Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 482

March 22, 2013

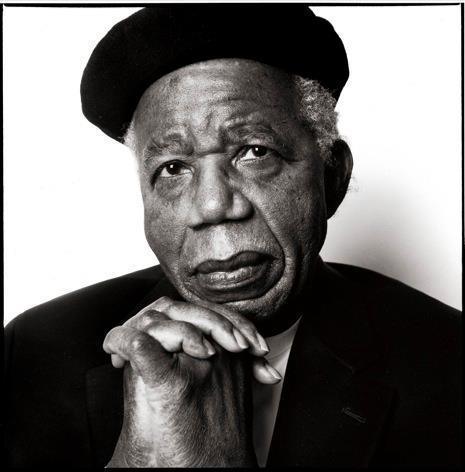

Chinua Achebe 1930-2013

Age was respected among his people, but achievement was revered. As the elders said, if a child washed his hands he could eat with kings. – Things Fall Apart.

It is not a surprise the amount of tributes that have poured in from around the world following the passing on of perhaps Nigeria’s greatest ever writer. Chinualumogu Albert Achebe died last night aged 82. Why was Chinua Achebe so readable and Wole Soyinka almost inscrutable? The former was a writer, a storyteller — the latter is a poet who just happens to write.

Chinua’s telling of stories and his command of the English language was such that the moment you picked up a Chinua Achebe book, putting it down became almost an impossibility. His understanding of the culture of his Igbo people, my people, was also virtually unrivalled. A lot of the Igbo proverbs I learned first, I learned from his magnum opus, Things Fall Apart. However, when talking of a giant of literature such as Chinua Achebe, it is plain wrong to use the phrase magnum opus to describe his work.

His craftsmanship as a story teller was such that he had a plethora of work that made up his magna opera.

As compared to a lot of people, Achebe was a man of character, who refused not one, but two national honours because he was not at peace with the way Nigeria is being run. Only if our government(s) had been reading.

No Longer At Ease, his second novel, and in many ways more poignant than Things Fall Apart itself, is a book that peers deep into the Nigerian psyche and foretells in more ways than one, the emergence and eventual proliferation of Nigeria’s current national malaise, corruption.

“It is all lack of experience,” said another man. “He should not have accepted the money himself. What others do is tell you to go and hand it to their houseboy. Obi tried to do what everyone does without finding out how it as done.” He told the proverb of the house rat who went swimming with his friend the lizard and died from cold, for while the lizard’s scales kept him dry the rat’s hairy body remained wet.

In this passage, describing the reaction of the Umuofia Progressive Union after Obi Okonkwo had been caught for bribery, Achebe tells us about our own complicity in this culture of corruption that is destroying our country. The truth was that the members of the Umuofia Progressive Union were not concerned about the fact that Obi accepted bribes. Rather, their grouse was that he accepted bribes without covering up his tracks. This, up until today, half a century after those words were set in stone, is the root of our disease today.

The seer that he was, peered into our psyche even in such a “mundane” thing as our stamina as a people. In Arrow of God, Ezeulu, given the power to make decisions on behalf of the god Ulu, Ezeulu would not dare test that power. But his people, were quick to abandon him on his return from prison, because of the “small issue” of being unable to harvest their yams. The conversion of the people of Umuaro to Christianity because Ezeulu did not perform the New Yam Festival, foretold our inability to weather storms as a people, together. A failing talked about by another Nigerian great, Fela Kuti, in his Sorrows, Tears and Blood.

But Chinua Achebe was not just a writer about culture, tradition and the contemporary. One of the first books I recall reading was Chike and the River. Being ethnically from that region but hailing from another part of the country, I began, at that young age, to appreciate the vital importance of the River Niger to commerce in our environment.

Chinua, as he grew older, and especially after Nigeria’s devastating Civil War, became more introspective, and tried to, in his own literary manner, warn us about the road we had taken. A warning that as a people, we have failed to heed.

In yet another seminal piece, The Trouble With Nigeria, Chinua said, ”In spite of conventional opinion Nigeria has been less than fortunate in its leadership. A basic element of this misfortune is the seminal absence of intellectual rigour in the political thought of our founding fathers — a tendency to pious materialistic woolliness and self-centred pedestrianism.”

There you have it. He was probably the first to identify something that a few Nigerians are beginning to come to terms with, that our founding fathers were not all that. Such was his genuine insight into the character of this country that he called home.

In his last book, There Was A Country, came for the first time since I started reading him, long passages that I disagreed with. However, one cannot fault what he wrote because he clearly stated from the beginning that the book was a personal history. That personal history was perhaps his greatest gift to Nigeria. Mistakes were made in those dark years between 1966 and 1970. Those mistakes are finally being documented by some of the people who went through those days. We MUST learn from it.

Regarding the man, it is simply impossible for an iroko tree to fall and the forest to remain quiet. The tributes and obituaries that have poured in from various parts of the world should be a pointer to the younger generation of Nigerians. Chinua Achebe was by no means a wealthy man. He was not a pauper either. But by using his God-given talents, he achieved global recognition. Now that the curtains have been drawn on his life, we can all sit back and see how the world treats a genuine icon. He lived to a grand old age. He was also an achiever. And the world has now shown, it is not only among ndi Igbo that achievement is revered. In publishing Things Fall Apart at age 28, Chinua washed his hands early. And Kings invited him to the table, such that he had the luxury of choosing what banquets to attend, and which to reject.

Iroko ada na! Dike eji aga mba na gbo. Prof, kachifo.

Welcome to Mali

Bamako airport (Photo by Glenna Gordon for everydayafrica.tumblr.com)

Bamako doesn’t feel like the capital of a country at war. True, people are stressed, and the pace of life might have slowed. The city’s building frenzy has subsided. Ça va pas, but things are calm, even if late in March, far from cool. In the distant North, a fifth French soldier died over the weekend, and my tantie, a venerable hajja, cried for him. While the government here expresses its gratitude for French sacrifices — and its citizens their shame at having others fight for them — it refuses to say how many of its own soldiers have died in the most recent fighting, which is led mostly by French and Chadian troops. The press here gives the impression that the army’s battles remain first and foremost political and inwardly directed. Meanwhile, more than two months after French helicopters attacked jihadi Salafist fighters on the road to Sevare, more than one war is being fought in the distant Malian Sahara.

Necessary as it was, France’s intervention never offered a real solution to any of Mali’s problems. It did, however, create a preferable set of problems to the ones this country would otherwise have faced. The arrival of French troops both stopped the advance of a coalition of mujahideen on the vital town of Sevare and quashed what looked to be the imminent threat of another coup d’état by Mali’s still powerful junta against the interim civilian government it was forced to accept — however partially — last April. How dire would the situation have been if the army had come back to power, if Sevare had fallen to the Salafists, or both? Or worse? Some say that Bamako was the real aim of the offensive, although this seems unlikely to me and there’s no real evidence for it. Whatever the case may be, for an exceptional moment in January, French and Malian interests converged, and the enduring popular support for the intervention suggests that many people here agree with that assessment.

The two governments had shared enemies and — at least in the short-term — shared interests. They fought an alliance of jihadi Salafist fighters made up of AQMI, MUJAO, Ansar Dine… For reasons internal and external, Mali’s army could not face them alone, in spite of a common and comforting fairytale claiming that it could. But if they shared enemies, the two countries did not share the same objectives, much less the same war. The question in the wake of French advances is how dramatically those objectives will diverge.

They have already begun to do so, in spite of the best efforts of Paris and Bamako to harmonize their discourse, if not their actions. The clearest evidence of this divergence is the ongoing, ambivalent relationship of French forces to the Tuareg separatist movement, the MNLA, which continues to control the important northern town of Kidal and to insist that the Malian army has no place there. Civilians in Kidal — the largest predominantly Tuareg town in Mali — fear reprisals if the army returns, and quite understandably so. It’s not clear that anyone controls the Malian army as a whole — even if different officers clearly have a handle on part of it — and its soldiers have targeted Tuareg and Arab civilians in both the distant and the very recent past. Knowing that history well, many people in the North feel that the French army is their best protection (many in the South feel the same way, albeit for different reasons). Just as France wants to use the MNLA, the MNLA wants to use France. Having failed to persuade France to consider it as a proxy army, for the moment the MNLA has come out rather well from the French intervention, which elevated the movement from defeat to relevance and positioned it to absorb many of the fighters abandoning Ansar Dine. All this jibes badly with the shared commitment to Mali’s ‘territorial integrity’ proclaimed in Paris and Bamako. Put differently, the essential challenge to Malian sovereignty posed by the French intervention might not be the fact that it happened, but the specific form it takes in Kidal and its broader region, where the thorny question of proper governance has to be seized, and if possible resolved.

So if French and Malian interests have begun to diverge, the question is how greatly and for how long they will do so. The answer to those questions depends on another, deceptively simple one: How many wars are being fought in the Sahara?

Mali’s war seeks to restore the power of the central state and its core traits of secularism (laicité) and territorial integrity, both of which remain live and nonconsensual issues. This war is far from over. Not too long ago — but before the fifth French death — Prime Minister Django Cissoko argued that, militarily, “the hardest part is behind us” and that the “essential (most vital part) has been done”. Never mind the desire to put on a brave face, this was a shameful thing for the Prime Minister of a country ‘liberated’ by foreign forces to say. No truce or cease fire has been established, and some 400,000 of his fellow citizens have been chased from their homes. They have only begun to return. Vast swathes of the North, including Kidal, remain outside government control, as do factions within the army. The government itself is long past the expiration of its short-term legitimacy, but elections promised for July threaten to be too much too soon. Clearly “the essential” has not been done, whether in the North or in the South.

Launched in haste but persecuted effectively, the French war is not the Malian war; it merely envelopes one conflict inside another. As West African forces arrive, a European Union training mission finds its feet, and the UN tries to work out how to be legitimate without being responsible, French departure might become possible. Yet the central fact remains that no one wants to own or to pay for what has become France’s problem.

Although French President François Hollande claims that France forces will draw down soon, he is being willfully optimistic. Much remains to be done. If hostages provided one motivation for France to intervene, more have since been taken; if territorial integrity was the aim, it remains undetermined; if it was to ‘end’ terrorism, the jihadi Salafists targeted by that phrase have yet to be caught (reports of recent deaths of leaders remain unconfirmed), and, according to the French Minister of the Interior, more have been recruited; if it was to secure future access to uranium, it was a bad bet, they are in the wrong place, and they ought to know that the peaceful model is likely to be more effective, as Niger’s recent if delicate experiences suggest.

Third, there is the war of the mujahideen. In spite of heavy losses in their ranks, the war itself is not yet lost. AQMI, at least, has claimed to want a long one, and for years has broadcast its to draw France in particular into a Saharan war. It is too soon to tell whether or not, having got what they wanted, the mujahideen — especially their new recruits — have changed their minds. But the current moment might be only the end of the beginning, and too tight a focus on this ‘big’ war only obscures the smaller, more essential conflicts that enable it.

The most important of these is the war launched by the MNLA in January 2012, the one which sparked the others, and which still rattles around within the shells meant to contain it. The Tuareg separatists claimed to have won it in April, lost it to their erstwhile allies amongst the mujahideen in June and July, and must now be hoping that France might win it for them after all. They have more reason to be optimistic than does François Hollande, who commands the troops without controlling the situation. His Minister of Defense Jean-Yves leDrian has lately been arguing that before being deployed to Kidal, Mali’s army must be restructured, retrained, and submitted to civilian authority. Moreover, by his reckoning, disarmement of the MNLA would only be appropriate after a process of national dialogue and reconciliation has taken place. All that would take months, if not years, and would give local diehards every reason to promote instability. Whatever scenario le Drian has in mind, the French Minister of Defense seems to be coming awfully close to laying down the limits of his weaker partner’s sovereignty. It is up to President Traore and Prime Minister Cissoko to set some boundaries of their own, a fact that once again brings the Mali crisis back to the need for the government at Kuluba to establish control over the garrison at Kati.

Finally, both France and Mali both claim to be fighting a war against terrorism. Here again, they speak the same language but mean different things. France means the hostage takers who target their citizens for ransom and threaten worse. For many Malians, the term ‘terrorist’ refers to the MNLA. When national television proclaims that the country is fighting a war against terrorism, they think of the war that began in January 2012, not the conflict with AQIM and its allies, which ex-President ATT once dismissed as “other peoples’ wars.”

None of this is very pretty, but two facts emerge from it. First, the French might be only ones who want France to leave Mali any time soon. Almost every other actor would seem to have a vested interest in having them stick around for a while. That fact in and of itself might provoke future violence. The second, more important, point, is this: France can make war in Mali; it has done so in more ways than one, and (counting Nicolas Sarkozy’s presidency) more than once. But France can not make the peace. That will be up to the better angels of people in Kuluba, Kati, Kidal, and beyond. While waiting for those angels to appear, it is looking ever more likely that France will claim to win its war while Mali fails to win its own.

5 Films to Watch Out For, N°20

Born in a small township near Gondar in northwest Ethiopia, Yityish Aynaw recently became the latest Miss Israel. And then made some dumb comments about Ethiopian heritage and beauty. (“We have these chiseled faces. Everything is in the right place,” she said. “I never saw an Ethiopian who was stuck with some big nose.”) Which reminded me of the fairly new 400 Miles to Freedom, Avishai Mekonen’s film about Ethiopian immigrants who left their homes to make a living in Israel, and what they found there. It is also about Judaism and race. Trailer above. Also about migration, but of a different kind, is Comme un Lion (“Like a lion”). Mytri is a young Senegalese football player who’s offered a contract and a bright future in France by one of those many talent scouts swerving through West Africa. Once in Paris, that future turns out to be not quite what Mytri imagined it to be. Director Samuel Collardey’s style of realism has been compared with that of Ken Loach. One to watch:

(Related: I read Benoît Poelvoorde is working on a similarly-themed film.)

Produced by the German Goethe Institute’s Sudan Film Factory, Cinema Behind Bars tells a story of cinema in Sudan. Bahaeldin Ibrahim takes the viewer on a journey to Atbara; “Not spectacularly, but quietly and carefully”:

Sobukwe: A Great Soul recently won best documentary feature at a Saftas gala best quickly forgotten. Its director, South African Mickey Madoda Dube, also won the best director award. Percy Zvomuya wrote an introductory review of the docu-drama about the life of Pan Africanist Congress leader Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe when it first came out.

And another documentary to watch out for is Malian director Souleymane Cissé’s portrait and homage to legendary Senegalese film maker, writer and philosopher Ousmane Sembène (in the photo left). Title: O Sembène! I haven’t come across a trailer yet, but the first reviews (in French) are promising. Like this one for example. Choice quote by Sembène: “Europe is not the center, it is on the outskirts of Africa” (“L’Europe n’est pas le centre, elle est la périphérie de l’Afrique”).

And another documentary to watch out for is Malian director Souleymane Cissé’s portrait and homage to legendary Senegalese film maker, writer and philosopher Ousmane Sembène (in the photo left). Title: O Sembène! I haven’t come across a trailer yet, but the first reviews (in French) are promising. Like this one for example. Choice quote by Sembène: “Europe is not the center, it is on the outskirts of Africa” (“L’Europe n’est pas le centre, elle est la périphérie de l’Afrique”).

March 21, 2013

Ben Affleck makes the DRC cool again

The New York Times, in its infinite wisdom (it comes with being The New York Times), decided that one of the paper’s reporters, one Brooks Barnes, should write what amounts to a fluff piece (it’s not actual reporting) splintered with quotes in the “Fashion & Style” section about actor Ben Affleck’s supposed maturity and all-round goodness. Affleck, who we like to refer to as Life President of the Democratic Republic of Congo, is held up as “Hollywood’s New Role Model” and as the “new Hollywood paradigm for masculinity.” His qualifications are being a husband, parent, and, yes … “eastern Congo philanthropist.” So the DRC is a prop for “the way to be cool now” in Hollywood. I know someone’s going to tell me this is all good fun. Thank you Brooks Barnes. Link.

Invisible Jason Russell

CBC radio 1’s Jian Ghomeshi conducted a “rare” interview with Jason Russell of KONY2012 fame this week. Russell, who is on some kind of media tour (he indulged the most prominent British media outlet in an interview that was an embarrassment to that paper, a few days ago and now Canada of course) remains brazen in the face of the criticisms that likely caused his breakdown last year and is about as unreflective as any master of the universe would be. Listen here.

Why Goodluck Jonathan’s presidential pardons are a bad idea

Last Tuesday, President Jonathan pardoned 7 Nigerians. While four of those pardons, Diya, Yar’Adua, Adisa and Fadipe have raised semantic issues as they had been granted ‘clemency’ under the regime of General Abdusalam Abubakar in 1999, the remaining three–former Bayelsa governor, Diepriye Alameisiyagha (among others, he dressed up as a woman and skipped bail in Britain on charges of laundering £1.8m.), former Bank of the North Managing Director, Bello Magaji, and ex-Major Bello Magaji–have been controversial.

Of course, most commentators, domestic and foreign, have spent a lot of time talking about the Alameisiyagha pardon, with all sorts of threats made, and calls for the President to withdraw the pardon. But something must be brought to the fore here: we all have friends, and to be honest, if I became President tomorrow and one of my really close friends did something silly, I would most likely chose to abuse my Presidential powers to grant them pardons.

However, I would chose my timing better. Such an abuse of power, is usually the prerogative of a lame duck President just before he leaves office. A final double middle-finger to a once loving electorate. Let’s make no mistakes, each and every one of you reading this would more than likely do the same, so let’s cut the man some slack.

More importantly to me, is the fact that all the noise makers now, did not do much to prevent the deed from being done, and that is the crux of the matter. The agenda for the National Council of State was public knowledge before the meeting, and I personally called not a few people to help make calls and work their networks so the travesty would be averted. Not much was done. Now we are making a whole lot of noise like it would get the man to change his mind? I don’t think so.

Truth be told, the President’s spokesmen have consistently quoted the Constitution and emphasized that his actions were legal. Which is an irony considering that the same Constitution also requires elected officials to declare their assets before assumption of office. Something the President said on national TV last year that he “doesn’t give a damn” about. In essence, the pardons display the selective compliance with the law by the holder of the highest office in the land and sets a very bad example. But like I said earlier, I’m not really bothered about Alameisiyagha and Bulama, for the simple reason that deep down, I know that a few weeks down the line, something else will come up, and we will all forget about Alameisiyagha. Sorry, I lie. Yesterday, the President told us that he will soon increase petrol prices again, so something has come up, and Alameisiyagha will soon be taking a back seat.

However, regarding ex-Major Magaji, ALL OF YOU READING THIS, would be as guilty as the President in this scandal if you let it die. Forgive my rather poor research skills, but I need to ask a question: In what country, ever, has a pedophile rapist been granted a state pardon? The details of ex-Major Magaji’s conviction make for gory reading–and rather than getting him on a sex offenders’ register as is done in every civilized environment, we are letting him loose again on our children. This particular pardon is in many ways, far more reprehensible, even than those granted to Bulama and Alameisiyagha. No sane parent could countenance a pardon for a man who lured unsuspecting children to his home, plied them with alcohol, and then sodomized them in a brutal destruction of their innocence. I wonder if the President were the parent of any of ex-Major Magaji’s victims, whether he would applaud this pardon. Our children are our future, and it is our duty to make it known without equivocation that they are our most precious possessions and anyone who dares to trample on them, must/should be dealt with to the fullest possible extent of the law.

By pardoning Ex-Major Magaji, what message is our President sending to our children now and in the future? That we don’t give a damn?

March 20, 2013

The Happy Dutch Sprinter

Television commercials can be pretty annoying. With the exception of the few that make you laugh. Quite often it’s the good commercials of which you forget what the company is actually trying to sell. However the annoying ones, that is a different story. Their tunes, actor and catch phrases crawl into your head, triggering a bodily sensation every time they’re on TV, usually every thirty minutes. As soon as you hear the very first notes of the jingle or the actors’ voices you jump up like a 100-meter sprint athlete, rushing to the remote to switch the channel. Recently a TV commercial in the Netherlands for an oven dish by sauce manufacturer Remia has triggered exactly this reaction; added with a hit of shame and a teaspoon of sadness.

Television commercials can be pretty annoying. With the exception of the few that make you laugh. Quite often it’s the good commercials of which you forget what the company is actually trying to sell. However the annoying ones, that is a different story. Their tunes, actor and catch phrases crawl into your head, triggering a bodily sensation every time they’re on TV, usually every thirty minutes. As soon as you hear the very first notes of the jingle or the actors’ voices you jump up like a 100-meter sprint athlete, rushing to the remote to switch the channel. Recently a TV commercial in the Netherlands for an oven dish by sauce manufacturer Remia has triggered exactly this reaction; added with a hit of shame and a teaspoon of sadness.

The commercial simply entitled ‘Remia saus voor ovenschotel’ (“Remia sauce for oven dishes”) features Dutch/Antillean athlete Churandy Martina. In the one-minute commercial we first see Martina preparing Remia’s new instant dish. With each ingredient he adds to the dish, Martina says: “Ik ben blij” (“I’m happy”, in Dutch). We’ll get to why he says that in a bit. Here’s the commercial:

After putting the dish in the oven he reads the back of the package and learns that it only takes five minutes to get ready. Although this is pretty quick (given it’s an instant meal), Martina swears that it can be done even faster. The commercial then cuts to a running track where we see five athletes ready for a 4 x 100 relay race. As soon as the starting shot sounds, the men race off. The comical element is that the athletes have the instant dish in their hands while running. With each handover the athlete adds an ingredient to the dish (like Martina did in the previous scene) and passes it to a team mate until we get to Martina himself who doesn’t only put the dish in the oven, but also wins the race in 39.11 seconds – a ‘world record’ – and is thus faster than Remia claims it takes to prepare the dish.

The play on Martina’s speed as the national and European champion (with the relay team) and the speed at which the product is prepared make for a nice pun. It gets people laughing, sharing it on social media and of course reinforces the brand name.

However, this commercial also reinforces the stereotypical images of minorities in the Netherlands. In this case black people. And to be more specific, people of Dutch Caribbean decent, where Martina’s roots lie and whose socio-economic position in the Netherlands can be described as (at the least) problematic; second class citizens in the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

The Dutch Caribbean consists of six islands in the Caribbean that are part of the Dutch Kingdom: three of them are ‘special municipalities’ while the three other ones are ‘constituent countries’ within the Kingdom — quite the re-branding of the concept of the Colony in the 21st century.

Now, the Dutch have a habit of cherry picking when it comes to these islands. White sandy beaches are labeled ‘Holland in the tropics’, while high unemployment rates are the result of mismanagement by the ‘corrupt’ local government; drug runners are Antillean youth, while an Olympic athlete running next to Usain Bolt is suddenly a ‘Hollander’ (“Dutchie”) — even if the criminal and the athlete share the same Dutch passport.

Since the dissolution of the Netherlands Antilles in late 2010 (the Caribbean country the Dutch Antilles were formally known as), Martina decided to run for the Netherlands since the ‘new’ countries for the time being didn’t have an Athletics Federation. Martina has been a pretty successful athlete for over a decade, but his real rise to fame in the Netherlands came at the 2012 London Olympics.

Martina not only became a “Dutchie”, he also became that funny black guy who speaks broken Dutch with a very heavy accent. Asked about his performance during the Olympics, Martina’s only response to the press would be “Ik ben blij” (“I am happy”), followed by a big smile into the camera including one gold-capped teeth, like in the Remia commercial.

And now, months since the closing ceremony of the Olympics, the Dutch public can once again laugh not just at Martina, but at the Antillean people at large, as he has almost become the personification of the entire group.

The government monitors this group of people closely. For example by a special task force responsible of 22 towns and cities that are labeled ‘Antillean municipalities’ within the larger Association of Netherlands Municipalities that occasionally come together to discuss how to fight problems caused by young ‘lower class’ Antilleans. Like in the ‘Antillean municipality’ of Den Helder where in 2010 about 300 Antilleans were screened intensely. The reason why in the first these people showed up on the radar was because they belonged to the Antillean community, living in a city known for a ‘large’ concentration of Antilleans: 2.4% of the total city population.

And this is exactly the reason why, next to his performance at the Olympics and his ‘funny’ language, Martina became so popular in the Netherlands. Because, despite his stereotypical appearance of an Antillean criminal (tattoos & gold teeth), he turned out to be very approachable. Our new teddy bear pet. Always happy. Tamed, and available for consumption. (You laugh, but not so long ago black TV-presenter John Williams was featured in a commercial for chocolate mousse: while eating chocolate mousse with her white husband, the white woman in the commercial secretly fantasizes about something else that’s black and sweet.)

And this being the country of Black Petes, nobody blinks at these two TV-show hosts’ blackface impersonation of Martina.

One could argue that commercials always play on stereotypes and exaggerate peoples’ behavior. Indeed, and for this reason the Martina commercial works. But at the same Olympics last year, the world was also introduced to another Dutch athlete in the Aquatics Center: swimmer Ranomi Kromowidjodjo returned home with three medals. Her name indeed suggests (for those who know Dutch a bit) as being of foreign origin. She is the daughter of a Surinamese father and Dutch mother. To be precise, a mother from Groningen, a province in the north of the country. Now, everything in the Netherlands that is not “West” basically constitutes as “rural” — at least to those of the largely urbanized west. And “rural” also means “real Dutch”. So when Kromowidjodjo was featured in a short documentary (skip to minute 12:25), she was framed as the typical Dutch girl, riding her bike trough the typically Dutch landscape. And that ‘weird’ name? Oh, that’s taken for granted.

Ranomi Kromowidjodjo is that girl from a province of hard working farmers and is thus an athlete who has trained hard to get where she is now, while Martina is that funny Antillean with a funny accent who barely speaks Dutch. The reason why Martina runs that fast can’t possibly have anything to do with him training as hard as Kromowidjodjo – Black people are fast by nature.

Ranomi Kromowidjodjo is that girl from a province of hard working farmers and is thus an athlete who has trained hard to get where she is now, while Martina is that funny Antillean with a funny accent who barely speaks Dutch. The reason why Martina runs that fast can’t possibly have anything to do with him training as hard as Kromowidjodjo – Black people are fast by nature.

The sad thing though is that the Martina commercial is yet another commercial that plays on the stereotypical image of black people living in the Netherlands (either from Caribbean or Surinamese decent). I already mentioned the one with John Williams. But we also had the ‘hysterical black woman’ who loses her mobile phone. (You might recognize her as being the main actress in the movie Alleen Maar Nette Mensen about which we blogged before.) Then we have ‘big mama’ whose swearing in the Surinamese language (Saka Saka boy – “Bastard”) makes us want to cancel our mobile phone subscription. And since a few weeks we can also enjoy the ‘funny’, out of place Surinamese man in the Alps dressed in German lederhosen, including Surinamese accent.

Can ‘normal’ black people not sell a product? Where is Oxfam when you need a rebranding?

The Blood of the Impure

Post by Laurent Dubois

Post by Laurent Dubois

The French national anthem, La Marseillaise, is, if you think about it, a pretty nasty song. It dreams, in one of its more memorable verses, that the “blood of the impure” will “irrigate our fields.” It’s a rousing anthem, to be sure, and I myself can frequently be heard humming it to myself in advance of a match being played by Les Bleus, or as I ride my bike or do the dishes. I’ve found that it’s sometimes hard to find a French person (at least if you hang out, as I do, with too many intellectuals), who can actually sing it without irony. And yet, over the past 26 years, the question of whether a particular subset of French men – those who play on the national football team – sing the Marseillaise under certain conditions has been a rather unhealthy obsession in France (we’ve blogged about it before, when Kinshasa-born flanker Yannick Nyanga sobbed uncontrollably during the anthem ahead of a rugby match vs Australia last year).

We are now being treated to what feels to me like Act 467 of this drama. Karim Benzema, as anyone who attentively watches French football matches knows, doesn’t sing the anthem before matches. In a recent interview, asked why, he answered in a pleasingly flippant way: “It’s not because I sing that I’m going to score three goals. If I don’t sing the Marseillaise, but then the game starts and I score three goals, I don’t think at the end of the game anyone is going to say that I didn’t sing the Marseillaise.” Pushed further on the question, he invoked none other than Zinedine Zidane who, like Benzema, was the child of Algerian immigrants to France – and who also happens to be the greatest French footballer of all time, and the one to whom the team owes its one little star on its jersey: “No one is going to force me to sing the Marseillaise. Zidane, for instance, didn’t necessarily sing it. And there are others. I don’t see that it’s a problem.”

Ah, Karim, but it is a problem, don’t you see? In fact, your decision about whether to vocalize or not, as you stand in line under the careful scrutiny of cameras, about to enter into a hyper-stressful and aggressive sporting match during which your every action will be dissected and discussed, is an unmistakable sign about whether or not the true France will survive or alternatively be submerged in a tide of unruly immigrants and their descendants.

Notwithstanding the fact that, as Michel Platini has noted, in his generation no footballers ever sang the Marseillaise, and that “white” footballers – even the Muslim Franck Ribéry, who at best mutters a bit during the anthem but is much more enthusiastic in his pre-game prayers to Allah – are rarely if ever asked this particular question, even so some will continue to insist that your choice not to sing is a window onto your disloyal soul. As the Front National explained: “This football mercenary, paid 1484 Euros per hour, shows an inconceivable and inacceptable disdain for the jersey that he is lucky to be able to wear. Karim Benzema does not “see the problem” with not singing the Marseillaise. Well, French people wouldn’t see any problem with having him no longer play for the French team.”

Some genealogy is in order here. In 1996, Jean-Marie Le Pen first levied this accusation against the French team. France was playing in the European Cup, and playing well. But he was a bit disturbed by something he saw: an awful lot of them seemed, well, not really to be French. “It’s a little bit artificial to bring in foreign players and baptize them ‘Equipe de France,’” he opined. The team, he went on – with blithe disregard for the bald falsity of what he was saying, since no one can play on the French team who is not a French citizen, and nearly all of the players had in any case been born in France – was full of “fake Frenchmen who don’t sing the Marseillaise or visibly don’t know it.” When pressed on these comments a few days later, he lamented that while players from other countries in the tournament sang their anthems, “our players don’t because they don’t want to. Sometimes they even pout in a way that makes it clear that it’s a choice on their part. Or else they don’t know it. It’s understandable since no one teaches it to them.” [For more on this, see Laurent's excellent book, Soccer Empire -- Ed]

The response to Le Pen’s 1996 comments was immediate and resounding: everyone, or almost everyone, called him an idiot. Politicians, pundits, and journalists all piled on, falling over themselves to denounce his comments and declare their love for the French team. In fact he managed to do something rather extraordinary with his comments, pushing a group of athletes – most of whom would likely have never made public political statements about the questions of race, immigration, and identity in France – to become activists of a kind.

Christian Karembeu – from the Pacific territory of New Caledonia – made a decision. “From that on, I didn’t sign the Marseillaise. To raise people’s consciousness, so that everyone will know who we are.” He knew the words perfectly, he explained. “In the colonies, everyone has to learn the Marseillaise by heart at school. That means that I, from zero to twenty-five years old, knew the Marseillaise perfectly.” But when he heard the song, Karembeu explained, he thought “about his ancestors” – indigenous Kanaks who had been drafted in New Caledonia and died on the battlefields of World War I for France. “The history of France is that of its colonies and its wealth. Above all, I am a Kanak. I can’t sign the French national anthem because I know the history of my people.”

One of Karembeu’s teammates, the Guadeloupe-born Lilian Thuram, also experienced the event as a kind of political awakening. He made a different choice when it came to the song: he always sang it loudly, and famously off tune, often with tears in his eyes. But doing so was part of a political stance that overlapped with Karembeu’s: in the next years, Thuram became a powerful and potent voice criticizing Le Pen, and later Nicholas Sarkozy, and advocating for acknowledgment, study, and confrontation with the past of slavery and colonialism. In his retirement, he has – in a move that, to say the least, is not the usual path taken by post-career athletes – devoted himself to anti-racist education, and recently curated an exhibit at the Quai Branly outlining the history of colonial and racial representations of “the Other.”

One of Karembeu’s teammates, the Guadeloupe-born Lilian Thuram, also experienced the event as a kind of political awakening. He made a different choice when it came to the song: he always sang it loudly, and famously off tune, often with tears in his eyes. But doing so was part of a political stance that overlapped with Karembeu’s: in the next years, Thuram became a powerful and potent voice criticizing Le Pen, and later Nicholas Sarkozy, and advocating for acknowledgment, study, and confrontation with the past of slavery and colonialism. In his retirement, he has – in a move that, to say the least, is not the usual path taken by post-career athletes – devoted himself to anti-racist education, and recently curated an exhibit at the Quai Branly outlining the history of colonial and racial representations of “the Other.”

Le Pen’s comments were also a case of spectacularly bad timing. Though France didn’t win the European Cup, a team made up of most of the same players did the unthinkable in 1998 and won the World Cup in Paris. This victory would, in any situation, have been greeted with an outpouring of joy. But thanks largely to Le Pen’s comments – and to the fact that it was Thuram and Zidane – who scored the pivotal goals in the semi-final and final, the event was greeted by many in France as a powerful celebration of a new multi-cultural and multi-ethnic nation. There was an outpouring of comments from all sides that saw, in the team, precisely the opposite of what Le Pen had suggested: a France which, thanks to the contributions of all its different peoples, of all backgrounds, had won a critical victory.

Zinedine Zidane, for instance, reflected on the World Cup victory as a moment of consolidation and reconciliation for him and his family, and more broadly for Algerians and their descendants in France, many of whom waved Algerian flags to celebrate. “There was something very moving about seeing all those Algerian flags mixed in with the French ones in the streets on the night of our victory. This alchemy of victory proved suddenly that my father and mother had not made the journey for nothing: it was the son of a Kabyle that offered up the victory, but it was France that became champion of the world. In one goal by one person, two cultures became one.” The victory was “the most beautiful response to intolerance.” He described the victory as an explicit response to Le Pen: “Frankly, what does it matter if you belt out the Marseillaise or if you live it inside yourself? … Do we have to belt out this warrior’s song to be patriotic?”

It is, perhaps, this Zidane that Benzema was trying to channel in his comments. Of course, they come at a very different time. Zidane could speak from the pinnacle of victory. Benzema speaks in the midst of a long period of relative failure on the part of the French team – the debacle of 2010, the ultimate disappointment of the European Cup last summer, and now an ongoing struggle to qualify for 2014 in Brazil. The current debate about the Marseillaise, too, is haunted by the many controversies surrounding the booing of the anthem during matches pitting France against Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco over the past years. In September 2001, after pro-Algeria fans invaded the pitch during a game against France, Le Pen once again used football as a touchstone for his political campaign, this time with more success. He announced his candidacy for president in front of the Stade de France a few weeks later, explaining he had chosen the site because it was where “our national anthem was booed.” The next year, he made it into the second round of the presidential election, forcing the French to choose between him and Jacques Chirac. The French team mobilized again, with even Zidane urging people to vote against Le Pen.

We might imagine that there is, somewhere in the Front National office, presumably some kind of little file, or perhaps a handbook, on how to take advantage of various incidents on the football pitch for political gain. And one can predict that, like Benzema, future footballers who – because of the accident of their ancestry – are be suspected of disloyalty by French xenophobes will be asked this same question again and again: “Why don’t you sing the Marseillaise?” They’ll be able to look back to find various ways to answer the question, and indeed will have quite the menu: do you politely offer a “Va te faire foutre!” with sauce Karembeu, Thuram, Zidane, or Benzema? Eventually, one might be able to offer an entire seminar on the meaning and performance of nationalism using nothing but examples from the debate about football and the Marseillaise. The field of French Cultural Studies will eventually acknowledge that Jean-Marie Le Pen has been our greatest friend over the years, a generative thinker without whom we might have little to write about.

In the meantime, on the pitch France will need all the help it can get as they are about to take on reigning World and double European champions Spain. Many fans will probably be open to the players using any form of inspiration they might need in order to score some goals and win this critical game, so that they won’t put us all through the usual torture of dragging out qualification until the last minute. (Remember the hand of Henry?)

Do they want to pray to Allah, Jesus, Zarathustra? Be our guest. Invoke their Ancestors the Gauls, channel the spirit of the founder of the World Cup, the Frenchman Jules Rimet, or call down the West African warrior god Ogun? Fine with us. At the end of the game, as Benzema has pointed out, if they’ve scored three goals and pull off a win, no one will remember what they were singing when the game began.

* Laurent Dubois, professor of history at Duke University, blogs at Soccer Politics and is a member of the Football is a Country collective. His book Soccer Empire: The World Cup and the Future of France comes highly recommended.

March 19, 2013

Another Side of the Story: A Discussion with the Managing Editor of “Daily News Egypt”

Post by Sarah El-Shaarawi

I had the opportunity to sit down with Rana Allam, Managing Editor of the Daily News Egypt towards the end of January this year, just days before the two-year anniversary of the start of the Egyptian uprising that ousted Hosni Mubarak. Not surprisingly, the publication’s modest offices, located in the downtown Cairo neighborhood of El Dokki, were buzzing with activity. I was there to talk to Ms. Allam about media representations of Egyptian women, but as the interview progressed, I realized that just as significant was the role that publications like Daily News Egypt play in presenting an alternative narrative to the English speaking audience.

Like many other international English language newspapers, Daily News Egypt serves a distinct purpose. As they describe it on their website, the publication works with “local Arabic sources [to] provide the English speaking world with insight into breaking news, in print and online … to [be] a point of reference on Egyptian current affairs for readers all over the world.” Fittingly, over 50 percent of the publication’s audience is from abroad, and their readership is growing.

While it can be deduced from looking at the content of their website, Ms. Allam articulated that the paper is “on the side of the revolution.” She expressed that the publication tries to be balanced and put all opinions on the table. But, she says, “When you’re objective, you’re just bound to be revolutionary.”

According to Ms. Allam the greatest challenge faced by the paper in achieving objectivity is the silence they face from the government. “Our problem is mainly that the government doesn’t reply. No one replies to you: state security, the ministry of interior, they’re like God, they would never reply to you.” She continues, “it’s quite stupid because we call them to get their side of the story, but they never reply, we can never get their side.”

Perhaps it is stupid, because not only is the readership increasing, but so too is the publication’s reputation, and the caliber of writers coming forward to contribute. Key among them is Shahira Amin, a long-time contributor to CNN’s Inside Africa, and the former deputy head of the state-run Nile TV, who resigned in February 2011, in protest of the channel’s skewed coverage of the uprising.

When I asked Ms. Allam about representations of Egyptians in mainstream Western media coverage, she responded: “I think no one should cover or write about any country, any people, without actually going and living among the people. It is very arrogant to decide to write about a certain society, or certain people, or issue by following reports. Come live here and then write about it.” She continued, “Of course they will never do this, so the only thing [we can do] is try to change these ideas, and this concept of Egyptian society.”

As the interview was wrapping up, I asked Ms. Allam about her preparations for the coming Friday, January 25th – the two-year anniversary of Egypt’s revolution. She responded by expressing her concern for “her girls” – the female journalists who would go to Tahrir Square to cover the protests.

Two years ago, the coverage of what happened to CBS’s Lara Logan, who suffered a brutal assault in Tahrir Square at the hands of a mob, was everywhere. While what happened to Ms. Logan was horrific, Ms. Allam expressed her frustration at the lack of attention given to the perpetual harassment and assaults on female journalists in Egypt. She explained that women journalists have been systematically targeted as a means of intimidation, likely at the behest of the government.

This revelation exemplifies the role of many English language dailies based abroad: while the picture presented may not always be holistic, they represent an intermediary between what is actually happening on the ground and what the English speaking audience has traditionally had access to. The growing readership of publications like Daily News Egypt should be taken as a reason for optimism; that audiences are increasingly diversifying their sources, and that many are in search of a more representative story.

Does Zimbabwe’s new Constitution live up to women’s aspirations?

This weekend, Zimbabwe held a Constitutional referendum. And so Zimbabwe enjoyed yet another 15 seconds of international press attention. Turnout was reported as low. The public was as apathetic, uninformed, and/or disinterested. And the referendum was described as important, especially for women. According to some reports, ‘women’ knew that: “Some women’s rights groups have praised the Constitution for cementing gender equality in Zimbabwe.” According to other reports, voting would “change the lives of Zimbabwe’s women.” Reporters fanned out across some of Zimbabwe and interviewed ‘women’. The women’s responses were mixed about the Constitution, but not about aspirations. The women wanted more than an end to chaos and violence. They wanted sustained and structured peace and progress. How is one to read the reports on Zimbabwean women?

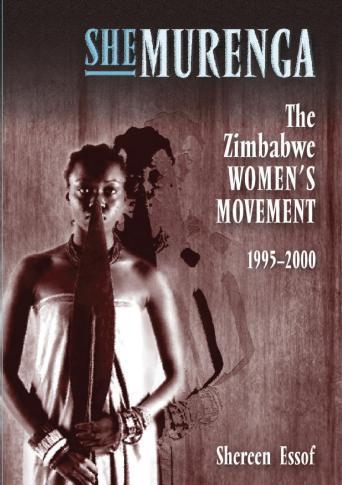

Weaver Press has just published something that might help, She-murenga: The Zimbabwe Women’s Movement 1995 – 2000 by Shereen Essof.

In 2013, when Zimbabwean women talk about ending violence and creating peace, they are participating in a long history of women’s struggle and organization in Zimbabwe; a long and intense history of one step forward, two steps back, in which women organize, make advances, and then are betrayed by both the State and Civil Society.

In the context of the coverage of Saturday’s referendum, two salient points emerge in Essof’s account: the original foundation of the Women’s Alliance, and the post 2000 shifts in the women’s movements.

In 1999, Zimbabwe was undergoing another Constitutional process. Women recognized that they were being denied any serious voice in the charter processes. For example, women comprise 70% of the rural population, and somehow had nothing worthwhile to say about land rights? In June 1999, women organized the Women’s Alliance, to create an autonomous space and place for women. From the outset, the Women’s Alliance was a major intervention into the business as usual of man-to-man and masculinity-to-masculinity. When the Constitution was actually put to a vote, that intervention escalated. The Women’s Alliance launched a campaign against the Constitution and, remarkably, won.

And then were forced back two steps, by a collusion of State and Civil Society. Before the June 2000 Parliamentary elections, the Women’s Coalition had put forth a women’s charter: “It was the first time in the history of Zimbabwe that a women’s agenda had been articulated in this way.” The agenda, as the Coalition, reached across party structures, regional and generational identities, ethnic and religious communities. The agenda, as the Coalition, identified something new, the Zimbabwean citizen-as-woman. This stunning accomplishment was met with stunning violence. One step forward, two steps back.

Since 2000, the women’s movements have shifted: “By the mid-1990s one saw the disappearance of the words ‘oppression’ and ‘exploitation’, ‘patriarchy’ and ‘feminism’ from the movements’ lexicon. It is revealing when one considers the terms that seem to have replaced them: ‘gender’ and ‘mainstreaming’ (…) Feminism was constructed as too inflammatory.”

Essof concludes: “What the Women’s Coalition did was revolutionary: it placed women in a powerful political ‘space’, one that traversed organisational interests and boundaries, and one that until then they had always been reluctant to occupy and claim. (…) Now women were forced to confront the state as a political agent. Despite the contestation, the Women’s Coalition allowed women to make the leap and articulate a women’s politics based on women’s interests.”

Does a women’s politics based on women interests sound revolutionary? It is. As one of Essof’s ‘women conversants’ explains: “The women’s movement is very central to crafting a new politics, a postcolonial politics and this is very central to the vibrancy of the women’s movement, because we are overturning everything.”

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers