Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 480

April 1, 2013

Afrique 3.0, Version 2.0

Flying back from Dakar and Bamako to my home near “Little Senegal,” I snatched up Courrier International’s special issue “Afrique 3.0″ while passing through Paris. Tom made a quick survey of it just as it hit the newstands. Now that we’ve had a little more time to spend with it, what to make of it? A bit of the old, a bit of the new, some sharp thinking and some shop-worn thoughts. A mixed bag, but all in all, it’s a treat.

For those who don’t know it, Courrier International is a French magazine made up of clippings from the press around the world, most of it in translation. It’s intended to introduce its readers to work they wouldn’t otherwise access, so the art is in the editing. Often they have quite good stuff from the continent, although almost always less of it than you might hope for. Afrique 3.0 is a special issue, devoted–its editors Isabelle Lauze and Ousmane Ndiaye tell us–entirely to the continent south of the Sahara, featuring solely African authors. Sounds like a good idea, although if you’re going to insist on authors who are “born in Africa or the diaspora, whether white, black or métis,” why not go continental and bring in North Africa? As it is, only about half the pieces were first published on the continent, and the other half almost entirely in Europe or the United States.

Even with the broad net they’ve thrown, it’s hard for the editors to avoid the usual suspects, but the mix of fresh and familiar is a good one. Some of those writers are well-known (Breyten Breytenbach, Achille Mbembe, Boubacar Boris Diop, Ngugi wa Thiongo), and some of the voices from a younger generation are familiar, at least in English (Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Dinaw Mengestu). That can hardly be a criticism, since the journal’s purpose is to cross-pollinate, and it does: I didn’t know either Jose Eduardo Agualusa or Mia Couto, who write from Angola and Mozambique, at all. Even some of the English voices are still fresh. I’m always pleased to hear from Afua Hirsch, for one. But what’s “A Kalashnikov and Bare Breasts” you ask? Why, that’s the translated title of Binyavanga Wainaina’s “How to Write about Africa” from 2005. Apparently they managed to translate it without reading it: a few pages later, there is a picture of a Kenyan guy with cattle, bright blanket and a cellphone, as if we were meant to be struck by a juxtaposition that instead seems both entirely natural and visually trite.

Still, there are gems. New to me–and worth the price of admission–were Diébédo Francis Kéré’s architectural work in Burkina Faso and Kiripi Katembo’s fabulous photographs of Kinshasa and Kinois, reflected through standing water (see top image for example). And check out the faux identity cards from Angola marked “citizen in ongoing resistance.” At its best, you might think it was “AIAC” without the Friday music breaks. But let’s not get too excited.

The editors, they tell us, swiped the title from a forthcoming book by South African journalists Richard Poplak and Kevin Bloom. Two problems with that: Is it worse that they’re stealing someone’s thunder (before the other book comes out) or that–not having read the book–the whole idea of Afrique 3.0 seems sketchy in the first place? Afrique 2.0, we’re told, is the Africa of independence. And that was a reboot from Afrique 1.0, which is… the Africa of European colonialism. As Saadiyah said in a comment, “Uhm, seriously?” Fancy meeting you here, Herr Hegel.

The only piece with the same (unintentional) ideological shade is the set-piece debate between the obligatory Dambisa Moyo and Axelle Kabou, who is herself rather a downer. If the question rings false–Afro-optimism or Afro-pessisim? Is Africa rising or falling?–Kabou’s dour realism is a partial antidote to the free market cheerleading and BRIC romances that make up Africa’s latest clichés. In the margins, the editors engage in a running skirmish with The Economist and like-minded business magazines, sending up the Africa rising / Africa falling dichotomy dear to journalists everywhere, but especially snarky British ones. Wainaina says that Africa’s the only continent you get to love. It’s also the only continent you can write about as if it’s an elevator.

“Afrique 3.0″ does manage to get beyond that, after a long tour through the usual places and some of the usual suspects, even drawing AIAC into the line-up (as an internet source). 30,000 feet between Dakar and Little Senegal was just the right place to take this particular trip.

March 31, 2013

What has Steve Bantu Biko got to do with partying and spring in the Netherlands?

What has murdered Black Consciousness activist Steve Bantu Biko to do with the beginning of spring in the Netherlands? Don’t worry, you didn’t miss anything in school. Steve Biko has indeed nothing to do with the new season here whatsoever. Still, this didn’t stop a bunch of yuppies and hipsters to organize a party in his name to celebrate the arrival of spring on Easter Day: Steve’s Party!

The event takes place at the Steve Biko Square in Amsterdam, to celebrate not only the beginning of spring, but–according to the event’s website–also because “the new festival season is just around the corner and the terraces are out again.” And what about Steve Biko himself? Well, in the words of the organization: “on 31 March and 1 April Steve will celebrate his first party.” (Biko, by the way, was born on December 18, 1946)

If you want to give the organization the benefit of the doubt and place your hopes on an intern just having made a stupid mistake without consulting even Wikipedia to learn who the man actually was, well take a look at the poster. It’s the iconic picture of Biko. In a celebratory mood. In an effort to be funny or cool, the entire legacy of Steve Biko has been put aside and all that is left is Biko’s face on a poster donning a ridiculous party hat.

Place to party? Steve Biko Square, the heart of the so-called “Transvaal neighborhood”, surrounded by streets that honor Afrikaner leaders such ad Paul Kruger, Andries Pretorius and Piet Retief. (The peculiar history of South Africa and the Netherlands is something we’ll post about soon btw. And no, it is not just the anti-apartheid movement.) We’re not making this up:

Place to party? Steve Biko Square, the heart of the so-called “Transvaal neighborhood”, surrounded by streets that honor Afrikaner leaders such ad Paul Kruger, Andries Pretorius and Piet Retief. (The peculiar history of South Africa and the Netherlands is something we’ll post about soon btw. And no, it is not just the anti-apartheid movement.) We’re not making this up:

No mention of this coincidence or its significance in any of the party promotion material.

No mention of this coincidence or its significance in any of the party promotion material.

As surprised as I was with Steve’s ‘party’, so too was I surprised to read an article by the Dutch online hipster magazine Hard/Hoofd criticizing the initiative but basically saying that in case of a misplaced enthusiasm and ignorance, a mistake like this might be forgiven since “too often people have appropriated things without any knowledge but not everything can be brushed off with merriments.”

If you by now have turned your head to the heavens above to thank the lord for someone standing up, please just wait a minute, because the saga continues on social media. When someone on the “Steve’ Party” Facebook page asked the organizers: “Has Steve’s Party also something to do with Steve Biko himself? Or should I consider the use of his name and portrait as some kind of ironic hipster appropriation?”, the shit hit the fan. Hateful remarks were made and subsequently deleted, though we can still read some of the reactions (in Dutch). Here are two that caught my eye:

Talk about respect, I find it pretty tasteless to all publicly hate on a group of nice people with only good intentions. Since when is it wrong to organize a free party for the neighborhood?

Or worse:

Come on, it’s only about the name of a party; I haven’t seen any angry reaction from a negro because they too understand that this party has not been initiated because of anti-negro sentiments, quite on the contrary.

Now, this is not the first time something like this has happened in the Netherlands. Back in 2008, a postcard was distributed depicting Anne Frank, the Jewish girl who wrote the Diary of a Young Girl, wearing a keffiyeh. It was obvious that the artist tried to make a political statement with the image, not something we can accuse the organizers of “Steve’s Party” of doing. However, the public outcry back then was totally different. Even up to the point that the Dutch Jewish advocacy group “Centre Information and Documentation on Israel” (CIDI) called for the boycott of the image. According to CIDI, the combination of a symbol of the Holocaust with a symbol of Palestinian nationalism stood as a metaphor for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in which the oppressed, represented by Anne Frank in this case, are the Palestinians. As a result of the upheaval, the postcard company halted the production and sale. (Though some websites still sell the prints.)

[image error]Steve’s Party organizers are having a blast uploading video trailers and hipstagram pictures on Facebook, like nothing ever happened. The only thing to conclude is that in the absence of a strong Black Consciousness lobby group in the Netherlands, chances are slim that the event will be cancelled, or renamed. Happy Easter, Steve.

March 30, 2013

I Sing the Desert Electric: Sights and Sounds from the Sahel

“I Sing the Desert Electric” is a collection of video material shot over the past three years by Sahel Sounds founder Christopher Kirkley in different locations in the Western Sahel (Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Nigeria), representing distinct and highly regionalized musical scenes. The result is a short visual and aural feast. If you want to know more, Kirkley recently talked about his Sahel Sounds project on Radio France Internationale. Here. Boima first wrote about the label here. Volume 2 of “Music from Saharan Cellphones” is now available om vinyl (and so is “Bollywood Inspired Film Music from Hausa Nigeria”).

March 29, 2013

Bonus: Friday Music Break

10 new music videos to finish this week of blogging. Here’s a first video by photographer and graphic designer Laurent Seroussi for Salif Keita’s new Tale album, produced by Gotan Project’s Philippe Cohen-Solal: Vimeo clip above. (The YouTube version of the clip seems not to be available everywhere. Weird Record Label Thinking.) Next, a glorious video for Carlou D’s “Dooley Beuré” that switches into second gear halfway in (Carlou D, of Positive Black Soul fame, talks a bit about the making of the video here):

Faada Freddy (real name: Abdou Fatha Seck, 1/3rd of Senegalese rap combo Daara J) jamming on “Borom bi” with the Clef de Sol choir:

A music video Didier Awadi shot for “Supa Ndaanaa” during a tour organized by the people behind The United States of Africa documentary in Canada last summer. There are plans for Awadi to return to Canada with his musicians later this year:

Napoleon Da Legend’s got a new video out (here), but the one below’s from last year: he was born in Paris (to parents from the Comoros), later moved to New York which, by infallible Afropolitan logics, makes him an “African in New York”:

Rock’n’raï (whoever coined that term?) by Algerian-French Rachid Taha. For accolades, check his official — hilariously puff-toned — profile. This English and Arabic duet cover version (feat. Jeanne Added) of Elvis Presley’s “Now Or Never” is a polished but intriguing production:

Samba Touré introduces his new EP, ‘Albala’, recorded at Studio Mali in Bamako in the autumn of 2012. Also featuring are Djimé Sissoko and Madou Sanogo, with guests such as Zoumana Tereta and Aminata Wassidje Traore:

Petite Noir and his band played a session for a Brussels radio, in one of the city’s most respected venues (Brussels’ the city where he was born before moving to South Africa):

Just in case you still had any doubt, 2013 will be Laura Mvula’s year:

And here’s Yassiin Bey looking sharp at The Shrine (Chicago):

The TEN CITIES Project: Club Culture and Dance Music

“In Africa today, musicians keep in touch with global pop culture via the Internet and program locally flavoured music of explosive creativity, which in turn often finds its way back into the western world: powerful, urban and contemporary club music.” This sentence captured my attention while I was reading the Ten Cities brochure. Ten Cities — organized by the Goethe-Institut “in Sub-Saharan Africa”, Adaptr and a network of European and African partners — involves 50 DJs, musicians and producers from Europe (Berlin, Bristol, Kiev, Lisbon and Naples) and Africa (Johannesburg, Cairo, Luanda, Lagos and Nairobi), allowing them to collaborate and share their respective knowledge about club culture and dance music genres.

“In Africa today, musicians keep in touch with global pop culture via the Internet and program locally flavoured music of explosive creativity, which in turn often finds its way back into the western world: powerful, urban and contemporary club music.” This sentence captured my attention while I was reading the Ten Cities brochure. Ten Cities — organized by the Goethe-Institut “in Sub-Saharan Africa”, Adaptr and a network of European and African partners — involves 50 DJs, musicians and producers from Europe (Berlin, Bristol, Kiev, Lisbon and Naples) and Africa (Johannesburg, Cairo, Luanda, Lagos and Nairobi), allowing them to collaborate and share their respective knowledge about club culture and dance music genres.

Recent projects such as Damon Albarn’s DRC Music in the Democratic Republic of Congo or Dj/rupture and Maga Bo’s Beyond Digital in Morocco are great examples of possible ways of creating bridges between the Western and African musical discourses, where collaboration more than study, is the keyword.

If behind these two cases we always find an author, with his specific interest and obsessions, behind the Ten Cities project there are considerable institutions and a whole team of researchers, photographers and local scouts. I decided to interview the project’s creator Johannes Hossfeld.

How was the Ten Cities project born, both theoretically and productively?

The project came out of different threads of interests. On the one hand, we here at the Goethe-Institut in Kenya have been fascinated by the global phenomenon of club culture, particularly in Africa, and had specialized a bit in musical cooperation projects and wanted to carry this further, together with our Berlin friends from Adaptr. At the same time, we had been doing quite a lot of projects in the city of Nairobi, its urbanism, its sociopolitical spheres and cultural flows. We got more interested in the issue of the public sphere and wanted to set up a project that would unpack this notion of political theory again. The public sphere has been conceptualized in the framework of what Nancy Fraser calls “the bourgeois masculinist Eurocentric bias of the theory” and focused on very specific, rational and word-based communication spheres. But what about those public spheres that are actually not formed by language, but rather by practices of sound and the body?

For instance, what happens when people meet in music spaces at night to party and dance? Entering a club in whatever city, it is very difficult not to see in it a crucial public sphere in that society. At the same time, urban studies usually take prominent, often Western cities as paradigms for the discussion. What about cities like Luanda or Kiev, Naples or Nairobi, and how exactly is a polis formed on these locations? In this project, we attempt to take a look at club cultures as public spheres, in ten very different specific locations in the world. And produce new music. Therefore, the project has two parts: a research part and a music cooperation part.

A couple of years ago I interviewed the researcher and art curator Sarat Maharaj; talking about rave and club cultures, he said that the “encounter with total strangers in the rave produces a kind euphoric relationship between them, an erotic relationship, in the sense that is far more concerned with the sharing of subjective emotional duration.” Are you trying to consider what club culture can generate globally, theoretically?

A couple of years ago I interviewed the researcher and art curator Sarat Maharaj; talking about rave and club cultures, he said that the “encounter with total strangers in the rave produces a kind euphoric relationship between them, an erotic relationship, in the sense that is far more concerned with the sharing of subjective emotional duration.” Are you trying to consider what club culture can generate globally, theoretically?

Yes, but perhaps I’d like to rephrase it a bit: we are trying to consider what club culture has actually generated, but in different places around the world. The project is conceived as one that does not try to make general claims but instead looks carefully at the effects that club music and its subcultures have had in precise locations. Perhaps the relationship that Maharaj was talking about entails more when considered in the context it is experienced. The spheres it has formed might have acquired, in many places, an even more political meaning, from the micro-politics of everyday life to openly oppositional positions.

I read in the Ten Cities brochure that “23 researchers will work on essays and studies about those partly unknown music scenes.” Can you tell us who is going to be involved and how? Are you taking into account only the African cities involved in the project or also the European ones?

The research part tells the history of the public spheres that have been formed around club music, in ten cities, from the 1960s up to now. What did these subcultures and communities look like? What were their codes and practices? What spheres of togetherness and polis did they create? Which emancipatory political and social possibilities were realized, or not? Which kind of spaces did these scenes use, occupy or appropriate? Of course, this is only possible on the basis of a sound knowledge of club music in these cities. From our friends in the ten cities we found out that neither the history of club culture nor that of club music has been written there yet, not even in some of the European ones – the exception is perhaps Berlin, where a lot of writing has been published on particular aspects of club culture.

Hence, two articles per city. The point here is that 20 authors in two groups are working on the same topics, in ten different locations.

The participating writers are all from the city they are writing about. Per city we have some of the most interesting writers of these scenes involved, such as Joyce Nyairo and Bill Odidi in Nairobi, Rangoato Hsasane and Sean O’Toole in Johannesburg, Vitor Belanciano and Rui Miguel Abreu in Lisbon or Iain Chambers in Naples.

At the last Womex edition there was for the first time a panel dedicated to the so-called “global bass” genre, entitled “World Music, Global Bass, And the Future of Hybrid Music” (moderated by Akwaaba Music’s Benjamin Lebrave). Do you think that these forms of contemporary club music are starting to receive more attention globally and do you consider Ten Cities an attempt to reach this goal?

At the last Womex edition there was for the first time a panel dedicated to the so-called “global bass” genre, entitled “World Music, Global Bass, And the Future of Hybrid Music” (moderated by Akwaaba Music’s Benjamin Lebrave). Do you think that these forms of contemporary club music are starting to receive more attention globally and do you consider Ten Cities an attempt to reach this goal?

In the case of Africa, that’s definitely the case but it is very recent. Although it’s important to notice that the African cities have always had vibrant club cultures. Today, the club music produced in these cities gets more and more known by a European audience. But there have been hardly any real cooperations (except perhaps between Lisbon and Luanda). Our aims are, yes, global attention, but more importantly: setting up more connections between producers and musicians. And whatever comes out of it.

Can you explain how you went about the process of selecting and grouping of the partcipants? Did you work with, say, local scouts for each city involved?

Indeed this is what we have been doing. In each city, we have one local curator who selects the participating musicians, such as Blinky Bill from Just a Band in Nairobi, Afrologic in Lagos, Batida in Lisbon and Rob Ellis in Bristol and so on. We then collectively decided that the producers from one city would travel together. Hence, the pairings of cities.

Lisbon and Luanda are for historical reasons well linked, and so are their contemporary music scenes. What did you consider in building bridges between European and African cities and their respective delegates?

In our experience of collaborative projects, this mix of connectedness and difference creates the most intense productions. Our team in Nairobi and Adaptr in Berlin tried to match producers and musicians who can relate to each other but who are also working in ways that differ enough from each other. Hence not Lisbon-Luanda. Instead, we paired Batida from Lisbon and Just a Band from Nairobi because both make very different music while sharing an interest in the musical history of their city and experiment how to include it in their contemporary practice.

It’s important to point out that bridges are not built here by workshops. The European guys are not teaching anything to the African colleagues. That would be ridiculous. The bridges are built by producing music together. The symmetrical and equal exchange is crucial here. And this exchange has in our experience always been as important and productive to the Europeans as it is to the Africans.

Lastly, I was wondering which forms of restitution are you going to take into account. In this sense, what’s the role of photography in the process?

The photographers, in some of the cities, will be working on exactly the same topics as the researchers, just in their own artistic medium. With this, we are trying to complement and frame the music production and the discourse module. It is also an interesting facet because photographers tend to be prominent protagonists in the currently booming, very lively African art scenes.

Follow Ten Cities via their Facebook page and on Soundcloud, where you’ll find some of their DJ sets, such as the following one recorded in Johannesburg @ King Kong:

Popstars Politics in the New South Africa: A Conversation with Masello Motana

South African actress/singer/writer Masello Motana has had a career in the entertainment business that many would envy. She has played a leading role in a number of South African television shows as well as in a mainstream feature film. Her poems have been published in several anthologies in that country and she regularly amazes audiences as a musical performer. Sounds like the good life. Well, life would be much simpler for Masello if only she was content with collecting paychecks from beauty contracts and soap opera gigs. If only she pretended last year’s horrific massacre of mineworkers at the now infamous Marikana platinum mine in South Africa’s northwest never happened. If only she ignored the fact that businessman Cyril Ramaphosa, board member of the company that operates the Marikana mine, was elected to deputy president of the country’s largest political party, the ANC. If only she had kept her mouth patriotically clasped about social and economic inequality in South Africa.

South African actress/singer/writer Masello Motana has had a career in the entertainment business that many would envy. She has played a leading role in a number of South African television shows as well as in a mainstream feature film. Her poems have been published in several anthologies in that country and she regularly amazes audiences as a musical performer. Sounds like the good life. Well, life would be much simpler for Masello if only she was content with collecting paychecks from beauty contracts and soap opera gigs. If only she pretended last year’s horrific massacre of mineworkers at the now infamous Marikana platinum mine in South Africa’s northwest never happened. If only she ignored the fact that businessman Cyril Ramaphosa, board member of the company that operates the Marikana mine, was elected to deputy president of the country’s largest political party, the ANC. If only she had kept her mouth patriotically clasped about social and economic inequality in South Africa.

But for Masello, silence represents complicity in injustice. She has chosen instead to creatively critique the disconnect between South African leaders such as Ramaphosa and the South African people. Out of this critique was born Masello’s satirical alter ego Cyrilina Ramaphoser, fat cat playgirl extraordinaire. In this narrative of Masello’s design, Cyrilina is a singer in search of pop stardom. Cyrilina’s first single “Makarena on Marikana” celebrates the wealth and decadence of some of South Africa’s leaders who would rather focus on turning the country into a McDonalds drive thru than be troubled by the voices of mineworkers and the unemployed.

For the launch of Cyrilina’s new video for “Makerena on Marikana” (below), we linked up with Masello to ask her a few questions about Cyrilina, the personhood of politicians and the future of the South African project. First the video:

“Makarena on Marikana” – How did you come up with the idea for this song?

I am crushed by the ANC’s latest enigmas. Electing Cyril Ramaphosa as their deputy after Marikana. I cannot get over it. I went into a deep depression once I realized that he had every intention of not only attending the conference, but in getting elected into the executive and even the highest position possible. All this barely a hundred days after those bodies had been buried. It’s like someone raping your cousin, then coming to your party, and having the biggest slice of cake and the best booze. I went into a deeper depression than the one I went through after the massacre itself. As for the media! Cheering on as it usually does with capital lubricants like Ramaphosa. I could not in all good conscience see how I could live in such a country. So it was either Cyrilina or exile.

Did you collaborate with anyone else to make the song?

Yah, the Mkhonto Crew, who in storyline terms “produced” for Cyrilina’s former girl group, CAPITAL LUBRICANTS, which included Patricia Motsepe and Tokyolina Sexdolphin.

Why did Cyrilina go solo?

Because she is too big a star to share the limelight, much like Beyonce was before her solo release. The girls are still friends though.

I’m sure they’ll still share insider secrets. So is Mkhonto Crew named after Umkhonto weSizwe, the armed wing of the African National Congress?

Yep! The very Mkhonto! Yes, they share everything! They even go to the same vet. Cyrilina has a pet buffalo, Tokyolina a rhino and Patricia has a snake!

Many of your characters take on the opposite gender of the people you are critiquing — Cyrilina appears to be a party girl representation of Ramaphosa the man. Can you explain why these characters take on the opposite gender?

Attending all-girl schools, I always had to play male characters. So it’s funny when I play the “female lead”, parts which are written to support and affirm the “male lead” in my career. So with my own work, I choose to own the femininity by playing the “girl versions” of very powerful men and at the same time depreciating them sexually the way women are in art in general. Femininity like masculinity or anything else in this country is a contested terrain. I don’t have time to fit into those silly boxes of what “women” should be or how they should behave. It’s clear there is a long held practise of objectifying women which leads to the dismissal and abuse. I can’t really say much on masculinity, it’s about time men themselves express and question this on a broad scale and not just in journals. Women live in a state of emergency in this country and we can scream, dance, wear ribbons…nothing will change till men themselves commit to changing their perceptions.

Is this just the beginning of the world that you’ve created? Will we get to learn more of Cyrilina’s storyline?

Is this just the beginning of the world that you’ve created? Will we get to learn more of Cyrilina’s storyline?

Yes we will! I am expanding the concept into a web show. Still hustling a couple of things to get it done. So the “Lubes” will be a major part of the show. I was working with Julia Malema before this and I felt that I needed someone else for this particular message.

Sounds very exciting. Who else would you like to be involved with the project?

A couple of visual artists, stylists, make up for my different characters. It’s risky work so I can only work with those who are prepared to lose contracts and not get commercial work. I am inspired by Eddie Murphy’s style of playing multiple characters.

Speaking of risks, you haven’t been shy about participating in protest movements for improving the livelihoods of South African workers, has being outspoken about your social and political views affected your career?

I got disillusioned with the rainbow lies longtime ago. I decided more than a decade ago that this was my direction. Social injustice is more worrying to me than my “career”. I will use whatever platform available to push a pro-people agenda.

So in South Africa, the home of humanist ubuntu philosophy, various languages have their own inclusive terms for “people”. When the nation’s leaders act selfishly and unethically, do they forfeit their personhood?

Yes! Absolutely. U have hit the cow on the horn as the bay swans say. The term ubuntu (humanity) is not separate from Ubuntu (human being). So ubuntu is not about being nice to others, but the state of the human at all times.

Yet, the unsavory accumulation of wealth still appears to be enough for some leaders to sacrifice their humanity. What are the consequences of choosing capital over people?

Marikana.

In response, we get Mamphele Ramphele aka Venus Capital Flytrap saying, “We want an MP for Marikana, we want an MP for De Doorns and an MP for Sasolburg.”

NO! NO! NO MAMA! We don’t want Marikana at all, nevermind an MP! We want the structure of ownership in De Doorns to change totally not just have an MP! Hayi suka man! This lady is only good for the skhothanes with degrees and she is still anti-labour! MP in Marikana! Smh! A gang-star of capital nje!

I take it you’re not an instant convert to Ramphele’s newly launched Agang party then?

I take it you’re not an instant convert to Ramphele’s newly launched Agang party then?

Not at all! It’s A Capital Gang.

Does Ramphele have anything to offer in terms of diversifying the political conversation or is she a wolf dressed as a sheep?

The only difference between Ramphele and Ramaphosa is that she wears a bra. Most of those middle class do not even know her history at the IMF. I was disillusioned with her from those days. And she only quit her chairman-what-what role at Goldfields recently.

With the daily toyi toying (protesting) in South Africa that leaders are content to permit, then quickly ignore, how can people influence real social change?

Real social change? Burn and watch the phoenix ashes rise.

The new South Africa has groomed me to be an anarchist. A lot of people say, “we don’t want to be another Zimbabwe” or “at least we avoided a civil war”…Those are hectic statements. We avoided a civil war yet sustain internal bleeding and madness. This aspect is not even entertained in the so-called national narrative.

That’s an interesting metaphor, the people as a body. How do you envision the people redesigning the society?

With a pro-people, pro-life, aim. Politics needs to answer to hunger and not the economy. So real back to basics.

I am wary of speaking for the people even if my job as an artist is to speak on their behalf or to them. I no longer recognize the people themselves…they are lost to the oracles. If u get what I mean…

It’s idealistic of me to want to redefine the world when the very people I feel I need to fight for want to pray for jobs…which is why I urge for more radical arts messages as we (the artists) and the people have lost each other completely.

You mean the work that many artists are making fails to connect with people?

The mediocre artists get all the play, thus numbing the populace to “artists” like Chomee and Danny K. So anyone with a message is seen as boring and has no chance to be heard at all. We love mediocrity in this country.

When I was a journo at City Press, I raised this and my piece was edited into a PR piece. And this was years ago, before I even got onto my first show.

While we’re talking about journalism, how do you feel about the Protection of Information Bill?

While we’re talking about journalism, how do you feel about the Protection of Information Bill?

(Silence)

Well, perhaps that question is a bit too obvious.

Slightly hey…

When socially conscious artists like you put out critical material, it is not always received warmly by the public.

It’s never even fed to the people…

Are the channels of communication blocked for subversive material?

Yep. Before the art is even made.

What would the response be if Cyrilina’s song was broadcast on the radio across the country?

Hmmm….it will probably get called “disrespectful”. I can only know the reaction once I get the actual civilian response. I will most certainly do more live performances of Cyrilina soon. So more videos will come from that after this one.

Have you begun writing other Cyrilina songs as well?

Yep…and some crazy ideas for the wild cats… The wild cats are Cyrilina’s nightmare in life, they always wanna sing where she is, going on about hunger and all these things that are highly irrelevant to a capital lubricant. They have been unseen for a while so they seemingly “pop out of nowhere” but they have been there all along…like embarrassing family members. They are lazy and uneducated, and they expect to have it easy like the fat cats. Talk about a sense of entitlement.

So, wild cats vs. fat cats.

Uh-huh…but for the album, it’s Cyrilina vs. wild cats coz she is a Super Lube and she represents all the hot girls, Patricia, Tokyolina and Jackie Mthembu.

How did you come up with the name “Capital Lubricants”?

How did you come up with the name “Capital Lubricants”?

Every time I hear the word “foreign direct investor,” I think foreign direct rapist with our elite as the lubricants. Like in the line in the song: “take the gravy from the queen and she has all the meat…”

Recently you’ve performed live with Afro Galactic Dream Factory (photo above), Thath’i Cover Okestra and solo at Summer Sundaze in Cape Town, what material do you use for your live performances?

Depends what the mood is. Thath’i Cover was an exploration into kwaito music from a jazz perspective. I love mixing up genres.

Then Afro Galactic was a range of material. There is a Setswana/English poem, “African Sky Boat” by Lerato Themba Khuzwayo and Nature Boy.

Summer Sundaze is more, intimate cabaret style…Sophiatown set with storytelling/jokes in between, or a mellow set with interpretations of club hits as vocal jazz numbers like “Closer” (Rosie Gaines) or “Higher and Higher” by Brenda Fassie.

Have you made recordings of the mellow/intimate songs?

No. I don’t like recording. I love performing and I don’t do the same show twice. So I take a real organic approach.

Random fact, I do believe I am related to Shirley Bassey, Eartha Kitt, Grace Jones, Assata Shakur, Nehanda and Nzinga…

A divine lineage.

Erm…yah, on some rolling stone tip.

If Cyrilina successfully transformed South Africa into a McDonalds, who would be at the register, who would be at the drive thru window, who would be in the back preparing food and who would be cleaning up after everyone?

If Cyrilina successfully transformed South Africa into a McDonalds, who would be at the register, who would be at the drive thru window, who would be in the back preparing food and who would be cleaning up after everyone?

Hahaha! Register — Jacquiline Zuma for her excellent customer service skill; drive through — Jackie Mthembu so that we can also sell booze, food (u still think mcMarikana has real food?); cleaning up — Lester Moneywell.

What’s on the menu?

McMarikana, the biggest selling special at the moment, buffalo piss (with loads of donations from Loni, Cyrilina’s pet), RDP quarter pounder (with cheese if u don’t have a car, shame), miner ribs etc. Ho monate.

Final question, when the dust of revolution settles and the new day’s phoenix rises, how will the people of South Africa determine their future?

That’s a tough one…I know what I would like but am not sure if it’s what we all want. Will we still think of ourselves as a “nation” or rather as autonomous sub divisions? I can’t predict that, I can only sow seeds.

One thing is for sure, by the end of the year, young Africans have to get the African Union to step down. So many years and they could not figure out hunger, now the Chinese are building them meeting rooms, what a disgrace! They are just like those useless video vixens aka the ANC Women’s League.

At times, I think we are pushing too hard and that shit won’t change and that drives me crazy. So what do we do? Can we honestly urge for a revolution when our people are praying for jobs and drinking once they have them I don’t know. All I know is that the truth needs its fifteen minutes of fame.

March 28, 2013

The Trouble with the Dutch Commemoration of the Abolition of Slavery

On the first of July this year the Netherlands are commemorating the 150th anniversary of the abolishment of slavery in their former colonies Suriname and their dependencies: the Dutch Antilles. The mayor of Amsterdam considered it a good time for a celebration. So he decided to think big and invited the US First Lady Michelle Obama, writers Toni Morrison and Alice Walker and former black panther activist Angela Davis. However, looking at the politics around slavery and its commemoration, one may wonder whether we should cheer for this step taken or if we should question why exactly these African American speakers are invited. Don’t get me wrong; I would love to see these admirable women in Amsterdam, but where are the prominent speakers from our communities?

On the first of July this year the Netherlands are commemorating the 150th anniversary of the abolishment of slavery in their former colonies Suriname and their dependencies: the Dutch Antilles. The mayor of Amsterdam considered it a good time for a celebration. So he decided to think big and invited the US First Lady Michelle Obama, writers Toni Morrison and Alice Walker and former black panther activist Angela Davis. However, looking at the politics around slavery and its commemoration, one may wonder whether we should cheer for this step taken or if we should question why exactly these African American speakers are invited. Don’t get me wrong; I would love to see these admirable women in Amsterdam, but where are the prominent speakers from our communities?

The Dutch politics around slavery and its commemoration are rather sketchy. For one, the country’s only research institute based in Amsterdam, the Nederlands Instituut voor Slavernijverleden (Institute for the Study of Dutch Slavery and its Legacy — also known as the NiNsee), has experienced heavy budget cuts last year and was not able to carry out its main activities any longer. Luckily the local government came to the rescue and ensured funding until the end of this year. The timing is — and I am putting it mildly — unfortunate as, again, 2013 marks the 150-year commemoration of the abolition of slavery in the Netherlands. Dr. Artwell Cain, former director of the NiNsee, explained to me that the institute has been silenced through this move. Dr. Cain identifies a strong political trend in the Netherlands that seeks to regulate what is being said about slavery and by whom and sees the heavy cuts as a testament to this claim.

The Dutch government formally abolished slavery in the Dutch colonies, Suriname and the Dutch Antilles, on the 1st of July 1863. This day is widely known as Keti Koti, which means “breaking the chains” in the Surinamese language. Every year the NiNsee co-organises the so-called Keti Koti festival.

But through inviting prominent guests such as Michelle Obama to speak on slavery, the Dutch continue to distance themselves from their own history in which slavery played an important role. The ‘Golden Age’ and the Dutch East India Company (VOC) are glorified in the dominant historical narratives, TV shows and museums, hardly ever mentioning one word about slavery.

The legacies of slavery and the commemoration processes in the US cannot be compared to those of the Netherlands; yet through inviting these speakers it seems that a connection is being made.

Until recently slavery was not even included in the national historical canon and you would be lucky to learn anything about it in school. The NiNsee in collaboration with other schools contributed two chapters to the official historical canon, which they hope will be incorporated in the curriculum soon. It should be noted here too that slavery and its history are often only connected to Suriname and the Dutch Antilles but — as I mentioned in a previous post on the history of African Art in the Netherlands – people seem to forget that the Dutch were also rather active in Ghana and South Africa back in the day. The Cape Settlement in which the VOC played a major role is still often perceived as a mere pit stop.

Luckily we now also have an alternative and historical Black Heritage Tour in Amsterdam that teaches us about the contributions of the African Diaspora to Dutch society, dating back from the 16th century to the present. Historian Sandew Hira has heavily criticized the knowledge production around slavery in the Netherlands because of its ‘Eurocentric perspective’. In the Netherlands, we never seem to focus solely on the history of Dutch slavery. Popular culture, debates, plays and manifestations continuously connect Dutch slavery history to modern slavery and by doing so the actual history — which we know so little about — is being dismissed. For instance, Hira criticized a Dutch TV series called ‘De Slavernij’ (The Slavery) because by linking Dutch slavery to modern slavery in general it made two mistakes. First, the Transatlantic Slave Trade was sanctioned by states and not by private entities. And second, modern slavery today is not the foundation of rising world economies.

The question of a formal apology and reparations for slavery remain contested issues here. Many wonder whether the government does not offer an official apology because of the possibility of subsequent legal implications — but this is not the case.

Some also perceive it as problematic that the Surinamese government is not welcome to the commemoration. The Dutch government does not approve of Suriname’s democratically elected president Desi Bouterse, who is a former military ruler and has been accused of killing 15 top opponents of his military government in the 1980s. And on top of that he has been sentenced in absentia to 11 years for being complicit in smuggling cocaine to the Netherlands. Although Europol has issued an international warrant, being head of State, Bouterse enjoys immunity and has not been arrested.

It is clear that slavery, its legacy and its commemoration are not high on the public agenda. Dutch-Caribbean cultural critic Egbert Alejandro Martina shared his views with me as he is not impressed by the commemoration events, or the lack thereof, organized by the Dutch government. “There are very few events taking place, and most of them, like the one in Rotterdam, seem haphazard and ill advised. What is more, this year also marks the 200-year anniversary of the Dutch Kingdom — and the events planned to celebrate this occasion have already eclipsed the commemoration events in honor of the abolition of slavery in the Dutch West Indies (Suriname and the Caribbean islands were part of this). Perhaps I am being overly cynical, but I think that there’s so little being done because there’s nothing to gain, nothing to feel good about, for the dominant culture.”

The main problem seems to be that we are not sure what exactly we are remembering or forgetting on the 1st of July. There is a strong focus on the abolition but we seem to know very little about what actually happened before, during and after that. Martina reminds us of the history lessons we never got when he questions why slavery was abolished in the Dutch West Indies 3,5 years later than in the Dutch East Indies (what is now Indonesia). “Slavery in the Dutch West Indian colonies was abolished simply because it was not profitable to continue it.” Since the abolition had nothing to do with nations and slave owners ‘feeling guilty’, Martina stresses the importance of commemorating ancestors. “Abolition did not restore our, nor grant us, humanity. Our ancestors had to work for another 10 years — for free — under some bogus apprenticeship. We had to fight for our humanity.”

Image by JT: The National Slavery Monument (Oosterpark, Amsterdam).

Egyptian Graffiti and Gender Politics: An Interview with Soraya Morayef

Hanaa El Degham, mural on the wall of the Lycée Français, Cairo. Copyright suzeeinthecity.wordpress.com.

Mickey Mouse is pulling apart a bomb: inside is the torso of George W. Bush, and they’re both looking perfectly happy about the whole thing. Soraya Morayef is taking a photo of the wall where these figures are painted, on a busy street in downtown Cairo, when a man walks up to her and asks her what the picture means.

‘I think that’s Mickey Mouse,’ I say helpfully.

‘Yes but what does it mean? And who is that man next to him?’

He’s bald with a graying walrus moustache, probably in his mid-forties, his full cheeks sweating as he fans at his pin-striped pink shirt.

‘I’m not quite sure,’ I say politely, wishing I could go back to my camera, but he appears adamant for an answer. ‘Maybe it’s a president? It could be George Bush.’

‘Yes but what is George Bush doing with Mickey Mouse? I like this picture, I walk past it every day, but I wish there’d be some writing explaining it so that I could understand.’

She is stuck between the wall and the man, who tells her he was in Tahrir Square (a stone’s throw away from where they are standing) every day of the uprisings, “one of the shabab of the revolution…”. Eventually, after he has given her his number, he leaves, and she recommences her task, cataloguing the street art in Cairo, a city in which graffiti has flourished since 2011, but where the wall may have been white-washed the next morning.

Morayef is a journalist and writer based in Cairo. Since June 2011 she has been blogging at suzeeinthecity.wordpress.com, where she posts images of street art, with captions and analysis. The same urgent questions — of graffiti and gender, intimidation and interpretation — resurface in a recent post, ‘Women in Graffiti: A Tribute to the Women of Egypt’, on the participation of women in making graffiti on the walls of Egyptian streets.

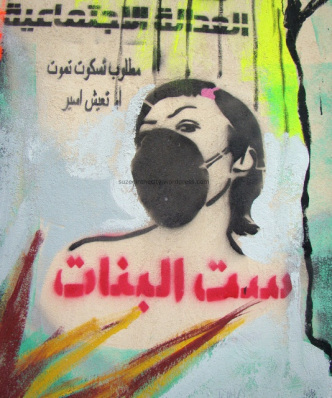

Sit El Banat, stencil tribute to the women who were beaten, dragged and stamped on by military forces in December 2011. Copyright suzeeinthecity.wordpress.com

The artists mentioned include Aya Tarek (“one of the pioneers of graffiti in Egypt”), Hend Kheera (“the first Egyptian graffiti artist to be profiled by Rolling Stone”), Bahia Shebab (an artist and art historian behind the project, A thousand times no), Mira Shihadeh, Laila Magued (more of her work here), the Nooneswa collective, and Hanna El Degham, whose work on the wall of the Lycee Morayef describes as “one of the most astounding street artworks I have seen in Egypt.” The article also includes images of the tributes — by artists Alaa Awad, Keizer, Zeft and Amr Nazeer, X4SprayCans and Ammar Abo Bakr — to Egyptian women, their role in the protests, works made in outrage at the men who have harrassed and attacked them.

The world has been fascinated by the explosion of graffiti in Egypt, and the walls have become signifiers for revolutionary desires, and the street a place where art makes demands of its public, everyday. The precariousness of this art makes Morayef’s catalogue of images necessary, and it has become the visual archive of an emancipatory politics, expressions of hope for a country in which women are not violated everyday.

The beginning of the project

“The project happened organically,” Morayef says, “I found it impossible to post images without context. I did it once and ended up having to explain it, it became an article. It wasn’t originally a project but a personal hobby of mine. I started taking photographs every day in April, May 2011, in the neighbourhood I lived in, where there was a faculty of fine arts.”

This was Zamalek, “where the art students were, so it made sense this should be the hunting ground. There was always new graffiti popping up and disappearing. I wasn’t aware of other people doing it, other citizen journalists. I thought, ‘ok, I’m the only one doing this. It was for my personal archive, I put it on Facebook and a friend said ‘can I share your album’. I said ‘I’ll put it on a blog and you can share it with your friends.’”

“Then I noticed graffiti appearing in different neighbourhoods. With every post it went from being fun to being an obssession. At some point it felt like a responsibility, but not in a negative sense. I started getting feedback from street artists. I would start to credit the photographs to the separate artists, the artists would start to contact me because they recognised I enjoyed what I was doing, that there was no ulterior motive to my job.”

“What was really great about the process was social media. These artists were uploading or tweeting. By following the top Twitter accounts I would find out about work I hadn’t heard of. All the artists have Twitter accounts, Facebook, so it was easy to access them without invading their privacy.”

Keizer, Fear Me, Government! Copyright suzeeinthecity.wordpress.com

“It reached the point where I could recognise the street, the aesthetic of the artist and figure it out. Ganzeer [who she interviews here] created this interactive Google map, this blog, where he enabled artists to upload images, and their location, so people like me could upload and tag them to the artist. But the artists I follow and I am aware of, I think they are the tip of the iceberg. They are twenty percent of the graffiti crowd.”

“You have activists who use graffiti, artists who use graffiti for a certain phase then stop because it became too trendy, artists who join because it is trendy … it’s hard to keep track … artists who sign their work, others who have no interest. These people, some of them I would only come across because I would drive by or walk by. In one or two cases they would reach out and say this does belong to me but I don’t want anyone to know.”

Sad Panda

“I was included in this crowd, giving me access to their personal lives and their information. Someone like Sad Panda, who has created this anonymous persona for the media so no one knows his real name. I wrote a blog about when he welcomed me to his house. He introduced himself as a friend of the artist. So I walk in and I have no idea who this kid is, cutting up a stencil of a panda, then meeting his mum, watching him as he works, that was a privilege.”

Ganzeer’s tank versus bike (with Sad Panda in melancholy pursuit), under the October 6th Bridge. Copyright suzeeinthecity.wordpress.com.

The origins of graffiti

“The general view is that it [graffiti] started with the revolution. I completely disagree with this. I’ve seen graffiti for as long as I remember liking it. Graffiti on school walls, on mosque walls, whether it’s patriotic or, like, I love my school. There’s an argument that the Muslim Brotherhood started using graffiti, usually in the impoverished neighbourhoods. There’s an argument that it started in Alexandria, and many of the artists who are known as the pioneers of graffiti, were working there as early as 2003/4.”

“One of the images I took [of a fresh work of graffiti next to an older piece] when I posted it on Twitter someone I knew messaged me and said ‘I took a photo of the graffiti next to it in 2005!’ So there’s been a change in attention, attention and participation. And a sudden focus on the international media.”

“It started from an urgent need [during the uprisings] we had no internet, no phone-line. We were cut off from the media, there was no one there … As the intention increased, there was the glamorisation of people in the revolution, especiall the youthful ones, many artists felt the need to participate. And there was suddenly an audience, for something which [before] would have been received negatively.”

The gender of graffiti artists

“The gender is still predominantly male. I have noticed – in the collective, the Mona Lisa Brigade, who are using graffiti for social initiatives – they have thirty percent members who are female. Apart from the female artists I mentioned on my blog there are perhaps a handful more.”

The Mickey Mouse encounter (read about the episode here)

Keizer, Mickey Mouse. Copyright suzeeinthecity.wordpress.com.

“Two years on I have a different perspective on it. It is a good example in Egypt [of the reaction to graffiti], when you are dealing with forty percent of the population being illiterate. It’s an environment to create art that would explain [itself] or be easily interpreted. The man’s conversation was a good example of – and I’m generalising – how we prefer to be told what it is rather than figuring it out.”

“We’ve lived under a dictatorship for so long, and it’s not only Mubarak, but Sadat and Nasser. We haven’t had a free space to come up with our own ideas. We are used to voting yes to everthing, so with every singly referendum people have voted yes. Because we just don’t understand saying no to our leaders.”

“When street artists make work which says no to military leaders, these are the works which are responded to most negatively. It was really interesting, you would have people getting really vocal: ‘you can criticise our leaders but the army is a red line.’ We couldn’t handle seeing our leaders, our heroes, our pharaos, criticised.

“That particular artist [Keizer – who she interviews here] was making graffiti which was really Western-influenced. I personally felt – and what I saw – was a certain confusion behind the messages. I think he received some flak from his peers. [The man on the street] would not recognise why George Bush is holding Mickey Mouse by the paw.”

“When you are dealing with traumatic events there is so much to work with. Why would you mystify the man on the street? The artist has since said that he is using Western graffiti to attack the elites, and that’s his theory. But he has since moved to making graffiti with Arabic language and Egyptian symbols. I have noticed a shift.”

Violence against women

“One artist [Zeft] made a stencil of Nefertiti with a gas mask. He distributed it via social media and said you can reuse this. It appeared on the Facebook page of Op Anti-Sexual Harassment, and you can see it in photographs of protests a few weeks back. This image appeared in Washington, Berlin and Gaza.”

Zeft, Nefertiti mask. Copyright Ahmed Hayman.

“This was an example of one artist showing solidarity with women’s rights and rape. It became a symbol for social awareness campaigns. That’s a great success, but you are still dealing with a small segment of society. These artists, most of them are liberals, most of them are with the revolution. But the fact that women’s rights have been advocated by artists show that there has been a significant shift in awareness.”

The defacement of walls

“There was the Ganzeer tank versus bike grafiti, some of it was defaced. The artists are on the street, during the protest, sometimes the paint during the protest. I interviewed one artist during the protest: he was very upset, he said ‘this is the only thing I can do.’ So [working like this] is taking an artist from a sense of helplessness to a sense of responsibility.”

“This is the same thing the artists, Ammar Abo Bakr and Alaa Awad, who made the painting of the martyrs said. The guy and his friend made a mural on the AUC wall. They each spent two thousand Egyptian pounds, they said this is our way of paying them back. But it was so powerful and popular that alumni and members of the faculty circulated this petition asking the administration to stop the university from allowing government officials to paint over it. The artists came back and did a second paint.”

Painting of the Martyrs at AUC, Port Said. Copyright suzeeinthecity.wordpress.com.

“Then the government workers arrived. The baladiya – they are the bottom of the food chain, assigned to clean up – went down in the middle of the night. They actually had a line of soldiers protecting them as they cleaned off the graffiti. The reaction of the public was so heavy. You had street artists going on TV – who had previously avoided the media – who became very vocal in their criticism of the government. To the point that the prime minister had to release a statement.”

“I’m going to go ahead and say this was probably the most important moment in the history of graffiti. You had the prime minister, the second most important man in Egypt, having to apologise to a group of graffiti artists, who have been repeatedly criminalised.”

Soraya Morayef is currently pursuing a Master’s degree at Kings College London, as well as working with the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles on a series of videos documenting the graffiti scene in Cairo, Beirut, Libya and Palestine.

Egyptian Graffiti and Gender Politics: An Interview with Soraya Moreyef

Hanaa El Degham, mural on the wall of the Lycée Français, Cairo.

Mickey Mouse is pulling apart a bomb: inside is the torso of George W. Bush, and they’re both looking perfectly happy about the whole thing. Soraya Moreyef is taking a photo of the wall where these figures are painted, on a busy street in downtown Cairo, when a man walks up to her and asks her what the picture means.

‘I think that’s Mickey Mouse,’ I say helpfully.

‘Yes but what does it mean? And who is that man next to him?’

He’s bald with a graying walrus moustache, probably in his mid-forties, his full cheeks sweating as he fans at his pin-striped pink shirt.

‘I’m not quite sure,’ I say politely, wishing I could go back to my camera, but he appears adamant for an answer. ‘Maybe it’s a president? It could be George Bush.’

‘Yes but what is George Bush doing with Mickey Mouse? I like this picture, I walk past it every day, but I wish there’d be some writing explaining it so that I could understand.’

The man traps her against the wall, in conversation, telling her he was in Tahrir Square (a stone’s throw away from where they are standing) every day of the uprisings, “one of the shabab of the revolution…”. Eventually, after he has given her his number, he leaves, and she recommences her task, cataloguing the street art in Cairo, a city in which graffiti has flourished since 2011, but where the wall may have been white-washed the next morning.

Moreyef is a journalist and writer based in Cairo. Since June 2011 she has been blogging at suzeeinthecity.wordpress.com, where she posts images of street art, with captions and analysis. The same urgent questions — of graffiti and gender, intimidation and interpretation — resurfaced, as urgent as ever, in a recent post, ‘Women in Graffiti: A Tribute to the Women of Egypt’, on the participation of women in making graffiti on the walls of Egyptian streets.

Sit El Banat, stencil tribute to the women who were beaten, dragged and stamped on by military forces in December 2011.

The artists mentioned include Aya Tarek (“one of the pioneers of graffiti in Egypt”), Hend Kheera (“the first Egyptian graffiti artist to be profiled by Rolling Stone”), Bahia Shebab (an artist and art historian behind the project, A thousand times no), Mira Shihadeh, Laila Magued (more of her work here), the Nooneswa collective, and Hanna El Degham, whose work on the wall of the Lycee Moreyef describes as “one of the most astounding street artworks I have seen in Egypt.” The article also includes images of the tributes — by artists Alaa Awad, Keizer, Zeft and Amr Nazeer, X4SprayCans and Ammar Abo Bakr — to Egyptian women, their role in the protests, works made in outrage at the men who have harrassed and attacked them.

The world has been fascinated by the explosion of graffiti in Egypt, and the walls have become signifiers for revolutionary desires, and the street a place where art makes demands of its public, everyday. The precariousness of this art makes Moreyef’s catalogue of images necessary, and it has become the visual archive of an emancipatory politics, expressions of hope for a country in which women are not violated everyday.

The beginning of the project

“The project happened organically,” Moreyef says, “I found it impossible to post images without context. I did it once and ended up having to explain it, it became an article. It wasn’t originally a project but a personal hobby of mine. I started taking photographs every day in April, May 2011, in the neighbourhood I lived in, where there was a faculty of fine arts.”

This was Zamalek, “where the art students were, so it made sense this should be the hunting ground. There was always new graffiti popping up and disappearing. I wasn’t aware of other people doing it, other citizen journalists. I thought, ‘ok, I’m the only one doing this. It was for my personal archive, I put it on Facebook and a friend said ‘can I share your album’. I said ‘I’ll put it on a blog and you can share it with your friends.’”

“Then I noticed graffiti appearing in different neighbourhoods. With every post it went from being fun to being an obssession. At some point it felt like a responsibility, but not in a negative sense. I started getting feedback from street artists. I would start to credit the photographs to the separate artists, the artists would start to contact me because they recognised I enjoyed what I was doing, that there was no ulterior motive to my job.”

“What was really great about the process was social media. These artists were uploading or tweeting. By following the top Twitter accounts I would find out about work I hadn’t heard of. All the artists have Twitter accounts, Facebook, so it was easy to access them without invading their privacy.”

Keizer, Fear Me, Government!

“It reached the point where I could recognise the street, the aesthetic of the artist and figure it out. Ganzeer [who she interviews here] created this interactive Google map, this blog, where he enabled artists to upload images, and their location, so people like me could upload and tag them to the artist. But the artists I follow and I am aware of, I think they are the tip of the iceberg. They are twenty percent of the graffiti crowd.”

“You have activists who use graffiti, artists who use graffiti for a certain phase then stop because it became too trendy, artists who join because it is trendy … it’s hard to keep track … artists who sign their work, others who have no interest. These people, some of them I would only come across because I would drive by or walk by. In one or two cases they would reach out and say this does belong to me but I don’t want anyone to know.”

Sad Panda

“I was included in this crowd, giving me access to their personal lives and their information. Someone like Sad Panda, who has created this anonymous persona for the media so no one knows his real name. I wrote a blog about when he welcomed me to his house. He introduced himself as a friend of the artist. So I walk in and I have no idea who this kid is, cutting up a stencil of a panda, then meeting his mum, watching him as he works, that was a privilege.”

Ganzeer’s tank versus bike (with Sad Panda in melancholy pursuit), under the October 6th Bridge.

The origins of graffiti

“The general view is that it [graffiti] started with the revolution. I completely disagree with this. I’ve seen graffiti for as long as I remember liking it. Graffiti on school walls, on mosque walls, whether it’s patriotic or, like, I love my school. There’s an argument that the Muslim Brotherhood started using graffiti, usually in the impoverished neighbourhoods. There’s an argument that it started in Alexandria, and many of the artists who are known as the pioneers of graffiti, were working there as early as 2003/4.”

“One of the images I took [of a fresh work of graffiti next to an older piece] when I posted it on Twitter someone I knew messaged me and said ‘I took a photo of the graffiti next to it in 2005!’ So there’s been a change in attention, attention and participation. And a sudden focus on the international media.”

“It started from an urgent need [during the uprisings] we had no internet, no phone-line. We were cut off from the media, there was no one there … As the intention increased, there was the glamorisation of people in the revolution, especiall the youthful ones, many artists felt the need to participate. And there was suddenly an audience, for something which [before] would have been received negatively.”

The gender of graffiti artists

“The gender is still predominantly male. I have noticed – in the collective, the Mona Lisa Brigade, who are using graffiti for social initiatives – they have thirty percent members who are female. Apart from the female artists I mentioned on my blog there are perhaps a handful more.”

The Mickey Mouse encounter (read the whole episode here)

Keizer, Mickey Mouse.

“Two years on I have a different perspective on it. It is a good example in Egypt [of the reaction to graffiti], when you are dealing with forty percent of the population being illiterate. It’s an environment to create art that would explain [itself] or be easily interpreted. The man’s conversation was a good example of – and I’m generalising – how we prefer to be told what it is rather than figuring it out.”

“We’ve lived under a dictatorship for so long, and it’s not only Mubarak, but Sadat and Nasser. We haven’t had a free space to come up with our own ideas. We are used to voting yes to everthing, so with every singly referendum people have voted yes. Because we just don’t understand saying no to our leaders.”

“When street artists make work which says no to military leaders, these are the works which are responded to most negatively. It was really interesting, you would have people getting really vocal: ‘you can criticise our leaders but the army is a red line.’ We couldn’t handle seeing our leaders, our heroes, our pharaos, criticised.

“That particular artist [Keizer – who she interviews here] was making graffiti which was really Western-influenced. I personally felt – and what I saw – was a certain confusion behind the messages. I think he received some flak from his peers. [The man on the street] would not recognise why George Bush is holding Mickey Mouse by the paw.”

“When you are dealing with traumatic events there is so much to work with. Why would you mystify the man on the street? The artist has since said that he is using Western graffiti to attack the elites, and that’s his theory. But he has since moved to making graffiti with Arabic language and Egyptian symbols. I have noticed a shift.”

Violence against women

“One artist [Zeft] made a stencil of Nefertiti with a gas mask. He distributed it via social media and said you can reuse this. It appeared on the Facebook page of Op Anti-Sexual Harassment, and you can see it in photographs of protests a few weeks back. His image appeared in Washington, Berlin and Gaza.”

Zeft, Nefertiti mask. Copyright Ahmed Hayman.

“This was an example of one artist showing solidarity with women’s rights and rape. It became a symbol for social awareness campaigns. That’s a great success, but you are still dealing with a small segment of society. These artists, most of them are liberals, most of them are with the revolution. But the fact that women’s right have been advocated by artists show that there is a significant shift in awareness.”

The defacement of walls

“There was the Ganzeer tank versus bike grafiti, some of it was defaced. The artists are on the street, during the protest, sometimes the paint during the protest. I interviewed one artist during the protest: he was very upset, he said ‘this is the only thing I can do.’ So [working like this] is taking an artist from a sense of helplessness to a sense of responsibility.”

“This is the same thing the arists who made the painting of the martyrs said. The guy and his friend made a mural on the AUC wall. They each spent two thousand Egyptian pounds, they said this is our way of paying them back. But it was so powerful and popular that alumni and members of the faculty circulated this petition asking the administration to stop the university from allowing government officials to paint over it. The artists came back and did a second paint.”

Painting of the Martyrs at AUC, Port Said.

“Then the government workers arrived. The baladiya – they are the bottom of the food chain, assigned to clean up – went down in the middle of the night. They actually had a line of soldiers protecting them as they cleaned off the graffiti. The reaction of the public was so heavy. You had street artists going on TV – who had previously avoided the media – who became very vocal in their criticism of the government. To the point that the prime minister had to release a statement.”

“I’m going to go ahead and say this was probably the most important moment in the history of graffiti. You had the prime minister, the second most important man in Egypt, having to apologise to a group of graffiti artists, who have been repeatedly criminalised.”

Soraya Moreyef is currently pursuing a Master’s degree at Kings College London, as well as working with the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles on a series of videos documenting the graffiti scene in Cairo, Beirut, Libya and Palestine.

All images, unless credited otherwise, are copyright of suzeeinthecity.wordpress.com.

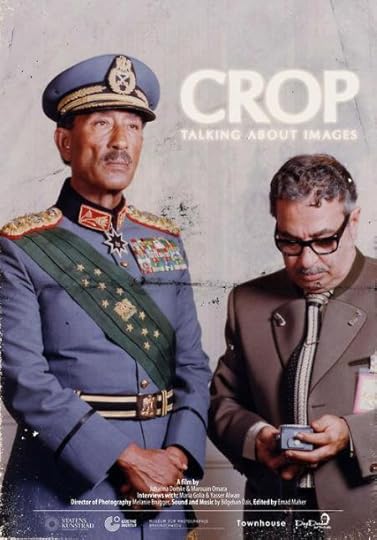

5 New Films to Watch, N°21

5 new documentaries this week. Crop: Talking About Images is a film directed by Marouan Omara and Johanna Domke. The film, quoting its website, “reflects upon the impact of images in the Egyptian Revolution and puts it in relation to the image politics of Egypt’s leaders. Instead of showing footage from the revolution, the film is shot entirely in the power domain of images — Egypt’s oldest and most influential state newspaper Al Ahram.” From the top-level executive office down to the smallest worker, the documentary follows a photo journalist who missed the revolution due to a hospital stay. Here’s an excerpt:

Même pas Mal (No Harm Done) is a film by Nadia El Fani and Alina Isabel Pérez that follows up on El Fani’s ‘Securalism – Inch’Allah’. The tone in ‘No Harm Done’, according to first viewers, has become darker, the director’s attitude noticeably more radical. “This may be due in part to her personal history: her cancer, the operation, chemotherapy on the one hand, paralleled by the unprecedented radical Islamist hate campaign against her film in Tunisia, which culminated in death threats against the director published on the social networks.” French-Tunisian Nadia El Fani received the best documentary film award at Fespaco this year. The film hasn’t been screened in Tunisia yet. Nor can the filmmaker return home.

The documentary Creation in Exile: Five Filmmakers in Conversation follows Newton Aduaka, John Akomfrah, Haile Gerima, Dani Kouyaté and Jean Odoutan: five African filmmakers in the diaspora (Paris, Washington, London, Uppsala), their everyday lives echoing sequences of their films. A film by Daniela Ricci:

Returning the Remains (“A Khoe Story 2″) is poet, writer and filmmaker Weaam Williams and Nafia Kocks’ 50 minute documentary about the history of the “unspoken of genocide” on South Africa’s Khoe/Khoi people. “The most challenging documentary film we’ve ever made,” Williams describes it in a recent interview. Here’s a first clip:

On a lighter note, Geoff Yaw’s King Me explores the world of competitive checkers play as seen through the eyes of South African Lubabalo Kondlo. In 2007, Kondlo, with the help of some sympathetic Americans, traveled to the U.S. to compete in the U.S. National Championship of Checkers in Las Vegas, Nevada. A relative unknown in the legitimate checkers world, Kondlo crushed the competition and earned the right to challenge 20+ year reigning World Champ, Ron ‘Suki’ King:

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers