Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 491

February 15, 2013

How to deal with sexual violence in South Africa

A month after the BBC wondered if South Africans will ever be shocked by rape, the sadistic rape and murder of the 17 year old coloured working class woman, Anene Booysen, from Bredasdorp, a small town in the Western Cape, provoked nationwide outrage. As last week’s news reports (see here, here and here, for example) and social media traction indicate, South Africans are aware of the urgency with which sexual violence in their country needs to be addressed. Yet the ideas on how to do that, differ widely. Some argue for a reconsideration of the in 1995 abolished death penalty. Others side with President Jacob Zuma, who calls for “the harshest sentences on such crimes, as part of a concerted campaign to end this scourge in our society.” The U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay, herself a South African, commented that “there is a need for very strong signals to be sent to all rapists that sexual violence is absolutely unacceptable and that they will have to face the consequences of their terrible acts. The entrenched culture of sexual violence which prevails in South Africa must end.”

A month after the BBC wondered if South Africans will ever be shocked by rape, the sadistic rape and murder of the 17 year old coloured working class woman, Anene Booysen, from Bredasdorp, a small town in the Western Cape, provoked nationwide outrage. As last week’s news reports (see here, here and here, for example) and social media traction indicate, South Africans are aware of the urgency with which sexual violence in their country needs to be addressed. Yet the ideas on how to do that, differ widely. Some argue for a reconsideration of the in 1995 abolished death penalty. Others side with President Jacob Zuma, who calls for “the harshest sentences on such crimes, as part of a concerted campaign to end this scourge in our society.” The U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights Navi Pillay, herself a South African, commented that “there is a need for very strong signals to be sent to all rapists that sexual violence is absolutely unacceptable and that they will have to face the consequences of their terrible acts. The entrenched culture of sexual violence which prevails in South Africa must end.”

Others highlight the need to end persisting trends of victim blaming and popular misconceptions around the causes of rape: from substance abuse and poverty to curfews and dress codes.

Identifying patriarchal patterns as underlying the sexual violence, Gushwell Brooks, a lawyer and popular talk radio host, argued (in a post on the South African Daily Maverick site) for the deconstruction of violent, authoritative masculinities (dominant ideas about what it means to be a man). In his piece ‘The inefficacy of the Rape Debate’ he contends that

it is not good enough to teach our sons not to rape. What we need to teach our sons quite frankly and honestly is that a woman is not some “thing” placed on this planet just to satisfy whatever desire you have. Muted whispers that girls can do whatever you can, but not really, strips girls and women of the humanity and the accompanying respect they deserve.

Meanwhile, the opposition Democratic Alliance (DA) and the much larger Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu), the latter which is in an alliance with the ruling party, decided to march together against rape, signaling that rape and violence against women is not a party political issue. There’s also widespread enthusiasm for the One Billion Rising Campaign, a global campaign against violence against women that took place yesterday, on Valentine’s Day. The campaign invites “one billion women and those who love them to walk out, DANCE, RISE UP, AND DEMAND an end to this violence.” And earlier this week, I was present as a few hundred people gathered at the St. George Cathedral, a landmark in central Cape Town, in a silent vigil against rape (the photographs illustrating this post is from that vigil).

Meanwhile, the opposition Democratic Alliance (DA) and the much larger Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu), the latter which is in an alliance with the ruling party, decided to march together against rape, signaling that rape and violence against women is not a party political issue. There’s also widespread enthusiasm for the One Billion Rising Campaign, a global campaign against violence against women that took place yesterday, on Valentine’s Day. The campaign invites “one billion women and those who love them to walk out, DANCE, RISE UP, AND DEMAND an end to this violence.” And earlier this week, I was present as a few hundred people gathered at the St. George Cathedral, a landmark in central Cape Town, in a silent vigil against rape (the photographs illustrating this post is from that vigil).

Yet some express skepticism about these signals of resistance. Ranjeni Munasamy, another Daily Maverick columnist and former Zuma spokersperson, observes that “like during the Apartheid past, when violence was a daily feature of life in South Africa, we seem to be again getting accustomed and numb to death and brutality in our society.” South Africa, she argues, “is too accustomed to the daily violation of the weak by those more powerful.” Reuters conceives the overall South African sentiment towards sexual violence as ‘oblivious’.”

Marches, protests and tweets might challenge this ostensible oblivion and numbness. And for those who want to unite in their anger, share the frustration of powerlessness, grief together and send out one and the same message to rapists, survivors, politicians, legislators, mothers and fathers alike that “we want to end rape,” especially marches provide a tremendously powerful platform. However, as a time and occasion-bound gesture, rather than as part of a larger, more pragmatic and sustainable anti-rape campaign, the question ‘what difference will marches and protests make’ is a valid one to ask.

Marches, protests and tweets might challenge this ostensible oblivion and numbness. And for those who want to unite in their anger, share the frustration of powerlessness, grief together and send out one and the same message to rapists, survivors, politicians, legislators, mothers and fathers alike that “we want to end rape,” especially marches provide a tremendously powerful platform. However, as a time and occasion-bound gesture, rather than as part of a larger, more pragmatic and sustainable anti-rape campaign, the question ‘what difference will marches and protests make’ is a valid one to ask.

One Billion Rising has come in for some criticism. On the weekly newspaper Mail and Guardian’s Thoughtleader blog, Talia Meer takes a critical look at One Billion Rising’s approach towards sexual violence and wonders:

… can we just dance it all away? Or dance it away just a little? We certainly cannot “dance until the violence stops”! She warns that “Like the contentious Slut Walk, One Billion Rising runs the risk of sensationalising gender-based violence activism. It abstracts the on-going struggle of GBV organisations, individuals and survivors, to a brief, quirky and enjoyable moment. A walk in your knickers or a dance.

The legal academic and blogger, Pierre De Vos, acknowledges the good intentions that drive the protestors, but he worries that “the expression of outrage is a distancing device and ultimately self-serving. I fear the smell of self-congratulatory self-indulgence clinging to the enterprise. Expressions of outrage position us in opposition to the evil that we rush to condemn.”

For many marchers, their sense of responsibility and agency to rise up against rape might indeed vanish when the march is over and they go home. Only to be fired up once again when the next rape, brutal enough to be deemed newsworthy, confronts our conscience. Yet meanwhile, ‘ordinary rapes’ (at an expected rate of at least 154 a day) will continue to go on. And so will our lives. Is it indeed oblivion and violence-fatigue that is guiding this ostensibly short-term character of our responses? Or is the psychological self-distancing mechanism, as envisioned by De Vos, to blame? I wouldn’t know. I can only observe, imagine and wonder. What I observed is a sense of powerlessness. And what I imagine is that for many South Africans, overturning patriarchy, reconstructing dominant masculinities and enforcing harsher sentences simply feels beyond their sphere of influence. Which got me wondering; next to tweeting, marching and investing in both daughters and sons, what else CAN we do?

For many marchers, their sense of responsibility and agency to rise up against rape might indeed vanish when the march is over and they go home. Only to be fired up once again when the next rape, brutal enough to be deemed newsworthy, confronts our conscience. Yet meanwhile, ‘ordinary rapes’ (at an expected rate of at least 154 a day) will continue to go on. And so will our lives. Is it indeed oblivion and violence-fatigue that is guiding this ostensibly short-term character of our responses? Or is the psychological self-distancing mechanism, as envisioned by De Vos, to blame? I wouldn’t know. I can only observe, imagine and wonder. What I observed is a sense of powerlessness. And what I imagine is that for many South Africans, overturning patriarchy, reconstructing dominant masculinities and enforcing harsher sentences simply feels beyond their sphere of influence. Which got me wondering; next to tweeting, marching and investing in both daughters and sons, what else CAN we do?

It’s not like there aren’t organizations and groups doing real, hard work around rape in South Africa. The website Women, In and Beyond the Global provides an answer on how to channel and sustain outrage in a constructive and pragmatic manner; quantify your outrage and support those organizations that have been working to end rape and empower survivors for years. Both Rape Crisis Cape Town and the Saartjie Baartman Center for Women and Children are such organizations. They empower, counsel and support rape survivors and strive towards law reform through advocacy, training and awareness campaigns.

Despite the fact that sexual violence has been a well-known reality for South African women for years, both these NGOs are facing funding withdrawals, which has led to a continued threat of closure.

For those who feel outraged and powerless and are in a position to either donate money or dedicate some time, become a monthly donator or pay a once off donation to Rape Crisis via their website and support the Saartjie Baartman Center for Women and Girls here. Another way to exercise agency is signing the petition by Avaaz.org. This online petition seeks to tackle the problem by calling on South Africans to sign an online petition, which should pressure the government to heavily invest in research on rape and in a public education campaign.

* The photographs are the work of Zubair Sayed, a Cape Town, South Africa-based communication and campaign specialist who dabbles in photography. You can reach him at zubair.say@gmail.com.

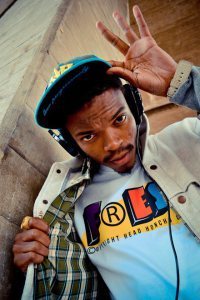

Here’s what some South African artists make of the country’s politics

To get the pulse of a country journalists usually go for political elites or the “man on the street.” Rarely do they ask artists what they think about politics (and we’re not talking when a question about politics is thrown in at the end of an interview to promote an album, new music, a film or a performance). So I decided to ask a couple of South Africa-based artists about their feelings on the socio-political climate in their country. The context: with Mangaung firmly behind the ANC, South Africa still finds itself having to contend with pressing issues such as the president’s multi-million rand mansion, recent revelations about Helen Zille and Co.’s dealings with the Guptas, and as recently as yesterday, a world-renowned athlete causing an international media stir for a murder he may or may have not intended to commit. The creative community in South Africa has been mostly silent on these socially-pressing matters. While there have been pockets of dissenting voices, the overall outcry over something like Marikana, for instance, has been nothing short of de-spiriting. What do artists make of all this? Here’s a few responses:

Jimmy Flexx (rapper): Everyday is a struggle. I’m not disillusioned about who I am or where I am. I’m very aware of where I want to be, what I want to achieve, and I know where I am currently. I know where I come from. We stick to our guns. I can’t be obnoxious; when we have our traditional gatherings, I don’t want to be middle-class. I don’t know how other artists do that shit, where they can present something that is not really true. I know, every black motherfucker in this country has poor family, no matter how successful you and your immediate family might be. But, when the family comes together, there’s still that drunk uncle, there’s still that cousin who causes trouble. You must talk to him, talk to your cousin. That is where we come from, that is South Africa for me. The realest music in South Africa was done during the times of struggle, and even the artists were then producing their best work, I feel. They were overseas longing for home, longing for family; all of those struggles. Out of that came songs that, when you listen to them even today you’re like ‘what a great job!’ Think of all the issues that we have in this country; but somehow the youth are still having fun, still celebrating. It’s like an outlet, ignorance is bliss they say. No one wants this shit, no one wants to be aware of what’s going on. But we want to celebrate and party. It’s almost like we’re running away from something that we don’t really want to deal with.

Jimmy Flexx (rapper): Everyday is a struggle. I’m not disillusioned about who I am or where I am. I’m very aware of where I want to be, what I want to achieve, and I know where I am currently. I know where I come from. We stick to our guns. I can’t be obnoxious; when we have our traditional gatherings, I don’t want to be middle-class. I don’t know how other artists do that shit, where they can present something that is not really true. I know, every black motherfucker in this country has poor family, no matter how successful you and your immediate family might be. But, when the family comes together, there’s still that drunk uncle, there’s still that cousin who causes trouble. You must talk to him, talk to your cousin. That is where we come from, that is South Africa for me. The realest music in South Africa was done during the times of struggle, and even the artists were then producing their best work, I feel. They were overseas longing for home, longing for family; all of those struggles. Out of that came songs that, when you listen to them even today you’re like ‘what a great job!’ Think of all the issues that we have in this country; but somehow the youth are still having fun, still celebrating. It’s like an outlet, ignorance is bliss they say. No one wants this shit, no one wants to be aware of what’s going on. But we want to celebrate and party. It’s almost like we’re running away from something that we don’t really want to deal with.

Siya Mthembu (Vocalist for The Brother Moves On): I don’t need you to care about all my issues, I just need you to respect me as a human being. As in, I explain my issue, take the time to listen, so you can understand. But that space is not given, I’m not even allowed to talk to you anymore! I come from a culture that says ‘let’s talk!’ We’re not in a good space, we know we’re not in a good space, we know we’re unhealthy. But to scream and shout about it from the rooftoops … I want to play at the Voortrekker Monument. I wanna go there. If I’m going to be booed off stage, if something’s going to be thrown at me, let’s have it! We’ve gone to Hoedspruit [a hotbed of white rightwing politics--ed] where when we got off the stage, the emcee was like ‘Hoedspruit, Hoedspruit we must change man!’ When are we gonna have the human impact? Everyone’s in the high theory of it, the amazing discourse of academy. The man on the streets understands these issues as well, how about you speak in his language? You’re not engaging him, you don’t wanna speak in his language! You want him to say it in your language, you don’t him to be political; you want him to be apolitical!

Siya Mthembu (Vocalist for The Brother Moves On): I don’t need you to care about all my issues, I just need you to respect me as a human being. As in, I explain my issue, take the time to listen, so you can understand. But that space is not given, I’m not even allowed to talk to you anymore! I come from a culture that says ‘let’s talk!’ We’re not in a good space, we know we’re not in a good space, we know we’re unhealthy. But to scream and shout about it from the rooftoops … I want to play at the Voortrekker Monument. I wanna go there. If I’m going to be booed off stage, if something’s going to be thrown at me, let’s have it! We’ve gone to Hoedspruit [a hotbed of white rightwing politics--ed] where when we got off the stage, the emcee was like ‘Hoedspruit, Hoedspruit we must change man!’ When are we gonna have the human impact? Everyone’s in the high theory of it, the amazing discourse of academy. The man on the streets understands these issues as well, how about you speak in his language? You’re not engaging him, you don’t wanna speak in his language! You want him to say it in your language, you don’t him to be political; you want him to be apolitical!

Dplanet (Producer/label owner): I am really worried about the future of South Africa. I honestly think that since 1994, it’s become so de-politicised. Everyone’s about making their money, especially in Jo’burg, it’s actually ridiculous! And I guess that’s what happens, it’s a younger generation. They don’t wanna hear about bad times, they want to party and just forget about shit. That’s one side of it, but the downside is that your rights are slowly being eroded away. I’m still shocked that there’s not more of a massive outcry, that the police could shoot forty-eight people, or whatever it was, who were protesting because they were treated like shit by a multi-national, multi-billion dollar corporation. It’s always been the case, we’ve got a one-party system here. There is no strong opposition. I think even if you’ve got good intentions, the ANC has gone from a revolutionary party to just a regular political party. I don’t really know what’s in the hearts of those people, what’s in Zuma’s heart. But the way they’re acting says it all. How could anybody take 200 million Rand of the taxpayer’s money and spend it on their personal house? That’s the result of having a weak democracy where there’s one party in power. I hear it all the time; black people say to me ‘well, at least it’s our own people robbing us.’ No man, that’s not good enough! You deserve better than that, we all deserve better than that. Being robbed by a white person or a black person, you’re still robbed at the end of the day.

Dplanet (Producer/label owner): I am really worried about the future of South Africa. I honestly think that since 1994, it’s become so de-politicised. Everyone’s about making their money, especially in Jo’burg, it’s actually ridiculous! And I guess that’s what happens, it’s a younger generation. They don’t wanna hear about bad times, they want to party and just forget about shit. That’s one side of it, but the downside is that your rights are slowly being eroded away. I’m still shocked that there’s not more of a massive outcry, that the police could shoot forty-eight people, or whatever it was, who were protesting because they were treated like shit by a multi-national, multi-billion dollar corporation. It’s always been the case, we’ve got a one-party system here. There is no strong opposition. I think even if you’ve got good intentions, the ANC has gone from a revolutionary party to just a regular political party. I don’t really know what’s in the hearts of those people, what’s in Zuma’s heart. But the way they’re acting says it all. How could anybody take 200 million Rand of the taxpayer’s money and spend it on their personal house? That’s the result of having a weak democracy where there’s one party in power. I hear it all the time; black people say to me ‘well, at least it’s our own people robbing us.’ No man, that’s not good enough! You deserve better than that, we all deserve better than that. Being robbed by a white person or a black person, you’re still robbed at the end of the day.

Professor Pitika Ntuli (academic, sculptor, poet): I think all these forms of power constructions, constricting people, they undergo change, they’ve become more sophisticated. Banishment was very brutal, where they literally lifted you up and took you away. But today they don’t have to, they’ve got to move the locus of economic power to centres, and then you control those centres. It started, for instance, in the townships. Do you know that until after independence, when you entered into any township, there was only one gate you were going in and one gate you were going out? It was constructed as a military complex. So as to be easily controlled. They were, in a sense, banishment areas. You wouldn’t walk in town by night. After 9 o’clock, if you were a black person, you were not allowed to. The way you look at it today, the rising poverty, the gap between the rich and the poor is actually increasing, and the poor are being the ones actually isolated – banished from getting their slice of the national cake. People living in those informal settlements, they are dragged away from the rural areas. And those rural areas are actually being sold out … I think people are very angry, they’re still angry. It’s like this, your president says: ‘uyambambezela, leth’u mshini wam’. And then he builds a bunker. And then he militarises the police into generals, brigadiers … this is a language not of civil society. A civil war has been declared, but you’re not even aware.

Professor Pitika Ntuli (academic, sculptor, poet): I think all these forms of power constructions, constricting people, they undergo change, they’ve become more sophisticated. Banishment was very brutal, where they literally lifted you up and took you away. But today they don’t have to, they’ve got to move the locus of economic power to centres, and then you control those centres. It started, for instance, in the townships. Do you know that until after independence, when you entered into any township, there was only one gate you were going in and one gate you were going out? It was constructed as a military complex. So as to be easily controlled. They were, in a sense, banishment areas. You wouldn’t walk in town by night. After 9 o’clock, if you were a black person, you were not allowed to. The way you look at it today, the rising poverty, the gap between the rich and the poor is actually increasing, and the poor are being the ones actually isolated – banished from getting their slice of the national cake. People living in those informal settlements, they are dragged away from the rural areas. And those rural areas are actually being sold out … I think people are very angry, they’re still angry. It’s like this, your president says: ‘uyambambezela, leth’u mshini wam’. And then he builds a bunker. And then he militarises the police into generals, brigadiers … this is a language not of civil society. A civil war has been declared, but you’re not even aware.

* BTW, we might make this a regular feature.

February 14, 2013

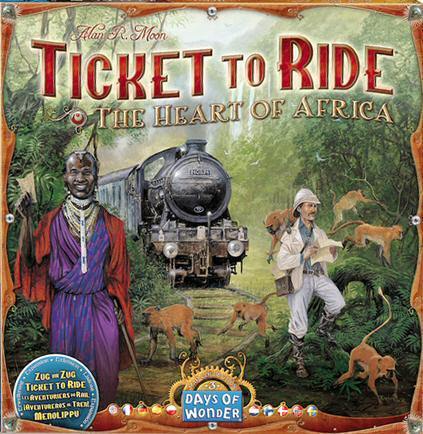

Africa is a Board Game

While shopping for Christmas presents this past December in a local gaming store, this little number caught my eye. Ticket to Ride: The Heart of Africa is a variation of a popular board game in which players compete to build railways connecting major cities. The original version of the game uses a map of the U.S. There are also versions for Europe, Germany, and Scandinavia. As board games go, Ticket to Ride is well-designed and wildly addictive. (I should know: I made the mistake of downloading the iPad version to “research” this blog post.)

The artwork for all versions of the game is meant to evoke nostalgia for the early 1900s “golden era” of railway travel. In the U.S. version, for instance, various characters are depicted doffing top hats or twirling parasols, and the playing cards feature images of steam locomotives. Lately, Days of Wonder, the game’s manufacturer, has branched out from Europe and North America, releasing game maps for Asia, India, and Africa. The historical setting of the game becomes a bit more problematic in these contexts.

The cover art for Ticket to Ride: The Heart of Africa depicts an explorer in a pith helmet looking at a map whilst being tormented by a troop of monkeys, with a smiling “native” African in “traditional” dress in the foreground. The accompanying rules book (available for your perusal on the Days of Wonder website), continues to lay on the colonial nostalgia: the game, it tells us, is “set in the vast wilderness of Africa at the height of its exploration by intrepid explorers, missionaries and adventurers.” (Exploration by explorers? Really?) Players are invited to “build routes through some of the continent’s most remote and desolate locales.” The game’s title too, with its obvious indebtedness to Joseph Conrad, is meant to evoke the frisson of colonial ventures into the “dark continent.” (Oddly, the African version of Ticket to Ride is the only one with such a subtitle, although the website for the Asia version does invite players to “venture into the forbidden eastern lands of…Legendary Asia.”)

There’s nothing inherently wrong with setting a board game—or a book, or a film—in Africa during the colonial era. I wouldn’t even argue that the game needs to be made more “realistic.” (Say with the addition of cards reading, “Your railway’s proposed route passes through a large village. Do you wish to miss a turn, or simply bulldoze the obstructing houses and kill those who seek to oppose you?” etc.)

It’s one thing, however, to use colonial-era Africa as a backdrop without directly critiquing colonialism (or to use early-1900s North America without addressing conflicts with First Nations and forced migrant labor, for that matter); and it’s another thing to play on stereotypes and romanticism in order to increase the game’s popularity. There is no question that players of Ticket to Ride Africa are cast in the role of colonists, competing with one another to make the largest imprint on the continent’s “vast wilderness.” The fact that this seems to be a selling point reveals something quite disturbing about the Euro-North American psyche.

Lesotho Media and the Growing Intimidation of Chinese Shop Owners

Earlier this week on my regular social media run, I came across this status update on Facebook: “I wonder if makin [sic] death threats on these asian traders will really address anythn [sic], the commotion on radio is just misleading everyone.” Immediately, a story started forming tentacles in front of my eyes; “sinophobes!”, I exclaimed to myself. In December 2012, the government of Lesotho had, through its ministry of Trade and Industry, shut down shops in and around Maseru. Earlier raids seem to have been conducted, but Chinese-owned shops have been known to sell less-than-appealing food to their Basotho customers for years, most of which are not well-to-do and hence cannot afford to buy groceries from elsewhere.

Earlier this week on my regular social media run, I came across this status update on Facebook: “I wonder if makin [sic] death threats on these asian traders will really address anythn [sic], the commotion on radio is just misleading everyone.” Immediately, a story started forming tentacles in front of my eyes; “sinophobes!”, I exclaimed to myself. In December 2012, the government of Lesotho had, through its ministry of Trade and Industry, shut down shops in and around Maseru. Earlier raids seem to have been conducted, but Chinese-owned shops have been known to sell less-than-appealing food to their Basotho customers for years, most of which are not well-to-do and hence cannot afford to buy groceries from elsewhere.

After contacting my man on the ground, Sechaba Keketsi, my mind got made up beyond reasonable doubt that Basotho’s inherent despise towards Chinese people was at play. This sentiment was advanced by Puseletso Ramokhethi, a motor-mouth radio host whose utterances on her breakfast show on PC FM are questionable at best. For instance, she uttered the following on her show: “re tla bua ka libolu tsa machina ho fihlela motho e mong boholong a utloa bohloko. Ke kene ra thola” — which translates to “we’ll speak about the Chinese’s rotten food until someone in authority takes note.” The overall tone of the utterance could easily pass for hate speech.

Lesotho’s media industry is not well-regulated, especially the airwaves with their quirky and questionable personalities such as Moafrika FM’s Ratabane “Candy” Ramainoane, a cult personality who employs a range of tools, from semi-traditionalist rhetoric to outright Christian fundamentalist utterances to spread his propaganda. His facebook profile describes him as “The Prophet, Apostle and Community Leader inspired by the Word of God.” “They need to be shown the exit door as early as yesterday,” he has said of Chinese traders whom he alleges are “poisining [sic] the entire Basotho nation with food and bevarages.”

The Lesotho Times reported the following from a press conference by the principal secretary in the Ministry of Trade, Moahloli Mphaka:

Mphaka said [...] the crackdown against supermarkets selling expired foodstuffs is not aimed at Chinese-owned businesses.

His comments come in the wake of a country-wide campaign [...] to stop businesses from selling expired products including foodstuffs.

China’s ambassador to Lesotho, Hu Dingxian, had expressed concerns that the campaign might turn into xenophobic attacks against Chinese nationals … Hu added that if Basotho attack the Chinese, relations between the two countries might be affected.

One of the shops that was mentioned is a Chinese-run meat outlet, Sky Country, which was alleged to be selling rotten meat … Basotho have in the past accused the government of turning a blind eye to Chinese businessmen selling rotten food.

The operation to inspect all supermarkets and close those that do not abide by the law is being driven by the Trade Ministry, Health Ministry, Department of Immigration, the police and the Maseru City Council … Maseru district police commander, Senior Superintendent Mofokeng Kolo, said they have so far taken three cases to court. He said the cases could not proceed “because we did not have a Chinese interpreter … We charged another Chinese businessman for sleeping at his business premises but we did not have evidence that we could present before the courts of law.”

It is interesting to note the mild intimidation coming from the Chinese embassy’s side. Also, there is growing concern about how quick the police deal with these cases, with various sectors alleging that junior police officers get transferred to remote outposts whenever they attempt to investigate any cases directly involving Chinese shop owners.

* Additional thoughts by Sechaba Keketsi. For a bit of background reading on the Chinese in Lesotho, see here and here.

The politics of selling African art mostly collected during colonial era to private collectors (in the Netherlands)

Guest Post by Chandra Frank*

Guest Post by Chandra Frank*

The proposed sale of the Africa Collection at The World Museum in Rotterdam, the Netherlands has sparked some interesting debates in Dutch media lately. Unfortunately some important questions and issues around this sale are not being discussed. Since the Dutch government is cutting the arts and the culture budget heavily, the museum has planned to sell the Africa collection to private collectors and to focus solely on Asia and Oceania in the future. Through the sale the museum hopes to generate a small sum of 60 million euro and be independent from government subsidies. The Netherlands seems to be the only country in the world that has capitalised heritage through proposing such a sale.

African museums, Dutch ethnology museums and the Dutch Cultural Council have been strongly opposed to the proposed sale. The Dutch newspaper NRC reported that director Stanley Bremner is tired of all the (international) critique: “The Netherlands is obviously not ready yet for this modern form of museum management.” Contradicting messages on the proposed sale reached the Dutch media. At first it seemed like the municipality would agree with the sale but only a few days later the municipality, who owns the collection, decided to postpone its final decision. The municipality will discuss how to handle the advise from the Dutch Cultural Council, who has advised that a Dutch core collection should be established. It is not clear if the Africa collection would fall under this new core collection but if it would, the collection would be protected.

Africa Collection Wereldmuseum Rotterdam (Photo by Lex van Lieshout)

Dutch ethnological museums such as the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam and The National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden do not appreciate Mr. Bremner’s modern form of museum management because the collection would disappear in the hands of private collectors. Instead the museums find that the collection should be protected as Dutch cultural heritage. Other reasons why critics believe the collection should not be sold relate to history of the Dutch in Africa. Experts state that the objects bear witness to the history of the so-called ‘expansion of Dutch activities’ in Africa. Most of this ‘Dutch activity’ in Africa was concentrated in three regions: Ghana, South Africa and Congo. These ‘activities’ undertaken by the Dutch inform, alongside with some Christian converting practices, the meaning and history of the Africa collection. For instance, the relationship between Ghana and the Netherlands goes back for around 400 years: during the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, the Dutch had captured Elmina from the Portuguese on the Gold Coast in Ghana, which became the Dutch headquarters for slave trade until the British seized it.

The World Museum’s collection consists of around 10,000 objects from, amongst others, West-Ghana, Liberia, Nigeria and Congo. They were given to the museum at the end of the nineteenth century. The museum started to collect its own art objects afterwards. The proposed sale of the Africa collection is to be understood within the historic context of ethnological European museums. This history is grounded in the practices and disciplines of colonial ethnology and anthropology. Colonial ethnology produced certain racial images around Africa that are still visible in the mainstream western imaginary of Africa today. The representation of Africa within the ethnological museum was highly influenced by these imaginaries and stereotypes of the ‘African’.

Mami Wata Legba, voodoo sculpture (1973) from the Lomé region (Africa Collection Wereldmuseum Rotterdam)

Due to an increasingly multicultural society in the Netherlands, ethnology museums were forced to change the way they represent ‘other’ cultures. The previous (historical) ‘other’ that has been on display in the museum space is now attracted to come visit the museum. This impelled ethnological museums to think about the concept of heritage. For instance, the National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden has initiated a project that dealt with the changing role of the ethnological museum in a changing society. This project was relatively successful because it critically engaged with questions of ‘culture’, ‘ethnicity’ and representation in the museum space but there’s no way of denying that the National Museum of Ethnology still largely adheres to the practice of displaying neo-traditional aspects of material culture. The idea of heritage has always been existent before but the raison d’être for museums changed. The heritage discourse in the Netherlands is to a great extent governed by policies, rules and regulations. However, heritage is also strongly related to remembering, commemorating and forgetting sites and events in history, which can be viewed as cultural process. The Africa collection is not only cultural heritage because of its material aspects but also because of the history around the collection. The role of the Netherlands in the time of slavery and colonialism and the legacies thereof form and shape the importance of the Africa collection.

The Netherlands seems to suffer from collective historical amnesia with regard to its role during slavery and colonialism in Africa. Or perhaps we should call it aphasia for describing metaphorically the cultural “inability to recognize things in the world and assign proper names to them,” a concept that American historian Ann Laura Stoler has introduced with regard to colonial histories in Western societies. In the debates around the proposed sale the colonial history of the Dutch is hardly mentioned. Experts are interested in what the art objects could tell about the relations between the Dutch tradesmen and Africans but not in placing this within a colonial historic framework that would actually make a contribution to Dutch history.

This history, the intangible nature of the collection, is what African museums are concerned about. Dutch ethnological museums do not refer to this history but to the obligation to protect Dutch cultural heritage. Rudo Sithole, director of — yes — “AFRICOM,” the International Council of African Museums, has indicated that African museums must have a role in the sale especially because it is not clear which objects have been stolen or rightfully bought or donated. Last year, Mr. Bremner stated that African museums would never be able to buy the collection and that the climate in Africa would not be appropriate for African art objects. The World Museum has not consulted the African museums.

Nkisi Nduda, (2nd half 19th century) from DRC (Africa Collection Wereldmuseum Rotterdam)

The Africa collection is seen and treated by the Wereld Museum as a commodity that is detached from its historical context. In a country where Sinterklaas is seen as an important cultural event that deserves to be protected as cultural heritage (the problematic figure of Black Pete magically disappeared in the request put forward to UNESCO), where the research and commemoration of slavery in the Netherlands has experienced an ultimate low through the closing down of the National Institute for the Study of Dutch Slavery and its Legacy (more about this in a future post), and in the light of the commemoration of 150 years of the Dutch slavery abolition this year, one would expect museums like the World Museum to start dealing with their historic legacies instead of selling them off.

* Chandra Frank recently graduated from the Centre of African Studies at the University of Cape Town where she wrote her master’s dissertation on the proposed sale of the Africa collection at the Wereld Museum Rotterdam. She is currently based in Amsterdam and has a strong interest in heritage, identity and culture.

When videos of abuses go viral in Angola

For the past two weeks, most Angolans that frequent Facebook and other social media sites viewed and shared two particularly gruesome videos. One showed prison officials severely beating incarcerated men in the Comarca de Viana (Viana Jail), while the other, even more heinous, showed several men brutally beating and abusing two women who had allegedly attempted to steal a bottle of Moët & Chandon from the shop the men owned. The latter video lasts 13 long, uncomfortable minutes and among its more difficult scenes is the one in which an attacker forcibly kisses one of the women while the others laugh, and another in which the shop-owner beats the women with the blade of a machete. The video shows several men participating in the beating, while others, including women, stand by and watch while egging on the attackers. Both videos went viral in Angola.

Both evoked very strong emotional reactions, particularly the second video. Within a matter of days, both had been mentioned on state television and talked about in public and private newspapers. It marks the first time that videos went truly viral in a country in which only about 5% of the population has access to the internet.

The videos come at a sensitive time. People continue to be shocked at the level violence permeating Angolan society. The torture and murder of a popular and well-liked teen last year at the hands of his teenage friends — which prompted a march against violence along Luanda’s new Marginal — is still fresh in many people’s minds. But the most remarkable outcome of this mass sharing of media was that the Angolan Attorney General, or Procuradoria Geral da República (PGR) as it is locally known, actually did something about it. And they did it publicly and swiftly.

This comes fresh off the PGR’s unexpected condemnation of the Brazilian Igreja Universal do Reino de Deus (Universal Church of the Kingdom of God). They followed that with the launch of a criminal investigation against the politically well-connected Church for the stampede that killed 16 faithful at a New Year’s event in Luanda, the PGR, has once again positively surprised Angolans.

Days after the prison video began circulating on Facebook and Club-K, the most widely read Angolan web portal, the PGR opened an official inquiry into the matter and suspended the prison warden along with several of his subordinates. Their reaction to the horrid woman abuse video was even quicker. As condemnation reached fever pitch on Facebook and YouTube, the PGR took to the airwaves to announce, on national television, that they had not only found the establishment in which the attack had taken place but had also arrested the culprits.

In effect, the PGR arrested citizens based on digital evidence that circulated widely in Angola’s fledgling social mediasphere. Such an act by an organ of state is completely unheard of in Angola, and caught many of us by surprise. The Angolan government, which likes to pretend we live in a democracy and carefully cultivates that illusion, still grapples with concepts such as “rule of law”, “civil liberties”, “press freedom”, and above all, “freedom of expression”.

Less than two years ago, at the height of the Arab Spring, President dos Santos scathingly denounced social media and as a direct result the ruling party unsuccessfully tried to introduce a bill in parliament that would make it illegal to share videos, pictures, and recordings without the subjects consent. As Louise Redvers reported for the BBC back in May 2011, “under the proposal … anyone criticizing the government on social media sites such as Facebook … could have faced up to 12 years of prison.”

The government’s sudden embrace of digital evidence circulated on social media is therefore even more extraordinary.

Throughout 2011 and 2012, the youth protest movement Central Angola 7311 tried to use social media to highlight the ongoing, state-sponsored abuses against friends and members of their group. The nadir of this violence occurred when opposition leader Filomeno Vieira Dias was struck on the head with an iron bar in broad daylight right in front of police officers; other members of the movement, most not older than 30, suffered severe head wounds as they were attacked with iron bars and sticks.

These thugs, which locally came to be known as ‘militias’, grew so brazen that they even took to pre-emptively attacking the protest organizers in their own home on the eve of a planned protest; the blood-caked floor of organizer Carbono’s house was featured on the Al-Jazeera documentary about Angola’s protest movement. And Mbanza Hamza, also featured prominently on the same documentary, still sports a deep, permanent scar that runs along his head, borne out by the iron bar of some government thug drunk on irrationality.

The police and thug violence became a regular fixture of anti-government protests. It was regularly filmed by passersby and protesters on their mobile phones. Several of these videos made their way to YouTube, Facebook and the movement’s website. All of them were then sent to PGR, time and again, to help them find those responsible. The PGR never uttered a word about them and never acted on the evidence they received. Instead, the state prosecuted the youth involved in the protests and wrongly accused them of attacking police officers. The video evidence, which not only directly contradicted the accusations but actually distinctly showed that the police acted in tandem with the thugs that beat defenseless citizens, was, inexplicably, inadmissible in court. The defense attorneys representing the protesters described the court proceedings as a “tragicomedy”.

Most of the accused spent 43 days in Viana Jail for crimes they did not commit. Coincidentally, it’s the same jail featured in one of the videos described above. Additionally, two citizens, Isaías Kassule and Alves Kamulinge, have been missing since May of last year for participating in anti-government protests. Their disappearance is one of the most talked about topics in Angolan social media and has even prompted further protests. Astonishingly, the PRG recently told national television that they “had no idea about the disappearance” because “they do not follow independent media.”

In reality, the violence in Angolan society so visible in a time of peace is nothing new. Instead, people that would normally not be aware of it now have no choice because it shows up on their Facebook newsfeed. For the violence in Angola comes from the very top: the State.

Just last week for example, the government forcibly evicted 5000 people from Luanda’s Cacuaco district without previous warning. The evicted included pregnant women, infant children, and two children who died by falling into a ditch as they ran away from seven low-flying helicopters. Yes, helicopters, because the local government used helicopters (seven), bulldozers, and a 500-men force comprised of the police, the military and rapid-intervention security forces to forcibly evict people without warning.

With such an example coming from the top, is the violence in our society truly that shocking?

PGR’s actions are entirely commendable and deserve praise. I was one of many Angolans that took to social media to congratulate them on finally using a tool that has been at their disposal for years. Justice was done for the two women brutally abused, and the suspension of the Viana Jail warden was nothing less than the prisoners deserved. But it’s about time that these State Institutions started serving the country as a whole instead of the whims of a single party. The country, and its citizens, is changing. It’s time the PGR, and the rest of the government, wakes up to this new reality and starts serving the people they were given a mandate to serve. Because as long as the PGR picks and chooses which cases they solve, even their noteworthy actions will ring a bit hollow.

February 13, 2013

What we learned from Kenya’s first ever televised presidential debate

Kenya had its first ever televised presidential debate on Monday night. Like many others I was watching the livestream online and Tweeting while at it. I have included some of my real time tweets in this post (see below). A number of things stood out during the debate. The incumbent Prime Minister Raila Odinga—referred to acronymically in my tweets as “RAO”—was poorly prepared. In what’s been covered in the media as a two-horse race between him and Uhuru Kenyatta (the son of Kenya’s founding president), Odinga’s attempt to adopt Obama-style “change” rhetoric failed to dazzle. Meanwhile, Uhuru (referred to as “UK” in my tweets) was dogged by questions about the ethics of his running for the presidency while facing charges at the International Criminal Court (ICC), prompting him at one point to refer to his trial at the ICC as “a personal issue” that would not affect his work as president. As expected, Paul Muite, a prominent figure in the pro-democracy movement of the early 1990s, was a wild card, frequently calling out both the Prime Minister and Uhuru Kenyatta on all matters ICC-related. The former justice minister, Martha Karua, the only female candidate on stage, sailed through very well in my opinion. Banker Peter Kenneth was nowhere as good as expected. His tough talk on security seemed an attempt to overcompensate for his image as a nice guy. However, Kenneth did score massive points as he was the only one who called out (and put figures to) the bloated national debt accrued as a result of Kibaki era neoliberalism. Musalia Mudavadi had us all a little surprised when he declared privatization—of parastatals and even the port of Mombasa—as the panacea for Kenya’s revenue problems. Mohammed Dida provided some unusual comic relief to the anodyne atmosphere. And James ole Kiyiapi (he has a Facebook page) put in a strong performance, particularly when the panel discussed education—there is a massive shortage of teachers in schools, a political point most of the other candidates failed to capitalize on.

Kenya had its first ever televised presidential debate on Monday night. Like many others I was watching the livestream online and Tweeting while at it. I have included some of my real time tweets in this post (see below). A number of things stood out during the debate. The incumbent Prime Minister Raila Odinga—referred to acronymically in my tweets as “RAO”—was poorly prepared. In what’s been covered in the media as a two-horse race between him and Uhuru Kenyatta (the son of Kenya’s founding president), Odinga’s attempt to adopt Obama-style “change” rhetoric failed to dazzle. Meanwhile, Uhuru (referred to as “UK” in my tweets) was dogged by questions about the ethics of his running for the presidency while facing charges at the International Criminal Court (ICC), prompting him at one point to refer to his trial at the ICC as “a personal issue” that would not affect his work as president. As expected, Paul Muite, a prominent figure in the pro-democracy movement of the early 1990s, was a wild card, frequently calling out both the Prime Minister and Uhuru Kenyatta on all matters ICC-related. The former justice minister, Martha Karua, the only female candidate on stage, sailed through very well in my opinion. Banker Peter Kenneth was nowhere as good as expected. His tough talk on security seemed an attempt to overcompensate for his image as a nice guy. However, Kenneth did score massive points as he was the only one who called out (and put figures to) the bloated national debt accrued as a result of Kibaki era neoliberalism. Musalia Mudavadi had us all a little surprised when he declared privatization—of parastatals and even the port of Mombasa—as the panacea for Kenya’s revenue problems. Mohammed Dida provided some unusual comic relief to the anodyne atmosphere. And James ole Kiyiapi (he has a Facebook page) put in a strong performance, particularly when the panel discussed education—there is a massive shortage of teachers in schools, a political point most of the other candidates failed to capitalize on.

All in all the questions posed by the moderators were oftentimes easy pitches that the candidates hit for home runs. Without further ado, here’s Kenya’s first ever presidential debate via Tweets:

Because Kenyans speak so slowly, our presidential debate is going to take about six hours.—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

Muite is going to harvest rainwater and end "negative ethnicity." @GeeBrunswick—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

Raila is as prepared as the person next in line to the throne would be, in a debate with Commoners. So, NOT PREPARED.—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

Raila had a Summit, then a Pentagon, then a Triangle, then a Cord. LOL—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

I actually believe RAO and UK when they say they are best buds. At the golf club and #danguroni—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

So the #KEdebate13 is about tossing easy balls to RAO and UK then ooohing and ahhhing at their home runs.—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

I'm waiting for question time from the audience, when MOI is first in line to the mic and all the candidates faint on stage #KEdebate13—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

UK says ICC is a "personal problem" #KEdebate13—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

UK talking about ICC as a personal issue and making it sound like an internet porn addiction #KEdebate13.—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

Now the debate is like an intervention for UK, who is addicted to internet porn through Skype #KEdebate13—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

I'm still waiting for that moment when Moi and Ashton Kutcher run onto the stage and shout YOU'VE BEEN PUNKED. #KEdebate13—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

RAO is name dropping his patsy like a rapper on a video: Koffi Annan, Kibaki, Obama, God, Dennis Oliech.—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

Martha Karua sounds like an NGO person who drank World Bank bottled water before the debate began #NGORhetoric #KEdebate13—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

RAO just called Migingo "a piece of rock on the lake." WOW. The truth is OUT. #KEdebate13—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

Peter Kenneth now sounds like a trigger happy NRA Republican now. He is like a Caudillo. #KEdebate13—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

@looplikesreplay @somalifarah Our security rhetoric says Somali = Terrorist. This is problematic.—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

@looplikesreplay @somalifarah "Terror" is no reason to pick on one element of our society and send them to concentration camps.—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

@ngwatilo Vision 2030 = ENOUGH BOREHOLES—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

Dida brings up the DEVIL WORSHIPING problem in Kenya. And the ambulance jokes about ferrying BHANG. #KEdebat13—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

Peter Kenneth raises the VERY IMPORTANT bloated debt from KIBAKI ERA NEOLIBERALISM #KEdebate13—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

OK, Mudavadi wants to privatize EVERYTHING AND EVERYONE. #KEdebate13—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

RAO now talking about the Prime Minister in the third person, like he is not the PM. #KEdebate13—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

In the next government RAO is going to achieve everything he did not lift a finger to do in this government. AWESOMEGAZM!!! #KEdebate12—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

MUITE WANTS TO PRIVATIZE ALL BABIES AND UMBILICAL CORDS!!! Including RAO's CORD. #KEdebate13—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

FINALLY THE JIGGER INFESTATION!!! #KEdebate13—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

I KNEW SOMEONE WOULD MENTION JIGGERS!!! #KEdebate13—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

For years I have been trying to make JIGGER INFESTATION a political hot button in Kenya. Success!!! #KEdebate13—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

JIGGERS are Kenya's no. 1 threat to national security!!! They are here, in our feet, and already sucking our blood! #KEdebate13—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

A Dida government would conduct BREATHING EXERCISES nationally, to prevent JIGGER INFESTATION. #KEdebate13—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

My money is on every candidate breaking into vernacular language for the closing arguments. And RAO just growling three times. #KEdebate13—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

RAO is running for the Kenyan presidency using Obama Change rhetoric. So we should expect #DRONES. #KEdebate13—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

Mudavadi says he is "the safe pair of hands" to masturbate Kenya to democracy. #KEdebate13—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

Uhuru now delivering his closing statement via Skype, under the influence of MASHETANI DARK FORCES. #KEdebate13—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

Dida is now removing his mask to reveal that HE IS REALLY ASHTON KUTCHER. PUNKED, mofos!!! #KEdebate13—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

So everyone pretty much sidestepped OUR INVASION OF SOMALIA and OUR internal racism against Somali Kenyans #KEdebate13—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

Peter Kenneth's tough talk on security scares me a little, to be honest. Sounds like he would invade Uganda. #KEdebate13—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

And now for some of the usual run of the mill ANODYNE political analysis on Kenyan television #KEdebate13—

BringMeTheAfricanGuy (@kweligee) February 11, 2013

February 12, 2013

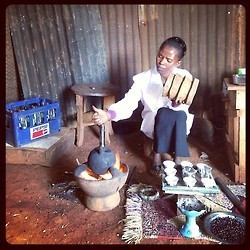

Meet creative director and photoblogger … Metasebia Yoseph

Our new weekly feature profiling the people behind blogs and/or tumblrs curated by Africans, on the continent as well as in the diaspora. The posts will highlight influences, genres, and point to the kinds of work being produced by young African photographers/curators. Most of those featured are at the start of their careers. We launched this feature last week with Batswana photographer Karabo Maine. We hope to introduce you to artists you either have not heard about or whose work does not saturate the mainstream (yet). This week’s post is co-authored with Genet Lakew. So here we go: meet Metasebia Yoseph, an Ethiopian-American curator and mixed media artist.

Metasebia is the founder and executive director of creative consulting company Muse Collective. Born and raised in Washington, D.C., she is currently in Ethiopia finalizing research for a coffee table book on the country’s enduring coffee traditions. The book is part of a transmedia project that includes a tumblr blog, appropriately titled A Culture of Coffee. Metasebia uses the blog as a space to share rich photographs of coffee, as it is harvested, roasted, grounded, brewed, and finally poured into small cups to savor with family, friends and neighbors in the spirit of Ethiopian culture. Through the blog and forthcoming book, Metasebia uses images, both her own and those produced by others, to delve into the stories of our daily cup of Joe.

Why coffee? How did you gravitate toward this specific cultural tradition? What kind of social significance does coffee have?

Why coffee? How did you gravitate toward this specific cultural tradition? What kind of social significance does coffee have?

My background is in art history and now in my graduate program I specialize in communication, culture and technology. I’ve always focused my research on Ethiopian art and culture. For my first book project I was looking to highlight an Ethiopian cultural practice that would translate to a broader audience – coffee was the obvious choice. Coffee originated in Ethiopia and has become interwoven into the Ethiopian identity and everyday social experiences. The coffee ceremony here is also unique, with several variations throughout different regions and ethnicities in Ethiopia, making it an interesting study.

Do you personally take all of the photos that are on the blog? If not, where do you find them?

I wanted to incorporate technology and social media into the project and create a space for cross-cultural exchange through the Culture Of Coffee blog. I share aspects of the traditional Ethiopian Coffee ceremony and its legacy across the globe. I also encourage my audience to share their personal coffee experiences and cultural practices. Some of the images on the blog are those I have collected through my travels or come across in my research, while others have been submitted by fans and followers of the project.

How long have you been working on this project and where are you currently in the process?

How long have you been working on this project and where are you currently in the process?

I have been working on this project for 2 years. I am currently finalizing the research and compiling the content. I am also in the process of securing funding for publishing.

It seems you have started the 3-month journey to the coffee producing regions of Ethiopia. The photos are beautiful so far. Where have you been so far and what places do you have yet to visit?

So far, I have visited coffee farms and cafés in Borana, Yirgacheffe, Yirgalem, Sidamo, and Dire Diwa. I still hope to travel to Mekelle, Wollo, and Jimma before I return to DC. I selected these places because they are known for their coffee quality and distinctive coffee rituals.

How do you explain your project to the people you meet throughout Ethiopia? Do you have to imply that you’d like for them to make coffee or is it an automatic gesture?

Coffee is so much part of the Ethiopian social experience that I don’t really have to explain my presence in order to enjoy a cup or take part in a ceremony; it’s so readily available. However because it’s so ubiquitous, I do have to do more inquiry to get at the roots of the practices. I have been lucky enough to get institutional support from the Institute of Ethiopian Studies, and officials within the Ethiopian coffee sector, who have provided great guides and intermediaries.

Describe what it’s like to be a guest in someone’s home for a coffee ceremony in Ethiopia and in the U.S. What kind of sentiments does it stir? Are there any variations in the preparation/presentation?

The coffee ceremony that might be experienced in the US amongst the diaspora community is similar to the iconic version that most Ethiopians are familiar with. This is the slow-coffee experience where coffee is washed, roasted, ground, and brewed right in front of the guests. It is very sensory and aromatic, and often gives people time to converse and connect. Although there are some variations in the utensils used or the spices added to the brew to distinguish the taste of bunna between houses, the ceremony is essentially the same. However, the practice can vary dramatically in other regions in Ethiopia. For example, in Oromiya there is a ritual called Bunna Kalla (coffee slaughter), where whole coffee cherries are roasted and then re-fried in butter. The charred beans are then eaten to commence any major social event or gathering. Regardless of these ritualistic variations, I think anyone who partakes in these ceremonies is attempting to connect with something sacred.

What do you hope to stir in the hearts and minds of your blog followers?

My hope is to reconnect the larger coffee drinking audience back to the Ethiopian origins of coffee and celebrate the diverse ways that Ethiopians have come to celebrate and ritualize coffee. Centuries ago Ethiopia shared the coffee crop with the world, now its time to share in their Coffee culture.

Your blog also features photos of coffee cups from different cultures and countries. Speak on the universal nature of coffee.

I’m very fascinated with the evolution of coffee culture through out the world. Coffee has proliferated and taken root everywhere, and in turn every part of the world has developed its own relationship with coffee, as well as their own unique coffee traditions. I have tried to highlight those traditions through the blog and hopefully spread awareness of these varying practices.

What are the next steps for the blog and subsequent book?

My plan for the blog is for it to endure as a space for on-going cross-cultural exchange, long after the book is published. Books tend to be static and once published remain frozen, however the blog allows for the coffee experience to evolve along with the culture.

* Metasebia resides in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Her website is here. Feel free to message us candidates for this series to our Facebook and Twitter pages.

Future Radioheads

Colin Greenwood and CRF facilitators at the local flower market in Cape Town

Few subjects manage to pull our critique trigger as handsomely as Western celebrities on an Africa related mission. But when a rock star gets it right and decides to do some awesome stuff during his first-ever visit to the continent and proves deserving of praise, we’re the first one to crack the nod. So when Radiohead’s Colin Greenwood went on a 10-day radio tour in South Africa in January and recorded some audio in studios across the country, we were all ears.

As it turns out, he spent the lion’s share of his tour in the studio. But instead of his usual companions Thom Yorke, Philip Selway, Ed O’Brien and Jonny Greenwood, he shared the space with children. He wasn’t there to record tracks with them, nor did he flood them with ideas or insights about rockstardom, music or politics. Instead, he was there to listen and learn from his young hosts, who, as trained reporters, showed him how they produce their weekly talk radio shows for their community radio stations.

CRF Youth reporters at Moutse Community Radio Station, Limpopo

Had he not become a rockstar, Colin confessed, he would have tried his hand at radio reporting. “I’m just fascinated by radio in the modern world,” he says. “My mom brought us up with radio, she called it a window into the universe. Talk radio tells stories, brings stories from one side of the world to the other and can now be shared by digital stuff.” And it was the digital stuff that (back in England) familiarized him with the South African youth radio shows. “I had listened to some of Children’s Radio Foundation’s shows on Soundcloud and I just loved the stories of these kids. I was intrigued and moved by these stories. So when I was invited I was absolutely thrilled.”

It was the Children’s Radio Foundation (which we previously blogged about here) that invited him to meet some of the young creative minds that impressed him so much.

In charge of setting up the visits and cruising him around from station to station was one of CRF’s trainers Lesedi Mogoatlhe. She took him to Kuruman, where Colin took part in an afterschool radio production session at Kurara FM. “It was just fantastic to see them organizing their time to make these really cool programs,” Colin tells us. “The kids and the energy in the studio reminded me of when we started our band; we were like fourteen years old, organizing our time in our own space, apart from adults and teachers and stuff like that.” During their weekly shows, the youth discuss all kinds of topics, from family life and sex education to violence, bullying and teenage pregnancies. Colin says, “One girl at Kurara FM told me that the cool thing about radio for her was that the elders in her community now actually listen to what she has to say. She is more confident to say what she wants to say and to share what goes on in her life.”

For Colin, CRF’s approach towards youth development and participation works so well because “they don’t tell the kids what to do; they just show what can be done and how to do it.” So when Lesedi took him to Moutse Community Radio Station in Limpopo, it was the kids who decided to take him to the streets to interview wheelchair-bound Sylvia, asking her about her experiences as a disabled woman in their community:

The conversation with Sylvia motivated the kids to take the topic of disability in their community further in a next show. They started to organize and plan it straight away. But first, Colin tells us, they wanted to produce an item which was invented on the spot; “Which township is the most rocking?” By visiting four different communities, interviewing knowledgeable people and conducting vox pops, the children said they wanted to promote the positive stuff that goes on their area.

At Manenberg (Cape Town), he was subjected to “the most fun interview I’ve ever done” (and the best-spent 2:45 minutes of your day):

The kids, as young as seven years old, asked him questions about his family, tour bus, performance nerves, the names of his children’s teachers and his favourite games. They also listened to some Radiohead tracks together (which, according to Colin amounted to some “astute A&R work”). “They liked the groove on Reckoner, but preferred the song High and Dry.”

According to Lesedi, it was his openness, curiosity, humility and his specific and grounded interest in radio and youth that made his engagements so great. This clearly comes through in his blog. “He often mentioned that, had he not become a rockstar, he would have wanted to become a reporter,” Lesedi says. “He told us that he believed curiosity is the highest form of intelligence”. And he showed a great deal of curiosity himself. “The man was on a mission to learn and really immersed himself in the world he entered.”

CRF Youth reporters from Manenberg, Cape Town

So what exactly did he learn about youth radio? “It’s about the confidence boost,” Colin says, “if you put a mic under kids’ noses, you give them a platform to express themselves. These kids can actually make a leap with just a microphone and a platform.”

So Colin had an awesome time. And that is great. But what does his visit mean for the reporters and CRF’s youth projects? According to CRF’s assistant director Nina Callaghan, “It is a great incentive and boost for young reporters to know that there is someone with some clout in the world who believes in what they do, who believes in them and is supporting their efforts. For CRF it means that we have an ambassador with a very wide reach across the world who can raise awareness about our work, specifically the importance of youth development, and to do so in such a wonderfully sincere and authentic way.”

Colin Greenwood and CRF youth reporters at community radio station Valtaar FM, Taung, North West Province

CRF currently works with 50 different project sites in Ethiopia, Zambia, Tanzania, Liberia, South Africa and the DRC. With their local radio station partners, they train local youth to make their voices heard as reporters in their communities. For more photos, updates and info LIKE their Facebook page.

Pop Culture and Pirate Humanity

The tragic robber-hero. The mystical gunslinger. The cerebral crime-lord, drawn into events beyond his control. One of the most straightforwardly literal ways in which popular culture is able to challenge official ideology is in creating complexity and human drama around criminals that the state would rather have seen as villains whose only wish is evil. From Dick Turpin to drug-dealer hip-hop, from Waltzing Matilda to dacoity films, from Stagolee to The Last Tycoon, there’s a definite sense of resisting the most simple explanations, inherent in the depiction of criminals as human beings capable of having complex motivations, heroism, mistakes, weakness and resolve. (Even in their most archetypal guises.) All of which definitely makes this hip-hop video from Somalia’s Waayaha Cusub all the more interesting.

Barely any group has been as de-humanised as much in recent history as the pirates in the Gulf of Aden. The news in blanket fashion depict them as a dark force of nature, without voices or obvious motivations. In the massive, 18,000-word Wikipedia article Somali pirates are treated almost like vermin to be rooted out; nowhere in this exhaustive text cares to mention even with a casual glance what could possibly drive them, nor solutions other than shooting, warfare and (possibly private, mercenary) invasion. (It is difficult not to compare to the power-play propaganda from yesteryear; intensely false images, like those propagated by the British in the 50s of Mau Mau as barbarian ghosts descending invisibly in the night to slit colonialists’ throats.)

This song and its video, on the other hand, is far from the stereotype. Instead, here is a lyric that’s an appeal: youth, do not become pirates, you’re worsening our prospects for peace and development! One fictional young pirate’s tale forms a centerpiece and a warning: his story of being shot at, almost drowning and slowly reaching shore is a pirate’s possible grim fate. And at the same time it’s got the pirates as gangsta-style hard men, and drapes itself in pirate iconography, and you get a sense of the intense appeal the lifestyle presents. The container ships that are the focus of all Eurocentric media depictions form just an ominous, hazy background, a reminder of world inequalities. And it has everything those de-humanising stories miss: a feel of the complexity, of the humanity, of the implied questions that should rightfully surround our understanding.

* Thank you to Amal Shair for translation help for this story.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers