Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 477

April 15, 2013

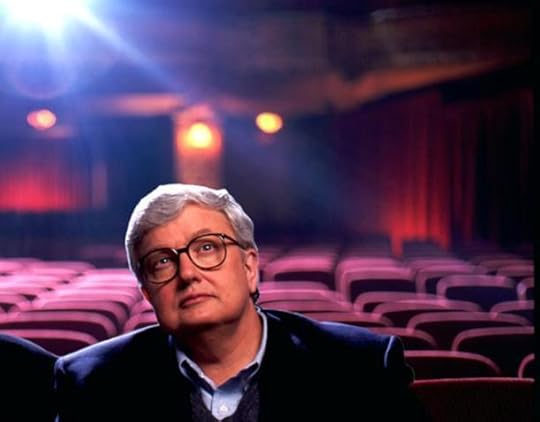

Roger Ebert was the business

When I first came to study in the US in the mid-1990s (at Northwestern University), I was quite enamored by American television. Of course that quickly wore off. But one of the programs that stuck with me, was a weekly film program, “Siskel and Ebert,” presented by the city’s two foremost film critics. You had to be around then to know how big and influential this program was in determining popular taste about new films; it was described last week as “one of the most powerful programs in television history.” Gene Siskel died of cancer in 1999, but Roger Ebert would soldier on and in the process established himself as probably the foremost film critic in the United States until his death last week. He also managed to adjust well to the rapid changes to the media industry in the last 2 decades or so, building one of the best “personal brands” in the process. There are other film critics who are intellectual–like Stuart Klawans at The Nation, Armond White (he was good once) and Stanley Kaufmann at The New Republic–but they lacked Ebert’s accessibility and heart. (Ebert, by the way, had an acute sense of the racial political economy in US cinema, as Richard Prince blogged at The Root). Ebert, who traveled to Apartheid South Africa as a young man, also reviewed a lot of African films.

Yes, he did not always get it right. For example, in a review of “District 9,” he said a large number of South Africans spoke Bantu and said nothing of the film’s portrayal of Nigerians. He also loved “Out of Africa”, as well as “Invictus.” But we’ll forgive him those. So here, in honor of Ebert, are excerpts from some of his reviews of African films or films with African themes (with a hyperlink to the original).

In 1967 on “Africa Addio,” a terrible Italian film composed of staged scenes of African brutality and incompetence:

“Africa Addio” is a brutal, dishonest, racist film. It slanders a continent and at the same time diminishes the human spirit. And it does so to entertain us … interior evidence in the film itself suggests that many of the scenes are phony. One dubious scene shows white Boers purportedly leaving Kenya in cattle-drawn wagons for the long trek back to the Cape. “A freedom march in reverse,” the narrator explains. “These Boers settled Kenya generations ago, but have been driven from their own country.” In fact, cattle-drawn wagons are no longer in general use in Africa, as Jacopetti and Prosperi undoubtedly knew. Real Boers (there are a few among the mostly British white population in Kenya) would probably call up a moving van for their furniture and then fly down to the Cape.

Ebert had first encountered the films of Ousmane Sembene in 1969 and was not impressed by Sembene’s early offerings (“Borom Sarrett” and “Black Girl”). Later, however, he would say about another Sembene film, “Guelwaar,” in 1994:

Moviegoers have little curiosity. Most of them will never have seen a film about Africans, by Africans, in modern Africa, shot on location. They see no need to start now (and this indifference extends, of course, to African-Americans). Movies can show us worlds and societies we will never otherwise glimpse, but most of the time we prefer to watch slick fictions with lots of laughs and action … (I)t is a joy to listen to the dialogue, in which intelligent people seriously discuss important matters; not one Hollywood film in a dozen allows its characters to seem so in control of what they think and say … (Sembene) reminds me that movies can be an instrument of understanding, and need not always pander to what is cheapest and most superficial.

Later, writing in 2007, on Sembene’s last film “Moolade,” a drama about female genital mutilation:

“Moolaade” is the kind of film that can only be made by a director whose heart is in harmony with his mind. It is a film of politics and anger, and also a film of beauty, humor, and a deep affection for human nature. Usually films about controversial issues are tilted too far toward rage or tear-jerking. Ousmane Sembene, who made this film when he was 81, must have lived enough, suffered enough and laughed enough to find the wisdom of age. I remember him sitting in the little lobby of the Hotel Splendid in Cannes, puffing contentedly on a Sherlock Holmes pipe that was rather a contrast with his bright, flowing Senegalese garb … Sembene’s work so often dealt with his society from the inside, with sympathy, insight, and the sly wit of a Bernard Shaw. He made political films that didn’t seem political, and comedies that were very serious. His regret was that many of his films, including “Moolaade,” were not welcome in Africa. He won awards at Venice, Karlovy Vary and many other important festivals; “Moolaade” won first place in the Un Certain Regard section at Cannes. But … the film has played nowhere in Africa except Morocco. The message is not heard where it is needed.

In 1987, while he encouraged people to see “Cry Freedom,” Richard Attenborough’s film about the relationship between the South African activist Steve Biko and the white newspaper editor Donald Woods, Ebert opened his review of the film thus:

“Cry Freedom” begins with the story of a friendship between a white liberal South African editor and an idealistic young black leader who later dies at the hands of the South African police. But the black leader is dead and buried by the movie’s halfway point, and the rest of the story centers on the editor’s desire to escape South Africa and publish a book. You know there is something wrong with the premise of this movie when you see that the actress who plays the editor’s wife is billed above the actor who plays the black leader. This movie promises to be an honest account of the turmoil in South Africa but turns into a routine cliff-hanger about the editor’s flight across the border. It’s sort of a liberal yuppie version of that Disney movie where the brave East German family builds a hot-air balloon and floats to freedom. The problem with this movie is similar to the dilemma in South Africa: Whites occupy the foreground and establish the terms of the discussion, while the 80 percent non-white majority remains a shadowy, half-seen presence in the background.

On “Mugabe and the White African” (reviewed by Ebert in 2010), a film about Mike Campbell, a white farmer, suing the Zimbabwean government over his expropriated farm:

… It seems to me that Campbell has a good case here–good enough, anyway, to convince the judges on the African court. One could understand the government buying his farm at a fair price under eminent domain and installing an African staff to manage it. Mugabe pays pitiful sums and his political cronies, not interested in farming, loot their new properties and deprive the resident laborers of their livelihood. Zimbabwe, which was one of the most prosperous lands in Africa, today has 80 percent unemployment and widespread disease and starvation. That being said, “Mugabe and the White African” could certainly have looked more deeply. The filmmakers travel to Kent in England to speak with the family of Campbell’s son-in-law, but never have any meaningful conversations with the African workers on Campbell’s farm. They support him, fight for him, are beaten by Mugabe’s thugs for their efforts. What do they think? Possibly their understanding of the situation is less theoretical than ours, and they don’t see how they can feed their families without stable employment.

Btw, the film was panned by one of our bloggers.

On “A Good Man in Africa,” a 1994 film revolving around a British diplomat set in a fictional African country and starring Sean Connery and Louis Gossett Jnr:

This plot, and the attitudes that underlie it, remind me of the patronizing tone of novels set in Africa 50 years ago, about colorful colonials and backward natives. The movie is not overtly racist (although the movie’s press book says Dr. Murray “may be the only good man in Africa,” which is a statement that grows more curious the more you think about it). But there is an unpleasant undertone.

And, finally, here is Ebert on “The Interpreter,” a thriller starring Sean Penn and Nicole Kidman set in another fictitious African country, probably Zimbabwe (Kidman plays an interpreter at the UN originally from that fictitious state):

I don’t want to get Politically Correct, I know there are many white Africans, and I admire Kidman’s performance. But I couldn’t help wondering why her character had to be white. I imagined someone like Angela Bassett in the role, and wondered how that would have played. If you see the movie, run that through your mind.

Rapping Against Impunity

Senegal’s rapper-activists recently collaborated on a new single in support of Amnesty International’s campaign against impunity in the country. The human rights advocacy organization launched the campaign to draw attention to the fact that there has been no justice for those who died during the 12-year regime of former President Abdoulaye Wade especially during the period just before the 2012 presidential elections. The campaign puts public pressure on President Macky Sall and calls for follow-though on criminal investigations in order to get justice for victims of violence and torture.

“100 Coupables: Impunité! Nous Avons besoin de Justice” (100 Guilty: Impunity! We Need Justice) is the brainchild of rapper/producer Simon of 99 Records. The single featuring Simon (Bisbiclan), Drygun (Yatfu), Beydi (Bideew bu Bess), Djiby (Dabrains), Thiat (Keur gui), Keyti and Books (Sen Kumpë) aims to bring the issue of impunity to the public’s attention. When Simon called the collective of rappers were more than willing to head into the studio in support of human rights. In fact, several of the rappers were either arrested themselves or victims of police brutality because of their work with the now famous Y’en a Marre movement—a social movement founded by rappers and journalists that gained mass popularity after president Wade attempted a power grab by changing the constitution and running for a third term in office. The song is a call for justice, respect for human rights and memorializing of the many victims of violence with rapping in Wolof set to a Hip-Hop beat.

If the social media response is any indication, Amnesty International was wise in its decision to collaborate with the rappers because the music video has been shared widely on multiple social networking outlets while official Amnesty International reports remain the reading of a select audience. Once again, Senegalese rappers continue to impress with their ability to take the message directly to the people.

Watch it:

* Janette Yarwood is a cultural anthropologist focusing on popular protests, youth movements and civil society across sub-Saharan Africa.

Apartheid in Manhattan: The International Center for Photography’s “Rise and Fall of Apartheid”

The International Center for Photography (ICP) is located in the heart of Manhattan, at the corner of West 43rd Street and the Avenue of the Americas. Nearby, Times Square’s mirages—brilliant expanses of neon fantasies, some spanning the length of several stories and the breadth of entire city blocks—summon passers-by with images of athletes, models, slick tans and racy footwear. There are some visible traces of “Africa”: West African men sell pashmina scarves, woollen hats, and gloves in street corner stalls, and Disney’s “The Lion King” rules Broadway—now in its fifteenth year running, the show has a stretch of window displays dedicated to re-instituting Africa as a place of masks, skins, and noble, half-human animals.

The International Center for Photography (ICP) is located in the heart of Manhattan, at the corner of West 43rd Street and the Avenue of the Americas. Nearby, Times Square’s mirages—brilliant expanses of neon fantasies, some spanning the length of several stories and the breadth of entire city blocks—summon passers-by with images of athletes, models, slick tans and racy footwear. There are some visible traces of “Africa”: West African men sell pashmina scarves, woollen hats, and gloves in street corner stalls, and Disney’s “The Lion King” rules Broadway—now in its fifteenth year running, the show has a stretch of window displays dedicated to re-instituting Africa as a place of masks, skins, and noble, half-human animals.

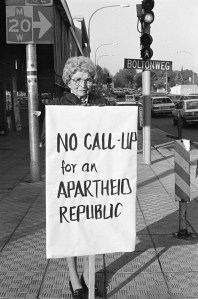

A yellow banner with black lettering—stretching across the length of the ICP’s ground floor windows—announces the current exhibition, “Rise and Fall of Apartheid.” By the front entrance, there’s a massive poster of a familiar image: a young Nelson Mandela, dapper in a double-breasted suit, a kerchief folded neatly in his pocket, and a parting combing a straight arrow through his hair. It’s late afternoon, and people rush by to the Bryant Park subway entrance on the corner, stopping to look only when they see me taking photographs. On the adjacent windows, posters of protestors displaying placards: a crowd of black women and one chubby, white schoolboy in shorts and shoes stand together, holding signs printed with the legend, “We Stand by Our Leaders.” Another placard declares, “Citibank, You Finance Apartheid.” And a man holding a homemade poster pleads for his love: “My Wife Emma Held 55 Days. Release All Detainees”. The number “55” is enclosed within a black box, drawing attention to his waiting, and her capture. I stood before this image, meditating on that pictograph. Though he must have been engulfed by a fear beyond my experience, this photograph conveyed something of it to me: quiet and constant, resonating across the ocean of unknowability that stands between the viewer and the act of regarding the pain of others.

A yellow banner with black lettering—stretching across the length of the ICP’s ground floor windows—announces the current exhibition, “Rise and Fall of Apartheid.” By the front entrance, there’s a massive poster of a familiar image: a young Nelson Mandela, dapper in a double-breasted suit, a kerchief folded neatly in his pocket, and a parting combing a straight arrow through his hair. It’s late afternoon, and people rush by to the Bryant Park subway entrance on the corner, stopping to look only when they see me taking photographs. On the adjacent windows, posters of protestors displaying placards: a crowd of black women and one chubby, white schoolboy in shorts and shoes stand together, holding signs printed with the legend, “We Stand by Our Leaders.” Another placard declares, “Citibank, You Finance Apartheid.” And a man holding a homemade poster pleads for his love: “My Wife Emma Held 55 Days. Release All Detainees”. The number “55” is enclosed within a black box, drawing attention to his waiting, and her capture. I stood before this image, meditating on that pictograph. Though he must have been engulfed by a fear beyond my experience, this photograph conveyed something of it to me: quiet and constant, resonating across the ocean of unknowability that stands between the viewer and the act of regarding the pain of others.

Star curator Okwui Enwezor’s intent for this exhibition—to ensure that the typical ways in which Africans are portrayed as hapless victims are not rehashed here at the ICP—is clear. Instead, we see the ways in which South Africans were powerfully engaged as “agents in their own emancipation.” Enwezor states, in a press release, “What I was principally interested in is the way in which apartheid gave us an image of a political doctrine that transformed from a juridical instrument into a normative reality.” That normative reality is what the show’s subtitle refers to as “the bureaucracy of everyday life.” But does this exhibit show the mundane and the ordinary? My childhood memories of South Africa in the 1980s, on a visit to Johannesburg with my family, are not of stoic, morally upstanding white ladies holding protest placards, nor of unified black and white rows confronting menacing police. What I remember was that the shop ladies at Woolworth’s were surprised that we—an ‘Indian’ family come down from Zambia on what was, essentially, a shopping trip—were present in the heart of Johannesburg, and that we had money to buy dresses there.

***

The ICP’s exhibition comprises of “nearly 500 photographs, films, books, magazines, newspapers, and assorted archival documents and covers more than 60 years of powerful photographic and visual production that forms part of the historical record of South Africa,” and includes nearly seventy photographers’ work: some are well known worldwide, like David Goldblatt, Peter Magubane, Alf Khumalo, and Gideon Mendel; and others who are virtually unknown outside of photography circles, even within South Africa. The long and complicated story of what happened between 1948 and 1990 is told chronologically, through a multitude of images. Using banner-sized panels of texts—denoting the different decades in apartheid history, as well as smaller panels of text explaining philosophical and political shifts—Enwezor projects a particular perspective that helps direct the visitor.

What does South Africa mean to Manhattan? Here, in Midtown, is it possible to communicate the mundane absurdities of “[o]ne of the most repressive and detested political systems ever devised”? Can photography translate apartheid, for this audience—one whose bus tickets declare, on the back, that seating on public transport here “is without regard to race, creed, color or national origin”? Many Americans 40 and older remember taking part in disinvestment rallies during their heady college years, camping out on their picturesque university lawns to protest university endowments with portfolios that included corporations that continued to do business in South Africa. They may remember an older show of photo essays at the ICP, back in the summer of 1986: “South Africa: The Cordoned Heart” gave “a multiracial group of twenty South African photographers” (including several included in the current exhibition: Omar Badsha, Rashid Lombard, Jeeva Rajgopal) a chance to show what life was like, behind the spectacular news stories. It was the first time that most Americans had seen the grueling violence of everyday poverty juxtaposed with the excesses handed to a handful of privileged under apartheid.

What does South Africa mean to Manhattan? Here, in Midtown, is it possible to communicate the mundane absurdities of “[o]ne of the most repressive and detested political systems ever devised”? Can photography translate apartheid, for this audience—one whose bus tickets declare, on the back, that seating on public transport here “is without regard to race, creed, color or national origin”? Many Americans 40 and older remember taking part in disinvestment rallies during their heady college years, camping out on their picturesque university lawns to protest university endowments with portfolios that included corporations that continued to do business in South Africa. They may remember an older show of photo essays at the ICP, back in the summer of 1986: “South Africa: The Cordoned Heart” gave “a multiracial group of twenty South African photographers” (including several included in the current exhibition: Omar Badsha, Rashid Lombard, Jeeva Rajgopal) a chance to show what life was like, behind the spectacular news stories. It was the first time that most Americans had seen the grueling violence of everyday poverty juxtaposed with the excesses handed to a handful of privileged under apartheid.

When I spoke to some of the young college students visiting the ICP that afternoon, it seems that there’s less of a connection for them. They have a place in their minds for Mandela as a global figure whose position in history resonates with that of Martin Luther King or Mahatma Gandhi. But far more millennials have no reference points to anchor them to events that took place in a far-away country at the southern tip of Africa: here, Africa is Lion King.

After visiting the ICP’s exhibition, I wonder if American visitors like the students to whom I spoke will regard those decades as one massive peaceful protest, during which white and black joined hands, came up with clever slogans, made posters in the backrooms of homes, and bravely faced police barricades together? Will framing the experience of apartheid as one massive co-involvement in organised protest create a rosier picture than is true? Without contextualising the system of apartheid as a continuation of segregationist colonial policies instituted by the British as well as the Dutch well before 1948—without knowledge of the myriad laws that helped create race-based segregation long before the National Party came into power, as well as an understanding about how the effects of those laws are fortified by current neo-liberal policies—I suspect that many visitors may view apartheid as something that began in 1948, and ended just as abruptly as it started in 1994.

After visiting the ICP’s exhibition, I wonder if American visitors like the students to whom I spoke will regard those decades as one massive peaceful protest, during which white and black joined hands, came up with clever slogans, made posters in the backrooms of homes, and bravely faced police barricades together? Will framing the experience of apartheid as one massive co-involvement in organised protest create a rosier picture than is true? Without contextualising the system of apartheid as a continuation of segregationist colonial policies instituted by the British as well as the Dutch well before 1948—without knowledge of the myriad laws that helped create race-based segregation long before the National Party came into power, as well as an understanding about how the effects of those laws are fortified by current neo-liberal policies—I suspect that many visitors may view apartheid as something that began in 1948, and ended just as abruptly as it started in 1994.

For these voyeurs, will apartheid be just another atrocity that happened in the Dark Continent, something so foreign to their present that they leave the ICP thanking God that it’s not something that has to do with “us”?

I worry, also, that the South African expatriates who visit this space are looking for redemption and erasure: when they see this sort of framing of apartheid, in which all are gathered to protest and decry the unjust policies, will it not re-configure the reality of the experience? Public protests happened rarely. For most of those five decades, people didn’t take to the streets, but planned political action in non-spectacular meetings and decades-long negotiations, endured quietly so they could eke out a living (as is evident in David Goldblatt’s images in The Transported of KwaNdebele), or stayed in their cushioned suburbs, braaied at pool parties, and enjoyed the policies that gave them an advantage (evident in Goldblatt’s In Boksburg).

Brian Wallis, the ICP’s Chief Curator, agrees that for Americans, their perspective is from a distance, though they may know more from having been engaged in the anti-apartheid movement as university students. For those who lived in South Africa, however, he believes “this brings back everything that they experienced; they really understand the complexities.” Wallis states that even for Enwezor (and Rory Bester, who assisted Enwezor), the exhibition was a challenge to organise, even though its focus is confined to a single country, and to a particular time period in African photography; the challenges arose because the exhibition covers some of the most “visible and contested set of issues surrounding apartheid, its institutions, and its dismantling. In some ways, those images from the fifty-year history of apartheid are the most visible for the general public, [forming] their image of African photography.”

Brian Wallis, the ICP’s Chief Curator, agrees that for Americans, their perspective is from a distance, though they may know more from having been engaged in the anti-apartheid movement as university students. For those who lived in South Africa, however, he believes “this brings back everything that they experienced; they really understand the complexities.” Wallis states that even for Enwezor (and Rory Bester, who assisted Enwezor), the exhibition was a challenge to organise, even though its focus is confined to a single country, and to a particular time period in African photography; the challenges arose because the exhibition covers some of the most “visible and contested set of issues surrounding apartheid, its institutions, and its dismantling. In some ways, those images from the fifty-year history of apartheid are the most visible for the general public, [forming] their image of African photography.”

***

The ICP, though not one of New York City’s mega-museums, is cleverly set up to maximise its space. Enwezor frames the exhibition via wall-mounted tablets imprinted with lengthy text to help contextualise the history. “Resistance to apartheid was in many ways a resistance to its laws. In the wake of these laws and the systems contrived for their enforcement—what may be called the bureaucratization of everyday life—a well organized, robust resistance movement, comprising South Africans of all racial and ethnic backgrounds and political beliefs, mobilized in what became an epic battle,” writes Enwezor on the introductory wall panel. However, he does not claim that this is a comprehensive history—rather, it is a “critical interrogation of [apartheid’s] symbols, signs, and representations.” Together, they help the viewer comprehend the “paradigmatic role played by social and documentary photography” in the struggle against apartheid.

Inside the lobby space, next to a seated museum guard, two television monitors play two separate loops of film: one is black and white, the other, colour. One features D.F. Malan’s victory speech in 1948, after his exclusively Afrikaner Nationalist Party defeated Jan Smuts’ United Party; the twin monitor features F. W. de Klerk’s speech, in February 1990, where he announced that all political parties would be unbanned, and that all political prisoners—including Nelson Mandela—would be released. I take a moment to listen to the two voices. One is celebratory, powerful, looking forward. The other is conciliatory, explanatory, asking his listeners to consider the denouement of their years in absolute power. But it is the billboard-sized image in front of the guard—behind a low wall hiding an escalator transporting visitors down to the basement-level—that catches the visitor’s eye: women standing side by side, holding vertical white signs printed with declamations and demands, forming a neat chain around a monumental city building.

Inside the lobby space, next to a seated museum guard, two television monitors play two separate loops of film: one is black and white, the other, colour. One features D.F. Malan’s victory speech in 1948, after his exclusively Afrikaner Nationalist Party defeated Jan Smuts’ United Party; the twin monitor features F. W. de Klerk’s speech, in February 1990, where he announced that all political parties would be unbanned, and that all political prisoners—including Nelson Mandela—would be released. I take a moment to listen to the two voices. One is celebratory, powerful, looking forward. The other is conciliatory, explanatory, asking his listeners to consider the denouement of their years in absolute power. But it is the billboard-sized image in front of the guard—behind a low wall hiding an escalator transporting visitors down to the basement-level—that catches the visitor’s eye: women standing side by side, holding vertical white signs printed with declamations and demands, forming a neat chain around a monumental city building.

The first photographs are images of the Afrikaner National Party’s surprise 1948 victory: Malan, his wife—her otherwise dowdy appearance downplayed by a luxurious length of fur swathed around her neck—attending formal functions, garden parties, meeting foreign dignitaries, signing bilateral agreements and opening factories. These photographs, which document the rituals of power that helped stage a de-historicised civility and create an illusion of normalcy, are flanked by sections of photographs depicting the Defiance Campaign and the Treason Trial: Mandela staging himself in beads and royal regalia while hiding out from the police during his period as the “Black Pimpernel”; Peter Magubane’s images of women demonstrating against pass laws; and an unidentified photographer’s image of Peter Magubane being arrested in December, 1956.

The section on “Drum Magazine and the Black Fifties” include Ranjith Kally’s images of performers at the Goodwill Lounge, Gopal Naransamy’s “Variety Concert at the Bantu Men’s Social Centre,” Bob Gosani’s photographs of a sexy pinup (Lynette Kolati of Western Township, Johannesburg) and countless other unidentified photographers’ fantasies of cover girls and jovial weekend parties. These images sit a few steps away from Billy Monk’s documentation of white rebels and revelry: young men and women, in various stages of undress, meeting in the “Catacombs” for drinking and trysts, defying Afrikaner strictures and moral codes. On the opposite wall: George Hallett’s iconic photographs of District Six are juxtaposed with Noel Watson’s images of police carrying out evictions of black people from newly designated “white” areas. There is also a small section of images devoted to Robert and Ethel Kennedy’s visit to South Africa. An enormous crowd gathered to welcome them; one banner reads, simply, “HI BOB.” Those two words communicate the sheer joy of having someone of the Kennedy’s stature understand the hardships of millions in country an ocean away, of being connected to him by the same exuberant desire to recognise common human dignity.

Standing there, enjoying a moment of revelry as I ogled that iconic image of Miriam Makeba (a reverie in her sewn-on-tight dress, straps slipping off to reveal bare shoulders), I see, in the periphery of my vision, a photograph of lined up, stripped naked black miners, arms raised to the air, awaiting medical inspection. These are Ernest Cole’s best-known photographs: people being fingerprinted for their passbooks, handcuffed men arrested for being in a “white area” illegally, and large signs denoting “white” taxi ranks, dry cleaners, toilets, entrances for “Non-Europeans and goods,” and a black woman scrubbing a “Whites only” stairway. Around the corner from Cole’s record of the pass laws’ dark story, “Images of Public Protest,” documenting the Sharpeville Massacre and the Soweto Uprising, contains some of the exhibition’s most striking images. They still have the power to make one weep, no matter how ever-present they are in South Africa.

Standing there, enjoying a moment of revelry as I ogled that iconic image of Miriam Makeba (a reverie in her sewn-on-tight dress, straps slipping off to reveal bare shoulders), I see, in the periphery of my vision, a photograph of lined up, stripped naked black miners, arms raised to the air, awaiting medical inspection. These are Ernest Cole’s best-known photographs: people being fingerprinted for their passbooks, handcuffed men arrested for being in a “white area” illegally, and large signs denoting “white” taxi ranks, dry cleaners, toilets, entrances for “Non-Europeans and goods,” and a black woman scrubbing a “Whites only” stairway. Around the corner from Cole’s record of the pass laws’ dark story, “Images of Public Protest,” documenting the Sharpeville Massacre and the Soweto Uprising, contains some of the exhibition’s most striking images. They still have the power to make one weep, no matter how ever-present they are in South Africa.

***

From here, an escalator leads to the lower exhibition spaces. It is in this labyrinth that the ICP provides the richest variety of photographers, some whose work I’d never come across, not even in South Africa. It is also here that I realise that some of the iconic images I associate only with one or two famous photographers contain themes that were simultaneously (or previously) photographed by their lesser-known contemporaries: Mofokeng’s images of mobile churches—“Opening Song,” “Laying of Hands,” “Exhortations” and “Overcome. Spiritual Ecstasy” resonate uncannily with Goldblatt’s near-comatose figures in The Transported of KwaNdebele: Mofokeng’s singing figures, eyes sealed shut, hands airborne, and mouths open in praise are almost transposable with Goldblatt’s twilight travellers, calling out to heaven to deliver them in their few hours of deep sleep.

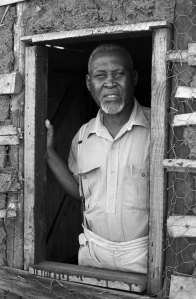

Chris Lechdowski’s images of “Katjong” and his “old time friends” in Harfield capture ordinary people, in spare surroundings, made iconic by the photographer’s ability to reframe them in light. Lechdowski’s work, and Omar Badsha’s “Pensioner,” “Migrant Worker,” and “Unemployed Worker” elevate the plasterer, the bricklayer, and the man who travelled far—only to face the absence of work—to that of apostles: these are stills capturing minor lives, memoirs of people who kept watch over each other, each witnessing the other’s day-to-day impossible hopes. In a brief interview, I ask Omar Badsha about photography’s connection with the work of memoir—how both are engaged in re-inscribing self, in re-visioning the manner in which one sees oneself, and, in the process, transforming how others see one, too. Because there was an intimate awareness that the photographer was not separated from her or his work, and that there was an imperative to tell one’s story as one experienced it—rather than as the apartheid state dictated it to be—Badsha and his contemporaries’ goals and challenges were inevitably linked with those that surround autobiography and memoir-writing. He emphasises, “How do you see or speak to yourself without first addressing yourself or identifying self, or without addressing the inherent racism inside all South Africans? In this way, photography speaks to biography. Our work as photographers helped reframe how we saw ourselves, especially in the 1980s.” Long before the Black Consciousness movement, Badsha and his contemporaries were aware of the intellectual and political work in which photographs and photographers participate. They were not just mechanics who shot and printed what stood before them, but cultural producers who understood the significance of photography in re-shaping the aesthetic, socio-political, and intellectual perceptions of their time. “Because we were not accepted or represented by major galleries, we realised that our audience is our own people. We showed it in our own communities, in halls; the exhibitions travelled from one community group to another. These efforts were about having agency; we were far from being victims.”

For some in South Africa, however, it seemed like nothing would change. John Liebenberg’s near-voyeuristic photographs of young, white men who went to make war on the border between Angola and South Africa—captured as they fired up braais, picnicked, and swam in the Cunene River within kilometres of killing fields—and Paul Weinberg’s photographs of then-president P.W. Botha and his wife visiting Soweto’s town council in 1988, leaving after they were ceremonially granted “freedom of the township” by the mayor of Soweto: all these images, presented in winding passages of exhibition space, make it seem as though life adjusted to apartheid, and that people just carried on. But Cedric Nunn’s image of a Valentine’s Day Ball (1986), juxtaposed with an image of a mother mourning the death of her son—a supporter of the UDF, in what came to be known as the “Natal War” (1987)—gives one an idea of the schizophrenic experience of the 1980s in South Africa.

For some in South Africa, however, it seemed like nothing would change. John Liebenberg’s near-voyeuristic photographs of young, white men who went to make war on the border between Angola and South Africa—captured as they fired up braais, picnicked, and swam in the Cunene River within kilometres of killing fields—and Paul Weinberg’s photographs of then-president P.W. Botha and his wife visiting Soweto’s town council in 1988, leaving after they were ceremonially granted “freedom of the township” by the mayor of Soweto: all these images, presented in winding passages of exhibition space, make it seem as though life adjusted to apartheid, and that people just carried on. But Cedric Nunn’s image of a Valentine’s Day Ball (1986), juxtaposed with an image of a mother mourning the death of her son—a supporter of the UDF, in what came to be known as the “Natal War” (1987)—gives one an idea of the schizophrenic experience of the 1980s in South Africa.

But in the end, no one had the luxury of standing still: although Gisèle Wulfsohn’s “Domestic Worker” (1986) shows a be-aproned black maid walking a dog on Lookout Beach, Plettenberg Bay, with her ‘madam’ walking a few steps ahead, Rashid Lombard’s photograph captures the joyful energy of a Defiance Campaign group taking over a “whites only” beach in Blauberg Strand in 1989. Lombard’s is one of the few colour photographs in the exhibition, and remarkable for it: the sky is that impossible Cape Town summer blue, trousers are rolled up against the sand and surf, skin is glowing with the pleasure of that day. Arm in arm, a group intended only to walk madam’s dog on this exclusive piece of beachfront strides purposefully up the strand.

***

One almost feels suffocated in the exhibition spaces; but simultaneously, I realise that without feeling overwhelmed, the “cumulative effect of what took place in South Africa could not be experienced otherwise.” These are photographs of life under siege: the thrill of an American politician’s visit, the daily indignities and flaring violence, and the escapism provided by drink, song, dancing, and sex. Together, they show us how ordinary life went on, despite the restrictions of apartheid laws, and how the massive bureaucracy infringed on these escape artists nonetheless, illustrated in the abandon and excesses with which each group partied as hard as possible, coming together so rarely and under such secrecy that it was hardly ever captured in photographs. In staging a photography exhibition covering some of the darkest times in human history, leading up to a revolution, and a democratic election, the ICP could have glorified and whitewashed. But these coiling rooms of photographs remind us that this was not an exhibition intended to tell simplified stories of uncontested victories, replete with easy villains and sanctified national heroes.

All images reproduced by kind permission of the International Center for Photography. This essay is cross-posted on the new online art magazine “Contemporary And” (C&), “a dynamic space for the reflection on and linking together of ideas, discourse and information on contemporary art practice from diverse African perspectives.” It first appeared in Art South Africa in March 2013. “Rise and Fall of Apartheid: Photography and the Bureaucracy of Everyday Life” now runs at Haus der Kunst (Munich, Germany) until May, 26.

April 14, 2013

Weekend Special, N°1000

1. African Dosseh Ayamam becomes the first man to walk on Mars.

2. Charismatic Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Adichie has a new novel which is about love, race and … “hair politics.” She is a natural hair fundamentalist of sorts. The media wants to talk to her about hair. It’s also a good strategy to promote the novel. Watch or read here, here and here. So there’s also a “hair debate” now, especially among Nigerian bloggers like YNaija and Linda Ikeji (the latter whose hundreds of commenters prefer weaves).

3. Anyway, since we’re talking about standards of beauty, Al Jazeera English went to Nigeria–where “more than 70 percent of Nigerian women admit they use such products”; the highest levels on the continent–to do a story on skin lighteners. Reporter Mohammed Adow: “In many parts of Africa, lighter skinned women are considered more beautiful” and considered more successful.” Musician Femi Kuti gets asked for his opinion. Don’t ask me why. At least the reporter did not go on about black being beautiful. Spoke too soon. Yes he did. Watch:

4. Still on Nigeria. Remember when Kim Kardasian 419′d some Nigerian entertainers and media elites in February? Now a fake Kim Kardasian tweet about that ill-fated visit has Nigerians all mad, a month later.

5. Nigeria’s relentless pop machine debuted the music videos for a ton of derivative pop in the last few weeks. These include Waje’s lover’s rock-reggae hybrid, former actress Tonto Dikeh’s sampling “Guantanamera” and Kefee’s gospel pop. Best of the bunch, however, is rapper Splash:

6. GQ has a long profile on Nigerian-American artist Kehinde Wiley; he of the enormous canvases of black and African men overlaid with patterns from fabrics Wiley finds in a market and imitating the natural style of “Old Masters” paintings. Wiley is traveling “over the next month in five different African countries—Morocco, Tunisia, Gabon, Congo, and Cameroon—in search of representative men.” He, or an assistant, is photographing hundreds of them, then he (or assistants) go paint the images in his studio in Beijing for a new show of 15 paintings–part of his “World Stage” series–planned for October in Paris. The GQ piece, by Wyatt Mason (a professor at Bard College) also includes some snippets of racism by Moroccans (e.g. in a restaurant, where Wiley wanted to play down the racism as not to create waves) and in the Democratic Republic of Congo “where shit got crazy” (Mason didn’t accompany Wiley and his group to Congo, but the story was relayed by Wiley):

There they were again, in a tiny village in the Congolese jungle, shooting there as they do. And the Congolese secret police swooped down, seized them and their things, took them to several black sites. And held them for days. “They thought that we were tampering with the democratic elections,” Wiley tells me later. “They thought we might be buying votes. It was our fault. We should have known better.” In the documentary about their travels, Wiley does not say that [one member of traveling party] was able to call his parents, that they may have known some people with the clout to get them out. I tell him it’s curious that these things don’t get mentioned. He says he doesn’t want to go into that stuff much because “it’s a negative way of talking about Africa” … eventually, a few days in, he and his entourage were released and told to leave the country, immediately.

Mason concludes that “negativity has no place in Wiley’s art, to date. Its message, a positive one, a repetitive one, is as tireless as its maker.”

Not everyone’s happy with all this:

“I don’t think that they’re terrible paintings,” art critic Ben Davis, a vocal Wiley detractor, told me, “but they don’t benefit from close scrutiny. I find them cartoonish and the painting itself flat. It seems very formulaic. If you think of really good portraiture, you get a sense of emotion, paintings that have a spark of individuality where something of the sitter is captured. Wiley’s formula smothers that. He’s releasing product lines. ‘Here I am releasing my Ethiopia line, my Israel line.’ He’s not producing a new critical image of black identity. He’s an art director selling a formula, a style, that can be translated into a lot of different mediums.”

But after all that, we also get to see how a Wiley painting gets made.

7. April 10th was the 20th anniversary of the murder of South African leader Chris Hani by a white, rightwing conspiracy, including a member of the Apartheid parliament (who is still sitting in prison for the murder). Hani is still one of my personal heroes. With struggles over memory now commonplace in South Africa and subject to , it’s worth recalling Hani’s impact. There’s still not a decent book about Hani out there. (I wanted to write about him, but that’s a story for another day.) For now, Abbey Lincoln and Max Roach’s “Freedom Day” suffices:

8. Emmanuel Eboue, now playing for Galatasaray in Turkey, scored a Messi-like goal (in the words of the venerable Elliot Ross) against Real Madrid in the quarterfinals of the UEFA Champions League this week. Unfortunately Eboue’s goal, and two others by Didier Drogba (of course) and Wesley Sneijder, were not enough to stop Madrid in its quest for a 10th European Cup. But we can enjoy the goal again, and this photograph of Drogba congratulating Eboue:

9. That investigate broadsheet National Enquirer and and conservative radio host Rush Limbaugh (stop here if you don’t need to take a shower afterwards) “report” that Chelsea Clinton will adopt an African baby. Here’s the Enquirer:

‘Chelsea has a heart of gold, and recently everything – from her parents’ health crises, to her and Marc’s inability to conceive and her family’s special devotion to the black community – came together in her mind,’ said the source.

10. Finally, American dancer Chris Brown learned one thing on his recent Ghanaian and Nigerian travels: how to Azonto (though he got the origins wrong and some YouTube commenters don’t think he gets the moves right):

Nice try. Now here’s some real Azonto.

* With this, I am bringing back “Weekend Special” for all those things we don’t have the time to blog about or say more than the required 140 characters on Twitter.

Weekend Special, No. 1000

1. African Dosseh Ayamam becomes the first man to walk on Mars.

2. Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Adichie has a new novel which is about hair politics. And the media wants to talk to her about is hair. It’s also a good strategy to promote the novel. Watch or read here, here and here. There also now a “hair debate,” especially among Nigerian bloggers like YNaija and Linda Ikeji (whose hundreds of commenters prefer weaves).

3. Anyway, since we’re talking about standards standards of beauty, Al Jazeera English went to Nigeria–where “more than 70 percent of Nigerian women admit they use such products;” the highest levels on the continent–to do a story on skin lighteners. Reporter Mohammed Adow: “In many parts of Africa, lighter skinned women are considered more beautiful” and considered more successful. Musician Femi Kuti is asked for his opinion. At least the reporter did not go on about black being beautiful. Yes he did. Watch:

4. Still on Nigeria. Remember when Kim Kardasian 419′d some Nigerian entertainers and media elites in February? Now a fake Kim Kardasian tweet about that ill-fated visit had Nigerians all mad.

5. Nigeria’s relentless pop machine debuted the music videos for a ton of derivative pop in the last few weeks. These include Waje‘s lover’s rock-reggae hybrid, former actress Tonto Dikeh’s sampling “Guantanamera” and Kefee‘s gospel pop. Best of the bunch, however, is rapper Splash:

6. GQ has a long profile on Nigerian-American artist Kehinde Wiley (he of the enormous canvases of black and African men overlaid with patterns from fabrics Wiley finds in a market and imitating the natural style of “Old Master” paintings) who is traveling “over the next month in five different African countries—Morocco, Tunisia, Gabon, Congo, and Cameroon—in search of representative men, hundreds he’ll photograph all over Africa,” who he’ll photograph, go paint in his studio in Beijing for a new show of 15 paintings–part of his “World Stage” series–in October in Paris. The piece, by Wyatt Mason (a professor at Bard College) also includes some snippet of racism by Moroccans (in a restaurant, which Wiley wanted to play down so not as to create waves) and in the Democratic Republic of Congo “where shit got crazy” (Mason didn’t accompany Wiley and his group to Congo, but the story was relayed by Wiley):

There they were again, in a tiny village in the Congolese jungle, shooting there as they do. And the Congolese secret police swooped down, seized them and their things, took them to several black sites. And held them for days. “They thought that we were tampering with the democratic elections,” Wiley tells me later. “They thought we might be buying votes. It was our fault. We should have known better.” In the documentary about their travels, Wiley does not say that Zack was able to call his parents, that they may have known some people with the clout to get them out. I tell him it’s curious that these things don’t get mentioned. He says he doesn’t want to go into that stuff much because “it’s a negative way of talking about Africa” … eventually, a few days in, he and his entourage were released and told to leave the country, immediately.

Mason concludes that Wiley “negativity has no place in Wiley’s art, to date. Its message, a positive one, a repetitive one, is as tireless as its maker.”

Not everyone’s happy with all this:

“I don’t think that they’re terrible paintings,” art critic Ben Davis, a vocal Wiley detractor, told me, “but they don’t benefit from close scrutiny. I find them cartoonish and the painting itself flat. It seems very formulaic. If you think of really good portraiture, you get a sense of emotion, paintings that have a spark of individuality where something of the sitter is captured. Wiley’s formula smothers that. He’s releasing product lines. ‘Here I am releasing my Ethiopia line, my Israel line.’ He’s not producing a new critical image of black identity. He’s an art director selling a formula, a style, that can be translated into a lot of different mediums.”

But after all that, we also get to see how a Wiley painting gets made.

7. April 10th was the 20th anniversary of the murder of South African leader Chris Hani by a white, rightwing conspiracy, including a member of the Apartheid parliament (who is still sitting in prison for the murder). Hani is still one of my personal heroes. With struggles over memory now commonplace in South Africa and subject to , it’s worth recalling Hani’s impact. There’s still not a decent book about Hani out there. (I wanted to write about him, but that’s a story for another day.) For now, Abbey Lincoln and Max Roach’s “Freedom Day” suffices:

8. Emmanuel Eboue, now playing for Galatasaray in Turkey, scored a Messi-like goal against Real Madrid in the quarterfinals of the UEFA Champions League this week. Unfortunetaly Eboue’s goal, and two others by Didier Drogba (of course) and Wesley Snijder, were not enough to stop Madrid in its quest for a 10th European Cup. But we can enjoy the goal again and this photograph of Drogba congratulating Eboue.

9. That investigate broadsheet National Enquirer and and conservative radio host Rush Limbaugh (stop here if you don’t need to take a shower afterwards) “report” that Chelsea Clinton will adopt an African baby. Here’s the Enquirer:

‘Chelsea has a heart of gold, and recently everything – from her parents’ health crises, to her and Marc’s inability to conceive and her family’s special devotion to the black community – came together in her mind,’ said the source.

10. Finally, American dancer Chris Brown learned one thing on his recent Ghanaian and Nigerian travels: how to Azonto (though he got the origins wrong and some Youtube commenters don’t think he gets the moves right) :

Nice try. Now here‘s some Azonto.

* With this, I am bringing back Weekend Special for all those things we don’t have the time to blog about or say more than the required 140 characters on Twitter.

April 12, 2013

Weekend Music Break

Here’s ten new videos to get your weekend started. Some pop, some rap, some indie, but first, some dance (what’s in a name). Above’s Black Coffee latest, feat. Nomsa Mazwai and Black Motion on “Traveller”. Next: Owiny Sigoma Band (that’s Joseph Nyamungo, Charles Okoko and friends in London) put out this festival-vibes video for “Nyiduonge Drums” (which, oddly, is not on the record they recently released):

Congolese “Hustler” (his word) Fally Ipupa is “Back”; these loosely choreographed videos never cease to amaze:

Nigerian trio Weray Ent’s second single “Masquerade” features Ghanaian group Vibe Squad. Important disclaimer in the opening lines; what follows is a feast of styles:

Dochi and Ali Kiba bring the weekly Bongo sounds on “Imani”:

With the arrival of their first EP, Bells Atlas released a video for “Lovin You Down” — recorded while the band was on tour recently (and spent time in Miami during the International art event Art Basel):

Rokia Traoré could have come up with a different title for her new record, but the songs that are on there are magnificent. Quite politically engaged lyrics too, like much of what’s coming out of Mali over the past year. Production: John Parish. This is a first single, “Mélancolie”, and video:

UK youth broadcaster SB.TV put up a live video of UK artist (and AIAC household name) Akala, performing his track “Lose Myself”, a collaboration with Josh Osho — a new web series to watch:

Playing in London tonight (and pretty much everywhere else in Europe later this month; they sent us a reminder earlier this week) are Cuban combo Alexander Abreu y Havana d’Primera. Don’t miss it if you like your salsa:

And, finally, your moment of zen: this video for four-piece London band Woman’s Hour’s “To the End”, directed by South Africans Oliver Chanarin and Laurence Hamburger. Trampolinists are Siphiwe Mosoang and Xolani Nxumalo:

Woman Hour’s debut EP’s soon to be released on Parlour Records. Now watch that video again.

Looking Back on FESPACO 2013

The 23rd edition of the famed West African film festival FESPACO ran last month in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. We previewed it here. Since the festival, we asked two filmmakers—Newton Aduaka (who attended) and Haile Gerima (who stayed away)—and one film critic and academic, Mbye Cham (who served as president of the Official Jury for Long Feature Films at FESPACO in 2011), to give us their respective takes on the festival. First up is Professor Cham, who is chair of Howard University’s African Studies Department and who has published widely on themes related to African film.

The 23rd edition of the famed West African film festival FESPACO ran last month in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. We previewed it here. Since the festival, we asked two filmmakers—Newton Aduaka (who attended) and Haile Gerima (who stayed away)—and one film critic and academic, Mbye Cham (who served as president of the Official Jury for Long Feature Films at FESPACO in 2011), to give us their respective takes on the festival. First up is Professor Cham, who is chair of Howard University’s African Studies Department and who has published widely on themes related to African film.

How long have you been attending FESPACO? And what did you think of it this year?

How long have you been attending FESPACO? And what did you think of it this year?

The first time I went to FESPACO was in 1985 and that was through my colleague at Howard University, Haile Gerima, who was on the jury at the one prior to the 1985 edition, in 1983. He was very impressed with what he saw going there. He came and mobilized some of us to think about going to the following edition in 1985. That was the time when we got together and got the first delegation for the first edition of African American filmmakers to go to FESPACO. Along with that, there was a symposium also organized at the university of Ouagadougou that explored relationships and partnerships between African filmmakers and African-American filmmakers. A couple of projects came out of that particular encounter. It opened up FESPACO to the broader diaspora, and made it live up to its Pan-African dimensions. One of the important outcomes of that particular trip was the establishment of the Paul Robeson Prize.

Over the years, the festival has changed dramatically. This year, the festival was much, much better organized. Part of the whole thing about FESPACO is that, year after year, the same old problems kept cropping up. But this year, amazingly, I did not hear anybody complain. At least not to me. I didn’t overhear the usual complaints about people not getting hold of their badges, the program not being ready. There were a few cases where a couple of filmmakers were complaining about the conditions of the screenings of their films. But, on the whole I thought this year’s festival was much better organized. The selection was also a lot better, in terms of the quality, the diversity and the themes and subject matter were quite interesting.

Did you hear some complaints about the 35 mm rule (that is the festival organizers’ decision to only accept films shot on 35mm)?

That’s one of the perennial issues that FESPACO has had to deal with. It’s not just an issue with Nigerian films, but really with Anglophone films. Because for a long time, the Anglophones have felt marginalized. The festival is still pretty much Francophone heavy. And, there needs to be some type of balance. This year definitely was no exception at all. Even though in the main competition, there was a film by a Nigerian, Newton Aduaka. He’s a Nigerian but living in Paris. The sort of films that you see very popular today in West Africa, and perhaps globally, are the so-called Nollywood films. These are a market absence in selection at FESPACO. The one that would come nearest to that would be the Ethiopian film Nishan.

In 2011, I was the President of the Jury. One of the films that we had a lot of discussions about was the film Le Mec Ideal, by the director from Côte d’Ivoire, Owell Brown. It’s a film that departs from your normal, dominant discourse and one that came a little closer to the Nollywood narrative. It showed that it was time for FESPACO to open up. This film ended up receiving the bronze.

How do you think that politics plays into the festival, in the context of Thomas Sankara’s assassination and of Blaise Compaore, a kind of “life president,” who is blamed for his murder, as a major benefactor of the festivities?

The nature of African politics is that [laughing], as you know very well, that these “Presidents for life” are a part of the reality that unfortunately defines many political landscapes in Africa. Yes, Compaore has been there since 1987. And what are the prospects of him exiting peacefully? Well, again, it’s anybody’s guess. We don’t know. There are signs that he might be leaving soon. I don’t think he has anything to do really with the actual selection of the films. I’m sure that there’s an awareness of his likes and dislikes, but I don’t think those factor in at all in terms of the selections.

How do you feel about other African oriented festivals that are spreading in the US?

It helps. Any opportunity to showcase these films, which have a difficult time circulating in the normal circuits, helps. As our friend Clyde Taylor used to point out, the paradox is that you have more festivals in the US devoted to African cinema than to African-American cinema. “Why,” is another question. The festivals and similar events that take place in the US are in no way in competition with FESPACO. I think they reinforce and compliment each other.

And what about the rising number of festivals in North Africa?

Well, I don’t think they are (competing). FESPACO has institutionalized itself in the cultural film calendar in Africa to such an extent that you have all these other festivals going on but I don’t think people are quite at that point where they’re ready to throw FESPACO overboard. To me it is still the festival as far as African cinema is concerned. You have a lot of others that are happening in Southern Africa. In South Africa in particular, there’s the Durban Film Festival. You may have some festivals in East Africa. The Nigerians have their own. But, to date I don’t think any of them have dislodged FESPACO as the premier venue for African cinema. For the future, I don’t know. But for now… it hasn’t been the case yet.

South Africa has been a go-to country for some large-scale Hollywood productions. How do you feel that has played a role in South Africa’s efforts to grow its film industry?

Historically, if you look at the situation in South Africa as far as film is concerned, that historical domination by Hollywood is still there to a large extent. So that a lot of the films that have made it internationally outside of South Africa tend to be films that adopt Hollywood formulas. The few that are really in the same mold as the ones that you see in other parts of Africa are there, and have some merit, mostly by Black filmmakers. But those have rarely been given the recognition that they deserve outside of South Africa. South Africa is still operating under conceived conventions of what cinema is. One can trace the origins of that to the apartheid days and the dominance of Hollywood on the industry there.

***

Next up is Haile Gerima, the director of the epics “Teza” and “Sankofa” and the co-owner of Mypheduh Films.

Next up is Haile Gerima, the director of the epics “Teza” and “Sankofa” and the co-owner of Mypheduh Films.

Why have you decided not to attend FESPACO?

I don’t go to FESPACO because it’s become a circus without objectives. It’s like all other festivals, without the initiatives and objectives it was created under. Why not just go to a white festival? Why still be the “other” in that mess? The country shouldn’t even have the right to sponsor this type of festival. They assassinated a human being. There should be a Sankara/Compaore documentary to explore that.

***

Finally, here’s Newton Aduaka, the Paris-based director Newton who was the only Nigerian to attend this year’s festival with his film, One Man’s Show, starring Emil Abossolo-Mbo.

Finally, here’s Newton Aduaka, the Paris-based director Newton who was the only Nigerian to attend this year’s festival with his film, One Man’s Show, starring Emil Abossolo-Mbo.

How was it to attend this year’s festival?

As always, the run up to the festival was hectic. I had quite a bit of work on my hand completing the post-production of One Man’s Show with my co-producers, Centre Cinematographique Marocain, at their labs in Rabat, Morocco. They were very kind to jump in at the last moment to help in preparing the infamous 35mm print as the film was in competition. It was exciting being back in FESPACO again.

How did you feel about “Aujourd’hui” getting the Etalon D’or?

As you know, “Aujourd’hui” was co-produced by Granit Films, Paris; the production company owned by Alain Gomis, Valerie Osouf, Delphine Zingg and myself. We are very proud that the film won the Etalon D’or, and deservedly so for Alain. With ”Aujourd’hui” Alain explored a complex in-between space; between life and death, metaphysical and the real, home and away, the link between the here and hereafter, etc but in a very poetic and personal way. I am happy that Alain got the recognition he rightly deserves.

I’ve read reviews of FESPACO (here and here) that complain that not more Nigerian, or rather Anglophone, filmmakers could be involved in the competition because they did not shoot or print on 35 mm film. Do you think that rule should change? Or rather, do you think that the competition is fairly open?

I believe that that rule has been scrapped. From 2015, films in competition can now be shown on DCP (digital cinema packages) as well. This is a concession that goes some way towards addressing the long pressing issue of FESPACO embracing digital projection. African filmmakers are some of the least underfunded filmmakers in the world and shooting or printing film on 35mm is a very costly process which most of us cannot afford. It has become a trap that has in the past excluded certain films that should have been in competition; a loss to the festival and disappointment for the filmmaker. I must clarify here that though the old rules said that films must be shot in 35mm, some of the films in past competitions were shot in digital and then transferred to 35mm print. Though a cheaper route to a 35mm projection than shooting the entire film on 35mm or Super 16 for that matter, it no less set those filmmakers back near €30,000. The restriction no longer makes sense; hence I appreciate the new rule. If filmmakers can afford to shoot on film, great, but if not, then we can now be honest with the digital process and go digital all the way. I hope that this debate of medium, of celluloid/digital, can now be put to rest so that we can focus on the more important matter of discussing the craft of cinema, form and content, especially the latter.

5 New Films to Watch, N°23

British filmmaker Roy Agyemang’s documentary on Robert Mugabe, “Villain on Hero?”, intended to be a three-month mission but turned into a three-year mission. “Roy and his UK based Zimbabwean fixer, Garikayi, worked their way through the corridors of power, probing the cultural, economical and historical factors at the heart of the “Zimbabwean crisis”. In their quest to interview Mugabe, Roy and Garikayi were mistaken for the British Secret Service” (film notes). Trailer tells us they got the interview, but not how it ended. Next, Rêve Kakudji is a documentary film by Ibbe Daniëls and Koen Vidal about Congolese opera singer Serge Kakudji. Kakudji is introduced as “the first African to sing arias in the predominately white world of opera music” — is that so? “Bridging the gap between Europe and Africa”:

Operation Vula is a documentary by Naäma Palfrey about Conny Braam who, in the mid-eighties, in addition to her chairmanship of the anti-apartheid movement, is secretly in charge of more than 70 Dutch volunteers over the course of 5 years. Together with the ANC leadership, Conny and these volunteers pursue an operation to support and manage South African ANC exiles that are being disguised in Amsterdam to infiltrate South Africa with false identities to continue and intensify the underground resistance from within. A good additional read on this is Bart Luirink’s recent book Zwart Goud (“Black Gold”):

Director Kaizer Matsumunyane (born in Lesotho) explains the idea behind his upcoming documentary The Smiling Pirate (6 minutes into the video below): “In October 2013, Sony Pictures will release a Tom Hanks motion picture purporting to tell the story of the Maersk Alabama’s hijacking in 2009 by a band of Somali Pirates. This narrative is told from the vantage point of its captain, Richard Phillips, played by Tom Hanks. My documentary, however, tells the story and more but from the vantage point of the one surviving Pirate, a teenager named Abduwale Abdukhad Muse. With three other Somali teenagers, Muse took the ship’s captain Richard Phillips hostage. During the rescue by US Navy Seals, Muse’s three compatriots were killed but he survived to become the first person to be charged of piracy in the United States in more than a century. The documentary will tell the story of Muse growing up in Somalia, the girl he was working to marry, the recruitment into piracy at the age of 16, the piracy training he undertook, the three ships he hijacked, being captured and held hostage by the Al Qaeda linked Al Shabaab in Somalia, the hijacking of the American flagged ship, the trial in the U.S, experience of solitary confinement for more than a year, life in prison and his fight for a retrial.”

Penny Woolcock’s documentary One Mile Away is portrayed as a “riveting portrait of the complex, contentious reality of the streets, and the courage it takes to make a difference…it could well be this year’s most important British film” (Time Out). The film charts the attempts by two warring gangs in inner city Birmingham, the Burger Bar Boys (B21) and the Johnson Crew (B6), to bring peace to their neighbourhoods. Some background: here and here. The trailer:

And here’s a bonus: register your interest in seeing “One Mile Away”, and watch it: here. Or here (H/T Duma).

April 11, 2013

Madonna vs Joyce Banda: Celebrity Deathmatch (Philanthropy Edition)

We had been studiously avoiding coverage of Madonna’s latest trip to Malawi, but such is the deliciousness of the excoriating 11-point press release put out yesterday by Joyce Banda that we couldn’t resist wading in. These two had previous — Madonna’s people had scapegoated Banda’s sister over a botched school project — and the latest visit was something of a surprise as the singer was widely supposed to have been declared persona non grata. Last week Madonna sent Banda a weird overfamiliar hand-scrawled note which seemed to piss Banda off to the extent that she immediately leaked it. Finally, enraged by Madonna’s whining to the international press about having to check in on departure at the airport in Lilongwe, Africa’s second female president totally lost it and laid down the presidential smackdown with a furiously sarcastic tirade in which she lectured the would-be do-gooder on the meaning of kindness, accused her of blackmail and bullying, lamented her failure to perform “decent music,” and compared her unfavorably to Chuck Norris, Bono, and a trio of English soccer players. It’s funny, but it’s also a classic takedown of the astonishing entitlement of white savior types and their puffed-up pretensions. Here’s her statement in all its glory:

We had been studiously avoiding coverage of Madonna’s latest trip to Malawi, but such is the deliciousness of the excoriating 11-point press release put out yesterday by Joyce Banda that we couldn’t resist wading in. These two had previous — Madonna’s people had scapegoated Banda’s sister over a botched school project — and the latest visit was something of a surprise as the singer was widely supposed to have been declared persona non grata. Last week Madonna sent Banda a weird overfamiliar hand-scrawled note which seemed to piss Banda off to the extent that she immediately leaked it. Finally, enraged by Madonna’s whining to the international press about having to check in on departure at the airport in Lilongwe, Africa’s second female president totally lost it and laid down the presidential smackdown with a furiously sarcastic tirade in which she lectured the would-be do-gooder on the meaning of kindness, accused her of blackmail and bullying, lamented her failure to perform “decent music,” and compared her unfavorably to Chuck Norris, Bono, and a trio of English soccer players. It’s funny, but it’s also a classic takedown of the astonishing entitlement of white savior types and their puffed-up pretensions. Here’s her statement in all its glory:

Claims and misgivings have been expressed by Pop Star, Madonna and her agents, against the Malawi Government and its leadership for not giving her the attention and courtesy that she thinks she merits and deserves during her recent trip to Malawi.

According to the claims, Madonna feels that the Malawi Government and its leadership should have abandoned everything and attended to her because she believes she is a music star turned benefactor who is doing Malawi good.

Besides, in the feeling of Madonna, the Malawi Government and its leadership should have rolled out a red carpet and blast the 21-gun salute in her honour because she believes that as a musician, the whiff of whose repute flies across international boundaries, she automatically is candidate for VVIP treatment.

For not receiving the attention and the graces that she believes she deserved, Madonna believes someone, not lesser in disposition than the President’s sister, Mrs. Anjimile Mtila-Oponyo, has been pulling the strings against her following their earlier fallout bordering on a labour dispute.

State House has noted these claims and misgivings. State House has followed the debate incidental to these claims with keen interest, and would wish to respond as follows to put the record straight:

1. Neither the President nor any official in her government denied Madonna any attention or courtesy during her recent visit to Malawi because as far as the administration is concerned there is no defined attention and courtesy that must be followed in respect of her.

2. In any case, even if the defined parameters of attention and courtesy existed in respect of Madonna, the liberties of discretion to give or not to give that attention or courtesy would ordinarily and naturally remain the preserve of the host. Attention or courtesy is never demanded.

3. Granted, Madonna has adopted two children from Malawi. According to the record, this gesture was humanitarian and of her accord. It, therefore, comes across as strange and depressing that for a humanitarian act, prompted only by her, Madonna wants Malawi to be forever chained to the obligation of gratitude. Kindness, as far as its ordinary meaning is concerned, is free and anonymous. If it can’t be free and silent, it is not kindness; it is something else. Blackmail is the closest it becomes.

4. Granted, Madonna is a famed international musician. But that does not impose an injunction of obligation on any government under whose territory Madonna finds herself, including Malawi, to give her state treatment. As stated earlier in this statement, such treatment, even if she deserved it, is discretionary not obligatory.

5. It should be put on record that Madonna did not come to Malawi at the invitation of the President nor her government. In other words, she was neither the guest of the President nor of her government.

6. For all that is known, she came to Malawi like any other visitor that feels like coming to Malawi. Such visitors don’t have to meet with the President and are never amenable to state attention or graces.

7. If the argument is that because she is an internationally renowned star, and, therefore, Madonna believes she deserved to be treated differently from other visiting foreigners, it is worth making her aware that Malawi has hosted many international stars, including Chuck Norris, Bono, David James, Rio Ferdinand and Gary Neville who have never demanded state attention or decorum despite their equally dazzling stature.

8. Among the many things that Madonna needs to learn as a matter of urgency is the decency of telling the truth. For her to tell the whole world that she is building schools in Malawi when she has actually only contributed to the construction of classrooms is not compatible with manners of someone who thinks she deserves to be revered with state grandeur. The difference between a school and a class room should be the most obvious thing for a person demanding state courtesy to decipher.

9. For her to accuse Mrs. Oponyo for indiscretions that have clearly arisen from her personal frustrations that her ego has not been massaged by the state is uncouth, and speaks volumes of a musician who desperately thinks she must generate recognition by bullying state officials instead of playing decent music on the stage.

10. For all that is known, Mrs. Oponyo has never been responsible for arranging state meetings with foreigners who are looking for those meetings. If Madonna was indeed a VVIP and a regular guest of State Governments as she wants to be seen and treated, she would have been familiar with procedures that have to be followed to get such meetings. They don’t happen by simply sneaking into a country whose President and Government you scarcely desire to meet.

11. Even if Madonna followed the procedures to have her meetings with the President or government officials, the administration reserved all its rights to grant the meetings or not.

It must be noted that the President, Her Excellency Dr. Joyce Banda and her Government are ready to welcome any philanthropist seeking to assist in improving the welfare of the people of Malawi knowing that Her Excellency, herself, is a known philanthropist. However, acts of kindness must always remain as such; they must not smack of blackmail. In addition, let philanthropists not hold to ransom the President and any official of her Government because they showed some kindness to any Malawian.

Whereupon Madonna’s PR guy Trevor Neilson (who doesn’t seem to be too great at his job judging by the way in which a routine baby-hugging photo-op has descended into a hilarious international shitshow) hit back, giving quotes to The Globe and Mail reporter Geoffrey York. I like to think that by this time Neilson had googled “David James” and was aware that Joyce Banda just compared his client to a veteran English goalkeeper.

[Neilson] said Ms. Banda is “using her office to pursue her sister’s financial interests.” He also rejected the government’s claim that Madonna’s charity had merely built 10 classrooms, rather than 10 schools.

The communities that received the school buildings “are simply overjoyed to have them,” Mr. Neilson said in an e-mail to The Globe and Mail. “In many of these communities, students were previously learning under trees. … The schools were built in the model of schools all across the country and around the world.”

He said Ms. Banda appointed her sister to a senior position in the Education Ministry, where she is using her office “to pursue her grudge” against Madonna’s charity. “I have been contacted by other foreign donors to Malawi who are interested in why the government is behaving this way.”

It’s (another) very serious allegation against Joyce Banda (and her sister), and it’s hard to believe there’s much substance to it.

It’s worth reading what Wayne Barrett, one of the finest New York City journalists, reported about that audit of Banda’s sister. In a piece published in The Daily Beast in April 2011 on Raising Malawi and Madonna’s devotion to Kaballa, Barrett deals specifically with the charges against Oponyo:

More recently, (Mark) Fabiani (who did damage control for Bill Clinton during the Monica Lewinsky scandal) and Neilson have successfully diverted attention from Madonna and the (Kaballa) center by announcing that Neilson’s group has completed a report pinning much of the blame on Raising Malawi academy director Anjimile Oponyo, the sister of Malawi’s first female vice president. The report accused her of “outlandish expenditures,” including a high salary, a car, housing, and a golf-club membership. Putting aside the fact that these items were included in her contract by Madonna aides, the actual expenditures seem trivial in the face of the $3.8 million lost on the school project. The golf membership cost a mere $461.27 a year and was offered as an aid to networking with government officials and potential donors. The car that was bought for her was a reconditioned 1996 Toyota. Her salary, $96,000, was actually a pay cut from previous positions she had held at the World Bank and the United Nations. Oponyo, who was interviewed by Madonna herself, agreed to move to the impoverished country with four of her six children. (If she had been posted in Malawi by the U.S. State Department, she would have received cost-of-living and hardship allowances, and educational and living-quarters benefits that would have added $150,000 to her salary.)