Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 471

May 18, 2013

Weekend Music Break

Gata Misteriosa and Lee Bass (the Mozambican-Portuguese-Ghanaian-German duo who go by the name of Gato Preto) dropped this new video for “Pirao” last night: no longer strictly kuduro, not yet sure what to call it, but right in time for our weekend special of ten. Video above. Janka and the Bubu Gang (Sierro Leone via Brooklyn) also surprised with this belated video for “Feba”, lifted from their 2012 record “En Yay Sah” out on Luaka Bop:

NPR did a nice feature on Jeri-Jeri recently, the collaboration between the Senegalese Bakane Seck-led drum collective and German producer Mark Ernestus, and premiered their new video, “Gawlo”, featuring Baaba Maal (below). Remember Jeri-Jeri. But there’s more. They’ve been uploading some other studio material onto their YouTube channel as well. Here.

Navio and Unique lay down their rhymes over “1960′s Ugandan beats” on “Leka Kwenyumiriza”.

More conscious Hip-Hop: Senegalese rap group A-J One (feat. Xuman and Ceepee) on “Ndjite” (there’s so much rap coming out of Dakar recently it’s hard to keep up; we’ll write about it shortly):

When Maître Gims (real name: Gandhi Djuna) isn’t collaborating with Sexion d’Assaut or his dad (Franco band singer Djanana Djuna) he’s putting out records by himself. This is from his latest: “VQ2PQ”:

Recorded in Bamako, Mali, in September 2012, ‘Troubles’ is the new album from Dirtmusic, the band headed by Chris Eckman (The Walkabouts) and Hugo Race (Fatalists/True Spirit/Bad Seeds), featuring musicians Ben Zabo, Samba Touré and Zoumana Tereta amongst others. Here’s “Fitzcarraldo”:

Aline Frazão also has a new record out (hoping Claudio might have time to review it soon). Here’s the first single, “Tanto”, with a lovely video:

Omar’s “The Man”, taken from his forthcoming album of the same name (where has he been all those years?):

And finally, Charles Bradley, who we can listen to any day. Live @ KUTX:

H/Ts this week: Zachary, Sean, Ts’eliso and Claudio.

The Cartography of Bullshit

With the gutting of foreign coverage by most U.S. newspapers and the need to populate infinite Web space with content, a new creature has emerged: the foreign affairs blogger. Max Fisher, who hosts the Washington Post’s WorldViews page, is a leading exemplar of the species. Fisher’s newsy nuggets are often low-priority zeitgeist items that may or may not be vignettes of greater themes: examples in recent days include the tunnel-smuggled delivery of KFC chicken into Gaza, the video of the Czech president possibly drunk, a staff-passenger brawl at Beijing airport, and New Zealand’s “war on cats.” Fisher also concocts FAQ-style explainers on places in the news that he judges to be obscure to his readers (Chechnya and Dagestan, Central African Republic, Mali). And he is very keen on global surveys, whose results he summarizes, augments with his own interpretation, and typically renders with color-coded maps that drive home the key message.

This week, Fisher proposed to his readers what he titled “A fascinating map of the world’s most and least racially tolerant countries.” The deep-blue, racially tolerant areas included the US, UK, Canada, Australia, Scandinavia, and much of Latin America. The deepest-red, or most racially intolerant, countries were India, Bangladesh and Jordan. Russia and China fell in the middle; much of Africa was left out for lack of data, but South Africa came out light blue (highly tolerant), and Nigeria light red (highly intolerant). Other highly tolerant countries included Pakistan and Belarus.

A cursory glance at this distribution of results would suggest something deeply suspect about the exercise; moreover, anyone who studies the concept of race knows that it is hard enough to operationalize in a single-country context, let alone in cross-national comparison. Still, Fisher soldiered on, offering bullet-point findings: “Anglo and Latin countries most tolerant,” “Wide, interesting variation across Europe,” “The Middle East not so tolerant,” and the like. He offered country-level speculation: tolerance was low in Indonesia and the Philippines “where many racial groups often jockey for influence and have complicated histories with one another,” and lower in the Dominican Republic than in other Latin countries “perhaps because of its adjacency to troubled Haiti.”

Where did these numbers come from? As Fisher explained, they came from the long-running World Values Survey, which has polled attitudes around the world for decades. Fisher was drawn to the topic by news of a new paper, by a pair of Swedish economists, on the links between economic freedom in a country and its level of tolerance. (The paper was described in a post at Foreign Policy, itself a hub of foreign-affairs blogging.) To measure racial tolerance in particular, the authors used question A124_02 in the World Values survey, which asks respondents whether they would “not like to have as neighbors people of another race.” Intrigued, Fisher went back to the survey itself and, as he put it, “compiled the original data and mapped it out in the infographic” that led his post.

Although the results don’t pass the sniff test in the first place, I took a look at the data as well, in an effort to identify the exact problems at play. It turns out that the entire exercise is a methodological disaster, with problems in the survey question premise and operationalization, its use by the Swedish economists and by Fisher, and, as an inevitable result, in Fisher’s additional interpretations. The two caveats that Fisher offered in his post – first, that survey respondents might be lying about their racial views, and second, that the survey data are from different years, depending on the country – only scratch the surface of what is basically a crime against social science perpetrated in broad daylight. They certainly weren’t enough to stop Fisher from compiling and posting his map, even though its analytic base is so weak as to render its message fraudulent.

For one thing, the values for each country are indeed from different years, some in the past decade, others as old as 1990. As Fisher put it coyly, “we’re assuming the results are static, which might not be the case.” Indeed: by a rigorous methodological standard, this would be enough to throw out the cross-country comparison in the first place.

Second, a visit to some of the other tolerance questions in the A124 series reveals absurd results and design idiosyncrasies that should render the results of question A124_02, on race, suspect. The other questions ask respondents if they would accept a neighbor who had various other traits: homosexuality, a different religion, heavy drinking, emotional instability, a criminal record, and so on.

To take an example of the weakness of the data, it would appear that in Iran in 2000, only 0.9 percent of respondents “mentioned” an objection to having a homosexual neighbor, whereas in 2007, 92.4 percent mentioned it. In Pakistan in 2001, according to the survey, 100 percent of respondents “did not mention” objection to a homosexual neighbor. These are obviously particularly buggy examples, but these are the data points that the survey offers for analysts to work from; readers can visit the database to form their own opinion.

Moreover, the menu of traits available in the survey for respondents to tolerate or not tolerate varied by country. Thus, Iranians were asked about Zoroastrians; Puerto Ricans, about Spiritists; Tanzanians, about witchdoctors; Peruvians, inexplicably, about “Jews, Arabs, Asians, gypsies, etc.” (A124_33). In other words, the question about race was presented as part of a different menu of questions depending on the country, another red flag signaling a need for caution in isolating it and using it to produce grand findings. And further issues abound: as Fisher noted, self-reporting of prejudice is unreliable to begin with; as the scholar Steve Saideman pointed out, the “neighbor” question is not the best measure of tolerance; and so on.

But the biggest problem, of course, is that “race” is impossible to operationalize in a cross-national comparison. Whereas a homosexual, or an Evangelical Christian, or a heavy drinker, or a person with a criminal record, means more or less the same thing country to country, a person being of “another race” depends on constructs that vary widely, in both nature and level of perceived importance, country to country, and indeed, person to person. In other words, out of all of the many traits of difference for which the WVS surveyed respondents’ tolerance, the Swedish economists – and Fisher, in their wake – managed to select for comparison the single most useless one.

Fisher has an active social-media presence and his posts circulate quite broadly among international-affairs geeks and journalists in many countries; this one found the usual echo on the networks, plus a fair amount of skepticism. In India and Pakistan, Twitter readers were shocked by India’s ultra-high and Pakistan’s ultra-low racial intolerance ratings, both on their own merits and in comparison to each other. Lakshmi Chaudhry and Sandip Roy, at India’s Firstpost, wrote a detailed objection. (Less productively, Philip Weiss at Mondoweiss objected that Fisher’s map excluded Israel, implying that this deliberately overlooked racism in Israel – a spurious accusation, since there are no data available for Israel for question A124_02 in the WVS in the first place.)

On Twitter, Fisher engaged with Saideman but brushed off other queries, tweeting archly: “Coincidentally, readers from red countries are much more likely to say they doubt the methodology behind this study.” When I raised many of the issues in this post, he offered no response or acknowledgment at all, except to block me on Twitter. (That’s why I’m not bothering to seek comment from him before running this piece.) He summarized a few of Saideman’s objections in a follow-up post, but much of this goes down the rabbit-hole of political-science arcana about ethnic conflict and, for some reason, the specific case of Somalia. A more intellectually honest move would have been to take down the map and explain to readers why the exercise was doomed from the start.

Instead, we are left with a shiny color-coded “fascinating map” on the Washington Post site that sends a strong message of Western, Anglo-Saxon moral superiority, assorted with a mystifying portrayal of the rest of the world, and accompanied by near-gibberish interpretations – all based on a methodological process that fails pretty much every standard of social-science design and data hygiene. In other words, pseudo-analysis that ends up, whether by design or by accident, playing into an ideological agenda.

But the problem here isn’t the “finding” that the Anglo-Saxon West is more tolerant. The problem is the pseudo-analysis. The specialty of foreign-affairs blogging is explaining to a supposedly uninformed public the complexities of the outside world. Because blogging isn’t reporting, nor is it subject to much editing (let alone peer review), posts like Fisher’s are particularly vulnerable to their author’s blind spots and risk endogenizing, instead of detecting and flushing out, the bullshit in their source material. What is presented as education is very likely to turn out, in reality, obfuscation.

This is an endemic problem across the massive middlebrow “Ideas” industry that has overwhelmed the Internet, taking over from more expensive activities like research and reporting. In that respect, Fisher’s work is a symptom, not a cause. But in his position as a much-read commentator at the Washington Post, claiming to decipher world events through authoritative-looking tools like maps and explainers (his vacuous Central African Republic explainer was a classic of non-information verging on false information, but that’s a discussion for another time), he contributes more than his weight to the making of the conventional wisdom. As such, it would be welcome and useful if he held himself to a high standard of analysis – or at least, social-science basics. Failing that, he’s just another charlatan peddling gee-whiz insights to a readership that’s not as dumb as he thinks.

May 16, 2013

How to Please Your Man “Zambia Style”

Imagine you’re a 17 year old middle class Dutch girl. You just cycled home from another boring day at school. Trapped in the conventional humdrum of the day, you are deprived of the stirring type of high school tales that you often watch. Back home, you switch on the TV and stumble upon a rerun of Spuiten en Slikken (“Shoot and Swallow”), a sex and drugs focused talk show that broadcasts sexual experiments every week. You don’t feel like it, though. You can always watch the episode online later. (This shouldn’t be too much of a problem with a national internet accessibility rate of nearly 90%.) You decide to call your friend and see what she has been up to. When you pick up your smart phone (a device that 80% of your peers have) her Whatsapp message just pops through, “My mum is dropping me off at my boyfriend’s place now, will call you tomorrow”. You can’t help feeling somewhat begrudged. Even though you are allowed to regularly sleep over at a boyfriend’s place, as is 2/3 of your peers, and your mum put you on birth control ever since you got your first period, you haven’t found your ideal sex partner yet. But God knows you’re ready for it. Thanks to the endless chat sessions with online sexual experts and youth forums, you know exactly what to expect, how to react and when to retract. Nevertheless, still unsure and unsatisfied with the wealth of information available at the click of a mouse, where on earth do you go? Dutch documentary maker Kim Brand has you covered: Zambia.

In her latest film, ‘Onder Vrouwen’ (“Among Women”, click to watch it), Brand travels to rural Zambia to find out what “liberated, spoiled, but also insecure” Western women can learn from their African counterparts. By participating in rituals, she hopes to answer those types of sex and relationship questions that have puzzled her for years. How to please a man without losing yourself? How to build a long-term relationship and simultaneously keep the sexcitement at an acceptably exhilarating echelon?

She admires the high degree of practicality in the love lessons that the young Zambian girls get from their ‘aunties’ as preparation for adulthood. It makes her realize that in the ‘Free West’ (her inverted commas) you basically have to find it out all by yourself. But in Zambia, “she is part of a world of rituals, intimacy and guidance of a woman’s group who support each other whenever they need to”. This kind of female trust circle, the life lessons and most importantly the love lessons are exactly what she so fervently misses in the Netherlands. She takes home several Zambian lessons, such as how to move her hips to optimally satisfy a man and how to clap her hands as a sign of gratitude after the deed.

The documentary is not the first manifestation of the centuries-old Dutch fascination with black sexuality (most recently, a casting agency put out a call for “white girls who are exclusively into black men” for a new reality show).

It doesn’t matter whether it’s existential confusion, employment fatigue, stress or sexual frustration. No matter how out-of-sync and contextually detached it gets, to Dutch twenty-somethings, there’s an African solution for every Dutch puzzle.

5 New Films to Watch Out For, N°27

An Oversimplification of Her Beauty is the creative debut feature of director Terence Nance who we got to know through the work he did together with Blitz the Ambassador. His new film is sold as a take on “young love” in the city of New York. First reviews praise, among other things, the mesh of visual styles:

Below’s the pilot video for King Khama: The African Abe Lincoln (assuming the second part of the tile is provisional), a proposed animated movie about Botswana’s King Khama III. Know your history. The project’s website has more details (including excerpts of the script).

The Forgotten Kingdom is a long feature written and directed by Andrew Mudge. The Examiner has an interview with him about the genesis of the film — we learn the production crew was small, “made up mostly of interns from within the country with no film experience”, starring a cast of Basotho and South African actors — and a first favorable review. Predictably, debates broke out on the film’s Facebook wall after the release of the trailer over whether this is “the first film to come out of Lesotho” (the line they’re promoting it with), “a Lesotho film,” or “a South African film”. We won’t wade in. No news yet on when it will be showing in Maseru’s cinemas:

Tik & the Turkey is a one-hour documentary, currently in post-production, depicting the heroin and methamphetamine (also known as “tik”) problem in Cape Town, South Africa and the devastating effects it has on the people and the communities. Some perspective of the story’s urgency: a recent report suggested “1 in 5″ (stats depend on who you ask) of school-going youth in the Cape flats are actively using tik.

Ali Blue Eyes is a film by Claudio Giovannesi about an Italian teen of Egyptian heritage (lead role for Nader Sarhan) caught between his conflicting identities. Variety‘s review is onto something when the author remarks that while “(a) young man trying to balance his roots with his environment has long been a familiar figure in cinema, the subject is of more recent vintage in Italy, which has only recently begun coming to grips with an immigrant population.”

May 15, 2013

Football Referee of the Year

My knowledge of European club football doesn’t stretch much further beyond what gets posted here on Football is a Country and the odd link I come across on our Twitter feed (blame my wary interest on the historical underperformance of Belgian teams* and a time-consuming preference for all things music) so I was surprised to read Gabonese referee Jérôme Efong Nzolo was voted Referee of the Year by Belgian football players in this year’s Jupiler Pro League (that’s Belgium’s national competition). Nzolo was born in Bitam in 1974, came to Belgium to study for electromechanical engineer back in 1995, worked for some years in a car factory, later became a teacher and started refereeing in the national competition in 2000. National TV put the spotlight on him during his first top match some years ago. This year’s election as referee of the year isn’t his first time: he previously won in 2007, 2008 and 2009. Is the presence of referees of African descent still as rare in professional European club football as I believe it is, or should I read the footy pages more?

* This, no doubt, will change when the Belgian Red Devils manage to qualify for Brazil 2014 and go on to win the World Cup. That’s how it goes.

May 14, 2013

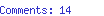

Does Karim Wade’s arrest mean “the time when one could pillage public goods is gone” in Senegal?

Karim Wade, the son of octogenarian ex-president Abdoulaye Wade, has been sitting in a central Dakar prison for nearly a month as he awaits trial for corruption charges. The younger Wade was arrested and formally charged with illicit enrichment after an investigation revealed that he amassed $1.4 billion in personal wealth.

During his father’s presidency from 2000-2012, Karim Wade held a number of posts including Minister of Infrastructure, International Cooperation, Energy and Air Transportation. As “the Minister of Earth and Sky” as he was popularly known, he was reportedly responsible for a total budget of one-third of state expenditure via Senegal’s largest infrastructure projects. Prosecutors have accused Karim of having stakes in large sectors of the economy including firms managing Dakar’s port and airports. The investigation also links Wade to a complex web of off-shore accounts located in Panama, the British Virgin Islands and Luxemburg. Wade’s lawyers have denied the charges against him and claim they can prove his wealth was legally obtained.

Interviews with people on the ground indicate that the majority of the population believes this is a good move for new president Macky Sall who pledged to crackdown on corruption and increase transparency. For a small number of people, however, the arrest represents a political “witch hunt” against former ruling Senegalese Democratic Party (PDS) on the part of the current government. Does Wade’s arrest mean that “the age of impunity is over” and “the time when one could pillage public goods is gone” as stated by Senegal’s Justice Minister, Aminata Touré or will this arrest encourage politicians to remain in office because they fear prosecution? Where should public officials accused of fraud and corruption be brought to trial, at the International Criminal Court (ICC), regional bodies such as Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) or neighboring countries?

May 13, 2013

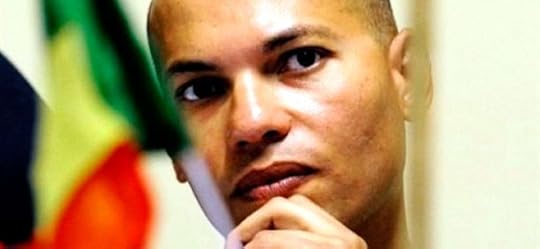

Aristide Zolberg and African Studies

In a 2010 interview, Aristide Zolberg—the pioneer Africanist political scientist who died on April 12 at the age of 81—described his early interest in the politics of a continent in the first throes of independence: “India was a beacon of the future, and of the triumph of the powerless over the powerful. Africa, and in particular French West Africa, where decolonization was already in progress, was India on the horizon. African decolonization was also tied to the United States, where the study of Africa signaled solidarity with nascent civil rights movement … studying Africa was not about choosing a case; it was about making a normative statement of solidarity and resistance, and of the triumph over imperialism.” Zolberg’s remarks do more than conjure a fleeting moment of post-colonial optimism. They recall an unrealized program for African studies.

Decolonization appears here as a global project: less about individual states than the future organization of resources and power on a planetary scale, and its possibilities appear most clearly through the prism of an Afro-Asian political dynamic. This radical break demands new forms of knowledge, which are also implicated in a transnational politics of racism, diaspora, and struggle. Most crucially, such knowledge defies the circumscriptions of area studies. It’s predicated on solidarity rather than objectivity. It transects the conceptual schism between the First and Third worlds. It requires a mode of theory that respects multiplicity and historical conjuncture. Africa, Zolberg suggests, is neither a case nor country, but a demand for new ways of thinking about the future.

Among scholars of sub-Saharan Africa, Zolberg will be remembered primarily for two ground breaking books on West Africa politics, One Party Government in the Ivory Coast (1964) and Creating Political Order (1966). It’s not just that these works remain engaging and thought-provoking almost half a century after their publication—no small feat as several schools of African political science have swelled and crashed in their wake. It’s that Zolberg’s scholarship combines an effort to analyze African political parties in universal terms (that is, as politics, confronting some of the same dilemmas as mass movements or machine politicians anywhere) with deep suspicion towards the universalizing theories of 1960s social science and their pseudo-biological notion of development. He was a scholar of politics in West Africa, eschewing the single concept, magic bullet explanations of “African politics” that would mar even some of the best research of later decades. The African regimes of the early 1960s varied enormously in colonial background, political structure, and ideology. Zolberg understood that it was their commonalities—especially the emergence of the single party state and the salience of ethnic politics—that required explanation. And explanation required exhaustive field research and comparative analysis.

His early life informed this intellectual trajectory. He was born and raised in a Belgium divided between French and Flemish speakers in a 19th century episode of imperial state building. His parents were Polish Jews who assimilated into the French-speaking, and staunchly secular, middle class. As a result, his childhood fed an awareness of the complex disjunctions between nation, language, ethnicity, and religion. He survived the Second World War by living as a Catholic School boy under the name of Henri Van den Berg, and, for a period of time, accepted the faith as his own. His father died in Auschwitz; his mother escaped to the United States. At the age of 16, Zolberg moved to Brooklyn, where he finished high school while living with Orthodox relatives. The new environment was an uneasy fit. Disjunction once again. If Zolberg later wrote in the crisp voice of a political scientist, the questions of migration, racial violence, and ethnicity were near indeed. He planned to entitle his unfinished memoir on the war years Games of Identity.

Within a year of moving to the United States, Zolberg finished high school and began studying at Columbia University, where he wrote extensively for the Columbia Daily Spectator and learned how to interview. Like many immigrants of his generation, he viewed university as the gateway to the professions and began his studies in pre-law. In short order, he grew frustrated with institutional approaches to government that floated above the realities of American racism and inequality. For his first major research paper, Zolberg interviewed the Moroccan Istiqlal delegation when it visited New York to argue against the French mandate at the United Nations. Family again fed into his interests. Zolberg’s uncle, a Communist who had been imprisoned in Algeria, had introduced the young man to the literature chronicling North Africa’s struggle for independence. Romance was also at work. At Columbia, Zolberg met his future wife Vera, and declared that he planned to work on West Africa as a courtship gambit. Vera, who studied French and later earned a MA in African Studies as well as a PhD in Sociology, was thrilled by the idea.

Within a year of moving to the United States, Zolberg finished high school and began studying at Columbia University, where he wrote extensively for the Columbia Daily Spectator and learned how to interview. Like many immigrants of his generation, he viewed university as the gateway to the professions and began his studies in pre-law. In short order, he grew frustrated with institutional approaches to government that floated above the realities of American racism and inequality. For his first major research paper, Zolberg interviewed the Moroccan Istiqlal delegation when it visited New York to argue against the French mandate at the United Nations. Family again fed into his interests. Zolberg’s uncle, a Communist who had been imprisoned in Algeria, had introduced the young man to the literature chronicling North Africa’s struggle for independence. Romance was also at work. At Columbia, Zolberg met his future wife Vera, and declared that he planned to work on West Africa as a courtship gambit. Vera, who studied French and later earned a MA in African Studies as well as a PhD in Sociology, was thrilled by the idea.

After beginning a program in African Studies at Boston University, Zolberg was drafted in 1955 and served in Dixie during the period of the U.S. military’s racial integration. Afterwards, he moved to Chicago to pursue a PhD under the aegis of the newly formed Committee for the Study of New Nations. Zolberg’s supervisor, David Apter, suggested that he pursue a dissertation on the Ivory Coast—by his own admission, Zolberg had never heard of the country–and he departed with Vera in 1958 to live above a Lebanese grocery in Abidjan. On the way to the Ivory Coast, they spent several months in Paris waiting for a visa and passed part of their time hanging out at the legendary publishing house Présence Africaine. Before the Houphouët-Boigny government declined to renew their visas, Zolberg managed to interview every current and past member of the Territorial Assembly and scoured the debates in the assembly in the run-up to decolonization.

This research would later form the basis of basis of Zolberg’s first book, the classic One Party Government in the Ivory Coast. Focused on the problem of national integration, the work provided one of the first analyses of ethnicity in post-colonial Africa politics, but it did so through the remarkably prosaic comparison of the Ivorian government and the Mayor Richard Daley’s machine politics in Chicago. Zolberg set aside both the left’s Marxist orthodoxies and the right’s Weberian dichotomies in order to provide an elucidation of the actual challenges Houphouët-Boigny faced in consolidating power and governing. The polemical dimension of this argument was largely implicit, but nonetheless remarkable. The domain of politics, he demonstrated, only became visible after breaking free from universalizing schemas of development and modernization.

Zolberg expanded these arguments in his second book, Creating Political Order, a comparison of the regimes and ruling ideologies of five African countries (Ivory Coast, Mali, Ghana, Guinea, and Senegal). Documenting the process by which the ideology of the party-state emerges in West Africa, Zolberg unraveled how anticolonial nationalist movements—often fragile, heterogeneous blocs of local and regional interests—assumed power over highly differentiated societies and then presented themselves as the one unifying element of nations in the process of becoming. As a result, the party, nation, and state became fused in the person and ideology of the post-colonial ruler. Opposition, especially regional or ethnically-based, was therefore antinational and served the machinations of imperialism. Ironically, the reality behind the totalitarian façade was a weak state with quite limited reach and capacity: its unstable power rested largely on symbols of rationality and control. Creating Political Order underlined the failures of transporting normative (that is, Eurocentric) concepts of state, society, and democracy to West Africa, and urged greater attention to micro-politics and the popular culture surrounding government. At the same time, it forcefully challenged a generation of Western and African thinkers who concluded that Africa’s “underdevelopment” necessitated state authoritarianism. False particularisms, he suggested, could easily be as dangerous—and racist—as a self-serving universalism.

Other tributes have noted Zolberg’s important scholarship in the field of migration studies, his long and industrious teaching career at Chicago and the New School, and his generosity as mentor and colleague. For us, his death is an important reminder of the radical visions that challenged area and development studies from their inception, and the range of personal, intellectual, and political experiences that animated some of the earliest research on African politics in the U.S.

This piece draws on the special issue of Social Research dedicated to Zolberg, especially the wonderful interview with Zolberg by Courtney Jung. My thanks to Bill Freund and Marty Klein for sharing their reflections on Zolberg’s life and work.

Did Britain’s MI6 have Patrice Lumumba murdered?

Guest Post by Harry Stopes

Africa is a Country readers may not regularly check the London Review of Books, a British literary magazine with a circulation just over 50,000–it’s meant more for Bloomsbury than Bamako or Bloemfontein (though some readers could probably find it in Brooklyn; it’s online too with a subscription)–but the magazine has a pretty good, though not blameless (worst offender RW Johnson) record of writing on Africa. On the good side, frequent contributor Bernard Porter has written about the continent several times, in particular on the Mau Mau insurgency, advancing an interpretation of events that seems increasingly likely to be proven correct. And occasionally the LRB breaks news. Towards the end of March, Porter reviewed Calder Walton’s book on the British security services, the Cold War, and the end of Empire. Porter mentioned in passing that Howard Smith, then an official in the British Foreign Office and later head of MI5, had advocated killing Patrice Lumumba as one of a number of possible “solutions” to the problems he seemed to pose to Western governments and corporations.

Porter seems to share Walton’s feeling that while we may never know whether such suggestions came to anything, British agents–and politicians–were much less ignorant (or innocent) of European colonial and post-colonial crimes than the British public fondly imagine.

Two weeks later, in the next issue of the LRB, a letter from David Lea, a member of the British House of Lords, purported to shed more light on British involvement in Lumumba’s death:

I was having a cup of tea with Daphne Park–we were colleagues from opposite sides of the Lords–a few months before she died in March 2010. She had been consul and first secretary in Leopoldville, now Kinshasa, from 1959 to 1961, which in practice (this was subsequently acknowledged) meant head of MI6 there. I mentioned the uproar surrounding Lumumba’s abduction and murder, and recalled the theory that MI6 might have had something to do with it. ‘We did,’ she replied, ‘I organised it.’

The LRB reaches a specialist audience but their best stories have the capacity to shape comment and op-ed agendas in the British media. A few days after the letter appeared I was listening to BBC Radio 4 in the early morning and heard their security correspondent discussing Lea’s letter. Did we do it? the presenter asked. The correspondent thought it was unlikely that MI6 played the decisive role but pointed out that Park was close to one of Lumumba’s Congolese rivals. Coverage in the newspapers tended to divide along political lines. The right wing Daily Telegraph thought it was all nonsense because “Britain does not conduct assassinations in peacetime”, while the Guardian was more circumspect. More surprisingly, later that week I was eating breakfast in a ‘greasy spoon’–a workman’s cafe–in south London reading a copy of the tabloid newspaper The Daily Mirror. On the inside pages a small news in brief item reported Lea’s letter in passing. Did we do it? Dunno but it’s a funny story eh?

The British government is right now negotiating possible compensation for Kenyan torture victims. Their torture was probably documented in files that were deliberately destroyed. Other files were deliberately hidden away from the main Foreign Office archives. All this has been revealed in just the last couple of years and yet the recent discussion of Lumumba in the mainstream media has been conducted in such a calm, detached, almost aloof tone–as if the question of British involvement in Lumumba’s assassination is only of passing, academic interest. It’s indicative of continuing British amnesia towards its colonial and post-colonial past in Africa and elsewhere. Still though, that story may not be over. As a letter in the latest issue of the LRB points out, Lea may have more to tell us. It’s hard to imagine his conversation with Daphne Park stopped there.

* Harry Stopes is a PhD student and teaching assistant at London’s Global University’s Department of History. Follow him on Twitter.

May 11, 2013

Weekend Music Break

Many collaborations and surprise comebacks popped up in our feeds this week. First, this one by Kenyans DNA and Tanzania’s Mr. Nice, who tried his luck in South Africa for a while but now seems to have found his ground again back home:

A Swedish-South African collaboration between Kwaai, Driemanskap, Syster Sol, Mofeta, Kristin Amparo, Cleo and Kanyi. Video by (photographer) Luke Daniel and Neil Wigardt:

Also shot in the Cape flats: this video for Pharoahe Monch in Mitchell’s Plain:

Still based in Brussels these days, Badi (Banx) returned from the DRC with a clip recorded at Nzonga Falls for “Losambo” (part of his ongoing Kin Transit video series):

An American-South African Hip-Hop collaboration between HHP, Omar Hunter El, Asheru, Benn Chad, OneTwo, Projector, Zubz, Cassper Nyovest, Nomadic, Element Lehipi Khalil on “Animals”:

Two new videos for Pan-American Los Rakas’ short “Mi Pais” (which has Raka Dun expressing his American dreams and struggles before joining Raka Rich in the studio — head over to YouTube for full English translations) and “No Tan Listo”:

There’s a new single and video for Coely, who’s mostly filling Belgian clubs at the moment, but we can see that changing soon:

Johannesburg producer Alkabulans’ instrumental “Cross-Dimensional Symmetry”. Trust South African Iapetus Records to surprise us:

London combo Anthony Joseph and his Spasm Band recorded this video in Berlin for “Started off as a dancer”:

And since it’s been a while we included some Cabo Verde music here: old master Zé Luis performing “Ku Nha Kin Bem”:

May 10, 2013

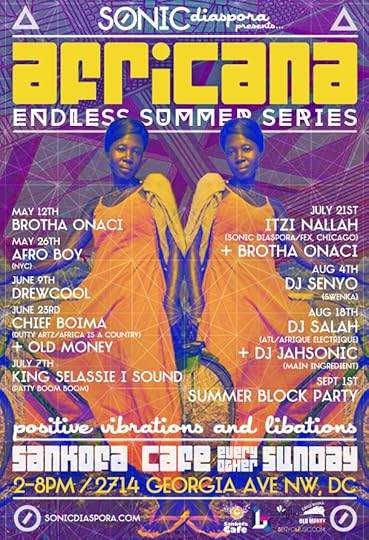

Africana Endless Summer Series in Washington, DC

It’s starting to get sticky in Washington DC and that means it’s time for music to migrate from the nightclub to the street. To bring people together in the name of celebrating African music and dance from across the continent and the Diaspora, Beshou Gedamu, organizer of DC’s Sonic Diaspora music parties, devised the Africana Endless Summer series. The series, which kicks off this Sunday, May 12th, is a biweekly coalescing of sonic souls that features some incredible DJs, including AIAC’s own Chief Boima. We asked Beshou to tell us about the new event and the state of the African dance music scene in DC:

Pitch us the Africana Endless Summer Series?

Beshou: Imagine walking into a someone’s backyard, feeling liked you’ve been transported to the beaches of Cote d’Ivoire, rum punch in hand and being “sonically surprised”. That’s Africana Endless Summer Series.

What was the inspiration for this event?

Every year, I find myself wanting to travel outside of DC to neighboring cities to fulfill my summer experience. I’ve always wanted to organize some sort of block party in DC where people from various backgrounds can connect and listen to some really good music. Sankofa Books and Cafe approached me to do Sonic Diaspora events and that’s how this event was born. We’ve received an overwhelming amount of support and I’m excited for Africana Endless Summer Series.

What is unique about the African dance music scene in DC?

I find it to be fascinating and complex. The complexity lies in the fact that there are African parties happening right under your nose in very well known establishments and you may not know about them. Most of them cater to their respective communities (i.e. East or West Africans). The fascinating part is when you walk into one of those events, it’s a different world you didn’t know exists in DC. There are a number of African promoters/event organizers in DC and I’d love to see one inclusive event happen.

Come through if you’re in the area! All details here.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers