Sean Jacobs's Blog, page 449

October 2, 2013

No wonder Winnie Mandela objected to this

Remember when Darrell Roodt’s “Winnie” first premiered in 2011 at Toronto Film Festival, and tanked? At the time Winnie Mandela herself declared that she didn’t like the film (unfortunately you have to watch Nadia Bilchik deliver this news)–she wasn’t consulted–and threatened to sue the producers. But Mandela needn’t have bothered. The lead actors, Terrance Howard and Jennifer Hudson’s acting was terrible; so was, as some critics noted at the time, the film’s “sentimentality” and one-dimensional portrayal of Winnie Mandela as heroine and “mother of the nation.” Here and here are some sample reviews from that premiere. So two years later, on September 6th, the film finally went on general release. It also came with a marketing push to the “urban” market. You couldn’t miss the post card sized posters of “TD Jakes Presents Winnie Mandela” at your friendly, local dry cleaners or barbershop. And a new, improved TD Jakes-remixed trailer came with the release. But none of this seemed to have helped as this round of reviews confirmed that the film is a train wreck: This is what happens when you combine bad history and bad filmmaking.

Here’s the New York Times, whose headline writer titled it “‘Winnie Mandela,’ Starring Jennifer Hudson and Many Outfits.”:

Early in Darrell J. Roodt’s rushed, patchy biopic, “Winnie Mandela,” the title character makes a grand entrance in a South African courtroom wearing a stunning outfit you might see in a glossy magazine devoted to African fashion. The judge is not amused. “Mrs. Mandela, this is a final warning,” he declares. “You will not come into this court wearing traditional regalia. It encourages dissent.” “My lord,” she replies haughtily, her eyes flashing daggers, as if she were Naomi Campbell in high dudgeon. “May I remind you that of the limited rights I have in this country, I still have the right to choose my own wardrobe.”

The Washington Post had similar insights, suggesting the film couldn’t make up its mind about Winnie:

In truth, the casting is probably the only reason “Winnie Mandela” is in theaters today. Despite the marquee names and their obvious talent, the film feels like a made-for-TV movie. It’s slight and episodic, with a weirdly scrupulous ambivalence about its subject, whom it seems torn between loving and loathing.

[The film] opens with its subject’s humble birth, accompanied by syrupy music that would not be out of place in a story about the life of Jesus Christ … the movie presents the Mandelas’ love as one of the great romances, at times depicting the struggle for black liberation as a pesky hindrance to their being together.

The LA Times found some redeeming quality: Jennifer Hudson gets to sing.

… Hudson hasn’t the acting chops to suggest complexities despite the material’s shallowness. As for Winnie’s slide from champion of justice to crime boss, complete with glass of liquor and backed by her notorious security muscle, the movie uses it for dramatic effect but hedges when it comes to holding her accountable. It does, however, give Hudson a ballad to belt out over the closing credits.

The last word goes to the AV Club, the excellent arts review section of The Onion. It is worth just indenting Scott MacDonald’s full review here:

Winnie Mandela, starring Jennifer Hudson as the wife of Nelson Mandela, could’ve been a new camp classic if the material weren’t quite so relentlessly noble. Director Darrell Roodt (Sarafina!) and screenwriter Andre Pieterse take their cues less from middlebrow Oscar fare like Gandhi and Invictus and more from glossy “a star is born” vehicles like Mahogany and Evita. Throughout, the events of Winnie’s life are just pretext for Hudson’s next big costume change, and the shifts in sartorial style are the closest the movie comes to character development. Early on, to signal that Winnie is still young and naïve, Hudson wears trim Coco Chanel—style knee-length dresses and modest cloche hats; once radicalized, she sports flamboyant kaftans and vibrantly colored dashikis; and by the Black Power ’70s, she’s got a huge afro and an array of subtly flattering camo fatigues. Poor Hudson tries to live up to both the character and the clothes, but she isn’t anywhere near assertive enough a screen presence; whenever she’s supposed to be rallying a crowd or shouting down her oppressors she looks painfully aware of her own inadequacy.

Not that Hudson has any real opportunity to give a performance, what with Roodt and Pieterse trying to cram in all of Winnie’s significant life events. They begin in a small South African village with her awesome birth, which is depicted as just slightly less awesome than the birth of the Lion King. Then, with African choir exulting, Roodt jumps ahead a few years to find Winnie beating the boys at a traditional combat game involving swords made of sticks. It’s at this point that Pieterse’s amazingly terrible dialogue begins to assert itself:

Father: “Our tradition forbids girls to use the sticks!”

Little Winnie: “Some traditions are not fair! Please, allow me to fight!”

Father: “No, you’re a girl! We must respect our traditions!”

The dialogue doesn’t improve any once the adult performers (who include Terrence Howard as Nelson Mandela) take over, and Roodt never stops rushing to the next vignette. Throughout, the average scene length is about 30 seconds; it’s as if the filmmakers feared actually having to dramatize events and settled for simply indicating them. Winnie Mandela is maybe the closest a movie has come to a series of commemorative plates.

If nothing else, the speed of events allows for some memorably hilarious moments, like the series of scenes in which Winnie is incarcerated for refusing to condemn her husband. By her seventh month in prison, she’s half mad, reciting Shakespeare sonnets—her favorite: “Shall I Compare Thee To A Summer’s Day?”—and making friends with the ants in her cell. After a while, the prison matron bursts in, screams, “Stop singing!” and crushes all the ants with her boot. Much later, after Winnie has become a power-mad liability to the anti-apartheid cause, Hudson does her best drunk-and-alone-in-a-hotel-room scene, but she has to do it in a fat suit that makes her look like one of the Klumps. It all ends with Winnie confessing her sins at a Truth And Reconciliation Commission hearing, but instead of saying anything, she simply turns around in her chair and stares at the camera with her huge, dark sunglasses. Roodt fades to black, then lets the credits roll over Hudson singing a new Diane Warren tune, “Would You Bleed For Love?” It’s enough to make Evita look classy.

Instead of going to TD Jakes for help, the producers should just have asked for Tyler Perry to speak in tongues and lay hands on them.

October 1, 2013

A Tribute to Kofi Awoonor: The Story of Sankofa

Alas! a snake has bitten me

My right arm is broken,

And the tree on which I lean is fallen.

(from Songs of Sorrow, by Kofi Awoonor)

When Kofi Awoonor started out as a writer, after his first book of poems, Rediscovery, had been published, he went to sit at the feet of traditional Ewe dirge singers to learn, to master the roots of his own story. He later translated the work of three dirge singers as Guardians of the Sacred Word and Ewe Poetry. Going back in order to move forward is what is known in the Akan tradition as Sankofa, which had one of its representative symbols popularised – upside down – on the cover of Janet Jackson’s album, The Velvet Rope. Sankofa is what I did when I went to study the science of certain traditional remedies as research for my novel Tail of the Blue Bird, but it is also – in a way – what happened when I met Professor Kofi Nyidevu Awoonor in Nairobi. I connected to the man whose novel is quoted as the epigraph for my own novel, I re-braided family ties worn loose by time and distance, I held the hand that wrote passages on Accra’s history that triggered my own interest in the subject, the focus of my current research for a non-fiction book.

Kofi Awoonor, for me, was an institution. He retained an in-depth knowledge of several indigenous Ghanaian cultures and was incredibly well-read in the Western canon. His poetry and fiction reflect this dual heritage without sentimentality. Kwame Dawes describes Awoonor’s poetry as having an “almost seamless combination of the syntax, cadence, and posture of the traditional Ewe poetic tradition, and the lyric concerns of modernist poetry. His confidence in his Ewe voice and culture made him more likely to reshape English prosody than for English prosody to alter him.”

In the master class Kofi Awoonor led at Nairobi National Museum on Friday September 20, 2013, he spoke of our connection to our ancestors, the circularity of things – how he had his grandfather’s peculiar cough, almost asthmatic but not quite. Looking at my own journey, I see echoes of the ancestral bounty he has left me. When I was battling over the decision to become a full-time writer, the man who encouraged me was Atukwei Okai, a mentee of Kofi Awoonor’s. When I fought the battle to open my novel with a ‘difficult’ section of transliterated Twi and intersperse it with Pidgin English, I did it knowing Kofi Awoonor had Ghanaianised the English language before me. When, as an editor, I encourage a diversity of poetries, a constant embracing of new influences, new syntaxes, it is no more than a re-framing of his admonition “the universe is created out of music, the tragedy with humans is that we have stopped listening.” Essentially, my confidence as a writer derives from my ancestry of peculiar folk. Of course, all this is hindsight.

I was 14 when I first read Kofi Awoonor’s novel, This Earth, My Brother; I was stumped by its double-voiced narrative, which I barely understood, but my vision of Accra, the city in which I lived, changed forever. Before the novel, I had read some of Awoonor’s poems in anthologies, but my relationship to poetry – as a reader – was not profound; Smokey Robinson, Gyedu Blay Ambolley and Curtis Mayfield had more clout then. However, This Earth, My Brother made me go to my father and ask about the other uncle he had pointed out on his vast bookshelves. But, in the year I read This Earth, My Brother, 1988, Kofi Awoonor was moving from Brazil to Cuba as ambassador so I didn’t get to meet him. Regardless, the year coincided with the transformation of my relationship with literature. Again, with hindsight, I doubt that it was fortuitous. This Earth, My Brother was one prong in a trinity of stimuli; the other two being my literature teacher in Form 4, Elinor Torto and the patron of the Achimota School Drama Club, Isaac Quist – also an English teacher. All three seeded in me a questioning approach to reading literature that has stayed with me since. In 1990 I would quit studying literature formally as I studied sciences for my A-Levels, but I would never stop reading.

The afternoon of September 19, 2013 at the Nairobi National Museum was my first physical meeting with Uncle Kofi. I had arrived late for the Storymoja Festival press conference, and approaching the amphitheatre, I recognised a couple of writers I had been dying to meet – Wally Serote and Teju Cole – and a couple I knew well – Warsan Shire and Kwame Dawes, but at the end of a crescent of chairs in the open air space was a face which bore an uncanny resemblance to my late father’s. I knew Uncle Kofi from photographs; his face was typical of men derived from the West African Williams’: elongated enough to be North African, dark enough to be East African, serene in repose, yet animated with probing, twinkling eyes. Here, in the flesh, was the man who had composed reams of effortlessly accomplished poems, evaded government spies, represented Ghana as envoy to Brazil, Cuba and the UN, taught literature and written one of my favourite novels, This Earth, My Brother. I stole glances at him as the authors and festival directors answered questions from the media.

At the end of the Storymoja Festival press conference, he hugged me, then held me back to introduce his son: ‘Afetsi, this is your cousin,’ he said, then he asked, ‘Are you Frank’s son or Jerry’s son?’ I answered, ‘Jerry,’ and he burst out in a belly laugh I can still feel the rumbles of. ‘Your father used to crack me up. I have stories to tell you.’ He insisted that I come and see him in Ghana and asked Afetsi to take my number and give me his. That was the first of three occasions I was in his presence. I was not to know that the universe was pitching with me – three strikes and I am back to the locker room, three times bereft.

I have come to learn that there are two kinds of mentors; those who by the strength of their presence inspire you, through conscious imitation, adaptation and evolution; and those whose influence, by virtue of their physical absence, you are unaware of – almost akin to the manner in which the absence of love can inspire great writing about love. The latter kind of mentor can not be a dictator. Absent mentors are powerful because what we choose of their legacy is not influenced by their physical prodding, we are drawn to the elements of their legacy that resonate and that, ultimately, serve both mentor and mentee best. My teachers, Elinor Torto and Isaac Quist, were the former kind; Uncle Kofi has the distinction, by virtue of three meetings with him after a lifetime of ‘absent guidance’, of being both. I was blessed to have met him; losing him was my curse. This is the other side of Sankofa – you come upon something in the forest: if you pick it up, you gather a curse; if you leave it behind, you forfeit a blessing. For this reason, I am carrying the kind of smile Smokey Robinson wrote so eloquently about in The Tracks Of My Tears. Don’t come too close.

A giant lies, far from the tree

that once shed incense

on infant corn. The ear rings,

the slap of his voice still

fresh in the morn of his fall

Mulatu Astatke is a legend

Mulatu Astatke has achieved what most musicians could only dream of: he invented an iconic genre. In the 1970s, Astatke pioneered a fusion of western jazz with the traditional sounds and instruments of Ethiopia to create Ethio-jazz. One could say he is the “O.G.” of Ethio-jazz (to use hip-hop parlance). Now 70 years old, Astatke refuses to slow down, or rely on his rich past and diverse repertoire. His new album Sketches of Ethiopia was released recently under the international label Jazz Village, and shows us why the king of Ethio-jazz is still at his imperial throne.

The first time I heard Mulatu Astatke’s Music was in a dark art house cinema somewhere in Cape Town in 2005. The film being screened was Jim Jarmusch’s quirky comedy-drama Broken Flowers, a film about an aging Don Juan character, Don Johnston (played by Bill Murray) who receives a mysterious letter stating that he has a son. Don’s Ethiopian neighbor Winston (Jeffrey Wright), a mystery novel enthusiast, gives Don a fitting mixtape on his road trip to find his long lost offspring: the hypnotic sounds of Ethiopian jazz, “good for the heart.” One song in particular, Astatke’s ‘Yekermo Sew’, with its winding, mystical horn refrain, and funky steady rhythm, becomes the soundtrack of one man’s journey into the past and into himself. It was like listening to hip-hop for the first time, something so new to the ear and yet so familiar. Astatke’s music stood out as one of the highlights of Jarmusch’s film and propelled him into international cult status.

By then Astatke had already gained international acclaim. In the late 1990s his music was rereleased with the Parisian label Buda Musique’s Ethiopiques series, rereleases of “golden age” Ethiopian jazz and popular music originally recorded by Amha Records, Kaifa Records and Philips Ethiopia. This was to become a staple for hippies, hipsters and jazz lovers the world over. With the spread of his cult status in the west, Astatke has since collaborated with the Either/Orchestra and the Heliocentrics, and has received a number of accolades and awards from various institutions. Younger audiences have taken to him too, and his music can be found as samples on tracks from hip-hop artists like K’naan and Nas.

In Sketches of Ethiopia, his first album since the sublime Mulatu Steps Ahead (2010), Astatke leads a 12-piece team of London based jazz musicians through his signature Ethio-jazz blend of sounds, spaces and moods. The Ethiopian traditional instruments masinko, krar, and washint jam and blend perfectly with the traditional western jazz instruments; piano, bass, sax, etc. The first track, ‘Azmari’, kicks off with frenetic tense energy, like a cinematic chase scene in a busy Addis marketplace. Tight multi- instrumental jazz melodies build up and break beautifully. The second track, ‘Gamo’, is just as rich in soundscape but more upbeat and funky, and features emerging Ethiopian talent Tesfaye. The standout vocal performance however belongs to Malian singer Fatoumata Diawara. Her voice beautifully rides the Afro-funk/dub rhythms of the last track ‘Surma’. As with this inclusion of the West African kora on the album, Fatoumata gives Sketches a fresh East/West collaboration and a pan-African edge.

Astatke is a master of the vibraphone, which he studied at Berklee Music College in Boston back in the 60s when he was its first African student (he now holds an honorary doctorate from the institution). In ‘Assossa Darache’, a gentle yet progressive jazz piece, he leads with his contemplative vibraphone, laying a bed for which complex jazz time changes and shifts later occur over its ten minute trajectory, with some fine solo piano work by Alexander Hawkins. However it’s Astatke’s vibraphone solo that is the real gem. It never steals the show — it is too respectful of the other instruments for that — yet it shines with its own quiet glow, adding an extra dimension and depth to an already exceptional jazz piece.

One of the things that always drew me to Astatke’s work was that it is both accessible and complex; familiar yet strange at the same time. There is a spiritual quality to Astatke’s Ethio-jazz that I can’t quite pin down. Perhaps it’s in the mystical middle-eastern sounding Ethiopian pentatonic scale, or the sadness of Tezeta (nostalgia) folk/blues songs from a region that is no stranger to suffering. It could be the Coptic church melodies, or maybe it’s in the searching and wandering nature of Astatke himself. What’s clear is that Sketches of Ethiopia is a bold album and a valuable contribution to the Ethio-jazz genre by a veteran who continues to push himself to further depths, a virtue which young musicians would do well to follow.

Photo by René Habermacher.

Mulatu Astatke’s Sketches of Ethiopia

Mulatu Astatke has achieved what most musicians could only dream of: he invented an iconic genre. In the 1970s, Astatke pioneered a fusion of western jazz with the traditional sounds and instruments of Ethiopia to create Ethio-jazz. One could say he is the “O.G.” of Ethio-jazz (to use hip-hop parlance). Now 70 years old, Astatke refuses to slow down, or rely on his rich past and diverse repertoire. His new album Sketches of Ethiopia was released recently under the international label Jazz Village, and shows us why the king of Ethio-jazz is still at his imperial throne.

The first time I heard Mulatu Astatke’s Music was in a dark art house cinema somewhere in Cape Town in 2005. The film being screened was Jim Jarmusch’s quirky comedy-drama Broken Flowers, a film about an aging Don Juan character, Don Johnston (played by Bill Murray) who receives a mysterious letter stating that he has a son. Don’s Ethiopian neighbor Winston (Jeffrey Wright), a mystery novel enthusiast, gives Don a fitting mixtape on his road trip to find his long lost offspring: the hypnotic sounds of Ethiopian jazz, “good for the heart.” One song in particular, Astatke’s ‘Yekermo Sew’, with its winding, mystical horn refrain, and funky steady rhythm, becomes the soundtrack of one man’s journey into the past and into himself. It was like listening to hip-hop for the first time, something so new to the ear and yet so familiar. Astatke’s music stood out as one of the highlights of Jarmusch’s film and propelled him into international cult status.

By then Astatke had already gained international acclaim. In the late 1990s his music was rereleased with the Parisian label Buda Musique’s Ethiopiques series, rereleases of “golden age” Ethiopian jazz and popular music originally recorded by Amha Records, Kaifa Records and Philips Ethiopia. This was to become a staple for hippies, hipsters and jazz lovers the world over. With the spread of his cult status in the west, Astatke has since collaborated with the Either/Orchestra and the Heliocentrics, and has received a number of accolades and awards from various institutions. Younger audiences have taken to him too, and his music can be found as samples on tracks from hip-hop artists like K’naan and Nas.

In Sketches of Ethiopia, his first album since the sublime Mulatu Steps Ahead (2010), Astatke leads a 12-piece team of London based jazz musicians through his signature Ethio-jazz blend of sounds, spaces and moods. The Ethiopian traditional instruments masinko, krar, and washint jam and blend perfectly with the traditional western jazz instruments; piano, bass, sax, etc. The first track, ‘Azmari’, kicks off with frenetic tense energy, like a cinematic chase scene in a busy Addis marketplace. Tight multi- instrumental jazz melodies build up and break beautifully. The second track, ‘Gamo’, is just as rich in soundscape but more upbeat and funky, and features emerging Ethiopian talent Tesfaye. The standout vocal performance however belongs to Malian singer Fatoumata Diawara. Her voice beautifully rides the Afro-funk/dub rhythms of the last track ‘Surma’. As with this inclusion of the West African kora on the album, Fatoumata gives Sketches a fresh East/West collaboration and a pan-African edge.

Astatke is a master of the vibraphone, which he studied at Berklee Music College in Boston back in the 60s when he was its first African student (he now holds an honorary doctorate from the institution). In ‘Assossa Darache’, a gentle yet progressive jazz piece, he leads with his contemplative vibraphone, laying a bed for which complex jazz time changes and shifts later occur over its ten minute trajectory, with some fine solo piano work by Alexander Hawkins. However it’s Astatke’s vibraphone solo that is the real gem. It never steals the show — it is too respectful of the other instruments for that — yet it shines with its own quiet glow, adding an extra dimension and depth to an already exceptional jazz piece.

One of the things that always drew me to Astatke’s work was that it is both accessible and complex; familiar yet strange at the same time. There is a spiritual quality to Astatke’s Ethio-jazz that I can’t quite pin down. Perhaps it’s in the mystical middle-eastern sounding Ethiopian pentatonic scale, or the sadness of Tezeta (nostalgia) folk/blues songs from a region that is no stranger to suffering. It could be the Coptic church melodies, or maybe it’s in the searching and wandering nature of Astatke himself. What’s clear is that Sketches of Ethiopia is a bold album and a valuable contribution to the Ethio-jazz genre by a veteran who continues to push himself to further depths, a virtue which young musicians would do well to follow.

Photo by René Habermacher.

September 30, 2013

The U.S. premiere of Alain Gomis’ new film “Tey (Aujourd’hui)”

Alain Gomis’ latest film, Tey (Aujourd’hui) is a gentle and understated exploration of life, death, memory, and the passing of time. The film tells of Satché’s (played by Saul Williams) last day on earth, for it has been decided that his time has come to die. Satché himself has recently returned home to Dakar, Senegal after spending the past several years living in the United States. Very much reminiscent of the films of Djibril Diop Mambety, Tey (trailer below) follows Satché as he wanders through the city visiting friends, family, and his former lover. It is a staggering work of quiet reflection that ends up being as much an homage to the city of Dakar as it is a study of a man coming to terms with his own mortality. Jonathan Duncan reviewed the film here.

Alain Gomis’ Dakar is one of contrasts, with construction sites and unfinished buildings juxtaposed against towering, modern glass skyscrapers; middle class households and former colonial neighborhoods appearing alongside informal settlements of cinder blocks and corrugated metal. When I asked Alain Gomis about the contrasts in his portrayal of the city, he responded by explaining:

If you’re trying to find the right image of [Dakar], you can have a thousand images and still not have the perfect picture of [Dakar]. The real [Dakar] exists in the gaps between all those pictures. Truth is found in all those things that escape us. Truth is in the in-betweens.

I think it fair to apply this idea to all of Tey (Aujourd’hui): the film is about liminality; the feeling of being in-between – in between life and death, present and future, being at home and being a stranger, an agent and observer, object and subject. The film’s brilliance lies in what is not said – it’s silences on things that do not need to be spoken. In effect, this pushes the viewer to internalize the film on a much deeper emotional level and forces him or her to engage with the content in a way that has become all too rare in the realm of cinema.

Alain Gomis was born in Paris in 1972 to a French mother and Senegalese father. He directed several short films before shooting his debut feature L’Afrance in 2001, which won awards including the Ecumenical Jury Prize and the Silver Leopard in Locarno. The film focused on the character El Hadj Diop, a Senegalese student whose residency in Paris is nearing its expiration. Tey is Gomis’ third feature, and premiered to great acclaim at the Berlin Film Festival 2012. The film just recently won the prestigious Golden Stallion at the FESPACO 2013 for best film and best actor, a first for Senegal and a first for an American actor.

The film will be available in selected theaters around the U.S. from October 6th – November 6th, 2013. The U.S. premiere and a week-long theatrical run will take place at New York’s MIST Harlem Cinema on Sunday, October 6th in partnership with the Creatively Speaking Film Series.

U.S. premiere of Alain Gomis’ new film “Tey (Aujourd’hui)”

Alain Gomis’ latest film, Tey (Aujourd’hui) is a gentle and understated exploration of life, death, memory, and the passing of time. The film tells of Satché’s (played by Saul Williams) last day on earth, for it has been decided that his time has come to die. Satché himself has recently returned home to Dakar, Senegal after spending the past several years living in the United States. Very much reminiscent of the films of Djibril Diop Mambety, Tey (trailer below) follows Satché as he wanders through the city visiting friends, family, and his former lover. It is a staggering work of quiet reflection that ends up being as much an homage to the city of Dakar as it is a study of a man coming to terms with his own mortality. Jonathan Duncan reviewed the film here.

Alain Gomis’ Dakar is one of contrasts, with construction sites and unfinished buildings juxtaposed against towering, modern glass skyscrapers; middle class households and former colonial neighborhoods appearing alongside informal settlements of cinder blocks and corrugated metal. When I asked Alain Gomis about the contrasts in his portrayal of the city, he responded by explaining:

If you’re trying to find the right image of [Dakar], you can have a thousand images and still not have the perfect picture of [Dakar]. The real [Dakar] exists in the gaps between all those pictures. Truth is found in all those things that escape us. Truth is in the in-betweens.

I think it fair to apply this idea to all of Tey (Aujourd’hui): the film is about liminality; the feeling of being in-between – in between life and death, present and future, being at home and being a stranger, an agent and observer, object and subject. The film’s brilliance lies in what is not said – it’s silences on things that do not need to be spoken. In effect, this pushes the viewer to internalize the film on a much deeper emotional level and forces him or her to engage with the content in a way that has become all too rare in the realm of cinema.

Alain Gomis was born in Paris in 1972 to a French mother and Senegalese father. He directed several short films before shooting his debut feature L’Afrance in 2001, which won awards including the Ecumenical Jury Prize and the Silver Leopard in Locarno. The film focused on the character El Hadj Diop, a Senegalese student whose residency in Paris is nearing its expiration. Tey is Gomis’ third feature, and premiered to great acclaim at the Berlin Film Festival 2012. The film just recently won the prestigious Golden Stallion at the FESPACO 2013 for best film and best actor, a first for Senegal and a first for an American actor.

The film will be available in selected theaters around the U.S. from October 6th – November 6th, 2013. The U.S. premiere and a week-long theatrical run will take place at New York’s MIST Harlem Cinema on Sunday, October 6th in partnership with the Creatively Speaking Film Series.

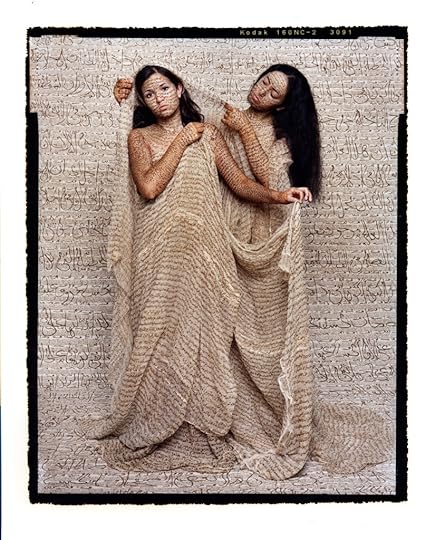

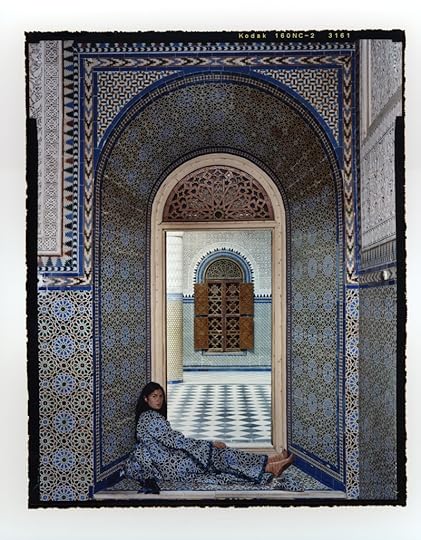

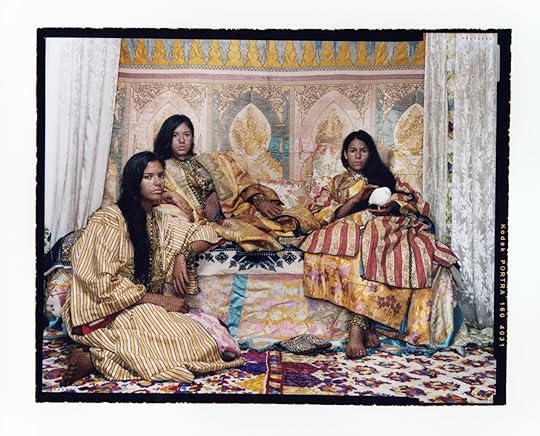

An interview with artist Lalla Essaydi on looking beyond beauty

In early September, I sat down to lunch with artist Lalla Essaydi not far from her Midtown West studio in Manhattan. Ms. Essaydi comes across as a self-assured woman. In appearance and manner, she is refined and elegant, but the self-assuredness manifests most poignantly in the thoughtful and strikingly articulate way she describes her life, her art, and their intersection. A friend introduced me to her work earlier this year. I was immediately moved by the sheer beauty of her photographs; then quickly entranced by the thought-provoking detail and delicate nuance embodied within each one. Essaydi’s work is at its core autobiographical, however it seeks to challenge Orientalist mythology, often doing so by “appropriating Orientalist imagery from the Western painting tradition.”

The story behind her introduction to Orientalist art and the journey that led to her present work is an interesting one that begins, perhaps surprisingly, with an appreciation of the genre. “I fell in love with the aesthetic beauty of Orientalist paintings while in Paris many years ago,” Essaydi explained, “Then I started reading about Orientalism. I love the way [the pieces] are painted, they are exquisite, but then I started seeing how they portray the culture.” At this time in her life, she felt these paintings were simply a portrayal of fantasy, as she, a part of one of the cultures being portrayed, knew the images were not representative. “It was the portrayal of a fantasy, and I thought everybody knew that.”

It was an interaction that took place while working toward her MFA at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston that helped bring to light the fallacy of this belief, and set the trajectory of her career. She had created large pieces playing off the work of renowned 19th century French painter Jean-Léon Gérôme, well known for his Orientalist depictions. A curator approached her, curious about the work.

“She wanted to know why I had incorporated Gérôme, why I was making it so huge, presenting it in this way, and so on. I started talking to her about it, telling her that [Gérôme’s portrayal] was a fantasy, and explaining that I was trying to show that by putting the image in a different setting, [I was hoping] to make people realize that if you remove the characteristics of these paintings that make them so beautiful – that [it is the] beauty that allows you to actually look at these women being sold in the streets, accept that, and still look at it as a very beautiful thing.”

[Click on the images below to enlarge them.]

As the discussion with the curator progressed, Ms. Essaydi expressed her belief that it was wrong to willfully misrepresent a culture in this way, and depict fantasy as reality. The curator replied: “I had no idea it was a fantasy, I thought it was real.” Not surprisingly, this interaction had a lasting impact on her. “I will never forget that encounter, because it drew a line for me. [I knew] almost instantly that this was my path, so in a way, I thank her.”

This however was just the beginning. “I started my investigation that way but at the same time, I wanted to understand what made [these artists] want to do something like that.” Naturally, this led to more questions; “[I asked myself], what is so different about us as women in our culture? I needed to know more about myself to understand them, and to understand why they created this fantasy world that doesn’t exist, that other people believe exists. Until now, I am still struggling, trying to find an answer, because I don’t think that image is gone.” Ms. Essaydi says she used to find the impact of these false depictions very frustrating. However she soon realized it was partially up to her to make a difference. She realized if she allowed this frustration to consume her, it would be counter-productive. “That’s how things started changing for me,” she said, “I became very patient.”

Her patience is also apparent in the detail and complexity of her work. The preparation behind any single photograph can only be described as a labor of love. Showing me proofs of work she had completed over the summer, an as of yet unreleased extension of her collection “Bullet”, she described the preparation behind an immense cape constructed entirely of bullet casings. That single piece alone took her a year to construct, assembling it in New York, and transporting it with her, piece-by-piece to Morocco. The calligraphy, a consistent theme throughout her work, is also a substantial undertaking, meticulously hand-written on her models, walls, and massive swaths of textile. It is thus understandable that she does not think of her work exclusively as photography. “I don’t work only with one medium, I like to paint, to write, to photograph… and each medium really informs the next. In my mind I always think of myself as a painter, because that’s my formation… and I don’t really think of my photographs as just being photographs… there is so much that goes into it, it is based on many, many things.”

The multi-faceted nature of her work is part of what makes it so compelling. Each component has significance. Her photographs have three thematic foci: the veil, the odalisque, and the harem. She explains that the veils used in her work are metaphors of cultural realities and evolution, but most of all a critique of misrepresentation. “I am talking about when these painters were painting nude women and pretending they were Arabs, how at that time in my culture, and now, it is at a young age [that women] start to cover. How could these men pretend to be going into their homes and painting them nude?” The harem too is symbolic. The way it existed in the mind of the Western artist was artificial. Essaydi explained that in reality the Moroccan harem was a place for the family, a household where women and children would spend time. “It is a family home, where the father and brothers would be, where uncles would come visit, but not men that we don’t know…they took it and turned it into something else completely.”

Space is an important component of Essaydi’s work, whether she is creating a set, or working within existing structures, great thought is put into location. In her earlier work, informed by the initial stages of her self-exploration, she returned to her childhood home. This is where she shot “Converging Territories”, taking a space that had been only for men, and making it a space only for women, covering the walls in script. For her collection “Harem”, she expressed her need for the space to be authentic, and spoke of the time it took for her to find the perfect place. But it is more than the space itself; it is the role of women within these spaces. “This is why in my work… all the women wear the same pattern as the wall, she becomes the harem space, but she is also the harem.”

Beyond the symbolism in her work, Essaydi’s aesthetic is undeniably visually pleasing. She explained that while her work is received very differently in the West and Arab World, the one aspect that is universally appreciated is the aesthetic. This she finds troubling. “I want people to look past that, because remember what we’re talking about, the beauty in those [Orientalist] paintings… Part of what makes those paintings so powerful is the beauty.” But she insists on staying true to her natural aesthetic. “You can’t run away from that,” she says, “It is you. At the same time beauty is what attracts you to the art in the first place… I want to have a dialogue. If I put it in their faces, they’re going to turn away… it’s very dangerous, I know that, and I hate it when people only like the work because it is decorative.”

As mentioned above, much of Essaydi’s work has been about self-exploration, and autobiographical in nature, but she has chosen to keep it abstract. “There are so many layers to my work, and some of them are just for me. If the viewer does not discover it on their own, I’m not going to talk about it because I have always been told how to behave, what to say, how to see things, how to think, and I don’t want to impose that on the viewers by stating everything. I do what I do for myself, before anything else.”

As our meal winds down she becomes somewhat reflective: “You look at your work, you try to do something and you produce something that people may be very enthusiastic about, but inside me, I know that I haven’t reached what I wanted.” Laughing she adds, “I hope I will not reach it, because the day I reach it, I think I will be done.”

Lalla Essaydi is represented by the Edwynn Houk Gallery in New York and Zurich, the Miller Yezerski Gallery in Boston, and Gallery Tindouf in Marrakech. Her work is currently part of “She Who Tells a Story”, an exhibition showcasing the art of female photographers from the Middle East, showing at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston through January 12. For more information on upcoming exhibitions through 2015, visit lallaessaydi.com

Why do the middle classes in South Africa pay their domestic workers such low wages?

A few months after the Hewitts, a white South African family in the capital Pretoria, moved to a black township to live there for a month and blogged about it, we are left to wonder — media hype aside — has anybody economically benefited from this spectacle of empathy? Has it, for example, made any difference for those township residents who commute to middle class suburbs and city centers every day to work in the homes of people like the Hewitt’s? I doubt it.

While some of South Africa’s contemporary (but apartheid-bred) social ills can be ascribed to a lack of political will and resources, the widespread underpayment of domestic workers is not one of them. (In fact, South Africa was one of the first to ratify the Domestic Workers Convention, which went into force earlier this month.)

Instead, it’s an issue of public will and a collective refusal to pay a decent wage that renders the lives of so many hardworking girls and women (many of whom are mothers and care takers) into such an economical challenge. Amongst the wealthy, the middle class, the international students as well as many international professionals and development workers, of whom many (though not everyone) can easily afford to pay more, the refusal to pay their cleaning ladies a decent wage is unrelenting.

Why? Perhaps South Africa’s horrible mathematics scores have something to do with it. Because surely anyone who nails the grade 3 basics of pluses and minus can calculate that R150 (about US$15 or €11) per day minus R20 transportation equals R130 (US$13 or €9,5) about a day for a liberally assumed average of, say, 20 workdays a month does not equal a decent wage. Pretty straightforward math.

Of course, SA is more than its Gini coefficient; not everyone is in the position to be generous. So in the face of an estimated unemployment rate of 25,5%, R150 is better than nothing. But for many who are, the ability to pay more seems utterly irrelevant. Standard rationales: “A cleaning lady only costs 150 rand!”; “Does the lease includes a domestic?”; or “Our maid is looking for more hours and I’m trying to help her find them.”

Why deviate from the convenience of the norm if it’s normalized by everyone around you and if the minimum wage law tells you it’s acceptable? For those outside South Africa, this norm consists of R150 for a full day of work, which usually includes travel expenses and an occasional gift or bonus, depending on the mood du jour.

That’s South Africa right there; where you can be on the board of I don’t know how many township development projects, cheer the symbolism of bridge building, theoretically back the concept of affirmative action and lament the ANC’s lack of political will to take care of its poorest citizens, while finding it totally appropriate to leave 150 rand and a tin of Ricoffi on the kitchen table in exchange for the care and labor that your most personal belongings require.

* The image is from photographer Zanele Muholi’s 2008 project “Massa and Mina(h)”.

Roland Barthes, his Grandfather and Côte d’Ivoire

“He had nothing to say.” That’s how French philosopher Roland Barthes described his grandfather Louis-Gustave Binger, the archetypal French colonialist: “Il ne tenait aucun discours”. And yet. Explorer of the Niger Loop, Louis-Gustave Binger was the author of Du Niger au Golfe de Guinée (1891). He was the founder of the Côte d’Ivoire colony and was appointed its governor in 1893. He was “officially” considered the “father” of the nation. He founded and set up the first capital, gave his name to the second. He features on the country’s stamps:

Binger also wrote Le Serment de l’Explorateur, a novel in which an explorer heads off “to Africa” leaving his wife and daughter behind. The photographs taken during Binger’s explorations are the first photographs ever taken in Côte d’Ivoire.

But, “It is as if neither honours nor books ever existed for Roland Barthes.”

A few years ago, Vincent Meessen has made a short film, “Vita Nova,” about Roland Barthes’ peculiar silence about his grandfather’s colonial life, which you can now watch online:

Read an interview with Vincent Meessen about “Vita Nova” here. Meessen is currently working on a new film, La Poule d’Ombredane, which takes its cue from the Congo-based experiments by French psychologist André Ombredane (1898–1958).

September 28, 2013

What are the “unintended consequences of Dutch colonialism”?

In their documentary installation piece “Empire: The unintended consequences of colonialism,” filmmaker team Eline Jongsma and Kel O’Neill seek out the residue of centuries of Dutch imperialist projects, highlighting what they have referred to as the “humanity” in colonization. The project took Jongsma and O’Neill four years to complete, and sent them to ten countries worldwide. The result, which has its US premiere at the New York Film Festival this weekend, is an interactive audiovisual experience. Audience members will move through the stories–just as the Dutch moved through their empire, perhaps–piecing together fragments and identifying threads as they go along.

While I am yet to experience the project in full, I’ve seen at least three of the twelve films (“India,” “South Africa,” “Indonesia”) that will feature in the Lincoln Center installation. In these pieces, I was treated to the juxtaposition of a Tamil granite factory exporting tombstones to the Netherlands, with a project to preserve the graves of Dutch traders in Gujarat. This was followed by perspectives on race and purity in Orania (video still above), contrasted with ideas about hybridity and origins held by Cape Malay choir members. Finally, I watched Nazi war reenactors in West Java, alongside a revived Jewish community in Northern Sulawesi.

I watched these films once, and again in a different order. I viewed them a third time, in another setting. Each time I came away with a gnawing sense of ambivalence, and many questions. Sure, these are intriguing snapshots of “obscure and weird” situations in post-colonial contexts. But are these stories really connected? And are they simply consequences of colonialism? And, for that matter, what exactly is an “unintended consequence” of colonialism?

As I understand, part of the point of the project is to give audience members fragments, with which they can then connect the dots, ask questions and find an underlying thread. Being a diligent audience member, I tried–I really did. As I watched and reflected, it became increasingly apparent to me that the underlying glue binding these stories was a subtle colonial nostalgia. The characters in the films engaged in it to varying degrees, and the project seems to be based on it.

This colonial nostalgia has serious implications for how Empire’s post-colonial story is told, and the way hybridity and cosmopolitanism are envisioned in the project. With regards to the former, as O’Neill explained in a recent interview, Empire is “about this post-colonial space that’s scattered all over the world.”

More precisely, and rendered visually in the installation (see map here) it is a post-colonial space where the Netherlands is “The Cradle,” and the colonies and former trading centers are sites of “Legacy,” “Migrants” and the “Periphery.” (According to the installation map, the coverage of the Netherlands features two films shot at Schiphol Airport.) In this centre/periphery framework, culture emanates from Europe and out to the rest of the world. It is not a matter of mutual-influence, but uni-directionality.

Having not seen the entire installation, perhaps I’m jumping the gun here. However, there seems to be a gaping hole where reflexivity should be. In the search for traces of colonial influence far and wide, did Jongsma and O’Neill think about the ways in which Suriname, Indonesia or Sri Lanka left their imprint on the Netherlands? Can the post-colonial space be one of multiple cradles?

Speaking about the kind of culture the pair encountered in making Empire, Jongsma recently stated:

We realized there is this sort of global post-colonial culture of people who wouldn’t exist without the help of European—in this case Dutch—traders and colonists, and their decisions that they made in the past.

Again, the sway of Dutch authority in creating this weird and wonderful post-colonial space and way of being is paramount. Of course, to deny the role of colonization in the formation of the particular hybrid identities and cultural remnants portrayed in Empire would be misguided. However, we should be careful not to assume that similarly complex stories of movement, difference and cultural sharing did not exist prior to the presence of 17th century European imperialism. Nor should we think that cosmopolitanism is a gift of European exploration and colonization. As Trans-Saharan, Indian Ocean and other fields of connected history have shown, cultural hybridity, mobility and dislocation have characterized the lives of communities and individuals in diverse regions for hundreds of years. The colonial factor adds but another layer to existing entanglements, bringing with it further complications and its own quirks.

While preliminarily weary of the underlying notions of post-coloniality and hybridity in the overall project, I was also taken by Jongsma and O’Neill’s storytelling approach. From the three films I watched, it is clear that Jongsma and O’Neill have found some anecdotal gems, recovering both intimate stories of identity, change and struggle, and those of everyday life, entertainment and personal quirks. Each fragment is multilayered and could easily compel an audience to dig deeper, to look further into the histories surrounding these case studies. After all, why are Indonesian men in their mid-20s running around forests in military gear, shouting at each other in German? And do some Afrikaners really see the Dutch as South African?

Are these stories connected, beyond the mere fact that the Dutch happened to be in those particular regions several centuries ago? I remain to be convinced. Nevertheless, Empire takes an ambitious step in moving towards the telling of personal stories of difference and hybridity, and placing them in a global context.

Sean Jacobs's Blog

- Sean Jacobs's profile

- 4 followers