Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 481

March 27, 2013

Egyptian Women [are not willing to be] Blamed for Sexual Assaults

One of yesterday’s New York Times headlines addressed the problem of sexual violence in Egypt that has “become too big to ignore”. The article by Mayy El Sheikh and David Kirkpatrick, “Rise in Sexual Assaults in Egypt Sets off Clash Over Blame” (originally titled: “Egyptian Women Blamed for Sexual Assaults”), discusses the ongoing – and seemingly increasingly violent – attacks against female protestors, alongside the clumsy, and at times outrageously misogynistic, comments by government officials and other political actors within the country. In the ever-growing pool of articles being written on the subject, this one proved more representative than most; clearly attributing victim-blaming to the outspoken among the “conservative Islamists”, and focusing on the stories and challenges as articulated by Egyptian women.

Perhaps most importantly, the article gave space for the often neglected voice of Egyptian men who are standing up against the attacks being carried out on their sisters, wives and mothers. Though not mentioned, this inclusion may also help to make space for those men who too have been victimized, a side of the narrative that is almost never addressed.

A portion of the piece tells the story of journalist Hania Moheeb, who was attacked at Tahrir Square on the second anniversary of the uprising. The discussion of Ms. Moheeb’s ordeal includes the caveat: “To alleviate the social stigma usually attached to sexual assault victims in Egypt’s conservative culture, her husband, Dr. Sherif Al Kerdani, appeared alongside her.” While this statement makes a broad value judgment about the nature of Egyptian society, it also helps to dispel the dichotomous portrayal so prevalent in the media: that Arab men systematically oppress and victimize Arab women.

This article has several redeeming qualities, but there are a few points worth keeping in mind: While writing about a television imam calling women “ogres…without shame” and “demons” makes for a good story, we can’t forget the comparable rhetoric that continues to emerge from conservative voices in North America. And while there is no question that the problem of sexual violence in Egypt must be combated, quickly and in a substantive way, perhaps one should question why this was front page news. As an Egyptian academic and women’s rights activist put it to me earlier this year, “stories that are about the body get more coverage in the Western media, whether it’s about veiling, cutting, beating. The Western media is obsessed with the female body.”

The picture of women protesting at Tahrir Square that accompanied the NYT article (above) helps to substantiate her point. At the forefront, a woman in niqab raises her fist in the air; a seemingly endless sea of different colored hijab and Egyptian flags lay behind her. In terms of numbers this image may be representative – that is to say most urban Egyptian women either wear the hijab or choose not to veil. However in terms of focus, this image is not representative. While the numbers of women donning the niqab has increased since Mubarak’s ouster, they remain a minority. On the other hand, perhaps it is a good representation of misrepresentation, and a nice contradiction to the article’s assertion that “by the second anniversary of the revolution…Tahrir Square had become a no-go zone for women.”

Tsofa: A documentary film about Congolese immigrants in Romania

Congolese (Brazzaville) filmmaker Rufin Mbou Mikima has uploaded* his latest documentary “Tsofa” to YouTube. The film tells the story of a group of Congolese men, many of them highly qualified university graduates who got offered a 600 euro/month job by a Romanian company to go and work as taxi drivers in Bucharest, the European country’s capital. “To Romanians, black people living in their country must be either football players, or students,” Mbou Mikima notes in one of the film’s opening scenes. He first met the group back in 2008 while working in Bucharest himself. Through the use of the men’s own photos, mobile phone images and other video material, he retraces their initial steps, hopes and expectations, where it went wrong (it did), and what happened after the return of some of them to Congo (Brazza). Conversations, interviews, voice-over and subtitles are in French and Lingala. (No English subs, unfortunately.) The result is a sensible document. Bonus: music by Fredy Massamba.

* Update: “had” it uploaded; it’s been set to private now. Désolé. Replaced it with an opening scene.

March 26, 2013

Zimbabwe’s Tortured Rule of Law

On Sunday, March 17, a day after the Constitutional Referendum, Zimbabwe arrested Beatrice Mtetwa, leading human rights lawyer and Board member of the Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights. Mtetwa had been arrested for the ‘crime’ of asking the whereabouts of a client. The State refers to that as “obstructing or defeating the course of justice.” Actually, Beatrice Mtetwa is the course of justice.

On Monday, Beatrice Mtetwa was ‘granted’ bail, and now she is ‘free’ to walk the streets, work, and do whatever, right? Not really. She joins her client, Jestina Mukoko, and the tens of thousands of others in Zimbabwe, the walking un-free who have been ‘released’ from prisons, jails, ‘custody’. There aren’t enough scare quotation marks anymore to adequately describe Zimbabwe’s ‘justice system’.

The presiding judge, High Court Judge Justice Joseph Musakwa, explained, “Mtetwa should not have been denied bail by the lower court and the police should have shed light on the nature and scope of the investigations that remained outstanding and that the court should not have denied liberty to a legal practitioner of repute like Mtetwa.”

Mtetwa should not have been imprisoned. While it’s a relief, of sorts, that Mtetwa is on this side of the bars, barely, her imprisonment was and is an outrage. As one Zimbabwean blogger put it, “It’s a relief for her sake that she’s been granted bail. But it’s an insult to justice in Zimbabwe that she was detained in the first place, never mind held in custody for eight nights.”

One would say, “Amen,” except the drama does not end there.

During the week that Beatrice Mtetwa was in prison, Gabriel Shumba was informed that, finally, the African Human Rights Commission had found the government of Zimbabwe guilty of having tortured him, in 2003, and that Zimbabwe owes Shumba more than an apology.

In 2003, Shumba, a lawyer, was “attending to a client”, an opposition Member of Parliament when he was arrested. While in custody, he was subjected to extreme torture and threatened with death. Upon his release, Shumba fled to South Africa, where he became Executive Director of the Zimbabwe Exiles Forum.

Shumba brought his case to the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights in December 2005. The Commission ‘deferred’ any decision until May 2012. For most of those more than six years, the Commission basically did nothing. Better put, it actively deferred looking into the matter. Finally, it decided and then waited, again, until January 2013, when the Executive Committee approved. And then, finally, last week, the Commission informed Gabriel Shumba, during the week that Beatrice Mtetwa sat in prison.

The State violence is not new, but it is news. Where’s the international media on the ongoing situation of police violence and the torture that passes for rule of law in Zimbabwe? They’re in a drive-by mode. An occasional report, a Constitution here, an election there, suffice. There is hardly ever an attempt to linger, to stay, to get at the contexts, which are both brutally simply and, often worse, brutally complex.

As Gabriel Shumba wrote, in 2010: “Zimbabwe has witnessed some of the worst crimes against humanity to be committed on the African continent in recent years… To call for elections when the structures of violence and rigging are still in place is to subject the nation to yet another unnecessary torment… The infrastructure of violence… need to be dismantled.”

What is the rule of law in a regime of torment? Ask Jestina Mukoko, Beatrice Mtetwa, Gabriel Shumba and so many others.

March 25, 2013

What The New York Times forgot to tell you about the Explosion of Digital Music in Africa

Guest Post by Benjamin Lebrave

This morning I started my week reading the following on the New York Times’ website: “Digital music, responsible for the improvement in the industry’s brighter overall outlook, has failed to catch on across much of Africa.” To be more accurate, the first words I read were “Serraval, France”, the location of the writer. Ironically, Serraval’s city hall website starts with the following: “Today, children use the internet much like our generation played marbles.” Well it seems that despite Serraval’s noted efforts to encourage the use of the internet, Eric Pfanner, the great mind behind this piece of in-depth NYT journalism, may have lost his marbles.

Just for comedic effect, let’s continue fact checking for a minute. Pfanner talks about high profile moves, then mentions three artists to back up the significance of the claim: Power Boyz from Angola, DJ Vetkuk from South Africa, and W4 from Nigeria (not even a facebook page for him, all I found was this). Now don’t get me wrong, I LOVE Tchuna Baby, and wish that song were a global hit. But it’s not, and Power Boyz are at best a second tier band. Same goes for W4 or DJ Vetkuk, who may also be talented, but for the sake of this article, are completely irrelevant. No mention of D’Banj, P-Square, or any other proper pan-African heavy hitters.

Maybe they don’t chop money in Serraval…

No mention of Spinlet either, a Nigerian company backed by serious investment money for over a year now. While it is clear Pfanner is green about digital music in Africa, he did however do his homework among Western players attempting to jump on the African bandwagon. But that’s exactly the problem: he relies on PR information obtained from corporations, who rely on consulting firms to do their market research. And those firms rely on information obtained from offices in London, Paris, or at best Johannesburg. Even when they do have some kind of ground office, it is exactly that: an office.

If you want to understand how digital music is evolving in Africa, you first have to step out of the office, and go where digital music lives: in the devices of teenagers. You have to witness how music listening and consuming habits have changed. You have to see how hits blow up strictly from bluetooth swapping. You have to go to concerts, and watch crowds chant in unison to songs which never play on the radio or on TV.

To think that the number of paid downloads is a testimony to the advancement of digital music in Africa is like looking at champagne sales as an indicator of overall growth in Africa. When people live on a buck or two a day, it is slightly unlikely they will spend a buck on a song. But that does not mean they are not living and breathing digital music. That does not mean digital music does not make or break artists, who then go on to get endorsement deals, and a properly lucrative career. Digital is not only the cornerstone of how music lives in Africa today, it is also fundamental in the business of music.

The problem with this New York Times article is nothing new: the general consensus about reporting in Africa seems to be: nobody knows, nobody cares, so let’s just put the smallest amount of effort into it. Let’s rely on the same reporter who writes about Moscato wine and French tax schemes, he’s smart enough, he’ll get it right. And even if he doesn’t, who cares?

Well the irony in this case is: specifically because digital media (and music) is exploding in Africa, a lot of us notice, and a lot of us care.

I have to add one last bit: the main reason for Pfanner’s article is Samsung and Universal’s launch of The Kleek, a music service aimed at African markets. Pfanner tells us digital music is non-existent in Africa, and tells us Universal is jumping in. So that would make Universal a bold, courageous pioneer. Now THAT is good humor.

* Ghana-based Benjamin Lebrave runs Akwaaba Music, a platform promoting and distributing urban and electronic music from all over Africa. He also reports about musical discoveries for Fader magazine and This Is Africa.

Oy & The Art of Translating Between The Stage and The Studio

Africa is a Country has been a fan of Ghanaian-Swiss audio experimentalist Oy’s live performances for a while. Tom’s posting of Hallelujah was my own introduction to her strange but mesmerizing audio-visual creations:

Africa is a Country has been a fan of Ghanaian-Swiss audio experimentalist Oy’s live performances for a while. Tom’s posting of Hallelujah was my own introduction to her strange but mesmerizing audio-visual creations:

A host of other and new exciting tunes will soon be released in recorded form and available to the world. From a music producer’s perspective, I get really excited to hear how such captivating performances are manifested on record. The process of translating a song from the studio to the stage and vice versa is an art in itself, one that not all musicians can do well.

Oy’s sophomore album, Kokokyinaka, is a highly enjoyable journey that inventively incorporates field recordings into digital production techniques. The label’s press release gives insight into the album’s creative process:

The wildly vibrant sample base includes a parachute, fufu pounding, fireworks, and a shoe. Along with all of the animated stories it was mostly collected on trips to Mali, Burkina Faso, Ghana, and during a residency in South Africa. The actual writing and the production for the record took place at studios located in Berlin under the guidance of talented drummer, producer, and co-writer Lleluja-Ha.

Throughout the course of the album we accompany her through her explorations of African cultural intricacies from the perspective of a half-in half-out Afro-European. This makes it easy for comparisons to mixed Afro-European vocalists like Nneka or Anbuley to pop in my head. But, Joy’s album stands apart because instead of straight ahead pop, dance, Hip-Hop or soul album, this project feels like a personal journey that is just as experimental culturally as it is technically.

For more on Joy, check out an interview with her on OkayAfrica.

The Dutch Media Drama

Guest Post by Martijn Kleppe

Guest Post by Martijn Kleppe

Even though the Netherlands have been known for their tolerant attitude towards “immigrants”, the last couple of years have seen several debates about the role of those immigrants in Dutch society. Second and third generations immigrants are often accused of not being integrated enough — a public opinion factor that, not unlike elsewhere in Europe, has added to the rise of several right-wing parties. Some problems are difficult to visualize with photographs. The “problem” with immigrants (in The Netherlands) is one of them. For a while now, I have been fascinated by one picture that is used in all kinds of Dutch news articles.

Especially the Elsevier paper (screen grab below) uses the picture often: in a report on fighting “nuisance” by Moroccan youth in the inner city of Helmond, in a piece about tackling youth crime by the municipality of Amsterdam, in a piece on a remark by Hero Brinkman about Muslims, in a piece about psychological help for dysfunctional Moroccan families, in a report about criminal youth in an Amsterdam neighbourhood and in a blog post by Afshin Elian on criminal behavior among young Moroccans:

The (currently no longer circulating) free newspaper De Pers was charmed by the picture as well. There the image accompanied a report about twelve thousand children whose DNA profiles are kept in database, a report that an imam believes that conversion to Islam can be a solution for many problems of Moroccan “street terrorists”, and a report about homeless youth:

The (currently no longer circulating) free newspaper De Pers was charmed by the picture as well. There the image accompanied a report about twelve thousand children whose DNA profiles are kept in database, a report that an imam believes that conversion to Islam can be a solution for many problems of Moroccan “street terrorists”, and a report about homeless youth:

But that’s not all. Even the consultancy bureau BMC used the photograph in a report about troublesome youth in Amsterdam:

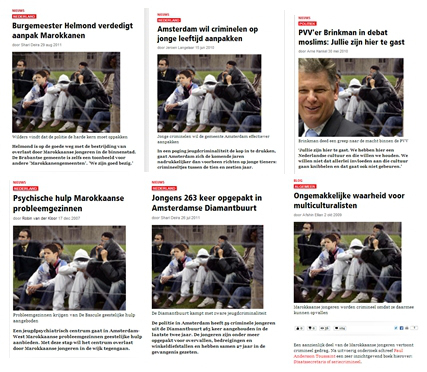

And even then we’re not done. Which photo is on the cover of Fleur Jurgens’s book The Moroccan(s) Drama? Exactly. The photo was taken from a different angle but shows the same situation and the same moment:

And even then we’re not done. Which photo is on the cover of Fleur Jurgens’s book The Moroccan(s) Drama? Exactly. The photo was taken from a different angle but shows the same situation and the same moment:

Now, what are we looking at?

Homeless youth? Criminal Moroccans? Moroccan families who need psychological help? Children whose DNA is kept in a database? Or maybe just Moroccan street terrorists?

It won’t come as a surprise.

It’s none of those.

If you look at the pictures closely, you see that some details tell a different story: the barbed wire in the foreground and a part of a barrack in the background.

When I see barbed wire and barracks, I immediately think of concentration or refugee camps. By typing in those words in the database of the ANP photo archive, I found the original photo. After reading the caption I fell off my chair:

Photo caption: “Some of the group of 350 Moroccan Dutch hide their faces on Monday as they listen to the story of a camp survivor during their visit to Camp Westerbork (a Dutch WWII transit camp used to assemble Roma and Dutch Jews for transport to the Nazi concentration camps – Ed). Little is known about the military role that Moroccans have played during the Second World War or about their contribution to the liberation of the Netherlands.”

So what do we see?

A photo from 2005 showing some of the 350 Moroccan boys visiting the Camp Westerbork. But besides their background, nothing in the picture has anything to do with the news the photo is used for. These are just guys listening to a camp survivor. Even if there has been some “noise” during the visit (see here and here), that’s not what is in the photo. (More photos of the visit can be seen here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here, here and over at the photo agency Hollandse Hoogte.)

Why is this photo being used for so many different stories in which the “immigration problem” seems to play a role?

It remains my speculation but it seems very likely that the editors have an image in their mind when they write a news story. They then search for a picture that matches that image. It is a logical process that I also regularly apply when I search for images to show during a lecture. I then also search for that one photo that best represents the image I have in mind. Chances are that I also occasionally show a picture of something which is not what I think it represents. Everybody makes mistakes.

However from journalists one could expect they also ask themselves the question: what am I looking at? Or at least they should have read the caption that explains what is in the picture. If they would have done so, nobody would ever have published this picture in this context and, above all, this painful misuse of a photo could have been prevented.

* Martijn Kleppe works at the Erasmus University Rotterdam and recently defended his dissertation Canonical Iconic Photographs. The role of (press) photographs in Dutch Historiography (Eburon, Delft, 2013). This post originally appeared in Dutch on Photoq.nl.

Africa 3.0

Another month, another special Africa issue. This one is by French weekly newspaper Courrier International (part of Le Monde group), edited by Isabelle Lauze and Ousmane Ndiaye. Many of the articles have appeared elsewhere but are published here for the first time in French. Features and profiles include those on Congolese photographer Kiripi Katembo, Angola’s “indignados”, Senegalese collective Y’en A Marre, Nigerian Nollywood, Ghanaian journo Anas Aremeyaw Anas, Ethiopian entrepreneur Bethlehem Tilahun Alemu, a very short introduction to Francophone Hip-Hop, etc. Full table of contents here. The cover photo is lifted from Omar Victor Diop’s 2012 series “The Studio of Vanities”. It’s not clear why they decided to focus only on Sub-Saharan Africa. That said, they’ve used excellent sources.

March 23, 2013

Bebo Valdés: 5 films to remember him by

It is hard to underestimate the importance of pianist Bebo Valdés’ contributions to Cuban music. “Bebo”, who passed way at the age of 94 in Stockholm, Sweden yesterday, is considered to have been instrumental in “wedding traditional Afro-Cuban dance rhythms with the improvisational freedom of American jazz” (JazzTimes). His earliest performances were in rumba style but his exposure to jazz in the 1930s “altered the course of his music as he adopted the African-rooted rhythms and the swing of the American big bands to his own playing and arranging.” In 1947 Bebo took a job as pianist-arranger in Haiti, an experience that he says “increased his knowledge of African-based rhythms.” He returned to Cuba in 1948, where he gained fame as the musical director of the Tropicana club in Havana. In October 1952, he did a series of recordings for American producer Norman Granz, a descarga that is considered to be the first Afro-Cuban jazz jam sessions recorded on the island. Following Cuba’s revolution in 1959, Bebo left for Mexico, then the United States, and finally Europe where he settled in Stockholm, playing in piano bars and touring occasionally. In 1994, Cuban musician Paquito D’Rivera sought out Bebo for a recording session, released as “Bebo Rides Again”. The LP’s sleeves has it that this was Bebo’s first recording after 34 years (although that is noted as not entirely correct). Once more, some silent years followed this recording, living “a quiet musical existence,” as JazzTimes calls it in an older article — untill the year 2000, when Fernando Trueba brought together some of Cuba’s great musicians for the film “Calle 54″, and reintroduced Bebo’s playing to an international audience.

It is hard to underestimate the importance of pianist Bebo Valdés’ contributions to Cuban music. “Bebo”, who passed way at the age of 94 in Stockholm, Sweden yesterday, is considered to have been instrumental in “wedding traditional Afro-Cuban dance rhythms with the improvisational freedom of American jazz” (JazzTimes). His earliest performances were in rumba style but his exposure to jazz in the 1930s “altered the course of his music as he adopted the African-rooted rhythms and the swing of the American big bands to his own playing and arranging.” In 1947 Bebo took a job as pianist-arranger in Haiti, an experience that he says “increased his knowledge of African-based rhythms.” He returned to Cuba in 1948, where he gained fame as the musical director of the Tropicana club in Havana. In October 1952, he did a series of recordings for American producer Norman Granz, a descarga that is considered to be the first Afro-Cuban jazz jam sessions recorded on the island. Following Cuba’s revolution in 1959, Bebo left for Mexico, then the United States, and finally Europe where he settled in Stockholm, playing in piano bars and touring occasionally. In 1994, Cuban musician Paquito D’Rivera sought out Bebo for a recording session, released as “Bebo Rides Again”. The LP’s sleeves has it that this was Bebo’s first recording after 34 years (although that is noted as not entirely correct). Once more, some silent years followed this recording, living “a quiet musical existence,” as JazzTimes calls it in an older article — untill the year 2000, when Fernando Trueba brought together some of Cuba’s great musicians for the film “Calle 54″, and reintroduced Bebo’s playing to an international audience.

And this is what YouTube is made for.

The film featured this duet of Bebo and his eldest son, Chucho:

In 2003, Trueba went on to produce the instant classic Lagrimas Negras album, teaming Bebo with flamenco singer Diego El Cigala:

In 2004 he was again filmed by Trueba for El milagro de Candeal, a film about the role music played in the historically black neighbourhood of Candeal, Salvador (state of Bahia, Brazil). A fragment:

In 2008, a documentary was made about his life by Carlos Carcas: Old Man Bebo. Here’s the trailer:

And released in 2010, Chico and Rita is an animated feature-length film directed by, again, Fernando Trueba and Javier Mariscal. The story is set against the backdrops of Havana, New York City, Las Vegas, Hollywood and Paris in the late 1940s and early 1950s and it is inspired by the life of Bebo. The film also has an original soundtrack by Bebo (alongside tracks by Thelonious Monk, Cole Porter, Dizzy Gillespie and Freddy Cole). And here’s the nice part: you can watch it in full on YouTube:

Gracias por la música, Bebo Valdés. R.I.P.

Weekend Music Break

Not too long ago, a new video by Amadou & Mariam would have made a bigger splash. There’s no way denying their (?) questionable choice to get Bertrand Cantat on board for their latest record has somewhat tempered the global enthousiasm for their music. Which is regrettable — the end result is a fine record. And the above animated video for ‘Africa mon Afrique’, produced by No-Mad Films, ticks all the right boxes (including Africa’s launching of a “space program”). Next, Congolese artist Didjak Munya’s latest single, “feat. Bill Clinton” (yeh), before his album drops via Akwaaba, filmed between New York City and Kinshasa:

‘Dance For Me’ by Ghanaians “Ruff N Smooth” Ricky Nana Agyeman and Clement Baafo is a TUNE:

Something else. Let’s get this straight. Tunisian rapper Weld El 15′s track below might not be everybody’s musical cup of tea, but when the “actress” and the cameraman involved in the making of the controversial ‘Cops are Dogs’ video are both sentenced to six months in prison for their contribution to the video while “Weld El 15 (himself) remains on the run and was sentenced to two years of imprisonment in absentia,” Tunisian government needs to be called out on this loud and widely. Says Weld El 15: “As an artist, I chose the (police’s) violent language to criticize their violent behavior and harsh treatment. I tried to express my opinion freely thinking that Tunisia has democracy, yet I was mistaken.” Head over to Les Inrocks for a longer interview with the artist. Surely Tunisia’s Ministry of Interior’s got better things to do. We’ll follow up on this story.

Meanwhile, back in Nigeria, Ajebutter 22′s got other things to worry about. Pastors and stuff:

Abobolais and his Ivorian crew bring the better coupé-décalé moves this week:

There’s been more than one collective musical effort to unite Mali recently. Here’s another one. Featuring: Oxmo Puccino, Inna Modja, Féfé, Cheick Tidiane Seck, Doudou Masta, Rouda du 129H, Ousco, King Massassy, Abbba Mamadou Ba, Lélé, Elie Guillou, Toya, Rim, Ramsès, Lyor, Guimba Kouyaté, Camille Richard, Tanti Kouyaté, Amkoullel l’enfant peulh — many of whom are based in France:

You already know we’re a fan of Carmen Souza. Here’s a video for her ‘Donna Lee’:

Nicole Wray and Terri Walker are touring with (AIAC favorite) Lee Fields this spring. Can’t wait to see them bring this live:

And to conclude, there’s no official video yet for the trans-Atlantic “Family Atlantica” project, but Soundway Records released the following song on YouTube: ‘Escape To The Palenque’, featuring Mulatu Astatke — and that will do for this week:

March 22, 2013

Chinua Achebe The Writer Lives On

By Mukoma Wa Ngugi

“Sir, I am very happy to finally meet you in person – I have read all your books,” a man gushed to my father, Ngugi Wa Thiong’o at the Jomo Kenyatta Airport, Nairobi. My father loves talking with people, but he also does not mind a compliment or two and so we stopped to chat. “Your books, especially Things Fall Apart…”

And on another occasion my friends and I were sitting in a bar in Madison Wisconsin when a drunken student stumbled to our table. “I hear you are the son of that famous African writer?” He asked me.

“Yes, I happen to be,” I replied and sat up straight to cheerfully receive a few proxy compliments.

“We just finished reading Things Fall Apart in class – now that Okonkwo character…”

Suffice it to say then that Chinua Achebe has been around all my life – from the Heinemann Series poster of a smiling, serious, bemused, pipe smoking Achebe that was framed in our family sitting room, to cases of mistaken identity, to my own work as a writer and teacher.

In fact just last month, I was teaching Things Fall Apart alongside Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. The question at hand was – how does Achebe counter and answer Conrad’s Africa? One word comes to mind – voice. To my ear Achebe’s voice is always measured even at its most defiant.

It’s a voice strong enough to speak for a continent denied its voice by colonial racism. It’s the voice of a humble listener who is moved into action by what he sees and hears around him. There Was A Country is as much about Biafra as it is about how Achebe answered the question – what is the role of the African writer in a decolonizing Africa? Jump into your times with both your feet and pen.

Thinking about the African literary tradition and the humility to listen, Achebe never accepted the title, “father of African literature” that we are now forcefully bestowing on him. When asked about it in 2009, he told the Brown Daily Herald that he “strongly resisted” the title because “it’s really a serious belief of mine that it’s risky for anyone to lay claim to something as huge and important as African literature … the contribution made down the ages. I don’t want to be singled out as the one behind it because there were many of us – many, many of us.”

With Achebe, Nelson Mandela and others who have challenged the way we live and think about the world, there will be areas of disagreements. So with Achebe there are questions around his stand on the role of African languages in African writing. Things Fall Apart has been translated into 50 languages – how many of them are African languages? How many of the translations are in a Nigerian language? There is also much to be argued about in regards to his representation of the Biafra war and Ibo nationalism in There was a Country.

But there is a counter-argument to be made that the work of my generation of African writers is to shine a light on his blind spots. We can give Things Fall Apart new lives in African languages. And we should tell our histories in as many different ways as we can so that there are multiple mirrors reflecting our tragedies and triumphs.

The bottom line for me is this – We are all better off because he lived and beautifully wrote his conscience. A writer who has left so much of himself in the world and on whose shoulders others will stand for generations to come cannot be said to be truly dead.

Achebe the man has died. Achebe the writer lives on.

* Mukoma Wa Ngugi is an Assistant Professor of English at Cornell University, the author of Nairobi Heat (Melville, 2011) and the forthcoming Black Star Nairobi (Melville, 2013).

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers