Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 453

September 13, 2013

“The New Black” Films

Creatively Speaking is a monthly curated film series offering a diverse forum that highlights independent film by and/or about people of color. It is curated by Michelle Materre (a New School media studies professor) in partnership with the new cinema and event space, My Image Studios (MIST), in Harlem. They also produce a regular podcast. A few days ago, the podcast focused on what they term “The New Black,” where they discussed three new films of the Black Diaspora: Alain Gomis’ “Tey” (coming to the US and reviewed before for this blog by Jonathan Duncan), Andrew Dosunmu’s “Mother of George,” and Shaka King’s “Newlyweeds.” Listen here. The podcast is definitely worth a listen and includes interviews with the filmmakers themselves. Whether or not there is truly serious momentum building for black film (or specifically films by African directors) here in the US remains to be seen, but there is something to be said about the sheer volume of highly-anticipated films made by black filmmakers or about communities of color being released in the coming weeks.

Just look at the lineup of this year’s Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF). At this point, most people have heard all about films like Steve McQueen’s “12 Years a Slave” (and the strange questions McQueen was subjected to at a press conference at Toronto), the film adaptation of Chimamanda Adichie’s “Half of a Yellow Sun” (first reviews are lukewarm) and even “Mother of George”.

However, there has been less chatter about films like French-Senegalese director Gomis’ beautiful and meditative film “Tey” (Today), which stars the formidable American hip hop artist and poet, Saul Williams, and tells the story of a man’s last day of life spent wandering through the Senegalese capital, Dakar. I’ll have more on “Tey” and “Mother of George” to come, but for those who are interested, “Mother of George” starts a New York City run today at the Angelika Theater in the West Village.

Meanwhile, the folks in charge of Tey’s distribution in the US are attempting a slightly different and hybridized model. They are trying to have truly community-driven releases throughout the country. The film premieres at MIST (in Harlem’s Little Senegal area) on Sunday, October 6. It will run in New York for 2 weeks, before traveling to New Orleans, Atlanta, Nashville, DC, LA, Oakland, San Francisco, and Vancouver.

Full disclosure: I’ve been working with the film’s distribution company, BelleMoon Productions, to do some outreach and promotion. Regardless of my association, I still think they are doing something really exciting with the film’s distribution, whereby those equipped and interested can co-host a screening of the film in their community.

Under Nelson Mandela Boulevard—A Story About Cape Town’s Tanzanian Stowaways—Summer 2012

Towards the end of 2012 Moses was arrested and charged under the Immigration Act for being in the country illegally. He called to say he was being held in Pollsmoor Prison, then weeks went by in which I heard nothing. Moses was the last of my good contacts in the beach boy community. In the course of the year Adam had disappeared in the Blue Sky and Daniel-Peter had been arrested and sent to Lindela repatriation camp in Pretoria. He called one night to say they were finally sending him back to Tanzania, and that he was happy about it, because he had grown tired of the beach boy life.

For every beach boy who disappeared, however, there seemed to be two new arrivals. Occasionally a Christian group would hand out free foodpacks on the Parade, and you really caught a sense of the beach boy numbers then. In excess of a hundred predominantly Muslim Tanzanian youths would sit patiently under Edward VII while the Christians linked hands around them and babbled in tongues. Afterwards the queue they made for food would go halfway across the Parade, never diminishing because after receiving and stashing a Christian food pack each beach boy would once more join the line.

It might have been from a sense of fatigue but it seemed to me that the new arrivals were different: younger, angrier, more drug-addled. I decided to quit the beach boy areas for a time to go in pursuit of answers to a range of back-logged questions, like: why had the presence of the stowaway community gone virtually unremarked by authorities, ethnographers and journalists since the first Tanzanians began arriving in the mid-90s? The city police, dock officials, border guards and the Cape Town City Improvement District’s ironically-named Displaced Persons Unit (ironic in the sense that the unit is responsible for clearing the city of settlements of homeless people), were all well aware of the community’s existence. But quite why these arrayed forces of order and gentrification had not scrubbed the beach boys out of existence remained a mystery, until a shipping agent I was in contact with sent me a circular on the subject of stowaways from the former Western Cape director of Immigration, Tarieq Mellet.

“Stowaways,” wrote Mellet, “board ships in foreign ports and make their way to South Africa…where there is a perception that it is easy to find their way to staying permanently.”

The South African state, wrote Mellet, “does not accept that foreign Stowaways originate in South Africa.”

In two years of interacting with the beach boys I had not met a single one who arrived in South Africa in a ship. Moses’ journey overland was fairly typical: the only details that varied from beach boy to beach boy pertained to the precise route taken, the borders jumped.

Leaving the circular half read I wrote back to the shipping agent in amazement.

“The state is sorely misinformed,” I squawked, to which he responded, “No, it isn’t. Your government knows perfectly well that the stowaways originate from South African port cities, but if they admitted as much they would be responsible for the costs of repatriation, which range between R15’000 – R90’000 per stowaway.”

I continued reading the circular and there was Mellet, just as the agent had explained, insisting that: “the responsibility for their removal from South Africa remains with the Master of a vessel and the Ships Agents. No stowaway will be landed,” wrote Mellet

Returning excitedly to my correspondence with the agent I wrote, “So it’s therefore quite understandable that some captains are returning stowaways back on to South African soil disguised as dockworkers. An extraordinary set of circumstances!”

“Or just a very ordinary set,” he wrote back.

The weekend the Obama’s visited Cape Town seemed as good as any for a return to the beach boy areas. It was late June and for weeks the city had been Obama befok, to quote a colleague, and what with the shuddering of Chinook rotors on test runs to the city from the US destroyer at anchor in False Bay, and the constant wailing of “blue-light brigades” on the city’s highways, even documented, paid-up citizen were starting to feel a little hunted, a little ring-fenced.

I ventured down to the Grand Parade on the Friday afternoon before the vaunted visit and found it unusually devoid of beach boys, no doubt because the place was crawling with cops and security guards. By the Golden Arrow bus shelters at the northern end of the Parade I spied Suleiman Wadfa, a solidly built and very dark-skinned Tanzanian with a disarming gap between his front teeth, who likes to be called P Diddy. He was hurrying away from the fixed food stalls, looking concerned.

“The police are arresting everybody. E-V-E-R-Y-B-O-D-Y. It’s because Obama is coming. There are already 50 or 60 beach boys in Caledon,” he said, not stopping to talk.

The holding cells at Caledon Police Station are often crammed to capacity when dignitaries visit. Using a city vagrancy by-law the city’s Displaced Persons Unit rounds-up as many undocumented immigrants as they can lay their hands on, only releasing them when the event or visit has passed. Diddy was on his way out of the city at the double step.

“The bridges are no good, the police are coming there too,” he said.

“I’m going to ‘the Kitchen’, nobody comes there.”

I’d often heard Adam talk of ‘The Kitchen’, and knew it was somewhere between the N1 highway and the railways lines heading into the city, at the far end of the Culembourg industrial site. Try as I might, though, I’d never been able to find it.

“I’ll drive you,” I told Diddy, an offer he couldn’t refuse. He directed me down Main Road into Woodstock, and then down Beach Road in Woodstock’s industria to Tide Street, so-named because the sea had lapped against the shore there before the land reclamations of the 40s that created the foreshore. We came to rest beside a dumpster in the yard of an oil-recycling company.

“Through here,” said Diddy, working his broad chest through a slender gap between two bent palisade struts. We crossed the railway lines, which were overgrown with Purple Loosetrife, and came before two railway tunnels under the N1, running to the Duncan Dock. The graffiti on the visible tunnel walls was so dense it looked several inches thick, and beyond a few metres the walls went pitch black. Smoke was billowing out of the nearest mouth.

“Wait here,” Diddy commanded when we were about 20 meters away. He continued in alone.

A Chinook thundered by overhead, followed by another, and when I looked down Diddy was walking towards me, accompanied by a slender, lighter-skinned person, who raised a hand in greeting.

“Haiyo Sean,” he said, grinning his golden grin.

“Haiyo Adam,” I said back.

This is the last part of four. Read Part 1 here. Part 2. Part 3.

September 12, 2013

Long Walk to Toronto

It is a warm and breezy Sunday afternoon in Toronto, just the kind of weather that makes us question whether we should be going into a dark movie house to catch one the “hottest” screenings at this year’s international film fest, or hanging a left to a sunny outdoor patio to quench our thirst with a cold beer and good conversation. It was always going to be a toss-up; sadly we choose the movie tickets and are taken for a ride!

The ticket-holders queue is the beginning of what was to be a long and painful afternoon. The “festival of festivals”, as the Toronto International Film Festival (September 5-15) is regarded by many, has become something of a cattle drive for viewers of the common garden variety: no chance of jumping the queue, Jozi-style; these two South Africans are promptly herded, with border-collie precision, to the back of the .5km line, as if to share in a little of that long walk to freedom of Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela before the curtain is raised on the celluloid version. Thus, we join nearly 1,500 others in the Princess of Wales Theatre – no irony lost on the screening venue, its colonial heritage clearly stamped in brocade and gold plate, and its namesake, the departed Diana, being another overstated fan of the aforementioned ‘Madiba’: the symbol of a brand of truth and reconciliation that has forgiven her ancestors their trespasses for 400 years and counting.

Once seated we are given a snappy introduction to the director of “Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom,” a young Brit, Justin Chadwick (resume includes The Other Boleyn Girl), who assures us that prior to shooting the film he spent a year in South Africa, as a new breed of “outsider” – the “listening” and “observing” type (seemingly familiar with the current-speak as per Guide to a Post-Colonial Gaze), who “talked with the family” and “the comrades” (another homogenous brand of characters that doth a struggle make) and followed the sage advice of one, unnamed member of the latter lot, who said, “be sure to tell the story of the man.”

Such words of commitment provide but temporary respite from those of the renowned South African producer, Anant Singh (Yesterday), who offers a slick historical overview of the genesis of the most expensive South African film made to date, focusing on his personal relationship with Mandela, to whom he wrote letters as young, ‘activist’ filmmaker (seemingly to get his paws on the rights to the story of stories). And here he is, finally, on a stage at one of the world’s most moneyed film festivals, offering the big budget work – 30 script drafts and nearly 25 years in the making (with a little help from Hollywood’s Harvey Weinstein). As the afternoon progresses we are apt to conclude that another 25 years might have been called for.

But the stage is set and the curtain goes up on what we suspected all along was going to be a watered-down take on “the man” and the many events and people that shaped him. What we get is a vessel so shot through with holes as to render Mandela a one-dimensional messiah, his comrades mere disciples, and a mass movement of millions of South Africans either hapless victims, flag-waving backdrops who burst into song at mass rallies (in poorly translated English to accommodate those for whom the country’s political vernacular remains unsubtitleable), or marauding perpetrators of violence.

As if picked at random from a Wikipedia version of Long Walk to Freedom – Mandela’s autobiography – are snippets of life, cobbled together, enacted by static characters and filtered through lazy and hazy dialogue as scripted by William Nicholson (Gladiator, Les Miserables); left to wander in life, love and struggle across the panoramic beauty of rural Eastern Cape (cue Lion King soundtrack, panning shots of “the world in one country”, and Madiba, as a young Xhosa initiate, dripping African manhood, aka virile snorting steed, as he emerges from the fresh river waters down in Qunu); through the dusty streets of Orlando or Alexandra in his perfectly pressed suits; or to take a moment to fire a few rounds from a Makarov pistol in a generic “military training camp in North Africa”, before returning in the next scene, as a fully-fledged cadre of UmKhonto we Sizwe, to blow an apartheid landmark to smithereens … stopping neither for breath or a breath of context.

The assumption of the filmmakers seems to be that we have all read the book (and absorbed all the detail), or know the history of South Africa (and have forgotten it), or have heard enough about Mandela to fill in the blanks or to make it up as the film rolls along. Interspersed at odd moments throughout are archival clips – perhaps an attempt to meld drama and documentary at key moments in the script, but one that only serves to give Bono’s voice another cameo, Bob Marley’s War a South African backdrop, and the film editor a lousy reputation for integrating still footage. For such a big budget bang, the least the makers could have ensured was context, continuity and clarity for the buck. But they were having none of that, and so neither are we!

More offensive is the neutralizing or utter absence of key figures in the life of Mandela, those who shaped his very early politics and helped to develop and sustain his leadership of the African National Congress – a liberation movement of people of many persuasions – the very people who featured throughout his book, yet who the filmmakers choose to ignore or reduce to casual extras. We hear the name Walter Sisulu once or twice as Mandela engages with a group of clearly unidentified men in the first hour of the film, and because we know the history can safely pick him out in the crowd. Ahmed (Kathy) Kathrada is given a voice (in all of three scenes) and Oliver Tambo has one line in a fleeting scene related to the decision to take up armed struggle. Govan Mbeki, Raymond Mhlaba, Andrew Mlangeni and Elias Motsoaledi play the parts of invisible presence, ghosts of the Rivonia Trial and Robben Island, silenced by a script that has them cast as observers of history, witnesses rather to the savvy and bravery of Madiba. A scene in which the bereft Mandela is mourning his son, alone in a dank cell on Robben Island, becomes a source of confusion rather than empathy. For here, we have Tata Sisulu escorted into Madiba’s cell to offer him solace, a comforting embrace. Yet, until this point, the film establishes Madiba as the only person bold and daring enough to demand anything of the gaolers. How on earth did the others act without him!

Indeed, Mandela “becomes” not through any influence or engagement with others, but as if out of the fresh air of his Eastern Cape beginnings and even these are addressed fleetingly and with no reference to his Royal House of Thembu lineage and his mission school early education. No exploration either of Mandela’s attendance at Fort Hare University and later the University of the Witwatersrand, the former a centre of radical politics at the time, and how these environments influenced “the story of the man”.

Events also get short shrift. The history behind the murders at Sharpeville, for example, are absent in the film: we get a brief scene dated ‘Sharpeville, 1963’, with the homogenous angry masses on one side of the fence, and on the other a group of maniacal armed cops ready to mow them down before we can say, “Where’s the context? How did we get here?” Where is Robert Sobukwe? Where is the Pan Africanist Congress breakaway? Where is the very backstory that propelled the ANC and Mandela into armed struggle in the first place? Sobukwe not sexy enough? Budget not beefy enough for the meat of history? And why not a whisper, not a glimpse, not even a passing reference later in the chronology to Steve Biko, whose presence of mind, body and sociopolitical thought was certainly not lost on Nelson Mandela and had profound influence on the activism and self-actualization of an entire generation of South Africans. The Soweto uprising of 1976 is but a blip on the screen before being cut to shreds in vaguely contextualized scenes about the radicalization of Winnie Mandela and her association with the controversial Mandela Football Club.

Where are the struggling masses in all this? Where is the trade union movement that mobilized and led mass campaigns of resistance and economic boycott, which made the country ungovernable and, along with international pressure, made Mandela’s release imminent? Getting shot, beaten up, running amok or shouting “Amandla! Mayibuye Africa!” (in Dolby surround-sound, for real people’s power), bereft of voice otherwise, if we are to believe what we see on the screen! Yet hardly should we expect reference to Sobukwe, Biko, COSATU and the 76ers when absent from the start are the Communists. The Party is literally nowhere to be found in the episodic frenzy of the life of a cardboard cut-out. If the film hasn’t achieved artistic greatness, it certainly can be lauded for the art of historical erasure.

Tied to this absence is the silencing of the historical production of the idea of non-racialism. Through the SACP and the various congresses (in particular the Indian Congress) the liberation movement began to imagine the future nation as one belonging to “all who live in it – black and white”. Indeed, the idea was one that Madiba had to be convinced of. But if you haven’t read the book, the screen version of Long Walk to Freedom would have you believing that it was Madiba’s good heart that alone articulated a vision of multi/non-racialism. Communists are nowhere to be found because, frankly, neither is the ANC, nor the ANC Youth League that radicalized Congress.

The director admits that cramming Long Walk to Freedom into two hours of screen time was a big ask, but to gloss over a people’s history to make it seemingly one man’s alone is another mark against a Hollywood rendering that perpetuates all that is wrong about the iconizing of Mandela and the continued neutralizing of ordinary mass action and struggles for justice. The struggle for emancipation from apartheid colonialism thus becomes conflated with the biography of one person – the struggle is subordinated to the life of Mandela, whereas he had certainly meant it as the opposite (cf. Mandela, The Struggle is my Life). As a result of this film rendering, Mandela the leader becomes the patriarch, the finger-wagging father who carries the moral staff and the rest of “the people” are children to be taught to behave. Mandela the thoughtful peace-maker is consistently juxtaposed both rhetorically and visually with the violence of black masses – seemingly gifted at reigning in the instinctive (black) drive for revenge.

The Manichean approach to the world of anti-apartheid struggle is nowhere more obviously presented than in the characters of Winnie Madikizela and Nelson Mandela. Where Winnie is fuelled by hatred, Madiba is fuelled by love; where Winnie’s prison experience causes her descent into the madness of vengeance, Mandela’s strengthens his capacity to be a better man. This juxtaposition is an unfair one. Winnie faced the terror of years of solitary confinement and banishment. Madiba had community, albeit in conditions of incarceration with all its humiliations. And that is what is truly missing from this story. How fascinating to understand the relationships between the men of Robben Island that sustained them for a significant chunk of their lives. How interesting to get to grips with how their emotional, spiritual, physical, intellectual longings were met or sublimated. How necessary to learn about the political perspectives negotiated and unfolding over many years and with younger generations being imprisoned with the stalwarts. In other words, how wonderful a film about an African man that honours him with the depth of an interior (human) life that informs and is informed by his context.

The film-makers suggest that they do just this by showing Mandela, warts and all. The expose, however, lacks substance. He is shown early on as a womanizer and in one scene he beats his first wife, Evelyn. There is no depth to these actions – their banality met only with the equally banal portrait of the older and apparently non-womanizing Mandela, who at one point lectures Winnie about the importance of loyalty (both to him and the ANC). It is a scene devoid of any reflexive power. Winnie, after all, acted no differently than the younger Mandela in her defiance and promiscuity. She was no less discrete. But as a woman and the wife of an icon we are asked to demand other than what we afford “the leader”.

[image error]

It is almost a quarter century since Njabulo Ndebele made a call for a ‘rediscovery of the ordinary’ and it seems in the time it took to make this film, the producers have held on tight to the easier expression of spectacle. Missing are the nuances of character, the complexities of relationships, the very strong traditions of debate and thrashing out of ideas and strategies over many years of struggle, incarceration and negotiation. These are inherent to the movement that made Mandela – indeed, the essence of history and biography that will never be captured in shoddy filmmaking.

Were we so naive to believe that Singh and Weinstein would raise the cash for anything but a Hollywood re-versioning (albeit one that reportedly got the blessing of Madiba himself, though in what state he was in to give the thumbs-up is unclear), or that Justin Chadwick could possibly have made “Long Walk to Freedom” anything but a stroll around the block, we might have been hopeful for an entertaining and poignant afternoon at the movies.

Nelson Mandela To Be Renamed

The South African Government announced on Thursday that former President Nelson Mandela will be renamed ‘Nelson Mandela of the ANC’ with immediate effect. A spokesperson for President Jacob Zuma says the move comes in light of recent confusion over who owns Mandela’s legacy, claiming it was more fitting that “(T)he name of the African National Congress is forever connected to Nelson Mandela and that Nelson Mandela is forever connected to the African National Congress.”

“Madiba of the ANC is old, 90-something,” said the spokesman, adding the party’s name to the anti-Apartheid hero’s affectionate nickname as well. “We feel at this age he is ripe for exploitation with people trying to make money using his name and people trying to claim he supports this thing or that and what what. This is why, we believe, he would support this initiative by our government,” he said.

The renaming will cost approximately R200 million ($22 million) and will begin with the official name change ceremony of all roads bearing the name of the global icon.

“One of these days when he is up and about and feeling good, we’ll take him to have a look at these amazing changes we are making for him, preserving his legacy and fighting poverty, injustice and inequality just the way he wanted. I am sure Madiba of the ANC will be proud,” he concluded.

* This piece is reposted from Garda’s mainstreamisms tumblr.

Under Nelson Mandela Boulevard—A Story About Cape Town’s Tanzanian Stowaways—Winter 2012

Adam called one day in June 2012 to say he had seen a ship he liked the look of in the Ben Schoeman Dock, and that he would probably be gone before the end of the day. We met at The Freezer where he smoked the usual procession of joints and unpacked his travel bag at my request.

Of the two 2l coke bottles of cloudy water that emerged first he said, “The glucose makes it like that. You must have glucose to survive.” Two packets of tennis biscuits followed some Jungle Oats yoghurt bars, and that was it for food and drink.

“It lasts me maybe ten days.”

He also had a torch, a short length of tubular metal and five or six empty plastic packets.

“The best place to hide is inside the cargo hold,” he explained.

“The only problem is they lock the hatch and don’t open it again. It’s fucking dark down there so you need a light.”

The length of metal had a more vital function.

“When your food and water run out you need to use a small iron like this to hit the hatch, so that the sailors can hear and let you out. Otherwise you die down there.”

I had been under the impression that the beach boys aimed to remain hidden for the duration of their sea voyages.

“Never,” Adam corrected.

“That ship can be at sea for 30 days. You can’t carry that much food and water.”

Adam explained that any beach boy who successfully hides himself onboard an outgoing ship will aim to remain hidden only until the ship is beyond the reach of the national coast guard before coming out into the open. It is at this point, he said, that the really difficult part of being a stowaway begins.

“The first thing the crew will do is report you to the Captain, and the first thing the captain will ask is ‘where did you shit in my ship?’ That is why I have these,” said Adam, holding an empty plastic bag up in each hand and flashing his wide boy grin, much the way he would, I imagined, when presenting a week’s worth of shit to some unfortunate ship master.

The next morning, at 5:46am, I was woken by a text message from a number I didn’t recognize, though there was no doubting its provenance.

“Yoh i m going last night i jup on ship name bluu sky. pls keep on touch with me family. fhone my daughter mum pls. pls tell her what is hapen. Memory Card. sea power.”

Five minutes later the phone went again.

“Sean can feel the ship is moven braa sound so nice. alone this time and have no food. i have only wotar but still me go make.”

The 2012 winter seemed to draw out with Adam gone, and whenever I was sluicing down Nelson Mandela Boulevard in my Renault when clouds like giant box jellyfish were dragging skirts of rain across Table Bay, I couldn’t help but think of the beach boys below, huddled around their fires cooking rice in blackened pots, and of Adam, presumed dead by some of his lieutenants. In fact the whole seaward view was permanently changed for me. Where before the light playing off the Atlantic had turned the flyovers, cranes and ships into an oil painting, now I saw only cracks and chinks: bent palisade struts, tunnels, portals, hatches–not just flaws in a postcard perfect view but rents in the great system of human control. And I saw the human nobodies crawling through them, or curled up in utter darkness. Some lines from a poem by local poet Stephen Watson kept playing in my head. In Definitions of a City Watson’s imagination walks a deeply ground path on the face of a mountain, Table Mountain, and fancies that the path pre-dates human settlement. It then occurs to the poet that the paths he is walking do not end where the city begins, that

….should you follow these footpaths really not

That much further, they soon become streets,

Granite kerbs, electric lights. These streets soon

Grow to highways, to dockyards, shipping lanes.

You’ll see how it is—how these paths were only

An older version of streets; that the latter, in turn,

Continue the highways, and the quays of the harbour,

And even, eventually, the whale-roads of the sea.

I found myself missing Stephen, who’d been a friend and mentor until his sudden death from cancer the previous April. And I worried about Adam, my guide in inner city matters, a man whose experiences outreached even the poetic imagination.

Then one day in September the sun appeared without warning and lashed the peninsula with the sort of heat-bearing rays that unseal, lift and give voltage to the smell of every urine stain and beetle carcass on the city floor. It was a perfect day for lifting beach boy graffiti from the highway substructure, because the Herzog Boulevard boys, who guarded the entrance to the underpasses, would be too busy washing themselves out of 25 litre paint drums to mind our snooping. Down under Nelson Mandela Boulevard Dave and I skirted a tree which had been turned into an eerie mobile of home-made coat hangers, and we began transcribing slogans as defiant and crude as the men soaping their genitals on the island at eye level with the passing vehicles.

Memory Card Me Like Ship No Like Pussy

Easy to Die tough to Get

Opportunity Never Come Twise

God Yucken Bless Mi

Don’t West Your Time

No pain to spain

Nothing is tough Accept tough is yourself

Sea never dry

Escape from cape

Our next destination was the Lower Church Street bridge over the N1 highway, an area the beach boys call “Vietnam” on account of the number of palm trees growing from the verges there. The grassy banks, bright green from the winter rains, were a-bloom with drying clothes–exploded views, when seen from the elevation of the bridge, of the beach boys’ winter uniform: Peruvian beanie, hoodie, overshirt, second overshirt, undershirt, second undershirt, pair of baggy jeans, fingerless gloves and the notable absence of underpants and socks. In a rare sonic lull between passing vehicles we heard the strains of reggae, and followed these beneath the bridge to find Rashidi Mwanza and his friend Ngaribo Masters wedged like overgrown pigeons up where the abutment wall met the underside of the bridge. They had just smoked a joint and giggled uncontrollably when we spotted them. When we explained we were there for the graffiti they almost fell off their perch they laughed so hard, though they both agreed to look at our transcriptions once we were done. 20 minutes later they were running their eyes down a list of markings that had made no sense to us. They were no longer laughing.

TMK

CTR/018729/03

Junior No More

Some Win some Lost Some die

“TMK is for Temeke in Dar es Salaam, where we are both from, and this number is a permit number. We write out permit numbers on the walls so that we don’t lose them,” Rashidi began.

“Who is Junior?” I asked, and Ngaribo, who taught himself to make Rastafarian amulets out of beads and fishing gut rather than push drugs or trolleys, rubbed his hands together worriedly.

“Junior No More,” he said.

“He means Junior is dead,” Rashidi clarified.

“He was crushed last year by a truck, crossing by the highway to The Freezer. He was Ngaribo’s main man,” he added. Ngaribo looked away and for the first time I noticed the tattoo: three tears spilt from the corner of his right eye.

“Some lost, some win, some die. It’s no fucking joke,” said Rashidi.

It was Moses who eventually explained the ubiquity of the overall. At 38 Moses was the oldest beach boy I knew and also the smallest–a bantam weight proficient in English and endlessly troubled by a cut in his right hand the size and shape of a fish’s mouth. He claimed to know everything there was to know about beach boy life, and I came to rely on him to fill in the gaps in my knowledge, something we did away from the other beach boys, sitting next to the kugel fountain outside the Woolworths HQ on Longmarket street.

Every beach boy owns an overall, he explained, for the same reason that most owned work boots, a safety helmet and safety goggles.

“So that the security guards in the dock will think you are dockworkers?” I said, pre-empting the rest of the answer.

“That is true, man, that is true. But it is not how we come to own these things. That is another story.”

To get to this other story Moses described his first journey to South Africa from his home in Dar es Salaam’s Ukonga township, “which we call Mombasa”. It was sometime in 2003. He had heard it was possible to leave Africa hidden in ships but not from the port of Dar es Salaam, “because Dar es Salaam ships travel only to other African ports, or to mainland China, and nobody wants a mainland china ship,” he said. Moses hitchhiked south to Malawi and jumped the border into Mozambique at the southern end, near Deza. He thumbed his way through the Tete Corridor to Mchope, and pushed all the way down to Maputo, where he found “so many Tanzanian brothers”, especially at a market his brothers called “Australia”. From Maputo he travelled to Ponto d’ouro, where he jumped the border into South Africa and came to the outskirts of Manguzi, where he helped a woman carry her bags in exchange for a fare into town. In town he found “other brothers” who took him to a “hook house”, or shack, down by the Gesiza River, where he found “Bongo people, my people”. Bongo, he explained, was the Swahili word for head, and it was what all Tanzanians called people from Dar es Salaam, “because we use our heads to make money, right.” His brother Bongo men in the hook house told Moses to go to the Boxer supermarket in Manguzi, “where people come past, looking for work crews”. He found employment with a woman farmer who had him “dig her field with a djembe for R10 a day plus food.” After a week he had R50, which he used to pay for space in a Durban-bound truck.

“We reached Durban at about 2am and as soon as that truck opened everyone was looking everywhere to see where they could go, and we were running, running, running, you know. But me, I’m a sailor man, I know only one place, the docks, straight to the docks, man, and there, of course, were the brothers again.”

The first ship Moses caught was called the Cape Belle, a handsome red-hulled reefer which disappointed him terribly by proceeding directly to Cape Town and not Athens, his destination of choice.

“I was found by the chief officer, who took me to the captain, and he said ‘do you know this port of Cape Town?’ I lied and said ‘yes’ and he gave me a port workers’ uniform, which we call chamzebenzo. He gave me food, and said ‘walk’. At the boom the security asked me for a permit and I gave them the permit the captain gave to me,” said Moses, thumping his shirt against his heart.

“That is why too many beach boys have the overall,” he concluded.

Taking a Critical Look at Dominant White Beauty Ideals

Miley Cyrus and all the twerking (for those in need of a catch up read this), black-faced and red-faced models in Dutch Vogue, the historical representation of women of color and the whiteness of the wedding industry: these were just a few things on the agenda of the first Redmond Summer Event this year. Redmond is an Amsterdam-based intersectional feminist media collective that I am part of. We thought it was time to have a real conversation about beauty ideals, whiteness, race and cultural appropriation. In the Netherlands, white feminists have expressed concern when it comes to thin models, the use of Photoshop to alter body sizes, and the pervasive influence of the fashion industry on young girls but they have also failed to address the whiteness of the dominant beauty ideal.

For the debate, Redmond invited five women of color (Patricia Kaersenhout and — in the picture above, from left to right — Kim Dankoor, Simone Zeefuik, Tessa Boerman, Bel Parnell-Berry) to listen to their perspectives on the dominant white beauty ideal. Why does the whiteness of this beauty ideal need to be addressed? Redmond asked how these women of color deal with dominant beauty ideals in their daily lives and in their work as artists, academics, journalists and activists. The panel shared their visions and ideas with the audience. We will not bore you with too many details but we thought it would be nice to introduce some of the ideas these artists and activists are negotiating in the Netherlands.

Patricia Kaersenhout, a Dutch artist with Surinamese roots, looks at the representation of women of color in relation to racism, sexism and the legacies of slavery and colonialism in her work. She spoke with us about the historical neglect of black women but also current representations of women of color. Kaersenhout stressed the need for counter images, images of women of color that are not stereotypical. Inspired by the book Ain’t I A Woman by bell hooks, she created the series, ‘what you don’t see is what you won’t get’. She also showed some of the images from her series, ‘your history makes me so horny’ made on fabric. They speak to the sexualization of the black body and raise questions about desire, objectification and the neglect of the female black body:

After putting the representation of women of color in a somewhat historical perspective, Tessa Boerman, a documentary filmmaker maker by profession, screened two short clips of her work. She has made two powerful documentaries that highlight different aspects of beauty, ideals and belonging. ‘A Knock Out’ looks at the life of Michele Aboro, a black lesbian boxer who was very successful in the ring but was told that she wasn’t sexy enough outside of it; the promoters wanted to see a sexy vamp and terminated her contract early. Her film also implicates that the white beauty ideal does not stand alone but relates to broader issues such as everyday and institutionalized racism as well. Her second documentary, ‘Zwart Belicht’, explores the historic representation of black women in paintings of Rubens:

Activist and academic Bell Parnell Berry addressed how beauty ideals relate to gender and race within the wedding industry. There are hardly any wedding magazines featuring people of color, people that are not thin, same sex couples or non cis-gendered people. Bell Parnell Berry critically discussed contemporary TV shows such as ‘My Fat Big Gypsy Wedding’ and ‘Don’t tell the bride’. In response to this lack of representation she decided to start her own blog, Invisible Brides.

Simone Zeefuik, community organizer and co-founder of Re-Definition, a platform for poets and writers, spoke about the role of language in fashion magazines. Language, as we know, is never neutral and plays an important role when it comes to sending messages about what is beautiful and what is not. For instance, several hair ads speak about containing ‘messy natural afro hair’ to make sure it becomes nice and straight.

The final panelist, Kim Dankoor works as a journalist and media educator. She has researched the impact that Hip-Hop videos might have on young women of color in Atlanta, U.S.A., and in the Netherlands. It appeared that many women desired to be lighter-skinned and even considered skin bleaching, a subject that she plans to research and document further.

The Redmond Summer was a first attempt to start a conversation about some the issues mentioned above, but of course our conversations weren’t exhaustive – there is still much to be addressed. Deconstructing and critiquing what seems so normalized is key to understand how white beauty ideals and systems of whiteness work.

September 11, 2013

A Conversation with Photographer Juan Orrantia about Guinea-Bissau and his Search for Amilcar Cabral

Technically speaking, photography is the process of capturing light. Compose the frame. Release the shutter. And let the light pour into the camera’s memory, whether a roll of film or a digital sensor. When the captured light is transformed into an image however, it has much to say. It speaks about the environment it once illuminated, the vision of the image maker and if you look closely enough, even history.

With his lens, photographer Juan Orrantia skillfully invites remnants of a place’s history to reveal themselves through light. His work often deals with places that have a history of violence and revolution. Through his projects he shows how the horrors of conflict are transformed into scars not fully healed. Whether manifested in deteriorating physical structures or in the destructive social phenomena left by the war economy, the memory of the struggle endures in the peoples and places that have experienced it. Finding evidence of social memories in the scenes he documents, Juan demonstrates just how dynamic and interdisciplinary photography can be.

Originally from Colombia, Juan has traveled widely, putting into practice creative mediums for producing his critical documentary art. For the last three years, Juan has been based at the University of Witwatersrand in Johannesburg where he just finished a post-doctoral research fellowship at the Wits School of Arts.

After previous projects documenting the aftermath of violence in Colombia and Mozambique, Juan travelled to Guinea-Bissau for his most recent documentary project. Called Holding Amilcar, after Amilcar Cabral, the revolutionary luminary who lost his life in the struggle for Guinea-Bissau’s independence, Juan sought and documented aspects of Cabral’s legacy as they appear in lives of Guinea-Bissau’s citizens and public monuments.

We spoke to Juan about his search for Amilcar, post-conflict social landscapes and the power of people in shaping ways of seeing.

“Why should so small a country, and one so poor, interest the world?”

Your latest body of images, Holding Amilcar, were taken in Guinea-Bissau. What drew you to Bissau and to the ghost of the revolutionary thinker Amilcar Cabral?

Juan Orrantia: I have been living in South Africa for almost five years now. And I felt I wanted to pursue a project that brought my growing interest and what I have learned in the continent with an aspect closer to home. The “obvious” choice was Guinea-Bissau, since as a Colombian it is a clear place where my own history intersects with the continent in contemporary issues. But there was a lot more than the drug business there. There is of course the figure of Amilcar Cabral, a very important thinker, read widely in different parts of the world, and Chris Marker, someone whose work I find fascinating and very important for a type of critical aesthetic form of documentary. With this in mind, together with a Colombian journalist friend Salym Fayad, we decided to go, and the country opened itself to us in all kinds of ways. We had all these interesting topics in front of us, but it was also hard to photograph, since when we arrived in early December 2012 the most recent coup was still in the air. We thus hit the streets initially, and I was fascinated by the postcolonial and (post)socialist landscape.

Cabral was assassinated in ’73 in the war against the Portuguese for Guinea-Bissau’s independence. Do Cabral’s revolutionary philosophies continue to permeate the collective social consciousness of the country? How does Cabral’s legacy reveal itself in your images?

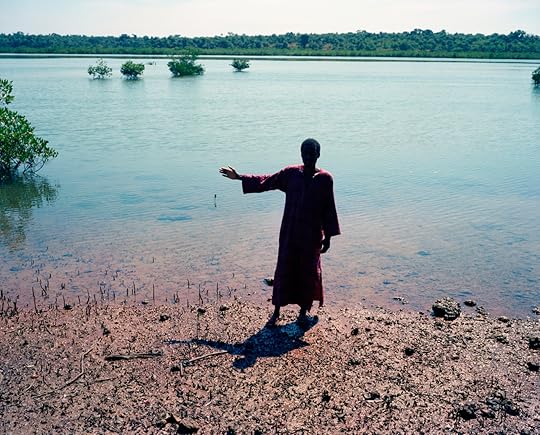

Amilcar Cabral is a very interesting figure in contemporary Bissau. Not only is he part of the founding myth of the country itself but more than being an iconic figure of the past he also seems to fade away and then reappear. In my photos I try to allude to the sense of freedom that he inspired and wanted, yet also to the disappearance of those dreams amidst current conditions. I shot many of the images in his hometown of Bafatá, because I wanted to see how the place is, or is not, filled with his traces. And I am also interested in the role that Cabral played in Chris Marker’s film Sans Soleil, to which I also want to allude to in the series. There he represented a pole, an example of revolutionary potential and power and its fading into the future. I don’t want to just see him as a source of the past but rather as an element within the present.

Monument, Pidjiguiti. “Rumor has it that every third world leader coined the same phrase the morning after independence: now the real problems start. Cabral never had a chance to say it. He was assassinated first. But the problems started, and went on, and are still going on.”

Many of your images do not contain people, but rather they convey the evidence of human life. What are these landscapes communicating to you?

That’s a nice way of putting it, thanks! When I started in this line of work, I started out photographing people, in their homes, very into the action of moments. But I also always had an interest in place and how it accumulates events and things that happened there (you have to understand, my first big project was in a small town in Colombia where there had been a massacre 5 years before). Since then, I have been slowly moving into another style, where both people and place are expressing issues without one having to rely on the obvious image — lets call it the journalistic one — where all of the information is contained within the frame. I prefer the more ambiguous, expressive, suggestive image, that allows one to interact with the situation and its representation. I have this thing of looking at places and thinking of what has happened there, what the places themselves contain. But I wouldn’t say I am a landscape photographer, I am in search for answers both within people and in their surroundings. I think that also my career has taken me to reject some of my training in anthropology and its almost obsessive approach to having to speak to people to get to some sort of understanding. There are many other sensory ways of interacting that allow one to engage with topics of intellectual concern, and colors, forms, sounds, all participate in that. Having said that, I also wanted to photograph places related to where Chris Marker and Flora Gomes shot their movies, because the project does have a very important “filmic” element (or intellectual relation) to it.

Prison, Bafata (Amilcar Cabral’s birth place)

For the images that do contain people, how would you describe the moments that you are trying to capture?

In this series I am mostly using the images of people from one location (although not exclusively). I decided to juxtapose the images of those who are in a drug/mental rehab center in Guinea-Bissau with the other style of photos (places, etc). These people represent for me an idea of locked up dreams, not dead or past ones, but the idea of moments when dreams are suspended, or put on hold. The idea of postcolonial dreams. These people also represent the “drug” situation in a way. We didn’t want to photograph the drug dealer, the crack head, none of that. Some of it has been done in the country, in very strict photojournalistic fashion. I am not interested in that, I am interested in the subtlety of the situations, of the slow passing of time and the situations this creates, and then of course, how this is suggested through an attitude or an expression. I also had great conversations with them, like this guy whose name is Amilcar and then joked about his last name being Cabral. So I did find my Amilcar here!

How did the people you encountered in Guinea-Bissau react to your image-making?

In general people were great and open. I did feel less comfortable in the capital, Bissau, because of the political situation, and everyone warning us about the camera and the military. But outside of the “official” environment, in closed or intimate situations, things were smooth.

As someone with Colombian heritage, what political parallels did you observe between Colombia and Guinea-Bissau?

Well, not necessarily parallels as such. The history and the way narcotraffic relates to social life is very different in both places. But what was very interesting — having lived much of my life in Colombia, especially during the hard drug years — was to come with an idea of what we were supposed to encounter do to the media representations of Guinea-Bissau (the first real “narco state”, etc). Before we arrived we interviewed high officials from organizations dealing with drug trafficking in the area, and the picture they painted was one where they were literally comparing the country to when Colombia was in its worst time. What we found was a different picture; yes, there is tension, yes, there are signs that the illegal business is there, all that is true. But it is also not so evident or outrageous as it somehow seems to be. But we actually were not there to “follow” or expose the business in strict journalistic terms; we wanted to see what the country looked like, what the people said, how they felt about that and other things as well. And yes, it is a poor and shattered country, but it does not feel like Colombia in the 1990s, not at all.

“That’s how history advances, plugging its memory as one plugs one’s ears.”

You have a PhD from Yale in anthropology and have been called a visual anthropologist, yet you alluded to the relationships you’ve forged with people in your photographic career having caused you to question your anthropology training. How have these personal interactions altered your perspective?

Anthropology gave me a very good perspective of thinking critically. For me it is an informed sensibility that guides my engagement with a question, a topic or even a place. That is what I bring from it to my form of working. But I am also not doing anthropology as such in its analytical form. I was never comfortable doing that. I am more comfortable with the idea of a critical documentary, of creating aesthetic commentaries on topics or places with a purpose. That is where photography and its different ways of working come in, and the end result, I guess, is another form still, produced by the interaction of both (among others).

You often shoot with a medium format film camera. Does medium format film, with its limited number of frames and visible grains, allow you to express your vision in a way that digital photography cannot?

I use a 6×7 format, so it’s a very visible, if very quiet, camera. So people know I am there and taking photos, which I like. Until now, all my projects have been film based. I love the quality, the tones, the grain, and the pace. I shoot very little compared to digital photography, and I also can’t do any on-site editing. That helps me think about the project a lot. I don’t feel pressured to have to take this or that, I rather shoot as I encounter, I think, rethink, shoot some more, and then sometimes a few months later, after the film has been developed and I start scanning the lot, rearrange. By then my ideas and experiences have been a bit more digested, which does help me in editing. It comes down to the relationship between the intellectual idea and the aesthetic choice, and how those two will work out.

“And that is the way the breakers recede. And so predictably that one has to believe in a kind of amnesia of the future that history distributes through mercy or calculation to whom it recruits.”

Your research fellowship has been at the Wits School of Art in Johannesburg. There is an incredible wealth of artists working with visual media in South Africa. Who are your favorites?

The fellowship at Wits was great, and being involved in the photography milieu here was really important. It’s great to be in a place with such a rich photo tradition, and yet in the south, not in the traditional euro-american centers. Personally, I feel very fortunate since I got to work for a couple of years with Jo Ratcliffe, whom I think is an amazing photographer, an intellectually grounded one with a very sharp eye. Santu Mofokeng is a master of the poetic documentary. Penny Siopis makes these great videos with found footage which are very critically lyrical. I think there is also much to learn from works by those better known in international circles like Guy Tillim and , and — even if not necessarily South african — Vivian Sassen’s engagement with the banal does shake “African” representations a lot….and then, the newer names, some of whom I have worked with through fellowships like Thabiso Sekgala, Vincent Bezuidenhout, Alexia Webster, Musa Nxumalo, and many other people engaging new ways of seeing what history is producing in front of them and through them.

As a resident of Johannesburg for the last few years where historically and currently, public space is greatly contested in various ways from access to control to moniker, what has your relationship been with this dynamic city?

Joburg is not easy, but it also has an edge to it. It is as you say, very dynamic and full of interesting people. I really like that, and this has given me a new vantage point from where to read the world today. But I also have a schizophrenic relationship with it. Maybe its own dynamism shifts me around.

In your life you’ve been quite a wayfarer, how has this frequent movement shaped your own sense of self, place and memory?

It’s tiring! But more than that, it gives one multiple perspectives, it definitely shakes things up, and allows me to connect and traverse different spheres, not just places, but networks, experiences, situations and aesthetics that are being developed through the south.

Now that you’ve completed your fellowship, what upcoming projects do you have brewing?

Well, this Guinea-Bissau project is really in its beginnings, and so I am looking forward to going back and expanding this series as well as other aspects of the project. I am also working on a book project on memory and narcotraffic’s legacy in Colombia, based on work I have been photographing mostly in a small ex-coca and cocaine producing village that I knew well back in my undergraduate years. And I am off to India for five months as we speak, so let’s see what comes out of that!

* Juan Orrantia’s portfolio can be viewed here. The captions for the images are quotes from Chris Marker’s film Sans Soleil.

Under Nelson Mandela Boulevard—A Story About Cape Town’s Tanzanian Stowaways—Spring 2011

It was a few months before I bumped into Daniel-Peter again. His once tiny English vocabulary, which had nevertheless contained the words “anchorage”, “fibreglass”, “first mate” and “consulate”–gleaned from the Ukranian crew of a ship he boarded in Durban in 2010–had expanded to the point at which unmediated conversation had become possible. It was an unplanned meeting so the story he told about his life went down on the inside of a KFC burger box, the contents of which we’d just eaten sitting up at The Freezer.

My mother I like too much. Ma, she like me too much. Father made wrong, father no good. I have sister. Sister is die. Ma she sick, one month she never talk. She need blood so I make out blood. One day she look me, sit up and take me (grabs his shirt lapels in his fists), pull me down. I do like this (forcefully opens the fingers of one fist with the fingers of his other hand) and she die like that. I left Tanzania.

The story of his subsequent journey to South Africa had an adventure book quality I found dubious: lions at night with eyes like torches gorging on hapless fellow travellers in the wilds of northern Mozambique, and so forth. I steered the conversation back to the ships. Where did he hide on the Ukranian vessel? Daniel-Peter waggled a mini-loaf in the direction of a cargo ship in the Duncan Dock, clearly struggling for the right words.

Then he had an idea. Reaching into a small blue rucksack he pulled out a large blue faux-leather 2010 diary, the corners of which had swollen and burst. This he opened first at the pastel-coloured continental maps that large diaries have at front and back, where he pointed out Dakar, Jakarta, Singapore, Dubai–some of the cities he had travelled to. On almost every other page he had drawn cargo and container ships in pencil and pen. He began jabbing at them with his callused fighters’ fingers, pointing out the engine room, the lifeboats, the tonnage hatches, even the bulbed area above the rudder—all established beach boy hiding places. Lastly he pointed out the portal to the anchor chain locker, and waved his hand to indicate danger.

“Fire.”

“Fire?”

“Anchor out, fire in,” he clarified, and to demonstrate what a gigantic anchor chain rapidly paying out through a small portal would do to a human body caught up in the action he scooped up a handful of dirt from between his feet, and threw it out over the N1.

Not all the beach boys welcomed our interest in their business and some, like the crew that had made their beds amongst the restios on the Herzog Boulevard traffic island, were nakedly hostile. The first time we arrived at their island with our introductory speech the six or seven men sitting there on upturned paint buckets just stared back wordlessly. One of the men, just a boy really in a red overall with reflective strips at the knees, was lying back in the warm sand between the plants. With his one hand he was shielding his face with a news poster and with the other he was masturbating inside his overall. He kept his solemn eyes on us while tugging away at himself until eventually his enjoyment of his own insult proved too much, and he cracked up laughing. Some of the others pitched in with mirthless laughter and then they picked up their personal items—jackets, bottles, sun-bleached rucksacks—and wandered off into town.

The friendlier beach boys repeatedly insisted there were no leaders in the community. Without doubt, though, the dominant member of the Herzog Boulevard crew was Juma, a broad-nosed man in his late 20s, whose matted dreadlocks glinted with colourful beads. Juma is as common a Tanzanian name as Dave is an English one but the relationship that developed between Juma the seaman and Dave the photographer was fairly unique. They first met in the winter of 2011. Driving rain had forced the island boys to join the general population under Nelson Mandela Boulevard. Temporarily de-territorialised, Juma was chattier that day than he has been since. Without being asked to, he expounded on the dangers inherent in the beach boy life, foremost amongst which, he said, were the Chinese.

“Not Hong Kong Chinese, Mainland Chinese,” he clarified.

“If the ship crew is all Mainland China you have a problem because they might throw you overboard. On other ships there is a mixed crew—India, Greek-y, Korea—so this is not possible.”

Juma said that a beach boy who had spent time in Cape Town had been thrown overboard by a Chinese captain off the coast of Tanzania.

“He has become our hero because he survived and reported that ship. The captain was given his whole life in jail and the crew were given 20 years. You can still see the story on the internet,” he said, at which point he hauled off his jacket and his hoodie, and several more subsidiary layers, and presented us with the dolphin he’d had tattooed on a shoulder blade. It was, he said, his protection against drowning.

No doubt encouraged by his forthrightness Dave asked Juma if he would mind posing for a photograph. Juma nodded, pulled his layers back on, and smiled for the camera. After taking his portrait Dave asked if he could photograph the protective charm. Without hesitation Juma asked for money, and just as reflexively Dave refused. Dave and Juma have bumped into each other a dozen times since. On each occasion Dave has asked Juma if he wouldn’t mind taking his shirt off and just as reliably Juma has grinned and asked for money. For R50, possibly R20, Juma would happily expose his shoulder to the lens, but Cecil Rhodes will return to govern the cape before either man—the beach boy from Dar es Salaam or the photographer from Pietermaritzburg—will back off a principle.

This is the second part of four. Read part 1 here.

September 10, 2013

For young musicians in Mozambique, “a career in music is a pipe dream”

Young musicians in Mozambique don’t have much opportunity to record and distribute their music. “Wired for Sound,” a mobile recording studio that currently tours northern Mozambique seeks to change that. The team of the founding member of the South African band Freshlyground Simon Attwell, radio producer Kim Winter, and Freshlyground guitarist Julio Sigauque, who was born in Maputo, record young musical talent and explore how Mozambican youths express themselves through their music.

All the musicians receive their own recordings on disc, and the initial recordings are broadcasted on community radio stations. When back in South Africa, the team of Wired for Sound plans to work on selected tracks with more established musicians and producers to make a 5 track EP and then an album after the next phases of the project, which will include trips to other countries in different parts of Africa. Proceeds from these albums will be fed back to community radio stations, most likely in the form of permanent production facilities.

We conducted an email interview with the team of Wired for Sound while they were driving through Malawi to Mozambique’s Niassa province. So far, the trip has been a success: ”The north is not an easy place for visitors or for locals but we have been received generously and with open hearts. The young people are proud to be Mozambican, fierce about building a peaceful nation and willing to share a culture rich in history and music.”

How did you get the idea for “Wired for Sound”?

Wired for Sound (WFS) is a project that combines our love of music, radio and travel—and a desire to work with a young community of musicians across Southern Africa. We are currently working on the pilot project in Northern Mozambique.

At core we are a mobile recording studio, designed around a 4×4 vehicle with battery system and solar panel, which means we are equipped to record pretty much anywhere. So far we have set up next to ruins on Mount Serra Choa, in a mango forest in an old missionary station on the outskirts of Catandica, and in an abandoned military airfield in Furancungo.

Simon had been playing with the idea of creating a mobile recording studio for a while, brainstorming with the Open Society Initiative for Southern Africa (OSISA) on how to access young musicians in remote areas, not only creating opportunities for young talent to record and collaborate with more established musicians, but also to try explore the realities of youth culture through expression in music—the stories behind the words through interviews, radio debates and radio documentaries.

How did you decide to work with local community radio stations?

It made sense to partner with community radio stations for the Mozambican pilot, and Wired for Sound is working with the Community Radios National Forum of Mozambique (FORCOM), itself an OSISA-funded organization, in order to enrich the WFS vision and outcomes. As radio enthusiasts, we feel strongly about opening up ways in which quality content can be generated by Africans, finding a place on African stations as well as internationally. In each of the four provinces we visit on this trip (Manica, Tete, Cabo Delgado and Nampula) we are collaborating with at least one local community radio station. They are an entry point into the community, a link to local musicians as well as a vital insight into the workings of the area. Once we have met, worked with and recorded a select group of local musicians, the radio station hosts a live discussion, plays snippets of each recording and interviews all involved about the music, their lives and dreams.

We are putting together two radio documentaries on the road—one for local dissemination on Mozambican radio and one for international syndication on our experience of the project as a whole.

Why did you decide to travel through the northern provinces of Mozambique and not the Center or South?

We traveled to Mozambique a few times during the preparatory year, attending community radio conferences, meeting with local journalists, musicians and anthropologists—and from these conversations it emerged that North Mozambique is far less explored both musically and geographically. We wanted to be able to access remote places to see for ourselves how people (especially young people) express themselves and what kind of access they have to media and platforms for discussion and debate. An economic boom and big scale development in Mozambique have recently made headlines, and for both OSISA and WFS the intersection between this development and the effect it has on young people’s lives is a fascinating issue to explore.

How do you think music can bring about a discussion about rights and other issues of concern to the youth?

One of the difficulties facing us on the road is language. Julio acts as a translator but is not always able to understand the local languages—sometimes we have a three way conversations from English to Portuguese to a local language and back again, which can get interesting! The magic happens when we sit down with musicians and jam—we have ended up working across genders and backgrounds with young musicians who are musically extremely talented and with some who may not be naturals but just love to sing or rap or who have local knowledge about more traditional music.

Each musician so far has generated original material, and during the jamming sessions and conversations afterwards, we get to unpack the songs or an instruments’ history and in doing so, learn about people’s lives, their personal stories and the issues close to their hearts. Lyrics have been about everything from love, family history, calls for peace or messages about corrupt authoritative structures—for us music has served as an inroad into people’s lives, giving us a chance to share stories in ways we may not have been able to otherwise.

How do you find the musicians whose music you’re recording on your trip?

We try and spend at least a week in an area, interacting with local musicians who have established relationships with the community radio station, and following up leads on musicians from hearsay. Recording and production facilities in these areas are seriously limited or entirely absent. Good quality microphones, recording gear and editing suites are pretty much non-existent even for the community radio stations despite the enormous talent. So, given an opportunity to record a demo and have it played on air has been a big win for everyone involved, and subsequently finding musicians has not really been an issue!

However, we have been faced with some tough questions about how people’s lives can be changed or made better through this project. Fair questions, leading to lengthy discussions about how we can make this kind of project continuously work for the communities involved. It has been hard not to have all the answers now but we are creating an amazing network of young musicians and journalists as we go, who will be instrumental in designing the sustainability component – whether it be a permanent production set up at each station or equipment sponsorship etc. Marshall Music Cape Town and AKG came on board for this pilot project and we hope to illicit their support in making this a reality.

What issues have come up in the radio conversations and the music you recorded? What are young people concerned about?

A few stories so far… Nelito, 21 and Armando, 20, are two young guys we worked with in Catandica (Manica Province). They combined rap and more traditional song—which worked pretty well! The two are from the port town of Beira and currently live alone in Catandica where they attend Grade 12 (it is one of the few paces in the province that offer Grade 11 & 12.) Nelito wants to pursue music in Maputo, following in his cousin’s footsteps while Armando has plans to study accounting. They co-wrote the lyrics to a rap that tells a true story about a young man who finds out the girl he is dating has a child with another man. Along with issues about love and trust, Nelito and Armando spoke about the challenges living alone in Catandica with no access to employment and with very little to do as a young person. There are no performance venues, dance clubs or cinemas in Catandica—a place with a population of about 126,000 people.

Access to quality education has come up again and again. A girls group, Redes, performed an old peace song for us in Catandica and we were able to sit and chat after the recording. Many of the local girls don’t go to school and the students take it upon themselves to teach others. They spoke to us about teachers not taking their work seriously, often leaving school early to drink. Another major issue the girls brought up, echoed throughout Africa, is sugar daddies. In Catandica, older men buy young girls cellphones expecting sex in return, adding to the already high number of teenage pregnancies and school dropouts. Cellphones are a status symbol and often the only access to the Internet for students, journalists and locals alike. Facebook is used more than email.

Mapinhane, 32, is a teacher at a local school but for 500MC he records and makes home videos of local musicians in his spare time. He is passionate about music using only the microphone from his 90’s model video camera to record. There is little access to equipment and even basic instruments—as his guitarist, Massimba, 37, knows all too well. Massimba plays an old, out of tune guitar beautifully and did some fine recordings using Julio’s guitar. He also sang a song the words of which revealed how churches in the area take advantage of the people and their money.

Banda, 30, and Marcelino, 24, live in Furancungo, about 160 km from the town of Tete a short distance from the Malawian border. Banda has a mixed style of zuk / Marabente and Siznho is a traditionalist with some gospel thrown into the mix. Rusting military tanks litter the dirt road to Furancungo and the abandoned military airfield we recorded in serves as a constant reminder of the past. The two singers were too young to remember the war but are aware of its presence every day. They are hugely talented singers and have been recorded by amateur producers who travel down from Malawi. However, they have not seen much remuneration for these recordings and are forced to work in the agricultural sector. A career in music is a pipe dream.

Photos by Simon Attwell, taken in Mbonge Village, Pemba, and Catandica, Manica. More photos and sound clips here.

100 Years of Land Dispossession in South Africa

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the Natives Land Act, which ratified and legalized the exclusion of South Africa’s black majority from land ownership in favor of the white minority. The result was “just 7% of agricultural land set aside for blacks, though they comprised nearly 70% of the population.” Following changes to the act in 1936, whites would own up to 87% of land by the end of Apartheid. Since the end of Apartheid, the government has been slow in effecting land reform, hampered by a range of factors, including threats from business, organized agriculture (basically white farmers), its controversial “willing buyer, willing seller” approach and a lack of political will. Ben Cousins is a professor at the University of Western Cape and founder of the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies. Since 1989, Cousins has researched land reform, communal areas and small holder agriculture. He has studied Swaziland’s land reform from 1976-1983, Zimbabwe from 1983-1991 and South Africa from the early 1990s. In June, Cousins won the Elinor Ostrom Award for his commitment to the analysis, creation and defence of common pool resources.

How would you describe the legacy of the 1913 Land Act?

Well, Henry Bernstein, a professor at the School of Oriental and African studies in the University of London, describes the South African agrarian question as extreme and exceptional.

The division of ownership on the basis of race was extreme. There was a large amount of black people squeezed into small areas of land, and small numbers of white people with large areas of land. It’s a very extreme form of land redistribution in general, but on productive land in particular.

The fact that this racial distribution came with class divisions, between capital on the one hand, and cheap labour on the other, means that confusion has risen about what extent this is racial dispossession and oppression, or class dispossession and oppression. They were both combined, in complicated ways, and all underpinned by gender inequality. In the earlier twentieth century, people were put into reserves in large numbers, and prevented from accumulating as farmers. Any kind of smallholder or peasant farm was eliminated by state policy, because these people were intended to be labour for the mines, factories, and commercial farms. So, the land question is combined with the labour question.

And along also came the native question, the governance dimension. In areas designated for black people, a particular kind of governance regime was installed. This was essentially a direct rule, a rule through the chiefs, a system that the British implemented in many other parts: complying chiefs helped the colonial government rule. The chiefs became accountable to government. So the whole question of chiefs, land tenure and who has authority to govern that land is another legacy of the Land Act.

What percentage of the total land of South Africa do these areas represent?

The 1913 Act said 7 per cent. And then the 1936 Act added another 6 per cent. So that’s where the famous figure of 13 per cent [of land for black people] comes from.

But, as other historians have pointed out, a lot of the dispossession had already taken place by 1913. That Act was actually ratifying and setting in law a dispossession that started much earlier, centuries earlier.

But why have the Act then?

Well, it was now uniting the different provinces, a national piece of legislation that united a country saying: “these are areas for black, areas for whites …”. Dispossession had taken place under separate policies and legislative frameworks in different parts of the country. There was not overall coherence to it. The Land Act brought it all together.

What were the mistakes or achievements of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) on the land question?

Basically it didn’t deal with the land question, because we had a Restitution Act, we had a land reform policy. The land restitution process is the only program of reconciliation other then the TRC. Land was dealt as a special category. We had a TRC for dealing with reconciliation in general. And then we had a restitution program, which was supposed to deal with the land question.

But what we have seen with the re-opening of Khoisan claims (those who lost land before 1913) is that the issue was never put into bed. It didn’t resolve. Just as with the TRC, there are lots of unresolved questions. In fact, the TRC did not resolve a series of issues to do with the day-to-day oppressions of Apartheid. It dealt with gross violations of abuse. It didn’t dealt with businesses; it didn’t deal with the way capital under Apartheid directly benefited. So that’s the complicated part with restitution. It didn’t actually open the whole question to the various kinds of reconciliation processes to deal with the past. Now the past has come back to haunt us.

With the government’s new policy of opening up claims for pre-1913 dispossession, we see Khoisan groupings saying “we own”, for example, “the whole of Cape Town, so we are taking down the houses in District 6″. This is the Pandora’s box the government is now opening with restitution, a purely populist measure, in my view, and that could actually be bad for land reform. It will just add complexity, extra costs and will not result in transferring much land to the descendants of the Khoisan. The Government will try to arrange them with access to heritage sights, a kind of symbolic restoration rather than actual restoration. And it will be a massive distraction. And the real tasks, the real complexities of land reform will not be dealt with. It’s a symptom of Jacob Zuma’s regime style, which is to be populist on the one hand, and deeply conservative on the other.

What has the ANC done well since 1994? Are there any successful land programs?

The land reform program has been highly problematic, but before we get into that, it’s important to say that those people who had proper access to land through restitution or redistribution have not done as badly as people would make out. Detailed field research does not reveal a 90 per cent failure, which is a myth invented by the Minister himself.

There are lots of failures and problems where there was inadequate support. But actually people try to may a go of things. Research reveals that 50% of people that were given access to land are farming and that significant numbers of people feel their lives have been improved. Of the eight percent of land that has been transferred so far for people, probably half of that has meant real differences in people’s lives.

But what have been the problems then?

There are huge challenges. The redistribution program was ill conceived as a market-based program; acquisition of isolated pieces of land, farms here and there, with no real coherent program of support for them; very poor matching of need and supply, with business plans designed by consultants to put in place commercial farming systems very different from what people wanted or were able to do. And inadequate support, even for those recommended commercial systems. So, huge mismatches, between capacities, need and what was actually delivered.

Basically in practice, if not in rhetoric, there has been a bias against smallholder farming. This hasn’t been a land reform designed to support small-scale farming. It’s been for large-scale farming.

Where does the idea that ‘South Africa doesn’t have a peasantry’ come from?