Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 470

May 26, 2013

Weekend Special N°1002

Here’s a couple of links we’ve bookmarked for reading and watching this week. Chadian director Mahamat Saleh Haroun’s new film “Grigris” premiered in Cannes. First reviews are up in Variety, the Guardian, Hollywood Reporter and rfi.fr. Rfi also has an interview with Haroun about his first meeting with the film’s lead actor and Burkinabe dancer Souleymane Démé (that’s Haroun, Démé, and Anaïs Monory, on the red carpet above; watch one of the film’s opening scenes to get what’s going on here). Less space was taken up in the papers by the fact Démé was held for hours by immigration officers in Brussels Airport on his way to Cannes. Says Haroun: “I think when you want a continent of freedom, it is outrageous that not only do we [Haroun has been residing in France for years] expell the undocumented, but also those people who come here with their papers in order.”

What’s happening in Salone? Joan Baxter asks: “Who are the new landlords in Sierra Leone and what lands do they hold?”

The Sierra Leone government is providing the Chinese company Hainan Natural Rubber Group 135,000 hectares [333,592 acres] of land in the country for rubber and rice in exchange for a 10 percent share. An Italian company, FNP Agriculture Limited, holds a lease on 15,000 hectares [37,066 acres] in the north of the country. Other investors claiming large land holdings in the country include the British firm Lion Mountains Agrico. Ltd (14,000 hectares or 34,594 acres), and another British firm, Whitestone Agriculture (SL) Ltd. (542,279 hectares or 1.3 million acres) in the north of the country.

Meanwhile, on anthropologist Mats Utas’s blog, Tilde Berggren questions a recent Swedish Government’s aid scheme in Sierra Leone:

According to a number of local and international NGO’s, journalists and researchers monitoring the situation on the ground, the large scale investment in Sierra Leone between Addax Onyx Group (AOG) and Swedfund, as well as a range of additional investors, is causing concern. The main concern is that the investment is contributing to poverty, decreased access to basic rights and may increase instability and anger amongst the local population. Swedfund is consistently dismissing the concerns, arguing that the monitoring of the situation is not sufficient and not carried out in detail, hence not trustworthy and does not illustrate the overall situation. (Swedish Governmental funds, land grabbing and human rights in Sierra Leone)

Better news on Sierra Leone: The newly launched Research in Sierra Leone Studies: Weave is a refereed, open access, open-text, electronic journal that publishes articles, book reviews, interviews, drama, fiction, and poetry on Sierra Leonean themes from national, international, diasporic, and global perspectives, aiming to “liberate Sierra Leonean scholars into international scholarship”.

This week’s series of photographs by Iwan Baan in the New York Times of Makoko’s “School at Sea” reminded me of a recent piece over at Nairaland Forum by “a Nigerian American” who asks: “Why Is Eko Atlantic Legal, And Makoko Illegal?”

Makoko is a floating residential structure built by private initiative, as is Eko Atlantic. The differences between the two are trivial. It is now funny to me that the ACN led ‘Awoist’ (Awolowo himself as advocate for ending poverty with socialism) government of Babatunda Fashola believes the Makoko developments are illegal, while Eco Atlantic has not only been considered legal, but allowed to, in it’s development, violate several other Nigeria laws such as having an independent power grid before the grid was decentralized only a few months ago, as well as a Free Trade Zone, which Tinapa in Calabar has still not been granted upon completion due to the ‘legal’ (class) implications of both.

A much-circulated follow-up piece on the discussion between Santiago Zabala and Hamid Dabashi (and less on Slavoi Zizek) by Aditya Nigam in Critical Encounters about the End of Postcolonialism and the Challenge for ‘Non-European’ Thought:

I take Dabashi’s injunction (…) – that of the need to transcend the West versus non-West binary instituted by the colonial condition and continued through the postcolonial, seriously. In so doing, I also want to raise some questions about the challenges for the non-European thinker today. (…) One way of taking Dabashi’s injunction seriously is to move beyond this need to say that ‘we also have philosophy’ or ‘we also have thought’ – to the same white man who he describes as a chimera. For some us grappling with the issues of what it is to think in India/ South Asia today, it is becoming increasingly clear that this task is impossible to accomplish – indeed even begin meaningfully – without challenging the canon itself.

Eve Fairbanks wrote a long report (published in Moment) on South African campus life in the city of Bloemfontein. The interesting part is where Fairbanks details the “resegregation”, as she calls, that happened in some of the University of The Free State’s dorms in the late nineties.

Karee— [a dorm] named for a drought-resistant tree found in the South African desert—had been built in 1978, as apartheid rule was consolidating and Afrikaans-language universities were expanding. The photos my teacher had mentioned were class photographs. The first dozen or so showed only white boys arranged on the dorm stoop, mugging for the camera. Then, in 1992, a few blacks appeared. There was one looking proud in a mauve suit, and another in a yellow shirt, his hip popped out in a jaunty contrapposto, his lips stretched wide in an enigmatic smile. 1993, 1994, 1995: Every year there were more black students, intermingled with the whites.

And then, in 1997, one year after the riot Billyboy Ramahlele witnessed, something new appeared in the photo: two flags from the age of white supremacy in South Africa—one from the old Afrikaner republic and one from the apartheid state that followed it. They were jarring to see, held high by two white boys in the last row right over the head of a black boy in a wide-brimmed hat. Over the following years, the flags remained, but the black students in the photos disappeared. By 1999, the class photo was all white again, and it stayed that way until 2008, the last year for which there was a picture.

File under unexpected collaborations: Congolese painter Chéri Samba illustrated a fancy travel guide for Paris, one of two cities he calls home:

Warscapes publishes an excerpt from the English translation of Mia Couto’s Tuner of Silences (originally published as “Jesusalém” in 2009). Don’t know why it still takes years to publish an English translation of Mozambique’s foremost author of fiction. An interview with Couto here; a rare review of the book here.

There’s a new book by Zimbabwean writer NoViolet Bulawayo: We Need New Names. Granta published an extract here. The New York Times calls it a . Also read Bulawayo’s short story, “Blak Power,” published by Guernica earlier this month.

More new fiction: Belgian-Nigerian writer Chika Unigwe’s new novel “De Zwarte Messias” (“The Black Messiah”) was launched in Antwerp this week. An English edition will most probably follow soon. The story is based on the life of Olaudah Equiano, Nigerian pioneer of the abolitionist cause. The English translation of the original Dutch title (“The Black Messiah”) is mine, but you never know with these Dutch editors. See the atrocious cover and translation publisher De Geus has come up with recently for Binyavanga Wainaina’s One Day I Will Write About This Place:

Joe Wright is directing Aimé Césaire’s “A Season in the Congo” in London this summer. The play follows Lumumba’s efforts to free the Congolese from Belgian rule and the political struggles that led to his assassination in 1961. Curiously, Wright seems to have chosen Ralph Manheim’s translation over the one by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. (Lead role for Chiwetel Ejiofor, dance choreography by Belgian-Moroccan Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui.) Details and tickets here. The Guardian ran an interview with Wright about the play last year. Rumor has it he is also working on a film adaptation.

Joe Wright is directing Aimé Césaire’s “A Season in the Congo” in London this summer. The play follows Lumumba’s efforts to free the Congolese from Belgian rule and the political struggles that led to his assassination in 1961. Curiously, Wright seems to have chosen Ralph Manheim’s translation over the one by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. (Lead role for Chiwetel Ejiofor, dance choreography by Belgian-Moroccan Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui.) Details and tickets here. The Guardian ran an interview with Wright about the play last year. Rumor has it he is also working on a film adaptation.

Finally, two music videos as a mini-Weekend Music Break. First is a track taken from Owiny Sigoma Band’s second album ‘Power Punch’ (remember them). The video was shot on location in Zanzibar on an iPhone. Might this be a first “iPhone-music-video” featured here on the blog?

And new South African (Cape Town) Hip-Hop that made us sit up: Slipper’s “Ndivoteleni”:

Weekend Special

Here’s a couple of links we’ve bookmarked for reading and watching this week. Chadian director Mahamat Saleh Haroun’s new film “Grigris” premiered in Cannes. First reviews are up in Variety, the Guardian, Hollywood Reporter and rfi.fr. Rfi also has an interview with Haroun about his first meeting with the film’s lead actor and Burkinabe dancer Souleymane Démé (that’s Haroun, Démé, and Anaïs Monory, on the red carpet above; watch one of the film’s opening scenes to get what’s going on here). Less space was taken up in the papers by the fact Démé was held for hours by immigration officers in Brussels Airport on his way to Cannes. Says Haroun: “I think when you want a continent of freedom, it is outrageous that not only do we [Haroun has been residing in France for years] expell the undocumented, but also those people who come here with their papers in order.”

What’s happening in Salone? Joan Baxter asks: “Who are the new landlords in Sierra Leone and what lands do they hold?”

The Sierra Leone government is providing the Chinese company Hainan Natural Rubber Group 135,000 hectares [333,592 acres] of land in the country for rubber and rice in exchange for a 10 percent share. An Italian company, FNP Agriculture Limited, holds a lease on 15,000 hectares [37,066 acres] in the north of the country. Other investors claiming large land holdings in the country include the British firm Lion Mountains Agrico. Ltd (14,000 hectares or 34,594 acres), and another British firm, Whitestone Agriculture (SL) Ltd. (542,279 hectares or 1.3 million acres) in the north of the country.

Meanwhile, on anthropologist Mats Utas’s blog, Tilde Berggren questions a recent Swedish Government’s aid scheme in Sierra Leone:

According to a number of local and international NGO’s, journalists and researchers monitoring the situation on the ground, the large scale investment in Sierra Leone between Addax Onyx Group (AOG) and Swedfund, as well as a range of additional investors, is causing concern. The main concern is that the investment is contributing to poverty, decreased access to basic rights and may increase instability and anger amongst the local population. Swedfund is consistently dismissing the concerns, arguing that the monitoring of the situation is not sufficient and not carried out in detail, hence not trustworthy and does not illustrate the overall situation. (Swedish Governmental funds, land grabbing and human rights in Sierra Leone)

Better news on Sierra Leone: The newly launched Research in Sierra Leone Studies: Weave is a refereed, open access, open-text, electronic journal that publishes articles, book reviews, interviews, drama, fiction, and poetry on Sierra Leonean themes from national, international, diasporic, and global perspectives, aiming to “liberate Sierra Leonean scholars into international scholarship”.

This week’s series of photographs by Iwan Baan in the New York Times of Makoko’s “School at Sea” reminded me of a recent piece over at Nairaland Forum by “a Nigerian American” who asks: “Why Is Eko Atlantic Legal, And Makoko Illegal?”

Makoko is a floating residential structure built by private initiative, as is Eko Atlantic. The differences between the two are trivial. It is now funny to me that the ACN led ‘Awoist’ (Awolowo himself as advocate for ending poverty with socialism) government of Babatunda Fashola believes the Makoko developments are illegal, while Eco Atlantic has not only been considered legal, but allowed to, in it’s development, violate several other Nigeria laws such as having an independent power grid before the grid was decentralized only a few months ago, as well as a Free Trade Zone, which Tinapa in Calabar has still not been granted upon completion due to the ‘legal’ (class) implications of both.

A much-circulated follow-up piece on the discussion between Santiago Zabala and Hamid Dabashi (and less on Slavoi Zizek) by Aditya Nigam in Critical Encounters about the End of Postcolonialism and the Challenge for ‘Non-European’ Thought:

I take Dabashi’s injunction (…) – that of the need to transcend the West versus non-West binary instituted by the colonial condition and continued through the postcolonial, seriously. In so doing, I also want to raise some questions about the challenges for the non-European thinker today. (…) One way of taking Dabashi’s injunction seriously is to move beyond this need to say that ‘we also have philosophy’ or ‘we also have thought’ – to the same white man who he describes as a chimera. For some us grappling with the issues of what it is to think in India/ South Asia today, it is becoming increasingly clear that this task is impossible to accomplish – indeed even begin meaningfully – without challenging the canon itself.

Eve Fairbanks wrote a long report (published in Moment) on South African campus life in the city of Bloemfontein. The interesting part is where Fairbanks details the “resegregation”, as she calls, that happened in some of the University of The Free State’s dorms in the late nineties.

Karee— [a dorm] named for a drought-resistant tree found in the South African desert—had been built in 1978, as apartheid rule was consolidating and Afrikaans-language universities were expanding. The photos my teacher had mentioned were class photographs. The first dozen or so showed only white boys arranged on the dorm stoop, mugging for the camera. Then, in 1992, a few blacks appeared. There was one looking proud in a mauve suit, and another in a yellow shirt, his hip popped out in a jaunty contrapposto, his lips stretched wide in an enigmatic smile. 1993, 1994, 1995: Every year there were more black students, intermingled with the whites.

And then, in 1997, one year after the riot Billyboy Ramahlele witnessed, something new appeared in the photo: two flags from the age of white supremacy in South Africa—one from the old Afrikaner republic and one from the apartheid state that followed it. They were jarring to see, held high by two white boys in the last row right over the head of a black boy in a wide-brimmed hat. Over the following years, the flags remained, but the black students in the photos disappeared. By 1999, the class photo was all white again, and it stayed that way until 2008, the last year for which there was a picture.

File under unexpected collaborations: Congolese painter Chéri Samba illustrated a fancy travel guide for Paris, one of two cities he calls home:

Warscapes publishes an excerpt from the English translation of Mia Couto’s Tuner of Silences (originally published as “Jesusalém” in 2009). Don’t know why it still takes years to publish an English translation of Mozambique’s foremost author of fiction. An interview with Couto here; a rare review of the book here.

There’s a new book by Zimbabwean writer NoViolet Bulawayo: We Need New Names. Granta published an extract here. The New York Times calls it a . Also read Bulawayo’s short story, “Blak Power,” published by Guernica earlier this month.

More new fiction: Belgian-Nigerian writer Chika Unigwe’s new novel “De Zwarte Messias” (“The Black Messiah”) was launched in Antwerp this week. An English edition will most probably follow soon. The story is based on the life of Olaudah Equiano, Nigerian pioneer of the abolitionist cause. The English translation of the original Dutch title (“The Black Messiah”) is mine, but you never know with these Dutch editors. See the atrocious cover and translation publisher De Geus has come up with recently for Binyavanga Wainaina’s One Day I Will Write About This Place:

Joe Wright is directing Aimé Césaire’s “A Season in the Congo” in London this summer. The play follows Lumumba’s efforts to free the Congolese from Belgian rule and the political struggles that led to his assassination in 1961. Curiously, Wright seems to have chosen Ralph Manheim’s translation over the one by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. (Lead role for Chiwetel Ejiofor, dance choreography by Belgian-Moroccan Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui.) Details and tickets here. The Guardian ran an interview with Wright about the play last year. Rumor has it he is also working on a film adaptation.

Joe Wright is directing Aimé Césaire’s “A Season in the Congo” in London this summer. The play follows Lumumba’s efforts to free the Congolese from Belgian rule and the political struggles that led to his assassination in 1961. Curiously, Wright seems to have chosen Ralph Manheim’s translation over the one by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. (Lead role for Chiwetel Ejiofor, dance choreography by Belgian-Moroccan Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui.) Details and tickets here. The Guardian ran an interview with Wright about the play last year. Rumor has it he is also working on a film adaptation.

Finally, two music videos as a mini-Weekend Music Break. First is a track taken from Owiny Sigoma Band’s second album ‘Power Punch’ (remember them). The video was shot on location in Zanzibar on an iPhone. Might this be a first “iPhone-music-video” featured here on the blog?

And new South African (Cape Town) Hip-Hop that made us sit up: Slipper’s “Ndivoteleni”:

May 23, 2013

The BBC’s standards of journalism when it comes to South Africa

Yes, the BBC sent the snooty John Simpson to South Africa to do a bit of parachute journalism and be led around by the white “rights” group Afriforum (since when are they are a credible source?) to came up with this insulting question: “Do white people have a future in South Africa?” Read it here. The main claims of the piece (and a documentary broadcast in the UK on Sunday night) is that the white poor number about 400,000 (that would be about 10% of the white population), there are 80 “white squatter camps” situated around the capital Pretoria, and that there’s a deliberate attempt on the part of the new government to neglect whites. These reports usually add attacks on white farmers into the mix as if there are direct links between these phenomena. And the BBC did that too. It’s a mashup of all the nonsense Afriforum (and its alliances like Solidarity) peddles to local and foreign journalists who care to listen. In most of these articles and “documentaries” white poverty is exaggerated and treated as unnatural. All of this is of course propaganda and fits in well with the attempts at inventing history or the new victim discourse among white South Africans lapped up by foreign media. We were discussing writing a lengthy post pointing out how reports about white poverty in South Africa seem to all use the same photographs, visit the same “white squatter camp” over and over and pretend or imply that all black people are now middle class (the real scandal in South Africa is black poverty of course), among others, but then we remembered there is enough evidence out there the BBC could have consulted.

Like the fact that white South Africans are doing just well–actually way better than expected–since the end of Apartheid (the most recent study to confirm this comes from the South African Institute of Race Relations, an institute not known for its support either for the liberation struggle or their love for the current ruling party) and most CEOs and managers are still majority white. As for conditions on farms, read this. Finally, there’s the the article by Africa Check, a South African website doing just that: fact checking. They systematically refute the falsehoods of the BBC report and concluded: “The claim that 400,000 whites are living in squatter camps is grossly inaccurate. If that were the case, it would mean that roughly ten percent of South Africa’s 4.59-million whites were living in abject poverty. Census figures suggest that only a tiny fraction of the white population – as little as 7,754 households – are affected.”

The spectacle of Ernst Roets, an Afriforum leader, and a representative from one of Afriforum’s partners, Solidarity, suddenly claiming they can’t say where those statistics originate, is also something to behold. Word is Roets is drafting a reply made up of more made up statistics.

There’s a certain amount of irony at play here also that Africa Check needed to be prompted by a BBC report to refute the stats Afriforum, Afrikaner Genocide and other white apocalypse organizations have been poisoning the public debate with for a good ten years now.

But back to the BBC which generally serves up contextual and well-researched reporting on South Africa: They do slip up occasionally when it comes to that country. Just recently the BBC presented FW de Klerk, the last white leader of South Africa, who as recently as last year still defended the moral basis for Apartheid, as an “analyst” of postapartheid South Africa. (And after watching it, I am still trying to figure out whether Peter Hain’s recent “documentary” film is really about the people of Marikana–as it is marketed–or about him?)

It seems unlikely the BBC will apologize over this and we doubt it will be pressured by its viewers and readers judging by the online comments on the story or how the story was circulated on the web (sites like Huffington Post republished it without any critical commentary) or shared as truth on Twitter and Facebook.

* BTW, the BBC is not the only “global news” operator that draws on Afriforum and its alliance-partners for research or analysis. At the outset of the Marikana mine massacre in August last year where police murdered 34 miners in cold blood, Al Jazeera turned to Solidarity for comment and analysis.

The unfounded fears of a Zulu hegemony

The university’s announcement doesn’t mean that it will become a dual-medium English-isiZulu institution in 2014. Far from it. In keeping with the gradualism of South Africa’s transition from apartheid, the requirement is flexible and allows faculties to exempt students with evidence of isiZulu proficiency at the required level. At the moment, that’s well over half of the university’s annual intake of new students. And even though there are plans to introduce isiZulu as a medium of instruction, the university estimates that it won’t happen until at least 2018, because centuries of colonialism and apartheid have meant that very little work has gone into developing isiZulu and the country’s other indigenous languages for use in higher education.

In some quarters, the mostly lauded decision has been called unconstitutional, which it isn’t, while others said it was impractical and unfair, as it will mean that many non-isiZulu speakers will encounter the language for the first time in an educational setting over a decade later than the optimal time to be learning a new language. Others have argued it will be expensive. Indeed, it was estimated in 2006 that the cost of this first phase of the university’s isiZulu development policy would cost almost $1.5 million at today’s exchange rate.

Some have even said the decision is further evidence of the preeminence of the Zulu hegemony in current politics.

Stanley Mabuza, an aggrieved listener of public radio station SAfm, emailed the station’s The Forum@8 morning talk show to register his dissatisfaction. Mabuza’s email, read by the show’s host, said, “When we speak of transformation in our tertiary institutions, we are not inviting the introduction of unpopular policies by senseless individuals who are intent at institutionalizing tribalism in our public institutions. You cannot force an Indian child who wants to study at the UKZN to now include isiZulu in their programme. I’m not being tribalistic, but I’m afraid some people are trying to force their language and culture upon all groups in the country.”

Mabuza’s comment underlines what has perhaps been the most surprising aspect of the reaction, which is that some of the backlash has, for various reasons, come from black South Africans against what is perceived as an act of Zulu domination.

Much of the criticism is answered by the late educationist and anti-apartheid activist Neville Alexander (portrait above) in his posthumous collection of essays, Thoughts on the New South Africa. Alexander, who played a central role in developing the country’s higher education language policy, argues that developing African languages is necessary because English and Afrikaans—the West Germanic language whose imposition on black high school students was the final straw that triggered the 1976 Soweto Uprising—are not functioning adequately in South Africa as languages of higher education. He says many students aren’t making it to graduation owing in large part to a lack of proficiency and grasp of idiom in languages not their own. He also rebuts as a non-question the notion that developing African languages in the way UKZN and other South African universities are will create “ethnic universities”.

Alexander has also, in other essays and papers, charted the development of an appetite for multilingualism in post-apartheid South Africa, despite what he described as the persistent fallacy that assigning indigenous languages an official status in post-colonial African states would lead to ethnic rivalry and separatist movements. He put it down to South Africa’s liberation movement—in its true, broad multiparty sense, not just the African National Congress—understanding multilingualism’s role in intercultural communication and social cohesion.

That some black South Africans have reacted angrily to this announcement could be due to a misunderstanding of the rationale behind the UKZN’s choice of isiZulu as its African language to punt—a choice informed by the university being located in a mostly isiZulu-speaking province (in a country where isiZulu is the most common first language). The choice was also informed by the purpose of this initial phase of the policy, which is to provide the university’s non-isiZulu-speaking graduates with the facility to interact with the communities where they’ll be living and working.

The reaction may also be due to not knowing that the country’s other universities have also adopted a similar policy to develop other indigenous languages. The University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, for example, is focusing its language development work on Sesotho and Rhodes University in Grahamstown in the Eastern Cape is developing isiXhosa. All of them are doing so following the path advocated by the national policy: first focus on building proficiency in the language among all staff, enrolled students and graduates while at the same time developing the language for introduction at a later stage as a full-fledged language of instruction at the institution.

This nonetheless has not stopped some influential pundits from arguing that UKZN’s decision is further evidence of the so-called “Zulufication” of the country, as intimated by Mcebisi Ndletyana, head of the faculty of political economy at the Mapungubwe Institute think tank. Ndletyana said, during an interview on The Forum@8 this week, that language policy in the country should be directed towards encouraging people to speak languages other than their own because regional monolingual communities, which he said South Africa has many, propagate ethnic stereotypes that can be co-opted for political campaigning.

Absent from Ndletyana’s analysis is the recognition that no such monolinguistic communities exists in South Africa, save for a few enclaves of English and, to a lesser extent, Afrikaans speakers. The majority of South Africans have a basic knowledge of English and are fluent in at least one other language. Ndletyana’s definition of monolingualism, it appears, scopes out English and Afrikaans, and refers only to speakers of one indigenous South African language.

But Alexander warned of this specific type of casual acceptance of the English and Afrikaans linguistic dominance. He said English and Afrikaans gained their position as “legitimate languages” first through colonial conquest, then through the consent of the victims of colonial subjugation who accepted and internalised the superiority of the languages. South Africans would do well to keep his warning in mind.

Language policy in South Africa and the unfounded fears of a Zulu hegemony

Given South Africa’s stated commitment to multilingualism, you might not think that a requirement from one of the country’s universities that its students learn an indigenous African language would raise much alarm. Yet alarm has nonetheless been the reaction from a few unexpected quarters to the University of KwaZulu-Natal’s announcement that all first-year students enrolled from next near onwards will be required to develop “some level” of isiZulu proficiency by the time they graduate.

The university’s announcement doesn’t mean that it will become a dual-medium English-isiZulu institution in 2014. Far from it. In keeping with the gradualism of South Africa’s transition from apartheid, the requirement is flexible and allows faculties to exempt students with evidence of isiZulu proficiency at the required level. At the moment, that’s well over half of the university’s annual intake of new students. And even though there are plans to introduce isiZulu as a medium of instruction, the university estimates that it won’t happen until at least 2018, because centuries of colonialism and apartheid have meant that very little work has gone into developing isiZulu and the country’s other indigenous languages for use in higher education.

In some quarters, the mostly lauded decision has been called unconstitutional, which it isn’t, while others said it was impractical and unfair, as it will mean that many non-isiZulu speakers will encounter the language for the first time in an educational setting over a decade later than the optimal time to be learning a new language. Others have argued it will be expensive. Indeed, it was estimated in 2006 that the cost of this first phase of the university’s isiZulu development policy would cost almost $1.5 million at today’s exchange rate.

Some have even said the decision is further evidence of the preeminence of the Zulu hegemony in current politics.

Stanley Mabuza, an aggrieved listener of public radio station SAfm, emailed the station’s The Forum@8 morning talk show to register his dissatisfaction. Mabuza’s email, read by the show’s host, said, “When we speak of transformation in our tertiary institutions, we are not inviting the introduction of unpopular policies by senseless individuals who are intent at institutionalizing tribalism in our public institutions. You cannot force an Indian child who wants to study at the UKZN to now include isiZulu in their programme. I’m not being tribalistic, but I’m afraid some people are trying to force their language and culture upon all groups in the country.”

Mabuza’s comment underlines what has perhaps been the most surprising aspect of the reaction, which is that some of the backlash has, for various reasons, come from black South Africans against what is perceived as an act of Zulu domination.

Much of the criticism is answered by the late educationist and anti-apartheid activist Neville Alexander (portrait above) in his posthumous collection of essays, Thoughts on the New South Africa. Alexander, who played a central role in developing the country’s higher education language policy, argues that developing African languages is necessary because English and Afrikaans—the West Germanic language whose imposition on black high school students was the final straw that triggered the 1976 Soweto Uprising—are not functioning adequately in South Africa as languages of higher education. He says many students aren’t making it to graduation owing in large part to a lack of proficiency and grasp of idiom in languages not their own. He also rebuts as a non-question the notion that developing African languages in the way UKZN and other South African universities are will create “ethnic universities”.

Alexander has also, in other essays and papers, charted the development of an appetite for multilingualism in post-apartheid South Africa, despite what he described as the persistent fallacy that assigning indigenous languages an official status in post-colonial African states would lead to ethnic rivalry and separatist movements. He put it down to South Africa’s liberation movement—in its true, broad multiparty sense, not just the African National Congress—understanding multilingualism’s role in intercultural communication and social cohesion.

That some black South Africans have reacted angrily to this announcement could be due to a misunderstanding of the rationale behind the UKZN’s choice of isiZulu as its African language to punt—a choice informed by the university being located in a mostly isiZulu-speaking province (in a country where isiZulu is the most common first language). The choice was also informed by the purpose of this initial phase of the policy, which is to provide the university’s non-isiZulu-speaking graduates with the facility to interact with the communities where they’ll be living and working.

The reaction may also be due to not knowing that the country’s other universities have also adopted a similar policy to develop other indigenous languages. The University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, for example, is focusing its language development work on Sesotho and Rhodes University in Grahamstown in the Eastern Cape is developing isiXhosa. All of them are doing so following the path advocated by the national policy: first focus on building proficiency in the language among all staff, enrolled students and graduates while at the same time developing the language for introduction at a later stage as a full-fledged language of instruction at the institution.

This nonetheless has not stopped some influential pundits from arguing that UKZN’s decision is further evidence of the so-called “Zulufication” of the country, as intimated by Mcebisi Ndletyana, head of the faculty of political economy at the Mapungubwe Institute think tank. Ndletyana said, during an interview on The Forum@8 this week, that language policy in the country should be directed towards encouraging people to speak languages other than their own because regional monolingual communities, which he said South Africa has many, propagate ethnic stereotypes that can be co-opted for political campaigning.

Absent from Ndletyana’s analysis is the recognition that no such monolinguistic communities exists in South Africa, save for a few enclaves of English and, to a lesser extent, Afrikaans speakers. The majority of South Africans have a basic knowledge of English and are fluent in at least one other language. Ndletyana’s definition of monolingualism, it appears, scopes out English and Afrikaans, and refers only to speakers of one indigenous South African language.

But Alexander warned of this specific type of casual acceptance of the English and Afrikaans linguistic dominance. He said English and Afrikaans gained their position as “legitimate languages” first through colonial conquest, then through the consent of the victims of colonial subjugation who accepted and internalised the superiority of the languages. South Africans would do well to keep his warning in mind.

May 22, 2013

The Real Housewives of Harare

Memory Gumbo is a mother, an “ordinary woman”, living in Harare, Zimbabwe. Tsitsi Dangarembga is an internationally recognized writer and filmmaker, living in Harare as well. Both agree on at least one thing: That “No to loitering,” sold to the public as a ‘crackdown’ on sex workers, has nothing to do with sex workers. In plain language: The current campaign against loitering has nothing to do with loitering. It’s an attack on women, and it’s part and parcel of Zimbabwean history, colonial and post-colonial.

It’s election season in Zimbabwe, and so, as before, the State has engaged in ‘urban renewal’ by ‘cleaning the streets.’ Under British rule, today’s Zimbabwean women fought for the right to move about in public. The colonial administration used the “immorality and prostitution of native women” as an alibi for draconian, repressive measures against “native women”, and the women refused to go quiet into that good night: “From the Salisbury women’s beer hall boycotts of the 1920s to the rock-throwing of “Anna alias Flora” in 1933, from the relative freedom of mapoto liaisons to the organized accumulation represented by Emma MaGumede and by the Bulawayo property owners, ordinary women constantly wrung whatever gains they could from a range of meager opportunities.”

In 1983, three years into independence, the State launched Operation Chinyavada, Operation Scorpion. 3000 or so women were rounded up, essentially for walking down the road. In Mutare, 200 women factory workers, on their way to work, were arrested. They were held in a football stadium until their employer came and effected their release: “The assumption that any unmarried or unemployed women are probably prostitutes seems to have all but gone unchallenged, in a country whose leadership once claimed it hoped to emancipate women from traditional restrictions based on gender hierarchies.”

Since those halcyon days, the State has dipped into the ‘cleansing’ operation and rhetoric repeatedly. In May 2005, when the State launched Operation Murambatsvina, Operation Drive Out the Trash, prominent among the ‘trash’ were sex workers. From the colonial days to the present, women on the move in public have been attacked as sex workers. And from the colonial days to the present, women, individually and collectively, have rejected the attempt.

Memory Gumbo rejects it: “You can’t go to the shops after 8pm because they assume everyone is a hooker. It’s plain harassment, simple.” Tsitsi Dangaremba rejects it as well: “Women were part of the liberation struggle and we have been working with the rest of the nation to build this country and therefore we expect to be treated as equal as full citizens of this country and also enjoy our citizens’ rights.”

So, when Al Jazeera tells you “Zimbabwe cracks down on the oldest profession,” don’t believe it. The target is, as it always has been, “ordinary women”. Simple.

Photo Credit: woman protesting in Harare against a 2012 spree of arbitrary arrests by local police (Deutsche Welle).

Kamuzu Day and Malawi’s Festival of Forgetting

*By Jimmy Kainja*

Last week we had a public holiday in Malawi. May 14 is “Kamuzu Day,” when the nation celebrates the life of its founding president, Hastings Kamuzu Banda whose autocratic rule lasted between 1964 and 1994. The day has been there since Kamuzu’s reign, during which it was celebrated as his birthday. This despite the fact that Kamuzu himself may never have known his actual birthday, owing to the fact that such events were not recorded around the time he was born. (He told everyone he was born in 1906 but most people reckon he was actually born eight years earlier.) This year was especially interesting for me because I have not been in Malawi on May 14 for the last 12 years or so. Social networks were buzzing with Kamuzu nostalgia, newspapers published thick supplements on him and radio stations were jostling to outdo each other with their Kamuzu “specials”. But is the annual bonanza of tributes to the self-styled “Lion of the Nation” really about Kamuzu, or does it instead reflect anxieties about the failure of leadership since the arrival of multi-party democracy in 1994? And why is there no discussion of the kind of dictator he was?

Kamuzu clearly loved Malawi as a country. He took advantage of generous development aid projects of the 1960s to mid 1970s that was aimed at helping develop former European colonies to fulfill his vision for the country. Most of such projects are still visible today. He built the country’s only international airport; hydroelectric power stations that his successors are struggling to upgrade; he built most of the roads that connects the country’s four cities; he oversaw the most competent, organised and disciplined civil service that Malawi has ever had; he built the University of Malawi (the one his successors are failing to run) and he built the two main referral hospitals that the country has.

This is a foundation that sustained his reign of terror. Yet it is the same foundation that his successors could have easily built on when his regime finally fell in 1994.

Like many sub-Saharan Africa countries that were doing away with their dictators in the early to mid 1990s following the end of the Cold War and with the end of Apartheid, Malawians demanded social, economic and political change. External and internal pressure forced Kamuzu to call for a referendum in 1993, giving Malawians a chance to choose whether they wanted to continue with his one party authoritarian rule or to adopt multi-party democracy. 64% of Malawians chose the latter. This led to a 1994 general elections where Kamuzu lost to Bakili Muluzi. Kamuzu was gracious in defeat; he congratulated Muluzi and wished him well before the vote count was over.

Before his death November of 1997, the aged and frail Kamuzu made a public statement asking Malawians who suffered under his autocratic leadership to forgive him. It was an unprecedented and unexpected move. The once mighty “lion” had been humbled, it could no longer roar and it was now owning up to its brutal past. Malawi prides itself as a “God fearing nation”, so probably Kamuzu knew that these “God fearing people” would indeed forgive him, as their Bibles teach. Kamuzu tolerated no dissent or opposing views for the entire 30 years he was in office. If Malawi is indeed a “God fearing” nation then Kamuzu was second inline – he was a demigod to be feared and revered.

Kamuzu created an inward-looking country, where he acquired this divine status that all his people were supposed to look up to. Anyone he felt was a threat to his “life presidency” was jailed, exiled or killed (Elliot reviewed the prison memoirs of the great poet Jack Mapanje a couple of years ago). Legend has it that he would feed some of those jailed to crocodiles. This cannot be verified but the rumour itself speaks volumes of a man Malawians today celebrate as a national hero worth shutting down national business for. On Kamuzu Day there were people sitting and watching in disgust as the nation celebrated as a hero the fallen despot that made their lives hell.

This is understandable and I sympathise with the victims of Kamuzu’s dictatorship. Yet the point of celebrating Kamuzu Day is far more complex than celebrating his life. It is a leadership failure in Malawi that has created this day. It works as a kind of smokescreen, inhibiting critical engagement with our present as much as our past. Malawian politics is not about policies and there are no ideological fault-lines. It is about individuals outdoing each other. When politicians parade their attributes on a political podium, as they do, they are not only talking about themselves, they are contrasting themselves with their rivals. The formula is that of a beauty contest. In this game of personalities none of the Malawi leaders that have come after Kamuzu — Muluzi, Bingu wa Mutharika and Joyce Banda — can outdo him. He built infrastructure and could point to it, and they have not. Simply put: these leaders have failed to build on the foundation Kamuzu built.

This is understandable and I sympathise with the victims of Kamuzu’s dictatorship. Yet the point of celebrating Kamuzu Day is far more complex than celebrating his life. It is a leadership failure in Malawi that has created this day. It works as a kind of smokescreen, inhibiting critical engagement with our present as much as our past. Malawian politics is not about policies and there are no ideological fault-lines. It is about individuals outdoing each other. When politicians parade their attributes on a political podium, as they do, they are not only talking about themselves, they are contrasting themselves with their rivals. The formula is that of a beauty contest. In this game of personalities none of the Malawi leaders that have come after Kamuzu — Muluzi, Bingu wa Mutharika and Joyce Banda — can outdo him. He built infrastructure and could point to it, and they have not. Simply put: these leaders have failed to build on the foundation Kamuzu built.

Consequently, these leaders have wanted to associate themselves with Kamuzu. If you cannot beat him, join him. Muluzi was slightly different probably because he was a direct successor. Yet he did his best to erase Kamuzu’s name, renaming almost everything that bore Kamuzu’s name. It was Mutharika who built Kamuzu’s lavish mausoleum at taxpayers’ expense. Yet in life Mutharika feared Kamuzu so much that he spent years in self-imposed exile during Kamuzu’s reign. After only one year in office, Joyce Banda has already renamed State House “Kamuzu Palace”. At the time of writing this piece, Banda was in Kasungu, Kamuzu’s home district, attending celebrations – wearing clothes bearing Kamuzu’s face.

It is this kind of nostalgia that has compromised transitional justice in Malawi. Malawi could well be the only country that celebrates the life of its autocratic dictator. No wonder that the Machiavellian figure of John Tembo, Kamuzu’s long time right-hand man and overseer of many of Kamuzu’s policies, remains prominent in mainstream politics today as the leader of Kamuzu’s party, the Malawi Congress Party. He is the leader of opposition in parliament and though he turns 81 years old this September, he will still contest the presidency once again in 2014. Tembo’s political durability is in part down to the fact that the succession of failed leaders that have come after 1994 means his MCP is, not unreasonably, regarded as Malawi’s most successful ruling party ever. Yet the history of that party tells its own story about Kamuzu. The MCP was the party of liberation formed by a generation of freedom fighters, who were later to suffer under Kamuzu’s presidency. The founder of the MCP was the late Orton Chirwa, who together with his wife, Vera, was arrested by Kamuzu 1981. Orton died in jail in 1992; Vera was released at the turn of multiparty democracy in 1993. Until today the couple remain Africa’s longest serving prisoners of conscience.

There have been some younger Malawians aspiring for leadership positions, including presidency. Unfortunately, some of them have already joined the hero worship bandwagon. As a way of justifying that the youth can also hold leadership positions, some of these younger aspirants are arguing that Kamuzu had the youngest-ever cabinet in the history of Malawi. Referring to his first cabinet, of 1964. Yet most of these yet aspirants forget to mention what happened next.

Kamuzu got rid of all these young intellectuals and leaders, one by one, following the Cabinet Crisis of 1964. Notably Henry Masauko Chipembere and Kanyama Chiume were exiled, and Yatuta Chisiza, like his brother Dunduzu before him, was gunned down by security forces. This epitomised Kamuzu’s 30 years rule. In 1983 there was the well documented case of Mwanza murders where four MPs were killed for simply suggesting that Kamuzu was ageing therefore there was a need to start succession plans. Of course the courts acquitted Kamuzu and Tembo in the trial that followed multiparty democracy simply because the government was too inept. For the record, Malawi government has never won any high profile case since 1994 – and there have been quite a few.

Tossing around Kamuzu’s name and image as a political tool is making Kamuzu into a heroic saint that bears little resemblance to the historical record. He was a ruthless authoritarian that caused a lot of pain to many people whose relatives and parents languished in jails, exile and some were killed without committing any crime at all. He ran a state without a justice system. He was the sole arbiter of truth. This is the side of Kamuzu that is slowly being erased from nation history, deliberately or not, and as we blur the lines of our past, it becomes more and more difficult to understand our present. Airbrushing Kamuzu’s legacy and creating false nostalgia that is only aimed at diverting the national psyche from current leadership failures is not only injustice for those that suffered during his reign, it also stifles national progress and development.

Malawi will not develop if nostalgia and hero-worshiping are drivers of its leadership. The country needs visionary leaders ready for public service. Leaders with policies that can drive the nation forward; this has nothing to do with anybody’s age, gender or tribe. Here the electorate have a role to pay: look beyond personalities and focus on their policies instead.

May 21, 2013

Senegalese collective who brought Abdoulaye Wade down reinvents media activism

“There are no foreclosed destinies, only deserted responsabilities” has become one of the mottos of the collective of Senegalese singers and journalists known as Y’En A Marre (“Enough is enough” in French). In the wake of the 2012 presidential elections, the group gained international recognition for leading the charge against then President Abdoulaye Wade, who was seeking a third term at age 86 while reportedly scheming to hand over the presidency to his son Karim Wade. Y’En A Marre’s international minute of fame may have passed with Macky Sall’s victory but its engagement as a new kind of political watchdog hasn’t faded since the ousting of Abdoulaye Wade. For its purpose is bigger: to form a united front against social injustice in Senegal and to shift the public debate away from politician bickering and back to the issues of ordinary Senegalese.

As the coordinator of the collective, Fadel Barro, warned a few months after Sall was elected [fr], “there’s no point in changing the conductor if you keep playing the same symphony”. Indeed “Y’En A Marre” was the war cry of the collective, but the larger task it has taken on is to advocate for the NTS or the Nouveau Type de Sénégalais (the New Kind of Senegalese).

In the midst of the 2012 campaign, Y’En A Marre had organized “problem fairs” (foires aux problèmes), during which population representatives held booths and asked candidates for solutions. Now Hip-Hop star Xuman has teamed up with Xeyti, another veteran rap artist, to launch a new assault on the usual communication channels between those who govern and those who are governed, one year after Sall became president.

With the Journal Rappé, a weekly 4-minute long news broadcast delivered in rhymes in both French and Wolof, Xuman and Keyti use one of the most popular mediums, music, to both inform a larger audience and hold the Senegalese establishment accountable, to educate through laughters and laugh at the educated.

All the visual clues of a regular news broadcast are present: the large desk, the well-dressed anchor, the shiny infographics, the wires at the bottom of the screen. Only one thing is out of order, the anchor gives a rap performance which begins with the same lines every time: “Welcome, take a seat / We’ve got news for you / There’s some good and some bad / But we’ve got news for you.”

From there on out, “l’information sans chichi” (News with no frills) is a thrilling ride through the weekly Senegalese and international news hashed out in fast-paced punchlines, first in French by Xuman, and then in Wolof by Keyti. The first installment was uploaded to YouTube a month ago:

Among young Senegalese, some had been worried that prominent members of the collective might use the celebrity acquired during the presidential campaign as a springboard to launch their own political career. It hasn’t happened, not yet at least. Others said Y’En A Marre members were getting too lenient with Macky Sall because of the role they played in his election, that after voicing the population’s concerns they had turned aphonic. Instead Y En A Marre members have continued to ring the alarm bell.

Since Macky Sall became president, Fadel Barro and Fou Malade have highlighted land grabs, taalibes begging in the streets or the raise of university fees. Members of the collective have also collaborated with Amnesty International to denounce impunity. In its latest installment, the Journal Rappé fires another warning shot: Xuman and Keyti bring up Sall’s stoutness to discuss corruption, signaling that the “politics of the belly”, as Jean-François Bayart named it, remains a threat to the legitimacy of Senegalese political leaders.

Political sentinels from within who have limited vested interests are a rare commodity; and among those, advocates for change able to cut through the education divide — adult literacy rate is below 50% in Senegal — are even harder to come by. Add to the mix the comical effect of well-crafted lines sung by popular artists in both French and Wolof and you have a recipe for success.

2sTV came to that realisation quickly and now broadcasts the Journal Rappé after its regular news schedule every Friday. Since the third installment, “on-the-ground correspondents” and guest anchors (other members of Y’En A Marre) have been added to the mix, which shows the experiment is progressing and is another sign of success beyond the ten of thousands of views received on YouTube.

As Xuman and Keyti hint in their interview with Global Voices blogger Anna Guèye [fr], the challenge will be to maintain quality and not let irrevence become a marketed product of primetime television.

Using a sports metaphor, Fadel Barro said last January [fr] that the Y’En A Marre squad was “like a national team”: “the leaders are in their respective clubs, working. But when duty calls, they answer”. Xuman and Keyti’s Journal Rappé is a renewed testament to this commitment, one that in time could become the symbol of the movement’s post-Wade engagement. Y’En A Marre is here to stay and that is welcome news for Senegal.

Strange Cargo: Jane Alexander at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine

Jane Alexander, The Sacrifices of God are a troubled spirit (Photograph by Mario Todeschini). Courtesy Museum for African Art.

Okwui Enwezor described the ephemera of Africa that arrived in European docks as “strange cargo”: as it was unloaded from ship to warehouse by longshoremen, as it was bid on, sold, and displayed in wealthy homes, lost and rediscovered, each object shaped European visions of Africa. ‘Africa’ as we imagine it now, was shaped by that strange cargo. Later in his essay in the January 1996 issue of frieze, Enwezor asked, “Why do we never consider the achievements of those artists who at great professional cost and individual isolation have not only transcended but have equally transfigured the borders constituting the notion of Africanity?” South African artist Jane Alexander’s work, now positioned throughout the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in Manhattan’s Morningside Heights neighbourhood, is part of the tradition of Africa’s strange cargo, but it is freight that – possibly at the cost of easy audience engagement, and curators’ comprehension – certainly transfigures notions of Africanity. Hers are not the masks and pretty pictures of African bodies: the smiling faces (or incongruous bodies) from the Dark Continent. Instead, her figures make the viewer reflect on the grotesque triumphalism inherent in looking away in the face of suffering, on the cost of participating – and benefiting from – great sweeps of violence, and the solitude of bearing the brunt of marching empires that see nothing of your existence.

Almost nine years ago, in July 2004, I made my way to the South African National Gallery in Cape Town, to see a show celebrating “A Decade of Democracy”. On the front of the museum’s dazzling white walls, the laughing, joyous photographic image of Tracey Rose’s “The Kiss” – an homage to and a parody of August Rodin’s marble perfection – greeted visitors. Rose is captured in all her carnality, corporeal imperfections intact, seated on the lap of her art dealer: it’s an image that would catch one’s eye anywhere, first because both people are beautiful, nude and are in the midst of a moment of delightful intimacy, but also because of the freedom, spontaneity, and love between them. In South Africa, of course, a seemingly white woman cavorting on a black man’s lap has added layers of significance. But these appearances of ‘racial’ identity are deceptive; although the woman in this monochromatic image, Rose, seems to be pale-skinned, she would not have been classified ‘white’ during apartheid, and much of her work makes reference to such complexities. Given that this was the frontispiece to an exhibit marking ten years out of the yoke of Afrikaner moral strictures, I entered the building expecting art that looked forward and outward: less introspection, and more unrestrained joy.

But inside, the story was far more complex. There, my first introduction to Jane Alexander’s work, Butcher Boys: three seated man/animals oddly reminiscent of an upside-down Pan—that delightful, sensuous creature with the lower body of a hoofed animal from Greek mythology. But Alexander’s animalistic men exhibit none of the voluptuous sexuality of Pan. The head of each of Alexander’s Boys is a different type of horned animal, and the bodies are lean and hungry, with musculature, rib, and spine showing. They sit in a row on a low bench, their long bodies a little hunched over, their legs in the pose of men who are waiting the long wait for some mode of unreliable public transport to take them away. In certain places, each Boy’s ribcage parts in a black gash, revealing spinal cord through bone-coloured flesh; a similar gash is repeated along the front, hinting of the passage of an autopsy knife. The skin on each horned head is drawn so spare over bone that the faces appear nearly skull-like; ears appear to be lopped off, and where the snout should extend to the mouth, another truncation: whatever appendages there might have been beyond the nose have been either hacked or sealed off. These Butcher Boys are not in conversation with one another, with the world, or with the viewer. Each deaf-mute head is turned towards a different direction: the glass eyes – opaque, black, and curiously luminescent – look away and out. I remember standing by those sets of oblique eyes, thinking: he sees me. He sees through me. He sees me not at all. It would be foolhardy to ask such men to hear, converse, internalise anything at all.

Alexander’s work does not operate on the pivot of amnesia—even at a moment of state-mandated celebration. Celebrations look to futures untainted by troubling pasts. They ask us to live in a decontextualised present. Her work is a meditation on what happens to such bodies, to such heads, to such souls. To see these man-beasts, seated thus on a bench is to be stilled – stunned – by the macabre inherent in the ordinary bystander. Butcher Boys is an unapologetic meditation on the animal nature of a collective body that disengaged from their political and social present: of those who waited, as if for a bus or a long-delayed plane, for some unnamed future – unspeaking, unhearing, eyes deliberately unfocused on culpability or responsibility. It would be a cliché to say, “When you butcher without awareness, or consume the spoils of such butchery without honouring the sacrifice, you become animal.” But that understanding is inherently present, without having to be overtly stated.

Since then, I’ve seen Alexander’s work on a few other occasions, and each time, I walk away having experienced something close to transfiguration – as if what I consumed has entered my body, changing the very way I be in this world.

***

When I heard that Jane Alexander’s work would be shown in the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, I wondered how the work I always associated with South Africa would translate here, in an April scattered with springtime’s hopeful crocuses and lily of the valley. As I travelled down to the city, upstate apple blossoms – their lives of delicate abundance lasting barely a week – were almost ready to shed petals on cars parked below. On the highway, the odd car was covered in white or pink disks: sequinned emissaries, travelling with a message of transformation.

The invitation to the opening of the show, “Surveys (from the Cape of Good Hope)” organised by the Museum for African Art in Manhattan, in collaboration with the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, promised the first major North American survey of tableaux, sculptures, and photomontages by Alexander. The image on the invitation (see above) is itself a montage: it shows “The Sacrifices of God are a troubled spirit”, Alexander’s installation in the ‘All Souls’ altar of the Cathedral of St John the Divine for the exhibition Personal Affects in 2004, a group exhibition also arranged by the Museum for African Art. Alexander’s amputated human-animal figures pose among rusting sickles and blood-red rubber gloves, all positioned in front of a triptych depicting the ascension of Jesus. Haloed kings, apostles, sinners, and angels surround the King of Kings, who looks on at the scene with kindly benevolence. The ornate gold frame made me think of the Baroque period’s penchant for hiding violence under gilded beauty.

Alexander’s work arrived in the Cathedral of St. John the Divine of the Episcopal Diocese of New York during the same fortnight as excerpts from a new memoir by Guantanamo Bay detainee, Mohamedou Ould Slahi, were released on Slate magazine. Before I stepped into the church, I sat outside, in the blooming gardens adjacent to the church, reading. Three peacocks – Phil, Jim, and Harry – strutted around the tulip beds. In a city that barely had space for a window planter, these rambling flower beds – a cross between an English garden, with hints of Dutch, and my grandmother’s hilltop home in Sri Lanka where peacocks meander through the coffee trees – sit like a jewelled necklace on a bare body. The towering cathedral walls, the cornerstone to which was laid in 1892, mirror the longings of the first great waves of European immigrants to the city; 1892 was the year that Ellis Island – the conduit to the hungry and the penniless of Europe – opened. There, strengthened by the walls enclosing the seven Chapels of the Tongues, commemorating the major immigrant groups pouring into and building the city, I sat and read an excerpt of Slahi’s memoirs, thinking of the hundred men on hunger strike, and the many who are being force-fed right now, men who describe the unspeakable pain meted to their bodies in the name of feeding them, in the name of sustaining and caring for their bodies. In Part One, “Endless Interrogations”, Slahi writes,

There was a very old Afghani fellow, who reportedly was arrested to turn over his son. The guy was mentally sick; he could not stop talking because he didn’t know where he was, nor why. But the guards kept dutifully hanging him. It was so pitiful; one day one of the guards threw him on his face, and he was crying like a baby.

I think about what it would be like for my father – a man in his seventies, diminished by several strokes – to be thusly hung, and flung on his face. To be damaged by young, able-bodied men, to weep uncontrollably from pain. I think about what it means, in these days of concentrated amnesia in the US, for a church such as St. John the Divine to carve out spaces in which we can remember the body in pain: to invite the liturgies of other faiths, to share the pulpit with the Other, to invite in difficult cargos. This is not a church that aims to use its monumental structure or its gilded beauty for forgetting. St. John’s asks: what does it mean, for us to bear witness, as a congregation? What does it mean for a place of worship to invite us to engage in “personal communion” with art that takes as risky journeys as does Alexander’s, to ask us to listen to the “still, small, voice within” during such perilous communions?

***

Inside St. John’s, friendly security guards and an official ‘welcomer’ at a booth encourage a donation of $10 to the church, although one can walk in for free. St. John is a tourist destination, and used to visitors. The space is so different from churches in Europe; here, the shadow spaces are soundchambers of noise, conversation, laughter, and congregational gregarity. An orchestra is practicing as I walk in: violins are being tuned, a singer is doing scales, a conductor is directing sections of musicians and their instruments. Near the orchestra’s practice space, cello cases, sweaters, and musicians’ bags are scattered on haphazard chairs: although St. John’s is used to strangers, this is a place of long-established friendships. The benevolent security men in navy blue uniforms walk throughout the church – less on patrol, more in conversation with visitors in the corridors.

Alexander’s work are adapted to each location; her preference, she writes, in an email exchange, “is for site specific installation, out of museums and galleries”, and away from the “white cube” and its attendant commercial aspirations. She prefers her work to be shown “in social spaces” that have broader groups of witnesses in mind, rather than “elitist and specialised audiences.” She has shown work in chapels before, as well as on a beach, a courtroom, and in the British Officers’ Mess room in the Castle of Good Hope – the fort first built by the Dutch arrivals in South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope. For Alexander, “the Cathedral is a rather ideal space for [these reasons] and some of my concerns around and interest in faith and proselytism, and aspects of Christianity and its social role.” Alexander has presented her work in a Cathedral space on two previous occasions: the first was also in Cathedral of St. John the Divine, as part of the exhibition Personal Affects (2004); the second was at the Galilee Chapel of Durham Cathedral, U.K. (2009), in the context of interdisciplinary research, “On Being Human”, organised by the Institute of Advanced Study at Durham University.

Alexander often references baboons, vultures and wild dogs; many of the figures that make an entrance here have appeared in different arrangements, and may not necessarily appear again as they do here, in “Surveys”, or in such a concentration. Such repetition – reappearances of the same ‘actors’ who re-enact various scenes in different settings – reminds me that atrocity and amnesia happens repetitively, and in many places, with similar players. Alexander’s work has elements that could be seen as specifically speaking to South Africa’s – and Africa’s – history: her work often includes industrial-strength gloves, machetes, sickles and earth. Placed together here, however, the different elements offer a different composite. The “Bushmanland earth” that I’ve seen used in other installations, for instance, evokes specificity – a specific geography, a certain set of historical events. But here, the iron ore’s brick red permeates the stained light and the sepulchral shadows of the church: the very air is bleeding in the chapel.

Detail of artwork from Jane Alexander: Surveys (from the Cape of Good Hope) organized by the Museum for African Art and presented by the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. Photo courtesy Museum for African Art.

In Morningside Heights, Alexander’s work also feels less suggestive of South Africa’s story, and more evocative of the last five centuries here: of the genocide necessary for the myth of America, for creating the empty spaces of deciduous forest and marshland in which immigrants subsequently made their home. Here, her work reminds of more recent events: the unbearable spaces of damaged flesh, forever incarcerations, and willful forgetting created by the twenty-first century’s oil wars. Manhattan is a place of forgetting, a location that uses suppression, selective memory, and avoidance through consumerism, aggressive responses as a means of sidestepping this blood-permeated history and present. It is a place in which one history is razed, only to build larger, more skyward-reaching monuments to power. These are the ways in which powerful nations sidestep horrendous histories of bloodletting – a cultivated amnesia common to both South Africa and the U.S.

For Alexander, “the Cathedral is a rather ideal space for [these reasons] and some of my concerns around and interest in faith and proselytism, and aspects of Christianity and its social role.” The exhibition’s curator, Pep Subirós, maintains that although Alexander’s decisions were “in frequent dialogue” with him, “and this dialogue sometimes modified her initial ideas,” the final decisions concerning the location and arrangement of the different artworks were Alexander’s – “not because she imposed” her ideas, “but because the spatial context and its multiple symbolic elements inevitably play an important part in the final configuration, and it was part of the art project to decide the forms and the limits of this relation. These are decisions for which the artist, ultimately, has to take responsibility.” In fact, Subirós understands the “curator’s role in a solo show of a living artist” to be more “that of a ‘midwife’ assisting the artist’s efforts for the best possible delivery of her or his work,” rather than that of a director.

Jane Alexander, Infantry (Photograph by Mario Todeschini). Photo courtesy the artist.

If you pay attention, you will see that Alexander and Subirós used elements specific to each chapel to interact with the stage-play world within each of the seven Chapels of the Tongues. In the St. Boniface Chapel, on an elevated red velvet carpet laid out for an arriving army, wild dog-men, arranged before the Cathedral’s monumental sculpture of St. Michael. They are three rows wide and nine deep, the slim, muscular bodies marching forward on black booted feet, dog-faces turned in unison to the right. This army’s uniform dedication is to that rightward gaze, focus firmly set on the duty to which they assigned their bodies, to those orders controlling their actions. They remind me of the beauty inherent in Soviet-era display parades, and of the impossibility of countering the might of such power. But in front of them, a minuscule dog figure: standing on all fours, feet planted in a pose that is both steady and ready for motion, gaze fixed clearly on its goal. This un-photogenic creature, unmighty as any defiant rabble-rouser, contains, in its taut, small body, the possibility of disruption. This figure, which can be so easily dismissed by the uniform rows of well-funded, well-trained armies, is the insurgent whose heart and mind no empire can win. One wonders if St. Michael will guide this cur to victory, or if the avenging warrior-angel is on the side of more conventional power.

Jane Alexander, Infantry (Photograph by Mario Todeschini). Photo courtesy the artist.

Jane Alexander, Lamb with stolen boots (Photograph by Mario Todeschini). Photo courtesy the artist.

The Chapel of St. Saviour contains a familiar booted figure from a show I saw in Cape Town in 2010, with the sound of World Cup vuvuzelas trumpeting in my ear. This is a bleached white Jesus figure (image above), posed eternally atop the munitions box: arms outstretched, crucified. But this Jesus, replete with a decorative crown of thorns, has neither arms nor hands – lifeless industrial-strength red gloves substitute for those appendages, hanging useless at the end of broomstick arms. Though he has come to save, to atone for sins, this Jesus’ hands are red-rubber clean, and red-rubber lifeless. Opposite (see image below), separated by a double row of chairs and a luminous clerestory window of stained glass, an illuminated bridal figure. Layer upon layer of translucent, ivory silk and white chiffon shroud the face, head, and body of the veiled wearer. The bridal train cascades to the floor of the chapel, pooling on the tile. This, the bride of Christ – the congregational body – is hung high on the chapel wall, far away from the unfocused gaze of our armless Christ-figure.

Jane Alexander, Attendant (Photograph by Mario Todeschini). Photo courtesy the artist.

Jane Alexander, Security (Photograph by Mario Todeschini). Photo courtesy the artist.

The North Transept of the church was gutted by a fire in 2001; there is no roof overhead, and the walls are marked by the damage inflicted by the fire; some forgotten garden tools – a rake, spade, a rickety wooden ladder – are propped up in a corner. One feels vulnerable to the open air, and falsely protected by the remaining grey stone walls. In the open space of what used to be a chapel floor, Alexander’s “Security”. (i) Here, Alexander has constructed an extraordinary montage: a double row of high chain-link fence topped with neat rolls of barbed wire, and scavenging bird-figures (see images above and below). In between the two rows of fencing, a foot-wide walkway scattered with sickles and machetes. These instruments are used to sustain life – tools commonly used for farming in regions without large machinery. That they can also eviscerate and erase entire populations of neighbours is not far from our minds. Scattered between these instruments, industrial-strength rubber gloves – the kind used for working with corrosive chemicals. Dirty from the rust bleeding out from the sickles and machetes, they are reminiscent of butcher’s gloves: it as if blood has stained an impervious material meant to resist and protect one from damage.

Jane Alexander, Security (Photograph by Mario Todeschini). Photo courtesy the artist.

Within the enclosed rectangle, an immaculate, brilliant green lawn, peopled by a lone, wingless vulture-figure: a stalking sentinel who cannot leave this protective enclosure. What Alexander has planted is not grass, but spring wheat. Evelyn Owen from the Museum for African Art in Manhattan tells me that the germination process, which involved soaking and leaving the seeds to rest, actually took three days before they were sown on this black rectangle of soil. (ii) Now, that black rectangle, which had a millimetre of sprouting green on the day of the opening, is a carpet of luminescent springtime, attracting a scavenging city pigeon and a red-beaked common finch. The Security Vulture has not frightened them away. They are busy pecking at the stalks of green, plucking out entire clumps with black earth still attached to shallow roots. Surveying this scene – one that encloses in safety and entraps – a watchful baboon-masked figure, its perfectly formed human fingers curled next to its foot, ensconced on a high ledge. Its gaze is fixed on far-away places.

***

It takes a lot of fearlessness to ‘be’ with Alexander’s work. The first time I encountered her sculptures, I felt I had to stand with them in truth, with compassion – with the realisation that I will probably never understand that suffering, but that the stain of it is something I live under (and together) with. This is not ‘easy’ work; these are not ‘pretty’ sculptures – though they are obviously so beautifully made. Curators may feel scepticism about Alexander’s work precisely for those reasons – that people who come to see it in a gallery may neither sit with it and take the time to understand it, nor take the time to let their thoughts be with these figures, as they require. Adding to that art-world reluctance is Alexander’s reticence towards being a spokesperson for her work. She rarely gives interviews or agrees to being photographed; when she does speak, it isn’t as a recorded statement, but as a conversation. In an email exchange, she wrote that she is “hesitant” to give statements, “in case it interferes with your response”. She adds, “Part of the value of that text for me is that it is a response to what was there rather than to me or what I might say.”

If you engage with Alexander’s work, or write about it, you must walk in and walk away with how your narratives intertwined with what you felt as you encountered Alexander’s work. That is, don’t go in with bullshit-speak. Don’t go there hoping to use art-world mumbo-jumbo as a prosthetic. Go there to engage with risk. Be real in the space of the sacred. For Americans who walk into this church, for people from this historic neighbourhood – where the initial boatloads from the tail end of the nineteenth century gave way to dozens more – perhaps it is our trans-generational inheritance, of the memory of displacement and suffering, that enables us to engage with Alexander – full of fear, yes, for what her work will surface, but grateful for communion with that small, hidden voice of history that helps us face our present with courage and conviction.

***

Endnotes.

(i) Alexander initially devised Security for the 2006 Sao Paulo biennial. Originally, the installation included the presence of a group of security guards. In later reproductions of the piece (for instance in the Goteborg Biennale (2006), but also Johannesburg (2009), Helsinki (2011), some times there have been security guards, sometimes not.

(ii) Jeremy Johnston, who assisted with the design and installation, did the research for this particular installation. Alexander says that he “laboured mightily for the best possibility of wheat in erratic weather.”

“Jane Alexander: Surveys (from the Cape of Good Hope)” is on view through July 29 at the Cathedral Church at St. John the Divine, 1047 Amsterdam Avenue, New York. 9am-6pm daily with limited access on Sundays. The North Transept is open from 9.30 am-2.30pm.

May 20, 2013

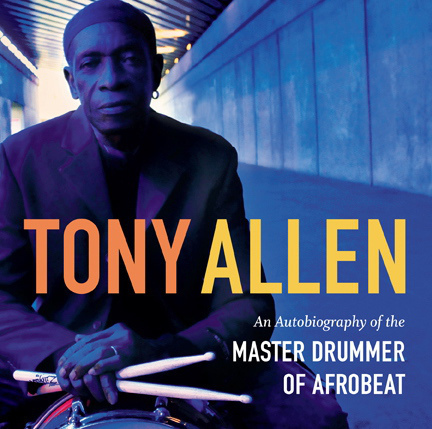

The Master Drummer of Afrobeat