Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 485

March 9, 2013

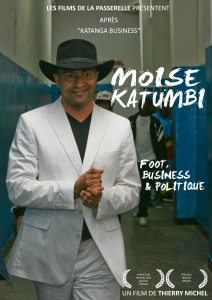

5 African Films to Watch Out For, N°18

Taking cues from the Belgian Africa Film Festival programme (which kicks off on March 15, running until March 30), here are 5 more films to watch out for. Below is the trailer for documentary maker Thierry Michell’s portrait of Congolese businessman-governor-football club owner Moïse Katumbi Chapwe. Michell’s relentless dedication to all things Congo is quite impressive. Remember for example his Mobutu King of Zaire, Congo River, Katanga Business, or the recent documentary on the murder of human rights activist Floribert Chebeya (which landed him in trouble). For a fairly complete list of his other work, see here. Moïse Katumbi: Foot, Business, Politique seems to suggest Katumbi might become the DRC’s next president.

Taking cues from the Belgian Africa Film Festival programme (which kicks off on March 15, running until March 30), here are 5 more films to watch out for. Below is the trailer for documentary maker Thierry Michell’s portrait of Congolese businessman-governor-football club owner Moïse Katumbi Chapwe. Michell’s relentless dedication to all things Congo is quite impressive. Remember for example his Mobutu King of Zaire, Congo River, Katanga Business, or the recent documentary on the murder of human rights activist Floribert Chebeya (which landed him in trouble). For a fairly complete list of his other work, see here. Moïse Katumbi: Foot, Business, Politique seems to suggest Katumbi might become the DRC’s next president.

Next is The Teacher’s Country, a film by Benjamin Leers about home and belonging in Tanzania, 50 years after its independence. One of the characters followed and interviewed in the documentary is Tanzania’s first President Julius Nyerere’s son Madaraka (who’s a prolific blogger, by the way):

There’s the short film Nota Bene by Rwandan director Richard Mugwaneza, tracing a boy’s move from his village to the city. Actors include Rodrigues Cyuzuzo and Jean Pierre Harerimana. The film’s website has a detailed write-up about the production of the project.

C’est à dieu qu’il faut le dire (God’s the one to tell) is an older short film by Elsa Diringer (2010, 19min.) but I haven’t seen it screened in many places since it came out. Set in Paris, the lead role is played by Tatiana Rojo (Côte d’Ivoire).

And Pourquoi Moi? (Why Me?) is a short fim by Burundian director Vénuste Maronko, tackling violence against women. The dramatic and experimental film is available in full on YouTube (below) — not of the best quality but that might be partially explained by its home cinema “of the 1950s with a 8 mm camera” aesthetics:

* All films will be screened at the Africa Film Festival. Look out for their selection of other Burundian short fims.

March 8, 2013

The media caricature of Hugo Chávez

The mainstream media has been in overdrive working lockstep to uphold their ridiculous caricature of Hugo Chávez. The campaign has led to some pretty desperate and shallow displays of journalism. There’s the AP reporter who reported that Hugo Chávez wasted his country’s money on healthcare when he could have built gigantic skyscrapers. Then there’s the rest.

The venerable BBC is a representative of what passes as mainstream coverage of Chávez’s passing. For its “Africa Today” podcast on Thursday (listen from 7:52 mark) who did the BBC call upon for an African perspective on the death of Chávez, whom the broadcaster habitually disparages, and misrepresents? Not one of the manifold African heads of state or prominent activists who have issued heartfelt, glowing tributes over the past few days (for example, Ghana’s President John Mahama), but former African National Congress Youth League of South Africa president Julius Malema, another favorite target of the BBC’s disdain and disapproval.

Introducing the short segment, the BBC interviewer Esau Williams proclaims that, like Chávez, Malema is “…another politician who divides opinion.” Clearly, it is reasonable to ask, is there any politician who does not divide opinion? Is that not the whole point of the liberal democratic model that the West so much cherishes and enforces in the rest of the world? Moreover, is it not deceitful to deny that Chávez was immensely popular amongst Venezuelans, as evidenced by his lopsided victories in elections deemed free and fair by international observers and even domestic opponents? And whatever disagreements one may have with Malema’s politics, is it not dishonest to refuse to accept that his supporters in South Africa vastly outnumber his detractors? Certainly, no British politician enjoys the soaring approval ratings of either Chávez or Malema in their respective countries, yet surely Cameron and Miliband “divide opinion,” too.

Conforming to the BBC’s blatant mission of defending neo-liberalism and dismissing all challenges, the presenter then poses a series of loaded, patronizing questions that Malema deftly answers without losing his cool. Indeed, while I have disagreements with Malema’s politics, I was quite impressed by his patient, concise, and sincere responses to Williams, who abandons even the basic journalistic pretense of objectivity in his agenda of belittling Chávez’s legacy.

The short interview offers Malema an opportunity to defend Chávez against the usual unsubstantiated attacks as well as offer a crash course on imperialism as Williams dutifully upholds prevailing ideology. Consider this early exchange, during which Malema skillfully responds with facts while reinforcing his own domestic agenda:

Williams: Also, didn’t [Chávez] represent an old and quite frankly failed ideology of nationalization.? I mean, most countries in Africa this day and age don’t seem to buy into that idea of nationalizing industry, moving more towards market-oriented form of economics.

Malema: In Venezuela, we have seen the success of nationalization of both the mining industry and the oil industry and, as a result of that nationalization, we have seen the strengthening of education, health, and the people of Venezuela directly benefiting from the natural resources of their own country. Despite market resistance from imperialist puppets, Chávez remained committed and remained steadfast on the idea of people owning their own resources.

Loyally following the script, the BBC journalist then raises one of the simplistic charges against Chávez, repeated ad nauseam by the media: “But also didn’t that come with some baggage, in terms of making friends with all the wrong people?” Malema chooses to evade that one, but an impartial listener would ask, “whose wrong people”? Of course, Williams means Cuba’s Fidel Castro, Iran’s Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, and Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi. But, the relationship between Venezuela and Cuba has been mutually beneficial, providing blockaded Cuba with oil in exchange for doctors and teachers dispatched to the poorest communities in Venezuela. It is only normal Venezuela and Iran, as leading members of OPEC, would cooperate, especially when both nations are subject to destabilization campaigns by the U.S. And was not Gaddafi, at least in the several years leading up to his murder during the 2011 NATO military invasion, a friend of the West? Are the dictators of Bahrain, Equatorial Guinea, Saudi Arabia, all crucial allies of the West, the “right people”?

Betting that persistence pays off, the presenter returns to his original argument with the following question:

But, looking more broadly at the international scene, I mean you’re talking about a system that has manifestly failed, the Soviets have ditched it, the Chinese don’t think it works, only — I don’t know — Cuba or Venezuela think that that it works.

Malema rightly points out the prevailing support for socialist parties and governments throughout Latin America and patiently explains “it doesn’t mean that if it has failed in the past, you can’t look at where it has failed and ensure that it works better for our people and don’t repeat the previous mistakes.”

Undeterred, Williams perseveres, condescendingly asking, “Isn’t it true that the only and single unifying force that binds you and Mr. Chávez’s ideology is your common hatred for the west”? Ignoring the provocation, Malema corrects the journalist by saying he and Chávez shared a “common hatred of imperialism.” Astonishingly, Williams asks for clarification: “And when you say ‘imperialism’ what does that phrase [sic] mean?” Malema succinctly presents the reality that not only Venezuela under Chávez, but all former colonies face in the capitalist world system, particularly in Africa:

It means those who want to micro-manage our country both economically and politically through installing of their stooges and their puppets run our country on their behalf pretending that those are the outcomes of a democratic process which they themselves would have manipulated.

Probably exhausted from his failed interrogation, Williams concludes with the one question that addresses the very reason for the interview: What is Chávez’s legacy for Africa? Malema admirably stays on message: “A legacy of fighting first against imperialism and that legacy will inspire many young people to continue to fight for their economic freedom because that is the most relevant struggle today.”

One can only imagine how increasingly difficult it must be for the managers of information, staring at their computer screens in corporate offices in London and New York and other cities of capital, to contradict the images of hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans mourning their comandante in Caracas; the reports of a fast growing number of nations within and beyond Latin America (including African giant Nigeria) declaring official days of mourning in honor of Chávez; and not least the indisputable hard facts attesting to the successes of Chávez’s Bolivarian Revolution: drastic reduction of poverty, dramatic expansion in access to education and health care, genuine democratization of civil society, amongst many others.

The BBC must be regretting selecting Malema as the African charged with defending Chávez’s legacy.

* BTW, we could not help noticing South African media outlets — in a country as equally unequal as Venezuela — parrotting global news media when reporting on Chávez’s passing. They also went to Julius Malema for comment. Here’s an example from ENews Africa who decided Malema is Chávez.

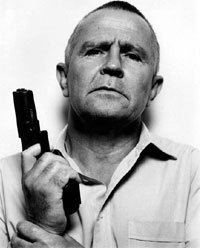

Dirk Coetzee is Dead: The legacies of Apartheid’s death squads and the TRC

Dirk Coetzee was one of an infamous group of police and law officials responsible for some of the apartheid government’s most egregious human rights violations, ranking among the likes of Eugene de Kock (known as “Prime Evil”) and the apartheid Minister of Law and Order Adriaan Vlok. I read the announcements of his passing over my cheerios and headed to Twitter to watch the responses. His death has sparked South Africans to consider the South African decision to grant amnesty to qualifying violators of human rights like Coetzee via the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). Some praised the country’s willingness to grant him forgiveness while others expressed regret that more conventional justice had not been dealt. But a rather clear sentiment emerged. Good riddance.

Dirk Coetzee was one of an infamous group of police and law officials responsible for some of the apartheid government’s most egregious human rights violations, ranking among the likes of Eugene de Kock (known as “Prime Evil”) and the apartheid Minister of Law and Order Adriaan Vlok. I read the announcements of his passing over my cheerios and headed to Twitter to watch the responses. His death has sparked South Africans to consider the South African decision to grant amnesty to qualifying violators of human rights like Coetzee via the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). Some praised the country’s willingness to grant him forgiveness while others expressed regret that more conventional justice had not been dealt. But a rather clear sentiment emerged. Good riddance.

Apartheid prided itself with governing through the “law,” but was infamous for its use of other murders, poisonings, arsons, and kidnappings against its opponents. Coetzee was a central figure in such killings.

Coetzee was the founding commander of the covert South African Police counterinsurgency unit based at a farm called Vlakplaas. The Vlakplaas unit was part of the regime’s “total strategy” to counter the tide of anti-apartheid resistance. Coetzee and those stationed under him were responsible for the 1981 assassination of anti-apartheid activist and attorney Griffiths Mxenge and countless other murders, poisonings, arsons, and kidnappings.

When journalist Jacques Pauw (In the Heart of the Whore and Into the Heart of Darkness) and psychologist with the TRC Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela (A Human Being Died that Night) struggled with whether or not to condemn these assassins as outright evil, they compared the hit squad activities to the “banality of evil” described by Hannah Arendt in her coverage of Adolf Eichmann’s trial. These were men who accepted the premise of the apartheid state and normalized their work.

But it is perhaps Coetzee’s 1989 first public admission in the liberal Afrikaans newspaper, Vrye Weekblad, his cooperation with the African National Congress, and subsequent testimonies before the farcical Harms Commission of Inquiry into apartheid hit squads and the TRC that have most complicated the legacy of Dirk Coetzee.

Coetzee’s confession to Vrye Weekblad’s Pauw enabled a seven-page story that detailed the violent workings of the apartheid government. In his memoir, former Vrye Weekblad editor Max du Preez captured the weight of Coetzee’s confession when he described the practices of the Vlakplaas squad: “Particularly gory was his version of how he and his cohorts burned the bodies of murdered activists while standing around with a beer in their hand” (Pale Native, 217).

Coetzee’s revelations opened the door as other Vlakplaas operatives began to talk. Coetzee fled to Lusaka and London, where he gave his testimony to ANC lawyers (for more, read Peter Harris). During the sitting of the TRC, he applied for and was granted amnesty for the murder of Mxenge. The same year, Eugene de Kock, Coetzee’s successor at Vlakplaas, was convicted for an attempt to murder Coetzee for the betrayal. This failed attempt resulted not in the death of Coetzee, but Bheki Mlangeni, a young ANC activist and attorney who represented Coetzee at the time. Based upon the testimonies of Coetzee and de Kock, the TRC found that a “network of security and ex-security force operatives, frequently acting in conjunction with right-wing elements… was involved in actions that could be construed as fomenting violence and which resulted in gross human rights violations, including random and target killings” (TRC Report Vol 6, 584). (He also made damning revelations regarding corruption in South Africa’s 2012 textbook fiasco, but that’s another subject.)

I’m not going to go as far as Max du Preez, who once suggested the new South Africa might “owe” Dirk Coetzee for his confession (Pale Native, 221). But as a historian who studies this era of violence, I will say that his death makes me wonder about his legacy and what scholars, journalists, and everyday South Africans think and know about Coetzee and men like him. In an eNews story, former TRC Commissioner Dumisa Ntsebeza condemned Coetzee, who he believed had made his admission solely to save his own skin. There are also suspicions that Coetzee had not revealed all. One historian and former TRC researcher, Madeleine Fullard, lamented via Twitter yesterday that Coetzee took to his grave the location of anti-apartheid activist Sizwe Kondile’s remains.

Whatever his motives, Coetzee’s disclosures set in motion a wave of revelations about regime-sponsored human rights violations and state support for right-wing elements that hastened apartheid’s demise. As the regime destroyed damning records, the testimonies of men such as Coetzee remain an important means for these stories to be told. Not surprisingly, the highest state officials and foot soldiers alike were and remain hesitant to talk. But like Coetzee and de Kock, some have spoken (such as those who spoke to De Wet Potgieter for the South African History Archive), and some still might. While his legacy will certainly be contested, Dirk Coetzee’s death should be a reminder to us that it is not only the stories of the liberation struggle’s heroes that might need to be recorded before they are lost.

* Jill Kelly is an assistant professor of history at Southern Methodist University.

Weedie Braimah and Amadou Kouyate’s Blends

Guest Post by Robert Nathan

They’re not your average musicians. Sons of West African griots and court musicians brought up in Washington DC and St. Louis, Weedie Braimah and Amadou Kouyate have straddled the Atlantic all their lives. Indoors, they assiduously studied the kora and the djembe under the guidance of their fathers — master musicians from Senegal and Ghana. But outside people weren’t too familiar with the instruments they played, much less the historic institutions to which their families belonged. “I grew up in an African house, true enough,” Weedie says. “But at the same time when I walked out of my door, I had a whole different world. I grew up in the Hip-Hop age.” That’s a paradox they’ve been living with all their lives.

But it’s one to which these uniquely placed artists have reconciled themselves. Masters of their craft — and just as comfortable on snare and guitar as on calabash and kora — they’re one more example of artists experimenting with a fusion of African and American musical influences. Inheritors of those two traditions, they move between them like there were no boundaries at all.

And that, in a way, is what Weedie and Amadou are all about. They’re not parroting old djembe rhythms, nor curating a musical museum of African sounds. Above all else, they’re creators. And they’re letting their creativity run wild.

The result is a duo with a captivating show. One minute you’re at a Dakar dance party, the next Weedie is hitting the snare so hard you think you’re at a Roots concert, and then Amadou lays down a luscious kora riff that unexpectedly turns into a Bill Withers song. They’re all over the place — and it works. See for yourself in this clip recorded before a 700-strong crowd at Victoria’s McPherson Playhouse in Canada:

This organic blending of influences is infectious. Weedie and Amadou are masterful with any material, and you catch that vibe when they’re on stage. They feel the weight of their African musical lineage, but they also that of the American musical greats who inspire them. “I feel a responsibility to my Kouyaté lineage. But I’ve got a sense of responsibility to making sure Sam Cooke and Donnie Hathaway are heard, that Coltrane gets heard, too.” And they want to be understood in that transcultural context. They aren’t a curiosity. They don’t want people to dig them because they’ve never heard a kora before and the experience is novel. They want people to like what they do because they like it, and because of the musicianship they bring to the stage.

From their perspective, while they respect the Africa-US musical collaborations that have taken place in recent years between artists like Ry Cooder and Ali Farka Touré, these have tended to be superficial. “It’s mostly cosmetic,” Amadou says in an interview outside a djembe workshop at the University of Victoria. They have the right to speak that way. After all, if you didn’t grow up in an environment where you ate your Corn Flakes and then practiced kora with your master musician father before heading to school with the rest of DC, how could you gain the knowledge required to fuse the African and the American at such a profound level?

Weedie and Amadou are proud of their complex musical heritage. And they want African Americans to be proud of a musical tradition that belongs to them too — one that many in the US don’t know much about. But at the end of the day, they’re artists with musical sledgehammers, and they’re breaking down the borders that exist between ‘African music’ and music writ large. In this respect they’re part of a broader global movement to deparochialize African art, and their work resonates with efforts like the Manifesto for a World Literature in French (a document signed by authors like Alain Mabanckou and Nobel laureate JMG Le Clézio that aims to erase the difference between African literature and literature tout court). Indeed, the day when djembe and kora get the same respect as piano and saxophone is they day they’ll rest easy.

In a way that day’s already here, because they play with jazz greats like Chick Correa who love their style. But there’s still plenty of work to be done. So until then, expect Weedie and Amadou to bring their transgressive sound to the world stage by stage, showing everyone what it means to be an African, an American, and an artist who transcends these narrow boundaries.

* Robert Nathan is a doctoral candidate in African History at Dalhousie University (Canada). Weedie Braimah and Amadou Kouyate’s first album will be out soon.

How the Africa-China romance is killing Europe

In the past decade the international media first focused on China’s economic boom, which was then followed by the ‘Africa is rising’ narrative. The latter partly as a result of China’s investments. Many have wondered whether China’s interest in Africa would trigger a new wave of colonialism and exploitation of mineral resources, needed to keep Chinese factories going.

On regular occasions one would find media analyses of the China-Africa romance (like here, here and here). And like a mother not too happy with her daughter’s choice of partner, the experts tended to be wary of the authenticity of the cute new couple. Even when South Africa became the ‘S’ in BRICS, the rest of the world (read: the West) had its doubts. Was South Africa ready to play with the big boys?

As it now turns out, what the West, and Europe in particular, have been afraid of all the time is how much the “Old World” would lose because of the new relations between China and the African continent. A documentary on Dutch public television by broadcaster VPRO, that premiered recently, painfully shows the consequences for Europe now that it virtually has closed its borders, while China is welcoming African migrants with open arms.

The 45-minute documentary entitled “Zwart geld: De toekomst komt uit Afrika” – “Black money: The future comes from Africa” (one could question the title) examines two things.

First, we see how migrants live in ‘Nigeria Town’ in the Chinese city Guangzhou.

Four Africans – three Nigerian men and one Mozambican woman – serve as living examples how life is like after having roamed across the globe in the hope to find employment or to do business. (Usually the latter.) It’s intriguing to watch the easiness with which the main subjects go about their daily life and interact with their Chinese business partners; there seem to be no signs of racism, a subject that inevitably needed to be covered by the filmmakers. It’s a totally different picture of the loneliness and hardships endured by African immigrants who came to Europe as seen for example in the documentary series Surprising Europe.

African migrants in China are far better off as we learn that one can make $5,000 a week in China, that an individual can make it in China and that on a daily basis twenty to thirty million dollar is sent from China to Nigeria in cash.

The second narrative of the documentary focuses on the losses for Europe as a result of the economic romance. This time no European experts, but South African economist Ian Goldin and Cameroonian historian Achille Mbembe. Goldin, the former Director of Development Policy at the World Bank and now Director at the Oxford Martin School paints a clear picture for Europe: “I predict that in 2030, Europe will be saying desperately: ‘we want more Africans’.” A pretty grim picture for those political leaders in Europe who in recent years have been working hard to build the European fortress.

A lot of the analysis and facts Goldin presents about the economic dawn of Europe are not new. However the connection he draws between the liberal economic policies that have enabled free flow of people and goods in Europe for the economic good of the continent and the liberal politicians that have drafted these policies while also being the ones responsible for the strict immigration laws might be the most interesting.

As the main focus of the documentary is on the economic consequences (positive for Africa and China, negative for Europe), Mbembe seems to be given an appreciative nod rather than adding something substantial. His role here is merely to question “Why is Europe unable to understand that the world we live in is a totally different world. And that the future of the world more and more won’t be decided in the West.”

Watch it here (interviews are in English).

* Photo: Pieter van der Houwen.

March 7, 2013

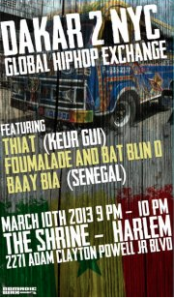

Rap Comes Home

It’s quite a weekend for New York’s prodigal child. Hip-Hop, that burst of youthful energy that was put out into the universe 30 plus years ago is coming back home from several places at once. It’s arriving at a time when Rap music, in its birthplace, confusingly straddles the realms of hyper-capitalism, political activism, youth expression, marginalized’s rebellion, adult reminiscence, mainstream politics, canonization, trivialization, and institutionalization. Regardless of the strange position that the genre has taken up in the contemporary American social landscape, the spirit of youth energy that birthed the genre, as well as the need to make heard the voices of the marginalized is very much at the forefront of the form globally. On Saturday and Sunday New Yorkers will be able to get a glimpse at the practitioners of Hip-Hop in this form at two different shows.

It’s quite a weekend for New York’s prodigal child. Hip-Hop, that burst of youthful energy that was put out into the universe 30 plus years ago is coming back home from several places at once. It’s arriving at a time when Rap music, in its birthplace, confusingly straddles the realms of hyper-capitalism, political activism, youth expression, marginalized’s rebellion, adult reminiscence, mainstream politics, canonization, trivialization, and institutionalization. Regardless of the strange position that the genre has taken up in the contemporary American social landscape, the spirit of youth energy that birthed the genre, as well as the need to make heard the voices of the marginalized is very much at the forefront of the form globally. On Saturday and Sunday New Yorkers will be able to get a glimpse at the practitioners of Hip-Hop in this form at two different shows.

On Saturday at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, Brooklyn’s oldest and largest performing arts venue. It features El Général (whose music we featured here and here), Amkoullel (here), Deeb, and Shadia Mansour (here) alongside Oud player Brahim Fribgane and Ngoni player Yacouba Sissoko.

On Sunday, a showcase of Senegalese rappers called Dakar 2 NYC will take place at The Shrine, a smaller community bar and venue in Harlem. The showcase is part of a series put on by Nomadic Wax called Internationally Known (Africa is a Country is a co-sponsor), and features Thiat from Kuer Gui (whose video we featured here) and the group Fou Malade were two of the groups that were central to the Y’en a Marre movement (whose politics we featured here). They will be joined by Bat’hallions Blin-D and Baay Bia. Notably this event is happening in the heart of the community that hosts the largest Senegalese diaspora population outside of Europe.

On Sunday, a showcase of Senegalese rappers called Dakar 2 NYC will take place at The Shrine, a smaller community bar and venue in Harlem. The showcase is part of a series put on by Nomadic Wax called Internationally Known (Africa is a Country is a co-sponsor), and features Thiat from Kuer Gui (whose video we featured here) and the group Fou Malade were two of the groups that were central to the Y’en a Marre movement (whose politics we featured here). They will be joined by Bat’hallions Blin-D and Baay Bia. Notably this event is happening in the heart of the community that hosts the largest Senegalese diaspora population outside of Europe.

Now I’m not one to draw lines between what is and what isn’t, but this convergence of global Hip-Hop upon the Biggie Apple in two very different contexts has got me thinking… (Warning! You now have all the information you need for the shows. If you don’t like thinking, stop reading now!)

In the United States, and particularly New York, Hip-Hop as a strict cultural form has aged. However, it’s still a new form, and the creative processes and technique innovations that it helped mold are still on the cutting edge of music production and sonic style. But the original practitioners of Hip-Hop are getting to a point where they’ve either been left behind in the past or have moved on. In the U.S., the torch has been passed (sometimes not so graciously) to a second and third generation, often removed from the geography of New York City, who continue to innovate and excite audiences, but not always in the ways that the originators envisioned. I would even go so far to say that New York Hip-Hop purists have co-opted the genre so much as to not allow the legibility of actual youth rebellion within the city’s own marginalized communities. This is why today I’m generally more a fan of digital music created in different regions around the world (including places like Chicago and New York) that don’t necessarily carry the Hip-Hop label, but yet are produced, disseminated, and practiced very much in the spirit of New York in the 1970′s.

However, in some places, especially those where young people have been standing up to aging leaders, often risking life and limb just to let it know that they are there, Hip-Hop is still legible as youth rebellion (even when it’s sponsored by the U.S. State Department). The more publicized cases of Tunisia, Senegal and Angola are not the only ones where youth music are taking a central role in the shaping of a vision for a new future. I’ve personally seen the impact that youth-fueled musical movements can have on a changing society in places as far removed from each other as Oakland and Monrovia. However, I would argue that today, more often than not Hip-Hop aesthetics are employed as a means of global legibility more than any desire to remain true to a purists’ definition.

It is this idea of global legibility that has allowed mainstream news publications to feature rappers at the center of political stories in Africa and the Middle East. As I listen to WNYC this morning, the celebration of youth voice on a mainstream news organization seems so unlikely when to think that Hip-Hop partly was birthed when young people felt like they weren’t being spoken to by mainstream radio. But that’s not really the issue here to me. My question is: what is really celebrated by mainstream institutions (sponsored by Bloomberg and Time Warner) when they are talking about and showcasing Hip-Hop? Is it the form? Is it that lyrical skill can now be recognized by middle-classed and/or middle-aged theater goers? And does this legibility of rebellion extend to an artist such as the Bay Area’s Lil’ B? What about Chief Keef? Or even Harlem’s A$AP Rocky? Is rebellion only okay when it’s safe, when it exists in far removed places where young people seem to represent the values that keep those middle class/agers safe in their social positions/homes/jobs/neighborhoods? And finally, how many people are going to the concert at BAM because they like Deeb’s, or Shadia Mansour’s, or El Général’s, or Amkoullel’s music?

I, for one, sometimes worry about too much agency given to Hip-Hop as a catalyst in these movements. I see it as more of a vessel, and conscious or explicitly political Hip-Hop, the form of expression most often associated with such rebellion, isn’t necessarily always the most impacting or important in a given context. Deeb himself has admitted that people in Egypt generally preferred pop music before the uprising, and only took on explicitly political music once the context of the uprising over took everyone’s lives. In post-revolutionary Cairo, 7a7a and Figo probably carry more populist zeal than any conscious rapper. And, unless we see various forms of expression as vessels for the agency of a people, an audience, a movement, how else could we explain the adaptation of the (Mad Decent version of the) Harlem Shake to the North African political landscape?

I’m sure many of these questions will be addressed this evening at BAM as my compañero, DJ Jace Claton/Rupture, will be moderating a talk with Deeb, Shadia Mansour, El Général, and Amkoullel. The talk starts at 7pm.

The New York Times: Counting bodies and column inches

Since Jeffrey Gettleman’s beloved machetes remain sheathed after a peaceful (and therefore thus far apparently uninteresting) Kenyan election, America’s paper of records put Africa’s other most important story on its front page yesterday. That’s right, Oscar and Reeva. It was a blockbuster, stretching from the front page (above to the fold) to occupy an entire page in the paper’s international section. Struck by its length, I went back to The New York Times’ archive to review the paper’s reporting about another killing in South Africa — that of 34 striking mine-workers, last August at Marikana. Reeva Steenkamp and Oscar Pistorius, in just this one article: about 2300 words. The 34 dead at Marikana, in the month after their murder by South African police, about 1,000 more. 30 days, 1,000 more words, 33 more bodies. It is hard to interpret this as anything other than rank racism. I do not wish to diminish Ms. Steenkamp’s death, but I think The Times’ own reporting reveals a great deal about the ‘meaning’ South Africans are supposedly seeking. Whether in South Africa or here in the U.S., we fixate on beautiful celebrities and their tragedies at the expense of reporting on the real, regular outrages that mark 21st century life. The Steenkamp/Pistorious saga is a soap opera – effervescent and ephemeral (even when it tells us a lot about domestic violence in South Africa), while the dead at Marikana were all too real victims of the multiple forces that shape life for so many of the world’s poor — migrant labor, globalized industry, criminally negligent police, a weak and incompetent state. Oscar and Reeva were glamorous, wealthy and white; we know their names and now have 2300 words more words about them. The dead at Marikana were none of those things, and in all of its reporting, this newspaper never bothered to tell us their names. (BTW, one mystery is why the paper brought former Johannesburg bureau chief Suzanne Daley to take the first byline on the story? Especially since the current Johannesburg bureau chief Lydia Polgreen is doing just fine. Anyone at The Times who can speak out of turn on that?)

Marcus Garvey’s Africa

Late last year I had the opportunity to review College of William and Mary History Professor Robert Vinson’s remarkable new book, The Americans Are Coming! Dreams of African American Liberation in Segregationist South Africa. Vinson details both physical and intellectual journeys between South Africa and the United States in the decades before apartheid. His characters are sailors and preachers, political leaders, teachers and conmen. His work reveals the intellectual history of the African diaspora during critical years that saw the tightening of white supremacy, massive dislocation and urbanization and remarkable political creativity in both the United States and South Africa. Over the course of February, Vinson and I exchanged emails about his book, beginning with a discussion about the man who was perhaps the era’s most important black political leader, Marcus Garvey.

How was Marcus Garvey important in African history?

Vinson: Marcus Garvey was important to African history in several ways. He led the largest black-led political movement in world history, and his movement’s “Africa for the Africans” slogan exemplified its primary mission of African politico-economic independence, black control of religious, educational and cultural institutions and an audacious worldview that linked the destinies of Africa and its diasporas. Of course, Garvey was part of a centuries-long history of diasporic blacks that sought re-connection with, and return to, the African continent. For continental Africans, Garveyism became a vehicle to express popular discontent with white rule, to animate and, in some cases, reinvigorate their political organizations, their trade unions, etc., to create and control black-led churches and schools and to spark a prophetic liberationist Christianity that placed godly black people at the center of a divinely-ordained historical drama that would lead to African redemption. It is so ironic that Garvey’s extensive travels throughout the Atlantic World did not include Africa (though it should be noted several colonial states in Africa banned him), since Garveyism became such a vital ideology that linked continental Africans with diasporic blacks as they constructed transnational racial identities in their attempts to eliminate the global color line. Garveyism was also an important bridge between the post-1890 African resistance movements and nascent Pan-African movements associated with diasporic blacks like Henry Sylvester Williams and the post World War Two anti-colonial and Pan-Africanist movements exemplified by future African leaders like Kwame Nkrumah, Nnamdi Azikiwe and Jomo Kenyatta, all of whom were influenced by Garvey and Garveyism in their respective youths. For historians of African history, Marcus Garvey and Garveyism illustrates how African history can be fruitfully studied beyond continental borders, how Africa and Africans should be more central in African Diaspora Studies and how African American and Caribbean history remained linked to African history long after the Atlantic Slave Trade.

It’s notable that Africanist scholarship has generally failed to note the vitality your book reveals, and that you’ve sketched here. Why do you think this is? And how do you explain the contrast with African American history, which, as Robin Kelley and others have long argued, has always been attuned to Atlantic crossings? Is this simply a matter of diaspora vs. homeland? Or does it speak to the political culture of African history and politics?

It’s notable that Africanist scholarship has generally failed to note the vitality your book reveals, and that you’ve sketched here. Why do you think this is? And how do you explain the contrast with African American history, which, as Robin Kelley and others have long argued, has always been attuned to Atlantic crossings? Is this simply a matter of diaspora vs. homeland? Or does it speak to the political culture of African history and politics?

On one level there is a diaspora vs. homeland dynamic at work here, complemented by, and related to, how the fields of African American history and African history have developed in the academy. In many ways, African American history has been informed and animated by centuries-long African American engagement with Africa. These include cultural, linguistic retentions, spiritual and naming practices, etc., the gradual transition from ethnic to racial identities and the making of a people known now as African Americans, the perpetual search for ancestral rootedness in Africa (including continual African American journeys to West African slave dungeons/castles) while buffeted about in an often hostile American homeland, back-to-Africa movements, and a general sense among some African Americans that the general fate of African Americans is tied in some fashion to the perceived state of Africa (oftentimes hostile whites justified slavery and Jim Crow by claiming blacks came from ‘barbaric’ Africa, are thus inferior and should be grateful to slaveholding/dominant whites for ‘civilizing’ them). Of course, Robin Kelley, Earl Lewis and others rightly pointed out in the 1990s that the then increasing interest in African Diasporas were part of a much longer popular and academic African American engagement with Africa (that included the work and practice of people like W.E.B. Du Bois, Carter Woodson, J.A. Rogers, Katherine Dunham, George Washington Williams, Lorenzo Turner, William Leo Hansberry, etc.) were attuned to African history, both on its own terms, and as an essential component to African American history, culture and politics. Garvey and others simultaneously exhorted diasporic blacks to lead the charge in ‘redeeming’ contemporary Africa, to restore the continent to its former glories. So, yes, Africa was central to the identity of diasporic blacks, particularly African Americans. Instead of being peripheral, inferior 2nd class citizens in hostile homelands, they were leaders of a divinely ordained mission to restore Africa to its former glories. Oftentimes, part of that mission involved actual return to Africa. In the 1950s and 1960s, African Americans reveled in the newly independent African nations; African independence helped fuel black freedom fighters, including King (his Birth of a New Nation speech after his return from Ghanaian independence celebrations is my favorite speech of his), Malcolm X (his African tours and the formation of his OAAU, patterned after the OAU), or those, like Pauli Murray, who offered tangible skills to the African nation-building project. African American multi-level engagement with Nyerere’s Tanzania and with anti-colonial and anti-apartheid movements in southern Africa also show that Africa has loomed large in African American consciousness than diasporic blacks in the consciousness of Africans in the era of the Atlantic Slave Trade. So all of this history has informed African American historical scholarship that has often been organically transnational (without using that trendy word) in outlook, particularly with Africa. It is why in the 1990s, I could go to Howard for graduate school to study Africa and the African Diaspora and African American history in an integrated, holistic way whereas at other schools that had a firmer sense of separation between Africa and other parts of the world, I would have been trained very well as an Africanist, and might have had African American history as a cursory secondary field, but l would have had to declare very clearly where my allegiances truly were-Africa or African American. Jim Campbell has talked about his graduate student days when senior scholars expressed incomprehension that he wanted to build a bridge between African and African American history. Fortunately for me, I studied with Joseph Harris, oft-cited as the godfather of modern African Diaspora studies, who himself had been a student of Hansberry’s. At Howard, an African American institution, there was a wide open space, resulting from all that I described above, that accepted as normal and natural that I would want to write integrated histories of Africa and Afro-America.

Conversely, I think African history/studies has been borne from experiences of continental Africans who had their own particular concerns in the Atlantic Slave Trade era that they often did not perceive as having direct connection with African Americans. Though continental Africans who lost loved ones in the Atlantic Slave Trade never forgot their kin, most of course could not know where those loved ones ended up, much less have a sense of the Americas and the people eventually known as African Americans. This is not to deny that some diasporic enslaved folk and their descendants did find their way back to the continent, helping to establish Liberia and Sierra Leone while others were engaged in Atlantic World Trade, etc., but it was not until the colonial period that there would be sustained African engagement with diasporic blacks, particularly African Americans. And even then, African kin, ethnic, local, or regional identities, their general political fortunes and their sense of rootedness were not tied to African Americans to the same extent that African Americans felt linked to Africa. Of course, as my work, and the work of others show, African identification with African Americans could be very strong — here too is the supreme importance of Garvey and the UNIA in fostering these linkages –, particularly as the 20th century progressed and African American cultural production and general achievement is beamed around the world in print media, oral transmission, film, television and other forms of mass entertainment. But Africa obviously is a huge continent that dwarfs the US and there are so many local, regional, national and continental issues that draw people’s attention. I understand some Africanists who resist the diasporic turn by noting correctly that Africa has such a varied and dynamic history on its own terms, that it remains understudied in its own right, and that funding, publications, and general institutional support should not be unduly influenced by the level of engagement with diasporic peoples. Nor should African Studies Centers find themselves competing for scarce funds with African American / African Diaspora / Africana programs that tend to elide Africa and Africans themselves.

Marcus Garvey-inspired IC Union (1920s Natal, South Africa)

The different levels of engagement of African Americans with Africans vis-a-vis African engagement with Africa is illustrated well in Saidiya Hartman’s book, Lose Your Mother. She discusses the coastal Ghanaians who were obviously aware of the streams of African Americans coming back to the slave dungeons, but she noted that many were puzzled by the desire to remember slavery or their slave histories. Some local Africans were alternately offended and amused by what they considered African American self-absorption and victimization when they — Africans — had very pressing immediate concerns and could not imagine having the material wealth needed to travel back across the Atlantic and stay in five star hotels.

Unlike the genesis of African American history, modern academic African historical scholarship derived largely from the works of early 20th century anthropologists, colonial officials and scholars of empire and colonialism, some of whom relied on collected oral histories of African peoples or travel narrative of European explorers, slave traders, missionaries, adventurers, etc. Most of this work was continental based. But as the vast post-1965 African Diaspora continues to fan out across the globe, the academics within this diasporic stream will lead the charge in placing Africa and Africans at the center of African Diasporic studies and placing African history in dynamic global contexts.

US-based Africans like Emmanuel Akyeampong and Paul Zeleza write extensively about the experiences of the post-1965 African diasporic communities outside of Africa. These scholars are obviously well placed to write about processes that reflect their own experiences-this personal interest animates their scholarly interests in ways very similar to African Americans writing about Africa. These scholars, defined by the processes of diaspora apparent in Atlantic Slave Trade diaspora, and aided by the hegemonic nature of the US, the US academy, and publishing industry, will be the vanguard of these new dynamic histories.

It’s remarkable the extent to which Garveyism was able to build these intellectual bridges across the Atlantic. How do you explain its apparent success? Was it a matter of context — it took root here, but not there? Or was it the content of Garvey’s (and others’) ideas? The confluence of events at the end of the 1910s and World War I?

Garveyism was successful because it was within a longer geneology of black-nationalist and Pan-African intellectual exchange, and organizational activity as well as a general black mobility around the Atlantic World, from enslaved people to labor migrants, to sailors, missionaries, students, entertainers etc. Garvey’s eloquent articulation of an African antiquity that disseminated ‘civilization’ beyond the African continent, his vision for a regenerated, redeemed independent Africa, and his claim that diasporic blacks, linked with western educated Africans, were a providentially designed liberationist vanguard, his fierce assertion that Egypt and biblical Ethiopia represented classical African antiquity, and his prophetic jeremiads that warned of an imminent apocalypse for white racists for their profoundly un-Christian behavior were familiar ideas for so many of his followers around the world. Most Garveyites had some familiarity with the ideas that became associated with Garveyism, particularly the emphasis on black psychological liberation as a necessary precursor racial advancement and the importance of building autonomous black religious, cultural, educational, fraternal, and socio-economic (particularly mutual aid) institutions. As Wilson Moses shows in much of his work, all of these ideas had circulated, albeit unevenly, around the black world. I am thinking now of David Walker’s Appeal, the prophetic religiosity (i.e. Nat Turner) and broad diasporic nature of slave revolts (i.e. Denmark Vesey), in Harriet Tubman leading hundreds of black out of slavery to the Promised Land, among Caribbean-born intellectuals like Edward Blyden and many diasporic religious leaders like Henry McNeal Turner, in the fierce anti-lynching campaigns of Ida Wells in the U.S. and England, in the pioneering Pan-African activity of the Trinidadian Henry Sylvester Williams and in the writings of West African intellectuals like James Africanus Horton and J. Casely Hayford.

So, it was the enduring attractiveness of these ideals, made more so by the many manifestations of brutal racism along the global color line, that is one factor in Garvey’s success.

A Garveyite family in Michigan, U.S. (1920s)

But there was something about Garvey himself that mattered — otherwise anyone else could have harnessed these same ideas to similar effect. Garvey’s unique genius was to take familiar ideas, and repackage them to fit the immediate post World War I world — and having the good sense to radicalize a rather staid initial UNIA program that centered on a Jamaica Tuskegee, and to instead build on the more aggressive political program of mentors like Hubert Harrison so that he and the UNIA became the political vanguard of the transnational New Negro movement. Garvey’s personal charisma, passionate oratory, visionary boldness, and unerring ability to articulate the deepest fears and highest aspirations of his listeners mattered. More so than anyone else of his era, he crystallized and channeled the frustrations, the despair, the anger and the dreams of so many blacks who had hoped that the close of World War I would usher in a more racially and economically egalitarian world, where American Jim Crowism and European colonialism in Africa and the Caribbean would end. That envisioned world had motivated many blacks to participate in the war effort. That envisioned world was one reason the Japanese pushed for a racial equality clause in the League of Nations charter. What the denial of that clause meant, what the continuance of European colonialism meant, what Red Summer and the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan meant to blacks was a firm denial of their individual and collective freedom dreams. So 1919, as Barbara Foley notes, was an explosive year and Garvey seized this moment better than any of his more learned and more experienced peers like W.E.B. Du Bois, Ida B. Wells and Hubert Harrison. With righteous indignation, he framed white supremacy in global terms and moved beyond the language of protest to be bold enough to offer an institutional solution to the global color line and the problem of presumed black inferiority.

An underrated quality of Garvey was his use of history, not just for his personal knowledge, but also for the projection of a usable past that provided context, lessons and inspiration to his followers. Because he had some sense of relevant historical precedents-including a fascination with the historical development of European empire-building — he used the language of nationalism, empire and racial destiny to imbue his movement with a sense of dynamic progress and promise that electrified his followers. He learned from his mentor Robert Love many things, but particularly the importance of printing a newspaper to disseminate his views widely and to use as a common site where his far-flung followers could be in conversation and collaboration. His multi-language Negro World traveled throughout the world particularly by black sailors, and young Africans memorized its contents and spread the word orally. Again, within the longstanding tradition of ships being central to back-to-Africa movements (i.e. Paul Cuffee, Chief Sam) the Black Star Line stood for a while as a powerful symbol of black economic power and as a tangible vehicle for diasporic blacks to return to and regenerate Africa. It failed, yes, but part of the reason it failed is because Garvey ordered the BSL ships to stop frequently in ports so that it could be the effective propaganda vehicle it was, to sell more stock, to enroll more members and to encourage the idea among many followers that Garvey was the new Moses primed to lead blacks to the Promised Land, either in Africa or in improved conditions in their respective homelands. Even as some followers melted away after the Black Star Line fiasco, Garvey’s conviction and jailing and the interminable UNIA infighting, Garvey intimate understanding of the importance of propaganda was part of his effective portrayal of himself as a Christ-like martyr; notions that his followers in particularly Central and Southern Africa came up with on their own as well. And even though Garvey was not as deeply religious as some of his followers, he adroitly understood the importance of religion, particularly biblical prophetic language and imagery, and the central place of African sites like Ethiopia and Egypt in the minds of so many blacks worldwide. This prophetic religiosity was another key component for bringing so many diverse constituencies in the black world under the broad Garvey/UNIA tent.

What do you want readers to take away from The Americans Are Coming!?

What do you want readers to take away from The Americans Are Coming!?

For one, that Garvey and the UNIA presided over the largest black-led movement in world history, bigger than the American Civil Rights movement. The book demonstrates the influence of African Americans and Caribbean peoples in energizing African politics, religions, trade unionism, education and print media AND the crucial facts that Africa was the primary site of the action and Africans were the active agents in adapting malleable Garveyist ideas to varied local contexts. The book places African, African American and Caribbean history in transnational contexts, seeks to re-center Africa and Africans in African Diaspora studies, and demonstrates that Garvey and Caribbean-born maritime communities in South African port cities were part of an important Caribbean diaspora as well. I hope readers see The Americans Are Coming! as a tangible example of truly transnational history that highlights the circulation and connection of people, ideas, institutions across national borders and thus moves beyond comparative history that often separates historical subjects in abstract parallel universes instead of in dynamic, interactive connection with each other.

I hope readers see the importance of Africa to Garvey and Garveyites. We see that importance, for example, in prophetic Garveyist thought, as in the Psalms 68:31 quote that appeared on the Negro World masthead, “Princes Shall Come Out of Egypt and Ethiopia Shall Stretch Forth Her Hands Unto God,” in the passionate assertions of ancient Egyptian and Ethiopian civilization, in the clarion calls for African redemption, the persistent attempts for diasporic re-settlement in Liberia and present-day Namibia and the vigorous and sustained correspondence between diasporic Garveyites and Africans. While many are aware of Garvey’s engagement with Liberia, I hope my book reminds us of Garvey’s extraordinary reach throughout the African continent, in southern Africa surely, but also throughout central Africa and East Africa as well. While it remains important to pay close attention to the rapidly shifting fortunes of the remarkable Garvey and the American UNIA, we can better appreciate the kaleidoscopic nature of the many articulated Garveyisms by looking carefully how Africans used Garveyism as a perceived common language to forge Pan-Africanist ties to diasporic blacks and to fight against a global color line, and also adapt Garveyist thought and action to local contexts. The Americans Are Coming! is part of a recent wave of exciting scholarship on the Garvey movement written by a newer generation of scholars like Claudrena Harold, Mary Rolinson, Ramla Bandele, Natanya Duncan, Adam Ewing, and others, but none of us could have done much without the foundational work and mentorship of pioneering Garvey scholars like Rupert Lewis, the recently deceased Tony Martin, and the incomparable Robert A. Hill, whose multi-volume Marcus Garvey and UNIA papers represents only a fraction of his global pursuit and collection of Garvey-related primary documents.

Do you see a role for Pan-Africanist ideas like Garvey’s today?

Yes, certainly. Just as Garvey drew upon pre-existing Pan-Africanist ideas to forge his UNIA, African anti-colonial leaders like Nkrumah, Azikiwe and Kenyatta drew inspiration from this Pan-Africanist geneology to help forge new African nation-states, which in turn inspired diasporic Pan-Africanists like Malcolm X. As you know in expert detail, Pan-African ideas animated both the South African anti-apartheid struggle and the global anti-apartheid movement. But Pan African ideas are particularly relevant today because many of the political, socio-economic, educational, penal, etc. conditions that have historically generated Pan-Africanist thought and action are still in existence. There is tremendous movement and interaction among diverse groups of black peoples today, from the post-1965 African diaspora, and the continuing Caribbean diaspora particularly to the United States and Europe, and a growing African American diaspora in Africa, all of which facilitates deeper interactions, connections (and conflicts) between diverse black peoples who often share, along with their many other identities, a heightened racial consciousness borne from broadly similar historical and contemporary experiences with various forms of white supremacy. Despite very demonstrable examples of black advancement and achievement, black institutions like my alma mater Howard, which has been such an important crossroads for black peoples worldwide, and as an incubator of Pan-Africanist thought, are struggling to stay afloat financially. In some ways, Howard is a metaphor for the black world; a symbol of black achievement and pride against the odds, but also reflective of the very fragile state of much of the black world today. True, the vast majority of the world is in struggle mode. But as long as black peoples collectively remain in such perilous conditions, and there remain substantive evidence that at least some of this fragility is due to historic and contemporary racial exclusion, discrimination, hostility and indifference, there will be a role for Pan-Africanist ideas as a generative ideology to seek the alleviation of these conditions on a global scale.

My Favorite Photographs N°14: Nancy Mteki

Our focus in the photography series turns this time to Nancy Mteki. Born a Zimbabwean, she started photography in 2008 at a South African local workshop called Iliso Labantu (The Eye of the People) founded by Alistair Berg and Sue Johnson. She first caught my attention when I came across her work as part of the “Pimp my Combi” exhibition at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe. I remember being fascinated with her ability to convey raw feelings of yet another everyday activity where women are consistently objectified and abused, all over the world … riding buses was never the same for me after that. Recently, Nancy was awarded a fellowship with a Scotland-based organization called Deveron Arts in Huntly. She will be part of a residency project under the theme of “Maternity” which will explore issues to do with young women’s experiences during pregnancy until the child is born. As part of our “favorite photographs” series, I asked Nancy to pick her 5 favorite shots, and share some words about how and where the images were made.

Our focus in the photography series turns this time to Nancy Mteki. Born a Zimbabwean, she started photography in 2008 at a South African local workshop called Iliso Labantu (The Eye of the People) founded by Alistair Berg and Sue Johnson. She first caught my attention when I came across her work as part of the “Pimp my Combi” exhibition at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe. I remember being fascinated with her ability to convey raw feelings of yet another everyday activity where women are consistently objectified and abused, all over the world … riding buses was never the same for me after that. Recently, Nancy was awarded a fellowship with a Scotland-based organization called Deveron Arts in Huntly. She will be part of a residency project under the theme of “Maternity” which will explore issues to do with young women’s experiences during pregnancy until the child is born. As part of our “favorite photographs” series, I asked Nancy to pick her 5 favorite shots, and share some words about how and where the images were made.

It was a rough and painful process choosing my five favorite photographs as I appreciate and admire all of them. The images I selected portray my history and background. I have never shared how I started out as a photographer hence I think this will be a great forum to do so.

I started photographing with a local South African group in Cape Town named Iliso Labantu Photographers in 2008. During that year, I took part in my first ever group exhibition during the 4th Cape Town Month of Photography. I learned from professional photographers that I met during the group’s meetings and started out taking pictures with a Pentax K1000 analogue. I recall initially placing my role of film the opposite way three times. I never gave up hope and kept trying until one of the photographers in the group taught me to how to use it. I also worked as a waitress back then, which allowed me to save and buy a new digital SLR camera — SONY A200 — a year later. In 2009 I exhibited my work at the Gwanza Zimbabwe Month of Photography. And in 2010 I took up a position at a local newspaper, NewsDay, in Zimbabwe.

These five photographs that I selected here are touching to me and led me to where I am as a photographer today.

The first image (above) was taken as part of a series called “Pimp my Kombi” — a series of images featuring an attractive young girl in an empty bus. In addition to the aesthetic and compositional research, these images explore the notion of public transport, as a social environment marked by gendered power relations in which the woman remains objectified. I was illustrating this by shooting this image showing an empty space through the sunglass. This was meant to express my feelings and to show that while it may be closed inside, there may be someone out there watching you.

The second image (below) I took when I was at a local market in Harare in 2010. When I saw this subject, I immediately knew there was a story behind it. This young man makes a living by selling anthill soil since he was a student and makes a living by selling it everyday to his community. The anthill is common in African societies and my hometown in Zimbabwe. This particular type of anthill soil is mostly eaten by pregnant women, many of whom say it tastes like chocolate.

The next image was taken during one of the workshop I attended as part of an assignment. It may sound weird but that person in the picture is my brother, Richmond. I recall when I was rushing out to attend a photography workshop, I saw him doing laundry and the sun was soft on his skin. With this light, I managed to document him doing his laundry, after which I left home to attend the workshop. This image won me a prize and reminds me of the day I captured it.

I took the following image when I was coming from an early photo shoot. I was really tired and rushing home to sleep. As I was walking by my grandmother’s house, I noticed a sunflower with little droplets of rain falling down; I was moved by it and started photographing. I love taking photos of daily life and whenever I see something that will be of interest, I capture it. This image brings happiness in my career because it was one my best shots when I started out taking photos:

And finally, I love taking photos of soccer action and being able to freeze motion during play. I remember in 2010 during the World Cup tournaments in South Africa that the Iliso Labantu Photographers group would go about documenting soccer in the local townships and exhibiting them. This piqued my interest in the subject. I photographed this image last year and it was published in a magazine in Zimbabwe. It was a very humbling and encouraging experience.

Kenya is More than its Election

The Kenyan people have voted. The Kenyan elections have come and not quite gone. The foreign press offered its readers a veritable smorgasbord of dreadfully decontextualized representations, and now that the actual polling has passed, you can just about taste the collective disappointment at the absence of spectacular violence. As the local Kenyan press noted, the reporting was shameful, the reporters were infested with clichés. The results are coming in, and it doesn’t look like Martha Karua, the steely women’s rights activist and advocate, won the Presidency, but then she wasn’t meant to. At least not this go-round.

The Kenyan people have voted. The Kenyan elections have come and not quite gone. The foreign press offered its readers a veritable smorgasbord of dreadfully decontextualized representations, and now that the actual polling has passed, you can just about taste the collective disappointment at the absence of spectacular violence. As the local Kenyan press noted, the reporting was shameful, the reporters were infested with clichés. The results are coming in, and it doesn’t look like Martha Karua, the steely women’s rights activist and advocate, won the Presidency, but then she wasn’t meant to. At least not this go-round.

On the other hand, her campaign helped put the issue of women in electoral politics, from local to national, not so much on the front burner as at least in the house. More formal attention was paid to the ways in which women candidates, and party members more generally, suffered discrimination and coercion. Contrary to much of the foreign coverage of the elections, this attention didn’t come out of some panic that began in the 2007 post-election violence, but rather from women’s organizing histories. Longstanding groups such as ACORD Kenya, the Rural Women Peace Link, the Coalition on Violence Against Women, and so many others, have been working tirelessly, every single day, for years. And they continue to do so.

So Martha Karua didn’t win the Presidency, but Mary Wambui won the Othaya parliamentary seat. Alice Wambui Ng’ang’a “scooped” the election and became the first woman MP elected to represent the new Thika constituency. Cecily Mbarire seems ready to break a seesaw curse by being the first in thirty years to be re-elected from Runyenjes.

But those who rely on the international press are still left wondering if Kenya is more than an election. Here’s one very partial contextual sliver of a response.

Remember the violence? Not the election violence. The food riots of 2008. When the price of food in Kenya, as around the world, doubled in less than 12 months, Kenyan women joined their sisters around the world and led the nation into extended food uprisings. As Njoki Njoroge Njehu, of the Daughters of Mumbi Global Resource Centre, recently noted: “Corporations were speculating on food and made a lot of money. But it was done at the expense of ordinary people in Kenya, in Mexico, in Argentina and other places where there were food riots.” That’s the story. Ordinary women everywhere always lead food riots and uprisings.

In Kenya recently as in so many other places, “poverty … in most cases wears a feminine face.” Why are women at the center of Kenyan movements for social transformation? One reason is that the last decades in Kenya have seen an intensification of the immiseration of women: “wage employment away from home, forced or voluntary migrations or resettlements, changing decision making patterns in the political and socio-economic settings; reconstructed family and household structures; child rearing habits and the recycling of geriatric parenting; escalating rates of young widowhood; increase in family conflicts; breakage and general lack in socio-cultural-support-systems due to urbanization; social risks as manifested in increased illnesses … due to the ravages of HIV/AIDS. It is indeed a vicious cycle.”

A vicious cycle, and familiar. As Naomi L. Shitemi explains, it’s “modern life.” Women have been organizing to address and transform “modern life” in Kenya. For example, for decades, women struggled to develop some sort of national approach to land tenure, and now there is a Kenya National Land Policy that has problems, certainly in implementation, but also provides a framework. There’s the work of Wangari Maathai and all the women who made her work possible and concrete.

There’s the work that was begun in Nairobi, in 1988, in response to the 1978 Alma-Ata Declaration of Health for All. In 1988, women from around the world met in Nairobi and launched the Safe Motherhood movement, and it has been growing, and learning, and growing some more ever since. In Kenya, and around the world. As Kenyan women’s and public health advocate and activist, and professor, Miriam Were noted, “We need not wait for findings from some mysterious research.”

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers