Sir Poley's Blog, page 3

June 19, 2018

On Wandering Monsters, Part 4: Wandering Traps?

I’ve always hated traps.

There, I said it. Aside from the occasional

booby traps placed by the kobolds and the Ettercap in Into the Living Library, in my

entire GMing career, I’ve only ever used a single trap—also in Into the Living Library—and it was

really more of a plot device than anything else. It was a clearly marked death

trap to encourage the party to turn around and do some exploring and

roleplaying to find a bypass. The trap was a lock; Leonard’s Lightning

Redirector was the key.

Traps are boring. The Rogue makes a Perception Check (and fails it, because

Rogues routinely have terrible Wisdom), then passes their ensuing Reflex save,

and we all move along. Alternatively, the save is failed, and the Rogue takes

damage, which no action or decision from the Player could have avoided in any

case. Some amount of damage will just be taken and the dice will decide how

much; it’s not particularly engaging or interactive. The party recognizes this is

the cost of doing business and deducts a bit more of their profit into healing

potions.

Traps are literally business expenses. Taxes.

But I used to think the same thing about

Wandering Monsters, and lately I’ve come to love those. So far, most of what

I’ve written in this series have been things that have been percolating in my

mind for some time now and tested in Into the Living Library and City of Eternal Rain, but this is largely

new territory.

Can our Wandering Monster table include

traps?

In Living

Library, some minor traps were on

the table as “hints,” but I’m envisioning something much more

comprehensive. If traps are sufficiently foreshadowed—as Wandering Monsters can

be—they will feel less random, and therefore less like wastes of time. If they

aren’t settled solely by a series of dice rolls, but rather decisions (that may

include and affect dice rolls), they will feel less punitive.

“Wandering Traps” don’t

necessarily replace bespoke, custom-placed traps, just as Wandering Monsters

don’t replace designed set-piece encounters. They can work side-by-side,

simulating an active dungeon ecology while reducing GM prep work as a dungeon will

only need a handful of unique, hand-placed traps as the procedurally-placed Wandering

Traps can pick up the slacks.

This post will be an experiment in adding

traps as “creatures” to the Wandering Monster table described in the

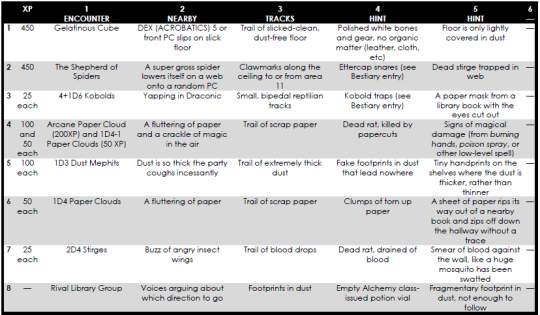

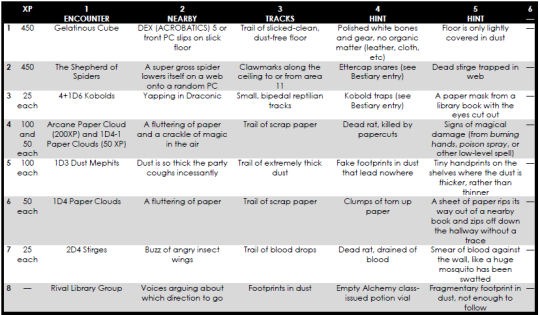

last post, which looked like this:

(The previous, simplistic attempt at

including traps into this table can be seen in the Hint column for the Shepherd

of Spiders (an Ettercap) and for kobolds). Let’s see if we can do better.

In the movies, landmines never just explode. Rather, a character steps on

one, then realizes what they’ve done. A tense scene develops wherein the victim

and his comrades attempt to defuse the mine, or trick it somehow, into letting

the victim step off of it without detonating. Do they dare split up and go for

help, leaving the victim all alone?

In many ways, landmines were designed with

this aim in mind, as rather than simply killing one person, a single mine can

potentially delay an entire group for hours, which in many contexts is more

valuable.

What if in D&D, encountering a trap

doesn’t immediately mean that it goes off, but rather, the party (in

particular, whoever is in front) finds themselves on the verge of detonating the trap, and then has to figure out how to get

out of their predicament?

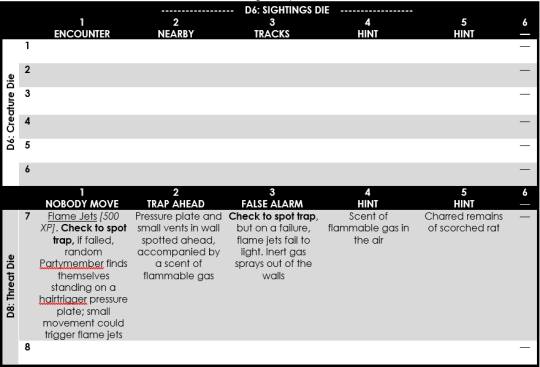

For traps, instead of an ENCOUNTER column, I’ll put in a NOBODY MOVE column. This entry

represents some poor soul suddenly realizing they’re in harm’s way, that is,

standing on the pressure plate (“don’t even breathe or you might set it off!”), with their foot on the

tripwire, or standing on a slowly-creaking false floor above spikes. If they

stay perfectly still, the party might

be able to devise a solution. As this replaces ENCOUNTER, it must be the most immediately dangerous roll, so other

columns ought to be foreshadowing or less-immediate threats.

Unless the party is actively searching for

traps, spotting them should be incredibly difficult. We can safely make this a

hard check, because, as mentioned earlier, failing no longer results in automatically

setting off the trap. A WISDOM (PERCEPTION) check of 20, or an INTELLIGENCE

(INVESTIGATION) of 15 if they are actively searching, is probably a good DC.

Success should be uncommon but not impossible.

However, spotting traps is almost as fun as

getting caught up in them, as it also leads to interesting choices—does the

party press ahead and risk setting off the trap, attempt to disarm it, or take

another route and hope that they can bypass it?

Now, we can lower the DC, but that runs the

risk of meaning higher-level and higher-wisdom characters will always spot traps, which is boring. So

how about we just add another column to the table wherein the party spots a

poorly-hidden trap? TRAP AHEAD can

be our second column, representing exactly what it sounds like—the party

notices a poorly-hidden trap blocking their path, and must choose to brave it

or turn back.

We’ve figured out how traps are spotted,

but unless the party actually knows what triggering the pressure plate will do, they won’t know how afraid to be.

We need to tell the party that the trap shoots poison darts without actually

shooting them with poison darts—this is where our HINT columns come in. We’re still short a column, so let’s extend

this principle further with a FALSE

ALARM column—the party encounters a trap, but it’s either a dud or

malfunctioning. The existence of duds has the added advantage of making them

never know if the trap in front of them is ‘live’ or not.

Here’s an example of how this might come

together. For a finished product, the six creature slots and both trap slots

would be filled in, similar to the table from Into the Living Library.

Alongside the entries in the table, as with

Wandering Monsters, a paragraph or so of description kept nearby is needed to

include a little more detail, and rules like DCs and damage.

Flame Jets. This trap is triggered by a pressure

plate—a disguised flagstone in the floor that depresses with weight placed on

it, causing the arrows to fire. The mechanisms are old, faulty, and weren’t

originally made by a society with particularly advanced engineering, so the

same plate can be walked over many times before it finally decides to trigger, blasting

scorching jets of flame through hidden vents in the walls. If the trap is

triggered, anyone on the pressure plate, anyone attempting to disable the trap,

and anyone else within 10 feet must make a REFLEX SAVE of 12 or better or take

2D10 fire damage. Because the pressure plate is faulty, it may not necessarily

be the partymember in front who realizes their danger—choose your victim at

random from among the party.

We can just append the traps to the end of

the Wandering Monster table. If the GM rolls a D6 (the Creature Die), only

creatures can be encountered; on a D8 (the Threat Die), higher rolls result in

traps. Perhaps D8s are rolled when the party enters new areas (that might

contain traps) while D6s are rolled when the party backtracks, or enters an

empty room. Areas that the party will spend more time in should have more

monsters and traps and use larger dice, though the balance of how many monsters

vs. how many traps will depend on the nature of the dungeon. For example, a

dungeon with a D6 creature die and a D12 threat die will have 6 creatures and 6

traps (with 31 possible unique rolls) will feel very different from a D10

creature die and a D12 threat die, which has 10 creatures but only 2 traps. A

larger number of monsters and traps will mean more variety, but also a greater

likelihood of encountering unforeshadowed traps and monsters. Consider instead dividing

the dungeon into smaller chunks, each with corresponding (smaller) tables, such

as a D4 creature die and a D6 or D8 threat die.

If the party is in a place where they’re

disarming a trap, it either means that they’re very nervous (because someone is standing on the trigger), or were

fortunate enough to spot it before anyone got in the way. The 5th

edition DMG provides scant rules on disarming traps, so I’ll write some of my

own to fit this new system. The DC to disarm the trap should be fairly low, as

the consequences of failure are quite high and it’s probably going to be the

same PC (i.e., the Rogue) who disarms every trap, and as such suffers the most

for failure. An actual plan for disarming the trap has to be presented—simply rolling

a die isn’t enough, as it puts us right back into “roll dice and take

damage, then move along” territory. Feel free to adjust the DC for dungeons

aimed at higher-level play. Similarly, the rarer the traps, the higher the DC

should be, as you run less risk of piling damage unfairly on the Rogue (who can

take one or two trap hits, but not dozens). Correspondingly, for dungeons with

many traps, I would keep the DC quite low. Here’s a first pass of the specific

rule I would use for this:

If an armed

trap is discovered (either from a “NOBODY

MOVE” or a “TRAP AHEAD”

roll), the party will often try to disable it.To disable

the trap, someone first must devise a plan—simply saying “I try to disable

the trap” and rolling a die won’t do. Instead, the Player might declare

that their character will try to wedge a knife under a pressure plate to

prevent it from triggering, or pack a scythe blade’s wall slit full of rocks to

block it from swinging, or plug a dart trap with wax to gum up the mechanism, or

the like. Creativity in this step should be encouraged.After

devising a plan, a skill check must be made. Normally, this is a Dexterity

check using Thieves’ Tools, but depending on the plan, other abilities, tools,

or skills might come into play. Regardless of the skill used, a roll of 12 or

better is a success. A particularly good plan provides advantage, while an

uninspired or foolish one incurs disadvantage. If the Party has encountered an

identical trap previously and has closely examined its workings, the Player

also gets advantage on this roll.A successful

check disables the trap, allowing the Party to bypass it safely. Depending on

the plan presented, the trap might be permanently destroyed or simply

temporarily bypassed. A failed check sets off the trap, which can harm whoever

tried to disarm it, anyone standing on the trigger, and potentially others as

well. If the trap remains a hazard after the party has left, the GM should be

sure to note on her map where the trap is and what state it’s in, in case the

party returns.

June 14, 2018

Next HPN20 Chapter By End of June

Hey all! I’m back to work on Harry Potter and the Save-Or-Die. I’m polishing up the next chapter now, and I have another couple partway-done in the bank; the current goal is one chapter per month for the time being.

June 7, 2018

On Wandering Monsters, Part 3: Slaying CoDzilla

In part

1 of this series, I admitted to having fear and misunderstood Wandering

Monsters in D&D for years, and resolved to find a way to make the system

work.

In part

2, I proposed some methods, tested both in Into

the Living Library and City

of Eternal Rain, for tying procedural content generation into the

overall narrative of your story.

Now, I’ll talk about one of the benefits of

wandering monsters—the end of the 15-minute adventuring day, and with it,

CoDzilla.

“CoDzilla” is a 3.5-era bit of D&D

slang that, for the uninitiated, means “Cleric or Druid-zilla.”

Clerics and Druids, even without much in the way of optimization, could be

enormously powerful. Close competitors were Wizards, Sorcerers, and various non-core

full casters. Starting from very low levels, these classes, through use of

spellcasting, were able to single-handedly—often single-turnedly—win major encounters. Clerics and Druids were especially

notorious, as in addition to a full complement of spells, they were no slouch

at mundane fighting, had a host of miscellaneous abilities, and, in the case of

the Druid, got the infamously-powerful Wild Shape ability and a pet grizzly bear. In contrast, a Fighter (who is maybe 25-50%

better than the bear the Druid gets as icing) gets marginally better at hitting

enemies with swords every level.

By 5th edition, the power

imbalances between classes have been substantially narrowed, with non-casting

classes getting various per-short-rest and per-day abilities that let them have

some time in the spotlight. In my current 5th-edition campaign, I’m

playing a Paladin, and, at 7th-level, don’t feel particularly behind

the party’s Wizard and Cleric. Back in 3.x, I’d be lucky if I even got a turn

in combat, and, with few skills or utility abilities, would pretty much fall

asleep outside of battle. So to a certain extent, this fix is beating a dead

horse, as changes to the rules have reduced the necessity for such a fix.

Still, anecdotal accounts have suggested to me that the caster-warrior

imbalance problem still lurks, especially at higher levels.

Solving this problem is where Wandering

Monsters come in. Those of you playing Pathfinder and 3.x D&D should pay

extra heed to this, but it’s applicable to 5e as well.

CoDzilla

Encounters with Wandering Monsters have

substantially lower stakes than pre-planned, climactic and narratively-key

ones. Typically, the foes are easier and the tension is lower as victory is

all-but assured. This means that characters have to choose between ‘wasting’ limited

per-day abilities to seek a quick victory, or suffer additional damage by dragging

out the fight by sticking with cantrips and regular attacks. The longer the

battle, the more opportunities the monster has to get in a few hits before

going down.

The devil with this decision is that,

either way, casters lose and warriors win. A Paladin’s basic attack is more accurate,

reliable, and powerful than a wizard’s cantrip, so if spellcasters withhold

their 'special’ attacks, non-casters take the spotlight. If the casters obliterate

Wandering Monsters with high-level spells, then by the time they reach the

'real’ fight (those being the pre-planned encounters, typically in dungeon

rooms rather than hallways), they’ll be relegated to cantrips while the fighters

open up with their modest per-day abilities and their more efficient

conventional attacks.

Martial classes do have some limited-use abilities, especially half-casters like

Paladins, so they are pushed into a similar dilemma (“do I use Smite on the

owlbear or save it for the true foe?”) but the stakes are much lower, as

their abilities are weaker and their conventional attacks more powerful than a

true caster’s. This means that even if the Paladins and other half-casters make

the 'wrong’ decision, they can typically make do regardless.

Now, the obvious flaw with this plan is that

at any point the party can just fall back, rest, and come back in with a full

complement of spells, right? This means that wearing the casters down through attrition

is doomed from the start, because they can conveniently heal up to 100% with a

single night’s sleep. This is why adding Wandering Monsters all by itself isn’t

enough—we have to start enforcing other rules as well, such as…

There’s a secret to the long/short rest

split of 5th edition D&D, and that’s that not all classes

benefit equally. Far and away, a short rest is more meaningful to a martial

class than a spellcasting class, and vice-versa for long rests.

Most martial classes have powerful

abilities that recover every short rest starting at level 2 or 3. For example,

Fighters get Action Surge, Paladins get Channel Divinity, and Monks get Ki.

Barbarians are a rare exception, as their key ability (Rage) is actually tied

to long rests. Rangers have no useful abilities worth noting that recharge on

short rests, long rests, or honestly at all, so there’s no helping them.

Spellcasters’ main ability—spellcasting—universally require long rests to

recover in full. Some casting classes, such as the Wizard and Druid, have

abilities that let them recover some spell slots on a short rest—but these

abilities themselves can only be used once

per long rest, so at the end of the day, are still long-rest dependent.

Additionally, martial classes, due to their larger hit dice, tend to recover

more hit points on a short rest than spellcasting classes do. But, because

casters get minor benefits from taking short rests, their players won’t be

frustrated by the need for taking them.

If you, as GM, provide many opportunities

for a short rest (which is about an hour), but keep long rests few and far

between, then martial classes can keep going while spellcasters are run ragged.

In the context of a dungeon, you can, for instance, let them take short rests

in cleared rooms as long as they put a modicum of effort into securing the room

(blocking or locking the doors, for instance), but stress that long rests are impossible.

There is simply no way to have eight relaxing, uninterrupted hours in a

dungeon; Wandering Monsters will

attack, spoiling the rest. What’s more, the constant threat of attack from the

unknown makes true relaxation unachievable. You can be upfront about this;

don’t assume the players know what you mean when you coyly say “well, you could try that, but you might be

attacked in the night.”

If the party wants to take a long rest,

they have to leave the dungeon, set up camp, and come back—which will involve

fighting their way through the Wandering Monsters that have moved into

previously-cleared areas, thus wearing the party down again and defeating the

purpose. Conveniently, all of this is simulated by the Wandering Monster

table—the GM doesn’t have to worry about actually moving monsters from room to

room. Because

Wandering Monster tables are at their heart a computer-free technological aid,

the random die rolls on the table simulates all of the movement of a real

ecosystem, much the same way that a character’s hit points simulate their

overall health, but remove a lot of the headache of doing so.

For very large dungeons, such as Paul

Jacquay’s famous Caverns of Thracia, it

at first appears simply impossible for any party, no matter how stringent they

are with spells and potions, to complete in a single long rest. In part, this

is mitigated by numerous hidden entrances into the dungeon that, once

discovered, can be used to bypass previously-cleared sections. There are also

numerous shortcuts, such as teleport pads and elevators, that can be used in a

similar manner. Still, all of that might not be quite enough, and when

designing very large dungeons, occasional points of safety can be placed that

are free of Wandering Monsters. They might have particularly secure doors, be

protected by magic, or some kind of friendly NPC or monster. Think of these as

a video game mid-dungeon save point, both in terms of how powerful an effect it

will have, and how rare it should be.

Into the Living Library relies

heavily on Wandering Monsters because they play well with the adventure’s time

crunch: each time the party faces such a monster, their consumable resources

(spells, potions, HP) are slightly depleted, and they must choose whether to

press on in their weakened state or return to campus to rest, which means

sacrificing one of their precious few days.

Wandering Monsters, tied with any kind of

external time pressure, pack more work into a single adventuring day, and with

that, the expenditure of more spells. Spellcasters’ 'basic’ attacks (cantrips

and crossbows) tend to be much less powerful than those of a Fighter, Barbarian,

or Paladin. If high-level spells and per-day abilities have to be carefully

rationed out over the course of many encounters, rather than just one or two, then

casters are brought down to the level of non-casters.

Not every adventure should include a time

pressure element, as the players will start to feel rushed and possibly even railroaded,

as the constant time demands may keep them from feeling able to pursue their

own goals. Beware Fallout 4’s Preston

Garvey, who continually dispenses timed quests that pull the player away from

doing what they want to do.

Unbalanced

As a GM, I often forget that my toolbox

includes more than perfectly-balanced encounters. It may sound like an

oxymoron, but there is a time and a place for a poorly-balanced battle, which

brings us back to the original post. Oblivion, my least-favourite Elder Scrolls

game, has highly restrictive game rules in place in an attempt to keep every

battle, whether it be against a necromancer lord or a random bandit, balanced

on a knife’s edge. Enemies and equipment level up closely in step with the

player, meaning that as the player gains power, so too does the world. The

drawback is that there are few if any “oh, crap!” moments where the

player gets in over their head. Likewise, there are very few moments where the

player simply obliterates the enemies in front of them, and, by doing so, feels

like a badass.

By all means, strive for perfect balance

and interesting terrain in your pre-made set-piece battles (such as what might

be found in a dungeon’s room, for example), but for Wandering Monsters, imbalance

is a feature, not a bug. Battles that are 'too easy’ will be resolved quickly

(saving precious game time), and battles that are 'too hard’ won’t be fought at

all—the party will turn tail and run (convincing the party to run rather than

fight a losing battle is a good subject for a later post). Battles that are

close to balanced will be drawn-out slugfests, forcing the party to draw upon

every available resource. They will take ages, and burn through per-day

abilities much faster than you intend, which in turn forces the party to leave

the dungeon, thus contributing to the 15-minute adventuring day. Remember that

easy battles will still drain the party’s resources somewhat, as even the

weakest monsters in 5e have a pretty good chance of getting one or two hits on

any character, and players will be constantly tempted to blow the trash

monsters away with their limited-use abilities, like spells and smites.

Another rarely-mentioned feature of

unbalanced encounters is that they let you use a greater percentage of the

Monster Manual when designing your dungeons, thus increasing the variety of

creatures the party can meet. Using only level-appropriate encounters limits

you to an ever-decreasing handful of creatures as the party levels up, and can

push you into placing monsters in unthematic areas just to reduce the monotony

a little. It also means that, in a few levels, when the party actually can fight the same type of high-level

monster they’ve been running from, victory will feel all the sweeter.

May 31, 2018

On the Wandering Monster, Part 2: Narrative and Foreshadowing

In part 1 of this series, I admitted to having

feared and misunderstood Wandering Monsters in D&D for years, and resolved

to find a way to make the system work.

Now, I’ll examine a few ways of looking at Wandering

Monsters that aren’t a waste of time.

One of the major criticisms with Random Encounters

(which are closely related to, but not quite the same as, Wandering Monsters)

is that they feel, well, random. You’re

walking along, minding your own business, and suddenly a lone owlbear attacks.

You’d never heard that owlbears lived in this forest, and you’ve seen no sign

to hint at their presence thus far. Once you kill it (of course you will),

nobody will ever mention them again. They are battles devoid of narrative or

stakes, and thus, they are a waste of time.

Does it have

to be this way?

These terms are used

almost interchangeably, and are very similar. In lots of ways, if we can fix

one, we can fix the other, so I’ll be mentioning both. Wandering Monsters

specifically refer to encounters found in

a dungeon, while Random Encounters seem to be encounters found in the wilderness. Wandering Monsters,

as the name suggests, usually result in a battle, while Random Encounters

(which are more neutrally-named) can just as easily be a run-in with a

travelling peddler or caravan.

Over at The

Alexandrian, Justin Alexander notes that he suspects, waaaaay back in OD&D,

that Random Encounters were intended not as a single battle, but as an entire

adventure hook. He points out that a Random Encounter could potentially

generate hundreds of bandits, complete with their own officer hierarchy and

magic items, which was obviously out of the scope of a single battle.

Potentially the army

of bandits could be a backdrop to a role-playing or stealth challenge, wherein

the party sneaks by or negotiates their way through the bandits. Similarly, the

GM could map out an entire bandit base as a dungeon, wherein the party fights

or sneaks their way in, kills the leader, takes her magic gear, and gets out.

That’s all great in theory, but to me, in practice, this

sounds like a hell of a lot of work. Is the GM seriously expected to create an

entire adventure because she rolled a 1 on a D6 for a Random Encounter roll?

What about all the Random Encounter rolls made as the party heads back to base

to sell their “liberated” bandit loot? The goal here is to reduce the GM’s cognitive load during

play, not massively escalate it.

This method of looking

at wandering monsters—that each roll potentially generates an entire new

subplot—is especially problematic if the party is already working their way

through some kind of narrative.

Except in the most

extreme sandbox-mode playstyles, most GMs don’t want a die roll to

spontaneously generate entire narratives, so D&D as a whole seems to have

mostly abandoned this idea entirely, stripping the narrative out of Random Encounters

to reduce distractions, resulting in wilderness and dungeon run-ins completely

devoid of story. However, let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater—what

if we use the Wandering Monster roll to deliberately

hook the players into existing narratives, rather than create new ones?

Lantzberg, the setting

of City of Eternal Rain, uses this approach, though it’s possible to go further with it. In City of Eternal Rain, Random Encounter

tables can result in run-ins, or clues to the identities of, a monster and a

murderer. Additionally, some of Random ‘Encounters’ are job postings that launch

pre-written minor sub-adventures. Instead of thinking of Random Encounters as a

distraction from the adventure, why

not tailor them directly into the

adventure? Populate your Wandering Monster tables with clues, hooks, and named NPCs

or monsters and try to get the best of both worlds.

Unlike the OD&D

style of having Wandering Monsters dominate the current adventure, we want a

solution in which the wandering monster table assists the GM, rather than taking

over entirely. Think more like Google Maps—which barks directions at the

driver as she needs them—and less like a self-driving car, which obsoletes the driver

entirely.

We want a solution in

which the GM can seamlessly integrate the procedurally-generated content of a Wandering

Monster table with their own hand-made narrative content. The Wandering Monster

table handles the gruntwork of believably populating a forest or dungeon,

letting the GM focus on bigger, better things. This only works if the Wandering

Monster table is effortless (which is to say, it doesn’t require dozens of subsequent rolls to describe an entire

bandit army) and the results are difficult to separate from the GM’s

hand-crafted content. This is hard to do as long as Wandering Monsters remain completely

devoid of narrative or foreshadowing, which brings up the question: how do we foreshadow

a random roll without causing more

work for the GM?

I mentioned above the

problem of the 'Random’ Encounter, that is, that it is meaningless violence

entirely devoid of context, drama, or warning. This can

seem an inevitable result of using random tables as content generation during

play, but what if I told you it didn’t have

to be like that?

The best solution I’ve

found online can be found over at the Retired Adventurer. I shamelessly cribbed this system, with a few

modifications, for use in Into the Living Library.

In classic D&D,

when a Wandering Monster roll is called for, the GM rolls a D6. On a 1 (or 6, there’s

some controversy there), they roll again on a table of monsters. This system

replaces that entirely, but maintains a 1 in 6 chance of actually bumping into

a monster.

With this system, the

GM rolls one die for the row, and another for the column. The row determines

what kind of monster is discovered, and the column determines what information

or threat that monster reveals. For instance, a row of 7 (“Stirges”)

and a column of 3 (“Tracks”) provides a trail the party can follow,

if they choose, to find some Stirges. Column 2 (“Nearby”) means that the

next time you roll on this table, skip the monster roll and use the previous

result. This means that the party is much more likely to encounter the monster

that just spooked them, simulating it being just around the corner. The odds

are low (only 1 in 6) that the party will encounter a given monster before

seeing some kind of hint as to their existence, meaning that they don’t often feel

“random.” For potentially several sessions, the party have been

seeing bits of torn paper here and there, so someone is bound to say

“ah-HAH!” when they finally encounter the animated clouds of paper

that are responsible, creating a simple narrative for each battle.

Each monster has an

accompanying key with a paragraph or so more information describing their

nature and tactics. For example:

The Shepherd of

Spiders. A single shepherd of spiders—an ancient ettercap—makes this

level of the library its home. An ettercap is a very powerful creature to

attack a first-level party, which is fortunate, because this one won’t. The

ettercap in the library is very stealthy and has no interest in a stand-up

fight. If it is encountered, it can only be spotted on a WISDOM (PERCEPTION)

roll of 18 as it hides among the shadows in the ceiling. It will try to use its

webs to disarm the players, picking off their weapons one at a time. If the

party fails their perception check, the ettercap will steal a weapon, wand,

staff, scroll, etc. from a random character, starting with their biggest weapon

and working its way down. On a DEXTERITY SAVE of 14, a character can snatch the

weapon as it leaves its sheath/strap/etc., and discover the ettercap in the

process. Otherwise, they only notice 1d6 minutes later that their weapon is

missing. Once a weapon has been stolen, or if it has been discovered, the

shepherd of spiders will flee back to its lair in area 11. The shepherd has

been doing this trick for a long time, and is very fast. The shepherd’s goal is

to render the party sufficiently helpless that they will be killed by the other

denizens of the library, and then feast on their corpses. There is only one

shepherd of spiders; if it has been slain, then ignore further wandering

monster rolls of 2. The shepherd is devious; it will create snares with its

webs for the party while they aren’t looking.

That table and this

paragraph is all that is needed for an Ettercap to wage a one-spider Die Hard-style guerilla campaign against

the party, all without requiring one iota of brainpower from the GM. The table tells the GM when the Ettercap lays a trap, and the

paragraph tells it how it attacks (it doesn’t). Note also that the Ettercap is

a full 2 CR higher than the party’s level, meaning that it could dismember the

lot of them without breaking a sweat. This would normally rule it out of a 1st-level

adventure (greatly reducing the array of monsters available to the GM, and letting

the players get complacent as they move from one level-appropriate encounter to

the next). Elsewhere in the adventure, rules on the spider’s snare traps are

provided. If the party manages to corner and kill the Ettercap, they will feel enormously self-satisfied, as they finally

bagged the bug that had been laying traps for them.

May 29, 2018

On the Wandering Monster, Part 1: My God, What Have I Done?

It’s no secret that wandering monsters and

random encounters have gotten increasingly unpopular in recent years. I vaguely

recall playing a bit of AD&D with a babysitter when I was really young, but in practice, I started

playing “for real” in the early 2000s with the launch of 3rd

edition D&D, and it was maybe fifteen years before I even considered using a random encounter as a

GM. I’m not convinced any GM I’ve played with has ever used one. But I’m starting to realize that, in doing so, we’ve created a series of problems for ourselves, and that maybe Wandering Monsters deserve another look.

Most of the time, as a GM, I simply decided

when it was appropriate for the players to fight an enemy, and when that

decision was made, I would open the monster manual to the index of Monsters by

CR, then pick a couple monsters with a CR equal to the party. This was the

technique I taught to new players who wanted to GM for the first time. I have

near-photographic recall of every skill and feat in dozens of 3.5-era D&D

splatbooks, I know the stat modifiers of every PC race, I can tell you the BAB

and save progression of (probably) every

class, but I’m actually not even sure if the 3.0/3.5 Dungeon Master’s Guide even

has Wandering Monster tables, much

less whether they’re any good.

I remember seeing such a table at some

point—I think it was in the Planar

Handbook but I’m not sure—and scoffing. The table had something like a Pitfiendat

one end of it and an Imp at the other, which struck me (at the time) as

completely ludicrous. If a tenth-level party fought a Pitfiend, they would die.

If they fought an Imp, they would win in the first action, and we’d all be

wasting our time. I imagined the ages

it would take to pull out the dry erase board, draw the scenery, roll for

initiative, determine turn order, and see the Imp die instantly (in exchange

for no XP) and imagine precious hours of my life simply sliding away from me.

Likewise, (I reasoned) if some fool of a GM actually rolled a Pitfiend and went

through with it, their campaign was effectively over. The party would be

slaughtered, everyone would be upset and unhappy, and it would be the GM’s fault

for using level-inappropriate encounters.

“Hellish” is right. (Manual of the Planes, 2001. p. 151)

I only realize this in hindsight, but it is

deeply ironic to me that my least favourite Elder Scrolls game is Oblivion. I

hated it (by Elder Scrolls standards, which is to say that I consider it one of

the best games ever made, just not as

much as Morrowind) as soon as I left the tutorial area. In Oblivion, every

single monster is scaled to provide a perfectly adequate, but overcomeable,

challenge based on your character’s current level. If you optimize your

character at all, the game is easy from start to finish, as everything from

mudcrabs to daedra are, and will always be, slightly weaker than you. If you make

bad skill choices, the game is a merciless slog as you obtain meaningless levels

and never catch up to the world around you.

In contrast, Morrowind, the lesser-known

and substantially-uglier earlier instalment, makes very light use of level

scaling. At the start of the game, you can walk right into the ash wastes and

scale Red Mountain, where you are certain to die. The monsters there are

appropriate for high-level play. Likewise, at high levels, very little in the

Bitter Coast, which is a lower-level area, will provide a challenge. If you’re

playing at low levels and run into a Dremora (an Elder Scrolls demon-equivalent),

you run. You run like your life depends on it. This is a level of

fear and suspense that I’ve rarely felt in a tabletop game. The Morrowind AI is

pretty dumb, so the enemies don’t chase you very far or effectively, meaning

running away is relatively straightforward. If you’re lucky and a little

clever, you can take down such an enemy at low levels and grab some very not level-appropriate loot. Sure, it

“unbalances” the game, but Morrowind doesn’t really have any balance

to begin with—and you’ll feel pleased as plum with your shiny new Daedric

Tanto. Besides, if you end up too powerful for the area you’re in, you can just

gravitate to somewhere that provides a little more challenge.

It was a dark day for me when I realized that the D&D worlds I was

running were more like Oblivion (which, in my mind, can do no right) and less

like Morrowind (which can do no wrong). I floundered for a while looking for a

solution, house-ruling things that didn’t need house-rules, devouring every

alternate game system I could come across, until I stumbled across some light

in the darkness: the Wandering Monster. Justin Alexander, the genius behind the

Alexandrian, wrote an absolutely brilliant analysis of the decline and fall

of Wandering Monsters, which you can find here.

Read it. It ties into the history of

D&D, the rise of the 15-minute adventuring day, the decline of the Fighter,

and the advent of CoDzilla. Then follow that up with this,

which discusses the fallacy that I—among others—made with respect to CR and encounter

balancing, which is to say, we didn’t read the damn rules.

Being a known rules lawyer, with all the

good and bad that comes with this, is very close to my identity, so please

appreciate that, for me, this is a deeply shameful admission.

All of this happened to me about a year

ago, and honestly, I’m still reeling from the shock of it. I think that

mastering the use of the Wandering Monster is the difference between the style

of game I’m used to running—which is to say, Oblivion, and therefore, lame—and the style of game I want to run—Morrowind. It was during the initial period of shock that I wrote Into

the Living Library, an adventure that, both narratively and

mechanically, hinges almost entirely on Wandering Monsters. I borrowed and

stole a bunch of innovative ways of handling wandering monsters to pull that

off, but I think I can go further. We

can go further. We can perfect the

Wandering Monster, slay CoDzilla, reduce GM prep time, and do it all without

wasting precious gaming time.

Next up: Wandering Monsters and the

Narrative

May 25, 2018

On Towns in RPGs, Part 6: Wait, Wasn't This About Maps?

In the first article in this series, I embarked on an ill-defined

quest to figure out what, if anything, a town map is actually for in tabletop play.

In the second,

I took a look at the common metaphor comparing towns to dungeons—unfavourably.

In the third,

I proposed an alternate metaphor: that cities are more like forests than

dungeons.

In the fourth,

I looked at how forests are used in D&D to see what we could use when

thinking about cities.

In the fifth,

I got into to the nuts and bolts of designing cities for use in D&D.

Now, we’re going to break out the Gimp (or,

for you fancy folks, Photoshop) and make

some maps.

Back in the first article, I compared these

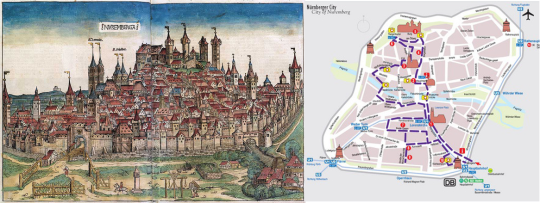

two images of medieval Nuremberg:

In that article, I argued that we can make

things easier for ourselves as DMs, and be more effective besides, by splitting

a D&D map into two separate illustrations: one to set the tone, and one for

crunch, much like the tourist map on the right. It’s ugly as sin, but if you’re

a tourist in old Nuremberg, it tells you exactly what you need and no more.

Functionally, this particular map wouldn’t be very useful in D&D (again, it

emphasizes actual streets, which we don’t care about, because towns

are not dungeons) but, because towns

are forests, we can look to existing high-functioning D&D map design—that

is to say, regional maps—as inspiration.

By adding an

illustration, which, unless you’re publishing this city, you can just steal

from the internet, you’re taking a lot of the load off of your map. The map no

longer has to be particularly pretty, it doesn’t have to show individual

buildings or roads, and it doesn’t have to fit any particular theme. All it has

to do is be easy to read, functional, and packed with information. Think about

it a little like a character sheet for your city.

Most D&D town maps

try to give a literal depiction of the exact layout of the streets (which isn’t

useful) and also serve as an

evocative piece of art (which is, but can be done better and more easily in

other means), but doesn’t provide much in the way of useful gameplay

information. So… what is useful

gameplay information?

Travel Time

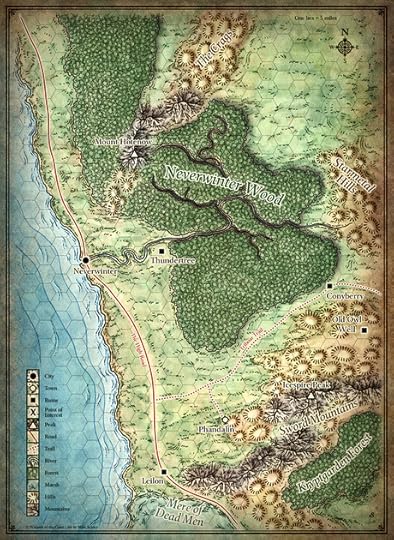

Consider the map of

the area around Neverwinter Woods that I used earlier. Somewhere in pretty much

every RPG rulebook is a table showing daily travel speeds through various

different terrain types. In D&D 3.5, for example, an unencumbered human can

cover 18 miles overland on flat ground, or 12 miles per day through forests.

These values can be increased by major highways. Knowing this information, it

becomes trivial for the DM to quickly count up hexes (which are 5 miles each),

look up a few numbers on a table, and do a quick calculation to tell the party

how many days it takes to get from, say, Neverwinter to Leilon (13 hexes→65

miles→24 miles per day on a highway→2.7 days travel time, rounded to 3). This

is important information narratively, but also for game mechanics, as it

determines how much food the party must carry (which plays into the encumbrance

and wealth rules), and how many random encounters they risk, well,

encountering.

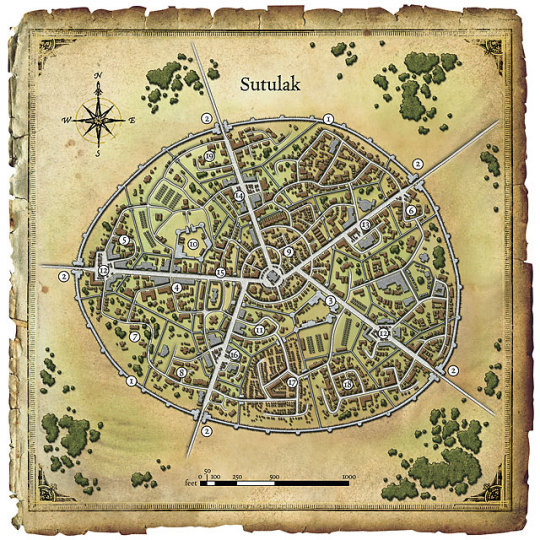

Now try to do the same calculation with

this map:

An unencumbered human can walk 300 ft per

minute, or hustle 600 ft in the same

time, though jogging through the city armed to the teeth (as most PCs are)

might attract attention. Try to figure out how long it takes to get from, say,

#14 to #18 on the map without giving up. There’s no grid of any kind, so you’ll

have to actually measure the distance. You can’t travel in a straight line

because of the intervening buildings except along the major highways, so you

can either measure it in chunks, or, I guess, use a piece of string or

something. Then take your measurement, compare it to the scale and divide it by

300 or 600 to find out how many feet it took to do such a thing, and then…

…realize that this number is actually

pretty useless. Even if you go through the above steps (which I can’t even

bring myself to do for this example, and would absolutely not do during play),

it’s not a helpful measurement. It doesn’t take into account crowds, traffic,

getting lost, being accosted by strangers, looking for a street sign that’s

hidden behind a bush, and all of the things that actually determine how long it

takes to get around in a city. So, like every other GM in history, you’ll never

look twice at the “movement per minute” table, never look at the

scale, never look at the map, and just say, “eh, it takes ten

minutes.”

If that works for you, that’s fine; you’ve

read a series of walls of text and won’t get much out of it. But if you’re like

me, you’ll always have a nagging feeling that you’re giving up.

The map of the region around Neverwinter

was created with the express purpose of being used in D&D. It is highly

specialized for exactly this purpose. The map of Sutulak here was designed, apparently,

to help with the morning commute of Sutulakers. So let’s turn the city of

Sutulak into the forest of Neverwinter.

We need to figure out the town equivalent

of forests, mountains, fields, and highways. Highways are literally highways—broad,

relatively straight avenues that cut through cities and connect key

destinations (such as a market and a gatehouse). As for plains, forests, and

mountains? They map pretty clearly to me as low, medium, and high-density

construction. Higher density leads to more confusing, twisty, and narrow roads,

as well as denser crowds, making it slower to move through these areas (both

because you risk taking the wrong turn, and you’ll be delayed by traffic).

Low-density is the opposite: the more spread-out the buildings are, the more

space there is to move between them, the less people there are doing so in the

first place, and the easier it is to see where you’re going and take the right

streets. If your town has large-scale natural elements, such as forests and

hills, they should also be included on the map. Sutulak here is criss-crossed

with bizarre inner city walls with limited chokepoint entrances, which should

also be included on the map.

Districts

In the fifth

article in this series, I argued that D&D towns should be thought of as a

small number of named, memorable districts (plus a couple of less-memorable

Hufflepuff districts). Each district can have its own distinct flavour, racial

makeup, police force, and random encounter table (if you use those), and a

memorable name.

Points of Interest

Critical buildings and

places should be marked with numbers that correspond to a key somewhere. For

the more artistically inclined, you could also pick out these buildings in

other ways, such as the Nuremberg tourist map’s large silhouettes of major

attractions.

Putting it Together

You’ve stuck with me

this far, let’s power through to the end. Let’s take this useless map of

Sutulak and turn it into a cutting-edge game aid, step by step.

1. Give it a grid. You can use a square

grid (like a pleb) or a modern,

high-tech hex grid. Either is absolutely fine. I just overlaid a hex pattern as

a new layer over the original one.

Counting distance is massively easier now.

No string or ruler needed; just count the hexes.

2. Highways and Barriers

The

various walls and highways criss-crossing the city are important both

narratively and mechanically, so let’s highlight them, too. Try to keep the

number of these small so as to be significant and memorable, don’t just connect

everything to everything else with a highway, because then we’re back at the

level of worrying about individual roads.

Red lines are highways and allow faster

movement; grey lines are walls and prevent movement barring some kind of skill check,

spell, etc. Crossing them may also be illegal.

3. Embrace Abstraction

This map still has a bunch of minor streets

and buildings confusing the issue. Here’s where we’re going to embrace full

abstraction by removing them outright. Stop seeing the trees, start seeing the

forest; there are no buildings or roads, there is only districts and density.

Let’s get this out of the way first of all: this won’t be pretty. With a proper illustration, though, it doesn’t need to be.

What I’m going to do is use different fill

textures to denote different types of hexes representing district and density.

District allocation is more of an art than a science; theoretically I could use

every walled-in subdivision as its own district, however, this crazy

criss-crossed town has too many of those to be memorable. Instead, I’ll combine

a few walled-in sections into districts, and in doing so, declare that they

have economic, cultural, and ethnic ties to each other. A real artist could do

pretty textures in these areas (like the forest texture in the Neverwinter

map), but as this is a test case, and I am not a real artist, I don’t want to

get too bogged down in aesthetics and I’ll use simple pattern fills.

Here’s the district map. Different angled

lines represent different neighbourhoods. There are five, which I’ve creatively

titled North, East, South, West, and Central. Each district (except central)

has at least one gate to the outside world and one highway. I’ve also moved the

walls above the grid layer (making them more visible) and removed the grid

outside the city as it was noisy and unnecessary.

Now we can inject building density into the

equation. Building density implies population density, which tells us how

narrow, twisty, and crowded the streets are, which finally solves our ‘movement

rate’ question.

Here we have it: five districts, clearly

delineated from each other through textures, and density represented by weight

of the lines. Central district there is packed, as befitting a city center, so

the entire district is at maximum weight. Because moving through cities has

little to do with your physical movement capabilities and more to do with

traffic and navigation skill (a Ferrari wouldn’t get you through traffic any

faster than a Honda), we can largely ignore a character’s movement stat and

base movement just off of hex density. Maybe we can come back to this, but for

the time being, let’s say you can move through low density hexes (with little

traffic and lots of clear sightlines making for easy navigation) and highways

at a rate of 3 hexes per minute, medium density hexes at a rate of 2 per

minute, and high-density hexes at a rate of 1 per minute. Highways boost speed

not only because they are broad and straight, but also because it is much

harder to take a wrong turn on them and have to double back.

If you wanted a coarser grid, you could

make each hex 300ft, and say that it took you 1 minute to move through a light

density hex, 2 minutes to move through a medium density hex, and 3 minutes to

move through a high density hex.

I also added points of interest numbers in

this step. If I were to do it again, I’d make them more distinct, such as using

the original map’s white circles, or perhaps with stylized building

silhouettes, like the Nuremberg tourist map.

Districts can also be denoted using colours,

with darkness and lightness indicating density, perhaps given borders like nations

on a world map to distinguish them a little more from each other. Gates between

walled prefectures are also important enough that maybe we could borrow a

little from dungeon maps and give them a bright, visible “door”

symbol. Also, the medium and heavy weighted areas are a bit too similar looking

for my taste, so improvements could be made there, as well.

Still, I think this is the right direction.

I’m going to let this idea percolate for a while, and maybe try it out in a

game or two of my own, before tinkering with it too much.

May 22, 2018

On Towns in RPGs, Part 5: Building a Playable City

In the first article in this series, I embarked on an ill-defined

quest to figure out what, if anything, a town map is actually for in tabletop play.

In the second,

I took a look at the common metaphor comparing towns to dungeons—unfavourably.

In the third,

I proposed an alternate metaphor: that cities are more like forests than

dungeons.

In the fourth,

I looked at how forests are used in D&D to see what we could use when

thinking about cities.

Now, we’re going to get to the nuts and

bolts of designing cities for use in D&D.

Districts, not Distance

No player is ever

going to remember, or care about, the actual distance between their current

location and the tavern they’re trying to get to. Similarly, they won’t

remember, or care about, the roads they have to cross to get there.

The absolute

most you can hope for is that they’ll remember and care about some of (but

not all of) the neighbourhoods they have to go through. In Terry Pratchet’s

Ankh-Morpork, the Shades is an extremely memorable and dangerous area. Like

Pratchett’s characters, players are going to avoid it wherever possible and yet

always find that they have to go through it. Planescape: Torment’s Hive and Fallout:

New Vegas’s Freeside have similar qualities. If you grimly tell the

players: “the quickest way to the princess is through—oh, dear—the

Shades,” they’ll have a reaction to it.

Don’t overdo it with districts; keep the

number small enough for them to be memorable. I’d recommend seven as an

absolute maximum, but as few as three is perfectly acceptable. Lantzberg,

from City of Eternal Rain, only used

three (one each for lower, middle, and upper class—end elevation). A district

can be as big as you like; feel free to simply scale them up for larger cities.

Hufflepuff

It’s no secret that in JK Rowling’s Harry Potter series, only two of the

four houses matter at all. If you’re not Gryffindor or Ravenclaw, you’re lucky

to get any screentime at all. However, if they were simply cut from the series,

then Hogwarts would feel terribly small, as if it were built solely for Harry

to gallivant around in, and not part of a living, breathing world. Your city

can’t just have people to tell your players who to kill and people to be

killed, it needs someone to clean up the mess after, also. From a narrative

standpoint, these people don’t matter, and will rarely be mentioned, but they

can be used to pad your world out. When dividing up your map into districts,

include a few that, as far as you’re concerned, will never see an adventure, and give it maybe one or two notable

characteristics. These are areas that are primarily residential, or involve industries

not relevant to adventure (i.e., anyone other than an alchemist, blacksmith, or

arcane university). Feel free to leave these places utterly devoid of points of

interest.

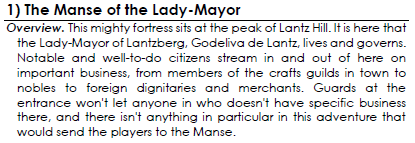

In the adventure written for Lantzberg, for

instance, there’s little to no reason to ever visit the castle at the peak of the

hill. It’s there for verisimilitude (someone

has to be in charge) and for the GM to hook later adventures to (which I’ll

elaborate on in my next point), but mainly it’s just there to make the city

seem larger. Similarly, most of the buildings in Castleview are manors of rich

and important citizens, each one of which might have any number of use for a

band of adventurers, but only a handful are actually fleshed out. After all, it

would hardly feel like a living, breathing city if every single building was

tied into a single adventure, would it?

Gaming is full of Hufflepuff Houses: the 996

Space Marine chapters that aren’t lucky enough to be Ultramarines, Blood

Angels, Dark Angels, or Space Wolves; D&D fiends that are neither lawful

nor chaotic, Morrowind’s Houses Dres

and Indoril, and any of Homeworld’s Kushan

other than Kiith S'jet. This isn’t laziness; they’re there for a reason: they

make the world feel larger.

Try to design a city large enough, and

versatile enough, that once the current quest is wrapped up, you can inject

some more content into it without serious retconning. This is part of where

your Hufflepuff-tier-neighbourhoods come in—maybe one of them has been under

the heel of a violent gang the whole time, but the party never found out

because they never went there. Once the players have started to clear out your

adventure ideas and points of interest, there’s still plenty of room to pump

some more in without the city bursting like an over-inflated balloon.

The map I posted earlier probably

represents the upper limit of how detailed you should make your city. A GM

could run a few more adventures out of Lantzberg, but a long-running campaign

would probably benefit from a bit more room to breathe.

What are the kinds of things a DM really needs to know about a city? D&D3.5

had little statblocks for cities and settlements that broke down the

demographics of different areas, but that’s probably more granular than is

actually necessary. Remember—every bit of detail that you include has the

potential to distract the GM from finding the fact they actually need. It isn’t

for instance, particularly important to know that 12.5% of a neighbourhood’s

population are halflings while 54% are elves, but it might be useful to know

that a neighbourhood has a notably large elf population and an often-overlooked

halfling minority.

the Watchers Watch?

One infamously common thing that comes up

in D&D is the city watch. It’s shadow looms large over every action the

party, and your villains, will take, so it’s worth thinking about them a little

bit. Its best to err on the side of making them too weak rather than too

strong, as a powerful, well-organized law enforcement group can really put a

damper on the opportunities for adventure. The counter-argument is that if the

city watch isn’t strong enough to threaten the party, then the party

effectively has the run of the city; my preferred answer to this problem is to

give the local lord a powerful knight or champion who can be used as a

beat-stick against major threats to law and order (like the PCs) if need be,

but can plausibly be busy enough with other problems to leave some for the

party to handle.

When deciding who the local authorities

are, almost anything you can come up with is more interesting (and historically

plausible) than a centralized, professional police force. Here’s a few

examples:

militia organized by local guildsA

local gang that provides protection in exchange for money and doesn’t want

outsiders muscling in on their turfA

semi-legitimate religious militant orderA

mercenary group funded by a coalition of wealthy merchants (who just so happen

to overlook their own crimes and corruption)

Don’t get too bogged down in their stats;

just pick a low-level NPC from the back of the Monster Manual and write down who they work for. Different

neighbourhoods can share the same organization, but try to prevent a single

organization from policing the entire city.

By breaking up law enforcement by district,

you also prevent the entire city dogpiling on the party when they break a law, like

you see in video games. If the party robs a house in the Ironworker’s District,

they can lay low in the Lists, where the Ironworkers’ Patrol has no

jurisdiction, until the heat dies down.

All those numbers you see scattered over

D&D cities? Now’s the time to add them. Each one should correspond to a description

in a document somewhere. These descriptions can be as long or as short as you

wish. For example, on the short end, #1 from Lantzberg just has this to say:

However, and I won’t get into too much

detail for fear of spoilers, some of those numbers are elaborate, multi-page

dungeons.

While you should endeavour to keep the

number of districts low, there is no ceiling to how many points of interest you

should put into the city. Don’t burn yourself out. If you can come up with six,

put in six. If you can come up with fifty, put in fifty.

A point of interest can be anything from a scenic

overlook to a toll bridge to an elaborate sewer system packed with kobolds and

giant rats and treasure. They can be as fleshed out or as minimal as you are

comfortable with. There’s a sweet spot that varies from GM to GM, as if you

include too much detail you suffer from information overload as the party

approaches the point of interest (sixteen pages of description, for instance,

for a single shop is less than helpful), while too little information might

lead to you having to do too much on the fly. I like maybe one to three

sentences per point of interest, or per room in a point of interest if it is important

enough to warrant its own map (I typically only map dungeons).

I’ll write a series on

handling random encounters later, but for now, breaking up encounters by

district is a convenient way to do it. More dangerous districts, for instance,

might have muggers or even monsters that attack (especially at night). If

you’re going to use random encounters in your campaign, creating a table for

each district lets you use your local colour to affect actual game mechanics.

Castleview, for instance, is very safe due to constant patrols by the Lady-Mayor’s

Watch, while the flooded Lists are full of man-eating fungi, ghouls, criminals,

and who knows what. This lets you follow the age-old advice to “show,

don’t tell.” You don’t have to say

“this area is full of crime,” you can show the players this by throwing some criminals at them.

This post has already

gone on way longer than intended. Next time, we’ll use what we’ve learned to

answer the original question and make better town maps.

May 17, 2018

On Towns in RPGs, Part 4: The Cobblestone Jungle

In the first article in this series, I embarked on an ill-defined

quest to figure out what, if anything, a town map is actually for in tabletop play.

In the second,

I took a look at the common metaphor comparing towns to dungeons—unfavourably.

In part 3, I proposed an alternate

metaphor—that cities are more like forests than dungeons.

Now, we’re going to draw parallels between

forests and cities to see what implications there are to a GM.

Every GM with even a gram of experience has

sent their party through a forest at some point. Forests are almost as familiar

an environment to GM as dungeons, while running urban adventures is a continual

source of confusion and worry. So let’s see what we can learn about running an

adventure by pulling ideas from forests.

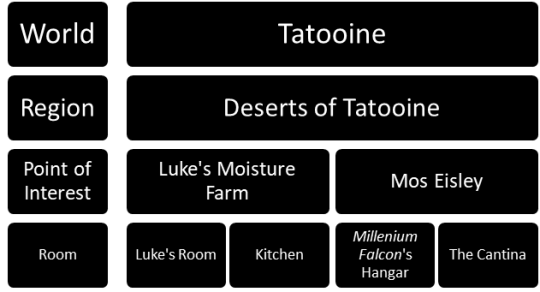

The way I often conceive of D&D worlds

is in layers. Each layer contains one or more smaller areas, on which you can (metaphorically)

click, zoom in, and see more subdivisions. This mindset might be a result of video

games like Final Fantasy where the

overworld and dungeon areas were strictly divided into different screens, but I

find it helpful on the tabletop as well: there’s the World, which includes many

Regions, which each in turn have many Points of Interest, which themselves have

Rooms.

Most campaigns will include only one world,

and even if campaigns include multiple, they tend to each only have one Region.

In Star Wars, for example, the

concept of a “planet” and a “region” tend to be synonymous—Tatooine

is a desert, Hoth is a tundra, the moon of Endor is a forest, and so on. Naboo

is pretty unique in this context in that it effectively has two regions—an

ocean and a forest. In D&D, a great example of a multi-world setting is Planescape, which features planes such

as the Plane of Fire and the Outlands (which are often thought of as single-region),

as well as several major metropolises, most famously Sigil.

“Regions” in a typical D&D

world would include a specific forest, or mountain range, or desert. “The

Westwoods” would be a single region, “forests, generally” is

not. Region-level travel is typically measured in days or weeks, rather than

rounds or minutes, so GMs tend to lean heavily on procedural content generation

like random encounter tables to sprinkle these days or weeks with notable

events and discoveries along the way. These random rolls accompany bespoke

content created manually by the GM, such as a monster selected directly from

the Monster Manual, or pre-written

NPC encounters.

Each Region is a container for one or more

points of interest. These are things like magical springs, taverns, washed-out

bridges, and even entire dungeon complexes. In a video game like Final Fantasy or Baldur’s Gate, in an adventure site, the game would zoom in to a

level where you would actually see your characters walking around where you

direct. When using an adventure module, points of interest will include maps to

a scale measured in feet, rather than miles. At their most modest, a point of

interest can be a simple skill challenge (how will we cross the river with the

bridge washed out?) or comment “on the fifth day of travel, you see Lonely

Mountain crest on the horizon”), and at their most complex, a point of

interest is multi-session crawl, such as the entire Caverns of Thracia.

When people try to think about a city as a

dungeon, they’re really saying that a city is on par with a point of interest

In the diagram above, Mos Eisley (a city)

is a Point of Interest (a dungeon-scale site) divided up into buildings (which

are Room-scale locations; important ones would have their own keyed entries

like a dungeon’s room would). Elsewhere in the same Region (the Deserts of Tatooine)

is the moisture farm that Luke grew up on, which is also divided up into rooms,

such as the room Luke works on C-3P0, and the kitchen, where blue milk is consumed.

In this view, streets are akin to the hallways of a dungeon, and buildings are

like rooms. Every building, street, and lamp post is important, as they might

provide cover in a shootout or an obstacle in a chase.

By similar logic, when I argue that a city

is a forest (that is to say, a region-level area), I’m saying that the city

should be bumped up one step on the scale:

If Mos Eisley is bumped up to be its own

region surrounded by the deserts of Tatooine,

rather than inside the deserts of Tatooine,

it leaves more room for fleshing out its own components, which are dungeon-tier

Points of Interest now. Travel around Mos Eisley is handled in an abstract way with

a die roll for random encounters every hour or so (*rolls* “uh-oh, you’ve

been pulled over by Stormtroopers!”) rather than dungeon-crawl-esque

movement (“hrm, should we take a left or a right at the bantha?”)

When running an adventure in a city, don’t

sweat the details. It doesn’t matter what street the party has to take, and it

doesn’t matter how many minutes or rounds it takes to get there. By ignoring

these details, you aren’t giving up or giving in—you’re being efficient. You

wouldn’t describe every tree in a forest and wouldn’t call for a Climb check

for every hill; similarly, you don’t need to talk about or think about every

road and intersection.

If, for some reason, it is critically important

that building A (say, the Temple of Heironeous) is directly across the street

from building B (say, the temple of their hated enemy, Hextor) for narrative

reasons, then note this in their keyed descriptions. In many ways, the temples

of Hextor and Heironeous together would function as a single larger Point of

Interest. Similarly, in Terry Pratchett’s Men

at Arms, it is critically important for murder-mystery reasons that the Guild

of Assassins shares a wall with the Guild of Fools. However, what isn’t important is how many left turns

and right turns it is to get to the Guilds of Assassins and Fools from the watch

house. The distance between the watch house and the guilds is abstract (because it doesn’t matter

beyond broad generalities), while the distance between the two guilds is concrete (because it really matters).

Enough

A city map is only one layer to the

adventure, and is not, in itself, sufficient to run an urban adventure—but it’s

a start. Various books, such as the third-edition-era Cityscape, provide advice for creating cities at the regional level, that is, drawing major

roads and creating districts and neighbourhoods and such. This part’s easy and

fun, but it’s the next step (“okay, what do we actually do here?”) where I as the GM start

to panic, and, I’d be willing to bet, other GMs do as well.

What’s missing is dungeons. Points of Interest. It’s not enough to simply say

“ah, this is the Hive, it’s full of scum and villainy,” you have to say

to yourself “in the Hive is the Mortuary, which is a dungeon.” It’s

around that point that it is appropriate to grab the graph paper and start drawing

hallways and rooms and chests and traps—classic D&D stuff. Once you’ve got

your dungeon, it’s a simple matter of hooking the players, which is no

different than with a wilderness dungeon—rumours, mysterious letters, job

postings, and all the usual tricks can be used freely here.

Making an urban dungeon is very similar to

a wilderness dungeon, but you have one or two extra considerations: the

authorities, and the peasants.

Law Enforcement

One way or another, you need to keep the

pesky authorities out of the dungeon. Either they’d arrest the PCs, or they’d

arrest the vampires, and both ways are boring. There’s loads of ways to pull

this off, but here’s a few examples:

PCs are the authorities (either

full-time, like a fantasy SWAT-team, or are hired in as mercenary contractors)The

law enforcement are the monsters (i.e., the vampires or whatever have

mind-controlled or corrupt guards protecting their ‘dungeon’)The

law enforcement has no authority in the dungeon (which, like the Mortuary

earlier, is ruled by a powerful faction, in this case, the Dustmen of Sigil)There

is no centralized law enforcement (each district is controlled by its own

faction, gang, or guild, and whoever has local authority has no interest in the

dungeon)

Torches and Pitchforks

If there really is a fully-blown dungeon

operating in a town, something has to have prevented the local populace from

rising up against it, torch-and-pitchfork style.

peasants are cowed into submission (the “seemingly-ordinary village in

Transylvania” solution)The

peasants don’t know about the dungeon (the “cult in the sewers”

solution)The

peasants are in on it (the “Hot Fuzz” solution)“I Go Find Some

Berries or Something”

In a forest, if the party is low on food

and a player says the above sentence, no GM would just let them find berries. Berries represent—quite literally—a free

lunch, which proverbially doesn’t exist. At the very least, a skill check is

needed, and a low enough roll provides the possibility of danger (consuming poisonous

berries, being attacked by giant owls on the way, that kind of thing). There are free berries out there in a forest

for anyone to pick, but finding them requires certain skills and the accepting

of a degree of risk.

As a GM, keep an eye out for the “free

berries” of the city. In the modern world, we’re used to municipal

governments providing many services free-of-charge. Fire fighters and police

can be called in an emergency, there are charities and food banks if you’re

down on your luck, and (depending on your country and insurance situation),

hospitals and clinics can be gone to if you’re sick or injured. Our phones can

find these resources for us and provide easy-to-follow directions to their

doors.

In the world of D&D, things are not so

simple. Standing police forces are a modern invention; in the past in many

cities, guilds organized militias to patrol certain areas at night if at all.

Large stretches of the city might have no law enforcement at all, or (for

example) perhaps on Tuesdays—the night that the infamously corrupt Shoemaker’s

Guild patrols the streets, lawlessness might be preferred. If you’re sick or

injured, it’s up to you to figure out which doctor is legitimate and which is a

scammer. A PC can’t just walk into the office of a good doctor any more than

they can just go pick some healing herbs in the woods—both require local

knowledge, experience, and/or a skill roll.

May 15, 2018

On Towns in RPGs, Part 3: Towns are Forests

In the first article in this series, I embarked on an ill-defined

quest to figure out what, if anything, a town map is actually for in tabletop play.

In the second,

I took a look at the common metaphor comparing towns to dungeons—unfavourably.

If you just stumbled on this post, I

encourage you to go back and read parts 1 and 2. Go on; I’ll wait. Nope, I

lied; I’m going on without you.

Towns are forests.

I don’t mean that in a wishy-washy, poetic

sense, but rather, in a very grounded, gamey sense. If a GM can run an

adventure in a forest, they can run an adventure in a town. This might sound

crazy, but bear with me.

D&D?

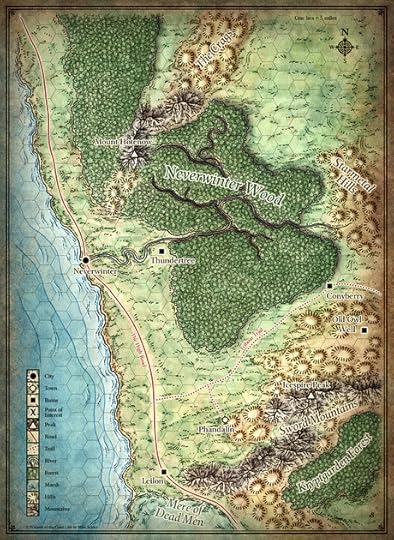

Here’s a region-scale hex map showing

Neverwinter Woods, from the 5th edition Starter Set, and it’s the kind of D&D forest that I have in mind as I talk about them.

Forests are as classic a D&D location

as taverns and dungeons. Maybe it’s personal bias, having grown up in the

Pacific Northwest, but overwhelmingly the most common wilderness environment I’ve

played in have been forests. In the world of D&D, “Nature” means

“Forest"—just take a look at the Ranger and Druid classes if you need

proof. Both of those classes are flavours of "protectors of nature,”

and how many of you just pictured them in a forest somewhere? Sure, there could be Druids of the mountains or

desert (which actually sounds like a really cool character idea), but if ten

players made ten Druids, nine of them would be forest-themed.

In D&D, forests can be somewhat

dangerous, but tend to have nowhere near the threat density of a dungeon. Forests

can contain predators, monsters, bandits, and the like, but in any campaign

I’ve been a part of, they’re encountered on the order of once or twice a day, not every few minutes, as you would

in a dungeon.

It is possible to get lost in a forest, but

navigation is typically handled by a skill check or abstract statements of

intent, such as “we head north until we find the ruined temple,”

rather than “I’ll take a left around this tree, then a right around that

tree,” and so on.

Forests can

be the adventure locale itself, but far more commonly, a forest is more like a

sea connecting “points of interest"—washed out bridges, troll caves,

ruined temples, sacred groves, and so on. Those

areas are the adventure locations, and often come with their own maps—they may,

in fact, be dungeons themselves. These points of interest might be sources of

information or resources, might be quest-givers, skill challenges, battles,

treasure, or any combination of the above.

Forests might feature an occasional choke

point, such as a river with a single safe crossing or a cliff with one shallow

ascent, but by and large permit largely unconstrained (if slow) movement in any

direction. They may have paths or streams that guide movement in certain

directions, but in most cases, cutting it cross-country is an option.

Forests can provide as much assistance as

they do threats. In a forest, hunting and gathering for food is relatively

straightforward, and you’re as likely to encounter a helpful woodsman or benevolent

sprite as a ferocious owlbear. However, if you aren’t trained in Survival (or

the game’s equivalent), then you’re likely as not to eat something poisonous or