Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 474

April 23, 2013

VICE and the “new journalism model”

The business of journalism as we know it is in trouble and there’s a scramble for a “new journalism model,” with VICE.com held up as the latest prototype (see here, here and here). I am not so sure VICE is the new journalism–its partnership with “old media” (CNN, HBO) is old fashioned, it mostly produces sponsored content (nothing new there), owns an advertising agency and makes nice with Rupert Murdoch. Of course, VICE’s style represents something fresh. With its diversity of topics and irreverence, it is a vast improvement on the talking heads of cable news. But, there is also much to dislike about VICE.

There’s its cheap headlines, sensationalism, vulgarity, misogyny, the way it ridicules mostly non-Western people, and its very white, male, Anglo-American look.

On balance, VICE’s Africa coverage is more bad than good, even when they try not to—whether they cover cyber-fraud in Ghana, embark on “Guides” to Liberia and the Democratic Republic of Congo that resemble “Heart of Darkness” or exaggerate alcohol abuse in Uganda.

Basically they’re just another ambitious media company (Shane Smith, one of the founders, refers to VICE as “the Time Warner of the Streets”) interested in market share, synergy and branding. So, yes, they may be introducing a whole lot of young people to international affairs, but they also work very hard to undermine their own credibility in the process.

* This is a slightly edited version of what I wrote down when Al Jazeera English contacted me about a 60-second comment for a feature they ran on VICE on the channel’s media program, “The Listening Post.” Start watching the Listening Post feature at 13:52. My short comment was for “Global Village Voices,” a regular, short segment on “Listening Voices” that are usually included at the end of features like the VICE story. A very condensed cut of my comment–to fit into the program’s format; nothing malicious–made it onto the final version of the episode.

How to text someone you love: An interview with Temitayo Ogunbiyi

‘The Fountain of Love’, a painting by Honoré Fragonard, offers a vision of a moment in history when the aristocratic taste for luxury reflects the imminence of revolution. The rococo masterpiece is part of a collection of European art and artefacts collected by Richard Conway-Seymour, the 4th Marquess of Hertford, who spent his inherited fortune – largely based on estates in Ireland – collecting pre-revolutionary art with notorious ferocity. An acquaintance said that he had ‘great natural talent and knowledge of the world, but uses both to little purpose, save to laugh at its slaves.’ The slavery of others is an experience simulated for those who walk freely through the hushed rooms of Hertford House in central London, Conway-Seymour’s former home and the location of the Wallace Collection. Slavery and fabrics, fruits of the commercial and colonial relations between Europe and Africa, enter into the picture when Yinka Shonibare views Fragonard’s work; Shonibare’s haunting installation piece, ‘The Swing (after Fragonard)’, was the inspiration for a recent art transnational exhibition, in Nigeria and America - The Progress of Love – which attempted to map out love in the African continent and its diaspora.

‘The Fountain of Love’, a painting by Honoré Fragonard, offers a vision of a moment in history when the aristocratic taste for luxury reflects the imminence of revolution. The rococo masterpiece is part of a collection of European art and artefacts collected by Richard Conway-Seymour, the 4th Marquess of Hertford, who spent his inherited fortune – largely based on estates in Ireland – collecting pre-revolutionary art with notorious ferocity. An acquaintance said that he had ‘great natural talent and knowledge of the world, but uses both to little purpose, save to laugh at its slaves.’ The slavery of others is an experience simulated for those who walk freely through the hushed rooms of Hertford House in central London, Conway-Seymour’s former home and the location of the Wallace Collection. Slavery and fabrics, fruits of the commercial and colonial relations between Europe and Africa, enter into the picture when Yinka Shonibare views Fragonard’s work; Shonibare’s haunting installation piece, ‘The Swing (after Fragonard)’, was the inspiration for a recent art transnational exhibition, in Nigeria and America - The Progress of Love – which attempted to map out love in the African continent and its diaspora.

Unless you were in Lagos, Houston, or St. Louis in the last few months, you missed The Progress of Love, the three-part exhibition at the Menil Collection in Texas, the Pullitzer Foundation in St. Louis, and the Center for Contemporary Arts (CCA) Lagos, which closed last week. Love, as it is considered in various philosophical traditions, is a universalising emotion. How does this word, which appears in English from the primal swamp of the Indo-European language ‘family’ via old Germanic languages, came to name humanity’s most intimate relations and the general adhesive of our species? It is the limits of love’s universalism, its corruptions and ideologies, which makes The Progress of Love sound so interesting. In ‘Performing Love’, her essay for the catalogue, co-curator Bisi Sila opposed Love to the “grand narratives” of what Okwui Enwezor has called ‘Afro-pessimism’. Love, however, is manifestly an idea which allows the thirty artists included in the exhibition to consider the intersections between universalising phenomena and their regional appropriations or local resistances.

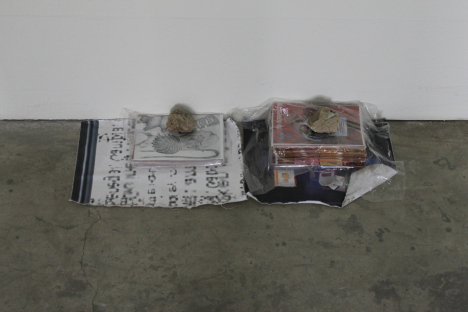

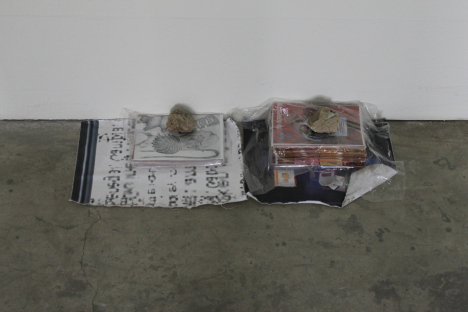

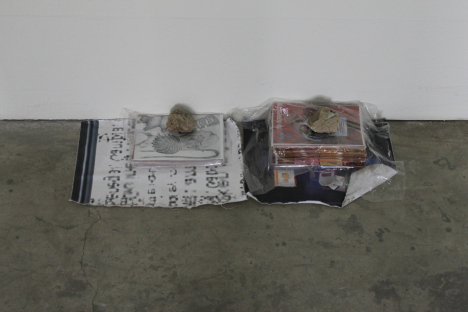

Love Text Message Book installation, part of The Progress of Love at The Pulitzer Foundation of the Arts (Photograph by Sam Fentress).

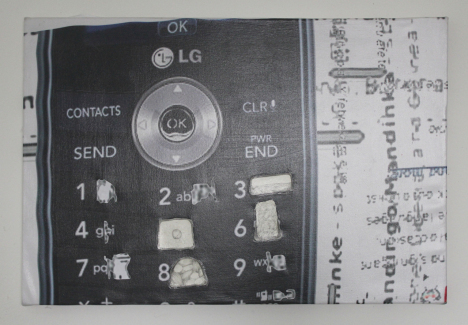

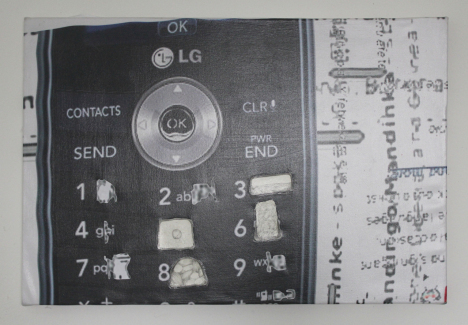

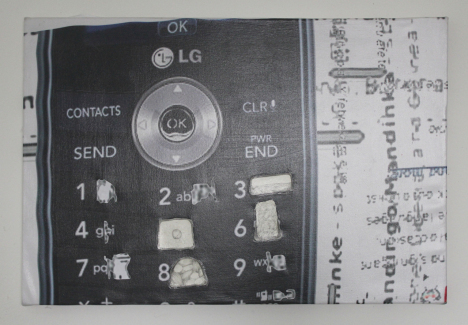

We spoke to artist Temitayo Ogunbiyi about her contribution to the exhibitions at Lagos and St. Louis. The Lovely Love Text Message Books was an interactive installation which engages with a popular phenomenon in Nigeria, of publishing books which describe the conventions of love.

Ogunbiyi: “I came across these contemporary love text message books by chance and was first introduced to Love Text Message books by Moses, one of my uncle’s domestic staff. He said to me, “Sista’, come and see this text whe’ I fit send my girlfriend”. I asked him a ton of questions about where he got it from. Then I started buying these books – I collected about 50. They’re small, 32 or 34 pages, and typically they’re sold for [the equivalent of one USD]. I was fascinated … this fabricated love that people are actually using … the low literacy rates among people who use these books, why they pick particular ones over others. This guy, for instance, he couldn’t barely write or read so it was curious to see him holding onto this book, carrying it everywhere he went.

Love Text Message Book installation, part of The Progress of Love at The Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos (Courtesy of the Artist).

“Yinka’s most recent film was shown at the Pulitzer, and what I liked about that piece, was there was this diachronic access to love, as it was being formed. Looking at the colonial era as well as the contemporary means with which love is expressed.

“I showed a couple of the books to Nigerian writers and one suggested I look at Onitsha Market Literature. I found that there were similar pamphlets first introduced in Nigeria in the 1930s, which were catering to a similar audience. There was this real interest in romance, teaching people how to romance the opposite sex—this could mean just talking to them. Some examples of these titles include How to Talk to Pretty Girls … How to Write Love Letters … and these were published from the 1930s until the late 1960s.

Love Text Message Book installation, part of The Progress of Love at The Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos (Courtesy of the Artist).

“I used my project to explore the structure of these books, how they differ from contemporary expressions of love in Love Text Message Books, and what happened in between the two eras with which these publications were associated. Specifically, I was thinking about the Biafran war that ravaged the east, which was pioneering Onitsha Market Literature, and the years of military rule when creative expression was suppressed.”

Ogunbiyi produced a series of books, entitled Lovely Love Text Message Books, which represent this popular genealogy of love.

“The books I created were responding to lots of different things. I archived images over the course of a year, researching Valentine’s Day, which is massive in Nigeria, crazy and intense. In the earliest form of pamphlet literature the form of love is one derived from Shakespeare, Western models of what love should be. It was interesting to think of Valentine’s Day and the spin-offs, the jokes that people had, the gifts that people were giving.

Love Text Message Book installation, part of The Progress of Love at The Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos (Courtesy of the Artist).

“All of the imagery that I used either came from an archive of images I have on my Blackberry, a couple from Facebook, and I did a bit of drawing. There are ten different book covers. At the Pulitzer, the books are on sale in a vending machine. We were selling them individually, in packs of 2 and 10. The packs of 2 are diptychs.

“At the CCA we set up an old-school book shop, with the shelves a bit higher than usual for those of average height. It created a situation where the viewer didn’t know if they were allowed to touch the books or not. There was a text-messaging station with 10 different text messages. Here, people could text anyone in Nigeria—for free!”

Love Text Message Book installation, part of The Progress of Love at The Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos (Courtesy of the Artist).

This invitation, offering to the viewer the chance to send a message to anyone, with the absolute condition that the love-gesture is selected from a set of ten conventional messages, speaks to the celebration of love’s freedoms and the regulation of its expression, a valuable example of love’s failure to fulfill its promise as a ‘universal emotion’. Fragonard’s vision of love invokes an aristocratic class whose paternalistic claim to care for the multitude had long been exhausted; the love represented at the Wallace Collection is, in part, the record of a mountain of exploited labour.

The Lovely Love Text Message Book project reflects, conversely, a conception of love reflected in and determined by cheap commodities, traditional and innovative ideas of love for a new reading class. It suggests, also, the tenacity with which love’s conventional demands – for playfulness and innovation within established limits - has traversed a century of huge social changes, somehow both transformed and unchanged. If there is such a thing as universal progress for humanity, love must be its destination, motor and origin.

Love Text Message Book installation, part of The Progress of Love at The Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos (Courtesy of the Artist).

The online magazine Contemporary & has published reviews of The Progress of Love at CCA Lagos here and at the Menil Collection, here.

The Progress of Love in Nigeria: An Interview with Temitayo Ogunbiyi

‘The Fountain of Love’, a painting by Honoré Fragonard, offers a vision of a moment in history when the aristocratic taste for luxury reflects the imminence of revolution. The rococo masterpiece is part of a collection of European art and artefacts collected by Richard Conway-Seymour, the 4th Marquess of Hertford, who spent his inherited fortune – largely based on estates in Ireland – collecting pre-revolutionary art with notorious ferocity. An acquaintance said that he had ‘great natural talent and knowledge of the world, but uses both to little purpose, save to laugh at its slaves.’ The slavery of others is an experience simulated for those who walk freely through the hushed rooms of Hertford House in central London, Conway-Seymour’s former home and the location of the Wallace Collection. Slavery and fabrics, fruits of the commercial and colonial relations between Europe and Africa, enter into the picture when Yinka Shonibare views Fragonard’s work; Shonibare’s haunting installation piece, ‘The Swing (after Fragonard)’, was the inspiration for a recent art transnational exhibition, in Nigeria and America - The Progress of Love – which attempted to map out love in the African continent and its diaspora.

‘The Fountain of Love’, a painting by Honoré Fragonard, offers a vision of a moment in history when the aristocratic taste for luxury reflects the imminence of revolution. The rococo masterpiece is part of a collection of European art and artefacts collected by Richard Conway-Seymour, the 4th Marquess of Hertford, who spent his inherited fortune – largely based on estates in Ireland – collecting pre-revolutionary art with notorious ferocity. An acquaintance said that he had ‘great natural talent and knowledge of the world, but uses both to little purpose, save to laugh at its slaves.’ The slavery of others is an experience simulated for those who walk freely through the hushed rooms of Hertford House in central London, Conway-Seymour’s former home and the location of the Wallace Collection. Slavery and fabrics, fruits of the commercial and colonial relations between Europe and Africa, enter into the picture when Yinka Shonibare views Fragonard’s work; Shonibare’s haunting installation piece, ‘The Swing (after Fragonard)’, was the inspiration for a recent art transnational exhibition, in Nigeria and America - The Progress of Love – which attempted to map out love in the African continent and its diaspora.

Unless you were in Lagos, Houston, or St. Louis in the last few months, you missed The Progress of Love, the three-part exhibition at the Menil Collection in Texas, the Pullitzer Foundation in St. Louis, and the Center for Contemporary Arts (CCA) Lagos, which closed last week. Love, as it is considered in various philosophical traditions, is a universalising emotion. How does this word, which appears in English from the primal swamp of the Indo-European language ‘family’ via old Germanic languages, came to name humanity’s most intimate relations and the general adhesive of our species? It is the limits of love’s universalism, its corruptions and ideologies, which makes The Progress of Love sound so interesting. In ‘Performing Love’, her essay for the catalogue, co-curator Bisi Sila opposed Love to the “grand narratives” of what Okwui Enwezor has called ‘Afro-pessimism’. Love, however, is manifestly an idea which allows the thirty artists included in the exhibition to consider the intersections between universalising phenomena and their regional appropriations or local resistances.

Love Text Message Book installation, part of The Progress of Love at The Pulitzer Foundation of the Arts (Photograph by Sam Fentress).

We spoke to artist Temitayo Ogunbiyi about her contribution to the exhibitions at Lagos and St. Louis. The Lovely Love Text Message Books was an interactive installation which engages with a popular phenomenon in Nigeria, of publishing books which describe the conventions of love.

Ogunbiyi: “I came across these contemporary love text message books by chance and was first introduced to Love Text Message books by Moses, one of my uncle’s domestic staff. He said to me, “Sista’, come and see this text whe’ I fit send my girlfriend”. I asked him a ton of questions about where he got it from. Then I started buying these books – I collected about 50. They’re small, 32 or 34 pages, and typically they’re sold for [the equivalent of one USD]. I was fascinated … this fabricated love that people are actually using … the low literacy rates among people who use these books, why they pick particular ones over others. This guy, for instance, he couldn’t barely write or read so it was curious to see him holding onto this book, carrying it everywhere he went.

Love Text Message Book installation, part of The Progress of Love at The Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos (Courtesy of the Artist).

“Yinka’s most recent film was shown at the Pulitzer, and what I liked about that piece, was there was this diachronic access to love, as it was being formed. Looking at the colonial era as well as the contemporary means with which love is expressed.

“I showed a couple of the books to Nigerian writers and one suggested I look at Onitsha Market Literature. I found that there were similar pamphlets first introduced in Nigeria in the 1930s, which were catering to a similar audience. There was this real interest in romance, teaching people how to romance the opposite sex—this could mean just talking to them. Some examples of these titles include How to Talk to Pretty Girls … How to Write Love Letters … and these were published from the 1930s until the late 1960s.

Love Text Message Book installation, part of The Progress of Love at The Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos (Courtesy of the Artist).

“I used my project to explore the structure of these books, how they differ from contemporary expressions of love in Love Text Message Books, and what happened in between the two eras with which these publications were associated. Specifically, I was thinking about the Biafran war that ravaged the east, which was pioneering Onitsha Market Literature, and the years of military rule when creative expression was suppressed.”

Ogunbiyi produced a series of books, entitled Lovely Love Text Message Books, which represent this popular genealogy of love.

“The books I created were responding to lots of different things. I archived images over the course of a year, researching Valentine’s Day, which is massive in Nigeria, crazy and intense. In the earliest form of pamphlet literature the form of love is one derived from Shakespeare, Western models of what love should be. It was interesting to think of Valentine’s Day and the spin-offs, the jokes that people had, the gifts that people were giving.

Love Text Message Book installation, part of The Progress of Love at The Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos (Courtesy of the Artist).

“All of the imagery that I used either came from an archive of images I have on my Blackberry, a couple from Facebook, and I did a bit of drawing. There are ten different book covers. At the Pulitzer, the books are on sale in a vending machine. We were selling them individually, in packs of 2 and 10. The packs of 2 are diptychs.

“At the CCA we set up an old-school book shop, with the shelves a bit higher than usual for those of average height. It created a situation where the viewer didn’t know if they were allowed to touch the books or not. There was a text-messaging station with 10 different text messages. Here, people could text anyone in Nigeria—for free!”

Love Text Message Book installation, part of The Progress of Love at The Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos (Courtesy of the Artist).

This invitation, offering to the viewer the chance to send a message to anyone, with the absolute condition that the love-gesture is selected from a set of ten conventional messages, speaks to the celebration of love’s freedoms and the regulation of its expression, a valuable example of love’s failure to fulfill its promise as a ‘universal emotion’. Fragonard’s vision of love invokes an aristocratic class whose paternalistic claim to care for the multitude had long been exhausted; the love represented at the Wallace Collection is, in part, the record of a mountain of exploited labour.

The Lovely Love Text Message Book project reflects, conversely, a conception of love reflected in and determined by cheap commodities, traditional and innovative ideas of love for a new reading class. It suggests, also, the tenacity with which love’s conventional demands – for playfulness and innovation within established limits - has traversed a century of huge social changes, somehow both transformed and unchanged. If there is such a thing as universal progress for humanity, love must be its destination, motor and origin.

Love Text Message Book installation, part of The Progress of Love at The Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos (Courtesy of the Artist).

The online magazine Contemporary & has published reviews of The Progress of Love at CCA Lagos here and at the Menil Collection, here.

How to Text Someone You Love: An Interview with Temitayo Ogunbiyi

Love Text Message Book installation, part of The Progress of Love at The Pulitzer Foundation of the Arts (Photograph by Sam Fentress).

‘The Fountain of Love’, a painting by Honoré Fragonard, offers a vision of a moment when the aristocratic taste for luxury made revolution immediately necessary. The rococo masterpiece is part of a collection of European art and artefacts collected by Richard Conway-Seymour, the 4th Marquess of Hertford, who spent his inherited fortune – largely based on estates in Ireland – collecting pre-revolutionary art with notorious ferocity. An acquaintance said that he had ‘great natural talent and knowledge of the world, but uses both to little purpose, save to laugh at its slaves.’ The slavery of others is an experience simulated for those who walk freely through the hushed rooms of Hertford House in central London, Conway-Seymour’s former home and the location of the Wallace Collection. Slavery and fabrics, fruits of the commercial and colonial relations between Europe and Africa, enter into the picture when Yinka Shonibare views Fragonard’s work; Shonibare’s haunting installation piece, ‘The Swing (after Fragonard)’, was the inspiration for a recent art transnational exhibition, in Nigeria and America - The Progress of Love – which attempted to map out love in the African continent and its diaspora.

Unless you were in Lagos, Houston, or St. Louis in the last few months, you missed The Progress of Love, the three-part exhibition at the Menil Collection in Texas, the Pullitzer Foundation in St. Louis, and the Center for Contemporary Arts (CCA) Lagos, which closed last week. Love, as it is considered in various philosophical traditions, is a universalising emotion. How does this word, which appears in English from the Indo-European pool via old Germanic languages, came to name humanity’s most intimate relations and the general adhesive of our species? It is the limits of love’s universalism, its corruptions and ideologies, which makes The Progress of Love sound so interesting. In ‘Performing Love’, her essay for the catalogue, co-curator Bisi Sila opposed Love to the “grand narratives” of what Okwui Enwezor has called ‘Afro-pessimism’. Love, however, is manifestly an idea which allows the thirty artists included in the exhibition to consider the intersections between universalising phenomena and their regional appropriations or local resistances.

Love Text Message Book installation as part of The Progress of Love at The Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos (Courtesy of the Artist).

We spoke to artist Temitayo Ogunbiyi about her contribution to the exhibitions at Lagos and St. Louis. The Lovely Love Text Message Books was an interactive installation which engages with a popular phenomenon in Nigeria, of publishing books which describe the conventions of love.

Ogunbiyi: “I came across these contemporary love text message books by chance and was first introduced to Love Text Message books by Moses, one of my uncle’s domestic staff. He said to me, “Sista’, come and see this text whe’ I fit send my girlfriend”. I asked him a ton of questions about where he got it from. Then I started buying these books – I collected about 50. They’re small, 32 or 34 pages, and typically they’re sold for [the equivalent of one USD]. I was fascinated … this fabricated love that people are actually using … the low literacy rates among people who use these books, why they pick particular ones over others. This guy, for instance, he couldn’t barely write or read so it was curious to see him holding onto this book, carrying it everywhere he went.

Love Text Message Book installation, part of The Progress of Love at The Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos (Courtesy of the Artist).

“Yinka’s most recent film was shown at the Pulitzer, and what I liked about that piece, was there was this diachronic access to love, as it was being formed. Looking at the colonial era as well as the contemporary means with which love is expressed.

“I showed a couple of the books to Nigerian writers and one suggested I look at Onitsha Market Literature. I found that there were similar pamphlets first introduced in Nigeria in the 1930s, which were catering to a similar audience. There was this real interest in romance, teaching people how to romance the opposite sex—this could mean just talking to them. Some examples of these titles include How to Talk to Pretty Girls … How to Write Love Letters … and these were published from the 1930s until the late 1960s.

Love Text Message Book installation, part of The Progress of Love at The Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos (Courtesy of the Artist).

“I used my project to explore the structure of these books, how they differ from contemporary expressions of love in Love Text Message Books, and what happened in between the two eras with which these publications were associated. Specifically, I was thinking about the Biafran war that ravaged the east, which was pioneering Onitsha Market Literature, and the years of military rule when creative expression was suppressed.”

Ogunbiyi produced a series of books, entitled Lovely Love Text Message Books, which represent this popular genealogy of love.

“The books I created were responding to lots of different things. I archived images over the course of a year, researching Valentine’s Day, which is massive in Nigeria, crazy and intense. In the earliest form of pamphlet literature the form of love is one derived from Shakespeare, Western models of what love should be. It was interesting to think of Valentine’s Day and the spin-offs, the jokes that people had, the gifts that people were giving.

Love Text Message Book installation, part of The Progress of Love at The Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos (Courtesy of the Artist).

“All of the imagery that I used either came from an archive of images I have on my Blackberry, a couple from Facebook, and I did a bit of drawing. There are ten different book covers. At the Pulitzer, the books are on sale in a vending machine. We were selling them individually, in packs of 2 and 10. The packs of 2 are diptychs.

“At the CCA we set up an old-school book shop, with the shelves a bit higher than usual for those of average height. It created a situation where the viewer didn’t know if they were allowed to touch the books or not. There was a text-messaging station with 10 different text messages. Here, people could text anyone in Nigeria—for free!”

Love Text Message Book installation, part of The Progress of Love at The Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos (Courtesy of the Artist).

This invitation, offering to the viewer the chance to send a message to anyone, with the absolute condition that the love-gesture is selected from a set of ten conventional messages, speaks to the celebration of love’s freedoms and the regulation of its expression, a valuable example of love’s failure to fulfill its promise as a ‘universal emotion’. Fragonard’s vision of love invokes an aristocratic class whose paternalistic claim to care for the multitude had long been exhausted; the love represented at the Wallace Collection is, in part, the record of a mountain of exploited labour.

The Lovely Love Text Message Book project reflects, conversely, a conception of love reflected in and determined by cheap commodities, traditional and innovative ideas of love for a new reading class. It suggests, also, the tenacity with which love’s conventional demands – for playfulness and innovation within established limits - has traversed a century of huge social changes, somehow both transformed and unchanged. If there is such a thing as universal progress for humanity, love must be its destination, motor and origin.

The online magazine Contemporary & has published reviews of The Progress of Love at CCA Lagos here and at the Menil Collection, here.

April 22, 2013

Sweet, Sweet Country: An Interview with Filmmaker Dehanza Rogers

Director Dehanza Rogers’s latest short film, “Sweet, Sweet Country” is the winner of the Audience Award at the 2013 Atlanta Film Festival. The film stars Danielle Deadwyler as the 20-year old refugee Ndizeye, whose struggles to care for herself and the family she left behind in Kenya become even more pressing when they literally show up at her doorstep. The story takes place in Clarkston, Georgia, a real life obscure southern town that became known for the influx of refugees from around the world who were settled there and the soccer team, the Fugees, that emerged from the children of these communities. Gbenga Akinnabge (The Wire, Nurse Jackie) also stars. Rogers’s film emerged from dozens of interviews she conducted in Clarkston, as well as from her family’s experiences as immigrants from Panama. Below’s a short Q&A we had with Rogers, after the trailer:

Director Dehanza Rogers’s latest short film, “Sweet, Sweet Country” is the winner of the Audience Award at the 2013 Atlanta Film Festival. The film stars Danielle Deadwyler as the 20-year old refugee Ndizeye, whose struggles to care for herself and the family she left behind in Kenya become even more pressing when they literally show up at her doorstep. The story takes place in Clarkston, Georgia, a real life obscure southern town that became known for the influx of refugees from around the world who were settled there and the soccer team, the Fugees, that emerged from the children of these communities. Gbenga Akinnabge (The Wire, Nurse Jackie) also stars. Rogers’s film emerged from dozens of interviews she conducted in Clarkston, as well as from her family’s experiences as immigrants from Panama. Below’s a short Q&A we had with Rogers, after the trailer:

How did you develop your choice of music for the film?

Rogers: I have been obsessed with music from West Africa and North Africa for years. I have this folder of music with songs that I’ve collected over the years. In my head for this film, I had Blitz the Ambassador very early on in writing. It’s this mixture of wonderful things! It’s highlife and it’s hip-hop. While we were in Clarkston, I met all these women and girls. They all knew five different languages because they’re around so many different people from around everywhere. The refugee situation is huge and its people from all over. So, I started thinking, how does the music relate to this? All the music is more or less from West Africa except for Ian Kamau from Toronto, by way of Trinidad. I thought, West African music but it’s an East African story but it still fits.

Culture in the camps clash and kind of feed off each other. You know Swahili but you know Somali and you know Arabic. There’s this mixture of all these things so I thought, what does it matter if it’s West African? What matters is the tone of it. I more or less had the same music from beginning to end. The moment I started writing, I began thinking, where does the music go to the last edit. We sent the artists the link to the story and told them we wanted to use their music. Everybody said yes. They bought the idea, they liked how we were treating their music. It was just really supportive. I got to talk to Blitz the Ambassador!

Did any of the artists bring up their own personal experiences with immigration?

I didn’t really have a chance to ask any of them about it, but I do follow Ian Kamau’s website. He’s a hip-hop social conscious artist. He is so honest. Brother is so honest that you listen to his music and you kind of get emotional. I’m like, am I really crying right now?! He talks about these very personal moments of love and loss. He is very poignant about being someone trying to support himself off of his art. Not have another job that pays his rent. That’s what I’m trying to figure out. At some point, all this is supposed to pay off where I have a job and can actually pay my rent and direct movies.

Did you already know about Clarkston specifically before writing? Was this a place that always interested you?

Did you already know about Clarkston specifically before writing? Was this a place that always interested you?

I knew a little about Clarkston. What I find interesting is that a lot of people in Atlanta don’t know about Clarkston. It’s maybe 20 miles outside the city in the east. I knew about Clarkston and had already moved to LA when there was this huge thing in the news about a soccer team called the Fugees. The New York Times did a piece on these kids and there was a book written. One of my friends sent me the article and said that this was an idea if I wanted to come home and do a documentary. I started doing research and one of my friends bought a house in Clarkston. When I went home to visit, I went around the city and even more of my friends, some Muslim, would talk about the halal market in Clarkston. I thought why is there a halal market in Clarkston? I would think there would be one in Atlanta proper but in Clarkston?

Driving around, you definitely see women from different places and men from different places. There’s a halal café and pizza shop where the men sit out and chit chat. There’s a texture to it that you feel when you walk through the community. Most of research did happen when I was back in LA but when I decided to shoot in Clarkston, I drove across the country four times in an eight month period. I met up with a friend who runs an afterschool program and he connected me with families in different apartment complexes and they let me into their homes and told me their stories. They were mostly women. At one point, I started panicking because I thought, is this story doing justice to what I want to do? Is that enough? Should I change things? I called my professor and we had a heartfelt conversation and I realized that this is just a slice of a larger idea. It’s just one story in a huge varied story about the refugee experience.

Was the story that you ended up with a story that was typical of those you spoke with or was it one that stood out to you?

It’s a mixture of different women that I’ve met over the years as well as a family story. My family is Panamanian but we’re West Indian because we came to work on the canal with the first wave of the French, Jamaican, Haitian, Grenadian. This is a family of West Indian women. Most of the men are dead. They don’t live very long. We would have Mother’s Day in Columbus, Georgia, where I grew up with my grandparents. It was me, my mother, my mother’s sister, my grandmother and her sisters. Four generations of West Indian women. Something is going to happen. Someone is going to say something. Someone is going to get upset. So some stuff kind of came out of the closet. I think I had just started college and I was confused. I asked my grandmother about it and she was not judgmental at all. Things were hard at the canal and the only option was to work for the United States’ government. What do you do?

The length of time that the lead character has been in the US is unknown. Was there a particular reason you did not reveal that?

The length of time that the lead character has been in the US is unknown. Was there a particular reason you did not reveal that?

It’s a short film and one of the things that [UCLA] pushed at us was that in a short, you cannot do a whole narrative. You have to do a moment. I don’t believe that. I get frustrated with the shorts that are an ambiguous moment that happens. The script was a lot longer, so I cut it down. The first cut was 30 minutes, I cut that down. I didn’t want the audience to think about that too much though. It becomes obvious in the film that the lead has been in the US for a while. And she’s trying to take care of her family and herself as best she can.

How did you cast Gbenga Akinnabe (who played Chris Partlow in The Wire) in the film?

I know right?! I had a producer who had a mutual friend. She sent the script to that friend who sent it to his manager. We got an email back saying that he read it, but that was it. What the hell does that mean? So I tweeted him, I heard you read the script. He replied that he really liked it and that was it. Once, again, what does that mean? I appreciate it, but is that a yes? He and I started chatting back and forth on Twitter and then direct-messaging each other. When he came to LA, I had lunch with him and one of his friends. In the conversation, he asked me, why should I do your movie? And I thought, you already said yes. We’re kind of the same goofy person so it kind of just worked out. We had to push shooting in March to August, so he gave us an entire week and came to Atlanta.

It was the first time I had worked with a professional actor. Let me tell you, I’m in love with “The Wire.” As in, obsessed with “The Wire.” It was awesome to work with him because he’s such a good actor. You get the sense that he’s a good actor from his role in “The Wire.” When I wrote the script, Chris Partlow was the character that I had in mind. There’s this one moment in that show where you see him with his family. You see him with this women and two kids. They allude to some sort of sexual abuse with him as a child. I thought about it: what about a character where you never see the other side to his life? You know there’s another life, and the audience is aware. But what you see is what you see. Before we started, I picked him up from the airport and we read the script together. Then my lead came and they rehearsed together. And then we spent three hours watching videos and clowning. And that’s when I knew… He was the one who introduced me to “ain’t nobody got time for that!” You would think that he would try to take over. But I’m the director and he would ask me, is that what you wanted, and I had no problems giving suggestions. He brought ideas to the table as well. That’s the role of the director: ninety percent of it is casting the right person. It was the first time as an artist where the thing in my head translated well. It made me really happy.

For those in the south, Women in Film and Television in Atlanta are hosting a screening on April 23 and the Little Rock Film Festival will screen the film next month.

It may be time for Mother Jones to update its Celebrity Map of Africa

UPDATED: Airports in some African countries can’t keep up with entertainers (and celebrities) either visiting for big pay days (that’s the case especially for rappers and R&B stars, and Kim K), to rehabilitate their images via PR junkets, make appearances in nightclubs, or to connect with themselves. You can create a template it seems for these kinds of visits: “When INSERT NAME HERE visited INSERT AFRICAN COUNTRY HERE.” We’ve engaged in a parlor game of sorts about this behavior on our Facebook page re the comings and goings of some of these visitors, copied at the end of this post.* But there’s more, especially when it comes to those high profile visitors bend on saving Africans or with a sense of superiority: Celebrities and entertainers from mid-level and smaller countries–from countries like Sweden, Turkey, Thailand and South Korea; oh, and China–want in. It seems they’re traveling to Africa mostly for “humanitarian” reasons and to feel better about themselves. They often have epiphanies while there about their personal, emotional state. Two of my students at The New School–Lilian Jahani and Senay Imre–have been documenting this development on a tumblr blog, Stars Love Africa — started last year.

They document, among others, the exploits of Turkish singer, Seren Serengil (that’s her in the picture above as well in the next picture below), who traveled to Tanzania in 2011. As Senay reminded me, Turkish media dubbed Seren the “Princess in Africa.” She in turn described Tanzania as “300 years behind Turkey,” wanted to adopt a baby, complimented the locals for wearing clothes, and said she was taking her cue from Euro-American celebrities: “Our celebrities generally go to Miami or the Maldives, but American and British rich people go to these places, these are not places that most of our celebrities want to go to.”

Then there’s Taiwanese celebrities Eddie Peng and Amber Kuo, who traveled to Kenya last year to help feed orphans. Amber Kuo was particularly moved by the experience: “I didn’t have a faith, but after returning from Kenya, whenever I have a meal, I would first think about the significance of the food in front of me.”

The Korean singer, Lee Hyori, traveled to Ethiopia on a humanitarian mission:

The Korean version of the Onion had some fun at her expense.

Finally, they also write about the visits by Scandinavian royalty and celebrities to a number of African countries. Read that and more here.

It may be time for Mother Jones to update its Celebrity Map of Africa.

* Not everyone goes to Africa for the same reasons or to save or feel sorry for Africans. But here’s a partial list. There’s Jay Z (here, here and here), Chris Brown (and Rihanna) went to Côte d’Ivoire to attend a music awards show (he was very well paid by organizers which angered local bloggers); Brown also went to Ghana where he goaded local police; Bono was in the Sahara; Deakin of Animal Collective went to Mali; Degrassi (!) was in Ghana; so was One Direction (they cried); Erykah Badu went to Kenya; the Real Housewives of Atlanta visited South Africa; Rick Ross went to Nigeria, South Africa and Gabon (Jay Z’s favorite destination); and Emma Thompson and her adopted Rwandan son (all color-coordinated) were in Liberia. Okay my head is about to explode.

Stars Love Africa

African airports can’t keep up with entertainers (and celebrities) either visiting for big pay days (that’s the case especially for rappers and R&B stars, and Kim K), to rehabilitate their images via PR junkets, make appearances in nightclubs, or to connect with themselves. You can create a template it seems for these kinds of visits: “When INSERT NAME HERE visited INSERT AFRICAN COUNTRY HERE.” We’ve engaged in a parlor game of sorts about this behavior on our Facebook page re the comings and goings of some of these, copied at the end of this post.* But there’s more: Celebrities and entertainers from mid-level and smaller countries want in, from countries like Sweden, Turkey, Thailand and South Korea; oh, and China. They’re traveling to Africa mostly for “humanitarian” reasons. Two of my students at The New School–Lilian Jahani and Senay Imre–have been documenting this on a tumblr blog, Stars Love Africa — started last year.

They document, among others, the exploits of Turkish singer, Seren Serengil (that’s her in the picture above as well in the next picture below), who traveled to Tanzania in 2011. As Senay reminded me, Turkish media dubbed Seren the “Princess in Africa.” She in turn described Tanzania as “300 years behind Turkey,” wanted to adopt a baby, complimented the locals for wearing clothes, and said she was taking her cue from Euro-American celebrities: “Our celebrities generally go to Miami or the Maldives, but American and British rich people go to these places, these are not places that most of our celebrities want to go to.”

Then there’s Taiwanese celebrities Eddie Peng and Amber Kuo, who traveled to Kenya last year to help feed orphans. Amber Kuo was particularly moved by the experience: “I didn’t have a faith, but after returning from Kenya, whenever I have a meal, I would first think about the significance of the food in front of me.”

The Korean singer, Lee Hyori, traveled to Ethiopia on a humanitarian mission:

The Korean version of the Onion had some fun at her expense.

Finally, they also write about the visits by Scandinavian royalty and celebrities to a number of African countries. Read that and more here.

It may be time for Mother Jones to update its Celebrity Map of Africa.

* There’s Jay Z (here, here and here), Chris Brown (and Rihanna) went to Côte d’Ivoire to attend a music awards show (he was very well paid by organizers which angered local bloggers); Brown also went to Ghana where he goaded local police; Bono was in the Sahara; Deakin of Animal Collective went to Mali; Degrassi (!) was in Ghana; so was One Direction (they cried); Erykah Badu went to Kenya; the Real Housewives of Atlanta visited South Africa; Rick Ross went to Nigeria, South Africa and Gabon (Jay Z’s favorite destination); Emma Thompson and her adopted Rwandan son (all color-coordinated) were in Liberia; and Solange Knowles went to Cape Town. Okay my head is about to explode.

My Favorite Photographs N°16: Rui Sérgio Afonso

Born in Huambo but raised in Luanda, Rui Sérgio Afonso is one of my favorite Angolan photographers. The man is prolific on Instagram. After working for Angola’s biggest communications and marketing group, Grupo Executive de Angola (Executive Center), Sérgio is now a freelance photographer. He’s done extensive work with Angolan arts collective Geração 80. Here are his “5 favorite photographs,” in his own words:

Born in Huambo but raised in Luanda, Rui Sérgio Afonso is one of my favorite Angolan photographers. The man is prolific on Instagram. After working for Angola’s biggest communications and marketing group, Grupo Executive de Angola (Executive Center), Sérgio is now a freelance photographer. He’s done extensive work with Angolan arts collective Geração 80. Here are his “5 favorite photographs,” in his own words:

Saying that these are my five favorite photographs would be an injustice to all the others I have taken. Perhaps these five all have different reasons to be included here, like the one above with the children and their improvised sailboats that remind me of the imports that my country is subject to, and that I call “import-export Lebanon China,” the two groups of foreigners that are most common in Angola. The former with their warehouses that supply us with our basic needs such as beans and fuba (ground manioc), and the latter, the new foreigners, that I believe are here to stay, our new colonizers from the Far East.

From the echo the stone makes as it strikes the mabanga (type of shellfish) that sustains the fishermen of this metropolis that grows right in front of your eyes…

…to the relative calm of the fisherman’s boat ready for another day at sea.

From the remnants of humanitarian aid that we are subject to every year, so apparent on the improvised boats of Tômbua village in Namibe…

…to the joy of our children as the rains arrive.

They’re all moments that carry me to my childhood where everything was more fun, more honest, realer — that time where they taught us that socialism was the path to follow for the good of our people, the people that I love so much.

April 21, 2013

Weekend Special, N°1001

1. The fat lady will sing. The New York Times has now featured two West African marriages in its Sunday “Vows” section in a matter of weeks. The first is of a Nigerian wedding (ceremonies in Abuja and Virginia). It’s a union of a very well connected lawyer and an investment banker that makes for, shall we say, interesting copy. Wole Soyinka (who now lives in California, according to the article) is the bride Mojoyin Morolayo Onijala’s maternal grandfather and her father is the state chief of protocol for President Goodluck Jonathan. As for the groom Aderemi Ademola Jacobs, his reasons for marrying his new wife read like a CV: “She was beautiful, very intelligent and well traveled … She brought a different perspective to every one of my conversations.” They also went for 14 months of “premarital counseling” before the wedding. Above is the happy couple.

The second wedding features Ghanaian migrants in New York City. The father of the groom was murdered in 1984 by Ghana’s then-military regime.

2. The writer Taiye Selasi, is on a roll. Her first novel “Ghana Must Go,” just came out and garnering mainstream praise (yes, we will have a review in due course) and she was included in Granta’s list of the “Best of Young British Novelists.” Good for her. She also published, late last month, a piece for the Guardian’s book section on “discovering her pride in her African roots.” Selasi, whose parents are Ghanaian and Nigerian, grew up in Boston and now lives in Rome. In the piece she reminds readers that she sort of invented the term “Afropolitan” (I thought it had been in use before 2005, when she wrote hers). But the piece–a riff on her family history, her therapist and partying in Accra– also illuminates what’s problematic about the whole Afropolitan / ‘Africa Rising” moment. For that I will just excerpt from the comments on her piece:

JJRichardson: Is this satire?

SKMGweme: @JJRichardson – I am really curious. Why do you imagine it is satire?

JJRichardson: @SKMGweme – Because it is everything you would expect from someone satirising a dillettante. designer in the vibrant clothes, a screenwriter in the desert scenes, a poet in the rhythms.

Malaga, Lausanne, Malibu, Yale.

Midnight swims, midnight drag races.

The writing is so bad I thought it may be satire.

You never know these days.

3. I am still trying to get my head around the recent coup in the Central African Republic which replaced one set of looters with another. We’ll promise to find some expertise to wade through unfolding events there. The reporting is sparse in English-speaking media as well as on blogs (last time we covered it was in relation to the documentary “The Ambassador”). One exception has been South Africa where local media rarely reports on matters elsewhere on the continent (everything outside South Africa is still “Africa” for most of its people, including some in its media). Fourteen South African soldiers, in the CAR, there to protect the now deposed president, were murdered by advancing rebels. But South Africa’s media have also not been that helpful. Most of the reporting in South Africa, fueled by anger over the deaths and the failure of the country’s president to convincingly explain why the soldiers were in the CAR, has been on the “local angle” and amounted to sensationalist, unproven, reporting about ruling party business interests in the CAR. That said, there’s been better reporting from the likes of The New York Times, on the motivations and politics of the rebels especially.

4. Anthropologist Ben Magubane, one of a few black scholars in that still mostly white discipline when it comes to South Africa, died last week. Magubane was partly trained by what is now known as the University of Kwazulu-Natal and later at UCLA, where he got his PhD. In this hour-long interview with Magubane (by Cape Town historian Sean Field), he recalls his impoverished childhood in and around Durban, the racism of post-war South Africa, his initial university studies, scholarship to the United States (which also meant exile), activism against Apartheid (including taking part in a well publicized consumer boycott) and work and life at the University of Zambia (where he was close to OR Tambo and Jack Simons. Magubane returned to South Africa in 1994. His research legacy includes his pioneering critique of the supposed radicalism of the “Manchester School” of anthropology (since reprised by James Ferguson), a book on race and class in Apartheid South Africa in 1979 (a critique of neo-Marxist interpretations of the South African “question” at the time), and edited a series of volumes on “The Road to Democracy in South Africa.”

5. Striking present day (from this year) image of District 6, the Cape Town neighborhood razed by the Apartheid state in the late 1960s in its efforts to move the city’s black, mainly coloured, residents from the city center. Much of it still stands empty. It was taken by Barry Christianson, who describes himself as a “mostly street photographer.”

6. From the archives: Vanity Fair’s 2007 photograph of South African activist Zackie Achmat and his dog Socrates on the beach in Cape Town (photo by Jonas Karlsson):

7. I want to include at least one goal (from football that is) in this weekly post: This week, one by the Nigerian national team member, Nosa Igiebor, who has had an unhappy spell (especially the fans) at his Spanish club, Real Betis, and who does not celebrate his goals in the usual way. This was in the 90th minute in a local derby against Sevilla with the score 2-3 in Sevilla’s favor.

The Guardian’s Sid Lowe explains why:

Racing behind the goal, the Nigerian celebrated his first and probably his last ever goal for Betis. A dramatic late equaliser in the biggest game in the city, one of the biggest in Spain. They’d waited a long time for him and he’d waited a long time for this. Running to the home fans, he raised both index fingers and let out a shout that summed it up:

“Fuck you!”

Elliot suggested filing it either under “Great African football meltdowns.” The other main contender: Didier Zokora’s kicking racism or Turkish player Emre’s testicles out of football. Alternatively file under “Great Angry Goal Celebrations.” Others: Marco Tardelli in Spain 82 and Temuri Ketsbaia for Newcastle (he ripped off his shirt and started furiously kicking an advertising hoarding).

9. The New York Times story of the US government drug smuggling sting that snared a former admiral in Guinea Bissau’s army, which included this odd reaction from the government in Bissau:

The arrest of the former admiral appears to have shocked the authorities in the capital, Bissau. Last week, they dismissed the country’s top intelligence official, apparently for failing to spot the American operation unfolding under their noses over months.

10. Finally, I watched the new “Venus and Serena” documentary on iTunes. The film, which ambles on in parts (and includes some odd sightings: Anna Wintour telling us obvious things), is quite good in exposing the racism among tennis “fans” and the journalists covering the sport, especially against the Williams sisters and their dad, for whom, despite his personal foibles, I still have lots of respect. Here’s the trailer:

* H/T to Elliot Ross, Tom Devriendt and Derica Shields. Read last Sunday’s Weekend Special here.

April 20, 2013

Empress of East Africa, Bi Kidude RIP

It was 2011 and we were preparing for TEDxDar. Behind schedule as always, we needed to get Bi Kidude, this iconic figure on our stage. We wanted to hear her voice and her story in an intimate way. We wanted to experience her magical presence, her Diva, on the small stage, away from the large international concerts and festivals such as Sauti za Busara where we had become accustomed to seeing her. Was she still alive we asked ourselves, for it seemed every four weeks in the previous four years there was at least one rumor of her passing. How would we even get in touch with such a legend? This authority of culture must surely be hard to find – but find her we did.

It was 2011 and we were preparing for TEDxDar. Behind schedule as always, we needed to get Bi Kidude, this iconic figure on our stage. We wanted to hear her voice and her story in an intimate way. We wanted to experience her magical presence, her Diva, on the small stage, away from the large international concerts and festivals such as Sauti za Busara where we had become accustomed to seeing her. Was she still alive we asked ourselves, for it seemed every four weeks in the previous four years there was at least one rumor of her passing. How would we even get in touch with such a legend? This authority of culture must surely be hard to find – but find her we did.

We released some fillers and finally managed to get a hold of her manager, one of her nephews at the time. And we managed to book for this icon, set to arrive in Dar es Salaam from Zanzibar. Having organized with her nephew manager, we were skeptical that the iconic Bi Kidude would be so accessible. But we realized this reality as she arrived with more spice than could be filled on an Island. Arriving at the docks of Dar es Salaam by boat, our posse went to welcome the Empress of East Africa to Dar es Salaam.

Her handshake, firm, hid all other appearances of age. “How was your boat ride to Dar es Salaam?” we asked her. In a charming way, she seemed to have misinterpreted the question. “Ahh mimi bara lizima nimeshalizunguka miguu peku…” (“Ahh I have circled the whole mainland barefoot!”) She went on a diatribe about how this was not her first time on the mainland, she had in fact circled it barefoot three times before we were even born… She was liberating ears before TANU had even brought independence. Perhaps she understood the question exactly, but her discernment was to educate beyond small talk. DIVA.

Her handshake, firm, hid all other appearances of age. “How was your boat ride to Dar es Salaam?” we asked her. In a charming way, she seemed to have misinterpreted the question. “Ahh mimi bara lizima nimeshalizunguka miguu peku…” (“Ahh I have circled the whole mainland barefoot!”) She went on a diatribe about how this was not her first time on the mainland, she had in fact circled it barefoot three times before we were even born… She was liberating ears before TANU had even brought independence. Perhaps she understood the question exactly, but her discernment was to educate beyond small talk. DIVA.

“Tomorrow we will need you at the National Museum and House of Culture where our event is being held. We will pick you up for rehearsals.” She agreed to come and see the venue, but rehearse she would not: “Do I look like I need rehearsal?” her gaze seemed to say.

She was sitting outside the Museum veranda on event day, burning through her classical pack of Embassy cigarettes, we sat in wait – anxious. When the bell struck, she was on stage, our closing act. And close she did.

Image by Hellen Rosiah Marie

Bi Kidude is beyond a cultural icon, a national figure, an orator, a historian, a legend, her humility, her statuesque authority transcends a legacy like no other. Her loss is a great one to Tanzania and the world over though we shall not mourn but celebrate her excellency. Rest in Power, Great Empress.

***

Here are some videos to remember her by. Below is Bi Kidude in a drum circle beating the drum with her dancers in a ubiquitous dance style of going round in a mduara (circle) and gyrating:

In “Kijiti” Bi Kidude speaks of rape; since there are subtitles you can see her wizardy skills of composing, storytelling. Kijiti returns the defiled girl deceased, this could be spiritually or physically:

Bi Kidude sings one of her classics, “Muhogo Wa Jang’ombe”, where she explores themes of sex and midwifery:

And finally, “Alaminadura” (Ar. “the Universe is Round”). In Swahili there is the similar proverb “Dunia duara” (the world is round): you will come back to the starting point:

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers