Rob Mclennan's Blog, page 5

September 8, 2025

Jackson Mac Low, The Complete Stein Poems 1998-2003, ed. Michael O’Driscoll

Indeed, as Mac Low was at pains to emphasize time andagain in the last decades of his life, procedural operations are anything but amatter of chance:

In the 1960s, when Ifirst devised and utilized deterministic methods, I thought that the methodsthat I know realize are deterministic were kinds of chance operations. It wasonly in the early 90s that I realized that such methods are basically differentfrom chance operations. The principal difference is that if one employs adeterministic text-selection method correctly, using the same sourcetext and seed text and making no mistakes, the method’s output willalways be exactly the same. Chance operations produce a different output eachtime they are utilized. Deterministic methods do not involve what could rightlybe called “chance,” or as many artists have termed it, “objective hazard.”

The Tucson lecture, whichI’ve cited here and throughout my introduction, and which follows as a furtherintroduction to this volume, is an important example of Mac Low’s extendedattempts to nuance the historical record of his role as the champion of chanceoperations. As I’ve documented elsewhere, from about 1980 onward Mac Lowrepeatedly sought to correct the overemphasis on chance and what he no longerregarded as the “egoless” composition of purportedly nonintentional works. Thiseffort extended, importantly, to his own central statements on the allied workof John Cage, including the essay “Cage’s Writing up to the Late 1980s,” whichMac Low revised no fewer than five times over a period of fifteen years with anincreasing emphasis that accentuates his own investments in this piece. Thecentral point of Mac Low’s 2001 version of the essay is that while Cage’smesostic methods are nonintentional and deterministic, the textual selectionsand aesthetic judgments that precede and follow the mesostic procedure arematters of choice. But this reluctance to subordinate fully his own creativeimpulses to procedural or chance determinants was also very much in keepingwith his regular refusal of the label “experimental poet.” For Mac Low, the useof deterministic procedural methods was not, as is so often supposed, a matterof experimentation. (Michael O’Driscoll, ““This shining makes revision of astring more strange”: An Introduction to Jackson Mac Low’s The CompleteStein Poems”)

I’mimpressed by the heft, at nearly six hundred pages, of the newly-publishedcollection The Complete Stein Poems 1998-2003 by Jackson Mac Low, editedby Michael O’Driscoll, with a foreword by Anne Tardos (Cambridge MA: The MITPress, 2025). The Complete Stein Poems assembles Mac Low’s final, great proceduralwork together for the first time, meticulously compiled and criticallyarticulated by critic Michael O’Driscoll, a Professor in the Department ofEnglish and Film Studies at the University of Alberta in Edmonton. In case you aren’taware, American poet, performer, composer and visual artist Jackson Mac Low (1922-2004),as the back cover of this particular volume offers, “was a leading member ofthe Fluxus group, an innovator of procedural poetics and liminal compositional forms,and a progenitor of the Language Poets and other conceptual artists.”

I’mimpressed by the heft, at nearly six hundred pages, of the newly-publishedcollection The Complete Stein Poems 1998-2003 by Jackson Mac Low, editedby Michael O’Driscoll, with a foreword by Anne Tardos (Cambridge MA: The MITPress, 2025). The Complete Stein Poems assembles Mac Low’s final, great proceduralwork together for the first time, meticulously compiled and criticallyarticulated by critic Michael O’Driscoll, a Professor in the Department ofEnglish and Film Studies at the University of Alberta in Edmonton. In case you aren’taware, American poet, performer, composer and visual artist Jackson Mac Low (1922-2004),as the back cover of this particular volume offers, “was a leading member ofthe Fluxus group, an innovator of procedural poetics and liminal compositional forms,and a progenitor of the Language Poets and other conceptual artists.”Thepoems that make up The Complete Stein Poems was composed, as editor O’Driscollwrites in his introduction, across more than half a decade through a preciseformal procedure “[…] that Mac Low himself had invented in 1963 in order togenerate poetic material determined by algorithmic rules. This latest versionof the program, crated in 1994 at Mac Low’s request, was a fifth generation ofthe original 1989 DIASTEXT code, now revised to handle larger inputs. The algorithm,following Mac Low’s procedure, sequentially drew words from the source textthat correspond to the placement of letters in the seed text. The placement ofletters in the first word of the seed, ‘l-i-t-t-l-e’ in this case, resulted inthe first line of the output: ‘Little lIngering faTher titTlereguLar simplE.’ Having completed a full cycle of testing thesource text against the seed text, the program terminated its output atthirty-five lines. Saving the results to his hard drive, now in the wee hoursof the morning of April 28, Mac Low would go on to massage the raw output thefollowing day, excising and altering redundant words, introducing capitals,periods, and line spaces to give the poem its desired form, titling the resultfrom the initial and concluding words of the poem, and recording the wholeprocess and the interventions he’d made into a summary ‘makingways’ note alongwith the location and date that concludes the poem.” The source text that O’Driscollrefers to Mac Low working from for this project were A Stein Reader,edited with an introduction by Ulla E. Dydo (Northwestern University Press,1993) and “a corrected version” of Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons (1914),and the collision of unexpected words against each other are exactly the point ofthis project, pushing language into and against itself, twisting the possibilitiesof sound and meaning through a highly formal and precise procedure. As thepiece “One Completely,’ cited as “(Stein 16),” a poem “derived from a source passage in Stein’s“Orta or One Dancing” begins: “one / one / one who. // This who them son / notcame something / was her / her come / come her that.” The Complete SteinPoems is certainly a precursor to multiple, possibly hundreds, of other proceduralworks, whether Christian Bök’s infamous and award-winning Eunoia (TorontoON: Coach House Books, 2001) or Derek Beaulieu’s “The Newspaper,” as well asmore recent work by Ottawa poet Grant Wilkins.

Givencontemporary conversations and concerns around creativity and AI, one certainlywouldn’t confuse this as a work done by machine, as the human hand stillremains central to Mac Low’s creation, from the final edits and touches to thedevelopment of the initial process. One can read through the poems withoutnotation, or move deeply through the precise detail of how Mac Low moved fromsource material to where each piece landed, through Mac Low’s hand. Or thefirst poem, “Little Beginning,” a piece cited “New York: 27-28 April 1998; 23March, 29 April 2002” that offers the note: “Derived from a page (and precedingline) of Gertrude Stein’s ‘A Long Gay Book’ (A Stein Reader, edited byUlla E. Dydo, last line of 240 through 241—determined by a logarithm table) viaCharles O Hartman’s program DIASTEX5, his latest automation of one of mydiastic procedures developed in 1963, using the 1st paragraph of thesource as seed, and subsequent editing: some excisions of words, changes ofword order within lines; and changes and additions of capitals, periods, andspaces.” As the first half of that piece reads:

Little lingering fatherlittle regular simple.

Little long length therelouder happening deepening.

Beginning and little waysinging neat cooked.

Difference certain lengthtime light much lighting.

Description certain choosingis the piece.

Pleasant the derangedrhubarb pudding permitted stay.

Sit sing laugh soilingnot lingering sing.

Singing differenceconclude long so to mention.

Length is stay sit singlaugh soiling beginning.

Singing and any and whichthe way singing has higher.

Is material long veryfried the pears when abuse.

And say filled makesafternoon with children there.

It is.

September 7, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jesi Bender

JesiBender is the author of the novel

Child of Light

(Whiskey Tit 2025), thechapbook Dangerous Women (dancing girl press 2022), the play

Kinderkrankenhaus

(Sagging Meniscus 2021), and the novel

The Book of the Last Word

(Whiskey Tit 2019). The Brooklyn production of Kinderkrankenhaus was atop-five finalist for the BroadwayWorld's Best Off-Broadway Play 2023. Her shorter work has appeared in Vol. 1 Brooklyn, Denver Quarterly,FENCE, and Sleepingfish, among others. She also runs KERNPUNKTPress, a home for experimental work. www.jesibender.com

JesiBender is the author of the novel

Child of Light

(Whiskey Tit 2025), thechapbook Dangerous Women (dancing girl press 2022), the play

Kinderkrankenhaus

(Sagging Meniscus 2021), and the novel

The Book of the Last Word

(Whiskey Tit 2019). The Brooklyn production of Kinderkrankenhaus was atop-five finalist for the BroadwayWorld's Best Off-Broadway Play 2023. Her shorter work has appeared in Vol. 1 Brooklyn, Denver Quarterly,FENCE, and Sleepingfish, among others. She also runs KERNPUNKTPress, a home for experimental work. www.jesibender.com1 -How did your first book or chapbook change your life? How does your most recentwork compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

I hada chapbook published in 2010 called Glossolalia by MFG ImprintPublishing. I'm not sure how long theywere around but I can't find any remnants of them online anymore. It had a very small run and sold mainly to myfriends and friends of my parents. Itwas another nine years before my first novel, The Book of the Last Word, waspublished by Whiskey Tit, though I had begun that book at the same time asGlossolalia. My novel felt more'real'—it got reviews, had people besides my family read it. But the most significant part of getting thenovel published was that it connected me to many more writers. As someone who thought it was more prudent toget an MLIS than a MFA, I've really cherish the community that came along withpublishing with a small press, as I never had that before.

2 -How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

I'minterested in language, its melody and myriad meanings. It seems to me that poetry is a more readyopportunity to play. Poetry seems tohave no rules, while fiction people really want to impose a lot of rules onyou. That's my experience, anyway.

3 -How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does yourwriting initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appearlooking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copiousnotes?

Mynovel and plays follow the same path. Istart with a specific movement or event (Victorian Spiritualism for Child ofLight) and do copious research on the elements and people involved. From those notes, I etch out an outline. Then, I fill each chapter in with notes andphrasings that I've come up with so far and flesh out each passage. After that, of course, the editing begins.

4 -Where does a poem or work of prose usually begin for you? Are you an author ofshort pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working ona "book" from the very beginning?

Thepiece is almost always the piece, be it a poem or a novel, a play or a shortstory, from the get-go. A singleentity. I very rarely piece separateitems together to make one manuscript.

5 -Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you thesort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I doreadings after publication usually, though I am not the best reader in theworld. As a child, I was 'pathologicallyshy' so it has taken a while to feel comfortable in front of a crowd. In a similar vein, I've loved having readingsand performances of my plays—it is so energizing to hear the words out loud andsee different interpretations. I thinkevery poet and writer should write a play and see it performed. It will change you!

6 -Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds ofquestions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think thecurrent questions are?

Yes,each work is asking a question and the novel or play or poetry collection isthe product of my attempts to answer. For Child of Light, a novel set in 1896 about a young girl tryingto connect with her distant family through their interests (Spiritualism anddomestic electricity), I'm concerned with meaning-making and epistemology andhow they impact identity and reality.

7 –What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do theyeven have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Writers,a subsect of the larger 'storyteller' group, will be important as long as thereare people around. We critique, wedocument, we advocate and struggle—most importantly, we connect.

8 -Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult oressential (or both)?

I'veyet to have a difficult encounter with an editor on a creative project (onacademic articles, that's another story...). Editors are essential for not only the mechanics, but as a litmus forhow successful a writer has been with story, accuracy, and continuity.

9 -What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to youdirectly)?

Investin yourself. I think this is animportant thing for women to hear, in particular.

10- How easy has it been for you to move between genres (poetry to fiction toplays)? What do you see as the appeal?

I lovemoving between genres. My writing styleand ethos makes it so I'm never really straying far from any genre, even whenI'm working on another. Child of Lightis a novel but some chapters are poems or songs or visuals or dialogue. They are always together.

11- What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one?How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I'm amom and have a full-time job so writing happens 'where it will'—late at night,during lunch breaks, when I'm waiting at a doctor's office or my daughter'sdance class.

12- When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack ofa better word) inspiration?

I findarthouse films rejuvenating or I read small press books—I just picked up TheMothering Coven by Joanna Ruocco and The Maze of Transparencies by KarenAn-Hwei Lee, both from Ellipsis Press.

13- What fragrance reminds you of home?

I livein the woods, so leaves, grass, and dirt. Rain and wildflowers. If we'reinside, popcorn.

14- David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there anyother forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visualart?

Musicplays a big role. I like books that'sing' to you and hold a real musicality. I also like modern art and breaking down form in new and unexpectedways. I thought a lot about Victorianart movements while writing Child of Light, like the Pre-Raphaelites,Aestheticism, and Art Nouveau as well as burgeoning Impressionism, mirrored byphrasing and the use of Debussy's Clair de lune throughout.

15- What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply yourlife outside of your work?

Oh, somany. I love Carole Maso, Thalia Field,Salvador Plascencia, Vi Khi Nao. KurtVonnegut has been my hero since I was twelve. I'm a Vonnegut expert. I love Charles Baudelaire, Rainer Maria Rilke,Amiri Baraka, Federico Garcia Lorca. Finding Peter Weiss was revelatory for me. So many.

16- What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

I'dlike to film a full-length movie, probably from one of my plays.

17- If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or,alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been awriter?

Theother jobs I want would be like winning the lottery—I'd love to be a filmmakeror a curator in an art museum. In morerealistic alternatives, I think I would be a good support worker or autismadvocate.

18- What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

Iwrite, but I also paint, I make short films, I draw. I'm an artist so I try out any medium thatinterests me. But I think I keep comingback to writing because it lets me think. I feel like I can produce a morenuanced message in this form. I can getclose to expressing what I mean.

19- What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

I havejust re-read one of my favorite books of all time, Defiance by CaroleMaso, for my book club. I also read anincredible graphic novel from Fantagraphics, The N-Word of God by MarkDoox. I've seen several great movieslately, too—Downfall has incredible casting (and is timely). Sinners was beautiful and refreshing and Ireally enjoyed The Last Showgirl, too. Pam Anderson does a wonderful job and I liked her character's complexityand single-minded approach to art.

20- What are you currently working on?

I'mworking on finishing up a folk horror novel about Grace Brown. Hopefully, there'll be a first draft by theend of the year.

September 6, 2025

Melanie Dennis Unrau, Goose

Goose is a work of research-creation that blendsresearch, literary criticism, and poetics. My tracing method pulls at and drawsout threads of ideology, power, subversion, and contradiction in NorthlandTrails, sidelining its more overt or obvious content to pay attention toits underlying assumptions and aesthetics, along with the things it tries tohide or contain. Goose interprets Northland Trails by following asuccession of clues, hunches, and ideas, driven not by the need to prove thatthey are correct but rather to ask, only ever half seriously, what if theywere? Looking for geese in Northland Trails leads to looking fordissenting perspectives and voices more generally. It loosens Ells’s grip ongeese as metaphor or pathetic fallacy, creating space for geese—along withother northern beings, including Indigenous peoples, non-human animals, and theland itself—to exist beyond and in resistance to the uses Ells puts them to. Asa deconstructive project working on and against settler-colonial ideology, Gooseseeks, holds space for, and invites readers to investigate Indigenous anddecolonial counternarratives to Northland Trails. (“AFTERWORD”)

FromWinnipeg poet, editor and scholar Melanie Dennis Unrau comes the debutfull-length poetry title,

Goose

(Picton ON: Assembly Press, 2025), abook-length visual poem project (an excerpt of which also appeared as a chapbook through above/ground press a while back, as well as through the Spotlight series) of simultaneous excavation and erasure that emerges from thework of “Canadian Development of Mines expert and Word War I veteran” Sidney Clarke Ells (1878-1971), the self-declared “father of the tar sands,” specifically his1938 collection of poems, short stories and essays, Northland Trails(1938). Through an expansive visual sequence, Unrau works her project as one ofcritical response, working to engage with and, specifically, against theoriginal intent of Ell’s language back into itself, and the implications ofwhat those original intents have wrought. The book is set with an afterword bythe author, and an opening “FOREWORD” by McMurray Métis, that opens: “There isa long history in Canada and indeed across the world of European ‘explorers’appropriating the knowledge, skills, and labour of Indigenous peoples for theirpersonal and collective gain, only to tur around and declare the territories ofIndigenous peoples ‘terra nullius,’ and their cultures and ways of liveinferior and unworthy of respect. This dialectic of appropriation-negation isfamiliar to Indigenous people across the globe. And so it is with Fort McMurray,its oil sands, and their ‘father,’ Sidley Ells. Through research, community andpublic awareness, and the construction of our cultural centre, McMurray Métishope to correct these self-serving and distorted narratives, and assert ourhistoric and continued presence, way of life, and self-determination. Let this forewordbe one small step in that direction.”

FromWinnipeg poet, editor and scholar Melanie Dennis Unrau comes the debutfull-length poetry title,

Goose

(Picton ON: Assembly Press, 2025), abook-length visual poem project (an excerpt of which also appeared as a chapbook through above/ground press a while back, as well as through the Spotlight series) of simultaneous excavation and erasure that emerges from thework of “Canadian Development of Mines expert and Word War I veteran” Sidney Clarke Ells (1878-1971), the self-declared “father of the tar sands,” specifically his1938 collection of poems, short stories and essays, Northland Trails(1938). Through an expansive visual sequence, Unrau works her project as one ofcritical response, working to engage with and, specifically, against theoriginal intent of Ell’s language back into itself, and the implications ofwhat those original intents have wrought. The book is set with an afterword bythe author, and an opening “FOREWORD” by McMurray Métis, that opens: “There isa long history in Canada and indeed across the world of European ‘explorers’appropriating the knowledge, skills, and labour of Indigenous peoples for theirpersonal and collective gain, only to tur around and declare the territories ofIndigenous peoples ‘terra nullius,’ and their cultures and ways of liveinferior and unworthy of respect. This dialectic of appropriation-negation isfamiliar to Indigenous people across the globe. And so it is with Fort McMurray,its oil sands, and their ‘father,’ Sidley Ells. Through research, community andpublic awareness, and the construction of our cultural centre, McMurray Métishope to correct these self-serving and distorted narratives, and assert ourhistoric and continued presence, way of life, and self-determination. Let this forewordbe one small step in that direction.”Visuallyexpansive, with a delightful use of image and space, Unrau moves through the language,sketches and, seemingly, the typeface, of Ells’ 1938 collection to unravel anacknowledgment of the Indigenous peoples within that space, and the environmentand landscape of those pilfered, poisoned lands, showcasing the illusion ofself that Ells presumed upon that landscape, flipping a script of belongingthat was never his to take. “Inspired by books like Jordan Abel’s The Placeof Scraps, M. NourbeSe Phillip’s Zong!, Syd Zolf’s Janey’s Arcadia,Shane Rhodes’s Dead White Men, and Lesley Battler’s Endangers Hydrocarbons,”Unrau writes, as part of the book’s “AFTERWORD,” “I started to make visualpoetry out of found text and images from Northland Trails. After someexperimentation, I developed a method of building poems and critical argumentsabout Northland Trails by tracing words and illustrations from itspages.”

September 5, 2025

Bloodletting: poems by Kimberly Reyes

Had we made it past theheat,

the honey,

we could have thawedsemi-sweet

& ekphrastic, wakingto rewatch

our black & whitefilm,

retracing lines ofdialogue

as we stumble

over cryonic sieves

of affection

in a quell we’d callhistory,

cold fidelity,

as we’d learn new ways

to hate &hard-swallow,

embalming the savor

of when we were present—

an oiled kernel,

a muscle pre-spasm—

forever technicolor

Recentlyin my mailbox landed “poet, essayist, teacher, pop culture scholar, 2ndgeneration NYer” Kimberly Reyes’ third full-length collection,

Bloodletting:poems

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2025), following the incredible debut Runningto Stand Still (Omnidawn, 2019) and

vanishing point.

(Omnidawn,2023) [see my review of such here]. Bloodletting explores andarticulates a distillation of pop culture and violence both global and localizedacross sharp lyric, writing counterpoints and contradictions across the presentmoment of the American landscape—Taylor Swift and the devastation of Gaza,TikTok videos, femicide and the male gaze, Golems and smartphones—somehow allprovided equal weight through mainstream culture. “gave her everything he’dprevious withheld / from the women / who looked like the women / whose scarred,arched backs / he leapfrogged / on his way / to the Capital.” she writes, aspart of the extended title poem. “He chose violence, / casual warfare, / firingup all manner of ballistics: / indifference, carcass, cruelty… [.]” Offeringsharp observation and distillation, Reyes asks the reader to question what storiesget told and by whom, and what might this end up doing to our attention. As shewrites, mid-way through the collection: “The rage of one person can becataclysmic.”

Recentlyin my mailbox landed “poet, essayist, teacher, pop culture scholar, 2ndgeneration NYer” Kimberly Reyes’ third full-length collection,

Bloodletting:poems

(Oakland CA: Omnidawn, 2025), following the incredible debut Runningto Stand Still (Omnidawn, 2019) and

vanishing point.

(Omnidawn,2023) [see my review of such here]. Bloodletting explores andarticulates a distillation of pop culture and violence both global and localizedacross sharp lyric, writing counterpoints and contradictions across the presentmoment of the American landscape—Taylor Swift and the devastation of Gaza,TikTok videos, femicide and the male gaze, Golems and smartphones—somehow allprovided equal weight through mainstream culture. “gave her everything he’dprevious withheld / from the women / who looked like the women / whose scarred,arched backs / he leapfrogged / on his way / to the Capital.” she writes, aspart of the extended title poem. “He chose violence, / casual warfare, / firingup all manner of ballistics: / indifference, carcass, cruelty… [.]” Offeringsharp observation and distillation, Reyes asks the reader to question what storiesget told and by whom, and what might this end up doing to our attention. As shewrites, mid-way through the collection: “The rage of one person can becataclysmic.”ThroughReyes, text fades and rages, overlaps and is crossed out. “pain is personal andruns parallel,” she writes further through her title poem, “and relative / and// I have no idea what to live for if not love.” This is a complex, devastatingand propulsive collection of poems fully able to simultaneously live within andrespond to the present moment, in remarkable ways. She cuts through the noise, thebluster, and gets to the heart of it, providing clarity and clear resistance. Asthe opening poem “Red” ends: “The shit’s been building for millennium ///////—lean in.”

September 4, 2025

Spotlight series #113 : Christina Shah

The one hundred and thirteenth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring

New Westminster, British Columbia poet Christina Shah.

The one hundred and thirteenth in my monthly "spotlight" series, each featuring a different poet with a short statement and a new poem or two, is now online, featuring

New Westminster, British Columbia poet Christina Shah.The first eleven in the series were attached to the Drunken Boat blog, and the series has so far featured poets including Seattle, Washington poet Sarah Mangold, Colborne, Ontario poet Gil McElroy, Vancouver poet Renée Sarojini Saklikar, Ottawa poet Jason Christie, Montreal poet and performer Kaie Kellough, Ottawa poet Amanda Earl, American poet Elizabeth Robinson, American poet Jennifer Kronovet, Ottawa poet Michael Dennis, Vancouver poet Sonnet L’Abbé, Montreal writer Sarah Burgoyne, Fredericton poet Joe Blades, American poet Genève Chao, Northampton MA poet Brittany Billmeyer-Finn, Oji-Cree, Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer from Peguis First Nation (Treaty 1 territory) poet, critic and editor Joshua Whitehead, American expat/Barcelona poet, editor and publisher Edward Smallfield, Kentucky poet Amelia Martens, Ottawa poet Pearl Pirie, Burlington, Ontario poet Sacha Archer, Washington DC poet Buck Downs, Toronto poet Shannon Bramer, Vancouver poet and editor Shazia Hafiz Ramji, Vancouver poet Geoffrey Nilson, Oakland, California poets and editors Rusty Morrison and Jamie Townsend, Ottawa poet and editor Manahil Bandukwala, Toronto poet and editor Dani Spinosa, Kingston writer and editor Trish Salah, Calgary poet, editor and publisher Kyle Flemmer, Vancouver poet Adrienne Gruber, California poet and editor Susanne Dyckman, Brooklyn poet-filmmaker Stephanie Gray, Vernon, BC poet Kerry Gilbert, South Carolina poet and translator Lindsay Turner, Vancouver poet and editor Adèle Barclay, Thorold, Ontario poet Franco Cortese, Ottawa poet Conyer Clayton, Lawrence, Kansas poet Megan Kaminski, Ottawa poet and fiction writer Frances Boyle, Ithica, NY poet, editor and publisher Marty Cain, New York City poet Amanda Deutch, Iranian-born and Toronto-based writer/translator Khashayar Mohammadi, Mendocino County writer, librarian, and a visual artist Melissa Eleftherion, Ottawa poet and editor Sarah MacDonell, Montreal poet Simina Banu, Canadian-born UK-based artist, writer, and practice-led researcher J. R. Carpenter, Toronto poet MLA Chernoff, Boise, Idaho poet and critic Martin Corless-Smith, Canadian poet and fiction writer Erin Emily Ann Vance, Toronto poet, editor and publisher Kate Siklosi, Fredericton poet Matthew Gwathmey, Canadian poet Peter Jaeger, Birmingham, Alabama poet and editor Alina Stefanescu, Waterloo, Ontario poet Chris Banks, Chicago poet and editor Carrie Olivia Adams, Vancouver poet and editor Danielle Lafrance, Toronto-based poet and literary critic Dale Martin Smith, American poet, scholar and book-maker Genevieve Kaplan, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic ryan fitzpatrick, American poet and editor Carleen Tibbetts, British Columbia poet nathan dueck, Tiohtiá:ke-based sick slick, poet/critic em/ilie kneifel, writer, translator and lecturer Mark Tardi, New Mexico poet Kōan Anne Brink, Winnipeg poet, editor and critic Melanie Dennis Unrau, Vancouver poet, editor and critic Stephen Collis, poet and social justice coach Aja Couchois Duncan, Colorado poet Sara Renee Marshall, Toronto writer Bahar Orang, Ottawa writer Matthew Firth, Victoria poet Saba Pakdel, Winnipeg poet Julian Day, Ottawa poet, writer and performer nina jane drystek, Comox BC poet Jamie Sharpe, Canadian visual artist and poet Laura Kerr, Quebec City-area poet and translator Simon Brown, Ottawa poet Jennifer Baker, Rwandese Canadian Brooklyn-based writer Victoria Mbabazi, Nova Scotia-based poet and facilitator Nanci Lee, Irish-American poet Nathanael O'Reilly, Canadian poet Tom Prime, Regina-based poet and translator Jérôme Melançon, New York-based poet Emmalea Russo, Toronto-based poet, editor and critic Eric Schmaltz, San Francisco poet Maw Shein Win, Toronto-based writer, playwright and editor Daniel Sarah Karasik, Ottawa poet and editor Dessa Bayrock, Mahone Bay, Nova Scotia poet Alice Burdick, poet, writer and editor Jade Wallace, San Francisco-based poet Jennifer Hasegawa, California poet Kyla Houbolt, Toronto poet and editor Emma Rhodes, Canadian-in-Iowa writer Jon Cone, Edmonton/Sicily-based poet, educator, translator, researcher, editor and publisher Adriana Oniță, California-based poet, scholar and teacher Monica Mody, Ottawa poet and editor AJ Dolman, Sudbury poet, critic and fiction writer Kim Fahner, Canadian poet Kemeny Babineau, Indiana poet Nate Logan, Toronto poet and editor Michael Boughn, North Georgia poet and editor Gale Marie Thompson, award-winning poet Ellen Chang-Richardson, Montreal-based poet, professor and scholar of feminist poetics, Jessi MacEachern, Toronto poet and physician Dr. Conor Mc Donnell, San Francisco poet Micah Ballard, Montreal poet Misha Solomon, Ottawa writer and editor Mahaila Smith, American poet and asemic artist Terri Witek, Ottawa-based freelance editor and writer Margo LaPierre, Ottawa poet Helen Robertson and Oakville poet Mandy Sandhu!

The whole series can be found online here .

September 3, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Robert van Vliet

Robert van Vliet

grew up in the Twin Cities and spentmany years living in lots of other places. His poetry has appeared in TheSixth Chamber Review, Autumn Sky Poetry Daily, Guesthouse, Otoliths, andelsewhere. He is the author of the chapbook, This Folded Path,(above/ground press, 2023) and

Vessels

(Unsolicited Press, 2024). Helives in Saint Paul, Minnesota, with his wife, Ana.

Robert van Vliet

grew up in the Twin Cities and spentmany years living in lots of other places. His poetry has appeared in TheSixth Chamber Review, Autumn Sky Poetry Daily, Guesthouse, Otoliths, andelsewhere. He is the author of the chapbook, This Folded Path,(above/ground press, 2023) and

Vessels

(Unsolicited Press, 2024). Helives in Saint Paul, Minnesota, with his wife, Ana.1 - How did your first book or chapbook change your life?How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feeldifferent?

I’m not sure my life has changed all that much, really.My daily life as a writer is exactly the same as it ever was. I’m still askingmyself, What the hell am I doing? How am I doing it? Is this a poem? Is itfinished? Do I try to put it out into the world, or just put it in a drawer?I write because I write. I share the results of my work when I can, but if Ididn’t enjoy simply sitting in a room banging words around, then I would havemoved on to something else by now.

As for how the poems in This Folded Path and Vesselscompare to my previous work, they were all composed over a fairly brief periodof time, using a very specific set of constraints, which I think gave them agreater unity of tone and character. I had never sustained such a focused aproject like this for such a length of time so, even though I’m sure they beara resemblance to older poems, they mark the deepest dive into a particular setof “theoretical concerns” (see below) that I’ve ever consciously, deliberatelymaintained.

Oh okay, y’know, now that I’ve been thinking about it,maybe my debut chapbook and debut full-length (which were accepted forpublication within weeks of each other after about fourteen years of submittingmanuscripts to presses with no success) actually did kinda change my life:Having them published was a startling and unprecedented recognition of the workI do.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say,fiction or non-fiction?

Of all the various artistic pursuits that I’ve blunderedthrough, poetry was the very last. The first writing I was drawn to wasfiction, all the way back in elementary school. I goofed around with poetry inhigh school, but I never quite took it seriously until after I began writingsongs in college. Eventually, and rather unconsciously, poetry eclipsedsongwriting and fiction.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writingproject? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Dofirst drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work comeout of copious notes?

Because I have a regular (though not always daily)practice of “doodling” in a notebook, I’m never short of raw materials fromwhich to build poems. In fact, I probably have more raw material than I’ll everbe able to process. All too often, I fail to revisit what I’ve written, optinginstead to keep moving forward with new things. I have several bankers boxes ofspiral notebooks that still need to be looked through. And I recently uncovereda manuscript of several hundred prose poems I wrote about twenty years ago andthen promptly forgot about.

I’ve always been pretty quick with the first drafts, buthow long it takes to arrive at something resembling a final draft has variedwildly over the years. Sometimes I’ve just dropped the thing as soon as it felteven slightly “coherent,” while other times I’ve rewritten something a dozentimes or more, playing with different line breaks, swapping words over and overlike lens settings at the optometrist. On and on. For a long time, I wouldthrow fragments together and then come up with connecting tissue to bridge thegaps. But sometimes I would just leave the gaps. (Less “first thought bestthought” and more “no thought best thought.”

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you anauthor of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are youworking on a “book” from the very beginning?

Poems usually begin with scraps of sounds or some sort oflanguage game. The larger project, if there is one, almost always emerges afterat least some, if not all, of the poems have already been written. I have, fromtime to time, written with larger projects in mind, but I don’t think I’ve everstarted with the goal of “writing a book.”

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to yourcreative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

Public readings aren’t exactly part of my process, butthe performative aspect of poetry is very important to me, and I always writewith an ear for how a poem might sound when read aloud. I came to poetry fromthe performing arts (theater and music) so I’ve always thought of the text of apoem as somewhat analogous to a script or score, and that the reading of thetext (aloud or otherwise) is part of what completes the work. This also meansthat I don’t think that my performance of one of my poems is canonical:It’s perfectly likely that someone else might be better at interpreting thetext. And yes, I enjoy doing readings.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind yourwriting? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? Whatdo you even think the current questions are?

I think I probably do have theoretical concerns, butthere’s a sign over my desk that reads: “The work speaks for itself.” This, tome, means that anything I might say about my work would be something like aparaphrase — and I don’t believe art can be paraphrased because I don’t believeart is necessarily trying to say anything. And I certainly don’t think I am agreater authority on my own work than anyone else, so my own theoreticalconcerns are unlikely to shed any valuable light on it. I’d be much more interestedin hearing about what someone else sees in my work.

And, assuming that speaking of art in terms of“questions” and “answers” has any usefulness or validity at all, I think I’mmuch more interested in figuring out how exactly to ask the questions, becauseif we don’t understand our questions, we definitely won’t understand whateveranswers we might stumble upon.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer beingin larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of thewriter should be?

To consider other possibilities; to question the simpleand the seemingly obvious; to reveal the strange within the familiar, and thefamiliar within the strange. No writer should insult anyone’s intelligence, butevery writer must constantly challenge the willfully ignorant.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outsideeditor difficult or essential (or both)?

Essential. I’ve been lucky so far that the editors I’veworked with had a very light hand, and my work passed through them and intoprint with very little in the way of corrective surgery. I’d like to think thisis partly because I’ve worked as an editor myself and I try to hand in as cleana copy as possible. I’ve welcomed and generally enjoyed working with editors;and I would have been open to considering substantial edits or revisions thathelped clarify the work. It is the mark of an insecure, immature writer whoresists any editorial input. No one’s perfect, and nothing exists in isolation.Everything is connected to everything else, so how others react to your work:that’s everything. Why wouldn’t you want to have an early sense of how yourwork might be interpreted or misunderstood?

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (notnecessarily given to you directly

Trust your luck, but don’t forget to put our your nets.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, ordo you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

Early mornings are generally the best time for me towrite, so I try to wake up early enough to give myself a good stretch beforethe day starts its supplications. But it isn’t unwaveringly consistent. And inthe last two or three years, it’s been annoyingly sporadic. Depending on myother work commitments, I might snatch twenty minutes around lunchtime or inthe late afternoon. Mostly, I just try to make sure I’m leaving at least alittle time each day fenced off from other concerns.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn orreturn for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

The only times I’ve ever felt genuinely stalled hadnothing to do with the writing itself and everything to do with work or lifecommitments monopolizing my attention and energy. As long as I’ve been able tocarve out a little time, I’ve been able to get back into it fairly easily.

But I should add that sometimes the blank page can be alittle intimidating, especially if I’m coming back to writing after what feelslike a long while (days, months, whatever). So I’ll tell myself I’m justfooling around, that it’s no big deal. I let myself off the hook by spending mywriting time simply describing whatever I’m seeing or hearing. Crows, clouds,coffee mug, whatever. Just any stupid shit that tumbles out. Now there’s somedumb writing on the page, something has begun, and I have a baseline ofmediocre to surpass.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

Cold air over snow with a note of thaw to it. Also, loamyair through the metallic tang of a window screen after a thunderstorm.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come frombooks, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature,music, science or visual art?

Music, definitely. Also history, archaeology, comparativereligion, and psychology.

14 - What other writers or writings are important foryour work, or simply your life outside of your work?

I kind of dread being asked this sort of question. I’mcertain I’ll forget someone, or I secretly worry that I’ll include someonewho’s less of an influence and more of a name-drop, just to seem cooler than Iam. (I am, in fact, not remotely cool.) But the fact is, when I was younger,this was the way I made discoveries: writers mentioning their favorite books orbiggest influences, etc.

So in that spirit, here’s a laughably incomplete list, inno particular order, of a few books and writers that have, at one time oranother, been enormously important and influential to me and the kind of work Itry to do:

Maxine Hong Kingston’s Tripmaster Monkey, AnnieDillard’s Holy the Firm, John Cage, Elaine Pagels, Douglas Hofstadter’s MetamagicalThemas, Robert Bringhurst (both as typographer and poet), the Copper Canyonanthology A Gift of Tongues, Jung’s alchemical writings, Tom Phillips’ AHumument, Thoreau, Epictetus, Han Shan, Guy Davenport, Thomas Pynchon, Morgan’sTarot, Richard Brautigan’s In Watermelon Sugar, William James’ Varietiesof Religious Experience, Judith Sklar’s Ordinary Vices, Mary Midgley, Russell Hoban (especially The Medusa Frequency and Kleinzeit),Arthur Sze, Hayden Carruth, Joanne Kyger, Jim Harrison, Muriel Rukeyser, Odd Bodkins, Victor Mair’s translation of the Tao Te Ching.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven’t yet done?

Live above the Arctic Circle for a year.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt,what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended updoing had you not been a writer?

Anthropologist or paleontologist. And if I weren’t awriter, I probably would have ended up being a writer.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing somethingelse?

I love playing with pencils and I love how paper takesink. I also love letter forms and typefaces. A writer is also, among otherthings, a performance artist, comedian, philosopher, musician, seer, andscientist, so writing is doing something else. Also, I like sentences.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was thelast great film?

The Dawn of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow.

I haven’t been much of a film person recently. I’m mostlywatching harmless, heavily formulaic police procedurals, cozy murder mysteries,or old familiar TV shows that I’ve already seen many times. Oh, but I finallysaw La Jetée for the first time last year and it lived up to, orpossibly exceeded, its reputation.

19 - What are you currently working on?

I’ve been working on getting all the books out of mybasement office and onto shelves upstairs after we had some minor but deeplyunsettling flooding problems. Books, it turns out, are heavy and I regret nothaving bought a house with an elevator or dumb waiter or something.

Oh, you mean like writing and stuff? Well, I recentlyfinished some of the first poems I’ve written in a few years. As I was editingand revising them, I was trying to discern whether they were a small collectionof thirty stand-alone things or the beginning of a new, very long project. (Orboth.)

By “very long” I mean that if I were to follow the recipethat built the first thirty poems through some chance operations, I would beembarking on a series that would run to a total of 2,156 poems. But if you’reon a vast mosaic floor, and you wish to step on each tile only once, chancecan’t help you: you will almost certainly select the same tile again,potentially many times, unless you remove it from the pool of options somehow.I finally struck on the solution of using a Knight’sTour that stitches togethereleven 14x14 boards to determine my route, step by step, through the sourcematerial. Good grief, randomness takes so much planning! But now the path knowswhere I’m going, but I don’t. Perfect!

So I guess I have my work cut out for me — right after Ifinish loading the new bookshelves in the living room.

September 2, 2025

Es Lv, footprints

Everything people sayabout owls is a lapse because everything they say

Comes from reading or hearsaybut owls do not live in information or other

People, owls live inhollows inside this shell there isnothing

Inside this shell isnothing, all sound of ocean everything I say is

A lie because everything Isay comes from the same source as what they say

I am disorder I am on theside of disorder, the theoretical end of entropy

Is uniformity everything I write is true becauseeverything I write

Comes from my life thatis a nontransferable path no one else can live it

Not any better or any worse lack of proof is the fatal flaw of

Retroactive manifestos I canknow how things happen but never quite the

What or why inhistories untended hedges stragglyoleander bushes

Cement walls with bits ofcolored tile pots in a similar style with tangles

(“NO ONE ELSE CAN LIVE MY LIFE”)

Iwas intrigued to discover this new full-length poetry title by the mysterious EsLv, the book

footprints

(Brooklyn NY: ugly duckling presse, 2025), atitle physically set as a graceful square, due to the lengths of the lines. Despitebeing less than one hundred pages, footprints feels an expansive text;so big it nearly overwhelms. Only by entering the collection can one see theforest for the trees. “The violence is fresh today.” writes the poem “COMMODITIES,”“There is no need / for spices.” The poems in footprints collect into anassemblage of lyric expansiveness across poems set in four quarters, includinga section-length sequence. There isn’t anything within the book that providesdetails on the author themselves, but for a couple of threads in the acknowledgements,including “My relationships with the words in this book became poems slowly.” and“The labor and artistry that transformed my manuscript into this book are akind that effaces itself, making effort look easy or special efforts go unnoticed.”and “Every poem in this book was made with other wayfinders, authors whosewords and trailwork found me when I was looking for them, star patterns,swells, color of clouds, my origin.” There is a charming and wistful sense of appreciationin these lines for the almost mystical knowing and unknowing that makeswriting, specifically their writing, possible. As far as author biography, the publisher’s website offers only this: “Es Lv’s poems are invitations to build together,connections and worlds. Born into a Taiwan under martial law, they have livedmany places and many roles. In art framing, in solidarity movements, inseasonal work, and many others. In her writing live those nested sensibilities,exhaustion and possibilities beyond, and the camaraderie. And much luck.”

Iwas intrigued to discover this new full-length poetry title by the mysterious EsLv, the book

footprints

(Brooklyn NY: ugly duckling presse, 2025), atitle physically set as a graceful square, due to the lengths of the lines. Despitebeing less than one hundred pages, footprints feels an expansive text;so big it nearly overwhelms. Only by entering the collection can one see theforest for the trees. “The violence is fresh today.” writes the poem “COMMODITIES,”“There is no need / for spices.” The poems in footprints collect into anassemblage of lyric expansiveness across poems set in four quarters, includinga section-length sequence. There isn’t anything within the book that providesdetails on the author themselves, but for a couple of threads in the acknowledgements,including “My relationships with the words in this book became poems slowly.” and“The labor and artistry that transformed my manuscript into this book are akind that effaces itself, making effort look easy or special efforts go unnoticed.”and “Every poem in this book was made with other wayfinders, authors whosewords and trailwork found me when I was looking for them, star patterns,swells, color of clouds, my origin.” There is a charming and wistful sense of appreciationin these lines for the almost mystical knowing and unknowing that makeswriting, specifically their writing, possible. As far as author biography, the publisher’s website offers only this: “Es Lv’s poems are invitations to build together,connections and worlds. Born into a Taiwan under martial law, they have livedmany places and many roles. In art framing, in solidarity movements, inseasonal work, and many others. In her writing live those nested sensibilities,exhaustion and possibilities beyond, and the camaraderie. And much luck.” “Whymight a person change their name.” asks the opening of the poem “STRANGE IFTHERE WERE NONE FOR US,” a poem that also offers, further along: “It isn’t alie. right now we’re living / In a world where anyone with any motive at allcan come / In anywhere at any time in any manner. / It’s the lack of policythat creates / Chaos. theoretical physics chaos is efficient. / The events oflast night / No longer exist. it’s more of a story [.]” The shift incapitalization adds for an interesting alteration of rhythms, although forthese poems, propulsion is key, and the poems are hefty: not only are they footprints,set as a kind of witness or demarcation of where one has been, but an ongoinglist of considerations for possibility, and directions still to come. “Have asense of self,” the poem “NO ONE ELSE CAN LIVE MY LIFE” writes, further on, “godsand heroes are strictly / For the masses is it fairer that you obey nature / Or that nature should obey you incommunicable / Language used forcommunication with individual persons / Will not contain other forms ofrelationship [.]” The poems, individually and as a single unit, exist asmonologues; poems that feel as performative as they do meditative, and set onthe page; sweeping gestures of line and length and sound. “History is not aboutthe past this story my story is aboutthe present and / what i choose to do with it,” they write, mid-through thecollection, “My lived experiences are my most precious credentials / If i wanta better world i will have to be a better person // If we want a better worldwe will have to be better people [.]”

September 1, 2025

Gillian Sze, An Orange, A Syllable

My comparison of languageacquisition to some train, some countable linearity, is embarrassingly wrong. Babylanguage, I soon found out, was catachrestic. The child’s speech laid bareassociations and accidents. In the tub, she would point to the eye of the toywhale and say, Moon. She would clamber up the stepstool and say, Tree.And when the child pointed to the cracks in the floorboards, she would say, Hole,followed by, Ow. Point to the hole in my sock and say, Hole. Pointto the circles in the rug and say, Hole. Ow. All was lace. From thechild’s small mouth, she undid the world around me.

Havingbeen startled by how quietly good I thought her prior title,

quiet nightthink: poems & essays

(Toronto ON: ECW Press, 2022) [see my review of such here], I was intrigued to see Montreal poet Gillian Sze’s latest, thepoetry collection

An Orange, A Syllable

(ECW Press, 2025). As quietnight think: poems & essays was a blend of meditative, first person lyricprose and poems around the swirls and reconsiderations of self, culture andbeing that accompanied her new motherhood, this latest shifts those leaningsback into the shape and approach of the poem a bit further down Sze’s narrative/parentingline. This is very much a sequel to that prior collection, offering furtherinsights into culture, language, self and possibility through the ongoing lensof motherhood, partnership and domestic patter. “What were your words when thehome was at a standstill? My love / is limited. The last dish fell from a cupboard.At a talk about love, a / scholar spoke about agape. I never consideredthe ordered and clean / conditions of agape, the superior, transcendent, unconditionallove. I / did not know it.”

Havingbeen startled by how quietly good I thought her prior title,

quiet nightthink: poems & essays

(Toronto ON: ECW Press, 2022) [see my review of such here], I was intrigued to see Montreal poet Gillian Sze’s latest, thepoetry collection

An Orange, A Syllable

(ECW Press, 2025). As quietnight think: poems & essays was a blend of meditative, first person lyricprose and poems around the swirls and reconsiderations of self, culture andbeing that accompanied her new motherhood, this latest shifts those leaningsback into the shape and approach of the poem a bit further down Sze’s narrative/parentingline. This is very much a sequel to that prior collection, offering furtherinsights into culture, language, self and possibility through the ongoing lensof motherhood, partnership and domestic patter. “What were your words when thehome was at a standstill? My love / is limited. The last dish fell from a cupboard.At a talk about love, a / scholar spoke about agape. I never consideredthe ordered and clean / conditions of agape, the superior, transcendent, unconditionallove. I / did not know it.”An Orange, A Syllable is built as an accumulationof lyric prose blocks, seventy-six in sequence. Occasionally there might be asymbol set atop one of these blocks, as to suggest a new line of thinking, anew sequence or cluster, five in total across the collection. Throughout, Szewrites of love, of language and the new ways she’s learned to approach and encounter,both within and beyond a domestic space that almost sounds set within theCovid-19 era: “What is out there? I think I have forgotten. My world thicksdown / to the sweetness in each fold of laundry. The growing tower of cotton, /tidy and eversteady. For a while, I can stop thinking and let the hands /spread across the sleeves, the hems, the stitches. The hands know where / smoothnessis right, know where to put the parts and when the folds / are finished.” Again,as a furthering of her prior collection, Sze writes of engaging language, herown background and self in new ways, engaging with the immediacy, and thelayers one gains through attempting to communicate such to one’s children (withfamiliar echoes, certainly, of my own accumulation, through the book of smaller, of prose poems through and amid a similar period of domestic,parenting small children). To attempt to speak on any of this requires one’sown understanding, after all. This is a sharp and meaningful collection, andreason, once more, to go through that prior collection as well.

Dougong is an ancientChinese method of interlocking wood. Watchtowers and temples and dynasties havebeen built completely without bolts, screws, or nails. All the wooden parts—beams,brackets, pillars—fit with precise carpentry. A dialogue, too, is putting apicture together, closing all the gaps. When one speaks and the other replies,words snap together. Meanings are understood and there is a satisfying “click.”

August 31, 2025

12 or 20 (second series) questions with Jordan Stempleman

Jordan Stempleman

is the author of the forthcoming poetry collection

Spilt

, awarded the 2025 Wishing Jewel Prize from Green Linden Press. He has also published nine previous poetry collections, including

Cover Songs

(The Blue Turn),

Wallop

, and

No, Not Today

(Magic Helicopter Press). Stempleman is the editor of

Windfall Room

and faculty advisor for the Kansas City Art Institute's literary arts journal

Sprung Formal

. From 2011 to 2025, he curated the A Common Sense Reading Series in Kansas City, Missouri, and from 2007 to 2025, he served as co-editor of

The Continental Review

, one of the longest-running online literary magazines devoted to video poetics.

Jordan Stempleman

is the author of the forthcoming poetry collection

Spilt

, awarded the 2025 Wishing Jewel Prize from Green Linden Press. He has also published nine previous poetry collections, including

Cover Songs

(The Blue Turn),

Wallop

, and

No, Not Today

(Magic Helicopter Press). Stempleman is the editor of

Windfall Room

and faculty advisor for the Kansas City Art Institute's literary arts journal

Sprung Formal

. From 2011 to 2025, he curated the A Common Sense Reading Series in Kansas City, Missouri, and from 2007 to 2025, he served as co-editor of

The Continental Review

, one of the longest-running online literary magazines devoted to video poetics.1 - How did your first book change your life? How does your most recent work compare to your previous? How does it feel different?

It meant a kind of seriousness, I think. A devotion beyond the statement, the feeling, perhaps, of “I’m telling you, I’m a poet.” My first book, Their Fields , was a book-length poem, the first time I’d ever written anything past a couple of pages or so. The doing of something this long felt vastly different than anything I thought I could endure. Writing has never been something that I find settling or enjoyable while I’m actively doing it. This struggle, an almost anti-flow state, continues until I’m near the end of the drafting process, and then it’s the reading and re-reading that reveal the poem, which then compels me to write the next one. My work now is very much doing what my work from 30 years ago was doing: feeling it all out. Putting it all together, or nearly together, or with the potential of togetherness, and then applying a different mode of attention that stares into what’s now there.

The fact that I write poetry has changed my life. It’s a means of being with language as much as outside of the poem as within it.

2 - How did you come to poetry first, as opposed to, say, fiction or non-fiction?

The first poems I wrote, outside of any classroom assignment in school, were about being dumped, total heartbreak. I was seeing, I think, what was beyond the ache of excess feeling. I also think I turned to poetry initially because it felt like the bookish response to music, especially the kind I was drawn to in my teens: CRASS, The Cure, Dead Kennedys, Descendants, Bauhaus, Fugazi, etc. I loved how poetry could channel these excess states of feeling, political repulsion, without even knowing three chords, just the voice and the page. This felt attainable to me and aligned with my immersion in music.

3 - How long does it take to start any particular writing project? Does your writing initially come quickly, or is it a slow process? Do first drafts appear looking close to their final shape, or does your work come out of copious notes?

Rarely does it come quickly. As I mentioned, it’s typically a slog. To mitigate this, I am always trying to accumulate notes and fragments in my phone or give myself constraint-based exercises to generate at least a base layer that has the potential to develop into something down the road. In my poetry workshops, I always show this short video where I started recording my laptop screen after I was finally done drafting a shorter poem, like 18 lines, a poem that I never hit “save” on so I could then hit “undo,” taking the poem all the way back to the blank Word document. The recording states there, so the students can see what line came from my journal to the page, how I left so many awful lines in there for ages because I thought they were incredible or necessary, or just the fact that I spent half a day drafting them. I go bit by bit, trying to add narration to my decision process, noting how the parts become the poem through thousands of decisions.

4 - Where does a poem usually begin for you? Are you an author of short pieces that end up combining into a larger project, or are you working on a "book" from the very beginning?

Often, I can sense when a poem will evolve into its own thing: a longer sequence, a series, or a stand-alone piece. I’ve never written a “project.” I write and let the poem do what it wants to do. This is probably why I never had a deep interest in being a fiction writer. What does DeLillo write in White Noise? “To plot is to live.” Or is it, “To plot is to die”? I am awful at engineering plots. I would much rather play and struggle on the page, and see what comes of it after the fact.

5 - Are public readings part of or counter to your creative process? Are you the sort of writer who enjoys doing readings?

I do enjoy readings. I love hearing other poets read their work. I often get a better editorial ear when reading my newer work aloud. However, even the published work becomes more accessible, less unknown, when I read it alone in my house a thousand times, and even more so when I read it a few times in public.

6 - Do you have any theoretical concerns behind your writing? What kinds of questions are you trying to answer with your work? What do you even think the current questions are?

I know I’m always drawn to the epistemological and phenomenological, but expressed or released in everyday environments. I am all about the local. It’s the closeness of where I’m at that seems most estranged for me, and I think being here makes me less preposterous in my political sensibilities. I think having an openness to the messes we’re most in are the messes that we make or that are five feet from us. The same with the overlooked beauty and goodness.

7 – What do you see the current role of the writer being in larger culture? Do they even have one? What do you think the role of the writer should be?

Just try to leave where you’ve been in a little better state than when you arrived.

8 - Do you find the process of working with an outside editor difficult or essential (or both)?

Oh, I love it. The experiences of working with editors who are invested in the work are incredible. It’s the best way to not only catch what old tired eyes missed (and I always miss plenty even after a gazillion reads/proofs), but often where I am gifted my final cold editorial eye to remove a poem from the collection, finally rework a line or a stanza to where it needs to be, or to find the language to describe my intentions for doling this or that.

9 - What is the best piece of advice you've heard (not necessarily given to you directly)?

Don’t stop doing.

10 - What kind of writing routine do you tend to keep, or do you even have one? How does a typical day (for you) begin?

I make coffee, I drink coffee, and I read news. I head to campus. I prep for class, answer emails, and read. I may write. I eat. I may write. I teach. I may write with my students. I go home. I make dinner and eat dinner with my wife. We do whatever we feel compelled to do or not do, and I try the whole thing over again. Never the same.

11 - When your writing gets stalled, where do you turn or return for (for lack of a better word) inspiration?

I read. I always open up five or six books, and I wait for the charge of language to set in. Primarily poetry, but quite often nonfiction and philosophical works.

12 - What fragrance reminds you of home?

I love this question.

An ever-so-slight smell of nicotine. We live in my wife’s childhood home, and her pop was a pack-a-day-plus smoker. It gently leaks from the walls.

13 - David W. McFadden once said that books come from books, but are there any other forms that influence your work, whether nature, music, science or visual art?

Music, big time. I love cover songs, even named a collection after them.

14 - What other writers or writings are important for your work, or simply your life outside of your work?

There is an endless supply, which is glorious. So many of the dead ones, the ones now doing, and, hopefully, the ones who aren’t even born yet, who I’ll discover at my very end.

15 - What would you like to do that you haven't yet done?

Become 200% more patient.

16 - If you could pick any other occupation to attempt, what would it be? Or, alternately, what do you think you would have ended up doing had you not been a writer?

Something to do with end-of-life care. Being there for those who are alone in the final stages of life.

17 - What made you write, as opposed to doing something else?

It found me, I think.

18 - What was the last great book you read? What was the last great film?

Book: Aflame by Pico Iyer. Film: Conclave (There’s an evident pattern developing there, I know)

19 - What are you currently working on?

A poem to fit this line into:

“The dialogue is an endless stream of commas, floor-to-ceiling curtains opened and closed repeatedly to allow one snowflake inside at a time.”

12 or 20 (second series) questions;

August 30, 2025

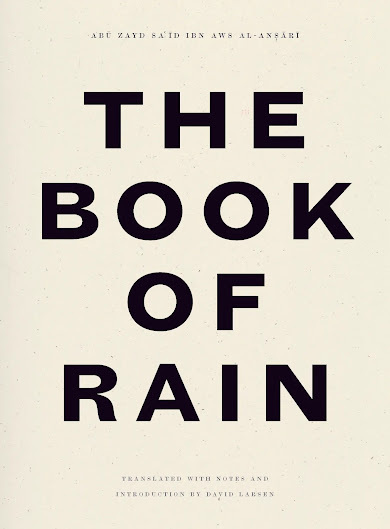

Abū Zayd al-Anṣārī, The Book of Rain, translated by David Larsen

No rivers flow into theArabian Peninsula. Before desalinization technology, all its fresh wateroriginated from the sky. Great tracts of the peninsula were inhabitable only atrain-seasonal intervals, and have until modern times been the exclusiveterritory of pastoral-nomadic communities. That these communities would developan elaborate vocabulary for precipitation and groundwater is unsurprising, andyet (cautioned by the fallacy of “Eskimo Words for Snow”) I refrain from supposinga causal link. The proliferation of Arabic words for weather is proportionateto the proliferation of Arabic words for all kinds of things. (David Larsen, “INTRODUCTION”)

Ifound myself taken with

The Book of Rain

, “the earliest known catalogue of Arabic weather-words, by earlyArabic linguist Abū Zayd al-Anṣārī,” as translated by New York-based scholar, poet and translator ofpre-modern Arabic literature, David Larsen (Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books, 2025) (although I would caution him that the people of theCanadian north, in my understanding, consider that particular moniker a colonialterm, and prefer to be referred to as the Inuit). The Book of Rain isnot only accompanied by an expansive critical introduction by the translator,but a book’s worth of footnotes at the end, adding layering and nuance to thestudy of such an intriguing text more than a thousand years old (the publisher’swebsite notes that the author died in “Basra circa 830 CE, at the age ofninety-five,” if you want to have a temporal sense of the original composition).If you want to know a people, a culture, there’s no better way, one might say,than to approach from the foundation oflanguage, and Larsen offers incredibly detailed insight into the context and reasonsfor differences both temporally and culturally far distant from most westernunderstandings. As Larsen writes in his introduction: “For Arabic langue worthyof study, there were two funds of evidence. One was historical precedent, asenshrined in proverbial expression, pre-Islamic poetry, the text of the Qur’ānand, to a lesser extent, Prophetic hadith. The other was contemporary Bedouinspeech. Certain tribes’ supposed immunity to linguistic corruption gave theirdialects a classical authority that was tantamount to the ancients.” Is this abook of notation or of language or of beautiful music? From the opening line of“[NAMES OF RAIN]”:

Ifound myself taken with

The Book of Rain

, “the earliest known catalogue of Arabic weather-words, by earlyArabic linguist Abū Zayd al-Anṣārī,” as translated by New York-based scholar, poet and translator ofpre-modern Arabic literature, David Larsen (Seattle WA/New York NY: Wave Books, 2025) (although I would caution him that the people of theCanadian north, in my understanding, consider that particular moniker a colonialterm, and prefer to be referred to as the Inuit). The Book of Rain isnot only accompanied by an expansive critical introduction by the translator,but a book’s worth of footnotes at the end, adding layering and nuance to thestudy of such an intriguing text more than a thousand years old (the publisher’swebsite notes that the author died in “Basra circa 830 CE, at the age ofninety-five,” if you want to have a temporal sense of the original composition).If you want to know a people, a culture, there’s no better way, one might say,than to approach from the foundation oflanguage, and Larsen offers incredibly detailed insight into the context and reasonsfor differences both temporally and culturally far distant from most westernunderstandings. As Larsen writes in his introduction: “For Arabic langue worthyof study, there were two funds of evidence. One was historical precedent, asenshrined in proverbial expression, pre-Islamic poetry, the text of the Qur’ānand, to a lesser extent, Prophetic hadith. The other was contemporary Bedouinspeech. Certain tribes’ supposed immunity to linguistic corruption gave theirdialects a classical authority that was tantamount to the ancients.” Is this abook of notation or of language or of beautiful music? From the opening line of“[NAMES OF RAIN]”:Firstof the names for rain is al-qiṭqiṭ“The Tiny Grain.” This is the finest of the rains.

How does a title such as this emerge with apoetry publisher? That is a curiosity, by itself, although there are obvious parallelsaround language and thinking, and critical thinking about language and subjectmatter in the context of its time and place, its landscape and culture. Larsen,further in his introduction, asks: “Does the Book of Rain count asnatural history, or is it a book of language only? The answer depends on yourexpectations of natural history as a literary genre. In early modern Europe,natural history’s emergence is identified with the purge of folkloric materialfrom inquiry into plant and animal life. A rededicationof language to nonlinguisticknowledge is how Michel Foucault characterized it, saying that natural history ‘existsas a task only in so far as things and language happen to be separate.’ This obviouslyexcludes the Book of Rain, whose sources are purely linguistic.” From thesection “NAMES OF WATERS,” as it begins:

Greator small, a river is called al-nahr and al-nahar; al-anhāris its plural. Al-jadāwil “canals,” sg. al-jadwal, are rivulets madeto split off from a river to irrigate crops and palm groves. Al-qanā “anaqueduct” is a canal made to flow underground, and is not called qanā,pl. aqnā (or, as some might say, qanat, pl. quniyy) unlessit has a covering. Any uncovered watercourse is a jadwal, and a khudad“channel” is similar to it. All three words are used whether they run dry orflow with water.

Al-kurr is a “holding pool” wherewater accumulates. (The rope that men loop around the trunk of a palm in orderto climb it is called al-karr.)

To describe water as la’īn “sordid”is to find fault with it. Al-‘udmul, pl. al-‘adāmil, is “well-aged”water, and anything else that is old. Water that does not cover the ankle isdescribed as ḍaḥl“shallow” and ḍaḥḍaḥ “superficial.” Al-raqāq “a thin layer” is used in a similar fashion. Al-barḍ is a “meager” amount of water that you manageto gather, and verb tabarraḍa means “to seek water.”