Hugh Thomson's Blog, page 3

July 3, 2018

Chicago! Chicago! So good they named it twice…

I have been to many American cities, but never before to Chicago. And I came here for the most agreeable of reasons – to launch a new book, Travelling With Cortes, a handsomely illustrated catalogue of artwork from the Stuart Handler collection which Yale University Press are distributing; I wrote the essays for it.

I have been to many American cities, but never before to Chicago. And I came here for the most agreeable of reasons – to launch a new book, Travelling With Cortes, a handsomely illustrated catalogue of artwork from the Stuart Handler collection which Yale University Press are distributing; I wrote the essays for it.

.

So as my duties are light – a launch dinner at Gibson’s, the Chicago institution where my friends in the city tell me you’d be stupid not to have the steak – there is plenty of time to absorb some unexpected architectural delights: the wild owls and scrollwork on the roof of the central Chicago library; the grill on what is now a Target department store; a US mailbox in silver; a light fitting out of a Terry Gilliam film. The pleasures are endless – compounded by more obvious attractions like one of Alexander Calder’s finest sculptures, a public auditorium by Frank Gehry and the Lakeside Drive.

.

On my final evening, I go to Buddy Guy’s Blues Club, another institution, where, to my surprise, the very funky band are covering, of all things, the Steely Dan songbook – and making it sound fantastic. Although after a dirty dry Martini or two, and several Blue Moons, I am in a receptive mood.

What a great city. I can see why Sinatra once sang: “they have the time, the time of their life / I saw a man – he danced with his wife! / In Chicago, Chicago, my home town…’ In fact, it wasn’t his hometown. But I can see why he might have wanted to be adopted…

.

.

Travelling With Cortes is available on Amazon

the wild owls and scrollwork on the roof of the central Chicago library

public auditorium by Frank Gehry

March 26, 2018

Letter from Lahore

the only person in Lahore wearing a pork pie hat

It’s not every literary festival where you have to check out the foreign office security warnings before you attend. It certainly doesn’t apply to Cheltenham. But then the literary festival which has just taken place in Lahore was no ordinary one.

For a start, there were guards with machine guns at every entrance. Lahore remains a city where foreign nationals have sometimes needed to exercise caution, as have the Pakistani locals.

I’ve been before and thought I knew my way around. So I felt particularly stupid – and alarmed – when I realised the taxi taking me from the airport to the hotel on my arrival was heading in the wrong direction. Moreover the driver only spoke Urdu and brushed aside my questions. Then he pulled into a lay-by and another younger and meaner-looking driver replaced him.

It was still early morning so there were not many people around. My state of paranoia was not helped by having been upgraded on the incoming Emirates flight and celebrating with a couple of vodka martinis which had left my judgement the worse for wear. Was I now about to be abducted before I’d given a single talk (on the new Hachette India edition of Nanda Devi)? I should have stayed in coach.

But as so often with the paranoia travellers feel on first arrivals, it soon evaporated. I had just been part of a regular shift change for sharing a car.

Irvine Welsh was one of many writers attending the festival with me and I decided to keep close in case any situation did ‘go off’, as they say on the hostile environment courses. Surely he’d be able to channel his inner Begbie and be useful in a crisis? Also he was always easy to spot in the crowd as the only person in the whole of Lahore wearing a pork pie hat.

Trainspotting is enormously popular in Pakistan. You can see why from the amphetamine charged way young men ride their motorbikes through the back streets of Lahore. Pakistanis like their literature direct and engaged. The session Irvine gave was packed.

Afterwards, I talked to a polite young man who was in awe of him and spoke in the modulated and careful English of the Lahori middle classes. ‘He is such a very important man. When I read his books, every word is like a bullet that goes through me. The only thing is, I have a problem when Irvine Sahib is speaking. I cannot understand a single word. It is his Scottish accent. It is like trying to understand someone speaking Bengali!’

The festival has come about through the sustained and admirable efforts of Razi Ahmed and his colleagues, who felt that Pakistan desperately needed a literary festival. There is little in the way of a publishing industry here compared to India and the need for freedom of discussion and debate is acute in a society still under the long shadow cast by military involvement in the state.

And Lahore was the obvious city to hold that festival. Kipling’s birthplace and his ‘city of dreadful night’ has become a huge metropolis of eleven million. It is also the literary and artistic hub of the nation, a counterpart to Karachi’s commercial success.

A packed session celebrated the memory of Asma Jehangir, the much loved human-rights lawyer and activist who died just a few weeks ago after a lifetime campaigning – and being imprisoned – for the cause of women and the disadvantaged in Pakistan. Her friend Ahmed Rashid told of how when he wrote his influential book Taliban – which because he wrote it pre 9/11, became essential reading after that particular situation ‘went off’ – the Pakistani government tried to suppress it, given their own close ties to Mullah Omar and friends.

Asma Jehangir came up with an idea. She decided to invent a fictitious literary prize and award it to Ahmed’s Taliban book. ‘Because then the Government will be unable to stop it being distributed.’

Over the two days of the festival, I became acutely aware of the malign effect of the dictatorship of General Zia in the 1980s. Many artists and writers told of how they had been imprisoned or needed to resort to subterfuge to survive those years – and of how freedom of expression is something that has continually to be fought for.

This is a free festival, like the one in Jaipur in India which I attended a few weeks ago, and at both the excitement and energy were palpable. British literary festivals can be decidedly blue-rinse and cautious these days. At Lahore, there were swarms of young students wanting to seize on writers and ideas, and hungry for debate.

As Pakastani novelist Sabyn Javeri put it when she spoke on a panel with Esther Freud, ‘literature helps us listen when we all do too much talking.’

———-

February 4, 2018

At the Jaipur Literary Festival

The Jaipur Literary Festival is an extraordinary occasion. Nothing I had heard about it had quite prepared me for the reality. The numbers are staggering. 350,000 people attend over the five days, so roughly twice the attendance of Glastonbury. Not only are there 400 writers, but there are 400 volunteers just to look after them – which is more than most British literary festivals in small market towns get as an audience.

The Jaipur Literary Festival is an extraordinary occasion. Nothing I had heard about it had quite prepared me for the reality. The numbers are staggering. 350,000 people attend over the five days, so roughly twice the attendance of Glastonbury. Not only are there 400 writers, but there are 400 volunteers just to look after them – which is more than most British literary festivals in small market towns get as an audience.

The energy and intensity is a lot of fun. There is a much younger profile than British literary festivals with plenty of sidebar marquees to dance in. And of course a fair amount of partying. The Ajmer Fort is lit up for a spectacular evening of music at night. While the Writers Ball at the end sees a great deal of glitter and splendour. Can’t believe how much Talisker and Scotch the Indian writers put away.

But the talks were the main events and gathered big audiences. A fascinating one about Bruce Chatwin with William Dalrymple, one of the presiding spirits of the festival, Nicholas Shakespeare as Chatwin’s biographer and Redmond O’Hanlon as Chatwin’s friend.

I was asked to do no less than five sessions over the festival, which is going some by my usual standards and really enjoyed every one.

Here I am talking about my Nanda Devi book which, for reasons I explain has only just been able to be published in India – 30mins to 40 mins into programme, just after William Dalrymple.

And this was a really enjoyable session on the current vogue for nature writing with Adam Nicolson and Alexandra Harris, during which all of us in different ways claimed not to be nature writers anyway, but this didn’t stop us having a very lively discussion.

August 14, 2017

Inca Land

Like everybody else I’ve been reading Sapiens: A Brief History Of Humankind by Yuval Harari- and I was brought up short by one excellent point Harari makes when talking about the first agricultural revolution, the one when we stopped being hunter gatherers:

Like everybody else I’ve been reading Sapiens: A Brief History Of Humankind by Yuval Harari- and I was brought up short by one excellent point Harari makes when talking about the first agricultural revolution, the one when we stopped being hunter gatherers:

“Until the late modern era, more than 90% of humans were peasants who rose each morning to till the land by the sweat of their brows. The extra they produced fed the tiny minority of elites – kings, government officials, soldiers, priests, artists and thinkers – who fill the history books. History is something that very few people have been doing while everyone else was ploughing fields and carrying water buckets.”

Perhaps it’s because I’m in rural Peru, where you can still see hand ploughs used and where the maize is about to be planted. The Sacred Valley, despite the fact that it is so close to both Cusco and Machu Picchu, remains a place made up of smallholdings: campesinos left with tiny plots of less than a hectare since the rather more recent agricultural revolution experienced in Peru in the 1970s when the big Hacienda estates were broken up by a left-wing military government.

Today I saw teams of women going over the ploughed field breaking down the clods of earth with something that looked like a prehistoric mallet, so that it was fine enough to take maize seeds. Groups of men were burning the last of the stubble after the harvest.

Today I saw teams of women going over the ploughed field breaking down the clods of earth with something that looked like a prehistoric mallet, so that it was fine enough to take maize seeds. Groups of men were burning the last of the stubble after the harvest.

.

.

A farmer showed me one of the hand ploughs that are still used in many of the steeper places where it is difficult to use oxen or tractors: an implement of almost biblical severity and the sort of thing Job would have used. The blade was made of hard chonta wood from the Amazon. To hand-plough hard Andean soil is a truly backbreaking job. This will have been how all the land was cultivated before the Spanish brought the yoked plough and the beasts of burden who could pull it.

Harari makes a particularly good point about the anxiety of agriculture – that hunter gatherers just didn’t have to worry in quite the same way about whether the rains would come, let alone crops fail. It is an anxiety that remains today, particularly as climate change affects the Andes dramatically – this has always been an area that lived on the knife edge of el Niño. I thought too of that terrible statistic in rural India where so many farmers have taken their own lives recently.

The Incas had tremendous respect for agricultural land – like their pre-Columbian forebears, they almost always built their settlements on land that was not fertile so as not to waste it. Far more of the Sacred Valley was under cultivation in their day than it is now.

We remain blithely ignorant so much of the time about agriculture, although as populations and temperatures increase we may find it is an issue we can ill afford to be so ill informed about.

June 23, 2017

Publication of One Man And Mule, Hugh’s new book from Penguin Random House

Today sees the publication of One Man And Mule, Hugh’s new book from Penguin Random House.

Today sees the publication of One Man And Mule, Hugh’s new book from Penguin Random House.

Here’s a clip of Hugh being interviewed about One Man and a Mule by BBC radio:

http://www.thewhiterock.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Hugh-Thomson-Outlook-Interview-1.mp3

And to celebrate publication, the first person correctly to answer the following four simple questions can win a free copy:

The name of the mule in One Man And A Mule is:

1 Arthur 2 Jethro 3 Monty 4 Balthazar

In Cochineal Red, our expedition into the Andes took a mule that needed two cases of which following drink so that it was balanced on either side:

Water / Whiskey / Vodka / Pisco (Peruvian brandy)

The name of the mule in my Kindle Single book, Two Men And A Mule, that accompanied the BBC Radio Four series of the same name, when I travelled with Benedict Allen down into the jungle to Espíritu Pampa, the so-called ‘last city of the Incas’, was:

Washington / Clinton / Trump / Benito

Strictly speaking, a mule is the offspring of a

male horse and female donkey

male donkey and female horse

mule stallion and female donkey

mule stallion and female horse

Please note that the following are ineligible to enter this competition: my children, ex-wives, Benedict Allen, anyone else who has accompanied me on expeditions into Peru or across England, supporters of Manchester City FC and employees of Penguin Random House.

April 16, 2017

The Lost City of Z: How to Make Enemies in the Jungle

This is a longer version of articles written for both the London Evening Standard and the Washington Post when The Lost City of Z was released .

“Writer and explorer Hugh Thomson argues that new movie The Lost City of Z gives a totally false impression of its real-life hero.”

With many a jungle drum, this week sees the release and promotion of The Lost City Of Z. Based on the bestselling book of the same name by David Grann, the film proudly proclaims that it is ‘based on an incredible true story’ in which heroic British explorer Percy Fawcett (Charlie Hunnam) ‘journeys to the Amazon and discovers the traces of an ancient, advanced civilization’. And yet it is a quite bizarre distortion of the truth.

With many a jungle drum, this week sees the release and promotion of The Lost City Of Z. Based on the bestselling book of the same name by David Grann, the film proudly proclaims that it is ‘based on an incredible true story’ in which heroic British explorer Percy Fawcett (Charlie Hunnam) ‘journeys to the Amazon and discovers the traces of an ancient, advanced civilization’. And yet it is a quite bizarre distortion of the truth.

The exploration of the Amazon has been one of the epic undertakings of the last few centuries and is still ongoing: uncontacted tribes are still being found in the jungle. It has seen many heroic figures. But Fawcett was not one of them.

March 20, 2017

Two ‘Green Road’ walks in Oxfordshire

Length: 15 miles

Time: 6 hours

Start/finish:

Watlington car park

(OS Explorer 171)

Grade: Moderate

Refuel: The Five Horseshoes

Picnic spot:

Maidensgrove Common

The Thames makes a great sweep down from the crossing at Wallingford and below Whitchurch and Mapledurham to reach Henley. The Chilterns sprawl out from the centre of this crescent in a mess of wooded valleys. The area is relatively close to London – easily reached on the M40 – but offers some surprisingly remote walks.

The Five Horseshoes stands on the edge of a large area of common ground fringed by woods. A 16th-century coaching pub, it has a reputation for excellent, well-priced food – haunch of vension, braised rib of beef – and along with the usual range of alcohol, some exceptional homemade ginger beer for those thinking of the walk back.

Begin in Watlington, perhaps Oxfordshire’s most attractive market town, and follow Hill Road east from the crossroads towards the “White Mark” carved out of chalk on Watlington Hill. Swing past Christmas Common, and then plunge down deep beech woods and along the ancient Hollandridge Lane that comes out at Pishill (locals prefer you pronounce it “Pish – ill”). A steep walk past the little church with its John Piper stained-glass window – the artist lived nearby – leads up to the wide expanse of Maidensgrove Common and the pub.

Return by dropping down the hill to a wooded valley that leads towards Cookley Green and Swyncombe, to meet with the Icknield Way, the prehistoric route that skirts the northern edge of the Chilterns. Whenever I take this broad rolling track, I think of the early 20th century poet Edward Thomas; he described as a “a shining serpent in the wet” when he traced it from Norfolk to Dorset.It’s a good end to the walk and takes you back to Watlington – where, for those who had ginger beer at lunch, a range of reputable hostelries like the Fat Fox await.

Hugh Thomson, author of Wainwright prizewinner The Green Road into the Trees(Preface Publishing). A sequel, One Man and a Mule, is published by Preface in June

Grim’s Dyke, Oxfordshire

Length: 6 miles

Time: 3 hours

Start/finish:

Nuffield

(OS Explorer 171)

Grade: Easy

Refuel: King William IV

Picnic spot: Entrance to

Bixmoor Wood

Grim’s Dyke is a high embankment with a defensive ditch that once ran west and east from the Thames. It was built by the Celts of the iron age in about 300BC for reasons that remain unclear – although the fact that it controls the passage of the Icknield Way may give a clue.

This walk takes you along one of the dyke’s best-preserved stretches, just as it enters the Chilterns. And in April and May walkers will be treated to the sight of magnificent bluebells carpeting the beech woods. A heavy-seeded plant, bluebells travel slowly across the ground: it takes centuries for them to cover such distances.

Starting at Nuffield, take the path along the dyke heading south just west of the church. This is a very ancient track threaded through with white wood anemones and scattered with badger setts. If you look through the trees at the wheat fields to either side, with the young wheat still tight in bud, the stalks shimmer blue under the green of their tops. When viewed from certain angles, they look like water; an effect exaggerated when the wind blows across the fronds and sends a ripple of green-yellow across the underlying blue.

Turn left down the Icknield Way and take a further wander through Wicks wood to reach the King William IV pub in the hamlet of Hailey. On a sunny day, this is a great place to sit outside at a south-facing trestle table and sample beer from the local Brakspear brewery and the cod fried in ale batter.

Suitably refreshed, carry on up the lane towards Homer, a house once lived in by Bruce Chatwin. For even more bluebells there’s a detour into the much photographed Mongewell woods, which lie off to the left as you return to Nuffield. HT

originally published in the Guardian

February 17, 2017

The Marches by Rory Stewart

Thomas de Quincey calculated that Wordsworth walked a staggering 175,000 miles during his lifetime.

He was almost constantly on the move, composing as he went, ‘to which,’ de Quincey added, ‘we are indebted for much of what is most excellent in his writings.’

To put this in context, the circumference of the globe is only 25,000 miles. So Wordsworth could have walked seven times around the planet.

Walking in Wordsworth’s day was the act of a radical; it was to ally yourself, as the young poet wanted to do, with the peasant and the peddler. While more aristocratic artists of the day might take the Grand Tour by coach to Italy, he chose to walk through France during the year of its revolution. To feel connected to the world and people; to make an atlas of his own feelings and spiritual progression.

Rory Stewart follows in that mould. His first book, the acclaimed The Places In Between, saw him walking right across Afghanistan just weeks after the fall of the Taliban, an adventure that was both brave and revelatory. And this was just the beginning of a far longer walk that saw him cross Pakistan. He went on to further adventures in Iraq where he was appointed a governor after the invasion and wrote memorably about the fog of ignorance that pervaded that administration.

Now he has come home, so to speak, to Wordsworth country. In The Marches, he has written an account of a walk across and around England, beginning with a traverse along Hadrian’s Wall, built when a Roman emperor wanted to keep out alien migrants.

The wall took 20,000 men more than a decade to build. It required more stone and labour than the pyramids. As Mr Stewart walks along what remains of the wall – for much of it was later quarried for use elsewhere – he imagines it, ‘stone by stone, stretching fifteen feet high, entire and intact, from coast to coast, running straight up hillsides, down gullies and over cold rivers’.

.

.

However, and with obvious resonance for the wall that may divide America now, he is quick to point out that Hadrian built it more as political symbol than practical barricade. Indeed, archaeologists concur that it was far from being effective, was ‘porous’ and after a while, may have been most useful as a way of employing otherwise idle troops in wall maintenance. It became ‘a zone of cultural exchange and encounter rather than a military barrier’.

The trope of the travel writer who returns to describe his own homeland as if it were another foreign country has become a familiar one – exemplified most recently by Paul Theroux, whose Deep South was a prescient account of the forces beginning to stir there.

So it is natural that Mr Stewart should find echoes on Hadrian’s Wall of his own experiences in Afghanistan and Iraq. Britain sucked in Roman troops. It was considered an exceptionally difficult province to govern. The wall was a radical solution to a grave problem. The Romans struggled to hold Britain with 50,000 men – the equivalent proportionately, says Mr Stewart, of the Allies keeping half a million troops in Afghanistan. ‘The problem was simply that the occupier lacked the knowledge, the legitimacy or the power ever to shape such a society in the way that it wished.’ A judgement he makes equally about the Romans then and Afghanistan and Iraq today.

He remarks too on the way in which the Romans drove the wall across often unsuitable landscape: ‘It looked like the straight lines drawn across flat ground by colonial officers in Africa.’ Not that he is wholly concerned with the past. The area he walks through is now one of the most deprived in Britain, with high unemployment rates, and voted heavily for Brexit.

For much of the walk along Hadrian’s Wall, Mr Stewart is accompanied by his 89-year-old father, an ex-service man who injects a bluff candour to proceedings and is one of the book’s many strengths. With great affection and frankness, Stewart charts both their present and past relationship; the book could almost have been subtitled ‘A Walk Around My Father’. At one point, discussing the wall, the author realises that his father sees it, not as a way of keeping the barbarians out – as most commentators do – but as a way, rather like the Berlin Wall, of keeping the Romans in. He had, after all, been a Cold War intelligence officer.

Stewart’s prose throughout is cool and lucid, with the odd touch of self-deprecating humour. But there is a lot of it. Just as I suspect no reader has ever wished that Wordsworth had written more, so here too even the most loyal of followers may limp in a little footsore by the end of the day.

The problem with The Marches is that having crossed England coast-to-coast along Hadrian’s Wall – more than enough for most travel writers – Mr Stewart then embarks on a series of further walks for some thousand miles. The accompanying map looks like a spider’s web. Much of what he later encounters is fascinating but not particularly germane. Now that he is a local Member of Parliament for the area, he may have felt he had to cover most of his constituency. He certainly doesn’t seem to know how to stop.

This could and should have been a much shorter book. However, perhaps that’s only to be expected from a long distance walker. I’m sure any of Wordsworth’s disciples who complained about having to do ten miles before breakfast were told, briskly, ‘oh for God’s sake. Just keep up!’ And, like Wordsworth, Rory Stewart brings a humane empathy to his encounters with people and landscape. A walk, he believes, is a kind of miracle – which can help him learn, like nothing else, about a nation or himself. He is precisely the sort of companion one would want to travel such a route with: informed, engaged and with a great deal of compassion.

A version of this review first appeared in the Washington Post

December 2, 2016

American Honey

So American Honey is as good as they say it is. I’m suspicious of critically acclaimed indie movies. They can be austere and intellectually respectable – like Cormack McCarthy’s The Road – and not terribly watchable. Particularly when they are almost 3 hours long.

So American Honey is as good as they say it is. I’m suspicious of critically acclaimed indie movies. They can be austere and intellectually respectable – like Cormack McCarthy’s The Road – and not terribly watchable. Particularly when they are almost 3 hours long.

But from the first beguiling frame, this is a masterclass both in direction and cinematography.

It’s shot in an at first brutal 4:3 aspect ratio – like an old school TV film, so almost square – and a reminder of how we usually like to soften out the horizons of a story in widescreen. The effect, together with the strong and harsh colour timing, is to make it look like some of William Eggleston’s cibachrome prints of the Deep South – motel bedrooms (much of the movie is shot in motels or the crew van or lost American suburbs), kids in supermarket checkouts, the shock of going outside onto bright sunlit grass. There is a fabulous scene – which would have been clumsy in less assured hands – when the two lovers chase each other across a suburban lawn and set off the sprinkler against an irradiated sky.

From the moment that newcomer Sasha Lane (the director cast her off the streets) appears on screen as Star, she holds it, often in close-up, along with Shia LaBeouf’s brooding and vulnerable bad boy presence. That is when alpha bad girl Krystal (played by Riley Keough, Elvis’s granddaughter) isn’t putting both of them in their place, a performance made somehow more aggressive because she is usually semi-naked when doing so.

Riley Keough and Shia LaBeouf, her ‘bitch’

The plot is freewheeling in a very good way. But the central premise is that Star is picked up by a van load of kids all trying to make money by hustling and selling magazines, and partying across America.

Where director Andrea Arnold opens it up is with the silences and interstitial spaces of glimpsed life from the van – not just white trailer trash America, but stray birds and dogs and lost children and, in one memorable scene, the oilfields burning at night. There is sadness and hope echoing round Star as she travels across America with a cohort of lost souls. It’s a film about female freedom and loss.

Is it the best film of the 21st century by a woman director? Undoubtedly. And despite the TV ratio, a film that absolutely needs to be seen in a cinema so you can get lost in it yourself.

October 30, 2016

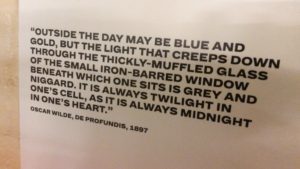

Art in memory of Oscar

A visit to the memorable Artangel installation at Reading Gaol, that most Victorian of prisons with its red-brick cruciform shape and wire-grilled segregation. I filmed ‘Oscar’ for the BBC here when it was still an active prison some 20 years ago; it closed in 2013 and is now scheduled to be demolished. But before it is, Artangel have continued their bold and imaginative curating of art spaces that no one normally reaches by getting artists and writers like Ai Weiwei and Anne Carson to leave messages in the cells that reflect Oscar Wilde’s incarceration here. The finest of these offerings by far comes from Steve McQueen – a sculpture in which a prison bed is swathed in mosquito nets like a cocoon of the imagination.

A visit to the memorable Artangel installation at Reading Gaol, that most Victorian of prisons with its red-brick cruciform shape and wire-grilled segregation. I filmed ‘Oscar’ for the BBC here when it was still an active prison some 20 years ago; it closed in 2013 and is now scheduled to be demolished. But before it is, Artangel have continued their bold and imaginative curating of art spaces that no one normally reaches by getting artists and writers like Ai Weiwei and Anne Carson to leave messages in the cells that reflect Oscar Wilde’s incarceration here. The finest of these offerings by far comes from Steve McQueen – a sculpture in which a prison bed is swathed in mosquito nets like a cocoon of the imagination.

I revisit Oscar’s cell – C.2.2. When I filmed here, it was being used by two inmates so was even more crowded than in Wilde’s day – although he had to endure a harsh regime of physical labour. ‘The most terrible thing about it is not that prison breaks one’s heart – hearts are made to be broken – but that it turns one’s heart to stone,’ as he wrote in De Profundis, his book-length letter from the cell.

I revisit Oscar’s cell – C.2.2. When I filmed here, it was being used by two inmates so was even more crowded than in Wilde’s day – although he had to endure a harsh regime of physical labour. ‘The most terrible thing about it is not that prison breaks one’s heart – hearts are made to be broken – but that it turns one’s heart to stone,’ as he wrote in De Profundis, his book-length letter from the cell.

Wilde’s cell with a rose left as offering

On the day I visit, Patti Smith gives a three hour reading from De Profundis in the prison chapel. She sings a short burst from two songs at the opening and close – first from Nina Simone’s ‘Wild is the Wind’, then from her own ‘Wind’. There are sections of the letter where, as Patti admits (‘What did that last bit mean? I have no idea…’) Wilde can lose the reader as he goes off on wild and lonely tangents. But there are also passages of haunting beauty: ‘I threw the pearl of my soul into a cup of wine.’ It is a fitting tribute and one Patti delivers with passion and empathy.

Steve McQueen’s ‘Weight’, with gold-plated mosquito netting