Martin Roy Hill's Blog, page 6

February 23, 2015

Strieber's 'Hybrids' a Genre Bending Mix of Sci-Fi and Horror

The aliens came and, finding humans boring, went. Behind them they left extremely advanced alien gene-splicing equipment which a secret U.S. government program uses to create genetically engineered, nearly indestructible soldiers. When the black program is discovered by Congress, however, funding is cut and the hybrids ordered destroyed. Two of the earliest hybrids – a young boy and a girl who are half human – are spared and raised separately as humans. The rest – bizarre, engineered nonhumans – are destroyed. Or are they?

The aliens came and, finding humans boring, went. Behind them they left extremely advanced alien gene-splicing equipment which a secret U.S. government program uses to create genetically engineered, nearly indestructible soldiers. When the black program is discovered by Congress, however, funding is cut and the hybrids ordered destroyed. Two of the earliest hybrids – a young boy and a girl who are half human – are spared and raised separately as humans. The rest – bizarre, engineered nonhumans – are destroyed. Or are they?Decades later, Delta Force officer Mark Bryan and CIA officer Gina Bryan, find themselves allied in a fight against what appears to be a handful of human-skinning alien hybrids. Mark and Gina, despite having spent a night together, are unable to admit to each other the incredible attraction each secretly holds for the other. When the handful of hybrids turns out to be a massive hive of thousands that threatens San Francisco with destruction, Mark and Gina are thrust together and forced to confront the truth that they, too, are hybrids.

In his novel, Hybrids, Whitley Strieber created a thriller that crosses genre lines—a science fiction story with elements of horror. Rooted in classic sci-fi elements like extraterrestrials and scientific technology, Hybrids also has flourishes of skin-crawling creepiness. Mixed in with this literary stew is a heaping helping of heart-pounding suspense.

I have long considered Strieber one of the most imaginative novelists I've ever read. But having read his non-fiction Communion series about his personnel experiences with alien abduction, I have to wonder if Strieber meant Hybrids as less a fanciful work of fiction, and more of a cautionary tale?

February 14, 2015

Salvation and Suspense In Fraternity of the Stone

Drew MacLane was one of the government's best assassins until the day he saw what he believed was a sign from God. For six years, MacLane sought solitary salvation in the confines of a Catholic monastery where he saw and spoke to no one except a little church mouse he called Stuart Little.

Then Stuart mysteriously dies after nibbling part of MacLane's sparse meal. Venturing out of his room, MacLane discovers all of the monastery's residents have been poisoned. The only survivor, he flees the monastery to seek help from the Church.

Hunted by unknown assailants, MacLane becomes entangled in the search for the identity of an assassin known only as Janus who is responsible for the murders of several Catholic priests. Working with a mysterious warrior priest, MacLane struggles to save both his own life and his eternal soul. Eventually he learns in the world of religion, as in the world of espionage, it's frequently difficult to tell the good guys from the bad guys.

Morrell builds a compelling plot that intertwines an ancient group of holy warriors dating back to the Crusades with modern political machinations. MacLane is a literally a tortured soul, forced to kill repeatedly for his own survival while growing more fearful of losing his own salvation with each death. Mixed in with the action and suspense is a detailed narrative of the history of the Catholic Church and its diverse religious orders that is presented with such finesse it never interrupts the flow of the story.

Morrell is considered by many to be the father of the modern thriller. With The Fraternity of the Stone, he retains that honor.

January 25, 2015

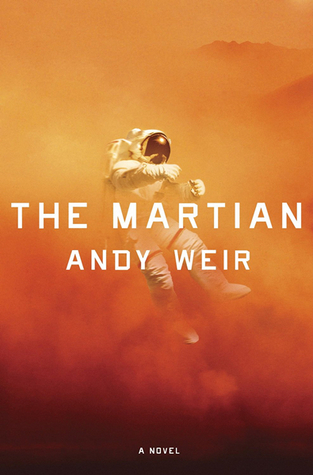

The Martian: Oh, wow, wow, wow.

Wow. Oh, wow.

Wow. Oh, wow.

The Martian by Andy Weir has got to be one of the best novels I've ever read.

You undoubtedly have a good idea what the plot is. American astronaut Mark Whatney is mistakenly left behind on Mars when his landing team makes an emergency evacuation of the planet during a severe sandstorm. But to call this story "Robinson Crusoe on Mars" is too simplistic.

This novel is true science fiction. There are no aliens, no transporters, no warp speed spaceships. Whatney, a mechanical engineer and botanist, uses science, engineering, and farming techniques to stay alive while NASA plans his rescue. Weir goes into great detail about the physics and chemistry Whatney uses to survive, and the engineering and astrophysics NASA uses in its rescue attempt, yet he is never pedantic or boring. On the contrary, this book is breathtakingly suspenseful, witty, and at times laugh-out-loud hilarious. The frustration Whatney experiences as his best laid plans go awry is visceral. The tension produced by the last pages is white-knuckling.

I can't help but recommend this book to anyone who enjoys an intelligent and well-written adventure story.

By the way, did I say 'wow' yet?

January 17, 2015

When a Captain Isn't a Captain: Military Ranks for Writers

I recently read a novel by one of my favorite authors. It

was a great, exciting read, but it was also filled with numerous errors about military

ranks. For instance, one main character was the commanding officer of an American

submarine. The author referred to him correctly as "captain." Unfortunately,

he also repeatedly described the character's rank insignia as "double

bars." Two silver bars are the correct insignia for some captains, but not

all. You see, there are times in the military when a captain is not a captain

but is still a captain.

Clear as mud? No? Well, military ranks never are. And that's

why many authors who have never served in the military get confused and make mistakes

in their writing.

Military rank refers to service members' pay grade. All pay grades

are numbered E-1 through E-9 for enlisted members, W-1 to W-5 for warrant officers,

and O-1 to O-9 for commissioned officers. That's pretty simple. The problem,

however, lies in the fact the different branches have different names for their

pay grades.

Take the example of "captain." In the Navy, a

captain is an O-6, ranking just below a rear admiral. But in the Army, Marine

Corps, and Air Force, an O-6 is called a colonel, which is just below a brigadier

general. Both a Navy captain and a colonel wear silver eagles to denote their

rank, not double bars.

The Army, Marines, and Air Force have captains, too, but

they are only O-3s, way below a Navy

captain. An O-3 in the Navy is called a lieutenant (technically, a lieutenant

senior grade). Army, Marine, and Air Force captains, as well as Navy

lieutenants, wear two silver bars that denote their rank.

Okay, it gets even more confusing now. A Navy officer who

commands vessel is also called the ship's "captain," regardless of

his rank. In the book I mentioned earlier, the commanding officer of the

submarine was correctly referred to as "the captain," but he was not

necessarily a captain by rank. Subs are usually commanded by commanders (O-5).

Commanders wear a silver oak leaf insignia, not double bars or silver eagles.

The Army also has commanders, but they don't necessarily

wear silver oak leafs. In the Army a "commander" commands a unit, and

can be virtually any commissioned rank depending on the size of the unit. See,

it's sort of like being a captain in the Navy when you're not really a captain,

except in the Army you're a commander but not a real commander.

Got it?

Alrighty. Now lets talk about chiefs.

In the Army a “chief” is a warrant officer. A warrant

officer is sort of like a commissioned officer, but smarter. The Navy has

warrant officers, too, but they're called Mister or Miss. (Don't get me started

on what you call a married female warrant officer.) Enlisted personnel have to

salute warrant officers just like they do commissioned officers. The Navy also

has chiefs, but they're enlisted personnel (E-7 to E-9); no one salutes them

but you don't back talk to them either.

The Air Force also

has personnel called chiefs. Like the Navy, they're enlisted personnel. But

unlike Navy chiefs who are chiefs, Air Force chiefs are actually sergeants.

Chief master sergeants. They wear a lot of stripes on their sleeves —a lot of

stripes. The Army and Marine Corps have master sergeants, but not chief master

sergeants. Oh, dearie, no. The Army and Marine Corps instead have sergeant

majors. They also have commissioned officers called majors. One might think a

sergeant major would outrank a simple major — and there are sergeant majors

who believe they do — but they really don't.

All branches of the

military have enlisted personnel who are called "officer" but aren't warrant officers or commissioned

officers. The Army, Marines, and Air Force have non-commissioned officers, also

known as NCOs or noncoms. Now remember, a warrant officer is not technically a

commissioned officer either; he's an officer by warrant. But that doesn't mean

a warrant officer is a non-commissioned officer. No, no, that's only reserved

for enlisted personnel.

The Navy has non-commissioned officers, too, but they're

called petty officers. That does not mean they are smaller than NCOs. You can

refer to a petty officer as "Petty Officer So-and-so," but you cannot

address a corporal or sergeant as "NCO So-and-so." Not allowed!

So you see, military ranks aren't so difficult to understand

after all. Right?

Yeah, right.

January 13, 2015

Coming of Age in a Dystopian Future

In the year 2108, the North American continent has been consolidated

In the year 2108, the North American continent has been consolidated into a North American Commonwealth. Commonwealth, however, is a

misnomer; it's actually a continent-wide oligarchy with a handful of

wealthy residents, a small middle-class population, and massive slums.

The only way out of the slums is to win a lottery for a slot on a colony

ship to some distant planet or to join the military.

Andrew Grayson, the narrator of Marko Kloos' Terms of Enlistment,

chooses the latter. Hoping to get off world by getting a slot in the

NAC Navy or Marines, Grayson instead ends up in the Territorial Army,

the service branch that fights the NAC's earth-bound wars against

enemies both foreign and domestic, including its own citizens.

At

its foundation, Terms of Enlistment is a classic

young-man-comes-of-age-in-war-time story wrapped in a science fiction

novel. A comparison to Robert Heinlein’s classic military sci-fi book Starship Troopers quickly comes to mind. But I actually found myself comparing it to Stephen Crane's The Red Badge of Courage, Anton Myrer's The Big War, or Jim Webb's Fields of Fire pushed forward into the 22nd century.

Kloos

was born in Germany and served in the German army. His talent as a

writer is shown by the fact that he can write so convincingly of what in

this book seems essentially an American military experience. His

description of basic training was so detailed and so familiar to my own

experience, it almost made me nostalgic for the months I spent in boot

camp. I emphasize almost.

Grayson eventually does make it off

world, but not before learning the horrors of combat while fighting his

fellow slum-dwelling citizens in a battle that is a thinly disguised

recreation of the 1993 Battle of Mogadishu in Somalia, made famous by

the book and movie Blackhawk Down. (Kloos acknowledges the

inspiration by calling the chapter describing the battle "Drop Ship

Down.") Recreating the Mogadishu battle in a futuristic Detroit raised

in me poignant questions about our military activity abroad and at home,

especially as I read this book not long after the militarized response

of the Ferguson, Missouri police force to public demonstrations against

police shootings.

Terms of Enlistment is the first

installment in the author's Frontlines series. Kloos is a talented

writer and, if this book is any indication of that talent, the series

should be a great success.

December 21, 2014

Brotherly Love and Revenge: 'Brotherhood of the Rose'

Having lost his father in WWII, many of David Morrell’s thrillers involve themes dealing with father-son relationships. In First Blood, it was the relationship between Vietnam veteran Rambo and Sheriff Teasle, a veteran of the Korean War. In Last Reveille, it was the relationship between a young recruit and an old veteran taking part in Gen. John Pershing’s Punitive Expedition against Pancho Villa in 1916.

Having lost his father in WWII, many of David Morrell’s thrillers involve themes dealing with father-son relationships. In First Blood, it was the relationship between Vietnam veteran Rambo and Sheriff Teasle, a veteran of the Korean War. In Last Reveille, it was the relationship between a young recruit and an old veteran taking part in Gen. John Pershing’s Punitive Expedition against Pancho Villa in 1916.In his Cold War espionage thriller, Brotherhood of the Rose, Morrell again returns to this familial theme with a plot revolving around a father’s betrayal of his sons. Saul and Chris are orphans who meet in a military school, and are raised by a mysterious foster father named Elliot. A high-ranking CIA official, Elliot raises the boys to be highly skilled assassins. In turn, both sons are devoted to the only father either have ever known. But when Elliot sets up Saul to take the fall for the assassination of a friend of the U.S. president, he discovers the love his sons have for each other is greater than their love for him.

Known for doing deep research for his novels, Morrell has written an excellent primer on Cold War spy craft. And while the novel is full of thrilling action, it is the relationship between Chris, Saul, and Elliot that drives the plot. When Chris joins forces with Saul, Elliot must send other assassins to kill them. When the foster brothers realize they have been nothing but tools for Elliot’s private spy game, they go to all extremes to wreak their revenge against the man they consider their father.

Brotherhood of the Rose is another fine piece by the man many consider the father of the modern thriller.

December 11, 2014

Dark Suspense at the Top of the World

Beneath the Arctic ice, an experimental American submarine makes an astonishing discovery—an ice island hiding a long-lost WWII Russian ice station and the remains of its personnel. Within weeks, the U.S. establishes control of the aging Ice Station Grendel and begins unlocking its dark secrets, which include human experimentation and the discovery of an ancient Arctic predator. At first both the U.S. and Russia play nice, but each country has secrets to keep about Grendel, and on the frozen Arctic ice cap, a very heated war is about to erupt.

Beneath the Arctic ice, an experimental American submarine makes an astonishing discovery—an ice island hiding a long-lost WWII Russian ice station and the remains of its personnel. Within weeks, the U.S. establishes control of the aging Ice Station Grendel and begins unlocking its dark secrets, which include human experimentation and the discovery of an ancient Arctic predator. At first both the U.S. and Russia play nice, but each country has secrets to keep about Grendel, and on the frozen Arctic ice cap, a very heated war is about to erupt.Alaskan Fish and Game Warden Matt Pike, his Inuit ex-wife, Jenny – a tribal sheriff – and Jenny's father, are duped into flying to an American Arctic research station near Grendel and become embroiled in the covert warfare. Threatened by soldiers and menaced by Grendel's prehistoric predator, these three plus a handful of submarine crewmen and researchers stranded on the ice station, struggle to survive the predators – both human and animal – and the deadly Arctic weather.

Ice Hunt was one of thriller writer James Rollins' earlier works, written before he started his highly successful Sigma Force series. It is the most suspenseful Rollins book I've read, and the darkest. Don't expect a standard good guys vs. bad guys plot line here, folks. From the beginning, the book is a white-knuckle ride through the Alaskan tundra and the polar ice cap filled with twists and counter-twists. The final few paragraphs are by far the darkest and most blood-curdling, a conclusion worthy of an Edgar Allan Poe story.

November 18, 2014

Review: 'Atlantis' by Bob Mayer

Just after the end of WWII, a Marine aviator named Foreman narrowly

Just after the end of WWII, a Marine aviator named Foreman narrowly avoids being lost in the Bermuda Triangle with the infamous Flight 19.

Decades later, Foreman, now with the CIA, sends a group of Army Green

Berets into a remote part of Cambodia to retrieve equipment from a

crashed spy plane. Only one member of that team, Eric Dane, came back.

Years

later, Dane is once again recruited to return to that area of Cambodia

to rescue the crew of a down aircraft. Dane, after all, is the only

person known to have returned from that part of the country. This time,

Dane knows what to expect. Like the Bermuda Triangle, this portion of

Cambodian is a triangle of mysterious fog where people and aircraft

disappear, a land of strange and deadly monsters the likes of which no

one can imagine. What Dane learns on this second trip to the area is

that it is a threat that once destroyed fabled Atlantis, and now

threatens to destroy all life on Earth.

Thus the plot of Atlantis,

written by best-selling author Bob Mayer (writing under one of his many

pen names), unfolds in a series of actions spanning decades,

culminating with a taut, action-packed climax that will keep the reader

glued to the pages.

Yet, while the plot pulls from many

different legends and is jammed packed with action, it's not a frivolous

book. Mayer's characters are well-drawn—especially Dane and his

relationship with his rescue dog, Chelsey. The plot is well thought out

and, despite its basis in legend, believable. Mayer, a West Point

graduate and retired Green Beret himself, is especially adept at writing

action scenes. The story of Dane's first trip into Cambodia is

particularly realistic.

Atlantis is the first book in

Mayer's popular Atlantis series. (By my count, the prolific Mayer has

something like nine series, a bunch of stand-alone novels, and even more

nonfiction books.) I'm looking forward to reading more of Mayer's

craft.

November 11, 2014

What Does Science Know? There's the Rub

A recent article in Epoch

Times by astrophysicist Geraint Lewis was headlined: "Where’s the

Proof in Science? There Is None." In it, Lewis contests the assumption of

the lay community that scientists "prove" facts. In fact, he says,

they don't.

What scientists do, Lewis explains, is develop models that

explain why something happens in the universe. Some are good models -- as far

as they go. It comes down to "how confident you are in a particular model

being an accurate description of nature, based upon what you know. Think of it

a little like the betting odds on a particular outcome," he writes.

This article struck a cord with me because the plot of my

latest book, Eden: A Sci-Fi Novella,

revolves around the question of just what does science know?

The narrator, Army Captain Adam Cadman, an archaeologist in

civilian life, is confronted with evidence that makes him doubt everything he

thought he knew about the history of mankind. Eventually, Cadman is forced to

concede that scientific knowledge is, in reality, simply a form of general

consensus among researchers— a consensus that frequently falls apart when

confronted with new information.

For instance, we celebrate Christopher Columbus' birthday

because for hundreds of years it was believed he was the first European to

"discover" the Americas. Yet today, we know Norseman Leif Erikson

visited North America 500 years before Columbus.

The fact is, science is limited by what we don't know. And

there is quite a lot we don't know. For instance, how did evidence of

apparently man-made nanotechnology — a relatively new technology —

become encased in rock found in the Ural Mountains that was dated back to an

age before man even walked the earth? How did ancient stone masons at Bolivia's

Puma Punku site carve enormous interlocking stone blocks with a degree of

precision that can't be reproduced with today's technology? Why are there areas

of the earth where vitrification has turned huge areas of earth into glass,

something usually only seen produced by nuclear blasts?

William Shakespeare wrote in Hamlet: "There are more things in heaven and earth,

Horatio/Than are dreamt of in your philosophy." In Eden, Captain Cadman, the scientist, learns how true that is.

November 10, 2014

Pirates, Cannibals, & Marco Polo - And a Believable Plot

How do you create a plot featuring an ancient deadly plague, the

How do you create a plot featuring an ancient deadly plague, the explorer Marco Polo, modern day pirates, and a cruise ship full of

cannibals, and still make it sound plausible? I don’t know, but James

Rollins did just that in The Judas Strain, the fourth in his popular Sigma Force action series.

A

mysterious plague sweeps over an Indonesian tourist island, infecting

hundreds with a flesh-scorching microbe. A cruise ship commandeered by

the World Health Organization and staffed with scientists begins

investigating the epidemic only to be overtaken by modern day pirates

working on behalf of the Guild, a worldwide corporate entity seeking

profit out of every opportunity. Aboard the cruise ship are two members

of Sigma Force, Dr. Lisa Cummings and Monk Kokkalis. While Monk wages a

one-man covert war below decks, Cummings is forced to join forces with

Guild scientists to find a cure to the mysterious malady.

On the

other side of the world, Sigma Force Commander Gray Pierce and his

sometime romantic interest, Guild assassin Seichan, join forces to find a

cure by following long-hidden clues about Marco Polo’s return trip from

Asia, during which he encountered the ancient plague and found a cure.

Eventually, both avenues of investigation meet at the ancient Hindu site

of Cambodia's Angkor Wat in a tense, white-knuckle conclusion.

Where

do the cannibals come in? One of the effects of the infection is to

create an uncontrollable and insatiable hunger in its some of its

victims that drives them to cannibalism.

Let’s face it, at first

glance, these plot elements seem outlandish. But Rollins, a trained

veterinarian, is known for his scientific research and he seamlessly

blends scientific fact with his fictitious plot elements. The only

trouble I have believing Rollins’ Sigma Force stories is the idea that

the U.S. Army’s research agency, DARPA, has a group of

scientists-turned-commandos. That’s only because I support my own

writing endeavors as a researcher for a military institution, and I just

can’t imagine any of my coworkers like that. However, for Rollins’

books I willingly suspend my disbelief. They are just too enjoyable.