Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 490

February 19, 2013

What’s the matter with Morocco

As Egypt and Tunisia grab the recent headlines, Morocco has gotten little attention in Western media. We read little or see less on global TV news channels about the country, which has been one of the quietest and most stable Arab countries since the start of the “Arab Spring.” Morocco has done better politically and economically than its neighbors in North African nations. This is largely due to speedy reforms implemented by the King Mohamed VI, and the fact that the protest movement did not call for the overthrow of the regime unlike in Egypt, Libya, and Tunisia. Yet despite these factors, problems such as high unemployment, looming economic reforms, and increased repression and police brutality, risk to make things worse for the country.

King Mohamed VI took power in 1999 at the age of 35 after the death of his father, Hassan II. Unlike his authoritarian father who ruled Morocco with an iron fist, Mohamed VI is less repressive and more liberal. His reaction to protests led by groups like the February 20 Movement was for the most part non-violent. Many agree that if Hassan II were still alive, it is likely that he would have tried to brutally suppress the demonstrations, and we could have witnessed similar scenes of chaos happening on Moroccan streets, as the ones that happened in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya.

Seeing how things quickly deteriorated for other North African leaders, the king reacted swiftly to appease the demands of the population. In a televised speech given March 9, 2011, the king acknowledged the grievances of the public and announced to reform the constitution, and give more power to an elected parliament. At the same time, the country increased its public spending with subsidies for food and fuel to appease the population. Despite a boycott by the Moroccan opposition, the referendum on the draft constitution was passed by 98.2 percent according to the interior minister.

A factor that worked to the king’s favor is that he is still rather well liked among the population. James Gelvin states in his book, The Arab Uprisings: What Everyone Needs to Know, that “protesters demonstrating in in February 2011 throughout Morocco demanded constitutional changes that would limit the powers of the monarchy; they did not demand the establishment of a republic.” The protesters did not call for the monarch’s removal, instead they were demanding reforms to lessen the monarchy’s power, more respect for human rights, and more jobs for the youth.

Laws that protect free speech and free press are included in a new constitution, but critics say that the language is vague and contradictory. Despite these new guarantees, journalists and artists still face imprisonment or harassment if they criticize the king, or if they expose corruption. At the same time police are increasingly using brutal tactics to break up protests, something that was relatively absent since the start of the demonstrations in 2011. The rapper Mouad Belghouat is serving a one year sentence for one of his songs which deals with police corruption. In its 2013 World Report, Human Rights Watch claims that those who campaign on behalf the Saharawi cause, demanding an end to discrimination or calling for autonomy, also face repression and imprisonment.

The approval of the new constitution, as well as the parliamentary victory by the Islamist Justice and Development party has contributed to Morocco’s stability. Yet the effects of a drought and the economic crisis in Europe, has negatively affected Morocco’s GDP and exports. Tackling the depressed economy and creating jobs will be one of the main tasks for the parliament.

Morocco has been spared from violent protests and riots that have plagued other North African nations, but that does not mean that things will remain this way indefinitely. A new updated constitution and an Islamist majority in parliament are a sign of political improvements, but many think that these changes are only cosmetic, and that the king still holds too much executive authority. With a combination of an underperforming economy, high unemployment, upcoming subsidies reforms that will mostly affect the middle class, and a rise in police brutality, things could still take a turn south for the otherwise stable country.

* Youssef blogs about International Affairs at Thought Projector International. Follow him on Twitter at @youssbenlamlih.

In Angola, the Generals will be just fine

Last week the Portuguese Attorney General’s office dismissed a case of libel and defamation against Rafael Marques and the Portuguese publisher Tinta da China. The criminal case against Marques and Tinta da China was filed by nine Angolan generals, all of whom own are part owners in Sociedade Mineira do Cuango, a mining company, and Teleservice – Sociedade de Telecomunicações, Segurança e Serviços, a telecom and security firm, that work in the diamond mining regions of Eastern Angola.

Marques is an investigative journalist and human rights activist. The Portuguese Attorney General’s office decided that Rafael Marques’s book Diamantes de Sangue: Corrupção e Tortura em Angola (Blood Diamonds: Corruption and Torture in Angola) published by Tinta da China in 2011, is protected under constitutionally guaranteed laws of freedom of speech and expression in Portugal.

The book details the involvement of the companies in nearly one hundred killings and hundreds more tortures. And it shows the links between the generals and the companies. Media in the West as well as in Africa heralded this victory for free speech in Angola (although the case took place in Portugal). Novo Jornal, part of Angola’s independent press, in their February 15th edition, noted the irony of the closure of two court cases on the same issue, neither one going forward, but for diametrically opposed reasons.

In Portugal, the generals’ case against Marques and Tinta da China was thrown out in the name of free speech and the lack of any public crime committed. In Angola a criminal case filed by Marques against the generals was also closed recently. He had lodged a criminal complaint against the generals at the Angolan Attorney General’s office in June 2011 for acts of torture and homicide in the diamond mining areas where the Sociedade Mineira do Cuango and Teleservice operate. In June 2012, the Angolan Attorney General’s office archived the case for lack of evidence, and in November 2012 they notified Marques of their decision.

But beware the bling of banner headline announcing free speech victories. Further down on my google news feed for the same day was this announcement: “U.S. Army Delegation Visit Angola.” That’s right. Six high-ranking U.S. Africom officers based in Italy began a three-day visit to Angola last Wednesday, signaling a certain coziness between the U.S. armed forces and those of Angola.

The Generals will be just fine.

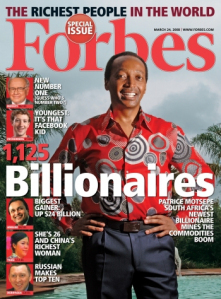

Extreme Makeover: The Patri$e Mot$epe Edition

Perhaps it is unfair to be skeptical of the announcement a few weeks ago by South Africa’s first black dollar billionaire, Patrice Motsepe, that he will donate half of the value of his family’s assets to charity under the guise of the Motsepe Family Foundation. The gesture – for want of a better word – is nothing to sneeze at: give or take a few hundred of million, the man is worth an estimated US$2.65 billion. The news, unfurled at capitalism’s annual backslapping extravaganza in Davos, took the South African press (and including those in foreign media) completely by surprise. The hacks had been speculating that his big announcement would entail the takeover of the morbid beast that is Independent News and Media (South Africa), one of the big media conglomerates in South Africa. (The company has been sold to Mandela’s former personal physician since.) The company is owned by Irishman Tony O’Reilly, who having downsized, tabloidized and juniorized its newsrooms within an inch of life, is cashing in and getting out before South Africa’s online media matures to hollow out his asset. Not surprisingly, the local media fawned over Motsepe’s decision, once it was out.

Perhaps it is unfair to be skeptical of the announcement a few weeks ago by South Africa’s first black dollar billionaire, Patrice Motsepe, that he will donate half of the value of his family’s assets to charity under the guise of the Motsepe Family Foundation. The gesture – for want of a better word – is nothing to sneeze at: give or take a few hundred of million, the man is worth an estimated US$2.65 billion. The news, unfurled at capitalism’s annual backslapping extravaganza in Davos, took the South African press (and including those in foreign media) completely by surprise. The hacks had been speculating that his big announcement would entail the takeover of the morbid beast that is Independent News and Media (South Africa), one of the big media conglomerates in South Africa. (The company has been sold to Mandela’s former personal physician since.) The company is owned by Irishman Tony O’Reilly, who having downsized, tabloidized and juniorized its newsrooms within an inch of life, is cashing in and getting out before South Africa’s online media matures to hollow out his asset. Not surprisingly, the local media fawned over Motsepe’s decision, once it was out.

Samples from the weekly newspaper Mail & Guardian–not a friend of the country’s new black elites–here and here.

In part my skepticism stems from South Africa’s very recent past, a past in which our man is deeply implicated, a fact that has largely eluded the headline writers, but of which he would certainly be aware.

Motsepe was born into an upwardly mobile, petty bourgeois Soweto family, that succeeded despite Apartheid. He grew up learning the tricks of the business trade hawking booze to township mineworkers, and helping to manage the family’s Soweto spaza shop. Armed with intelligence and a law degree from the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg he became, in 1994, the first black partner at the prestigious Johannesburg law firm, Bowman Gilfillin. In the same year he quit to become the owner-manager of a small mine contracting company, assiduously accruing profits and waiting for an opportunity to execute his big move.

In 1998 at the confluence of a strong Rand (the local currency) and low gold prices, he seized the initiative and acquired Anglo’s marginal mines at Orkney and Vaal Reefs on extremely favorable terms in a deal brokered by then Anglo CEO, Bobby Godsell. Having laid off 2500 workers–a third of the workforce at Orkney–the fledgling African Rainbow Minerals (ARM) saw the Rand tank and gold prices rise less than six months later, driven in part by a perceived increase in South African political risk (i.e. Thabo Mbeki).

In this ugly milieu, ARM thrived, paid off its debts, and Motsepe, well-placed to benefit from government policies requiring black shareholding in mining companies, began to expand his nascent empire. By 2002, the company listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, and in 2008 Forbes Magazine named him South Africa’s first black dollar billionaire.

In August last year the twitching corpse of what had passed for South Africa’s post-apartheid “miracle” died under a fusillade of police bullets alongside 34 black miners at Marikana. The massacre triggered a wave of strikes across the gold, platinum, iron ore and coal sectors, which at its peak saw 140,000 mineworkers lay down tools to demand a living wage and improved workers’ rights. The reasons for the strikes are myriad and complex, but against a backdrop of growing inequality and unemployment, Marikana and its aftermath brought into stark relief the ongoing plight of poor black workers, the bloated paychecks of their paymasters, and the structural features of the South African economy that reproduce misery and indignity day after day, decade after decade.

Motsepe’s wealth has been built at the interstices of these realities. ARM owns 15% of Harmony Gold and Motsepe is its Chairperson. Harmony’s Kusasalethu mine, responsible for 14% of the company’s gold production, reopened this week following two months of suspended production due to union rivalry which has left two workers dead, strikes, and a spate of underground sit-ins that crippled production in the final quarter of 2012. The company has locked out workers, some of whom were forced to sleep at its gates, and initiated section 189 proceeding to retrench 6000 workers. The Modikwa platinum mine, 41% owned by ARM, saw production suspended for 5 weeks in 2012 due to strike action. Motsepe is not immune to the labor relations landscape, and in 2012 was the Congress of South African Trade Unions’ (COSATU) largest private benefactor.

Motsepe may have been moved by the (momentary) bad press leveled at fellow black multi-millionaire, Cyril Ramaphosa, in the wake of the massacre at Marikana. Unsurprisingly, big black business has not demonstrated itself to be significantly different in practice to white big business – their practices suggest more continuities with apartheid inheritance (inequality, excess, etcetera) than change.

Is this Motsepe’s time to become a philanthropist to protect himself?

The best riposte to Motsepe’s sudden sense of altruism was actually published in a letter to the selfsame Mail & Guardian by a reader Jeff Rudin, who some readers may remember as a researcher at research institute in Cape Town:

It’s a strange world we live in. Even Alice in her Wonderland would probably be taken aback by the [media coverage of] Patrice Motsepe’s intention to give away half of his income. Left entirely unasked, however, is how the mining magnate amassed a net fortune of more than R20-billion and, moreover, did so in less than 20 years, from his humble beginnings as a (would-be) capitalist who had no capital.

The poverty of mineworkers – now exemplified by the Marikana massacre – sits grotesquely alongside the mountain of Motsepe’s wealth. Congratulating him for his generosity is like thanking someone who, having helped himself to your bank balance, your house and its entire contents, has the charitable compassion to buy you a second-hand bed for the shack you and your family are now forced to occupy.

This is not to deny that Motsepe is at least a bit different from other obscenely rich mining magnates. My focus is not on Motsepe the individual but rather on our dominant values. What sort of society fails to ask how an individual can possibly spend R20-billion? What sort of society applauds the Motsepes of the world while condemning mineworkers for their “greed” and lack of “patriotism” when they demand a living wage?

February 18, 2013

Meet photographer and blogger … Nana Kofi Acquah

Our new weekly feature profiling African photo-blogs and/or tumblrs, rolls on. For background and to see who we’ve featured before, see here. This week we are featuring Ghanaian photographer Nana Kofi Acquah. If you regularly read AIAC, you’d know this is not the first time we feature Nana or his work. Sean first noticed his work in October 2011 and last September Tom asked him about his 5 favorite photographs, so he is no stranger to the blog. This time, as part of our new initiative, Tamerra Griffin, a graduate student in Africana Studies and journalism at New York University, instead asked Nana about his background, his influences and the workings of his popular blog, subtitled “A window to Ghana and Africa.”

Our new weekly feature profiling African photo-blogs and/or tumblrs, rolls on. For background and to see who we’ve featured before, see here. This week we are featuring Ghanaian photographer Nana Kofi Acquah. If you regularly read AIAC, you’d know this is not the first time we feature Nana or his work. Sean first noticed his work in October 2011 and last September Tom asked him about his 5 favorite photographs, so he is no stranger to the blog. This time, as part of our new initiative, Tamerra Griffin, a graduate student in Africana Studies and journalism at New York University, instead asked Nana about his background, his influences and the workings of his popular blog, subtitled “A window to Ghana and Africa.”

What motivated you to start your blogspot page?

What motivated you to start your blogspot page?

I started blogging at a time when it really was expensive to commission a website for one’s self and I couldn’t afford one. Even though my initial reason for starting a blog was so I could put my photographs out there and hope they will bring me business, I quickly noticed the blog also gave me opportunity to share a whole lot more than pictures.

How do you decide on a post/story?

How do you decide on a post/story?

I don’t have any hard and fast rules. Even though I have made posts on my blog with pictures I took outside Africa, a typical blog post from me will be an African story.

Any pages that you visit regularly for great content and inspiration?

Any pages that you visit regularly for great content and inspiration?

I enjoy visiting photojournalismlinks.com because it is like an aggregator for all the strong photojournalism work going on in the world. aphotoeditor.com is another favorite site. I read a lot of random stuff, not necessarily connected to photography in any way. There is more to my life than making photographs.

Who’s your favorite photographer or photo movement on the continent and beyond right now?

Who’s your favorite photographer or photo movement on the continent and beyond right now?

When I started making photographs, I had very little education on African photography. There wasn’t much one could easily find, in fact the situation hasn’t changed much since then. I have discovered the work of some great African photographers over time but my initial inspiration came from legends like Henri Cartier Bresson, Richard Avedon and all those Life and Magnum photographers.

What to you makes your page stand out among others that feature African photography?

I think the difference between my blog and the others is how we see Africa. I don’t see Africa as a hopeless case, I see it as a work in progress. There is also the fact that most of the people who blog on Africa may not necessarily have the same photography and writing competence that I do. Before I became a photographer, I worked full time as a writer.

Your blog title is A window to Ghana and Africa. Do you feel that your page adds or changes the perception people have of Ghana and Africa?

Your blog title is A window to Ghana and Africa. Do you feel that your page adds or changes the perception people have of Ghana and Africa?

Changing perceptions is a tough call. I want to believe that to some extent I am contributing but I don’t consider that my objective.

I want to know about your experiences with subjects, since your photo essays seem to emulate written profile pieces of people. What is it like to photograph someone who has HIV? Do you make an effort to remain objective, or are you deliberately subjective?

I want to know about your experiences with subjects, since your photo essays seem to emulate written profile pieces of people. What is it like to photograph someone who has HIV? Do you make an effort to remain objective, or are you deliberately subjective?

I am genuinely interested in people and the stories of their lives; and I think most people can tell the difference between a photographer who wants to just get their pictures and go away, and the one who really cares about them. They say, “Prejudice is the padlock on the door of wisdom,” and I totally agree that it can also a big impediment to making great people portraits. A photographer’s job is not to judge. I am a storyteller. I want to hear about where people have been, where they are and where they are going. It is great injustice to photograph people but not listen to them.

I also want to know how you approach shooting photos in countries outside Ghana. You seem to be very aware of your “Ghanaian-ness,” especially when talking about politics. How does your “Ghanaian-ness” factor into these other spaces? How does it affect the level of access you can gain there?

I also want to know how you approach shooting photos in countries outside Ghana. You seem to be very aware of your “Ghanaian-ness,” especially when talking about politics. How does your “Ghanaian-ness” factor into these other spaces? How does it affect the level of access you can gain there?

I remember the Nigerian Immigration Officer who took one look at my passport and asked me in Pidgin: “Where you go get Ghana passport from?” She actually thought I was a Nigerian pretending to be Ghanaian. I have been called a Gambian in the Gambia, an Ivorian in Côte d’Ivoire, a Kenyan in Kenya, a Ugandan in Uganda. My “Ghanaian-ness” is only that visible on my blog. From my experience, people will never discriminate against you because you are Ghanaian, normally they will because you are a photographer and photographers cannot be trusted.

Finally, if you don’t mind, we also ask interviewees about things other than photography or their blogs. So, what’s your feeling regarding the recent developments in Mali?

Finally, if you don’t mind, we also ask interviewees about things other than photography or their blogs. So, what’s your feeling regarding the recent developments in Mali?

Mali is a beautiful country with very beautiful people. Just a year ago, it looked so stable and so calm and then this happens. We all know they’ve had leadership problems but that coupe d’état was not justified. It was the perfect opportunity the Islamists needed. I do hope that everything ends quickly and the people return to their normal lives.

And what about football? What were your predictions for the African Cup 2013?

I was convinced Burkina Faso would take the cup and my Nigerian brothers and sisters would weep with us. Obviously I can’t make a living as a soothsayer.

* Tamerra Griffin is a California native earning masters degrees in journalism and Africana studies at New York University. Her interests, both personal and academic, include feminism, pop culture and trans-Atlantic musical collaborations.

Moses Mololekwa and the loss of “new” South African innocence

Recently, I’ve found myself listening to more and more South African Jazz. In particular, I’ve been gravitating towards the late pianist and producer, Moses Taiwa Mololekwa. Now, I must admit that my appreciation for Mololekwa’s music did not come about immediately and I fully acknowledge that his music is not for everyone (especially his inaccurately-labeled ‘fusion’ work), but there is certainly something magical and profoundly important about his work.

Recently, I’ve found myself listening to more and more South African Jazz. In particular, I’ve been gravitating towards the late pianist and producer, Moses Taiwa Mololekwa. Now, I must admit that my appreciation for Mololekwa’s music did not come about immediately and I fully acknowledge that his music is not for everyone (especially his inaccurately-labeled ‘fusion’ work), but there is certainly something magical and profoundly important about his work.

The reason I chose to write about this now is that last Wednesday marked the twelve-year anniversary of Moses Taiwa Mololekwa’s death at the age of 27. On the morning of February 13, 2001, Moses was found hanged next to his wife, who had evidently been strangled, in their office. The circumstances of their deaths are troubling, to say the least, yet this should not obfuscate the significance of Mololekwa’s contribution to South Africa’s already impressive musical legacy.

Predominantly active in the 90s, Moses Molelekwa’s music fused an eclectic mix of influences such as Thelonious Monk, Herbie Hancock, and Bheki Mseleku, among others. His compositions contain references to genres as varied as hip-hop, jungle, kwaito (in fact he produced a number of tracks for the legendary kwaito group, TKZee), and perhaps most notably, marabi. His ability to play around with and recontextualize marabi grooves was nothing short of spectacular and as such, his music should be considered the archetype or standard against which all bubblegum and crossover production and instrumental arrangement of the time should be compared. This is true more for albums like Wa Mpona and Genes and Spirits, than for his comparatively straightforward (yet equally brilliant) Finding One’s Self and Darkness Pass.

For many of those who listen to the former two albums today, the music may come across as rather kitsch. However, the sound Mololekwa crafted on albums like Wa Mpona and Genes and Spirits must be understood within a larger context. The particular moment in South African history in which Taiwa made his music was one of excitement and celebration, as the apartheid era officially ended and the popularity of the ‘new South Africa’ rhetoric reached its peak. From a musical standpoint, this was a moment of immense pride, where musicians were looking inward and trying to create sounds and aesthetics that were uniquely South African, thereby setting themselves apart from the rest of the world (people were attempting to define themselves largely in relation to their ‘South Africanness’). Hence, popular genres like kwaito and crossover emerged as this shift towards prioritizing and performing ‘new South African’ subjectivities picked up steam. To be clear, Mololekwa was not necessarily trying to create music that was uniquely South African in the same way that folks like Johnny Clegg and the Trompies were, but this sentiment and the sonic aesthetics of the time inevitably found their way into his compositions. In many ways, Moses Mololekwa’s music became emblematic of the ‘new South Africa’ and for some, his death signaled the loss of this ‘new South Africa’s’ innocence.

Today, it does not require much of a leap of the imagination to hear Moses’s influence when listening to much of the deep house music being produced by popular South African acts like Black Coffee and Culoe De Song.

Sports Illustrated does Namibia

Jezebel has already gone overboard commenting on and identifying the obvious misogyny and racial stereotyping in Sports Illustrated’s Seven Continents spread. They went through each photo, tagging them with gems such as:

“White person relaxing, a person of color working. Tale as old as time. A non-white person in the service of a white person.”

“Photo cements stereotypes, perpetuates an imbalance in the power dynamic, is reminiscent of centuries of colonialism (and indentured servitude) and serves as a good example of both creating a centrality of whiteness and using “exotic” people as fashion props.”

“Also people are not props.”

Al Jazeera’s done the same. So we won’t waste time re-venting along the same lines. But we should pay special attention to the model representing Africa as a continent. Jezebel’s post points out, about the photoshoot that took place in Namibia:

A black model was also shot in the African country, but when the magazine used the man as a prop, they used a white model, for contrast. Photographing Emily DiDonato against the country’s stunning sands wasn’t enough. A half-naked native makes the shot seem more exotic — even though Namibia is a country with a capital city where there are shopping malls and people, you know, who wear Western clothes.

Whereas many of the other photographs contrast the model’s near-nakedness with the clothed (and othered) bodies of the ‘native’ of the continent, here, both figures — model and Native-as-Prop — are similarly clothed. Here, nakedness of the model is depicted as a “choice” granted modernity, which dictates to us that being part of this great liberal experiment permits women to have access to the same freedoms as men.

Unfortunately, of course, the expression of that supposed freedom, for women, is often limited to exposing the body — as long as it is a much-controlled, reshaped body. Part of how this myth — linking freedom to body-display — is perpetuated is by juxtaposing the modern woman’s ’nakedness by choice’ with (a) an ‘over-clothed’ person from a society that is perceived to be behind the times, and with less access to the freedoms granted to women in the west, or (b) by posing the naked/near-naked woman next to the Edenic Primitive. In Sports Illustrated’s choice for Africa, the latter option worked best: it perpetuates the Africa as location of prelapsarian fantasy story. Here, Africa stands in for the world before the Fall, unspoilt and pristine. After all, the fantasy may not work as well as photo depicted Africa-as-savage (imagine naked model next to child-soldier/brutal African dictator…ah, on second thought, has that already been done?).

Posing this model next to the quintessential image of human ancestry — the primitive ancestor, porting nothing but loincloth and spear, his spare, lean body devoid of the ugly traces of excessive fat (the scourge of modernity) — means we can also project our fantasy of return to that fat-free, supposedly simpler time, when we were not tainted by the miseries of our industrialised state, one that we nonetheless would want to give up. Because the model’s facial features and skin are supple and youthful — while her ‘primitive’ companion’s face is marked by the stamp of sun, dry air and general harsh environment — she appears markedly privileged, different. The resulting effect of the juxtaposition is a deep contrast between where we came from, and how far we’ve come. This game is still about us saying we, with our access to Sports Illustrated, are better off, and better evolved.

The New York Times Global View blog gave its gratuitous attention to the outrage, too, ending its post by listing “the sighs of despair at the politically correct nature of the debate”:

from someone named Pete, one of thousands on Yahoo’s Shine site: “They are not ‘minorities’ when they are in their own country. What a bunch of P.C. dopes we have here in the U.S.”

John S: “Wow, some people need to lighten up. I see pictures of pretty girls in bathing suits. I give it about 1 second and no deeper thought. I spend no time analyzing the background scenery, people or not.”

Jamba went for a funny one, noting: “There are other people in the photos? I guess my eyes were fixated elsewhere.”

Pete: thank you. But we might point out to John S that his thoughts, despite him, may be deeper than him. Hate to bring up Freud, but didn’t the man point out the relevance of the subconscious, and how it reads certain messages while one’s eyes are riveted elsewhere, and then affect our thoughts in ways we may never suspect? The only way to salvage the repetitive Native-as-Prop trope would be to write a parody, emphasising the imagined aspirations of the Other, as a model, individual, and a representative? What if the spear-porting “San” man was vain, club-going Derek Zoolander? Or better yet, someone might attempt a “prequel” to Sports Illustrated’s latest idiotic spread, à la Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea: rather than service the subjectivity and personal growth of Mr. Rochester/Emily DiDonato/’readers’ of Sports Illustrated, San Zoolander takes on the duty of moving to the foreground of the image, re-educating the reader about his own complex aspirations, despite his somewhat limited options.

When Kim Kardashian came to Lagos and “419ed the 419ers”

Post by Jeremy Weate*

Eko Hotel, Victoria Island: the scene of so many expensive misdemeanours in the past, did its best not to disappoint. Kim Kardashian (pictured sailing into the salubrious Murtala Muhammed International Airport) was billed to “co-host” an event with R’n'B crooner Darey Art-Alade in honour of “Love..Like a Movie”. In other words, it was a “Vals” thing. Lagos being familiar to the metallurgy of snobbery, this involved platinum ticket holders being invited to an exclusive pre-dinner event with her K-ness. Pseudo-ogas lower down the corporate food chain only got to see the show.

I was just over a thousand miles away from the action in Freetown, watching my Twitter timeline cascade with commentary as the evening unfolded. Tweets purred with pleasure at the acrobatics segment, and at the godly qualities of Waje’s voice. There was a sense that in production values and packaging, Lagos had outblinged itself.

And then Ms Kardashian appeared, said, “hey Naija” and vamoosed. The rumour was that she’d been paid 500,000 Benjamins for the honour of mixing with the petro-class. She arrived on Saturday evening (on Air France), and left within twenty-four hours (someone Instagrammed her back at MMIA). Prole class tickets were apparently N100,000 ($640), although quite a few got in gratis on the guest list.

The Lagos elite blows money at puffery, while most of Nigeria suffers. It’s the same as it ever was. I recall Carlos Moore railing against the Gowon era on his trip to Nigeria a couple of years ago – how Lagosians were partying while bodies were lying unburied in the street. Gowon was famous at the time for saying that the problem in Nigeria was not money, but how to spend it.

Reflecting a little on the unfolding disappointment in Lagos, I couldn’t help but think that the narrow slice of KK the audience were granted reflects a cargo cult/import economy/colo-mentality, that dresses its shame in dandified arrogance. Last year, Hugh Masekela played the Motor Boat club. I was lucky to be there (I think I paid 15,000 naira for the privilege). People chatted noisily throughout. The great jazzman could hardly hide his disgust.

There’s something Dubai-esque about the children of the Islands. Pampered lives told in British public school brogues. Bubbles of air-conditioned comfort, which we might think of these days as “Lekki blindness”. Fela is long since dead, but his words rework themselves in the present with ease.

As the disgruntled tweets flowed out on my timeline, I thought of Special K, comfy in her jimjams, the plane rising gradually above the Atlantic, safe from all Lagos harm, smiling to herself that she’d actually 419’d the 419ers. And I went to bed with one final thought: oil turns all who touch it completely insane.

* You can follow Jeremy Weate on Twitter.

February 15, 2013

Weekend Music Break

Friday/Weekend Bonus Music Breaks got side-tracked a bit lately because of the Afcon fever. Good times were had by all. Let’s pick up the thread though. Here are 10 music videos you might have missed over the past weeks. Burkina-American Ismael Sankara (remember Mikko’s write-up about Ismael’s surname and possible affiliations) released a new video: above. Tyler the Creator-Yonkers-style, Elom 20nce’s masks imagery, swag lyrics, stir, et voilà. Neat beats. More diaspora music:

Nina Miskina (who was part of the Brussels-based Congolese Héritage project) seems to have put her theatre acting on the back burner to focus on her musical career. Here’s a first video for ‘Un verre de plus’, taken from her debut EP:

Another Belgian-Congolese artist is Coely. When footballer-and-aspiring-record-label-manager Vincent Kompany says we should like her, we’ll like her:

There’s a high-profile (and heavily sponsored) electronic music festival happening in Cape Town, South Africa this weekend. Surprised not to find good old synth-duo Tannhäuser Gate on the bill:

Originally from Bangui, Central African Republic, Idylle Mamba now lives and works in Cameroon. This new video blends all kinds of styles:

Also repping Cameroon (via the Netherlands) is Ntjam Rosie. From the video below, it looks like she’s taking a break from her previous “soul jazz” work:

More funky rock courtesy of the Senegalese Daara J Family (they’ve been around for a while), vintage dancing and ‘celebrating’:

This acoustic session by Gasandji and her band made me sit up:

Cuban jazz pianist Omar Sosa has a new record out. He presented and talked about it at WNYC radio studios recently: a tribute to Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue, while channelling the “Eggun” spirits:

And finally, this portrait by Vincent Moon of muezzin Saeed Rifai Ali Khaled in Cairo. Watch it:

Cape Town goes Electronic

This weekend marks the 2nd year of the Cape Town Electronic Music Festival, an event that seeks to present the “multi facets of South Africa’s electronic music scene” with a weekend of performances and workshops. Judging from the promo video (below), the festival seems to be punting diversity and breaking down racial barriers under the umbrella of electronic music, which for Cape Town is generally not the most diverse crowd. However, the organizers have thankfully leaned towards a broader understanding of electronic music.

The international headline artist for this year is Richie Hawtin, a British-Canadian electronic musician and DJ who apparently spends a lot of time in Ibiza. He was also one of the major players in the Detroit techno movement (as I found out by googling him). Personally, that’s not really my thing. I am more excited about the local headliners, specifically Shangaan Electro, the high speed dance music genre which now seems to have been to reduced to one group, led by the inimitable kingpin Nozinja (the father of Shangaan Electro). Perhaps the naming of the group as Shangaan Electro is to draw a crowd who know the genre but are unfamiliar with Nozinja himself. Although who could forget this guy?

What’s remarkable about Shangaan electro is how Nozinja took a relatively obscure regional dance scene and turned it into a hip global dance genre, gobbled up by the likes of Dazed and Confused and The Fader, tearing up dancefloors in Europe and the US. As far as I can tell, this is also the first appearance of Shangaan Electro in Cape Town, so it’s a performance not to be missed.

Other notable local acts are Black Coffee (also having success with international audiences), electro hip hop don Sibot, drum ‘n bass darling Niskerone, and Card on Spokes, the electronic alter ego of Shane Cooper (Standard Bank’s Young Jazz Artist of the Year). Also, hip-hop pioneer Ready D will be doing a set with Cape rap upstart Youngsta (as seen in the video wearing shades indoors). It’s a good line-up, but hopefully next year the organizers will begin to extend the invite to electronic artists from the rest of the continent. One strong suggestion: Kenya’s Just a Band.

Why is South Africa such a violent society

Post by Palesa Mazamisa*

The heinous, brutal rape and subsequent slaughtering of Anene Booysen in South Africa’s Western Cape province has brought into the open, once again, the miry underbelly of our rainbow nation. At the heart of violence that Anene was subjected to, lies a bigger issue that South Africans wilfully shunt and ignore. This issue is our Achilles heel. It is what has our nation wondering at the gruesome nature of the violence committed against Anene with our mouths agape, spit dripping from our lips, trying to figure out what makes South Africa such a violent society.

In our post-apartheid state it is fashionable to reduce apartheid to a simple administrative error that has since been corrected. This flippant attitude to our past has resulted in a perception being pushed that the real problem facing a democratic South Africa is the vicious reverse racism that places white South Africans under a type of oppression and threat not yet seen or experienced anywhere or at any time in history.

This flippant attitude further suggests that white people have done their share for this country by voting ‘yes’ in the 1992 referendum, even allowing blacks on their teams in rugby and cricket, and referring to themselves as Africans–for heaven’s sake, only Nelson Mandela, the Dalai Lama and the Kardashians have done more for humanity. When will the consistent and annoying references and allusions to apartheid and racism end already?

It is unfortunate that the same flippant attitude is a prevailing one, as it leads us to maintain a façade of unity. With the pretensions of a rainbow nation firmly in place, we fail to reflect with honesty on the state of our nation. A nation with a history marked by brutal and persistent violence sustained over centuries.

Cultural writer Bongani Madondo expressed it succinctly when he wagered (on Facebook) that Anene’s hideous rape and murder can be traced to South Africa’s recent excessive violent past, in particular between 1959 to 1992. Over three and a half decades, he argues, excessive violence ripped out the bowels of black families, children dancing over burning bodies of their neighbours, dogs feasting on bodies of black men, parcel bombs ripping matchbox homes apart, rape by the white system, rape by the capitalist system, rape, looting and handcuffing by police and their askaris, black brother against black brother in the Vaal, East Rand, Johannesburg Central, extreme poverty, incest, and three revolutions crushed by merciless state violence: 1960, 1976 and 1985-1990. Plus the excessive violence of the liberation parties in exile; remember Mkatashinga 1984 in Angola.

It is this reality of the violent nature of oppression that we seek to sweep under the carpet.

We don’t want to entertain that an examination of the violence in South Africa can’t be accomplished outside the context of colonisation and apartheid. We can’t discount the context of institutional and structural racism and the brutal subjugation of black people. Yet it is what we continue to do. We have in our country developed a disturbing trend that is in itself a form of violence, namely the suppression of black experiences of apartheid, unless such an experience is an expression of the greatness of the apartheid system. For is it not that without colonialism and apartheid, black people would still be scratching their bottoms trying to figure out if up is down or down is up.

Those who try to place the challenges we face as society in its proper context, are hurled with insults and abuse, and reminded that going back to the past is not helping the country move forward. Only last week, Redi Direko, a radio talk host of a popular Gauteng-based station, Radio 702, spoke of the horrors of apartheid and was showered with a flurry of messages to stop ‘exaggerating’ what happened during those ‘dark days’, as it is called, flippantly. Clearly, in our rainbow nation, violence is the answer, whether physical, verbal or emotional.

If we are to honour the life of Anene and other victims of violence, we will have to confront and be truthful about the many sources of violence plaguing this country. Read here, here and here on violence and power in South Africa. This will mean revisiting our past so that we may understand how the socialisation and normalisation of violence came to characterise the South Africa we live in today. We will not find our answers in the nature and structure of violence in India. We will find those answers in our own backyard.

* Writer/playwright Palesa Mazamisa dabbles in the art of cynicism, as well as skepticism, which she believes are necessary to survive the South African media sphere. In her spare time she is known to bake award-wining German cheesecakes.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers