Sir Poley's Blog, page 2

July 19, 2020

On the Four Table Legs of Traveller, Leg 3: Character Creation

In part 1 of this series, I described how Mongoose Traveller’s

spaceship mortgage rule becomes the drive for adventure and action in a

spacefaring sandbox, and the ‘autonomous’ gameplay loop that follows.

In part 2,

I talked about how Traveller’s Patron

system gives the DM a tool to pull the party out of the 'loop’ and into more

traditional adventures.

In this

part, I’ll talk about Traveller’s unique

character creation system, and how it supports the previous two systems.

Character Creation

Traveller’s character creation is weird, and it was the first thing house-ruled away by my old DM—and

I can see why.

Traveller character creation is a minigame of sorts, in which

you first generate ability scores (much like in D&D), then pick a career.

You make a stat check to qualify for the career, one to 'survive’ the career

(more on this later), and one to advance. Every time you qualify for the career

and/or advance, you get a random skill or stat boost from a table related to

your training. In the Army and Marines, for example, you’re very likely to get

combat-related skills, while as a Merchant you’re more likely to get something

like Broker or Admin (which tend to be more useful, surprisingly).

You also

roll once on a life event table, in which your character might fall in or out

of love, make friends or enemies, study abroad, and so on.

You then

advance four years in age and try again, and continue for as long as you want.

If your character gets too old, they start suffering physical ability score

consequences, though these can be bought off with semi-legal anti-aging meds,

the consequence of which is starting with high amounts of medical debt.

If you fail

a survival roll, you’re permanently expelled from your career (but can start

another one), and often suffer major debilitating

injuries in the form of sweeping permanent ability score damage, though this

can be bought off by going deep into medical debt. It’s technically possible to

die in character creation if your physical ability scores are reduced to zero

in this way, in which case you would start over. For that to happen, the player

would have to decline treatment—basically, they’re making a choice to give up

and start over. This is a kind of extreme “safety net” against

playing truly worthless characters, I suppose, though I haven’t seen it happen

yet.

This way of

creating characters is shockingly different

from any that I’ve seen before. The character that you end creation with might

not have any resemblance at all to what you sat down and intended to create,

which was a huge source of frustration, as a player, in my last two campaigns.

It’s more common than not to, for example, come up with a concept for a dashing

space pilot and end up with a 98 year-old-that-looks-34 white-collar office

worker who’s got a laundry list of grievances against various corporations who

have fired him over the years.

When I’ve

seen this system work well, it’s because players went into it with different

expectations that they would in D&D. For a D&D campaign, you usually

come to the table with a more-or-less fully-fledged character concept, then

roll stats (or point-buy) and fill in the boxes. In Traveller, it’s more like spinning a wheel and seeing what you’ll

get.

For the kind of campaign that Traveller assumes, however, this is perfect, and here’s why.

First, it sets the tone of the campaign. Traveller is very different from most

D&D-esque RPGs. It doesn’t provide any guidance for or benefit from, for

example, balanced encounters. By creating mechanically unbalanced,

unpredictable characters, it is telling the players from the start that there are sharp

edges to this game and they have to stay on their toes.

Second, it generates crucially important NPCs for

the campaign. Those life events—and some fail-to-survive rolls—often create

allies, enemies, rivals, and contacts: NPCs that are guaranteed to be met

during the campaign. The book provides tips to the DM to ensure that these NPCs

have access to spaceships, as they can be found on the random encounter tables.

But here’s the fun bit: the Player will be just

as pissed at their rival, Captain Morgensen (or whatever) as their

character is supposed to be, as he was (according to the events table)

instrumental in getting them fired from their career as a space scout. By

generating these characters during character creation’s life-simulation, it

gives them a real, emotional connection that leads to a lot of fun during play.

These NPCs can easily function as Patrons (which, as explained in part 2, are

the keys to adventure), or can provide paths to Patrons.

Third, it has the potential to start the characters

massively in debt. The clear optimal path in character creation is to pay

off any injuries by going into medical debt, and chug analgesic anti-aging

pills like they’re Skittles in order to keep advancing down your career paths,

or start new ones. As explained in part 1, Traveller’s 'loop’ functions best when the PCs are swimming in as

much debt as possible. The more debt, the more motivation to travel, and thus

the more space pirates and space dragons and space princesses and whatever that

they’ll meet.

Fourth, it familiarizes them with the setting. The

book provides quite a few career path options to the Players, and uses the same

to generate its NPCs. Thus, just by reading through the career path options

available to them, Players learn a lot about the world of Traveller and the kinds of people they might meet, without having

to read lengthy setting handouts or pages and pages of lore or anything like

that.

Fifth, it creates gaps in the party’s expertise,

which encourages hiring NPCs. It’s virtually impossible to end up with an

adventuring party that can cover every skill required to operate a spaceship,

for example. This encourages hiring NPC crewmembers to fill in those gaps,

which really helps make Traveller 'work’.

A lot of the party’s time is going to be spent on their spaceship, so the more

people who are on there, the better from a roleplaying standpoint. Also,

That said,

it’s not perfect, as…

Mechanically,

the main issue that’s come up with Traveller’s

character creation is that it’s entirely possible for the party to be missing

one or more vital skills, or for a character to be lacking something that would

be key to making them 'work’. Traveller’s basic dice mechanics harshly penalize untrained skill checks

compared to attempting even slightly-trained ones, and some roles can’t be

easily filled in by NPC crewmembers. If your character never rolls to learn the

Gun Combat skill, for example, they’ll more likely than not miss every attack

they make in the whole campaign. The party

can overcome this by hiring marines, for example, but the player might still be bored every time a

gunfight starts.

This can be

mitigated by, say, letting that player control their hired NPCs in combat

directly, but as the game doesn’t really provide a lot of guidance for who plays hired NPCs (the DM? the player

that hired them? The party as a whole, by vote?), the DM and player will have

to come up with their own solution. Since they might not even realize that

there is a problem that needs to be

solved, this can easily lead to traps (for example, if the DM assumes full

control over hired NPCs, many battles will lead to the DM just rolling checks against

himself/herself over and over in front of an audience) that generate

frustration.

Mechanics

aside, there are some narrative implications for character creation that might

strike many Players as quite weird. Most D&D

Players default to making their adventurers whatever their races’ equivalent of

early-20s is. Sometimes there’s an old wizard thrown in to spice things up, but

I’d say 9-in-10 characters I’ve seen are 'college-aged.’

Traveller strongly rewards old characters. Sometimes very old. Don’t be surprised if the

average age of the Traveller

characters is the same as the summed age

of all of your Players. This isn’t necessarily bad—immortal, eternally-young

sci-fi characters are kinda neat—but it’s also pretty limiting, and may not be

within the Players’ expectations. If a Player wants to make a character who’s a

young hotshot just starting out, the rules will punish them severely. They’ll have virtually no

skills, no money (or debt!), no ship shares (units that track ownership of the spaceship),

and no NPC connections.

I’m not

going to change these rules until I’m more familiar with the system, but my gut

says that many of the game’s skills (such as Computers, Comms, and Sensors, or

the two skills that govern two different, but similar, kinds of

environmentally-sealed armour) could be consolidated to reduce the odds of a

missing skill torpedoing a character. I also think flexibly passing back and

forth control of hired NPCs between the DM and Players will solve a lot of

problems, but deciding on the fly who is in control in a given scenario will

probably take some experience as a DM. I’m vaguely aware that there’s a second edition of Mongoose Traveller, which may have done some of these things, but I haven’t played it and as such can’t comment on it.

I think for

a satisfying experience, you have to make it clear to your Players not to try to build their characters to

a pre-imagined concept, but rather come up with a concept as they play through

their character’s life. Also, tell them upfront that, in this particular sci-fi

universe, anti-aging technology has allowed for the rich and powerful to stay eternally

young, and that they can expect to have already retired from one or more full careers before the campaign even

begins.

July 18, 2020

On the Four Table Legs of Traveller, Leg 2: Patrons

In part 1

of this series, I described how Mongoose Traveller’s

spaceship mortgage rule becomes the drive for adventure and action in a

spacefaring sandbox, and the ‘autonomous’ gameplay loop that follows.

In this

part, I’ll talk about the Patrons—questgivers—that are baked into Traveller’s gameplay loop and provide

opportunities for more 'traditional’ (that is, pre-scripted) adventures.

Patrons

are, essentially, adventure hooks. The 'default’ premise is that an NPC offers

to hire the party for a job (the reward for which is scaled to the PC’s

spaceship’s cargo hold, so is always competitive with trading for money

making). The job rarely goes as planned, and the patron is rarely on the

up-and-up, so various twists and turns are ensured as the party attempts to

complete the job. These jobs usually require putting the trade 'loop’ on hold

and doing something else (in fact, they’re

virtually the only incentive to get out of your spaceship) and are basically

the gateway to all gameplay that doesn’t involve trading, pirates, and FTL

travel.

“Patron”

is literally entry in Traveller’s

random encounter tables, which provides a way for them to enter the campaign,

but it’s also the kind of thing that can easily just be included by the DM,

regardless of what the table says.

Traveller comes with a handful of

pre-made patrons, plus tables for generating your own, though I think, as

implemented, it’s actually the weakest part of the game’s procedural content

generation, as the ones provided aren’t tailored in any way to the subsector

involved. Additionally, each one could really use several pages of additional

information (for example, “First Lander Thu, Miner,” comes to the

party to ask them to investigate attacks made on his nomadic asteroid mining

clan…

…and that’s really all the guidance the DM gets.

Investigating an attack like that is way beyond

my ability to improvise in real-time at the table. I would need maps,

descriptions of supporting NPCs, clues, red herrings, space stations, and who

knows what else to run that around the table.

So this is a case where, as a DM, you kind of have to roll

up your sleeves and do traditional RPG-esque prep: writing adventures, mapping

derelict space stations, planning mysteries, and so on. This obviously takes a

lot of work, so you can’t easily have dozens and dozens of these up your

sleeves. This is why I like to pad out my Patrons with…

Like

everyone else in the world, I saw the

Mandalorean this year, so had bounty hunters on the mind. I realized the

need for a quick and dirty Patron-replacement (as, again, Patrons are a lot of

work that I’m just not up to these days beyond very sparingly), so introduced

the concept of a “bounty ticket.” This is my first Traveller “house rule,” though

in many ways, it’s more like a campaign setting quirk.

Pictured: bounty

tickets. Each is the size of a playing card, and I keep them in a little folder

intended for holding magic cards and stuff.

Bounty

tickets are Player handouts. Nothing generates excitement like passing around a

paper handout. In-game, they’re essentially wanted-posters that are faxed

directly to the spaceships of bounty hunters and travellers as they’re issued

(meaning that I literally pull out the card and give it to the players as,

in-game, it prints out on their ship’s bridge). These involve much less prep than patrons (most of my

Bounty Tickets are literally “go here, beat this guy, bring him/her back

to this location”). For most of these, I don’t have any DM notes other

than the card itself (they usually give enough game information, like location

and spaceship classes, that I can make up the narrative stuff on the fly). A

few more complex ones have a few lines of notes in my binder about twists,

secrets, ambushes, etc., but I mostly keep it pretty minimal. This isn’t

necessarily a recommendation, it’s just something that I know about myself as

DM: I’m pretty good at making up NPC personalities on the fly, but not names (I

once ran an urban fantasy campaign in which I had five NPCs named

“Frank” or “Frankie”) or stats (except in D&D 3.5

specifically, because I was very cool in high school and as such have the text

of that game imprinted onto my immortal soul).

I really

went paper-crafts crazy the other day and made a bunch of little handout cards

(some with emails to the PC from their contacts/rivals, some with stats for

various commonly-occurring spacecraft and stuff. I was about to print out a

little card for each weapon in the rulebook before I made myself stop). The

other relevant ones are 'encounter cards,’ which are basically pre-generated

random encounters/events that are a little more complex than the ones that

result from the table. These are written with an audience of me in mind, so use

shorthand and skim over bits that I know I’m confident improvising around the

table.

None of

these are technically 'patrons’, but all serve the same purpose of injecting

hand-made content into the game’s procedural content generation to keep things

fresh.

Crucial to making Patrons (and “Patrons”)

work is scaling the rewards correctly. Contrary to most of my DM instincts,

this means erring on the side of too much

money rather than too little. In D&D, too high of a reward leads to

characters that get too powerful, while too low of a reward can be easily

compensated for by the DM later with more generous treasure. In Traveller, the prize for doing the task

has to be higher than (or at least comparable to) what the party could make

doing trading in that same amount of in-game time, or they literally won’t be

able to afford going on the adventure.

The book recommends something like 1,000-2,000cr per ton of cargo on the PC’s

ship per week of work needed, which is a good starting place, but I’d add even

more if the job requires space combat (as damage to spaceships can be very

expensive, and worse, time-consuming, to repair). That’s why the rewards for my

bounty tickets are quite high; most of them involve risking the PCs’ spaceship

to achieve.

In my

experience, there’s so many ultra-expensive things in Traveller for PCs to waste/spend money on that you shouldn’t overly

worry about giving them too much money all in one go. Meaningful spaceship

upgrades are in the millions of credits, and there’s almost always something on

the ship that can be improved, so that money will leave their pockets soon

enough.

Patrons

(which are, by default, encountered simply through travelling) add a sub-loop

to the Traveller gameplay 'loop’.

They lead to adventures (which can include anything:

Fencing, fighting, torture, revenge, giants,

monsters, chases, escapes, true love,

miracles…) but that ultimately deposits the party back in the core loop,

ideally with their wallets padded with a huge cash reward (which will quickly

be taken by the bank).

Essentially, this is how you include anything in a Traveller campaign that can’t be easily

generated on a random table. Unlike in most other RPGs, this is more like a

spice, added sparingly, rather than parmesan cheese, which is eaten in a 1:1

ratio with the noodles underneath it. (You guys do that too, right?). The

'loop’ provides enough fun around the table while running on autopilot (DMing

players zooming about the subsector mostly just involves rolling on and

adjudicating the results of random tables) that you can afford to be very

sparing with prep-work on Patrons.

Next up

we’ll cover how Traveller’s (in)famous

character creation ties into these other systems.

July 17, 2020

Comparison between my usual number of notes and the one in which...

Comparison between my usual number of notes and the one in which I said black lives matter. Pretty unexpected. Some of my commenters–you know who you are–can take a hike.

On the Four Table Legs of Traveller, Leg 1:

Mortgages

Mongoose Traveller’s starship mortgage-payment-system

is the most brilliant game mechanic I’ve ever encountered, as a DM. It’s also the

first rule I’d ignore if I wasn’t consciously trying to play the game exactly

how it’s described in the book.

I’ve been

involved in two Traveller campaigns

in the past as a player (both with the same DM), and am currently DMing a

third. All of them are using Mongoose’s first edition. I’ve never played any

other edition of traveller, and know almost nothing about the history of the

game. I don’t know which mechanics are unique to this edition of Traveller and which

have been around for decades.

In the

campaigns in which I was a player, I think the DM was continually frustrated

with the rules of the game. He wanted to run a tight, story-focused campaign

and picked up Traveller assuming it would be, essentially, D&D in space. For

his second campaign, he chopped out huge chunks of the ruleset and replaced it

with homebrew ones, removing space travel and Traveller’s quirky character

creation entirely. This worked for the game he wanted to run (he’s an extraordinarily

talented DM), but I think we all came away feeling pretty lukewarm about the

actual rules.

Bored out

of my mind in lockdown, desperate for anything to shake up the daily routine, I

picked up the copy of Traveller

that had been sitting on my bookshelf, untouched, and skimmed through it. In a

mood of “I’ll humour this weird rulebook,” I followed the random

subsector creation chapter to the letter,

creating a surprisingly-well fleshed out chunk of space to play around in.

It was then that I realized I’d never actually played Traveller. So I dragged my partner along

in an experiment: let’s play Traveller,

exactly how it is described in the book, no matter how flat-out insane the

rules seem to be. I will only consider houseruling or changing a rule once

we’ve both figured out what it’s for. I learned a ton in this experiment, so, during my kid’s naps (oh, right, I have

a daughter now, that’s where I disappeared to, Internet), I’ll write about what

I’ve learned.

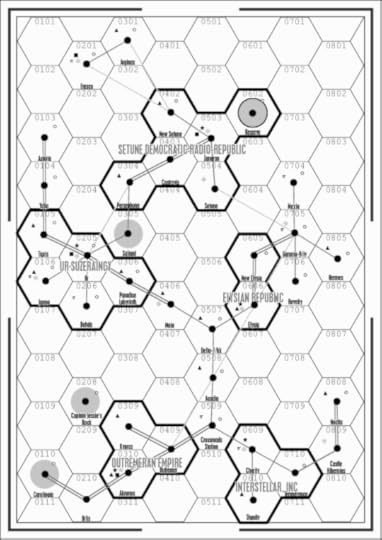

(The Carlia Subsector.

Not pictured: along with this map is a LONG word document describing the

atmosphere, gravity, population, tech level, cultural quirks, government, etc.

of the main world in each of these systems, plus a huge table of the price of

dozens of trade goods on each planet. These, it turns out, are crucial game

aids. I’ll get into them later.)

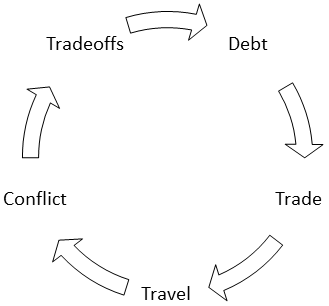

Traveller, I’ve learned, is a table held up by four

legs: Finances, Character Creation, Patrons, and Random Encounters. If you

remove any of these legs, the rest of

the game stops working. Following

them, as described, gives you a rip-roaring swashbuckling adventure of fighting

pirates, escaping bounty hunters, smuggling, jailbreaks, and all that good

stuff you want in a campaign—but it happens spontaneously.

I’ll get into it more in detail, but for now, we’re going to talk about finances

in Traveller.

Mortgage Payments

The central

driving mechanic of Traveller is

making mortgage payments for your starship. The assumption is that the player

characters are part-owners of an FTL-capable starship that’s more expensive

than any one person, or any ten people, could ever afford outright. The game

(thankfully) provides a quick way to calculate your starship’s mortgage

payments (something like the value of the ship/240 per month), and for all of

the example ships in the book, gives them to you pre-calculated. In the case of

my solo campaign, my partner owed the bank a whopping 500,000 credits a month

for her Corsair. For scale, that’s the exact

same price as

the single most powerful gun in the game (the “Fusion Gun, Man

Portable”), owed monthly. In

D&D terms, she had to raise the equivalent of a +5 Longsword every. Single. Month.

(In addition to mortgage payments are smaller fees: life

support (i.e., food and water), crew salaries, fuel, and ship maintenance, but

the mortgage is by far the largest single expense, so that’s what I’ll focus on).

I started

my partner out with a fueled up and fully-crewed ship (we used pre-generated

NPC stats from the middle of the book for her crew, plus an NPC who was

generated during her character creation, which I’ll get into later). Character

creation started her with 10,000 credits, and I told her she had until the end

of the month to multiply that by fifty times.

The fastest

way by far in Traveller to make money

is to interact with the very well fleshed-out trade rules. Each spaceship has a

certain amount of tons of cargo it can carry, and each world has a list of

trade goods for sale at various prices. So the clear way to raise that 500

grand was to speculatively buy trade goods, pick up passengers and freight,

deliver mail, and so on. These rules are generous;

by stacking modifiers, it’s possible to reliably quadruple your principal every

time you reach a new planet (which happens every week).

I think my

old DM severely nerfed the trade rules (he also didn’t enforce mortgage

payments, leaving them on the cutting room floor like D&D’s Encumbrance

rules) due to this seemingly-unbalanced generosity. Again: the best gun in the

game is 500,000 credits—so how on earth can a system that lets you make

hundreds, even millions, of credits by trading stand?

Well, it

turns out, the bank simply taking 95% of your player’s earnings every month

severely dampens potentially-snowballing nonlinear growth, so my partner and I

never saw the kind of wealth explosion that looks inevitable from the rules as

written, despite her scraping together everything she could do maximize profits.

In all the time we’ve been playing, despite having already made millions of

credits, she actually hasn’t been able to buy a gun better than her starting

laser pistol, or, in fact, any armour at all. I’ll get to why in a moment,

because the most important thing about the trade system is that…

Garden

worlds sell cheap food. High-population worlds buy food for a high price.

High-population worlds sell manufactured goods that are in high-demand on

non-industrial worlds, and so on. In a quest to maximize profits, the party was

locked into a continual tour of the subsector I generated earlier, constantly

moving from place to place. Staying put for any length of time meant letting

time trickle away (time that could be

spent raking in cash for crippling mortgage payments), so that wasn’t an

option. What wound up happening was that the party went on a self-guided tour

of the subsector, stopping in at colourful worlds I’d generated earlier. This

happened entirely without me, as DM, having to dangle bait in front of the party

the way that I always have to in D&D. Travel is good, because…

I’ve

already spoken at length on the subject of random encounters [here], but Traveller really builds the game around

random tables in an elegant way. Every time the party jumps from one world to

another, there’s a chance they’ll get waylaid by pirates (the rulebook has a

fun, albeit hidden, ‘pirate table’ that describes different tricks and hijinks

that pirates use to attack). 'Pirates’ in Traveller

are spaceship owners unable to pay their mortgages by legitimate means, so turn

to piracy. The fact that the party is always

carrying their life savings in trade commodities whenever they travel around

makes them a prime target for piracy, and leads to combat with stakes beyond

“fight till everyone’s dead.” The pirates aren’t orcs, and don’t want

to kill the players for no reason. They want to take their cargo and get away

as quickly as possible, suffering the least damage as possible, and the players

want the opposite. Thus: pre-combat negotiations, tricks, hijinks (my partner,

carrying a cargo of “domestic goods,” chose to have her crew throw

individual toasters out of the cargo bay each in different directions to ensure

that the pirates had to engage in lengthy EVA-missions to catch them each, thus

allowing her ship to escape without suffering damage).

Traveller’s starship battle rules are fun (and integrate

into boarding actions that results in player-scale combat), and are triggered primarily just by moving around.

Conflict is fun by itself (that’s why combat rules are most of the rules in most games), but in this context, have the

added advantage, as…

Tradeoffs

It became

clear to my partner after her first run-in with pirates that her ship and crew

were under-gunned. While buying powerful weapons and armour is trivially cheap

compared to the amount of money she was raking in through trade (most weapons

cap out at a few thousand credits, and she was moving hundreds of thousands a

week), actually getting her hands on some was another matter.

Good

weapons in Traveller are advanced

ones, which have a high-TL (tech level) rating. These weapons are only

available on high-TL worlds (each world has a TL rating generated in subsector

generation). Making a detour from trading to buy 'adventuring equipment’ wound

up being an extremely costly endeavour,

taking the party weeks out of the way of the most profitable trade route. The closest

world in which these weapons exist also outlaws all weapons (various laws are

generated procedurally as well) which means engaging in black market smuggling

(which is fleshed out in the rules) and risks run-ins with the law.

Compounding

this problem was that her Corsair took minor damage in the combat with the

pirates, and the nearest world with a shipyard capable of repairing the ship was

different from, and out of the way of, the high tech world with fancy fusion

guns. Also, getting the ship repaired meant that it would be in drydock for

days or even weeks, which incurs an opportunity cost of almost a million

credits that could have been made during trade…

In her

case, she wound up getting her ship repaired, forgoing arming herself and her

crew, and skirting dangerously close to bankruptcy kicking her heels as her

ship was patched up. There isn’t an easy answer to what she 'ought’ to have

done, which was fun as hell. Further,

as a DM, I wasn’t annoyed that she was 'messing up the plot’ by staying put (or

frustrated that she wasn’t going to my elaborately-plotted narrative that would

occur when she tried to buy black market weapons) because there was no plot. Everything that came about

emerged procedurally.

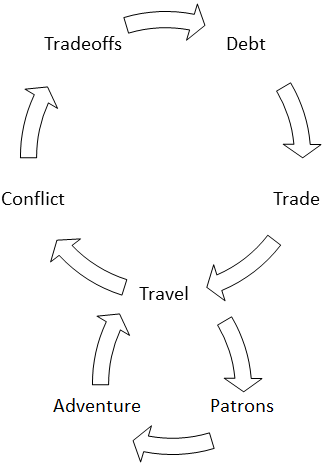

The beating

heart of a Traveller sandbox

campaign is this loop:

Without DM

intervention (or Patrons, which are sort of procedurally-generated adventure

hooks), this loop can sustain a campaign pretty much indefinitely. What this

means as a DM is that any DM-interventions (i.e., adding in pre-written

adventure hooks or encounters or whatever) can be attached to any of these

steps to allow it to come about during play. It also means that if you don’t have any pre-scripted content (to choose

an example completely at random, let’s just say your hypothetical one-year-old

threw your notes in a toilet) you can just sit back and let the loop above take

care of providing entertainment.

To bring

this back to mortgages, if your players don’t have the threat of having their

spaceship repossessed by the bank hanging over them like the Doom of Damocles,

then the whole system breaks down, and the DM has to do all the heavy lifting

of providing character motivation to go explore new planets.

Next, we’ll

talk about how Traveller’s patron

system ties into all of this.

June 5, 2020

Black Lives Matter. Or: Why Politics Belongs in the Hobby

VarianceHammer wrote this much better than I could.

January 1, 2019

On Overland Travel, Part 3: Random Encounters

In the first article in this series, I set

out to prove Vaarsuvius wrong and to salvage Random Encounters in overland

travel.

In the second article in this series, I proposed

some additional requirements for having a Long Rest that would allow Random

Encounters to have real stakes.

Now, I’m going to tackle the Random Encounters

themselves.

Let’s start with the Into the Living Library Wandering Monster table, as seen in the On

Wandering Monsters series—the one that looks like this:

This type of table will work as-is for overland

encounters, though of course you would change the specific entries depending on

the current biome (i.e., instead of a Gelatinous Cube, you might have a

ferocious Owlbear). We don’t need to use the version that includes traps,

because traps tend to be a feature of dungeons, rather than wildernesses.

This is a tricky question. More entries on

the Random Encounter table isn’t necessarily better, as it increases the odds

that a given monster is encountered before it has been foreshadowed. It also increases

the odds that a heavily foreshadowed Owlbear attack leads to an encounter with

a Giant Badger.

I would say that the number of entries you

want to put in depends on how much use you expect the region to get. Four rows

is probably the minimum you can have in a viable chart, but I wouldn’t go

higher than eight unless the entire campaign is set there. If you feel the need

to include more monsters, instead try splitting the region into sub-regions

with different tables, each with four to eight entries.

Remember that since each row has five

filled in columns (plus a blank one), it will take at minimum five Random Encounter checks to see every piece of

content created per row. If you only call for one encounter check per day, then

a four-creature table will give you a minimum

of 20-days of adventure without the party discovering everything. If an area

becomes more important to the campaign than you’d first anticipated, you can

always increase the size of the table later.

Encounters

If the region we’re describing is close to

civilization, we want the party to have a chance of bumping into a caravan or

passing pilgrims or the like. This is where we can afford to cheat: friendly encounters

don’t need to be foreshadowed, because they act as foreshadowing for each

other. Once you’ve found some farmers heading to market, you definitely won’t

be surprised if, the next day, you meet some lumberjacks.

The bottom row or two on your Random

Encounter table can (if this region represents a fairly civilized one) be made

up of encounters with NPCs or other elements of civilization, each in their own

cell, whether or not the column is “ENCOUNTER” or “HINT” or

whatever. For example:

An encounter with lumberjacks might be

nothing more than a friendly wave, but it might also be an opportunity to ask

for directions, barter for some food, or, in the worst case, desperately ask

plea for help. An encounter with the caravan or peddler might prove

particularly fruitful as an opportunity to buy or sell goods.

That’s all I’ve got for now on this subject!

Here’s a summary of what I’ve found so far:

you want to have Random Encounters in your game but have struggled to make them

‘work,’ you’ll likely need to tweak the resting/recovery rules in order to add

a dungeon-like resource management layer of tension to these encounters.One

solution is to require real comfort and shelter to perform a long rest, such as

a wayside inn or a house with a welcoming host, but otherwise leave the resting

rules unchanged.Once

you have made this tweak, you can either use a conventional Random Encounter

table, or something like the Wandering Monsters with Foreshadowing tables as

described in my On Wandering Monsters series.Don’t

forget to add non-combat encounters to the table as well, especially when close

to civilization!

December 27, 2018

On Overland Travel, Part 2: Long and Short Rests

In the first article in this series, I set

out to prove Vaarsuvius wrong, to salvage random encounters in overland travel.

I found that the problem lies in the interaction of travel, Random Encounters,

and resting, which is what I’ll tackle in this article.

Part

4 of On Wandering Monsters lays out a couple of ways in which the use of

Wandering Monsters in dungeons can smooth out some of the roughness between

classes, and part 2 discussed how they can be used to further, rather than

distract from, the narrative. One would think that all of that would apply equally

well to overland Random Encounters, except that, due to the interaction of certain

game mechanics, these battles are a tedious waste of time because the party is

always going into them at full power, and always heals immediately after. It’s

a standard rule of writing that you need to have stakes to have tension and

that tension is the soul of drama, with the corollary being that no stakes = no

tension = no drama = half the players will be on their phones during overland

travel.

So, what can we do to solve this problem?

One answer, I think, is to make overland travel work, in some ways, more like a

dungeon crawl—not in the sense of filling the woods with traps and hallways,

but rather in imposing some resource management complications. The first step

of which is that…

Prevented

The main reason why dungeons are gripping

is because it is very challenging and dangerous, if not impossible, to attempt

a long rest without losing substantial progress (that is, leaving the dungeon).

If we change the rules and/or assumptions

to prevent long rests between Random Encounters, just as they are impossible to

use between Wandering Monster encounters in dungeons, we can replicate the same

resource-conservation and increasing tension effect. So let’s try and find a simple,

elegant tweak to the rules that gives us the desired behaviour.

Realism” Approach

The Dungeon

Master’s Guide has an optional rule that touches on what we’re looking for:

Gritty Realism

This variant

uses a short rest of 8 hours and a long rest of 7 days. This puts the breaks on

the campaign, requiring players to carefully judge the benefits and drawbacks

of combat. Characters can’t afford to engage in too many battles in a row, and

all adventuring requires careful planning.Dungeon Master’s Guide 5th Edition, 2014. p. 267.

While I think the goals of this rule are

the same as ours, I don’t think this is the solution for us. If you tell the

party they need to stay put for 7 days to gain a long rest, I can guarantee

that they’ll be tempted to just bring 8 times as many trail rations and stop

for a week after every single battle. This puts too great a conflict between

meta-rewards and the narrative, as breaking for a week after every day of

hiking is hardly heroism. This houserule also prevents the use of short rests

in the dungeon, which harshly penalizes martial characters for reasons

described in my Wandering Monster series.

If D&D doesn’t provide variant rules

that serve our purposes, it’s time to turn to other sources of inspiration,

such as….

In Skyrim,

resting requires a bed or bedroll. These are only placed sparingly in the

world, often requiring stumbling into a wilderness campsite (which rewards exploration)

or staying at an inn (which are few and far between).

Obviously the bedroll solution is right out,

as characters carry bedrolls around with them—campsites in D&D aren’t

static elements to be discovered, they’re items on the inventory sheet.

Requiring a bed could work, but it provides a number of problems. Putting

myself into the shoes of a Player, I can already imagine the arguments I’d use

against the GM who imposed this rule:

about pre-historical civilizations that didn’t use beds? Did they simply never

heal their injuries? This makes no sense.What

if I just drag a bed around with me?Okay,

but what if it was on a wagon?What

do you mean my RV wagon can’t make it up the mountain pass? I’ll go around. I

don’t care that it takes six months more. The Druid can forage for free food.

Even reasonable, non-disruptive players would end up asking these questions, and I think with this rule we’d simply be trading out one set of detrimental

incentives (that is, to simply nuke every enemy with every spell and then take

a nap) with another set (those listed above). What if instead of simply a bed,

you need something a little more intangible? Such as…

All of the problems of the above involve lugging

a bed into a context that doesn’t typically have beds, so what if we say you

need the full context? A few years ago, I hiked the West Coast Trail, an

adventure which took my group seven days. I can guarantee that sleeping on a

‘bedroll’ in a tent is not as

relaxing or rejuvenating as sleeping in a real bed. It’s not just the sleep,

it’s the food—there is a world of difference between perfectly-nutritious 'trail

rations’ and a burger. Part of this is psychological, which doesn’t mean it

should be discounted—many of the in-game benefits of a long rest are mental

(recovering spells, for instance), not physical. By the end of our hike, our

bodies were in shambles. We had blisters, bruises, cuts, sunburns, and we

smelled terrible—all this despite 'resting’ every night, often for

substantially more than 8 hours. But one shower, an unhealthy amount of pizza,

and a night in a bed later, we felt miraculously cured—much like an adventurer

does after a long rest.

So what if, without a certain degree of

comfort and security, any length of rest simply counts as a Short Rest?

Let’s break down some elements of comfort

that seem relevant to a fantasy adventure:

house or inn is ideal, but particularly hospitable cave will do. These

locations are few and far between, and may be popular rest stops for other travelers

(thus discoverable by asking around in town), or are already the lairs of

monsters or bandits.Hot Food—Specifically not 'trail rations.’ Something baked,

cooked, boiled, or fried over a fire or stove.A Comfortable Bed—More than just a bedroll on the

rocks. It can be a real bed, a cot, a pile of hay, or the like.Hygiene—Clothes have to be washed and hung out to dry,

some stubble might need shaving (depending on race, gender, culture, and

preference), and bodies need to be cleaned. Soap is preferred.Safety—The characters have to feel safe as they rest. Simply being

safe (such as posting a watch and avoiding encounters) isn’t enough; actual

relaxation must be possible. If the party has to take substantial steps to

ensure their physical safety, then it doesn’t count as a long rest.

The goal here is that when the party spots

a roadsign inn ahead, the wizard says “thank god, a hot bath.” Sprinkling roadside inns and friendly

farmsteads along the road is something the GM can control, so the difficulty of

overland travel can easily be adjusted by increasing or decreasing the rate of

pit-stops.

Narratively, this approach fits with much

of D&D’s source fiction. Think about Bree, Rivendel, Beorn’s house,

Lothlorien—adventures in both The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit are punctuated by breaks at

memorable pit stops, before which, our heroes are quite ragged. This narrative

element is entirely lacking in D&D, as, from a mechanical standpoint, whether

you’re sleeping in a five star hotel or out in a rainy night, all rest is

equal.

There’s still a few cracks to work out in

this system—for instance, as Milo is fond of pointing out, Prestidigitation negates the need for showers and laundry, players

will devise means to dragging beds out with them, and rangers will start

bagging deer to replace their trail rations. Also, we don’t yet have an elegant

solution allowing long rests before dungeons, but I think it’s a start.

Next

Up: On Overland Travel, Part III: Random Encounters

December 25, 2018

On Overland Travel, Part 1: Can We Prove Vaarsuvius Wrong?

Rich Burlew’s Order of the

Stick #145 rather accurately expresses

the nature of the problem with Random Encounters when travelling overland. Go

read the strip before continuing; it only takes a second and it’s worth it. You

don’t have to know anything else about the series to understand the point made

in this particular page.

In the strip, Vaarsuvius rather

convincingly demonstrates (far better than I ever could) exactly why Random Encounters

are a waste of time—but do they have

to be that way? If they were such a waste of time, why are they then such a

staple of the genre? Perhaps, like Wandering Monsters and traps, the mechanic

can be salvaged once we dive in and understand why it’s there in the first

place.

My approach to Wandering Monsters in

dungeons—which you can read here—won’t

work for Random Encounters travelling overland because of the nature of resting

and healing in D&D. Wandering Monsters represent battles of attrition that

wear down spellcasters faster than fighters, and also provide a simple way to

simulate an entire ecosystem without using a single iota of the GM’s

brainpower. However, if the party has the opportunity to rest between every

single Random Encounter, they quickly become a waste of time for the reasons

mentioned above—the party will blow all of their powerful, limited-use

abilities, then simply heal to full before the next battle. Victory is both

free and assured, so the GM might as well save everyone some time and roll on a

random-XP table every day of travel.

But before we decide to ‘fix’ Random

Encounters, we have to know why they

exist in the first place.

Note:

For the purposes of article, “Random

Encounters” refers to monsters, NPCs, and other stuff stumbled into in an overland

journey measured in days, while “Wandering Monsters” refers to

monsters, NPCs, and other stuff stumbled into in a dungeon crawl, typically

measured in minutes or hours. I believe this is the terminology used in D&D

itself, though the phrases have always been used interchangeably in my gaming

group, and maybe in yours too.

I believe that every game mechanic was

created for a reason. Not all of them were necessarily well thought out, or

solve the problem they were intended to elegantly. For some, like Wandering

Monsters, the reason is long forgotten, but the mechanic lingers, leaving

people scratching their heads and simply houseruling it out.

Random Encounters are one of a slew of mechanics,

such as Wandering Monsters, Treasure Tables, and Rumour Tables, that involve

the GM secretly rolling on a secret table to determine a result that they could

just make up by themselves and no-one would know—a practice which, I believe,

has become increasingly popular. GMs will build bespoke treasure hoards and

encountered tailored to the party, rather than relying on a random generator.

There’s nothing wrong with doing this, and if it works for you, go for it, but there’s

a reason all those tables and random generators exist in the first place.

The first, and most obvious, is that procedurally generating content makes the

GM’s job easier. It’s much easier to roll some dice and be given an answer

than to come up with one yourself. This makes GMing, which is already an

intimidating role, much more accessible.

The second, and most controversial, is that

procedurally generating content makes

the GM into a player. Neither the GM nor the players know what will happen

when the dice hit the table, so both are holding their breaths in suspense. The

GM, now, is on the side of the players—worrying that a powerful monster will be

generated, hoping for good treasure, and so on. This can reduce the sometimes adversarial

nature of the relationship between GM and player, because both players and GM

know that the GM isn’t punishing the players by having them stumble into a dragon’s

cave—the game did that to them.

The third, and most subtle, is that it means the PCs aren’t the centre of the

universe. When every encounter isn’t custom-tailored to the party’s exact

level and makeup, the entire nature of the universe changes. This gamey-seeming

mechanic can actually make enhance

verisimilitude by realistically populating the world with “too hard”

and “too easy” encounters. Much like with Wandering Monsters, a

cleverly built Random Encounter table can simulate a thriving ecosystem without

diverting any of the GM’s precious attention.

There are a few other benefits to Random

Encounter specifically, as well. They can make long journeys actually feel

longer than short ones, and give an incentive to find faster methods of travel.

I’ve seen many players scoff at buying horses or hiring ships to travel, because

it doesn’t actually matter how long it takes to get from point A to point B

in-game. Regular Random Encounter checks makes travelling on horseback a

substantially safer proposition. Additionally, character classes that are

experts at wilderness survival, such as rangers and druids, might be given more

opportunities to shine. Rangers in particular need every advantage they can

get.

The problem lies not within Random

Encounters themselves, nor in resting per

se, but in the interaction between them. This leaves us three options: give

up, change the encounters, or change resting.

Give Up

If we just get rid of overland encounters

altogether, the problem is solved. This is a perfectly acceptable solution—it’s

the one espoused by Vaarsuvius earlier—and it’s basically what I’ve been doing

for years as GM, just like I gave up on traps and Wandering Monsters.

Of course, it comes with a heavy set of

downsides. Wandering Monsters, as I mentioned in my On Wandering Monsters

series, have a slew of mechanical and narrative benefits. Abandoning traps

means unfairly shafting the Rogue and de-clawing the dungeon. Abandoning Random

Encounters can make overland travel, a staple of the genre, bland and

uninteresting—and can shaft the Ranger and Druid, both of whom are supposed to

be “good at” travel in the way that Rogues are “good at”

dungeons. A good Random Encounter system, similarly, should be able to spice up

overland travel, if we can just get it right this time.

Change the Encounters

Given that they are only encountered every

few days, the party will be going into each battle fully-charged and rearing to

go. This means that the only way to give the battle any stakes is to massively ratchet up the difficulty of

the monster, such that it accounts for the party’s entire daily complement of abilities.

We could also greatly increase the rate of wandering monsters such that there

are six or seven every day, rather than one or two, but the thought of how many

real-world hours would be spent fighting monsters to simulate even a week’s

travel makes me ill. Either of these approaches make every Random Encounters

into a life-or-death battle to the bitter end, which isn’t what I’m looking for

as a general solution, though it might work in some cases.

Change Resting

Generally speaking, taking long rests in

dungeons should be discouraged, if not prevented outright. A single 'delve’

into a dungeon is a resource-management game of judiciously expending spells

and hit points in order to overcome obstacles. Overland journeys have no such

restrictions, allowing healing between every encounter, thus eliminating much

of the “resource management” aspect of the game.

The short rest/long rest dynamic in 5th

edition D&D is a good one, and one baked into every level of the rules, so

changes made to it should be with a light touch. When tweaking things for

overland travel, we don’t want to 'break’ other aspects of the game, like

dungeon crawls or murder mysteries.

If we think of the journey between town and

the dungeon as one “day,” from a resting standpoint, then we can

replicate the “whittling down of spells and hit points” effect that

makes dungeon crawls work. We can keep Random Encounters short and sweet,

because there is no longer any pressure on each individual one to challenge the

party, but rather, to whittle away some of their precious resources. There’s a

lot of specifics to work out, but I think this is the approach that will work

best for a typical D&D campaign.

Next

up: On Overland Travel, Part II: Long Rests and

Short Rests.

August 2, 2018

Harry Potter and the Natural 20 Chapter 74: SD 212: Light Treason, a Harry Potter + Dungeons and Dragons Crossover fanfic | FanFiction

June 29, 2018

Harry Potter and the Natural 20 Chapter 73: SD 20: Auld Reeky, a Harry Potter + Dungeons and Dragons Crossover fanfic | FanFiction

Sir Poley's Blog

- Sir Poley's profile

- 21 followers