Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 484

March 14, 2013

Your Camera is Not a Toy: Photographing “Children From Around the World”

In 1995 Dorling Kinderlsey published a book, Children Just Like Us, sponsored by UNICEF, which brought pictures of children from “all over the world” into the sheets between our fingers, complete with facts and direct quotations. The book feels friendly, ecumenical: children certainly have some funny habits and names, but underneath, of course, they are all alike! I wonder what effect these kind of books, which make faraway places and different cultures specularly available to Western children, have on the children who read them. Do they give those children a harmless, cosmopolitan, global outlook? Pseudo-anthropological ambitions, to travel, to see and know the world as benevolently different as it was promised? Or does it offer the Western child a dangerous sense of superiority? The cause of these thoughts are a photo-series of children with their toys, by an Italian photographer, Gabriele Galimberti.

In 1995 Dorling Kinderlsey published a book, Children Just Like Us, sponsored by UNICEF, which brought pictures of children from “all over the world” into the sheets between our fingers, complete with facts and direct quotations. The book feels friendly, ecumenical: children certainly have some funny habits and names, but underneath, of course, they are all alike! I wonder what effect these kind of books, which make faraway places and different cultures specularly available to Western children, have on the children who read them. Do they give those children a harmless, cosmopolitan, global outlook? Pseudo-anthropological ambitions, to travel, to see and know the world as benevolently different as it was promised? Or does it offer the Western child a dangerous sense of superiority? The cause of these thoughts are a photo-series of children with their toys, by an Italian photographer, Gabriele Galimberti.

“Every time he flew to some place foreign for his work, he’d find a local family and children happy to show him some of their favorite toys.” (PRI’s The World)

It sounds like happy work, traveling and taking photos of happy children with the happy consent of their happy families; Journalists have been eager to write about this work, which is so colourful and positive but also serious and thought-provoking, and many have used the opportunity to reflect uncritically on their own childhood possessions.

In the most recent (and probably most shared) Feature Shoot post on Galimberti’s photographs (that’s him with his favorite toys all neatly laid out in the photo above), the leading image is that of a young child named Chiwa from Mchinji in Malawi.

In the most recent (and probably most shared) Feature Shoot post on Galimberti’s photographs (that’s him with his favorite toys all neatly laid out in the photo above), the leading image is that of a young child named Chiwa from Mchinji in Malawi.

I don’t want to describe the image – which takes its aesthetic of deprivation from charities and development organizations. Suffice to say, it’s the image at the top of this post. What seems more important is questioning the motivations and effects that this series – and the countless others like it, by “photojournalists,” trawling the world’s surface for their wage labour – has on its viewers and its subjects.

There is a kind of knee-jerk response to my concerns: that representations like these have positive, moral benefits: we become more aware of the lives of others in this world which we can’t help – thanks to environmental crises, trade, war, etc. – but share with everyone else in it, that this awareness, of complicity, is served by photographic representations of other places. That forgets the importance of attending to how these representations are made – and how they are used.

Let’s look carefully at the Feature Shoot article:

‘Galimberti explores the universality of being a kid amidst the diversity of the countless corners of the world; saying, “at their age, they are pretty all much the same; they just want to play.”’

The colloquial “universality of being a kid” is, of course, the journalist’s own journalistic prose, and the photographer can’t be held responsible for the incompetent idea of the complex problems of thinking ‘universally’. A piece on the series from The Times magazine rehearses the same platitudes about how toys tell you “everything you need to know about the universe kids inhabit”. The problem here is not ‘diversity’, but – just like the Dorling Kindersley book – assertions of similarity. They’re all just kids, right?

What is so persistently troubling about the kind of photojournalism which wins hearts and competitions from Western and cosmopolitan bodies is that the projects which win are frequently disguised by a kind of pseudo-anthropological discourse. See here, again from Feature Shoot:

“Galimberti found that children in richer countries were more possessive with their toys and that it took time before they allowed him to play with them (which is what he would do pre-shoot before arranging the toys), whereas in poorer countries he found it much easier to quickly interact, even if there were just two or three toys between them.”

It is important to note that the photographer himself arranged the toys. Forgetting the mountains of material by psychoanalysts or anthropologists which says that the person (or people) who are the subject of study should be approached on their own terms. Here the photographer arranges the toys, and the child, for the most perfect composition. James Mollison’s recent series on childrens rights, Where Children Sleep, and Mary Beth Meehan’s images of undocumented migrants, are both bodies of work which demonstrate a carefulness in encountering the photographic subject which is absent in these confrontations.

If some of the children know what to do for the camera and are smiling, the ones who look mournful or uncertain at why this strange man is pointing something at them, their toys – objects of intimate and complex relations – placed in strange new formations. The resistance to the photographer’s intentions, his invasion of private space, is the most valuable accident of this project, and the real source of difference.

What real difference is this series making manifest? The journalist recalls that the photographer recalls something vague about what the children did, making distinctions between rich countries and poor countries (which is, perhaps, forgetting that there are poor kids in rich countries, or vice versa).

“There were similarites too, especially in the functional and protective powers the toys represented for their proud owners. Across borders, the toys were reflective of the world each child was born into—economic status and daily life affecting the types of toys children found interest in. Toy Stories doesn’t just appeal in its cheerful demeanor, but it really becomes quite the anthropological study.” (Feature Shoot)

Quite the anthropological study! This phrase is exactly what a parent might patronisingly have said on finding their child looking at the Dorling Kindersley book. In this instance it is appropriately patronising: anthropology as a professional discipline has rigorous and necessary ways of thinking the problems of inter-cultural encounters, of thinking universally about education and commodification, subjectivity and difference, photojournalism like this seems governed, worryingly enough, by misguided and dangerous kind of good intentions.

The images of unsmiling children, looking back at the strange man who has entered into the private space of their fragile and critical object relations, remind us that the moralising gaze of the camera is not a disinterested thing. We might work harder to remember whose interests these cameras serve. What the photographer ultimately found (and was perhaps looking for all along) was a mirror on his own experience: telling the Times journalist, “It was nice to go back to my childhood somehow.” Adulthood must be a sad state to be in if you have to point a camera at a child when all you really want to do is play with them.

Introducing Malitia Malimob: Rap music and the less glamorous stories of African migration to the United States

The new “Africa Rising” narrative propagated largely by a globally-connected middle and upper class diaspora, often obscures the grittier stories of the African immigrant experience. This is partly due to an instinct among African immigrants to want to counter the history of one-dimensional and negative portrayals of both Africa and immigrants in the mainstream Western media. While it’s understandable that they’d want to shy away from being associated with crime, fraud, war, lack of employment, social welfare, or some other scourge that the West associates with immigrants and Africa, the struggle that most Africans immigrants go through is real, and sometimes the less glamorous stories of global migration are the ones that most need to be told:

The new “Africa Rising” narrative propagated largely by a globally-connected middle and upper class diaspora, often obscures the grittier stories of the African immigrant experience. This is partly due to an instinct among African immigrants to want to counter the history of one-dimensional and negative portrayals of both Africa and immigrants in the mainstream Western media. While it’s understandable that they’d want to shy away from being associated with crime, fraud, war, lack of employment, social welfare, or some other scourge that the West associates with immigrants and Africa, the struggle that most Africans immigrants go through is real, and sometimes the less glamorous stories of global migration are the ones that most need to be told:

Malitia Malimob, comprised of two twenty-something Somali immigrant youth living in Seattle, are a Rap group that both represent for their community, and manage to expose the less glamorous side of immigrant survival in America. Fleeing their war-torn homeland as children, the two made their way to Kenya and eventually found themselves settling down in one of Seattle’s rougher neighborhoods. Beyond these general facts, their public biography is pretty thin, but this is where their music, and the little I know about the recent history of the Somali diaspora starts to fill in the blanks.

The Somali community in North America is concentrated in seemingly unlikely locales like Minnesota, Ohio, or Maine. There is also a significant population in Ontario, Canada. Whenever I tell people about the Somali community in Minneapolis, the reaction is always along the lines of, “how did they end up there?” Regardless of the circumstances behind their settling in any one place (refugee resettlement policy or migrants settling in places where there’s already a community presence), I would argue — as I have before – that such communities add a much needed diversity and a wealth of culture to places that would otherwise be cut off from the realities of a globalizing world.

However, as the majority of Somali immigrants have arrived only since the 1990′s, and remain concentrated in ethnic enclaves, as a community they are still finding their footing in North American society. When I visited Toronto last summer, I was told that the highest gang activity in that city was amongst Somali youth. Growing up in the American Midwest, I was aware that the same association between Somali youth and gang violence exists in Minneapolis. What these rumors and reputations signify is that various places have simultaneously developed a distrust of their local Somali community, signaling a general stigma attached to the community contributing to their social marginalization. Add to that the fact they make up significant proportion of the black population in some of the places they have settled, and the community perhaps ends up having to stand in as targets for the latent forms of American racism that may persist there. Besides North America, tensions persist between the Somali and the local community in places like Nairobi as well. This is partly due to that city’s proximity to Somalia, and the fact that its civil war has had a significant effect on the East African region.

As if facing stigma in their local communities wasn’t enough for the Somali diaspora, they have also had to face a persistent demonization in the international media. In the news, Somalia is consistently portrayed as a backwards and lawless place that is a breeding ground for threats to the rest of the world (Western capitalism), such as islamic militancy and piracy. This reputation extends far beyond any of the places where Somalis actually live. The situation for the diaspora becomes even worse when this global fear gets transplanted and fused back onto the already existing stigma associated with them in their local communities.

A few years ago, several Minneapolis born Somali youth disappeared, and were found to have been recruited to join the ranks of Al-Shabaab, a militant Islamic group back in Somalia. Perhaps disillusioned by their continued marginalization in Minnesotan society, these American-born youth decided to abandon the American Dream and go do something for their homeland. At a youth development conference a few years ago, one community worker from that neighborhood told me that the FBI subsequently swarmed upon the Somali neighborhood in central Minneapolis, and the tight-knit community was being watched by the highest concentration of agents in the country.

The perpetual marginalization of these youth in their local context is most likely a factor in their ability to be recruited into the Al-Shabaab network. However, the American fear of domestic radicalization that such stories bring out is perhaps just a fundamental misunderstanding of the role informal networks play in constructing Somali culture, society, and national identity. (Read this post by Mats Utas for an intriguing illustration of this point.) Al-Shabaab is only one of many of the networks that hold the Somali diaspora together. Even while dispersed across the globe, the diaspora remains tightly-knit and are highly connected to home. Informal networks of business, communications, and finance retain central importance in Somali culture, and serves as a means of retaining a sense of cohesion in the face of so much displacement. In Utas’ introduction to the book African Conflicts and Informal Power: Big Men and Networks, he mentions that the strong informal network of finance in the diaspora allowed the Somali currency to retain its value on the international market, while the state itself was disintegrating.

Somali rapper K’naan has attempted to address the demonization of that other Somali network that seems to come up a lot in the international media: piracy. Throughout the course of several interviews, K’naan has attempted to debunk some of the myths surrounding piracy in the Indian Ocean, and shed some light on the motivation behind it. He claims that he’s with the pirates because they are just coastal fisherman who’ve had to turn to alternative means to provide for their communities after their livelihoods were destroyed by overfishing from international fleets. But for rap MC’s Malitia Malimob, the pirate label hits home in ways beyond just a theoretical engagement with the issue. It was those same Somali fisherman who saved one of the rappers during the war, and ferried him off to safety in Kenya.

The music Malitia Malimob make reflect all these social realities. It takes on the role of social criticism in that it brings to the forefront the global marginalization of the Somali people, and the limits of the American Dream. At the same time, their music serves as a galvanizing force for pride amongst Somali youth. With 50,000 views and only comments of praise from fans on a self-released YouTube video, the group have obviously touched a nerve amongst their peers.

Connections through informal networks to pirates and Islamic militants get channeled through a sonic palette that will inevitably be characterized as Gangsta Rap. And, this is what sets them apart from their countryman K’naan. Their latest EP, the Idi Amin Project (produced by Tendai from Shabazz Palaces), takes its cues from the West Coast Hip-Hop tradition with Seattle falling underneath the sphere of influence of the nearby Northern and Southern California scenes. This makes them part of a lineage that connects them directly to Gangsta Rap legends such as N.W.A., Too $hort, and E-40. But, the Malimob also engage sonically with neo-Gangsta Rap acts like Chief Keef and Waka Flocka Flame. However, instead of only talking about the highs and lows of life in an American ghetto, Malimob add elements of a people displaced by war, a disintegration of the formal state, and those underground networks that are portrayed as globally threatening in the mainstream media. (Interestingly Malitia Malimob aren’t the first African immigrant rappers in America to make Gangsta Rap. Mainstream rappers French Montana and Wale are two notable examples of predecessors. But, if they are able to reach the heights that those two were able to reach, they will definitely be the first to do so by tying their tough image to a distinct national identity.)

As Malimob’s profile grows, their rebellious spirit, and their appropriation of American gangster aesthetics may ruffle a few feathers. Mainstream American audiences in particular might not know what to do with African Gangsta Rap. In his essay ‘Of Mimicry and Membership,’ Stanford University’s James Ferguson describes a moment of embarrassment that mid-20th Century anthropologists faced when the natives imitated Western culture. Ferguson places this reaction in our contemporary moment and seeks to deconstruct this as a distinctly privileged reaction to the cultural production of a group of people who would otherwise be cast as exotic other. I take Ferguson’s ideas to mean that the moment of embarrassment really should serve as a mirror rather than a judgement call. I believe that Malitia Malimob’s music is a perfect example of Ferguson’s idea of Africans’ engagement with notions of global membership. They re-appropriate the pirate and Islamic militant images propagated in the media, and turn their outsider social standing into a form of empowerment by channeling the aesthetics of the art form that their Black American predecessors innovated a generation before.

Another group that the Malimob may have to face criticism from is the elders in their own community. In the United States, elder members of immigrant communities tend to look down on those youth members of the community who become too Americanized, especially those who find themselves entangled with the less savory sub-sections of American society. For elder members of African immigrant communities, the biggest source of embarrassment are those youth who take on attributes of Black American culture up to the point where they “loose their own culture” and their African-ness becomes unrecognizable. Assimilating racist notions of the place of Black Americans in American society, there is a strange contradiction in conservative new arrival African immigrants’ judgements of Black Americans. They end up thinking that the new generations of youth assimilate the wrong aspects of American society, and are in danger to end up just becoming one of them. But more often than not, those who deride this form of assimilation don’t understand the modes of survival and inventiveness that such a social strategy signifies.

In the end, perhaps this really is the story of Africa rising. If the Malimob can find success in their careers in many ways they will embody the American Dream, surpassing the limits set for their community. My real concern then, would be if Malitia Malimob received critical praise too quickly. A non-self-reflective praise for Malimob from music writers will have the danger of trivializing Somali realities in America, much like what happened recently with the violence on the South Side of Chicago. Inevitably they will have to deal with the fact that Gangsta Rap, black violence, and the public expression of black sexuality in America, formerly a form of expression that gave voice and visibility to the marginalized minority populations, is now fully acceptable as a commodity for consumption by the privileged.

The Malitia Malimob will be on tour in the U.S. with Shabazz Palaces and Thee Satisfaction this Spring. I’ll be playing with them as part of a Dutty Artz showcase in Seattle on April 3rd. Look out for news on a collaboration between the Malimob and myself soon. For some more on Somali Gangsta/Pirate Rap, read Johan’s piece on this site, and check out these artists’ videos:

Assault:

Kay:

Kenya: The monster under the house

Guest Post by Patrick Gathara

At the end of my first term in high school, I watched a screening of Steven Spielberg’s Poltergeist, the tale of an ordinary family unknowingly living in a house built over a graveyard without the bother of moving the bodies. Of course, this does not go down well with the spirits of the dead, who make their displeasure known by slowly torturing the family into madness. In one of the scenes, a man stares in horror at a mirror as fingers tear away at his reflection’s decomposing face till it falls into the bathroom sink. Needless to say, I have never looked at bathroom mirrors in quite the same way since. Last week, it was Kenya’s turn to look into the mirror.

Elections provide opportunities for national self-examination and renewal, for the country to take a long, hard look at itself, assess it achievements, reorient its priorities. However, like I have done too many times since I watched that movie, we chose to turn away, afraid of what we might see.

Fear can make people do strange things.

We had already normalized the abnormal, making it seem perfectly acceptable to have two ICC-indicted politicians on the ballot. At the first presidential debate, moderator Linus Kaikai had been more concerned with how Uhuru Kenyatta would “govern if elected president and at the same time attend trial as a crimes against humanity subject” and not whether he should be running at all. Any suggestion of consequences for Uhuru’s and William Ruto’s candidature had been rebuffed with allegations of neo-colonialism, interference and an implied racism. People who had spent their adult lives fighting for Kenyans’ justice and human rights were vilified as stooges for the imperialistic West for suggesting that the duo should first clear their names before running for the highest office in the land.

As the elections approached we were assailed with unceasing calls for peace and appeals to a nationalism we knew to be to all too elusive. We voted and celebrated our patience and patriotism, brandishing purple fingers as medals for enduring the long queues. And we heaved a collective sigh of relief when it was all over. We afterwards wore our devotion to Kenya on our sleeves and on our Facebook pages and Twitter icons even as we were presented with the evidence of our parochial and tribal voting patterns which fulfilled Mutahi Ngunyi’s now prophetic Tyranny of Numbers.

By now, a compact had developed between the media and the public. Kenya would have a peaceful and credible poll no matter what. The narrative would be propagated by a few privileged voices and it would countenance no challenge. The media would sooth our dangerous passions with 24-hour entertainment shows masquerading as election coverage. We would laugh the uncomfortable laughs, and plead and pray that politicians would not awaken the monster we recognised in each other. Let sleeping ogres lie, seemed to be the national motto. Meanwhile, those who could stocked up on canned food and filled up the fridges and stayed away from work. As food prices quadrupled we desperately clung to the belief that all would be well if we kept our end of the bargain and didn’t ask uncomfortable questions.

When nearly all the measures the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission deployed to ensure transparency during the election failed, this was not allowed to intrude into the reverie. Instead the media continued to put on a show and we applauded them for it. Uncomfortable moments were photoshopped out of the familial picture. Foreign correspondents who dared to question our commitment to peace were publicly humiliated and had their integrity impugned. I played my part in this. When the New York Times dared to suggest that if Raila Odinga contested the outcome “many fear [it] could lead to the…violence that erupted in 2007 court challenge,” it didn’t take long for the reactions to come. “Foreign press haven’t given up [on the possibility of violence],” I tweeted. Others quickly joined in, some suggesting that the writer was stuck in 2007.

However, if we are honest, it is us who were stuck in the narratives born of the last five years. It was not, as suggested by the New York Times in a later piece, a renewed self confidence that drove us. Quite the opposite. It was a fear, a terror, a recognition that we were not as mature as we were claiming to be; that underneath our veneer of civility lay an unspeakable horror just waiting to break out and devour our children. We were afraid to look into the mirror lest our face fall in the sink.

It is said that truth is the first casualty of war. In this case the war was internal, hidden from all prying eyes. Who cares about the veracity of the poll result? So what if not all votes were counted? We had peace. “The peace lobotomy,” one tweet called it. “Disconnect brain, don’t ask questions, don’t criticize. Just nod quietly.”

Yet we should care. Our terror and the frantic attempts to mask it were a terrible indictment. As another tweet put it, it “reveals how hollow the transformation wrought by the new constitution.” Instead of being a moment for national introspection, the election had become something to be endured. The IEBC was expected to provide a quick fix to help us through it but was never meant to expose the deeper malady of fear, violence and mistrust which we have spent five years trying to paper over with our constitutions and coalitions and MoUs and codes of conduct. The fact is we do not believe the words in those documents, the narratives inscribed on paper but not in our hearts. And this is why we do not care whether an election springing from them documents is itself a credible exercise.

What maturity is this that trembles at the first sign of disagreement or challenge? What peace lives in the perpetual shadow of a self-annihilating violence?

Cowards die many times before their deaths and we have been granted a new lease of life. However, if we carry on as we have done over the last five years, if we continue to lack the courage to exhume the bodies and clean out the foundations of our nationhood, we shouldn’t be surprised if in 2017 we are still terrified by the monsters under the house.

* Patrick Gathara is a political cartoonist and blogger.

Dutch artist Ruud van Empel talks about his art, including how to portray black children

About a month ago, we came across the ‘World’ series by Dutch photographer Ruud van Empel. Initially, his art stood out because of the ‘race’ and age of his models, the majority of whom are black children. Since the artist, as we soon learned, grew up in a small and rather homogeneously white southern Dutch town, it seemed unlikely that this apparent preference simply occurred by chance. But it wasn’t just the race factor that got us interested in asking Ruud some questions about his models. There was something odd about the entire style, demeanor and surroundings of these kids. Almost all of them are exquisitely groomed in what looks like Dutch middle-class attire from the 60s and surrounded by an almost perfect scene of tropical nature; quite a wondrous contrast in itself. On top of that, all these different forests seem to breathe a peculiar sort of ambiance. Perfectly ordered yet sinister, the lakes, trees and leafs are inviting and foreboding at the same time. The children don’t seem to be intimidated by it, though. They look at you with eyes wide open. Bold. Innocent. Confident. But there’s something uncanny about their look. Their innocence seems tainted. The reason for this oddness, we soon find out, is because we are looking in the eyes of people who don’t exist and never have. Instead, they are photoshopped into being through a patchwork of noses, arms, eyes and lips.

About a month ago, we came across the ‘World’ series by Dutch photographer Ruud van Empel. Initially, his art stood out because of the ‘race’ and age of his models, the majority of whom are black children. Since the artist, as we soon learned, grew up in a small and rather homogeneously white southern Dutch town, it seemed unlikely that this apparent preference simply occurred by chance. But it wasn’t just the race factor that got us interested in asking Ruud some questions about his models. There was something odd about the entire style, demeanor and surroundings of these kids. Almost all of them are exquisitely groomed in what looks like Dutch middle-class attire from the 60s and surrounded by an almost perfect scene of tropical nature; quite a wondrous contrast in itself. On top of that, all these different forests seem to breathe a peculiar sort of ambiance. Perfectly ordered yet sinister, the lakes, trees and leafs are inviting and foreboding at the same time. The children don’t seem to be intimidated by it, though. They look at you with eyes wide open. Bold. Innocent. Confident. But there’s something uncanny about their look. Their innocence seems tainted. The reason for this oddness, we soon find out, is because we are looking in the eyes of people who don’t exist and never have. Instead, they are photoshopped into being through a patchwork of noses, arms, eyes and lips.

This is how the artist goes about creating these images: First he collects all the features he needs by shooting a variety of young models in his studio and by subsequently wandering through Dutch forests, in search of fine leafs, perfect branches and the right waters. Only to tear it apart and spend weeks reconstructing it all until both the person and the setting match his desired standard of photo-realism. He calls it digital collage. If we are to believe Elton John, who as a fan even dedicated a song to Ruud during a concert, his techniques represent what much of modern photography will grow into in the 21st century. His work also deeply impressed the director of San Diego’s Museum of Photographic Art, Deborah Klochko. Intrigued by “all the little secrets in his work,” she exhibited his work in 2012.

This is how the artist goes about creating these images: First he collects all the features he needs by shooting a variety of young models in his studio and by subsequently wandering through Dutch forests, in search of fine leafs, perfect branches and the right waters. Only to tear it apart and spend weeks reconstructing it all until both the person and the setting match his desired standard of photo-realism. He calls it digital collage. If we are to believe Elton John, who as a fan even dedicated a song to Ruud during a concert, his techniques represent what much of modern photography will grow into in the 21st century. His work also deeply impressed the director of San Diego’s Museum of Photographic Art, Deborah Klochko. Intrigued by “all the little secrets in his work,” she exhibited his work in 2012.

Having worked on it since he graduated from the Sint Joost Academy of Fine Arts in Breda in 1981, his style of magic realism did not develop overnight, nor did it take off easily in The Netherlands. Outside of the confines of the Lowlands, however, his skills found widespread appreciation. In the last ten years alone, Ruud exhibited his works in places like Bejing, Barcelona, Tokyo, Seoul, Tel Aviv and New York City. The United States proved to be a particularly keen admirer.

So we decided to ask him some questions about his work.

Childhood and innocence seem central themes in your work. Can you tell us why?

The first large work that I made with a young girl in it was in 2003 and was titled Study In Green#2. It shows a puppet-like girl in a red dress. She is alone in the forest. It was an idea that I had had for over twenty years, so in 2003 I decided to finally make it. The idea was to do something with beauty. Beauty has been a taboo in Art for such a long time; I didn’t feel like making something that might look very artistic but in fact was ugly. To me, both nature and the innocence of children is something beautiful. Children are born innocent into a cruel and dangerous world. I wanted to do something with that idea. So I gave the girl puppet-like eyes to make her innocence come off even stronger and gave her an almost fairytale kind of forest. But as an effect of the photomontage-technique it ended up looking strange and somewhat frightening. I liked this and decided to explore it further.

Many of the children in your works are black. How did this choice come about?

Many of the children in your works are black. How did this choice come about?

I grew up in a small Catholic town in the south of the Netherlands. There was only one black boy in my primary school class. In the portrait Generation 1 (above) I expressed this situation. It shows a white class with just one black pupil. With World#1 I decided to work with more black children. It set off a whole new series of work. First I thought of portraying a girl in a dirty, old and torn-up dress, as if she were very poor. I suppose this idea popped up in my head because of the image we Westerners are often given. I didn’t really like that idea though, and decided to give them the clothes my generation wore when we were kids, especially because those clothes looked very innocent to me. Later, in 2007, the art historian Jan Baptist Bedaux told me this was the first time a black kid was portrayed as a symbol for innocence in Western Art. He wrote:

The fact that many of the children in his compositions have a dark skin is a facet that cannot remain without comment. Although it is self-evident that a child’s skin colour is not important, the iconography of the innocent child was traditionally represented by ‘white’ children. The earliest examples of this date from the early seventeenth century. These are portraits in which children are captured in an idealized, pastoral setting. It is a genre to which the children’s portraits of the German artist Otto Dix, a source of inspiration to van Empel, refer. In deviating from the standard iconography by giving the child a dark skin, Van Empel inadvertently assumes a political stance. After all, this child is still the focus of discrimination and its innocence is not recognized by everyone as being self-evident. The most pregnant image from this World series is undoubtedly the one of the girl whose black skin contrasts sharply with the dazzling white of her dress.

How do your photoshopped representations relate to the ways Dutch media present black children?

How do your photoshopped representations relate to the ways Dutch media present black children?

Dutch media often show black children as sick, poor or starving. I suppose it works, and helps to raise money. It is an image that appeals to many people. Nobody wants to see a lovely young baby starving to death. Media are very simple, the strongest image is the one they’ll use to get their message across. I guess Dutch media are no different from most other countries in this pattern.

What, if any, is your relationship with the African continent? And can you tell us more about this picture of a photo class in Kigali, where Rwandan pupils are looking at your work?

I don’t have a special relationship with the African continent. I have only been to Egypt and Tunisia, but I would definitely love to visit more African countries. The photo you refer to is called ‘looking at Ruud van Empel in Kigali’ and shows a group of learners discussing my work during a photo class. I felt incredibly proud when I found out about this class. I received quite some positive responses from black audiences, who said they liked the way my work portrays black children in a respectful and beautiful way rather than as a victim.

Can we expect you or your work in Africa in 2013?

I am afraid I will not be visiting the African continent yet. First I have an exhibition at Fotografiska, Stockholm, Sweden — “Pictures don’t Lie” from 7 March until the 2nd of June. After that I will exhibit at the Fotomuseum in Antwerp, Belgium. The solo exhibition “Ruud van Empel” is curated by Joachim Naudts and runs from June 28 until October 6.

For more information on Ruud, his work and upcoming exhibitions, visit his website.

For more information on Ruud, his work and upcoming exhibitions, visit his website.

March 13, 2013

The Blue Kenyan

We may not all love Chelsea Football Club (John Terry, their klepto-petro-billionaire owner, John Terry, the list goes on) but we are loving the team’s Brazilian midfielder Ramires right now. And not just for that equalizing goal he scored on Saturday against Manchester United in the English FA Cup. When Ramires played for Cruzeiro in Brasil, fans of Os Celestes (who play in blue) nicknamed him “O Queniano Azul” or the “The Blue Kenyan” because his extraordinary stamina reminded them of Kenyan distance runners.

A Brazilian TV channel went and did a long feature on Ramires’ life in London after he scored a brilliant lob at the Nou Camp last season. One for the Portuguese speakers, or for anyone who wants to see Ramires and his wife chasing their young son around their house before inexplicably heading to a posh ice bar in London to finish the interview. He seems like a nice fella.

The Voortrekker Monument and “the many mistakes” of the Afrikaner past

Guest Post by Alex Lichtenstein

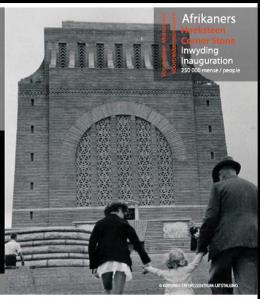

On a recent trip to South Africa, I managed to fit in a visit to the Voortrekker Monument, the enormous mausoleum on a hilltop just outside the capital Pretoria. The monument, which celebrates Afrikaner nationalism, was begun in 1938 on the centenary of the Great Trek, and inaugurated by the recently installed National Party eleven years later on December 16, 1949 (the anniversary of the Boers’ triumph over the Zulu at Blood River). During my visit, I was not surprised by the old-fashioned nature of the small museum in the monument’s basement. For example, the text describing the Great Trek observes that the Boers who decamped from the British cape Colony in the 1830s were accompanied by their “black and coloured employees.” The truth, of course, is that many of these “employees” were slaves or near-slaves, and one of the central grievances Boers had as British subjects was the abolition of slavery.

As it turns out, the remnants of the Afrikaner cultural and political establishment no longer advance such a crude display of heritage. The Voortrekker Monument remains a hulking, if potent, reminder of a discredited past, and might even be considered kitsch at this point. But also astride that hilltop, and only a few hundred meters away from the old monument, one finds a spanking brand new “heritage center.” Inside, in addition to an archive and a small Afrikaans language bookshop, is a superb exhibit tracing the Afrikaner experience in the twentieth century.

I say “superb” in the sense that the exhibit—grandly entitled “Afrikaners in the 20th century: Pioneers. Beacons & Bridges”—brings the highest degree of professionalism to its narrative structure. Text is boldly presented, easily readable (in English and Afrikaans), and well-organized. The stunning visual imagery mixes photography, cartoons, graphic art, and historical facsimiles, and both enhances the text and tells a story on its own. The exhibit itself winds around a well laid-out space, clearly organized into sections on politics, culture, economics, warfare, social history, sports, and so on. Each section (or “theme”) is self-contained, and yet offers a coherent narrative flow, aided by numerous comprehensive timelines interspersed throughout. Finally, while the exhibit tells the story of a “people” in historical detail, with great sympathy and pride, and with a clear sense of evolution over time, it does so without reductionism—including, at least in the timelines, Afrikaner dissidents like Communist Bram Fischer and cleric Beyers Naude (both heroes in the ANC pantheon).

Nevertheless, the degree to which this “heritage center” rejects the current “liberation narrative” in South Africa and resurrects some of the most shopworn historical justifications for white supremacy left me stupefied. The extremely high quality of the exhibit disguises a nasty and treacherous undercurrent of unreconciled Afrikaner nationalism quite of a piece with the nearby Monument.

The first parts of the exhibit, beginning with a prelude to the twentieth century experience entitled “From European to Africander” lull one into complacency, for they seem accurate and even-handed enough. Unlike the museum inside the Monument itself, here the fact that the Boers left the British Empire for the African interior in the Great Trek of the 1830s as a reaction to slave emancipation is acknowledged. So too is the large numbers of Africans interned in concentration camps by the British during the Anglo-Boer War, a subject often neglected in accounts of the Afrikaner past. The narrative even refers to the birth of the ANC, noting that after Union in 1910 “African nationalism began to grow amongst literate black people” who were “increasingly critical of laws such as the Natives’ Land Act of 1913” (although the text fails to explain why, and does not link this act of land dispossession to the later Homelands policy of the apartheid state). Not surprisingly, however, apartheid is blamed on the British colonial legacy (with some justice, one must admit). After all, they were the ones who first recognized that “assimilation of the black majority was problematic because of the growing numbers of the black population and differences in civilization levels.” Characteristically, such colonial attitudes seem to be faulted and yet still go unchallenged by the “republican” tradition of the Boers and, later, Afrikaners.

The first parts of the exhibit, beginning with a prelude to the twentieth century experience entitled “From European to Africander” lull one into complacency, for they seem accurate and even-handed enough. Unlike the museum inside the Monument itself, here the fact that the Boers left the British Empire for the African interior in the Great Trek of the 1830s as a reaction to slave emancipation is acknowledged. So too is the large numbers of Africans interned in concentration camps by the British during the Anglo-Boer War, a subject often neglected in accounts of the Afrikaner past. The narrative even refers to the birth of the ANC, noting that after Union in 1910 “African nationalism began to grow amongst literate black people” who were “increasingly critical of laws such as the Natives’ Land Act of 1913” (although the text fails to explain why, and does not link this act of land dispossession to the later Homelands policy of the apartheid state). Not surprisingly, however, apartheid is blamed on the British colonial legacy (with some justice, one must admit). After all, they were the ones who first recognized that “assimilation of the black majority was problematic because of the growing numbers of the black population and differences in civilization levels.” Characteristically, such colonial attitudes seem to be faulted and yet still go unchallenged by the “republican” tradition of the Boers and, later, Afrikaners.

With the rise and triumph of Afrikaner nationalism after the 1930s, however, the exhibit becomes a bit unhinged. The fascist Afrikaner organization, the Ossewa Brandwag, is merely described as a “cultural organization” and dismissed as an “embarrassment” to many Afrikaners, without mention of the organization’s ardent pro-Nazi sympathies. In the section on rural Afrikaners’ legendary attachment to the “soil, his pride and his anchor”, the exhibit text resorts to time-honored paternalism: “the Afrikaans farmer…was ever ready to assist other cultural groups—chiefly labourers.” And in an extraordinarily unreconstructed turn of phrase, Apartheid is described merely as “the consequence of the Afrikaner’s political struggle to retain his independence.” Vis-à-vis English speakers? African nationalists? A hostile international community? The Red menace? All of the above? Not entirely clear.

Well, OK, maybe it was the Red Menace: by the time we get to the 1960s, the devilish role of Communism as the main enemy of white minority rule begins to loom ever larger in the exhibit’s text. “After becoming a Republic in 1961,” we are dutifully informed, “the onslaught against South Africa intensified from all sides” and “the ANC’s policy of urban and rural terror led to hundreds of casualties amongst innocent civilians.” No mention is made here of the ANC’s explicit policy of sabotage rather than the targeting of civilians, nor its decades of deliberate restraint in the face of torture, assassinations, infiltration, indefinite detention, bannings, and the rest. No hint of the South African police state breaks the complacent vision of a fair-minded white, Christian democracy under assault by terroristic communists and their international allies, especially the USSR; no reference to the ninety-day detention act, nor the hundreds of deaths in detention, need trouble the viewer in the face of the imminent Communist threat. After all, we are reminded, “almost the whole of the Executive Committee of the ANC were also members of the SACP.” Meanwhile, B.J. Vorster, the goodhearted and open-minded Prime Minister who succeeded H.F. Verwoerd in 1966, reached out to the rest of Africa, promoted the independence and development of the Homelands, and even legalized African trade unions!

It is true that the exhibit devotes a few panels to the Defiance Campaign and other non-violent ANC mobilizations of the 1950s. But, since no mention is made of the Sharpeville massacre (described, rather, as a “riot”), the visitor can only conclude that the ANC eventually resorted to armed struggle—excuse me, terrorism—at the behest of Soviet efforts to destabilize southern Africa. When it comes to the actions of Umkhonto we Sizwe (the military wing of the ANC, though the exhibit does not bother with this distinction), much is made of the infamous “Church Street bombing” in Pretoria in 1983, which killed a dozen civilians (even though it targeted a military installation). In the text appended to the enormous, blow-up picture of this act of violence comes the reminder that “in the following year 193 acts of urban terror were committed.”

The final section of the political narrative gives undue credit to the “radical reforms” instituted by the National Party in the 1980s as instrumental to forging a peaceful transition to democratic rule, and at the same time complains of “new national symbols, affirmative action, place name changes and practical disregard for Afrikaans.” Indeed, the largely upbeat narrative of Afrikaner nationhood, achievement, and consolidation in economics, politics, culture, national defense, and even armament production concludes with a distinct downer, noting that in post-apartheid South Africa, “Afrikaners found themselves increasingly marginalized.” The more things change, the more they stay the same, I guess.

On my way out, I noticed a panel at the entrance to the exhibit that I had missed before. There, the museum-goer is invited to experience an honest assessment of the Afrikaner past. Yes, the curators admit, “many mistakes were made.” My only question after seeing the exhibit was: what were they?

* Alex Lichtenstein is a labor historian and associate professor of history at Indiana University-Bloomington. Most recently, he wrote for the Los Angeles Review of Books on Marikana.

African Football Stars in America, Part One

The news that Nigerian striker Obafemi Martins is joining Major League Soccer’s Seattle Sounders from his Spanish club, Levante, may surprise and excite some people. Others view it as a last pay day. Don’t forget that Martins, who burst onto the scene in 2003, is listed as being 28 years old, though some people snigger at that. On top of it, FIFA President Sepp Blatter does not think highly of Major League Soccer (MLS) in the United States. Neither does Cheta Nwanze (Lagosian football sage who foresaw Nigeria’s Nations Cup triumph) who noted tersely that “Obafemi Martins has confirmed his retirement from all known forms of serious football”. But this kind of sniping has not diminished the lure of the MLS for foreign players (and not just those whose careers are on the wane). Especially African players. In this first of a two part series, we explore the African athletes making an imprint on US football right now. First up Tony Tchani, a twenty-three year old Cameroonian midfielder who plays for the Ohio Columbus Crew.

Then there’s Yann Songo’o, another Cameroonian:

Yann Songo’o plays for Sporting Kansas City as a defender. Yann is the son of former Cameroon national team goalkeeper, Jacques Songo’o.

Kei Kamara (Sierra Leone)

Kei Kamara, is a twenty eight year old striker, on loan from Sporting Kansas City to Norwich City. He’s been a big hit in East Anglia. They already wrote a (really naff) song for him and apparently his debut for the Canaries filled cinemas in Sierra Leone.

Steve Zakuani (Democratic Republic of Congo)

Steve Zakuani plays for the Seattle Sounders. After breaking his leg in a game back in 2011, he made his triumphant return to his team in the fall of 2012. Watch an interview where he discusses coming back after his injury here.

Kenny Mansally (Gambia)

Kenny Mansally plays as a defender for Real Salt Lake. Kenny was signed to Real Salt Lake after a previous contract with the New England Revolution. For a promo video with Mansally’s highlights click here.

Mamadou (Futty) Danso (Gambia)

Mamadou (Futty) Danso is a defender for the Portland Timbers, who used to play for DC United.

Kalif Al-Hassan (Ghana)

Kalif Al-Hassan is a twenty two year old striker who plays for the Portland Timbers. He is the son of retired international Ghanaian player, George Al-Hassan.

Lawrence Olum (Kenya)

Lawrence Olum, is a 28 year old midfielder who plays for Sporting Kansas City. He has played for numerous MLS clubs including the Minnesota Thunder, the Austin Aztex, and Orlando City.

Mehdi Ballouchi (Morocco)

Mehdi Ballouchi is a former Raja player, who played alongside Thierry Henry at Red Bulls, but currently plays as a midfielder for the San Jose Earthquakes.

Ty Shipalane (South Africa)

Ty Shipalane is a twenty-seven year old midfielder who plays for the lower league Carolina Railhawks (NASL).

Nizar Khalfan (Tanzania)

Nizar Khalfan is a midfielder who no longer plays for the Vancouver Whitecaps FC. I included him here because of his amazing goal for Vancouver in October 2011. He recently moved to Tanzania to play for the Young Africans SC, in the Tanzanian Premier League.

* Youssef blogs and tweets about international affairs. Sean Jacobs and Elliot Ross contributed to this post.

March 12, 2013

Shameless Self-Promotion: Chief Boima at The Apollo

This Saturday I’ll be djing between acts at The Apollo Theater’s Africa Now! Concert. Yesterday, I had an interesting conversation with the Apollo’s director about the different African crowds in New York (last year they had Tiken Jah Fakoly to an enthusiastic crowd of Francophone African Harlemites), got a tour of the building, rubbed the tree of hope, and stood on the stage where every American black performer of significance in the last 100 years has stood. Besides the fact of my inclusion in the symbolic welcoming of a new generation of Africans into the folds of Black American history, touching the log (while the Apollo stagehand watched me unamused) is really all I needed.

This Saturday I’ll be djing between acts at The Apollo Theater’s Africa Now! Concert. Yesterday, I had an interesting conversation with the Apollo’s director about the different African crowds in New York (last year they had Tiken Jah Fakoly to an enthusiastic crowd of Francophone African Harlemites), got a tour of the building, rubbed the tree of hope, and stood on the stage where every American black performer of significance in the last 100 years has stood. Besides the fact of my inclusion in the symbolic welcoming of a new generation of Africans into the folds of Black American history, touching the log (while the Apollo stagehand watched me unamused) is really all I needed.

Here’s all the info:

Apollo and WMI Present

AFRICA NOW!

Saturday, March 16 at 8 p.m.

Africa Now! is a weekend festival spotlighting today’s African music scene. The festival centers around a blowout concert event on the legendary Apollo stage. Featuring a line-up of artists who have drawn upon their roots for inspiration and transplanted them into the global music landscape, Africa Now! is a must see event. Blitz the Ambassador, Freshlyground, Lokua Kanza, and Nneka are scheduled to perform on this special night.

Hosted by celebrity chef Marcus Samuelsson.

Presented in partnership with World Music Institute.

Tickets: $30, $40, $55

In person at the Apollo Theater Box Office

By phone call Ticketmaster (800) 745-3000

Online at Ticketmaster.com

* Cross-posted at Dutty Artz.

Mukoma Wa Ngugi: The Western Journalist in Africa

Guest Post by Mukoma Wa Ngugi

In 1982, as the air force-led coup attempt in Kenya unfolded, we sat glued to our transistor radio listening to the BBC and Voice of America (VOA). In fact, the more the oppressive the Moi regime censored Kenyan media, the more Western media became the lifeline through which we learned what has happening in our own country. But in 2013, I and many other Kenyans saw the Western media coverage of the Kenya elections as a joke, a caricature. Western journalists have been left behind by an Africa moving forward: not in a straight line, but in fits and starts, elliptically, and still full of contradictions of extreme wealth and extreme poverty, but forward nevertheless.

A three paragraph article in Reuters offered the choice terms “tribal blood-letting” to reference the 2007 post-electoral violence, and “loyalists from rival tribes” to talk about the hard-earned right to cast a vote. Virtually all the longer pieces from Reuters on the elections used the concept of tribal blood-letting. CNN also ran a story in February of this year that showed five or so men somewhere in a Kenyan jungle playing war games with homemade guns, a handful of bullets and rusty machetes – war paint and all.

But very few people watching that video of the five men playing warriors, practicing in slow motion how to shoot without firing their weapons and slitting throats with the unwieldy machetes took it seriously. Rather, it was slap your knee funny. Last week Elkim Namlo, in the Kenyan paper The Daily Nation, wrote a piece satirizing that kind of reportage. The first sentence in the aptly titled, “Foreign reporters armed and ready to attack Kenya,” reads in part that the country is “braced at the crossroads…amidst growing concern that the demand for clichés is outstripping supply” and that “Analysts and observers [have] joined diplomats in dismissing fears that coverage of the forthcoming poll will be threatened by a shortage of clichés.” That particular CNN footage certainly supplied the high demand of clichés and stereotypes.

This is not to say that the threat of violence is not real. On election day, a separatist organization raided a police station in Mobassa, resulting in 15 deaths. The president-elect and his running mate will be appearing before the ICC to answer charges of crimes against humanity relating to the post-election violence of 2008. And with the runner-up Raila Odinga going to the courts (as opposed to the streets) to dispute the electoral results, we are not out of the woods yet. So there is a place for the kind of journalism that is in touch with the hopes and fears embedded in Kenya’s democracy.

For western journalism to be taken seriously by Africans and Westerners alike, it needs Africans to vouch for stories rather than satirizing them. I am not saying that journalism needs the subject to agree with the content, but the search for journalistic truth takes place within a broad societal consensus. That is, while one may disagree with particular reportage and the facts, the spirit of the essay should not be in question. But Africans are saying that the journalists are not representing the complex truth of the continent; that Western journalists are not only misrepresenting the truth, but are in spirit working against the continent. The good news is there have been enough people questioning the coverage of Africa over the years that Western journalists have had no choice but to do some soul searching. The bad news is that the answers are variations of the problem.

Michela Wrong, in a New York Times piece shortly before the Kenyan elections, debated the use of the word “tribe.” She acknowledged that the word tribe “carries too many colonial echoes. It conjures up M.G.M. visions of masked dances and pagan rites. ‘Tribal violence’ and ‘tribal voting’ suggest something illogical and instinctive, motivated by impulses Westerners distanced themselves from long ago.” But she concluded the piece by reserving her right to use the term. She stated that “When it comes to the T-word, Kenyan politics are neither atavistic nor illogical. But yes, they are tribal.” The term tribe should have died in the 2007 elections when Africanist scholars took NYT’s Jeffrey Gettleman’s usage of the term to task. To his credit, Gettleman stopped using the term.

If you have Wrong insisting on using a discredited analytical framework, you have others who position themselves as missionaries and explorers out to save the image of Africa. But their egos end up outsizing the story. Martin Robbins last year introduced his five-part essay on Kenya/Africa with the promise to tell misrepresented or rarely revealed truths about Africa. He was, he announced, “exploring the ways we were manipulated and misled by a procession of public officials, NGOs, activists and spokespeople; examining the reasons why a disturbingly high proportion of what we hear about Africa is just plain wrong.” His mission was however foiled by an ego that pushed out the search for the promised truths to create room for himself at the center of the story.

In “Grandma Obama’s support for domestic violence” the second of his five pieces, he writes, “President Obama’s angry granny stared impassively into the distance, as her rabbits relentlessly fucked each other around us. One ventured near her ankle, as if wondering whether to hump it.” Why destroy the subject of your reportage? Why impose the anti-establishment I can use fuck whenever I want young-writer-cigarette-drooping-from-lower-lip-angst over an old woman whose views most activist Kenyans disagree with?

The wildlife has been replaced by the horny rabbits circling Grandma Obama’s feet – a joke that succeeds only in turning Obama’s grandmother into a subject of scorn for holding views held by millions of men and women worldwide. Rather than read about the fucking rabbits, I would rather read about why she holds the opinions she does and what those in support or opposed to her views are doing. I want to see her opinions in relation to the larger society. In other words, I would rather read something useful rather than something that establishes its authority by destroying the subject of the reportage. There is no difference between the well-intentioned Martin Robbins imposing his ego over his African subject and the terrible reporter who yells Africa is a hopeless, violent, tribal, and bloody continent

The irony though, or perhaps the point, is that when Robbins is writing on issues outside of Africa his Livingstone alter ego is in check. For example, read his essay on “The new, old war on abortion” – yes, it’s an opinion piece, but his ego does not choke the hell out of the subject.

You have still others who see the question of how the Western media reports about Africa as fundamental and in need of intellectual discussion. Jina Moore’s essay in the Boston Review, “The White Correspondent’s Burden: We Need to Tell the Africa Story Differently,” is vastly different from Robbins’s essay in content, style and goal. Whereas Robbins’s Kenya writeups are ultimately about his heroic ego, armed with irony and sarcasm, Moore’s essay is seriously, and I think honestly, trying to understand why white journalists make the choices they make.

Her essay can be divided into three parts. The first part describes the problem – the Africa is one, Africa is violent, hopeless reportage. The second part, where her essay really begins, tackles the historical and philosophical reasons for what is essentially a racist trope that will simply not go away. First she says, it is not widely accepted that the West is responsible for the most of the suffering, “centuries of slave trade, followed by a near-century of colonialism and its attendant physical and structural violence, from the rubber fields of the Belgian Congo to the internment camps of British Kenya.” In spite of the obvious direct correlation between slavery or colonialism and destitution, the idea of a good moral agent emerged. But more than that, she argues, this moral imperative became more about the giver than the recipient. So now it is not about helping Africa per say, it is about having a moral and ethical Western civilization; we are civilized because we help those that we abuse. Call it a fast track to getting to heaven or remaining relevant in Hollywood. When this moralization is transposed into reporting, Africans becomes the “subject of compassion” and not “the subject of a story.” There is not much to disagree with there.

All this provides a reminder to journalists that history matters and that they should also look beyond the effects of poverty and violence and talk about the causes – African leaders, corporations that mine wealth without giving back, arms companies etc. In other words, let’s look at all the actors instead of seeing Africa outside present-day global economic political processes.

The third part of Moore’s essay mainly deals with the choices that the reporters make, why they think they have to make them, and the consequences. She talks about Howard French, formerly with the New York Times, who writes about tragic stories because he would otherwise feel guilty if he told a happy story and leave the atrocities unexposed. This is a sentiment with which human rights activists in the Congo, Kenya and elsewhere would agree.

It is the lesson that Moore takes from this that I disagree with. She argues that “We can write about suffering and we can write about the many other things there are to say about Congo. With a little faith in our readers, we can even write about both things—extraordinary violence and ordinary life—in the same story.” On the face of it, it does read like a sound choice, to show the tragedies and at the same time show day-to-day living. That is, until you think about how Western reporters write about extraordinary violence in their very own backyards.

In the West, tragedy after tragedy, the journalist does not forget the agency of the victims, and their humanity. The 2010 London riots, or rebellion, depending on your take: In equal measure the rioters and the fed up shop owners who started cleaning up after the rebellion — the heroic street sweepers. The August 2012 Sikh temple massacre: yes, the violence but also how a rainbow community came together to stand against extremism. The 2012 Colorado movie shootings: the brave boyfriends who shielded their girlfriends and died protecting them. The 2011 Tucson shooting: Gabrielle Giffords and her recovery.

September 11: yes, the terrorists, but also the firemen who died saving others. School shootings in the US: the brave teachers and students who at the risk of life and limb rose in defense of others. The War on Terror: the individual soldiers losing souls, limbs and life in a war that is bigger than them. And Hurricane Katrina: yes, the black people looking for food were portrayed as looters and the whites as survival experts, but most stories also contained something about how the people were trying to keep a sense of community and rebuild their lives.

But when it comes to writing about Africa, journalists suddenly have to make a choice between the extraordinary violence and ordinary life. It should not be a question of either the extreme violence or quiet happy times, but rather a question of telling the whole story within an event, even when tragedy is folded within tragedy. There are activist organizations in the Congo standing against rampant war and against rape as a weapon. The tide of the post-electoral violence in Kenya in 2007 turned because there were ordinary people in the slums and villages organizing against it — that is, people who stood on the right side of history as opposed to ethnicity — in the same way Americans across the racial spectrum stood last year with the American Sikh community.

In any situation, there are those who perpetrate and those who, defenseless and weak, still stand up at great cost for what is right or just. It is the nature of humanity – that is why we are still here, as a species. We struggle often against forces stronger than ourselves. Sometimes we triumph and just as often we fail. The question for Western journalists is this – when it comes to Africa, why do you not tell the whole story of the humanity at work even in times of extreme violence?

* Mukoma Wa Ngugi is an Assistant Professor of English at Cornell University, the author of Nairobi Heat (Melville, 2011) and the forthcoming Black Star Nairobi (Melville, 2013).

March 11, 2013

Zimbabwean Activist Jestina Mukoko ‘Released’

On Sunday, Jestina Mukoko, Executive Director of the Zimbabwe Peace Project, was ‘released’ from prison. Her defense attorney and fabulous feminist human and women’s rights attorney Beatrice Mtetwa, among others, greeted her. Yes, it’s springtime in Zimbabwe, as in Zimbabwe Spring … except that it’s not. Friday was International Women’s Day, #IWD2013. To honor that, the Zimbabwean government organized a fake flight and a fake hunt. The government claimed that Jestina Mukoko was on the run. By all accounts, she wasn’t. The government put out an all points bulletin on Jestina Mukoko, organized a full-scale media appeal, pleading with ‘citizens’ to ‘notify the authorities’ if she was spotted.

Not knowing that she was a ‘fugitive’, Mukoko walked into the police station and turned herself in, if that’s the right phrase. And she was held in police custody and interrogated for two days.

Jestina Mukoko is no stranger to Zimbabwean prisons. In 2008, she was held and tortured in prison. She has since sued the government for having tortured her. The Zimbabwean Supreme Court ordered a permanent stay of execution. As the weekend’s events show, ‘permanent’ is a fluid concept.

Some fear the ‘return to terror’, while others hope for something called healing. Others in the media note the use of the media to persecute Jestina Mukoko. Of course, they mean ‘the other media’.

So … happy International Women’s Day, Zimbabwe! Meanwhile, once again Jestina Mukoko is described as ‘released.’ Released? Really?

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers