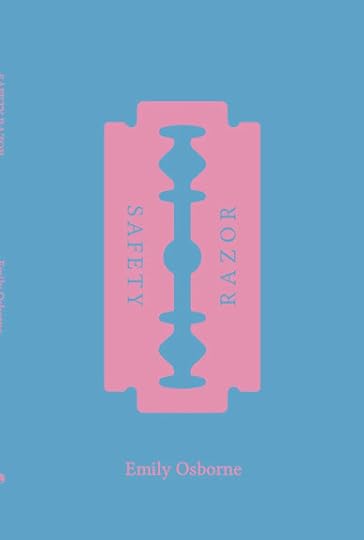

Emily Osborne, Safety Razor

“Sonatorrek”

Hardly can I hoist

my tongue or mount

song’s steelyard, forgeverse

in my mind’s foundry.

My tear-sea swamps

poetry, yet verse flows

like gore from a giant’s

throat onto Hel’s port.

The cruel sea hackedthrough

the fence of my kin.

A gap rots, unfilled,

Where my sons flourished.

I carried one son’scorpse.

I carry word-timber,

leafed in language,

from the speech-shrine.

I’mintrigued by the lyric density of the narratives in Bowen Island, British Columbia-based poet Emily Osborne’s full-length debut,

Safety Razor

(Guelph ON: GordonHill Press, 2023). “Thunder strums through my earliest memory / of family dinner.”she writes, to open the opening poem, “Infant amnesia,” “Summer in Ontario, //lightning pulses on the table. In the post- / voltaic hush, Dad tunes the radioto sirens, // tornado. We rush to the basement but / I’m leashed to myhighchair so Dad hauls // the hybrid downstairs, my bib scattering / remnantsin the dim.” She offers stories, memories and short scenes that unfold andunfurl with such careful precision, physicality and rootedness, composed withina present that includes moments across time and space to meet correspondingmoments of flesh and bone. As she writes as part of the poem “Diacritics”: “Yousaid my consonants split and replicate / like cells in tumours.” Writing onscrimshaws, dinosaur bones, runes, DNA, relativity, pollution, weather, balladsand folk tales, Osborne’s poems are centred on her narrative self, but also populatedwith different eras and perspectives, and the collection includes a selectionof poems that fold in a handful of her translations of Old Norse-Icelandic skaldicverse from the tenth to the twelfth centuries. I’m curious about her engagementwith such particular histories and old forms, and her author biography offersthat she “completed an MPhil and PhD at the University of Cambridge, in OldEnglish and Old Norse Literature.”

I’mintrigued by the lyric density of the narratives in Bowen Island, British Columbia-based poet Emily Osborne’s full-length debut,

Safety Razor

(Guelph ON: GordonHill Press, 2023). “Thunder strums through my earliest memory / of family dinner.”she writes, to open the opening poem, “Infant amnesia,” “Summer in Ontario, //lightning pulses on the table. In the post- / voltaic hush, Dad tunes the radioto sirens, // tornado. We rush to the basement but / I’m leashed to myhighchair so Dad hauls // the hybrid downstairs, my bib scattering / remnantsin the dim.” She offers stories, memories and short scenes that unfold andunfurl with such careful precision, physicality and rootedness, composed withina present that includes moments across time and space to meet correspondingmoments of flesh and bone. As she writes as part of the poem “Diacritics”: “Yousaid my consonants split and replicate / like cells in tumours.” Writing onscrimshaws, dinosaur bones, runes, DNA, relativity, pollution, weather, balladsand folk tales, Osborne’s poems are centred on her narrative self, but also populatedwith different eras and perspectives, and the collection includes a selectionof poems that fold in a handful of her translations of Old Norse-Icelandic skaldicverse from the tenth to the twelfth centuries. I’m curious about her engagementwith such particular histories and old forms, and her author biography offersthat she “completed an MPhil and PhD at the University of Cambridge, in OldEnglish and Old Norse Literature.”

“Verse making”

Goddess of therune-carved mead mug,

I’ve smoothed the prow ofthis song-ship.

Lovely lady, tree whocarries cups,

I deftly ply my tongue,the lathe of poems.

Organizedinto three sections—“FIRST CUTS,” “BARE BONES” and “FLESH MEETS”—the poems of SafetyRazor are infused with a density and a depth, and there is an attentivenessand a precision to Osborne’s lyrics that is quite striking, setting words downwith the deliberateness of letters carved directly into stone. “Art is youngerthan dirt,” the poem “Scrimshaw” ends, “only / as old as petroglyphs coating /earth’s aortas: […]” As well, I’m always intrigued by writers who are theoffspring of other writers [see my recent Touch the Donkey interviewwith Victoria, British Columbia poet Hilary Clark, in which she responds to aquestion around the work of her son, Winnipeg poet Julian Day], and I recentlyfound out that Osborne’s mother, Mary Willis, is the author of the poetrytitles Under this World's Green Arches (1977) and Earth’s Only Light(1981), both of which appeared through the Fiddlehead Poetry Book series. I wouldbe curious to know what echoes might have come through Osborne’s work from hermother, impossible to know for certain without knowing her mother’s work, or ifthere is any overt influence at all. “What else can I give my sons,” shewrites, as part of “Heirlooms,” “from my mother but pale eyes and stories?”

Eitherway, this is a collection that is fully aware of roots that span distances vastand intimate, moving in a myriad of directions, and even further, as thecollection closes with a small cluster of poems on new parenting. “Oh my son,”she writes, as part of “Labour, Eastertime 2019,” “from where did you come? /It’s true I didn’t see you until the curtain / lifted. But other hands are alwaysfirst // to catch, pull, hold you. Alone / I feed you, while the postnatal /room’s analog snips through sleep.” Razor Safety is a collection aware oftethers and tendrils, aware of what holds and where she reaches, seeking out andacknowledging a plethora of connections and connective tissue, no matter thedistances. Or, as she writes to close the poem “20-week scan”:

On these tones yourfather and I coast

through winter, foregoforeign travel,

speak of you. His basscaroms images,

half accurate perhaps. Afterthe first

made-up years, our wordsstatic back

until we’re parent shipsprojecting signals,

hoping you’ll echo. The biggeryou grow,

the less we know you’veheard us

our sonar broken

on open ocean