Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 463

July 17, 2013

A Season in the Congo

Political theatre isn’t just about depicting reality and expecting the audience to interpret it, coldly and rationally, as a call to some political action. That’s what Bertolt Brecht seemed to think anyway. “Political theatre,” he wrote, “must stimulate a desire for understanding, a delight in changing reality. Our audience must experience not only the ways to freePrometheus, but be schooled in the very desire to free him.” Even at its most impassioned, its most didactic, Brecht’s drama is an aesthetic experience, and an emotional one too.

Watching the new production of Aimé Césaire’s ‘A Season in the Congo’ (Une Saison au Congo) at the Young Vic theatre in London, I couldn’t stop thinking of Brecht. This incredibly rich, subtle and moving play depicts the last couple of years of the life of Patrice Lumumba; mostly concentrating on his short time as Prime Minister and the circumstances (much disputed) leading to his death. Lumumba is played by Chiwetel Ejiofor, a British actor born in London to Nigerian parents.

The story of Lumumba told onstage ends in the same way as it did in real life; though most of the attention is on the Congolese context and the machinations of President Kasa-Vubu and Colonel Mobutu. Further upstage on a raised platform, European and American bankers scheme in the background, represented by grotesque caricatured puppets, that to my mind recalled the figures of Hitler and his generals in Brecht’s ‘Schweik in the Second World War’. On the same part of the stage Lumumba goes to the UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld and disembodied heads representing the USSR and USA argue with each other over the theatre floor. Down below, some of the audience sit at small tables and outside furniture, set up to look like a bar in Leopoldville (Kinshasa), drawing us in to the action and evoking the life of the Congolese capital at the epoch of independence. The staging is constantly inventive; towards the end, a long table of people, greedily eating their fill like the top table at a wedding, suddenly stand up and become the firing squad that executes Lumumba.

When Belgian paratroopers drop on Katanga province an actor walks across the stage carrying a model plane and the theatre is filled with the sound of its engines. Small objects – I guess toy soldiers – drop from above attached to paper parachutes. Perhaps my description doesn’t do it justice, but the effect on the audience is to feel a sudden shifting of perspective, so that one is not simply observing Leopoldville, one is there, one is “schooled in the desire”, as Brecht would say, to see Congo free of Belgian influence.

These effects of props, models, lighting, staging, sound, and movement constantly give one this sense. Sometimes director Joe Wright shows you into a nightclub in Leopoldville, sometimes suspending you over the entire city or the entire country while vultures (puppets manipulated by the cast) ready themselves to pick over Lumumba’s corpse.

Césaire’s language is beautiful; he has an amazing ability to slip between tones and registers, introducing moments of poetry into the characters’ speech. Most of these lines go to Lumumba, and Ejiofor (whose performance, incidentally, is brilliant) has the right intensity and personality to carry off the act, switching lightly between persuasion, anger, humour, seduction, doubt and introspection. At one moment, Lumumba is imploring his close friend Mokutu to understand the importance of liberation politics to the continent. He holds out his right hand, flat, fingers together, and invites the other man to look:

“Do you ever think about Africa? Look here. No need for a map hanging on the wall – it’s written on the palm of my hand.”

That’s the kind of image that comes alive when you hear it spoken, that impresses itself into your mind and achieves the same effect that the planes and paratroopers did earlier. In the dark of the theatre, I held out my hand in front of me, low down in my seat, arched my thumb out to make West Africa, wiggled my fingers for Cape Agulhas, and imagined the lines on my palm making the Congo River.

‘A Season in the Congo’ runs until 24 August at the Young Vic. Here’s the trailer:

July 16, 2013

South African NGO challenges dominant ideas about how to be a man

Even though the overall media attention for the matter has faded these past few months, women in South Africa continue to be brutalized, harassed, assaulted and murdered by the country’s men (mostly in the domestic sphere by known perpetrators) — we wrote about that here. A few weeks ago, black lesbian woman Duduzile Zozo, was raped and murdered, found with a toilet brush inside of her. She was buried last Saturday.

Obviously, the task of eliminating these many forms of violence rests not only on the shoulders of women, legislators and police.

The simple fact that all forms of violence in South Africa have a male face tells us there’s something fundamentally wrong with ideas around manhood. It challenges us to take seriously the meanings that are attached to ‘being a man’ in South Africa and interrogate the ideas around man- and womanhood that young boys grow up with.

For those men who actively accept their responsibility to end the assaults and make the country safer for girls and women, there’s plenty to do. Not so much by urging men to protect their wives and keep their hands off our women; this excludes lesbian women and reinforces the idea that women need male protection. In a counterproductive twist, these kinds of messages are more likely to consolidate the stereotypes that underpin the violence rather than alter or challenge them.

Understanding what does not work, however, doesn’t answer the question what men can do. It’s a thorny one, especially because the socially constructed ideas about what it means to be a successful man, a competent provider, a responsible mother or a respectable woman are so deeply ingrained into society that much of the behaviour that surrounds these norms appear as perfectly normal and innocent. We learn to read a courteous arm around a woman’s waist as an affectionate gesture, an insistence on paying her share of the dinner bill as gallant, and unsolicited street-commentary on women’s bodies as compliments. Women who deviate from the norm by loving other women, rather than men, are considered ‘funky’, naughty, exotic or liberal at the (very, very) best and deserving of rape, suffering and death at worst. It all alludes to ideas of women as possessions, property and trophies, prepared, ready and available to be chased and courted by men.

So next to keeping their own pester-potential in check, how should men commit to reducing the daily threats that their sisters, mothers, nieces and friends face? How to step out of those stereotypes and become structural partners for gender justice?

Sonke Gender Justice in Cape Town is an organization that made it a priority to figure out how to go about this. Wessel van den Berg, who is the Global coordinator for Sonke’s MenCare program, and Joshua Ogada, the NGO’s communications manager, took some time to sit down with us and share their views on how men and boys can engage.

Realizing that women empowerment stands no chance without women leaders, South Africa’s post-apartheid governments have done a great job in appointing women to leadership positions in the public (political) space. Yet this arena of empowerment stands in bitter contrast to the wider professional sphere, which is dominated by (often white) men and the domestic space, where most of the violence against women takes place. Whilst often overlooked, the latter is a key space for men to actively challenge harmful stereotypes.

Wessel explains: “Currently the professional workspace is constructed as a masculine space, where masculinity has been associated with competition and self-realisation. This space has also been given a much higher importance than the home space. The home space has been constructed as a female space that is less important, that involves household related work,and includes care for children. In this dichotomy men are cast as financial providers and women as homemakers. People that bridge this divide succeed in dropping the gendered nature of the two spaces, and move freely between and inside the two spaces, regardless of their sex or gender. Both spaces also attain equal value in the partnership. Men and women share care or household work, and financial responsibilities or career development. In this scenario the patriarchal stereotype of the male protector/provider is no longer relevant. Ideally sweeping the floor or washing dishes would then be a signal of a deeper equality and consensus between partners, rather than the token attempt at gender equality that it often becomes.”

So bridging the divide between the work and the domestic space is an important one. What else? According to Joshua, it’s important to understand that gender equality is not something that men grant to women. Neither is it something that will be achieved by apologizing for male behaviour by marching. Instead, he explains, it is about not standing in the way of it and making an effort in understanding how that can be done in a structural and meaningful way. For starters, that means to stop condoning harassment. Joshua explains: “If your friend shouts at a woman, speak out to him. Don’t condone this normalized behaviour. Instead, take responsibility for the violence and challenge the stereotypes that lie at the core of it. This is not about protecting the women, it is about eliminating the threats they face. Root out the threats rather than focus on protecting the victim. Building bunkers in a war doesn’t end a war. Ending the war will.”

Whilst essential to transformation, such individual shifts are not enough. Broad-based gender progress requires concerted campaigns to mobilize South Africa’s many communities. According to Wessel, the different levels that organizations could work at include “community based education focused on service providers such as social welfare offices, schools and clinics, or working with media like radio and television to demonstrate shifts in social norms and to improve policy by holding government accountable for delivery, and challenging weak policy frameworks”.

Sonke’s One Man Can programs, for example, target young boys through outreach at schools. Working from the belief that fathers ought to be aware of their status as a role model and an example to their children in how they deal with women, their Fatherhood program interrogates and challenges meanings of fatherhood by involving both fathers and sons in discussions about the meaning of gender and role models.

To read more about Sonke’s vision and strategy, visit www.genderjustice.org.za or follow them on Twitter and on Facebook.

New Work by Julie Mehretu: The Unruly Rush of the City

It is as if Julie Mehretu has boxed some corner of a great, rambling city, shaken it, and spilled the contents out onto a canvas. Girders and struts, and the faint memory of the structure and reason that once guided their making, lies broken. Now, on the canvas, these once straight lines are contaminated with the inevitable growths and architectural warts that bloom as cities age – the shacks, kiosks, burnt out cars, potholes; the mess of city life.

In these huge, monument-sized canvases that hang in White Cube Bermondsey, Mehretu’s work addresses the unreason of the city, its visual noise, and in her deft fusion of geometric drawings and the endless abstractions she paints and draws upon them, they sprawl like the cities themselves, descending into a kind of visual madness that reflects the peculiar, frenetic condition of urban life.

In Kabul (2013), delicate, architectural pencil drawings seemingly self-multiply, over and over. Mehretu overwhelms their rationale – the faint, straight lines re-accumulate so many times that the buildings they once depicted drown beneath, only discernible from a corner here and there, or a window that survived the brambling swarm of Mehretu’s markmaking that grew out of its foundations, like some parasitic shrub.

Beside it hangs Invisible Sun (algorithm 2) (2013), a cloud of grey and black acrylic. Perhaps if Henri Michaux, long into a Mescaline binge, had tried to paint a city, it would have looked something like this. The painting rushes with movement; wide smeared brush strokes shroud the canvas in a thick fog. It brings to mind the atmosphere of cities not yet cleaned and filtered by European pollution laws; like a walk through downtown Nairobi that results in black snot and dust in every crevice, while exhaust pipes cough plumes of black smoke, hungry for cheap petrol.

Mehretu captures the unruly rush of city life in a terribly convincing way, and visually mimics something of its anti-logic. And yet, there is a paradox that troubles her work.

At White Cube, the architect David Adjaye has designed an altar-like chamber composed of four walls (image above), dramatically lit, angled and facing towards one another. Here hangs the Mogamma: A Painting in Four Parts, which was first shown at dOCUMENTA 13. The complexity and detail of the quadtych is immense. The title refers to Al-Mogamma, the name of the all-purpose government building in Tahrir Square, around which swarmed the protests of 2011, which eventually ousted Hosni Mubarak. In these four paintings, Mehretu has taken plans and drawings of countless city squares and layered and abstracted them beyond recognition. Once again, her deft markmaking transforms layer upon layer into a thriving mass – flashes of neon might be traffic lights, lines and arrows could be the campaign map of an oncoming army, or it could almost be a photograph of a post-apocalyptic terrain, perhaps from Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. But their home, in this cathedral-like gallery space, contradicts the public histories they summon.

These are large, monumental pieces; a collectors dream, a princely addition to any private collection. As Karen Rosenberg in the New York Times pointed out, ‘In 2007 Goldman Sachs commissioned an 80-foot mural from Ms. Mehretu for the lobby of its new building in Battery Park City’. Mehretu has been embraced by the financial sector, yet the spaces of revolution she depicts – and which form the bulk of her recent work – seem to demand a messier, less precious home.

There is an uncomfortable juncture between the expensive curation and the exciting and vivid urban sprawl that her paintings and drawings explore. And a tension, too, in the co-option of her work by large banks and institutions, whose recent apocalypse she does not directly address, yet which hovers here, like an uncomfortable spectre, for they surely have had a huge impact on the ‘formation of personal and communal identity’, so central to her artistic interest. Instead, the exhibition skirts these more challenging questions. The canvases depict a public zone dichotomous to that of their own surrounding, brimming with a sense of the life of a city which we can never really know or measure, whose politics is alive but oddly incubated, but which exists here in some compelling form, in Mehretu’s scrum of marks and gestures.

Julie Mehretu ran at White Cube, London from 1 May – 7 July 2013. All images by Ben Westoby courtesy White Cube.

July 15, 2013

South African Autobiographies: Between Memoir and Self-Help

AIAC’s Neelika Jayawardane’s review of South African memoirs is included in the inaugural issue of Symposium, an innovative new online magazine and blog intended to bring academic research, views, and debates onto the public floor – in much the same way that, say, South Africa has come to regard political science and sociology as disciplines intrinsic to its ability to conduct sound self-analysis. Although “academics are often caricatured as out-of-touch elitists,” writes Helen Fessenden, the journalist behind the magazine, she saw the proliferation of blogs by academics as a signal that these conversations were more than ready to step out of isolation.

In “Memoirs Take a Daring Turn in South Africa” Neelika takes a look at the intersection between memoir and self-help: how personal accounts of the apartheid and post-apartheid years take on a therapeutic role that is both painful and necessary.

Below is an excerpt:

The apartheid state was obsessed with controlling the national narrative, as well as the stories that people told, believed, and internalized about themselves and others. But since the Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings of the mid-1990s, South Africans’ impulse to reveal how their personal lives and the political intersected has revised many apartheid-era fictions. Memoirs have taken on special powers, destabilizing long-held myths about neighbours that one had maintained at a legislated distance, and challenging attempts to whitewash the past. Individuals’ stories have become a legitimate aspect of making new national history.

With the fall of apartheid came the first personal accounts about South Africa’s liberation movements, particularly from the African National Congress (ANC). As media scholar Sean Jacobs of The New School notes, these volumes “tended to gloss over the intra-party struggles and uncertainty within the movement, favouring instead a heroic narrative about triumph over adversity.” These works included Ahmed Kathrada’s Memoirs; George Bizos’ Odyssey to Freedom; Barry Gilder’s Songs and Secrets, and Nelson Mandela’s Long Walk to Freedom. In his final work, Nelson Mandela: Conversations With Myself, the former president, all too aware of the machinery intended to paint him as an icon of an equally faultless political struggle, attempts to deflect such attempts by revealing his all-too-human failings, and detailing how he worked towards becoming a formidable political strategist – rather than a saint.

In the 2000s, many new memoirs run headlong against the concerted push by ruling ANC elite to fashion a more favourable political story while it tries to cling to power. As the philosopher and political scientist Achille Mbembe puts it, “the re-emergence of official culture” in South Africa means that its leadership “seeks to tame and domesticate its population by establishing official distinctions between the accepted and the unacceptable, the permitted and the forbidden, the normal and the abnormal.” He also points out that the “re-emergence of official culture has coincided with the intellectual decay of the ruling party.” In other words, an elite’s attempts to control discourse often coincides with the growing understanding that its unquestioned ascent is over, and that it is about to lose control of the population.

This disjuncture in the history of the ANC is bookmarked by the arrival of new memoirs that challenge official versions of history. They mark the passing of a moment when there was collective hope for a victorious revolution that would make citizenship more equitable. In some ways, this deluge of South African “counter-narratives” – stories that run against official history — signals the wreckage of that utopian dream.

Despite my overall optimism about the power of memoirs, I have to remind myself they have their limitations. I worry that narratives chronicling how black South Africans overcame debilitating inequalities encourage views about their “intrinsic” ability to endure and be resilient in the face of apartheid history and neoliberal violence. Such rhetoric is often used, sometimes inadvertently by well-meaning people, to maintain the disenfranchised in their place by reinforcing a violent brand of exclusion through a fairytale that maintains that they can “rise up” if only they worked harder. Far from questioning apartheid stereotypes, the long-suffering nature of the downtrodden is offered as a form of triumphalism. Furthermore, memoirs that fall into either the “Struggle Activist” or “The Good White Man” category may gloss over the complexities and the deliberate, violent separations that are all too real in the “negotiated settlement” that is South Africa today. By leaving out so much, these memoirs mirror the desired, official narrative of the new South African state. They re-inscribe the idea of a progressive, united triumph over apartheid, devoid of internal divisions or repressions.

Read the full piece here.

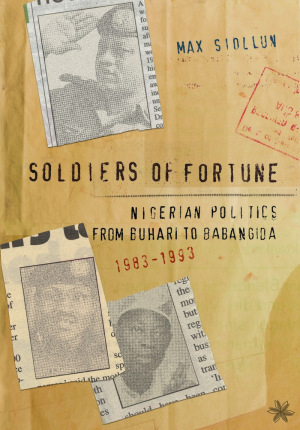

Nigeria’s Soldiers of Fortune

In his new book, Soldiers of Fortune, the historian and commentator Max Siollun argues that the years 1984–1993 — a period of military rule in Nigeria — ‘crafted modern Nigerian society.’ Siollun is well qualified, having published a book on oil politics in 1970s Nigeria. Here he is interviewed about the book by Anthea Gordon.

In an article published in 2011 you said it was “time to sex up Nigerian history.” Could you explain more about what you mean by this and how you think Soldiers of Fortune achieves a dynamic, evocative style?

When people think of a history book, they do not anticipate that it will give them the same suspense filled experience of reading a murder-mystery or suspend-belief fantasy of a Harry Potter novel. I want to present Nigerian history as something more than a mechanical rendering of dates and facts.

My books have the feel of a fly on the wall reconstruction, or an action packed thriller. I do not just want the reader to know what happened. I also want to take the reader on a journey through the dizzying twists and turns, and cast of characters in Nigeria’s history: Ibrahim Babangida, Mamman Jiya Vatsa, Muhammedu Buhari, MKO Abiola, Dele Giwa, Gideon Orkar, Gani Fawehinmi, Ebitu Ukiwe, Sani Abacha etcetera. Many people also do not know the exploits of some of these familiar names before they entered the national limelight. There are also other people who are not as famous as them, but who the public do not realize made pivotal contributions to Nigeria’s history.

I want readers to feel as if they personally met these people, were physically present when crucial decisions and conversations took place, and experienced all of it.

I do not change the facts. I recount what happened, albeit with devastating detail, warts and all. There is no slow ponderous lead up. The book gets to the point. In the first chapter alone, there are gun fights, a change of government, multiple coup plots, betrayals, a senior officer being shot dead, the President being deceived, and we are introduced to several young men who went on to dominate Nigeria’s political landscape for the next two decades.

Who are your writing influences? The style of the book seems to draw on fictional as well as historical writing (for example in its detailed, hour-by-hour exposition of the kidnapping of Dikko it has elements of detective/crime writing) — how much do you think a historian can and should draw on other forms of writing?

I try not to box my writing into any one genre. My books are about history and politics. However I also want fans of crime, fiction, and thriller books to read and enjoy them. This is why the book contains the reference material you would expect of a history book, but also the dramatic twists and turns, and suspense you would expect of a John Grisham or Robert Ludlum book.

If we talk about classical literature, Nigeria’s history reminds one of a Greek or Roman tragedy in multiple acts, with a revolving cast of characters. There is a lot of Caesar like back-stabbing.

Soldiers of fortune is presented as a challenge and alternative to previously written ‘hagiographic bibliographies’ of key figures of the period such as IBB (Babangida) and Buhari. How did you go about piecing together the realities of such prominent figures? Did you ever feel the need to hold back or self-censor — especially as some of the figures you discuss are still alive and in government positions?

At times I felt like a detective while researching the book! A lot of painstaking hard work, sleepless nights, cross-referencing of sources, and travel was involved. I tried to access as many primary and secondary sources as possible, in order to get a panoramic view of everyone profiled.

Sometimes the value of a book is not just what is in it, but also what the author leaves out. I had to have an in-built filtration process to leave out material that might titillate, but not inform. I was very careful not to let the book become a tabloid, or praise singer. At the same time I did not assassinate people’s character either. I present the facts, and allow the reader to make up his or her own mind about the things they read.

In the above-mentioned article you also say that Nigeria should ‘turn our national characters into ‘stars’. In Soldiers of Fortune, how have you ensured there is a balance between portraying a political figure as a dazzling personality and critically analyzing their behavior and actions? Is it possible to really make a ‘star’ of Babaginda or indeed Buhari?

It is important to understand that political figures are not one-dimensional heroes or villains. Like all human beings they have positive and negative character traits. I humanise them, and make the reader see them for what they are: creatures of flesh and blood that sometimes make good or bad decisions.

For example, many people tend to think of Babangida synonymously with the June 12, 1993 election annulment or the Structural Adjustment Program. However, there is little appreciation of the man’s personal charisma and disarming ability to charm nearly everyone he meets. Have you noticed that people who have met Babangida rarely criticize him?

The main protagonists in Nigerian history should be brought to life. I want the reader to understand that the people they are reading about are more than mere names on a piece of paper. I would like readers to emotionally invest in the history and lives of Nigeria’s former leaders. Readers can do that if I show them that these people are idiosyncratic humans with families, emotion, rivalries, envy, and problems just like everyone else.

The book reveals how the years 1984–1993 ‘crafted modern Nigerian society.’ Can you explain a bit more about the effects of this period on the Nigerian psyche which can still be seen today? How can understanding the period make a difference to contemporary Nigeria, especially to young people who were born after that period?

The military ruled Nigeria for almost thirty of its first forty years after independence. Modern Nigeria cannot be understood without examining its past under military rule. Nigeria’s identity was constructed by the military. The constitution, Senate, House of Representatives, all thirty-six states, and governing structure are all products of military rule. During Nigeria’s first 47 post-independence years, every change of government was effected by the military.

Nigerians do a lot of soul searching and often ask why the country is the way it is. All these controversial topics that people worry about and discuss, such as: corruption, Sharia, the Niger Delta, zoning, ethnicity, power rotation…none of them arose in a vacuum. The roots for many of these controversies sprouted during military rule.

The origins of, and answers to, many of Nigeria’s problems are buried in the graveyard of its past. Only by digging up those buried secrets can the country learn lessons from them, heal, and move on.

The book is a sequel to your first work Oil, Politics and Violence so it has been in the pipeline for a while. Was there anything you encountered in the process of writing the first work or in the research for Soldiers of Fortune that affected your approach to the second?

I listened intently to readers’ feedback about Oil, Politics and Violence. Most readers enjoyed the thriller pace and detail. So I retained those elements in Soldiers of Fortune too. One of the toughest parts was that Oil, Politics and Violence set the bar really high. So it was quite a daunting task to ensure that I maintained those high standards in Soldiers of Fortune.

My intention is for Soldiers of Fortune to become a “one stop shop” compendium and ultimate reference point for Nigeria between 1984 and 1993. That is why I dotted the book with several tables and a massive “library” in the Appendices. For example, the Appendices contain an itemization of every single cabinet minister, military governor, and AFRC member that served in the Babangida government. I want Soldiers of Fortune to be the “go to” place for anyone that wants to check any prominent controversy, fact, event, person or date in Nigeria between 1984 and 1993.

You use an interesting range of sources, including personally conducted interviews with witnesses to certain incidences and military figures. In a period notorious for its (as you say) ‘code of silence’, how difficult was it to organize such meetings? How important did you feel it was to conduct such interviews in order to try and break through some of the lack of clarity around events of the period?

The story of how I wrote these books could itself be a book! I had to travel to meet or speak to people at odd hours, and sometimes in strange locations too! Many people I spoke to approached me directly. I did not have to go looking for them. There are many “silent witnesses” to Nigeria’s history. For some reason they do not always share their first-hand experience, so uninformed gossip and wild conspiracy theories often fill the information vacuum.

Having studied in the UK at the University of London, and lived in the US, do you feel you have a more objective/outsider perspective on the period? How did your experience of living abroad alter your perspective and approach when writing Soldiers of Fortune?

Definitely, my eclectic background helps me to look at the issues from different vantage points. One reviewer of Oil, Politics and Violence said I “successfully checked [any ethnic biases] at the door” and that I combined “the dispassionate objectivity of the outsider with the nuanced knowledge of the insider.” I have tried very hard to do all those things so I am glad that someone else picked up on it.

I can simultaneously care about Nigeria and be passionate about its issues, without allowing myself to take sides. I think I can be an “insider” in that I do not just mechanically recount events, but instead I can analyse and contextualize them using first-hand knowledge of Nigeria. However, living abroad also allowed me to take a step back and not allow my judgement to be clouded or biased by being too closely immersed in these events.

The book is dedicated to the memory of your father, who died while serving as an employee of the Nigerian federal government. To what extent did your personal history inspire and influence the writing of the book? In order words, why the interest in military history?

My father was a history and politics buff. When one of his closest friends found out that I had written a book on Nigeria’s history, his first words were “like father, like son.”

When I later heard how his friend reacted, I actually took the fact that he thought I am like my dad as a huge compliment. My father kept extremely detailed diaries that chronicled not just his own personal life, but also his observations on macro current affairs too. There is an entry on virtually every day in his diary. His diary was so consistent that it can be used to reconstruct every day of his working life. He documented his thoughts on everything from family issues like the day I was born, to political events like the assassination of the head of state.

He spent a lot of time thinking about, and discussing many of the core issues we have in Nigeria today. One watershed moment for me was when as a student, I opened one of his old trunk boxes for the first time. I discovered that he read the same books as me, and was very detailed at the recording events he observed.

Reading my father’s diaries taught me the importance of committing memories to writing. What may seem like mundane personal recollections to one person might have wonderful historical or nostalgic importance to future generations. If we do not record our history, each time a Nigerian dies, a piece of Nigerian history will die and get buried with them.

Why do you think it’s important for young people to understand their history? What do you think can be done to encourage young people to engage with the past and to make study of the past a prominent part of curriculum and national discourse?

Nigeria’s young generation did not create most of Nigeria’s problems, but they inherited them, and have to deal with them. I am not sure they can devise solutions for Nigeria’s problems unless they know the events that created those problems in the first place.

Nigerian history has been something of an elephant in the room. Succeeding governments deliberately impose a “history blackout” on Nigeria’s younger generation. Governments de-emphasized history in the classroom as they tried to brush the country’s past under the carpet in an attempt to foster reconciliation. However, the “pretend nothing happened” method has not worked, and actually caused more bitterness and conflict. I think teaching young people how terrible misunderstandings led to bloodshed can steer them away from repeating the mistakes of the past.

Nigeria’s history has not always been happy. However, it has been consistently dramatic. It is rare for Nigeria to go more than a few years without a “near death experience”. Most countries go through cliff-hanging and tense crises every decade or so. In contrast, Nigeria has cataclysmic hold your breath and close your eyes dramas every few years.

I am not sure that young Nigerians appreciate just how drama filled their history is. Hollywood script writers could not have written a more conspiratorial thriller with as many plot twists, friends turning on each other, corruption, gun battles in city centers, dazzling women, and rags to riches billionaires.

Technology and social media has been excellent at engaging young people via avenues familiar to them. My website has allowed me to make history accessible to young people through textual, visual and audio sources. It is all there for them to access using any method they like.

* Soldiers of Fortune is published by Cassava Press on Monday, July 15th, and will be available (in hardback) from www.cassavarepublic.biz, www.konga.com, www.buyam.com.ng and www.jumia.com.ng as well as bookshops in Nigeria.

The Promised Land

Last Thursday we blogged about Israel’s intention to deport African asylum seekers back to unnamed African countries in exchange for “benefit packages”–basically weapons. Now comes the news that last night Israel repatriated–for the first time–14 Eritrean asylum seekers back to their country. This has been confirmed in the last few days by detainees at Saharonim prison–near the border with Egypt–who have contacted the Israeli Hotline for Migrant Workers. The 14 Eritreans, who spent the last year in the prison, will be returned to Asmara. According to detainees, the Eritrean Ambassador in Israel was supposed to escort them on their return.

The Israeli authorities haven’t confirmed the information yet. However, there have been reports in the last few days that the Israeli Administration of Border Crossings, Population and Immigration has been getting imprisoned Eritrean asylum seekers in Saharonim to sign “willful emigration” documents that allow deporting them from Israel. This process also goes against the United Nations’ stance on the matter and follows the Attorney General of Israel’s decision to approve the procedure three weeks ago.

According to the Hotline for Migrant Workers, detainees are repeatedly told by Ministry of Interior representatives at the internment camps are their only way out it to go back to Eritrea, and that otherwise they will spend years in prison.

Starting from June 23, about 350 of Saharonim detainees went on hunger strike to protest their detention. The Israeli Prison Authorities made extensive efforts to end the mass hunger strike and succeeded on their mission on June 30.

In a letter by one of the hunger strikers that was published in Hebrew last week, he described their encounter with immigration authority officers during the hunger strike:

We were prosecuted and victimized in our country and we didn’t have democracy. We were not able to live in peace. Many among us were tortured and raped in Sinai. When we reached this democratic state of Israel, we didn’t expect such harsh punishment in prison and we still don’t know which crime it is that makes us suffer for such a long time in this prison. We lost all hope and became frustrated by this situation so that we ask you to either provide us with a solution or send us to our country, no matter what will happen to us, even if we have to endure death penalty by the Eritrean regime.

At the end of the hunger strike, more Eritreans decided to leave the Israeli prison. According to the hotline, about 200 Eritreans have already signed an agreement to go back to Eritrea, but the detainees have been told that the Eritrean Embassy is able to arrange passports to only to 15 people a day and therefore the process will be gradual.

There are some 36,000 Eritrean asylum seekers (out of a total of 50,000 African asylum seekers) in Israel. Hundreds of them are being held in Israeli prison facilities under the Anti-Infiltration Law from last year which allows imprisoning of asylum seekers for three years without trial.

The promised land

Last Thursday we blogged about Israel’s intention to deport African asylum seekers back to unnamed African countries in exchange for “benefit packages”–basically weapons. Now comes the news that last night Israel repatriated–for the first time–14 Eritrean asylum seekers back to their country. This has been confirmed in the last few days by detainees at Saharonim prison–near the border with Egypt–who have contacted the Israeli Hotline for Migrant Workers. The 14 Eritreans, who spent the last year in the prison, will be returned to Asmara. According to detainees, the Eritrean Ambassador in Israel was supposed to escort them on their return.

The Israeli authorities haven’t confirmed the information yet. However, there have been reports in the last few days that the Israeli Administration of Border Crossings, Population and Immigration has been getting imprisoned Eritrean asylum seekers in Saharonim to sign “willful emigration” documents that allow deporting them from Israel. This process also goes against the United Nations’ stance on the matter and follows the Attorney General of Israel’s decision to approve the procedure three weeks ago.

According to the Hotline for Migrant Workers, detainees are repeatedly told by Ministry of Interior representatives at the internment camps are their only way out it to go back to Eritrea, and that otherwise they will spend years in prison.

Starting from June 23, about 350 of Saharonim detainees went on hunger strike to protest their detention. The Israeli Prison Authorities made extensive efforts to end the mass hunger strike and succeeded on their mission on June 30.

In a letter by one of the hunger strikers that was published in Hebrew last week, he described their encounter with immigration authority officers during the hunger strike:

We were prosecuted and victimized in our country and we didn’t have democracy. We were not able to live in peace. Many among us were tortured and raped in Sinai. When we reached this democratic state of Israel, we didn’t expect such harsh punishment in prison and we still don’t know which crime it is that makes us suffer for such a long time in this prison. We lost all hope and became frustrated by this situation so that we ask you to either provide us with a solution or send us to our country, no matter what will happen to us, even if we have to endure death penalty by the Eritrean regime.

At the end of the hunger strike, more Eritreans decided to leave the Israeli prison. According to the hotline, about 200 Eritreans have already signed an agreement to go back to Eritrea, but the detainees have been told that the Eritrean Embassy is able to arrange passports to only to 15 people a day and therefore the process will be gradual.

There are some 36,000 Eritrean asylum seekers (out of a total of 50,000 African asylum seekers) in Israel. Hundreds of them are being held in Israeli prison facilities under the Anti-Infiltration Law from last year which allows imprisoning of asylum seekers for three years without trial.

July 12, 2013

Weekend Music Break 45

We took the week off last week so we’re coming back at you extra strong today. For those of you trying to stay warm this winter and those of you keeping it cool this summer we’ve got ten tracks that’ll give you what you need.

Kicking it off is Brooklyn-based Rwandan Iyadede. It’s been far too long since we’ve heard her uniquely entrancing vocals. In the new video for “Not the Same”, invincible Director-DP team Terence Nance and Shawn Peters capture visually the ghostly dissonance that sets in when a relationship fades into a masquerade. Radiant, even in melancholy, Iyadede, delivers her trademark lyrical introspective brilliance over an eclectically electric beat.

Under the warmth of the Senegalese sun Lam’in Tukkiman finds himself stranded in an open plain amongst a herd of cattle and a majestically lithe angel. Blending hip-hop flows with rock rhythms, the track’s Wolof and English vocals are well accompanied by a symphony of strings.

Kenya’s most innovative multimedia creators Just a Band have tapped into their collective nostalgia for classic television once again to create the video “Dunia Ina Mambo”, one of the strongest tracks off their latest record, Sorry for the Delay. The crackling VHS effect never looked so good.

Ethiopian-Israeli Ester Rada makes the transition from actress to singer with the title track off her latest EP, “Life Happens”. Blending soul with Ethio-Jazz, Ms. Rada will be one to pay attention to. She keeps it funky in the video with stylish bright colors and scenes filled with clones that could be mistaken for fine art.

Brazilian electronic music producer Boss in Drama features MC Karol Conka, in their collaborative track “Toda Doida”. The upbeat song is coupled with an equally feel-good video that exudes positive vibes.

Filmed by the fantastically prolific producers at Amplificado TV, this live video captures members of the South African band BLK JKS performing their song “Tselane”. Opening with footage of the massive scale of Johannesburg, the video finally hones in on the performance and demonstrates how captivatingly intimate the city can be.

Off his new EP “Tokyo”, French rapper Joke spits the lyrics to the track “Louis XIV” with a smooth, slow confidence. Behind the grand, ecclestical visuals, a church choir provides the backup for Joke’s flow. The rythmic dancing of a veiled woman bids the viewer to make a confession.

A relative newcomer to the popular Ghanaian music scene, Bisa Kdei had been producing scores for the Gollywood (think Nollywood) film industry, when his song for the recent cinema release Azonto Ghost became a surprise hit (plus it has an incredible movie poster). Kdei’s hypnotic neo-Azonto song “Over”, featuring the star of the Azonto Ghost film Lil Win, demonstrates that Kdei’s success is no fluke.

Short and sweet, Blitz the Ambassador’s video for his new track “Dikembe” shows him repping Accra on the streets of Rabat. Amidst scratching organs and wailing guitars Blitz also make sure to show love for fellow musicians Nneka, Baloji and Sarkodie.

Speaking of Nneka: her “Kangpe” seems to have slipped through the cracks. Shot in Côte d’Ivoire, the video reveals how someone that is ostensibly pious can moonlight as an abusive big man. But if you dey Kangpe, the thing en no fit kill you, it go make you strong.

Weekend Music Break, N°45

We took the week off last week so we’re coming back at you extra strong today. For those of you trying to stay warm this winter and those of you keeping it cool this summer we’ve got ten tracks that’ll give you what you need.

Kicking it off is Brooklyn-based Rwandan Iyadede. It’s been far too long since we’ve heard her uniquely entrancing vocals. In the new video for “Not the Same”, invincible Director-DP team Terence Nance and Shawn Peters capture visually the ghostly dissonance that sets in when a relationship fades into a masquerade. Radiant, even in melancholy, Iyadede, delivers her trademark lyrical introspective brilliance over an eclectically electric beat.

Under the warmth of the Senegalese sun Lam’in Tukkiman finds himself stranded in an open plain amongst a herd of cattle and a majestically lithe angel. Blending hip-hop flows with rock rhythms, the track’s Wolof and English vocals are well accompanied by a symphony of strings.

Kenya’s most innovative multimedia creators Just a Band have tapped into their collective nostalgia for classic television once again to create the video “Dunia Ina Mambo”, one of the strongest tracks off their latest record, Sorry for the Delay. The crackling VHS effect never looked so good.

Ethiopian-Israeli Ester Rada makes the transition from actress to singer with the title track off her latest EP, “Life Happens”. Blending soul with Ethio-Jazz, Ms. Rada will be one to pay attention to. She keeps it funky in the video with stylish bright colors and scenes filled with clones that could be mistaken for fine art.

Brazilian electronic music producer Boss in Drama features MC Karol Conka, in their collaborative track “Toda Doida”. The upbeat song is coupled with an equally feel-good video that exudes positive vibes.

Filmed by the fantastically prolific producers at Amplificado TV, this live video captures members of the South African band BLK JKS performing their song “Tselane”. Opening with footage of the massive scale of Johannesburg, the video finally hones in on the performance and demonstrates how captivatingly intimate the city can be.

Off his new EP “Tokyo”, French rapper Joke spits the lyrics to the track “Louis XIV” with a smooth, slow confidence. Behind the grand, ecclestical visuals, a church choir provides the backup for Joke’s flow. The rythmic dancing of a veiled woman bids the viewer to make a confession.

A relative newcomer to the popular Ghanaian music scene, Bisa Kdei had been producing scores for the Gollywood (think Nollywood) film industry, when his song for the recent cinema release Azonto Ghost became a surprise hit (plus it has an incredible movie poster). Kdei’s hypnotic neo-Azonto song “Over”, featuring the star of the Azonto Ghost film Lil Win, demonstrates that Kdei’s success is no fluke.

Short and sweet, Blitz the Ambassador’s video for his new track “Dikembe” shows him repping Accra on the streets of Rabat. Amidst scratching organs and wailing guitars Blitz also make sure to show love for fellow musicians Nneka, Baloji and Sarkodie.

Speaking of Nneka: her “Kangpe” seems to have slipped through the cracks. Shot in Côte d’Ivoire, the video reveals how someone that is ostensibly pious can moonlight as an abusive big man. But if you dey Kangpe, the thing en no fit kill you, it go make you strong.

Weekend Music Break

We took the week off last week so we’re coming back at you extra strong today. For those of you trying to stay warm this winter and those of you keeping it cool this summer we’ve got ten tracks that’ll give you what you need.

Kicking it off is Brooklyn-based Rwandan Iyadede. It’s been far too long since we’ve heard her uniquely entrancing vocals. In the new video for “Not the Same”, invincible Director-DP team Terence Nance and Shawn Peters capture visually the ghostly dissonance that sets in when a relationship fades into a masquerade. Radiant, even in melancholy, Iyadede, delivers her trademark lyrical introspective brilliance over an eclectically electric beat.

Under the warmth of the Senegalese sun Lam’in Tukkiman finds himself stranded in an open plain amongst a herd of cattle and a majestically lithe angel. Blending hip-hop flows with rock rhythms, the track’s Wolof and English vocals are well accompanied by a symphony of strings.

Kenya’s most innovate multimedia creators Just a Band have tapped into their collective nostalgia for classic television once again to create the video “Dunia Ina Mambo”, one of the strongest tracks off their latest record, Sorry for the Delay. The crackling VHS effect never looked so good.

Ethiopian-Israeli Ester Rada makes the transition from actress to singer with the title track off her latest EP, “Life Happens”. Blending soul with Ethio-Jazz, Ms. Rada will be one to pay attention to. She keeps it funky in the video with stylish bright colors and scenes filled with clones that could be mistaken for fine art.

Brazilian electronic music producer Boss in Drama features MC Karol Conka, in their collaborative track “Toda Doida”. The upbeat song is coupled with an equally feel-good video that exudes positive vibes.

Filmed by the fantastically prolific producers at Amplificado TV, this live video captures members of the South African band BLK JKS performing their song “Tselane”. Opening with footage of the massive scale of Johannesburg, the video finally hones in on the performance and demonstrates how captivatingly intimate the city can be.

Off his new EP “Tokyo”, French rapper Joke spits the lyrics to the track “Louis XIV” with a smooth, slow confidence. Behind the grand, ecclestical visuals, a church choir provides the backup for Joke’s flow. The rythmic dancing of a veiled woman bids the viewer to make a confession.

A relative newcomer to the popular Ghanaian music scene, Bisa Kdei had been producing scores for the Gollywood (think Nollywood) film industry, when his song for the recent cinema release Azonto Ghost became a surprise hit (plus it has an incredible movie poster). Kdei’s hypnotic neo-Azonto song “Over”, featuring the star of the Azonto Ghost film Lil Win, demonstrates that Kdei’s success is no fluke.

Short and sweet, Blitz the Ambassador’s video for his new track “Dikembe” shows him repping Accra on the streets of Rabat. Amidst scratching organs and wailing guitars Blitz also make sure to show love for fellow musicians Nneka, Baloji and Sarkodie.

Speaking of Nneka: her “Kangpe” seems to have slipped through the cracks. Shot in Côte d’Ivoire, the video reveals how someone that is ostensibly pious can moonlight as an abusive big man. But if you dey Kangpe, the thing en no fit kill you, it go make you strong.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers