Hugh Thomson's Blog, page 2

February 2, 2021

The Dig – A triumph

So archaeology can make for a great movie. Don’t be put off by the rather patronising review in the Guardian or some carping criticism about historical accuracy. The Dig, streaming from today as cinemas closed, is an excellent film and worth catching. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if it gets a few BAFTA nominations and deserves to.

So archaeology can make for a great movie. Don’t be put off by the rather patronising review in the Guardian or some carping criticism about historical accuracy. The Dig, streaming from today as cinemas closed, is an excellent film and worth catching. I wouldn’t be at all surprised if it gets a few BAFTA nominations and deserves to.

I did initially approach with suspicion as to whether it was the sort of quiet English period piece which would irritate me for being underscripted and too pleased with itself. Like too much Sunday afternoon television. But this tale of the discovery of the Sutton Hoo Anglo-Saxon longship in a Suffolk field just before the war has a quite unexpected and moving performance by Ralph Fiennes – a career best – playing a deep East Anglian countryman with not just the accent, but the staggered delivery that makes the Suffolk voice so memorable. He apparently had a lot of training in ‘suffolkation’ from local expert Charlie Haylock, and it shows.

And he’s not the only reason to see it. There is some unusually fine ensemble acting, helped by the fact that the Australian director Simon Stone comes out of experimental theatre where he has been much heralded; this is his first film and he manages to get some subtle performances all round, leaving in the silences, helped by a good script from the successful novel by John Preston.

The cinematography also manages to get a great deal out of beauty out of the flat Suffolk landscape that others often pass by. I learned to sail up and down the River Deben not far from the Sutton Hoo site and I have always loved the area (The Suffolk coast: 50 years on from my childhood holidays).

Nicole Kidman was originally slated to play the female lead until almost the beginning of production, and would have been a big box office name (although would the Americans have needed subtitles for Ralph Fiennes?) But she then dropped out, leaving them in the lurch – so, in the space of one frantic weekend, they got in Carey Mulligan, who plays the widowed owner of the Suffolk land on which the longships are found well, probably better than Kidman ever would have. She could easily be up for two nominations, along with her diametrically different Promising Young Woman performance.

Edith Pretty (sitting in the centre on the edge of the trench) observes the dig. Photograph by OGS Crawford, who did a great deal of pioneering aerial photography of archaeology

But the real reason for seeing it is that films about archaeology are intrinsically hard to pull off – digging laboriously in the soil is not very cinematic – and this one really works. The sense of deep time as contrasted against the pressures of the present are brought out. ‘From the first human handprint on a cave wall, we are part of something continuous,” as Fiennes’s character says. There is a very clever play on the way that no one is interested in excavating the barrows when they think they might contain nasty Viking invaders, but as soon as they realise they might be ‘our Anglo-Saxon boys’, it’s game on for the British Museum.

The Guardian complains petulantly that it doesn’t fulfil the usual narrative expectations of girl meets boy, but that’s a strength not a weakness – the laconic style worked beautifully for me and that’s not just because I’m a natural sucker for anything to do with Suffolk, although I am. When I used to spend holidays there as a boy, they always pronounced my name ‘Oo’.

And I’m not too concerned by some of the fictional compression. The actual dig took place over two seasons, in ‘38 and ’39; some artefacts found on one mound were moved to another; Peggy Piggott, who makes the first discovery of a gold object in the burial chamber at the centre of the longship, was less of an archaeological ingenue than the film implies.

Stuart and Peggy Piggott, as portrayed in the film by Ben Chaplin and Lily James

But I do find it oddly disturbing that the marriage between Peggy and Stuart Piggott, portrayed here as fleeting, with them arriving from their honeymoon and parting shortly otherwise, actually lasted 20 years. It had begun some years before Sutton Hoo and only ended in 1956. Nor is there any substantial evidence that Piggott himself, who went on to have one of the most impressive careers in British archaeology, was gay, as the film suggests. This does seem quite a licence to take with people’s real lives, even if it makes for some dramatic tension (Peggy can then be attracted to a young RAF pilot, a fictional character invented for the novel).

That’s a quibble. Far more important is that this shows how novels and indeed films about archaeology can generate considerable dramatic tension and I speak as someone who’s been working on an archaeological novel about Peru for the last 10 years. So yes I have an interest. Let’s hope it wins some Baftas! And – if they can understand Ralph Fiennes’ ‘suffolkation’ – perhaps even an Oscar as well…

———————-

The Dig is streaming on Netflix

There are some interesting photos comparing the actual dig to the film version at this British Museum blog.

John Preston also wrote the book about Jeremy Thorpe that was turned into A Very English Scandal with Hugh Grant.

The Sutton Hoo Ship’s Company have a current project to build a full-size replica of the 90 ft longship, so that it can be sailed.

January 10, 2021

Back to the Joys of Armchair Travel

‘Well that’s you shafted,’ said one friend kindly at the start of the worldwide lockdown. ‘Not a good time to be a travel writer…’

‘Well that’s you shafted,’ said one friend kindly at the start of the worldwide lockdown. ‘Not a good time to be a travel writer…’

Well yes and no. Obviously there’s not much actual travelling possible at the moment. But then the ratio in travel writing between the former and the latter has always been grossly disproportionate – too little time spent travelling and far too much time having to write about it when you get back.

And in my case I only did just get back. I was writing a piece about the sunny beaches and boho resorts of northern Uruguay – one of those gigs which leads to envy and resentment, particularly in March – when they introduced the sudden guillotine on air travel, so we had to slip over the border to Brazil for one of the last flights back to Europe. I was travelling with my girlfriend and for a moment we thought of just staying, as there are worse places to self-isolate than a low rent beach hut in the sun; but while this sounded fun for a while, if the worldwide lockdown continued for months it might have become restrictive and complicated. Wiser counsels prevailed. Which is lucky as otherwise we would still be there.

So I spent last summer and indeed much of last year only travelling as far as the shed at the bottom of my garden. But then that’s where I’ve had to write most of my books in the past anyway. Indeed you could argue that travel writing has always prospered when people couldn’t. One of the reasons why Byron’s long epics about Mediterranean sun, Don Juan and Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, were bestsellers of their day was because the British public were in Napoleonic lockdown and unable to travel there themselves; Byron did it for them. When he wrote of the isles of Greece and how ‘Eternal summer gilds them yet’, he must have had his quarantined British audience salivating.

Vicarious armchair travel has always played a factor in sales. As Paul Fussell described in his survey of the genre, Abroad, there was a huge boom in the genre a hundred years ago during and after the First World War when people were stuck at home and desperate for sun. The travel books and novels of DH Lawrence, Norman Douglas and others supplied much-needed literary vitamin D. The titles alone were calculated to entice: Lawrence’s Mornings in Mexico; Douglas’s South Wind.

Vicarious armchair travel has always played a factor in sales. As Paul Fussell described in his survey of the genre, Abroad, there was a huge boom in the genre a hundred years ago during and after the First World War when people were stuck at home and desperate for sun. The travel books and novels of DH Lawrence, Norman Douglas and others supplied much-needed literary vitamin D. The titles alone were calculated to entice: Lawrence’s Mornings in Mexico; Douglas’s South Wind.

The same thing happened after the Second World War when resources were scarce and another great wave of travel writing took place, so that people could read about going abroad even if they couldn’t afford it. Eric Newby and others fed this appetite, which helped unleash the adventurous travel that started to happen in the 1960s. Newby’s A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush encouraged many a young hippy traveller to take the magic bus to Afghanistan.

In recent years people have got more resistant to travel books on exotic places because of low cost flights and a sense of ‘why bother reading about somewhere when you can so easily just go there?’ So the focus has turned from the ambition of the journey to the quality of the writing, like WG Sebald on the complicated joys of a past walk along the East Anglia coast in The Rings of Saturn: ‘Writing is the only way in which I am able to cope with the memories which overwhelm me so frequently and so unexpectedly.’

And travel writing as a form of memoir means of course that while in lockdown, one can write about travel that happened a long time ago. Patrick Leigh Fermor spent much of a long literary life recreating just one journey: A Time Of Gifts and its sequels came out more than 40 years after his original Balkan travels of the 1930s. He didn’t ever have to leave his delightful retreat in the Greek Peloponnese.

There may even be something that makes ambitious journeys difficult to assimilate too close to the time – that their sensory overload can only best be interpreted years later, when the glitter and noise has fallen away to reveal structure underneath. An earlier book of mine, Tequila Oil: Getting Lost in Mexico, was largely about my own attempts to make sense of a wild road trip in an old American car I had taken through that country 30 years before; most of it was again written back home in a shed.

There may even be something that makes ambitious journeys difficult to assimilate too close to the time – that their sensory overload can only best be interpreted years later, when the glitter and noise has fallen away to reveal structure underneath. An earlier book of mine, Tequila Oil: Getting Lost in Mexico, was largely about my own attempts to make sense of a wild road trip in an old American car I had taken through that country 30 years before; most of it was again written back home in a shed.

Travel writing at its best makes sense of a journey: gives it a narrative arc that it may not have had at the time but that the process of writing can reveal. And travel writing can also inspire us to make journeys that we may never have dreamed of making.

The redoubtable Dervla Murphy had to spend most of her 20s at home in her native Ireland with family responsibilities caring for invalid parents, during which time she read travel books and fantasised about going abroad.

When she was finally able to, in her 30s, she ‘pinged off like a piece of elastic’, as she once put it to me, bought a bike, took off all the gears so there was less to go wrong and started pedalling all the way to India. The resulting book, Full Tilt, is one of the great classics.

I suspect that as lockdown eases, we will all start making journeys again of ambition and purpose, and do them with even greater excitement having been deprived for a while; meanwhile there are plenty of travel books to read in our armchairs to inspire us.

—-

A version of this article was published in the Spectator USA

June 10, 2020

Whatever Happened to Television?

The suggestion in the BBC Plan that BBC4 is to stop making new programmes and become a largely repeats-only channel, possibly only accessible online, is a depressing reminder to viewers of a very long-term trend.

Oh dear. Whatever happened to television? And in particular, the area that BBC4 was particularly supposed to promote – factual and arts television. The channel that was launched with the slogan, “Everybody Needs a Place to Think”. Has the BBC decided that they no longer do?

Or rather, that it is not for them to provide it, when they can concentrate on ‘youth programming’ like BBC3, with the assumption patronising to both young and old that serious factual programming is only for the elderly.

Time was when working in television was to work in one of the most exciting industries around. I certainly found it so. A huge wealth of documentary-making talent showed us how we were living both in this country and abroad – to reveal ‘The World About Us’, as one of its most popular and long-running series proclaimed. Arts documentaries would introduce cutting-edge new artists, and often be so well-made as to be artistic films in their own right: the glory days of Arena, 40 Minutes.

Now it’s largely curatorial. A glance at the schedules shows a woeful lack of ambition, with a staggering amount of repeats. There are hardly any new observational documentaries to show us how other people live. The best we’re likely to get is Come Dine With Me. And, with rare exceptions, the only arts documentaries are obvious coffee-table accompaniments to big shows at the National Gallery, stately and reverential.

For some years now, BBC 4 has settled into a comfortable armchair with carefully stage-managed history lessons by presenters like Andrew Marr, or Lucy Worsley – ‘floating lectern’ programmes as they are known in the business – where the presenter delivers us a lecture with an appropriate and changing backdrop, a bit like a PowerPoint presentation. All fine in their way of course, but very, very safe.

The BBC needs to reset its priorities and its ambition. It’s not enough to do the occasional marquee drama, good as Wolf Hall, War and Peace and others have been. We can get plenty of those on other platforms and nothing the BBC has done recently is as good as the extraordinary Succession, favourite to win all the major awards this year.

What the BBC can do – and perhaps should do to fulfil its public remit – is far more documentary, which it has allowed to wither on the vine.

There is an appetite for knowing how others live. An appetite that has grown as we live in an increasingly compartmentalised world – and in recent weeks when we’ve all been shut in. And an appetite that the BBC is signally failing to feed.

I grew up in a television generation which valued the idea of ‘broadcasting’ in the full sense of the word – reaching a large number of people with material they might not have seen before.

I grew up in a television generation which valued the idea of ‘broadcasting’ in the full sense of the word – reaching a large number of people with material they might not have seen before.

Imagine that television was invented today. That we suddenly created the capacity for large numbers of people to have a communal experience by watching the same programme at the same time all around the country. And not just the Queen addressing the nation – although her success at doing that just the other day was a reminder of how powerful television can be.

Some of the most extraordinary programmes made last year were documentaries: the award-winning For Sama chronicling the Syrian war from the point of view of one family living in Aleppo; Kingmaker’s startling revelations about Imelda Marcos in the Philippines; Netflix’s The Edge Of Democracy about Brazil. My son and I watched Netflix’s eye-opening 13th about black rights in the States last night in the wake of the George Floyd protests. None were made by the BBC.

The BBC needs to regain its ambition when it comes to factual television. That this can be hugely successful has been shown by both Netflix and HBO. It also has the signal advantage of having become far, far cheaper. Technology allows for documentaries to be shot by just a handful of people these days. For a BBC facing budget cuts, it makes financial sense as well to make more documentaries and fewer dramas. There is a wealth of young filmmaking talent out there itching to make documentaries about the world about them and given very little chance by the BBC: you can see some of the wealth of talent at the Sheffield Documentary Festival which opens online this week, and which I helped instigate back in the 1990s at a time when the BBC still ran a lot of documentaries themselves and I was working there.

Nor is it just about the size of the audience. Just as with Radio Four, for the BBC to command a licence fee or a central position in the broadcasting ecosystem, it also needs to command respect. And that means doing things that straightforward commercial channels might baulk at.

Now that Tony Hall is retiring, Tim Davie as incoming Director General needs to reset the BBC’s vision and purpose. Tony Hall has done much to steady the horses after years of damaging management reorganisations and scandals over excessive executive and presenter pay. His replacement will have the opportunity to get on the front foot once again, which the BBC badly needs to do if it is to survive. Otherwise it will reach the point where every one of its channels is just showing repeats.

——

Hugh Thomson was BAFTA-nominated for his BBC series on the history of rock and roll, Dancing in The Street and won the Grierson Award for his series on India with William Dalrymple. He was an instigator and founder member of the Sheffield Documentary Festival.

May 11, 2020

How to Write about a ‘Plague Year’ – 1603 and Thomas Dekker

All those writers buried away in self isolation and trying to describe what we are all experiencing could do worse than turn to Thomas Dekker’s ‘A Wonderful Year’, his account of living through the plague in 1603.

All those writers buried away in self isolation and trying to describe what we are all experiencing could do worse than turn to Thomas Dekker’s ‘A Wonderful Year’, his account of living through the plague in 1603.

Dekker was a young playwright around town in Shakespearean London, very much on the make, and constantly in and out of trouble and prison for debt.

.

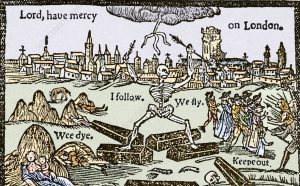

Come the plague in 1603, and all the theatres closed – lockdown was always immediate if deaths from the disease reached just 30 a week – so Dekker turned his hand to pamphleteering to make ends meet.

The challenge was to attract a readership who might not want to be reminded of what they were only just escaping when the pamphlet came out. Dekker’s answer was to try to make much of it as funny as he could: ‘If you read, you may happily laugh; tis my desire you should, because mirth is wholesome against the Plague.’

There is a black humour to his accounts of the lengths to which Londoners would go to ward off the foul-smelling odours thought to bring the disease with them. He describes how people would walk along with rosemary and herbs stuffed up their ears and nostrils, ‘so they looked like pigs being served up for Christmas’; rosemary became the hand sanitiser of its day, with the price Dekker mordantly notes, rising astronomically from ‘12 pence an armful to six shillings a handful’.

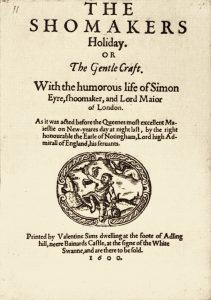

Dekker is best known for The Shoemaker’s Holiday, a boisterous, rowdy comedy of London life, and he manages to get plenty of choice anecdotes in here. The finest is that of the cobbler’s wife, who stricken with all the symptoms of the plague and on her deathbed, calls her husband and her neighbours to her, to confess before she dies that she has had many affairs and treated him wrongly.

Dekker is best known for The Shoemaker’s Holiday, a boisterous, rowdy comedy of London life, and he manages to get plenty of choice anecdotes in here. The finest is that of the cobbler’s wife, who stricken with all the symptoms of the plague and on her deathbed, calls her husband and her neighbours to her, to confess before she dies that she has had many affairs and treated him wrongly.

This news is greeted with the mixture of surprise and respect appropriate to the context, as the neighbours urge the cobbler to be philosophical in the face of his wife’s approaching death and not take his cuckold’s horns too seriously. A high moral tone is taken. At which point, of course, she unexpectedly recovers and then has to face both husband and, far worse, her neighbours’ wives, in the long months afterwards:

‘They came with nails sharpened like cats, and tongues forkedly cut like the stings of adders, first to scratch out her false Cressida’s eyes, and then (which was worse) to worry her to death with scolding.’

But along with the jokes, Dekker gives one of the most vivid eyewitness accounts of what it was like to live through a London plague at that time. This was not one of the great plague years of the 14th century or its last hurrah in 1665. But his description of London during a year in which 1000 Londoners were dying a week (30,000 all told) still makes for sobering reading.

He imagines London as a vast charnel house, hung with lamps and scattered with the bones of the dead:

‘For he that durst (in the dead hour of gloomy midnight) have been so valiant, as to have walked through the still and melancholy streets, what think you should have been his music? Surely the loud groans of raving sick men; the struggling pangs of souls departing. In every house grief striking up an alarm: servants crying out for masters; wives for husbands, parents for children, children for their mothers… And to make this dismal consort more full, round about him bells heavily tolling in one place, and ringing out in another. The dreadfulness of such an hour is unutterable.’

Thomas Dekker

Dekker is humane, funny and at times angry, lashing out at sextons who profited from the fee they received for burying each corpse. Nor does he have much time for doctors, many of whom fled and whose expensive remedies did less good to alleviate the suffering, in Dekker’s opinion, than a good pint of ale and some nutmeg. He also has a profound empathy for London as a city itself: ‘ In this pitiful (or rather pitiless) perplexity stood London, forsaken like a lover, forlorn like a widow, and disarmed of all comfort.’

Is there something we can take too from his antagonistic attitude to death? He had begun this same pamphlet by lambasting Death for killing Elizabeth I, who had died earlier that year in March before the plague arrived (‘On Thursday it was treason to cry “God save King James” and on Friday high treason not to cry so.’)

Now he pictures death as a tyrant storming the city, pitching his tents (‘being nothing but a heap of winding sheets tacked together’) in the suburbs: the plague as ‘Muster-master and Marshall of the field’, with his acolytes being professional mourners, ‘merry’ sextons, hungry coffin-sellers, pall-bearers, and ‘nasty’ gravediggers. ‘Death, like a thief, sets upon men in the highway, dogs them into their own houses, breaks into their bedchambers by night, assaults them by day, and yet no law can take hold of him.’

Meanwhile a great army of Londoners are sent packing by his arrival, ‘so that within a short time, there was not a good horse in Smithfield, nor a coach to be set eyes on’; fleeing to the country where they are met with suspicion and resistance (one country innkeeper barricading himself into his cellar so he didn’t have to serve the dangerous newcomers).

For those that remain the future is grim. Private houses ‘look like St Bartholomew’s hospital’ and he has a vision of 3000 of the dead trooping together to their deaths, ‘husbands, wives & children, being led as ordinarily to one grave, as if they had gone to one bed’.

Dekker compares himself to one of those soldiers at the end of an extraordinary battle, who ‘with a kind of sad delight can rehearse the memorable acts of their friends that lie mangled before them’. As an elegy for a terrible year, his pamphlet deserves more than to be buried at the back of the collected works of a little-known playwright.

An online version of Dekker’s A Wonderful Year’ can be seen at http://www.luminarium.org/renascence-editions/yeare.html

February 20, 2020

Return to Aldeburgh

For those who have been wondering where I’ve been for a longer pause than usual, last year I turned my attention to poetry which has been a constant presence in my writing life, and have been assembling some collections which needed seclusion and concentration, including one of travel poems which for obvious reasons has been a constant thread.

For those who have been wondering where I’ve been for a longer pause than usual, last year I turned my attention to poetry which has been a constant presence in my writing life, and have been assembling some collections which needed seclusion and concentration, including one of travel poems which for obvious reasons has been a constant thread.

As part of that process I returned to the Aldeburgh Poetry Festival which loyal readers with longer memories will remember I attended almost exactly 10 years ago and gave a reading and blogged about.

So very interesting to go back. A certain amount has changed, in that the poetry festival – now called ‘Poetry in Aldeburgh’ as part of its new incarnation after a substantial hiccup a few years ago when the original one went bust – has taken a few years to get up and running again.

the late Tony Hoagland – brave and influential

But some things have remained the same, including the strong presence of American poets like Gregory Pardlo and Josh ‘A Man Being Swallowed By A Fish’ Weiner – and the influence of the late Tony Hoagland, who I first met at Aldeburgh many, many years ago (he was obsessed by finding the best fish and chips), and have always liked; see my review for the Independent of his Unincorporated Persons in the Late Honda Dynasty.

There was a moving and interesting session about him, with contributions from his widow and Josh Weiner and others, talking about ‘his vulnerability about being male’ and the poems that ‘open out and fold back upon themselves’ – some of them political ones that deal with ‘political emotions rather than political ideas’, a useful distinction. Bloodaxe’s anthology, What Narcissism Means For Me, which introduced his work to many British readers, remains one of the most influential poetry publications of the last few decades. I admire Tony’s bravery – not least in the face of cancer in his last poems, but also in his unflinching ability to write about difficult subjects, like the power he suddenly feels over his invalid mother – and the looseness of line he inherited from Frank O’Hara, one of his primary influences.

Michael Schmidt talked of his relationship with many poets over Carcanet’s long existence and I was struck by his unfailing courtesy and patience in the face of often difficult poets like WS Graham or Elizabeth Jennings (what, poets can be difficult and prickly – surely not!)

Gregory Pardlo talked interestingly about the identity politics and poetics which have become so dominant in the States – and the interest in ‘radical empathy’, the idea that we can never know what it’s like for another class/race/gender group but we can at least acknowledge the gap; ‘let’s at least think about the obstacles between us.’

While recognising and respecting the provenance for such ideas, I still can’t help thinking that it’s not who you are, but what you write that matters. That in a way, poetry is a place where identities can be lost rather than found.

Certainly Eliot would have thought so and one of the highlights of the festival was a superb session by Matthew Hollis and Richard Scott (an emphatically gay identity poet and a very fine one) about ‘The Waste Land’. While Pound’s dramatic influence as an editor is well known – slashing the first 80 lines of Canto IV for a start – it was interesting to hear of his hostility to pentameter, or what Pound called ‘tum-pum’ – don’t be too ‘penty’, he would admonish Eliot, and shift a line to tetrameter, to useful effect.

Pearls from the Grit, produced by Naomi Jaffa and written by Dean Parkin

By way of rounding off a fine weekend, I went to see a community theatre production of Pearls from the Grit, produced by Naomi Jaffa who for a long time was the director of the Aldeburgh Poetry Festival and built it into the international presence it became. Written by Dean Parkin, her colleague from those days, the play was a fine evocation of the lost shipping community in Lowestoft, once gifted with more pubs per head than any other place in England before it was swept away for some gasworks. Good to see this being supported by the Arts Council as this was precisely the sort of theatre that taps into strong local emotions and sentiment and was much welcomed by the capacity audience in Halesworth.

March 18, 2019

Salsa Nights in Colombia

The big black guard outside the Topa Tolondra salsa club is built more like a security truck than a man. But the intimidating effect is offset by his spectacles and affability. “Welcome to Cali – salsa capital of the world,” he tells us. And does a few moves.

If there’s any doubt that we’ve arrived at the Holy Grail for all salseros, there’s a giant mural over the dancefloor based on Leonardo’s ‘Last Supper’; but with Oscar D’León, Rubén Blades and Johnny Pacheco taking the role of the disciples clustered round Ismael Rivera (the Puerto Rican who made salsa such a street sound). A young Celia Cruz is the only woman at the feast, resplendent in a red ball gown with a smile that could light up Cuba, if not entire planets.

They look down upon a cavernous dancefloor that is already shaking to a heavy bass and insistent marimbas. It’s Tuesday and only 10 o’clock, so the place is relatively empty. “Come back at the weekend, and it will be so crowded, ‘no bailas – sino que te bailas,’ says one of our guides, Danilo Uribe: ‘you don’t dance – you get danced.’

December 31, 2018

Best of 2018

This has been a wonderful year for me in every way – and here are some of my best things from it:

Music

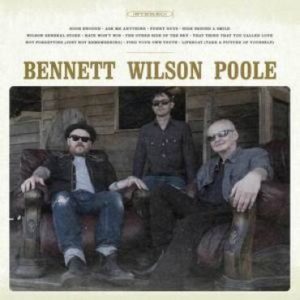

My favourite album didn’t make any of Top 50 lists in the magazines – Bennett Wilson Poole’s eponymous debut was a fabulous slice of Americana with Byrds style guitars – all the more unusual for being produced by three old geezers from Oxford (including Danny Wilson from Danny and the Champions) – great songs and they know how to play live as well, as we saw them at Kings Place in London. Also loved Spiritualized’s new offering And Nothing Hurt (anything Jason Pearce does is always worth a listen, and they are another band who play a blinder live). Talking of live performances, I enjoyed David Byrne’s renaissance, and although there are some filler tracks on his new album, ‘Everybody’s Coming To My House’ is certainly single of the year.

My favourite album didn’t make any of Top 50 lists in the magazines – Bennett Wilson Poole’s eponymous debut was a fabulous slice of Americana with Byrds style guitars – all the more unusual for being produced by three old geezers from Oxford (including Danny Wilson from Danny and the Champions) – great songs and they know how to play live as well, as we saw them at Kings Place in London. Also loved Spiritualized’s new offering And Nothing Hurt (anything Jason Pearce does is always worth a listen, and they are another band who play a blinder live). Talking of live performances, I enjoyed David Byrne’s renaissance, and although there are some filler tracks on his new album, ‘Everybody’s Coming To My House’ is certainly single of the year.

.

Film

‘Emma Get Your Gun’ – The Favourite

The best film of the year only just makes it in time – The Favourite deserves all the accolades currently being showered on it, as it’s funny, inventive, raucous, rude and witty: all the qualities I like in a movie. While Roma was also superb.

Best documentary in another strong year for my favourite genre was the extraordinary Three Identical Strangers, a labour of love and one of the few that had the legs – well three pairs of them – to go to the full feature length.

.

Books

I have personal reasons for liking If Not Critical by the late great Eric Griffiths – see an earlier post – and Priest Turned Therapist Treats Fear of God by Tony Hoagland who also died this year and was to my mind the most wonderful American poet.

I have personal reasons for liking If Not Critical by the late great Eric Griffiths – see an earlier post – and Priest Turned Therapist Treats Fear of God by Tony Hoagland who also died this year and was to my mind the most wonderful American poet.

But mostly I’ve been reading old classics, from Ian Fleming’s muscular Moonraker – so much better than the piss poor film – to Graham Greene’s Quiet American and Robert Pinsky’s tremendous translation of Dante’s Inferno, the best of the considerable pack.

And the very best wishes for 2019 to all my discerning readers.

December 10, 2018

‘Roma’: Mexico City in the 1970s

I like a director with a truly visual imagination – which surprisingly few have – and Alfonso Cuarón qualifies in every way. I loved Gravity for the formality of its visual approach – almost the entire film was shot on the same focal length of lens, apart from the ‘dream sequence’ which was shot on a slightly wider one so the audience was disconcerted without quite knowing why.

But I was still not quite prepared for quite how good his new movie Roma is. Cuarón was his own director of photography, and his black-and-white camerawork is luminous and inspired.

I also have a strong affinity for the place and time – Mexico City in the 1970s where I lived for a while and wrote Tequila Oil: Getting Lost in Mexico. Although of course I remember it in colour.

What impresses me so much is the control and confidence with which Cuarón wields his camera. The film genuinely inhabits the space: mainly a suburban house in Mexico City but also some diverse landscapes and startling juxtapositions.

When I lived in Mexico City the arthouse cinemas showed a lot of Fellini and this reminded me of them – particularly when we visit the wasteland outside Mexico City where, as a human cannonball is shot into a safety net, we follow the film’s heroine in search of the father of her child.

This is not some softshoe indie shuffle, but a film with heart and purpose. At its heart is the Mixteca maid Cleo (played by non-professional newcomer Yalitza Aparicio) who has a quiet and moving resignation in the face of some of the humiliations and tragedies life throws at her. I defy anybody to watch the penultimate scene when the children are swimming in a dangerous ocean and she wades into the waves to try to save them without a lump to the throat.

This is not some softshoe indie shuffle, but a film with heart and purpose. At its heart is the Mixteca maid Cleo (played by non-professional newcomer Yalitza Aparicio) who has a quiet and moving resignation in the face of some of the humiliations and tragedies life throws at her. I defy anybody to watch the penultimate scene when the children are swimming in a dangerous ocean and she wades into the waves to try to save them without a lump to the throat.

It’s a shame that Gabriel García Márquez never allowed anybody to film One Hundred Years of Solitude, as Cuarón would be the perfect director for the project, perhaps as a longer box set.

November 9, 2018

Once In A Lifetime: Eric Griffiths (1953 –2018)

I was one of Eric Griffiths’ first students at Trinity, back in 1980. I remember the excitement at the prospect of a very young new English fellow arriving. He was known to be brilliant and a protégé of Christopher Ricks, with a slightly dark reputation for having a wild side.

I was one of Eric Griffiths’ first students at Trinity, back in 1980. I remember the excitement at the prospect of a very young new English fellow arriving. He was known to be brilliant and a protégé of Christopher Ricks, with a slightly dark reputation for having a wild side.

He certainly enjoyed being a Cambridge maverick. But he did also prove an extraordinary brilliant teacher and this of course is his true legacy.

A sometimes partial one – he could be unfair to those he excluded from his circle and I will always remember the shocked tones with which he once told me a student was doing a thesis on Tolkien – but if he engaged with you, it was a life transforming experience.

For Eric, the study of English literature mattered: in a heuristic way, in a way that constantly questioned one’s own responses and assumptions, in a way that affirmed what it is to be alive and to process mute swirls of consciousness into words on the page.

He had a passionate engagement compared to the bland ministrations of much of the English literature industry and was impatient with the narrowness of their specialist vision – just as, after his conversion to Catholicism, he came to dislike the criticism of metropolitan literary papers with what he saw as their dull modernist orthodoxy and lack of true moral compass. Eric was an academic, but was never an academician. He never played the game of career advancement. He was a true scholar in the sense that all he wanted in life was a room in which to keep his books.

He had a passionate engagement compared to the bland ministrations of much of the English literature industry and was impatient with the narrowness of their specialist vision – just as, after his conversion to Catholicism, he came to dislike the criticism of metropolitan literary papers with what he saw as their dull modernist orthodoxy and lack of true moral compass. Eric was an academic, but was never an academician. He never played the game of career advancement. He was a true scholar in the sense that all he wanted in life was a room in which to keep his books.

The figure that inevitably comes to mind is that of Coleridge, standing in his study at Greta Hall with its big windows, looking out at a vista of mountains and space in which all seemed possible, but nothing ….was quite within reach. The central image in Eric’s biographia literaria would be of him pacing his study over Neville’s Court, listening to Talking Heads, chain-smoking and chain-drinking gin and tonics, engaging with his writers like a shaman summoning up spirit gods from the past with the aid of hallucinogenics (although harder drugs were one of the few vices Eric did not aspire to) but never quite able to wrestle them to the floor.

For Eric was suspicious of theory and suspicious of any critical conclusion that tied up a writer in a neat cardboard box and delivered it in gift wrapping to the reader. To use a theoretical term that he might not have approved of – now that he is no longer here to give a despairing glance at any solecism – he was suspicious of closure.

And this is not closure for Eric, despite the cruel, cruel way he was taken from us.

He lives on in the minds and hearts of those he taught. He was a mesmeric and powerful influence on many. He was a truly Socratic presence. And often a very funny and loyal one.

As we grow older, we collect the voices of those who’ve passed inside our own heads. I will hear him in my mind until the day I die, cajoling, exhorting and above all questioning, which surely is the true role of a critic in a world so complacent in its own certainties.

By great good fortune, Oxford University Press have recently published a volume of his lectures, If Not Critical, retrieved from his computer after his stroke, for which the editor Freya Johnston is to be much commended. My copy arrived on the night that he died after his long illness. They capture perfectly what she describes as the ‘fast, sardonic, protesting and exact’ tone of his public voice. There are apparently many more of these essays. I suspect they will be his true legacy.

By great good fortune, Oxford University Press have recently published a volume of his lectures, If Not Critical, retrieved from his computer after his stroke, for which the editor Freya Johnston is to be much commended. My copy arrived on the night that he died after his long illness. They capture perfectly what she describes as the ‘fast, sardonic, protesting and exact’ tone of his public voice. There are apparently many more of these essays. I suspect they will be his true legacy.

Posted on the day of Eric’s funeral in Cambridge, November 9, 2018

October 16, 2018

Return To Havana

Habaneros using a free wifi spot in the city

Fascinating to be back in the Cuban capital after 20 years. There are still a startling amount of dilapidated buildings along the Malecon; the same old American cars still just about holding together after 60 years of embargo (one taxi driver tells me how hard it is to get the parts); and a few hustlers saying cigars out of doorways – ‘tengo Cohiba!’

But change is slowly coming. Near the free Wi-Fi spots in the city – which are few and far between – you will see groups of Cubans huddled down in the street with the light from tablets, smartphones and laptops reflected back on their faces. Because the Internet has finally arrived.

In Santiago de Cuba – which I’ve also just re-visited – it only came last month; Havana has had it a little longer. But it’s a huge development and with it surely will come accelerated change, just as happened in Eastern Europe in the 1980s when they could view Western TV. The new president of Cuba, Miguel Díaz-Canel, has even issued his very first tweet – to mark the anniversary of independence from Spain back in the 19th century.

Next year sees the 500th anniversary of the foundation of the city that is one of the very oldest colonial creations in the Americas. There will be celebrations, but perhaps that will precipitate more.

There is much talk of the Chinese model – and the Chinese are heavy investors in Cuba at the moment – in which the one-party state retains power but the economy is allowed to grow in more capitalist directions. At the moment the state wage hovers around $30 a month. A private taxi driver can make that in a couple of days. Something has to give. Of course they get excellent health care and education for free, and as long as they are prepared to put up with all living in overcrowded family houses – ‘in Cuba you live and die with your parents’ even when you’re married,’ one young woman tells me, with all the stresses that can cause – free accommodation.

Hanging out with fishermen near Santiago, or in a family park in Cienfuegos, or with the new urban Internet users in Havana, I heard much the same message. But while they are very proud, often justly, of all the achievements of the revolution, and still feel a need to be judiciously quiet about its shortcomings (old habits die hard), change at the moment is only happening very slowly. Too slowly.