Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 469

June 18, 2013

Review of Ellen Gallagher’s Tate Modern show: “Your truths are self-evident. Ours, a mystery”

The English word ‘perspective’ derives from the Latin, perspectiva, which means ‘to see through’, and as such, instantly assumes a position – a viewer and a horizon, and an in-between space that demarcates self and other, subject and object, time and space. This is our modern perspective. Once this perspective is troubled – both visually and intellectually – orientation is challenged. As Hito Steyerl writes in her essay In Free Fall – “The horizon quivers in a maze of collapsing lines and you may lose any sense of above and below, or before and after, of yourself and your boundaries.” But of course, in reality, these lines of sight (and thought) are always warped, tilted, troubled and refracted, just as a horizon is seemingly stable, but exists in an infinite flux of relativity. To ‘see through’, to gain perspective, or to ‘sight the object’ is an illusion that the artist Ellen Gallagher relentlessly plays with. She challenges the relationship between visual perception and intellectual orientation, and in her work – which encompasses painting, sculpture, film and collage – she defiantly challenges linear perspective to redress what fellow African-American artist Theaster Gates has called ‘the African non-archive’.

A deep suspicion of linearity and its accompanying perspective (and indeed, the historical impulse behind it) is clearly felt in Gallagher’s early work, where penmanship paper acts as the base upon which she develops new symbolic vocabularies, riffing on the repetitive early learning of written language. But instead of practicing letters, Gallagher’s papers are inhabited by thousands of disembodied mouths and ears, small, almost indistinguishable features that dissolve into a rough geometry from afar. In Doll’s Eyes (1992), Gallagher’s aesthetic recalls the work of American minimalist Agnes Martin. But Gallagher feels uneasy with this comparison, once again preferring to align herself with a forgotten black history, in this case, with what she terms ‘the earliest American abstraction’ – minstrel shows and the ‘disembodied ephemera of minstrelsy’. In Purgatorium (2000), Gallagher composes a vast grid of thousands of hand-drawn mouths. She describes how the paper plays tricks: “The lines of the penmanship paper sort of line up and, from a distance, almost form a seamless kind of horizon line. But, up close, you see that it’s a kind of striated, broken grid.” Nothing is as it seems. Images shift and warp according to how we position ourselves, both physically and intellectually, in relation to her work, perhaps a visual reflection of Stuart Hall’s idea that ‘identities are formed at the unstable point where personal lives meet the narrative of history’.

A deep suspicion of linearity and its accompanying perspective (and indeed, the historical impulse behind it) is clearly felt in Gallagher’s early work, where penmanship paper acts as the base upon which she develops new symbolic vocabularies, riffing on the repetitive early learning of written language. But instead of practicing letters, Gallagher’s papers are inhabited by thousands of disembodied mouths and ears, small, almost indistinguishable features that dissolve into a rough geometry from afar. In Doll’s Eyes (1992), Gallagher’s aesthetic recalls the work of American minimalist Agnes Martin. But Gallagher feels uneasy with this comparison, once again preferring to align herself with a forgotten black history, in this case, with what she terms ‘the earliest American abstraction’ – minstrel shows and the ‘disembodied ephemera of minstrelsy’. In Purgatorium (2000), Gallagher composes a vast grid of thousands of hand-drawn mouths. She describes how the paper plays tricks: “The lines of the penmanship paper sort of line up and, from a distance, almost form a seamless kind of horizon line. But, up close, you see that it’s a kind of striated, broken grid.” Nothing is as it seems. Images shift and warp according to how we position ourselves, both physically and intellectually, in relation to her work, perhaps a visual reflection of Stuart Hall’s idea that ‘identities are formed at the unstable point where personal lives meet the narrative of history’.

This is Ellen Gallagher’s first retrospective in Great Britain at Tate Modern, featuring around 100 works from 20 years. From the relative calm of the watery-blue grids that line the opening room of AxME at Tate Modern, we move through to the kaleidoscopic hot-box film installation Osedax (2009), witnessing as Gallagher jump cuts through cultural history, art history, oceanography, electronics, science fiction and Detroit techno and back again. Her cultural references are frenetic. History is an arsenal to be mined and remixed, and her work, with all the wit and wildness she can muster, plugs the perceived voids and holes in the history of black culture. The result is a startlingly complex web of narratives, a frenzy of interpretation where titles pun off everything and oblique references cut across works separated by decades, only to be summoned again two rooms later by the refrain of a disembodied mouth.

In Murmur (2003-4), a collaboration with Edgar Cleijne, a rattling projector illuminates a circular frame; plumes of steam, blue and diffuse, cut to images of animals bursting into light – combusting? Words appear on black leader – ‘…don’t be afraid, it was in our power to…’ / ‘What happened?’ but the significance of these words is dissolved by the inky light. Linguistic signs are meaningless here. A man stumbles, wearing some sort of burning yellow wig, distorted by the 16mm film stretch (an effect not dissimilar to wearing goggles under water). Gallagher is referencing the Drexciya myth, which imagines the children of pregnant slaves thrown overboard during the Middle Passage now existing as underwater creatures deep in the Atlantic Ocean. In turns, Murmur shifts between scenes appropriated and manipulated from old sci-fi films, to sequences from what look like old Westerns. Murmur dislodges time; an old future returns as a dark, watery myth reminding us of a horrific past. Gallagher has refracted history through the matter of its making; the ocean itself remoulds the form and the narrative.

This melting of subject and matter returns in the impressive two-part painting, Bird in Hand (2006; top image) and s’Odium (2006), displayed here facing each other. A pirate, or slave trader, or Herman Melville’s Captain Ahab – Gallagher is purposely oblique – stands underwater with a sprawling headpiece composed of warped faces (the cameos of drowned slaves?) and fragments of text extending outwards. He looks across at his dream, a vein-like plant pock-marked with gaps and holes recalling the eyes and mouths haunting Gallagher’s earlier works. Again, layers of penmanship paper are used, but there is no longer a semblance of symmetry. Instead, pasted fluidly are archival maps, pages from beauty magazines and dissolving layers of watercolour. On the trader’s body, Gallagher has attached shards of Himalayan rock salt, which shares the same mineral composition as the human body. An exchange of matter; an inscription of form into subject. A myth made plain. The work also draws on Gallagher’s own history – her father was born in Cape Verde, a region which greatly prospered from salt mining, and for three hundred years functioned as the heart of the transatlantic slave trade.

But perhaps the most impressive of the works exhibited in AxME is the film installation Osedax (2009), another collaboration with Edgar Cleijne. Here, in a box, two walls are occupied by projections. In one of them, a slide projector beams kaleidoscopic images, etched and distorted by the artist’s hand and magnified. Glass slides of alien life forms? The waterlogged kitenge fabric of African slaves, retrieved from the briny depths of the ocean? On the adjoining wall, a 16mm projector whirs, generating a heat which quickly becomes oppressive. In fact, the outside of the box is marked like a barnacle-encrusted whale skin – so are we inside the whale, looking out? In the film, an animated cormorant takes a dive, and a piece of music, sampled time and time again, hip-hop style, fills the gallery space. The box shifts from a whale’s belly to a sweaty club. It’s thrilling. The film cuts to an oil rig. Is it on fire? Are we actually in Sun Ra’s spaceship, watching the demise of earth from afar? A shipwreck appears on screen, and in the spirit of the frenzy of association Gallagher has nurtured throughout the exhibition, my exhausted mind returns to Hito Steyerl’s essay, to J. M. W. Turner’s The Slave Ship (1840) – a work that first disturbed the horizon line in nautical painting – to slavery and the Black Atlantic, to Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa (1818-19), to Freud superimposed onto Matisse, to Gallagher as the Odalisque, to Sun Ra’s Dandies and the golden circuit board…

It is endless.

A freefall of links, remixes, references and languages. Gallagher is relentless. But in her purposefully complex system of signs and references, the artist goes a long way in achieving her aim, which is to create a new black history that is vivid, humorous, defiant, militant, beautiful and impenetrable at the same time.

“Your truths are self-evident. Ours, a mystery” – Sun Ra.

***

Ellen Gallagher: AxME runs at Tate Modern, London, 5 May – 1 September 2013.

Ellen Gallagher: Don’t Axe Me opens at New York’s New Museum on the 16th of June — 15 September 2013

June 17, 2013

On New African Writing

The latest issue of the Journal of Postcolonial and Commonwealth Studies, which I guest edited with Simon Lewis, is devoted to African writing in the twenty-first century. Simon and I were excited to take on this task because there has been such an embarrassment of riches when it comes to the quality and quantity of recent writing from the African continent. The scholars that contribute to this issue underscore what is new and not so new about this writing, and they help us to account for some of the ways that economic, social, political, and technological changes have had an impact on modes of writing. Below is a condensed and slightly altered version of my introduction to the special issue.

***

The twenty-first century is certainly, in many ways, an arbitrary marker, but, at the same time, there have been notable changes that have led to new directions in African literary production. First, by the beginning of the twenty-first century the Internet had become widely available in many parts of Africa, especially in urban areas. While cyber cafes began springing up beginning in the mid- to late-1990s, the Internet has arguably been largely a twenty-first century phenomenon for those Africans who have been able to experience it. As Tsitsi Jaji, Keguro Macharia, and Nicole Cesare discuss in their contributions to our collection, the Internet creates both new avenues for various types of writing (from short stories, to blogs, to scam letters) as well as new modes of encountering others. And, just as importantly, it creates new forms of communities, bound together by shared interests and emotional attachments rather than shared physical spaces. Another important development in twenty-first century writing is the proliferation of prize competitions, including the Caine Prize for African Writing, a short story writing competition that began in 2000 and is discussed by Samantha Pinto in her contribution to the collection. On the one hand, we might note with a certain irony that the twenty-first century is characterized both by the democratization of African publishing via the Internet and the establishment of yet another hierarchical British prize. But, on the other hand, the presence of such opposing tugs, which sometimes produce surprisingly complementary results, is precisely what characterizes today’s African fiction. Furthermore, and just as importantly, the authors in this collection address how political changes that occurred in the mid- and late-1990s have affected the landscape of twenty-first century writing. Nigeria’s return to democracy after years of military rule, the end of apartheid in South Africa, the return to peace in Sierra Leone after a protracted civil war, and the internationalization of the LGBT movement are all events that have affected the types of writing we have seen in the first thirteen years of this century.

Rather than conceiving of the twenty-first century as a distinct or complete break from the past, we seek to understand it as part of a longue durée, a time whose overlapping multiplicities and complexities we are just beginning to discern. Achille Mbembe, in his monumental On the Postcolony, has famously described the postcolony itself as a longue durée, an “entanglement” of contradictory phenomena and temporalities that co-exist in a given age. For Mbembe the goal of theorizing the African postcolony is to “account for time as lived, not synchronically or diachronically, but in its multiplicity and simultaneities, its presences and absences, beyond the lazy categories of permanence and change.” Likewise, the essays we collected take twenty-first century writing to be about these many simultaneities.

Moreover, what becomes clear when reading these essays collectively is that new writing in Africa also transmits an entanglement of affects, affects that are not necessarily new but that do seem to take on particular forms and attachments in the twenty-first century. Pinto, for instance, mentions that Olufemi Terry’s short story “Stickfighting Days” won the Caine Prize in part because it exhibited an affect that the judges found to be new and refreshing: “it was void of sentimentality, nearly affectless.” And Kenneth Harrow, writing about Aminatta Forna’s The Memory of Love, underscores the melodramatic affect of the post Sierra Leonean civil war novel, an affect that he argues is mirrored in the widely popular Nigerian video-films (a.k.a. Nollywood) that have dominated African modes of story telling in the twenty-first century. Thus, while Terry’s story earns praise because of the way it underperforms its urgency, Forna’s seduces its readers by “over-performing” the loss, betrayal, and moral aberrations of her post-war world. But the affective options are not limited to flatness or inflation. While Cesare’s contribution discusses the performance of affective bonds created between scam artist and victim in Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani’s I Do Not Come to You By Chance, Esther de Bruijn’s essay describes an emerging Afro-Gothic genre whose blending of the satirical and the haunting operates on a uniquely disturbing affective register. What is important to note is that all of these affects are responses to the continued precariousness and uncertainty of daily life in the postcolony.

Harrow’s discussion of Forna’s The Memory of Love seems like an ideal piece to open our collection, in part because it engages directly with the concept of simultaneity that is so important to understanding twenty-first century African writing, and in part because it asks us to revise the notion of hybridity that characterized so much of postcolonial theory in the last few decades of the twentieth century. Using Forna as his primary example but also drawing on writers like Chimamanda Adichie and Fatou Diome, Harrow suggests that the notion of “in-betweenness” needs to be updated with one that accounts for the simultaneity of occupying two spaces at once. In other words, he urges us to think of the twenty-first century subject less in terms of mixing or of the creolized subject and more in terms of a doubleness that accounts for the ways that subjects often live in two worlds at once: “Whereas before the model was to be in-between, we now are living and travelling in ways that implant us in one world and then another, over and over.”

Like Harrow’s article, Marzia Milazzo’s essay examines a single novel, in this case Kgebetli Moele’s Room 207, to call for a new mode of understanding twenty-first century literature. Milazzo pushes back against critics who contend that contemporary black fiction from South Africa is colorblind, that it relegates blackness to, at best, a second-order explanation for the conditions of poverty and crime that plague black communities. Instead, she argues that race becomes an invisible, confusing category that is part of the “entanglement” and daily uncertainty that the characters experience as they try to make their way in a world that is full of both new obstacles and old power structures.

Esther de Bruijn’s article also deals with post-apartheid South African literature but from a very different angle. De Bruijn examines the nascent literary category of the Afro-Gothic and demonstrates how contemporary South African playwrights use the Afro-Gothic “as a mode of rewriting colonial history and its haunting aftermath.” De Bruijn’s essay is a self-proclaimed “testing of the term” and she aims to understand what Afro-Gothic means, what types of baggage it carries with it, and how it might be useful in understanding the legacies of racial oppression that continue to haunt contemporary South Africa.

Cesare’s article on Nwaubani’s I Do Not Come to You by Chance, a novel in which young people struggle against economic obstacles to self-realization, initiates an important discussion both about “new” responses to postcolonial precariousness and about the nature of writing and relationships in cyberspace. I Do Not Come to You by Chance is a novel that tackles an increasingly popular subject: 419 scams. 419 (pronounced 4-1-9), the penal code for financial fraud in Nigeria, has been the subject of a number of novels, short stories, and Nollywood films, but none offers up the richly layered set of emails embedded in the text of the novel that Chance does. Cesare’s reading of the novel – and the emails – opens up fascinating parallels between email scams and new African writing.

The contributions by Macharia and Jaji continue our discussion of cyberspace and focus explicitly on how it serves as a public sphere to circulate new forms of writing. Macharia’s focus is on the queer Kenyan blogging community of which he is a part. In his essay “Blogging Queer Kenya” he examines three of these blogs and argues that they intervene in the dominant narrative of homophobic Africa in important and meaningful ways. While many short stories, novels, and films often “detail loss, deprivation, homophobia, and exile to a more liberating space in Europe or North America,” blogs focus on the everyday and ordinary lives of queer Kenyans as they find love, get dressed for the day (in uncomfortably gender-normative clothes), and try to imagine what a queer future might look like in Kenya. While bloggers do document the homophobia they face, their stories differ significantly from those that are predominantly about struggles against homophobia.

Echoing some of Macharia’s comments on how to study the fleeting nature of online writing, Tsitsi Jaji chronicles the StoryTime website that began in 2007 and ended in the spring of 2012. As Jaji argues, StoryTime, one of the first of many websites to begin publishing African short fiction, had a transformative effect on the way African writing was produced and consumed across the continent and in the Diaspora. Like Macharia, Jaji argues that the democratic and interactive format of cyberspace and blogs (StoryTime is published in a blog format with a section for comments) circumvents both the traditional gate-keepers of African literature and post-colonial critics who often privilege certain types of stories over others. By establishing a platform in which anyone can publish and anyone can comment, StoryTime blurs the line between artist and audience and commentator.

Pinto’s discussion of the Caine Prize, takes a more measured view of the possibility of the new in African writing. Pinto, one of the prize’s judges, argues that even as the Caine Prize aims to promote new (and ostensibly “better”) forms of African writing, it is nevertheless entangled with and indebted to old representations and tried and true themes that figure Africa as “exotic” and “other.” If the Internet is canon-defying, the Caine Prize is canon-forming. But Pinto argues that, still, none of this prevents the prize from showcasing African stories that have fresh visions and push African writing to new frontiers.

Finally, our collection ends with four book review essays that take stock of new scholarly work and edited volumes. Annie Gagiano reviews several texts that add to the emerging “chorus of additional African women’s voices – in archived documents, testimonies, creative fiction, and academic literary criticism.” Lesley Marx’s discussion of new works of African film criticism shows that there is a tremendous amount of overlap between African filmmaking and African writing as filmmakers too grapple with new and old forms of violence while veering away from a more explicit politics of engagement. John Walsh, focusing specifically on the Francophone literature that was regrettably not covered in our main articles, glosses two important studies that demonstrate how “African and Caribbean Francophone literatures represent the transformation of boundaries that has occurred in processes of globalization.” And lastly, Neelika Jayawardane’s sweeping review of ten twenty-first century South African critical texts makes an important argument about why postcolonial critiques are still important to understanding the “new” South Africa. Although many scholars would argue that South Africa’s history is unique or exceptional and thus outside the purview of postcolonial studies, Jayawardane suggests that inequalities in literacy and education, instances of labor unrest, and endemic corruption complicate the “Rainbow nation’s” neoliberal present and can best be understood within the context of postcolonial theory. Furthermore, Jayawardane’s claim that there is an urgency in critical discussions of literature, art, and performance reminds us that writing is never an isolated event, that it shapes “debate, participation, and political action” in important and meaningful ways.

Collectively, the essays in this special issue ask what precisely is new about new African writing and examine what makes it different from what we have seen before. It is clear that African fiction has experienced a veritable boom in the twenty-first century with authors like Adichie, Teju Cole, Dinaw Mengestu, and Binyavanga Wainaina (to name just a few) taking center stage on the international literary scene. But is it also true, as Pinto suggests, that the new – she quotes J.M. Coetzee – “stubbornly fails to arrive,” that it is inevitably entangled with the old and tied to power structures that stubbornly refuse to die?

***

Here is a link to the issue’s Table of Contents. For information on how to obtain a copy of the issue, please contact Lindsey Green-Simms (lgs@american.edu), Simon Lewis (lewisS@cofc.edu), or Gautum Kundu (gkundu@georgaisouthern.edu).

* Lindsey Green-Simms is Assistant Professor of Literature at American University, Washington, D.C. She writes about African literature, Nollywood, consumer culture, technology, and gender and sexuality. Currently, she’s working on a book manuscript titled “Postcolonial Automobility: West Africa and the Road to Globalization.”

Black History in Amsterdam

Recently on a sunny afternoon, fellow AIAC-er Serginho Roosblad and I ventured out to learn more about the history of black people in Amsterdam and the contribution they made to the city since its early days. Surely there must be more to people of color in our hometown than the yearly Sinterklaas parade with his black servants. Luckily there is the Black Heritage Amsterdam Tours (BHAT) that offers guided walks on the contributions of the African Diaspora to Dutch society from the 16th century to the present. As with the celebration of 400 years of the city’s famous canals there are loads of exhibitions, series and festivals on Dutch colonial history, including on the role the Dutch East India Company (VOC) played, but conveniently no one ever mentions how the Dutch got so rich during this period.

The tour starts on Amsterdam’s central Dam Square. Tour leader and founder Jennifer Tosch explains that even today some Dutch families blatantly lie about their forefathers’ involvement with slavery. Some families, even with all the public records to prove otherwise, continue to claim that their wealth came from catching herring.

The canals it turns out were a prime location during slavery for storing as goods that came from the Far East and the New World in the grandiose buildings that were built along the waterways. Even today, the buildings that were once warehouses and now mini palaces are in the hands of families who not only traded in coffee, vanilla and other spices, but also in slaves. Some of these canal houses have been turned into museums and are open to the public. With a little probing you’ll get references to the connection the family had to slavery, although it’s not mentioned anywhere in the museum.

The presence of Africans in the Netherlands during these times is often forgotten or literately dismissed. Walking into one of the canal houses on the tour, we noticed a painting with a black servant in the background. The explanation by the painting reads something like: “The African in the picture is actually not a real person but is a symbol for Asian wealth.”

We also discovered that history lessons are best learned when you look up whilst walking through the small streets of Amsterdam. You might encounter a ‘Vergulde Gaper’ like we did. These are images of so-called Moors from North Africa. Early herb traders used performers to show how good their medicine was. They would put a pill on the tongue of the Moor performer and he would magically be healed and start dancing and singing. Not unlike the Black Petes during the annual Sinterklaas parade.

If in Amsterdam and wanting to learn something that is not in the travel books, check out Black Heritage Amsterdam Tours.

The District on Cape Town’s “Fringe”

Cape Town is changing. One recent Sunday morning I took a walk through Walmer Estate, a suburb bordering on District Six, on the edge of the City Bowl, and stopped at one of the corner stores to inquire about buying some koeksisters. Sunday mornings, in the Cape Town of my childhood, are speckled with sweet memories of syrup and sticky coconut flakes, of milky Ricoffee and the loose, crumply sheets of the Weekend Argus. This Sunday, instead, I was greeted with a quizzical look and response, ‘what’s a koeksister?’ This may have been an old corner store, frozen in time, but the old time local owner had long left; his candy menagerie now being run by a Pakistani, Bangladeshi or Somali manager. It was as if a bite had been taken out of my dreamy nostalgia.

I took a walk through Woodstock last weekend, strolling down Albert Road for the first time in my life. The Woodstock of Gympie Street, not far from where local gang leader Rashaad Staggie was brutally beaten and burnt to death, and the notorious Lower Main Road. Yet, to my surprise, I found a thronging white public perambulating eagerly up and down the road, flocking between the ‘White Market’, the ‘White Mall’, the barbers coffee shops and boutiques that appear to service a predominantly white clientele. Struck by the banality of safety that had enveloped the area, I also wondered how often this public patronised the local, established corner cafes, perhaps to enquire about koeksisters? If it was not obvious enough, the scrambling posse of black parking attendants flashing their tatty cardboard signs, desperately calling out ‘Biscuit Mill Parking’, seemed to declare that ‘here, brother, things have changed’.

Urban spaces change. Cities transform. Trying to come to terms with these reverberations around public space in Cape Town, the African Centre for Cities, through their PublicCulture Lab, and in collaboration with the District Six Museum hosted a public discussion on District Six on the Fringe: the absence of memory in design-led urban regeneration. The discussion focussed on a specific patch of ground designated The Fringe in a quarter on the edge of what is now termed the East City. The Fringe is more than a mere designation. It is a branded geographical enterprise that, it is claimed, aims to uplift and renew a deteriorating, decayed expanse of urban space on the edge of the inner city. Officials steering the project aim to re-vitalise the social and economic life of the area through re-casting it as a design and innovation district that will become a flourishing socio-economic district.

It was this set of claims that panellists came to debate and grapple with. The panel consisted of presentations delivered by Kai Berthold speaking on his project The Gentrification Relay, artist Andrew Putter speaking about his work with the Cape Town Partnership, Bonita Bennett representing the District Six Museum, and Ismail Farouk representing the PublicCulture Lab at the African Centre for Cities.

Kai presented research his been doing with the nearby Cape Peninsula University of Technology design students about the change that was taking place in the area. The barefoot, bald and blue jacketed Andrew Putter followed, presenting his case for working with the Cape Town partnership, and his work on transforming Harrington Square—the square between Charley’s Bakery and Woodheads Leather Dealers—into a vibrant public space. Spicing his monochrome PowerPoint presentation with images of the various, largely disenfranchised stakeholders with an interest in the development, he created the impression of being genuinely empathetic and deeply concerned about inclusion and empowerment. Exhibiting a heart-warming collage of images of the homeless, the transient and virtually invisible publics that occupy and move through the space, the presentation also served as a tableau of the very people that, as the history of such projects show, are the first to be cleared out. They’re just not cool enough.

The social, political and economic heart of the matter was cracked open by Bonita Bennett in her sketch of the District Six Museum’s position or at least discomfort with the notion of The Fringe. For one, she pointed out, The Fringe is an edgy, current, catchy term that immediately negates the very politics of belonging, inclusion and marginalization that imbues the very ground designated for urban renewal. If The Fringe was meant to designate the periphery, Bennett pointed out that historical narratives of former District Six residents make no distinction between the city centre and the periphery. How then does such sanitized, gimmicky language of redesignation enter into a politics of belonging and inclusion in the city? Taking into account the history of some of the first forced removals and the creation of locations that functioned as a kind of septic fringe, does the use of this language and concept serve to break with these legacies or does it merely coat them with a inclusive veneer of exposed steel and glass that continue to keep the marginalised out, visible and at a distance?

Ismail Farouk reaffirmed these issues in his presentation. Comparing The Fringe initiative and others like it around Cape Town to ventures pioneered in Braamfontein and other parts of the Johannesburg cityscape, he tried to tease out the implications of Cape Town’s inscription as a corporate city, and the imagineering that takes place around such projects. One of his poignant observations was that the fundamental problem with these developmental initiatives is their logic of time. These projects are almost always speculative property ventures that hedge against the possibility of future economic potential of a particular urban space. This is at the expense of the reality of the present and those who occupy the spaces that apparently bare economic potential. The consequences of such framings of time, suggests Farouk, are that they buy time, suspending the fulfillment of the pressing needs of the disenfranchised with the promise of immanent future redemption that never arrives. It also negates time, obscuring the histories of social life and suffering that attach to these urban spaces and render them free for acquisition by those with means. This frames one of his central questions: ‘does The Fringe provide an effective institutional framework to drive social transformation, or merely serve to further entrench legacies of segregation and dispossession that characterise the history of Cape Town?’

Times have certainly changed, and the city of Cape Town is changing. Sunday koeksisters are no more and the mean streets have lost their edge. Yet coming to terms with these transformations does not merely entail nostalgically grasping for sweet, romantic pasts and vacuously arguing for their ossified preservation. It is, instead, as Bonita Bennett pointed out, about thinking of memory, history and heritage not as décor that comes after, but as the very stuff at the heart of projects that reimagine the city. In other words, it means placing the history and politics of struggle against unjust dispossession at the centre and not on the fringe of our thinking about the future of the city and what it means to belong in post-apartheid urban space.

* Thanks to Barry Christianson for use of his pictures. Follow his photoblog.

June 14, 2013

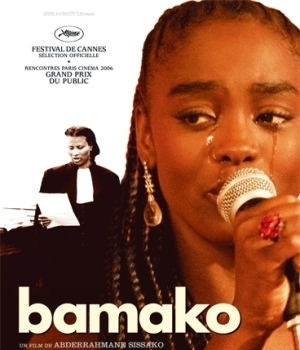

Meeting Sembène: An Interview with Abderrahmane Sissako

Abderrahmane Sissako is a Mauritanian-born, Mali-raised filmmaker whose completed cinematic training at Moscow’s Federal State Film Institute during the 1980s. The program concluded with his first film, the 23-minute short Le Jeu [The Game], which he shot in Turkmenistan to double for Mauritania. His next film was the 37-minute October, shot around Moscow and following the relationship of an interracial couple. Sissako followed these with a series of films shot around Africa. These included the 1997 documentary Rostov-Luanda, about his journey to Angola to search for an old friend from film school, and Bamako (2006), which centers on a court trial in the capital city of Mali. The trial serves to judge the impact of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund on the country’s people, and Sissako cast real judges and lawyers for the film’s court. For the role of “Le procureur”, Sissako tried to recruit influential Senegalese filmmaker Ousmane Sembène, who turned him down, and the following year Sembène passed away. But in April of 2013, Sissako visited New York City to attend the 20th New York African Film Festival at Film Society of Lincoln Center, where two of his films (Life on Earth and October) were shown — as were two of Sembène’s (Borom Sarret and Guelwaar), whom the festival honored as the “father of African Cinema”. I sat down with Sissako during his visit to New York, and discussed the production of his early films, Le Jeu and October, his thoughts on Sembène and the conflict in Northern Mali.

Do you think language is a barrier to your films being more widely appreciated?

For me, cinema is interesting and special, because it’s the language of the image. And when I think about a movie, I really think about images. For me, it means every subject of drama is universal. For example, before I got back from Russia, where I lived for more than 10 years, of course I thought in Russian for the construction of ideas. But then I lived in Paris, of course I thought in French. But it was just how to communicate. The language of cinema or any drama is universal for me.

Why did you decide to go to Russia to study film?

First, not only in this time but also now, the big problem for young Africans was we didn’t have the opportunity to choose something — not where to travel, or where to study. If we got an opportunity, any opportunity, to do something different or to go somewhere… for me, is the most important thing for a human being. When I was 19, I got the opportunity to go to Moscow to learn cinema, and only the Soviet Union gave me this opportunity. And sometimes people think, “It was because you are a Communist.” No. Any young guy is a Communist in some way. And that is not a problem, to have the concept of sharing what we have. That is important for me, this vision. But I got this opportunity to go to Moscow to learn, and it was a big chance for me.

Cinema, or to make movies, or any act of creation, is the research of yourself. It’s really important to start with what you know, what you have experienced, and to go somewhere. ‘October’ is like this. Of course I used my own experience with ambition to tell something universal. That is ambition. And also, that is a most difficult thing.

In film school, the most important thing, and the most difficult, is to have big enthusiasm. Enthusiasm is not always a good thing. And in this school, they killed the pretence. It’s really interesting when you stop pretending that art is easy. “I just need a camera to make my movie.” No. In this school they tried to explain to me, “Go slowly.” That was interesting for me. But also interesting was when I came to this school — and like today — I wasn’t very interested in seeing movies. I’m not a cinephile. I’m not this guy. When I came to Moscow, to the school, I saw maybe three or four movies in my life. And It’s a different thing to like movies, and to make films. That’s a completely different thing. And for this reason, when I discovered the world cinema — when I saw in school Cassavetes, John Ford, or Antonioni, or Bergman, or Tarkovsky — that was for me, a young guy who wanted to be a filmmaker, watching their movies on a great big screen in a big theater, that was important.

Abderrahmane Sissako

Do you think Turkmenistan doubled well for Mauritania in Le Jeu?

Yes, because it was desert, and deserts are similar. Maybe with some changes. But if you shoot a movie in the desert, you don’t need to show desert. As a filmmaker, you need to cut that, not to show desert. Because it’s not interesting in the cinema. And it’s also the most difficult thing, to shoot a movie in the desert. And I knew that before, and for me it was normal. The most important thing was to tell a story in the place where the most important thing will be my character. That is one. The second thing, the place, was also important, because I didn’t get the opportunity to shoot my movie in Mauritania. And Turkmenistan was the only opportunity to do that. And also, the people from there look like Mauritanians, because they are desert people. And it was interesting, but it was my first movie.

What was your approach to filming October, and creating its interracial dynamic?

When I finished Le Jeu, it was my school movie. I was surprised, because when I showed this movie, it was in Cannes in 1991, and also it was bought by the French TV company, Canal J. I was very surprised. The movie went to different places, and different festivals. And I got the opportunity, and also money, to do another thing where I would have control. I decided to do that, and I decided to make October. Because the story of October is the story of many many people. Not only African people who studied in Russia, in the Soviet Union, but it’s the story of any couple. When you think the love story is not possible for this reason, love doesn’t need a reason. But if the reason exists, it will kill something inside of the people. So, if it’s because she’s not really close to my country — if she comes from Texas and I’m from Africa — something always happens in the human being. But most important in this time was the only reason for me to leave this country [Russia] where I spent more than 10 years: I know I’m not accepted in this society. It’s sometimes hard to say that. It’s not like if you live in New York, where everybody can be a New Yorker if you decide to be that. Not in Moscow for an African guy. And to live in this place where everyday I have the feeling, “It’s not my place. I need to leave, to go somewhere to make cinema to make it.” For that, I decided to make a movie. And after I finished this movie, I remember my editor who cut my film, she was a very nice woman — the kind of woman who exists in Russia: simple, beautiful, “like Momma” kind of woman — and also, very cinematographic. When we finished, we edited, and we put some music in to see how the movie would look. At the first screening, she was there with me. Also my DP, who was Tarkovsky’s DP, Georgi Rerberg. He was a very close friend. When we saw the movie, she told me, “Abderrahmane, I don’t know what happened. But only now do I really understand that maybe your life was really hard in this place.” She hugged me, and she cried. It’s really, really interesting. I learned a lot in Russia. It was hard, but I like the people.

What was your relationship with Ousmane Sembène?

I met him in 1991. It was in Burkina Faso. I was of course very young, and I came from Moscow with Le Jeu. I’d go every night with my friend to the nightclub. We left the nightclub around 5-6 o’clock in the morning, and I came back to the hotel at 7 o’clock. Before I sleep, I prefer to go for breakfast. And Sembène was there early with Tahar Cheriaa, who was the big critic from Tunisia. So I came up to him to say hello, and he was there with 3-4 people. He said, “This guy is really interesting. He woke up very early.” He thought I just woke up. And he said, “I’m sure this guy can go very far.” But he never knew that I just came from the nightclub. That was really funny. And he heard about Le jeu, but he didn’t see it. But he was very interested in me because I studied in Russia, and he also went to Russia. And before this moment, I was accepted at FESPACO at Sembène’s table, where the next youngest person was maybe 60 years old. But I was one of the young filmmakers who Sembène accepted. You can come to say, “Hello”, and he tells you, “Please have a seat.” Of course I would say, “No, no. Thank you, Sembène.” If he insists, you can sit. And it was very interesting, but he played the role of the father. It means he doesn’t need to tell you your movie’s good, or this movie’s not good. No. If you are a young filmmaker, he accepts the art of every young filmmaker. That was the very strong character of Sembène. And the last really important meeting I had with him was when I prepared Bamako. I decided to have Sembène play the role of the “Le procureur.” I called him in Senegal, and on the phone I said, “Sembène, I need to talk with you. How can I meet you?”

He said, “The only possibility is to take a plane to come to me in Dakar.” It was Friday. I said, “I can take the plane Tuesday.” He said, “OK, please come.” And I went. But before, I sent the script to Clarence Delgado, who was Sembène’s assistant. He’s a fantastic guy, a very good person, and a good first assistant. So I sent my script to Clarence to give to Sembène before I came. And I came, and I went to Sembène’s office with Clarence. I said hello to Sembène, and he said hello. He said, “Please have a seat. And Clarence, go out.” And he said, “Clarence tells me you want me to play the role of ‘Le procureur’ in a movie.” I said, “Yes.” He said, “No, it’s not possible. I never act in the movie. But if you want, I can propose a different actor.” And I said, “Yes, of course, Sembène. You can propose it. But I’m not sure if I will take another actor.” It was finished, but we talked, and I went back the next day to Bamako. The role was played by a Malian actor [Magma Gabriel Konaté], and it had very few words. But the figure of Sembène, especially in this movie, for me was very important. Just to see Sembène, and listen what happens, the Sembène figure… it was sad.

What’s your take on the conflict in Mali?

That is a big question. What happened in the North of Mali, before the war when France came, was really something terrible. Not only for Mali, but for the whole region. The reality was for me not six French people who were kidnapped and were somewhere. No. The kidnapped were more than 300-400,000 people from Timbuktu, from Gao, from Kidal they were kidnapping with the system, the vision of the war — the fanatics who say, “You cannot play music. You cannot play football.” If you steal an old bicycle, because you are poor, they can cut off your hand or your foot. That is for a human being today the most terrible thing. Maybe for this reason, my next movie is called “Timbuktu.” The situation in Mali between North and South is a development question with poverty, of course. If you don’t have the strong political vision on independence day to change something in all parts of the country — if you don’t put in education, if you don’t construct roads — something will happen anywhere. It’s not only the situation that it’s a little White, and a little Dark. No. It’s more complex than that for me.

* Christian Niedan blogs at Camera in the Sun; you can read more of his writing on African cinema here.

South Africa has a “Pro” Twerk Team

Welcome to AIAC’s (first?) NSFW post. South Africa has a “pro” twerk team. In what could have been an amazing Pan-African exchange, they came up short and better called themselves professionals. Full stop as I reluctantly throw them a dark haze of shade.

I guess everyone outside the southern United States just discovered what twerking/freak dancing/winding is. (All different, but bear with me.) I’m not hating on the SA Twerk team because they are twerking. I have been twerkin’ for nearly all my life, and it’s a time honored pastime for me and several of my close friends. Better, this seemed like a great opportunity to see twerking from a new, non-American perspective.

Nope, I’m disappointed because this twerk team is NOT TWERKING. Which is unfortunate, because the origins of twerking, like most great things, lie in Africa. My homie and twerk extraordinaire, Sawdayah, pointed out some quick references are Makossa or Makassi (Cameroon), Mapouka (Cote d’Ivoire), Kwasa Kwasa (DRC).

Twerking is not simply dizzying butt movements meant to arouse any guy watching. It’s not tight camera shots that make you feel like you’re at an awkward strip club. It for damn sure isn’t absent of technique, rhythm and continuous movement and energy. And that’s not what the Pro-Twerkers are giving the camera here.

I’d like to give you, the reader, and y’all, the SA “Pro” Twerkers a quick primer on how to ride the beat.

First, here’s the very talented Atlanta Twerk Team.

To be able to twerk effectively, what you’re doing is pulling in all the techniques learned from a variety of dance forms, and being able to manipulate your hips to create a façade of impossible moves. It is serious and actually requires years of practice and talent. Gymnastics, belly dancing, salsa can all be incorporated, thus, allowing you to recognize a pro when you see one.

If you grew up in the American south, you’ve probably been twerking all your life. At family reunions as a 6-year old. At middle school dances outside the glance of the chaperone. It’s not about someone else projecting their own sexual issues onto you. Here are some classics to practice with. I’ll start with Juvenile:

Next up Project Pat:

The lyrics are gross, but thank you Three 6 Mafia, UGK, and Bun B for your bass lines. Then, you know how to play with the layers of rhythms. Ciara in “Ride” is fantastic.

Can you do that? Yes? You are talented. One of the members of the SA Pro Twerkers immediately complains that they get a lot of haters who dismiss them as simply doing sexual dancing. Another goes on to say that they have all types of different techniques and rhythms they throw on their hips. First, girls, your haters have a point and second, just no. You are not professionals. What you are giving is a sexual shock factor, not real twerking talent. If you want it to be an authentic, Southern style twerk, elevate above the basic “just-found-out-I-got-a booty” spastic gyrating and become one with the beat. Learn the basics, as seen below:

Improvise and earn the professional title. Until then, please practice.

June 13, 2013

The battle over the 27th of May in Angola

On Monday May 27th, the Political Bureau (BP) of the ruling MPLA condemned the political appropriation of “o 27 de Maio” (the 27th of May) by people who had no direct involvement in the events or their effects and who distort the truth of what happened (to paraphrase Jornal de Angola’s summary of the official declaration). The MPLA’s BP did not act affirmatively. They were reactive and censorious (this is how they roll). I’ll explain in a minute why the MPLA wants to control what happens so much, but in a nutshell the date recallsan attempted coup by members of the ruling MPLA shortly after independence (some dispute that description) and the subsequent purge that followed that event in the days, and for another two years, after May 27, 1977. What upset the MPLA even more this year was that a nw social movement, the Movimento Revolucionário, organized a demonstration to remember the victims of 27 de Maio as well as Alves Kamulingue and Isaías Cassule – two activists who disappeared last year after organizing veterans and presidential guards in a mass demonstration for pensions in arrears on May 27, 2012.

On Monday at the demonstration, protestors were beaten up – one, Mandela, so severely that he couldn’t move, was refused treatment at four Luanda health clinics. Emiliano Catumbela is still in custody, has been beaten by order of the provincial commander of the National Police, accused of attempted homicide, and denied access to his lawyer.

In a June 1 column in Semanário Angolense, speaking to the 36th anniversary of the murderous events of 1977, Reginaldo Silva noted that this was the fourth official statement ever. In 2002, the most significant came when the MPLA-BP recommended that state institutions and Angolan society should work to ensure that all those who where in any way involved in the events related to the 27th of May 1977 should not experience difficulties in the free exercise of their constitutional or legal rights. Something many victims and families of victims claim is still not the case. No official holiday or monument exists for “o 27.”

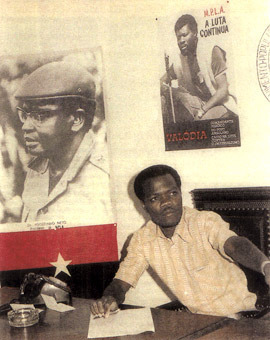

But back to the larger meaning of the original 27 May. At the time of the coup, President Agostinho Neto described the attempted coup and the difference in political opinion it represented as ‘fraccionismo’ (factionalism) bent on destroying the MPLA and the young Angolan nation already in the throes of a civil war backed by the imperialists. Nito Alves, the former Minister of the Interior, a former leader in the struggle for independence in the 2nd Military Region, and José ‘Zé’ Van Dunem, a former political prisoner from São Nicolau prison, were the supposed masterminds of the coup in Neto’s reckoning and the leaders of a dissident opinion within the MPLA.

Nito Alves

Estimates of the numbers (many of them young people) killed in Luanda and other cities in the aftermath range from 12-80,000. Thousands were jailed and tortured. The state’s newly formed secret information service (DISA), modeled on Salazar’s PIDE according to some, dates to these terrifying days. Many describe the settling of personal rivalries and petty vendettas in the chaos. All agree it put an end to a vibrant, healthy, culture of political debate within the MPLA. Youthful engagement in politics was crushed or turned to vile ends.

27 de Maio serves as a powerful cautionary tale: one that parents use to keep their children from protesting or getting involved in politics at all (opposition politics, that is), warning that it will bring ruin and death. The activist Adolfo Campos was kicked out of his home, his parents were so scared. Ana Margoso, a UNITA member, had the specter of the 27 de Maio raised as a warning to not speak out publically. My best friend in Luanda calls in sick when she knows there is a demonstration of any kind. It has been responsible for untold amounts of self-censorship. This fear is politically useful to the MPLA. It kept many people away (even if mightily curious) from the first demonstrations organized for March 7, 2011 – just meters away from the radio station where some of the events of 27 de Maio had taken place.

It’s simultaneously sotto voce and hyper-visible.

Angola’s President, José Eduardo dos Santos, in 1977 was a member of the party Political Bureau and was appointed to lead the Commission of Inquiry into the 27 de Maio. A number of victims of re-education camps were sufficiently ideologically recuperated and have proven their personal loyalty to the President and to the party to now serve in some of the highest ministerial posts in the government – among them the Minister of Culture and the Minister of Planning.

Others who survived torture and imprisonment are renowned journalists – Reginaldo Silva, João Faria, and the recently deceased João Van Dunem (brother of Zé Van Dunem and the long time head of the Portuguese language service of the BBC in London) – and founding members of opposition parties like Bloco Democrático (BD): Nelson Pestana, Justino Pinto de Andrade, and Filomena Vieira Lopes (whose brother was killed in the purge). BD published an analysis of 27 de Maio days prior to the 36th anniversary, drawing a straight line from those events to the authoritarianism of the current leadership, the violence of the state, and the intolerance of political debate.

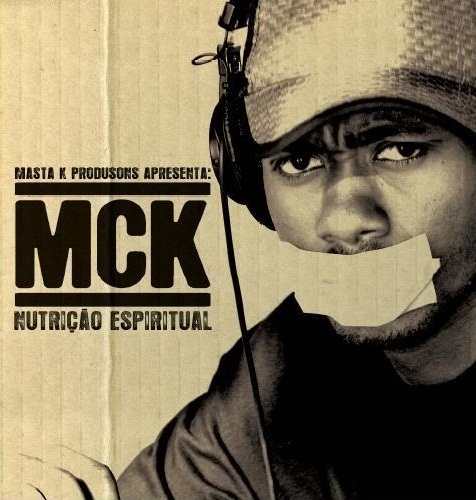

Echoes of Artur Nunes (a musician killed in the aftermath of 27), the child of an Angolan mother and North American father, o espirtualista?

Most intriguing have been the ways in which 27 de Maio has been taken up by protestors as a symbol of unfinished business, the promise of independence, and the hopes for an Angolan nation in which justice, equality, and democracy have not been met. One young activist has taken the name “Nito Alves.” Last year, when I was in Luanda for a conference on kuduro, a protest by veterans of the civil war occurred on the 27th of May. This was a courageous, symbolic act in which veterans protested not having received their pensions for many years on a date when the last mass demonstration, also by party members (many from the Army’s elite 9th Brigade), in 1977, resulted in mass murder. Kamulingue and Cassule, the organizers of that protest, disappeared on May 29, 2012 and have not been seen since.

Though the English historian David Birmingham wrote about it in African Affairs in 1978 (with his usual flourish and eye for the odd detail, like Alves’s connection to Sambizanga football club – nod to all you Football is a Country fans for the ways in which sports has consequences), little was written subsequently. Until recently … mainly after the signing of the peace accords in 2002 (see the geek’s reading list at the end of the post).

But since these books in Portuguese have been published and since the Associação 27 de Maio, founded in the early 2000s began to advocate for official recognition, historical investigation, and a truth and reconciliation commission of sorts for the 27th of May by victims, families of victims, and friends of victims, things have begun to shift.

In 2002, the MPLA took advantage of the peace accords signed in Luena to suggest that these old ghosts might too be settled. But still no official monument or holiday or recognition exists. And no death certificates have been issued or bones returned for burying. Issues material and spiritual hang in the balance.

In the long wake of the peace and the failure of the government, still dominated by the MPLA, to distribute its dividends to the average Angolan we have seen the consolidation of power in the executive and a growing tide of protests by youth and by opposition parties. We’ve reported on some of that here, here, and here.

I first heard about 27 de Maio from the great musician Teta Lando when I interviewed him in his shop in Luanda’s baixa in May 1998. He told me that three wildly popular musicians of the early 1970s were killed in the purge. David Zé, Artur Nunes, and Urbano de Castro were all close to Nito Alves, all denizens or frequenters of the musseque Sambizanga. He surmised that not only their friendship with Alves but their popularity and visibility among Luanda’s young population was a threat to the exiled leadership, still fresh to Luanda after some fourteen years away fighting the anti-colonial war and, with the exception of Agostinho Neto, much less recognized.

Theories about what caused the 27 de Maio and what it means abound: a thermidor in the revolution, unresolved race issues within the party, the contradictions of class, overzealous youth, etc.

One thing is clear, without an official reckoning, speculation and conspiracy theories will continue.

Official coming to accounts are for the Angolan government and people to decide.

We give you Urbano “Urbanito” de Castro – the troubadour of urban youth and their dreams of an independent Angola – dipanda para todos (independence for all)!

For those interested in further reading in both Portuguese and English here’s the crib list: Among the first was novelist José Eduardo Agualusa’s 1996 Estação das Chuvas (The Rainy Season), also available in English translation. More recently and all non-fiction: Dalila Cabrita Mateus and Álvaro Mateus, Purga em Angola, 2005; Miguel Francisco, Nuvem Negra, 2007; and Américo Cardoso Botelho, Holocausto em Angola, 2008. The Howard University based historian of Angola, Jean-Michel Mabeko Tali has at least a chapter in his two volume study Dissidências e Poder de Estado: O MPLA Perante si Próprio, 1962-1977 (2001) dedicated to the subject and a new chapter on it in an edited volume: “Jeunesse en armes – Naissance et mort d’un rêve juvénile de démocratie populaire em Angola en 1974-1977” (Karthala: 2012). And Lara Pawson, a one time BBC correspondent in Angola, shocked that no one ever talked about it when she lived in Luanda, that no other journalists, like Victoria Brittain, during the civil war years, or Michael Wolfers, around the time of independence, who had written about the contemporary period even mentioned it, published this article in 2007 and is currently working on a book.

Germany’s African “Big Five”

On the occasion of the country’s first “development day” last week, the German ministry for economic cooperation and development launched a new campaign to educate Germans about what development policy is—or more accurately what the “new German development policy” looks like. What the campaign actually teaches us is that there is nothing new about German development policy and that it looks like the confirmation of clichés, recycling of old ideas and promotion of a neocolonial mindset. Superimposed on the map of the African continent, the “Big Five”—a lion, elephant, buffalo, leopard, and rhino—represent the five goals of the ministry’s work: to reduce poverty, secure natural resources, and promote biodiversity, education, and human rights. The relation between the big five and the five goals? No idea. In order to “justify” the use of wild life on the poster, the ministry cooperated with the WWF.

German civil society organizations have already reacted to the campaign and criticized the poster for linking German development policy to colonial safaris—a hunt for exploitable objects—, which suggests a one-sided intervention on the African continent, without regard for its people, to the benefit of the West. The NGO Berlin Postkolonial demanded the minister of economic cooperation and development to resign, as he disqualified himself for the office as minister with the launch of this campaign. “What is new about it,” asks Mnyaka Sururu Mboro of Berlin Postkolonial in a press release by AfricAvenir, “that the Germans in Africa ‘fight poverty’ and at the same time ‘secure natural resources’ and want to promote their growth? That they assume that with hunting and photo safaris they will ‘preserve biodiversity’? What is new about it that Germany wants to export the country’s own ideas of ‘democracy’ and models of ‘education’? What’s new about it that Europe speaks of the ‘protection of human rights,’ which it permanently denies to African refugees?” Both NGOs, Berlin Postkolonial and AfricAvenir, seek to change common depictions of Africa in Germany and promote a critical engagement with Germany’s colonial past.

You want to know what’s actually new about it all? The minister, Dirk Niebel’s, picture on the lower left hand side of the poster. This is uncommon in federal agency’s PR campaigns, which led to accusations that Niebel would use the 3600 posters all over Germany for his personal election campaign for the upcoming national elections in September. His party, the Free Democrats, have lost much support in recent months due to the lack of leadership and solid policies. Maybe Niebel hoped to get some election boost from the big five. The headline of the German daily newspaper Die Welt read: “Niebel embarks on the election campaign with Africa’s big game.”

To celebrate Africans on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the African Union and not the Germans, Mansour Ciss Kanakassy of Laboratoire Déberlinisation published an alternative map of the African continent, on which the “big five” are African leaders that fought for freedom and contributed to African unity: Amilcar Cabral, Thomas Sankara, Cheikh Anta Diop, Kwame Nkrumah, and Haile Selassie.

June 12, 2013

The new and improved Africa is a Country is here

June 12th is a momentous day in African history. To take two events: in 1964, Nelson Mandela — whose passing now seems imminent — and seven other African National Congress leaders were sentenced to life in prison for terrorism by an Apartheid South African court. Twenty nine years later, in 1993, three years after Nelson Mandela was released from prison, an election took place in Nigeria, the results of which was annulled by a military junta led by Ibrahim Babangida, who has since reinvented himself as a democrat.

But to more mundane and fleeting matters. June 12th, today, is also the day when after weeks of promising you a new design, we’re back with a brand-new and improved blog. This is a big day for us. We had to transfer our files from WordPress (we can talk about that frustrating process another time) so that took time. Don’t worry, the whole archive is here too (hopefully we’ll transfer the older archive of Leo Africanus, the blog’s original name, over here too at some point), so you can go back and read your favorite posts. Expect some glitches (minor ones we promise have to do with formatting). You can also read the blog in blog view: either click here or type this URL into your search engine: http://africasacountry.com/latest/. Now bookmark that.

Finally, this redesign is the work of Jepchumba, graphic designer and digital content creator (she’s also behind the excellent AfricanDigitalArt blog) whom we owe big time. So for today, find your way around the new site as tomorrow we’ll be back with our usual snark and cheerfulness.

May 29, 2013

Africa is a Country is getting a makeover

If you wondering what this stripped down design on the blog is all about, we’re getting a new look and will be back soon. Meanwhile, you can visit or sign up to our Facebook and Twitter pages till then or stare at this pic of me chasing some kind of pheasant (UPDATE: Neelika says it is an Egyptian goose) in Kirstenbosch Botanical Gardens in Cape Town a few years long time ago.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers