Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 476

April 19, 2013

Weekend Music Break

This year’s turning into a good year for quality music videos. Here’s another selection of 10. First one below is a single from Durban’s Nandi Mngoma’s new album (she has a fancy blog though there’s more chance of catching updates via her Twitter account): South African dance as you know it.

Next, finally here: the first video for OY’s debut record — remember Boima’s recent write-up — delivers. Shot in Accra, Ghana. YouTube notes tell us the dancers are Bugi Bust. Well here you have it:

Also shot in Accra is this video for Tawiah’s “FACes”, off her upcoming mixtape album, FREEdom Drop (yes, that’s Wanlov and Mensa in the clip):

There’s Josephine, born to a Liberian mother and Jamaican father, describing herself as having “enjoyed the advantages of a colourful West African culture as well as feeling intrinsically British”. Can’t possibly do wrong:

A beautiful oddball by SKIP&DIE whose singer Catarina Aimée Dahms, aka Cata.Pirata, is South African:

(They know how to throw a party too.)

New video for Afro-Panico’s “Matimba”. Filed under: Afro-House | Kuduro | Pantsula:

Brazilian Pan-African rap vibes from Ba Kimbuta on “Consumo” (over a Mulatu Astatke sample):

Mo Kolours also released a new video for his “Promise” tune:

There’s Outspoken & The Essence’s “own interpretation of Hip-Hop”. The track, called “The SlaveMasters Whip,” is a first from their upcoming Nomadic Wax-produced album Uncool and Overrated: God Before Anything:

And finally, on high rotation ever since it came out this month: “Azamane Tiliade” from Bombino’s album Nomad, produced by Dan Auerbach. Play it loud:

Big Brother Goodluck Jonathan

Late last year, we ran a piece on the documentary Fuelling Poverty, a 30 minute crash course on the politics, implications, and significance of #OccupyNigeria and the fuel subsidy protests of January 2012. Made by Ishaya Bako and backed by the Open Society Initiative for West Africa, the film deftly exposes Nigeria’s failed social contract. But now, though it apparently took the ruling PDP a while to become aware of it, it’s illegal to watch or disseminate. The National Film and Video Censors board, whose members are all appointed by Goodluck Jonathan, announced the ban last week. With the ruling party’s popularity falling fast, it seems Fuelling Poverty was too politically damaging for Nigerian citizens to see. Now, “all relevant national security agencies are on the alert” to ensure that the film is neither exhibited nor distributed.

The news is sadly consistent with the state of press freedom in Nigeria in the fifteen months since the fuel subsidy protests. In February and again this month, journalists who had written editorials critical of Goodluck Jonathan were harassed and intimidated. The government has shut down a radio station which criticized the way it handled a vaccination campaign. Now, as Jean-Paul Marthoz writes, “Editors think twice, reporters do not dig deeply, columnists choose words carefully.”

But in banning the film the government is brushing up against the 21st century limits to its jurisdiction. The decision to issue a ban suggests that the government doesn’t quite understand the internet; it’s possible that a ban will spread the video more rapidly (though as of writing, it had only 50,000 views). YouTube won’t take it down, and a touch of scandal can help media and information go viral. Here we are, for example, writing about it again.

Amidst hints that Goodluck Jonathan is considering another attempt to fully remove the subsidy, the government has a serious stake in the control information. Perhaps, even if it does not quite understand the internet, it understands how important it is to millions of cell phone users, increasingly using smart phones with data packages and internet access.

One year later, the long term impacts of #OccupyNigeria are unclear. Yes, the price of petrol is N97 a liter instead of N141, but none of the fundamental characteristics of the social contract have been addressed adequately. None of the more radical demands of the protests have gained traction. The government and business figures at the heart of the fuel subsidy scam continue to avoid serious consequences. Perhaps worst of all, the government has not reinvested the subsidy money in a way that has meaningfully affected the lives of the people.

However the people will not tolerate it forever. Though the same self-criticisms many Nigerians employed in explaining why there was no revolution in January 2012 applies today, another protest would at least endanger the PDP’s hold on the state. Knowing that, Goodluck Jonathan has ripped a page out of the playbook of his military predecessors, beginning to show the slightest signs of desperation.

Fuelling Censorship in Nigeria

Late last year, we ran a piece on the documentary Fuelling Poverty, a 30 minute crash course on the politics, implications, and significance of #OccupyNigeria and the fuel subsidy protests of January 2012. Made by Ishaya Bako and backed by the Open Society Initiative for West Africa, the film deftly exposes Nigeria’s failed social contract. But now, though it apparently took the ruling PDP a while to become aware of it, it’s illegal to watch or disseminate. The National Film and Video Censors board, whose members are all appointed by Goodluck Jonathan, announced the ban last week. With the ruling party’s popularity falling fast, it seems Fuelling Poverty was too politically damaging for Nigerian citizens to see. Now, “all relevant national security agencies are on the alert” to ensure that the film is neither exhibited nor distributed.

The news is sadly consistent with the state of press freedom in Nigeria in the fifteen months since the fuel subsidy protests. In February and again this month, journalists who had written editorials critical of Goodluck Jonathan were harassed and intimidated. The government has shut down a radio station which criticized the way it handled a vaccination campaign. Now, as Jean-Paul Marthoz writes, “Editors think twice, reporters do not dig deeply, columnists choose words carefully.”

But in banning the film the government is brushing up against the 21st century limits to its jurisdiction. The decision to issue a ban suggests that the government doesn’t quite understand the internet; it’s possible that a ban will spread the video more rapidly (though as of writing, it had only 50,000 views). YouTube won’t take it down, and a touch of scandal can help media and information go viral. Here we are, for example, writing about it again.

Amidst hints that Goodluck Jonathan is considering another attempt to fully remove the subsidy, the government has a serious stake in the control information. Perhaps, even if it does not quite understand the internet, it understands how important it is to millions of cell phone users, increasingly using smart phones with data packages and internet access.

One year later, the long term impacts of #OccupyNigeria are unclear. Yes, the price of petrol is N97 a liter instead of N141, but none of the fundamental characteristics of the social contract have been addressed adequately. None of the more radical demands of the protests have gained traction. The government and business figures at the heart of the fuel subsidy scam continue to avoid serious consequences. Perhaps worst of all, the government has not reinvested the subsidy money in a way that has meaningfully affected the lives of the people.

However the people will not tolerate it forever. Though the same self-criticisms many Nigerians employed in explaining why there was no revolution in January 2012 applies today, another protest would at least endanger the PDP’s hold on the state. Knowing that, Goodluck Jonathan has ripped a page out of the playbook of his military predecessors, beginning to show the slightest signs of desperation.

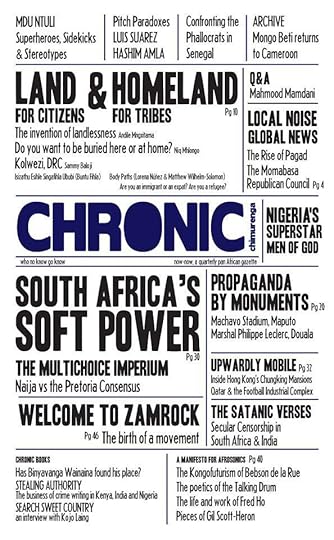

The New Chimurenga

From its inception as a one-off experiment in Cape Town more than 10 years ago, Chimurenga Magazine, founded by Jean Noel Ntone Edjabe, has evolved into arguably the most creative, incisive political arts and literary publication produced on the African continent, or anywhere for that matter. Over the years, with its highly original content and design, Chimurenga, which is also edited by Stacy Hardy, has adroitly demonstrated to its readers how to question (mis)representations of African people and politics. This week their new issue, the Chronic, launches worldwide.

Some readers might be confused since they can remember Chimurenga publishing an edition of the Chronic last year. But this is the official inaugural edition. Published in the form of a newspaper, complete with book review magazine and sports writing, the Chronic is an intrepid re-imagining of the literary magazine as we know it.

Through its reincarnation as “a gazette,” the Chronic confronts the very manner in which we take in information. By shedding light on the people and perspectives that those in positions of power would prefer to sweep under the rug, Chimurenga effectively pulls the rug out from under those very same power structures.

Within the pages of the Chronic are stories ranging from investigations into the business of moving corpses to the rhetoric of land theft and loss; from latent tensions between Africa’s most powerful nations to the soft power of the biggest satellite television provider. These stories push us as readers and thinkers to interrogate the information we receive and to reflect on how we as individuals and as communities respond (or fail to respond) to social injustices. Reading Chimurenga represents the essential beginning of the process to reconfigure the social archive of our collective memory. This is a process of unlearning, of resistance, of disassembling constructed versions of history, while daring to reengage with our humanity, our diversity and our revolutionary spirit.

The Chronic features writing and artwork from filmmaker Jean-Pierre Bekolo, writer Binyanvanga Wainaina, Rustum Kostain and Nic Mhlongo, academics Dominique Malaquais and Mahmood Mamdani, provocateur Andile Mngxitama, Gwen Ansell, Patrice Nganang, Achal Prabhala, Karen Press, Paula Akugizibwe, Tolu Ogunlesi, AIAC’s Sean Jacobs (who was also present for some of the early issues as a contributing editor), Harmony Holiday, Howard French, Billy Kahora and others.

To get a copy of the Chronic, go here. To read articles from past issues of Chimurenga, go here.

Bonus: To put some faces to Chimurenga, here’s a video AIAC’er Dylan Valley made of Chimurenga around the time they won the Prince Claus Fund prize in 2011:

April 18, 2013

5 New Films to Watch, N°24

The Revolution Won’t Be Televised is Rama Thiaw’s (born in Mauritania, grew up between Senegal and France) second long-feature film. She documents one year in the life of Thiat and Kilifeu, members of the Senegalese Keur Gui band who went on to organize the ‘Y’en a Marre’ movement. This will probably not be the last documentary on the collective. (Related: ‘Y’en a Marre’ doesn’t have an English Wikipedia entry, so Ethan Zuckerman created one.) Further South, Cape Town Hip-Hop (is it a movement?) gets portrayed in Die Hip in Kaapse Hop (“The Hip in Cape Hop”), featuring familiar and less familiar artists such as Dplanet, Rattex –that’s his tune “Welcome to Khayelitsha” in the trailer below–, Emile YX, Codax, Brazuka, graffiti artist Falko, Shameela ShamRock, Driemanskap, Ready D, Rezzano, Azul, and Bliksemstraal. Produced by MCL Pictures and LS Design Lab:

On December 17, 1962, Mamadou Dia, President of the Senegalese Council of Ministers, was arrested and given a life sentence, accused of organizing a coup d’état by his friend and companion Leopold Sedar Senghor. He would be imprisoned with four of his closest ministers. Among them, Joseph Mbaye, Minister of Rural Economy, uncle of Ousmane William Mbaye, who made a documentary about what happened in the run-up to that day:

Les Rêves Meurtris (“Shattered dreams”) is a short film by Hady Diawara, dedicated to Yaguine Koïta and Fodé Tounkara, the two young men from Guinée-Conakry who froze to death as stowaways on a flight to Belgium back in 1999:

Une Si Belle Inquiétude (“Such a beautiful restlessness”) is a 12-minutes short by Brahim Fritah, in which he looks back on his travelings between France and Morocco through the use of some of the (archival) photos made along the way:

Bonus: you can watch the film in full over at French news website Mediapart.

Africa is a Great Country to Photograph

Kicukiro, Kigali, Rwanda.

Swedish photographer and visual artist Jens Assur has spent ten months producing an exhibition of 40 enormous-size, large-format photographs chronicling structural patterns in the everyday life of twelve of Africa’s rapidly-changing urban centers, currently showing at the Liljevalchs konsthall in Stockholm. And by some coincidence, he’s gone for a title of similar intent as this blog’s: the whole thing is titled “Africa is a Great Country”. We got the opportunity to talk to Jens Assur about the exhibition, the criticism it has received and about broader issues on the representation of Africa and visual clichés in general.

What was your idea with the title of the exhibition?

It plays on us Swedes’ preconceived notions of what Africa is. No-one would think to conflate, say, the economies of China and Afghanistan into one big picture, and yet it happens all the time when talking about Africa, as if it wasn’t incredibly diverse. And yes, of course I’m trying to get people to react, that’s part of the point.

Talking about reactions, what do you think about the opinion piece by two researchers at the Nordic Africa Institute about your exhibition, criticizing your exhibition for conflating Africa into one whole?

I welcome their article. They bring out their knowledge and their experiences, which is important. But of course they’ve misunderstood the intended irony of the title.

Victoria Falls, Zimbabwe.

What generally are you trying to show?

From the beginning, we wanted to tell another side of Africa: taking it seriously, not taking pictures of pretty women in colourful clothing, bustling markets and cute animals. An Africa where 1/4th of the population now is middle class, where in Kenya 55% of all financial transactions are done by mobile phone; an Africa where giant building projects happen all the time, often backed by hugely escalating Chinese investment. There are enormous new residential projects, nearly always closed-in gated communities where first the land is bought, then the walls go up, and then the buildings. Road systems, often built in the 40s and 50s that are unable to cope with an enormous increase in car traffic and congestion. And societies where cars are becoming a necessity, with huge out-of-town shopping centres – Gaborone for instance has practically become like Los Angeles. To an extent, it’s a reflection on our cities here too, what’s happened, is happening and will happen in the future.

Generally, the exhibition has quite a positive view on what’s happening; a narrative of poor people pulling themselves up. But I don’t think my job as an artist is to give answers. Society is neither straight-forward nor simple. Still, we constantly had to ask ourselves questions: do we just want to show the richest and most successful examples? Probably not. And if we mix it up, do we risk saying nothing of any importance whatsoever? At one point we also suddenly realized there were almost no women in the pictures. Is it because we consciously chose masculine places, building sites, harbors? Or is it because women are relatively absent in many African cityscapes?

Why have you chosen to use this enormous photographic format, 18 x 13 centimeter negatives producing 2,5 x 3,5 meter pictures?

To an extent it’s about letting the viewer come into the image. It also allows us to use an incredible level of detail, with longer exposure times giving a huge, sharp depth-of-field, so the viewer can take in the whole structure, all the parts, all the details. This also allows occurrences to be slow and dignified, unhurried. Many photo journalists claim that you have to come right up close to individuals to create a sense of understanding, but instead we’ve taken a step back, further out, and used the large-format camera’s ability to tilt and shift to be capture large wholes, to show complete structures.

Lake Malawi, Lilongwe, Malawi.

Tell us about the idea behind the exhibition, how did it come about?

The very beginning of the genesis of the exhibition was way back in 1992, after my first journey to Africa as a photo journalist, to Mogadishu in the middle of the civil war. I took a picture of a nurse cleaning the grenade wound of a young boy at Keysaney hospital, and it was published in Sweden’s biggest newspaper. And it got a lot of attention, it generated a lot of discussion. That picture became proof to me that you can communicate with pictures alone, and I ended up going back to Africa again and again as a newspaper photographer over the next decade: to Angola, Mozambique, South Africa, Congo, Côte d’Ivoire and of course the horror that was Rwanda during its civil war. My reality for so many years was watching death and suffering, and taking pictures of it.

I don’t regret taking those pictures at all. They were important pictures, and I think each one was individually true. But to a large extent it’s only these pictures of death and suffering, and pictures of the picturesque Africa travel magazine, that ever get to represent the continent in media here. Swedes still think of the Ethiopian famine and Live Aid when you mention Africa. So perhaps taken together, these pictures as a whole don’t give a true image of a diverse continent of 54 countries, you know? Anyway, for much of the 2000s I’ve been focusing on our own society, including in my big project Hunger, which is about how our societies have come to treat consumption like a bulimic treats food, stuffing itself and then purging it away. I took pictures of the global flow of goods and the huge, sprawling mega-cities, with an enormously growing global middle class. And Africa has entirely become part of this. So I had the idea to make an exhibition of African cities, from Cairo to Johannesburg, from Monrovia to Dar es Salaam, and the structural changes that happen to them. I’m the first to acknowledge that this only shows one part of Africa, but it’s a different one than usually shown.

The conception of the exhibition was entirely mine and Studio Jens Assur’s. I’ve had external financial backers, but they’ve not been given access to the material in advance at any time. And it’s been produced very fast for a project of this scale, to not lose the zeitgeist of what’s happening right now.

Golden Jubillee Tower, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania.

You stress the different clichés in photographing Africa. Is it difficult to avoid falling into those tired visual ideas?

Not really, I think. And I don’t want to go too far: by always avoiding the stereotypes, I risk missing opportunities to tell possible stories. If I go to an extreme, say only trying to show an Africa without problems, it will also become a stifling generalization. It’s a definite risk. That said, I’m generally uninterested in the clichés. Just this month, I specifically rejected a plan to have African drumming at the exhibition launch…

To an extent you’ve dealt with the problem of visual clichés about Africa before. For instance, in your short film The Last Dog in Rwanda, there’s a particularly drastic scene where the main character, a photographer, moves a corpse in order to try to make it fit better into a particular archetypal image.

There’s a challenge in the world of photography generally, in that a lot of people take pictures to try to affirm their own artistic view. This in turn is connected to previous works, and these works in themselves become a measuring stick whereby the pictures are judged, these previous works are seen as the truth. This is especially true of journalism, where there’s often a finished story already, a prepared mold for the narrative to fit into. In fact, some of the criticism I’ve got has been precisely that the exhibition doesn’t fit precisely into one mold, that it’s too indistinct, that it doesn’t just show the growth but other thing as well. People feel at home in clichés.

Although it’s been generally well received by the audience, I’m surprised about how little debate it has seemed to generate in the media about our image of the world and how we choose to communicate. Perhaps it’s unsurprising considering these are the same people who generally work by telling a straightforward story, and they seem to know very little about Africa and about photography. Instead, the critique seems to be almost like a sporting event: it’s about the size, sharpness and subject matter of the pictures, whether they’re too pretty, too ugly, to city-focused or not city-focused enough. It’s as if I’m on skis, hurtling down a mountain and they expect me not to knock into various hurdles.

Vila Olimpica, Maputo, Mozambique.

Have you received any criticism for being, to put it crudely, a white man going on a photo expedition to Africa? Falling into that sort of form, dating back to the colonial era? Any criticism in general about the potential power issues?

Actually, no. I think that sort of issue is more interesting, and quite reasonable, a healthy line of questioning. All I can say is that I’ve had the opportunity to do this, and I’ve tried my best to communicate to Sweden the things I’ve come to understand. I just can’t let myself be stopped by this type of doubt. I don’t have any claims to be telling a complete truth, and I definitely encourage people to seek out a variety of sources.

Do you think the exhibition would have been different if you’d been a photographer from Africa?

Of course, or anyone else for that matter. Of course my cultural and social background has influenced me. Compare it to interior design: in Sweden everyone obsesses about vintage furniture, but in Los Angeles for instance they’d just look at you questioningly; there the ideal is that everything should be new and forward-looking. And it’d be different between African photographers! Imagine someone from Lilongwe compared to someone from Lagos – that’s like comparing [the small regional town] Visby to São Paolo. Africa is incredibly diverse.

So what’s going to happen to these pictures after the exhibition here in Stockholm?

One copy of the exhibition is going to be touring other Swedish art museums over the next year. Another copy will be shown in three large African cities, although I can’t quite reveal which ones yet, I hope to have it finalized before June. We’ve also had interest from other countries, so that may be happening too.

* Africa is a Great Country will be on at Liljevalchs konsthall until 2 June.

April 17, 2013

Cinderella is Pissed

A prominent South African, his name is unimportant, has yet again lit up the local blogosphere by trivializing sexual violence. He did so by describing gang rape as a free-for-all picnic and then by claiming to have had sexual relations with minors, and this when he was a teacher. The comments would be ‘unfortunate’ anywhere, and the question of sexual relationships with minors would be a matter of criminal inquiry anywhere as well. In South Africa, they carry a particular historical and existential weight and burden. With that in mind, consider a current exhibition at Blank Projects, in the Woodstock section of Cape Town. It’s called “BLOWN”, and it marks the return, of sorts, of Belinda Blignaut to ‘the scene’.

Blignaut was a prominent conceptual artist in the early to mid 1990s. She exhibited at the 1995 Africus Johannesburg Biennale:

South African artist Belinda Blignaut’s work was calculated to evoke a more immediate sense of discomfort for the viewer, through its confrontational exploration of gender and identity. Blignaut scattered posters of herself, half-naked and bound, throughout Johannesburg on bus stops and in public toilets, with no explanation but a local phone-number. Calls were received by an answering machine which was installed in the exhibition space in the ‘Museum Africa’.

From her first exhibition, Antibody, in 1994, to the present, Blignaut’s work has been visceral, arresting, and prescient:

Antibody, a bleak and foreboding little square, in which cover boards and interior are marvelously integrated, operates through visual texts and images bleeding upwards between the pages. What are signified through the interplay between transparent and opaque information are deeply imbedded wounds and the passage of time over which damage is done and healing needs to take place.

1994, as the nation began to begin to think of emerging from the apartheid regime, Blignaut’s art insisted on posing the problem of women’s place in a ‘rainbow’ built on so much violence against women, and on so much violence period. Her rainbow’s colors emerged both from and with wounds, and the colors bled.

Then, for almost twenty years, Blignaut wasn’t much heard from, and now she’s back, with only her second solo exhibition. There’s a lot going on, but for now, consider the “BLOWN” Series itself. Visualize this: a steel slab, 60 cm wide, 130 cm tall, 4 cm thick; perforated and punctuated throughout with “bullet holes from various firearms.” Across the entire surface, in dripping red letters: “CINDERELLA IS PISSED.”

Blignaut transforms “life size” into a death-sized frame and syntax that somehow, also, maybe, offers a dark glimmer of hope. Cinderella is pissed. She’s pissed at the sexual violence, she’s pissed at violence against women and girls, she’s pissed at the trivialization, she’s pissed at the Cinderella-fication and the Rainbow-ification of people’s struggles for a decent and joyful life. It’s a barely lit and dimly seen hope — but it is something.

As Blignaut ‘says’, in “Why I Make”:

In Belinda Blignaut’s South Africa, as in the South Africa of so many women and girls across the country, the fire next time is burning right now.

* BLOWN runs until May 5 at Blank Projects, Cape Town, South Africa.

Yes, some Africans do remember Margaret Thatcher fondly

Today is Margaret Thatcher’s funeral, to which guests have been asked to “wear full day ceremonial dress without swords.” Remember when we blogged about Margaret Thatcher’s terrible legacy? Read it again here and here. We were emphatic that “Africans don’t remember Margaret Thatcher fondly.” Well, we were wrong. Some Africans do like Margaret Thatcher. Here’s a gallery of 10 of them, some of whose words have been repeated across Western media:

* Ibrahim Babangida, the former “military president” of Nigeria for much of the 1980s, who in a radio interview talked about taking advice from Thatcher (she visited the dictator in 1988, above) to have a policy of “constructive engagement” with South Africa. On her advice he then invited the white South African ruler FW de Klerk to Nigeria. I can’t only imagine what they discussed.

* Talk of FW de Klerk. He was one of the first people to RSVP for Mrs Thatcher’s funeral. He called her “a friend.” He can’t stop himself. If you can remember, as late as 2012 de Klerk still publicly expressed his opinion (on CNN) that Apartheid was a good idea. He later came up with a half apology.

* Then there’s Dambisa Moyo, Zambian former banker, who gave us the badly researched book “Dead Aid” and who frequently argues that what Africa needs right now is more free market capitalism. She tweeted that Thatcher was a “leader and pioneer.” We’re not sure for what.

Sad news on the passing of Margaret #Thatcher.Leader and pioneer… #IronLady

— Dambisa Moyo (@dambisamoyo) April 8, 2013

* Goodluck Jonathan–who has a record himself of disregarding the wishes of his subjects–said Thatcher was “one of the greatest world leaders of our time.” He also thanked her on behalf of all Nigerians and those “whose lives were positively touched by her dynamic and forward-looking policies.”

* Daniel arap Moi, former Life President of Kenya and now also a noted feminist: Mrs Thatcher “was a great role model for women who want to join politics.” He continued: “As the first British female Prime Minister and political party leader, Mrs Thatcher has inspired many women worldwide to venture into political leadership.” Oh yeah? Go tell that to Glenda Jackson.

* Uhuru Kenyatta, the new President of Kenya (and a man of peace) wanted to best Moi. Who once said the electoral choices in Kenya are between different rightwing variants? “Lady Thatcher was a decisive and firm leader who will be remembered across the world for the role she played in pushing for free market economic ideology. To everyone who knew Lady Thatcher and had the opportunity to work and interact with her, the former Prime Minister was well respected as an iron lady of outstanding ability.” Sounds like he just watched the Meryl Streep movie (him and everybody who reads Linda Ikeji’s blog).

* A lot of other South African politicians made the cut. Apart from de Klerk there’s Mangosuthu Buthelezi, leader of the Inkatha Freedom Party, which fought a proxy war on behalf of the Apartheid dictatorship (disguised as “black on black” and “Zulu tribal war”) against opponents of Apartheid during the 1980s and early 1990s. Buthelezi will be in London today. Before he left, he mumbled on about two of them being “kindred spirits” and being committed to “a non-communist outcome to the South African liberation.”

* The very populist leader of South Africa’s Democratic Alliance, Helen Zille (a self-styled ‘Iron Lady”) said: “[Mrs Thatcher] did not allow populist politics to define her position on anything.”

* Commenters on South African news websites deserve their own special mention. See how the privileged readers of Business Day reacted to a piece by ANC intellectual Pallo Jordan on Thatcher’s legacy (just scroll down, but first read the piece).

* Finally, there was Idi Amin.

April 16, 2013

Takeifa: Rocking Dakar

Some music videos take you by surprise. One such video is the brand new offering by the Senegalese band Takeifa, called “Supporter”. Takeifa is band of siblings from the Keita family headed by brother Jac. According to soundcloud fable, Jac Keita experienced his musical calling at the tender age of 11, begging his father for an old guitar. Finally acquiring a guitar without strings, he cleverly fashioned makeshift strings from bicycle break cables. Before long Jac was recognized for his prodigious talent and recruited three of his brothers and one sister to join him in making music. The Keitas moved to Dakar in 2006 and established themselves as reliably strong performers in Dakar’s music scene.

With Jac’s leadership and vision, the Takeifa sound has become a welcome alternative to the more common mbalax music that has traditionally dominated the Senegalese popular music scene.

The song “Supporter” is further evidence that Takeifa is adding some creative flavor to Senegal’s already rich musical heritage. “Supporter” represents the continuing evolution of the Takeifa sound, blending elements of hard rock and Hip-Hop with melodic wolof vocals. In the video for “Supporter”, Takeifa’s dynamic talent is accompanied by mesmerizing visuals. The band performs amidst an intense chess game that comes to life with juju-emblazoned traditional laamb wrestlers, slow motion breakdancing, jousting horsemen and the fierce battle of a king and queen:

In 2009 I found myself in Dakar craving a dose of live music. After consulting a few friends in town I ended up at a rather impressive performance space and restaurant called Just 4 U. Situated just across the street from the legendary Cheikh Anta Diop University, Just 4 U was an oasis in Senegal’s bustling capital city. That night I was open to hearing any of the wonderfully rich musical styles that Senegal is known for: the hypnotic beats of Pape Diouf, Titi and Thione Seck, the conscious Hip-Hop of Daara J, the soothing kora of the country’s many griots, but what I heard that night was different. Taking the stage was Jac et le Takeifa. I was blown away by Jac’s unquestionable guitar talent, the band’s ability to confidently incorporate diverse music styles and the stellar radiance of the sister, Maa Khoudia, the most hardcore female albino bass player south of the Sahara.

I left at the end of the night, my thirst for live music quenched, thinking, Takeifa, now this is a name to remember.

April 15, 2013

What the post-racials are looking for

April marks the springtime festival of fertility and harvest, Holi, which is celebrated throughout northern India. Because Holi is a yearly event that includes a large amount of revelry, without the obvious presence of the sacred, it’s become adapted by some odd pockets of people. I even saw a “Festival of Colours Run” race recently: you run a 5 km race and get bombed by coloured powder (immediately after that, I found a blogpost titled, “The color run is the most cultural appropriative shit I’ve ever seen” on the Blog “India is Not a Prop Bag”). What a pity that the organisers and participants of various “Holi Fests” in South Africa didn’t get that memo. Even calling it “Holi Fest” irritates a little—as if it is now commodified nicely into yet another Neohippy Wellingtons meets muddyshit-and-rapedrugs-in-drinks music festival.

There were Holi Fests in Cape Town and Durban (both equally silly), but the video of the Johannesburg leg left us at AIAC wondering if the stars of “Jersey Shore” were sent on a cheap version of Spring Break with some ground up chalk dust. The original posters took down the video, which was playing freely on YouTube last week—most likely, a featured performer was embarrassed enough that she/he asked to have it taken down—but not before a whole bunch of us saw it and many of our readers sent it around to us. Now, we found out that the video has been uploaded again:

There you have it. The video features young South Africans (overwhelmingly white) being predictably drunk, embarrassing themselves at the “‘We Are One’ Festival” (assume that’s a reference to the 1990s TV slogan “Simunye”). As AIAC Dylan Valley summed it up first: it basically looks like “a piss-up where people throw colored powder at each other.” Indeed, we see mostly white people plastered in what appears to be very cheap pastel powders, mouthing such gems as:

“I actually went to the real Holi fest in India and I have to say this is much better”; “I hope I don’t turn Indian”; and “Get super colorful and get pictures and get DRUNK! Fuck girls sideways!”; “YOLO!”; also this dude: “There’s plenty bitches but they all look the same because they’re all so colourful.”

Three black guys also make their debut—so it is diverse like a “rainbow” we suppose. Then there’s that awkward moment when one dude who’s sober enough to remember his schooling gets what he’s doing: “besides the really fucking terrible music, and exploiting someone’s else’s sacred festival… it’s a chance to get drunk and get colourful”.

Deep. We get what the post-racials are looking for: to be “colourful” but without the trouble that comes with being colourful.

The video’s one redeeming quality: Dylan again: “At least the makers of the video seemed to intend to show it up for the farce that it is.” And I have to agree, though they don’t seem to know much about the mythologies surrounding Holi, why it is a significant moment of revelry and merrymaking, or about the music they picked as the soundtrack.*

The song playing at the opening of the video is an invocation to Lord Shiva: “Satyam Shivam Sundaram” (Truth is Eternal and Beautiful); “shivam” can refer directly to Shiva, or to the idea of the eternal. The songstress is Lata Mangeshkar, who is as beloved and famously mythologized as any goddess, singing in a style that truly does invoke the sacred. Here’s the original, created for a movie directed by Raj Kapoor. The film is about a vain man who can’t see past the skin-deep beauty for which he hankers, and learns to see past his earthly obsessions and find love and beauty in a deeply scarred human being only when his earthly projects are destroyed. The opening scenes in the music video will tell you that despite some pervasively repressive sexual notions, Indians are no prudes: the fire-damaged heroine is lovingly ‘bathing’ a lingum (a stone phallus that symbolises Shiva’s virility) set on a yoni (the goddess Shakti, who symbolises the strength of female creative energy), invoking the arrival of love and fecundity into her life.

In our on-again-off-again YouTube video of Jozi’s Holi Fest, some neo-Punjabi dance music is cued in after Lata Mangeshkar sings her invocation to Shiva. That’s also somewhat accidentally appropriate, because bhangra is traditionally played at revelries following harvest, though morons shouting “bitches are so colourful” are a rarity at such moments of celebration.

In Cape Town, things went down like this officially, and like this in reality. And Durban’s version boasted free entrance to the beach (glaringly obvious that the festival of Holi should never require an “entrance” fee, since…well, like one of Dylan’s friends said: its like getting people to pay to fast for Ramadan). Apparently, no liquor was involved, but “herb”, however, may have made a strong appearance. The presence of marijuana wouldn’t be a serious problem in any case—or somehow make Holi ‘inauthentic’: some in northern India drink a heady mix of sweet, full-cream milk and ground up marijuana buds to transport themselves to a trance-like state. It’s not like we’re objecting to people who actually find ways to understand another culture’s way of experiencing carnivalesque escape, and participate. But too often, some ‘westerner’ is busy licking a frog in the Sonoran desert or something because they want to get high—it’s not about a quest for spiritual ecstasy or oneness with Almighty Creator.

Mikhail Bakhtin, the Russian critic, described “carnival” as a literary mode evident in Medieval and Renaissance works. Using humour, subversion of hierarchies and chaos to disrupt dominant modes of structuring society, carnival frees—if only for a moment—those who are beholden to those structures. He stressed that carnival was distinct from any official or sanctioned ceremonies, providing a different space than did theatrical performances. Whereas theatre, at least that which follows western conventions, is based on creating distinctions between spectators and actors, in carnival, all are participants, experiencing a sort of “second-life” or alternate, upside-down moment in which all may, without impunity, temporarily suspend social hierarchies. Here, the actor is the spectator, and vice versa; master may be servant, the bishop a layperson, and the maid could don a man’s clothing and harass the master with the same level of disdain that power makes available in intimate zones. Such festivities provided a practical release for repressed and regimented societies, but they also had spiritual and ideological functions. Laughter, the most important part of revelry in carnival, could be directed towards anyone without impunity, and with multiplicitous meaning: happy and inclusive at one moment; mocking and disparaging in another. Thus, the grotesque is intrinsic to carnival: while there are elements of ideal and utopian in such moments of abandon and revelry, they are also open to the possibility of alienation and hostility.

Like the infamous Jersey Shorites, who frequent the boardwalks of the US’ Eastern seaboard every summer—to score deep orange tans, attempt to ‘DJ’, throw up while riding bikes completely smashed, proudly display their douchebag abs for the camera at a moment’s notice, occasionally dance with a hotel lobby plant, and then put it all on television—anyone can see that these kids in the Johannesburg “fest” are posers doing their best to do the dance of youthful bravado. Their nod to carnivalesque hedonism—however tame—is no different from that of tens of thousands of others around the world who are privileged enough to be able to indulge themselves in such expensive escapism. In any case, one can’t stop assholes from putting a statue of a “fat Buddha” in a bar, any more than one can stop these desecrators, who are busily—and completely unawares—agreeing to the commodification of their own youthful lives: that’s hardly revelry and rebel-ry. Sadly, rather than upending social conventions, and questioning hierarchies, this slew of commercial Holi fests re-inscribe and reinforce the hierarchies of an uncomfortable society. Here, Holi is for those who can afford an entrance fee, have free rein to tap into the grotesquery of carnival, and want to experience it all without “becoming Indian”.

* Holi, btw, has its origins in a couple of myths that, like many legends and fairytales, are not altogether savoury. It is generally seen as the celebration of the victory of good over evil, but much of the content of these legends favours the triumphant arrival of a new pantheon of Hindu gods over the ‘demonic’ creatures that were part of the belief system of the subcontinent’s indigenous people. The roots of one myth involve the story of “demon” king Hiranyakashyap, who, with the help of his demon sister, Holika, wished to end the life of his son, Prahlad. Prahlad, despite his father’s demonic and arrogant nature, was a faithful devotee of the god Vishnu: this terrified his powerful father, who believed himself to be the ruler of the universe, and thus, above all the gods. Holika, the sister, was enlisted to destroy the holy Prahlad. She had the magical power of immunity to fire granted her by the gods, so she leapt into a fire, and held Prahlad in middle of the conflageration. But no harm occurred to Prahlad; instead, Holika burnt in the fire: one must never use a gift from the gods for evil purposes.

Then, there’s also the story of Radha and Krishan, which is closely linked with the tradition of throwing colored powders during Holi. Young Krishna, who had a dark complexion (he’s usually painted a beautiful turquoise blue), was supposedly jealous of his beloved consort Radha’s fair skin. One day, he playfully applied colour on Radha’s face. This story still prompts young lovers to paint their beloved’s faces as an expression of love—at least on the Bollywood screen. This legend clearly reveals the subcontinent’s anxieties about our dark skinned ancestors—so there’s much to find problematic here. But part of what I like is the negotiation with self-loathing that Krishna must go through—it is an admission of his fears and envy, revealing a process of wrestling with a positioning that neither he nor Radha can control. At some point (not necessarily at the conclusion to his self-loathing), he decides to paint his love with colour, and in that action, sees his own colour as something desirable.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers