Francis Berger's Blog, page 16

November 7, 2024

Even William Lane Craig Acknowledges the Primacy of Intuition Over Philosophy

Readers of this blog are likely aware of the ongoing discussion involving Kristor of the Orthosphere, Dr. Charlton, and me—a discussion Kristor initiated via comments on a post I wrote about the nature of uncreated freedom.

Kristor continuously accuses Dr. Charlton and me of refusing to answer his questions, particularly about arguments like the Principle of Sufficient Reason and the Kalam Cosmological Argument.

Referring to arguments like the Principle of Sufficient Reason or the Kalam Cosmological Argument amounts to little more than an implicit admission on Kristor’s part.

The nature of the admission?

He doesn't give the arguments and answers Dr. Charlton and I provide the attention and consideration they deserve. If he did, he would not have to refer to things like the PSR or the KCA because he could easily infer what our answers mean and how they fit in the context of those things.

Anyway, in the interest of clarity, I will dedicate a few posts to addressing the PSR and the KCA from my perspective and assumptions, starting with the Kalam Cosmological Argument.

Today’s post will be brief.

So, Romantic Christianity argues for the primacy of intuition over external considerations like philosophical arguments. Put another way, Romantic Christianity posits that everyone’s beliefs are grounded in intuition, regardless of whether an individual accepts that as true.

William Lane Craig, the philosopher behind the contemporary Kalam Cosmological Argument, confirms this Romantic Christian “principle”:

I am convinced that it (the KCA) is a good argument.

I just don't regard the argument as the basis for my belief in God. I've been quite candid about that. My belief in God is a properly basic belief grounded in the inner witness of God's Holy Spirit.

Putting the argument aside for the moment, I wholeheartedly agree with Craig. In fact, I’ll take it a step further. I don’t regard any argument as the basis for my belief in God. Like Craig, my belief in God is a properly basic belief grounded in the inner witness of the Holy Spirit (not God’s holy spirit but more on that in another post).

My personal relationship with the Holy Spirit trumps external considerations, including philosophical arguments.

If I were of a flippant nature, I could simply tell Kristor that the KCA has absolutely no bearing whatsoever on my belief in God, leave it there, and feel perfectly justified in doing so.

But I won’t do that.

Conversely, Craig goes on to say that this basic belief in God has no impact on the soundness of the Kalam Cosmological Argument,

Similarly, whatever reason I have personally for believing in God, whether it's the witness of the Holy Spirit or the ontological argument or the teleological argument or divine revelation, or whatever, that just has no relation to the soundness or the worth of the Kalam Cosmological Argument.

The statement above helps shed light on why Kristor is urging me to engage with the KCA—like Craig, he believes it is a sound argument that supports the classical theist omni conceptualization of God, thereby undermining my non-omni conceptualization of God.

Once again, based on the primacy of intuitive belief, I am “within my rights” to tell Kristor to stuff it. He is well within his rights to do the same, but this nullifies any chance at discussion or sharing ideas.

In light of this, I will begin addressing aspects of the KCA in my next post.

Kristor continuously accuses Dr. Charlton and me of refusing to answer his questions, particularly about arguments like the Principle of Sufficient Reason and the Kalam Cosmological Argument.

Referring to arguments like the Principle of Sufficient Reason or the Kalam Cosmological Argument amounts to little more than an implicit admission on Kristor’s part.

The nature of the admission?

He doesn't give the arguments and answers Dr. Charlton and I provide the attention and consideration they deserve. If he did, he would not have to refer to things like the PSR or the KCA because he could easily infer what our answers mean and how they fit in the context of those things.

Anyway, in the interest of clarity, I will dedicate a few posts to addressing the PSR and the KCA from my perspective and assumptions, starting with the Kalam Cosmological Argument.

Today’s post will be brief.

So, Romantic Christianity argues for the primacy of intuition over external considerations like philosophical arguments. Put another way, Romantic Christianity posits that everyone’s beliefs are grounded in intuition, regardless of whether an individual accepts that as true.

William Lane Craig, the philosopher behind the contemporary Kalam Cosmological Argument, confirms this Romantic Christian “principle”:

I am convinced that it (the KCA) is a good argument.

I just don't regard the argument as the basis for my belief in God. I've been quite candid about that. My belief in God is a properly basic belief grounded in the inner witness of God's Holy Spirit.

Putting the argument aside for the moment, I wholeheartedly agree with Craig. In fact, I’ll take it a step further. I don’t regard any argument as the basis for my belief in God. Like Craig, my belief in God is a properly basic belief grounded in the inner witness of the Holy Spirit (not God’s holy spirit but more on that in another post).

My personal relationship with the Holy Spirit trumps external considerations, including philosophical arguments.

If I were of a flippant nature, I could simply tell Kristor that the KCA has absolutely no bearing whatsoever on my belief in God, leave it there, and feel perfectly justified in doing so.

But I won’t do that.

Conversely, Craig goes on to say that this basic belief in God has no impact on the soundness of the Kalam Cosmological Argument,

Similarly, whatever reason I have personally for believing in God, whether it's the witness of the Holy Spirit or the ontological argument or the teleological argument or divine revelation, or whatever, that just has no relation to the soundness or the worth of the Kalam Cosmological Argument.

The statement above helps shed light on why Kristor is urging me to engage with the KCA—like Craig, he believes it is a sound argument that supports the classical theist omni conceptualization of God, thereby undermining my non-omni conceptualization of God.

Once again, based on the primacy of intuitive belief, I am “within my rights” to tell Kristor to stuff it. He is well within his rights to do the same, but this nullifies any chance at discussion or sharing ideas.

In light of this, I will begin addressing aspects of the KCA in my next post.

Published on November 07, 2024 23:36

November 6, 2024

The Philosophy of God Draws One Closer to Philosophy, Not God

The Philosophy of God—classical theism— is proudly grounded in logic.

Logic is respected if it is valid. Most of the arguments for God posited by classical theism are logically valid.

But here’s the thing – a logically valid argument need not be true . An argument is considered valid even when its premises or conclusion is false.

Hence, many arguments comprising the Philosophy of God are logically valid; however, such logical validity is not a confirmation of soundness or truth.

Logical arguments must be valid and sound to be true .

That is, sound arguments must contain true premises and a true conclusion.

And that is indicative of a big problem with the Philosophy of God, especially when it comes to metaphysical assumptions.

What masquerades as truth in the philosophy of God is often little more than logical validity.

If anything, logical validity demonstrates the limits of touting logic and “evidence” as the best and only valid sources of truth.

Yet those who adhere to and insist upon the “validity” of the Philosophy of God as the ultimate mode through which God can be understood and “proved” are quick to reject and dismiss the soundness of intuitive direct-knowing as sound; that is, valid and true.

My lived experience tells me otherwise.

The Philosophy of God draws one closer to philosophy and the logically valid "god of philosophy."

Intuition draws one closer to God.

Logic is respected if it is valid. Most of the arguments for God posited by classical theism are logically valid.

But here’s the thing – a logically valid argument need not be true . An argument is considered valid even when its premises or conclusion is false.

Hence, many arguments comprising the Philosophy of God are logically valid; however, such logical validity is not a confirmation of soundness or truth.

Logical arguments must be valid and sound to be true .

That is, sound arguments must contain true premises and a true conclusion.

And that is indicative of a big problem with the Philosophy of God, especially when it comes to metaphysical assumptions.

What masquerades as truth in the philosophy of God is often little more than logical validity.

If anything, logical validity demonstrates the limits of touting logic and “evidence” as the best and only valid sources of truth.

Yet those who adhere to and insist upon the “validity” of the Philosophy of God as the ultimate mode through which God can be understood and “proved” are quick to reject and dismiss the soundness of intuitive direct-knowing as sound; that is, valid and true.

My lived experience tells me otherwise.

The Philosophy of God draws one closer to philosophy and the logically valid "god of philosophy."

Intuition draws one closer to God.

Published on November 06, 2024 23:52

November 4, 2024

God and the Metaphysics of a Bird With a Broken Wing

This is a retelling of a story I came across.

God creates a bird with a broken wing out of nothing . God tells the bird that it is his child and that he could not have created it in any other way. God calls this good. He then tells the bird that he can fix the broken wing to some degree if the bird obeys and worships him, but that bird will never really be able to fly. Once again, God calls this good. He concludes by saying, “Look at how powerful I am. Look at how good I am. Look how much I love you. Look at how merciful I am. Look at how well I can fix things.”

God finds a bird with a broken wing. God sees this is not good. God makes the bird his child by forming it into a place where he and the bird can work together to fix the broken wing so the bird may be able fly -- fully. God calls this good. God concludes by saying, “Look at how good I am. Look how much I love you. Look at how merciful I am. Look how well I can help fix things if you want me to and work with me.”

Note added: The metaphysical comparison above is incomplete, but it at least gets the ball rolling. Completing the comparison requires an explanation of how and why Jesus' contribution to Creation is necessary for the bird to be able to fly -- fully.

God creates a bird with a broken wing out of nothing . God tells the bird that it is his child and that he could not have created it in any other way. God calls this good. He then tells the bird that he can fix the broken wing to some degree if the bird obeys and worships him, but that bird will never really be able to fly. Once again, God calls this good. He concludes by saying, “Look at how powerful I am. Look at how good I am. Look how much I love you. Look at how merciful I am. Look at how well I can fix things.”

God finds a bird with a broken wing. God sees this is not good. God makes the bird his child by forming it into a place where he and the bird can work together to fix the broken wing so the bird may be able fly -- fully. God calls this good. God concludes by saying, “Look at how good I am. Look how much I love you. Look at how merciful I am. Look how well I can help fix things if you want me to and work with me.”

Note added: The metaphysical comparison above is incomplete, but it at least gets the ball rolling. Completing the comparison requires an explanation of how and why Jesus' contribution to Creation is necessary for the bird to be able to fly -- fully.

Published on November 04, 2024 20:17

November 3, 2024

A Few Short Notes on the Matter of Debunking Conceptualizations of God

Regarding yesterday’s post, I must clarify a few things concerning my scribblings about metaphysics and the nature of God and my discussions with Kristor of the Orthosphere.

I am not motivated to debunk any conceptualization of God, including the God of classical theism. I merely wish to share my views on how I understand God. Those views are, inevitably, often at odds with most classical/traditional/conventional conceptualizations. That does not imply that I regard such conceptualizations with scorn; I simply don’t agree with them.

I am not all that interested in the God of philosophy/theology. Nor do I regard philosophy/theology as the ultimate path to God. I am more inclined to an intuitive approach because I firmly believe in the development of human consciousness and the primacy of freedom.

I am not out to “prove” anything or convince anyone of anything when it comes to metaphysics. My assumptions are my own, and I believe that all people must take full personal responsibility for their assumptions without needing to prove the superiority of said assumptions or dismantle the apparent inferiority of other assumptions. Living honestly by one’s assumptions as best as one can is enough of a challenge...and reward.

Published on November 03, 2024 20:31

You Can't Have It Both Ways in Metaphysics; Unless You Are Kristor, Of Course

In his most recent post in our ongoing discussion, Kristor claims that I have misconstrued the eternal God of classical theism and eternity. I responded with the following comment:

You are confusing my apparent misconstrual with disagreement. I haven’t misinterpreted the eternal God of classical theism as temporal. I disagree with the assumption that the eternal God of classical theism is atemporal. The same applies to my other supposed misinterpretations of time, freedom, and the motive for Creation.

Concerning the post to which Kristor responded, I added:

My post demonstrates how the assumptions and assertions of classical theism become incoherent when the framework for said assumptions is removed. For example, an atemporal God becomes incoherent if one assumes the reality of time, which I do. God as the exclusive first cause becomes incoherent if God is not the exclusive first cause, and so forth.

Kristor, in turn, vehemently protested the approach I had taken:

You can’t talk about before and after in the life of the eternal God of classical theism, and argue from the absurdities that result from so doing, without implicitly presupposing that the eternal God of classical theism is temporal.

And to do that is to suppose that he is not the God of classical theism to begin with, but rather a god like Thor.

If there is before and after in the life of God, so that he could enjoy his perfection before he created (thus raising the question of why he created a world utterly superfluous to his perfect enjoyment) then he is temporal … and he is not the God that the classical theists are talking about, but a straw man and a misdirection and a confusion.

You can’t have it both ways. If you want to debunk the eternal God of classical theism, you’ll have to dispense with all the talk of before and after, and talk about the God of classical theism.

Kristor has raised a crucial point when it comes to discussing metaphysics. So, let’s take a moment and apply the same point to him:

You can’t talk about the non-omni qualities of the God of Romantic Christianity (for lack of a better way of putting it) and argue from the absurdities that result from so doing, without implicitly presupposing the God of Romantic Christianity is omni-everything and atemporal.

And to do that is to suppose that he is not the God of Romantic Christianity to begin with, but rather a god like the omni-everything, absolute God of classical theism.

If the Romantic Christian God is omni, atemporal, and a Trinity, then that God is omni-everything…and that God is not the God that Romantic Christians are talking about, but a straw man and a misdirection and a confusion.

You can’t have it both ways. If you want to debunk the non-omni God of Romantic Christianity, you’ll have to dispense with all the talk of omni, ex nihilo, absolute, and atemporal, and talk about the God of Romantic Christianity.

I bring this up because I want to make Kristor acutely aware of something he seems oblivious to.

He consistently exempts himself from the considerations he insists upon above, particularly when debunking the concept of God I or Dr. Charlton put forward. And when I say consistently, I mean for more than a decade in Bruce’s case.

Kristor expects me to debunk his concept of God solely on his terms while enjoying the privilege of not having to do the same when he debunks my concept of God.

Put another way, if I want to debunk the God of classical theism, I must do it within the parameters of classical theism.

Kristor, on the other hand, reserves the right to debunk the Romantic Christian God within the parameters of, you guessed it, classical theism.

I don’t know about you, but that seems like having it both ways. It also helps illuminate why our discussions about metaphysics never go anywhere.

You can’t have it both ways. Kristor is right, and I wholeheartedly agree with him.

On that note, it would be great to see him apply that criterion to himself more vigorously and rigorously when discussing metaphysics.

You are confusing my apparent misconstrual with disagreement. I haven’t misinterpreted the eternal God of classical theism as temporal. I disagree with the assumption that the eternal God of classical theism is atemporal. The same applies to my other supposed misinterpretations of time, freedom, and the motive for Creation.

Concerning the post to which Kristor responded, I added:

My post demonstrates how the assumptions and assertions of classical theism become incoherent when the framework for said assumptions is removed. For example, an atemporal God becomes incoherent if one assumes the reality of time, which I do. God as the exclusive first cause becomes incoherent if God is not the exclusive first cause, and so forth.

Kristor, in turn, vehemently protested the approach I had taken:

You can’t talk about before and after in the life of the eternal God of classical theism, and argue from the absurdities that result from so doing, without implicitly presupposing that the eternal God of classical theism is temporal.

And to do that is to suppose that he is not the God of classical theism to begin with, but rather a god like Thor.

If there is before and after in the life of God, so that he could enjoy his perfection before he created (thus raising the question of why he created a world utterly superfluous to his perfect enjoyment) then he is temporal … and he is not the God that the classical theists are talking about, but a straw man and a misdirection and a confusion.

You can’t have it both ways. If you want to debunk the eternal God of classical theism, you’ll have to dispense with all the talk of before and after, and talk about the God of classical theism.

Kristor has raised a crucial point when it comes to discussing metaphysics. So, let’s take a moment and apply the same point to him:

You can’t talk about the non-omni qualities of the God of Romantic Christianity (for lack of a better way of putting it) and argue from the absurdities that result from so doing, without implicitly presupposing the God of Romantic Christianity is omni-everything and atemporal.

And to do that is to suppose that he is not the God of Romantic Christianity to begin with, but rather a god like the omni-everything, absolute God of classical theism.

If the Romantic Christian God is omni, atemporal, and a Trinity, then that God is omni-everything…and that God is not the God that Romantic Christians are talking about, but a straw man and a misdirection and a confusion.

You can’t have it both ways. If you want to debunk the non-omni God of Romantic Christianity, you’ll have to dispense with all the talk of omni, ex nihilo, absolute, and atemporal, and talk about the God of Romantic Christianity.

I bring this up because I want to make Kristor acutely aware of something he seems oblivious to.

He consistently exempts himself from the considerations he insists upon above, particularly when debunking the concept of God I or Dr. Charlton put forward. And when I say consistently, I mean for more than a decade in Bruce’s case.

Kristor expects me to debunk his concept of God solely on his terms while enjoying the privilege of not having to do the same when he debunks my concept of God.

Put another way, if I want to debunk the God of classical theism, I must do it within the parameters of classical theism.

Kristor, on the other hand, reserves the right to debunk the Romantic Christian God within the parameters of, you guessed it, classical theism.

I don’t know about you, but that seems like having it both ways. It also helps illuminate why our discussions about metaphysics never go anywhere.

You can’t have it both ways. Kristor is right, and I wholeheartedly agree with him.

On that note, it would be great to see him apply that criterion to himself more vigorously and rigorously when discussing metaphysics.

Published on November 03, 2024 09:16

October 31, 2024

God Needs No Motive For Creation; A Total Non-Answer

In his latest addition to the ongoing discussion, now focused mostly on the matter of Creation, Kristor writes:

In his latest contribution to this discussion, Francis Berger asks why a perfect God would go to the trouble of creating anything less than perfect; less than himself; other than himself. Not having read that contribution before I wrote the paragraph just above, I believe that in it I had answered this question.

The post that Kristor refers to can be found here.

Okay, so let’s see how Kristor answers why a perfect God would go through the trouble of creating anything less than perfect; less than himself; other than himself. Put another way, what is God’s motive for Creation?

Bruce goes on to suggest that “Nicene Christianity perhaps needs to posit a motive for creation – a motive for God creating rather than not.” Well, no.

Well, no?

I guess the first rule of God’s motive for Creation is you don’t talk about God’s motive for Creation.

Okay, but why?

To suppose that God is motivated to do this or that is to mistake him for the sort of being who can lack this or that, as we do; who wants, e.g., to move from a state prior to the fulfillment of his will to another state posterior to that fulfillment, as we can do. It doesn’t work that way for an eternal intelligence. Sub specie aeternitatis, God’s will is always already fulfilled. He lacks nothing; he possesses everything. So, he is not motivated to do anything. He has always already done – is always already doing – all that he would do.

God is an entirely different category of being. He was fulfilled before Creation and remains fulfilled after Creation. Creation did not alter his fulfillment one iota. If that is indeed the case, then my question remains—if God was so fulfilled before Creation, why did he bother with Creation at all?

The answer Kristor provides is basically a non-answer. Our puny hearts and minds can never begin to apprehend the eternal intelligence that is God. Evidence of this lies in the mere fact of supposing God is motivated to do anything at all.

I mean, who are we to suppose anything of God or Creation?

Besides, there is not much point to it because God is not motivated to do anything, at least not as far as our puny hearts and minds can conceive. He’s an eternal intelligence, man! You can’t even begin to understand God’s motives because to do so is to presume God even has motives we could comprehend. He was, is, and always will be and has always done and is already doing all that he would do. For goodness’ sake, isn’t that enough?

In the end, "because" appears to be the only answer Kristor can supply to the question of why God created anything at all.

Forgive me, but this is kindergarten-level argumentation.

To his credit, Kristor does go on to provide some explanation of why God created:

God creates because he is perfect, and the nature of perfection is such that it intends and does all the good that can be done.

If God is perfect and was perfect before Creation, then his intention to do all the good that can be done by creating everything out of nothing makes no sense because such an intention adds nothing good to the perfection that existed before Creation. Nor does it make anything better.

God could have enjoyed his perfection without engaging in Creation. Why didn’t he? Why did God engage in a project to do all the good that can be done knowing full well that such an intention or action makes absolutely no difference at all to his perfection?

His creation is but the outward aspect and effect – in the East, they call these his energies – of his act of simply being himself perfect.

So, Creation is a merely a side effect of the act of perfection? Is that it? Creating non-perfection is somehow a by-product of God being his perfect self?

And because he is perfect, necessary, and eternal, and therefore prior to all times, all ages and worlds, the source, forecondition, alpha and omega thereof, thus timeless, there is no point in the eternal duration of his life at which his will is not already eternally fulfilled, and all creaturely things have not already reached their intended fulfillment and perfection.

Motive for Creation? God is perfect, necessary, and eternally fulfilled—you’re not. ‘Nuff said.

Although I find it a bit presumptuous of Kristor to claim he has provided an answer to a post he had not read, I believe he has provided the only sort of answer he can or will provide concerning the motive/purpose for Creation.

Unfortunately, that sort of answer amounts to little more than a non-answer.

Christianity needs to discover a motive for Creation that extends beyond God and his perfection. Now more than ever.

In his latest contribution to this discussion, Francis Berger asks why a perfect God would go to the trouble of creating anything less than perfect; less than himself; other than himself. Not having read that contribution before I wrote the paragraph just above, I believe that in it I had answered this question.

The post that Kristor refers to can be found here.

Okay, so let’s see how Kristor answers why a perfect God would go through the trouble of creating anything less than perfect; less than himself; other than himself. Put another way, what is God’s motive for Creation?

Bruce goes on to suggest that “Nicene Christianity perhaps needs to posit a motive for creation – a motive for God creating rather than not.” Well, no.

Well, no?

I guess the first rule of God’s motive for Creation is you don’t talk about God’s motive for Creation.

Okay, but why?

To suppose that God is motivated to do this or that is to mistake him for the sort of being who can lack this or that, as we do; who wants, e.g., to move from a state prior to the fulfillment of his will to another state posterior to that fulfillment, as we can do. It doesn’t work that way for an eternal intelligence. Sub specie aeternitatis, God’s will is always already fulfilled. He lacks nothing; he possesses everything. So, he is not motivated to do anything. He has always already done – is always already doing – all that he would do.

God is an entirely different category of being. He was fulfilled before Creation and remains fulfilled after Creation. Creation did not alter his fulfillment one iota. If that is indeed the case, then my question remains—if God was so fulfilled before Creation, why did he bother with Creation at all?

The answer Kristor provides is basically a non-answer. Our puny hearts and minds can never begin to apprehend the eternal intelligence that is God. Evidence of this lies in the mere fact of supposing God is motivated to do anything at all.

I mean, who are we to suppose anything of God or Creation?

Besides, there is not much point to it because God is not motivated to do anything, at least not as far as our puny hearts and minds can conceive. He’s an eternal intelligence, man! You can’t even begin to understand God’s motives because to do so is to presume God even has motives we could comprehend. He was, is, and always will be and has always done and is already doing all that he would do. For goodness’ sake, isn’t that enough?

In the end, "because" appears to be the only answer Kristor can supply to the question of why God created anything at all.

Forgive me, but this is kindergarten-level argumentation.

To his credit, Kristor does go on to provide some explanation of why God created:

God creates because he is perfect, and the nature of perfection is such that it intends and does all the good that can be done.

If God is perfect and was perfect before Creation, then his intention to do all the good that can be done by creating everything out of nothing makes no sense because such an intention adds nothing good to the perfection that existed before Creation. Nor does it make anything better.

God could have enjoyed his perfection without engaging in Creation. Why didn’t he? Why did God engage in a project to do all the good that can be done knowing full well that such an intention or action makes absolutely no difference at all to his perfection?

His creation is but the outward aspect and effect – in the East, they call these his energies – of his act of simply being himself perfect.

So, Creation is a merely a side effect of the act of perfection? Is that it? Creating non-perfection is somehow a by-product of God being his perfect self?

And because he is perfect, necessary, and eternal, and therefore prior to all times, all ages and worlds, the source, forecondition, alpha and omega thereof, thus timeless, there is no point in the eternal duration of his life at which his will is not already eternally fulfilled, and all creaturely things have not already reached their intended fulfillment and perfection.

Motive for Creation? God is perfect, necessary, and eternally fulfilled—you’re not. ‘Nuff said.

Although I find it a bit presumptuous of Kristor to claim he has provided an answer to a post he had not read, I believe he has provided the only sort of answer he can or will provide concerning the motive/purpose for Creation.

Unfortunately, that sort of answer amounts to little more than a non-answer.

Christianity needs to discover a motive for Creation that extends beyond God and his perfection. Now more than ever.

Published on October 31, 2024 20:08

Creation? Why Mess Up Something Perfect?

Fellow blogger Kristor of the Orthosphere has written a post in response to some posts and comments Bruce Charlton and I have shared over the past few weeks concerning the nature of God and freedom and the motive/purpose of Creation. Dr. Charlton has written a response to that post here.

The discussions continue, but breakthroughs remain elusive.

Kristor’s approach to such metaphysical assumptions is firmly anchored in the traditional, classical, conventional assumptions of Nicene Christianity because he finds them intelligible, as opposed to the apparently unintelligible assumptions Bruce or I posit.

There is of course a third option: the classical metaphysics of Nicene Christianity, in which God as uniquely eternal and necessary is the sufficient reason for all being, including his own: not a brute fact, but on the contrary the perfectly intelligent and thus intelligible fact, in whose light all other things are intelligible, at least in principle, so that knowledge is possible; and in which creatures are not eternal, but rather contingent upon God, so that as contingent they can change, act, suffer, move, love, learn, grow, understand and be understood, and so forth.

The chief problem with the intelligible fact of a uniquely eternal and necessary God who is the sufficient reason for all being, including his own, is it focuses almost entirely on the how of Creation while simultaneously and conveniently side-stepping the why of Creation .

Kristor’s position is simple. Creation had to have a cause—more specifically, a first cause. This first cause is God, the creator and source of all being, including his own. Without God, there would be no Creation, yet Creation remains completely unnecessary to God, who has no needs or wants whatsoever and is entirely self-sufficient.

Let’s take a moment and consider God’s position before Creation (not an easy thing to do within the classical/traditional framework, which places God outside of time, but anyway).

Okay, here we go:

The only being who exists before Creation is God. Put another way, nothing exists but God. Time does not exist. Nothing happens; nothing changes. Yet, all is perfect because God is perfect.

Think about that for a moment. Before Creation, God—in his solitude or his Trinity communion—existed in perfection.

Existence was perfect because only a single ideal being existed and nothing else. This single perfect being needs nothing, wants nothing, and experiences nothing but the eternal perfection of his ideal state of self-willed being.

From that state of absolute perfection, God inexplicably, and dare I say, unintelligibly decides to create. Unintelligible because the very act of deciding to embark upon a Creation that would be less than perfect, that its Creator, due to his omni-attributes, knew full well would be imperfect, strikes me as the most unintelligible of all unintelligible facts.

Why would a perfect being willfully decide to create imperfection in his perfection?

Well, decide is the wrong word. He has no choice but to create imperfection because he cannot duplicate his perfection because it is a squared circle.

Still, why mess with a perfect state of being?

God's state of being before Creation implies that he could not have made that state of being any better. Creation has not improved it in any way, shape, or form. That is what perfection means. Thus, the impulse for Creation cannot be grounded in the motivation to "make things better" because such a thing would have been impossible for God to do. I won't go so far as to say God was motivated to make things worse, but . . .

Perhaps he wanted a change. Yet Nicene Christianity posits God as immutable. Perhaps he needed something other than himself or his Trinity. Okay, but Nicene Christianity claims God is impassible and has no needs.

So, God creates, and it isn’t just God alone anymore—there is time, space, matter, and creatures of all sorts, including man, all created from nothing, and all created for good.

However, God decides to create creatures that are capable of evil because free will; however, being omniscient and omnipotent, God knows full well that evil, suffering, and atrocities of all sorts will occur.

I don’t know about anyone else, but I’m still searching for the why of Creation in all of this, starting with the unintelligible fact of why a perfect being who needs nothing would bother creating non-eternal imperfection out of nothing and call it good; non-eternal imperfection that he does not want or need but that is then utterly contingent upon him for its very existence.

Kristor cites knowledge as the overarching motive or impulse behind Creation. That is, an absolute, perfect, unchangeable God decides on Creation so that we, his imperfect, non-eternal, created-from-nothing creatures, can change, act, suffer, move, love, learn, grow, understand, and be understood.

Why a perfect being, perfect in his solitude, would decide upon such a thing remains something of a mystery.

Having said all of that, I agree with Kristor to some degree—the purpose of Creation is rooted in learning, growing, understanding, and loving, but such a purpose must emanate from something intelligible.

An absolute, immutable, impassable, unchangeable, self-sufficient God who existed alone in total perfection before Creation is not and cannot be the source of that intelligibility.

The discussions continue, but breakthroughs remain elusive.

Kristor’s approach to such metaphysical assumptions is firmly anchored in the traditional, classical, conventional assumptions of Nicene Christianity because he finds them intelligible, as opposed to the apparently unintelligible assumptions Bruce or I posit.

There is of course a third option: the classical metaphysics of Nicene Christianity, in which God as uniquely eternal and necessary is the sufficient reason for all being, including his own: not a brute fact, but on the contrary the perfectly intelligent and thus intelligible fact, in whose light all other things are intelligible, at least in principle, so that knowledge is possible; and in which creatures are not eternal, but rather contingent upon God, so that as contingent they can change, act, suffer, move, love, learn, grow, understand and be understood, and so forth.

The chief problem with the intelligible fact of a uniquely eternal and necessary God who is the sufficient reason for all being, including his own, is it focuses almost entirely on the how of Creation while simultaneously and conveniently side-stepping the why of Creation .

Kristor’s position is simple. Creation had to have a cause—more specifically, a first cause. This first cause is God, the creator and source of all being, including his own. Without God, there would be no Creation, yet Creation remains completely unnecessary to God, who has no needs or wants whatsoever and is entirely self-sufficient.

Let’s take a moment and consider God’s position before Creation (not an easy thing to do within the classical/traditional framework, which places God outside of time, but anyway).

Okay, here we go:

The only being who exists before Creation is God. Put another way, nothing exists but God. Time does not exist. Nothing happens; nothing changes. Yet, all is perfect because God is perfect.

Think about that for a moment. Before Creation, God—in his solitude or his Trinity communion—existed in perfection.

Existence was perfect because only a single ideal being existed and nothing else. This single perfect being needs nothing, wants nothing, and experiences nothing but the eternal perfection of his ideal state of self-willed being.

From that state of absolute perfection, God inexplicably, and dare I say, unintelligibly decides to create. Unintelligible because the very act of deciding to embark upon a Creation that would be less than perfect, that its Creator, due to his omni-attributes, knew full well would be imperfect, strikes me as the most unintelligible of all unintelligible facts.

Why would a perfect being willfully decide to create imperfection in his perfection?

Well, decide is the wrong word. He has no choice but to create imperfection because he cannot duplicate his perfection because it is a squared circle.

Still, why mess with a perfect state of being?

God's state of being before Creation implies that he could not have made that state of being any better. Creation has not improved it in any way, shape, or form. That is what perfection means. Thus, the impulse for Creation cannot be grounded in the motivation to "make things better" because such a thing would have been impossible for God to do. I won't go so far as to say God was motivated to make things worse, but . . .

Perhaps he wanted a change. Yet Nicene Christianity posits God as immutable. Perhaps he needed something other than himself or his Trinity. Okay, but Nicene Christianity claims God is impassible and has no needs.

So, God creates, and it isn’t just God alone anymore—there is time, space, matter, and creatures of all sorts, including man, all created from nothing, and all created for good.

However, God decides to create creatures that are capable of evil because free will; however, being omniscient and omnipotent, God knows full well that evil, suffering, and atrocities of all sorts will occur.

I don’t know about anyone else, but I’m still searching for the why of Creation in all of this, starting with the unintelligible fact of why a perfect being who needs nothing would bother creating non-eternal imperfection out of nothing and call it good; non-eternal imperfection that he does not want or need but that is then utterly contingent upon him for its very existence.

Kristor cites knowledge as the overarching motive or impulse behind Creation. That is, an absolute, perfect, unchangeable God decides on Creation so that we, his imperfect, non-eternal, created-from-nothing creatures, can change, act, suffer, move, love, learn, grow, understand, and be understood.

Why a perfect being, perfect in his solitude, would decide upon such a thing remains something of a mystery.

Having said all of that, I agree with Kristor to some degree—the purpose of Creation is rooted in learning, growing, understanding, and loving, but such a purpose must emanate from something intelligible.

An absolute, immutable, impassable, unchangeable, self-sufficient God who existed alone in total perfection before Creation is not and cannot be the source of that intelligibility.

Published on October 31, 2024 12:40

Continuing with the Austrian Theme

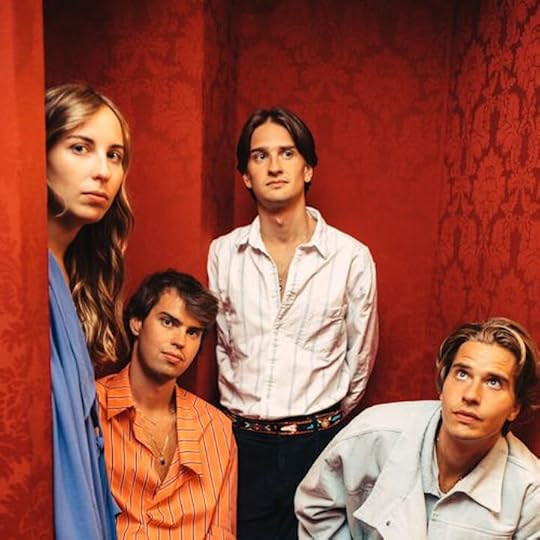

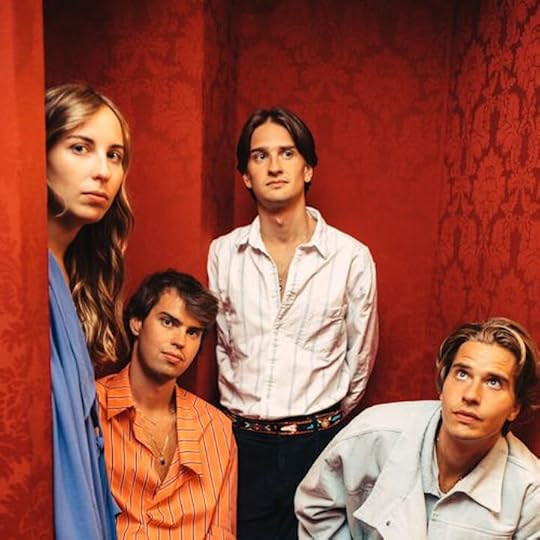

The Wallners, an indie pop/rock band consisting of four siblings from Vienna.  Their sound is reminiscent of groups like Mazzy Star and Cigarettes After Sex. Soothing and easy on the ears. I really like their latest single, Easy.

Their sound is reminiscent of groups like Mazzy Star and Cigarettes After Sex. Soothing and easy on the ears. I really like their latest single, Easy.

Their sound is reminiscent of groups like Mazzy Star and Cigarettes After Sex. Soothing and easy on the ears. I really like their latest single, Easy.

Their sound is reminiscent of groups like Mazzy Star and Cigarettes After Sex. Soothing and easy on the ears. I really like their latest single, Easy.

Published on October 31, 2024 10:59

October 30, 2024

A Delightful Fairy Tale/Fantasy Landscape

While rendering an exterior wall the other day, I began channeling Jack Torrance from Stephen King’s The Shining.

All work no play makes Frankie a dull boy.

So, my wife and I took a short trip to Austria and visited a place called Myra Falls.

Stunning. A landscape befitting the best fairy tales or fantasy novels. I wonder if the Austrians know how fortunate they are to live in such a beautiful country.

Of course, my last name makes me insufferably biased toward undulating, mountainous landscapes (Berg = Deutsch for mountain, so berger means mountainer).

It also doesn’t hurt if said landscapes feature a waterfall cascading through a picturesque forest.

All work no play makes Frankie a dull boy.

So, my wife and I took a short trip to Austria and visited a place called Myra Falls.

Stunning. A landscape befitting the best fairy tales or fantasy novels. I wonder if the Austrians know how fortunate they are to live in such a beautiful country.

Of course, my last name makes me insufferably biased toward undulating, mountainous landscapes (Berg = Deutsch for mountain, so berger means mountainer).

It also doesn’t hurt if said landscapes feature a waterfall cascading through a picturesque forest.

Published on October 30, 2024 11:29

October 29, 2024

God or What? An Approach to the Purpose of Creation

I have been mulling over a recent comment Bruce Charlton left on an earlier post in which I argued that freedom revealed the purpose of Creation.

In his comment, Dr. Charlton refers to two disparate cases concerning the nature of God and Creation—the first being the conventional conceptualization of God or nothing and the unconventional view of God or chaos .

The first case posits God as the ultimate creator of everything and argues that there would be nothing without God. The second case envisions God as a primary creator who shaped and formed Creation from pre-existing “material” (for lack of a better way of putting it) that was chaotic and purposeless.

God or nothing and God or chaos is another angle from which one can view the old creatio ex nihilo versus creatio ex materia debate.

The God or nothing approach insists upon the absolute necessity of God for the simple reason that without him, nothing could exist or be. God not only is—he absolutely must be, for without Him, there would be nothing but a void of nothingness. In other words, I am must be because there is literally nothing on the other side of that thunderous I am.

Every being needs God, but God needs no other beings. No being is utterly necessary but God. This absolute necessity of God relegates everything in existence or being to the state of contingency. Every being in existence is utterly dependent on God in every way imaginable, even when they exercise their God-given freedom to reject God altogether.

However, the God-given free rejection of the Divine Creator does not negate God’s thunderous I am declaration.

The creatures he created from nothing can never return to the nothing from whence they came. They either come to know and worship him or suffer the consequences of their free rejection, the capacity for which God created from nothing.

The God or chaos case envisages God as the primary creator. Without God, there is no Creation, only chaos. God can still say I am, but his necessity takes on an entirely different hue.

The creatures he shaped existed in some form before entering Creation, so he is not necessary for their core pre-existence as beings but crucial to their existence in Creation.

They come to know him and attempt to understand why they are Creation, or they may reject him and, perhaps, choose to return to the chaos from which they emerged.

Since God did not create the freedom driving such a choice, it remains authentically free.

Note added: I'm not sure if returning to pre-existent chaos is possible, but I imagine that God may grant such an option to beings that do not wish to "be" in Creation.

In his comment, Dr. Charlton refers to two disparate cases concerning the nature of God and Creation—the first being the conventional conceptualization of God or nothing and the unconventional view of God or chaos .

The first case posits God as the ultimate creator of everything and argues that there would be nothing without God. The second case envisions God as a primary creator who shaped and formed Creation from pre-existing “material” (for lack of a better way of putting it) that was chaotic and purposeless.

God or nothing and God or chaos is another angle from which one can view the old creatio ex nihilo versus creatio ex materia debate.

The God or nothing approach insists upon the absolute necessity of God for the simple reason that without him, nothing could exist or be. God not only is—he absolutely must be, for without Him, there would be nothing but a void of nothingness. In other words, I am must be because there is literally nothing on the other side of that thunderous I am.

Every being needs God, but God needs no other beings. No being is utterly necessary but God. This absolute necessity of God relegates everything in existence or being to the state of contingency. Every being in existence is utterly dependent on God in every way imaginable, even when they exercise their God-given freedom to reject God altogether.

However, the God-given free rejection of the Divine Creator does not negate God’s thunderous I am declaration.

The creatures he created from nothing can never return to the nothing from whence they came. They either come to know and worship him or suffer the consequences of their free rejection, the capacity for which God created from nothing.

The God or chaos case envisages God as the primary creator. Without God, there is no Creation, only chaos. God can still say I am, but his necessity takes on an entirely different hue.

The creatures he shaped existed in some form before entering Creation, so he is not necessary for their core pre-existence as beings but crucial to their existence in Creation.

They come to know him and attempt to understand why they are Creation, or they may reject him and, perhaps, choose to return to the chaos from which they emerged.

Since God did not create the freedom driving such a choice, it remains authentically free.

Note added: I'm not sure if returning to pre-existent chaos is possible, but I imagine that God may grant such an option to beings that do not wish to "be" in Creation.

Published on October 29, 2024 11:07