Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 489

February 21, 2013

In Memory of Anene Booysen

The road that leads to Bredasdorp, a small town about 180 km from Cape Town, meanders through barren fields shaved of the wheat they once nursed to maturity. The sheep sidle through protruding stalks, stomaching the lack of greener pastures. The resilient blue gums – the only trees that seem, ironically, to break the dullness of the Cape Agulhas region – lay their leaves to roast in the harsh sun. A “Beware of Children” sign stands at the entrance of Bredasdorp with its 15,000 inhabitants.

That Sunday afternoon, the streets are empty, as is often the case in small South African rural towns. Shops and museums are closed. Some of the restaurants are still serving lunch and a few people eat quietly at a cosy terrace, contemplating space and time. Five hundred metres away from the main street, past the tall cement silos full of the grain harvested this season, a memorial service for Anene Booysen is underway at the community hall named for Nelson Mandela. In Bastiaan Street, opposite the hall, people are watching the beginning of the service from the gardens of their RDP government houses. Leaning against their fences, they look at other Bredasdorp residents sitting under the white tent erected next to the hall for the occasion. Women mostly, from the community.

Outside the hall, a woman surrounded by teenagers is interviewed by the local TV. The fast flow of her response to the journalist attests to her anger: “We are human beings, stop raping us, we deserve to be safe!” Angry but calm. Under the tent, about 500 people are also waiting quietly for the service to start. Women sit patiently under their colourful hats, some raise perfectly crafted posters asking to “stop the violence and abuse against women.” Children run between the rows of seats, two of them get smacked for pushing an old lady.

Outside the hall, a woman surrounded by teenagers is interviewed by the local TV. The fast flow of her response to the journalist attests to her anger: “We are human beings, stop raping us, we deserve to be safe!” Angry but calm. Under the tent, about 500 people are also waiting quietly for the service to start. Women sit patiently under their colourful hats, some raise perfectly crafted posters asking to “stop the violence and abuse against women.” Children run between the rows of seats, two of them get smacked for pushing an old lady.

Bredasdorp’s ANC mayor, Richard Mitchell, takes the stage: “The world now knows where lies Bredasdorp on the African map. And the incident, where Anene was murdered, is the cause for the interest of the world in Bredasdorp.”

Inside the hall is Corlia Olivier, Anene’s foster mother, sitting next to her mother and brother. She listens, composed. A woman stands at the back of the crowd and whispers: “This must end. My daughter was raped, my granddaughter was also raped when she was 4 months old. My daughter-in-law was raped. How do you cope with this? My brother didn’t when his wife was raped. He committed suicide. Sorry to lay all this on you but we must speak out!”

“And I want to start with our members from national parliament, continues Mayor Mitchell. Members from provincial parliament who are present today, mayors from surrounding municipalities, councillors, and even a delegation for the commission for gender equality. Representatives from the unions – Cosatu, also representatives of the SACP – the communist party, the ANC Women’s League, the ANCYL. Members of the NEC of the ANC, members from the opposition party – the DA, and then we also have the veteran association Umkhonto weSizwe and as I said all other protocols observed, ladies and gentlemen, and… and mostly our communities.”

A woman carrying a baby tries to enter the hall from the side door. A veteran of Umkhonto weSizwe (the ANC’s now-disbanded armed wing), dressed in military kaki uniform, brushes her off. She looks at him, offended, while a man wearing a shirt with a machine gun drawn on the back and displaying the “Umshini wam” (bring me my machine gun) slogan made famous by the country’s president, Jacob Zuma, is left to stand in the doorway.

“Many politicians have requested to give a message during this memorial, we will allow 3 minutes for each of them”, warns the master of ceremonies.

“Many politicians have requested to give a message during this memorial, we will allow 3 minutes for each of them”, warns the master of ceremonies.

Simphiwe Thobela, a local ANC Youth League representative, walks to the microphone after a short speech by a local member of the Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu) and starts his diatribe against rape :

“Mayors, ANC members, comrades, I won’t be long but I’m gonna steal a minute from Cosatu because they didn’t use their three minutes”:

-Viva ANC!

-Viva

-Viva Women’s league!

-Viva

-Amandla!

-Awethu

For two hours, the SAPC, the ANC Women’s League, the DA, Cosatu and other official representatives take the microphone, one after the other. Between speeches that quickly denounce the rape crisis, political stumping slips in.

An agitated man wearing an ANC shirt and a Che Guevara beret walks up the aisles asking the sleepy crowd to clap their hands for a song is about to start. The “Power of your Love” eventually gets the crowd going. The agitated man looks more content, and walks to a group of singing women wearing ANC t-shirts. With a broad grin, he hugs his comrades and photographs them. Some still-clapping residents look on, puzzled.

It is now Cosatu General secretary Tony Ehrenreich’s turn to speak. Ahead of the event, he had warned that “this crisis is much bigger than our political division.” After greeting Anene’s family, he goes on: “I come here as Cosatu, it is a crisis we need to respond to as an organisation.” In the front row of the crowd, sitting under the tent, a man and a woman stand up and raise their fists to punctuate the political punch lines.“Enough is enough” – “an injury to one is an injury to all” – “We must get involved, we must tell the abusers that no longer will they abuse our communities.”

Lynne Brown, former ANC Premier of the Western Cape, calls out to the crowd: “The boys who have been arrested – they’re not anyone else’s child. They’re your child and my child. Remember that we will be gone tonight, in fact this afternoon, and you will stay here alone.”

After hugging Anene’s mother, the Western Cape ANC provincial leader Marius Fransman closes the political monologue : “Dan Plato (DA politician and now Minister for Community Safety in the Western Cape) is a criminal, he used taxpayers’ money to throw a party for gangsters. You can’t give money to gangsters and think it would solve the problem.”

So this is how the people of Bredasdorp gathered on a quiet Sunday afternoon to remember the life and times of AneneBooysen. Anene’s mother and her family were there. Her neighbours were there. The people of Bredasdorp who knew her and grieve her today were there. They alone know who AneneBooysen was. They alone know what her aspirations were.

But political agendas walled them up in silence. They have been told what their problems are – “drugs and alcohol are to be blamed”. They were made to listen to the ANC NEC, the Women’s League, the ANCYL, the Communist Party, the DA. The councillors and the delegations. The Amandlas and vivas. All other protocols observed in the memory of Anene Booysen.

Finally, the politicians dropped a memorandum at the local police station, packed up and left. Lynne Brown probably didn’t realise how right she was: the community of Bredasdorp did sleep alone that night.

* Mélinda Fantou is a photojournalist based in Cape Town.

New African films to watch, N°17

Yes, we’ve been slacking a bit with the weekly round-ups of new films (whether completed, almost ready or still in their early production stages) this year. Let’s correct that. First one (trailer above) is a documentary about legendary Cape Verdean pianist Epifania Évora (also known as Dona Tututa). The film is directed by João Alves da Veiga and had its première in January.

Then there is Kwaku Ananse, Akosua Adoma Owusu’s short film which, she writes, is “an effort to preserve a fable my father passed on to me.” The film draws upon Ghanaian mythology, “combining semi-autobiographical elements with the tale of Kwaku Ananse, a trickster in West African stories who appears as both spider and man.” Don’t underestimate what an Indiegogo campaign can do. The film was screened at the Berlinale this month.

I Love Democracy: Tunisia is part of a TV documentary series produced by Fabrice Gardel and Franck Guérin, originally intended for the European Arte broadcaster (whose website also has more details). The images and interviews were recorded just after the fall of Ben Ali:

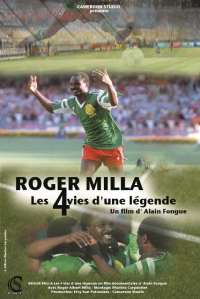

Roger Milla: The 4 Lives of a Legend (“les 4 vies d’une Légende”) is a documentary by Alain Fongue. You have to wonder why it took so long for someone to make a film about the legendary football player from Cameroon, or did I miss some? (Of course this moment is also how I got to know him.) The distribution of the film runs via Patou Films. Couldn’t find a trailer for the film yet.

Roger Milla: The 4 Lives of a Legend (“les 4 vies d’une Légende”) is a documentary by Alain Fongue. You have to wonder why it took so long for someone to make a film about the legendary football player from Cameroon, or did I miss some? (Of course this moment is also how I got to know him.) The distribution of the film runs via Patou Films. Couldn’t find a trailer for the film yet.

And Goodbye Morocco came out in local theatres here this week. The first reviews are promising. In those reviews, I read French-Algerian director Nadir Moknèche gets compared to Pedro Almodóvar on a regular basis. Add to that the “film noir” tag, and we’re already warmed to seeing the Tangier-based film. Review to follow soon!

* True, we used to feature 10 a week but for oversight’s sake 5 will do the trick, we hope.

Vincent Moon’s Portraits of Ethiopian Music

Post by Addis Rumble *

“Ethiopia is an island,” Vincent Moon explains. The French filmmaker has been on the road for four years now travelling and filming music and spiritual rituals across the globe and releasing them through his Petites Planètes label. 2012 saw him spending three months in Ethiopia exploring and recording Easter in Gonder and the sounds of Merkato among other things – either alone or with sound artist Jacob Kirkegaard (who we recently interviewed). We caught up with Vincent after he left Ethiopia and asked him to reflect on the struggles and rewards of filming in the country, his explorations of sacred music and trance in Ethiopia and how his nomadic life is transforming him into a chameleon.

You have been traveling around the world documenting musicians for a few years now. What made you come to Ethiopia?

It’s a decision I took one day after exchanging mails with Danish fellow artists Jacob Kirkegaard and Malene Nielsen, who already knew the country. They wanted to collaborate on a project made there, I jumped on the idea as I dreamed for a long time of Ethiopia, and I decided to go. When I take a decision I usually never come back on it, so it was stuck in my mind. In the end Malene didn’t come and we made a very different project with Jacob but life took us on this path.

How does your work typically take form when coming to a new country? Where do you start and do you have any common themes that you explore across the countries you are visiting?

Usually I travel with a few contacts in a country, some people who have been in touch with me maybe in the past years (showing my films, or just exchanging ideas about music and cinema) and with whom I kept in touch and proposed them to produce some local films in their own city, country. I never work with professionals and I am always more inclined towards people who have never done anything like this – same for sound recording actually, I tend to ask local people to record the sounds of a shooting and I explain them on the spot what to do with it. So to collaborate with Jacob was definitely a very different challenge.

But as for me coming to Ethiopia in the first place, this time I had almost no contacts at all in the country and I thought maybe a bit too optimistically that I would find them there. Well, things went a bit more complicated! I arrived in the country two months before Jacob and went to explore many parts, the north, the east, the south. And I ran into so many problems it was almost like a joke. I really had a terrible time for a while there, until things started to get more harmonized. I didn’t have many plans beforehand anyway in terms of recording, all I knew was that, as I was familiar obviously with the Ethiopiques releases made by Falceto, I wanted to avoid anything related to it and dig into the unknown for me. Apart from Alemu Aga with whom we made a very nice recording (and God how wonderful this man is, it was a light in my trip), all the other ‘music’ I recorded there, I had no idea they were existing just a few weeks ago. There was maybe a common theme, which is something I am researching in all my travels now – exploring the sacred music, and relationships of the people with any religious rituals.

What was your approach to filming in Ethiopia? How much of your work done in Ethiopia was planned beforehand, and how much of it was improvised?

As said before, I don’t like to plan much as I give myself a lot of time in the places I visit. In Ethiopia, I didn’t plan anything specific, and I found all my subjects there on the spot. This is apart from Alemu Aga maybe, whose record I loved so much and which sounded from another planet, so I contacted him as soon as I arrived and proposed him a film – I waited to the end of my trip and the coming of Jacob to make it sound fantastic:

The Gamo people from Addis I met early on and planned a recording later, again waiting for Jacob to arrive to make it better. While hanging out at the Taitu Hotel and talking with some funny explorers there (I love Taitu for the incredible characters you bump into), I met some people who told me about the Zar practices still happening in the north and about the exorcism rituals in Addis Ababa. It’s through Japanese ethnographer Itsushi Kawasse that I heard about the Lalibalocc tradition. I planned to visit Gondar during Easter and wanted to make a recording of the ceremony, which I did in this magnificent Debre Berhan Selassie church. I went to Harar with the intention of reaching the Zikris rituals and I met there with Amir Redwan who opened the doors of its ‘nabi gal’ for me. And it’s Jacob Kirkegaard who told me about the fabulous sounds we could record in Merkato. All in all, you could say it was often very much improvised on the spot, with some intense researches made the days before in the same area.

How is filming in Ethiopia different from of some of your other recent destinations?

To put it simply, so much more complicated! Ah, I laugh about it now but at the time, it was driving me crazy. Since then I have been traveling through Ukraine and the North Caucasus of Russia recording ancient music, and it’s been such a contrast, so easy on everything, that I looked back to those three months spent in Ethiopia with a very different feeling. In Ethiopia, people didn’t care at all about being recorded. Most of the musicians I ran into were so pretentious and asked for so much money to perform (I never paid any musicians before for the recordings, so the contrast was a bit tough) that I was feeling very awkward – I didn’t have any money to give them, being completely broke myself (bad idea, you can travel being broke in many places around the world, but not in Ethiopia), and the simple fact of paying someone to perform was something I avoided always to keep a ‘true’ relationship to the musicians. Was I wrong? Maybe. So I paid most of the people I filmed in Ethiopia. Did they play better because of the money? I don’t think so. Did it create a weird relationship on my side? Most of the time, but it’s my own fault. I remember this quote from Michel Leiris: “Africa does not need me.” Well, Ethiopia didn’t need me!

For outsiders coming to Ethiopia the first time, Ethiopia often seems like a unique, closed and secretive society with strong traditions difficult to understand and interpret. What was your experience like? Could you get access to the subjects, places, and ideas you wanted to work with?

Ethiopia is an island in my mind, that’s how I see the country – being so cut off from its neighbors because of its mountainous land, developing a unique culture in Africa and so on… We know the story now. It’s a fascinating place, incredibly beautiful and with such unique traditions, I was quite blown away. I didn’t find it hard to access at all, people being very open although complicated to deal with sometimes. As long as you keep in mind that spirituality here still has a strong meaning, you can navigate easily and spend a fabulous time immersed in the culture. As I said, my only difficulty in terms of shooting was that almost no musicians was interested in what I wanted to do. I completely understand it although I suffered a lot from it. But you know… the eternal faranji paradox.

Your films from Ethiopia are quite an eclectic mix – from the sounds of Merkato via the begegna of Alemu Aga to the polyphonic singing of the Gamo and Dorze tribes etc. Do you have any favorites among your films done in Ethiopia?

Maybe two favorites. The most beautiful experience shooting was the Fasika (Easter) night in Gonder. I was alone and wanted to access the church for the ritual, I tried to get some contacts in town the days before but all of them were so unreliable that I dropped them and just went by myself, late afternoon. I was there before anybody, and little by little the church started to get filled with priests and so on. All of them were surprised to see me and asked me what I was doing, I just said I was curious, that I was a catholic who wanted to switch to orthodoxy. Little by little over four hours I gained their confidence by looking and smiling at each of them and then at one moment of the night I took my camera out of my bag. Nobody then asked me what I was doing, if I was making a film or anything like that. They just took me with them until the end of the night. It was a very powerful experience, and a very beautiful film although anybody who knows about the church in Ethiopia will probably look at it without any interest:

The second favorite recording was with Tilahun, the Lalibela singer. I got his contact through Kawasse, I called him and he asked for so much money that we couldn’t find an agreement. Two days later he calls me back and says he is in Addis, ready to record. I ask him to share a coffee with me, and bargain with him, smashing the table, saying this will be one of the most important moment of our lives. He is a beautiful soul, very quiet and he gets my point even though I used the aggressive method. He leaves and I realize I even forgot to ask him to sing! I don’t know at all how good he is. Very early next morning we are with Jacob in the dark streets of Addis, following this tall shadow going from one house to another, wondering why the hell did we woke up so early. He starts finally to sing in front of a door, his voice reaches such heights that we all shake. Maybe the most beautiful voice I ever recorded.

Several of your films from Ethiopia focus on the mix of music, religion and rituals, e.g. the Orthodox Easter ceremony in Gonder, the sufism tradition in Harar and exorcism rituals at Entoto Maryam. Was this a specific objective from your side or the result of Ethiopia being a very religious society?

I enjoyed very much Ethiopia being a strong spiritual place, but my choice to make such recordings already started in my recent researches on religious rituals, on relationships between music, trance and so on. I already made some films on Zar ceremony in Cairo (although there it’s a quite different story), filmed various sufi rituals in Indonesia, recorded trance rituals amongst afro-brazilian religions, made many experiences with shamanism and so on in Colombia or the Philippines. It’s a personal spiritual quest which is maybe my main objective in life nowadays.

When the conversation turns to Ethiopia, most non-Ethiopians still think of famine and long-distance runners. What is the first thing that comes to your mind?

Nowadays when I think back I remember a country so unique in its culture that it has no equivalent in the world. And I really wish I can go back there soon, and explore more of the southern part of it, the richness of its animism and so on. Also comes back to mind this extreme tension between a culture so rich, a nature so beautiful, and an economy so poor that it really made you seriously question the way we want things to evolve in such a place.

What started your move from doing the Take Away Shows of indie musicians (and others) to recording traditional music across the globe through the Petites Planètes series?

Curiosity, to put it simply. I can’t stop moving and doing something else, it’s more a sickness than anything else. 4 years ago I was still in Paris, still recording indie music, and I ended up homeless by accident and started to travel, invited in various places around the world. At first I continued to record indie music, in Chile, in Argentina, but then little by little I was more and more drawn into traditional music, ancient singings, sacred music and so on. It’s a very natural move I think for someone who travels, you leave your culture little by little, not from one day to another, and start to adopt other cultures for a short period of time. You become a sort of chameleon, your personality changes everyday and life appears as a game, a new adventure all the time.

And what keeps you motivated now after years on the road – the need to document and archive musical heritage, eagerness to explore the world, restless?

A mix of all this, but especially the feeling of being younger and younger everyday living such a life. There is no tomorrow, just the excitement of being with people you didn’t know anything about 5 minutes before and having an intense experience.

* This is a slightly edited version of an interview originally published by Addis Rumble. We’ve been long-time followers and admirers of Vincent Moon’s work (and featured some of it here on the blog before, notably his collaboration with Femi Kuti, Brazilian artists and Egyptian muezzin Saeed Khaled) so we’re grateful Addis Rumble allowed us to cross-post it. More of Vincent Moon’s films from Ethiopia are available here, here or here.

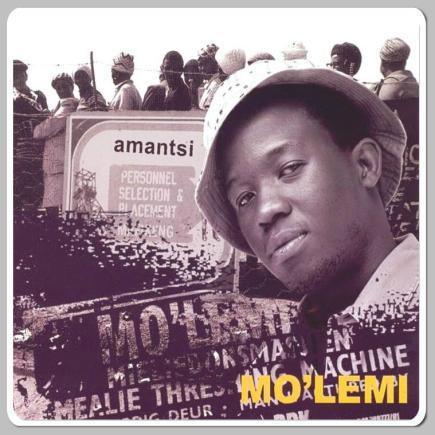

South African Hip-Hop needs more artists like Molemi

A harp hard-panned to either side of the speakers constantly loops while a flute sample pulsates in lock-step with the reverb-drenched hi-hats sounding off on every fourth beat. The drums kick in; snare; bassline. Suddenly the listener is placed squarely in Mo’Molemi’s (real name Molemi Morule) territory, arguably one of the most revolutionary rappers in South Africa. I got introduced to Molemi (or Mr. Mo as he’s sometimes known), through a hidden song on HHP’s YBA2NW album. HHP is one of the most recognisable entertainers in South Africa, having been catapulted to fame by two things: his fourth album, “O Mang?” (who are you?/what are your roots?) with its lead single “Harambe”, as well as winning a dance competition which was beamed to television sets across South Africa via the country’s SABC2 channel.

Molemi, on the other hand, has charted his own course with varying degrees of commercial success since his formative days as a member of the group Morafe. What he has not done though, and I stand corrected, is to compromise on his message; he has not given in to commercial pressure; he has not succumbed to the trappings of fame. Mr. Mo’s politically-charged content is as incisive on “Lemphorwana” off of his second album “Motsamai” as it was on “Blu Collar” from a collection of songs which got leaked in the lead-up to his debut, “Amantsi”. In “Blu collar”, he raps

Bo-ausi ba di-kichini bo kareng bo botlhe le ma-kontraka, ke re pop the blue collar now / bo-rametlakase, di-plaas joppie le bo-mme ba fielang straata, amandla, come on, ha! (“ladies who clean kitchens, including contract workers, I say pop the blue collar now / electricians, farm workers and ladies who sweep the streets, more power to you, come on!”)

In essence, the song is a rallying call for all the blue collar workers – street sweepers, kitchen maids, contract workers – across the South African landscape to come together in unison towards one single cause. What that cause is, however, is not made explicit. Perhaps Molemi is not a one-dimensional rapper, opting for multi-faceted, non-bigoted, and informed views on any issue he tackles. While songs like “Blu collar” and “Vokaf” are aimed at addressing South Africa’s social condition at large, there are still more, such as “Apulaene” and “Mmabanyana” which further endeavour to invite the listener into the world of his people, the Batswana of Botswana – the different tribes, their chiefs, and their customs and rituals.

Hip-hop in South Africa needs more artists like Molemi – a farmer (his name translates to ‘one who plants’) who is also a very talented rapper. A legionnaire, a lone rider in the canon of Motswako – a genre increasingly associated with care-free, party-friendly music. In an interview snippet with Leslie Kasumba which can be found on his first album, Molemi said the following after being asked what he feels that he is bringing to hip-hop:

[I bring] stories that can provoke debates, not nice songs. I’m bringing in things that the government will ask ‘what’s this hip-hop?’ Hence ‘Blu Collar’, because ‘Blu Collar’ will talk about the experience of people who work the hardest but earn the least; those that freedom is not really reaching that much. I’m one of them! Not just talking to them from a distance, but sharing the stories from within. There’s a certain section of society in general that we’re not doing enough to reach out to. Capitalism is having a very negative effect on the general people, the people at the bottom level, because they’re not benefitting anything from what’s supposed to be ours.

The Book of Marikana

Guest Post by Christopher Webb

The day after the police shot 34 miners at Marikana a small group gathered outside the gates of parliament in Cape Town. Barely 100 people, holding signs calling for answers and justice, we marched to the police station on Buitenkant, across from the District Six Museum, to deliver a petition calling for the arrest of Nathi Mthethwa, National Chief of Police. The march, for South African standards, was small and made stranger by the fact that few joined us as we passed the rush-hour crowds outside Cape Town station. Commuters looked away as they rushed to their taxis. Later that day I went to a dinner in the very-white, very-gated southern suburbs where the massacre was discussed as if it were a police briefing: a violent mob of uneducated thugs, fuelled by muti and brandishing all manner of weaponry had attacked police who responded with necessary force. A local ANC activist expressed similar sentiments to me a few days later, as he urged me not to place blame until truth had been established.

Even at that time, it seemed fairly self-evident whom to blame. Police, likely in collusion with some level of Lonmin management and possibly state officials, had called for police reinforcements following skirmishes on mine property and the refusal of miners to return to work. Video footage of the incident showed row upon row of police armed with automatic rifles peppering miners with repeated volleys as they scrambled through the veldt. The media, however, gave voice to a very different story: One of inter-union spats resulting in revenge-killings between AMCU and NUM, and, again, muti-crazed strikers hurtling spears at police. Marikana: A View from the Mountain and a Case to Answer is a necessary corrective to these accounts, giving voice to those who witnessed the massacre first hand and telling the stories of those who live with the everyday violence and poverty endemic to South African mining.

Edited by a group of Johannesburg-based academics, activists and community researchers the book will likely be the first of many dealing with the massacre and its aftermath. While it presents a much-needed alternative narrative to mainstream accounts, it ultimately fails to break any new ground or reveal facts that haven’t already been explored to some degree by reporters or through testimony at the Farlam inquiry. It proves, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that NUM, the police and Lonmin management are to blame for the slaughter. But this has already been well established by investigative coverage—most notably by South African online publication, The Daily Maverick, and foreign media outlets like Channel 4. In this sense it is something of a public shaming of mainstream South African journalists. This is not to dismiss the book’s value. The authors state quite clearly that it “can only provide a starting point for future scholarship.”

The book’s narrative weaves between the editorial voice of its writers and researchers and the first-person accounts of the massacre by strikers, their wives, and union officials. Maps of the area where the massacre took place provide much-needed illustrations of police manoeuvres in the days leading up the massacre, and validate accounts of police deliberately trapping workers. This is followed by an account of the researchers encounters with workers and their families in Marikana, and the process of building relationships of trust over short period of time and in an environment of fear and intimidation. Two researchers describe an encounter with the wife of a worker who demands to know who they are and what they are doing, claiming that people calling themselves researchers had been visiting nearby shacks kidnapping and torturing their husbands. These claims have been substantiated by reports of widespread police torture and intimidation during the Farlam inquiry. Crucially, the researchers attempt to challenge the methods of conventional ‘disinterested’ academic or journalistic research by acknowledging, and foregrounding, the pain, bravery and fear workers experienced in telling their stories. “We hope,” they write, “you can understand the massacre through the lens of the victims, those who continue to mourn the deaths of their loved ones and colleagues.”

Before the interviews with strikers and their families, there is a chronological account of the events leading up to the massacre distilled from interviews with a ‘reference group’ conducted six weeks following the event. The strength of this account lies in its exploration of worker life histories and the social conditions that led them to the shacks of Marikana. While it lacks a detailed account of poverty, it clears up the much-disputed question of mine worker wages: With few exceptions, workers took home between R4000 and R5000 ($450-R550 USD) per month. Although it is clear that workers were not only concerned with pay levels. Rock drill operators (RDOs) were made to do two jobs while only being paid for one. Interviewees also clarify that the demand for R12,500 per month was merely a bargaining chip on the table not a definite demand.

The account of the strike itself from August 9th to the 16th is remarkably consistent from one interview to another: Led by RDOs, workers marched to Lonmin offices to demand a meeting with management in order to discuss their grievances over wages and working conditions. Rebuffed by Lonmin they were told to consult their NUM officials, which they attempted to do the following day. Instead of meeting with them, NUM officials opened fire on the crowd, killing two workers and injuring dozens. Fearing further attacks from NUM the workers headed for ‘the mountain,’ from which they would plan the future of the strike. The following days saw further violence as strikers clashed with police in attempts to prevent scabs from entering the shafts. Between August 14th and 16th the strikers repeatedly requested to meet with Lonmin management in order to discuss their grievances, but management refused to negotiate directly with workers. Pleas from NUM and AMCU officials to leave the mountain and return to work went unheeded. On August 16th the area swelled with police and soldiers. Razor wire was unrolled to prevent strikers from escaping and helicopters hovered over the veldt. From worker testimony, it is clear that what ensued is nothing short of premeditated slaughter, as the majority of those killed were hunted down across the veldt. “People were not killed because they were fighting,” notes one striker, “they were killed while they were running away.”

While workers direct most of their fury at police, it is clear that they view NUM in much the same light. Prior to NUM officials firing on the strikers, workers were already convinced that NUM was not on their side as it had colluded with Lonmin in dismissing militant shaft stewards. According to one worker: “When it comes to worker’s needs, the union [NUM] makes promises but never delivers on them, and we end up losing a lot.” Worker testimony is replete with stories if NUM colluding with management to cover up unsafe working conditions and NUM officials accepting bribes from Lonmin. The decision of workers to carry ‘traditional weapons’ to the mountain was motivated out a fear of continued attacks by NUM officials rather than the police. It is no surprise then that in the wake of Marikana miners from platinum to gold to coal have registered their dissatisfaction with NUM by joining the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU), prompting venomous attacks from NUM and COSATU leadership.

The book concludes with a useful summary by Peter Alexander of the various smokescreens produced by the police, NUM, and the ANC alliance in order to hide their complicity in the massacre. Alexander dissects police claims of ‘self defence,’ referencing the notorious photographs that revealed police officers placing weapons beside bodies and autopsy reports showing strikers were shot in the back. Culpability, he suggests, lies within a ‘triangle of torment,’ which links the police, Lonmin and NUM and arguably extends beyond this to include the ANC and mining capital. While the leadership of SAPS is almost definitely to blame, further research will be required in order to link the incident to Zuma’s office—although Ramaphosa’s emails to Lonmin management indicate that there is much to yet be uncovered.

Perhaps most convincing an explanation is Alexander’s attempt to situate the massacre in the history of South African industrial relations. The mobilization of workers outside of formalized collective bargaining structures represented a threat, not only to industrial peace, but COSATU and NUM’s hegemony among the working class. It also threatens to erode the fragile peace the ANC negotiated with capital in the transition from apartheid. Ultimately the book is vital attempt at rewriting history from below, utilizing the voices of workers themselves. It ultimately poses more questions that answers—not entirely a bad thing—pointing toward future studies and research needed to make sense of the largest state massacre since the Soweto Uprising of 1976.

* Chris Webb is a graduate student at York University, Toronto where he studies South African labor. He is a regular columnist for Canadian Dimension magazine and an editor of Nokoko: Carelton’s African Studies Journal.

February 20, 2013

My Favorite Photographs N°12: Kelebogile Ntladi

The latest image-maker in the “Favorite Photographs” series is South African photographer Kelebogile Ntladi. Based in Johannesburg, Kelebogile uses her images to interrogate gender norms and unapologetically contribute to the establishment of new space for dynamic identities in contemporary South African society. In particular Kelebogile’s work focuses on the idea of androgyny. With an interest in photography encouraged by mentor and friend Zanele Muholi, Kelebogile employs her images as tools for social change. Her bold images exist in the context of a nation that enshrines freedom from sexual orientation-based discrimination in its constitution, but where attitudes and behaviors can prove otherwise.

The latest image-maker in the “Favorite Photographs” series is South African photographer Kelebogile Ntladi. Based in Johannesburg, Kelebogile uses her images to interrogate gender norms and unapologetically contribute to the establishment of new space for dynamic identities in contemporary South African society. In particular Kelebogile’s work focuses on the idea of androgyny. With an interest in photography encouraged by mentor and friend Zanele Muholi, Kelebogile employs her images as tools for social change. Her bold images exist in the context of a nation that enshrines freedom from sexual orientation-based discrimination in its constitution, but where attitudes and behaviors can prove otherwise.

Here, Kelebogile explains the concept behind her images from the series “Split Halves”:

‘Split-Halves’ is commentary on the difficulties that come across towards diverse sexual orientation. This series of portraits focuses on androgynous people living in central Johannesburg. This subject is unique because androgyny is still an unexplored, taboo topic in South Africa. I am interested in androgynous people because they are still considered out of place in everyday life. I’m concerned with how society relates to these people and how they interact with society. I am one of these people and I feel our presence in the world is not always positively acknowledged or appreciated. Androgynous people often want to be invisible. A photo essay of this nature addresses these concerns.

The ‘Split Halves’ series also questions how society perceives beauty. This includes the idea of androgyny, two- spiritedness, ambiguity, the boy/girl, the divided soul. I approached the people in my photographs individually, informed them of my project and spent two or three days with each person, documenting and interacting.

I focused on creating close-up portraits by placing my subjects against fragmented, reflective and divided backgrounds or dilapidated structures to emphasize the relationship between the world and my subjects. The series is shot in black and white. The background is carefully considered in the composition with the use of strong vertical or horizontal lines, running down and across the images, consistently in the series. This creates an imbalance that represents potential barriers or divisions between the subject and society. The models are looking directly at the viewer, creating dialogue and confronting the audience about neutral and structured gender roles. It is about presenting these people in their simplest form with their striking features that are neither strongly masculine or strongly feminine in dynamic, flowing light.

The aim is to inform and create an awareness of androgynous people and to capture the essence of their beauty. I want to create an intense and engaging emotional impact between the audience and the subject. I want these people to feel they have a place in the world, highlight the daily hassles of being androgynous and explore more ideas around neutral gender identity. I aim to photograph as many of these people as possible, from different ethnicities, different countries and environments. I want to create an archive for generations to come.

This final image shows the time I spent in Durban with a collective of Painters, writers, beauty queens and photographers. It captures a decisive moment of laughter and friendship.

More of Kelebogile Ntladi’s images can be found in her portfolio and on her blog.

Dutch writer to Italian newspaper: There’s “too much Africa in South Africa”

Oscar Pistorius being charged with the alleged murder of his girlfriend on Valentine’s Day has given the Dutch writer Adriaan Van Dis the chance to play “South African expert” in a long interview in Tuesday’s issue of the Italian newspaper La Stampa. Van Dis’s latest book, Tikkop (translated in Italian as “Tradimento”, or “Betrayal” in English), was the official reason why he’s being interviewed. La Stampa titled the article, “South Africa, The rainbow country where apartheid is replaced with fear.” According to the book’s Italian publisher Iperborea it is “a story about a trip in South Africa, memory about apartheid, the failure of a dream of freedom, friendship, and love for a language and a land.”

Oscar Pistorius being charged with the alleged murder of his girlfriend on Valentine’s Day has given the Dutch writer Adriaan Van Dis the chance to play “South African expert” in a long interview in Tuesday’s issue of the Italian newspaper La Stampa. Van Dis’s latest book, Tikkop (translated in Italian as “Tradimento”, or “Betrayal” in English), was the official reason why he’s being interviewed. La Stampa titled the article, “South Africa, The rainbow country where apartheid is replaced with fear.” According to the book’s Italian publisher Iperborea it is “a story about a trip in South Africa, memory about apartheid, the failure of a dream of freedom, friendship, and love for a language and a land.”

“There’s a reason why we have asked Van Dis about the current situation in South Africa,” explains the journalist Alessandra Iadicicco in her introduction: “It is because he comes from the postcolonial world, and was born to an Dutch East Indian father and an Indonesian mother; he also studied Afrikaans literature in South Africa in the 1970s. He visited the country again in 1994 to document the progress made there after Mandela’s victory, writing a reportage-novel titled The Promised Land. Now, in Tikkop, he exposes his post-colonialist disillusions.”

Inevitably, Van Dis is questioned about the Pistorius case. Van Dis, echoing the rhetoric of Pistorius’ apologists (and the basis of Pistorius defense), responds that: “the background of the murder is clear: The country is dominated by fear, people–black and white–live in terror.”

La Stampa’s journalist wonders if the losses to which Van Dis refers in his novel, and the present day atmosphere of fear that he speaks about are consequences of Apartheid. “Without a doubt,” Van Dis asserts. “The dismantling of the system of segregation has created a new privileged class of wealthy black people, as scared as white people are of the diffused criminality among the poorest of the country.” And: “Conquering freedom didn’t improve the life standard for everybody.”

It’s clear that Van Dis’s assessment of South Africa will inevitably scare readers and discourage anyone outside the country from ever contemplating a visit to South Africa. But there are even more ways in which he expresses his disappointment: “The country which, in the 1990s, represented hope for justice and redemption for the oppressed of the world has “Africanized” itself more and more in the last 20 years [si è sempre più africanizzato negli ultimi vent’anni], and it wasn’t able to implement European civilization values.”

And that’s the real betrayal for Van Dis: the lost of a European legacy supposedly associated with the country’s whites. But who is going to tell Van Dis that even Apartheid is part of this same legacy?

The best comment comes from a friend of mine on Facebook, who used a rhyme I have never heard to explain the link between the new Europeans, with all their pretty liberal views, and their forebearers:

“Gratta gratta l’europeista che vien fuori il colonialista” (Scratch, scratch the Europeanist, and you’ll find the colonialist)

No need to scratch too much to get at what Van Dis is all about.

Mamphela Ramphele has a Party

Post by Jonathan Faull and Sean Jacobs

Apathetic liberal hearts in South Africa (and some in the mainstream media) will beat a little faster, but fleetingly, for the cause of “Agang” (‘Let us build’ in Sesotho; though some claim it means something else completely), the new political platform launched earlier this week by Mamphela Ramphele, to “rekindle the South Africa of our dreams.”

South African voters’ dreams are certainly jaded, the promise of the early nineties eroded by a rising tide of inequality, rampant unemployment, and the realization that the African National Congress (ANC) has merely been masquerading as the benevolent vanguard of the masses. The movement of liberation has been thoroughly exposed as just another grubby political party, encumbered by vicious factionalism driven by the prize of state power–tenders, contracts, cookie jars. But Ramphele and Agang are unlikely to touch the impoverished lives of the majority of South Africans or stall our dissipating dreams.

It has been a long walk from Lenyenye, the impoverished township of Tzaneen, to which Ramphele was banished by the apartheid government for her activism in the cause the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) led by her partner Steve Biko (they had two children together while he was married to Ntsiki Biko). The good doctor is a remarkable woman, venerated internationally, and beloved of white liberals at home for her hard-nosed managerial acumen and her personification of the proof that black women can be hard-nosed and managerial.

Under the guidance of Francis Wilson, a well-known liberal stalwart and University of Cape Town (UCT) economist, she co-wrote two books on poverty in South Africa in the late 80’s and early nineties which propelled her from the imposed obscurity of her banning order, to the forefront of the liberal critique of apartheid. Harvard and Carnegie fellowships followed, and thereafter managerial appointments at the Institute for Democracy in South Africa (IDASA), UCT and World Bank. At the finalization of her term at the Bank she returned to South Africa where, with her son, Hlumelo Biko, she commenced a brief, but enriching career as a business woman.

It is unclear to what extent her track record as a manager has contributed to her stated intent to “[make our dreams of South Africa] a reality in the lives of ordinary people,” unless they are nightmares. During her time at UCT, hundreds of blue collar workers were laid off, their jobs outsourced and their livelihoods obliterated as part of an initiative spear-headed by Ramphele to increase the pay of university professors.

More recently there was speculation that the opposition Democratic Alliance wanted to make her its leader. She turned up at their events and seemed to flirt with the idea (there’s confirmation it seems), but later declined. (Among others, some DA leaders were worried followers couldn’t stomach a black leader yet.) DA leaders and ideologues, who used to praise her, are definitely disappointed and have tried to undermine her in public; either leaking her plans or disparaging her career (here’s that old reactionary RW Johnson “analyzing” Ramphele’s decision).

It would be unfair to blame Ramphele for the jobs massacre that has unfolded on her watch in the mining sector, but her presence on the board of Anglo American, and her appointment as Chairperson of Gold Fields appear to have done nothing to arrest the destruction of a quarter of a million jobs through the course of the past two decades. For that she won’t be getting any union members signing up for her party.

So what precisely will Agang build?

Ramphele has never enjoyed widespread grassroots support as a political figure in South Africa and hasn’t been in active in any political movement for at least 30 years now. The BCM is all but dead, living–to the extent that it does–in a handful of university seminar rooms, and in the blustering oped copy of a few, largely irrelevant, newspaper columnists. Much of the actual movement’s leaders ended up in Thabo Mbeki’s Cabinet, as advisors or in senior posts in the civil service. Regardless of which Ramphele’s political authenticity is premised on a largely symbolic association with the BCM, a movement with which she has had no practical connection since the early 1980’s.

It is a matter of deep historical irony that Ramphele’s natural constituency is precisely that against which Biko–before he was assassinated–railed in his days leading the fleetingly powerful BCM: She remains something of a heroine for the dwindling band of old school South African liberals (reluctantly still in the DA now) who have manifestly failed to project a successful political strategy, or find a political home since the noxious “Fight Back” campaign of the then-Democratic Party in 1999.

While Agang will stir the hearts of liberal newspaper editors, and lead to excited chatter in the old age homes of Constantia and Houghton, it is unlikely to draw significant support or break the existing mold of South African politics. We don’t yet know who will join her on this journey, who is funding the party (media reports suggested Mbeki’s brother and corporate backers), and–apart from an earnest critique of the electoral system (how that’s the main concern of the average, and we don’t mean suburban whites or blacks, voter–the party’s policy platform remains unknown. Don’t watch this space.

The Oscar Pistorius File

Post by Neelika Jayawardane and Sean Jacobs

The South African Olympic sprinter Oscar Pistorius shooting and killing his girlfriend seems to be the only news out of that country these days. Nothing else seem to matter. Even Usain Bolt was asked his opinion during what seemed like an interview to promote a brand on CNN. Bolt declared himself “shocked.” Shocking. There’s also the ridiculous: Femi Fani Kayode, a former Nigerian government minister, —in a rambling Facebook post—blamed Steenkamp for her own murder. Pistorius, Kayode claimed, “was provoked into a murderous rage by his pretty little lover (who) played on his insecurities and inadequacies.” Steenkamp was a “creature from the sea” sent by the devil. Okay? Incidentally Kayode was indicted for money laundering last week.

Yesterday, in court, in a statement read by his defence lawyer, Pistorius explained how it was all a horrible accident, and that he fired his gun in self-protection:

It filled me with horror and fear of an intruder or intruders being inside the toilet. I thought he or they must have entered through the unprotected window. As I did not have my prosthetic legs on and felt extremely vulnerable, I knew I had to protect Reeva and myself.

As this statement was read, Pistorius’ “whole body shook and he wept uncontrollably,” writes David Smith in The Guardian. The magistrate presiding over the case, Desmond Nair, became part of the ongoing drama, currying sympathy for Pistorius. Nair interrupted the court’s proceedings to give the athlete time to compose himself, because his “compassion as a human being does not allow me to just sit here.”

We’re not sure where this case is going, but based on Twitter after the first day of Oscar’s bail hearing, we couldn’t mind wondering whether it was correct to summarize the media coverage (and circus) around Oscar Pistorius thus: first they believed him, then they discovered his “dark side”, now they believe him again because he sobs in court.

While there was much scrutiny about Pistorius’ past, and hand-wringing about “how could we have missed the signs” (especially given that there was a past record of a domestic violence incident in Pistorius’ past) there was an equal–though very different–spike in interest about the woman he stands accused of shooting dead. In the US, this all reminds us about/mirrors the same sort of prurient scrabble for the hopefully-scandalous details of Nicole Brown Simpson’s life.

During the short period that has passed between the 14th of February, when police arrived at Pistorius’ home to discover Steenkamp’s body, and the 19th, when Pistorius was formally charged with the murder, most tabloids here in the US and in Britain have used every opportunity to run photo spreads of a half-naked Steenkamp–she was a model after all, and often posed in bikinis.

South Africa’s public broadcaster, the SABC, then aired a reality TV show in which Steenkamp appeared–Tropika Island of Treasure, a sort of competitive Fantasy Island/Survivor project that was shot in Jamaica–of which she was said to be “proud.” The show’s executive producer, Samantha Moon, told the South African Mail & Guardian that going ahead with the show “is what she would have wanted,” not letting a little thing like lack of clairvoyance into a dead person’s mindset get in the way. Furthermore, Steenkamp’s family apparently approved the decision to air the show, according to other media outlets:

“We felt that it was important for people to know that there was more to the narrative of Reeva than an exceptionally beautiful girl in a bikini, that she was strong and vibrant and funny and lovely and that this is a tragedy on an unspeakable level,” Moon explained.

We agree that Steenkamp may have been proud of her last job, and that she undoubtedly worked hard to maintain the contrived shape demanded of those asked to commodify their bodies. Steenkamp, from all reports, sounds like a savvy professional with strong family support–she was hardly an exploited, powerless person. But it did look unseemly that while we spoke blithely of the commodification of women’s bodies, and the relationship of such commodification to gender-based violence, we were simultaneously treated to images of Steenkamp’s participation in the industry that commodifies women’s bodies. In any case: we won’t belabor what’s wrong with those tabloids’ and SABC’s decision. We’d suggest you read Marina Hyde and Paul Harris separate op-eds on The Guardian’s website.

At some point last week it turned out Moon’s company was charging news outlets “$3,000 each to broadcast a short clip from the television show–with at least a dozen networks buying rights.” Some South African news sites have been rubbing their hands with glee at the spike in traffic that the story brings.

Until he was accused of murder, Pistorius was an idealized figure–a product in an exciting, innovative package that everyone from Nike to South Africa’s government, its boosters and the country’s people were only happy to use as a symbol of triumph against adversity. One of the more outrageous attempts at branding Pistorius has been to read him as some kind of stand-in for South Africa’s current state, and to construct his journey to one that equaled Nelson Mandela’s long walk to freedom. Britain’s Sunday Times (in an article reprinted by the New York Post) even invented a status for him: “In South Africa, where he is placed on a pedestal alongside leading figures of the apartheid struggle, making him one of the few whites to straddle the racial divide …” To their credit, most South Africans find this notion–equating Mandela with Pistorius–a ridiculous proposition.

Post murder charge, the usual suspects were rounded up to help support these claims. The Independent trotted out the journalist John Carlin, who is much responsible for the “Invictus” myth associated with South African rugby and sports’ supposed role in the political transition. (Carlin’s book on the 1995 Rugby World Cup served as the basis for Clint Eastwood’s movie.) Carlin, whose piece is really about Pistorius’ loss of reputation, positions Pistorius as a Mandela-cure for the dystopia and malaise of the 2000s, but concludes Pistorius, like Shakespeare’s Othello, is only capable of bestial deeds in the end. To top it off, Carlin’s piece was accompanied by a snapshot of Pistorius with Francois Pienaar, the captain of that 1995 rugby team idolized in Carlin’s book.

Another storyline has been to suggest Pistorius’ actions are understandable given exceptionally high crime rates in South Africa. He acted out of self-defense, like anyone would–perhaps his girlfriend had surprised him at his home. But by this past weekend, it had already emerged that his girlfriend was not an intruder that Pistorius shot at in order to protect himself, and that neighbors had heard them quarrel earlier that evening before the shooting.

In South Africa, Pistorius was largely lauded. There is and will be much scrutiny about Pistorius’ past, and hand-wringing about “how could we have missed the signs?” But there were ample, and very public signs of his win-or-rage attitude. First, there were tabloid reports hinting of his ‘other’ nature and his ‘wandering eye’ (an interview with a former girlfriend). But being sexually promiscuous is hardly an indication of violence–in that case, call a large percentage of our students (both women and men) violent. There were also real clues about Pistorius’ violent nature–from a previous charge of assault on a woman, from not so long ago.

Then, at 2012′s Paralympics, Pistorius threw a tantrum when he lost the 200m to a Brazilian sprinter, Alan Fonteles Cardoso Oliveira. Convinced that the longer running blades Oliveira used was the reason he won, Pistorius called for the International Paralympic Committee to investigate. Although he was usually seen as the gracious man who said, “Don’t focus on the disability … focus on the ability,” in his post-race interview, he furiously told TV cameras, “we aren’t racing a fair race.” He seemed oblivious to similar charges leveled at him by ‘able-bodied’ athletes. In order to defend his competitive behavior, and to fashion Pistorius as a spokesperson for egalitarian treatment, several reports rehashed apocryphal stories about how his mother famously treated him the ‘same’ as she hid his brother. He remembers these instances when asked about why he pushed himself so hard:

…to underline his no-nonsense attitude to his disability was his mother’s instructions to him and his older brother Carl when they were getting ready to play one day as children: “You, put your shoes on. And you, put your legs on.” “That was disability as I saw it,” [Pistorius] said.

Ultimately, journalists excused his behavior at the Paralympics as the stuff of “real rivalry.” The hero-making rhetoric entered to re-fashion Pistorius’ ugly response as something that could advance the cause of Paralympians–it became an opportunity to review our stereotypes: we needed to see paralympians as athletes who are just as crazily competitive as ‘able-bodied’ athletes–so stop patronizing them as people who enter competitive sport just to be nice.

After it became clear that Pistorius had shot and killed Steenkamp, many journalists began referring to a January 2012 New York Times piece by Michael Sokolov that reported the extent to which Pistorius was obsessed with guns, and the possibilities offered to Pistorius in an inherently unequal society. Sokolov points out:

But [Pistorius] also comes from a nation with a breathtaking gulf between rich and poor, and if he had been born on the wrong side of that, into the abject poverty in which many of his countrymen still live, it is impossible to imagine him having the resources to have prevailed over his bad luck.

However, in Sokolov’s article, the only piece known for being even mildly critical of Pistorius, there are sections that give a reader clues about how foreign journalists often misread the athlete. Even the insights linking the privileges created by apartheid that helped someone like Pistorius get where he did, as well as his frank discussion of Pistorius’ gun-obsessions are tainted by Sokolov’s own misreadings of South Africa, whiteness, and how Pistorius encounters, engages with, and enjoys his privilege–all the while speaking the right words about being aware of the poverty and lack of access to the millions hop and a skip away.

For example: when Pistorius speaks a smattering of the “local languages,” and calls guards at the gate “my brother,” Sokolov takes these mundane exchanges as a sign of his great charitable heart, his desire for egalitarian society. As anyone in Southern or East Africa might know, many Africans of European descent, whose families have been there for generations (five, in Pistorius’ case), often speak fluently in a ‘local’ language. Sometimes that fluency is due to true amalgamation with locality. At others, we’ve seen familiarity with a local language as an entryway into the lives of one’s household or jobsite staff–a madam of a fancy household knows what the kitchen maid is muttering under her breath to the gardener, removing that minor level of privacy and subversive space afforded to those in colonially-created subversive spaces.

But mostly, Africans of largely European descent in South Africa may speak a smattering of Zulu or Xhosa: a bit of a greeting, a passing remark, all of which is thrown out to signal familiarity, as ceremonial signal of brotherhood and belonging. No one on the receiving end of a random ‘Hello how are you’ in Xhosa will believe that such an act is an indication and recognition of mutuality … no one, that is, other than a foreign correspondent.

Sokolov did get something right: he was the first to call attention to Pistorius’ level of interest in guns, and the amount of confidence they seemed to impart to him. Pistorius’ father is still busy defending his son–it is a defence built on South Africa’s particular brand of masculinity that creates a mythology around ‘sportsmen’, coupled with the heightened dangers posed for the colonial in the postcolony. In the Telegraph, he stressed that ‘sportsmen’ are exceptional, and that South Africa creates exceptional conditions:

“When you are a sportsman, you act even more on instinct,” he said. “It’s instinct – things happen and that’s what you do.”

“When you wake up in the middle of the night – and crime is so endemic in South Africa – what do you do if somebody is in the house? Do you think it’s one of your family? Of course you don’t,” he said.

When Sokolov’s observations are coupled with recent academic work on white South African masculinity–research that traces the way that manhood was historically built on a foundation that stressed the colonial male’s role in protecting family against marauding natives and on providing meat–a lot more becomes clear.

South Africa’s particular brand of white masculinity depends on guns, perpetuating the fear of native threat, hunting (even if only for display), and ensuring that women stay pretty and in their proper place. Mama, papa, boarding school, rugby, and the weekend braai are centred on fashioning generation after generation of this Man’s Man, and the adoring, complicit girlfriend and wife are just as much part of it–despite the violent tendencies such adoration and adulation inevitably nurtures. This somewhat problematic article in The Guardian says as much, despite Alex Duval Smith’s idiotic choice of quote for something as sensitive and important as the relationship between race, masculinity-construction, and domestic violence in South Africa:

“Black South African men are expected to prove their manliness by carrying knives and having lots of girlfriends,” said Rachel Jewkes of the South African Medical Research Council. “White Afrikaners like Pistorius do not need to have several girlfriends. But his love of guns speaks to the same hunger to prove his masculinity in the South African context.”

We’ll leave the SMH to you over the first part of this quote (don’t just as large a percentage of white South African men–openly or secretly–subscribe to the same culture of having several sexual partners as proof of their manhood and, in fact, carry knives around?), and Duval Smith’s lack of commentary on it (she’s usually on point).

However, yes: Pistorius’ dependence on firearms, and the amount of confidence they seemed to impart to him was as indicative of the level of hyper-masculinity on which South African gender roles are built. And the pressure to display macho-ness could also have been exaggerated in Pistorius–his desire to display mastery over his domain, his aggression, and his special dependence on guns speaks volumes about overcompensating for a disability, of which he was not permitted to speak or allowed to acknowledge.

February 19, 2013

Another Hero Story: CNN’s “Mozambique or Bust” Documentary

A story about “how ordinary people come together to do something extraordinary,” this is how the Actress and UN Goodwill Ambassador to Combat Human Trafficking, Mira Sorvino, introduces the work of four white Americans who send over 30,000 used bras to be sold in Mozambique by former sex slaves. The new CNN documentary “Mozambique or bust” (now online; part 1 above) is another celebration of American heroism in which the white savior comes to Africa, this time to Mozambique.

The documentary traces the donation, collection and shipping of used bras from Denver to Maputo, Mozambique’s capital. It features interviews with the two founders of Free the girls, an American NGO that found its calling in helping former sex slaves make a living with selling bras in the market. It also includes statements from the director of the partner organization, Project Purpose, in a town close to Maputo, a safe house where women that had been trafficked to work as prostitutes live after they were freed and are “spiritually and emotionally restored.” Except in the very beginning, we hear few statements from the women themselves—oh, but right! They are not the heroes in this story.

“From the depth of darkness come stories of hope and heroism,” Mira Sorvino says, and the camera shows us Dave Terpestra, one of the founders of Free the girls, kicking a football with his kids. Dave heard stories of human trafficking and “just couldn’t let go,” he had to move to Maputo and help! He could not offer legal help (since he was not a lawyer), but could offer his “care” and help the women earn money so they could support themselves. His idea was simple—there are lots of bras in the “graveyard” of American women’s underwear drawers, bras are a luxury item in Mozambique, and the women from the shelter, by selling bras to women, could work with women, which would provide them with a safer environment than working with men.

Here’s part 2:

The documentary is a feel-good story—“anyone can help” is the message, even the stay-at-home mom! We also see that helping is emotionally fulfilling (Dave’s NGO co-founder Kimba Langas cries when the truck with the bras leaves). And it’s so simple: Just donate whatever you no longer need.

If it only were so simple. After the pilot sale of some bras proved a success, the women in the safe house had to wait for the shipment from the US, which was delayed several months. This situation could have shown the NGO the kind of dependencies it was about to create. But nope, the heroism continued, the partnership with an international shipping company started, and charity made all the challenges disappear over night. The bras arrived in Maputo, and their arrival “made the girls smile,” which is “so rare for these girls” (by the way, why are the 15 years-old and up called “girls” all the time?). That’s success, isn’t?

Well, we don’t know. The women’s business will depend on charity as long as the women don’t have anything else to do than selling bras. The import of second-hand clothing is a questionable contribution to Mozambique’s economy. I give credit to Free the girls that they respond to some criticism on their website and link to studies that are supposed to show that the import of second-hand clothing does not have a negative impact on the domestic economy by substituting domestic production. Well, supposed to, since the linked studies do not provide a simple answer, although they do review literature that questions the direct relation between an increase in second-hand clothing and a decrease in domestic clothing production. More importantly, however, Free the girls calls its project sustainable because the women have to pay for additional bras once they sell their initial inventory. No mentioning of how the women are supposed to sustain their own future when they no longer have access to bras from America. Oh, but right! Every international NGO needs to make sure that they are needed as long as possible.

As always, the intentions are good, but we know even if they are, development policy should rarely be based on them. It only makes for a glossy CNN documentary, not for an actually sustainable and equitable development project that empowers the recipients. Don’t get me wrong, it’s important to fight human trafficking and support the women of Project Purpose’s safe house, but the question is how.

As a side note and historical reminder, there was a time when bras were understood to be more confining than they were liberating. But that doesn’t fit into the hero story, not if it’s about white men and stay-at-home moms. Kimba is actually an award-winning filmmaker we learn on the NGO’s website, but CNN did not see this fit into its story of ordinary people doing extraordinary things.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers